1. Introduction

Legitimizing property rights over the resources that participants use in economic experiments, rather than distributing the resources randomly, has been shown to significantly affect behavior. For example, in dictator games (DGs), when the pot to be divided is provided by the experimenter, mean offers range between 20% and 30% (Camerer, Reference Camerer2003, Engel, Reference Engel2011). However, when the dictator earns the pot, offers are significantly lower (Cherry et al., Reference Cherry, Frykblom and Shogren2002). Oxoby and Spraggon (Reference Oxoby and Spraggon2008) confirm that dictators are less generous when they earn the pot and, notably, that offers are approximately 50% when the receiver earns it. Finally, when both the dictator and the receiver jointly produce the pot, offers tend to be proportional to one’s production (Konow, Reference Konow2000, Frohlich et al., Reference Frohlich, Oppenheimer and Kurki2004, Cappelen et al., Reference Cappelen, Hole, Sørensen and Tungodden2007).

Similar results have been observed in ultimatum games (UGs) where the receiver has the opportunity to accept or reject the proposer’s offer. When the pot to be divided is a windfall, the modal offer is an even split, as proposers anticipate that lower offers will be rejected (Guth et al., Reference Guth, Schmittberger and Schwarze1982, Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Boyd, Bowles, Camerer, Fehr and Gintis2004). In contrast, when the pot is jointly produced, offers are proportional to one’s production (Barber IV & English, Reference Barber IV and English2019). The authors suggest that in the absence of any legitimate claim to the pot to be divided, an even split is the expectation. However, proportionality dominates equality once the pot is jointly produced.

These results demonstrate the importance of norms in the emergence and maintenance of social behavior. We refer to norms as behavioral rules based on shared expectations between individuals about what is appropriate in a given situation (De Geest & Kingsley, Reference De Geest and Kingsley2021, Vostroknutov, Reference Vostroknutov2020, Fehr & Schurtenberger, Reference Fehr and Schurtenberger2018, Coleman, Reference Coleman and Lesser2000, Coleman, Reference Coleman1990, Elster, Reference Elster1989).Footnote 1 Further, norms have been shown to be context dependent, suggesting that behavior deemed appropriate may vary across strategically equivalent settings (Krupka & Weber, Reference Krupka and Weber2013). Thus, while altering the legitimacy of resources used in experiments does not alter the material incentives of subjects, they can alter the norms that subjects find appealing and thus choose to enforce, and in turn alter subject behavior. However, there is less evidence of a similar effect of earned property rights within public good games (PGGs). In voluntary contribution mechanism (VCM) designs, earned endowment heterogeneity has not been shown to significantly impact behavior. Both Cherry et al. (Reference Cherry, Kroll and Shogren2005) and Spraggon and Oxoby (Reference Spraggon and Oxoby2009) used the number of correctly answered Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) questions to determine the distribution of endowments within linear, single-shot, VCM designs. Although there are slight variations across their experimental designs, neither report any significant variation in contributions across groups with earned or unearned endowments.

Here, we investigate the impact of earned and unearned endowment heterogeneity when group members are able to use sanctions to enforce contribution norms.Footnote 2 The introduction of peer punishment into linear PGGs with unequal and unearned endowments has been shown to increase contributions, as groups are able to enforce an efficient, contribute-your-endowment norm (Reuben & Riedl, Reference Reuben and Riedl2013, De Geest & Kingsley, Reference De Geest and Kingsley2021).Footnote 3 However, linear PGGs are unique. Because the social optimum and Nash equilibrium are boundary solutions – contribute your entire endowment, or contribute nothing – behavior consistent with efficiency coincides with payoff equality, regardless of endowment heterogeneity.Footnote 4 The normative appeal of efficiency and payoff equality is intuitive and deviations are easy to observe, making it an appealing norm to enforce.Footnote 5 Further, linear PGGs create a conflict between a preference for efficiency, and any competing norm that would recognize legitimate claims created by earning one’s endowment. Groups that choose to adopt any norm beyond contributing one’s entire endowment must also accept a loss of efficiency. This detail stands in stark contrast to dictator and ultimatum games, where any distribution of the resources to be divided remains efficient.

To address this constraint of the linear PGG, we study earned property rights in a nonlinear PGG. In this design, the social optimum and Nash equilibrium lie in the interior of the choice space, allowing groups to maximize group earnings across any number of contribution patterns. In particular, our design produces three appealing patterns of contributions (Equal Contributions, Equal Proportions, and Equal Earnings), each of which may act as a focal point enabling groups to coordinate behavior (Schelling, Reference Schelling1960, Young, Reference Young, Durlauf and Blume2008, Krupka & Weber, Reference Krupka and Weber2013). Each of these contribution patterns maximizes group earnings but differs in how the benefits of cooperation are distributed, creating a possible tension between one’s individual distributive preferences and sustaining cooperation. By removing the efficiency cost across these opposing contribution patterns, this design allows us to more clearly observe whether earned property rights alter behavior in PGGs. Note that, following Reuben and Riedl (Reference Reuben and Riedl2013), we will refer to a contribution pattern that is identified as normatively appealing and observed in the data as a contribution norm.

In our Unearned condition, endowments are randomly allocated across participants and in our Earned condition, endowments are earned using a paid slider task (Gill & Prowse, Reference Gill and Prowse2019). In Unearned, we observe that both types adhere to a norm of contributing an equal proportion, of their endowment. However, in Earned, only Low types adhere to contributing an equal proportion while High types deviate and contribute less than an equal proportion. To understand this pattern we estimate the punishment received as a function of one’s deviation from the proportional contribution. We observe that deviations from a proportional contribution among High types are punished less severely in Earned relative to Unearned.

Results indicate that High types who earned their high endowment – despite deviating from the proportional contribution norm – received less punishment than those with an unearned endowment. This suggests that groups become more tolerant of deviations, from this proportional norm, when property rights are earned. This is consistent with findings that inequality is more acceptable when attributed to effort rather than luck (Almås et al., Reference Almås, Cappelen and Tungodden2020) and motivates additional research to understand how unequal groups reconcile individual distributive preferences while maintaining cooperation in social dilemmas.

2. Design

Each treatment included two parts, which were preceded by a real effort task, as described below. Each participant was randomly assigned to a group of four, which remained the same throughout the experiment. In each group, two members (High types) received an endowment of 70 Experimental Dollars (EDs) and two members (Low types) received an endowment of 30 EDs. Group members received the same endowment each period; once a High type, always a High type. Participants could earn EDs each period. Each participant received a $7 participation payment, and their total EDs were converted to US dollars such that 150 EDs = $1.

Each treatment was preceded by a paid slider task similar to Gill and Prowse (Reference Gill and Prowse2019). Each slider included a small marker that could be positioned along the slider at any point, ranging from 0 on the left to 100 on the right. During the 2-minute slider task, participants had a set of 50 sliders on their screen, and earned 2 EDs for each slider placed exactly at 50.Footnote 6 Across treatments, the slider task would either determine, or not, the allocation of the endowments. In our Unearned treatment, the slider task was completed but the allocation of individual endowments was random. In our Earned treatment, the two group members who earned the most during the slider task received the 70 ED endowment and the other two members received the 30 ED endowment.Footnote 7

2.1. Part 1

Part 1 includes three periods of a voluntary contribution mechanism and is designed to introduce the incentives of the experiment prior to introducing peer punishment. Each participant is asked how many EDs, from their endowment, they would like to allocate to a group account. Individual payoffs are described as follows:

\begin{equation*}\pi_{i} = (e_{i}-x_{i})+\frac{1}{n}\left(a\sum^{n}_{j=1}{x_{j}}-b\left(\sum^{n}_{j=1}{x_{j}}\right)^{2}\right)\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\pi_{i} = (e_{i}-x_{i})+\frac{1}{n}\left(a\sum^{n}_{j=1}{x_{j}}-b\left(\sum^{n}_{j=1}{x_{j}}\right)^{2}\right)\end{equation*}where ei is the member’s endowment and xi is their allocation (contribution) to the group account. The right hand side of the expression represents each participants’ earnings from the group account (the PG), with a = 6 and b = .025.

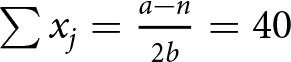

There is no unique Nash equilibrium with this payoff function, but individual best responses suggest that individual earnings are maximized when one equates the cost of allocating one of their EDs to their individual return from the public good (i.e.,  $\frac{1}{n}\left(a-2b\left(\sum{x_{j}}\right)\right)=1$). This condition holds when

$\frac{1}{n}\left(a-2b\left(\sum{x_{j}}\right)\right)=1$). This condition holds when  $\sum{x_{j}}=\frac{a-n}{2b}=40$ EDs, suggesting that each individual has an incentive to contribute to the group account whenever there are fewer than 40 EDs allocated in aggregate. Nash equilibria can thus be expressed as

$\sum{x_{j}}=\frac{a-n}{2b}=40$ EDs, suggesting that each individual has an incentive to contribute to the group account whenever there are fewer than 40 EDs allocated in aggregate. Nash equilibria can thus be expressed as  $x_{i}=\max\left[0,\frac{a-n}{2b}-\sum{x_{-i}}\right]$. As such, the symmetric Nash equilibrium implies that each group member contributes 10 EDs to the group account.

$x_{i}=\max\left[0,\frac{a-n}{2b}-\sum{x_{-i}}\right]$. As such, the symmetric Nash equilibrium implies that each group member contributes 10 EDs to the group account.

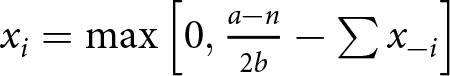

Similarly, there is no unique social optimum but following the logic above it can be determined that group earnings are maximized when  $\left(a-2b\left(\sum{x_{j}}\right)\right)=1$. This condition equates the group return to the individual cost of allocating and holds when

$\left(a-2b\left(\sum{x_{j}}\right)\right)=1$. This condition equates the group return to the individual cost of allocating and holds when  $\sum{x_{j}}=\frac{a-1}{2b}=100$ EDs. Therefore, any pattern of contributions such that 100 EDs are allocated to the group account will maximize group earnings. Importantly, when interacted with endowment heterogeneity, this feature allows groups to maximize group earnings in a variety of ways and gives groups the capacity to choose how the benefits of cooperation are distributed. That is, by varying how much High and Low group members contribute toward the the PG, groups are able to determine the distribution of earnings.

$\sum{x_{j}}=\frac{a-1}{2b}=100$ EDs. Therefore, any pattern of contributions such that 100 EDs are allocated to the group account will maximize group earnings. Importantly, when interacted with endowment heterogeneity, this feature allows groups to maximize group earnings in a variety of ways and gives groups the capacity to choose how the benefits of cooperation are distributed. That is, by varying how much High and Low group members contribute toward the the PG, groups are able to determine the distribution of earnings.

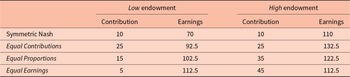

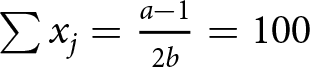

Normative analysis of distributive preferences often deploy a variation of a DG with a preceding production phase where each participants’ individual production is combined to generate the pot to be divided and focuses on equality and equity (Konow, Reference Konow2000, Frohlich et al., Reference Frohlich, Oppenheimer and Kurki2004, Cappelen et al., Reference Cappelen, Hole, Sørensen and Tungodden2007).Footnote 8 Adapting the principles of equality and equity to the PG presented here allows us to create three normatively appealing patterns of contributions that may serve as focal points.Footnote 9 Each of these focal points, which define a specific contribution from each type, may serve as a potential norm and is summarized in Table 1. Note that, in what follows we will reserve the term, norm, or contribution norm, to suggest a normatively appealing pattern of contributions that is observed in the data. The Equal Contributions benchmark suggests that each member should contribute 25 EDs to the group account and maintains an earnings difference between High and Low group members (132.5 EDs vs. 92.5 EDs). The Equal Earnings benchmark requires High types to allocate 45 EDs and Low types to allocate 5 EDs but equates their earnings at 112.5 EDs each period. Finally, the Equal Proportions benchmark splits the difference and requires each type to allocate half of their endowment. If earned endowments impact behavior within PGGs similarly to how they impact behavior in dictator and ultimatum games, we would expect a greater emphasis on equality in Unearned and on equity in Earned.

Table 1 Contributions and earnings for Low- and High-endowment group members

The instructions included tables showing participants how earnings varied across the range of possible allocations. Comprehension questions asked participants to solve for individual and group earnings at the Equal Contributions and Equal Earnings benchmarks to ensure this tension was recognized. These comprehension questions were checked prior to the start of the experiment to ensure that participants understood the payoffs.Footnote 10 At the end of each period of Part 1, each participant was shown their allocation to the group account, the total allocation to the group account, their period earnings, and their total earnings (the sum of their period earnings).

2.2. Part 2

Part 2 includes thirty periods and adds a punishment stage immediately following the allocation decision. Groups remained fixed across Part 1 and Part 2 (partner design). During the punishment stage, in addition to the information provided during Part 1, each participant was shown the individual allocations and corresponding endowments of each, other, group member (displayed in random order each period). Each group member was then given the opportunity to impose up to 10 reduction points upon each other group member. Each reduction point assigned a cost of 1 ED and each reduction point received a cost of 3 EDs.

3. Results

Data was collected at the UMass Amherst Cleve E. Willis Laboratory in April and October 2022. In total, 116 participants participated across 14 groups in Unearned and 15 groups in Earned, giving us a total of 3,944 individual observations. Each session lasted approximately 75 minutes, and average earnings (the sum of their period earnings, including the slider task) were $20.41 plus a $7 show-up payment. We discuss our results from Part 2 in three sections: contributions, punishment, and earnings.Footnote 11

3.1. Contributions

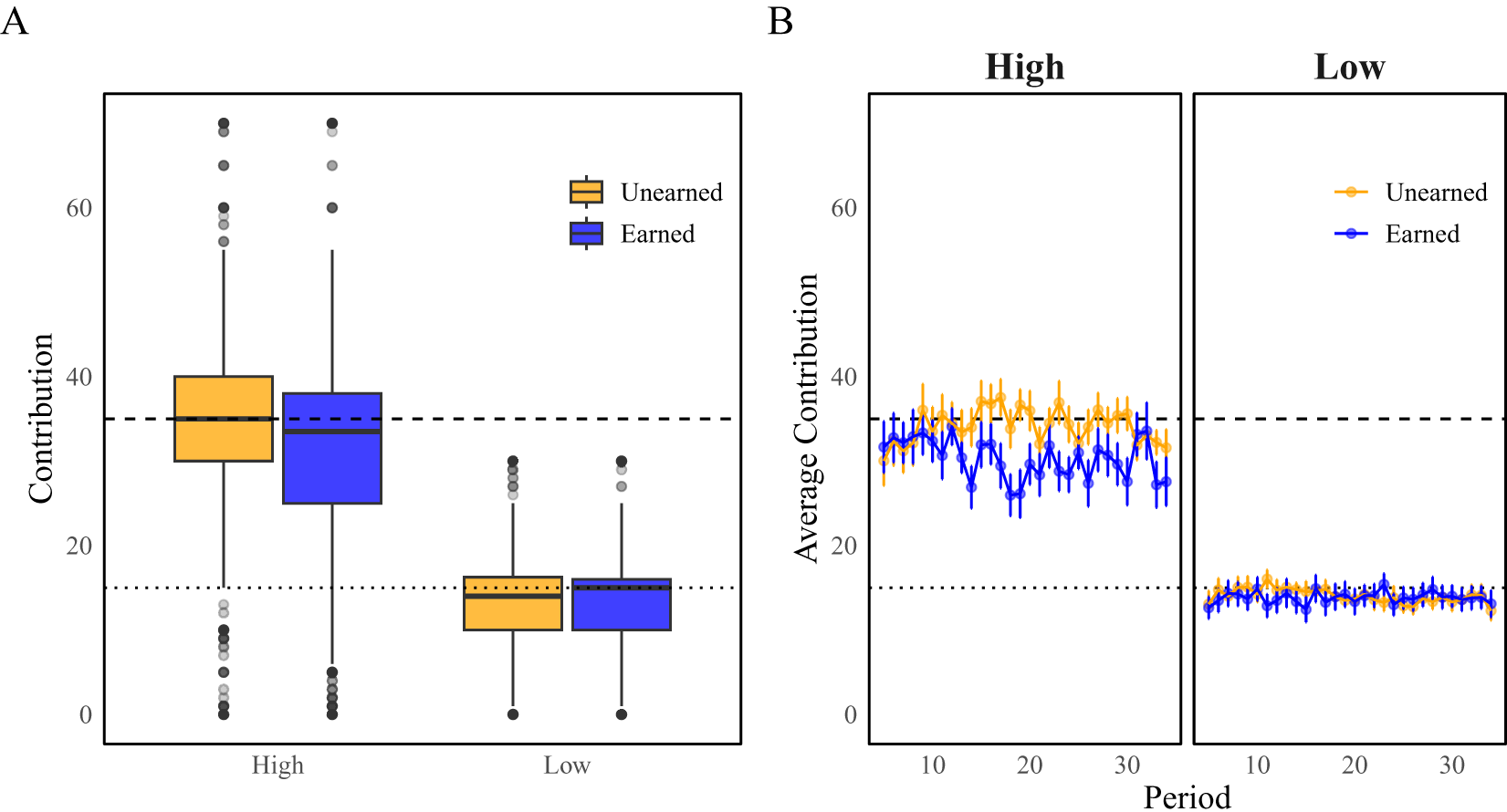

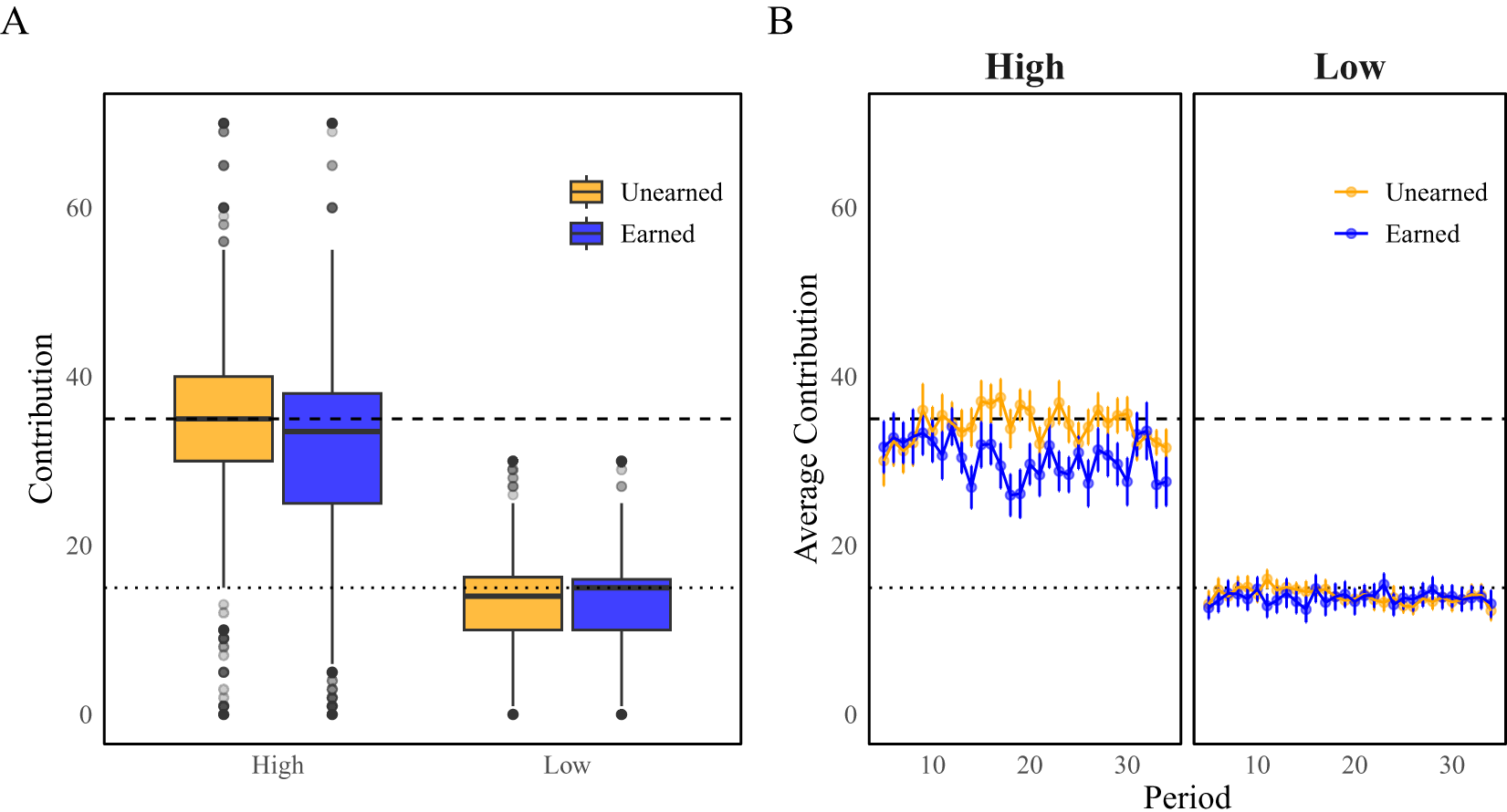

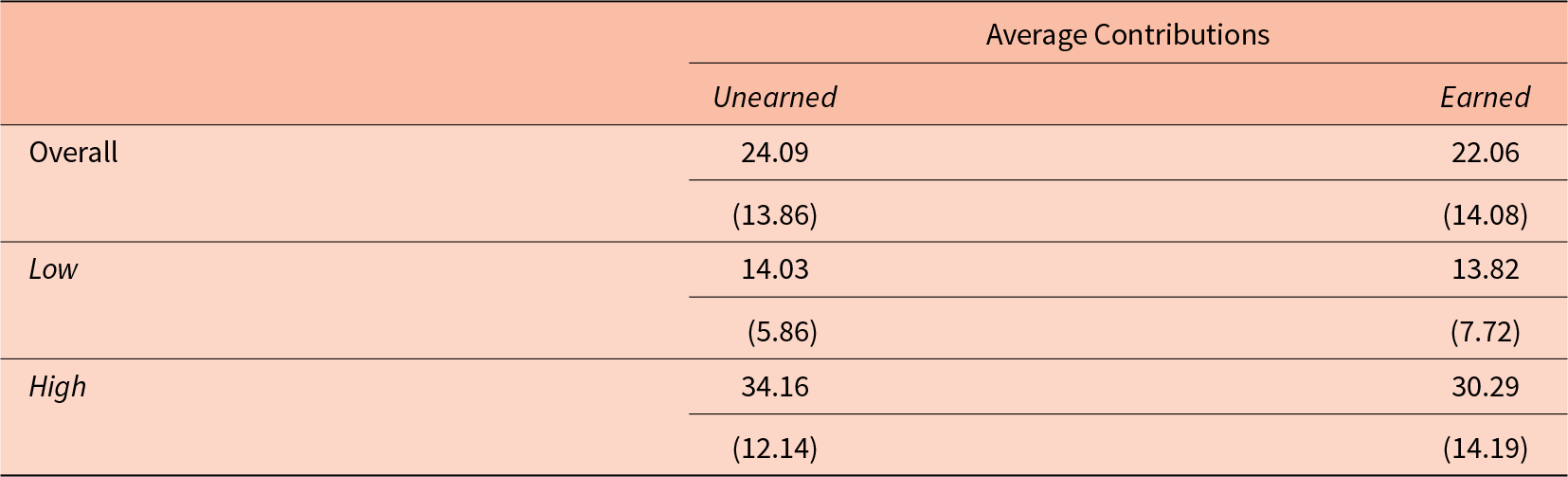

Table 2 shows average contributions overall and by endowment across conditions. Figure 1 shows the distribution of contributions in Panel A and the time series of average contributions in Panel B. In each panel, the dashed line indicates a proportional contribution (15 EDs for Low and 35 EDs for High).Footnote 12

Fig. 1 Panel A: Distribution of contributions. Panel B: Time series of average contributions with standard errors. In both panels the dashed and dotted lines mark the respective proportional contribution for High and Low types, respectively

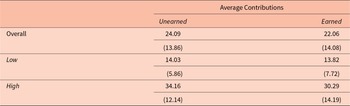

Table 2 Average contributions overall and by endowment across conditions. Standard deviations in parentheses

The data suggest that contributions among Low types are similar across conditions. Both the average contributions (14.03 vs. 13.82) and the medians (14 in Unearned and 15 in Earned; see Figure 1) closely match the proportional contribution of 15 EDs. Moreover, the time series indicates that these contributions remained stable across all 30 periods. In contrast, High types display more variability in their average contributions (34.16 vs. 30.29), although the medians (35 in Unearned and 33 in Earned) are closer to the proportional contribution of 35 EDs. The time series reveals that in the Unearned condition, average contributions for High types consistently hover around 35 EDs, whereas in the Earned condition, they remain below 35 EDs throughout.

To investigate the effect of earned property rights, we first compare average group contributions, by type, to the proportional contribution benchmarks (15 EDs for Low and 35 EDs for High).Footnote 13 In each condition, Low types conform to the proportional norm. Average group contributions among Low types do not significantly differ from 15 EDs in Unearned (Wilcoxon rank-sum: p = .241) or in Earned (WSR: p = .359). However, we observe that adherence to the proportional contribution (35 EDs) among High types varies by condition. In Unearned, average contributions are consistent with the benchmark; we are unable to reject adherence (WSR: p = .583). In Earned, average contributions significantly differ from 35 EDs (WSR: p = .022), rejecting the hypothesis that High contributed the proportional norm on average.

Further, we compare average group contributions, by type, across conditions.Footnote 14 We observe no significant differences across conditions; overall (WSR: p = .484), among Low types (WRS: p = .660), or among High types (WRS: p = .234). While the lack of significance across Low types is unsurprising given the observed difference (0.21 EDs), the null result across High types may reflect limited statistical power to detect the modest difference observed (3.87 EDs).Footnote 15 While we are unable to claim a significant difference across conditions, we conclude by emphasizing that only High types in Earned significantly deviate from the proportional contribution. Next we investigate whether earned property rights effected the deployment of punishment and whether this may explain the variation observed among High types.

3.2. Punishment

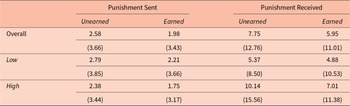

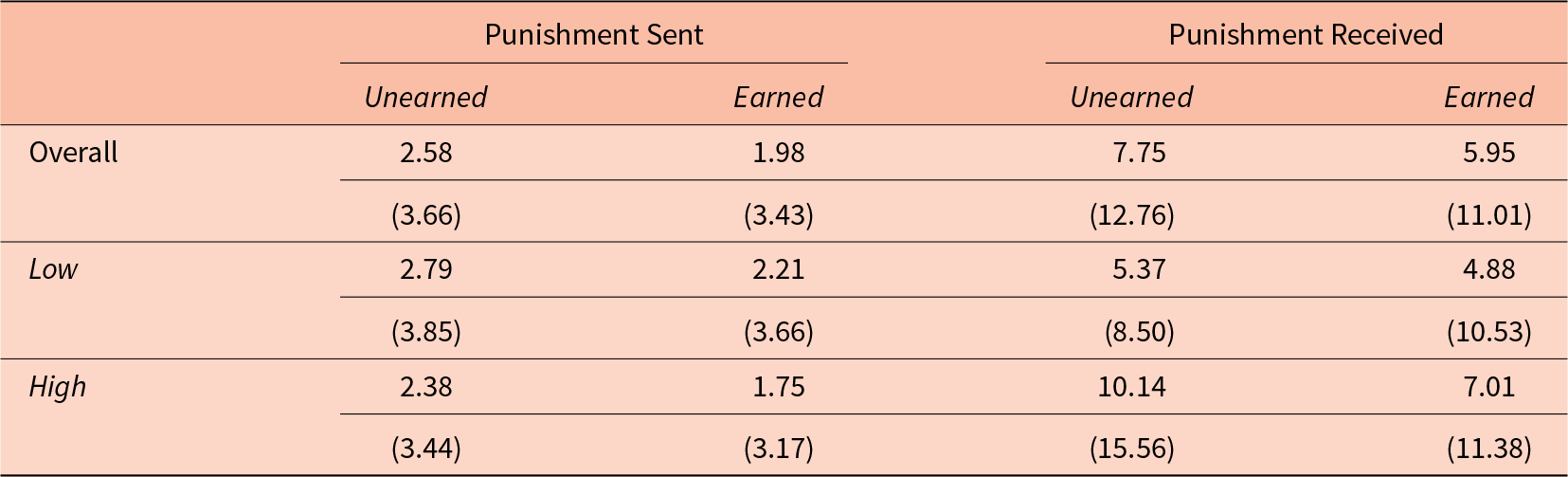

Table 3 shows average punishment, sent and received, overall and by endowment across conditions. In aggregate, across all contributions, there is no significant difference across conditions: in punishment sent overall (WRS: p = .354), across Low (WRS: p = .348), or across High (WRS: p = .377); or in punishment received overall (WRS: p = .354), across Low (WRS: p = .337), or across High (WRS: p = .275).

Table 3 Average punishment sent and received overall and by endowment across condition. Standard deviations in parentheses

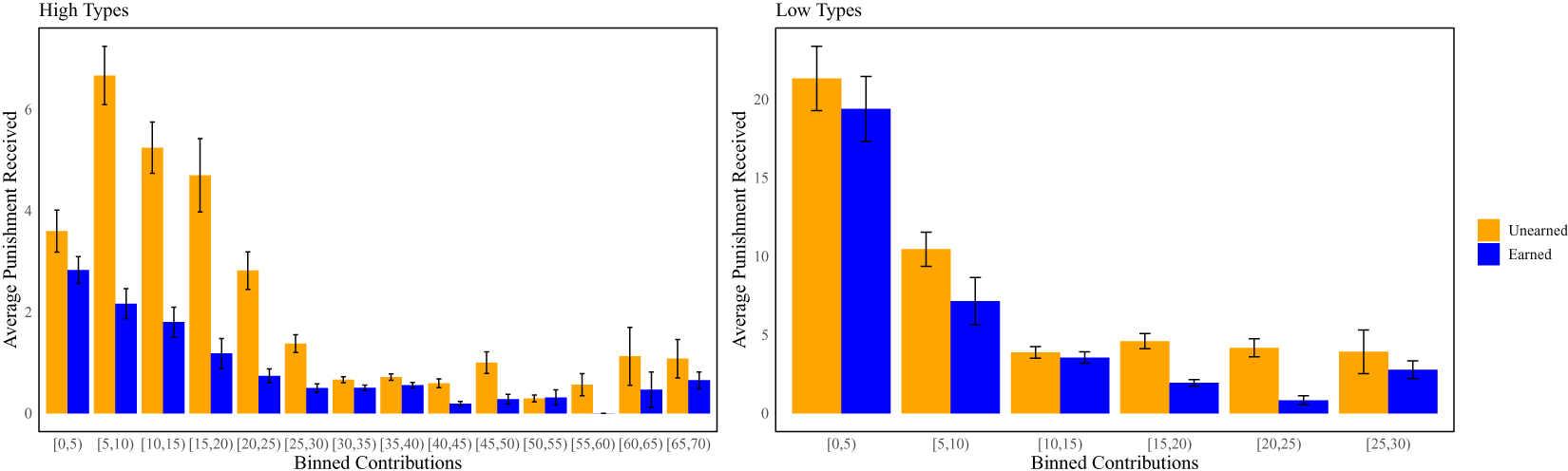

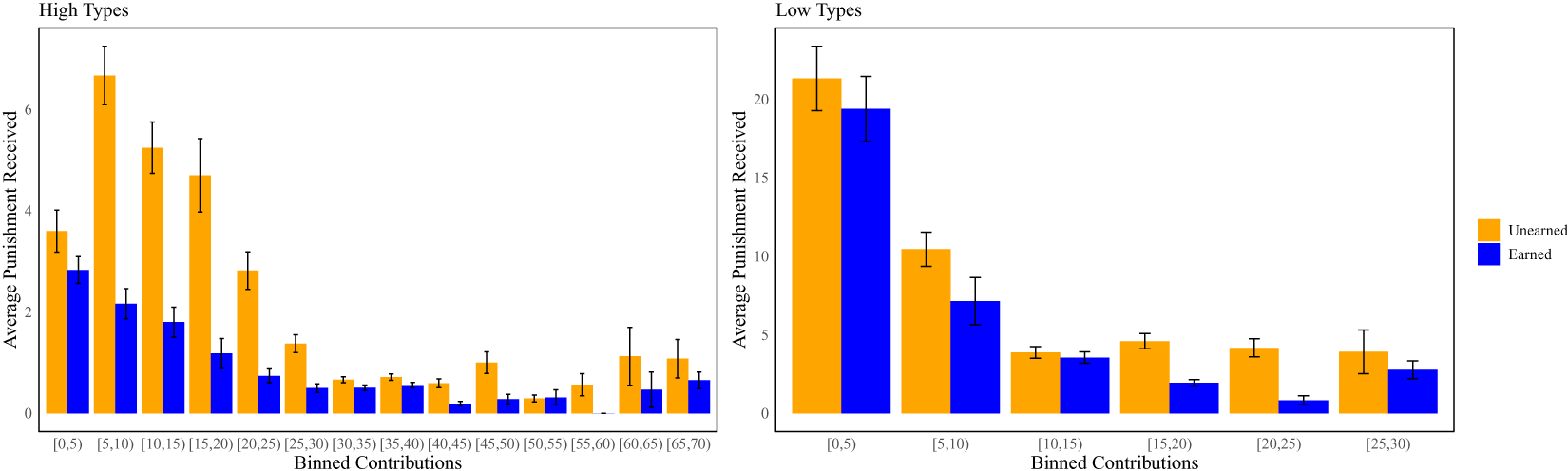

However when we consider the punishment received based on one’s contribution, we observe that earned, property rights shaped enforcement. Figure 2 presents the average punishment received based on one’s binned contribution. Among Low types, the amount of punishment received is similar across contributions. Among High types, we observe substantially more punishment received once their contribution falls below 30 EDs in Unearned. This suggests that deviations among High types were treated differently across conditions.

Fig. 2 Average punishment received by type, across conditions, based on one’s binned contribution

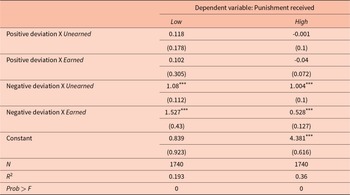

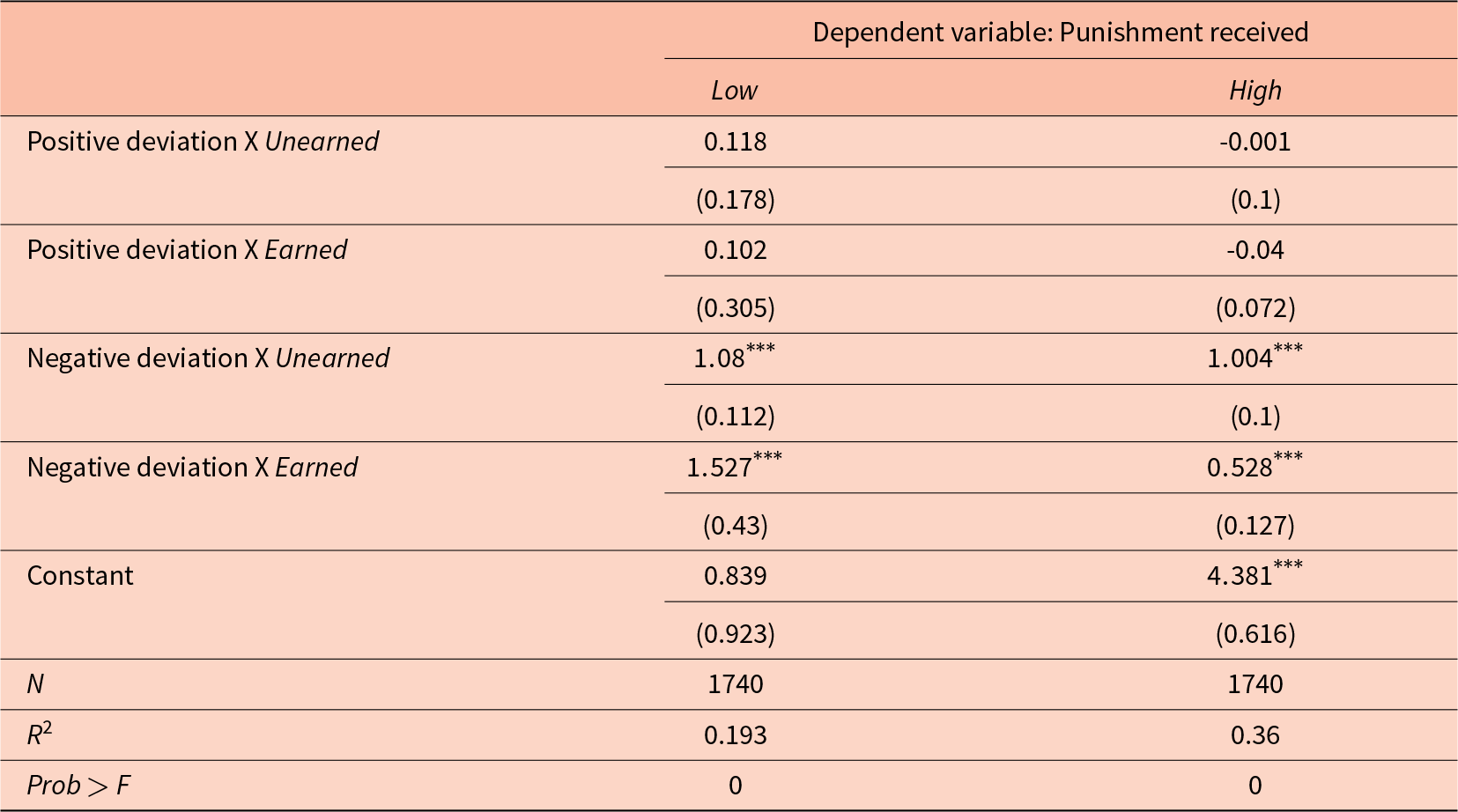

To better understand how earned endowments effected participants’ deployment of punishment, we estimate the punishment received given the deviation of one’s contribution from the proportional norm. We calculate the positive deviation and absolute value of the negative deviation of contributions from 15 EDs for Low and from 35 EDs for High. We then estimate a subject fixed effects model to predict the amount of punishment received by each endowment type, in each condition, with respect to the observed deviation.

The results presented in Table 4 suggest that punishment is deployed similarly across treatments. In both conditions, deviations above the proportional norm are not targeted while deviations below the norm are. Low types are similarly punished across conditions, receiving an average of 1.08 and 1.53 EDs in punishment for each ED less than 15 that they contribute. At the mean negative deviation, the marginal effect of this difference is insignificant (p = .421). In contrast, there is a notable reduction in the punishment received by High in Earned. High types receive an average of 1.00 EDs in Unearned and 0.53 EDs in Earned for each ED for which their allocation falls below 35. The marginal effect of this difference, at the mean negative deviation, is significant (p < .01). Group members in Earned appear to be more tolerant of deviations from the proportional norm by High types. Consistent with the observation that only High types in Earned deviate from the proportional contribution, this suggests that earned property rights lessened the expectation that High types adhere to the proportional norm.

Table 4 Subject fixed effects with standard errors clustered at the group level. Robust standard errors in parentheses

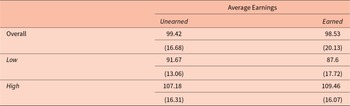

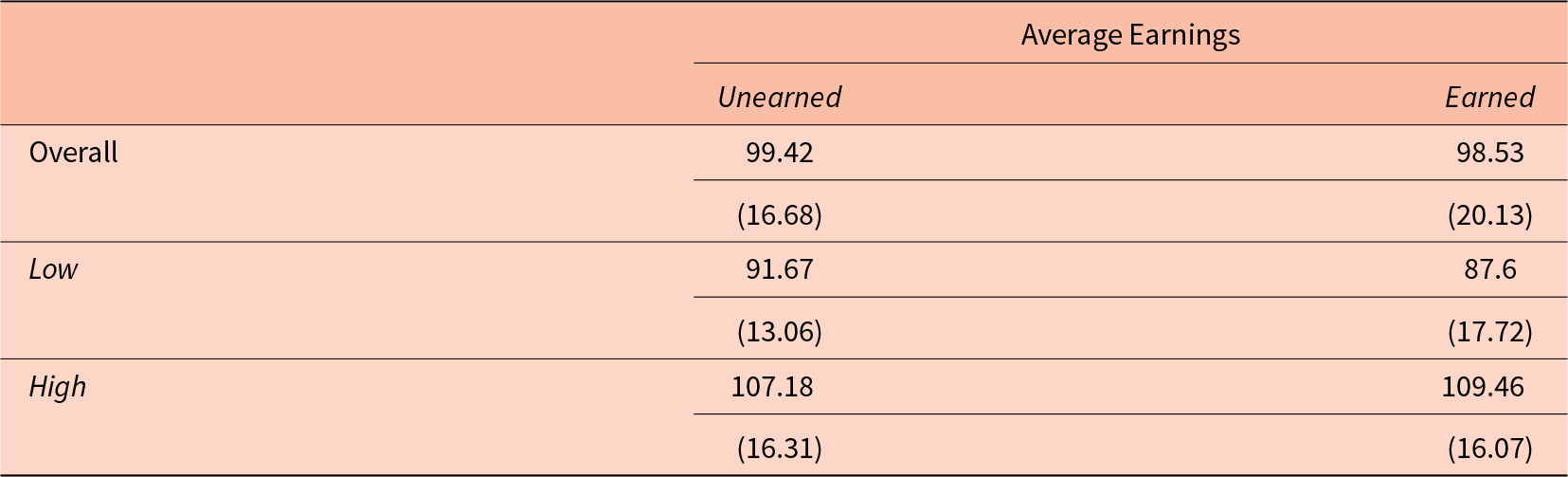

3.3. Earnings

Table 5 shows average period earnings overall and by endowment across conditions. Given the similarity in contributions and punishment across conditions, it is unsurprising that earnings are also similar. Earnings are statistically equivalent across treatments: overall (WRS: p = .813), across Low (WRS: p = .591), and across High (WRS: p = .591). Further, in both conditions, High types earn significantly more than Low types: Unearned (WSR: p < 0.01) and Earned (WSR: p < 0.01).

Table 5 Average period earnings overall and by endowment across condition. Standard deviations in parentheses

4. Discussion

This paper contributes to our understanding of how earned property rights impact behavior in PGGs. In contrast to the existing literature, our design considers inequality within an interior PG. The interior design allows groups to maximize group earnings across three normatively appealing patterns of contributions (Equal Contributions, Equal Proportions, and Equal Earnings). While each of these potential focal points maximizes group earnings, they vary how the benefits of cooperation are distributed across group members. Therefore, the design allows us to better understand how members within unequal groups balance their individual distributive preferences with maintaining cooperation in PG social dilemmas.

In the absence of any legitimate claim to one’s endowment, in our Unearned condition, we observe that both High and Low types adhere to a norm of contributing half of their endowment. However, with earned property rights, in our Earned condition, only Low types adhere to this proportional norm while High types deviate and contribute less than an equal proportion of their endowment. To better understand this variation across High types, we consider how property rights shaped the use of punishment. We observe that High types who contributed less than an equal proportion of their endowment were punished significantly less in Earned relative to Unearned. This suggests that groups were more tolerant of deviations from the proportional norm, by High types, when they had a legitimate claim to their higher endowment. While we do not observe a significant effect of earned property rights on individual earnings, tolerating lower contributions from High types increases inequality.

These results are broadly consistent with research investigating differences in societal tolerance of income inequality. Almås et al. (Reference Almås, Cappelen and Tungodden2020) show that one’s tolerance of inequality depends on the extent to which they attribute income differences to one’s individual effort or merit versus their luck. Specifically, they state that the US tends to tolerate higher levels of inequality than Norway because Americans attribute differences in income to one’s own effort or merit to a greater extent than Norwegians, who attribute differences more to luck. A similar effect has been observed in research looking at earned endowment heterogeneity in a linear PG with a formal mechanism which alters individual returns from the PG (Balafoutas et al., Reference Balafoutas, Kocher, Putterman and Sutter2013). The mechanism allows groups to determine how the earnings from the PG are distributed with respect to one’s contribution. At one extreme, the earnings from the PG are distributed equally without regard to one’s contribution and, at the other, the earnings are distributed proportionally to one’s contribution. Groups in both their earned and unearned treatments chose to distribute the majority of earnings proportionally, effectively solving the social dilemma, but overall, and particularly among Low types, there was a significant increase in proportionality when endowments were earned. As increasing proportionality reduces redistribution, this is consistent with a greater tolerance of inequality when endowments are earned. Indeed, Balafoutas et al. (Reference Balafoutas, Kocher, Putterman and Sutter2013) state that Low-endowment members cast votes as if they view inequality that disfavors them as being more acceptable when it is earned.

Future research is warranted to better understand how unequal groups solve the tension between individual distributive preferences and sustaining cooperation in public good social dilemmas.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank participants at the 2022 Economic Science Association North American Meeting and the 2022 New England Experimental Economics Workshop for helpful comments. Funding from Suffolk University and the University of Massachusetts Lowell is gratefully acknowledged.

Declarations of interest

none.

Statements and Declarations

The authors declare no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.