Introduction

Foreign policy is an important part of what governments do, yet surprisingly little research compares public attitudes about international affairs across countries. The question of what the public thinks about foreign policy has been studied extensively in the United States. Still, there remain unresolved questions concerning foreign policy opinions in other countries. We contribute to both the study of comparative politics and international relations by asking a simple question: Do the core constructs structuring American attitudes about foreign policy translate well to the mass publics of key European powers? Using data from the United States, United Kingdom, France and Germany, we identify a structure of foreign policy attitudes that fits opinion data in all four countries.

The questions of what Americans think about foreign policy and how they structure their views of foreign affairs has occupied analysts of foreign policy and political behaviour for more than five decades. The earliest attempts to answer this question concluded that there was little to discuss: Americans paid little attention to politics ‘beyond water's edge’ (Almond Reference Almond1960; Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964). This view was eventually replaced by work from Wittkopf (Reference Wittkopf1990, Reference Wittkopf1994) and Holsti and Rosenau (Reference Holsti and Rosenau1986, Reference Holsti and Rosenau1988, Reference Holsti and Rosenau1990) that identified opinion as structured by two distinct forms of internationalism, typically described as ‘militant internationalism’ (MI) and ‘cooperative internationalism’ (CI). While constructs resembling MI and CI have repeatedly been found, some work has found empirical support for additional attitudinal dimensions (Chittick et al. Reference Chittick, Billingsley and Travis1995; Kertzer et al. Reference Kertzer2014; Rathbun et al. Reference Rathbun2016; Richman et al. Reference Richman, Malone and Nolle1997). Although the exact number and content of dimensions in any factor‐analytic model is (in part) subject to the number and the content of indicators used, the question of cross‐national similarity of foreign policy constructs nevertheless remains unresolved. When using identical items across nations, how similar or different would the structures look?

Foreign policy attitudes are important because there is strong evidence for an electoral connection between public opinion and foreign policy (Aldrich et al. Reference Aldrich2006). When political office is at stake, politicians take notice (Cain et al. Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1979; Fenno Reference Fenno1978; Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). At the most basic level, foreign policy attitudes matter because they help shape how parties and candidates are evaluated as well as who holds office (Aldrich et al. Reference Aldrich2006; Baum & Potter Reference Baum and Potter2008; Gravelle et al. Reference Gravelle2014; Soroka Reference Soroka2003). In addition to the direct effect of a country's public opinion on making foreign policy, governments and leaders are possibly advantaged when they also understand the domestic public opinion environment in other countries and the constraints their counterparts face.

Despite its substantive importance, the literature on public opinion toward foreign policy remains marked by certain shortcomings. First, much of the literature relies exclusively on studies of American public opinion, or the comparison of American attitudes with those of a single nation (Bjereld & Ekengren Reference Bjereld and Ekengren1999; Hurwitz et al. Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Seligson1993; Jenkins‐Smith et al. Reference Jenkins‐Smith, Mitchell and Herron2004). Inferences about the content of foreign policy attitudes among mass publics writ large are obviously more tenuous when the bulk of the evidence derives from a single public. Second, many existing cross‐national analyses of foreign public opinion focus on specific issues – for example, joining the American‐led coalition invading Iraq in 2003 (Kritzinger Reference Kritzinger2003), a cooperative environmental agreement (Brechin Reference Brechin2003) or nuclear weapons and power (Jenkins‐Smith et al. Reference Jenkins‐Smith, Mitchell and Herron2004).Footnote 1 Just as focusing on a single country limits the generalisability of results, so too does focusing on a limited set of specific policy issues.

Following the terminology of Hurwitz and Peffley (Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1987), our analyses reveal the outlooks or ‘postures’ that citizens possess that inform their view of how their nation should behave in the international arena. These broad postures are in many respects more important than attitudes on specific issues, which change over time. It is these postures that shape views on the specific foreign policy issues of the day (Hurwitz & Peffley Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1987). Cross‐national comparisons of foreign policy postures may illuminate similarities and differences in the constraints leaders face when foreign policy crises emerge. Drawing valid comparisons, however, requires careful attention to measurement and equivalence, which is a central feature of our analyses.

In this article, we bring new data to bear on two important questions: (1) how do mass publics structure their attitudes toward foreign affairs; and (2) how similar or different are these structures across our four cases? The answers we provide are novel in two respects. First, we argue that there are important concepts distinct from militant internationalism and cooperative internationalism in publics’ collective minds. The MI/CI framework has endured for a reason, but it is reasonable to assess whether these two dimensions offer a complete account of foreign policy preferences. To be clear, we find unambiguous support confirming the existence of both militant and cooperative internationalisms. We also find remarkably similar structure across all four countries, but the empirical evidence makes it abundantly clear that the MI and CI dimensions tell an incomplete story about foreign policy attitudes. We thus argue for a more multifaceted (and multifactor) view of how mass publics structure their attitudes toward international politics.

So, what dimensions help complete the picture? We find two. In accord with other recent scholarship (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2013; Rathbun Reference Rathbun2007), we find an isolationist posture that is distinct from MI and CI. This finding is important because it means that isolationism is not simply the joint negation of the latter two concepts (Braumoeller Reference Braumoeller2010; Urbatsch Reference Urbatsch2010). Further, our data reveal that ‘liberal internationalism’ (often used synonymously with cooperative internationalism) may be better explained as two separate (but related) constructs. One captures support for international institutions and cooperation – and deserves to retain the name cooperative internationalism. The second ‘liberal internationalism’ dimension reflects support for redistributive policies like foreign aid – and perhaps reflects attitudes toward global justice.

Our second novel contribution is a direct assessment of the cross‐national equivalence of foreign policy attitude constructs. As noted by King et al. (Reference King2004), the cross‐national equivalence of survey‐based attitudinal measures often is assumed rather than tested explicitly in comparative research. Recent research has thus sought to test the cross‐national (or cross‐group) measurement equivalence (or measurement invariance) of various key concepts in political science, such as democracy (Ariely & Davidov Reference Ariely and Davidov2011), the welfare state (Stegmueller Reference Stegmueller2011), and national identity (Davidov Reference Davidov2008, Reference Davidov2011). We are similarly motivated to evaluate whether broad attitudes toward foreign policy are structured equivalently on either side of the North Atlantic. Finding measurement equivalence greatly simplifies comparison of foreign policy attitudes across advanced democracies.

We structure the article as follows. First, we briefly review the literature on foreign policy attitudes while pointing out some of its limitations. Second, we introduce the American, British, French and German survey data that underpin our empirical analyses. Third, we motivate the statistical methods we employ – namely exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) (Asparouhov & Muthén Reference Asparouhov and Muthén2009) – as a means to evaluate factor structure and measurement equivalence (or measurement invariance) across the four countries studied. Fourth, we describe the results of the data analysis for the four countries, drawing attention to both the similarity in the structure of attitudes across the different country contexts examined while also noting differences in country‐level factor scores. We conclude by noting areas for future research.

The structure of foreign policy attitudes: Competing approaches

The earliest influential model of the structure of foreign policy attitudes argued that there was in fact very little structure to speak of underlying mass public opinion on foreign policy (Almond Reference Almond1960; Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964). This view was gradually replaced by studies of American public opinion from the 1950s to the 1970s claiming that the public held a relatively coherent set of attitudes relating to engagement with the world, both militarily and economically, and were seen as falling somewhere on a single internationalist–isolationist continuum (e.g., McClosky Reference McClosky and Rosenau1967; Russett Reference Russett1960; Sniderman & Citrin Reference Sniderman and Citrin1971).

This view of a single internationalism–isolationism dimension came to be replaced in the 1980s as a result of a series of seminal publications by Wittkopf, whose central argument was that in the wake of the Vietnam War, American public opinion became bifurcated on foreign policy issues. The issue was no longer whether but how the United States ought to engage with the world. Wittkopf (Reference Wittkopf1981) relied on factor analyses of survey data collected by the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations (CCFR) to advance the view that ‘two faces’ of internationalism characterised American public opinion toward foreign policy: attitudes toward the use of the military abroad (‘militant internationalism’) and attitudes toward non‐military engagement (‘cooperative internationalism’).

Wittkopf subsequently reproduced the two‐factor MI/CI model using different data (Wittkopf Reference Wittkopf1986, Reference Wittkopf1990, Reference Wittkopf1994; Wittkopf & Maggiotto Reference Wittkopf and Maggiotto1982). The same factor structure was observed in samples of elites, implying that elites structure their views in the same manner as the public, though this was not to say that elites’ foreign policy beliefs exhibited the same distribution (Holsti & Rosenau Reference Holsti and Rosenau1986, Reference Holsti and Rosenau1990, Reference Holsti and Rosenau1993; Wittkopf & Maggiotto Reference Wittkopf and Maggiotto1983). Similar factor structures were also obtained outside the American context in other industrialised states, including the United Kingdom (Reifler et al. Reference Reifler, Scotto and Clarke2011) and Sweden (Bjereld & Ekengren Reference Bjereld and Ekengren1999).

In contrast to the ‘horizontal’ organisation of Wittkopf's two factors, Hurwitz and Peffley (Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1987) advanced a model of ‘vertical’ constraint whereby more specific policy attitudes are structured (or ‘constrained’) by broader foreign policy postures, which are in turn structured by yet broader core political values. Recent work has reconfirmed the insight that core values inform policy preferences, while also demonstrating the status of isolationist sentiment as a factor distinct from different forms of internationalism (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2013; Rathbun et al. Reference Rathbun2016). This recent work has ‘squared the circle’, bringing together core insights of Wittkopf and others with those of Hurwitz and Peffley: the basic MI/CI framework serves as a useful account of foreign policy postures informed by underlying core values. Consequently, the Wittkopf–Holsti and Rosenau MI/CI framework retains its primacy in the foreign policy attitudes literature. Indeed, it has been described as the ‘gold standard’ of models of foreign policy attitudes (Nincic & Ramos Reference Nincic and Ramos2010: 122).Footnote 2 This, however, raises two questions. First, while there is a general persistence of MI and CI factors, are these the only regularly observed factors? And second, should the MI/CI framework be seen as the gold standard theoretical account of American attitudes, or for foreign policy attitudes more broadly?

Data

To answer these questions, we draw on original survey data collected in the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany. Country case selection was motivated by the fact that these four countries are the top four Western democracies in the amount of money spent on national defence. All four have the economic and military resources to be active in world affairs. As NATO members, they also have similar security concerns and commitments. At the same time, there is variation in their political institutions: the United States is a presidential system, France is a semi‐presidential one, and the United Kingdom and Germany are parliamentary democracies. While such institutional differences are not our primary concern, it is important to note that more direct comparisons of attitudes at the mass level may help isolate the effect of institutions on observed foreign policy differences. There are also notable differences in national experiences in war and conflict. France, the United Kingdom and the United States share significant experiences in counter‐insurgency campaigns, some of which have incurred substantial casualties and substantial domestic opposition. German strategic culture, perhaps in response to defeats in the First and Second World Wars, eschews high‐intensity combat (Rynning Reference Rynning2003). How these different legacies shape foreign policy attitudes is an important question that we hope future research will address.

In approaching the design of these original surveys, our intent was to design instruments that would allow for the possibility of complex, multidimensional structures that varied significantly across countries. More specifically, we included multiple questions designed to capture each of the following potentially distinct attitudes about international affairs: militarism, multilateralism, isolationism, unilateralism, humanitarianism, egalitarianism and pacifism.Footnote 3 After preliminary analyses, we identified 14 indicators for analysis with at least one item from each of the concepts other than pacifism. Our expectations were informed by prior work identifying separate dimensions that capture attitudes about the exercise of military power, on the one hand, and cooperative engagement with other states and intergovernmental organisations, on the other (Mader Reference Mader2015; Reifler et al. Reference Reifler, Scotto and Clarke2011; Wittkopf Reference Wittkopf1986). While some attitudinal models (e.g., that of Wittkopf) see isolationism as the absence of military and non‐military engagement, recent empirical research identifies an isolationism factor distinct from the other two factors (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2013; Rathbun Reference Rathbun2007). Isolationist thought is conventionally viewed as an American affliction, though segments of the public in many democratic states express an aversion toward involvement beyond their borders (e.g., Mader & Pötzschke Reference Mader and Pötzschke2014).

While the concepts of ‘militant internationalism’, ‘cooperative internationalism’ and ‘isolationism’ are well‐established, some of our other concepts may require more explanation. One might believe that cooperation is desirable, but their country needs to be willing and able to act alone if the situation warrants such action. This sentiment of unilateralism is important to probe in light of periodic unilateral actions by the United States (Skidmore Reference Skidmore2005). In addition to the United States, France has a history of acting distinctly – most prominently with its (temporary) withdrawal from NATO in the 1960s. Large segments of the British public and their elected politicians also express a desire for Britain to engage with the outside world in ways that differ from prevailing policy‐making consensus (e.g., with Brexit). Only in Germany does unilateralist thought appear muted. Given the economic crisis and the German position within the Eurozone, this too may change (see Le Gloannec Reference Gloannec2004). The fact that circumstances surrounding the use of force or the exercise of economic statecraft may bear on public views of unilateralism in foreign policy underscore the need for its cross‐national validation.

Finally, there is a renewed emphasis on the need for developed nations to help the world's poor through foreign aid. The UN Millennium Project's benchmark of at least 0.7 per cent of Gross National Income (GNI) spent on overseas assistance regularly makes headlines. We included four potential global justice indicators that represent both humanitarian and egalitarian constructs (as per Feldman & Steenbergen Reference Feldman and Steenbergen2001) that we think capture public support for more redistributive international policies.

Survey data collection was undertaken by YouGov in November 2011 in the United States and United Kingdom, in May 2014 in France and in October 2014 in Germany. YouGov's approach to survey sampling involves using a matching algorithm designed to draw online samples from opt‐in panels that approximate probability samples (Rivers Reference Rivers2006). Selected respondents are matched on demographic factors (gender, age, education and region) and the final achieved samples then weighted to the characteristics of the American, British, French and German adult populations. The sizes of our samples (excluding cases with missing data across all foreign policy survey items) are: 2,824 (United States), 2,736 (United Kingdom), 5,930 (France) and 2,551 (Germany).Footnote 4

Tables 1 and 2 delineate the indicators by hypothesised postures and the percentage answering ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to each statement. (The full distributions appear in the Online Appendix). A number of similarities and differences emerge from these tables. Responses to the hypothesised militarism indicators suggest that the German public is much less inclined toward maintaining and displaying a readiness to use military force than their French, British and American counterparts. A majority of French and British respondents view maintaining a tough posture as important, while Americans and Germans seem more willing to listen before acting. Respondents in all countries, however, are amenable to diplomatic solutions to crises before going to war.

Table 1. Indicators of traditional dimensions of foreign policy attitudes

Note: Questions in italics are reverse‐coded. Percentages are weighted.

Table 2. Indicators of new dimensions of foreign policy attitudes

Note: Questions in italics are reverse‐coded. Percentages are weighted.

Responses to the three indicators we hypothesise to be reflective of CI provide varied results. One curiosity is that members of the American public are most receptive to the idea that their country should consider views of allies. At the same time, Americans and the French appear more critical when asked about working through the United Nations or when asked about building a broader consensus (without the mention of allies). The cross‐national variation in response patterns to the proposed CI indicators validates the decision to use multiple indicators for a given foreign policy posture.

The French public stands out in its level of agreement with the three proposed isolationism indicators. A majority of French respondents agree that international involvement is not worth it if the well‐being and happiness of the citizenry are sacrificed. A plurality of French respondents also expressed agreement when presented with statements asking whether it is best for nations to ‘stay out’ and/or ‘avoid involvement’ in foreign relations. Americans and Britons are much more inclined toward engagement than the French, with Germans taking a middle ground.

As for willingness to act unilaterally, Britons stand out as most apt to wish to do things their own way. These questions may tap into British ambivalence toward the European Union and/or regret following America into Iraq. Germans are second only to the British in wanting to chart their own course or ‘go at it alone’, but are not as prone as Americans and the French to believing they are getting pushed around by international organisations.

Responses to the last set of indicators show that there is little support for wealth redistribution across borders. Close to 1 in 4 German respondents and 1 in 5 French respondents express willingness to share their country's wealth with others, but just over 1 in 10 Americans and Britons express the same opinion. Majorities of the British, American and French publics agree that their country does ‘enough to help the world's poor’, as does a plurality of the German public.

Methods

Given the two linked goals of our research – the dimensionality of foreign policy attitudes among mass publics and the cross‐national equivalence of these dimensions – we analyse a series of exploratory structural equation models (ESEMs). ESEM is an extension of exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) (Asparouhov & Muthén Reference Asparouhov and Muthén2009; Marsh et al. Reference Marsh2014). Factors in ESEM are analogous to those in EFA in that all items are allowed to load on all factors; this is appropriate when expectations regarding the factor structure (i.e., the number of factors and which items ought to be associated with which factors) are not given by existing theory. ESEM thus represents a relaxation of the assumption of ‘simple structure’ (items loading on only one factor, and no cross‐loadings) typically characteristic of applications of CFA, and one that is ‘more closely aligned with reality, reflecting more limited measurement knowledge of the researcher or a more complex measurement structure’ (Asparouhov & Muthén Reference Asparouhov and Muthén2009: 399). ESEM also allows for factor loadings, means and intercepts to be alternatively constrained to be equal or free to vary – all features of CFA and SEM.

In ESEM, the question of how many factors underlie a set of data is framed in terms of the minimum number of factors necessary to achieve good overall fit to the data. This involves testing alternative models (e.g., one‐, two‐, three‐, four‐factor models and so on) against the same data and evaluating them on the basis of overall model fit using the fit indices commonly used in SEM (Preacher et al. Reference Preacher2013). By emphasising the minimum number of factors to achieve good fit, the model selection approach seeks to strike a balance between not overfitting the data at hand while also not ignoring important complexity and nuance – that is, specifying a model structure that is no more complex than necessary and is amenable to cross‐validation using different data (Cudeck & Henly Reference Cudeck and Henly1991; Preacher et al. Reference Preacher2013).

To be clear, we care more about the content of the factors than their exact number. Still, determining the appropriate number of factors is an essential step in understanding what the data reveal about the content and structure of foreign policy thinking in these four countries. To determine the correct number of factors, we test a series of ESEMs with 1–5 factors in three separate sets of analyses: in each country separately, with a pooled dataset with all four countries while allowing factor loadings and item thresholds to vary across countries (representing configural equivalence, described below), and again with a four‐country pooled dataset constraining factor loadings and thresholds to be equal across all four countries (representing scalar equivalence, also described below). The goal of these analyses is to find the minimum number of factors that describe the dimensionality of the data. Once the number of factors is ascertained, we then turn to the question of their equivalence across countries.

In assessing cross‐national equivalence/invariance, the literature on cross‐national comparisons distinguishes between different, progressively more stringent levels of equivalence. Those relevant to our analyses are configural equivalence and scalar equivalence. Configural equivalence requires only that ‘factor structures are equal across groups: The same configurations of salient and non‐salient factor loadings should be found in all groups’ (Davidov et al. Reference Davidov2014). Furthermore, no constraints are imposed on the factor loadings: they are allowed to vary across countries (Steenkamp & Baumgartner Reference Steenkamp and Baumgartner1998). In the case of scalar equivalence, the model is further constrained so that item intercepts (or thresholds) are equal across groups, in addition to constraining factor loadings to be equal. Scalar equivalence is necessary for making meaningful comparisons of latent variable means across groups (Davidov et al. Reference Davidov2014; Stegmueller Reference Stegmueller2011). Scalar equivalence thus indicates that ‘cross‐national differences in the means of the observed items are due to differences in the means of the underlying construct(s)’ (Steenkamp & Baumgartner Reference Steenkamp and Baumgartner1998).

The dimensionality of foreign policy attitudes

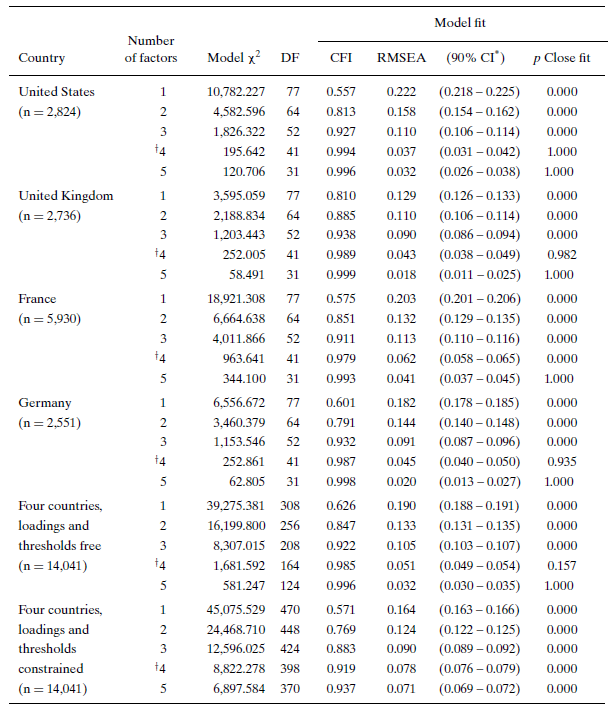

Before turning to a discussion of the substantive meaning of the factor structure we identify, we first discuss the process of choosing the appropriate number of factors. In examining models with one through five factors, the results point clearly toward a four‐factor model. Separate analyses by country and analyses of the pooled data with specifications for either configural equivalence or scalar equivalence tell the same story (see Table 3). Examining overall model fit, all of the models fit poorly based on the model Chi2 tests – though experienced latent variable modelers recognise that like all Chi2 tests, the model Chi2 statistics are sensitive to sample size and often indicate misfit in large samples (Kline Reference Kline2015). Given our large sample sizes, we turn to other, more frequently used measures of model fit offered in the SEM literature – in particular the RMSEA fit statistics emphasised by Preacher et al. (Reference Preacher2013) in their approach to selecting factor models.Footnote 5

Table 3. ESEM model summary statistics

Notes: †Selected model; *CI = confidence interval.

Looking at the approximate fit indices for the four‐country models, a noteworthy result is the poor model fit for the two‐factor models. The RMSEA values of 0.133 for the unconstrained (configural equivalence) model and 0.124 for the constrained (scalar equivalence) model are well above the suggested threshold of 0.08, indicating lack of fit (Browne & Cudeck Reference Browne and Cudeck1992; Hu & Bentler Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Similarly, the two‐factor models’ values for the comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.847 for the unconstrained model and 0.769 for the constrained model are again well below the threshold of 0.90 for acceptable model fit. Country‐specific values of the RMSEA and CFI fit statistics similarly indicate lack of fit. By all of these measures, a two‐factor model of foreign policy attitudes fit the data poorly.

A more complex model is needed, but exactly how much more complex should it be? Model fit improves appreciably when three‐factor models are specified, though they still fail to meet the conventional RMSEA and CFI thresholds for good fit to the data. The CFI of 0.922 for the four‐country unconstrained three‐factor model is acceptable, but the RMSEA of 0.105 indicates poor fit. With the constrained three‐factor model, both the RMSEA (0.090) and CFI (0.883) indicate lack of fit. Acceptable fit is achieved in all four countries – and with the four‐country pooled data – only with the specification of a four‐factor model. With four factors, the RMSEA and CFI statistics are 0.051 and 0.985, respectively, for the unconstrained model; they are 0.078 and 0.919, respectively, for the constrained model. Similar results are obtained for the country‐specific four‐factor models. Further, model fit statistics do not improve appreciably with the specification of a five‐factor model. This points to a four‐factor model as the solution that best represents the structure of foreign policy attitudes in the United States, United Kingdom, France and Germany.Footnote 6

The content and cross‐national equivalence of foreign policy attitudes

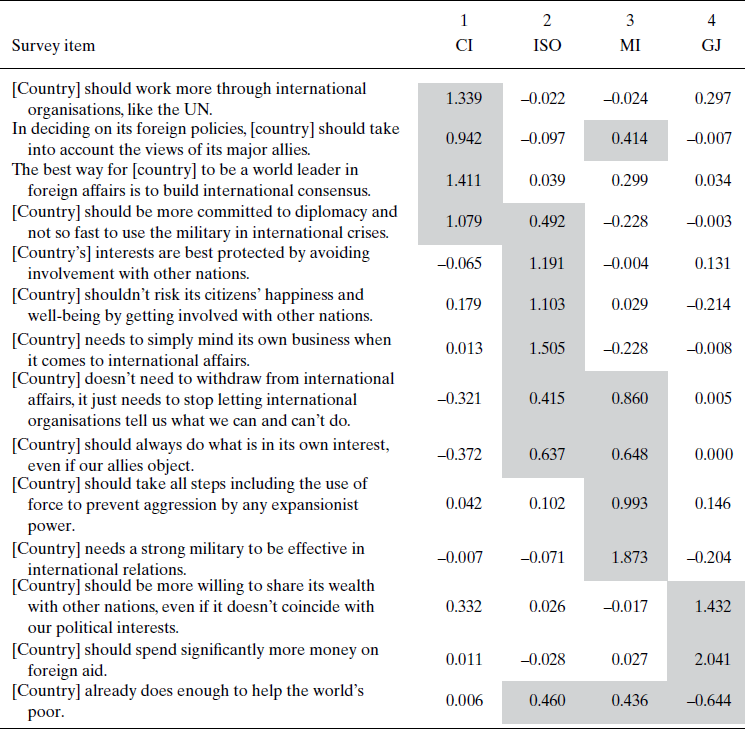

What of the content of these four factors? Examining the factor loadings from the unconstrained four‐factor model, there are clear similarities between the four countries (see the Online Appendix). The first factor that emerges in all analyses resembles Wittkopf's and Holsti and Rosenau's cooperative internationalism. This factor centres on support for working through international organisations such as the United Nations, working with allies, the pursuit of global leadership through building international consensus, and an emphasis on diplomacy and the pursuit of peace over the use of force.

The second dimension is straightforward isolationist sentiment. Items reflecting ideas such as avoiding involvement with other countries, refusal to risk one's citizens’ well‐being through international entanglements and minding one's own business load strongly on this factor in all four countries. Weaker secondary loadings on this factor are present for the items measuring willingness to disregard international organisations and the views of allies, and agreement with the idea that one's country already does enough to help the world's poor (and by extension, should not do more, or possibly do less). These results reconfirm findings from recent work on foreign policy attitudes that finds that isolationism constitutes a distinct posture in mass public opinion (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2013; Rathbun Reference Rathbun2007). Isolationism is not equated to jointly scoring low on MI and CI (cf. Wittkopf Reference Wittkopf1981, Reference Wittkopf1990).

The third dimension (fourth in the United Kingdom) clearly resembles Wittkopf's classic MI factor. This factor centres on the projection of military power abroad, including support for the use of force to prevent aggression and maintaining a strong military. This factor also includes a unilateralist, go‐it‐alone tendency in the American and French cases, with loadings for items capturing support for disregarding international organisations and allies when interests dictate. These loadings are weaker in the British case, and absent in the German case (these items are more closely tied to the isolationism factor in the United Kingdom and Germany).

The last dimension (third in the United Kingdom) clearly speaks to the redistribution of wealth across borders and improving the condition of the global poor. Items capturing agreement with sharing wealth with other countries and spending significantly more on foreign aid load strongly on this factor, as does disagreement with the idea that one's country does enough to help the world's poor (i.e., a negative loading). In this light, it might reasonably be labeled a ‘global justice’ factor in that it emphasises global egalitarian aspirations and aligns with the core arguments advanced in the literature on global distributive justice (Beitz Reference Beitz1999; Rawls Reference Rawls1999; Tan Reference Tan2004).

Overall, the patterns of factor loadings across the four countries are broadly similar, with the conclusion being that the data exhibit (at least) configural equivalence. Not only do four factors emerge from the data, the substantive meaning of each factor is the same in each country context. Still, scalar equivalence needs to be established in order to make direct comparisons of country‐level factor means. The answer to this question is provided by the model fit results for the four‐country, four‐factor constrained model in Table 3. The RMSEA statistic for this model is 0.078, with the 90 per cent confidence interval being 0.076 to 0.079 – just within the conventional range for reasonable model fit – and the CFI statistic is 0.919, again indicating reasonable fit. These results suggest worse fit than the model in which loadings and thresholds are free to vary (RMSEA is 0.051, and CFI is 0.985), but as a more restrictive model where loadings and thresholds are held equal across countries, this is to be expected. It remains the case that model fit does not worsen to the degree that it would lead us to reject the constrained model. The conclusion, then, is that the data exhibit scalar equivalence. The structure of the data in all four countries can thus be represented using the common set of factor loadings presented in Table 4.

Table 4. ESEM unstandardised factor loadings, 4‐factor solution, constrained model

Notes: Shaded cells indicate salient factor loadings (≥ |0.400|). CI = cooperative internationalism; ISO = isolationism; MI = militant internationalism; GJ = global justice.

The substance of foreign policy attitudes in transatlantic perspective

What, then, can we say about comparisons of the foreign policy attitudes of the American, British, French and German publics in terms of their orientations toward cooperative internationalism, isolationism, militant internationalism and global justice? The answer to this question comes from the factor means from the four‐country, four‐factor constrained (scalar equivalent) model. Since factor scores have no natural scale, factor score comparisons are made by fixing the factor means for one group (in this case, the United States) to zero and then making pairwise comparisons between other groups and this reference group (Davidov et al. Reference Davidov, Davidov, Schmidt and Billiet2011; Stegmueller Reference Stegmueller2011).

These scores provide several findings of note (see Table 5). First, there is little in the way of cross‐national differences in CI: there are no significant differences between the United States and either the United Kingdom or France; Germany scores slightly higher than the United States. Interestingly, the United Kingdom, France and Germany score higher on isolationism than the United States. While isolationism has been a recurring theme in the history of American foreign policy (and the study of American foreign policy attitudes), these results indicate that the American public is not, in cross‐national perspective, especially isolationist (Braumoeller Reference Braumoeller2010; Kertzer Reference Kertzer2013; Nincic Reference Nincic1997). The United Kingdom, France and Germany also score lower on MI than the United States. The differences between the United Kingdom, France and the United States are modest, while German public opinion is notably anti‐militarist compared to the United States – a finding not likely to surprise those familiar with postwar German foreign policy (Berger Reference Berger1998). Finally, the United Kingdom, France and Germany in turn score progressively higher on the global justice factor than the United States. This finding is interesting in light of the European countries’ higher levels of official development assistance as a proportion of GNI, and also in light of previous aggregate‐level findings that countries with higher levels of domestic redistribution are generally less favourable toward global redistribution (Noël & Thérien Reference Noël and Thérien2002). An explanation for these cross‐national differences in mean factor scores may be found in the previously noted differences in political institutions, respective histories of foreign policy, and national strategic cultures. Indeed, such cross‐national difference in foreign policy attitudes is a topic requiring further investigation and the development of additional theory.

Table 5. Unstandardised factor means, 4‐factor solution, constrained model, by country

Notes: *p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.001. Factor means for the United States are fixed to zero. Significance tests are two‐tailed Z tests comparing country factor means to the United States. Tests are not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Discussion and conclusion

Our intention in this article has been to bring new techniques and new data to the decades‐old question of how mass publics structure their attitudes toward foreign policy. Drawing on recent survey data from four principal NATO member states – the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany – we have argued for a more multifaceted (and multifactor) framework for understanding how publics organise their views of foreign policy. Though the classic MI and CI factors remain important, a rigorous assessment of model fit in analysing series of ESEMs shows that they do not, on their own, adequately describe the patterns in our data. Subsequent scholarship has argued for isolationism as an important distinct concept at the level of mass opinion (Chittick et al. Reference Chittick, Billingsley and Travis1995; Kertzer Reference Kertzer2013; Rathbun Reference Rathbun2007) – an argument supported by our findings here not just for the United States, but our other three cases as well.

Our results identify an additional concept important to understanding foreign policy attitudes – a factor we call ‘global justice’ – that captures support for more international redistribution. These notions of global justice represent a rich literature within international political theory that has, to date, been relatively under‐explored within political behaviour and the literature on foreign policy attitudes (though see Bayram Reference Bayram2017; Noël & Thérien Reference Noël and Thérien2002; Spencer & Lindstrom Reference Henson and Lindstrom2013). This raises an important question: Why do we observe separate constructs for CI and global justice when early analyses (i.e., by Wittkopf) did not?Footnote 7 The answer here is interesting: our results finding that redistributive preferences constitute a distinct construct separate from cooperative internationalism actually is consistent with prior work.

In hindsight, we can see that some of the early work privileged the parsimony of a two‐factor model while discarding concepts outside the MI/CI framework. Analysing the 1974 CCFR data, Maggiotto and Wittkopf (Reference Maggiotto and Wittkopf1981: 608) note clearly ‘that the aid scales did not load with the traditional foreign policy scales [which] suggests that attitudes towards foreign aid are not intimately associated with other types of internationalist attitudes’. Wittkopf's (Reference Wittkopf1990: 23) subsequent analyses of data from the 1978 and 1982 CCFR studies also show that responses to foreign aid questions cluster on their own to ‘comprise quite distinctive orientations towards international involvement’.

In the Online Appendix, we employ modern estimation techniques to successfully replicate Mandelbaum and Schneider's (Reference Mandelbaum and Schneider1978: 41–42) factor analysis of just 1974 CCFR questions pertaining to favouring or opposing a set of broad foreign policy goals that yields two dimensions they label ‘Co‐operative and Competitive Internationalism’. We extend this analysis to show a factor analysis of the goals questions with the addition of a single foreign aid question. Doing so yields results where a three‐factor solution is superior to a two‐factor solution. Importantly, responses to the foreign aid question load on a dimension with responses to the questions pertaining to the goals of ‘combatting world hunger’ and ‘helping improving the standard of living elsewhere’. Thus, orientations toward global justice are not new; they simply form a previously under‐appreciated dimension of public attitudes toward foreign policy. Further, differentiating clearly between cooperative and redistributive internationalism is important in understanding how domestic opinion imposes constraints on the foreign policies governments pursue. While public sentiment often opposes foreign assistance (while also substantially overestimating how much money is spent on aid), this does not imply public opposition to international cooperation.

Taken as a whole, the results in this article make key contributions. The first main finding is that mass publics are more nuanced in how they think about foreign policy than is usually acknowledged. Moving forward, research on foreign policy attitudes should therefore endeavour to measure orientations toward isolationism and global justice in addition to the familiar concepts of militant and cooperative internationalism. Failure to do so will yield an incomplete map of how mass publics view international politics. The second main finding is that the four factors identified are equivalent across the countries studied. There is, therefore, a firm statistical basis for cross‐national comparisons of foreign policy attitudes. We might conclude by saying that we have four factors, and they travel across the North Atlantic.

These findings should nevertheless be viewed within the context of the data analysed. It is commonplace to note that factor analytic results are, to a degree, contingent upon what data one submits to such procedures. As we discuss above, we started with an unusually large target of possible constructs. Nevertheless, there are still gaps in what we capture. The foreign policy survey items we analyse do not contain any items dealing directly with trade, or many other aspects of international economic relations (though see Kleinberg & Fordham Reference Kleinberg and Fordham2010). Consequently, there may be other foreign policy‐related concepts in mass publics’ collective minds that we have not uncovered here. Future research should endeavour to uncover such factors.

The results should also be understood as depicting the structure of foreign policy attitudes among the publics of four states, three of whom are nuclear‐armed states, three of whom are – as of this writing – EU member states, and all of whom are NATO member states. In this sense, our study remains focused on advanced industrialised democracies with broad similarities to the well‐studied American case. Our finding of scalar equivalence (or invariance) in foreign policy attitudes may be a function of the countries studied. Countries with vastly different histories, domestic institutions, capabilities or strategic contexts may be different in important ways. We are hopeful that the techniques we present for testing equivalence (combined with making our data available) will assist others in directly comparing foreign policy beyond the four cases we examine.

Our project here can also be viewed from a methodological perspective as a demonstration of the utility of modern statistical techniques, such as ESEM, for evaluating both the dimensionality and cross‐national equivalence (or invariance) of social science concepts. The landscape of mass public opinion is often complex, as is the content of survey‐based measures. By relaxing the sometimes untenable assumption of ‘simple structure’ while also providing a flexible and powerful statistical framework, ESEM offers social scientists a set of tools to model such complexity.

Finally, it is worth noting that our project here has been a largely inductive exercise in measurement. Future work should obviously endeavour to expand the number of countries analysed, and also provide a more theoretically developed account of why we observe country‐level differences on the foreign policy dimensions. At the individual level, further research should also complete the Hurwitz and Peffley (Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1987) vertical constraint model in a systematic comparative fashion, with attention paid both to more abstract values above that shape these foreign policy postures (Goren et al. Reference Goren2016; Kertzer et al. Reference Kertzer2014; Rathbun et al. Reference Rathbun2016), and to how these postures affect more specific policy attitudes across multiple countries and contexts. All of these lines of inquiry will deepen our knowledge of how mass publics organise their attitudes toward foreign policy. Our aim here has been to lay the groundwork for exactly these types of inquiries.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2015 conference of the Midwest Association for Public Opinion Research in Chicago, Illinois; the 2016 conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research in Austin, Texas; and the 2016 conference of the Canadian Political Science Association in Calgary, Alberta. We are grateful for the comments and suggestions offered by the anonymous EJPR reviewers, Jason Roy, Harald Schoen, Matthias Mader and especially the late Allen McCutcheon. Via relaxed evening conversations at the Essex Summer School, Peter Schmidt was the source of many insightful discussions of the ESEM techniques employed in this article.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Appendix 1: Percent Response Distributions for All Indicators

Appendix 2: ESEM Unstandardized Factor Loadings, 4‐Factor Solution, Unconstrained Model, by Country

Appendix 3: Unstandardized Factor Correlations, 4‐Factor Solution, Constrained Model, by country

Appendix 4: Replication of Mandelbaum and Schneider (1979: 41‐42)

Appendix 5: Two Factor Extension of Mandelbaum and Schneider (1979: 41‐42), with Inclusion of Foreign Aid Question

Appendix 6: Three Factor Extension of Mandelbaum and Schneider (1979: 41‐42), with Inclusion of Foreign Aid Question