Introduction

The alliance system led by the United States (US) in the Asia–Pacific, comprising bilateral alliances, has been a pillar of American regional leadership since the end of the Second World War.Footnote 1 Alongside this ‘hub and spokes’ system,Footnote 2 the United States has promoted various mini-lateral security frameworks to enhance regional stability and share security burdens.Footnote 3 One key initiative has been Washington’s effort, since the late 1990s, to strengthen Japan–South Korea security cooperation within a trilateral framework.Footnote 4

The rise of China and its challenge to US leadership in the Asia–Pacific prompted the Obama administration’s Pivot to Asia, initiating a new phase in efforts to enhance Japan–South Korea relations and expand trilateral cooperation in the 2010s. Despite a period of stagnation from 2018 to 2020 due to domestic political shifts and tensions between Tokyo and Seoul, leadership changes in South Korea and the United States, alongside evolving geopolitical dynamics, have revitalised trilateral engagement. Notably, the 2022 Phnom Penh Statement broadened the scope of cooperation to include the Indo-Pacific,Footnote 5 and the 2023 Camp David Summit sought to institutionalise annual high-level meetings and military exercises.Footnote 6 While these developments signal strengthened political intent, the Camp David Summit, in particular, represents a symbolic milestone in the evolution of US-led trilateral security coordination.Footnote 7

Initially, this partnership focused primarily on North Korea’s nuclear threat, but several observers note that it has increasingly framed China as an indirect target.Footnote 8 The Camp David Declaration further reinforced this perception by explicitly opposing certain aspects of China’s regional behaviour.Footnote 9 Despite persistent policy divergences among the three states,Footnote 10 and the potential for strategic ambiguity or ad hoc responses from China, Beijing has closely monitored the evolution of trilateral security cooperation and other US-led regional initiatives, perceiving them as part of a broader effort to contain China through exclusive security frameworks.Footnote 11 One of the most prominent expressions of Chinese opposition came in response to the US–South Korea deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) system. China reacted with sustained economic and diplomatic coercion, signalling its broader apprehension towards institutionalised trilateralism in the region. Yet, despite its explicit concerns regarding the trilateral partnership and the fragile nature of Japan–South Korea relations,Footnote 12 China has not actively sought to exploit tensions between Tokyo and Seoul to weaken their cohesion or obstruct trilateral military alignment. Instead, it has adopted a relatively restrained posture towards Japan–South Korea relations.

This restraint gives rise to an important analytical puzzle: What explains China’s strategic behaviour in response to Japan–South Korea rapprochement within the US-led trilateral framework? Given the strategic importance of wedging in China’s efforts to undermine (potential) countervailing alliances,Footnote 13 as seen in its response to the THAAD deployment, a logical expectation is that China would adopt a similar approach in this context.Footnote 14 However, available evidence suggests that while China intends to drive a wedge, neither selective accommodation, coercive wedging, nor a wait-and-see approach fully explains its response.Footnote 15

To explain China’s behaviour and address the conceptual gap in existing wedging theory, this paper introduces soft wedging as an alternative to selective accommodation and coercive wedging. Unlike conventional wedging tactics, which involve direct interventions – through inducements or coercion either to create or amplify divisions – soft wedging seeks to perpetuate existing disputes indirectly through rhetorical cues and signalling, without overt engagement. In the context of Japan–South Korea relations, China has refrained from overtly exploiting the rifts but has strategically reminded South Korea of historical grievances and the need for caution in its rapprochement with Japan. This approach aims to subtly discourage deeper alignment with Tokyo and trilateral security integration with Washington. China’s preference for soft wedging towards Japan and South Korea is influenced by the nature of the disputes between the two states and China’s wedging goals in Northeast Asia. While its behaviour may occasionally appear ad hoc, rather than part of a single, masterfully coordinated plan, we observe a relatively consistent pattern in China’s response in this case, which reflects a set of objectives – namely, to prevent the strengthening of the US–Japan–South Korea trilateral security partnership, while minimising resource expenditure and reducing the risk of further alienating either Japan or South Korea. Soft wedging, we contend, offers an effective and relatively low-cost strategy to achieve these aims.

Many scholars have examined China’s wedge strategies in the Asia–Pacific region,Footnote 16 but limited research has focused on its approach to the US–Japan–South Korea trilateral security partnership or Japan–South Korea cooperation in Northeast Asia. While some studies have analysed Japan–South Korea ties in the 2010s, few have explored whether China has exploited their divisions, as many tend to interpret China’s strategy towards these two states primarily through the lens of China–US relations rather than from the perspective of wedging strategies.Footnote 17 As such, this paper not only provides an explanation of China’s strategic approach to Japan–South Korea rapprochement and rifts within the context of the US’s motivation for a trilateral security partnership but also expands the wedging framework and enhances its theoretical utility by introducing soft wedging. Additionally, the aspect of a divider addressing multiple targets simultaneously is underexplored in the wedge strategy literature. In China’s case, if it employs a wedging approach, it acts as the divider, the US serves as the competitor, and both Japan and South Korea function as targets. This study also contributes to the theoretical discourse by analysing how wedging can be applied against multiple targets, rather than focusing solely on a single-target dynamic.

This paper is structured in four parts. The first section reviews the existing literature on wedge strategies. Building on this foundation, the second section introduces soft wedging as a conceptual extension of traditional wedging strategies. The third section examines China’s strategic response to the Japan–South Korea entente under the US’s trilateral partnership ambitions since 2010. It analyses how China employed rhetoric in public statements and diplomatic engagement as a form of soft wedging, examines alternative explanations, and explores the strategic calculus behind China’s preference. The final section summarises the key findings, discusses the implications of this study, and suggests directions for future research.

Existing literature on wedge strategy

The wedge strategy is a longstanding and widely observed tactic in international politics. Chinese strategist Sun Tzu recognised its importance for states,Footnote 18 yet despite its historical effectiveness, it has received relatively little attention in international relations theory compared to areas such as alliance formation and management. However, it was not until the emergence of Crawford’s theoretical framework that the wedge strategy began to receive the scholarly attention it merits.

Crawford defines wedging as a state’s endeavour ‘to prevent, break up, or weaken a threatening, or blocking alliance at an acceptable cost’.Footnote 19 He identifies four primary objectives: realignment, dealignment, disalignment, and prealignment. The first three apply to an established adversary alliance, in which a divider attempts to realign the target towards a new alliance, push it towards neutrality, or weaken alliance cohesion without causing outright collapse. Prealignment aims to prevent the formation of a countervailing alliance. To achieve these objectives, states typically employ either selective accommodation or a confrontational wedge strategy. Selective accommodation relies on concessions and incentives to lure a target away from its competitor, often by exacerbating existing tensions or creating new conflicts among (potential) allies. In contrast, confrontational wedging leverages firmness and intimidation to expose and amplify discrepancies in the adversaries’ strategic interests. Crawford argues that selective accommodation is generally more effective than confrontation, as excessive pressure may reinforce a target’s threat perception, thereby pushing it closer to a competitor. He further classifies selective accommodation into three forms based on cost: appeasement (most costly), compensation, and endorsement (least costly). These forms vary in the nature of the concessions offered, as a divider concedes primary interests in appeasement, secondary interests in compensation, and tertiary interests in endorsement.

Building on Crawford’s model, Izumikawa introduces the concept of ‘reward power’, which he defines as the ‘capability to reward’.Footnote 20 He conceptualises ‘selective accommodation’ as ‘reward wedging’, emphasising that its effectiveness depends on whether the divider possesses sufficient inducement capacity. Conversely, he labels the ‘confrontational wedge’ as ‘coercive wedging’ and suggests that while a divider may still opt for reward wedging despite limited reward power, it may be forced to resort to coercive wedging when strong commitment between a target and a competitor poses a severe threat.

This theoretical advancement has sparked debates over what determines a state’s choice of wedging strategy, as well as the conditions affecting its effectiveness. Yoo argues that a target’s attitude towards the divider is a crucial factor in strategy selection.Footnote 21 Examining China’s soft and lenient policy towards Japan in the 1950s, she suggests that reward wedging is feasible when a target lacks strong commitment to a competitor and is open to cooperation with the divider, even in the absence of sufficient reward power. Focusing on established alliances, particularly asymmetric ones, Huang contends that the type of interdependence between alliance members influences the outcome of wedging strategies.Footnote 22 In other words, the relationship between a target and a competitor is key to determining a divider’s wedge strategy. Regarding China’s wedge strategy towards the US–Australia alliance, Chai finds that China’s approach is shaped by the nature of its trans-state channels and the target’s regime type.Footnote 23 Ling examines wedging from both the divider’s and the target’s perspectives, arguing that the strategic interests and resources of a divider, along with the strategic resistance and domestic preferences of a target, jointly shape the effectiveness of wedging strategies.Footnote 24

Despite significant advancements in wedging theory, existing research remains largely rooted in the theoretical framework established by Crawford and Izumikawa, which classifies policy choices into two main types. These studies overwhelmingly focus on three key actors: the divider, the competitor, and the target.Footnote 25 Although some scholars propose a third approach, a ‘wait-and-see’ or ‘do-nothing’ strategy, where a divider allows alliances to evolve without interference,Footnote 26 or attempt to develop their own typologies,Footnote 27 these alternative models remain marginal in the literature. While Crawford has explored cases where multiple states act as a divider, existing research largely focuses on how a single divider influences a single target’s alignment, leaving multi-target wedging insufficiently examined. In practice, however, strategic environments are more complex, requiring dividers to manage multiple targets simultaneously. Exploring empirical cases of multi-target wedging enhances our understanding of how dividers calibrate their strategies to erode cohesion between targets and competitors while avoiding alienation.

Regarding China’s approach towards Japan and South Korea within the context of US-led trilateral security cooperation, evidence suggests a pattern of behaviour consistent with wedging, aimed at weakening the trilateral partnership in Northeast Asia, although some responses may be adaptive. While existing studies have touched on China’s wedging strategy towards Japan and South Korea,Footnote 28 the scholarship remains limited in its exploration of this specific case. First, there has been insufficient attention to China’s role in the dynamics of US–Japan–South Korea trilateralism. Empirical studies have historically examined wedge strategies during the world wars and the Cold War. Although recent research has shifted towards post–Cold War contexts, such as Russia’s actions in the European Union,Footnote 29 Saudi Arabia’s regional manoeuvres,Footnote 30 and China’s engagement with US-led alliances in Asia,Footnote 31 studies specifically addressing China’s strategy towards Japan and South Korea within the framework of US-driven trilateral cooperation remain scarce and are often overshadowed by the broader narrative of China–US relations.Footnote 32 Second, from a theoretical perspective, while China’s actions exhibit wedging intentions, current conceptualisations of wedging approaches fail to fully capture China’s restrained posture towards both the fissures and rapprochement between Japan and South Korea within US-led trilateralism.

Given these empirical and conceptual gaps, this paper introduces the concept of soft wedging as a necessary refinement that expands the theoretical framework of wedging, providing a more precise analysis of China’s strategic behaviour towards Japan and South Korea.

Soft wedging: An alternative to hard wedging and an extension of wedging strategies

The literature on wedge strategies has predominantly focused on selective accommodation and coercive wedging as the primary methods employed by a divider. This presents a binary framework that overlooks cases where a divider, despite possessing wedging aspirations, pursues subtler actions without resorting to overt material concessions or coercion. China’s approach towards Japan and South Korea within the US-led trilateral framework exemplifies this gap.

Conceptualising soft wedging

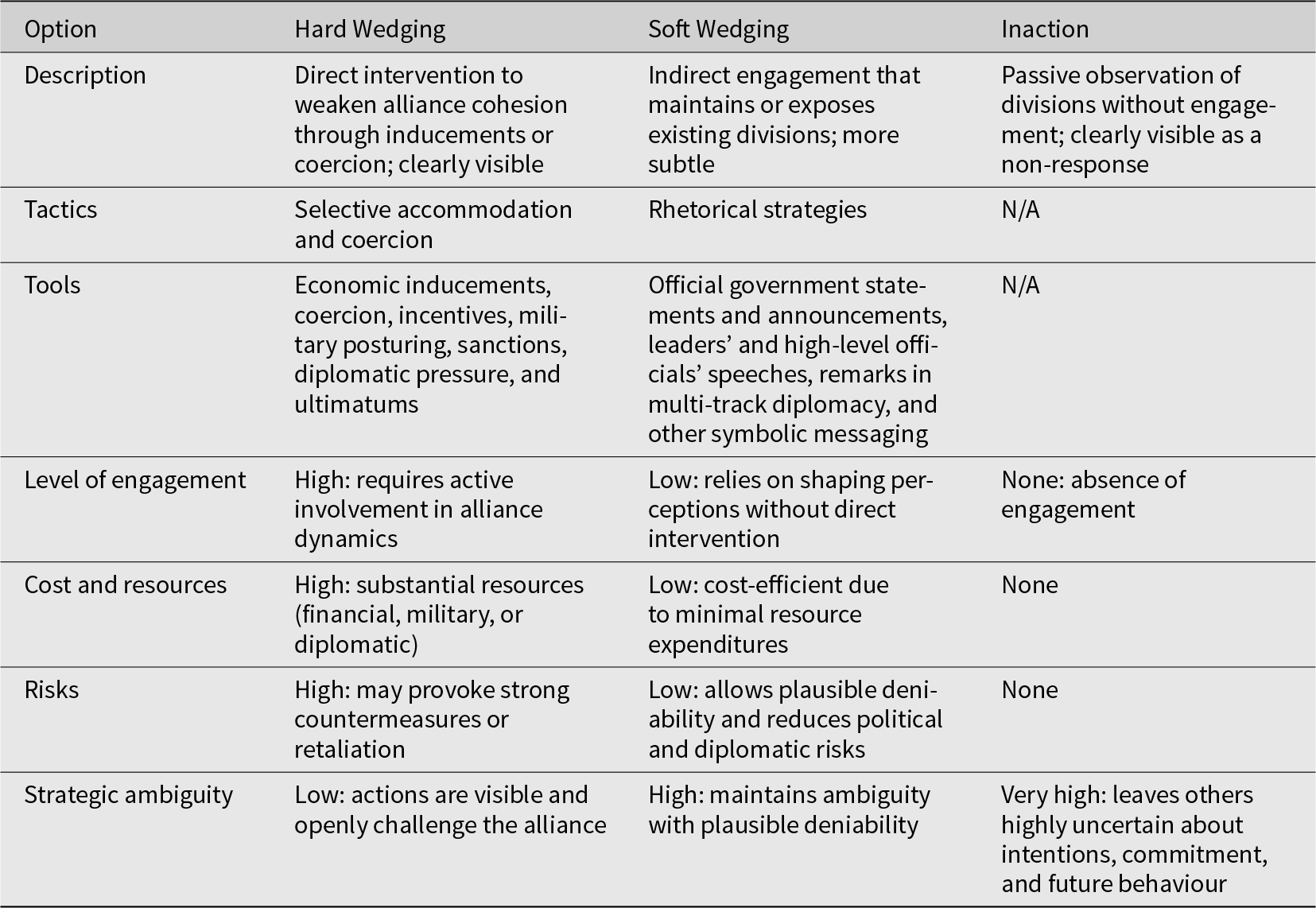

This paper introduces ‘soft wedging’ as a conceptual extension of traditional wedging strategies, refining the existing framework by distinguishing between hard and soft wedging. Existing discussions primarily differentiate tactics based on the resources employed: selective accommodation relies on inducements and concessions, whereas coercive wedging employs pressure, economic leverage, or even military threat. Despite these differences, both strategies share a common feature: the divider actively intervenes in the dynamics of a (potential) alliance. This study classifies such tactics under a single category – hard wedging – as they are characterised by direct engagement, tangible costs, high-risk interventions, and clear visibility. The tools of hard wedging encompass substantial measures such as economic inducements, coercion, incentives, military posturing, sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and ultimatums.

In contrast, soft wedging serves as an alternative approach to hard wedging, defined as a strategy in which the divider seeks to achieve its wedging goal by maintaining or exposing existing divisions within a (potential) alliance through indirect engagement. This approach relies on rhetorical methods to subtly shape perceptions, reinforce divisions, and discourage deeper collaboration among targets, all while maintaining lower costs, minimal risks, and plausible deniability. The tools of soft wedging include official government statements and announcements, leaders’ and high-level officials’ speeches, remarks in multi-track diplomacy, and other symbolic messaging, which allow the divider to influence alliance dynamics without direct intervention in disputes.

It is important to distinguish soft wedging from endorsement, a form of selective accommodation. First, endorsement involves ‘the divider insert(ing) itself into the dispute by backing one side, with greater or lesser levels of commitment’,Footnote 33 whereas soft wedging does not necessitate explicit support for one party. Second, endorsement is typically applied in cases where the interests at stake are less critical to the divider than to the disputants,Footnote 34 whereas soft wedging, which is not bound by such constraints, can be employed even in disputes directly relevant to the divider’s strategic objectives and interests.

Beyond the tools employed, the distinction between hard and soft wedging also involves differences in costs, risks, and strategic ambiguity. Crawford discusses the expenses associated with selective accommodation, particularly the concessions a divider must offer.Footnote 35 Izumikawa argues that while coercive wedging typically entails higher costs, the cost of reward wedging (or selective accommodation) can also escalate if a divider and its competitor engage in a bidding competition to win over a target.Footnote 36 Hard wedging, regardless of the specific tactic employed, requires significant resource investment and incurs certain costs due to its direct and confrontational nature, which may provoke strong countermeasures. In contrast, soft wedging involves minimal direct intervention in existing disputes because it relies on rhetorical strategies, making it a comparatively cost-efficient approach that reduces resource expenditures. Moreover, in interactions with the target(s) and the competitor, the risk of retaliatory actions significantly influences the costs associated with each approach. Soft wedging reduces political or diplomatic risks by maintaining distance from intra-bloc disputes and preserving plausible deniability. By avoiding overt inducements or coercion, it minimises the likelihood of direct retaliation from the competitor – a critical consideration, especially when the competitor is a major power. Given these dynamics, soft wedging serves as a lower-cost, lower-risk alternative to hard wedging, enabling the divider to influence alliance cohesion while mitigating potential backlash.

Soft wedging, despite its ambiguity, is conceptually distinct from a ‘wait-and-see’ or ‘do-nothing’ strategy – namely, inaction. Some studies acknowledge inaction as a tertiary option beyond selective accommodation and coercion. However, according to Crawford’s framework, the core logic of wedge strategies requires deliberate action and an active process involving intentional intervention or strategic effort. The inaction approach, as its name implies, refers to a posture of passive observation, in which a state refrains from engagement. It lacks the proactive measures necessary to qualify as wedging. This further distinguishes it from soft wedging, which, although limited in intensity and indirect in form, still entails some degree of engagement, resource expenditure, and exposure to the risk of retaliation. In this context, one could argue that inaction may exhibit a higher degree of strategic ambiguity than soft wedging, as it leaves other states more uncertain about a state’s intentions, level of commitment, or likely future behaviour. In short, if no purposeful rhetorical or symbolic act is undertaken, the state is not wedging at all; it is simply inactive.

Table 1 summarises the key distinctions among hard wedging, soft wedging, and inaction.

Table 1. Comparing hard wedging, soft wedging, and inaction.

Although this paper introduces soft wedging to fill a conceptual gap in the existing literature, it is important to acknowledge that both soft and hard wedging have been observed in other historical and contemporary cases. For example, during the Cold War, the Soviet Union’s efforts to sow disunity between the United States and its European allies through propaganda and selective diplomacy can be seen as instances of soft wedging, whereas Russia’s hardline attempts to prevent North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) expansion during the late twentieth century exemplify hard wedging. Similarly, China’s diplomacy in Southeast Asia can at times be characterised as a soft wedging strategy aimed at pulling regional states away from US influence, particularly through its rhetoric promoting an ‘Asia–Pacific Community with a Shared Future’, which appeals to regional ambivalence towards US involvement. This contrasts with China’s hard wedging tactics, such as its use of pressure in the South China Sea disputes.

Conditions favouring soft wedging

Due to the fundamental differences between soft and hard wedging, we suggest that soft wedging may be preferable for the divider under two general conditions. First, when the divider seeks to achieve its strategic objectives while minimising direct confrontation and resource expenditures. Second, when the divider aims to maintain a façade of detachment to avoid overt alignment with one side while subtly influencing alignment dynamics. These conditions make soft wedging an attractive option for states aiming to weaken alliances without antagonising targets or competitors.

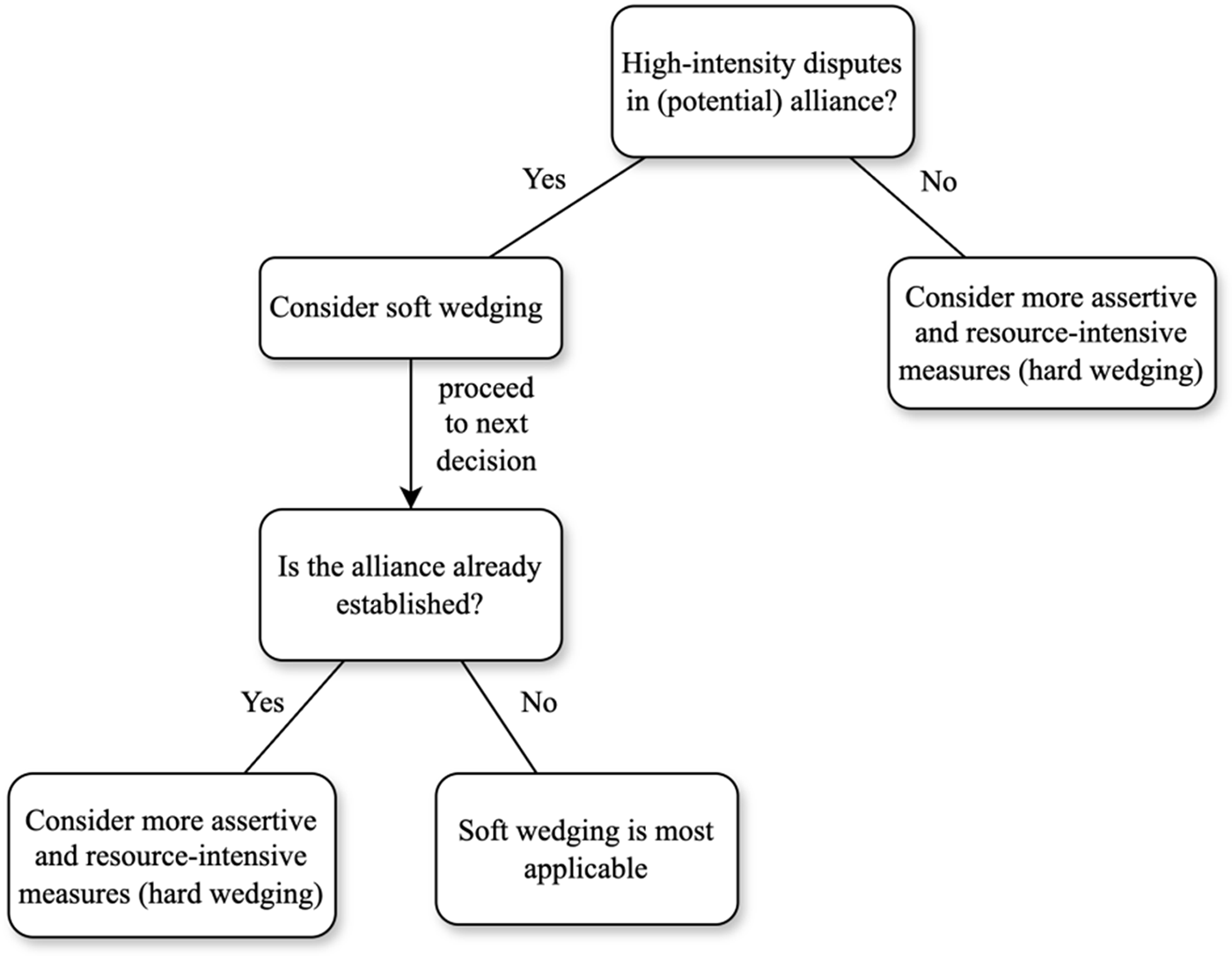

However, two additional factors influence the choice of soft wedging for a divider: the intensity of disputes within a (potential) alliance and the divider’s specific wedging goal. Soft wedging is particularly applicable when the divider seeks to prevent the formation of an adversarial alliance characterised by a high intensity of internal disputes, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decision tree for selecting soft wedging.

First, the intensity of disputes directly affects the cohesion of the (potential) alliance. High-intensity disputes arise from substantial domestic political sensitivities, including historical and territorial issues, which are difficult to compromise on, prone to resurfacing, and capable of spilling over into other areas of cooperation. In such cases, sustaining cohesion becomes increasingly challenging, reducing the necessity for costly wedging strategies since the likelihood of long-term cooperation diminishes. Conversely, low-intensity disputes typically stem from external manipulation of secondary interests, such as assets in peripheral areas, existing alliance ties, economic relationships, and market positions.Footnote 37 When disputes are mild, alliance cohesion tends to be robust, increasing the likelihood of unity among targets and prompting the divider to consider more aggressive and resource-intensive measures to disrupt it.

The choice of wedging strategy also depends on whether the target alliance is already established or remains in formation, as this affects both the perceived threat level and the feasibility of influencing its trajectory. An established alliance refers to ‘formal associations of states for the use (or non-use) of military force, intended for either the security or the aggrandisement of their members, against specific other states, whether or not these others are explicitly identified’,Footnote 38 often institutionalised through formal commitments and military or security obligations. In such cases, a divider’s wedging objectives typically fall into one of three categories: realignment, dealignment, or disalignment. By contrast, potential alliances are still forming, making prealignment, the prevention of alliance formation, the primary wedging goal.

To weaken an established alliance, a divider may exacerbate differences in alliance goals, burden-sharing expectations, or strategic priorities, thereby encouraging targets to reconsider their commitments. Once alliance obligations are formalised, members are more likely to feel constrained by their commitments. Additionally, an already established adversarial alliance poses a more tangible security threat to the divider than a merely prospective one. Consequently, a divider facing a well-established alliance may be more inclined to adopt relatively costly wedging strategies. Conversely, when seeking to dissuade targets from joining an adversarial bloc, a divider can highlight the risks of alignment while downplaying its benefits. Target states are often more flexible before formalisation, making it easier to preserve their neutrality than to disengage them once they have formally entered an alliance.Footnote 39 Because a potential alliance has not yet materialised into an immediate threat, the divider can employ less costly wedging strategies to undermine its development.

In cases where a potential adversarial alliance experiences high-intensity internal disputes, soft wedging becomes a strategically prudent approach. Deep-seated disputes create substantial obstacles for the parties involved in reconciling and uniting, thereby facilitating the divider’s wedging efforts. Moreover, in such cases, hard wedging might prove counterproductive, as external pressure could inadvertently unify targets against the divider by creating a rallying point that redirects public focus and ire towards it. Soft wedging may mitigate this risk by subtly reinforcing existing divisions without escalating tensions, ensuring that targets remain distrustful of one another rather than forming a united front against the divider. This strategy is particularly advantageous when the divider’s goal is to prevent alignment, as it allows for a subtler, less confrontational form of influence that is less likely to provoke countermeasures. By contrast, hard wedging requires direct engagement in ongoing disputes, risking the alienation of other entities within the potential alliance and potentially damaging the divider’s bilateral relations with them.

As dispute intensity diminishes and alliance cohesion strengthens, the divider may be compelled to adopt more assertive and resource-intensive hard wedging strategies. This necessity holds true regardless of whether the alliance poses an immediate threat, as the potential for future consolidation and opposition may necessitate pre-emptive measures. Similarly, when facing an established alliance that presents a direct strategic challenge, the divider may undertake costly measures to mitigate the risk, irrespective of any limited internal disputes among the allied states.

In addition to the factors discussed above, economic interdependence between the divider and the targets may also influence the selection of soft or hard wedging, as it directly affects the resources available to the divider and the costs associated with intervention. However, this impact is complex and highly context-dependent, varying based on the relative dependence between the divider and the target states. In cases of asymmetric interdependence, where the target is more reliant on the divider, the divider may be more inclined to leverage economically coercive measures, as such actions are less costly. Conversely, when the divider is more economically dependent on the target, the feasibility of economic coercion decreases, as such measures would impose higher economic costs on the divider itself. In situations of symmetric interdependence, where both parties rely heavily on one another, the mutual economic risks may constrain the divider from pursuing coercive actions altogether. While economic interdependence is a relevant consideration, it primarily influences the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of specific tactics rather than the overall strategic approach, making it secondary to the intensity of intra-alliance disputes and the divider’s strategic objectives.

In the Crawford–Izumikawa debate, there is no scholarly consensus on whether selective accommodation or coercion is inherently more effective, as scholars emphasise condition-dependent factors in their analyses. While hard wedging may produce more immediate and measurable results, its higher costs and risks make it less sustainable in certain contexts. Meanwhile, the effectiveness of soft wedging depends on the nature of the targeted alliance – whether it is a formal alliance, an emerging security partnership, or a looser coalition – as well as the level of existing disputes between the targets. This study, therefore, focuses on identifying the conditions under which soft wedging is most applicable as a strategic alternative, rather than assessing its effectiveness relative to hard wedging.

Analysis of China’s soft wedging to the Japan–South Korea entente within the US–Japan–South Korea trilateral security cooperation

The US has long played a critical role in fostering closer ties between its Northeast Asian allies by encouraging rapprochement between Japan and South Korea. Trilateral cooperation began gaining momentum in the late 1990s and became a strategic focus under the Obama administration. Despite intermittent setbacks, these efforts achieved results,Footnote 40 culminating in the 2023 Japan–South Korea rapprochement and the Camp David Summit, which sought to institutionalise trilateral security cooperation. Although many of the commitments made have yet to be fully realised and tangible progress remains limited, the Camp David Declaration explicitly identified China as a shared concern. This marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of the trilateral framework, endowing it with greater permanence and strategic salience from Beijing’s perspective.

In response to the United States’ deepening trilateral security cooperation with Japan and South Korea since the early 2010s, China has voiced consistent opposition, viewing joint military exercises as a source of regional instability.Footnote 41 It has framed trilateralism as an exclusionary circle, likening it to other US-led initiatives like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), which Beijing criticises for prompting a ‘Cold War mentality’ and exacerbating regional fragmentation and confrontation.Footnote 42

China’s opposition has not been limited to rhetoric. It has taken substantial measures to counter the emerging trilateral security partnership, most notably through economic and diplomatic coercion during the deployment of the THAAD system in South Korea. While often portrayed as a bilateral issue between Washington and Seoul, China viewed THAAD as a precursor to deeper trilateral security coordination. Its opposition was twofold: first, stemming from immediate concerns about the strategic implications of the missile system, particularly in the context of Washington’s military expansion in the region, as THAAD’s radar coverage extends far beyond South Korea’s defensive needs and reaches deep into the Asian hinterland;Footnote 43 and second, from broader apprehensions over the potential consolidation of US-led trilateral security cooperation. These concerns were reflected in South Korea’s ‘Three Noes’ statement, which included a pledge not to establish a formal trilateral military alliance with the United States and Japan.Footnote 44 In retrospect, China’s response to the THAAD deployment, characterised by economic and diplomatic coercion, represents a clear instance of hard wedging. This behaviour was driven not only by concerns about US–South Korea missile defence cooperation but also by a deeper strategic objective: to prevent the formalisation of a trilateral military alliance. Although the coherence of China’s foreign policy decisions can be difficult to assess at times, its opposition to THAAD and its vocal criticism of US–Japan–South Korea trilateralism are consistent with the core logic of wedging – namely, aiming to weaken or prevent the consolidation of countervailing alliances.

However, in contrast to its assertive response to the THAAD episode and the broader trilateral framework, China’s approach to the Japan–South Korea entente within this structure has been markedly more restrained. We argue that these situational reactions towards Japan and South Korea reflect a consistent behavioural pattern that can be characterised as a soft wedging strategy, as theorised in this paper. Rather than resorting to inducements or coercion, China has relied on rhetorical tactics, such as emphasising its longstanding friendship with South Korea, highlighting Japan’s historical aggressions, and drawing attention to persistent historical disputes between the two countries. In this scenario, China plays the role of the divider, with Japan and South Korea as the targets, and the US as the competitor. This strategy is both cost-effective and strategically cautious: it prevents China from becoming directly entangled in bilateral tensions, thus avoiding the alienation of either target or inadvertently pushing them closer to the competitor. China’s approach is shaped by the enduring nature of Japan–South Korea disputes and its wedging goal in Northeast Asia.

Based on official statements and expert interviews with policy analysts from China, Japan, and South Korea,Footnote 45 the following sections examine China’s response to the Japan–South Korea rapprochement and the broader dynamics within the trilateral security partnership since the early 2010s. We then analyse how China has employed rhetorical strategies as a form of soft wedging and explore the strategic rationale behind this approach. Our aim is not to argue that China exerted influence over the trajectory of Japan–South Korea relations, nor to present these developments as ‘successes’ of wedging. Rather, we use episodes of reconciliation and tension between Japan and South Korea to illustrate a key dimension of China’s soft wedging strategy: its preference for rhetorical restraint and indirect engagement, especially in contexts where direct intervention was either unnecessary or politically risky.

China’s restrained response to Japan and South Korea under the United States’ trilateral partnership ambitions

The United States has made consistent efforts to strengthen Japan–South Korea relations as part of its broader goal of establishing a trilateral security partnership. These efforts yielded developments such as the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), the Comfort Women Agreement, and other steps towards bilateral reconciliation. Although these agreements are bilateral in form, they were widely regarded as achievements of trilateral cooperation and as foundational steps towards deeper strategic alignment among the three countries. While China has expressed dissatisfaction with such US efforts and initiatives, it has generally adopted a restrained posture and has refrained from direct intervention in these developments.

The signing of GSOMIA in 2016 was intended to enhance military diplomacy between Japan and South Korea and accelerate trilateral military coordination on ballistic missiles.Footnote 46 Initially proposed by Japan in 2010, the agreement faced delays due to strained Japan–South Korea relations. However, persistent US mediation led to its finalisation in November 2016.Footnote 47 From China’s perspective, GSOMIA solidified the foundation for a more formal trilateral alliance and posed a challenge to regional stability.Footnote 48 Despite its opposition, China refrained from taking substantial actions to disrupt this cooperation, marking a contrast to its economic retaliation against South Korea following the THAAD deployment.

Another significant development in Japan–South Korea relations was observed in the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement, under which Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and President Park Geun-hye committed to completely and irreversibly addressing this dispute. The US also played a critical role in encouraging amicable discussions,Footnote 49 with Japan issuing an apology and financial support, while South Korea pledged to collaborate on resolution efforts.Footnote 50 Although the Moon administration later sought to renegotiate the agreement and dissolved the foundation, the deal represented a significant step towards resolving historical grievances.Footnote 51

China’s reaction to these developments has been multifaceted. First, it urged Japan to confront and reflect on its wartime history while avoiding direct criticism of either Japan or South Korea or commenting directly on Seoul’s stance. In its official statements, China emphasised Japan’s responsibility to acknowledge its wartime aggression and take historical accountability to restore trust.Footnote 52 This rhetoric subtly signalled China’s dissatisfaction with Japan and its reconciliation with South Korea under the US-led framework. However, when addressing the improvement in Japan–South Korea relations following this agreement, China expressed cautious optimism, stating that it hoped the agreement would contribute to regional stability.Footnote 53 Despite its scepticism, China adopted a non-adversarial position, refraining from expressing overtly negative sentiments. This calculated approach allowed China to voice reservations about deepening Japan–South Korea cooperation under the trilateral partnership while avoiding an escalation of tensions in its bilateral relations with either country.

The Japan–South Korea reconciliation in early 2023 opened new avenues for bilateral cooperation and the strengthening of the trilateral security partnership. As the first such meeting in twelve years, President Yoon’s historic visit to Tokyo and the resolution of longstanding disputes signified a ‘ground-breaking new chapter of cooperation and partnership’.Footnote 54 When asked about its stance on this visit and the deepening Japan–South Korea cooperation, China responded with a familiar pattern of rhetorical restraint and strategic ambiguity. Specifically, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson stated that ‘China opposes certain countries’ attempts to form exclusionary cliques’,Footnote 55 a phrase frequently used to criticise US-led security arrangements in Asia, including the US–Japan–South Korea trilateral partnership. By framing the Yoon–Kishida summit within this narrative, China subtly linked the meeting to broader US-led trilateral efforts. The following neutral comment, ‘we hope Japan–ROK ties will move forward in a way that is conducive to regional peace, stability, and prosperity’,Footnote 56 can be understood as a subtle expression of discontent with Japan–South Korea rapprochement under US influence, as China views this as a step towards ‘exclusionary cliques’ and considers the current trajectory of Japan–South Korea relations potentially destabilising.Footnote 57

Within the framework of the US–Japan–South Korea trilateral security partnership, Japan–South Korea relations represent the most vulnerable link, strained by historical, territorial, political, and economic disputes. Rather than employing hard wedging tactics, China has distanced itself from these conflicts. During the 2019 Japan–South Korea trade disputes, it even positioned itself as a mediator, emphasising the mutual economic significance of China, Japan, and South Korea.

The territorial dispute over Takeshima/Dokdo (Liancourt Rocks) between Japan and South Korea, which has persisted since the end of World War II, escalated when President Lee Myung-bak visited the disputed islets in August 2012, a move perceived as provocative by Japan. Japan proposed resolving the dispute through the International Court of Justice, but South Korea rejected this approach.Footnote 58 In March 2013, the attendance of a high-ranking Japanese official at the ‘Takeshima Day’ celebrations triggered a significant backlash from South Korea, intensifying diplomatic tensions.Footnote 59 These strains were further exacerbated by Japan’s sovereignty claims and South Korea’s defensive exercises on the disputed islets.Footnote 60

Similarly, historical disputes resurfaced during this period, particularly regarding the comfort women issue. Japan’s denial of the 1993 Kono Statement and visits by officials to the Yasukuni Shrine heightened tensions.Footnote 61 The suspension of China–Japan–South Korea trilateral summits and Japan–South Korea bilateral meetings underscored the fragility of their ties. Although the Comfort Women Agreement and GSOMIA, facilitated by the United States, temporarily improved bilateral relations, enduring historical grievances, military tensions over disputed islands, trade issues, and South Korea’s reluctance to renew agreements led to a sharp decline in Japan–South Korea relations by the late 2010s.Footnote 62

China has navigated these rifts cautiously. Regarding territorial disputes, China has only responded when Japan conflates Dokdo/Takeshima with the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands or invokes broader historical grievances.Footnote 63 China’s stance on historical issues related to Japanese militarism has remained largely consistent. For example, it has maintained a seemingly neutral stance on the comfort women dispute between Japan and South Korea, limiting its statements to subtle expressions of concern when Japan and South Korea move towards deeper security cooperation under US leadership. In response to the trade conflict, China adopted a constructive approach, seeking to mediate tensions through institutional mechanisms aimed at regional economic development. Specifically, China actively improved its relations with Japan, facilitated diplomatic dialogue between Japan and South Korea during foreign ministerial meetings it hosted,Footnote 64 promoted trilateral cooperation involving both states to foster mutual understanding, and included discussions on a potential China–Japan–South Korea Free Trade Agreement in summit agendas.Footnote 65

China’s use of public statements and diplomatic engagements as soft wedging

Although one might argue that Beijing had limited room or strategic necessity to intervene in developments such as GSOMIA, the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement, and broader historical, territorial, and trade disputes between Tokyo and Seoul, its restrained approach in these cases diverges from both traditional wedging strategies and its more assertive behaviour during the THAAD deployment. Nevertheless, we contend that China’s response still reflects a deliberate wedging strategy towards the Japan–South Korea entente within the trilateral framework, for two primary reasons.

First, China intends to exploit existing divisions within the trilateral partnership, particularly between Japan and South Korea, to hinder deeper security cooperation and ultimately prevent the institutionalisation of a trilateral military alliance. Second, both Japan and South Korea perceive China’s behaviour as an attempt to leverage their historical disputes to weaken their bilateral relations. In this sense, China’s actions are viewed by both parties as deliberate measures to drive a wedge between them.

China’s strategic vigilance is evident in its close monitoring of developments in US–Japan–South Korea security cooperation and Washington’s broader efforts to strengthen Tokyo–Seoul ties. While trilateral coordination primarily aims to counter North Korea’s nuclear threat, China advocates for denuclearisation through diplomacy rather than military deterrence. Additionally, the trilateral partnership implicitly casts China as a threat or challenge. These factors motivate China to drive a wedge between Japan and South Korea, aiming to thwart the formation of a trilateral military alliance in Northeast Asia and to weaken the growing alignment between Japan and South Korea within this context.

This dynamic illustrates China’s position as the divider, with the US as the competitor and Japan and South Korea as the targets. How Japan and South Korea perceive China’s actions is an important factor in assessing its strategy. Insights from analysts in both countries suggest that China’s rhetoric and diplomatic behaviour have had a wedging effect. Retired Japanese Navy Admiral Yoji Koda notes that China viewed differences between Japan and South Korea as opportunities to undermine their relations.Footnote 66 Scholars such as Tosh Minohara and Hiroyasu Akutsu, as well as an anonymous Japanese policy analyst, agreed that China primarily utilised Japan’s and South Korea’s economic interests to exert its influence.Footnote 67 Similarly, a South Korean scholar noted that China sought to leverage any conflicts between Tokyo and Seoul to exclude South Korea from trilateral cooperation, given that the South Korea–Japan relationship is the weakest link in the trilateral framework.Footnote 68

Although China has employed wedging tactics towards Japan and South Korea within the US-led trilateral framework due to its intentions and the targets’ perceptions, it has strategically avoided direct interventions or substantial measures. Existing wedging typologies do not fully explain the form and function of China’s approach in this case. Instead, its approach, though neither monolithic nor flawlessly orchestrated, nonetheless reflects the characteristics of soft wedging. On the one hand, China avoids antagonising or alienating Japan by adopting a seemingly neutral or restrained tone on bilateral issues. On the other hand, it uses rhetorical strategies, including official statements and announcements, diplomatic remarks, and engagement in multi-track diplomacy, to directly target South Korea, aiming to influence its willingness to closely align with Japan and the United States.

Specifically, China’s soft wedging approach can be categorised into two main strategies. First, China recalls Japan’s wartime aggression while carefully avoiding direct criticism of South Korea. Through the selective use of historical narratives, China reminds South Korea of their shared history of victimisation and reinforces their mutual concerns about Japan. A notable example of this was President Xi Jinping’s 2014 visit to Seoul, the first time a Chinese leader visited South Korea before North Korea. During a speech at Seoul National University, Xi highlighted two key points: (1) Japan’s aggression and brutality towards China and Korea during wartime and the twentieth century, and (2) the long-term friendly relations and shared historical experiences and memories between China and South Korea, particularly their resistance to Japanese invasions.Footnote 69 Several scholars from China and South Korea also suggest that China has strategically leveraged historical issues to its advantage.Footnote 70 China has conveyed its stance through Track 1.5 and Track 2 dialogues and in its government statements and announcements, where officials have consistently emphasised that facing history is essential for regional progress in Northeast Asia.Footnote 71 As noted earlier, when commenting on Japan–South Korea relations, particularly during reconciliation efforts, China has often highlighted the suffering inflicted by Japanese militarism on neighbouring countries, including China and South Korea. This pattern was evident during the signing of the Comfort Women Agreement,Footnote 72 the GSOMIA negotiations,Footnote 73 and the 2023 rapprochement between Japan and South Korea.Footnote 74

Second, China’s rhetoric sometimes emphasises cooperation with South Korea while portraying Japan as a destabilising factor in the region.Footnote 75 By framing Japan’s military posture and security alignment with the United States as a threat to regional stability,Footnote 76 China subtly suggests that South Korea should distance itself from Japan’s strategic ambitions. This approach reinforces perceptions of Japan as a revisionist power while positioning China as a cooperative and stable regional partner.

These narratives, which seek to maintain a historical lens on Japan–South Korea relations by emphasising the importance of remembering shared history, exemplify China’s strategy of keeping Japan’s past actions and unresolved historical grievances at the forefront of South Korea’s consciousness.

Experts in Seoul also suggest that these recollections of shared suffering from fighting against Japan intensify South Korea’s concerns, thereby reducing its willingness to get closer to Japan.Footnote 77 At the same time, this dynamic may fuel resentment in Japan, making Tokyo more resistant to Washington’s push for deeper Japan–South Korea security cooperation.Footnote 78 In this way, China’s rhetoric-based approach not only discourages South Korea from further aligning with Japan but also subtly shapes Japan’s perceptions of South Korea’s reliability as a security partner. This illustrates how China’s strategic use of historical disputes, combined with restrained rhetoric, serves to sustain and subtly reinforce divisions between Japan and South Korea, which is consistent with the soft wedging subcategory in a multi-target context. Moreover, throughout the analysis of Japan–South Korea rapprochement and periods of tension, China’s response has remained relatively consistent, despite changes in South Korea’s leadership, which have shaped the trajectory of bilateral relations. Beyond the THAAD episode discussed above, China has generally maintained restraint, employing subtle rhetoric and diplomatic signalling to remind Seoul of unresolved historical disputes with Japan, while avoiding direct confrontation or coercion. This pattern is evident not only during the Moon Jae-in administration but also under President Park Geun-hye and Yoon Suk-yeol, suggesting that China’s soft wedging towards the Japan–South Korea entente has been deployed when conditions – such as persistent mistrust between the two countries and China’s desire to maintain strategic flexibility – favoured a restrained posture.

Alternative explanations for China’s response to Japan and South Korea under the US’s trilateral partnership ambitions

To demonstrate why soft wedging offers the most compelling framework for understanding China’s response to the Japan–South Korea entente under US-led trilateral security cooperation, it is essential to examine alternative explanations beyond traditional wedging typologies. This section also considers how China’s approach might differ if Japan and South Korea were not US allies.

China’s behaviour cannot be fully explained by traditional balancing, soft balancing, general opposition to trilateralism, or strategic inaction. Traditional balancing, which involves countering a dominant power through military expansion and/or countervailing alliances,Footnote 79 is inconsistent with China’s restrained, non-military posture in this context. Even soft balancing, which relies on institutional contestation, diplomatic alignment, or economic tools to constrain a dominant power,Footnote 80 fails to capture the subtlety of China’s response towards Japan and South Korea. Rather than pursuing active countermeasures, China has exercised restraint across these domains. Similarly, while China has long opposed US-led trilateral security cooperation, this general opposition to trilateralism does not, on its own, account for the specific character of China’s behaviour towards Japan–South Korea rapprochement. Instead of issuing firm objections, China has maintained strategic ambiguity – balancing expressions of discontent with efforts to preserve stable bilateral ties with both countries. This suggests that opposition to trilateralism alone is insufficient to explain the pattern of behaviour observed. Strategic inaction also falls short as an explanation. While inaction and soft wedging can both produce ambiguity, inaction implies passive observation and the absence of meaningful engagement. China’s actions, although subtle and non-coercive, have been deliberate and rhetorically targeted, distinguishing them from inaction.

The logic of bandwagoning also fails to account for China’s behaviour. Rather than aligning with the dominant power or accommodating its leadership,Footnote 81 China has subtly leveraged historical grievances between Japan and South Korea, reinforcing existing divisions to weaken trilateral cohesion. This stands in direct contrast to bandwagoning, which would expect China to align more closely with the US-led order.

Hedging has been proposed as a middle-ground strategy between balancing and bandwagoning,Footnote 82 emphasising strategic ambiguity to mitigate risks in uncertain geopolitical environments.Footnote 83 On the surface, China’s rhetorical ambiguity may appear consistent with hedging. However, China’s behaviour in this case goes beyond mere ambiguity. It includes targeted rhetorical efforts, such as invoking shared historical trauma with South Korea or subtly discrediting Japan’s security ambitions to discourage South Korea from deepening security ties with Japan, a pattern noted by analysts in China, Japan, and South Korea. This deviates from the essence of hedging, which generally seeks to avoid taking sides or engaging in direct involvement.

Economic interdependence may partly explain China’s reluctance to employ coercion against Japan and South Korea, as it creates disincentives for open confrontation with major trading partners. However, it does not account for China’s preference for soft wedging over more forceful tactics in its approach to Japan–South Korea relations within the trilateral framework. Notably, China has demonstrated a willingness to use economic coercion against South Korea, as seen in the aftermath of its THAAD deployment, which also involved trilateral considerations. Thus, economic interdependence alone is not a decisive factor in China’s strategic calculus towards the Japan–South Korea entente.

While this study focuses on the US’s efforts to strengthen Japan–South Korea relations and promote a trilateral partnership, the structure of US alliances with Japan and South Korea is a critical variable in China’s strategic considerations. The US-led initiative in Northeast Asia is built upon asymmetric bilateral alliances that afford Washington considerable influence over both Tokyo and Seoul.Footnote 84 In this context, these alliances serve as the foundation for trilateral cooperation, positioning the United States as both a unifying force and an independent influencer of its allies’ positions. China’s concerns about a formalised trilateral military alliance stem from not only the strengthening of Japan–South Korea ties per se but also and more significantly the broader consolidation of US strategic dominance in the region. In a hypothetical scenario where Japan and South Korea were not US allies, trilateral dynamics would shift considerably. While the United States might still encourage Japan–South Korea unity, its ability to shape their policies would be significantly weaker. Consequently, China would have less incentive to drive a wedge, as the risks associated with closer Japan–South Korea alignment on security issues would be lower. Although historical and territorial disputes between Japan and South Korea would still create exploitable divisions, the urgency or necessity for China to act would likely diminish. Under such conditions, China might maintain an inactive posture or pursue alternative diplomatic and security strategies, rather than engaging in soft wedging.

Strategic calculus behind China’s preference for soft wedging

China’s adoption of a soft wedging strategy towards Japan and South Korea can be attributed to two factors: (1) the high-intensity disputes between Japan and South Korea, and (2) China’s goal of prealignment – preventing the formalisation of a trilateral military alliance.

First, disputes between Japan and South Korea are highly sensitive and resistant to resolution or compromise, as they are deeply rooted in historical, political, and territorial grievances and closely tied to shifts in domestic political leadership. Under the conservative Park Geun-hye administration between 2013 and 2017, Seoul and Tokyo made notable strides towards security and historical reconciliation amid shared concerns over North Korea, including the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement and the 2016 GSOMIA, as discussed above. However, these gains were largely reversed during the progressive Moon Jae-in administration from 2017 to 2022, as Seoul’s policy shifted and earlier agreements were effectively nullified, bringing relations back to a low point. It was not until the conservative Yoon Suk-yeol administration took office that efforts were renewed to restore bilateral cooperation to levels seen during the Park era. Alongside the leadership changes, the underlying issues between Japan and South Korea have repeatedly resurfaced, deepening mistrust and exacerbating divergent threat perceptions and conflicting policy goals.Footnote 85 For example, analysts argue that trade disputes from 2018 to 2020 and South Korea’s reluctance to renew the 2016 GSOMIA agreement, both linked to historical tensions, spilled over beyond politics into the economic and military domains.Footnote 86 Japan’s willingness to engage in bilateral and trilateral security partnerships was dampened by South Korea’s hardline stance on historical issues during this period.Footnote 87 Although the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement represented a significant step towards reconciliation, its collapse was driven by a shift in South Korea’s domestic politics. These reversals discouraged Tokyo from deepening security ties with Seoul and further heightened resentment towards its neighbour.Footnote 88 This dynamic has diminished both the strategic necessity and the opportunity for China to intervene directly. Despite the political will and strategic vision of both Tokyo and Seoul to strengthen their relationship within the framework of their respective alliances with Washington, unresolved disputes continue to obstruct substantive progress. As such, China’s soft wedging can be understood as a calculated response to both leadership preferences in Seoul and the broader fragility of Japan–South Korea relations.

These enduring grievances serve as formidable barriers to Japan–South Korea relations, fuelling animosity and complicating cooperative efforts.Footnote 89 While the three countries have achieved some degree of trilateral coordination, ties between Japan and South Korea remain fragile. China’s wedging attempts must therefore be understood in the context of these fluctuations and entrenched bilateral disputes. Recognising the persistent fragility of Japan–South Korea relations and the low likelihood of sustained cohesion between them, China has had little strategic incentive to pursue costly or high-risk wedge strategies. Instead, by subtly reinforcing existing divisions, particularly during periods of progressive leadership that tend to adopt a more critical stance towards Japan, China seeks to achieve its goal of weakening trilateral security coordination without direct confrontation. Even in the context of the 2023 Japan–South Korea rapprochement and the rapid development of the trilateral security partnership, China’s wedging efforts appear to have had limited influence. Yet, many analysts maintain that the deep-rooted animosities between Tokyo and Seoul will remain a major impediment and continue to pose significant challenges to long-term cooperation.Footnote 90

Second, while the United States endeavours to solidify trilateral cooperation, this partnership has not evolved into a formal military alliance. China’s strategic objective, in this case, is prealignment – preventing such an alliance from forming. Rather than seeking to exclude the United States from regional dynamics, China aims to cultivate regional cooperation and stability by engaging with various actors and preventing bloc-based confrontations.Footnote 91 China’s multilateral ambitions are evident in its efforts to establish trilateral cooperation mechanisms with Japan and South Korea.Footnote 92 Despite strained relations, China has continued diplomatic engagement, recognising the importance of the US’s role in the region.Footnote 93

Thus, the combination of high-intensity Japan–South Korea disputes and China’s objective of preventing the formalisation of a trilateral alliance makes soft wedging the most pragmatic choice. Compared to hard wedging tactics such as economic coercion or direct diplomatic inducements, a rhetorically restrained approach imposes fewer costs on China. Moreover, applying hard wedging would risk antagonising Seoul unnecessarily, which has maintained a relatively cautious posture towards Beijing. In contrast, soft wedging allowed China to subtly reinforce existing tensions at minimal diplomatic cost. This strategy enables China to minimise resource expenditures while avoiding the alienation of either target, thereby reducing the risk of inadvertently strengthening their alignment with the United States, particularly amid Washington’s efforts to push its allies towards decoupling from China. At the same time, soft wedging allows China to subtly influence Japan–South Korea dynamics and undermine trilateral cohesion, even if its influence is secondary. This approach also aligns with China’s broader regional objectives of maintaining cooperative ties with both Japan and South Korea while avoiding direct confrontation or the risk of backlash from the United States, its competitor in this case. Given Beijing’s recognition of the fragility of Japan–South Korea relations and the recurring role of domestic political shifts in renewing tensions, soft wedging offers a pragmatic, low-cost strategy for subtly reinforcing divisions without provoking confrontation.

However, the effectiveness of China’s strategy towards the Japan–South Korea entente within the trilateral framework remains a subject of debate. In discussions of Tokyo–Seoul relations, analysts often highlight domestic political dynamics – particularly those rooted in enduring historical disputes and shaped by leadership transitions – as the primary factors driving bilateral tensions. From this perspective, one could argue that China’s influence is marginal. In our interviews, some observers attribute the sluggish progress of the trilateral partnership more to South Korea’s unstable domestic politics and leadership than to external interference, suggesting that assessing the impact of China’s policy in the region is difficult.Footnote 94 We acknowledge this limitation. Therefore, this study does not attempt to measure the direct impact of China’s behaviour, but instead contends that China’s response is best understood as consistent with a soft wedging approach – evidenced by its diplomatic conduct, strategic intent, rhetorical framing, and the perceived influence on policy discourse in both Tokyo and Seoul.

Conclusion

This paper begins with the empirical observation that while China has expressed significant concerns about the ‘exclusionary circle’ formed by the United States, Japan, and South Korea in Northeast Asia, it has not actively exploited the fragility of Japan–South Korea relations to erode their cohesion or undermine their collaboration under US leadership. This raises an analytical puzzle: What explains China’s strategic behaviour in response to Japan–South Korea rapprochement within the US-led trilateral framework?

To address this question, we assess whether China’s response aligns with a wedging strategy, given its strong opposition to the trilateral framework and the potential formation of a trilateral military alliance, as well as its broader efforts to drive wedges into other US-led alliance systems. While China’s diplomatic behaviour may at times appear reactive and driven by immediate circumstances, its actions towards Japan and South Korea in this case exhibit characteristics of wedging. However, existing wedging typologies do not fully capture the specific form of its approach.

To resolve this empirical puzzle and conceptual gap, we introduce ‘soft wedging’ as an alternative to conventional ‘hard wedging’ to explain China’s behaviour. Unlike hard wedging, which relies on material concessions, coercive pressures, and direct engagement in disputes, soft wedging operates through indirect means. It involves avoiding direct intervention while employing ambiguous rhetorical tools – such as official statements and diplomatic remarks – to subtly expose and perpetuate existing divisions. This approach is less risky and costly, requiring minimal resource expenditure, making it particularly applicable when the divider seeks to prevent an adversarial alliance from forming, especially when the involved parties are already engaged in high-intensity disputes.

Employing this framework, this paper examines China’s strategic response to the Japan–South Korea entente within the broader context of US efforts to foster a trilateral security partnership since the 2010s and explores the strategic calculus behind China’s preference for soft wedging over alternative strategies. Although harbouring wedging intentions, China refrained from selective accommodation or coercive wedging and instead adopted a soft wedging approach through rhetorical methods. Specifically, Beijing invoked historical issues when necessary in its official statements and diplomatic remarks, reminding Seoul of past experiences and the suffering inflicted by Japan’s colonial rule and wartime actions, suggesting that these should not be forgotten and that Tokyo should deeply reflect on its past aggressions. By reiterating historical grievances and keeping the fissures alive, Beijing sought to lessen Seoul’s willingness to collaborate closely with Tokyo in security and defence matters, thereby hindering the formation of the trilateral security partnership.

The rationale behind China’s behaviour also supports the argument regarding the conditions under which the soft wedging strategy is most applicable. One such condition is the high intensity of disputes between Japan and South Korea, which renders their cooperation less likely to be sustained, thereby facilitating China’s efforts to drive a wedge. Another is China’s goal of prealignment, which reduces its incentive to undertake costly and risky measures. In this situation, soft wedging emerges as the most viable strategy, as it is less resource-intensive and minimises the risk of alienating Japan or South Korea by limiting China’s direct involvement in their fissures.

The findings of this paper have both theoretical and empirical implications. First, China’s behaviour exemplifies a new type of wedging strategy: soft wedging, which serves as an alternative to hard wedging. This concept illustrates how a divider can benefit from the disagreements between targets and the competitor without relying solely on selective accommodation and coercion. By introducing soft wedging, this study expands the spectrum of wedging strategies and enhances the theoretical utility of the wedging framework. Second, unlike traditional wedging literature, which primarily focuses on a divider’s tactics towards a single target, this study examines a divider engaging with multiple targets simultaneously. In such scenarios, pre-existing disputes among targets play a more influential role, as the divider must strategically balance its bilateral relations with both targets rather than focusing on just one. By extending the theoretical framework to incorporate multi-target wedging, this research deepens our understanding of how states manage alliance politics in complex security environments. As demonstrated in China’s case, soft wedging enables a divider to exploit existing divisions without incurring high diplomatic or strategic costs in its relations with either target. This makes China’s approach a representative case of wedging behaviour in a multi-target context. Given the theoretical and empirical significance of this approach, future research should further explore multi-target wedging through additional cases and a more refined analytical framework.

From an empirical standpoint, this concept offers a more precise explanation of China’s restrained yet deliberate approach towards Japan and South Korea within US-led trilateralism. Examining the key factors influencing this case is crucial. Amid rising US–China tensions, the United States is pursuing greater strategic coordination with its allies and partners, as evidenced by its initiatives in the Indo-Pacific region and efforts to decouple from China. Meanwhile, China’s relationships with Japan and South Korea face three critical challenges: deteriorating bilateral relations with both countries, the stalled progress on the China–Japan–South Korea Free Trade Agreement since 2019, and the absence of trilateral leaders’ summits for three years. In this context, the Japan–South Korea reconciliation in early 2023 is particularly significant.

This paper contends that China has adopted a soft wedging strategy in the post-2010 period and is likely to maintain this approach despite ongoing uncertainties. On the one hand, China’s relations with Japan and South Korea will test the effectiveness of this strategy. On the other hand, high-intensity disputes between Japan and South Korea are expected to persist. While such tensions may be temporarily set aside, a lasting resolution remains elusive. Although the Camp David Summit signalled an intent to institutionalise trilateral security cooperation, marking a significant milestone, its long-term trajectory remains uncertain. This uncertainty is acknowledged by not only China but also observers in Japan, South Korea, and the United States, as several factors affect the durability and sustainability of trilateral cooperation. These include domestic political shifts in Japan and South Korea, where leadership changes may lead to fluctuating foreign policy priorities, as well as persistent historical tensions that could resurface and undermine mutual trust.Footnote 95 Moreover, rather than suggesting China has decisively prevailed in keeping Seoul and Tokyo apart, Beijing has pursued a consistent low-cost strategy that takes advantage of the rifts when they arise. Given these dynamics, how Beijing continues to respond to the evolving trilateral partnership, particularly in the context of Tokyo–Seoul relations within this framework, warrants further observation and analysis.

While this study focuses on China’s behaviour towards Japan and South Korea under the US-led trilateral framework from 2010 to 2023 – providing a preliminary assessment of the validity and relevance of soft wedging – this concept also holds potential for broader application. It may serve as a generalisable framework for analysing both wedging strategies from the divider’s perspective and alliance management strategies from the competitor’s viewpoint. To enhance its theoretical robustness, future research could examine additional historical and contemporary cases, as well as explore the conditions under which states select between soft and hard wedging, including specific variations of hard wedging. Particular attention could be given to factors such as economic interdependence, which directly affects the perceived costs, risks, and effectiveness of various wedging strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hiroyasu Akutsu, Yoji Koda, Tosh Minohara, Tomonori Yoshizaki, Hongwei Zhao, and the anonymous interviewees in China, Japan, and South Korea. They also thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, and the editors at EJIS for their support and assistance during this process.

Shuqi Wang is an assistant professor at the School of International Relations and the Research School for Southeast Asian Studies, Xiamen University, China. Her research focuses on international relations, with emphases on international security, alliance politics, and foreign policy analysis in the Asia–Pacific.

Mingjiang Li is an associate professor and Provost’s Chair in International Relations at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His main research interests include Chinese foreign policy, China–ASEAN relations, Sino–US relations, global governance, and Asia–Pacific security.