6.1 Introduction

Fashion is not the first industry that comes to mind as depending on patent law. Other, higher-tech industries like semiconductors and pharmaceuticals occupy much more of the time of patent lawyers and judges. Yet every year, large apparel manufacturers apply for and obtain patents, and every year patent offices issue thousands of patents in ‘wearing apparel’, ‘weaving’ and other categories relevant to the fashion industry.Footnote 1 Many of these patents are directed to the sorts of fashion that seem obviously technological or routinely subjected to technological innovation, like athletic wear or watches. Others are directed towards new materials and construction techniques that can be used in a variety of garments. But still more are directed to garments that employ traditional methods of design and construction.

This chapter examines the fashion industry’s uses of utility patents. It first provides an overview of the fashion industry’s patenting activities, looking at how many patents are granted for fashion-related inventions and how large apparel companies obtain those patents (Section 6.2). It then examines companies’ use of patents, looking at how patent litigation in the fashion industry compares to other industries (Section 6.3). Finally, it turns to the uneasy tension in fashion between function and aesthetics, examining the specific technologies and inventions being claimed in fashion patents to see what can be inferred about the relationship between fashion and intellectual property (Section 6.4).

Before we dive in, a quick note on scope. This chapter focuses on utility patents, the type of patent most people think of when they think ‘patent’. Utility patents cover inventions – ‘any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof’, as it is put in US law.Footnote 2 Utility patents are not, however, the only kind of patent; in addition to plant patents (which cover, well, plants), in the United States there are also design patents, which cover ‘any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture’.Footnote 3 Similar rights are protected in other countries under other names, like ‘registered designs’. Whatever the name, design protections are a more conventional fit for fashion, since they can apply to purely aesthetic creations without any showing of utility. Those rights, however, are covered elsewhere in this volume; our focus here will be utility patents only.Footnote 4

6.2 Obtaining Patents: Patenting Fashion Inventions

6.2.1 Patents by Classification

Fashion may not be the most obvious industry to rely on patents, but numerous technologies are critical to the industry. Apparel itself has for centuries reflected technological change; otherwise, today clothing would be made without synthetic fibres, modern dyes or even the sewing machine. Some of these technological developments are relevant to almost every fashion house; consider new fabrics, new fabric dyes and treatments or new methods of construction. Others are specific to market segments like athletic wear or jewellery.

For an initial sense of how important patents are to fashion, we can look at how many patents are granted that appear to relate to fashion. This is not a trivial task, for a few reasons. Patents can at times be written in impenetrable language only occasionally resembling English. Even when read by a patent practitioner, though, it is not always obvious what are the different applications an invention might have. For instance, the original US patent for hook-and-loop fasteners (more commonly known as Velcro) mentioned use as ‘closing devices for clothing, blinds or the like’ but didn’t mention the countless other uses to which Velcro has been applied.Footnote 5 So it is impossible to get a definitive list of fashion-related patents.

Helpfully, the patent offices of different nations have agreed on standard classification schemes that make it possible to filter patents for those related to particular technologies. These classification schemes have numerous limitations: many of the categories are broad, the schemes have changed over the years and they rely on the patent applicant or patent examiner to identify a particular use as a possibility. Perhaps most critically, most patents fall within multiple technology classifications, and the fashion-related classifications may be minor, niche or hypothetical uses of a technology. For instance, US Patent No. 7,627,451, titled ‘movement and event systems and associated methods’, was granted to Apple Inc. in 2009. The patent explains that the invention ‘relates to sensing systems monitoring applications in sports, shipping, training, medicine, fitness, wellness and industrial production’ and includes 76 separate technology classifications, one of which – A43B3/34, for ‘footwear characterised by the shape or the use with electrical or electronic arrangements’ – relates to fashion. If Apple ever made use of the invention covered by this patent, it apparently did not do so in footwear. Yet the patent comes up in a search for patents falling within fashion-related classifications. Still, despite these limitations in using technology classifications and their potential to produce overly broad results, they can provide a helpful overview of fashion-related patenting activity.

To examine fashion-related patenting activity, the most comprehensive classification scheme – the Cooperative Patent Classification, which is maintained jointly by the US Patent and Trademark Office and the European Patent Office – was used to identify technology classifications related to fashion. The CPC contains approximately 250,000 classification entries, which are organised into nine sections (like ‘human necessities’ and ‘physics’) that are divided into classes, subclasses, groups and so forth. Ten classes were identified as being most likely to cover most fashion-related inventions:Footnote 6

A41: Wearing Apparel

A42: Headwear

A43: Footwear

A44: Haberdashery; Jewellery

A45: Hand or Travelling Articles [which includes umbrellas, purses, luggage, handbags, and walking sticks, among other things]

D01: Natural or Man-Made Threads or Fibres; Spinning

D02: Yarns; Mechanical Finishing of Yarns or Ropes; Warping or Beaming

D03: Weaving

D04: Braiding; Lace-Making; Knitting; Trimmings; Non-Woven Fabrics

D05: Sewing; Embroidering; Tufting

Each of these classes contains numerous specific classification entries. For instance, A41, the group covering ‘wearing apparel’, contains six subclasses, including ‘shirts; underwear; baby linen; handkerchiefs’; ‘corsets; brassieres’; ‘outerwear; protective garments; accessories’ and so forth. Each subclass contains dozens of specific classifications like ‘collars with supports for neckties or cravats’, ‘reversible collars’, ‘chemically stiffened collars’ and so forth.

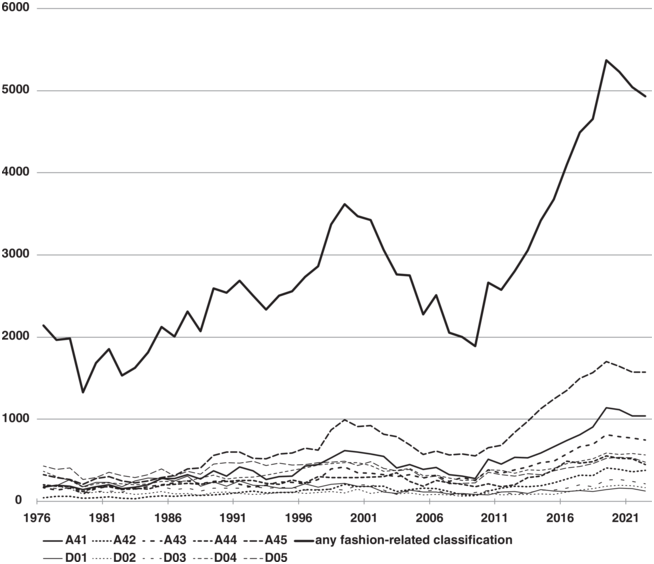

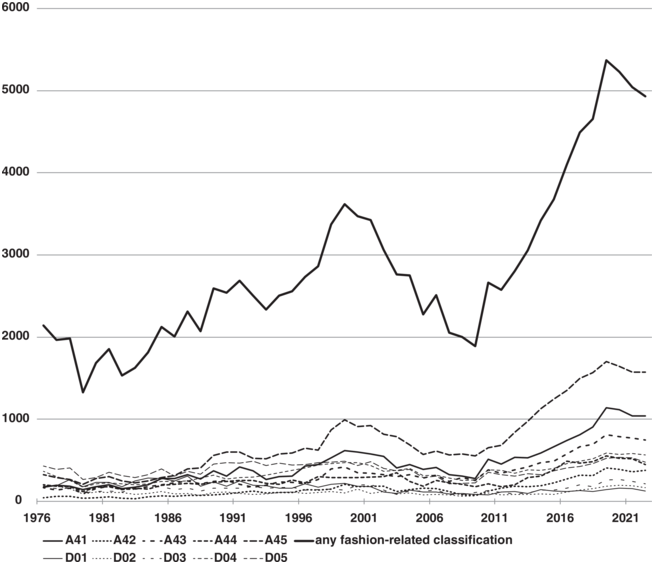

The number of US patents granted each year containing any classification entry falling within one of these ten classes was determined from the US Patent and Trademark Office’s PatentsView database.Footnote 7 The results show a general upward trend in the number of patents granted each year, with recent years showing more than 5,000 patents a year (Figure 6.1):

Figure 6.1 Upward trend in fashion-related patents.Footnote 8

Figure 6.1Long description

The lines represent the A 41, A 42, A 43, A 44, A 45, D 01, D 02, D 03, D 04, D 05, and any fashion-related classification. A 41 through A 45 originates at (1976, 500), (1976, 400), (1976, 300), (1976, 200), and (1976, 100), fluctuates and terminates at (1976, 1700), (1976, 1000), (1976, 800), (1976, 700), and (1976, 600). Similarly, D 01 through D 05 originates at (1976, 300), (1976, 200), (1976, 150), (1976, 100), and (1976, 50), fluctuates and terminates at (1976, 350), (1976, 300), (1976, 250), (1976, 200), and (1976, 100). Any fashion-related classification originates at (1976, 2000), fluctuates in an increasing trend, peaks at (2021, 5400) and drops at (2021, 5900). The values are estimated on the y-axis.

This trend, though, does not appear to be due to any growing importance of patents to the fashion industry. Instead, it appears to track the general growth in the number of patents issued each year, which increased from around 70,000 patent grants (in the United States) in 1976 to around 350,000 in 2020.Footnote 9 Indeed, the proportion of all patents with any classification entry from the ten fashion-related classes has fallen from just over 3% in 1976 to around 1.5% in 2020, suggesting that fashion has relied comparatively less on patents than have other industries over the last four decades.

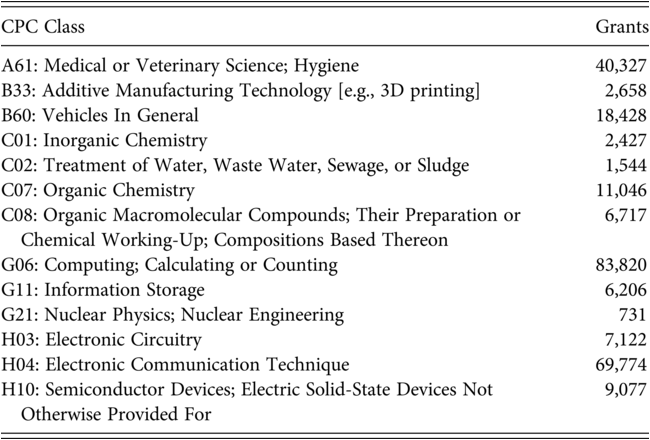

Still, thousands of fashion-related patents a year is not a trivial number; it represents around 100 fashion-related inventions a week. It may seem like a lot for a field that isn’t especially technological. But compare it to the number of patent grants in 2022 in some other technology classes (Table 6.1).

| CPC Class | Grants |

|---|---|

| A61: Medical or Veterinary Science; Hygiene | 40,327 |

| B33: Additive Manufacturing Technology [e.g., 3D printing] | 2,658 |

| B60: Vehicles In General | 18,428 |

| C01: Inorganic Chemistry | 2,427 |

| C02: Treatment of Water, Waste Water, Sewage, or Sludge | 1,544 |

| C07: Organic Chemistry | 11,046 |

| C08: Organic Macromolecular Compounds; Their Preparation or Chemical Working-Up; Compositions Based Thereon | 6,717 |

| G06: Computing; Calculating or Counting | 83,820 |

| G11: Information Storage | 6,206 |

| G21: Nuclear Physics; Nuclear Engineering | 731 |

| H03: Electronic Circuitry | 7,122 |

| H04: Electronic Communication Technique | 69,774 |

| H10: Semiconductor Devices; Electric Solid-State Devices Not Otherwise Provided For | 9,077 |

Many of these classes cover far more patents than the fashion-related classifications. That is not surprising, since some of these classes are quite broad (A61, for instance, covers inventions as varied as surgical techniques, dental implements, veterinary tools, cardiac stents, devices to accommodate the disabled and radiation treatments, among others). But as Table 6.1 shows, even narrowly drawn classes in niche areas like wastewater treatment (C02) and nuclear physics (G21) have similar numbers of patents granted as the fashion-related classes.

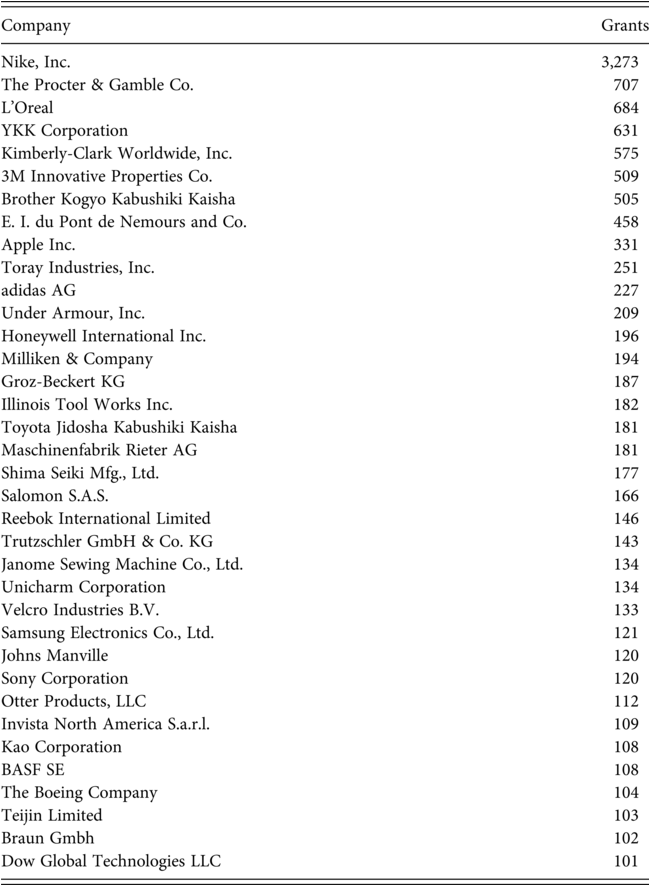

Patents in the fashion-related classes are obtained by a wide array of applicants, ranging from expected firms like fashion houses and manufacturers to individual inventors and firms with no obvious link to fashion. Although patents are issued to inventors – individual humans – rather than companies, most patents are assigned to a company when issued, and that information is listed on the face of the patent. Between 2000 and 2022, 78,212 patents were issued that included one or more fashion-related classification entry, with 36 different firms accounting for 100 or more patents (Table 6.2).

| Company | Grants |

|---|---|

| Nike, Inc. | 3,273 |

| The Procter & Gamble Co. | 707 |

| L’Oreal | 684 |

| YKK Corporation | 631 |

| Kimberly-Clark Worldwide, Inc. | 575 |

| 3M Innovative Properties Co. | 509 |

| Brother Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha | 505 |

| E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Co. | 458 |

| Apple Inc. | 331 |

| Toray Industries, Inc. | 251 |

| adidas AG | 227 |

| Under Armour, Inc. | 209 |

| Honeywell International Inc. | 196 |

| Milliken & Company | 194 |

| Groz-Beckert KG | 187 |

| Illinois Tool Works Inc. | 182 |

| Toyota Jidosha Kabushiki Kaisha | 181 |

| Maschinenfabrik Rieter AG | 181 |

| Shima Seiki Mfg., Ltd. | 177 |

| Salomon S.A.S. | 166 |

| Reebok International Limited | 146 |

| Trutzschler GmbH & Co. KG | 143 |

| Janome Sewing Machine Co., Ltd. | 134 |

| Unicharm Corporation | 134 |

| Velcro Industries B.V. | 133 |

| Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. | 121 |

| Johns Manville | 120 |

| Sony Corporation | 120 |

| Otter Products, LLC | 112 |

| Invista North America S.a.r.l. | 109 |

| Kao Corporation | 108 |

| BASF SE | 108 |

| The Boeing Company | 104 |

| Teijin Limited | 103 |

| Braun Gmbh | 102 |

| Dow Global Technologies LLC | 101 |

In addition to apparel manufacturers, these firms include electronics makers like Apple, Samsung and Sony; consumer-goods makers like Procter & Gamble and Kimberly-Clark; materials and chemical companies like 3M, du Pont and Dow; even large industrial manufacturers like Honeywell and Boeing. Some of these non-fashion firms are patenting inventions with fashion-related applications, like inventions related to the Apple Watch, while others are patenting materials that happen to overlap in the fashion-related technology classes, like novel fabrics for aerospace purposes. Still, the firms listed in Table 6.2 accounted for less than 15% of the fashion-related patents, suggesting that the vast majority of fashion-related patents are issued to small firms, individual inventors and non-fashion firms with a small number of inventions that may peripherally touch on fashion.

Even though other technologies account for far more patents than those related to fashion, there are still thousands of fashion-related patents granted each year, and many of those patents are nevertheless granted to large fashion companies, as discussed in Section 6.2.2.

6.2.2 Large Fashion Firms

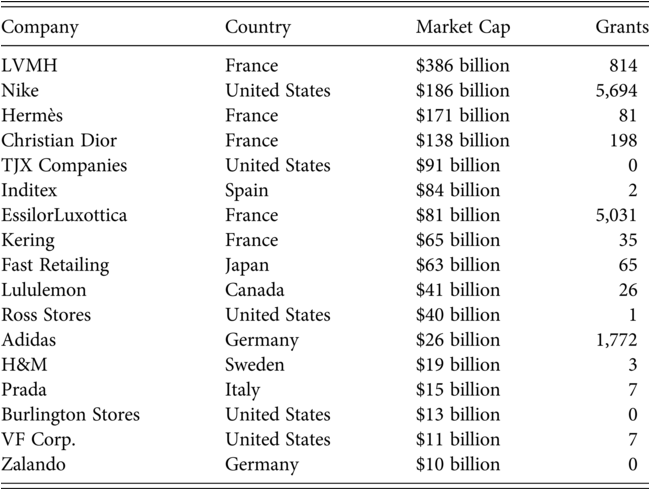

Companies in the fashion industry have a variety of approaches to utility patents. Some obtain many, while others obtain very few or none. Of those patents, some fall within the fashion-related classifications discussed in Section 6.2.1, while others relate to other aspects of their business. This diversity is seen even in the largest firms, as seen in this table of the worldwide number of patents obtained between 2000 and 2022 by apparel firms with market capitalisations of US$10 billion or more (Table 6.3).

| Company | Country | Market Cap | Grants |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVMH | France | $386 billion | 814 |

| Nike | United States | $186 billion | 5,694 |

| Hermès | France | $171 billion | 81 |

| Christian Dior | France | $138 billion | 198 |

| TJX Companies | United States | $91 billion | 0 |

| Inditex | Spain | $84 billion | 2 |

| EssilorLuxottica | France | $81 billion | 5,031 |

| Kering | France | $65 billion | 35 |

| Fast Retailing | Japan | $63 billion | 65 |

| Lululemon | Canada | $41 billion | 26 |

| Ross Stores | United States | $40 billion | 1 |

| Adidas | Germany | $26 billion | 1,772 |

| H&M | Sweden | $19 billion | 3 |

| Prada | Italy | $15 billion | 7 |

| Burlington Stores | United States | $13 billion | 0 |

| VF Corp. | United States | $11 billion | 7 |

| Zalando | Germany | $10 billion | 0 |

Several observations can be made about this data. First, there is a vast disparity in different firms’ patenting activities, which corresponds to differences in their underlying businesses. Just 4 of the 17 companies – LVMH, Nike, EssilorLuxottica and Adidas – account for almost 97% of the patent grants. What these four companies have in common is that their businesses are not limited to traditional apparel but include other categories of goods and services, both within the fashion industry (such as leather goods and jewellery) and in other markets. These non-apparel businesses account for most of their patents. Two of the companies, Nike and Adidas, are sportswear companies that make sneakers and a variety of sports equipment. EssilorLuxottica makes glasses, lenses and other optical goods. And LVMH is a conglomerate with dozens of luxury brands across numerous categories including wine and spirits (Dom Pérignon, Hennessy, Krug, Moët & Chandon, among others), watches and jewellery (Bulgari, Hublot, TAG Heuer, Tiffany & Co.), makeup and perfume (Acqua di Parma, Fenty Beauty, Sephora), even yachts and luxury trains. Moreover, the trend continues beyond the top four patent recipients: Christian Dior, the company with the fifth-most patent grants (and which has a complicated ownership structure that overlaps substantially with LVMH) sells a lot of perfume, which accounts for most of its patents.

Second, the number of patents obtained by firms is larger than the number of fashion-related patents obtained by the same firms, as discussed in Section 6.2.1.Footnote 12 This may seem obvious given the first observation, but the two points are distinct, because there may or may not be a correspondence between a firm’s patenting activity and its business activity. Indeed, firms patent many technologies that come out of research without ever intending to commercialise them.Footnote 13 Still, large fashion firms obtain many non-fashion patents in addition to patents falling within the fashion-related technology classes. Sometimes, they obtain these patents because they are also engaged in non-fashion businesses, like LVMH’s wine and spirits business. Sometimes, these patents cover underlying technologies that may be used in fashion goods without being listed within those classes. And sometimes, these patents relate to business operations or infrastructure, even if they don’t relate directly to the firm’s products. Fast Retailing, for instance, has several patents that cover retail equipment, like one on a ‘reading apparatus and commodity sales data processing apparatus’.Footnote 14 That patent’s classification entries fall within classes G06 (‘computing; calculating or counting’) and G07 (‘checking-devices’), not any of the fashion-related classes, even though the invention is closely related to the company’s operations. Similarly, Ross Stores has one patent, which describes and claims a ‘real estate management system and method’ that has nothing to do with fashion and everything to do with running a large retail chain.Footnote 15

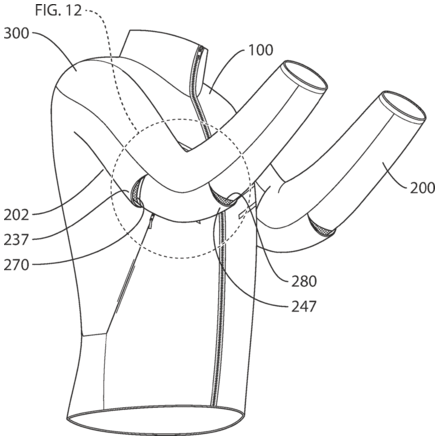

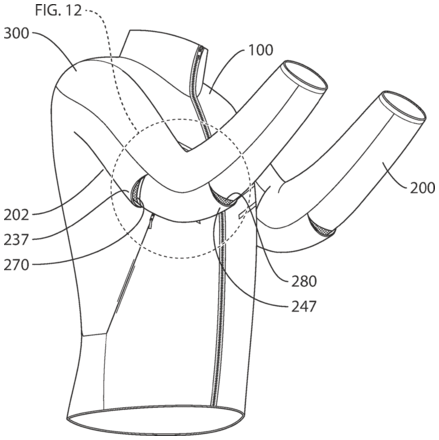

Third, among the long tail of firms that do not have hundreds or thousands of patents, there are still differences between different types of firms. For instance, those that sell their own goods have more patents than those who are retailers principally selling third-party goods. And this is true whether or not those brand sellers manufacture their own goods in house or rely on contract manufacturers. The pure retailers on the list – TJX (TJ Maxx and Marshalls, among others), Ross Stores, Burlington Stores and Zalando (a European e-commerce firm modelled on Zappos) – have only one patent between them, and it’s the Ross Stores real-estate patent mentioned above. Compare that to Hermès, Inditex (Zara), Kering (Gucci, Saint Laurent and Balenciaga, among others), Fast Retailing (Uniqlo), Lululemon, H&M, Prada and VF Corp., which have 226 patents combined. Some of these patents claim glasses, shoes or their components, like the companies with the most patents, and some claim business processes or technologies like retail point-of-sale terminals. But others claim traditional items of sewn apparel, like the jacket sleeves with built-in ventilation flaps covered by one Lululemon patent (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Lululemon sleeve patent.Footnote 16

Fourth, other than being largely based in Europe and the United States, this collection of companies shows no particular correlation between geography and patent strategy. The same is true when breaking down patent grants by issuing nation or patent office. Across all the companies listed, 54% of patents were obtained from the United States; 25% were issued by the European Patent Office or one of the national patent offices in Europe; 13% were issued by China; and the rest came from Canada (3%), Japan (3%), Australia (2%) and a smattering of other nations (1% combined).

Individual companies also acted globally when obtaining patents: other than Inditex’s two Spanish patents and Ross Stores’ one US patent, every company that obtained patents obtained them from multiple nations. Hermès’ 81 patents, for instance, were obtained from China, Denmark, France, Germany, Spain, Taiwan, the United States and the European Patent Office. And though a few companies have obtained a disproportionate number of patents from their home nations, that home-nation bias was small compared to the bias in favour of large markets like the United States and China.

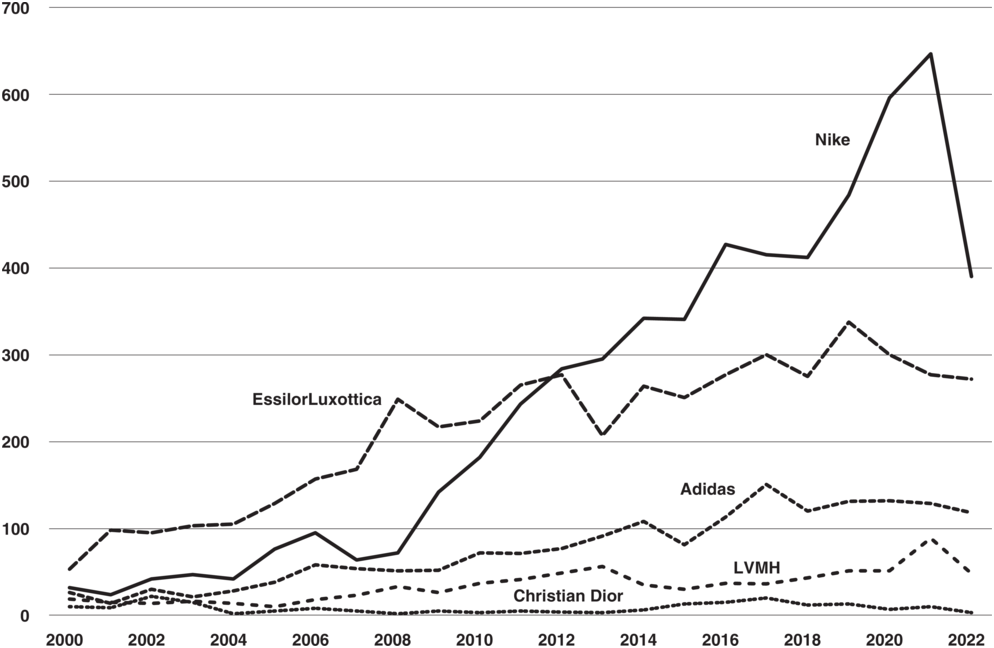

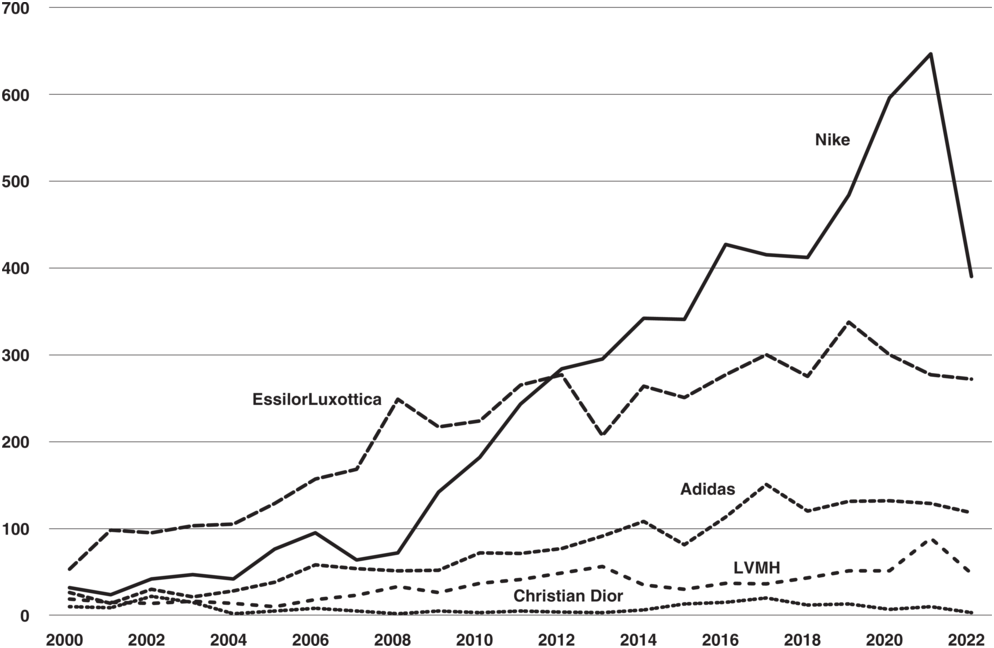

Finally, just as the number of fashion-related patents issued has increased over time, so has the number obtained by these large firms. Different firms, though, reflect different patterns, as seen in a graph of patents issued to the large fashion firms each year between 2000 and 2022 (Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 Patents issued to large fashion firms by year (2000–2022).

Figure 6.3Long description

The graph plots multiple lines of which, Essilor Luxottica originates at (50, 2000), fluctuates and terminates at (2022, 380). Nike originates at (2000, 30), fluctuates, rises and terminates at (2000, 390). Addidas originates at (25, 2000), fluctuates over the horizontal axis and terminates at (2022, 120). L V M H originates at (2000, 20), fluctuates over the horizontal axis and terminates at (2022, 50). Christian Dior originates at (2000, 10), fluctuates over the horizontal axis and terminates at (2022, 0). The values are estimated on the vertical axis.

While every company except Christian Dior has increased its patenting activity over time, some have increased far more quickly than others; compare, for instance, Nike and EssilorLuxottica.Footnote 17 This suggests that patenting growth is more likely to reflect individual companies’ growth, strategies and other circumstances more than broader trends in the fashion industry.

There are limitations to how much we can infer from patenting activity, since the act of obtaining a patent doesn’t say anything about how that patent is used. But patent activity does provide tentative indications that the fashion industry does make use of patents, albeit to a lesser degree than some other fields. That use is concentrated among firms that make athletic wear, watches, eyewear and other accessories more than traditional apparel manufacturers. It is also clear that not all fashion-related patents are obtained by fashion firms; plenty of other companies obtain patents that are classified, in part, in classes that relate to fashion. Likewise, not all patents obtained by fashion companies cover fashion-related inventions; others cover the full array of things these companies do, like Ross Stores’ real-estate patent. But to move beyond these inferences, it is helpful to widen the scope beyond just the act of acquiring patent rights to the use of those patents once acquired.

6.3 Using Patents: Patent Litigation

Patent scholars generally think about three broad ways that a patent can be valuable to a company: as an asset to be monetised (whether through infringement litigation, licensing or the rents that come from a legal monopoly), as a signalling tool (whether to investors, competitors, potential clients or employees or others) or as a defensive tool (in the event that a competitor brings a patent lawsuit).Footnote 18 These different sources of value can make it difficult to understand a firm’s patent strategy, since some, like litigation, are fairly transparent, while others, like licensing, may be entirely opaque to outsiders.

Still, there are ways to obtain insights about a firm’s patent strategy from its visible patent activities. Looking at litigation is maybe the simplest, since the possibility of infringement litigation is the implicit threat even in a friendly license agreement, so that a firm with significant licensing activity will generally also have significant litigation activity.

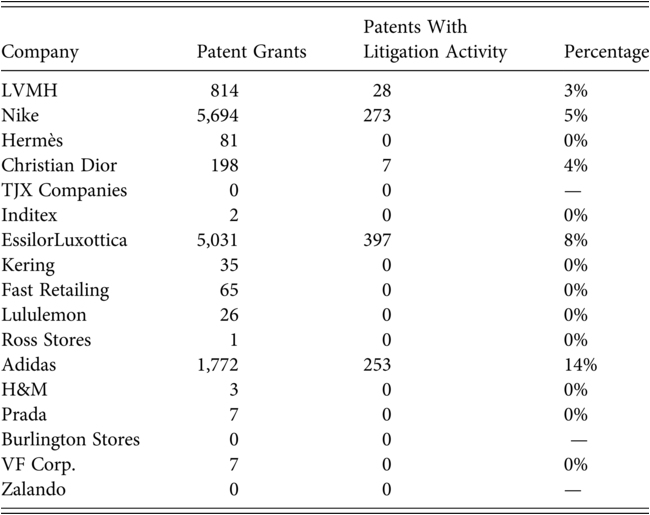

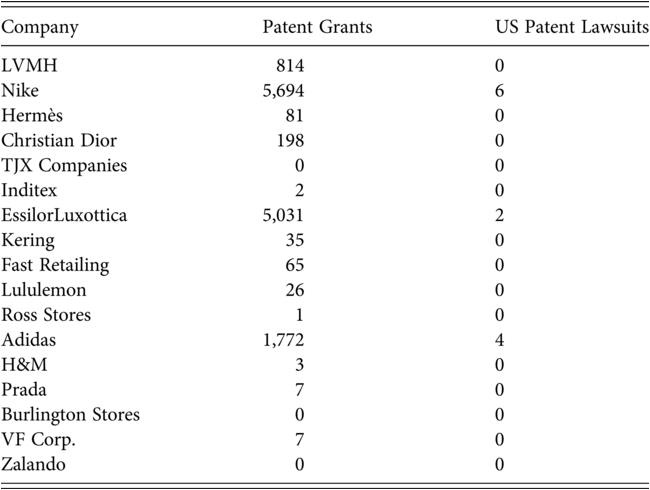

A surface look at patent-litigation activity by the large apparel companies discussed above shows a wide array of litigation activities, with some firms frequently litigating their patents and others never doing so, as seen in Table 6.4, showing the number of patents with related litigation activity.

| Company | Patent Grants | Patents With Litigation Activity | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVMH | 814 | 28 | 3% |

| Nike | 5,694 | 273 | 5% |

| Hermès | 81 | 0 | 0% |

| Christian Dior | 198 | 7 | 4% |

| TJX Companies | 0 | 0 | — |

| Inditex | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| EssilorLuxottica | 5,031 | 397 | 8% |

| Kering | 35 | 0 | 0% |

| Fast Retailing | 65 | 0 | 0% |

| Lululemon | 26 | 0 | 0% |

| Ross Stores | 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Adidas | 1,772 | 253 | 14% |

| H&M | 3 | 0 | 0% |

| Prada | 7 | 0 | 0% |

| Burlington Stores | 0 | 0 | — |

| VF Corp. | 7 | 0 | 0% |

| Zalando | 0 | 0 | — |

On the whole, compared to other industries traditionally seen as depending on patents, the fashion industry obtains fewer patents and is less likely to litigate the patents it does get. For instance, the three largest pharmaceutical companies – Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson and Novo Nordisk – have collectively obtained more than 5,000 patents that had litigation activity, amounting to 14% of their patent portfolios. Similarly, the tech companies Apple, Microsoft and Samsung have collectively obtained more than 6,500 patents that had litigation activity, making up 11% of their patent portfolios. By these standards, Adidas is the only large apparel company that compares.

Even though these statistics suggest that patent litigation is not driving fashion firms’ patenting activities, they nevertheless likely overstate the degree to which large fashion firms assert their patents in litigation, for a few reasons. For one, the related litigation activity reflected in Table 6.4 refers to any litigation over any patent in a patent’s global family, which can be scores of patents from numerous countries. At the same time, a single patent-infringement lawsuit may assert many patents, even if only one or two are core to the dispute between the parties. Consequently, a large number of patents with related litigation may reflect only a small number of live patent disputes.

To obtain a better understanding of how fashion firms use patents in litigation, the Stanford NPE Litigation DatabaseFootnote 20 and PACERFootnote 21 were used to identify US lawsuits in which these firms asserted patents. Although the count is not exhaustive due to older cases with incomplete files, remarkably, only twelve cases were identified in which these companies asserted utility patents (Table 6.5).Footnote 22

| Company | Patent Grants | US Patent Lawsuits |

|---|---|---|

| LVMH | 814 | 0 |

| Nike | 5,694 | 6 |

| Hermès | 81 | 0 |

| Christian Dior | 198 | 0 |

| TJX Companies | 0 | 0 |

| Inditex | 2 | 0 |

| EssilorLuxottica | 5,031 | 2 |

| Kering | 35 | 0 |

| Fast Retailing | 65 | 0 |

| Lululemon | 26 | 0 |

| Ross Stores | 1 | 0 |

| Adidas | 1,772 | 4 |

| H&M | 3 | 0 |

| Prada | 7 | 0 |

| Burlington Stores | 0 | 0 |

| VF Corp. | 7 | 0 |

| Zalando | 0 | 0 |

These cases fall into two broad categories. The main category is lawsuits against large competitors, in which patented technologies are the core of the dispute; Adidas, for instance, has filed patent lawsuits against competing shoemakers Asics, Nike, Skechers and Under Armour,Footnote 23 while Nike, in turn, has filed patent lawsuits against Adidas, Hummel and Puma.Footnote 24 (Indeed, a significant chunk of these cases are part of a long-running dispute between Nike and Adidas, which extended beyond federal litigation to proceedings before the Patent and Trademark Office and the International Trade Commission, before it settled in 2022.)Footnote 25 But considering the size of the fashion industry, there are not very many of these cases; they all appear to involve shoes or glasses. Beyond these cases, there are a few lawsuits against companies selling knockoffs, in which the asserted patents are sideshows to claims asserting trademarks, design patents, and other causes of action like unfair competition.Footnote 26

The small number of patent lawsuits brought by fashion companies doesn’t necessarily mean that the fashion industry is failing to get value out of its patent portfolios. Not all the industries that are traditionally seen as dependent on patents litigate large numbers of them. Semiconductor manufacturing, for instance, is an intensely competitive industry that obtains many patents and considers them strategically important yet litigates very few of them. Intel, Nvidia and TSMC, for instance, have collectively obtained 995 patents that had related litigation, accounting for just 2% of their collective portfolios. One possible explanation is that these firms are more likely to rely on licensing – especially cross-licensing agreements with competitors – because the industry is fairly concentrated and has high barriers to entry. Since there are fewer players to worry about, it is easier to focus on resolving disputes without litigation. (It helps that semiconductor manufacturing is a classic patent thicket – a field with many overlapping patents that make it almost impossible to operate without practicing some patented invention – which gives firms a strong incentive to reach cross-licensing agreements and avoid becoming defendants in litigation.)Footnote 27

The technology-centric portions of the fashion industry, like athletic wear and glasses, resemble the semiconductor-manufacturing industry in a key way: both have a small number of firms that account for most of the market share. But there are also critical differences. Fashion firms mostly sell to consumers, not businesses like semiconductor manufacturers, and they depend more on marketing and style to sell their products, compared to the continual technological innovation of semiconductor manufacturing. So, we should expect these fashion companies to rely less heavily on patents, whether through infringement litigation or cross-licensing. And that is consistent with the relatively few patent lawsuits brought by the fashion industry.

6.4 Patents and the Nature of Utility in Fashion

As discussed before, most of the patents obtained by large fashion companies don’t actually claim apparel; instead, they often claim sporting equipment or accessories or retail strategies and tools or constituent technologies for these things. But there are patents, like the Lululemon sleeve patent mentioned above (Figure 6.1), that claim traditional forms of apparel.

In addition to revealing information about the fashion industry and its strategic decision-making, these patents tell us something about the nature of utility in fashion and the relationship of fashion to different forms of intellectual-property protections. Intellectual property traditionally draws a distinction between utilitarian or functional creations – which are protected by utility patents – and creations that are creative or aesthetic or artistic rather than functional – which are protected by copyrights and design patents. Fashion, though, makes a mess of this traditional dichotomy, since even basic questions like what counts as utility versus aesthetics are debated and disputed. Fashion firms, policymakers, courts and others have responded to this uncertainty by attempting to use a wide array of protections – traditional ones like patents and copyright and more novel ones like design rights and trade dress claims within trademark law – and by using these protections in new ways, as when a designer plasters a logo all over a product to gain stronger trademark protections.

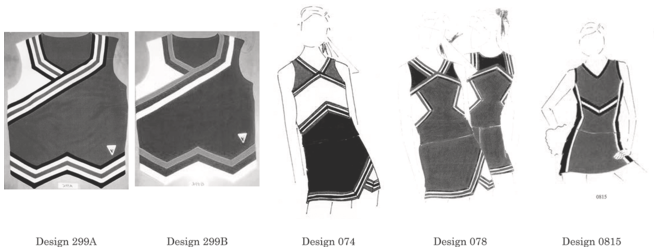

The US Supreme Court confronted these difficulties in 2017, concluding in Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc. that designs of cheerleader uniforms could be protected by copyright law notwithstanding that the uniforms were ‘useful articles’.Footnote 28 At issue was whether elements of clothing designs, such as stripes, chevrons or zigzags, were protectable as aesthetic elements of an otherwise useful article of clothing. Under US copyright law, to be protectable, the uniforms’ ‘pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features’ must be capable of being ‘identified separately from’ and ‘existing independently of the utilitarian aspects of the article’.Footnote 29 By concluding that the design of the uniforms could be copyrighted, the court necessarily concluded that the graphic features of the uniform could exist ‘independently of the utilitarian aspects’ of the uniform.

The court’s resolution of Star Athletica suggests that patent law would not cover those graphic features because they are separate and independent of the uniform’s utility. Indeed, in an important trademark case in 2001, the court adopted this reasoning, concluding that a company could not obtain trademark protections for a product feature – which, like copyright law, requires that the feature not be functional – precisely because that feature had been protected by a utility patent:

A utility patent is strong evidence that the features therein claimed are functional. If trade dress protection is sought for those features the strong evidence of functionality based on the previous patent adds great weight to the statutory presumption that features are deemed functional until proved otherwise by the party seeking trade dress protection.Footnote 30

So, if a utility patent is strong evidence of functionality, and the graphic features of a cheerleader uniform can exist separately from the utilitarian aspects of the uniform, then those features should not be patentable (assuming functionality and utility are synonyms).

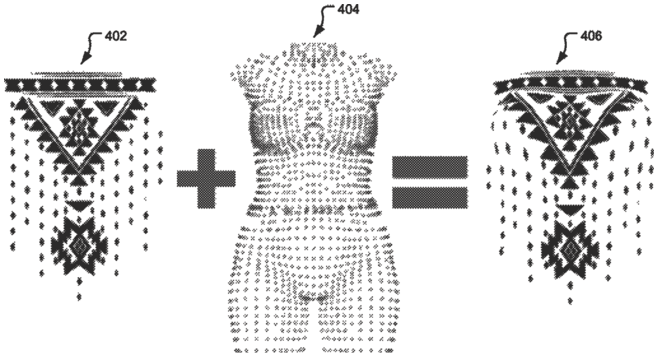

Remarkably, however, a review of patents obtained by fashion companies shows that graphic features of apparel are frequently patented, precisely because of the aesthetic characteristics of those features. These patents generally claim methods of using two-dimensional clothing design to make clothing that creates a favourable three-dimensional shape or a favourable perception of a person’s body shape. For instance, one patent obtained by VF Corp., for a ‘body-enhancing garment and garment design’,Footnote 31 describes the invention like this:

Many garments are constructed with visible patterns on the fabric. These patterns typically utilize symmetrical, straight, and/or repeating details or pattern elements and have no intentional brightness gradients when the garments are laid flat. Additionally, patterns may include illusory details or lines created within the negative space between the pattern elements, and serve as an informative element of the pattern itself. These patterns become curved and shaded when worn on the body. The visual system assumes that the curvature and/or brightness gradients of those patterns is attributed entirely to the body shape (i.e., that curved lines of the pattern on the garment would be straight lines if the garment was laid flat). Thus, using the rules of perception, the visual system constructs a three-dimensional body shape based in part on the curvature, size, and shading of the pattern.

* * *

When a person wears clothing, he or she voluntarily puts patterned clothing on his or her body. The brain interprets the lines, spacing, sizing and other elements of the pattern using the rules discussed above and other rules known within the field of vision science. Current clothing designs do not take into account that the brain uses these patterns on garments to construct a 3D shape of the wearer. As such, a problem with existing garment construction or design is that it can create garments that make an individual’s form less attractive to others, a result that is typically not desired by the individual wearing the garment. While the rules of perception have been heavily studied, these rules have not been applied to clothing. Further, the rules of perception have not been utilised on a garment to change the perception of a human feature to fall within or move towards known attractive size and shape ranges and/or desired size and shape ranges when worn.

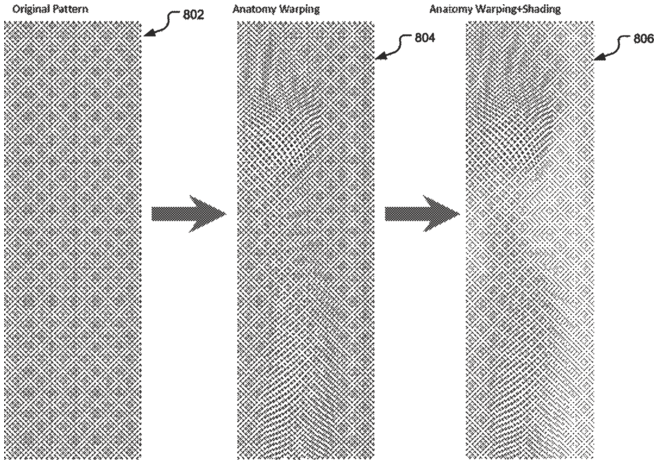

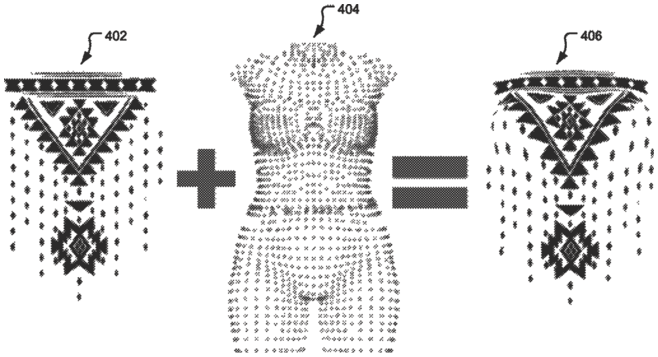

The patent goes on to describe and claim various methods for using shading, curved lines and other optical tricks on clothing to tweak how the shape of a person’s body will be perceived by others. For instance, if a garment has a pattern of dots, then the position of those dots could be shifted in a way that reflects the desired 3D body shape of the wearer. A viewer’s eye will assume that the dots reflect a fixed pattern and will see the tweaked pattern as reflecting the intended shape. The patent shows this concept in Figures 6.4 and 6.5.

Figure 6.4 Body-enhancing garment patent.Footnote 32

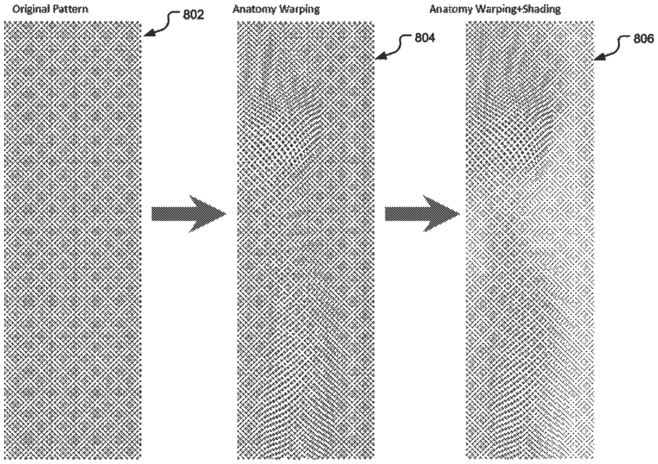

Figure 6.5 Shading patent for aesthetic effects via optical illusions.Footnote 33

Figure 6.5Long description

Three broad patterned stripes of cloth are illustrated vertically. The original pattern exhibits a consistent grid-like pattern. The anatomy warping shows a distorted pattern. Anatomy Warping + Shading has a pattern which is further distorted and has shading applied. The numerical values of 802, 804, and 806 are indicated with arrows in the original pattern, Anatomy warping and Anatomy Warping + Shading, respectively.

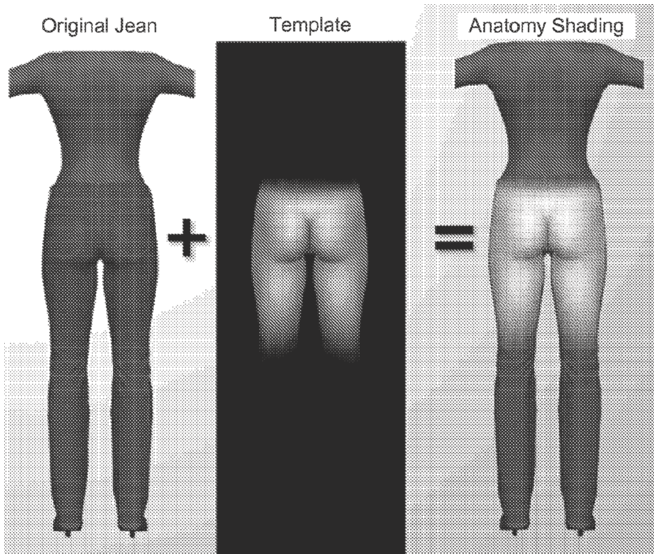

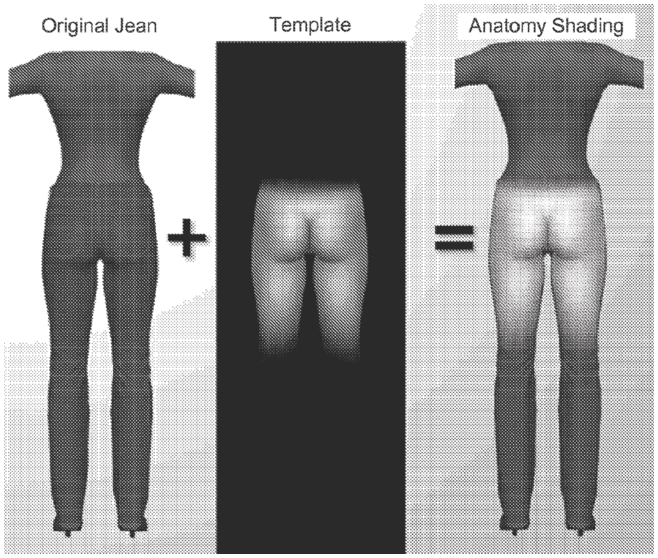

And other patents describe and claim similar illusions. A European patent jointly obtained by VF Corp. and the University of California, for instance, describes and claims a ‘method for anatomy shading for garments’ that uses shading instead of pattern distortion to accomplish the same sort of optical tricks (Figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6 Anatomy-enhancing shading on jeans.Footnote 34

Figure 6.6Long description

The process shows a basic silhouette of jeans labeled original jeans, followed by a plus symbol, a grayscale template with buttocks in focus, an equal symbol, the original jean silhouette with the template's shading with bare buttocks.

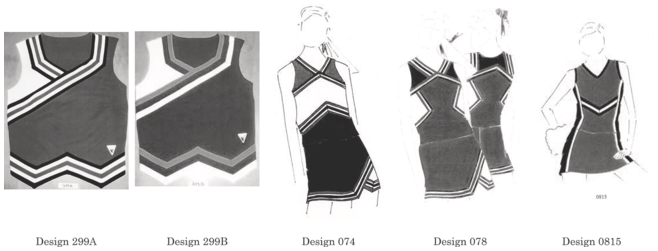

The use of optical tricks to affect how clothes look on a person is, of course, not a new concept in fashion; designers have been doing similar things for centuries. Indeed, the cheerleader uniforms at issue in Star Athletica have the designs they do precisely because they create certain impressions when worn by cheerleaders, as discussed elsewhere in this volume (Figure 6.7).Footnote 35

Figure 6.7 Cheerleader uniforms at issue in Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands.

The combinations of colour blocking, chevrons, diagonal lines, inward-pointing angles and other features aren’t just artistic choices by the designer; they’re choices designed to make the wearer – a cheerleader – look better. As Christopher Buccafusco and Jeanne C Fromer have explained elsewhere, clothing is not generally designed to look good in isolation; it’s designed to look good when worn by someone.Footnote 36

The fact, then, that companies have sought, and obtained, utility-patent protection for inventions designed to change the visual perception of a person wearing a particular garment provides additional evidence, if more were needed, that the aesthetic design of fashion has functionality. And in turn it bolsters the case, contra Star Athletica, against protecting fashion designs using copyright law or novel forms of intellectual-property protections. Instead, it suggests that utility patents may be a better fit, despite the small amounts of patent litigation engaged in by fashion companies.

6.5 Conclusion

Fashion is not an obvious fit for utility patents, since the things that make a fashion firm successful are generally not the sorts of things protectable by patent law. Yet despite that poor fit, thousands of patents are granted each year for fashion-related technologies, and large fashion companies have obtained thousands of patents between them. At the same time, evidence of how the industry uses these patents is hard to come by since few are litigated and the industry lacks the sort of cross-licensing arrangements that some more patent-dependent industries use.

The kinds of inventions patented by the fashion industry range from traditional apparel to athletic wear to fashion-adjacent technologies like business methods and retail equipment. The most interesting ones, however, provide insights into a core issue in fashion law: the line between functionality and aesthetic or artistic expression. These patents claim and protect ways of tweaking the aesthetic designs of clothing to change how they look on their wearers. The availability of utility patents for these inventions suggests that aesthetic choices in fashion do serve functional purposes, and therefore that that the law should look more sceptically upon efforts to extend copyright and other non-patent protections to aesthetic choices made by fashion designers.