Salmonella is a genus of enteric gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae bacteria assigned to just two species but many serotypes (Crump and Wain, Reference Crump and Wain2017). Salmonella impacts the agricultural economy through animal disease, affecting many mammalian and avian livestock species, including cows, pigs, goats, sheep and poultry of all types by reducing productivity, weight gain and food conversion efficiency and increasing lethargy and mortality (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang, Ding, Bin and Zhu2023). It also causes morbidity and occasional mortality in humans, from its transmission to humans through contaminated products (via dairy products, meat, eggs, but also on contaminated vegetable surfaces), causing a significant global health burden (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kang, Excler, Kim and Lee2024). The incidence rate of human Salmonella enterica cases in Denmark has been relatively stable at modest levels during 2013–2022, involving few fatalities (mean 16.9 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, Aarø et al., Reference Aarø, Torpdahl, Rasmussen, Jensen, Nielsen, Chen, Engberg, Holt, Lemming, Lützen, Nielsen, Olesen, Rubin and Schønning2024). Nevertheless, for these reasons, it is essential to understand the mechanisms of Salmonella transmission between loci of agricultural infections to support mechanisms to control the spread of infection in livestock.

The Salmonella enterica serovar Dublin (hereafter S. Dublin) is host-adapted to cattle, in which it causes severe symptoms in young and mature animals, severely affecting the economic return of milk herds (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Green, Kudahl, Ostergaard and Nielsen2012; Velasquez-Munoz et al., Reference Velasquez-Munoz, Castro-Vargas, Cullens-Nobis, Mani and Abuelo2024). Although only 0.7% of human Salmonellosis could be attributed to cattle sources in one review (Pires et al., Reference Pires, Vieira, Hald and Cole2014), S. Dublin infection in humans have been found to be caused by Danish cattle isolates (Kudirkiene et al., Reference Kudirkiene, Sørensen, Torpdahl, de Knegt, Nielsen, Rattenborg, Ahmed and Olsen2020), emphasizing the need for disease control.

S. Dublin became a particular challenge among cattle herds throughout Denmark in the late 20th century, which led to a national surveillance programme initiated in October 2002 (Ersbøll and Nielsen, Reference Ersbøll and Nielsen2011) and to an eradication programme that started in 2008, imposing strict limits on cattle movements from likely infected areas (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Houe and Nielsen2021).

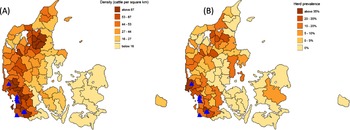

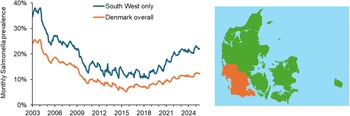

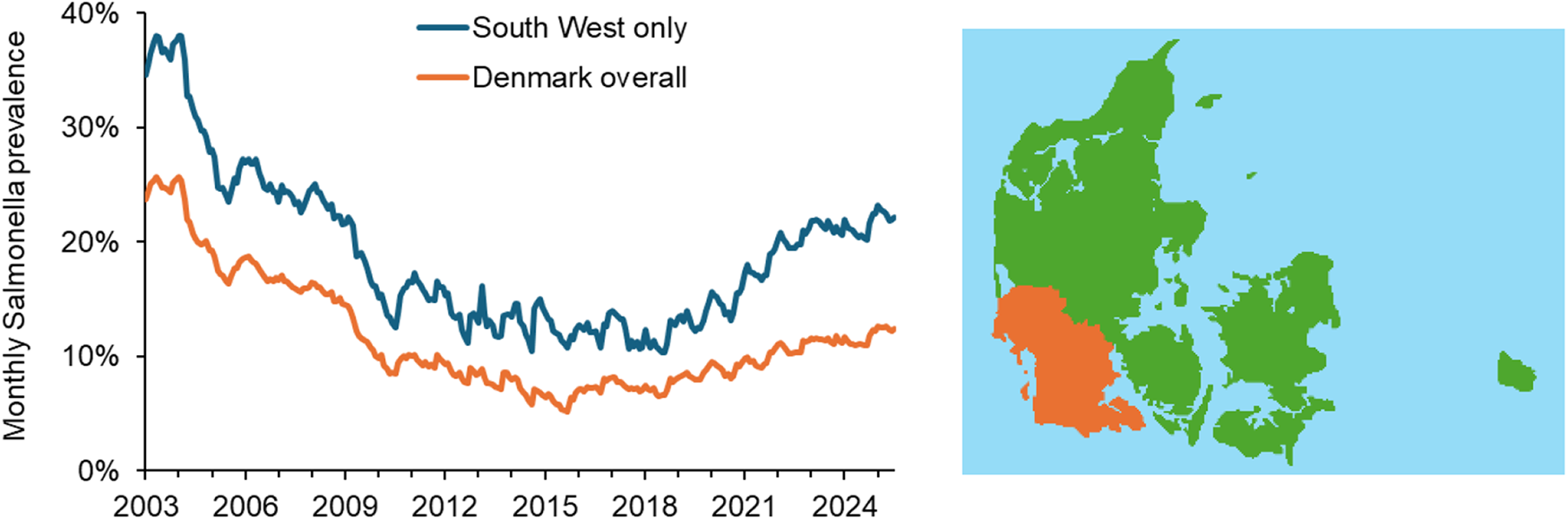

The highest densities of dairy cattle and the highest prevalence of Salmonella among herds are found in southwest and southern Jutland (Fig. 1). However, levels of infection since then have not substantially decreased (Fig. 2) and with the increasing trend for larger dairy units and geographical concentration of herds, there are greater pressures to ensure biosecurity and eradicate the disease among cattle (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Houe, Rattenborg and Nielsen2023).

Figure 1. Maps of Denmark showing (A) the density of cattle km−2 in the Danish Salmonella reporting system areas (which aggregate adjacent post code areas to contain comparable numbers of dairy herds) and (B) percentage prevalence of dairy farms under official restrictions for Salmonella Dublin recorded in the same units. Also shown (blue triangles) are the locations of the seven farms where starlings were sampled in this study. Data from the Central Husbandry Register of the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration.

Figure 2. Monthly records of Salmonella Dublin cases in Denmark show that the prevalence of the disease (expressed here as percentage prevalence among all dairy herds in Denmark as a whole and in the south west of Jutland (indicated in the map above to the right) declined during 2003–2016 but has been increasing again since then. Data were obtained from surveillance of both dairy and non-dairy herds, coordinated by the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration.

Salmonella transmission can take many routes, including foodborne, waterborne, cross-species and vertical transmission, but rodents and insects have been considered major carriers of contamination (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhang, Ding, Bin and Zhu2023). Migratory birds represent likely vectors, yet screening of 2,377 birds of 100 migrating species in Öland, Sweden (where Salmonella Dublin does occur in cattle herds) found only one carrier, a mistle thrush Turdus viscivorus (Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Bonnedahl, Waldenström, Palmgren and Olsen2003). However, suspicion has fallen on the common starling Sturnus vulgaris (hereafter ‘starling’) as a vector for Salmonella dispersal among livestock and poultry, through direct transmission to humans via faecal matter on human food crops through its close association with farms (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Edworthy, Taylor, Jones, Tormanen, Kennedy, Fu, Latimer, Cornell, Michelotti, Sato, Northfield, Snyder and Owen2020a) or in urban areas (Odermatt et al., Reference Odermatt, Gautsch, Rechsteiner, Ewald, Haag-Wackernagel, Mühlemann and Tanner1998; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Snyder and Owen2020b). In Western Europe, starlings are highly migratory and mobile and Salmonella has been detected in starling faeces (Feare, Reference Feare1984) in North America (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Franklin, Hyatt, Pettit and Linz2011, Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Ellis, Pipkin, Mangan, Russell, Bolte, Engeman, Deliberto and Linz2015a; Grigar et al., Reference Grigar, Cummings, Rodriguez-Rivera, Rankin, Johns, Hamer and Hamer2016), where it has also been detected borne on their plumage (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Franklin, Hyatt, Pettit and Linz2011, Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Ellis, Pipkin, Mangan, Russell, Bolte, Engeman, Deliberto and Linz2015a, Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Bentler, Mangan, Russell, Piaggio and Linz2015b) as well as Salmonella Typhimurium once in 40 cloacal swabs taken from starlings in Denmark (Skov et al., Reference Skov, Madsen, Rahbek, Lodal, Jespersen, Jørgensen, Dietz, Chriél and Baggesen2008). Hence, the species has at least the potential to contaminate food and water and to disperse the pathogen between sites (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Franklin, Hyatt, Pettit and Linz2011; French et al., Reference French, Midwinter, Holland, Collins-Emerson, Pattison, Colles and Carter2008). Significantly, numbers of breeding starlings in Denmark declined by 60% between 1976 and 2015, correlated with the dramatic decline in cattle grazing outside, since nesting starlings are dependent on short-grazed pasture with rich invertebrate populations to provision their nestlings (Heldbjerg et al., Reference Heldbjerg, Fox, Levin and Nyegaard2016, Reference Heldbjerg, Fox, Thellesen, Dalby and Sunde2017). With the increasing tendency to keep larger aggregations of cattle indoors year-round, fed grass and maize silage, the habitat to support starlings provisioning their nestlings has also disappeared. In contrast, numbers of breeding starlings in eastern Europe have increased or been stable (Heldbjerg et al., Reference Heldbjerg, Fox, Lehikoinen, Sunde, Aunins, Balmer, Calvi, Chodkiewicz, Chylarecki, Escandell, Foppen, Gamero, Hristov, Husby, Jiguet, Kmecl, Kålås, Lewis, Å, Moshøj, Nellis, Paquet, Portoulou, Schmidt, Škorpilová, Szabo, Szep, Teufelbauer, Trautmann, van Turnhout, Vermouzek, Voříšek and Weiserbs2019) and many of these birds migrate to the Netherlands and United Kingdom to winter, gathering in vast flocks in southwest Denmark in autumn en route. These gatherings attract thousands of tourists to witness their spectacular evening murmurations or black sun (‘sort sol’ in Danish, Solkær, Reference Solkær2023). Ironically, increasingly denied of their pastures and grazed grasslands, large flocks (comprising up to thousands of individuals) of these migrant starlings now resort to feeding on the maize silage fed to bovine stock within the large cattle sheds (in USA termed ‘concentrated animal feeding operations’, CAFOs as used by Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Franklin, Hyatt, Pettit and Linz2011), bringing the birds in close proximity to the feed and livestock, making them a prime suspect among potential dispersive vectors for Salmonella. In North America, where the starling is a human-introduced invasive species, genotyping has demonstrated that Salmonella strains found in cattle at CAFOs are consistently present in starlings visiting them, suggesting the birds as a plausible source of ongoing infection (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Ellis, Pipkin, Mangan, Russell, Bolte, Engeman, Deliberto and Linz2015a) especially because of elevated disease spread in winter months, when starlings and cattle are most concentrated (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Ellis, Tupper, Franklin and Linz2012; Medhanie et al., Reference Medhanie, Pearl, McEwen, Guerin, Jardine, Schrock and Lejeune2014). Yet despite the variety of strains cultured or identified from starlings externally or internally (e.g. Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Ellis, Pipkin, Mangan, Russell, Bolte, Engeman, Deliberto and Linz2015a; Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Lapidge, Hernández-Jover and J-AML2016a) and mounting evidence that starlings theoretically can transmit Salmonella, we may still greatly overestimate the impact of these birds on livestock disease. For instance, proportions of starlings testing positive for Salmonella are frequently low, and many studies lack proof to contribute to a compelling argument that these birds are responsible for introducing the pathogen to uninfected herds (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Snyder and Owen2020b).

In Denmark, the magnitude of the challenge posed by the disease seems to be associated with the intensification of dairy agricultural practices, and because this economic-driven development is unlikely to diminish in the immediate future, from an animal health point of view, it is increasingly important to understand the role played by starlings in the dispersal of Salmonella between herds. For these reasons, the objective of the study reported here was to investigate the occurrence of Salmonella bacteria on free-living starlings captured while foraging inside cattle sheds at seven Salmonella-positive Danish dairy farms in the high prevalence region of southwestern Jutland.

Material and methods

Selection of farms

Cattle are raised throughout Denmark, but highest densities (Fig. 1A, >86 cattle km−2, see also figure 1 in Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Houe and Nielsen2021) and greatest levels of test-positives for S. Dublin (Fig. 1B and see figure 3 in Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Houe and Nielsen2021) are concentrated in southwestern Jutland. We therefore focused on capturing and testing starlings on farms within this area with positive-tested herds, where farmers reported the birds present on animal feed inside cattle sheds (Fig. 1). We tested at one farm in autumn 2023 in a pilot to trial methods and feasibility and selected six farms for testing in 2024 where farmers gave permission to catch, consistent with geographical spread, suitable catching opportunities, local starling abundance and available resources. All herds tested for S. Dublin had bulk tank milk levels above 50 ODC (Optical Density Corrected, a measure of antibody frequency in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)) Salmonella antibodies indicating active infection with S. Dublin among the lactating cows. Warnick et al. (Reference Warnick, Nielsen, Nielsen and Greiner2006) found that the herd sensitivity and specificity of the Danish S. Dublin programme was 95% and 96% respectively, based on four consecutive bulk tank antibody analyses. The predictive value positive was found to be 80% at a 15% herd level prevalence. We accept, however, that serology can stay high in bulk tank milk samples for a period after the infection has been removed from a herd but selecting these farms represented our highest chance of detecting Salmonella on caught starlings. In addition, on six out of the seven herds, blood tests from calves tested positive for Salmonella during the period we were sampling starlings, indicating the simultaneous presence of the bacteria and active infection among the animals. While test locations were clearly in no way randomly selected, they ensured infection presence in large herds in recent weeks coincident with high starling activity near stock, providing the highest potential for disease transmission. At selected farms, we established trail cameras to monitor starlings in cattle sheds at 15-minute intervals to confirm presence of birds and the timing and abundance of their presence prior to catching to improve our chances of capture and determine the potential for disease transmission.

Catching and handling starlings

Typically, Danish dairy cows are kept in large airy cowsheds with high ventilated rooves, open side walls and large gateways for access for tractors and trailers delivering feed. The open side walls can be closed using netting, but during summer and autumn, the birds generally have unlimited access in and out of the cowshed interior and feedstuff spread for the cattle in the feeding aisles. Actively feeding starlings were caught in mist nets pre-erected around cattle shed windows, gates and doors into which feeding starlings were flushed from inside to ensure all captured and processed starlings had been foraging inside. We gently pushed starlings out from cattle sheds by slowly walking down the central feed aisle, repeating this method to catch birds in mist nets during several catching attempts throughout the day. Birds were immediately released from mist nets and transferred to dark plastic keeping boxes with newspaper lining the base, in which they were transported to the field-lab, established in adjacent farm buildings, where they were processed. Each bird was removed from the box and handled by one person; samples for Salmonella testing were taken (see below), the bird was then ringed (with a standard metal Zoological Museum Copenhagen ring), measured, weighed and released again. Between catching attempts, all boxes and lining newspaper were sampled with swabs for Salmonella testing, cleaned, disinfected and dried in preparation for the next capture round. The following other bird species were unintentionally caught in the mist nets during the field work and were kept separate from starlings in cotton bird bags, ringed, measured and tested using the same procedure as for the starlings: one collared dove Streptopelia decaocto, 11 barn swallows Hirundo rustica, and one house sparrow Passer domesticus.

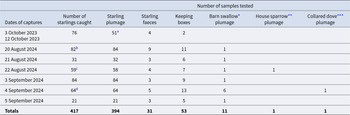

In October 2023, we conducted a pre-investigation trial at one dairy farm to test capture and sampling procedures, followed by one catching day, at the same dairy farm, resulting in 76 ringed starlings, from which 51 plumage swab samples were taken for Salmonella testing (Table 1). In 2024, we caught and ringed 338 starlings at six different farms. In all, we caught and ringed 414 starlings at seven different dairy farms (21–84 on each farm) in southwest Jutland in Denmark during August–October 2023 and 2024 (Table 1), when most starlings were staging in the area and foraging regularly in large numbers inside the cattle sheds. Due to turnover and movements in and out of the sheds and farmyards, it was not possible to estimate the number of starlings present on the farms and in the cowsheds on the catching days, but up to 10,000 birds were present in cowsheds at maximum.

Table 1. Summary of daily numbers of samples taken from captured starlings (and other species as indicated) and other sources of samples taken from Jutland dairy farms according to date and year. Superscripts indicate incidences of sampling of previously captured and ringed starlings. A few birds were tested without being ringed

* Hirundo rustica, **Passer domesticus, ***Streptopelia decaocto.

a Not all captured birds were sampled during initial catches to avoid keeping birds too long.

b Including a recaptured adult male ringed in Östergötland, Sweden, 513 km away on 20 May 2023.

c Including a recaptured first year female ringed in this study 6.5 km north on 21 August 2024.

d Including a recaptured adult female ringed in Nottinghamshire, England, 670 km away on 21 January 2023.

Sampling and testing for Salmonella

Each tested, captured starling was swabbed using a sterilized commercial gaze swab moisturized with 10 ml of buffered peptone water (Model A04121C, SodiBox, Nevez, France), wiping down the breast feathers, legs, feet and undertail coverts to collect any trace of external Salmonella contamination of the plumage and legs. Any ejection of faecal matter from an individual was also swabbed using the same technique and after all birds were removed from keeping boxes, the insides and newspaper lining of which were also subject to extensive swabbing, with the derived material stored separately as individual samples. Since birds were present in these boxes for periods of up to 30 minutes, and because birds invariably defecate when handled, it seems likely that all caught individuals will have defecated in these boxes, so swab samples from the internal surfaces of the keeping boxes will have accumulated faecal material from all birds kept captive in them. Once taken, the samples were hermetically sealed in plastic bags, placed in cooler boxes at 0–5°C and driven to refrigeration storage at the laboratory within a maximum of five hours of being sampled for later analysis. In addition to the samples described above, ten samples of starling droppings were collected from surfaces in cowsheds in each of four other Salmonella-positive dairy farms (i.e. in addition to the seven farms where starlings were caught) and pooled to generate five samples each. Although these results are presented here, they were not included in the other calculations or in the statistical analysis.

The samples were analysed at a commercial laboratory (Eurofins, Vejen, Denmark) according to the ISO 6579-1:2017 (2017) standard for detecting Salmonella serotypes. This broadly consists of pre-enrichment (to boost to detection levels damaged Salmonella or those in very low densities) in buffered peptone water at 34–38 degrees Celsius for 18 h and incubation in Rappaport-Vassiliadis medium at appropriate temperatures for 24 h. After this, the cultures obtained were plated out on a solid selective medium at 37 degrees Celsius for another 24 h. Colonies of presumptive Salmonella were then subcultured and their identity type confirmed by appropriate biochemical and serological tests following ISO/TR 6579–3. The ISO 6579-1:2017 (2017) standard test protocol detects all Salmonella enterica subspecies and serotypes down to a few colony forming units (cfu) per 25 ml sample (Mooijman, Reference Mooijman2018; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Wolfram and Desin2024). Although studies suggest infectious dosage, shedding intensity, and shedding duration may vary by bacterial strain, inoculation of wild birds with Salmonella resulted in shedding rates of 104–109 cfu per ml during experimental infection periods (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Snyder and Owen2020b). Hence, these protocols should easily detect all types of Salmonella originating from active shedding in starling faeces and potentially at extremely low densities swabbed from plumage and other body parts.

Statistical analyses

Migrating starlings stay within this part of Denmark in autumn resting during their migration towards ultimate wintering areas further south and west. However, as stated above, for the purposes of this analysis, we assume that they are free to move between cowsheds, because as they commute daily to and from overnight roosting places, numbers at individual farms vary every day and, in our study, we caught the same bird on different farms on different days. Thus, it was assumed that the starlings caught in the cow sheds were a representative sample of the population from the area, so the individual sampled bird was the study unit (n = 394) and not the cowshed. Estimated prevalence of Salmonella in the starlings was calculated following the method of Rogan and Gladen (Reference Rogan and Gladen1978) together with 95% confidence limits (CL) generated by the methods of Reiczigel et al., Reference Reiczigel, Földi and Ózsvári2010). We used the EpiTools calculator for estimation of true prevalence with an imperfect test (Sergeant, Reference Sergeant2018), setting the test sensitivity parameter to 0.7 and test specificity to 1.0, presenting Blaker and Wilson CLs as recommended for such general studies. Not knowing the precise performance of the laboratory culture method for starling faeces, the sensitivity and specificity were assumed to be 0.8 and 1.0, respectively (as for cattle faeces, Baggesen et al., Reference Baggesen, Nielsen, Sørensen, Bødker and Ersbøll2007). However, the overall sensitivity was lowered to account for capturing infectious doses of bacteria on the birds.

Results

In October 2023, we caught 76 starlings at one dairy farm (of which we tested the plumages of 51) and in August–September 2024, we caught 341 starlings at six dairy farms in southwest of Denmark, of which two were already ringed elsewhere (one in Sweden and one in England) and one specimen was caught at two different dairy farms (see Table 1). Of the 394 samples taken from these starlings, 31 samples from their faeces, 53 samples of cumulative faecal deposition in keeping cages and 13 samples from the plumages of three other birds species caught in cowsheds at the six farms, none tested positive for Salmonella (Table 1). Samples of droppings from the four other cowsheds all also returned negative test results for Salmonella. From this, we conclude the estimated prevalence of Salmonella in the sampled starling population was zero. Apparent prevalence was zero with upper CL of 0.0097 (Wilson CL) and zero for true prevalence and upper CL 0.0138 (Blaker CL, Sergeant, Reference Sergeant2018).

Discussion

This investigation of the prevalence of Salmonella spp. on Danish starlings found no trace of the pathogen on the plumage of c.400 birds nor in their faecal material tested at Danish dairy farms where stock had been tested positive for the disease. Swabs of surfaces covered with bird faeces within cowsheds at another four infected farms also tested negative for Salmonella spp. Given that the estimated upper 95% CL of the prevalence was calculated to be around 0.01 and that samples were taken from cowsheds with very high risk of contamination, the results indicate that even if Salmonella is present in the starling population the probability of transmission to other herds is very low, if not negligible.

These findings are surprising given the experiences in the United States, where Salmonella spp. has been frequently found in faeces from starlings and on their plumage. Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Ellis, Pipkin, Mangan, Russell, Bolte, Engeman, Deliberto and Linz2015a) reported that starlings and other wild birds contaminate the feed and water resources in the farm mechanically, by physical contact with Salmonella rather than being ingested and ejected to contaminate cattle feed via their faeces. Nevertheless, 17% of washes of plumage and 32% of gastrointestinal tract samples from 100 starlings shot at one cattle feedlot in Moore County, Texas tested positive for S. enterica (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Ellis, Pipkin, Mangan, Russell, Bolte, Engeman, Deliberto and Linz2015a). In a sample of 174 starlings caught in Virginia and Maryland, 13.2% of faecal samples tested positive for Salmonella (Pao et al., Reference Pao, Hagens, Kim, Wildeus, Ettinger, Wilson, Watts, Whitley, Porto-Fett, Schwarz, Kaseloo, Ren, Long and Luchasky2014). Grigar et al. (Reference Grigar, Cummings, Rodriguez-Rivera, Rankin, Johns, Hamer and Hamer2016) found 5.9% of faecal samples taken from starlings at night-time roosts at retail parking lots in Texas and Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Franklin, Hyatt, Pettit and Linz2011) reported 2.5% prevalence in gastrointestinal tract samples taken at Texan cattle food lots also contained Salmonella. A sample of 868 starlings caught by mist nets at 38 field sites throughout the state of Ohio recorded a 7.1% Salmonella prevalence (Morishita et al., Reference Morishita, Aye, Ley and Harr1999).

So why the difference between the Danish and North American studies? Firstly, it is important to remember that the S. Dublin that has been persistently identified in Danish cattle herds is considered host-adapted to cattle, which may make it difficult for this serovar to infect starlings. Interestingly, the S. Dublin has never been identified in starlings connected to cattle lots in any of the North American studies. For instance, on American fed lots, Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Franklin, Hyatt, Pettit and Linz2011) detected 4 serogroups of 18 serotypes (synonymous with serovars), Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Ellis, Pipkin, Mangan, Russell, Bolte, Engeman, Deliberto and Linz2015a) 4 serogroups of 6 serotypes and Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Hyatt, Bentler, Mangan, Russell, Piaggio and Linz2015b) 5 serotypes, none of which included S. Dublin. It is therefore possible that something about S. Dublin (despite its prevalence in cattle) that makes it less likely to be transferred or carried by starlings in Denmark.

Secondly, Danish animal health and Salmonella control programmes may have constrained the prevalence of S. Dublin in cattle below those in North America (despite the fact that Salmonella vaccines have never been used in Denmark), just making it rarer in cowsheds in particular, and in the agricultural environment in general. A longitudinal study of 14 Danish dairy herds with bulk-tank ELISA results >50 ODC% found very low per-sample prevalence of faecal shedders in adult cattle (mean 0.7%, maximum 2.8%, Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2013). Hence, it is highly likely that very low culture-positivity will be found in single faecal samples from cattle as a reflection of its rarity in the cowshed environment. A larger study of 26,987 samples from 110 US farms with 93% prevalence also only isolated Salmonella spp. from 4.8% of faecal and 5.9% of environmental samples (Fossler et al., Reference Fossler, Wells, Kaneene, Ruegg, Warnick, Bender, Godden, Halbert, Campbell and Zwald2004) In addition, Salmonella enterica survival in the environment is temperature and moisture dependent (e.g. Deblais et al., Reference Deblais, Helmy, Testen, Vrisman, Jimenez Madrid, Kathayat, SA and Rajashekara2019); hence, different manure management, farm hygiene standards and climate may further reduce the environmental persistence and accessibility of S. Dublin to free ranging starlings in Denmark compared to North America. For instance, Medhanie et al. (Reference Medhanie, Pearl, McEwen, Guerin, Jardine, Schrock and Lejeune2014) found Salmonella in only two faecal samples from starlings taken in Ohio out of 179 (1.12%) tested in their study and only during winter (when starlings usually are absent from Denmark).

Thirdly, North American Salmonella testing may be picking up serovars that are not necessarily a danger to cattle. For instance, only three out of 434 (0.7%) feedlot, faecal or intestinal samples from a Kansas cattle feedlot tested positive for Salmonella, two of which were variants associated with pigs rather than cattle (Gaukler et al., Reference Gaukler, Linz, Sherwood, Dyer, Bleier, Wannemuehler, Nolan and Logue2009). Generally, investigations and reviews of wild-bird salmonellosis repeatedly find S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (of minor importance to cattle) to be the dominant serovar detected in sick and carriage isolates from passerines, gulls and many other wild birds (e.g. Fu et al., Reference Fu, M'ikanatha, Lorch, Blehert, Berlowski-Zier, Whitehouse, Li, Deng, Smith, Shariat, Nawrocki and Dudley2022; Wigley, Reference Wigley2024). Note that although our screening protocol would have detected all forms of Salmonella spp., S. Dublin can be challenging to culture compared to other species because of the nature of the bacteria and the concentrations in which it is shed (Baggesen et al., Reference Baggesen, Nielsen, Sørensen, Bødker and Ersbøll2007)

Finally, despite the evidence that starlings are able to carry and potentially transmit Salmonella, Cabe (Reference Cabe2021) considered that the impact of starlings on contributing to livestock disease in Europe and elsewhere may be small. He suggested that excepting the North American studies above, the percentage of starlings which test positive for Salmonella is often quite low (<1.3%). He continued that ‘many details of a compelling argument are missing in many studies’, citing Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Snyder and Owen2020b). He also reported an Australian year-round analysis had found the probability of exposure of domestic pigs to Salmonella from starlings to be very low (Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, J-AML, Lapidge and Hernández-Jover2016b). No Salmonella isolates were found in 49 British tested starling carcases from throughout the year (Pennycott et al., Reference Pennycott, Park and Mather2006) and 140 starlings hunted for sport in Italy during June–October all tested negative for Salmonella (Pasquali et al., Reference Pasquali, De Cesare, Braggo and Manfreda2014), compared to 27% among sampled birds in Iran (Malekian et al., Reference Malekian, Shagholian and Hosseinpour2021).

Hence, the prevalence and risk of cross contamination of cattle herds by Salmonella associated with wild European starlings seems highly dependent on serovar, geographical region, site and case. What is evident is that the magnitude of this problem is likely associated with the degree of intensive agricultural practices and that each case needs to be addressed in isolation with respect to that factor, since presence in faeces varies a great deal with different studies throughout the world. We also fully accept that we cannot rule out the possibility that low level detection might have occurred with vastly inflated sample sizes at very many more cattle herds than was possible in this study. However, the total absence of any external or faecal signs of Salmonella associated with our sample of starlings at farms that already tested positive under the Danish Salmonella monitoring programme is highly significant.

We therefore conclude that starlings were highly unlikely to have been a significant factor in the spread of Salmonella between Danish cattle herds in the contemporary agricultural landscape, implying that the infection is transferred between herds via other routes. This suggests that, in the battle to control the spread of this disease, the focus must shift from starlings to investigating the other contacts that may occur between cattle herds as a cause of disease spread. There is therefore an undoubted need to increase infection protection through improved biosecurity on individual farms and by initiating further research to identify other mechanisms for infection of new herds.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the permission of the farmers involved for their kind hospitality and for allowing us to catch and test starlings on their properties and the financial support from the Mælkeafgiftsfonden to carry out this work. All capture and handling of birds followed the guidance of the Copenhagen Bird Ringing Centre, who are also kindly thanked for the supply of rings and information on ringed individuals. We thank Jørgen Nielsen for preparing the maps and graphs and to the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their help to improve an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests associated with this study.