Introduction

Research ethics consultation services (RECS) provide advice to a broad array of interested parties, including investigators and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) [Reference Sharp, Taylor and Brinich1,Reference Porter, Danis, Taylor, Cho and Wilfond2]. In general, RECS provide ethical guidance when those engaged in the conduct and review of research face challenges and/or novel ethical issues before, during, or after the conduct of human subject research [Reference Porter, Danis, Taylor, Cho and Wilfond2–Reference Taylor, Porter and Talati Paquette3]. RECS are a flexible resource that can help mediate conflicts as well as overcome barriers to research by both one-time and sustained engagement with various parties.

RECS have existed since the late 1980s [Reference Taylor, Porter, Sullivan and McCormick4]. In 2005, the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS; previously National Center for Research Resources) created the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA). Prospective grantees were required to include efforts to build capacity in research ethics in their CTSA applications [Reference Taylor, Porter, Sullivan and McCormick4]. In response, multiple institutions either directed CTSA funds to their already established RECS or proposed establishing RECS with the funds [Reference McCormick, Sharp and Ottenberg5]. In subsequent requests for proposals, NCATS dropped the requirement for research ethics programming [Reference Taylor, Porter, Sullivan and McCormick4].

As members of the Clinical Research Ethics Consultation Collaborative (CRECC) and based on a survey of RECS conducted in 2020, we were aware that losing the NCATS funding had an impact on RECS and that many RECS continue to exist and continue to provide consultations [Reference Taylor, Porter, Sullivan and McCormick4]. We decided it would be helpful to the field to find out about the key barriers and facilitators of success for RECS.

Materials and methods

Sample

In preparation for a previous study, a member of the study team (HAT) had compiled a list of 52 US-based RECS and their directors [Reference Taylor, Porter, Sullivan and McCormick4]. This list was cross-referenced with a publicly available list of all institutions currently receiving funds from the CTSA including the names of the institutional principal investigators and/or director of the affiliated RECS (https://ccos-cc.ctsa.io/resources/hub-directory). The combined list included a total of 55 RECS directors.

Recruitment

As we aimed to perform 20 interviews, we purposively sampled 20 RECS services from the combined list of RECS directors. When a RECS service director did not respond after two emails or declined participation, we would select another similar service from the list of institutions described above. We used purposeful sampling to ensure variety in the type of institution and consultation service. For example, we sampled RECS that had the reputation of being a high-volume consultation service, as well as those that had a lower volume of consults. We also ensured that we sampled both public and private institutions. The email described the purpose of the study and requested their or a designee’s participation in an in-depth interview. The email included key elements of informed consent and how to indicate their willingness to participate. Potential participants were informed that they would receive a $25 gift card for participating in the interview.

Interview guide

The interview guide was informed by the relevant literature and based on the knowledge of the study team [Reference Sharp, Taylor and Brinich1–Reference Taylor, Porter, Sullivan and McCormick4] (attached appendix). Key domains in the interview guide included primary function of the local RECS, major accomplishments of the service, institutional support of the service, and barriers and facilitators faced by the service and future expectations for the service.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted via video calls. Participants who scheduled an interview were sent a copy of a disclosure statement in advance. Their receipt of the form and a review of the key points were reviewed prior to the start of the interview. Interviews were completed by SAM and JBM. The video and audio of the interviews were recorded, and a transcript was generated by Zoom. The initial transcript created by Zoom was reviewed, and the missing narrative was inserted by the interviewer. The transcript was verified by one of the interviewers (i.e., the recording was played, and transcript was edited as needed). During the process of verification, transcripts were assigned a unique number, and all identifiable information (e.g., names, institution) was redacted for analysis. HAT did not have access to identifiable transcripts. The numbers reported after each quotation refer to the interview from which the quote was excerpted.

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis was performed using an inductive technique. This allows for both deductive and inductive codes to be applied to the data [Reference Timmermans and Tavory6]. Transcripts were open coded, and a preliminary codebook was developed based on the interview guide and themes that emerged from the data. For example, we specifically coded for barriers and facilitators of RECS (deductive coding), while the codes regarding “involvement with community-engaged research” emerged from the data (inductive coding). A summary was created for each interview, and this information was used to further refine the codebook. All transcripts were coded electronically in NVivo 14. [7] by SAM or JBM. In order to confirm that they were applying the codes consistently, they (SAM and JBM both coded a random sample of transcripts, and their discrepancies were discussed and resolved. NVivo was used to create output for each primary code, and more in-depth analysis was conducted.

Results

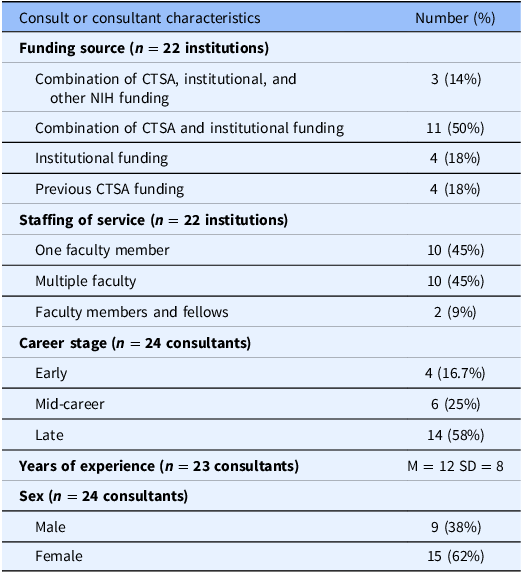

We interviewed 22 research ethics consultants from 20 institutions (2 interviews included 2 participants). Respondents worked at a variety of institutions including public and private academic medical centers and public research hospitals. They had various levels of experience with research ethics with some conducting consultations for only 2 years and others having more than 20 years of experience. See Table 1 for more detailed information about participants’ characteristics.

Table 1. Demographics

% = percentage; CTSA = Clinical and Translational Science Award; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

Overall, respondents discussed the purpose and goals of their service, barriers and facilitators that affected their service, and accomplishments of their service. Some provided new strategies that they were implementing to ensure that their service stayed relevant and fundable.

Purpose and goals of RECS

Overall, respondents viewed the goal of their service as to provide an opportunity for people to “deliberate and think through ethical questions” (018) in a way that facilitated the conduct of ethical and responsible research. Many stressed that the purpose of their service was not to stop research but rather to ensure that research promoted good science and the “well-being of people” (002).

I think ultimately for me, the biggest thing is, “does the consult help identify issues that are modifiable?” And then, “are those issues modified in the grant in a way that helps to make the research more ethical and more equitable?” (007)

I think we’re trying to provide a forum for people…whether this is a researcher or whether it’s the IRB. …It’s really just for them to reflect on with our guidance with whatever issue that they’re struggling with. (005)

While RECS often defined their scope of work differently, all were committed to ensuring that researchers had a place to ask questions, think through their research’s purpose and design, and receive recommendations that were consistent with relevant regulations and the latest perspectives in research ethics.

Respondents agreed that RECS should provide guidance on issues not covered by their local IRB, the body responsible for assuring that research complies with the federal regulations [8,9]. They emphasized that their service should not be a replacement for IRB review. Instead, their analysis often assisted researchers in interpreting regulations, responding to IRB reviews, and ensuring ethical design of studies where there was a gap in the regulations. Some respondents reported they were also involved in creating institutional-based policies that helped clarify or operationalize a regulatory requirement.

…we would assist [institutional] researchers in making their research more ethical by addressing things that were not addressed by other regulatory requirements like IRB requirements. Some of our consults have dealt with research that doesn’t have any human subjects component to it; so, it’s not solely clinical research ethics. The other thing that we have done is to develop best practices for new areas of research. We’ve published on the basis of some of the consults that go beyond individual research protocols. (003)

For many respondents’ services, their involvement in research ethics programming for their institution included teaching and advising on matters related to responsible conduct of research (RCR). RCR topics like authorship and conflict of interest were also viewed as important matters for some consultants.

I think it is a bit broader than use of humans in research. I think like conflict of interest, conflict of commitment. I think even authorship fits under consultation. (001)

That said, other consultants saw these issues as outside of their scope, and some even preferred to leave these matters to their research misconduct office and/or ombudsperson.

We’re not integrated well in the RCR…And so it’s probably no, we’re kind of separate from that. And I almost see us being separate from that intentionally. (005)

Largely because of the type and volume of research happening at their institution, many RECS focused on human subjects research. Some hoped to become more involved in animal and bench research although finding opportunities for collaboration often proved challenging.

Barriers and facilitators of RECS

Barriers

While most RECS were freely available to faculty, staff, and trainees at their institutions, consultants described their services as being underutilized. Many believed that researchers at their institutions lacked awareness of their services’ capabilities, and some even suggested that researchers did not know how to distinguish research ethics issues from other issues related to the conduct of human subject research.

I think a lot of investigators are not going to be able to say, this is an ethical issue. Or this is a problem that I’m having with my IRB application. (013)

Many struggled to advertise their services with methods to catch the attention of investigators in need of assistance, and some had trouble identifying means of advertisement.

Others admitted to not being able to define the outcomes of their services in advance. Some suggested that their services’ lack of tracking of consults inhibited their ability to accurately and comprehensively describe their services to researchers and administrators at their institution. That is, they described the challenge of advertising a service without fully understanding the service’s value.

Well, the big one is definitely awareness…I think another one would probably be the difficulty of describing exactly what the outcomes of our involvement might be in advance. (020)

I think another challenge is trying to assess what our impact is…It’s not.. that hard but it would take a lot of energy and effort to do it. And we haven’t had the bandwidth to do a more formal assessment either through surveys or interviews. (003)

Not having a successful advertising campaign meant that participants often relied upon word-of-mouth. In particular, respondents who reported that they did not have strong relationships with their institution’s administrators, CTSA, or IRB, often felt as if their services were underutilized.

We tend to have to rely on a kind of top down promotion process where you talk to the administrators and say, “Please, please tell the investigators…about us.” (004)

While getting the word out about their services was challenging for most consultants, some expressed hesitancy in broadly advertising their services. They expressed that the service was supported by partial full-time equivalents (FTEs) across individual or multiple consultants. They believed they were at the limit of the amount of time faculty had to support the RECS. They suggested that efforts to increase the number of consults were challenging as creating demand for an already limited resource wasn’t feasible. In order to increase demand, consultants described needing more financial and/or human resources.

I think that’s probably the biggest issue is just whether we’re out there enough. And if we push harder, whether we get flooded in a way that we just can’t handle. (010)

I can’t say I’m looking for more business given that I run it by myself. And now I also run the center. I’m pretty busy, so I’m not like out there recruiting for additional work. (015)

This was especially true for consultants who worked at institutions whose work had never been (or was no longer) funded by CTSA funds or who expressed that they did not feel as if the institution adequately funded their current work. Often, these participants performed consultation work as part of their service obligation to the university or volunteered their time to their institution because they believed the work was important. One participant speaking in the voice of the CTSA stated,

Oh, no money, no ethics…y’all can do that if you want to, but we’re [the CTSA] is not going to pay for it. (022)

Facilitators

At the same time, those who continued to receive funding from their CTSA (after NCATS no longer required ethics to be supported under the grant) had an easier time maintaining their service. CTSA funding often went toward at least one but sometimes multiple faculty members’ time (i.e., FTE). Support from the CTSA also often meant that the RECS could tap into existing platforms to advertise their services like the CTSA’s website, which often served as the main resource for investigators developing and implementing human subject research.

I think the main thing is providing. I think we’re very fortunate that we’ve been given sufficient resources to do this well. And so I cannot underestimate the value of resource availability for consultants and for staff support. (005)

So PIs can go to the consultation services’ website, literally click on the topic area that they’re looking for, submit a ticket, describe specifically what they want a consultation on. (009a)

Having funding dedicated to supporting the RECS also allowed faculty members to be present and participate in institutional events, including grand rounds and other teaching events. Those who had a portfolio of research related to research ethics reported that speaking at these events was easier because they could present their own (often highly respected) research while also advertising the service. Respondents indicated that they felt that participating in these events led to their services becoming integrated into the institution’s research enterprise.

And I teach like a bajillion one off seminars. So, like a lot of our [NIH funded training programs] programs, I’ll go in and I’ll teach a session on research ethics. I teach a lot of research integrity courses for different centers and fellowship programs. (015)

This is something I learned early on and then forgot. And that was how important it is to be part of the regular conversations with the research enterprise, even when those conversations have nothing to do with ethics. (004)

Those whose services were most integrated expressed that word-of-mouth referrals, especially those received by institutional leadership and IRB members, allowed a steady flow of consults that then led to more consults. Some respondents also expressed that their members’ expertise in the field of research ethics and their profile within the institution often helped establish the legitimacy of their service.

They [legal counsel and IRB] have also been happy to refer consults to us when they had questions and so I think we have a pretty good relationship institutionally in terms of being able to communicate with other parts of the university so we are not sort of clashing or making recommendations against what other parts of the university might want to see. (003)

They’re seeking me out because they reached out to somebody else. And that person said, “Talk to [013].” (013)

Accomplishments

Participants whose service was well-integrated into the research enterprise and respected by institutional leadership saw this as a major accomplishment of their service. As the CTSA was no longer required to fund ethics programming, continued support of their services was viewed as a recognition of the services’ impact and importance.

Our [center] is very well integrated and known across the organization. So, they think bioethics. They’re gonna call. It doesn’t matter if we like, have specifically said, we have research ethics or not. (017)

I think we’ve also built more trust around the institution, the CTSA is now known for its ethics expertise “cause we have ethics, like in everything. (016)

Some participants whose services had lost funding or who struggled to build relationships with researchers and leadership often saw integration and funding as signposts of being a successful service. These participants spoke to continuing to exist in an unfavorable environment as being an accomplishment,

I honestly, this is low hanging fruit, but I’ll take it. That we still exist, and we still get consults here and there 15 years…the fact that we can still help folks and…have conversations with important stakeholders in the research enterprise, and know that we’re at least being listened to, if not always used. (004)

In order to become integrated into the research and teaching enterprise of their universities, participants spoke to the importance of having an impact on university policy, grants they helped put together to create a portfolio of research ethics work, and connecting with students and fellows through teaching activities. Participants believed that in order to demonstrate success, they had to contribute to building institutional policy, grants, and teaching, and by doing this, they felt as if research ethics was perceived as a valuable activity at the institution.

Our consultations have had a huge impact on major programs in the university and how they operate, and so that’s an accomplishment. (018)

I have made it [RCR] into a class that I think the students really enjoy. So I think people are more excited about research ethics. And I think that there’s a venue to talk about research integrity. (015)

Some also spoke to one-time successes that facilitated researchers” work in an ethical manner.

There was a researcher who wanted to do very touchy research, and the IRB was feeling like it was not going to fly, and they just there was an impasse. And researcher put in a consultation request, I think, hoping that we would be somehow able to override the IRB. So we had a conversation about like our role in what we could do, and that we’re not here to do that. And then we actually brought everybody [together].. …That ended in a much better way than it was headed. I think the outcome there seemed to be like that person was just not going to get to do this project and they ended up being able to do it in a very careful way that I think was appropriate. (010)

New consultation strategies

Some respondents reported that their consultation services have pivoted to research ethics adjacent areas that were gaining more traction and attention at the national level. They recounted developing relationships with their diversity, equity, and inclusion office or community-engaged research core affiliated with their CTSA as they believed that these avenues would help their service continue to connect with researchers and stay relevant to their institutions’ commitments. Some suggested that research ethics could provide important insights and historical context to conversations surrounding recruitment of diverse participants and ethical engagement with community members.

Everything is about community engaged research. So that raises the level. So, we have a community engaged research core, which I’m a member of, so it raises the level of that. (001)

It’s [ethics] now combined with team-science which is now a more formal element of CTSAs, which I think is good because I think together we can address a lot of new types of issues which neither us nor the team science people have addressed before, especially helping us work with the community engagement people to help us create resources for teams who are wanting to do community engagement. (003)

While these new strategies of engagement were not common across all respondents, they may prove fruitful for other services wishing to connect with researchers and administrators across their institutions.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that RECS in the USA have a shared purpose in assisting researchers and IRBs in facilitating ethical design of research through conversations and consults, teaching, and contributing to the development and review of institutional policies. All services emphasized that their service was not a replacement for IRB review. These findings suggest that RECS have largely followed the advice provided by Taylor et al. (2021) in that services are reaching a broad array of research personnel and adapting to their institutions’ needs [Reference Taylor, Porter and Talati Paquette3].

Our findings also suggest that some RECS continue to receive financial support from their CTSA despite NCATS no longer requiring research ethics programming as a CTSA component. We found that our respondents who perceived that their leadership was supportive of RECS appear to be more likely to receive funding for salary support and have their services promoted to investigators across their campuses.

RECS that do not have strong relationships with their CTSA or broader leadership may wish to attempt to cultivate these relationships, especially as NCATS no longer requires CTSAs to fund research ethics programming [Reference Taylor, Porter and Talati Paquette3] (see Table 1). These relationships could be cultivated through university activities like teaching, presenting at grand rounds, attending institutional meetings, or participating in institutional activities that may be adjacent to research ethics (e.g., community-engaged research efforts) [Reference Taylor, Porter and Talati Paquette3]. Related respondents, who were considered experts in their field, reported that institutional presentations (e.g., grand rounds) on their own research were a way to highlight the value of research ethics consultation or could be used as a promotional tool. That is, many research ethicists used invited presentations about their own research as a way to advertise their services to their institutions’ research community.

A few RECS were attempting to adapt to changing institutional research priorities. These included developing relationships with the community-engaged research components of their CTSA and/or participating in larger discussions about diversity, equity, and inclusion at their institution. These activities were viewed as aligned with research ethics as they often fit into discussions surrounding scientific value of research, recruitment, compensation, and larger issues of justice.

Many consultation services lacked tracking systems, which may contribute to challenges in promoting their services within their institution. Lack of tracking may make it harder for consultants to recall outcomes or events where their service was valued by a researcher and/or contributed to institutional policy. This lack of tracking may become especially problematic as individual consultants retire, shift their career priorities, and/or move institutions, taking their knowledge of the service at its accomplishments with them.

Tracking of research ethics consultations even through simple means like an Excel spreadsheet that can be easily saved and shared, should be seriously considered [Reference Taylor, Porter and Talati Paquette3]. For those interested in more comprehensive tracking systems, previous work has identified key domains a RECS tracking system ought to include [Reference Cho, Taylor and McCormick10]. Tracking allows for institutional knowledge to be preserved and for accomplishments of the services to be easily highlighted and remembered. Tracking can also facilitate reflection on ways to improve the services provided by the RECS and help RECS better understand how and if different methods of advertising and engagement with the institutional research community impact the demand for consults [Reference Taylor, Porter and Talati Paquette3,Reference Cho, Taylor and McCormick10].

Finally, as many of our respondents were late-career scholars and/or were the only consultant at their institution, the field of research ethics needs to seriously consider the consultant pipeline. A recent survey of clinical ethics training programs shows that only one also offers training in research ethics [Reference Fox and Wasserman11]. Although there may be other fellowship opportunities in research ethics that are not highlighted by this survey, the field may want to consider how to train existing ethicists in research ethics and provide support for graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, and early career scholars who wish to develop their expertise in this area.

Limitations

Our research highlights some perspectives of research ethics consultants at about half of the active services in the USA. It is possible that research ethicists in other countries or at institutions not represented by this research would have different experiences and perspectives. However, the findings reported here also triangulate well with previous research findings [Reference Porter, Danis, Taylor, Cho and Wilfond2,Reference Taylor, Porter, Sullivan and McCormick4,Reference McCormick, Sharp and Ottenberg5] and more informal national and international discussions that our research team has taken part in and led (e.g., all research team members are members of the CRECC).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that RECS help researchers and administrators navigate ethical issues that are not fully addressed by current regulations. While RECS continue to exist with variable levels of funding and support, their existence seems to be largely dependent on whether institutional leadership is supportive. As research priorities change, ethicists should be prepared to highlight how their service can continue to contribute to the larger research enterprise, especially as research ethicists are often well-positioned to facilitate deliberation and discussion across and within disciplines. This preparation should involve defining key outcomes of RECS, tracking consults, adapting to new research priorities, and ensuring training and support of new consultants.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2025.10174.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences’ Department of Bioethics and Humanities for providing gift cards for the study. In addition, they would like to thank the participants for their time and the CRECC membership for their feedback on preliminary study materials.

Author contributions

Skye A. Miner: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; Jennifer B. McCormick: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; Holly A. Taylor: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding statement

Dr Taylor’s effort was supported by the Intramural Research Program, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health. The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences provided support for the gift cards.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed here by Dr Taylor are her own. They do not reflect the policies and positions of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.