Introduction

Vitamins of the B-complex represent water-soluble molecules with essential roles in humans. The present review is a follow-up to our previous manuscript, in which we summarised the biological properties of the vitamins B1, B2, B3 and B5 (Reference Hrubša, Siatka and Nejmanová1). Herein, we centre on vitamins B6 and B7 (biotin) to provide a comprehensive summary of sources, properties, physiological functions, disorders that result from their deficiency and scientific information, which has been often overlooked since their discovery. We sought to cover all significant studies on the topic, including current trends and potential directions for future research. Such a review has been previously missing in the available literature.

Methods

PubMed was used as the bibliography database, and eligible publications were selected from 1938 to 2023. The following keywords were added to the query box: (vitamin B6 AND properties) and (vitamin B6 AND sources) and (vitamin B6 AND pharmacokinetics), (vitamin B6 AND physiological function), (vitamin B6 AND pharmacological uses), (vitamin B6 AND toxicity). Instead of vitamin B6, similar combinations were used with pyridoxine, vitamin B7 and biotin. The eligibility criteria were as follows: peer-reviewed journal articles or book chapters published in the English language. There were no exclusion criteria for the search.

Vitamin B6

An introduction to vitamin B6

Vitamin B6, ordinarily but imprecisely known as pyridoxine, is a general term for water-soluble pyridine derivatives with the same physiological role. This vitamin comprises six related compounds – vitamers (Fig. 1a), that is, pyridoxine (or pyridoxole, an alcohol), pyridoxal (an aldehyde), pyridoxamine (an amine) and their 5′-phosphate esters, such as pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP), pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate and pyridoxine 5′-phosphate. PLP is the biologically active form of vitamin B6 because it is a cofactor of most vitamin B6-dependent enzymes in the organism(Reference McCormick, Bowman and Russell2,Reference Mooney, Leuendorf, Hendrickson and Hellmann3) .

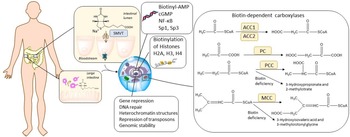

Fig. 1. Chemical structures of vitamin B6, including its active forms, and vitamin B7. (a) Structure of the vitamers of B6. (b) Vitamin B6 salvage pathway. PK, pyridoxine/pyridoxamine/pyridoxal kinase; PNPO, pyridoxine phosphate oxidase. (c) Chemical structure of D(+)-biotin. The biotin molecule is composed of two rings: an imidazolidinone ring (blue) and a tetrahydrothiophene group (red) attached to a valeric acid moiety as a side chain (yellow).

Pyridoxine was discovered in 1934 by Hungarian physician Paul György and colleagues, and was isolated in pure form shortly thereafter. Humans must acquire it from their diet. Moreover, PLP can be recycled from food and degraded vitamin B6 in the salvage pathway when the vitamin undergoes interconversion inside cells and yields different forms, including active PLP (Fig. 1b)(Reference Eliot and Kirsch4,Reference Leklem5) . Pyridoxine, pyridoxal and pyridoxamine are converted to their phosphorylated forms by the pyridoxine/pyridoxamine/pyridoxal kinase, while phosphatases hydrolyze phosphorylated vitamin B6 vitamers. Pyridoxine 5′-phosphate and pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate are further oxidised to the active form, PLP, by the enzyme pyridoxine (pyridoxamine) phosphate oxidase.

Sources of vitamin B6

Natural sources of vitamin B6

Plants, fungi, archaea and most bacteria synthesise pyridoxine, whereas animals and humans lack enzymes for its biosynthetic pathway and rely solely on the exogenous supply of the vitamin(Reference Mooney, Leuendorf, Hendrickson and Hellmann3,Reference Tanaka, Tateno and Gojobori6–Reference Chen and Xiong27) . Vitamin B6 is widely distributed in foods of plant and animal origin. Whole grains, bananas, potatoes, pulses, nuts, beef, pork, poultry, organ meats and fish are good sources for humans(Reference da Silva, Gregory, Marriott, Birt, Stallings and Yates28–Reference Planells, Sanchez, Montellano, Mataix and Llopis50). Some herbs and spices (for example, garlic, curry, and ginger)(51), some gluten-free pseudocereals (for example, amaranth)(Reference Rybicka and Gliszczynska-Swiglo52) and royal jelly are also rich in vitamin B6 (Reference McDowell37,Reference Kamyab, Gharachorloo, Honarvar and Ghavami53) . In animal-derived foods, vitamin B6 is usually present in phosphorylated forms (mainly of pyridoxal and pyridoxamine) and, to a lesser extent, in the free form(Reference Liu, Farkas, Wang, Kohli and Fitzpatrick23,Reference McDowell37,Reference Ollilainen54–Reference Schmidt, Schreiner and Mayer56) . There is limited information on the bioavailability of vitamin B6 from animal products in humans. The bioavailability is estimated to be generally high and, in many cases, almost complete. However, thermal processing reduces it by 25–30%; and the reaction between pyridoxal and pyridoxal phosphate with the ε-amino group of protein-bound lysine may be responsible for the decreased bioavailability(Reference Reynolds57–Reference Kabir, Leklem and Miller61). In plant-derived foods, the vitamin usually occurs as both free pyridoxine and in a glycosylated form, particularly as pyridoxine-β-d-glucoside, whose proportion can range depending on the plant species, from 5% to 75% of the total vitamin content(Reference Liu, Farkas, Wang, Kohli and Fitzpatrick23,Reference da Silva, Gregory, Marriott, Birt, Stallings and Yates28,Reference Ollilainen54,Reference Reynolds57,Reference Gregory62–Reference Mangel, Fudge, Gruissem, Fitzpatrick and Vanderschuren68) . The glucoside is only partly cleaved enzymatically by hydrolases in the small intestine, and its bioavailability is about 50% and 75% lower than that of free pyridoxine in humans and rats, respectively, that is to say, that apparently the capability of utilising the glycosylated form is species specific. The contribution of pyridoxine-β-d-glucoside to the total vitamin B6 intake in the average human diet is around 15%, hence different types of vegetarian diet do not pose a risk for vitamin B6 deficiency. This fact is also supported by findings from a population-based survey comparing the vitamin B6 status among vegetarians, pescatarians, flexitarians and meat-eaters. However, individuals with a marginal intake of total vitamin B6 would be more prone to reduced nutritional status due to this incomplete bioavailability(Reference da Silva, Gregory, Marriott, Birt, Stallings and Yates28,29,Reference Waldmann, Dörr, Koschizke, Leitzmann and Hahn46,Reference Ollilainen54,Reference Reynolds57,Reference Ink, Gregory and Sartain58,Reference Gregory62,Reference Gregory64,Reference Gregory, Trumbo, Bailey, Toth, Baumgartner and Cerda69–Reference Strain, Hughes, Pentieva, Ward, Hoey, McNulty, Biesalski, Drewnowski, Dwyer, Strain, Weber and Eggersdorfer83) . The absolute bioavailability of vitamin B6 from a mixed diet is estimated to be about 75%(29,Reference Jungert, Linseisen, Wagner and Richter44,Reference Spinneker, Sola, Lemmen, Castillo, Pietrzik and Gonzalez-Gross84–Reference Tarr, Tamura and Stokstad86) .

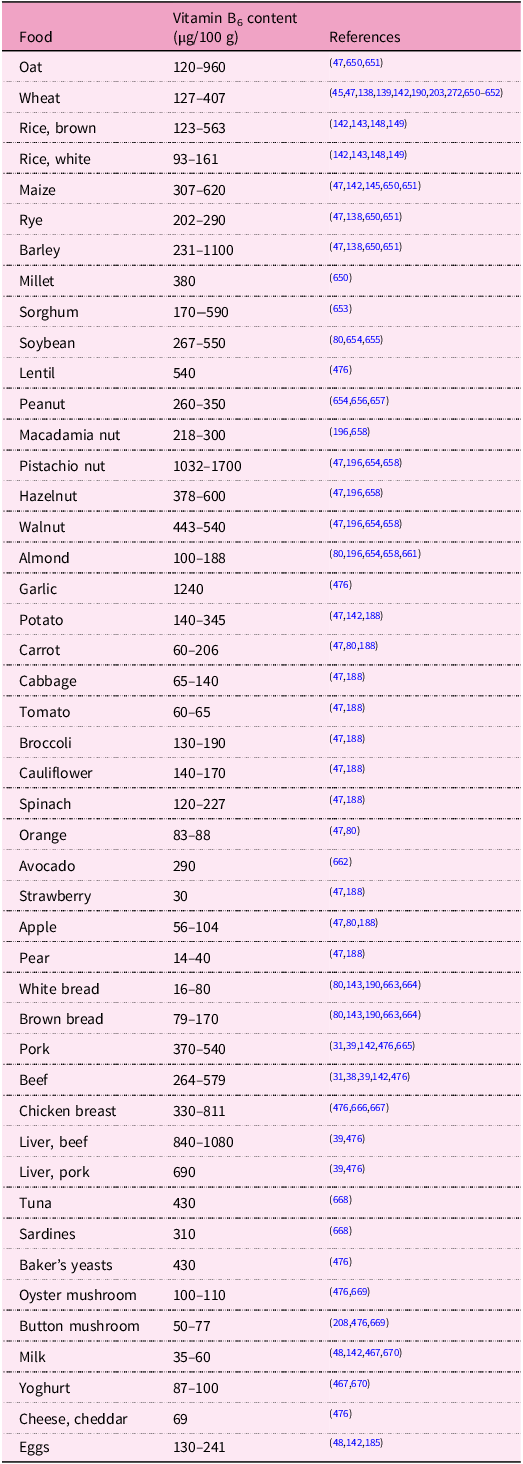

Vitamin B6 is also synthesised in significant quantities by the microbiota of the human large intestine, and this could represent a secondary exogenous source of the vitamin. Indeed, the existence of a specific carrier-mediated mechanism for pyridoxine uptake in human colonocytes was demonstrated. Conversely, it is likely that a large portion of the vitamin produced by microbiota is taken up by non-synthesising microbes. The extent of the contribution of microbially produced vitamin B6 to overall body levels is unclear as there are no human studies to provide evidence for it(Reference Magnusdottir, Ravcheev, de Crecy-Lagard and Thiele22,Reference da Silva, Gregory, Marriott, Birt, Stallings and Yates28,29,Reference McDowell37,Reference Combs and McClung87–Reference Rodionov, Arzamasov and Khoroshkin93) . Amounts of vitamin B6 in some selected foodstuffs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Vitamin B6 content in selected foodstuffs

Antivitamins B6

The diet can also contain antivitamin B6 that either compete for reactive sites of vitamin B6-requiring enzymes or directly inactivate the vitamin(Reference McDowell37,Reference Mayengbam, House and Aliani94) . The best-known antivitamin B6 is probably ginkgotoxin (4’-O-methylpyridoxine), which occurs in different tissues of the tree Ginkgo biloba, with the highest concentrations being present in seeds. Ingestion of ginkgotoxin can lead to abdominal pain, epileptiform convulsions and loss of consciousness due to the aforementioned interference with vitamin B6. As seeds are a food source in Southeast Asia, including China, Japan and Korea, and extracts from leaves are used in pharmaceutical products worldwide, they represent a potential health risk(Reference Mooney, Leuendorf, Hendrickson and Hellmann3,Reference Wada, Ishigaki, Ueda, Sakata and Haga95–Reference Gong, Wu, Fan, Li, Wang and Wang112) . Indeed, ginkgotoxin and its derivatives found in the African trees of the genus Albizia (for example, A. tanganyicensis, A. versicolor, A. julibrissin and A. lucida) are the cause of poisoning of livestock (cattle and sheep): one of the most important agricultural problems in South Africa(Reference Mooney, Leuendorf, Hendrickson and Hellmann3,Reference Leistner and Drewke101,Reference Steyn, Vleggaar and Anderson113) . Flaxseed contains the vitamin B6 antagonists, 1-amino-d-proline, and its precursor, the dipeptide linatine. Their possible deleterious effects through the consumption of flaxseed deserve attention in individuals with moderate vitamin B6 status(Reference Mayengbam, House and Aliani94,Reference Mayengbam, Raposo, Aliani and House114–Reference Klosterman118) . Gyromitrin (N-methyl-N-formylhydrazone) from the toxic mushroom Gyromitra esculenta (genus Gyromitra is also known as false morrel) is converted to (mono)methylhydrazine after ingestion, which is able to inhibit pyridoxal kinase and hence depletes vitamin B6. Intoxication usually occurs about 10 h after the ingestion of fresh or dried mushrooms. It gives rise to poisoning symptoms such as confusion and seizures. Interestingly, during cooking, methylhydrazine volatilises, and poisoning occurs also after inhalation of these vapours(Reference Klosterman118–Reference Horowitz, Kong and Horowitz122). Similarly, agaritine containing a hydrazinic moiety in its structure is a toxic principle of various Agaricus species, for example, the edible button mushroom Agaricus bisporus (Reference Klosterman118,Reference Lagrange and Vernoux121,Reference Berdanier, Berdanier, Dwyer and Feldman123) . The content of both toxins in fungi may be decreased by processing, such as boiling in water, drying and freezing(Reference Lagrange and Vernoux121,Reference Arshadi, Nilsson and Magnusson124,Reference Roupas, Keogh, Noakes, Margetts and Taylor125) . Other natural vitamin B6 antagonists, which are of little significance to human nutrition, are toxic non-proteinogenic amino acids occurring in some leguminous plants: mimosine in Mimosa and Leucaena species, and canavanine and canaline in Canavalia species(Reference Klosterman118,Reference Klosterman126–Reference Gregory and Kirk132) .

Effects of food processing on vitamin B6 content

Food processing is the transformation of agricultural products into foods for human consumption. Primary processing is the conversion of the inedible raw products into food ingredients. Secondary processing involves the conversion of food ingredients into edible foods. Tertiary processed foods are commercially prepared foods. Products from primary processes make up the major part of the human diet as they are either consumed raw or used as ingredients in secondary and tertiary processes(Reference Özilgen, Özilgen and Hitzmann133). Food processing may alter the vitamin B6 content(Reference Berry Ottaway, Skibsted, Risbo and Andersen134,Reference Godoy, Amaya-Farfan, Rodriguez-Amaya, Rodriguez-Amaya and Amaya-Farfan135) . A rough overview of the major data on vitamin B6 losses in some food groups due to processing is presented in Supplementary Table S1 in the Supplementary Data. More data on specific foods, information on conditions and comments are in the text below.

Milling and refining of cereals

The primary processing of cereals (milling and refining) that separates the bran and germ, which are rich in micronutrients, from starchy endosperm causes a considerable loss of vitamin B6 (Reference Slavin, Jacobs and Marquart136–Reference Brouns, Hemery, Price and Anson141). Milling reduces the value of the vitamin B6 content in maize by 65–75%(Reference Thielecke, Lecerf and Nugent137,Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142–Reference Dunn, Jain and Klein146) . The vitamin B6 content decreases by 66–89% in white wheat flour, compared with wholegrain flour(Reference Shewry and Hey45,Reference Slavin, Jacobs and Marquart136–Reference Călinoiu and Vodnar138,Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142–Reference Hegedüs, Pedersen and Eggum144,Reference Henry and Heppell147) . The content of vitamin B6 is likewise 64% and 79.5% lower in refined than in wholegrain rye and sorghum flour, respectively.(Reference Hegedüs, Pedersen and Eggum144). Vitamin B6 losses in non-parboiled and parboiled white rice are 42–86% and 12–26%, respectively, compared with brown rice. The decline in vitamin B6 in parboiled rice is lower, in contrast to the non-parboiled one, because a part of the vitamin diffuses from the vitamin-rich outer bran layer into the endosperm during the parboiling process that takes place before milling(Reference Mangel, Fudge, Gruissem, Fitzpatrick and Vanderschuren68,Reference Thielecke, Lecerf and Nugent137,Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142,Reference Garg, Sharma and Vats143,Reference Tiozon, Fernie and Sreenivasulu148–Reference Schroeder152) . The secondary processing of cereals, such as breadmaking, rice cooking and nixtamalisation of maize, brings on additional vitamin B6 losses. They are discussed later (‘Processing of plant-based foods’).

Properties of vitamin B6 and mechanisms of vitamin loss during food processing

Vitamin B6 loss during processing and storage of food can occur in several ways. Being soluble in water, leaching is one of the principal causes. Vitamin B6 in foods is stable under acidic conditions but unstable in neutral and alkaline environments, particularly when exposed to heat or light. The acidic aqueous solutions of vitamin B6 may be heated without decomposition, as vitamin B6 is destroyed by ultraviolet radiation in neutral or alkaline solutions but not in acidic solutions. Vitamin B6 is normally stable to oxygen. Of the several vitamers, pyridoxine is far more stable than pyridoxal and pyridoxamine. Therefore, the processing losses of vitamin B6 tend to be highly variable, with plant-derived foods (containing mostly pyridoxine) losing little of the vitamin, and animal products (containing mostly pyridoxal and pyridoxamine) associated with higher losses(Reference McDowell37,Reference Gregory, Ink and Sartain59,Reference Combs and McClung87,Reference Gregory and Kirk132,Reference Berry Ottaway, Skibsted, Risbo and Andersen134,Reference Godoy, Amaya-Farfan, Rodriguez-Amaya, Rodriguez-Amaya and Amaya-Farfan135,Reference Henry and Heppell147,Reference Aboul-Enein and Loutfy153–Reference Ribeiro, Pinto, Lima, Volpato, Cabral and de Sousa166) .

Processing of animal-based foods

Boiling, stewing, roasting and frying reduce the vitamin B6 content by 55%, 33–58%, 30% and 40–45%, respectively, in pork; by 60–77%, 55–57%, 40% and 55–58%, respectively, in beef; and by 40–58%, 40–47%, 50% and 45–56%, respectively, in chicken, depending on cooking temperature and time(Reference Shibata, Yasuhara and Yasuda161,Reference Mašková, Rysova, Fiedlerova and Holasova167–Reference Çatak and Çaman171) . In whole meat dishes, including cooking liquid, gravy, juice or soup, about 15–20% more vitamin B6 remains, owing to retention of the vitamin that leached into the water phase(Reference Bognár168,Reference Bognár170,172–Reference Meyer, Mysinger and Wodarski174) . Fried breaded meats contain 5–35% more vitamin B6 than those without breading, which may assist in trapping the liquid and, therefore, decreasing the loss of water-soluble vitamins(Reference Bognár170,Reference Olds, Vanderslice and Brochetti175) . About 9% of vitamin B6 was lost from pork and beef when the drip exuding from the frozen meat during thawing was discarded(Reference Pearson, Burnside, Edwards, Glasscock, Cunha and Novak176,Reference Pearson, West and Luecke177) . The cooking loss of vitamin B6 in fish meat (gilthead seabream, anchovy and Atlantic bonito) was 55–85% and 60–89% when grilled and baked, respectively, due to thermal degradation and leakage of the vitamin in the lost water(Reference Çatak, Çaman and Ceylan178). Heat-induced reduction of vitamin B6 in milk is usually 5–20%, 5–10%, 5–20%, 10–50% and 40% for boiled, pasteurised, ultra-high temperature treated, sterilised and condensed milk, respectively, compared with raw milk(Reference Berry Ottaway, Skibsted, Risbo and Andersen134,Reference Bognár170,Reference Muehlhoff, Bennett and McMahon179–Reference Amador-Espejo, Gallardo-Chacon, Nykänen, Juan and Trujillo184) . Hard cooked, poached, scrambled, baked and fried eggs lose 20–23%, 15%, 10%, 10% and 10% of vitamin B6 during cooking, respectively(Reference Bognár170,Reference Roe, Church, Pinchen and Finglas185,Reference Öhrvik, Carlsen, Källman and Martinsen186) .

Processing of plant-based foods

Boiling, steaming and frying lead usually to a vitamin B6 loss of 30–35%, 15% and 10%, respectively, in vegetables alone, and to that of about 10% when taking the total dish into account(Reference Bognár168,Reference Bognár170) . In chickpeas, microwave cooking, autoclaving and boiling caused a decline of 19%, 34% and 42% in vitamin B6 content, respectively(Reference Alajaji and El-Adawy187). The amount of vitamin B6 in potatoes is reduced by 30–57%, 21% and 10% during boiling, baking and deep frying, respectively(Reference Shibata, Yasuhara and Yasuda161,Reference Bognár169,Reference Roe, Church, Pinchen and Finglas188) . The way of cooking rice influences the content of vitamin B6. In different rice varieties, the boiling cooking method (cooking rice with extra water and then eliminating the water) led to vitamin losses of 3–74%, compared with the traditional cooking method (cooking with a constant amount of water without removing the water)(Reference Rezaei, Alizadeh Sani and Amini189). During breadmaking, the vitamin B6 content decreased on average by 33% and 62% in whole and white wheat bread, respectively, in comparison with whole and white wheat flour(Reference Batifoulier, Verny, Chanliaud, Rémésy and Demigné190,Reference Nurit, Lyan, Pujos-Guillot, Branlard and Piquet191) . Similar results were obtained during rye sourdough bread production(Reference Mihhalevski, Nisamedtinov, Hälvin, Ošeka and Paalme192). Toasting wheat bread induced an increase in vitamin B6 by 75% due to its release from glycosidic bound forms(Reference Nurit, Lyan, Pujos-Guillot, Branlard and Piquet191). Effects of extrusion techniques on vitamin B6 retention in cereal grains showed a reduction of 0–23% and of 65% in maize grits and oat whole grains, respectively(Reference Athar, Hardacre, Taylor, Clark, Harding and McLaughlin193). Drying of tarhana, a traditional Turkish fermented cereal food, resulted in vitamin B6 losses of 3%, 16% and 23% at temperatures of 50 °C, 60 °C and 70 °C, respectively(Reference Ekıncı194). A decrease in vitamin B6 content in nuts varied from 2–7.5% in almonds, up to 4–34% in pistachio nuts after roasting(Reference Bulló, Juanola-Falgarona, Hernández-Alonso and Salas-Salvadó195,Reference Stuetz, Schlörmann and Glei196) . Alkali-processing of corn grains to masa (nixtamalisation) resulted in a loss of 23% of vitamin B6 (Reference Gwirtz and Garcia-Casal145). The highly variable content of vitamin B6 in beer is affected by several factors, including raw materials and the brewing process(Reference Romanini, Rastelli, Donadini, Lambri and Bertuzzi197–Reference Bertuzzi, Mulazzi, Rastelli, Donadini, Rossi and Spigno199). Germination is an effective way to improve the nutrition value of edible seeds: increases of 54%, 78% and 26% in vitamin B6 content occurred in germinated lentils(Reference Zhang, De Silva, Dissanayaka, Warkentin and Vandenberg200), rough rice(Reference Moongngarm and Saetung201) and faba beans(Reference Khalil and Mansour202), respectively. Conversely, vitamin B6 levels decreased by 11%, 13% and 50% in germinated wheat(Reference Žilić, Basić, Hadži-Tašković Šukalović, Maksimović, Janković and Filipović203), brown rice(Reference Moongngarm and Saetung201) and sorghum(Reference Pinheiro, Anunciação and de Morais Cardoso204), respectively, after germination.

Food preservation and storage

Canning, a food conservation method, brought on a vitamin B6 reduction of 46%, 34%, 31% and 18% in mushrooms, whole peeled tomatoes, white asparagus and lentils compared with their respective unprocessed products(Reference Martin-Belloso and Llanos-Barriobero205). Ionising irradiation, a method used for food preservation, has a low effect on vitamin B6; losses ranging from zero in wheat to about 15% in fish were observed(Reference Kilcast206,Reference Woodside207) .

The amount of vitamin B6 in button mushrooms significantly declined by 23% and 45% after 6 and 12 months, respectively, during frozen storage at −20 °C(Reference Bernaś and Jaworska208). The content of vitamin B6 decreased gradually in aseptically packaged ultra-high temperature treated milk during storage at room temperature, resulting in a 96% loss after 20 weeks(Reference Oamen, Hansen and Swartzel183). No remarkable changes and a 20% decline in vitamin B6 content happened in vacuum-packaged broccoli au gratin and salmon, respectively, stored at room temperature, either on the Earth or exposed to spaceflight for 880 d; the vitamin content in flight samples did not degrade faster than that of ground controls(Reference Zwart, Kloeris, Perchonok, Braby and Smith209). The investigation of the influence of storage conditions on vitamin B6 retention in a freeze-dried tuna mornay meal (containing tuna, vegetables and pasta) fortified with that vitamin showed a mean decrease of 14% in the vitamin following storage at temperatures of 1 °C, 30 °C and 40 °C for up to 24 months(Reference Coad and Bui210). The vitamin B6 losses in meals in two hospital foodservice systems, the cook/hot-hold system, where food is held hot from the time of cooking to service, and the cook/chill system, where the cooked food is chilled, stored and reheated, have also been summarised and compared(Reference Williams211).

Industrial production of vitamin B6

Pyridoxine hydrochloride, which is mainly used in pharmaceutical preparations, dietary supplements and as an additive in food and feed, is manufactured by chemical synthesis(29,Reference McDowell37,60,Reference Spinneker, Sola, Lemmen, Castillo, Pietrzik and Gonzalez-Gross84,Reference Combs and McClung87,Reference Bonrath, Zhang, Pauling, Weimann, Bellussi, Bohnet, Bus, Drauz, Greim, Jackel, Karst, Kleemann, Kreysa, Laird, Meier, Ottow, Roper, Scholtz, Sundmacher, Ulber and Wietelmann158,Reference Fischesser, Fritsch, Gum, Karge and Keuper212–Reference Gum219) . All present-day industrial vitamin B6 syntheses use the Diels–Alder reaction of a diene (4,5-substituted oxazoles) and a dienophile (alkyldioxepins) as a key step(Reference Bonrath, Zhang, Pauling, Weimann, Bellussi, Bohnet, Bus, Drauz, Greim, Jackel, Karst, Kleemann, Kreysa, Laird, Meier, Ottow, Roper, Scholtz, Sundmacher, Ulber and Wietelmann158,Reference Eggersdorfer, Laudert and Letinois220–Reference Ledesma-Amaro, Jiménez, Revuelta, McNeil, Archer, Giavasis and Harvey225) . An alternative to the current chemical processes might be environmentally sustainable bioprocesses based on microbial vitamin B6 fermentation, which is of great interest to the biotechnological industry. Several attempts have been made to construct overproducing strains by genetic engineering of microorganisms such as Sinorhizobium meliloti, E. coli and Bacillus subtilis. Unfortunately, production levels are too low and are not cost effective. Therefore, major metabolic engineering efforts are still required for developing fermentation processes that could outcompete the chemical synthesis of vitamin B6. The main bottlenecks are insufficient activities of some enzymes in the biosynthetic pathway and accumulation of toxic intermediate metabolites(Reference Acevedo-Rocha, Gronenberg, Mack, Commichau and Genee226–Reference Richts and Commichau237).

Food fortification and biofortification with vitamin B6

Food fortification is defined as the practice of deliberately adding an essential micronutrient to food that is commonly consumed by the general population with the intention of improving the nutritional quality of the food supply and providing a public health benefit with minimal risk to health(Reference Cardoso, Fernandes, Gonzaléz-Paramás, Barros and Ferreira238–Reference Allen, De Benoist, Dary and Hurrell240). Foods fortified with vitamin B6, similarly to dietary supplements, constitute an additional dietary source of the vitamin(60,Reference de Pee150,Reference Bird, Murphy, Ciappio and McBurney241–Reference Ho, Quay, Devlin and Lamers246) . Overall, vitamin B6 deficiency is rare in the general healthy population(Reference Parra, Stahl and Hellmann8,29,Reference Jungert, Linseisen, Wagner and Richter44,Reference de Pee150,Reference Tucker, Olson, Bakun, Dallal, Selhub and Rosenberg243,Reference Ho, Quay, Devlin and Lamers246–Reference Brown, Ameer and Daley250) . It may be a concern in high-income as well as low-income countries in certain groups(Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142), such as older adults(Reference Tang, Xu and Shiu-Ming245,Reference Morris, Picciano, Jacques and Selhub251–Reference ter Borg, Verlaan and Hemsworth254) , people of low socio-economic status and those experiencing food insecurity(Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142,Reference Bird, Murphy, Ciappio and McBurney241,Reference Duvenage and Schönfeldt244,Reference Tang, Xu and Shiu-Ming245,Reference Brown, Ameer and Daley250) . As for 2022, some countries, mostly but not solely located in Africa, have mandatory fortification of wheat flour (most often), maize flour and/or rice with vitamin B6 (Nicaragua, Panama, Cuba, Peru, Jordan, Palestine, Nigeria, Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa)(255–Reference Swanepoel, Havemann-Nel and Rothman257). There is a voluntary fortification with vitamin B6 in many other countries, such as the USA, the Dominican Republic, Eswatini, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, the UK and countries of the European Union; the vitamin is added to various foods, such as atta, maida, rice, breakfast cereals, beverages and cereal-based foods for infants and young children(Reference da Silva, Gregory, Marriott, Birt, Stallings and Yates28,60,Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142,Reference de Pee150,Reference Berendsen, van Lieshout, van den Heuvel, Matthys, Péter and de Groot217,255,256,258–Reference Hannon, Kiely and Flynn265) .

Biofortification is a process of increasing the density of micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) in a crop and comprises (sensu stricto, that is, omitting agronomic practices) conventional plant breeding and genetic engineering approaches. It differs from fortification because it aims to make plant foods naturally more nutritive rather than adding nutrients to the foods during food processing. Biofortification is an ideal strategy to improve nutrition for rural and poor communities that rely on subsistence farming for nutrition or may not have access to diverse diets, supplements and fortified foods. Biofortification complements existing interventions and may help by increasing the daily adequacy of micronutrient intake among the most vulnerable micronutrient deficient people(Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142,Reference Malik and Maqbool239,Reference Bouis266–Reference Strobbe and Van Der Straeten268) . Vitamin B6 is de novo synthesised by plants, and therefore, biofortification could be a promising route to enhance food quality by increasing the vitamin levels in plants in the future(Reference Parra, Stahl and Hellmann8,Reference Vanderschuren, Boycheva, Li, Szydlowski, Gruissem and Fitzpatrick269–Reference Blancquaert, De Steur, Gellynck and Van Der Straeten271) . Analysis of the natural diversity of vitamin B6 content in wheat, rice and potato germplasm has shown limited variation, so breeding strategies do not seem to be adequate to increase the vitamin content in those crops(Reference Mangel, Fudge, Gruissem, Fitzpatrick and Vanderschuren68,Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142,Reference Shewry, Van Schaik and Ravel272,Reference Mooney, Chen, Kühn, Navarre, Knowles and Hellmann273) , in contrast to maize, where remarkable wide ranges in vitamin B6 levels among various genotypes were recently reported(Reference Azam, Lian, Liang, Wang, Zhang and Jiang274). Most efforts to date have used genetic engineering approaches. Biosynthesis of vitamin B6 is primarily controlled by two enzymes, making vitamin B6 biofortification an attractive target for plant geneticists. Overexpression of genes encoding one or both enzymes leads to the enhanced accumulation of vitamin B6 in transgenic plants compared with the untransformed ones: 0·86–1·25-fold in tobacco plants, 1·45–4-fold in Arabidopsis seeds, 0·16–34·96-fold in wheat seeds, 1·6–3·9-fold in rice seeds, 3–16-fold in cassava roots and 1·07–1·5-fold in potato tubers. Interestingly, enhancing vitamin B6 levels in plants may also positively affect their tolerance to environmental stress(Reference Chen and Xiong27,Reference Titcomb and Tanumihardjo142,Reference Strobbe and Van Der Straeten268–Reference Fudge, Mangel, Gruissem, Vanderschuren and Fitzpatrick270,Reference Herrero and Daub275–Reference Bagri, Upadhyaya, Kumar and Upadhyaya280) . All biofortification attempts revealed the feasibility of raising the vitamin B6 amounts in plants. So far, the vitamin B6 contents in transgenic plants are low and highly variable. Regardless, more research for understanding the regulatory mechanisms that control genes involved in the biosynthesis and metabolism of vitamin B6 in plants is needed(Reference Ledesma-Amaro, Jiménez, Revuelta, McNeil, Archer, Giavasis and Harvey225,Reference Vanderschuren, Boycheva, Li, Szydlowski, Gruissem and Fitzpatrick269) .

Pharmacokinetics of vitamin B6

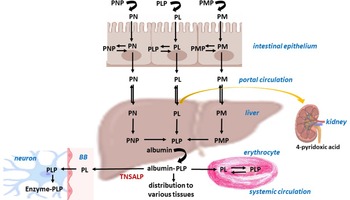

The total content of vitamin B6 in the adult human body is about 170 mg(Reference Coburn, Lewis, Fink, Mahuren, Schaltenbrand and Costill281). B6 vitamers are absorbed in the upper small intestine (jejunum) from diet and/or oral supplements. In addition to the dietary sources of the vitamin, humans might also receive vitamin B6 from bacterial microbiota in the large intestine as mentioned earlier(Reference Said88,Reference Hamm, Mehansho and Henderson282,Reference Said283) . All vitamin B6 analogues, that is, pyridoxine, pyridoxamine, and pyridoxal, are present in the diet. Phosphorylated forms undergo dephosphorylation by means of phosphatases prior to absorption into epithelial cells and prior to release into the portal system. Phosphorylated forms are poorly diffusible and, in fact, they are trapped in cells and a dephosphorylation step is necessary for their efflux. The bioavailability of vitamin B6 from supplements is about 95%, whereas the bioavailability of pyridoxin, pyridoxal and pyridoxamine is similar. The presence of fibre in plant sources reduces bioavailability by 5–10%, while the presence of pyridoxine glucoside reduces bioavailability by 75–80%. On average, the bioavailability of vitamin B6 from a mixed diet can be estimated to be about 75%. In fact, absorption in the intestine is mediated both via passive diffusion (that is, a large amount is readily absorbable without cell saturation) and a carrier mediated mechanism (that is, a saturable mechanism). In humans, there is carrier-mediated transport of B6 vitamers via the vitamin B1 (thiamine) transporters THTR1 and THTR2, which belong to the SLC19A2 and SLC19A3 families(Reference Yamashiro, Yasujima, Said and Yuasa284). The maximum concentration (C max) of pyridoxine is usually achieved within 5·5 h(Reference Surtees, Mills and Clayton285,286) . In the liver, all forms of dephosphorylated vitamin B6 are rephosphorylated and finally converted to pyridoxal 5′-phosphate in hepatocytes. Several enzymes, such as ATP-dependent pyridoxine/pyridoxamine/pyridoxal kinase, phosphatases and flavin mononucleotide–dependent pyridoxine phosphate oxidase (PNPO) are involved in these reactions. PNPO converts pyridoxine 5′-phosphate (PNP) and pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate (PMP) into pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) (Fig. 1b).

Pyridoxal phosphate further binds to albumin in the liver, and it is released into the circulation, where it forms approximately 60% of total circulating B6, with lesser amounts of all three dephosphorylated forms. After dissociation from albumin and dephosphorylation by alkaline phosphatase, free pyridoxal is taken up by erythrocytes and then trapped inside cells in the form of PLP(Reference Anderson, Fulford-Jones, Child, Beard and Bateman287–Reference Merrill, Henderson, Wang, McDonald and Millikan292).

Plasma PLP is the most common parameter for determination of vitamin B6 status. Its usual concentration is more than 30 nM in adults(Reference Leklem5). PLP is utilised as a cofactor of many enzymes related to a row of metabolic pathways(Reference Di Salvo, Contestabile and Safo293,Reference Lumeng and Li294) , as will be discussed later. Circulatory PLP passes into breast milk, and also crosses physiological barriers such as the placental and blood–brain barriers. The same mechanism, as in other organs, is described for brain entry and storage, that is, initial dephosphorylation in the blood–brain barrier by means of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP), followed by uptake and entrapping of the vitamin in neurons after phosphorylation to PLP(Reference Surtees, Mills and Clayton295).

The major inactive metabolite of PLP is 4-pyridoxic acid. It is formed in the liver and excreted in the urine (Fig. 2). Urinary excretion of this metabolite greater than 3 mmol/d can be used as a marker of adequate short-term vitamin B6 status. Its half-life appears to be 15–20 d(Reference Stanulović, Jeremić, Leskovac and Chaykin296).

Fig. 2. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin B6. The figure summarises the pharmacokinetics of vitamin B6 in the human body. PN, pyridoxine; PNP, pyridoxine 5′-phosphate; PL, pyridoxal; PLP, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate; PM, pyridoxamine; PMP, pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate; TNSALP, tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase; BB, blood–brain barrier.

There is not a large storage of vitamin B6 in tissues, probably owing to the fact that humans require only small amounts of vitamin B6 from food sources, since the biologically active form, PLP, can be formed not only by interconversion from different B6 vitamers but also using the cofactors from degraded enzymes in the salvage pathway.

Physiological function of vitamin B6

The active form of vitamin B6, PLP, acts as a coenzyme in more than 140 different enzymatic reactions necessary for vital cellular processes(Reference Parra, Stahl and Hellmann8). This function is enabled by the highly reactive aldehyde group of PLP, that forms Schiff bases with the ε amino groups of lysine residues at the active centres of PLP-dependent enzymes. Conversely, binding to lysine residues on some hormonal receptors is responsible for transcriptional modulation. Moreover, the aldehyde group can react with other amino acids in proteins, especially with cysteine or histidine(Reference Phillips297).

PLP is involved in various pathways, such as:

-

Some steps during the metabolism of amino acids, for example, transamination, decarboxylation and racemisation processes. Metabolic transformation of sulphur-containing amino acids, for example, the conversion of methionine to cysteine through the key intermediate homocysteine or S-adenosylmethionine. Elevated levels of circulating homocysteine in the blood are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, and S-adenosylmethionine is a methyl donor for many methylation reactions, for example, methylation of proteins, DNA and RNA, and others(Reference Brunton, Chabner and Knollman298–Reference Ereño-Orbea, Majtan, Oyenarte, Kraus and Martínez-Cruz301). In addition, cysteine synthesised by this transsulfuration pathway is an important contributor to glutathione synthesis, which plays a role in oxidative stress and the antioxidant defense system.

-

Some processes during carbohydrate metabolism, for example, the degradation of stored carbohydrates such as glycogenolysis, as PLP is a cofactor for glycogen phosphorylase. PLP also plays a role in the reactions that generate glucose from amino acids in the process known as gluconeogenesis(Reference Chang, Scott and Graves302–Reference Takagi, Fukui and Shimomura304).

-

Lipid metabolism, especially biosynthesis of sphingolipids, which are important for myelin formation and their breakdown(Reference Bourquin, Capitani and Grütter305).

-

Biosynthesis of many neurotransmitters, particularly the formation of serotonin from tryptophan and the synthesis of epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and dopamine (3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine) from phenylalanine and tyrosine. PLP also controls the formation and regulation of the inhibitory transmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the brain, and the neuromodulator serine(Reference Spinneker, Sola, Lemmen, Castillo, Pietrzik and Gonzalez-Gross84,Reference Allen, Neergheen and Oppenheim306–Reference Stephens, Havlicek and Dakshinamurti309) .

-

Catabolism of tryptophan and its conversion to niacin, that requires kynureninase, which also necessitates vitamin B6 (Reference Cervenka, Agudelo and Kynurenines310–Reference Ulvik, Midttun and McCann313).

-

Biosynthesis of tetrapyrroles (for example, haem). PLP is needed for the enzymatic reaction using succinyl-CoA and glycine to generate δ-aminolevulinic acid, an intermediate precursor in tetrapyrrole biosynthesis(Reference Haust, Poon, Carson, VanDeWetering and Peter314,Reference Mydlík and Derzsiová315) .

-

Immune and inflammatory pathways, especially regulation of cytokine production, particularly interferons and interleukin 6(Reference Meydani, Ribaya-Mercado, Russell, Sahyoun, Morrow and Gershoff316,Reference Ueland, McCann, Midttun and Ulvik317) .

Besides the role of PLP as a cofactor in biochemical reactions, vitamin B6 also plays other important roles in non-enzymatic functions, for example:

-

PLP inhibits enhancement in gene expression by steroid and thyroid hormones, and vitamins A and D by binding to lysine residues in hormone–receptor complexes(Reference Allgood and Cidlowski318,Reference Tully, Allgood and Cidlowski319) .

-

Antioxidative activity by scavenging reactive oxygen species and chelating of redox-active metal ions(Reference Bilski, Li, Ehrenshaft, Daub and Chignell320–Reference Matxain, Ristilä, Strid and Eriksson322).

Vitamin B6 deficiency and related disorders

Severe vitamin B6 deficiency resulting from inadequate intake (especially from dietary deficit) is rare in the healthy general population. Hypovitaminosis is usually found in association with other B vitamin deficiencies, such as those of folic acid (vitamin B9) and vitamin B12. As aforementioned, it should be emphasised that dietary vitamin B6 deficiency can occur in elderly people (aged 65 years and over)(Reference Bates, Pentieva and Prentice323). Secondary vitamin B6 deficiency is mostly a result of genetic disorders or drug interactions(Reference Plecko and Stöckler324,Reference Wilson, Plecko, Mills and Clayton325) .

Owing to the involvement of vitamin B6 in many metabolic pathways, a lack of sufficient amounts of vitamin B6 vitamers causes various biochemical changes and may lead to significant health problems. In particular, PLP is essential in the synthesis and metabolism of amino acids and neurotransmitters. Loss of function of the PLP-dependent enzyme glutamate decarboxylase leads to decreased levels of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.

Vitamin B6 deficiency in humans is associated with seborrheic dermatitis and cheilosis (including cracks at the corners of the mouth), glossitis with ulceration, anaemia, sensory polyneuropathy, depression, decreased immune function and increased risk of cardiovascular diseases. In children, characteristic symptoms of deficiency are abnormalities in hearing and seizures.(Reference Spinneker, Sola, Lemmen, Castillo, Pietrzik and Gonzalez-Gross84) Seizures are the results of an imbalance between excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) neurotransmitters(Reference Gospe, Olin and Keen326–Reference Kurlemann, Ziegler, Grüneberg, Bömelburg, Ullrich and Palm328).

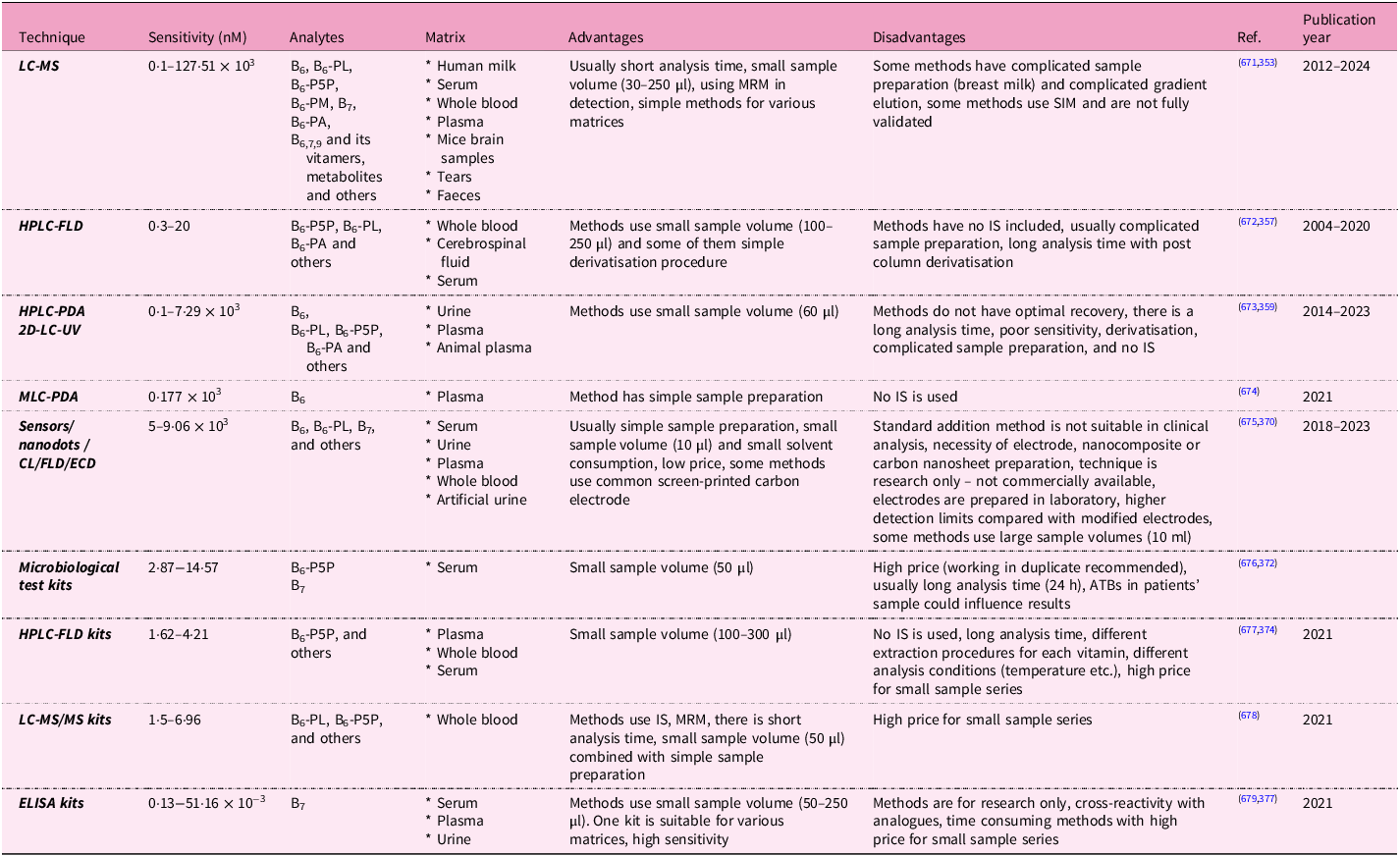

In the population, there are certain groups of people at increased risk of vitamin B6 inadequacy. People with impaired absorption, especially due to malabsorption syndromes (usually associated with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) and after bariatric surgery, have low vitamin B6 levels. Patients with renal disease, predominantly with chronic renal insufficiency undergoing dialysis, and liver disease tend to have low plasma PLP concentrations. Also, alcoholics need vitamin B6 supplementation because alcohol is metabolised to acetaldehyde, which decreases PLP formation in cells and competes with PLP for protein binding. Additional groups at risk of vitamin inadequacy despite adequate dietary intakes are not solely elderly persons but also those with autoimmune disorders (for example, rheumatoid arthritis), those who are obese and in pregnancy, or those who are taking oral contraceptives(Reference Chiang, Selhub, Bagley, Dallal and Roubenoff329–Reference Salam, Zuberi and Bhutta332). Analytical methods for the detection of vitamin B6 are summarised in Table 2. More details are shown in Supplementary Data Table S2, which evaluates individual specific methodologies with the relevant citations from which the information was obtained.

Table 2. Summary of analytical methods for the assessment of vitamins B6 and B7 in biological fluids

B6, pyridoxine; B6-PL, pyridoxal; B6-P5P, pyridoxal-5-phosphate; B6-PM, pyridoxamine; B6-PA, pyridoxic acid; B7, biotin; B9, folic acid; ATB, antibiotic; CL, chemiluminescence; ECD, electrochemical detection; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FLD, fluorescence detection; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; IS, internal standard; LC-MS, coupling of liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry; MLC, micellar liquid chromatography; MRM, multiple reaction monitoring; MS, mass spectrometer; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry; PDA, photodiode array detection; SIM, selected ion monitoring; 2D-LC, two-dimensional liquid chromatography.

Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy

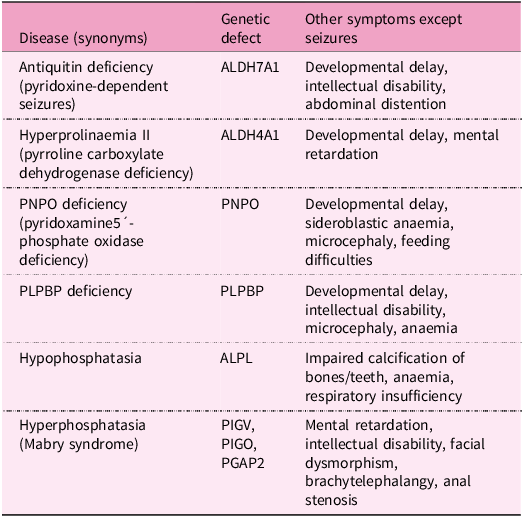

Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy (pyridoxine-dependent seizures, vitamin B6-responsive epilepsy) is a rare inherited metabolic disease characterised by recurrent seizures with their onset usually in prenatal, neonatal and postnatal periods or in childhood. Seizures are caused primarily by low levels of GABA due to PLP deficiency, nevertheless, other abnormalities are involved, for example, low levels of adenosine and methionine cycle defects. This type of epilepsy responds to high intravenous doses of vitamin B6, either as pyridoxine or as its active form PLP, but are resistant to conventional antiepileptic drugs(Reference Pena, MacKenzie and Van Karnebeek333). Decreased PLP availability in this disease is caused by mutations in some genes involved in vitamin B6 metabolism, for example:

-

Mutations in ALDH7A1, a gene encoding antiquitin, the enzyme with α-aminoaddipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase activity, involved in lysine degradation. Antiquitin deficiency leads to the accumulation of the toxic lysine intermediates α-aminoadipic semialdehyde and 1-piperideine-6-carboxylic acid, inactivating PLP by chemical complexation(Reference Mills, Struys and Jakobs334–Reference Striano, Battaglia and Giordano336).

-

Mutations in the ALDH4A1 gene occurring in metabolic disease hyperprolinaemia II causes the formation of pyrroline-5-carboxylate, a compound structurally similar to 1-piperideine-6-carboxylic acid, that also leads to the inactivation of PLP(Reference Farrant, Walker, Mills, Mellor and Langley337,Reference Walker, Mills, Mellor, Langley and Farrant338) .

-

Mutations in the PNPO gene influencing PLP recycling and synthesis(Reference Guerin, Aziz, Mutch, Lewis, Go and Mercimek-Mahmutoglu339–Reference Ruiz, García-Villoria and Ormazabal341).

-

Mutations in the pyridoxal phosphate-binding protein (PLPBP) gene (formerly called proline synthetase co-transcribed homolog). PLPBP protects PLP from damage by intracellular phosphatases(Reference Darin, Reid and Prunetti342–Reference Tremiño, Forcada-Nadal and Rubio345).

-

Mutations in the ALPL gene encoding tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP) in the metabolic disorder hypophosphatasia(Reference Nur, Çelmeli, Manguoğlu, Soyucen, Bircan and Mıhçı346).

-

Mutations in the PIGV, PIGO and PGAP2 genes responsible for the development of hyperphosphatasia with seizures and neurologic deficit (Mabry syndrome). These genes play a crucial role in the production of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor that binds TNSALP to the cell membrane. Mutations result in the production of non-functional glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors and the subsequent release of TNSALP into the blood(Reference Thompson, Roscioli and Marcelis347).

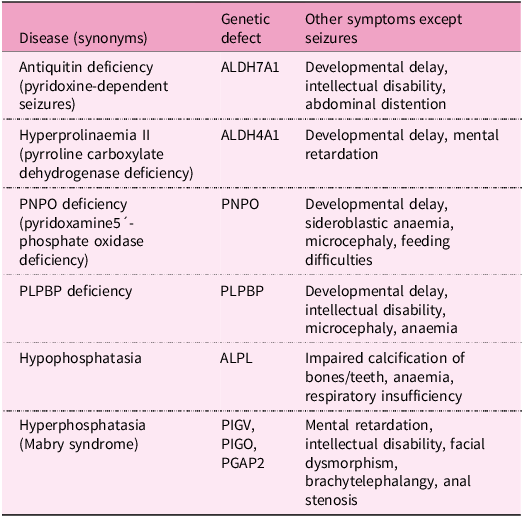

These metabolic diseases associated with defects in vitamin B6 are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. Inborn metabolic disorders related to pyridoxine dependent seizures

Clinically used drugs as antivitamins for B6

In addition to natural antivitamins for B6, there are also certain clinically used drugs that have the same effect. Drugs such as theophylline (a bronchodilator used in the treatment of respiratory diseases, for example, asthma) and caffeine (psychostimulant) directly inhibit pyridoxal kinase, the enzyme involved in activation of PLP. In the case of caffeine, such effects are probable solely in intoxication. The result is a PLP deficiency with accompanying reduction in PLP-dependent enzyme activities. Known consequences include neurotoxic reactions, for example, peripheral neuropathy, restlessness, agitation, tremors and seizures(Reference Glenn, Krober, Kelly, McCarty and Weir348–Reference Weir, Keniston, Enriquez and McNamee350). It should be mentioned that standardised extracts from Ginkgo biloba are easily available and used in the therapy of a number of conditions, such as peripheral circulatory disturbances, dizziness and tinnitus, etc.(Reference Azuma, Nokura, Kako, Kobayashi, Yoshimura and Wada98,Reference Gandhi, Desai and Ghatge351,Reference Jang, Roh, Jeong, Kim and Sunwoo352) . Hydrazine derivatives, beyond the aforementioned gyromitrin, also include the antituberculosis drug isoniazid (isonicotinic acid hydrazide). Administration of this drug, particularly in overdose, results in not only the inhibition of pyridoxal kinase by the isoniazid metabolite (hydrazone) but also the inactivation of PLP by other isoniazid metabolites (hydrazines and hydrazides), that form, for example, isonicotinilhydrazide, a compound that is easily excreted in the urine(Reference Kook, Cho, Lee, Lee and Lee353). Another antituberculosis drug, cycloserine, reacts with PLP forming covalent complexes that might inhibit pyridoxal kinase(Reference Court, Centner and Chirehwa354). Another group of drugs, including penicillamine and levodopa, form complexes with PLP, but they do not inhibit pyridoxal kinase(Reference Leon, Spiegel, Thomas and Abrams355,Reference Smith and Gallagher356) . In addition, antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin, valproic acid, and carbamazepine) increase the metabolism of vitamin B6 vitamers, resulting in low PLP plasma levels(Reference Linnebank, Moskau and Semmler357).

Dietary recommendation and pharmacological use of vitamin B6

Vitamin B6 is available in both multivitamin preparations with other B vitamins and as a single vitamin preparation. Oral tablets or solutions for parenteral (intravenous, intramuscular) administration are the most common forms; they usually contain pyridoxine hydrochloride or sometimes PLP.

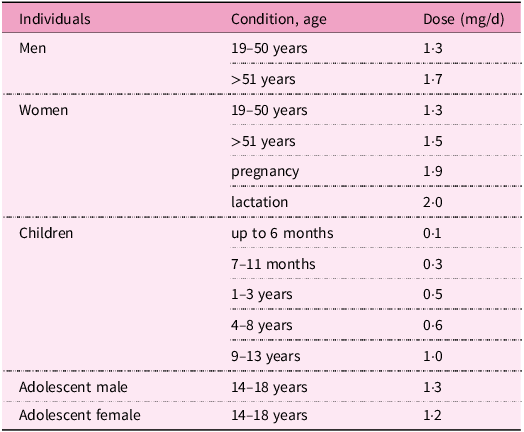

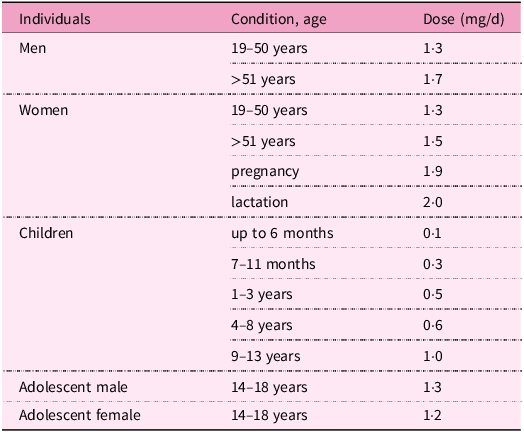

In adults, the current recommended dietary allowances range between 1·3–2·0 mg/d. During pregnancy, lactation and in the elderly, this requirement is increased(286). Recommendations for pyridoxine intake according to age and gender are listed in Table 4.

Table 4. Recommendations for vitamin B6 intake by gender and age(286)

As a supplement, vitamin B6 is used especially in cases of its deficiency, which may be due to insufficient intake or increased need, as specified earlier. As a medication, pyridoxine or PLP are given prophylactically or therapeutically to patients with pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy. In newborns with hereditary syndrome, it is necessary to administer this vitamin in the first week of life to prevent mental retardation or anaemia, and lifelong therapy is necessary. In the literature, however, there is a lack of congruence regarding dose recommendations. The optimal dosage should ensure the control of epileptic seizures, and, at the same time, the absence of side effects in a particular patient. In fact, adequate dosage of pyridoxine requires an individualised regimen according to the desired goal of therapy and tolerance of adverse effects.

Higher doses of pyridoxine are initially administered, for example, in newborns 200 mg/d orally, and are usually gradually reduced to a tolerated level as part of maintenance therapy, for example, 50–100 mg/d after 1 week. Oral therapy with the active metabolite PLP is also successful in some types of seizures, for example, due to mutations in PNPO. Vitamin B6 might improve certain congenital PLP-enzymopathies such as cystathioninuria and homocystinuria with accompanying vitamin B6 deficiency(286,Reference Pena, MacKenzie and Van Karnebeek333,Reference Guerin, Aziz, Mutch, Lewis, Go and Mercimek-Mahmutoglu339,Reference Huemer, Kožich and Rinaldo358) .

Pyridoxine is also used as an antidote, in cases of overdose with B6 antivitamins, such as isoniazid, cycloserine and penicillamine, as well as in cases of poisonings with Gyromitra mushroom and Ginkgo biloba seeds. It is also recommended in ethylene glycol poisoning, because, as a cofactor, it is able to improve the conversion of glyoxylic acid, a toxic metabolite, into glycine(Reference Lheureux, Penaloza and Gris359). Vitamin B6 is sometimes given prophylactically in drug-induced deficiencies (for example, due to isoniazid) to prevent the development of peripheral neuritis(Reference Snider360).

In addition, this vitamin can be prescribed for the treatment of a number of other health conditions associated with vitamin B6 deficiency, including sideroblastic anaemia(Reference Mydlík and Derzsiová315). Supplementation reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases as vitamin B6 seems to have cardiovascular protective effects via mechanisms related to homocysteine, tryptophan–kynurenine pathways and increased levels of carnosine or anserine, which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties(Reference Kumrungsee, Nirmagustina and Arima361). Furthermore, pyridoxine is used empirically, for example, in nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, premenstrual syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome and rheumatic arthritis(Reference Aufiero, Stitik, Foye and Chen362–Reference Roubenoff, Roubenoff and Selhub364).

Recent studies indicate that vitamin B6 also exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects and may have a beneficial effect on preventing diseases linked to inflammation (for example, rheumatoid arthritis, acute pancreatitis, cardiovascular diseases and psoriasis) or could be an effective therapeutic agent in this field. Although the connection between vitamin B6 and inflammation is evident, the specific mechanisms involved often remain unclear. Identification of potential therapeutic targets, signalling pathways and inflammatory markers provide a valuable foundation for further research in this area(Reference Bai, Cheng, Yang, Zhang and Tian365–Reference Hellmann and Mooney369).

Toxicity of vitamin B6

Because vitamin B6 is a water-soluble compound not substantially stored in the body, redundant amounts are quickly excreted in the urine. Hence, its low potential toxicity is anticipated. Indeed, it is not possible to get toxic levels of vitamin B6 through diet alone. Taking supplements of vitamin B6 in appropriate doses (see Table 4) is considered to be relatively safe. Mild adverse effects include nausea, headache, fatigue and drowsiness; dermatological lesions can be observed(Reference Cohen and Bendich370). However, toxicity can occur after long-term administration of supplements with high vitamin B6 content. Therefore, a daily tolerable upper intake level for safe dosage was introduced by the European Food Safety Authority(Reference Allergens and Turck371). The tolerable upper intake level of vitamin B6 for adults is 12 mg/d (including pregnant and lactating women) and in children 1–3 years old is 3·2 mg/d, 4–6 years old is 4·5 mg/d, 7–10 years old is 6·1 mg/d, 11–14 years old is 8·6 mg/d and 15–17 years old is 10·7 mg/d.

Long-term supplementation with doses above the tolerable upper intake level may result primarily in peripheral neuropathy with neurological symptoms including pain in extremities, muscle weakness, ataxia and paraesthesia. Symptoms of toxicity are reversible after withdrawal, but some signs may still persist for 3–6 weeks. Paradoxically, these neurological symptoms of polyneuropathy after supplementation of high doses are similar to those of vitamin B6 deficiency. High levels of pyridoxine (inactive form) are thought to inhibit pyridoxine-phosphate dependent enzymes by competing with the biologically active form of vitamin B6, that is, PLP. The vitamer that is responsible for neurotoxicity is pyridoxine, because it competitively inhibits GABA neurotransmission, which may lead to neurodegeneration(Reference Hadtstein and Vrolijk372–Reference Vrolijk, Opperhuizen, Jansen, Hageman, Bast and Haenen375).

Biotin – vitamin B7

An introduction to biotin

Biotin, also known as vitamin B7 or vitamin H, is a water soluble and essential micronutrient for all organisms. The first observations related to biotin occurred in 1916 when English biochemist W. G. Bateman identified a condition characterised by neuromuscular symptoms, severe dermatitis and hair loss in rats fed a diet in which the only source of protein was raw egg white(Reference Hardman, Limbird and Gilman376). Cooking of the egg or administering yeast or liver to rats was able to revert this syndrome. Later, in 1936, Kögl and Tönnis isolated a factor present in egg yolk that was essential for yeast growth, and they named it biotin. Subsequent findings revealed that biotin was responsible for the protection against egg white toxicity, and this toxicity was attributed to avidin, a glycoprotein found in raw egg white that binds to biotin with very high affinity and prevents its absorption(Reference Hardman, Limbird and Gilman376,Reference Green, Wilchek and Bayer377) .

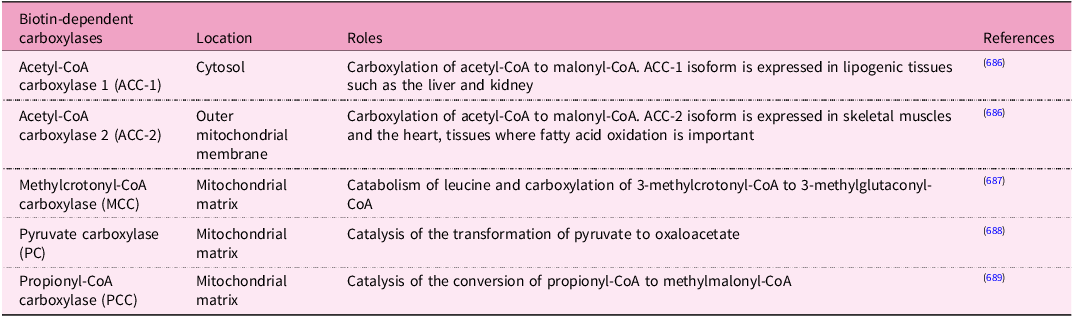

Humans obtain biotin from both food and via bacterial synthesis in the large intestine. Biotin is a cofactor for five carboxylases involved in metabolic processes(Reference Pacheco-Alvarez, Solórzano-Vargas and Del Río378). Other functions include biotinylation of histones, gene regulation and cell signalling(Reference Zempleni, Wijeratne and Kuroishi379).

Chemical structure and adequate intake level

In 1942, Vigneaud and his colleagues identified the chemical structure of biotin (Fig. 1c). Biotin can exist in eight stereoisomers due to three asymmetric centers, but D-(+)-biotin is the solely biologically active stereoisomer. At physiological pH, biotin exists mainly in its anionic de-protonated form because its pKa is 4·5(Reference Said380,Reference du Vigneaud, Melville and Folkers381) .

In the 1930s, experiments on biotin biosynthesis started with studies about the nutritional requirements of microorganisms(Reference Vandamme382). Eisenberg et al. explored the pathway of biotin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli (Reference Eisenburg, Mee, Prakash and Eisenburg383,Reference Rolfe and Eisenberg384) . In fact, certain microorganisms, such as mentioned Escherichia and Staphylococcus aureus, synthesise biotin. In these microorganisms, biotin is synthesised by enzymes encoded in the bio operon, whose transcription is regulated by the biotin retention protein A. This protein acts as both a biotin-dependent transcriptional repressor that regulates biotin biosynthesis and an enzyme that catalyses the attachment of biotin to biotin-dependent enzymes(Reference Satiaputra, Shearwin, Booker and Polyak385).

Interestingly, there are differences among bacterial species. For instance, Staphylococcus aureus responds to environmental biotin and grows when a media is supplemented with biotin, while Mycobacterium tuberculosis obtains biotin only through de novo synthesis(Reference Satiaputra, Eijkelkamp, McDevitt, Shearwin, Booker and Polyak386). In contrast, animal cells are not capable of synthesising biotin by their own enzymes. Hence, biotin must be absorbed from the diet.

When analysing biotin content in different foodstuffs, it is necessary to consider that values vary according to the origin of foods and the methodology used to determine biotin. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)/avidin-binding assays have a higher specificity than microbiological assays. The latter method tends to overestimate biotin content(Reference Staggs, Sealey, McCabe, Teague and Mock387).

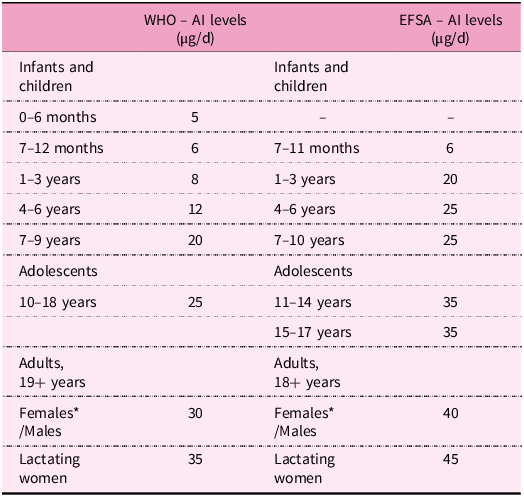

In the 1980s, doses of 35 μg/d for infants and 150–300 μg/d for adults were considered safe. Despite decades of investigation, there is still no consensus about the ideal daily intake of biotin(388). Nonetheless, the World Health Organization (WHO) established adequate intake (AI) levels for humans dependent on life stage and gender (Table 5)(389). AI for adults ranges between 30 and 40 μg/d. In the case of breastfeeding women, an additional 5 μg is required to compensate for the needs of this stage(389,390) . The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recommends higher values, namely 40 μg/d for adults and pregnant women and 45 μg/d for breastfeeding women. In the case of children (1–17 year olds), AIs also increase with age, ranging from 20 to 35 μg/d (Table 5)(390).

Table 5. Adequate intake level of biotin by life stage according to WHO and EFSA

Human bacterial microflora in the large intestine is also an important source of biotin for humans. However, its quantitative contribution remains unknown(Reference Said380). Interestingly, around 30% of the gut microbes cannot synthesise biotin even if it is essential for them(Reference Rodionov, Arzamasov and Khoroshkin391). Regardless, the microbiota in the human large intestine must synthesise significant amounts of biotin because biotin faecal excretion has been observed to exceed its dietary intake. Identification of a specific carrier-mediated mechanism for biotin uptake in human-derived colonic epithelial cells in vitro has been reported. It could locally contribute to the nutritional needs of the colonocytes, but it does not seem to contribute principally to the total quantity of absorbed biotin. This is supported by some observations, for example, urinary excretion varies with biotin dietary intake, whereas faecal excretion is independent of it. Conversely, it has recently been reported that bariatric surgery is associated with an increased abundance of bacterial biotin producers in the gut and improved systemic biotin status in humans. Thus, it is still controversial and unclear if and to what extent biotin produced by gut microorganisms can contribute to meet human needs for this vitamin. Moreover, the contribution of microbial biotin synthesis in the gut has never been quantified. It is considered that biotin requirements must be met mainly by diet(Reference Magnusdottir, Ravcheev, de Crecy-Lagard and Thiele22,Reference Basu and Donaldson80,Reference Said88,Reference Uebanso, Shimohata, Mawatari and Takahashi90–Reference Rodionov, Arzamasov and Khoroshkin93,Reference Said283,Reference Zempleni and Mock392–Reference O’Keefe, Ou and Aufreiter406) .

Sources of biotin

Natural sources of biotin

Biotin biosynthesis occurs in bacteria, archaea, plants and fungi. Animals and humans, as well as many protozoa, cannot synthesise the vitamin and depend on its exogenous supply(Reference Roje14,Reference Magnusdottir, Ravcheev, de Crecy-Lagard and Thiele22,Reference Scott, Ciulli and Abell26,Reference Rodionov, Arzamasov and Khoroshkin93,Reference Satiaputra, Shearwin, Booker and Polyak385,Reference Lin and Cronan407–Reference Zhang, Xu and Guan457) . In the human diet, biotin is present in many foods in variable amounts. Major dietary sources include eggs, or precisely egg yolk, milk and dairy products, nuts (for example, almonds, peanuts, and walnuts), legumes (soyabeans and lentils), mushrooms, some vegetables (for example, cauliflower, cabbage, broccoli, spinach and sweet potatoes), cereals, meat and some fruit (for example, avocados, raspberries and bananas). Yeast and offal (liver and kidney), in addition to egg yolk, are very rich in biotin (Supplementary Fig. S1)(Reference Chawla, Kvarnberg, Biller and Ferro30,Reference Hall, Moore and Morgan40,Reference Strain, Hughes, Pentieva, Ward, Hoey, McNulty, Biesalski, Drewnowski, Dwyer, Strain, Weber and Eggersdorfer83,Reference Schroeder152,Reference Roe, Church, Pinchen and Finglas188,Reference Staggs, Sealey, McCabe, Teague and Mock387,Reference Combs, McClung, Combs and McClung393–395,Reference Jungert, Ellinger, Watzl and Richter397,Reference Ball399,Reference Outten447,Reference McDowell458–Reference Murakami, Takakura and Yamano472) . It has also been observed that the biotin nutritional status of both lactoovovegetarians and vegans is not impaired compared with people consuming a mixed diet(Reference Lombard and Mock473).

Biotin in foods is found as free biotin and as biocytin (biotinyl-lysine) bound in proteins. After proteolysis, biotin is released from biocytin by biotinidase (see also below the chapter Absorption). The proportion of free and bound vitamin forms varies among foods. For example, the majority of biotin in meats, yeast and cereals appears to be protein-bound; in milk, however, the vitamin occurs nearly exclusively in the free form. At present, there are no reliable data on the average bioavailability of biotin from a usual mixed diet. Experiments using pharmacologic doses of free biotin revealed a bioavailability of biotin approaching 100%. Also, a human kinetic study showed that intravenous administration and oral administration may have the same urinary recoveries. There is, however, a lack of data on the degree of biotin absorption from the protein-bound form(Reference Basu and Donaldson80,Reference Zempleni and Mock392–Reference Jungert, Ellinger, Watzl and Richter397,Reference Ball399,Reference Hayakawa, Katsumata and Abe464,Reference Zempleni and Mock474,Reference Zempleni, Wijeratne and Hassan475) .

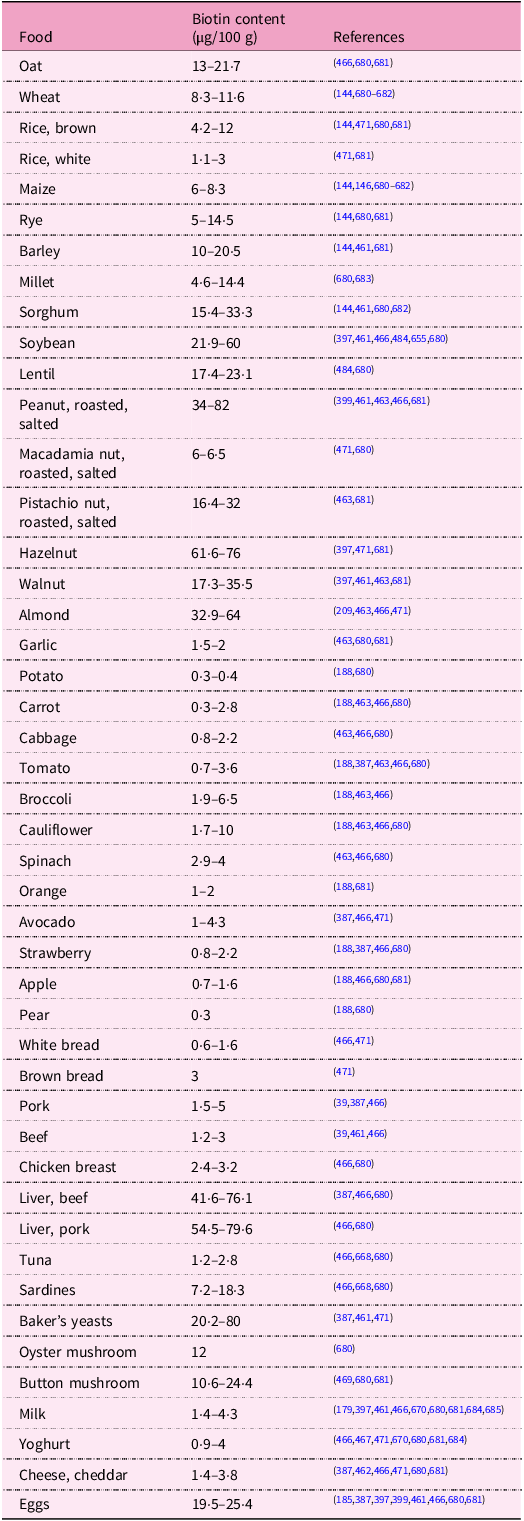

Data on the biotin content in foods is limited and is not ordinarily published in different food composition databases (for example, in the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference). Both natural variation and analytical aspects may account for the sometimes-reported high variability of biotin contents(Reference Staggs, Sealey, McCabe, Teague and Mock387,Reference Combs, McClung, Combs and McClung393,395,Reference Eitenmiller, Eitenmiller, Landen and Ye396,398,Reference Watanabe, Kioka, Fukushima, Morimoto and Sawamura466,Reference Ebara, Sawamura, Negoro and Watanabe470,476) . Biotin amounts in some selected foodstuffs are presented up in Table 6.

Table 6. Biotin content in selected foodstuffs

A natural antagonist of biotin – avidin

The most prominent natural antagonist of biotin is the above-mentioned avidin, a glycoprotein in raw egg white with a high affinity for biotin. Avidin binds biotin in a tight non-covalent complex preventing its absorption in the small intestine and thereby making it unavailable. The binding of biotin to avidin is the strongest known non-covalent bond in nature. The complex can neither be broken (that is, to release biotin) because it is resistant to digestive proteases and is undissociated over a wide range of pH, and neither is it absorbed (that is, as the intact complex molecule) in the intestine. Nutritionally, the binding phenomenon has, however, little impact, since heating to at least 100 °C during cooking denatures avidin, destroying the avidin–biotin complex and releasing the vitamin for absorption, as well as preventing additional complex formation. The consumption of raw or undercooked whole eggs is probably of little consequence for nutrition, as the biotin-binding capacity of avidin in the egg white is roughly comparable to the biotin content of the egg yolk. Similarly, raw egg white, if added to foods without further cooking or ingested with cooked food, provides avidin that binds the low amounts of biotin in food. Experimentally, it has been shown in humans that a diet containing 30 g of raw egg white per 100 g dry weight diet induces biotin deficiency(Reference Basu and Donaldson80,Reference Combs, McClung, Combs and McClung393,394,Reference Eitenmiller, Eitenmiller, Landen and Ye396,Reference Jungert, Ellinger, Watzl and Richter397,Reference Bonjour405,Reference Lanska477,Reference Mock, Henrich-Shell, Carnell, Stumbo and Mock478) .

Effects of food processing on biotin content

Processing may influence the content of biotin in foods(Reference Berry Ottaway, Skibsted, Risbo and Andersen134,Reference Godoy, Amaya-Farfan, Rodriguez-Amaya, Rodriguez-Amaya and Amaya-Farfan135,Reference Lešková, Kubíková, Kováčiková, Košická, Porubská and Holčíková163) . However, in contrast to other B vitamins, there is little available data on how food processing affects biotin content. A rough overview of data on biotin losses in some food groups due to processing is given in Table S3 in Supplementary Data. More data on specific foods, information on conditions and comments are mentioned later in the article.

Milling and refining of cereals

Milling and refining cereal grains bring on a substantial decline in biotin due to removing grain parts rich in micronutrients.(Reference Hegedüs, Pedersen and Eggum144) Biotin amounts in refined wheat, rye, barley and sorghum flours decrease, depending on the degree of milling, by 7–77%, 8–69%, 5–78% and 7–72% in comparison with whole grain flours, respectively(Reference Hegedüs, Pedersen and Eggum144). Likewise, the content of biotin in various maize milled products is reduced by 20–81% as compared with whole kernels(Reference Hegedüs, Pedersen and Eggum144,Reference Dunn, Jain and Klein146,Reference Suri and Tanumihardjo479) . Biotin losses in non-parboiled and parboiled white rice are 47–86% and 49%, respectively, compared with brown rice(Reference Tiozon, Fernie and Sreenivasulu148,Reference Kyritsi, Tzia and Karathanos149,Reference Schroeder152,Reference Muthayya, Hall and Bagriansky480) .

Properties of biotin and mechanisms of vitamin loss during food processing

Biotin is soluble in water and generally regarded as having good stability, being fairly stable to air (oxygen), light and heat. It can, however, be gradually decomposed by ultraviolet radiation. Biotin is relatively stable in weak acid or alkaline solutions (pH 4–9), whereas it can be broken down in strong acid or alkaline solutions by heating(Reference Berry Ottaway, Skibsted, Risbo and Andersen134,Reference Godoy, Amaya-Farfan, Rodriguez-Amaya, Rodriguez-Amaya and Amaya-Farfan135,Reference Henry and Heppell147,Reference Schnellbaecher, Binder, Bellmaine and Zimmer154,Reference Ferguson, Emery, Price-Davies and Cosslett157,Reference Lešková, Kubíková, Kováčiková, Košická, Porubská and Holčíková163,Reference Riaz, Asif and Ali165,394,Reference Eitenmiller, Eitenmiller, Landen and Ye396,Reference Bergström481) . Losses of biotin during the processing of foods are more related to leaching, although some thermal degradation may also occur(Reference Godoy, Amaya-Farfan, Rodriguez-Amaya, Rodriguez-Amaya and Amaya-Farfan135,Reference Bergström481) . In contrast to other water-soluble vitamins, biotin is not so prone to leaching because it exists in foods at least partly in a protein-bound form, not likely enabling leaching into cooking liquids(Reference Lešková, Kubíková, Kováčiková, Košická, Porubská and Holčíková163,Reference Eitenmiller, Eitenmiller, Landen and Ye396,Reference Schweigert, Nielsen, Mclntire and Elvshjem482) .

Processing of animal-based foods

Biotin losses in pork, beef, chicken and fish were estimated to be 20–30% during boiling, steaming and braising, 15% during frying, and only 10% during all cooking methods, if the vitamin contents in soup, gravy and drippings are taken into consideration (that is, the total dish)(Reference Bognár170,Reference Bergström481) . Boiling, poaching and frying of eggs lowered biotin content by 14%, 22% (higher losses owing to leaching into water) and 7%, respectively(Reference Roe, Church, Pinchen and Finglas185). Boiling, pasteurisation, ultra-heat treatment and evaporation of milk do not substantially reduce biotin levels; losses are usually negligible, at about 0–10%(Reference Lešková, Kubíková, Kováčiková, Košická, Porubská and Holčíková163,Reference Bognár170,Reference Bergström481,Reference Graham483) .

Processing of plant-based foods

Estimated decreases in biotin content in vegetables are 30%, 15% and 10%, due to boiling, steaming, and frying, respectively, and 10% if the cooking water is not discarded(Reference Bognár170). Therefore, steaming, compared with boiling, is associated with lower biotin loss. For example, boiling and steaming lessened biotin amounts in broccoli by 14·5% and 7·5%, respectively(Reference Roe, Church, Pinchen and Finglas188). In legumes, mean biotin losses of 5% after cooking for 20 min and 5–12% after pre-soaking and cooking for 20–150 min occurred. The duration of pre-soaking (for 1 or 16 h) did not affect biotin retention, whereas cooking time did(Reference Hoppner and Lampi484). Biotin amounts in hazelnuts and walnuts decreased by 10% and 32%, respectively, during baking(Reference Macova and Krkoskova485). Biotin losses of 10–25% during extrusion processing were reported(Reference Riaz, Asif and Ali165).

Food preservation and storage

The contents of biotin were 40–77% lower in canned vegetables, such as carrots, tomato, spinach, corn and green peas, compared with raw vegetables(Reference Schroeder152). Ionising radiation, which is used for food preservation, causes little or no loss of biotin; irradiation of wheat to 2 kGy resulted in a loss of 10% after 3 months of storage(Reference Kilcast206).

Biotin in vacuum-packaged broccoli au gratin and almonds was stable during storage at room temperature either on the Earth or exposed to spaceflight for 880 d(Reference Zwart, Kloeris, Perchonok, Braby and Smith209). No change in the content of biotin in spray-dried milk powder happened during storage for 8 weeks at 60 °C. At 70 °C, the biotin level remained constant for the first 2 weeks of storage and then declined by 25% in the next 6 weeks. Biotin content in milk powder was unchanged after storage for 15 weeks in an oxygen or nitrogen atmosphere(Reference Ford, Hurrell and Finot486). No biotin loss occurred in foods stored at −20 °C or −80 °C for 4 weeks(Reference Teague, Sealey, McCabe-Sellers and Mock487).

Industrial production of biotin

Industrial production of biotin is currently based on chemical synthesis because its isolation from natural sources is not (owing to very low concentrations) economically feasible. The majority of produced biotin is used in feed (about 90% of annual production(Reference Outten447,Reference Bonrath, Peng, Dai, Bellussi, Bohnet and Bus488) , as a feed additive to prevent vitamin deficiency for animal health, welfare and performance(Reference Outten447,Reference McDowell458,Reference Bonrath, Peng, Dai, Bellussi, Bohnet and Bus488–Reference Blum511) ), pharmaceutical, food (for dietary supplements and food fortification)(Reference Outten447,Reference Bonrath, Peng, Dai, Bellussi, Bohnet and Bus488,Reference Laudert, Hohmann and Moo-Young508,Reference Lipner512–Reference Fujimoto, Inaoki, Fukui, Inoue and Kuhara518) and cosmetic industries(Reference Bonrath, Peng, Dai, Bellussi, Bohnet and Bus488,Reference Patel, Swink and Castelo-Soccio519–Reference Fiume521) . Only a minor portion is used for analytical purposes in the context of biotin–avidin/streptavidin technology(Reference Bonrath, Peng, Dai, Bellussi, Bohnet and Bus488,Reference Seki507,Reference Wang, Hossain and Han522–Reference Gifford, de Koning and Sadrzadeh529) .

As above-mentioned, solely one biotin stereoisomer from 8 possible is active. Biotin manufacturing makes use of costly stereoselective multistep chemical synthesis, which was first achieved in the late 1940s and since then has still been improved. Alternative syntheses have also been investigated and developed(Reference Eggersdorfer, Laudert and Letinois220,Reference Bonrath and Netscher221,Reference Combs, McClung, Combs and McClung393,Reference Outten447,Reference Bonrath, Peng, Dai, Bellussi, Bohnet and Bus488,Reference Seki507,Reference Casutt, Koppe, Schwarz, Bellussi, Bohnet and Bus530–Reference Seki, Hatsuda, Mori, Yoshida, Yamada and Shimizu534) . The production of biotin by fermentation has for a long time attracted considerable interest from researchers owing to economic and environmental sustainability concerns about the chemical process. Random mutagenesis and selection, as well as genetic engineering, have been used to remove metabolic obstacles and bottlenecks for obtaining high-producing biotin microbial strains. However, to be cost-effective, it is assumed that any commercial bioprocess requires microbial strains that produce significantly more than 1 g biotin per liter in 12–24 h of fermentation and use a cheap substrate. Overproducing strains of some bacteria have been developed, for example, Serratia marcescens, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas mutabilis, Bacillus sphaericus, Agrobacterium/Rhizobium HK94 and Sphingomonas sp., with the first three species being the best producers. Although the biotin yields achieved have already been close to the required level in some cases, none of the strains have yet produced enough biotin to allow profitable production(Reference Ledesma-Amaro, Jiménez, Revuelta, McNeil, Archer, Giavasis and Harvey225–Reference Wang, Liu, Jin and Zhang227,Reference Streit and Entcheva412,Reference Manandhar and Cronan427,Reference Outten447,Reference Laudert, Hohmann and Moo-Young508,Reference Survase, Bajaj and Singhal535–Reference Brown and Kamogawa553) . In 2022, a Danish biotech company, Biosyntia, announced the intention to commercialise the first biotin produced by sustainable fermentation using genetically modified microorganisms. Biosyntia will, jointly with a German company, Wacker Group, develop a large-scale industrial bioprocess based on its proprietary technology(554). The upcoming years will show whether the fermentative process is sufficiently efficient to be economically competitive with the currently used chemical process for biotin manufacturing.

Food fortification and biofortification with biotin

Regarding food fortification with biotin, the need is low because dietary biotin deficiency is rare(395,Reference Outten447,Reference McDowell458,460) . Biotin may be added to foods voluntarily by food manufacturers, for example, to processed cereal-based foods for infants and young children, milk powders, rice powders and breakfast cereals(214,258,259,395,Reference Laudert, Hohmann and Moo-Young508,Reference Fujimoto, Inaoki, Fukui, Inoue and Kuhara518,Reference Lu, Ren, Huang, Liao, Cai and Tie555) . The biotin content of infant and follow-on formula, and of processed cereal-based foods and baby foods for infants and children is regulated(214,259) . As for the biofortification of crops with biotin, no attempt has been reported.

Pharmacokinetics of biotin

Absorption

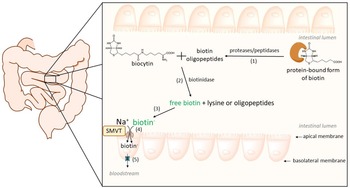

Biotin is present in its free and protein-bound forms in foodstuffs. After being ingested, protein-bound forms of biotin are cleaved by gastrointestinal proteases and peptidases, giving rise to biocytin and biotin-oligopeptides(Reference Wolf, Heard, McVoy and Raetz556,Reference Said557) . After that, biocytin and biotin-oligopeptides are hydrolysed by the enzyme biotinidase to release free biotin in the intestinal lumen. This enzyme is present in pancreatic juice, secretions of intestinal glands, bacterial microflora and the brush-border membranes(Reference Said, Thuy, Sweetman and Schatzman558). The last hydrolytic step is considered to be crucial and influences the bioavailability of biotin (Fig. 3)(Reference Wolf, Heard, McVoy and Raetz556,Reference Said, Thuy, Sweetman and Schatzman558) .

Fig. 3. Human intestinal absorption of dietary biotin. Firstly, protein-bound forms of biotin are cleaved by gastrointestinal proteases/peptidases (1); then, biocytin and biotin–oligopeptides are hydrolysed by biotinidase (2) to release free biotin (3). Biotin enters enterocytes at the apical membrane through a saturable and Na+−dependent carrier-mediated process (4) by the sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter (SMVT). The identity of the basolateral transporter is not yet known (5, shown in blue).