Introduction

This paper examines how a representative of a civil society organization (CSO), despite opposition from the government and being part of a minority in the commission preparing the law, managed to significantly influence the genesis of one of Denmark’s most contentious pieces of migration legislation, the Danish Aliens Act of 1983. The paper applies the neo-institutional concept of ‘institutional entrepreneurship’ to examine how an individual actor significantly influenced political decision-making leading to the enactment of the legislation. The paper thereby emphasizes the need for additional focus on the influence of individual actors in the CSO advocacy literature.

In 1977, in response to growing concerns about the legal protection of foreigners in Denmark, the government established a commission to review migration legislation and propose a new Aliens Act.Footnote 1 During its deliberations, the commission divided into two groups, each proposing contrasting versions of the law: one favoring a slightly more restrictive approach and the other advocating for a more liberal stance. The former group composed of seven civil servants, who were aligned with the conservative government. The latter group included the protagonist of the present paper, Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen (HGH), chair of the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), and two other commission members. Despite HGH’s liberal proposal being in minority in the commission and facing government resistance, he, along with the DRC, managed to secure sufficient parliamentary support for their proposal, bypassing the government. Consequently, in 1983, a version almost identical to HGH’s proposal was enacted. This paper elucidates the law preparation process, highlighting how a representative of a CSO achieved disproportionate influence on the enacted legislation. As such, it contributes to the scholarly debate on CSO advocacy by empirically outlining how an individual actor successfully impacted the advocacy conducted by a CSO, thereby influencing policy processes and outcomes.

The analysis is driven by the research question: How can an individual actor, within a civil society organizational context, shape CSO advocacy processes and their outcomes? As I will elaborate below, individual actors has been neglected within the CSO advocacy scholarly field. Consequently, the field likewise lack theoretical tools to examine the role of individuals in CSO advocacy processes. Therefore, this paper aims at developing the CSO advocacy theory by emphasizing the impact of individual actors’ role in policymaking processes. The paper outlines how theoretical notions from the neo-institutional concept of institutional entrepreneurship, which is designed to examine organizational and individual actors in change processes, can provide useful inspiration to study the role of individual actors in CSOs’ advocacy endeavors.

The structure versus agency debate is prominent in CSO advocacy literature, as it is in most scholarly fields that study organizations and change processes. However, while other areas of organizational research have recently shifted toward greater emphasis on the agency of actors in change processes, CSO advocacy literature has largely maintained a predominant focus on structural determinism (Almog-Bar & Schmid, Reference Almog-Bar and Schmid2014; Mosley et al., Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023). Among the structural factors examined, most attention has been devoted to how organizational characteristics determine which organizations engage in advocacy activities (Lu, Reference Lu2018) and how these characteristics influence organizations’ ability to conduct advocacy (Bolleyer & Correa, Reference Bolleyer and Correa2022). Other studies focus on broader societal structures such as funding arrangements (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Hulme and Edwards2015; Hulme & Edwards, Reference Hulme and Edwards1997; Mosley, Reference Mosley2012), policy areas (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Friedman and Hochstetler1998; Gatrell, Reference Gatrell2019; Kagan & Dodge, Reference Kagan and Dodge2023), and cultural variations (Amnå, Reference Amnå2006; Sivenbring & Malmros, Reference Sivenbring and Malmros2023) that shape CSO advocacy processes and outcomes.

In response to the dominant focus on structural determinism, scholars have recently called for a shift in CSO advocacy studies, advocating a move away from structural analyses toward examining the agency of individual actors. This shift entails an emphasis on ‘how advocacy activities are being carried out instead of what types of organizations are performing the activities’ (Mosley et al., Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023, p. 188). Thus, rather than asking which organizations perform advocacy and where they do it, the questions should focus on what the organizations are trying to achieve, how they carry it out and why they are involved (Mosley et al., Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023, p. 190). Recently a few studies have had this ambition by shedding light on organizations’ agency and strategies in ‘Hybrid Regimes’ (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Elías and Hernández2024) and ‘constrained settings’ (Van Wessel, Reference Van Wessel, Biekart, Kontinen and Millstein2023). While these studies are part of the increased focus on actors’ agency, they vary in two distinct ways compared to the present paper; they examine different contextual settings and primarily examine the organizational level. The ambition of this paper is to contribute to this scholarly shift by supplementing it with a study of the agency of individual actors in CSO advocacy.

As mentioned, such complementary focus is needed, as the literature emphasizing agency in CSO advocacy thus far have focused on the organizational level. When reading through the literature reviews of studies examining CSO advocacy, one will notice a complete absence of attention to individual actors and their impact on advocacy processes in the field (Almog-Bar & Schmid, Reference Almog-Bar and Schmid2014; Bolleyer & Correa, Reference Bolleyer and Correa2022; Lu, Reference Lu2018). Even in literature that specifically examines the agency of CSOs in advocacy processes, the role of individual actors is often overlooked (Mosley et al., Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023).

Neglecting a phenomenon in a scholarly field often stems from its perceived lack of importance. However, other scholarly fields studying similar phenomena, particularly the neo-institutional field, have long recognized the relevance of studying individual actors in change processes (Hardy & Maguire, Reference Hardy, Maguire, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017). The next section outlines why the neo-institutional framework is a relevant field to get inspiration from, when studying CSO advocacy.

Institutional Entrepreneurship as a Source of Inspiration

Theoretical concepts within the neo-institutional theoretical framework are a particularly valuable source of inspiration for the CSO advocacy literature, due to its similar focus on organizations’ role in change processes within a given structural context. Additionally, the neo-institutional scholarly field has engaged in a similar debate on structure versus agency, as advocated by Mosley et al. (Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023). Underlining its relevance, neo-institutional concepts have been used tremendously in the CSO advocacy field (e.g., Arvidson et al., Reference Arvidson, Johansson and Scaramuzzino2018; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Moder, Neumayr and Vandor2020). However, in these studies, the theoretical concepts have primarily been used to depict the organizational contexts. The aspects of actors’ agency emphasized in neo-institutional literature have yet to be explored using neo-institutional concepts.

The concept of institutional entrepreneurship is particularly relevant because, although it was originally developed to examine the impact of both organizational and individual actors, it has primarily been used to study organizational actors. In the following, I outline the development of neo-institutional theory to position the concept of institutional entrepreneurship within the broader theoretical framework. This approach underscores the relevance of adopting the concept, as there are notable parallels between the evolution of the CSO advocacy field and neo-institutional theory.

Originally, neo-institutional literature focused on how institutions shape organizational behavior (Lawrence & Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006). Institutions are norms and rules that are taken for granted within specific contexts. Using a sports metaphor, institutions encompass both formal and informal rules of a game. Formal rules are explicitly written that are enforced by referees; while, informal rules include aspects like sportsmanship and unwritten codes of conduct that athletes must navigate too. Using this metaphor, actors within an institutional context are akin to players who maneuver within the boundaries of both formal and informal rules to enhance their own position (North, Reference North1990). Similar to the predominant trend in CSO advocacy studies, early neo-institutional theorists highlighted how structural factors shaped organizational actions within specific institutional contexts (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Meyer & Rowan, Reference Meyer and Rowan1977). However, the field struggled to explain institutional change over time. To address this issue, the scientific agenda shifted focus from structural determinism toward actors’ agency in institutional change processes (DiMaggio, Reference DiMaggio1988; DiMaggio & Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1991; Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991). As such the theoretical field have went through some of the changes which Mosley et al. (Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023) argue is needed within the CSO advocacy literature.

With the aim of reintroducing actors’ agency into discussions of institutional change, scholars developed the theoretical concepts, institutional entrepreneurship (DiMaggio, Reference DiMaggio1988; Garud et al., Reference Garud, Hardy and Maguire2007) and institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006). These concepts provided insights into how actors could maneuver within the formal and informal rules to their advantage (Garud et al., Reference Garud, Hardy and Maguire2007; Hardy & Maguire, Reference Hardy, Maguire, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017). The concept of institutional entrepreneurship offers theoretical frameworks to analyze actors who “create new or transform existing institutions” (DiMaggio, Reference DiMaggio1988; Garud et al., Reference Garud, Hardy and Maguire2007; Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Hardy and Lawrence2004); while, institutional work examines ‘purposive actions of individuals and organizations aimed at creating, maintaining, and disrupting institutions’ (Lawrence & Suddaby, Reference Lawrence, Suddaby, Clegg, Hardy, Lawrence and Nord2006, p. 215). The aspect, which is particularly relevant to this study, is that despite emphasizing both organizational and individual agency (DiMaggio, Reference DiMaggio1988; Garud et al., Reference Garud, Hardy and Maguire2007) the concepts faced criticism for neglecting the significance of individual actors (Battilana, Reference Battilana2006). Consequently, there has been a push within the field to incorporate notions that depict the agency of individual actors on institutional change processes (Battilana et al., Reference Battilana, Leca and Boxenbaum2009; Boxenbaum & Battilana, Reference Boxenbaum and Battilana2005). Thus, the same criticism of current the CSO advocacy literature, as outlined above, have previously been raised within the neo-institutional field.

A range of theories stemming from institutional entrepreneurship are particularly relevant when studying the impact of Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen on the enactment of the Danish Aliens Act of 1983. One of these is a tool inspired by Lewin’s three phase change model (Lewin, Reference Lewin1947). Building on this model, institutionalists have formulated three forms of framing to initiate institutional change. These include diagnostic framing, which aims to identify current issues; prognostic framing, focused on proposing alternatives; and motivational framing, aimed at mobilizing allies to support the new alternative (Battilana et al., Reference Battilana, Leca and Boxenbaum2009). As the analysis will unfold, HGH followed this template throughout his advocacy endeavors.

Furthermore, institutional scholars have identified certain characteristics of successful institutional entrepreneurs, which likewise prove relevant when studying HGH. First, they are likely to be perceived as legitimate by multiple stakeholders in the field (Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Hardy and Lawrence2004). Second, they possess a high level of ‘reach centrality’, defined as having access to many field members through a limited number of intermediaries (Oliver & Montgomery, Reference Oliver and Montgomery2008).

In the analysis, I conduct an empirical study that utilizes these notions to explore the impact of HGH in the advocacy process prior to the enactment of the Aliens Act of 1983. By illustrating the utility of these concepts, I argue that the shifting emphasis on agency within CSO advocacy literature will benefit from incorporating a focus on individual actors. However, before delving into the analysis, I first introduce the empirical material used in the study.

The Empirical Material

To examine how Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen acted throughout the process leading up to the enactment of the law, I have gained access to his private archive.Footnote 2 The archive consists of letters to various people, including central figures in the DRC, lawyers in his network, other members of the commission and members of parliament. Additionally, the archive consists of documents related to the process such as reports and newspaper articles.

HGH’s pivotal role in the process makes him a particularly compelling subject for study. Within the law preparing commission, he led the minority group, authored their proposal and served as their public spokesperson. Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen can be perceived as an ‘Organizational Centaurs’—half man and half organization. Organizational Centaurs are individuals operating on behalf of the organization they are affiliated to, which provide them with resources. However, they also leverage their personal attributes and abilities as representatives (Ahrne, Reference Ahrne1994). As chair of the DRC from 1977 to 1984, HGH represented 12 affiliated organizations advocating for refugee rights, providing him substantial resources, particularly moral legitimacy (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995). Beyond organizational ties, his personal credentials as a Professor of LawFootnote 3 enabled him to influence the process significantly. His legal expertise was crucial in crafting a high-quality legal text. Additionally, as the analysis will elaborate, he adeptly utilized his professional network outside the DRC to gather insights and case examples for public advocacy. Moreover, HGH demonstrated skilled political maneuvering, leveraging the political circumstances in his favor. Consequently, HGH played a crucial role in the legislative process and its outcome, proving indispensable in garnering support for the minority’s alternative proposal. Therefore, studying him as an individual is essential for a comprehensive understanding of the genesis of the Danish Aliens Act of 1983.

Analysis of Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen’s Advocacy

The analysis is structured as follows: I begin with a brief overview of the contextual setting surrounding the law preparing commission for the Danish Aliens Act of 1983. Next, I describe the advocacy tactics employed by HGH throughout the process. This section first examines his tactics within the commission and prior to the parliamentary proceedings, followed by an analysis of his tactics outside the commission, particularly in the public media.

The Establishment of the Law Preparing Commission

Before delving into the actions of Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen, I briefly present the societal developments preceding the establishment of the law preparing commission. Despite the paper’s emphasis on actors’ agency, knowledge about the context in which HGH operated is relevant, as his ability to leverage the societal structures during the process, was of great importance for his impact on the enacted legislation.

The economic downturn triggered by the 1973 oil crisis brought about significant changes in the Danish migration debate during the 1970s. Increasing unemployment caused by the economic rupture led to turbulent times in Danish politics. This era was characterized by numerous governmental changes and constellations, accompanied by the emergence of new political parties. The election in 1973, known as the ‘landslide election’ in Denmark because 44% of voters changed their party affiliations, marked a turning point in the migration debate. The previous consensus of welcoming foreigners to Denmark was contradicted by more restrictive voices seeking to tighten immigration legislation. The Progress Party (Fremskridtspartiet), a far-right, anti-immigration party, entered parliament with 15.9% of the votes (Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen, Busck and Poulsen2002) and introduced new perspectives that resonated with a substantial portion of the population, not previously represented in parliament (Jensen, Reference Jensen2000, p. 428).

The media attention regarding foreigners also had a significant impact. In the early 1970s the media primarily focused on the economic challenges posed by unemployed foreign laborers who had migrated to Denmark in preceding decades (Brøcker, Reference Brøcker1990; Jensen, Reference Jensen2000). This scrutiny prompted administrative restrictions on access to and residence in Denmark, resulting in cases where foreigners were stranded due to deficient legislation. These cases were highlighted by the media, drawing attention to the legal protections afforded to foreigners in Denmark (Brøcker, Reference Brøcker1990). In 1977, amid several controversial expulsions of foreigners, the debate on legal protections for foreigners in Denmark reached a peak (Jensen, Reference Jensen2000). In response to the mounting criticism, the Social Democratic Minister of Justice, Erling Jensen, established a law preparing commission to conduct a comprehensive review of Danish Aliens legislation, which main task was to ‘[…] aim at giving foreigners an increased legal protection’.Footnote 4

Traditionally CSOs have been involved in legislative processes in Scandinavia (Blom-Hansen & Daugbjerg, Reference Blom-Hansen and Daugbjerg1999). Accordingly, the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), representing 12 major humanitarian organizations on migration-related topics, was invited to contribute a representative to the legislative commission (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Christensen, Humann, Johannesen, Jørgensen, Kjær, Kjærum, Lassen and Vedsted-Hansen1995). CSOs in Scandinavia were considered strong allies of the welfare state, responsible for welfare services (Amnå, Reference Amnå2006; Trägårdh, Reference Trägårdh2007). This also applied to the DRC, which effectively functioned as a state authority handling all issues related to asylum seekers. It was responsible for the integration of refugees, including providing basic supplies, education, accommodation, and counseling,Footnote 5 with all expenses covered by the Ministry of Social Affairs.Footnote 6 The DRC was thereby closely affiliated to the Danish welfare system and was perceived as legitimate by most stakeholders, including state departments and the organization’s constituents. As representative of the DRC, HGH were accordingly considered a legitimate figure by most actors in the process, which is a crucial enabling condition for a successful institutional entrepreneur (Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Hardy and Lawrence2004). The following analysis outlines how HGH utilized this favorable position to exert influence over the legislative process.

Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen’s Agency During the Legislative Process

The structural elements, such as the above-mentioned inclusion of CSOs in legislative processes and media coverage of foreigners, played crucial roles in the legislative process. However, as the following sections examines, HGH and the DRC’s adept utilization of the structural context to maximize their impact on the legislative process, was equally significant.

The analysis unfolds in two sections: initially, focus is on the advocacy efforts undertaken by HGH within the commission itself. This section elucidates the actions taken by HGH during the commission’s deliberations to maximize the influence of the minority. Subsequently, the analysis shifts to their broader outreach beyond the commission’s confines, particularly through engagement in the public media. Here, I explore the public advocacy tactics employed by both the DRC and HGH in the months leading up to the parliamentary proceedings, through which they succeeded in motivating public and parliamentary opinion in favor of the minority proposal.

Advocacy Tactics Within the Commission

As mentioned in the introduction, the law preparing commission diverged into two opposing groups during their work: ‘the minority’ and ‘the majority’. The minority consisted of HGH together with Lars Langkjær, a representative of the Lawyers’ Council, and Karen Andersen, a representative of the Ministry of Social Affairs. The majority group included the commission’s chair, Supreme Court Judge Peter Christensen, and six civil servants from various ministries and the police department administering foreigners. The dispute between the two groups revolved around their different approach to the degree of restrictiveness in the legislation. The minority group endorsed an approach, which aimed at formalizing the rules in the legislation to a greater extent, which would leave less room for the civil servants to decide in the specific cases. This approach would, according to them, result in foreigners being treated according to the same guidelines, as they were more clearly outlined. In contrast, the majority group advocated for an approach, allowing more discretion for decisions made by civil servants.Footnote 7

The commission’s working process was marked by an asymmetric power relationship between the two groups. The majority, holding the chairmanship of the commission and thereby controlling its secretariat, wielded a significant level of control over the process. HGH sought to change this dynamic by influencing the process on matters he deemed crucial. This became evident prior to the commission’s deliberations on asylum, where an unexpected change in the commission’s schedule, expediting the asylum debate, prompted HGH to swiftly convene the DRC’s asylum committee. He noted:

‘Since I wanted to take the initiative in the committee at this point and present draft provisions myself, I am running out of time.’Footnote 8

In the call to the meeting, he stressed the urgency of garnering unanimous support for a draft proposal of the legal text, which he had crafted months before the imminent debate in the commission. HGH emphasized that by providing a prepared legal text, he aimed at ensuring that the framework for negotiations was based on premises which he had defined.Footnote 9 This instance underscores HGH’s perception of influencing the process as instrumental in shaping the outcome of the commission’s efforts. Accordingly, the tactic pursued by HGH aligns with the attempt to provide a prognostic framing by outlining how the issues could be resolved. He thereby sat the agenda, mirroring Lukes’ second face of power (Lukes, Reference Lukes1974).

Illustrating the perceived importance of controlling the process, the majority likewise sought to influence it, by presenting a new draft of the legislation close to the deadline. According to a letter from HGH to the leading figures in the DRC, this new draft included numerous regressions from the majority’s previous proposals, which he perceived "as purely motivated by tactical reasons."Footnote 10 Additionally, the minority group was frustrated with the lack of support from the commission’s secretariat. In a letter to one of his partners in the commission, lawyer Lars Langkjær, HGH stated, “we should not rely on support from the secretariat or cooperativeness from the commission’s leadership.”Footnote 11 This indicates how the minority felt that the majority group utilized their power over the secretariat to their advantage. By influencing the process, both groups attempted to define the premises of the negotiations.

The following section elaborates on some of HGH and the DRC’s tactical considerations preceding the parliamentary proceedings. This section focuses on the outcomes of the commission’s work rather than the process.

Design and Positioning of the Minority Proposal

It is unclear exactly when, but at some point, the minority group realized that reaching a compromise with the majority group within the commission was unattainable. Consequently, they decided to offer a comprehensive alternative legislative proposal alongside the majority’s proposal, rather than simply dissenting on the many paragraphs they opposed. The following sections examine HGH’s deliberations on how to formulate, design, and position the minority’s proposal juxtaposed against the majority’s proposal. This too illustrates the attempt by HGH to provide a prognostic framing, which was prevalent throughout HGH’s advocacy strategy.

Three factors shaped the minority’s proposal. First, they genuinely believed that their proposal best met the terms of reference given to the commission. As will be shown in the later section on outsider tactics, the minority repeatedly emphasized how their proposal, in contrast to the majority proposal, enhanced foreigners’ legal protection. Secondly, as the chair of an organization consisting of 12 different organizations with varying viewpoints, HGH was obliged to craft a proposal acceptable to all the affiliated organizations. Thirdly, decisive for the minority’s ability to garner sufficient support for their proposal, was the position of the proposal in relation to the parliamentary composition.

As presented earlier, the landslide election of 1973 set the backdrop for the migration debate in the 1970s and 1980s, impacting the legislative process in broader terms. However, the election in 1982 had more direct influence on the outcome of the process. Following the 1982 election, a coalition of four center-right parties formed a government with a parliamentary majority, supported by the center-left Social Liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) and the Progress Party (Fremskridtspartiet). While these parties aligned on financial policies, they diverged sharply on other value-based political topics. The Social Liberal Party could form an alternative parliamentary majority with the left-leaning parties. This alternative majority has most prominently been known regarding foreign affairs for the, in Denmark notoriously known, ‘footnote policy’ regarding NATO issues (Villaume & Rasmussen, Reference Villaume and Rasmussen2007). However, also regarding the Aliens Act, this alternative majority was decisive.

Given the composition of parliament, HGH considered the positioning of the minority’s proposal as important to secure sufficient parliamentary support. This strategic stance was articulated in a letter addressed to a member of the Left Socialists (Venstresocialisterne), a very left-leaning party. In this correspondence, HGH clarified that the minority’s proposal intentionally maintained a strategic distance from the most left-leaning factions, while simultaneously contrasting with the majority draft to position it at the opposite ideological spectrum.Footnote 12 This delicate balance between an idealistic humanistic approach advocated by the left-leaning parties and a pragmatic administrative perspective emphasized by the right side of parliament was crucial. The Social Liberal Party particularly underscored this balance during the parliamentary proceedings.Footnote 13 This positioning aligns with the motivational framing (Battilana et al., Reference Battilana, Leca and Boxenbaum2009) as HGH sought to fit the proposal with the Social Liberal Party, which was crucial for garnering support from the alternative parliamentary majority.

Another aspect of the design of the minority proposal involved structuring it in parallel with the majority’s proposal to serve as a clear alternative. Instead of designing their draft in an alternative order, they intentionally aligned each paragraph of their proposal with the corresponding section of the majority’s proposal.Footnote 14 Consequently, the commission’s report presented each paragraph proposed by the majority followed by an alternative formulation by the minority, effectively showcasing the latter’s more liberal approach. This approach facilitated a direct comparison of the two versions of the legislation, enabling members of parliament to assess the contrasting perspectives.

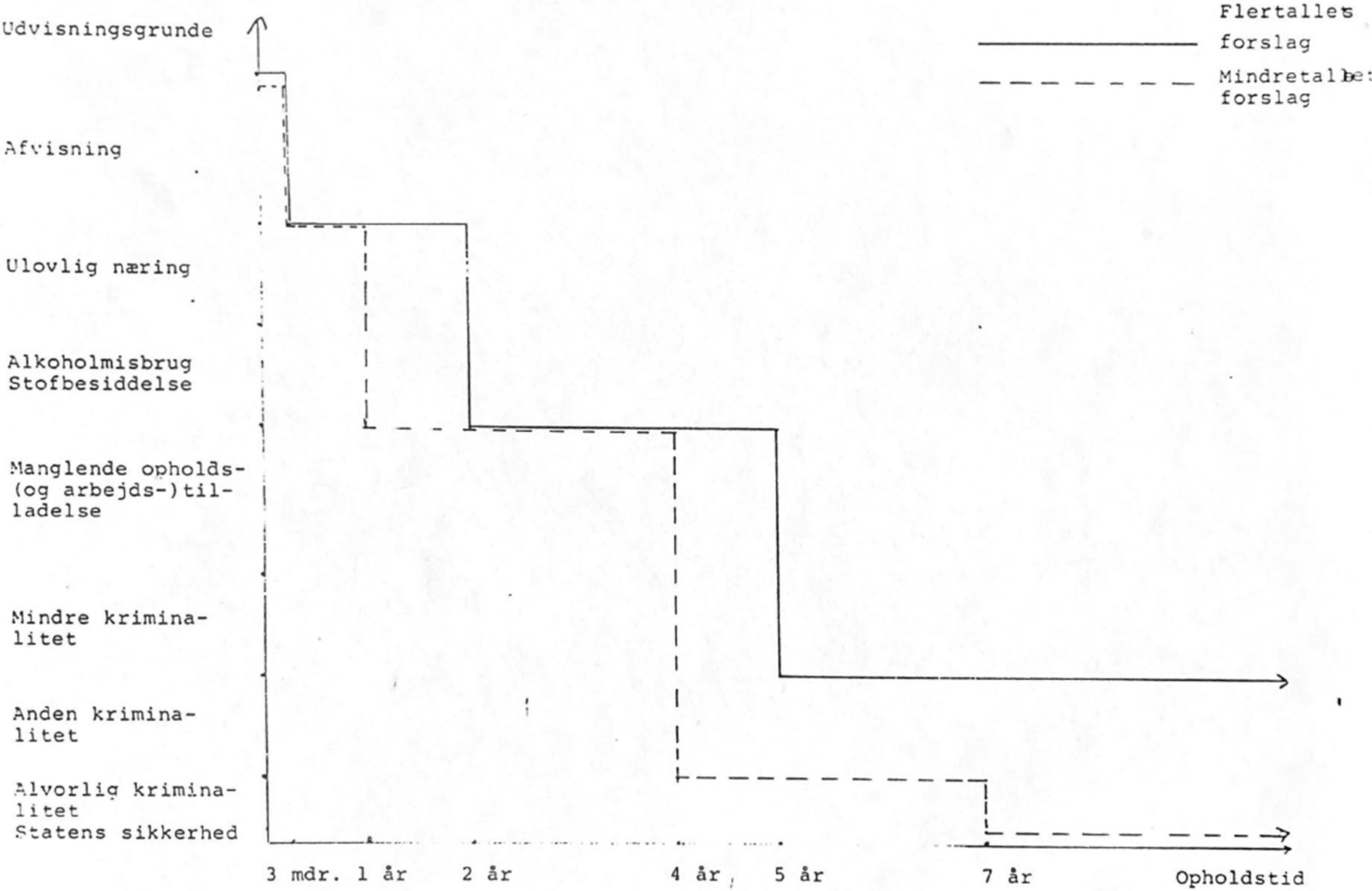

To underscore the intend of facilitating direct comparison, especially concerning the enhanced legal protection of foreigners, HGH created a graphical overview of the two proposals. This graph illustrated the relationship between various grounds for expulsion, categorized by the seriousness of the crime, as depending on the duration of residence in Denmark.Footnote 15 It visually demonstrated how the minority proposal provided greater legal protection to foreigners after fewer years of residence in Denmark. Throughout the negotiations, members of parliament frequently highlighted the contrasts between the paragraphs, recognizing the minority’s proposal as more favorable,Footnote 16 which underscores the importance of the direct comparability between the two proposals (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Graph illustrating the difference between the minority and majority proposal. The dotted line being the minority. The graph shows the relationship between time of residence and grounds of expulsion in terms of seriousness of crime committed

Thus, HGH positioned the minority’s proposal as a clear alternative for parties capable of forming a majority. By aligning it with affiliated organizations’ views, placing it on the ‘relative middle’ of the political spectrum, and ensuring comparability with the majority’s proposal, HGH created a prognostic framing that suited the parliamentary composition. Additionally, HGH and the DRC’s public presence played a key role in shaping the motivational framing to garner public and parliamentary support, as discussed in the following section.

Outsider Advocacy Tactics

In the months leading up to the parliamentary proceedings, HGH, maintained a prominent public presence through various means, including publishing debate articles in newspapers and an article in a professional education journal. Furthermore, upon the release of the commission’s report to the public, he, together with his partners from the minority group, published an op-ed in the center-right newspaper Berlingske Tidende. The DRC likewise issued a statement regarding the commission’s proposals. The following presents the tactics pursued in these publications.

Continuation of the Direct Tactics to Provide a Diagnostic, Prognostic and Motivational Framing

The communication strategy of the minority and DRC continued their approach within the commission, emphasizing how their proposal would improve foreigners’ legal protection while ensuring practical administrative feasibility. Their public advocacy efforts incorporated the diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing as outlined by Battilana et al. (Reference Battilana, Leca and Boxenbaum2009).

First, they presented a diagnostic framing by linking the need for new legislation to the shortcomings of the previous administrative practices, which had led to the establishment of the commission. Second, they offered a prognostic framing by demonstrating how the minority proposal would address the issues created by the previous legislation; while, the majority’s proposal would maintain these problems. Through these arguments, they utilized the public media to garner support for their proposal, thereby providing a motivational framing.

In a letter to the affiliated organizations, HGH explained that the goal of the public appearances was to associate the minority’s proposal with enhanced legal protection for foreigners while maintaining a practical and feasible approach.Footnote 17 A recurring argument in their public statements was the critique of the majority’s intention to maintain existing practices, which allowed civil servants a certain degree of discretion in decision-making. In their op-ed, the minority group expressed concerns that preserving these practices would fail to improve legal protections for foreigners. They argued that their proposal provided more formalized administrative practices and rules, which they believed would ensure a more equitable and consistent approach, ultimately strengthening legal protections for foreigners. Although they acknowledged that both proposals sought to balance humanistic concerns with administrative practicalities, they emphasized that:

‘[…] we believe our proposal better captures the difficult balance between humanitarian aspirations and practical necessity.’

The same argument was used by the DRC in their public statement on the commission’s report. Here they stated that the DRC’s affiliated organizations…

‘[…] could have wished for more far-reaching proposals than those presented by the minority. However, their proposals are grounded in reality—while also meeting the expectations of many who hope for a more humane approach […].’ Footnote 18

Thus, by arguing that the need for a new legislation stemmed from the previous practice, which was explicitly mentioned in the terms of reference in the commission, HGH and his minority companion managed to present a diagnostic framing presenting the previous practice as the fundamental problem and additionally portraying the majority’s proposal as a continuation of this approach.

The Use of Reach Centrality to Provide Exemplary Cases

The following section presents how HGH throughout the process acted in accordance with the institutional entrepreneurship theory by utilizing his reach centrality (Oliver & Montgomery, Reference Oliver and Montgomery2008). During the process, HGH reached out to lawyers in his network with experience in the immigration field, requesting insights into legal cases that exemplified potential consequences associated with various elements of the legislation.Footnote 19 Through these cases, HGH were able to compare the outcomes of the two law proposals, and thereby illustrate the consequences of the current administrative practices that the majority sought to uphold. This thereby supported how the minority’s proposal enhanced the legal protection of foreigners compared to the majority’s proposal.Footnote 20

One illustrative example of how HGH used cases for his cause involved the expulsion of a young Filipino woman expecting a child with a Danish man. This case had garnered considerable media attention around Christmas 1982 when Danish Bishop Hans Martensen initiated a hunger strike against her expulsion.Footnote 21 HGH engaged in the debate by asserting that the expulsion was contrary to the commission’s interim report on the administrative practice of expelling foreigners, presented in 1979. Following this, he argued that the minority’s proposal would prevent such cases by enhancing the protection of foreigners in similar situations.Footnote 22 Similar cases were used throughout the process and had some impact, evidenced by the frequent use of arguments referring to the cases during the parliamentary proceedings.Footnote 23

In addition to HGH’s presence in the larger newspapers, he also published an article in the Danish journal “Education”.Footnote 24 In this article, HGH elucidated on the process the commission had went through and the differences between the two opposing proposals. The article provides an illustrative example of how HGH’s communication aimed at comparing the majority and minority proposal against each other. By this he continued the strategy from inside the commission by providing a prognostic framing that would better solve the fundamental issues of the current situation. En ny udlændingelov, Op-ed in Dansk Politi, April 8, 1983.

The Opposing Actors

Interestingly, the majority group in the commission was largely absent from the public debate. This was likely because the majority proposal had the government’s support, meaning their perspective was primarily expressed by the conservative Minister of Justice, Erik Ninn-Hansen. In an article published in the right-wing newspaper Jyllandsposten in April 1983, he opposed the minority proposal by expressing concerns about the potential repercussions of the minority proposal, warning against threats to the Danish nation-state and the potential for racial unrest in society, due to the increasing number of foreigners entering the country. This stance elicited strong reactions from other parliamentary parties and editorial critiques in leading newspapers (Brøcker, Reference Brøcker1990). The overarching media coverage prior to the parliamentary decision was dominated by the minority and those supporting this perspective; whereas, the majority group were largely absent, which is considered an important factor for the enactment of the minority proposal in previous research (Brøcker, Reference Brøcker1990).

Summary of the Analysis

The DRC and Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen pursued a cohesive strategy both within the commission and in the public debate. HGH’s personal attributes, his legitimacy as a representative of a major humanitarian organization and a law professor endowed him with strong legitimacy in the legislative process. His ability to leverage his ‘reach centrality’ in terms of his network of legal professionals, to mobilize public support for the minority proposal, was crucial in formulating a viable alternative and garnering support for the proposal, both in public discourse and among key members of parliament.

The three forms of framing from the institutional entrepreneurship literature are particularly well-suited for understanding HGH’s advocacy efforts. First, he employed diagnostic framing by linking the fundamental problems in the existing legislation to flaws in current administrative practices, effectively portraying the situation as untenable. Building on this, he utilized prognostic framing by juxtaposing the majority’s proposal with the minority’s, highlighting how the latter addressed the deficiencies in the legal treatment of foreigners. This approach underscored the minority’s proposal as a viable solution to the identified problems and as a more effective alternative to the majority’s proposal. Lastly, through the strategic use of exemplary cases and by structuring the legislative proposal to allow for direct comparison with the majority’s proposition, HGH successfully garnered public and parliamentary support for the minority proposal, thereby applying motivational framing to advance his advocacy goals. The analysis above demonstrates the value of the neo-institutional concepts in understanding the legislative process. In the following section, I explore how existing CSO advocacy theories could be applied to examine this case. By outlining how this analysis would unfold, I demonstrate that the existing theoretical frameworks are insufficient to explain key aspects of the advocacy process, particularly regarding the influence of individual actors.

The Insufficiency of Current CSO Advocacy Theory

As outlined in the introduction, existing CSO advocacy literature has insufficiently addressed individual agency, limiting our theoretical understanding of the comprehensive impact of these actors. As a result, there is a gap in theoretical tools to conduct such analyses. The following section describes how the case at hand could be analyzed using current CSO advocacy theory. This serves to highlight the need to incorporate theoretical concepts from institutional entrepreneurship to expand the analytical toolkit for understanding the impact of individual actors on advocacy processes.

According to a review of CSO advocacy literature conducted by Mosley et al. (Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023), the theories in this field can be categorized into three dimensions commonly used to analyze advocacy processes: tactics, goals, and motivations. Applying these dimensions to the case at hand provides a useful analysis, which offers some explanatory power, but ultimately falls short in fully capturing the impact of HGH as an individual.

A predominant focus in the CSO advocacy literature is on the influence tactics employed by organizations (Brinkerhoff & Brinkerhoff, Reference Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff2002). The literature typically distinguishes between direct and indirect tactics (Clear et al., Reference Clear, Paull and Holloway2018), often referred to as insider and outsider tactics in the context of interest groups (Binderkrantz, Reference Binderkrantz2005; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015; Grant, Reference Grant1978; Maloney et al., Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994). Both direct and indirect tactics involve two main channels through which organizations seek to exert influence. Direct tactics include utilizing either the ‘administrative channel’, which leverages connections within public administration, or the ‘parliamentary channel’, which involves engaging directly with decision-makers. In contrast, indirect strategies involve public engagement through media presence or public protests (Binderkrantz, Reference Binderkrantz2005; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015).

Regarding the dimension of goals, the literature examines what the actor aims to achieve. Here, a distinction is made between policy change, which focuses on influencing legislative outcomes, and social change, which aims to shape public opinion or societal norms (Mosley et al., Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023, p. 194). In terms of motivation, the literature explores why actors engage in advocacy, with Mosley et al. (Reference Mosley, Suárez and Hwang2023) proposing a dichotomy between self-interest and purely altruistic motivations.

In relation to influence tactics, the case demonstrates that the complementary use of both direct and indirect tactics was advantageous for HGH in gaining influence over policy. HGH effectively communicated with members of parliament while maintaining a prominent public presence. Regarding goals, the case emphasizes that the primary objective of the DRC and HGH was policy change, largely through efforts aimed at shaping public opinion in favor of their proposal. In terms of motivation, the DRC and HGH primarily emphasized an altruistic motivation, aiming to improve legislation in favor of foreigners in Denmark.

As illustrated above, existing theoretical frameworks offer valuable insights to understand CSO advocacy processes. However, the application of these theories would fail to fully capture the full picture of HGH’s advocacy efforts, as this paper has illustrated had significant impact on the legislative process. The outlined analysis using current CSO advocacy theory, would overlook key aspects of his advocacy efforts, such as positioning the minority’s proposal within the parliamentary context, using exemplary cases, utilizing HGH’s network and ensuring comparability between the proposals. These elements were crucial to HGH’s advocacy, highlighting the need for theoretical tools that can address these dimensions.

Conclusion

Through a case study of the legislative process leading to the enactment of the Danish Aliens Act of 1983, this paper has demonstrated how individual actors can exert significant influence on policy matters through deliberate advocacy tactics. While structural factors such as the parliamentary composition, the disruption of the migration policy consensus, and media attention played pivotal roles in shaping the decision-making process, the case also highlights the importance of recognizing the agency of both organizational and individual actors within CSO advocacy processes. Hans Gammeltoft-Hansen’s personal attributes, his legitimacy as a representative of a major humanitarian organization and a law professor, and his network of legal professionals were all crucial in formulating a viable alternative and garnering support for the proposal, both in public discourse and among key members of parliament. HGH’s ability to leverage the structural context was essential for the minority proposal to gain traction.

However, existing CSO advocacy literature has insufficiently addressed individual agency, limiting our theoretical understanding of the comprehensive impact of these actors. To address this gap, I propose that the CSO advocacy field should incorporate theoretical concepts from neo-institutional theory, specifically institutional entrepreneurship. These concepts hold significant potential for advancing future research on CSO advocacy, particularly by shedding light on the critical role individual actors play in shaping advocacy processes. By integrating these theoretical tools into the CSO advocacy literature, researchers can develop a more nuanced understanding of advocacy dynamics and outcomes. Such integration would provide a comprehensive explanation of how structural and individual factors interact to shape policy decisions, ultimately enriching both theoretical and practical approaches to the study of civil society organization’s advocacy.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen Business School.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interests.