Introduction

A pebble beach is a coastal environment in which the sediment consists of particles 4–64 mm (Wentworth Reference Wentworth1922). This habitat is found only in limited regions worldwide. The Japanese Archipelago is a scarce region with well-developed gravel shores, including pebble beaches (Buscombe and Masselink Reference Buscombe and Masselink2006; Nature Conservation Breau, Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan 1998). Pebble beaches are harsh abiotic environments for most marine organisms and are formed in wave-dominated areas (Buscombe and Masselink Reference Buscombe and Masselink2006), resulting in a strong disturbance of bottom sediments (Morohashi et al. Reference Morohashi, Okamoto, Ishino, Uda, Ishikawa and Sannami2018; Uda et al. Reference Uda, Ishikawa, Sannami, Ishino, Suzuki and Okamoto2017). Furthermore, these beaches are susceptible to desiccation during low tides due to the absence of suction in their interstitial spaces (Kajihara Reference Kajihara2015). Therefore, these characteristics have led to the long-standing perception that these environments are barren and exhibit low biodiversity (Raffaelli and Hawkins Reference Raffaelli and Hawkins1999; Ronowicz Reference Ronowicz2005). In fact, epiphytic organisms (including benthic algae, which are the primary producers, and other attached organisms) are scarce (e.g. Ikehara and Hayashida Reference Ikehara and Hayashida2003; Kato Reference Kato2009).

In recent years, it has been reported that the interstitial environment (interstitial spaces of gravel shores, including pebble beaches) functions as a habitat for benthic macrofauna (e.g. Wada Reference Wada2022) and many of which have so far been reported from only this habitat (Hangai et al. Reference Hangai, Kitaura, Wada and Fukui2009; Ono and Maruyama Reference Ono and Maruyama2014; Yamada et al. Reference Yamada, Sugiyama, Tamaki, Kawakita and Kato2009; Yamashita et al. Reference Yamashita, Komai and Kon2023). Although they constitute a valuable habitat for unique macrobenthos, gravel shores in Japan are undergoing modification and reduction in size and number (Biodiversity Center of Japan, Nature Conservation Breau, Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan 2018; Kato Reference Kato2009; Nature Conservation Breau, Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan 1998). This is due to the historical lack of appreciation for their ecological and biogeographical significance, resulting in a perceived decline in macrobenthic populations within these environments. Indeed, most species inhabiting these environments have been listed as endangered species in the national or regional Red Data Books or Red List in Japan because of the artificial loss of their habitat (e.g. Japanese Association of Benthology 2012; Nature Conservation Breau, Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan 2020) and it is therefore imperative to implement their conservation (Kato Reference Kato2009; Wada Reference Wada2022). To comprehensively conservation of these macrobenthos, it is essential to understand the environments in which their partial communities dwell.

It is widely accepted that sedimentary beaches (e.g. sandy and muddy beach) exhibit a gradient of environmental factors that segregate species and communities. In particular, tidal height and sediment particle size have been identified as the primary determinants of community structure because of their significant relationship with survival [i.e. the local level of desiccation stress and the ease with which organisms can burrow into it (shelter from predators, competitors, or disturbance)] (Brown and Mclachlan Reference Brown and Mclachlan2002; Raffaelli and Hawkins Reference Raffaelli and Hawkins1999; Stephenson and Stephenson Reference Stephenson and Stephenson1972). Additionally, benthic interstitial communities in such environments change their composition in response to seasonal variations in environmental factors (e.g. Albuquerque et al. Reference Albuquerque, Pinto, Adadq and Veloso2007). Nevertheless, ecological knowledge of macrobenthic communities in pebble beach environments is scarce (Robbins and Griffiths Reference Robbins and Griffiths2023), and fauna is rarely described (Kondo and Kato Reference Kondo and Kato2022; Robbins and Griffiths Reference Robbins and Griffiths2023; Ronowicz Reference Ronowicz2005). In particular, the lack of suction in the interstitium on pebble beaches (the magnitude of desiccation stress might be high even in lower areas) and the sediment particle size being too large for organisms (it is impossible for them to burrow in any given location) may obscure these gradients and their seasonal change within the shore. Therefore, it is unclear whether the general patterns within sedimentary beaches can be applied to pebbles.

In the present study, we (i) described the interstitial macrobenthic community structure of a pebble beach; (ii) assessed its relationship with abiotic environmental characteristics, focusing on tidal level and sediment particle size; and (iii) confirmed their seasonal dynamics.

Materials and methods

Study site

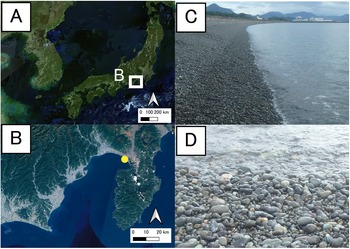

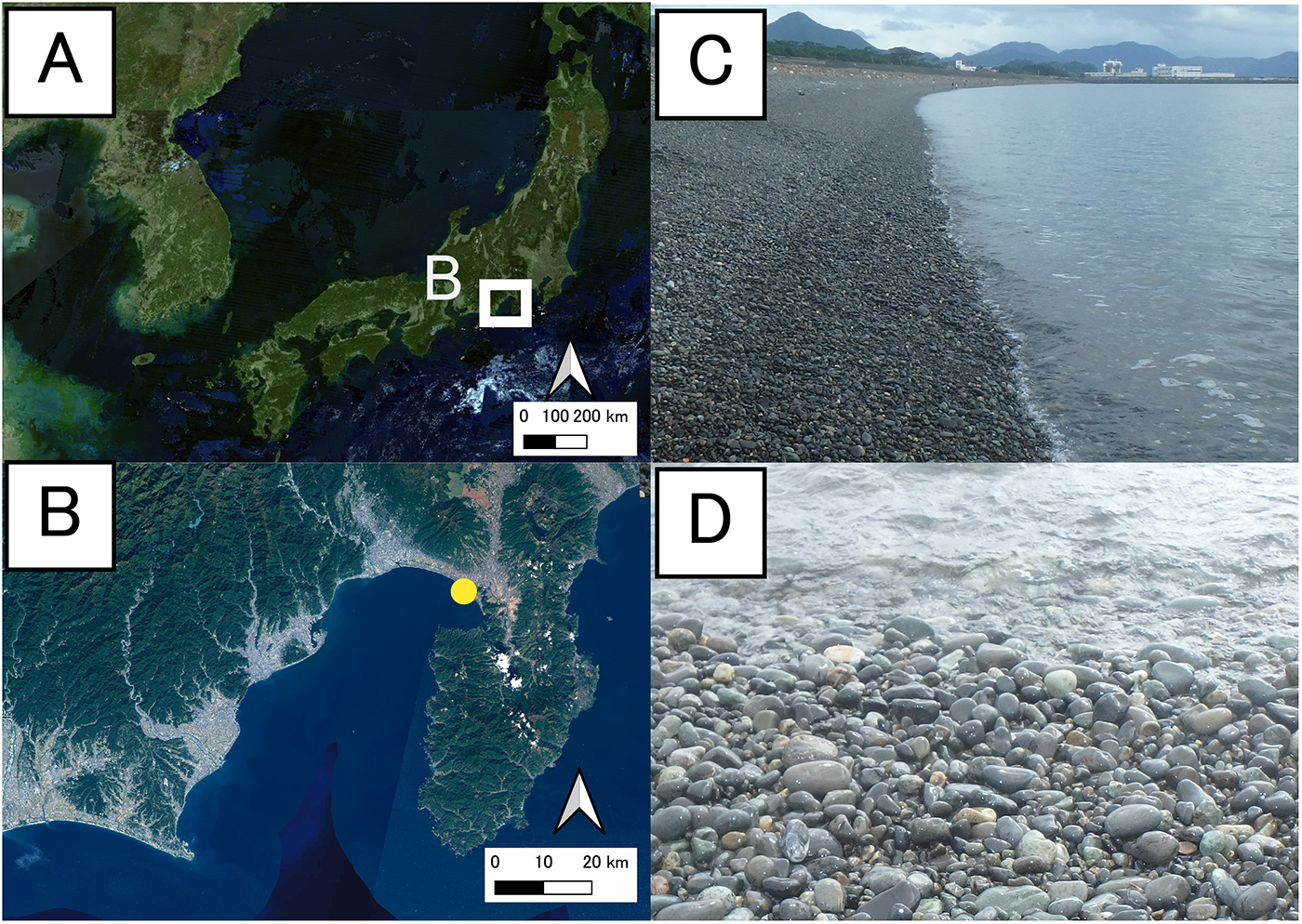

Field surveys were conducted on an intertidal pebble beach (shoreline longer than 10 km) at Higashi-makado, Numazu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, central Honshu, Japan (35°05.45’N, 138°50.37’E) (Figure 1). The daily vertical range of the tides in great tide varies between 150 and 200 cm throughout the year. This oscillation is typically amplified considerably by a strong wave. The intertidal zone was divided into three tidal levels (low, mid, and high; each varying by at least 0.3 m in height), with 8–12 stations established at each level per season (Winter: end of November to early February; Spring: early May to early June; Summer: mid-July to August; Autumn: end of October) (115 stations in total) (Table S2). The stations were positioned parallel to the shoreline with a minimum separation of 2 m between each station at the same level per season.

Figure 1. The location and landscapes of the study site, the pebble beach in Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture, central Japan. A: location; B: enlarged view of A, a yellow circle indicates the sampling site; C: landscape; D: shoreline. A and B were made after maps of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan.

Quantitative sampling of macrobenthos

At each station, a fixed amount (approximately 9 L) of sediment pebbles was excavated with a shovel from an area of 20 cm × 20 cm at a depth of 30 cm. The sediment pebble particles were removed by sieving through a 2–4 mm mesh, then macrobenthos were collected using a plankton net (mesh size: 72 μm). Macrobenthos at each station were identified and enumerated. The fragment sequence of the mitochondrial COI, 12S rRNA and/or 16S rRNA gene of each species (except for some rare or protected species) collected from the study site was determined or searched and downloaded from the GenBank database to validate identification (DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing methods are summarized in Method S1).

Abiotic environmental factor

Sediment pebbles excavated during quantitative macrobenthos sampling were used to examine the sediment particle size at each station. These sediments were then spread over a full 20 × 20 cm area and photographed, and their long and short diameters were measured from the images based on the machine learning model of Soloy et al. (Reference Soloy, Turki, Fournier, Costa, Peuziat and Lecoq2020). The median particle diameter and variation in particle size [(third quartile of particle size–first quartile)/median] within each station were calculated for both long and short diameters. The values of the long and short diameters were averaged for each index. The tidal height at each station was measured to the nearest 0.1 m using an inclinometer (Blue Level Pro 2 Digital, Shinwa Rules Co., Ltd.) and a tape measure (3X million 50 m, YAMAYO Measure Tools Co., Ltd.). These were adjusted to the relative height of the standard elevation (Tokyo Peil: T.P.) by comparison with the Shin–Nakagawa discharge outlet height, the relative height of which was already known (Morohashi et al. Reference Morohashi, Okamoto, Ishino, Uda, Ishikawa and Sannami2018), using a laser rangefinder (LM1200, Uni-Trend Technology Co., Ltd.).

Data analyses

Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H’) and Simpson’s diversity index (reciprocal: 1/λ) were calculated at each station. Macrobenthic community data (species composition based on the number of individuals) obtained at each station were classified using clustering based on the Ward method after normalizing and calculating Hellinger distances (Hellinger Reference Hellinger1909). To estimate the optimal number of groups, an estimation based on the matrix correlation (the number of groups for which the dissimilarity matrix of species composition among sites and the binary matrix of group assignments exhibiting the strongest correlation were considered to be optimal) (Borcard et al. Reference Borcard, Gillet and Legendre2018) was used. Furthermore, a bootstrap method with 1000 repetitions was employed to assess the robustness of each node. Subsequently, the indicator species for each group were identified based on the IndVal value (Dufrêne and Legendre Reference Dufrêne and Legendre1997), and their significance was evaluated using a permutation test with 10000 repetitions. Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to check the differences in each abiotic environmental factor among groups. Subsequently, the Brunner–Munzel test was used to examine which group(s) differed for each abiotic environmental factor. The Kraskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance was carried out to check the difference of each diversity index (species richness, H’ and 1/λ) among groups. The Brunner–Munzel test was used to determine which group(s) were differentiated.

A redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted for each season to assess whether environmental factors explained macrobenthic community structures. Before analysis, the abiotic environmental data were log10 ![]() $(x + 1)$ transformed to reduce variance heterogeneity (only the tidal level, which had a negative value, was converted to an absolute value before transformation). The explanatory variables for the multiple regression function were then selected from the environmental factors and their squared values (to consider the unimodal relationship) using the forward selection method, based on the coefficient of determination. The multicollinearity was checked based on the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) before attempting the RDA. In the triplot, an ellipse for the plots of each community group estimated by clustering was drawn with 80% confidence.

$(x + 1)$ transformed to reduce variance heterogeneity (only the tidal level, which had a negative value, was converted to an absolute value before transformation). The explanatory variables for the multiple regression function were then selected from the environmental factors and their squared values (to consider the unimodal relationship) using the forward selection method, based on the coefficient of determination. The multicollinearity was checked based on the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) before attempting the RDA. In the triplot, an ellipse for the plots of each community group estimated by clustering was drawn with 80% confidence.

These analyses were conducted using R ver. 4.3.2 (R Core Team 2023) with its packages: adespatial (Dray et al. Reference Dray, Blanchet, Borcard, Guenard, Jombart, Larocque, Legendre, Madi, Wagner and Dray2018), vegan (Oksanen et al. Reference Oksanen, Blanchet, Kindt, Legendre, Minchin, O’hara, Simpson, Solymos, Stevens and Wagner2013), dendextend (Galili Reference Galili2015), ggord (Marcus and Vladimir Reference Marcus and Vladimir2024), pvclust (Suzuki and Shimodaira Reference Suzuki and Shimodaira2006), and some functions made in Borcard et al. (Reference Borcard, Gillet and Legendre2018).

Results

Macrobenthic fauna of the pebble beach

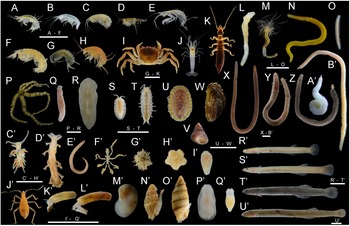

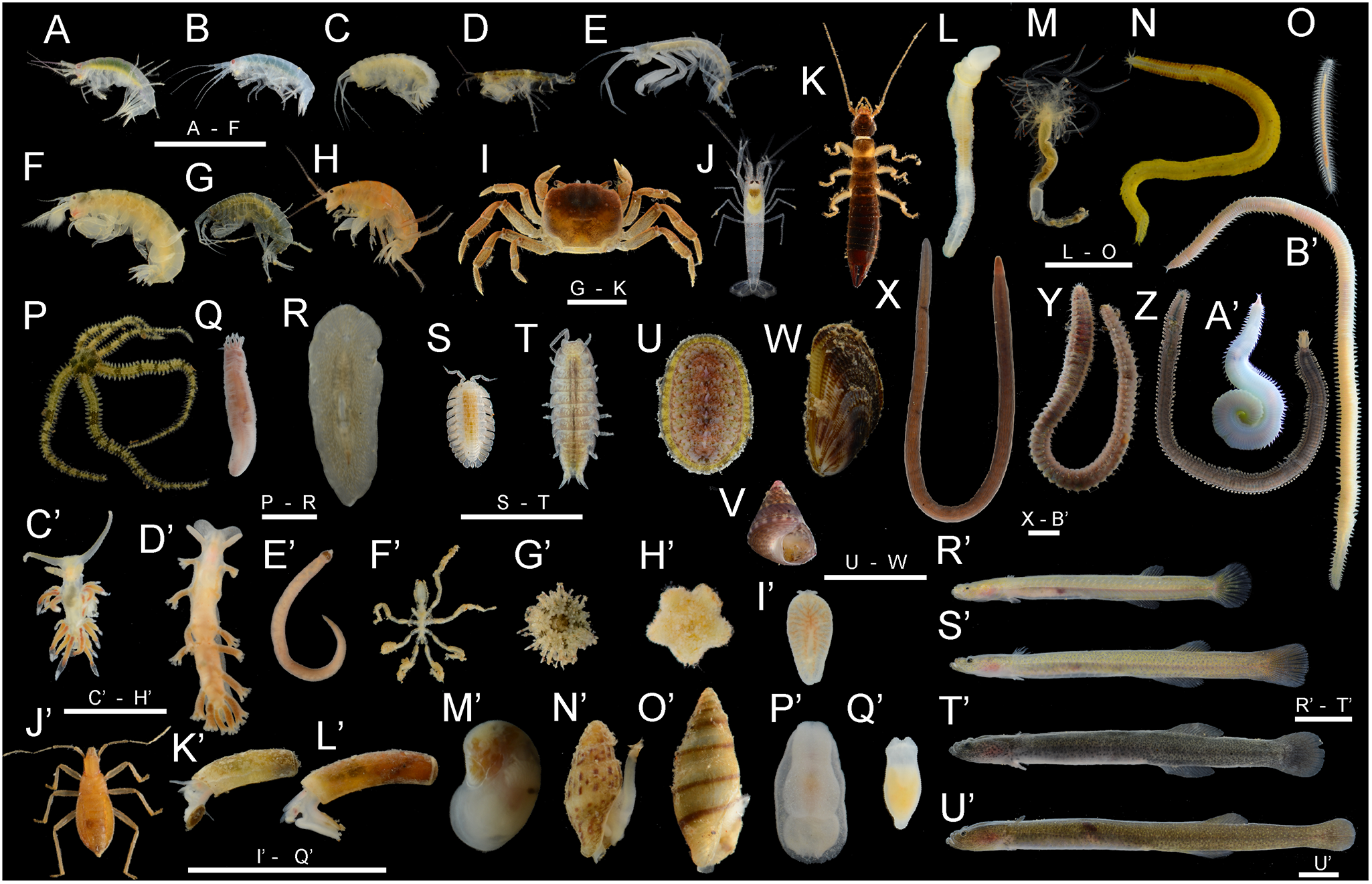

A total of 11965 individuals belonging to 67 species, more than 18 orders, and 9 phyla were collected. The habitus and GenBank accession numbers of the DNA barcodes for most species are shown in Figure 2 and Table S1, respectively. In terms of the number of species, the most diverse phylum was Arthropoda, with 23 species. This was followed by Mollusca (16 species), Annelida (9 species), Echinodermata (6 species), Platyhelminthes and Vertebrata (4 species each), Nemertea (3 species), and Hemichordata (1 species). In terms of the number of individuals, Caecum sp. 1 (6714 individuals) (Figure 2K’), Paramoera (Dentomoera) sp. (Figure 2A) (1061 individuals), Ptilohyale sp. (Figure 2F) (660 individuals), Procerodes sp. (Figure 2P’) (555 individuals), Pyatakovestia gageoensis (Figure 2H) (421 individuals), Ophiactis cf. savignyi (Figure 2P) (347 individuals), Paramoera sp. (Figure 2B) (333 individuals), Aoroides sp. (Figure 2D) (322 individuals), Armadilloniscus aff. albus (Figure 2S) (245 individuals) and Caecum sp. 2 (Figure 2L’) (153 individuals) were dominant, in that order. The species richness of each site ranged from 1.00 to 20.0, Shannon–Weaver diversity index (H’) ranged from 1.00 to 10.2, and Simpson’s diversity (reciprocal: 1/λ) ranged from 1.00 to 7.27. The mean species richness of all stations was 6.8, the overall and mean Shannon-Weaver diversity index was 7.0 and 4.0, respectively, and the overall and mean Simpson’s diversity index was 3.0 and 3.1, respectively.

Figure 2. Habitus of most macrobenthic species occur in the present study from the pebble beach in Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture, central Japan. A: Paramoera (Dentomoera) sp., B: Paramoera sp., C: Gammarella sp., D: Aoroides sp., E: Grandidierella sp., F: Ptilohyale sp., G: Melita sp., H: Pyatakovestia gageoensis, I: Cyclograpsus pumilio, J: Metabetaeus lapillicola, K: Anisolabis sp., L: Enteropneusta sp., M: Polycirrus onibi, N: Nereiphylla sp., O: Sinohesione sp., P: Ophiactis cf. savignyi, Q: Taeniogyrus aff. mijim, R: Notocomplana sp., S: Armadilloniscus aff. albus, T: Quelpartoniscus aff. toyamaensis, U: Ischnochiton sp., V: Cantharidus japonicus, W: Brachidontes mutabilis, X: Lineidae sp., Y: Pareurythoe japonica, Z: Pisione cf. crassa, A’: Hemipodia yenourensis, B’: Goniadides sp., C’: Pruvotfolia sp., D’: Embletonia aff. gracilis, E’: Tetrastemma sp., F’: Ammothella sp., G’: Fibulariidae sp., H’: Aquilonastra sp., I’: Procerodes sp., J’: Nagisavelia cf. hikarui, K’: Caecum sp. 1, L’: Caecum sp. 2, M’: Neritilia cf. mimotoi, N’: Zafra sp. 1 sensu Tsuchiya, Reference Tsuchiya and Okutani2017, O’: Zafra sp., P’: Spiniphiline sp., Q’: Platyhelminthes sp., R’: Luciogobius sp. 11 sensu Shibukawa et al., Reference Shibukawa, Aizawa, Suzuki, Kanagawa and Muto2019, S’: Luciogobius sp. 8 sensu Shibukawa et al., Reference Shibukawa, Aizawa, Suzuki, Kanagawa and Muto2019, T’: Luciogobius cf. grandis, U’: Luciogobius sp. 7 sensu Shibukawa et al., Reference Shibukawa, Aizawa, Suzuki, Kanagawa and Muto2019. Scale bars indicate 5 mm.

Characteristics of interstitial macrobenthic communities

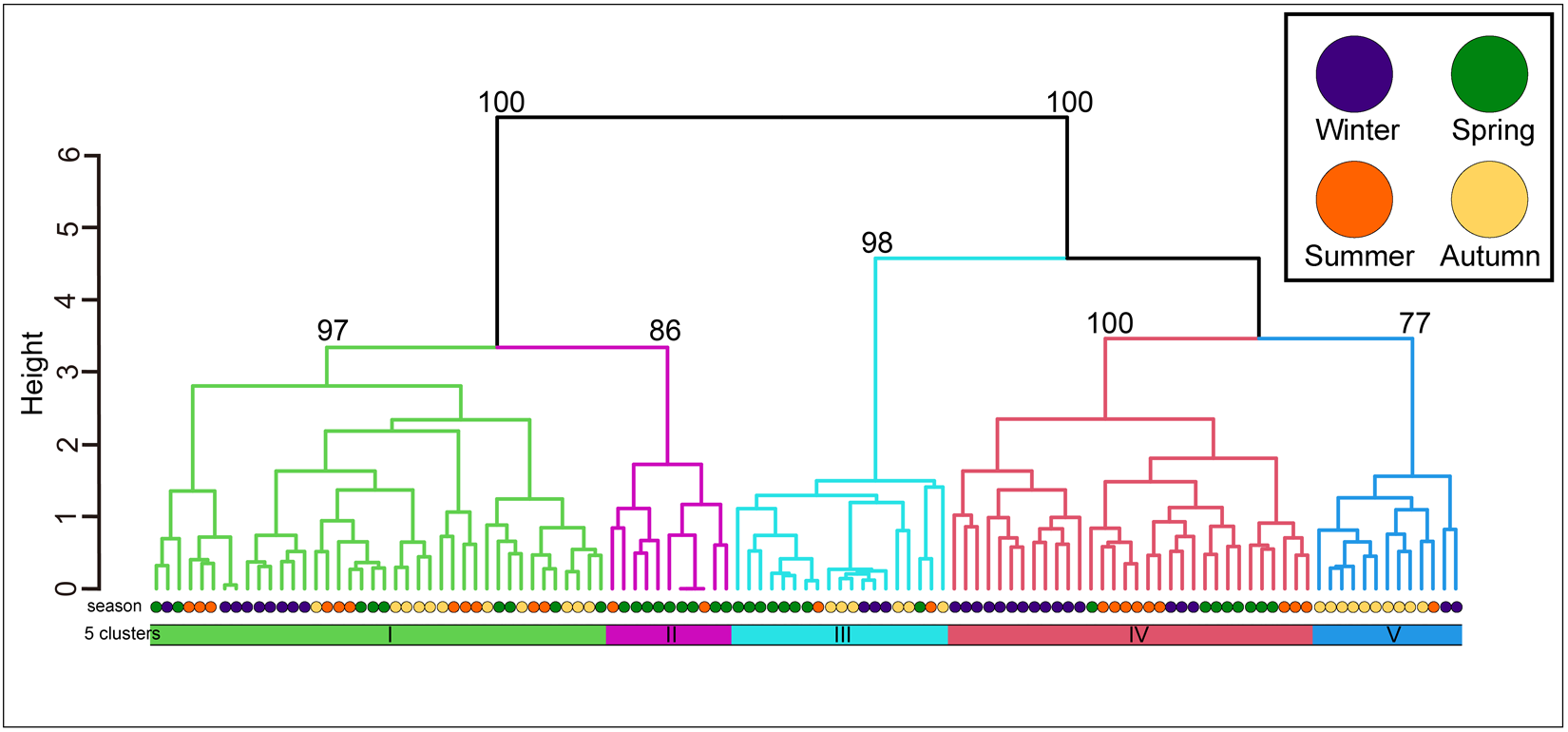

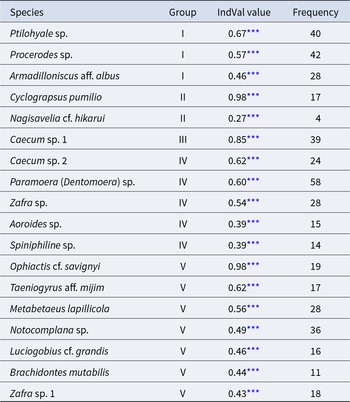

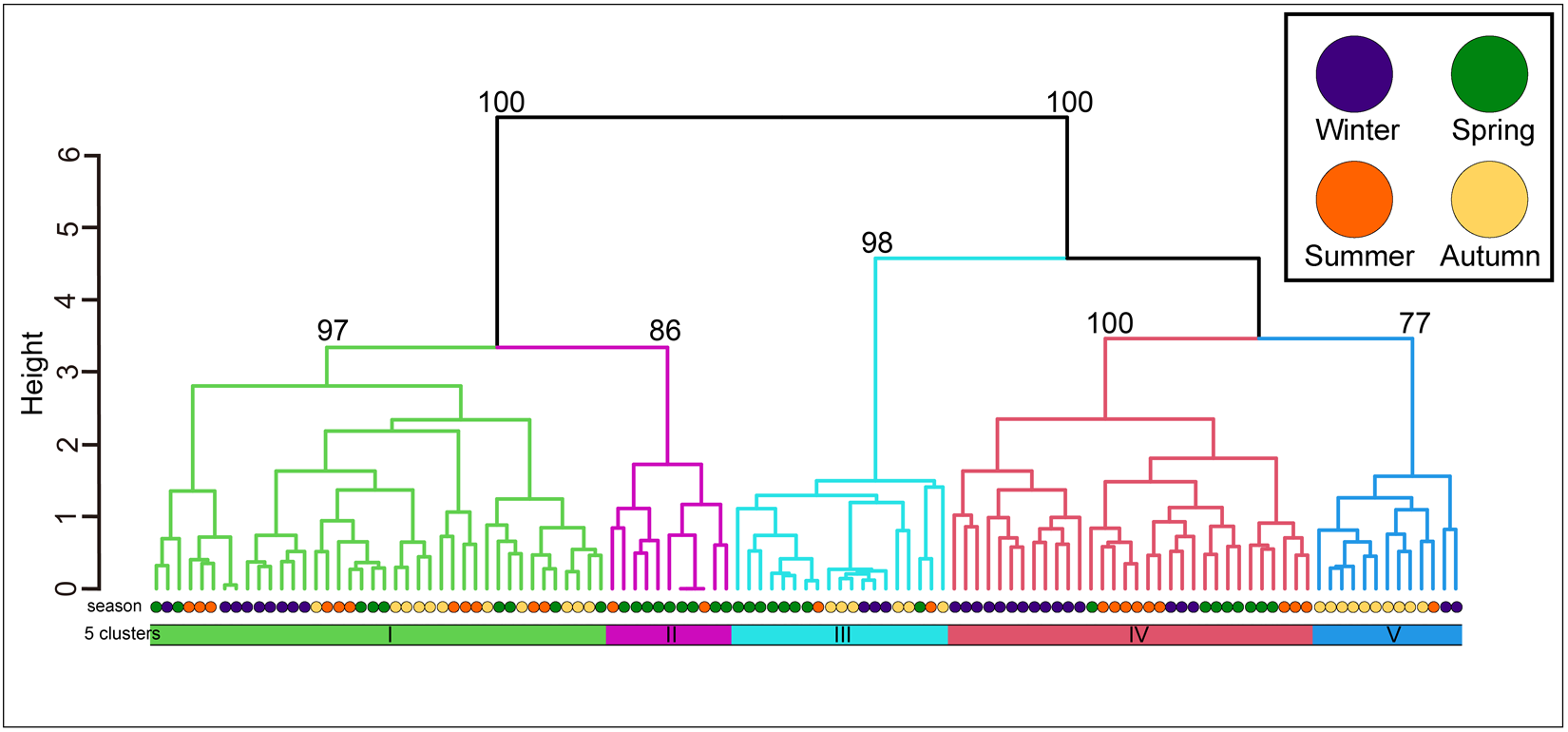

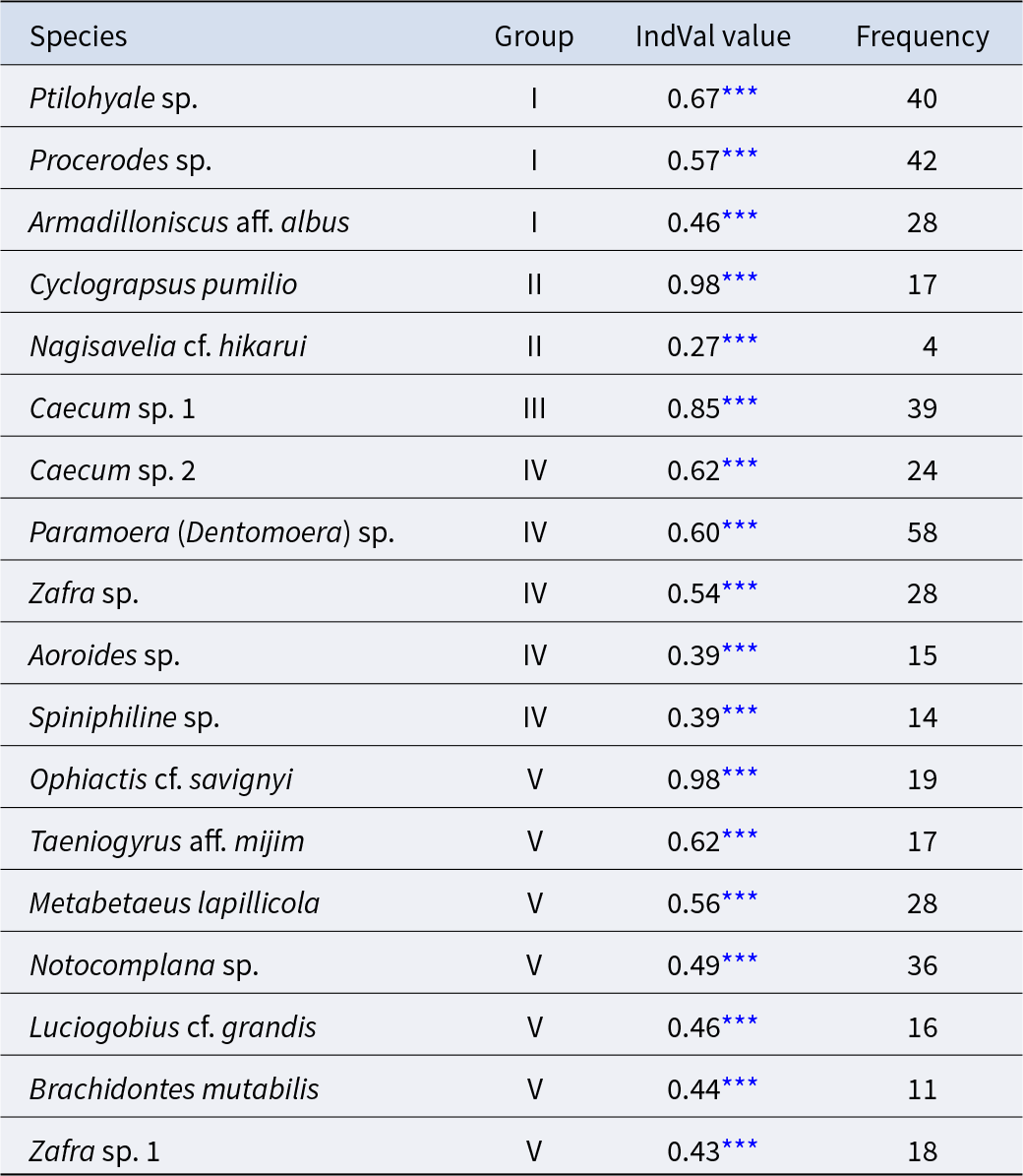

The community was classified into five groups (Figure 3; groups I–V) (cut level of similarity: 3.2) according to the matrix correlation (Fig. S1). These groups were supported with a high, approximately unbiased probability (>77%) using the bootstrap method (Figure 3). Indicator species were selected for each group (Table 1): Ptilohyale sp., Procerodes sp., and Armadilloniscus aff. albus (group I); Cyclograpsus pumilio and Nagisavelia cf. hikarui (group II); Caecum sp. 1 (group III); Caecum sp. 2, Paramoera (Dentomoera) sp., Zafra sp., Aoroides sp., and Spiniphiline sp. (group IV); and Taeniogyrus aff. mijim, Ophiactis cf. savignyi, Metabetaeus lapillicola, Notocomplana sp., Luciogobius cf. grandis, Brachidontes mutabilis and Zafra sp. 1 (group V).

Figure 3. The dendrogram resulting from the Ward clustering of the macrobenthic species composition of each station. The number above each node indicates its multiscale bootstrap value as a percentage.

Table 1. The indicator species estimated for each community group

*** :permutation test with 10000 repetitions p < 1.00 × 10−3.

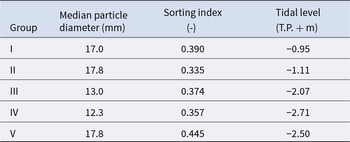

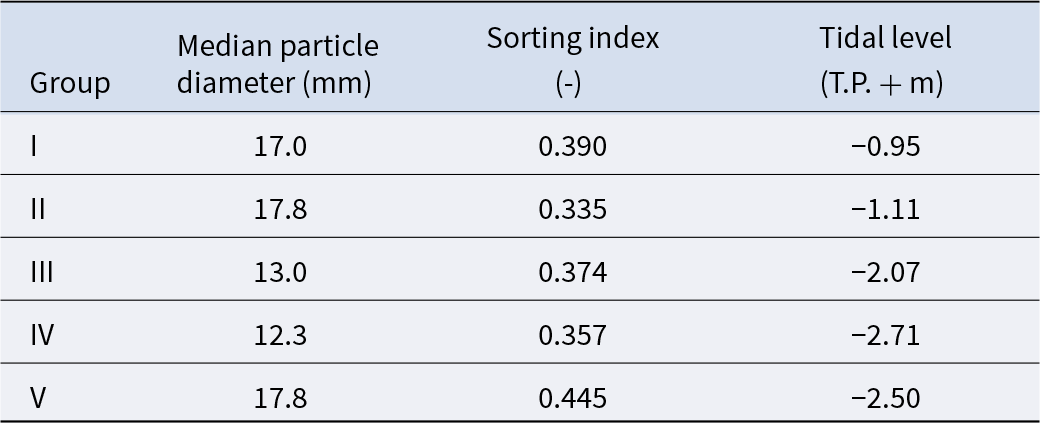

The mean values of species composition (based on the number of individuals) and abiotic environmental factors in the five groups obtained from clustering are shown in Table S3 and Table 2, respectively. The median particle diameter at each station varied from 7.85 to 30.16 mm (standard deviation: 4.41 × 10−3). Group IV exhibited the smallest average median particle diameter (12.3 mm), whereas groups II and V had the largest (17.8 mm). Group II exhibited the lowest average sorting index (0.335), whereas group V demonstrated the highest value (0.445). With respect to average tidal level, group I exhibited the greatest height (−0.95 T.P. + m), whereas group IV demonstrated the lowest height (−2.71 T.P. + m). Significant discrepancies were observed in the mean values of both the median particle diameter and tidal level (Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance: p < 1.00 × 10−3). Additionally, the mean tidal levels of groups I and II were significantly higher than those of groups III, IV, and V (Brunner–Munzel test: p < 1.00 × 10−3), and those of groups III, IV were also higher than V (Brunner–Munzel test: p < 1.00 × 10−3). The median sediment diameters of groups I, II, and V were significantly larger than those of groups III and IV (Brunner–Munzel test: p < 1.00 × 10−3).

Table 2. The average value of abiotic environmental factors for each community group

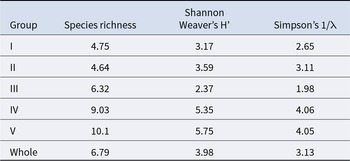

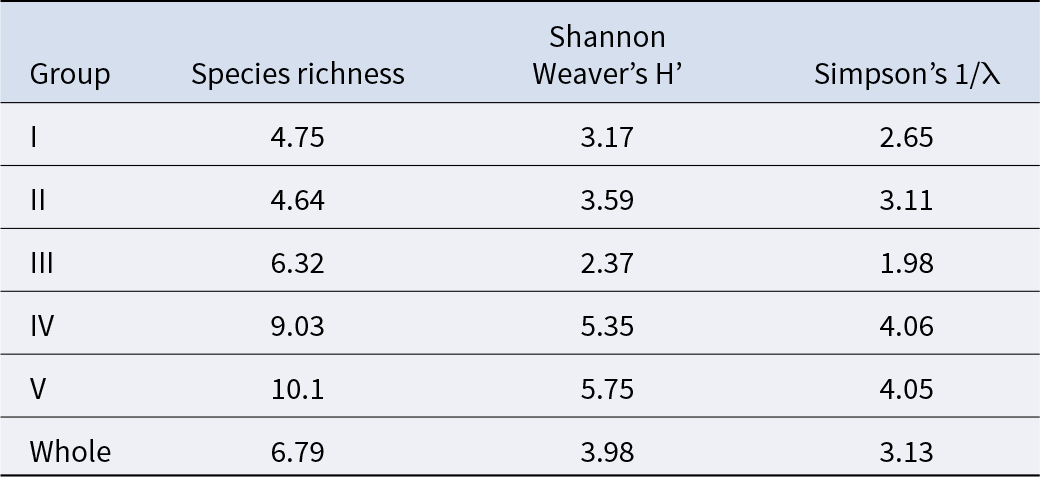

The average species richness per group, Shannon–Weaver diversity index, and Simpson’s diversity index are shown in Table 3. Group I exhibited the smallest numbers in all average indices, whereas group V demonstrated the largest average species richness and Shannon–Weaver diversity index. Group IV had the highest average Simpson’s diversity index. Significant differences were detected among the groups for each index (Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance, p < 1.00 × 10−3). Both species richness and the Shannon–Weaver diversity index of groups I and II (upper intertidal) were significantly lower than those of groups III, IV, and V (Brunner–Munzel test, p < 1.00 × 10−3). The Simpson’s diversity index values of groups I and II (upper intertidal) were significantly smaller than those of groups IV and V (Brunner–Munzel test: p < 1.00 × 10−3). All indices of groups III and IV were significantly lower than those of group V (Brunner–Munzel test: p < 1.00 × 10−3).

Table 3. The average species diversity indices for each community group

Relationship between communities and abiotic environmental factors

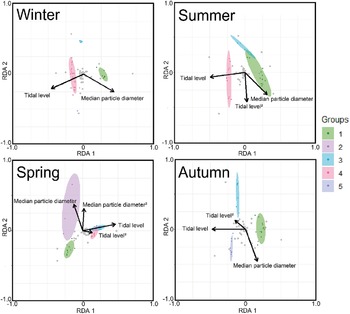

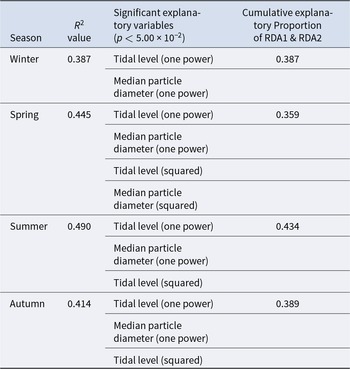

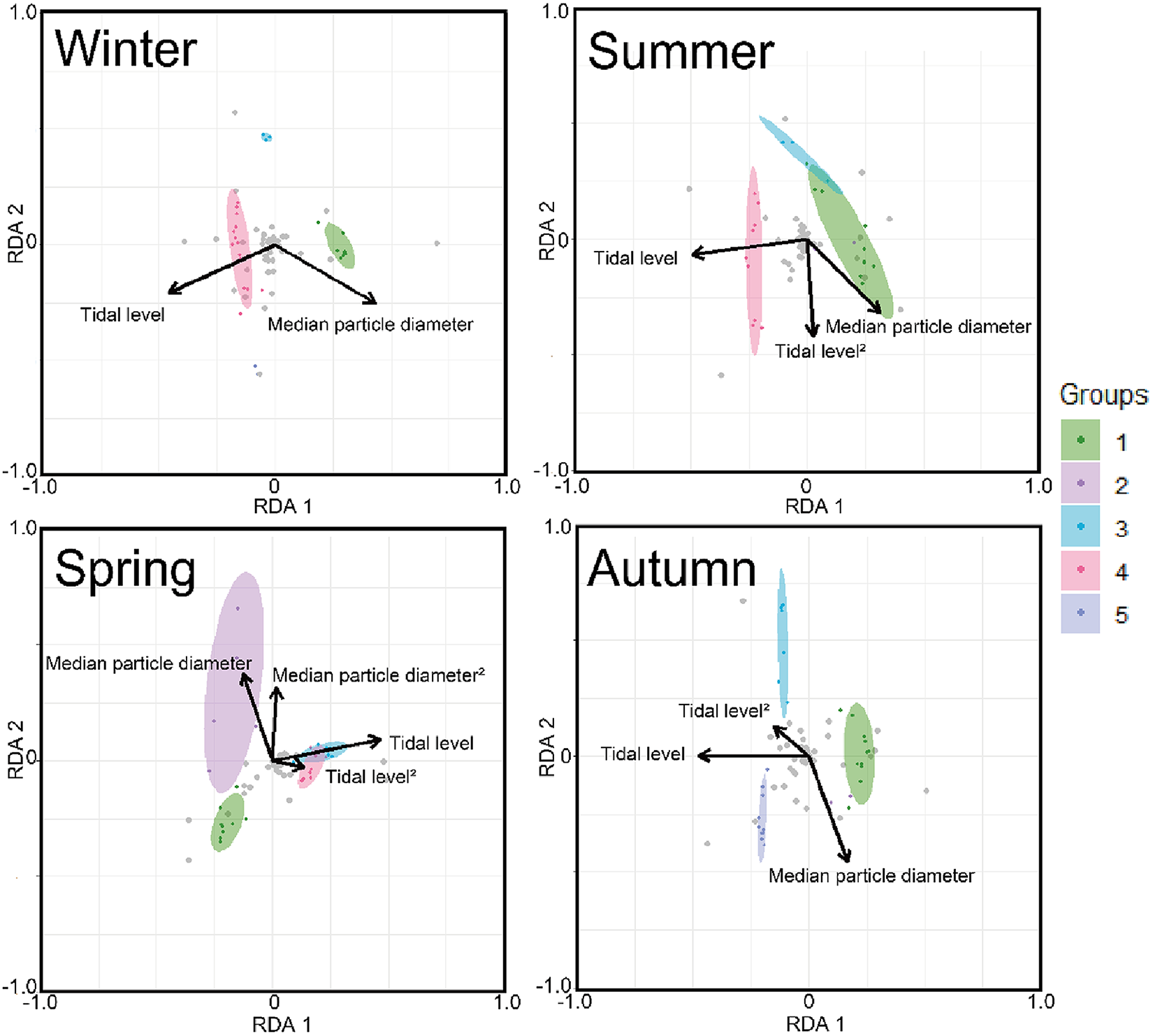

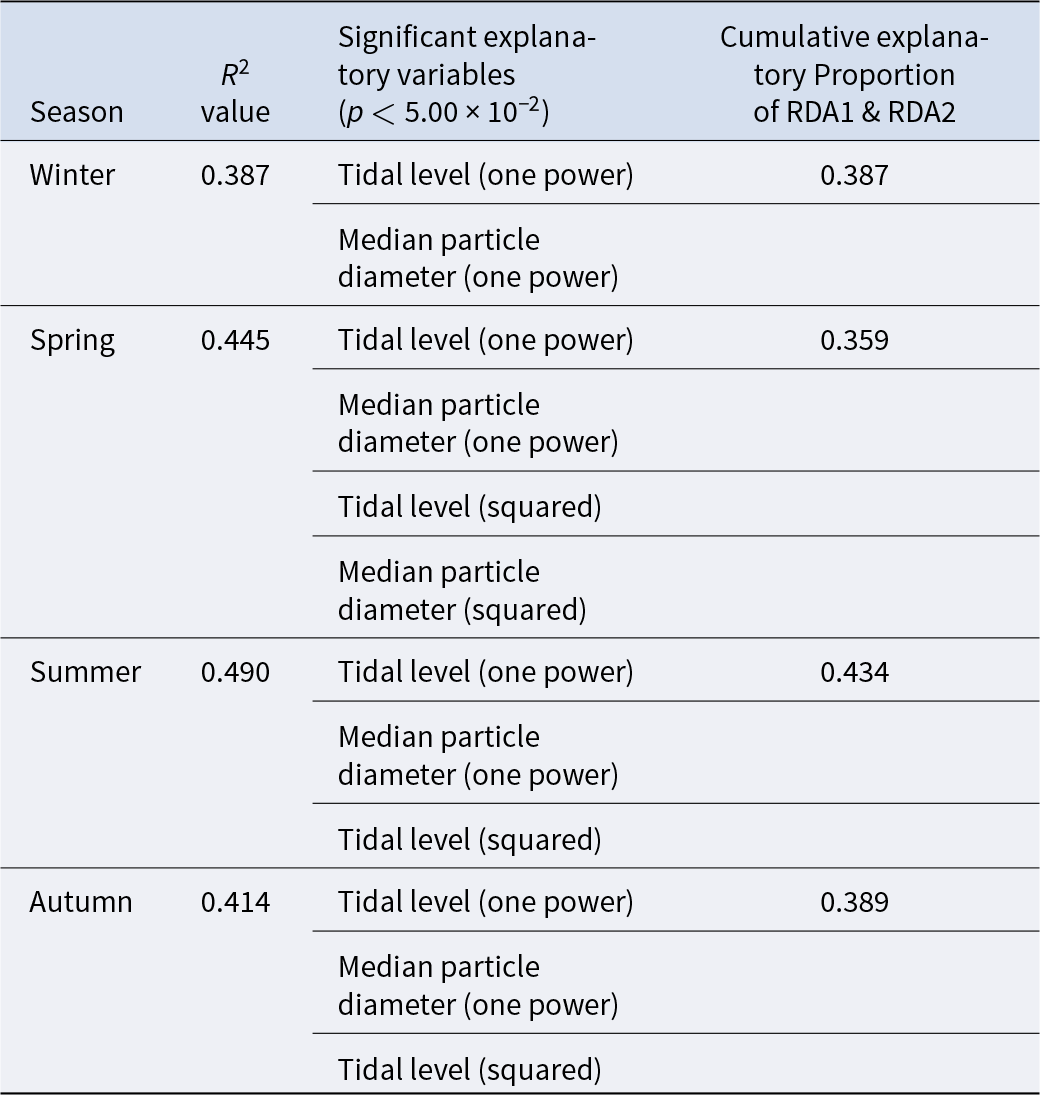

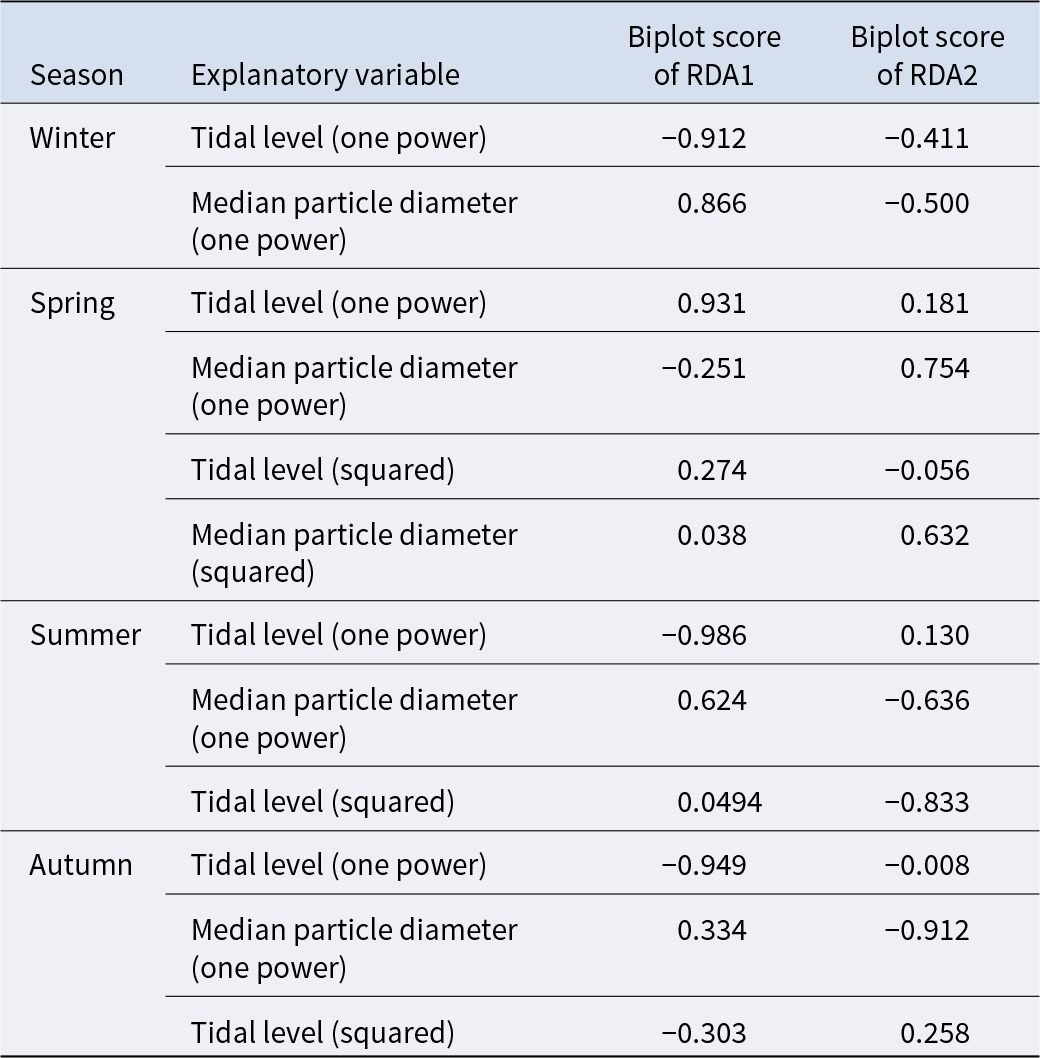

The triplot and summary resulting from the RDA for each season are shown in Figure 4 and Table 4. For the explanatory variables of the functions, the median particle diameter, tidal level, and squared tidal level were selected (the latter variable was not chosen in winter). The multicollinearity among explanatory variables was not detected in each season (VIF < 10.0). The coefficient of determination of the multiple regression function for each season was 0.387–0.490. Axes 1 and 2 explained 35.9–43.4% of the variance in the total species composition data for each season. The correlation coefficients between each axis and the environmental factors are shown in Table 5. The results of 1000 permutation tests for the multiple regression function used for ordination, axes 1 and 2, confirmed their significance in each season (p < 5.00 × 10−2).

Figure 4. The triplots of RDA for each season. The ellipse indicates its belonging community group by clustering with 80% confidence. Grey plots indicate score plots of each species. Arrows indicate strength of correlation between each environmental factor (absolute value) and communities.

Table 4. Summaries of RDA for each season. R 2 values and explanatory variables were obtained from multiple regression functions used in the ordination

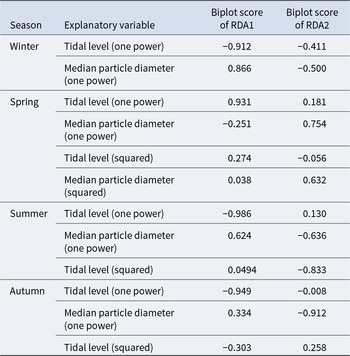

Table 5. Biplot scores of explanatory variables from the multiple regression function for each RDA axis, indicating their correlations with the respective axes

In winter (Figure 4), groups I, III, and IV were predominantly observed, with no overlapping ellipses in each group. Group I was located in the direction of higher tidal levels and larger median particle diameter, group III in the direction of moderate tidal levels and smaller median particle diameter, and group IV in the direction of lower tidal levels and smaller median particle diameter. In spring (Figure 4), groups I and II were located in the direction of higher tidal levels, whereas groups III and IV were located in the direction of lower tidal levels. The ellipses of group II extended in the direction of larger median particle diameter when compared to those of group I. However, group II ellipses demonstrated greater variability and exhibited proximity to those of group I. The ellipses of groups III and IV exhibited greater overlap. The results for the summer season (Figure 4) were similar to those for the winter season. However, the arrangement of Group III exhibited a strong correlation with the squared tidal level. In autumn (Figure 4), a marked decline was observed in the abundance of group IV, whereas group V exhibited a notable increase in frequency. Groups I, III, and V demonstrated higher tidal levels, in ascending order. Group III was positioned in the direction of the smaller median particle diameter when compared to Group V.

Discussion

Interstitial macrobenthic fauna in the pebble beach

To date, few studies have been conducted on comprehensive macrobenthic communities on pebble beaches. Globally, such studies are limited [i.e. Robbins and Griffiths (Reference Robbins and Griffiths2023), which dealt with pebble beaches in South Africa; Jazdzewski et al. (Reference Jazdzewski, De Broyer, Pudlarz, Zielinski, W.e and Clarke2002), which dealt with pebble beaches on King George Island on the Antarctic Ocean coast; and Ronowicz (Reference Ronowicz2005), which dealt with pebble beaches on Spitsbergen Island (Norway) on the Arctic Ocean coast]. In Japan, although several studies have examined specific taxonomic groups [i.e. earthworm gobies (Luciogobius genus complex) (Yamada et al. Reference Yamada, Sugiyama, Tamaki, Kawakita and Kato2009), smooth chore crabs (the genus Cyclograpsus) (Maenosono Reference Maenosono2022), ostracods (the genus Anchistrocheles) (Ito and Tsukagoshi Reference Ito and Tsukagoshi2022), rove beetles (the genus Halorhadinus) (Ono and Maruyama Reference Ono and Maruyama2014) and gastropod molluscs in supratidal zone (Wada et al. Reference Wada, Kawabuchi and Tamego2015)], few have addressed the subject of comprehensive macrobenthic fauna. Therefore, this is the first study to reveal the comprehensive macrobenthic fauna on pebble beaches in the northwest Pacific and temperate areas.

We found polychaetes, genus Sinohesione (Figure 2O), and genus Goniadides (Figure 2B’), and beach hopper species, Pyatakovestia gageoensis (Figure 2H) for the first time from Japan, which has not been recorded in the northwest Pacific or in Japan (Böggemann Reference Böggemann2005; Morino and Miyamoto Reference Morino and Miyamoto2015; Westheide et al. Reference Westheide, Purschke and Mangerich1994). Furthermore, many possible undescribed species also occur in the present study [e.g. the flatworm, Notocomplana sp. (Figure 2R), the chiton, Ischnochiton sp. (Figure 2U), micromolluscs, Caecum spp. (Figure 2K’, L’), the earthworm gobies, Luciogobius spp. (Figure 2R’–U’), the polychaetes, Goniadides sp. (Figure 2B’) and Sinohesione sp. (Figure 2O), the woodlices, Armadilloniscus aff. albus (Figure 2S) and Quelpartoniscus aff. toyamaensis (Figure 2T), the amphipods, Aoroides sp. (Figure 2D), Gammarella sp. (Figure 2C), Grandidierella sp. (Figure 2E), Melita sp. (Figure 2G), Paramoera spp. (Figure 2A, B), and Ptilohyale sp. (Figure 2F) (Yamashita et al., in preparation)]. These sizable numbers of unrecorded and undescribed species are interesting because the coastal fauna of the Japanese mainland has generally been well-investigated (e.g. Nishimura Reference Nishimura1992, Reference Nishimura1995; Japanese Association of Benthology 2012; Motokawa and Kajihara Reference Motokawa and Kajihara2017; Biodiversity Center of Japan, Nature Conservation Bureau, Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan, Biodiversity Center of Japan, Ministry of the Environment 2025). Thus, species diversity in the environment remains poorly understood and needs to be investigated by multidisciplinary taxonomists.

In addition to these unrecorded/undescribed species, we identified several interstitial endemics. The smooth shore crab Cyclograpsus pumilio (Figure 2I), pebble shore shrimp Metabetaeus lapillicola (Figure 2J), earthworm gobies Luciogobius spp. (Figure 2R’–U’), coastal semiaquatic bug Nagisavelia cf. hikarui (Figure 2J’), the amphipod Pyatakovestia gageoensis (Figure 2H), and woodlices Armadilloniscus aff. albus (Figure 2S) and Quelpartoniscus aff. toyamaensis (Figure 2T) (the last two species are morphologically and genetically similar) are presently known only from the interstitials of pebble beaches (Nunomura Reference Nunomura1984, Reference Nunomura2005; Yamada et al. Reference Yamada, Sugiyama, Tamaki, Kawakita and Kato2009; Kim and Min Reference Kim and Min2013; Nakaoka and Wada Reference Nakaoka and Wada2017; Shibukawa et al., Reference Shibukawa, Aizawa, Suzuki, Kanagawa and Muto2019; Watanabe et al. Reference Watanabe, Nakajima and Hayashi2023; Yamashita et al. Reference Yamashita, Komai and Kon2023). Moreover, the polychaetes Pareurythoe japonica (Figure 2Y) and Hemipodia yenourensis (Figure 2A’), and the headshield slug, Spiniphiline sp., the amphipod Paramoera (Dentomoera) sp. (Figure 2A), and the trepang Taeniogyrus aff. mijim (Figure 2Q) (the last two species are morphologically and/or genetically similar) were known to be mainly preferred sand-pebble mixed beaches or pebble beaches (Kashio and Fukuda Reference Kashio and Fukuda2025; Labay Reference Labay2023; Nishimura Reference Nishimura1992, Reference Nishimura1995; Yamana et al. Reference Yamana, Tanaka and Nakachi2017). However, only 11 species have been found in other coastal environments (Nishimura Reference Nishimura1992, Reference Nishimura1995). Most of them, however, exhibited quite low frequencies and/or abundances (Table S3), with even the frequently found species typically being obtained only as juveniles [e.g. some gastropods (Zafra sp. sensu Tsuchiya Reference Tsuchiya and Okutani2017, Cantharidus japonicus, Monodonta neritoides and Brachidontes mutabilis) were found almost entirely less than 10 mm SL, whereas their adults were more than 15–20 mm SL (Sasaki Reference Sasaki and Okutani2017a, Reference Sasaki and Okutani2017b; Tsuchiya Reference Tsuchiya and Okutani2017)]. Therefore, their occurrence may be attributed to abortive migration, with the pebble beaches representing potentially suboptimal environments for survival. Considering it with (i) the substantial number of undescribed species and (ii) species known to be biased from the pebble beach as previously mentioned, the macrobenthic community inhabiting pebble beaches is predominantly composed of species specific to this environment, exhibiting minimal faunal resemblance to other coastal ecosystems. Moreover, an earlier study in another biogeographic area indicated that the macrobenthic fauna of pebble beaches exhibited minimal similarity to different coastal environments (Robbins et al. Reference Robbins, Griffiths and Nefdt2022). This suggests that the pebble beach environment should not treat only one type of sandy beach or rocky beach (sediments consisting of larger particles), but rather as an independent environment that is discontinuous with them.

The macrobenthic community structure was also highly differentiated from that of other biogeographical areas. Indeed, total species richness, average species richness, average H’ index, and average 1/λ were 12, 5.3, 2.4, and 1.9, respectively, in pebble beaches of south Africa (7 stations) (Robbins and Griffiths Reference Robbins and Griffiths2023); total species richness, H’ index, and 1/λ were 7, 5.8, and 4.6, respectively, in the pebble beach (named as ‘Stone beach’ in the study) of Arctic Ocean coast (1 station) (Ronowicz Reference Ronowicz2005); and total species richness, H’ index, and 1/λ were 20, 3.6, and 2.4, respectively, in the pebble beach (however, it is possibly mixed beach with the cobble beach) of Antarctic Ocean coast (1 station) (Jazdzewski et al. Reference Jazdzewski, De Broyer, Pudlarz, Zielinski, W.e and Clarke2002). The most of above values were lower than that of in the present study (Tables 3, S3). Furthermore, in these studies, few common species or genera of macrobenthos were reported in the present study. These diversity differences are probably not due to differences in sampling methods, given that our sampling effort per station was rather low [8 L × 8 tidal level × 8 times in Robbins and Griffiths (Reference Robbins and Griffiths2023), 4.5 L × 3 tidal level × 4–5 times in Ronowicz (Reference Ronowicz2005) and 150 L × 24 times in Jazdzewski et al (Reference Jazdzewski, De Broyer, Pudlarz, Zielinski, W.e and Clarke2002)]. Furthermore, our macrobenthos fauna did not cover all the pebble-beach-preferring taxa known from other beaches in the Japanese archipelago. For example, Ono and Maruyama (Reference Ono and Maruyama2014) documented the high species richness of rove beetles, genus Halorhadinus, from one pebble beach in Oita Prefecture, southern Japan, and Ito and Tsukagoshi (Reference Ito and Tsukagoshi2022) reported several ostracods from one pebble beach in Shizuoka Prefecture, central Japan, and Kondo and Kato (Reference Kondo and Kato2022) reported the prey benthic communities (including macrobenthos) of earthworm gobies (genus Luciogobius); however, almost all of them were not observed in the present study (Figure 2). These species inconsistencies could be due to abiotic environmental factors; specifically, at least the openness of the coast [open to the ocean in the present study vs. more closed or facing the inner bay in Ono and Maruyama (Reference Ono and Maruyama2014) and Ito and Tsukagoshi (Reference Ito and Tsukagoshi2022)], the particle size of the sediment [consisting mainly of pebble only, with little sand content vs. more or less mixed sand in Ono and Maruyama (Reference Ono and Maruyama2014) and Ito and Tsukagoshi (Reference Ito and Tsukagoshi2022)] and depth of deposition [at least 30 cm vertically vs. thinly deposited on bedrock in Kondo and Kato (Reference Kondo and Kato2022)] differed. These suggest that (i) current ‘pebble beach’ (the beach, whose sediment consists of 4–64 mm particles) is likely able to be categorized into multiple environments based on the beach unit macrobenthic fauna and environmental factors and (ii) species composition and its diversity may vary significantly depending on the biogeographic zone as well. It is necessary to verify and typify the environments included in the pebble beach environment based on biogeographical and environmental factors, as well as species composition.

The relationship between community structure and abiotic environmental factors

It is generally accepted that a single community is widely distributed on pebble beaches (Raffaelli and Hawkins Reference Raffaelli and Hawkins1999). However, the present study revealed that the presence of several community groups on one pebble beach by clustering (Figure 3) and environmental factors (i.e. median particle diameter and tidal level) of microhabitats significantly controlled the macrobenthic species composition within it by RDA (Figure 4; Table 4). These results strongly support the isolation of macrobenthos by zonal distribution and sediment particle size, even on pebbled beaches. Except for winter, the square tidal level was identified as a significant explanatory variable of the RDA (Figure 4B–D; Table 4), indicating that certain community groups (species) exhibited a unimodal response to this factor, that is, a preference for a specific tidal level. Moreover, the vectors of these factors intersected in a near-orthogonal manner (Figure 4; Table 5), indicating that they independently controlled the species composition. Conversely, the R2 values of the multiple regression functions utilized for the RDA were comparatively low, ranging from 0.39 to 0.49 (Table 4). Additionally, most groups exhibited an aggregation of stations within the groups; however, a limited number of stations were positioned considerably distant from each other (Figure 4). These results suggest that environmental factors are likely to be ‘moderate’ and do not strictly regulate community structure. This might be due to the adaptation of macrobenthos to pebble beaches with high disturbances to sediments (e.g. Morohashi et al. Reference Morohashi, Okamoto, Ishino, Uda, Ishikawa and Sannami2018). Macrobenthos within the environment are also regularly transferred to sediments. Consequently, if macrobenthos occupy a highly specific and stringent ecological niche within the environment, a considerable cost is incurred for their maintenance (recovery from disturbance). Conversely, interspecific differentiation of ecological niches reduces interspecific competition and allows stable sympatric multispecies coexistence (Chesson Reference Chesson2000). Therefore, in pebble beaches, macrobenthos are likely to exhibit a ‘moderate specific’ microhabitat in the result of optimization of these trade-offs. In the present study, seasonal occurrence trends differed between groups occupying analogous environments. For example, in the lower intertidal groups (groups IV and V), group IV occurred widely outside autumn, whereas group V appeared during autumn. Similarly, group I was found to occur year-round, whereas group II was generally biased to occur in spring for the upper intertidal groups (groups I and II) (Figure 3). This suggests that species turnover is an important factor in maintaining community diversity.

Conclusion and perspective

This study reveals the presence of a diverse and unique assemblage of macrobenthic species and communities within a single pebble beach in Japan. Abiotic environmental characteristics appeared to exert moderate control.

Pebble beaches are rapidly destroyed and lose their size and number owing to anthropogenic modification (Wada Reference Wada2022). In particular, at the present study site, the supply of sediment to the site was significantly diminished by harbour work. Consequently, there has been a decline in the amount of sediment deposited owing to beach erosion, with the impact being more pronounced on the backshore (Uda et al. Reference Uda, Ishikawa, Sannami, Ishino, Suzuki and Okamoto2017). The present study demonstrated a clear bifurcation of community groups according to tidal level. Communities from upper intertidal areas (groups I and II) are likely to lose their habitats if backshore erosion continues at the current rate. Furthermore, the median sediment particle diameters among stations contributed to the determination of local species composition, although the dispersion of this factor among stations was very small (Table 2). Additionally, the sorting index for each station was generally small (Table 2). These results strongly indicate that the persistence of certain community groups and species is threatened by accidental biases in sediment particle diameter composition if the reduction in sediment mass continues throughout the beach. Thus, to maintain unique and diverse macrobenthos on pebble beaches in the future, it is essential to keep microscopic but diverse pebble sediment deposition intact throughout the intertidal.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315425100829.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the members and graduates of the Laboratory of Benthology at Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology for supporting the survey and to Dr. Kotaro Tsuchiya and Dr. Masato Moteki for their valuable comments on the manuscript. Observations of some specimens were carried out using the facility of the Sugashima Marine Biological Laboratory, Nagoya University.

Author contribution

The first author (RY) was responsible for the field survey and identification of decapods, isopods, insects and pisces, DNA barcoding, and analysing data. He prepared the draft mainly. The second author (RA) was responsible for the identification of the molluscs, with a particular focus on the gastropods. The third author (HS) was responsible for the identification of the molluscs, with a particular focus on the heterobranch sea slugs. The fourth author (SS) was responsible for the identification of the polychaetes. The fifth author (HO) was responsible for the identification of the amphipods. The final author (KK) was responsible for the revision of the draft. The draft was critically reviewed and approved by all authors.

Financial support

This study was supported by the Sasakawa Scientific Research Grant from the Japan Science Society (Grant Number: 2023-4041), JST SPRING (Grant Number: JPMJSP2147), and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number: JP23K23632).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

Data availability statement

The corresponding author can provide the data on request. The specimens (except for protected species released) collected during the study will be deposited in the official museum after the author(s) have completed the necessary taxonomic studies.