Introduction

Despite global advancements in palliative care, substantial barriers remain in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Latin America. In Mexico, limited opioid access, scarce home-based care services, and insufficient professional training compromise the quality of end-of-life support (Pastrana et al. Reference Pastrana, De Lima and Sánchez-Cárdenas2021; Instituto Medicina del Dolor y Cuidados Paliativos I Reference Romero-Gómez2023). These structural limitations intersect with cultural conceptions of dying, often shaped by spiritual, familial, and social frameworks (Carr Reference Carr2003; Levy et al. Reference Levy, Ely and Payne2005; Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Wu and Chiu2005; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Lin and Cheng2016).

The concept of a Good Death – also referred to as Quality of Death or Dignified Death – has gained prominence across clinical and anthropological disciplines (Engelberg Reference Engelberg2006; Hirai et al. Reference Hirai, Miyashita and Morita2006; Detering et al. Reference Detering, Hancock and Reade2010; Hales et al. Reference Hales, Zimmermann and Rodin2010; Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Gerritsen and Koopmans2015). Broadly, it refers to the extent to which an individual’s preferences for their dying process are fulfilled, often interpreted through the perspectives of family members or healthcare professionals (Patrick et al. Reference Patrick, Engelberg and Curtis2001). These preferences encompass physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual dimensions considered desirable at the end of life (Carr Reference Carr2003; Levy et al. Reference Levy, Ely and Payne2005; Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Wu and Chiu2005; Hirai et al. Reference Hirai, Miyashita and Morita2006; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Lin and Cheng2016). However, prevailing definitions have largely reflected Western biomedical models that prioritize physical comfort and autonomy, frequently excluding relational, existential, and culturally situated aspects (Hart et al. Reference Hart, Sainsbury and Short1998).

A systematic review (Krikorian et al. Reference Krikorian, Maldonado and Pastrana2020) examining patients’ perspectives identified 29 studies and proposed a two-level conceptual model. The first level comprises core individual attributes – private yet widely shared concerns such as pain and symptom management and the preservation of personhood. The second level includes contextual factors that shape the meaning of a Good Death and vary across populations, including cultural norms, religious beliefs, and social expectations. Collectively, these findings underscore the individuality of dying and the diversity of preferences that inform what is considered a Good Death.

In Mexico, where healthcare inequities and cultural pluralism coexist, understanding what constitutes a Good Death demands a pluralistic and inclusive approach. This study seeks to explore how advanced-stage patients, family caregivers, and physicians conceptualize a Good Death, identifying its core components and contextual variations. By foregrounding diverse stakeholder perspectives, the findings aim to inform culturally sensitive palliative care practices in resource-limited settings.

Methods

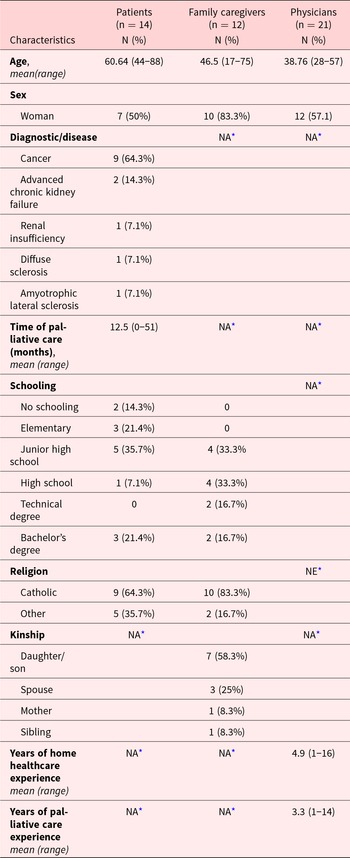

This qualitative study explored perceptions of a Good Death among patients, caregivers, and physicians within a home-based palliative care program in Mexico City. Between January and March 2019, semistructured interviews were conducted with 47 participants (Table 1): 14 patients with advanced oncologic and nononcologic conditions, 12 family caregivers, and 21 physicians involved in end-of-life care.

Table 1. Sample: Demographic characteristics

* NA: not applicable, NE: not evaluated.

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling within Médico en Tu Casa, a public initiative that delivers home-based palliative care in Mexico City. Semistructured interviews were conducted in Spanish, lasting between 60 and 90 minutes, and carried out with written informed consent. The interview guide explored the meanings attributed to death, experiences with care provision, and expectations surrounding a Good Death.

All interviews were recorded using the iTalk application (v4.75 for iOS 13.7) and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were analyzed by a single coder using ATLAS.ti (version 9), following generic purposive sampling principles (Hood Reference Hood, Bryant and Charmaz2007). No predefined categories were applied. Open coding was initially used to identify two emergent themes: the designation of the desired death and its defining characteristics. Quotations were selected across transcripts and coded accordingly. Axial coding was then employed to construct categories and subcategories based on intercode relationships. Frequencies were examined descriptively. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS (version 20), applying standard descriptive statistics.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Mexico City Ministry of Health under registry number 101-101-01-19, and by the National Bioethics Commission under registry number CONBIOETICA-09-CEI-004-20280213.

Results

Designation of the desired death

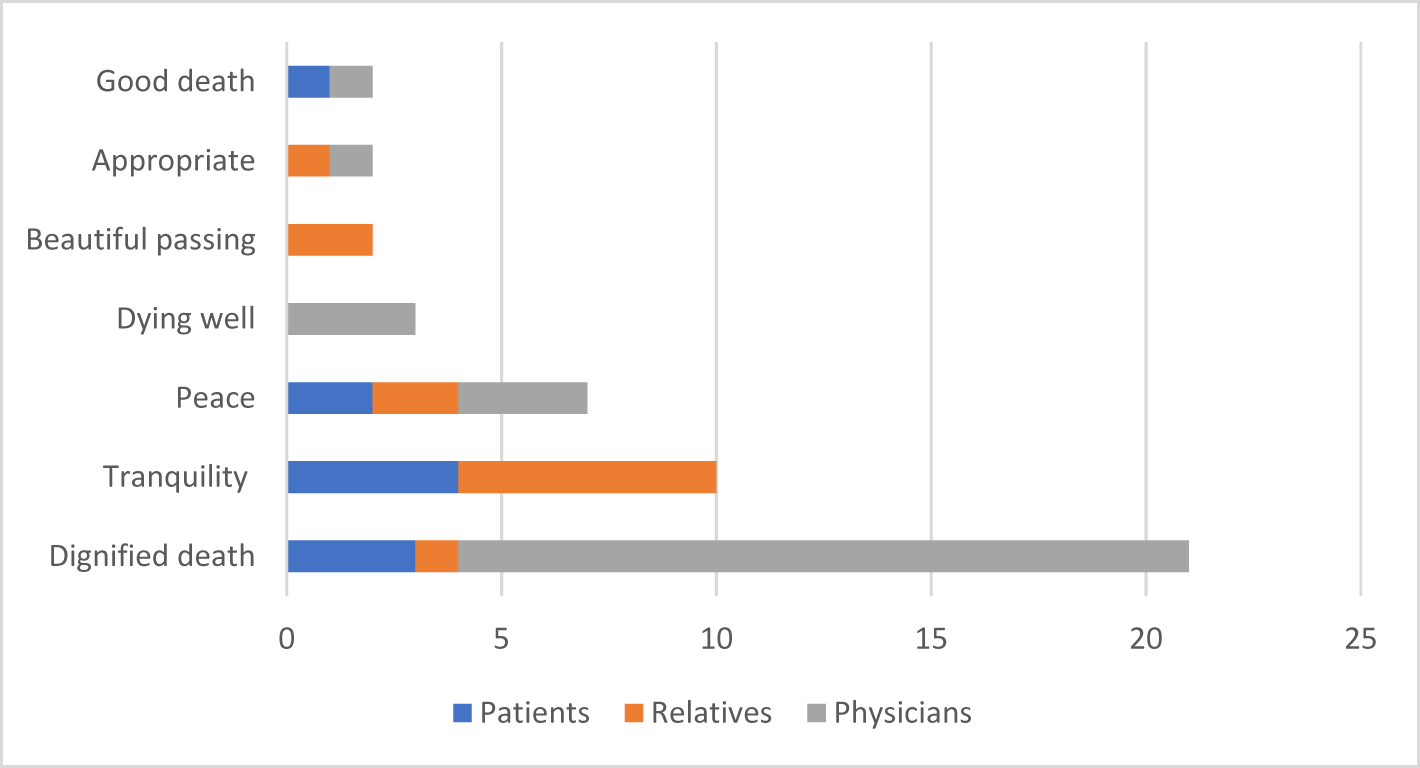

Dignified Death and Peaceful Death were the most frequent designations participants assigned to passing in accordance with the patient’s wishes. Figure 1 shows the designations mentioned. Some participants listed more than one designation.

Figure 1. Frequency of the designation of a passing fulfilling the patient’s wishes, according to patients, their relatives and physicians.

Characteristics and temporal dimensions of dying and death

The qualitative analysis identified death not only as a multidimensional experience – encompassing physical, psychological, interpersonal, spiritual, and structural categories – but also as a multitemporal process, involving three key stages: preparation for death, the moment of death, and the postdeath experience. These dimensions were shared across all three groups of participants: patients, family caregivers, and physicians.

Element categories of dying and death

Physical Elements The physical dimension was addressed consistently across interviews and was inductively grouped into five subcategories (e.g., symptom management); awareness and cognition; location and environment; duration and timing; and what they wish to occur after death (e.g., funeral arrangements and honoring wishes for the handling of remains): “…that their symptoms are under control, prevent ulceration or dehydration, to keep them clean through washing and bathing” (physician, ages 50–60 years old); “…what I want when I die, what I would like my funeral to be like, in other words, to talk about all these thanatological issues” (physician, ages 20–30 years old).

Psychological elements. Patients, relatives, and physicians consistently emphasized the importance of psychological comfort at the end of life. This included the need for emotional calm, the avoidance of suffering, and the capacity to accept death – both one’s own and that of a loved one – without feeling like a burden. Acceptance emerged as a central theme in the narratives: “Calm, no suffering… In my case, my wife, well, acceptance… The first thing must be acceptance. We know we are all going to die; maybe it’s acceptance of the loss. I think it’s not always easy to accept the loss of a loved one” (cancer patient, ages 30–40 years old).

Interpersonal elements. Participants frequently highlighted the significance of interpersonal dynamics in shaping a dignified and meaningful dying process. These included the presence of loved ones, the avoidance of abandonment, physical closeness (e.g., holding hands), preparing family members emotionally, and ensuring that decisions align with the patient’s expressed wishes: “Affection, physical care, comfort, cleanliness” (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient, ages 50–60 years old); “Fulfilling patients’ preferences regarding palliative care; also, advance directives that express whether they want to be at home or in a hospital, whether they want intubation or not, whether they want to donate organs or not” (physician, ages 30–40 years old).

Spiritual elements. Spiritual aspects were frequently referenced by participants and were inductively grouped into three categories: peace, religion, and the search for meaning and transcendence. These categories encompassed traits such as feeling at peace, seeking forgiveness, connecting with God or a spiritual entity, and achieving a sense of life satisfaction and personal fulfillment: “…feeling at peace knowing that all your affairs are left in order for your loved ones; not leaving any problems behind” (family caregiver, ages 40–50 years old); “Clinging to what we preach in religion, which is hope; knowing that this is not the end, maybe medically, but there is more beyond” (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient, ages 50–60 years old); “…if you are a spiritual person, something I’ve seen with terminal patients is that they become more spiritual, they find themselves, they are content with their lives” (physician, ages 30–40 years old).

Structural elements. A fifth category emerged from the data, encompassing structural factors not directly tied to the individual but influencing the dying process. These included healthcare provision, financial concerns, and legal arrangements. Participants referred to the importance of sustained care until death, minimizing economic burdens, and ensuring access to palliative services: “this implied medical and psychological care” (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient, aged 50–60 years old); “keep them from spending money” (cancer patient, ages 70–80 years old); “receiving palliative care at home” (physician, ages 20–30 years old).

Multitemporality of dying and death

The traits identified within the physical, psychological, interpersonal, spiritual, and structural categories were found to be relevant across distinct temporal phases: before, during, and after death. The period preceding death – termed preparation for death – encompassed a range of conditions drawn from all five categories. Physical aspects included symptom management, awareness of illness, a pleasant environment, and arrangements for postmortem care. Psychological aspects involved achieving emotional peace and relief from financial or emotional burdens. Spiritual aspects reflected religious guidance and a sense of life satisfaction. Interpersonal aspects included communication with loved ones and the identification of advance directives. Structural aspects referred to access to medical and psychological care, as well as legal considerations. As one participant expressed: “No financial or emotional problems; to say and do everything that must be said and done in life. Right? Don’t keep anything bottled up and say it, discuss it, resolve it” (family caregiver, ages 40–50 years old).

According to participants, the moment of death should be marked by physical comfort, emotional tranquility, and relational closeness. Patients expressed the need to be pain-free, asleep, and at home, receiving continuous medical care, without fear, and surrounded by loved ones who themselves are at peace. As one participant described: “…holding my hand, caressing, talking; us four together and falling asleep” (cancer patient, ages 40–50 years old).

Participants described a Dignified and Peaceful Death as one that transcends the moment of physical death. It involves the fulfillment of patients’ wishes regarding cremation, burial, and/or organ donation (physical elements); the alleviation of emotional and financial burdens (interpersonal elements); the integration of religious beliefs and legacy (spiritual elements); and the provision of psychological support for bereaved family members (structural elements). As one relative expressed: “…for my children to be happy; if they’re happy, I think I will also be happy” (family caregiver, ages 40–50 years old).

These findings support a temporally distributed and relational understanding of Dignified and Peaceful Death, emphasizing that its construction begins with early awareness of mortality and extends beyond the physical moment of dying. The data suggest that end-of-life care should be responsive not only to biomedical needs but also to broader existential, emotional, and structural dimensions across the dying continuum.

Discussion

Dignified and Peaceful Death emerged as the most frequently cited designation used by participants to describe a patient’s passing that aligns with their expressed wishes. The attributes associated with this designation closely mirror those identified in previous literature (Peruselli et al. Reference Peruselli, Di Giulio and Toscani1999; Steinhauser et al. Reference Steinhauser, Clipp and Tulsky2002; Carr Reference Carr2003; Ethunandan et al. Reference Ethunandan, Rennie and Hoffman2005; Levy et al. Reference Levy, Ely and Payne2005; Hirai et al. Reference Hirai, Miyashita and Morita2006; Karlsson et al. Reference Karlsson, Milberg and Strang2006; Hales et al. Reference Hales, Zimmermann and Rodin2010; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Lin and Cheng2016), encompassing physical, psychological, interpersonal, and spiritual dimensions. Structural aspects – such as institutional or systemic conditions – were mentioned less frequently.

Rebalancing the experience of death and dying requires systemic transformation across the interrelated social, cultural, economic, religious, and political dimensions that shape how these processes are understood, lived, and managed (Sallnow et al. Reference Sallnow, Smith and Ahmedzai2022). In Mexican culture, emotional and spiritual accompaniment by family and close community members remains a deeply rooted tradition during dying and bereavement (Gómez-Gutiérrez Reference Gómez-Gutiérrez2011). Participants emphasized the need for a healthcare system that offers personalized care and responds to emotional and psychological needs. Their accounts point to a perceived need for strengthening access and quality in Mexican health services – particularly in funding, infrastructure, and human resources. These improvements may be especially critical for vulnerable populations facing disproportionate barriers to care.

Krikorian et al. (Reference Krikorian, Maldonado and Pastrana2020) identify the structural dimension of a Good Death as a key determinant of its perceived dignity. While its core components – physical, psychological, interpersonal, and spiritual – are often regarded as deeply personal, they reflect the multifaceted nature of end-of-life experiences. The narratives in this study reinforce this view, showing how participants conceptualize dignity not only through individual experiences but also through broader conditions that enable or hinder compassionate care. Their accounts underscore the importance of institutional responsiveness, continuity of care, and culturally sensitive support systems – elements that situate the structural dimension as inseparable from the personal experience of dying with dignity.

Patrick’s conceptual model of Dignified Death underscores the centrality of patient-related factors, alongside the structure and process of care, in achieving optimal outcomes and enhancing both the quality and duration of life for individuals receiving palliative care (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Patrick and Engelberg2002). The findings of this study support this framework, highlighting the structural dimension as a critical component in the provision of dignified, patient-centered care.

While physicians frequently invoke the term “Dignified Death,” patients and their families tend to emphasise the notion of a “Peaceful Death.” This study proposes the designation Dignified and Peaceful Death as a unifying concept that reflects both clinical and experiential perspectives, offering a culturally resonant framework for evaluating the quality of death within the Mexican palliative care context.

Several characteristics of a Dignified and Peaceful Death are both multidimensional and temporally transversal. For instance, being pain-free and experiencing a sense of peace span physical, psychological, and spiritual domains. These traits are identified as relevant not only during the preparatory phase but also at the moment of death, underscoring their enduring significance across the end-of-life trajectory.

Many traits associated with a Dignified and Peaceful Death, as described by participants across the three sample groups, are dynamic and subject to change. Aspects such as pain management or settling legal affairs may evolve throughout the illness trajectory. In contrast, traits like maintaining consciousness may be constrained by disease progression. Additionally, some elements of dignity – such as funeral arrangements and the respectful handling of remains – can be planned and enacted after death, reflecting the continuity of care beyond the moment of dying.

This study highlights notable divergences between the traits prioritized by patients and those emphasized by physicians (Steinhauser Reference Steinhauser2000). Patients frequently underscored maintaining consciousness, being at peace with God, avoiding the perception of being a burden, engaging in prayer, and ensuring funeral arrangements. Physicians, by contrast, focused on managing physical and emotional symptoms, awareness of the dying process, resolution of family and legal affairs, and the provision of adequate clinical care. These differences reflect distinct conceptualizations of dignity and underscore the need for integrative approaches that honor both medical and existential dimensions of dying.

Across the three sample groups, there was a broad consensus regarding the relevance of physical and psychological dimensions in defining a Dignified and Peaceful Death, with patients and physicians showing the greatest alignment. However, differences emerged in other domains. In the spiritual category, only physicians referenced the meaning of life and transcendence. In the interpersonal domain, physicians uniquely emphasized fulfilling the patient’s wishes – highlighting their role in end-of-life communication. The structural category further illustrates these divergences: physicians alone mentioned legal affairs and were the only group not to identify financial concerns as a trait of dignified dying. Despite these differences, all groups recognized the value of medical, psychological, and palliative care at the end of life.

Avoidance of end-of-life conversations contributes to inadequate care, as assumptions tend to obscure the nuanced and individualized nature of the dying process. Participants revealed that when communication is limited, healthcare providers may overlook personal values, cultural preferences, and emotional needs essential to a Dignified and Peaceful Death. These findings underscore the importance of open, empathetic dialogue in aligning care with patient and family expectations.

Conclusion

The concept of a Dignified and Peaceful Death reveals nuanced differences across stakeholder groups. Physicians tend to emphasize physical symptom control, existential meaning, and legal considerations. Patients and relatives, while sharing core values of pain relief, tranquility, and compassionate care, diverge in their priorities: patients and physicians underscore hygiene and personal well-being, whereas relatives focus more on the relational and caregiving dimensions.

Despite these distinctions, a shared understanding emerges – one that affirms dignity, peace, and attentiveness as essential components of end-of-life care. Crucially, a Dignified and Peaceful Death is not a passive occurrence but a process that must be actively constructed. It requires the engagement of patients, who articulate goals of care; relatives, who offer emotional and practical support; and healthcare professionals, who provide clinical expertise and ethical stewardship.

This construction begins not in the final days but in the early recognition of mortality as part of life. Such awareness fosters intentionality in care and imbues the dying process with meaning that transcends physical death. Embracing death as a natural and shared human experience enables more compassionate, participatory, and contextually grounded care at life’s end.

Limitations

This study presents several limitations. The sample of palliative care patients was relatively small and drawn exclusively from a highly urbanized region of Mexico, which may limit the transferability of findings to rural or underserved settings, where dying at home is often the only viable option. Interviews were conducted in the presence of members of the multidisciplinary care team, potentially influencing participants’ responses. Privacy was occasionally compromised due to spatial constraints within patients’ homes. All stages of qualitative analysis – including interviewing, transcription, coding, and interpretation – were conducted by a single researcher, introducing the possibility of interpretive bias. Participants did not review their transcripts, which may affect the confirmability of findings. Nonetheless, this study offers an important exploratory contribution to understanding stakeholder perspectives on Dignified Death in Latin America and underscores the need for broader, inclusive research across diverse care contexts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Salud en tu casa program of the Mexico City Ministry of Health for its support in facilitating this research. The authors acknowledge the support of the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), Mexico, through a graduate scholarship awarded to Susana Ruiz-Ramírez (CVU: 479376).

Author contributions

None.

Funding

Susana Ruiz-Ramírez is a PhD student in Psychology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and recipient of CONACYT fellowship number 479376. The funder didn’t influence the results of the study despite author affiliations with the funder.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Mexico City Ministry of Health (registry number 101-101-01-19) and by the National Bioethics Commission (registry number CONBIOETICA-09-CEI-004-20280213).