Introduction

Why does collaboration among competitors persist as industries formalise? Rather than a temporary response to early uncertainty, collaboration in many peer-based sectors becomes normative. This paper examines the U.S. artisanal cheese industry to show how collaborative practices emerge, stabilise, and adapt as uncertainty changes. Despite rising competition and regulation, U.S. cheesemakers continue to share knowledge and uphold a collaborative identity (Light, Reference Light2014; Muro & Katz, Reference Muro and Katz2011; Paxson, Reference Paxson2013). The question is not if collaboration lasts, but when and how it becomes institutionalised.

Institutions, both informal (habits, norms) and formal (rules, standards), do more than constrain behaviour; they guide actors in judging which coordination logics are appropriate (Vatn, Reference Vatn2009). This paper proposes a four-stage heuristic linking different types of uncertainty to distinct coordination mechanisms. The framework is particularly relevant in peer-based industries (producer communities where learning, legitimation, and quality control are organised horizontally through producer-to-producer ties rather than top-down hierarchy). In such contexts, collaboration cannot be mandated from above; it must be sustained through shared meaning, trust, and moral commitment.

By tracing how shifting uncertainty foregrounds particular coordination logics, I show that collaboration is not merely a transitional strategy but an informal institution, i.e., a durable, embedded mode of coordination, reinforced by habit, identity, and meaning. The claim is supported by a mixed-methods analysis of the U.S. artisanal cheese industry (1975–2018), combining interviews, social network analysis, and archival sources to track the evolution of collaborative norms across four cohorts.

Institutions, uncertainty, and the evolution of collaboration

This study answers calls to clarify how coordination logics (the patterned ways actors achieve alignment) operate under different forms of uncertainty (Dequech, Reference Dequech2006; Vatn, Reference Vatn2009). It adopts the Veblenian strand of Original Institutional Economics (OIE), which views institutions as socially embedded patterns formed through meaning, moral commitment, and habituated behaviour (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2004). Following North (Reference North1990), I distinguish institutions from organisations; consistent with OIE, habituated norms count as institutions (e.g., the American Cheese Society (ACS) is an organisation; ‘open-door mentoring’ is an informal institution; ACS certification is a formal institution). In what follows, institutionalisation refers to recurrent practices becoming taken-for-granted and normatively embedded, whereas formalisation denotes codification into explicit rules or governance structures. Informal institutions can predate and coexist with formal ones; transition is neither automatic nor one-way.

Veblen’s instinct of workmanship (Veblen, Reference Veblen1898a, Reference Veblen1914), a human propensity for skilled, honest, and socially meaningful labour, is central to this argument. In craft industries where quality and reputation are inseparable (Fine, Reference Fine2003), this instinct aligns identity and moral valuation first; any efficiency gains are derivative. Veblen has been criticised as impressionistic (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2017), yet his view fits evidence from cognitive science on imitation, tool use, and norm internalisation (Cordes, Reference Cordes2005). These capacities underpin shared standards and moral legitimacy in communities of practice. Following Sennett (Reference Sennett2012), collaboration arises via mutual recognition and moral affirmation rather than calculation (see also Knack, Reference Knack2003). These mechanisms explain how norms emerge and take root through repeated enactments of ‘good work done in good faith’ (Veblen, Reference Veblen1898b, Reference Veblen1914), where OIE has the greatest explanatory leverage.

An evolutionary lens complements Bowles and Gintis (Reference Bowles and Gintis2011), who show how reciprocity and social norms coevolve with competition: altruistic punishment and moral reciprocity can stabilise cooperation under pressure. Combining these micro-foundations with OIE’s account clarifies why, under radical and relational uncertainty, identity-based coordination logics tend to emerge first, with formal mechanisms arriving later to codify and scale them.

Accordingly, OIE and NIE differ ontologically but are analytically complementary across coordination contexts: OIE clarifies norm emergence and internalisation; NIE clarifies stabilisation and scaling once practices are codified via rules and incentives (Coase, Reference Coase1937; North, Reference North1990; Williamson, Reference Williamson1985). Although strands of NIE engage cognitive or symbolic elements (Denzau & North, Reference Denzau and North1994; Frolov, Reference Frolov2024; Petracca & Gallagher, Reference Petracca and Gallagher2020), its core emphasis remains on incentives, monitoring, and equilibrium outcomes (Dequech, Reference Dequech2006). Taken together, the preceding arguments imply that different coordination logics become salient as uncertainty shifts. I therefore propose a four-stage uncertainty heuristic that clarifies when OIE has greater leverage (emergence and reproduction) and when NIE becomes more informative (codification and scaling).

A four-stage uncertainty heuristic

Under radical uncertainty, actors cannot assign probabilities or anticipate consequences (Keynes, Reference Keynes1937; Knight, Reference Knight1921), as in the early U.S. artisanal cheese period without templates, codified practices, or reliable market demand (Paxson, Reference Paxson2013). The problem is definitional: what counts as good work? Judgement, moral orientation, and shared narratives dominate (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Bilovich and Tuckett2022; Kay & King, Reference Kay and King2020). Improvisation, imitation, and repetition sediment into provisional routines through public practice and broad, non-selective sharing, with validation coming from ‘Does this seem to work?’ rather than who endorses it (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2015). Applying transaction-cost models built for stable expectations risks explanatory failure (Lawson, Reference Lawson1997; Pagano & Vatiero, Reference Pagano and Vatiero2015). Collaboration here is meaning-driven discovery; efficiency gains are downstream.

As interaction deepens, relational uncertainty replaces epistemic doubt: the problem shifts to who shares my standards? Expectations form through selective repeated interaction, symbolic alignment, and a bounded shared identity; habits plus peer affirmation stabilise norms (Molm et al., Reference Molm, Schaefer and Collett2009). Visible signals of commitment, such as mentorship invitations, open-door access, and peer learning, function as screens in a moral economy (Drakopoulou Dodd & Wilson, Reference Drakopoulou Dodd and Wilson2018; Sennett, Reference Sennett2012), gaining force through enactment rather than design (Veblen, Reference Veblen1909). In NIE terms, reputation starts to substitute for monitoring; in OIE terms, moral expectations now organise with whom collaboration is appropriate.

As an industry expands, coordination uncertainty becomes dominant, and the issue becomes alignment without hierarchy. Unlike NIE’s ‘strategic uncertainty’, which presumes calculated behaviour under known payoffs (Aoki, Reference Aoki2007), loosely coupled peer networks rely on shared meaning, deliberation, and communicative action (Vatn, Reference Vatn2009; Voigt, Reference Voigt2018). Informal institutions act as interpretive devices, signalling applicable norms and expectations (Vatn, Reference Vatn2009). Routines, shared language, and intermediary organisations enable system-wide alignment without displacing the collaborative ethos. Rule-based mechanisms (e.g., certification, incentive schemes) characteristically codify rather than generate these patterns (Long & Driscoll, Reference Long and Driscoll2008); this is the domain where NIE has greater explanatory leverage.

The final form, norm durability, concerns persistence through generational turnover, formalisation, and shocks. OIE emphasises endurance via habituation, taken-for-grantedness, and identity congruence (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2004; Veblen, Reference Veblen1914). Durability depends on peer affirmation, legitimacy, and internalised logic. While NIE highlights monitoring and sanctions, this study underscores the identity-driven reproduction of institutional order (Vatn, Reference Vatn2009).

This typology reinforces the paper’s central claim: peer-based collaboration is a durable institutional form rooted in workmanship, not merely a transaction-cost response. OIE illuminates emergence and reproduction; NIE clarifies scaling and codification. Their relevance shifts with the dominant uncertainty and coordination logic.

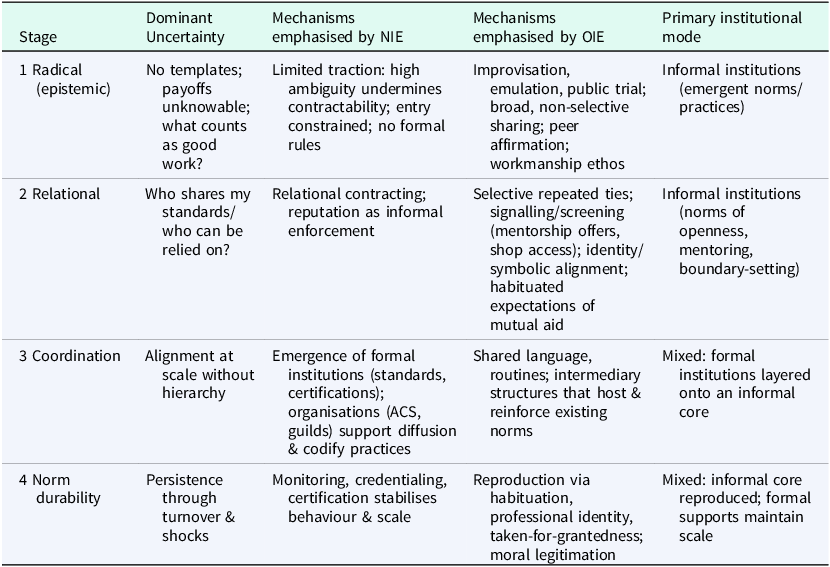

The four-stage framework is interpretive, not deterministic or strictly chronological. New entrants may face Stage 1 conditions in a field structured by Stage 4 institutions. The model highlights the coexistence of moral and strategic motivations and illustrates how informal coordination and formal governance interact over time (Frenken, Reference Frenken2014). Table 1 summarises uncertainty type, coordination logic, and the relative explanatory roles of OIE and NIE.

Table 1. Evolving coordination logics under uncertainty

Stage 1: Discovery through improvisation

In the 1970s and 1980s, U.S. artisanal cheesemakers operated under radical uncertainty: there were no shared standards, few market signals, and limited formal support. While NIE predicts significant barriers to entry in the absence of governance mechanisms (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985), these were often overcome through peer validation and visible commitments to quality. Many early actors were self-taught or learned through trial and error, pursuing cheesemaking as a lifestyle choice or form of subsistence rather than market optimisation. Despite this heterogeneity, a recognisable ethos emerged, marked by experimentation, mutual recognition, and informal learning (Sennett, Reference Sennett2012).

Stage 2: Relational emergence through identity

As the producer community expanded, relational uncertainty became more salient. Producers sought moral alignment and reputational compatibility rather than formal contracts, converging on selective, repeated ties and using visible signals (mentorship invitations, shop access) as screens. Events such as goat shows and associations like the American Dairy Goat Products Association served as organisational venues that hosted and amplified informal institutions (norms of openness, mutual aid) for signalling values and building trust. These early informal institutions enabled geographically dispersed producers to forge identity-based belonging and expectations of mutual aid. Over time, these practices laid the groundwork for institutionalised norms and social capital formation (Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2004), establishing early boundary-setting that distinguished insiders committed to shared standards from casual participants.

Stage 3: Consolidation through infrastructure

By the early 2000s, the industry experienced growth in support infrastructure through organisations such as the ACS, the Vermont Institute for Artisan Cheese, and regional guilds. Coordination uncertainty became the dominant concern: how to maintain alignment and standards across a decentralised, expanding network. While formal institutional mechanisms such as certification and technical assistance emerged (Hansmann, Reference Hansmann1996), they largely codified norms already sustained through informal institutions of peer exchange and moral commitment (Long & Driscoll, Reference Long and Driscoll2008). The formal institutions functioned as interpretive structures, reinforcing rather than replacing the collaborative ethos (Sacchetti & Tortia, Reference Sacchetti and Tortia2024).

Stage 4: Reproduction through professionalisation

As the industry’s legitimacy solidified, the key challenge shifted to sustaining collaborative norms amid generational turnover and increasing specialisation. Professional identity gradually replaced interpersonal mentoring as the basis for recognition. Practices such as knowledge-sharing and open networks were adapted into more formal mechanisms, including technical standards and credentialing systems, without displacing the underlying informal institutions of collaboration. While NIE emphasises enforcement and incentives, OIE better explains how habituated behaviours, identity alignment, and reputational affirmation support institutional persistence. This reflects a path-dependent process (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000): early moral commitments generated social capital, which in turn reinforced collaboration as an expected and valued behaviour.

Social capital as an outcome

Rather than a pre-existing stock (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993), social capital emerges through repeated enactments of shared norms. In a Veblenian view (Reference Veblen1909), trust is the residue of ‘good work done in good faith’, produced through mentorship, peer evaluation, and visible commitment to quality (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Kogut and Shan1997). In this framing, collaboration is an informal institution (a stable norm) before it is a measurable stock of social capital; formal institutions may later codify and scale it. This framing avoids the circularity of ‘trust causes collaboration’ and supports the claim that collaboration can precede measurable trust: value-laden practice generates recognition first, with measurable trust consolidating only after repeated interaction (Chiveralls, Reference Chiveralls, Edwards, Franklin and Holland2006; Veblen, Reference Veblen1909). In cohesive craft industries, social capital signals normative belonging, often distinguishing insiders from outsiders (Uzzi, Reference Uzzi1997), rather than functioning as a generic lubricant. Attempts to engineer trust via incentives alone falter when they bypass moral legitimation. This interpretation aligns with Knack and Keefer’s (Reference Knack and Keefer1997) distinction between Putnamian and Olsonian group dynamics: civic, inclusive associations (Putnamian groups) tend to generate robust social capital and enhance collective economic performance, whereas exclusive, rent-seeking associations (Olsonian groups) can constrain cooperation and economic outcomes.

Collaboration and cooperation are not interchangeable. In this paper, collaboration (Sennett, Reference Sennett2012) is informal, affective, identity-based coordination rooted in mutual recognition; cooperation (North, Reference North1990; Williamson, Reference Williamson1985) is strategic alignment formalised through shared rules or contracts. In the U.S. artisanal cheese industry, collaboration comes first, generating recognition and social capital as an outcome; formal cooperation and codification arrive later. Thus, practices can become stable without yet being formalised.

Data and analytical strategy

This mixed-methods study integrates social network analysis, qualitative interviews, archival narrative analysis, and survey data to investigate the persistence of peer-based collaboration in the U.S. artisanal cheese industry between 1975 and 2018. Consistent with the ontological assumptions of OIE, the study is descriptive and interpretive, treating meaning as constitutive of behaviour. Accordingly, I treat organisations (ACS, guilds) as actors that can host, channel, and codify both informal and formal institutions. Collaboration is examined not merely as a strategic choice but as an expression of evolving institutional norms. Strategic reasoning and efficiency are interpreted as downstream effects, not initial drivers. This supports a sequencing logic in which OIE explains early moral and identity-based foundations, while NIE becomes relevant as norms are codified and formalised.

Expected relationships

Drawing on the four-stage heuristic model, several patterns are expected in the evolution of network structure and learning relationships. These expectations link the transition from moral and identity-driven collaboration to professionalised coordination, showing how evolving forms of uncertainty shape both the structure and function of industry networks.

Under radical uncertainty, collaboration is likely to be improvised and exploratory; peer ties will be broad, non-selective, and weakly clustered. As relational uncertainty takes hold, actors are expected to converge on selective, repeated ties with value-aligned peers, and clustering will begin to rise through boundary-setting and reputational screens. With coordination uncertainty, collaborative norms are anticipated to consolidate into localised, densely connected clusters: later entrants will show tighter clustering and greater geographic concentration, with highly clustered structures coinciding with regional ecosystems rather than diffuse peer networks.

As professionalisation and institutional support expand, knowledge exchange is expected to increasingly flow through formal channels, while collaboration persists as an informal, identity-legitimating norm. Accordingly, later entrants are expected to rely less on direct peer mentorship as learning and legitimacy shift to organisations, training programmes, and professional associations. Among actors who continue to invest in peer-based collaboration, more diverse, lower-density egocentric networks and greater bridging capacity are expected than those embedded primarily in institutionalised structures.

While OIE offers a behavioural and moral framework for understanding how collaboration becomes institutionalised, social network analysis (SNA) provides complementary insight into its structured reproduction. In this study, networks are not treated as neutral conduits of information but as relational expressions of evolving institutional norms. Features such as clustering, centrality, and localisation are interpreted as indicators of how moral economies become embedded over time (Bogenhold, Reference Bogenhold2013; Voigt, Reference Voigt2018). This lens also reinterprets the role of brokers. Rather than exploiting structural holes for personal advantage (Burt, Reference Burt1992), brokers in peer-based industries function as stewards of shared purpose, diffusing values, reinforcing identity, and maintaining the moral infrastructure of collaboration. This perspective contributes to regional innovation systems (RIS) literature by adding theoretical depth to what are often functionally described networks (Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, Uranga and Etxebarria1997). Together, OIE and SNA illuminate how structure and meaning co-evolve.

The U.S. artisanal cheese industry offers an ideal case due to its grassroots origins, sustained peer collaboration, and limited formal governance during early development. The analysis focuses on horizontal producer-to-producer ties, excluding vertical relationships with distributors or retailers. Four analytically defined waves of entry, based on a typology developed by industry analyst Thorpe (Reference Thorpe2009), structure the analysis: artisanal re-emergence (1975-89); network formation (1990-99); infrastructure development (2000-09); and professionalisation (2010-18).

I triangulate four sources: (1) a link-trace (snowball) network of U.S. artisanal cheesemakers and support organisations (536 nodes; 1,326 ties) based on verifiable professional interactions (Goodman, Reference Goodman1961; Robins, Reference Robins2015); (2) a 2018 ACS survey (204/993 responses); (3) 26 semi-structured interviews (2016–2018) across six states; and (4) archival materials (trade press, public interviews, field notes). Network boundaries were relationally defined to include only documented, traceable ties (mentorship, co-projects, co-teaching, organisational collaboration). Relationships are treated as persistent once established, and networks are analysed by cohort to capture structural evolution across four entry periods. Snowball sampling proceeded until two successive waves yielded no new unique actors (boundary closure), emphasising interpretive validity rather than exhaustive enumeration (Goodman, Reference Goodman1961; Robins, Reference Robins2015).

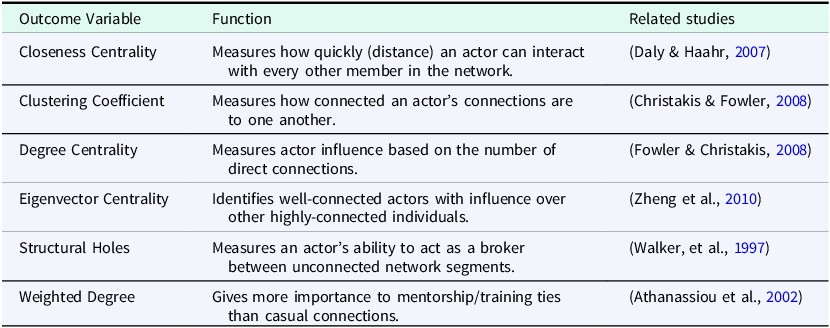

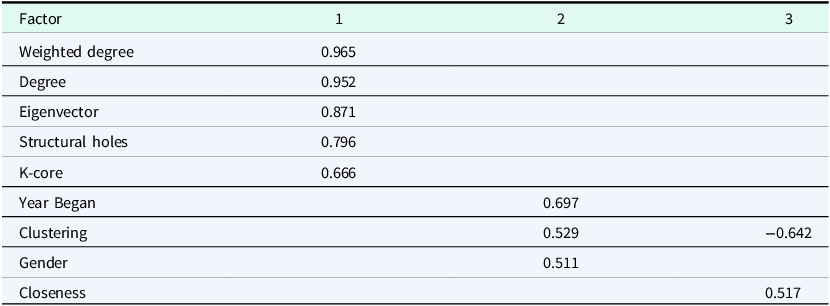

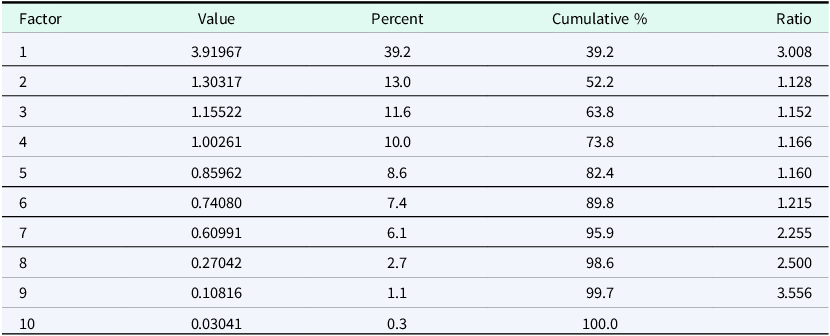

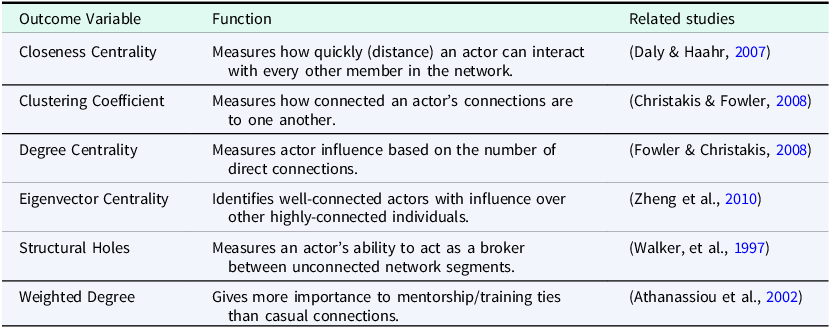

Structural metrics (e.g., clustering, eigenvector) and permutation regressions capture longitudinal change (see Table 2). Principal component analysis (PCA) summarises metric covariation and was not used to test hypotheses directly (Olawale & Garwe, Reference Olawale and Garwe2010). Qualitative coding (NVivo) combined deductive frames with inductive OIE-consistent mechanisms (habituation, peer affirmation, moral framing). All data were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a historically bounded yet analytically rich view of institutional development.Footnote 1

Table 2. Outcome variables to estimate and compare structural and relational social capital

Institutional evolution in the U.S. artisanal cheese industry

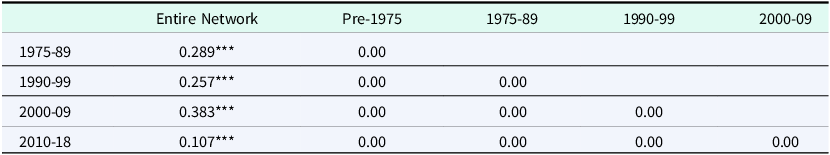

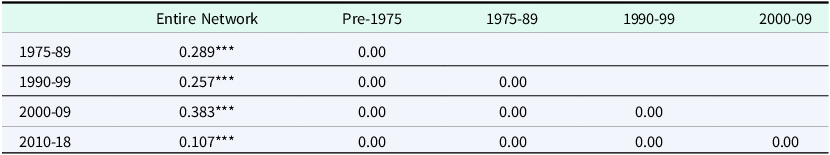

For each period, a static subgraph was constructed that included only ties among cheesemakers who entered during that specific window. These cohort-specific networks were built from public records, interviews, and archival sources. To assess structural distinctiveness, the quadratic assignment procedure (QAP) (Krackhardt, Reference Krackhardt1988) was used to compare each cohort’s tie structure to others and to the full network. As shown in Table 3, correlations between cohorts are low, indicating distinct relational patterns. However, each cohort remains significantly correlated with the full network, suggesting structural autonomy embedded within a broader collaborative architecture and a layered institutional structure.

Table 3. Cohort correlation test results

***p < 0.001.

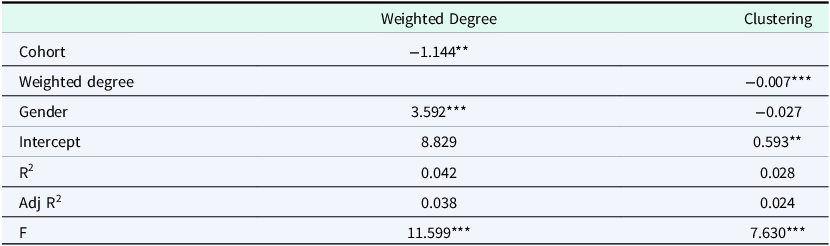

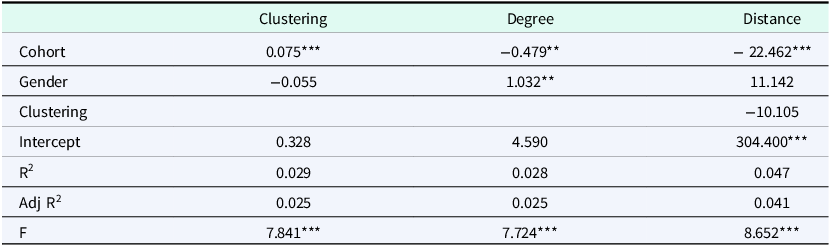

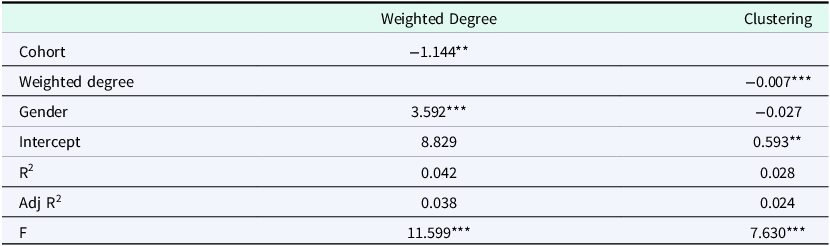

Women disproportionately shaped early collaborative practices in the first two cohorts (1975-89 and 1990-99). Quantitatively, women show higher degree centrality (β = 1.032, p < 0.01) and weighted degree (β = 3.592, p < 0.001) (Table 4), indicating broader and deeper relational investment (Kim, Reference Kim2019; Phalen, Reference Phalen2010). Qualitative accounts echo this pattern, producing a gendered founder effect that institutionalised mentorship and mutual aid (Nelson, Reference Nelson2003). As one cheesemaker observed: ‘…the early, early, pioneers in cheesemaking in America…Just generous and inclusive in their whole philosophy. They’re not about getting ahead of their competition, they’re about raising everybody together… There were a lot of women, early on, who set that tone’. PCA (Table 5) reveals associations between gender, centrality, and entry time, consistent with a Veblenian account of institutions as cumulative enactments of shared moral purpose.

Table 4. OLS regression coefficients for relational social capital hypotheses

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 5. Related component matrix

Cohort narratives

The earliest cohort of artisanal cheesemakers (1975–1989) entered the field with no templates, standards, or market expectations. Their behaviour reflected what Veblen might describe as survival-driven experimentation, rooted in craft ethos and moral purpose. With few peers to consult, cheesemakers relied on informal mutual aid. Coordination was public and non-selective, with open exploratory sharing and provisional routines validated by ‘what seemed to work’, rather than by who endorsed them. Women in this cohort faced not only technical and market uncertainty but also social scepticism. Allison Hooper recounted: ‘…it was difficult for me, in this industry, to gain credibility as a young woman. Particularly making a very unconventional product … the farmers in our valley were so skeptical…they were so certain we would go out of business’. (Fratini, Reference Fratinin.d.)

Despite these challenges, collaborative problem-solving and shared learning became the norm, laying the groundwork for recognition-based expectations of peer support.

As artisanal cheese production expanded, peer interactions within the second cohort (1990–1999) translated recognition and shared purpose into observable trust as cheesemakers increasingly identified with one another as a community. One producer described a defining ethos: ‘Where I can walk into [Cheesemaker 17’s] and say, ‘Hey, I need to wax some cheese because I know you’ve got wax pots and I don’t.’ ‘Okay, come on over.’ That type of stuff is who we are… You try to help your neighbor… and they’ll help you back’. (Cheesemaker 20)

These accounts reflect the institutionalisation of a collaborative identity through shared standards and habitual acts of mutual aid.

By the early 2000s, industry growth and regulatory complexity increased the need for formal coordination. Yet even as NIE-style tools like certification and contracts emerged, identity-based collaboration remained strong. This phase was marked by institutional layering: formal structures reinforced rather than displaced informal norms. Organisations like the Vermont Cheese Council didn’t introduce collaboration; they codified and supported pre-existing moral logics: ‘…the open-door policy, you know? That’s who we are’. (Cheesemaker 20)

Despite continued scaling and formalisation, peer-based collaboration persisted among new entrants between 2010 and 2019, though often in more structured forms. This stage centred on identity alignment and moral legitimation, even as mentorship moved toward institutional channels: ‘Because we’re all doing it together there is this sense of community and collegiality, where we can talk to one another, face problems, and figure out solutions together’. (Kramer, Reference Kramer2019)

What began as necessity-driven improvisation evolved into a professionally expected, morally reinforced mode of conduct. Early quotes exemplify Stage 1 discovery (open, non-selective sharing), whereas the 1990s narratives show Stage 2 boundary-setting via selective, repeated ties and reputational screening.

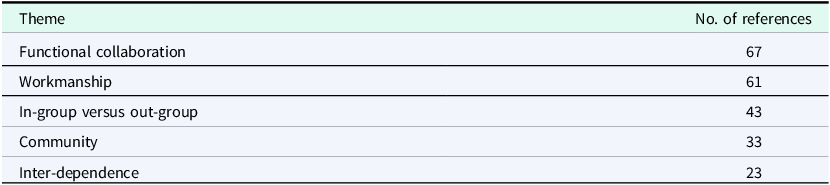

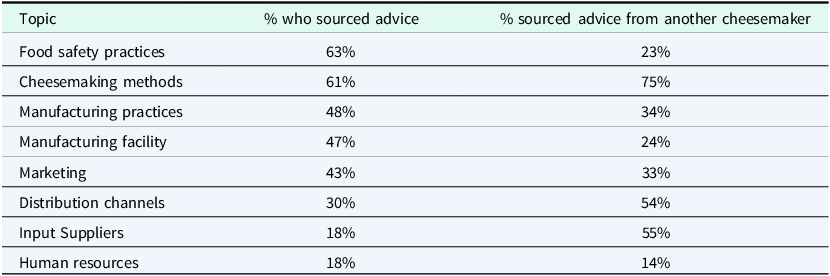

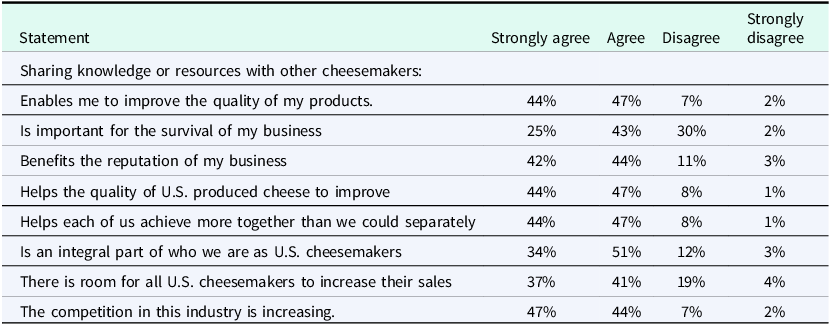

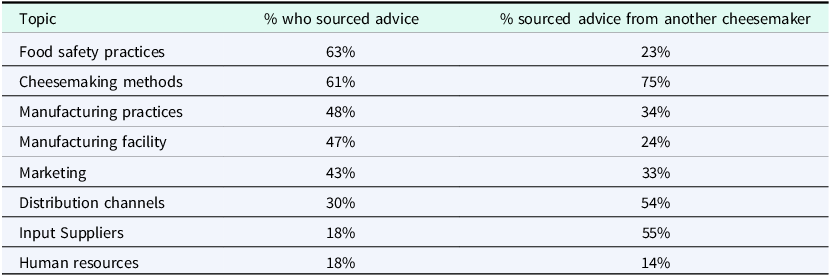

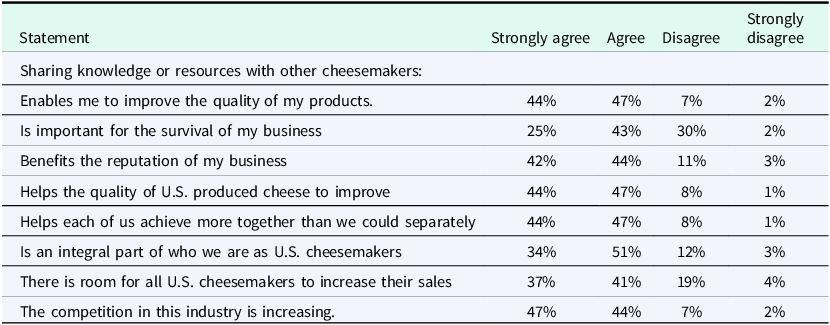

Survey and interview data reinforce the persistence of peer-based collaboration, even as the U.S. artisanal cheese industry has matured. Table 6 shows that ‘functional collaboration’ and ‘workmanship’ remain dominant themes in open-ended responses. Table 7 indicates strong peer reliance for both cheesemaking methods and distribution channels. Table 8 reveals that over 90% of respondents believe knowledge-sharing improves product quality, and 85% consider it integral to their professional identity, even amid rising competition.

Table 6. Secondary thematic analysis results

Table 7. Survey data results regarding role of social networks N = 181

Table 8. Survey data results regarding motivations for maintaining personal connections N = 181

These results suggest that collaborative norms have become durable and expected, even in an increasingly competitive environment:

‘We’re not competitors with each other. We’re all in the same boat, and the enemy is standardization’. (Cheesemaker 22)

‘I see them as my competitors, I know they’re my competitors, but I don’t feel competitive towards them’. (Cheesemaker 7)

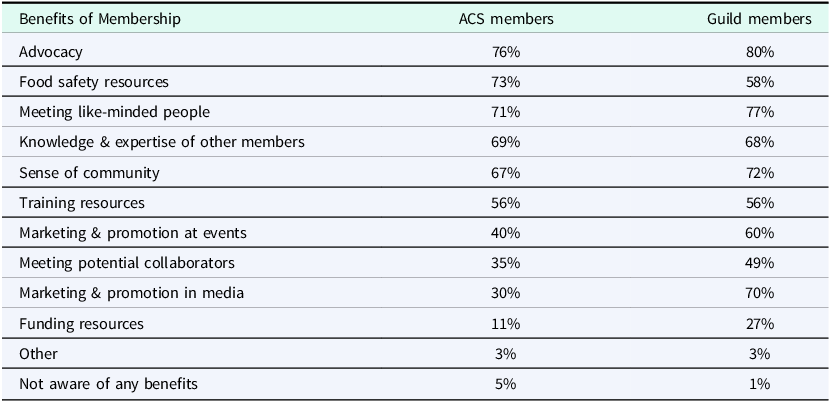

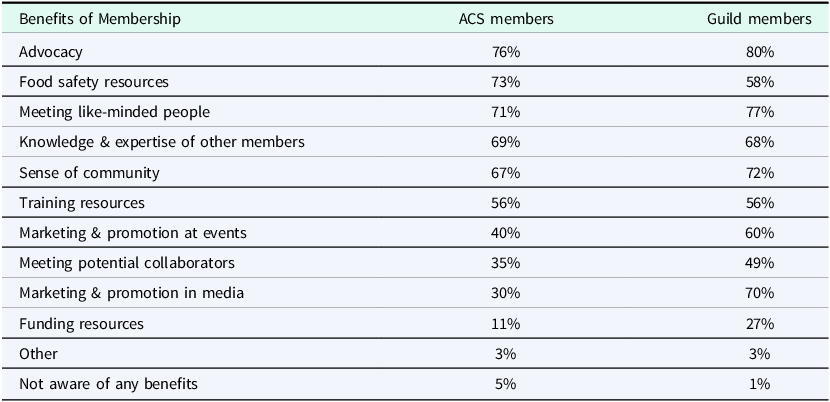

Table 9 shows that organisations like ACS now serve dual roles: functional (e.g., training, certification, advocacy) and relational (e.g., community-building, peer exchange). Survey data reveal high rates of community-based benefits among guild members, indicating that strategic cooperation is layered atop a deeply moral collaborative architecture.

‘I’ve often wondered why the artisan cheese industry feels so much more welcoming than many other kinds of businesses. There is a strong sense that collaboration is not only welcome but expected. I also belong to the Specialty Food Association…that organization hasn’t been anywhere near as welcoming and has not offered as many resources as the American Cheese Society’. (Cheesemaker 7)

Table 9. Survey data results regarding perceived benefits of formal networks N = 181

The analysis of network evolution focuses on how the structure of collaboration changed as the industry moved from the early improvisational phases of development toward the more coordinated and institutionally durable stages described in the theoretical model. As collaborative norms became more established, it was expected that networks would exhibit greater clustering, fewer overall peer connections, and stronger geographic localisation. These patterns are consistent with the consolidation of identity-affirming norms within bounded communities rather than the expansion of opportunistic exchange.

Regression analyses support these expectations. Results show increasing clustering (β = 0.075, p < 0.001), fewer total ties (β = −0.479, p < 0.01), and more localised connections (β = −22.462, p < 0.001) (Table 10). These findings indicate that later entrants formed denser, more geographically concentrated clusters, reflecting institutional sedimentation rather than efficiency-seeking realignment. The modest R2 values (R² = 0.028–0.047) are unsurprising given the heterogeneous behaviour and complex interdependence characteristic of social networks. The purpose of the analysis is not prediction but to detect directional trends consistent with institutional sedimentation.

Table 10. OLS regression coefficients for structural social capital hypotheses

**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

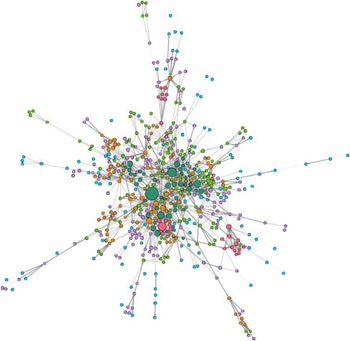

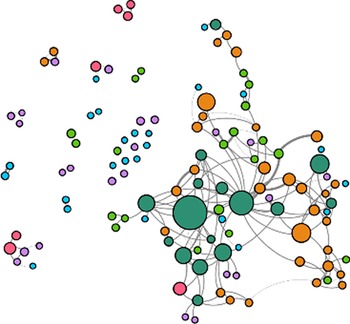

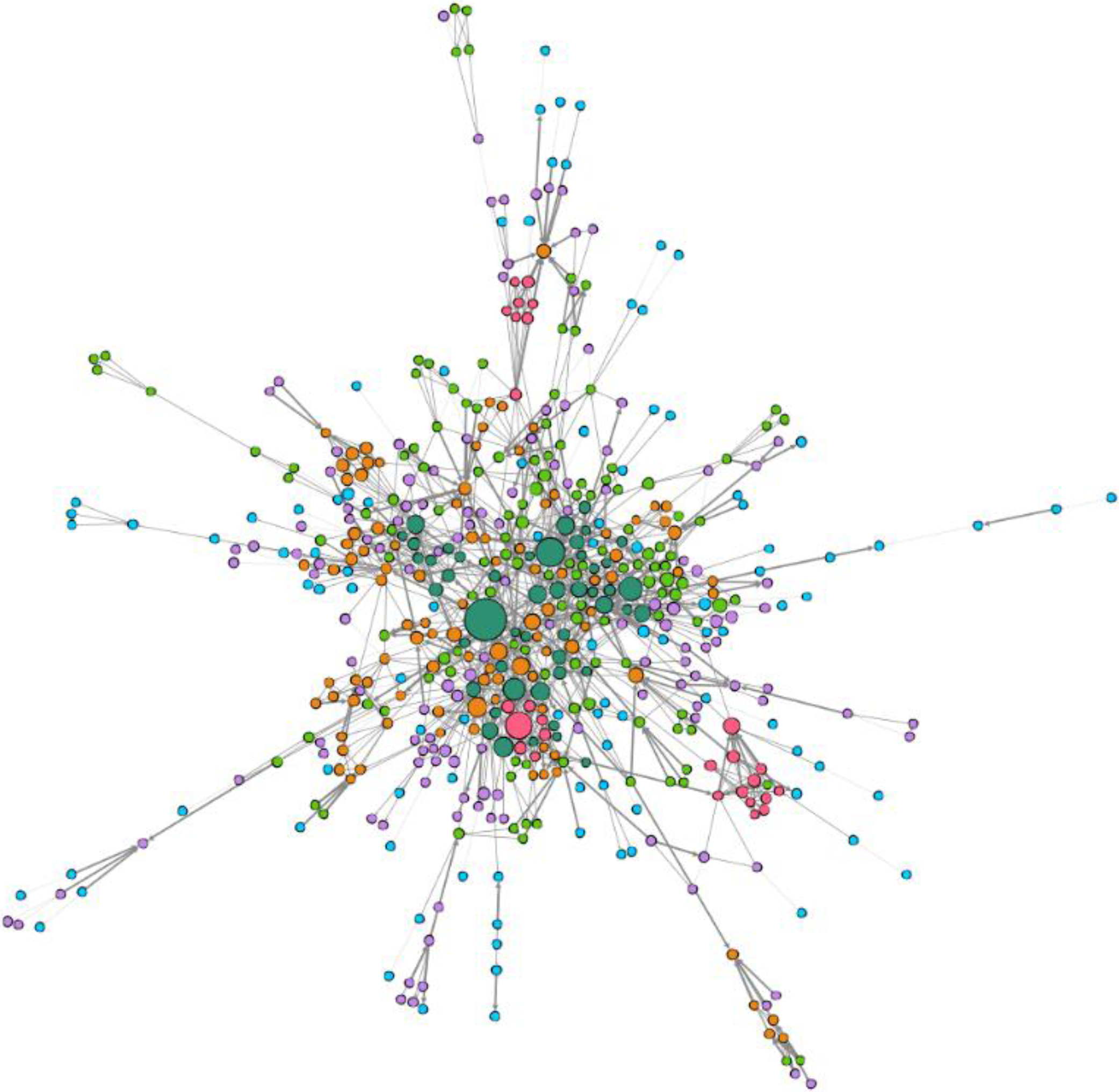

K-core analysis confirms a persistent core-periphery structure (Figure 1) (Borgatti & Everett, Reference Borgatti and Everett2000). Core actors (k-core 5; dark green) function as embedded knowledge gatekeepers, while peripheral actors (k-core 1; light blue) maintain looser, often dyadic ties. Some subgroups (k-core 6; pink) appear internally cohesive yet remain less integrated into the network core.

Figure 1. Connectedness of the entire network by k-core.

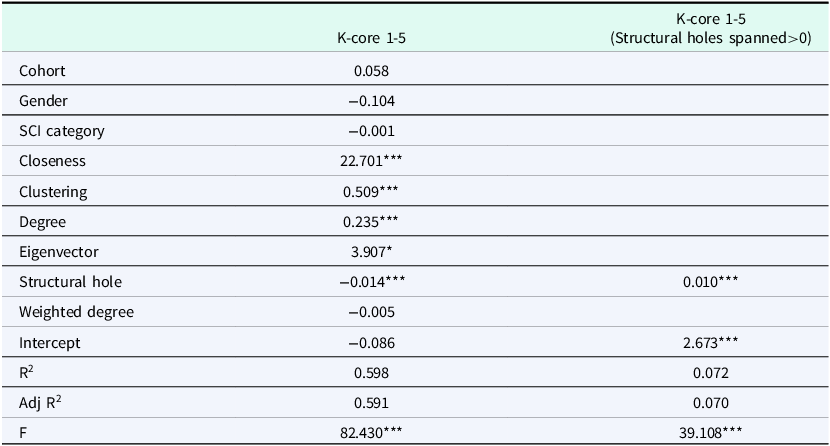

Permutation regression (Table 11) confirms that higher eigenvector centrality and closeness significantly predict core membership, reinforcing the influence of dense, central clusters. Broking also plays a key role: while brokers are generally less central (β = −0.014, p < 0.001), those with more bridging ties are more structurally influential (β = 0.010, p < 0.001). Together, these results suggest that localised, cohesive cores coexist with strategically positioned brokers who sustain the network’s integrative capacity. In other words, as collaborative norms become institutionally durable, differentiation emerges between embedded custodians of shared practice and bridging actors who maintain relational openness across geographic or organisational divides.

Table 11. Permutation based regression results for relationship between variables and network position

*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

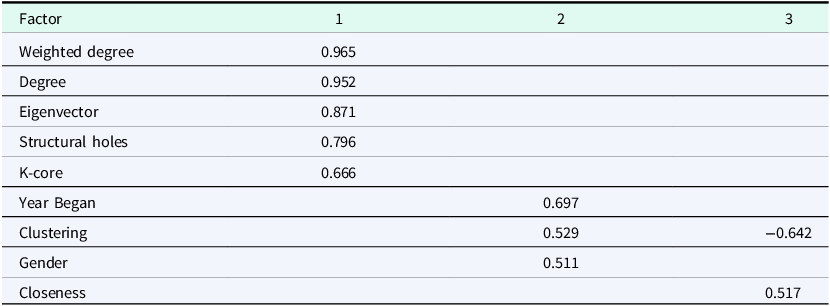

PCA identified four dimensions explaining 73.8% of variance (Table 12). The first (39.2%) corresponds to structural social capital and is dominated by weighted degree, eigenvector centrality, structural holes, and k-core membership. This is an OIE-consistent construct reflecting embeddedness and cumulative relational investment. The second (13.0%), reflecting cohort-related variation, captures temporal differentiation in coordination logics consistent with transitions from OIE-type identity-based collaboration toward NIE-type formalisation. Subsequent components primarily serve to illustrate structural trade-offs (e.g., local cohesion vs. reach). Thus, the PCA results complement rather than test the theoretical model, offering a descriptive synthesis of the patterns predicted by the uncertainty typology and associated hypotheses.

Table 12. Principal component analysis and total variance

As the field professionalised, learning shifted from open peer mentorship to institution-mediated channels. Later cohorts formed fewer mentorship ties (β = −1.144, p < 0.01) and were less embedded in the broader network (β = −0.007, p < 0.001), indicating a transition from open peer learning to selective invitations that function as identity screens. Mentorship persisted more as identity reinforcement than skill acquisition, with acceptance increasingly requiring visible commitment and competence.

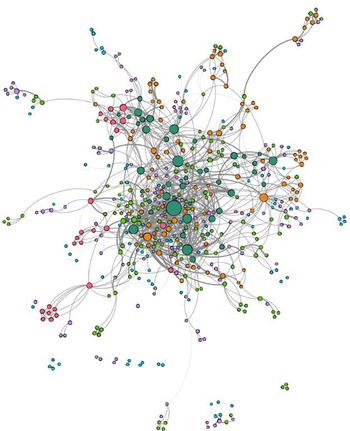

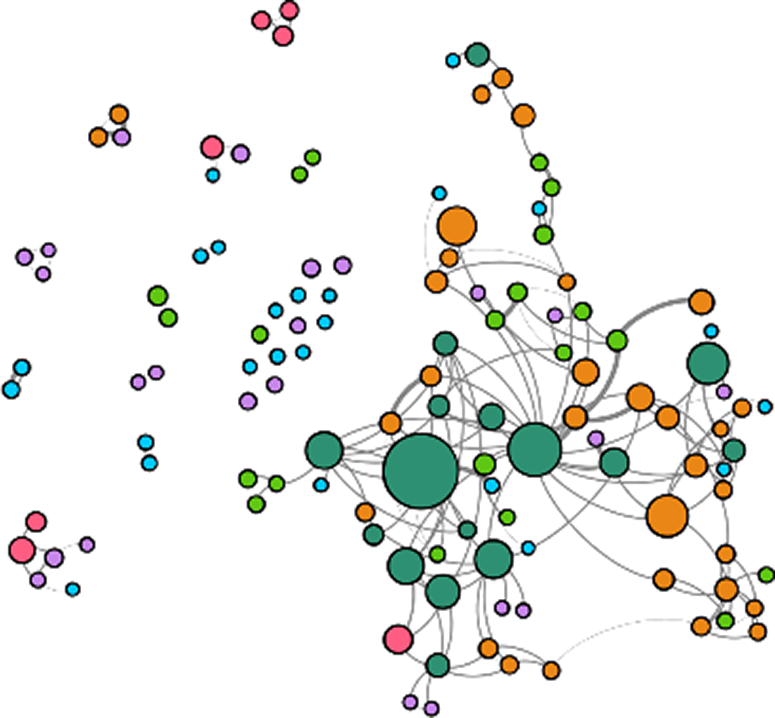

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate this structural shift. In 1989, the full network of U.S. artisanal cheesemakers was relatively egalitarian and dispersed, characterised by numerous dyadic and triadic clusters that reflect spontaneous mentoring and reciprocal learning, hallmarks of the early stages shaped by radical and relational uncertainty. By 2018, the network had become denser, more centralised, and more differentiated. Core actors maintained high connectivity, but the relational pathways of learning shifted from peer-to-peer mentorship to institutionally organised forms of training and information diffusion.

Figure 2. U.S. Artisanal cheese industry network, 1989.

Figure 3. U.S. Artisanal cheese industry network, 2018.

This evolution aligns with the broader pattern of institutional consolidation observed throughout the study. As collaboration became routinised and embedded in professional norms, its original learning function gave way to a legitimising one. Mentorship persisted, but primarily as a mechanism for reinforcing identity and shared standards rather than for building foundational skills. Several new producers described the need to demonstrate commitment and competence before being fully accepted into established circles: ‘…they’ll help you in the very, very beginning, but they’re like guarded secrets… there had been cheesemakers that would start up and not last…I think that we just had to prove that we’re in it’. (Cheesemaker 14)

Discussion and conclusion

I examined how collaboration among competitors persists as an industry matures, formalises, and becomes more competitive. To interpret these dynamics, I introduce a four-stage heuristic model that traces shifting coordination challenges and logics over time. Rather than confirm a rigid theory, the model invites reflection on how meaning, strategy, and structure co-evolve in institutional development.

Collaboration is often viewed as a fragile feature of early-stage uncertainty or as dependent on incentive alignment. The evidence here shows it became a durable informal institution: habituated, identity-congruent, and morally meaningful, later layered with formal supports in selected domains (e.g., standards, training). OIE best explains this sedimentation; NIE helps explain codification and scaling. Structurally, networks localised and clustered as norms consolidated, while brokers sustained cross-community diffusion without displacing the localised moral economy. Collaboration remains meaningful because it is professionally expected and socially affirmed; strategic benefits are consequential, not causal.

These patterns are consistent with a Putnamian dynamic: workmanship-driven peer groups generate social capital as an outcome, not a precondition. In the U.S. artisanal cheese industry, such ‘P-group’ networks foster collaboration among competitors. Moral legitimacy and trust then crystallise into durable institutions, offsetting collective-action problems typical of ‘O-group’ settings (Knack & Keefer, Reference Knack and Keefer1997). Competition reinforces collaboration because it operates within a moral economy linking reputation, quality, and belonging.

Findings from adjacent industries reinforce this interpretation. In craft beer, communal commitment endures as a normative expectation (Dobrev & Verhaal, Reference Dobrev and Verhaal2024). Affective ties, shared values, and repeated interaction sustain ‘internalised coordination’ (Sacchetti & Tortia, Reference Sacchetti and Tortia2024). A ‘rising tide lifts all boats’ ethos is expressed by both brewers and cheesemakers (Mathias et al., Reference Mathias, Huyghe, Frid and Galloway2018). Other studies (Drakopoulou Dodd & Wilson, Reference Drakopoulou Dodd and Wilson2018; Reid & Gatrell, Reference Reid and Gatrell2017) likewise find that identity-based moral economies underpin durable collaboration that formal governance later codifies without displacing.

Gendered influence

Findings also challenge the notion that institutional norms require formal authority or elite control (Vatiero, Reference Vatiero2017). Women in the 1975-99 cohorts disproportionately initiated the collaborative behaviours that became institutionalised. Marginal in traditional agri-food hierarchies (Botreau & Cohen, Reference Botreau, Cohen and Cohen2020), they shaped the emerging field through mentorship, emotional connection, and peer learning, rather than through positional power. This gendered founder effect illustrates how norms can originate through non-authoritative channels and persist through habituated behaviour.

Integrating analytical perspectives

This study integrates three lenses across the four stages of uncertainty. OIE supplies the behavioural-moral micro-foundations for emergence and reproduction where norms anchored in the instinct of workmanship arise from habituated practice and identity alignment. SNA renders these processes structurally visible, showing a progression from broad, non-selective ties (Stage 1) to localised, dense clusters with brokers (Stages 3-4). NIE explains codification and scaling once norms are established through standards, certification, and incentives that stabilise coordination at scale.

The division of labour is thus: OIE explains why norms take root; SNA shows what that looks like in networks; NIE explains how codified supports maintain scale. Across the stages, coordination moves from discovery to selection to formal alignment and, ultimately, durable reproduction. Formal mechanisms stabilise and scale an already-institutionalised collaborative core rather than generate it.

Two implications follow. First, social capital is an outcome, not a precondition: repeated ‘good work done in good faith’ generates recognition and trust, which later makes formal cooperation tractable. Second, efficiency is derivative: observed gains track the consolidation of an identity-affirming collaborative order rather than cause it. The network evidence (increased clustering and localisation; brokers bridging clusters) is consistent with this sequencing and with embedded, relational authority, including early, gendered contributions, rather than top-down control.

Several limitations remain. The reconstructed network relies on public traces, biasing toward persistent and visible actors (survivorship bias). The findings therefore characterise documented, persistent actors whose behaviours and relationships became part of the recorded institutional record, rather than the entire field of participants. Causal limitations also apply: centrality may reflect success as much as cause it. Finally, the data predate COVID-19, which likely altered patterns of collaboration. Future work should assess how external shocks and generational change have reshaped collaborative norms.

Institutions are moral ecologies as well as governance structures. When rooted in identity and reinforced by habituation and peer affirmation, collaboration can persist among competitors as a self-reproducing norm. Formal rules and organisations can stabilise and scale these patterns, but the motor of persistence remains the informal institution of collaboration grounded in workmanship. In craft-based industries where ‘good work done in good faith’ confers legitimacy, competition does not extinguish collaboration; it coexists within a moral economy that sustains it.