On 30 May 1933, Salt Lake City’s German American community gathered together to dedicate an unusual memorial. Erected in the back corner of nearby Fort Douglas’s cemetery, the memorial depicted a naked man hunched over himself and staring abjectly at the ground, and it honored not community members who had fought for the United States during World War I fifteen years earlier, but rather the German prisoners of war who had died while interned at the army base during the war years.Footnote 1 A gesture of reconciliation and grief, the memorial had received general approval not only from the national German American community, but also from American government officials, ranging from the mayor of Salt Lake City to the Secretary of War in Washington. Yet the memorial hid a much larger and darker story.

Only one of the twenty-one dead listed on the memorial had been a German prisoner of war. Most of the rest on the list were interned German Americans, rounded up by American government officials in 1917 and 1918 and held in Fort Douglas as “enemy aliens” until the war had ended.Footnote 2 And others, like Frank Beneš, had not been German at all.

Born in 1894, Beneš had come to America from the eastern side of Austria–Hungary as part of the major wave of Eastern European immigration to the United States at the turn of the century. He had worked diligently to make his way in his new homeland. When America declared war on Germany in 1917, he was drafted and began work as a miner in the US Mining Corps in Vancouver Barracks, Washington.Footnote 3 He displayed an unusual ability to leave warm and lasting impressions on others, striking one man who met him as “plain but sensible,” someone who held “the welfare of his countrymen especially at heart” and spoke out unhesitatingly and assuredly against injustice whenever and as soon as he saw it.Footnote 4 With a strong grasp of English, he often advocated for fellow Austro-Hungarians by acting as their interpreter.Footnote 5 But despite his visible commitment to his new country and its laws, the end of 1917 brought a devastating turn of events for his future in America.

In December, months after Beneš had entered the armed forces, the United States declared war on Austria–Hungary. Although the Austro-Hungarians had largely not been engaged on the Western Front, where American forces were headed, in March 1918, Beneš and the other Austro-Hungarians at Vancouver Barracks were visited by officials from the Department of Justice. During interrogation, they were asked whether they would be willing to take up arms against their homeland.Footnote 6 Citing fathers, brothers, and other relatives in the service of the Austro-Hungarian Army, nineteen men, including Beneš, refused. For their act of defiance, Beneš and his fellow Austro-Hungarians found themselves jailed in early 1918 before being shipped to Fort Douglas outside Salt Lake City in May, where they were to spend the rest of the war as interned “enemy aliens.” They were not formally discharged from the army, nor did they receive payment for their time in the service.Footnote 7 Beneš arrived at Fort Douglas in the spring of 1918, and the influenza pandemic arrived a few months later. Five days before the war ended, he died of pneumonia. He was twenty-four years old.Footnote 8

How and why the German American community of Salt Lake City came to disguise this history in their memorial is part of the larger story of American immigrants from the four empires destroyed by World War I: the Prussian, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman empires. These immigrants, often recent arrivals and closely tied to the homelands they had left behind, understood the stakes of the war in a way that many of their native-born fellow Americans could not. Many had relatives in their countries of origin and had followed the war closely through letters from their friends and families back home or through foreign-language newspapers. For some, the war brought independence to their homelands; for others, it brought crushing defeat. But for all of these communities, the war was a tale of two lands: the story of their homeland and the story of the United States.

Their memorials fell into the longer tradition of ethnic memorials in the United States, in that funds for many of them were raised, and many were dedicated, by members of individual ethnic communities, with little external input from the wider American community. Yet they represented a sharp departure from other nineteenth- and twentieth-century ethnic memorials because they were not inserted into American civic space to lay claim to belonging in the public sphere.Footnote 9 Generally speaking, as John Bodnar has noted, in the years after World War I, ethnic communities in the United States attempted “to replace vernacular interest in immigrant and local pioneers with expressions of loyalty to the nation-state.”Footnote 10 Not so with their war memorials. Reeling from the wave of nativism the war had engendered, communities hid away their memorials to the war and to those who had served in it in cemeteries or deep in ethnic neighborhoods. They had wanted their fellow Americans to see their memorials to ethnic heroes, to come to their parades, and to visit their historic settlements. But they did not want their fellow citizens to see their war memorials.

World-war memorials constructed by immigrant communities, therefore, unlike memorials constructed by native-born Americans, offer a new perspective on World War I and its significance to the many different groups of Americans who now composed the growing United States.Footnote 11 At first glance, these memorials affirmed loyalty to America and often honored those who had fought in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) – or, at least, in the case of Salt Lake City, those who had died as honorable enemies of the AEF. But by erecting these memorials in cemeteries and other removed locations, and by disguising the histories they honored, immigrant communities highlighted the costs the war had brought both to their countrymen in the United States and to those still abroad.Footnote 12 By contrast, the handful of native-born American attempts to include these nations in their own war memorials suggests just how little the two groups understood each other. In this way, these memorials reveal the war’s impact not only on American immigrants, but also on the countries from which those immigrants came. Their quiet presence in the nation’s graveyards and immigrant neighborhoods points to the shattering significance of World War I for a generation of new Americans.

German and Austro-Hungarian Americans during World War I

While many German and Austro-Hungarian Americans served in the AEF during the war, the dedication of the German War Memorial at Fort Douglas in 1933 would nevertheless have greatly surprised the German Americans of 1917. During the war years, statues associated with Germany, like many other symbols of German life in America, were targets for criticism and vandalism. In centers of German American life, like Milwaukee, Wisconsin and St. Paul, Minnesota, German American communities voluntarily took down statues of “Germania” (the sculptural embodiment of the modern German nation-state) and shrouded statues of German national figures like Goethe and Schiller to demonstrate their loyalty to a country that was censoring German-language newsletters, banning the instruction of German in schools, and interning their fellow immigrants on charges of disloyalty.Footnote 13

America’s internment camps began as POW camps for captured German soldiers and sailors, and were subsequently called to serve double duty by holding suspect “enemy aliens,” primarily from Germany and Austria–Hungary, arrested in the United States.Footnote 14 Conditions at the camps were tense, hostile, and occasionally deadly.Footnote 15 The Austro-Hungarians at Fort Douglas went so far as to appeal about camp conditions to the Swedish embassy, which as a neutral country had established a branch to advocate for the welfare of Austro-Hungarians in foreign countries during the war. Frank Beneš was elected one of the four men to speak to the delegate from the San Francisco office who visited to check on conditions at the camp, particularly on behalf of his fellow Hungarian soldiers from Vancouver Barracks.Footnote 16 Beneš and his fellow committee members relayed a litany of complaints, including stopped and censored mail, forced manual labor (a violation of the Hague Convention), and the “brutal treatment” that “practically all internees” had suffered in prisons before arriving at Fort Douglas.Footnote 17 “Most of the men have never been accused much less given a chance to defend themselves,” the delegate noted in his report.

To all appearances the most serious offense committed by many of those interned is that they were born in Austria–Hungary or Germany. Although apparently innocent of any wrong doing [sic] and with a clear record in the past, these men allege to have been treated like dangerous criminals and to have been brought in irons to the detention camp.Footnote 18

In all, twenty-one internees would die at Fort Douglas, the majority from influenza.Footnote 19 Most internees who survived were released from the camps in the spring of 1919. Many chose to stay in the United States, but others were deported to Germany and Austria–Hungary.Footnote 20 The legacy of the internees’ treatment would endure in the American justice system, which would implement a much larger internment system during World War II. It also endured in the memories of America’s immigrant communities, who had watched and learned that American citizenship and dedication to their new homeland would not be enough to keep them safe if the tide of American public opinion turned against their countries of origin.Footnote 21

Hiding in plain sight

In the war’s aftermath, anti-German sentiment faded rapidly. German communities benefited greatly from the 1921 Quota Act and the 1924 Immigration Act, which handed Germany a higher immigration quota than any other single country in Europe as part of an effort to block immigrants coming from Southern and Eastern Europe.Footnote 22 The failure of the United States to ratify the Treaty of Versailles or to join the League of Nations also began a wave of isolationist sentiment across the country, one which helped German Americans escape the public eye by turning the war into a fruitless endeavor that many felt had not been worth fighting in the first place. Growing antagonism towards other immigrant groups, in particular Italian Americans, and a souring relationship with France, also shielded German Americans from the worst of wartime prejudices.Footnote 23

For those immigrant communities who had ties to the fallen empires of Europe, however, commemoration was a complicated exercise. Some wished to honor the dual ties they felt between their homelands and their new home, but others feared that such a display might see them accused of dual loyalty, or, worse, that they might receive the same treatment that the German community had experienced during the war years. Early memorials often avoided making any reference to the lands from which new immigrants hailed, instead showing generically American soldiers and leaving the question of ethnic identity in the background. The northern Manhattan neighborhoods of Washington Heights and Inwood, for example, at the time 23 percent Jewish and 31 percent Roman Catholic, put up a memorial showing two soldiers aiding a wounded comrade, but while they listed the names of every man who had died from the community, they placed them on horizontal plaques, forcing the viewer to draw right next to the monument before they could notice how many names were of Irish, Italian, and Eastern European Jewish extraction.Footnote 24

When they did choose to highlight specific ethnic or national backgrounds, most of these Americans did so with a clear focus that could dissuade dual-loyalty charges, and their memorials came late to the commemorative landscape. Memorials to George Dilboy, the first Greek American to receive the Medal of Honor, went up in Somerville, Massachusetts (1931) and Hines, Illinois (1942), but they focussed on Dilboy alone rather than the wider Greek American community, and they were both dedicated more than a decade after the war had ended.Footnote 25 In Newark, New Jersey, the Lebanese American community planted cedars from Lebanon in downtown Newark’s Lincoln Park in 1939, honoring not the men from their own community who had served in the war but rather “the American soldiers who made the supreme sacrifice in the cause of liberty in the World War” (Figure 1).Footnote 26 By honoring American soldiers, New Jersey’s Lebanese community could make a claim to their place in American society, rather than focus on the turmoil that had engulfed Lebanon during the war or on the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. German American communities, meanwhile, showed an unsurprising reluctance to commemorate the war at all while wounds were still fresh. Some communities, like the heavily German town of New Ulm, Minnesota, would not put up their World War I memorial until the United States had entered the next war, when they found themselves called upon to reaffirm their loyalty to the United States all over again.Footnote 27

Figure 1. In 1939, the Lebanese community of New Jersey dedicated cedars of Lebanon to the city of Newark in the name of American soldiers who died in World War I, setting aside the destruction and chaos the war had wrought on their homeland to make a declaration of loyalty to their new country. Only one cedar has survived to the present. Two images side-by-side: a close up of a plaque dedicating Cedars of Lebanon to the city of Newark, and a photograph of a cedar tree in a park.

America’s Jewish population, drawn from all over Eastern Europe, found themselves caught in the middle, seeking to publicly announce their service on the one hand and to maintain their religious and ethnic identities on the other. The war had been utterly catastrophic for Eastern European Jewry, inspiring the creation of many Jewish aid organizations in the United States during the war that worked to help get Jews out of Europe. Jews who fought in American uniforms often had relatives who were desperately trying to escape their homelands.Footnote 28 Many of these Jewish refugees flooded into the United States in the war’s immediate aftermath, fleeing a new wave of pogroms sweeping Russia, despite new quotas instituted to prevent an influx of Jewish immigration.Footnote 29 Facing this tangled web of human suffering, Jewish American soldiers held firmly to multiple causes simultaneously. Committed to ensuring that their loyalty to the United States went unquestioned, they were also determined to hold onto their separate religious identity, and to promote the possible creation of a national Jewish state where Jews might live safe from the threat of constant violence they faced in Eastern Europe.

Thus, in 1927, when the majority-Jewish neighborhoods of Crown Heights and Brownsville in Brooklyn dedicated their war memorial, they opted for one engraved with the American eagle on the right and the Star of David on the left, a visual reminder of Jewish commitment to the American project, but situated deep within their own ethnic neighborhood.Footnote 30 Local officials proudly noted the memorial’s religious, ethnic, and racial diversity, emphasizing,

The design itself does not alone symbolize the guaranteed freedom of our nation for the very names that will be inscribed upon it stand for toleration. The name of Sullivan will follow the name of Solomon, a Jew, a Catholic and a Protestant are recorded in one panel, a Negro’s name is in juxtaposition to that of a white man.Footnote 31

The names, they argued, were the proof both of the success of America’s model of democracy and of the full Americanization of the men who had died fighting for democracy during the war. The memorial’s inscription echoed this claim that America belonged equally to all of these men, recognizing “those who at the call of their country, left all that was dear, endured hardship, faced danger, and finally passed out of sight … giving of their lives that others may live in freedom.”Footnote 32 But the monument’s visuals honored the role that Jewish Americans specifically played in helping create that version of the nation.

Jewish organizations also worked hard to ensure that Jewish war dead were acknowledged both as Americans and as Jews: rather than the crosses that marked most American graves, the Jewish Welfare Board pushed to make sure that Stars of David would mark the grave of any fallen Jewish soldier in all American military cemeteries.Footnote 33 “We do the work of our Jewish Community when we remind our men that they are Jews,” Chester Jacob Teller, president of the Jewish Welfare Board, argued in an address in 1918. “We do the work of the larger American community that America permits them to be Jews – nay, [that] we want them to be Jews for what they as Jews may contribute to the present culture-values of America in the making.”Footnote 34 Providing visual proof of Jewish service in every military cemetery was a simple and powerful reinforcement of both sides of Teller’s argument, reminding Jewish Americans of their religious identity while simultaneously reminding Americans that Jews had answered the call of their country like everyone else – but that they had done so not only as Americans, but as Jews. Even for those who did not opt for a military headstone and who chose to bring the bodies of their sons back for burial in the United States, there were private designs that could signal Jewish commitment both to the American state and to the broader Jewish diaspora. Many families, for example, opted for grave markers that showed the American flag crossed with the Zionist flag.

But nonmilitary grave markers, safe in their privately run cemeteries, sometimes said what the community could not say in public. The grave of Hyman Ambos, a sergeant with the 39th Infantry who was killed in France in 1918, bore two crossed American flags at the top of the marker to assert his patriotism, but it also referred to Ambos (in English) as a “victim” of the world war, denying the language of heroism that so often graced public memorials.Footnote 35 The family of Benjamin Reisen, killed in October of 1918, simply honored “our beloved brother” in their English inscription on his grave, but they used their Hebrew inscription to tie Reisen into the long legacy of Jewish history, describing him as killed al Kiddush HaShem (“for the Sanctity of God’s Name”), a phrase traditionally associated with Jewish martyrdom (Figure 2).Footnote 36 Many graves near Reisen described soldiers in English as having been “killed in France,” but Reisen’s and others described them in Hebrew as “killed on the battlefield,” a phrase that again situated World War I in the larger framework of Jewish history and global conflict.Footnote 37 Behind the gates of cemeteries, Jewish families were more able to speak openly about their understanding of this conflict as both an American and a Jewish struggle.

Figure 2. Benjamin Reisen, a Jewish private killed in France in October 1918, was honored on his gravestone in English only as “our beloved Brother.” In Hebrew, however, in addition to specifying the date of his death in the Jewish calendar and his Hebrew name, his family added that he was “killed for the Sanctity of God’s Name on the battlefield,” tying the private into a long lineage of Jewish martyrdom. Figure of a grave monument with two crossed flags at the top, the then-Zionist (now Israeli) flag and the American flag. A lengthy Hebrew inscription follows, with a short epitaph in English at the bottom: “In memory of our beloved Brother.”

Other immigrant groups found that cemeteries offered them the same measure of protection to send two messages at once. The Polish American community had seen some of its sons enlist not in the AEF but with the Haller Army, which fought for the liberation of Poland in the later years of the war. In Niles, Illinois, Chicago’s enormous Polish community honored this double sacrifice in 1928 with an obelisk that recognized those who had served in the army, the navy, the marines, and the Haller Army on four separate sides.Footnote 38 The names of the dead, divided by service branch, revealed an American community with strong ties to their homeland: sixty-eight men had served in the American Army, or about 60 percent of the total dead, and thirty-six had served in the Haller Army, or 31 percent. This ratio was much higher than the national average for the Polish population, which saw only 12 percent of all Polish soldiers serving with the Haller Army instead of the AEF.Footnote 39 The scant information about those who went to the Haller Army was apparent in the memorial, for although nearly all soldiers and sailors in the AEF were listed by rank and division, most soldiers in the Haller Army were acknowledged only by name. Nevertheless, the memorial made clear that all four sides were due equal honor, with the inscription dedicating the memorial simply to “the sacred memory of the soldiers and sailors of the World War.”Footnote 40

The memorial also offered a chance for the community to express their deep grievances against Germany in a private space. While the soldiers of the Haller Army and the American Army and Navy stood in various poses of rigid attention, the statue of the Marine held a more relaxed stance, and he carried two captured German helmets in his hand (Figure 3).Footnote 41 Such gestures, when made in the public sphere, had been condemned by the American public. A statue in Seattle depicting a soldier with two German helmets had drawn outcry that same year because it was felt to be offensive to the local German American community.Footnote 42 But behind the cemetery gates, Chicago’s Polish Americans were free to say what they felt, though with an extra layer of caution. The statue itself was placed relatively near the cemetery entrance, but the marine faced straight inward, where he could not be seen by passersby. The community made sure to dedicate the memorial on 4 July, a date that would be above scrutiny in the eyes of any outsiders.

Figure 3. Chicago’s Polish American World War I memorial honors both the soldiers who fought with the American Expeditionary Forces and in the Haller Army for the liberation of Poland. The fourth side, however, facing directly into the cemetery, shows a marine taking home the spoils of war from Germany. Photograph of a statue of a Marine from below. The Marine, dressed in a World War I uniform, is holding two German helmets.

While the dawn of Polish independence was a cause for celebration, for other immigrant communities these memorials served as the only remnant left from a vanished world, one to which they could never return. Such was the case for America’s Russian community, which on Memorial Day, 1928, dedicated a memorial to World War I veterans in the corner of Seattle’s Evergreen Washelli Cemetery.Footnote 43 In the new Soviet Union, there were no official state memorials to the world war, and the war’s history had been effectively transformed by the new regime into a justification for the overthrow of the tsar.Footnote 44 Russian Americans instead joined the émigré communities of Russians around the world who, removed from their homeland, could dedicate a moment of time and space to considering Russia’s terrible wartime losses. A tall pyramid, shaped like a pascha (the Russian cheese eaten at Easter), the monument held a tiny chapel where the dead could be mourned away from the eyes of outsiders (Figure 4). Completed in 1936, it let the English-speaking press know that every Memorial Day the community honored not only Russian but also American soldiers.Footnote 45

Figure 4. Set in the back of Seattle’s Evergreen Washelli Cemetery, surrounded by graves of the Russian Orthodox community, the lone Russian war memorial in the United States represented a world now lost, honoring soldiers of an empire that World War I had destroyed and that the new Soviet government refused to acknowledge. Photograph of a cemetery, foregrounded with individual graves. In the background stands a tall white pyramid with a Russian cross on top.

In each of these cases, memorials were dedicated quietly. They were advertised briefly in the public press but subsequently handled inside immigrant communities and behind cemetery gates, where none but members of that group would go. They reflected honest efforts to engage with a war that could not be reduced to a single event or meaning, and they often successfully represented multiple and conflicting feelings on a single monument, a testament both to creative artists and to immigrant communities’ engagement with both the commemorative world of the United States and the costs of the war in their countries of origin. But while they offered a space for reflection to their own communities, each group attempted to fly under the radar of the general American public.

“To honor our German brothers”

For some communities, even a cemetery did not always seem safe enough to escape public scrutiny. Such was particularly the case in Salt Lake City, where the German and Austro-Hungarian internees had been buried in a military cemetery, directly under the watch of the United States Army. The careful line the local German community walked in explaining what their memorial was and why they were building it revealed much of how little they felt they could say in public.

In the first week of November 1932, local Utah sculptor Arno Steinicke wrote the local German paper, Der Beobachter, to place an announcement. It ran on 10 November, the day before Armistice Day, and it called upon Salt Lake City’s German community to remember their own fallen.Footnote 46 A monument, Steinicke announced, would be erected in Fort Douglas’s cemetery and dedicated on Decoration Day (30 May) in 1933. It would be the first of its kind in the country. The memorial would be a gesture by German Americans to honor their German countrymen who had died in the United States.

One monument had already been dedicated to honor German prisoners of war, but not by German Americans. In 1932, the American Legion chapter in Asheville, North Carolina took it upon themselves to dedicate a small memorial honoring the German prisoners of war who had died from typhoid fever at a POW camp in neighboring Hot Springs. In an impressive ceremony, the Legion presented to the German ambassador a boulder in the local cemetery with the names of the dead engraved on the front accompanied by a quote from Goethe. “We are dedicating this memorial to your dead heroes,” Thomas B. Black, former commander of the local Legion chapter, said in an address to the ambassador. “We are dedicating it to their patriotism. We are dedicating it to the cause of peace and goodwill among men, and to the cause of everlasting peace between you and us.”Footnote 47

Such a gesture came at a time when the Legion, still reeling from the summer’s Bonus March and fighting to preserve the status of World War I veterans in the American political landscape, had extended multiple gestures of charity towards their German counterparts.Footnote 48 But Steinicke saw Salt Lake City’s memorial as a chance to offer a properly German response to the American Legion’s acknowledgment, one that would recenter focus on the German American community instead of the Legion’s visions of charity. Unlike North Carolina’s memorial, which had been funded by the Legion itself, this one would be funded primarily (though not exclusively) by the German American community.Footnote 49 To Steinicke, as with individuals in so many other communities, it was a matter of pride that Germans show they could provide for their own dead. The memorial would also provide a space for his countrymen to process the cataclysmic event that had just struck their old homeland. “Landsmen!” he appealed. “With the erection of this monument we will not only honor our dead, but our old Fatherland. It is a point of honor that has not been settled!”Footnote 50

Steinicke likely felt that Ehrensache (point of honor) personally, for he had been a soldier in the Great War himself – in the German Army. As his time in the war had been primarily on the Eastern Front, with a brief stint in a Russian POW camp, he had not fought against the Americans and bore them no particular animosity. Instead, he had made his way to the United States after the war, where he had converted in 1928 to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and settled in Utah.Footnote 51 Steinicke likely knew that building a monument to commemorate his own military service was perhaps a bridge too far, even in the current climate. But the dead at Fort Douglas were a different matter. Their graves were unmarked; their story, in Steinicke’s eyes, was uncomplicated. Here was a chance for his adopted country to show off its tolerance and magnanimity, and for his community to honor their own.

The German American community responded with alacrity. Although not all funds for the memorial were raised by the time of its dedication, money had come in from fifty-two German organizations in fourteen states, representing most of the major German communities in the United States.Footnote 52 Other endorsements had poured in from the local community, including the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce, the Salt Lake City Board of Commissioners, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and C. Clarence Nelsen (former mayor of the city).Footnote 53 A commendation even came in from the War Department, although it was couched in careful language: “Though living as peaceful and respected members of their communities prior to the entrance of the United States in armed conflict with their Fatherland, it was felt necessary for the safety of our people to segregate and confine them in internment camps for the duration of the war,” wrote George H. Dern, Roosevelt’s brand-new Secretary of War (and, from 1925 until March 1933, the governor of Utah), at once acknowledging that internees had been integrated members of their communities before the war and yet still setting them apart. “It is indeed fitting that their graves should be identified as those of honored American citizens which they would have been had they lived,” he added awkwardly.Footnote 54

Commendations poured in from the German community, too. The German ambassador wrote to express his regrets that he could not attend and convey his appreciation at being named an honorary member of the Monument Commission. And Franz Seldte, the Bundesführer of Germany’s infantry veterans’ organization, the Steel Helmets, wrote to express his admiration and send the members of the New York branch of the Steel Helmets to attend the ceremony. “The Steel Helmets hope that gradually a good agreement between the two great nations will be enabled for the benefit of the whole international populace,” Seldte wrote, three weeks before he accepted his new position as minister of labor for the Third Reich on 30 January 1933.Footnote 55 By the time his letter was reprinted in Der Beobachter’s commemorative issue, the Steel Helmets had been subordinate to Adolf Hitler’s administration for a month.Footnote 56

Trained as a sculptor before the war, Steinicke was not interested in simply dedicating an engraved stone. Instead, the memorial he created was an accusation: an emaciated, naked man hunched over himself, his eyes downcast, shrinking away from the viewer (Figure 5).Footnote 57 Ten feet high, it stood out in Fort Douglas’s largely unadorned military cemetery, and yet the flinching figure on top was the exact opposite of most American statues of World War I soldiers erected throughout the United States. Folded in on itself instead of charging up into the air, turning away instead of looking forward, and clutching his arm as if to shield himself from further blows, he represented a helpless victim, subject to a decision that he could not understand and could not protest. Situated in the back corner of the cemetery, his presence damned the cruelty of Americans during World War I, but from a safe distance.

Figure 5. Arno Steinicke’s memorial to the internees of Fort Douglas showed the victims of the world war rather than its heroes, but the memorial’s inscription disguised the victims’ real identities. Photograph of a stone monument with a plaque and the German state seal on the front, with a statue of a naked man crouched on top. His face is turned away from the viewer and the front of the monument.

Although the fund-raising operations had been run primarily in German, the monument’s inscription was in English, for all to see. But the language of the inscription left much unsaid. Articles in Der Beobachter had made it clear that the local community knew perfectly well that it had not just been prisoners of war interned at Fort Douglas. In fact, it was their own countrymen, German Americans and German immigrants, that made up seventeen of the twenty-one dead listed on the monument. Der Beobachter regularly referred to both deutsche Kriegsgefangenen (German prisoners of war) and interniere deutsche Staatsangehörigen (interned German citizens), drawing a clear distinction between the two groups.Footnote 58 Yet the issue of internment was left out of the memorial. Honoring enemy fighters, captured honestly on the battlefield, was one matter. But calling attention to the American decision to arrest and hold without probable cause many German immigrants as “enemy aliens” would perhaps go too far. Steinecke and his committee thus erased this history, declaring all dead “German prisoners of war,” although in fact only one man on the list of dead had actually been a POW at all.Footnote 59

And of course, not all the dead were German either. Besides Frank Beneš, there were two other Austro-Hungarians named on the monument: Joseph Fuckald (misprinted as Fuckola on the memorial), a candy maker who had been arrested in Kansas City, and Roko Zilko, a fisherman from Los Angeles, both of whom died of pneumonia in the weeks after the war ended.Footnote 60 Did anyone know that they had not been German? It was hard to say. Even Frank Beneš’s death certificate marked him as a German national.Footnote 61 Yet many of his fellow Austrians, Hungarians, Czechs, and the rest had survived their time in the internment camp. Did they ever learn of the monument? Would they have said anything, if they did? It is impossible to know, but it seems unlikely. To begin with, coverage of Salt Lake’s memorial was muted outside the German-language press. But far more importantly, these men had already seen what happened when one was associated with the German community in the United States. No good could have come from drawing attention to themselves now. And so Frank Beneš, Joseph Fuckald, and Rolo Zilko, with no family or friends to speak for them, became German nationals in death, for that was the only way that anyone might remember them at all.Footnote 62

“Non oblita est”

Salt Lake City’s memorial had been approved by the government in Utah and in Washington in part because of what it did not say. No one had called the government out directly on the horrors of internment, a silence that would bring grave consequences for a new generation of internees during World War II. By and large, Americans remained largely ignorant of the double stories many immigrant communities were erecting in their graveyards. They did not see them, and they did not read the foreign-language newspapers where these conversations could be carried out more freely. Instead, they embraced a more forgiving attitude towards those who had been swept into what they framed as a meaningless conflict. In their reframing of the war, however, native-born Americans further detached their understanding of the war from immigrant interpretations. Nowhere was this divide more apparent than at Harvard University, where, in 1932, officials dedicated a memorial tablet in their newly built Memorial Church to four German students who had attended Harvard before the war broke out, and who had fallen while fighting for Germany.

Such a gesture was really only possible at Harvard. The question never arose at most of Harvard’s peer institutions on the East Coast, most of whom dedicated their memorials in the immediate aftermath of the war when emotions were still too high.Footnote 63 Even at Johns Hopkins, whose own curriculum had been so shaped by German universities, there was never any recorded discussion of honoring German students.Footnote 64 At the University of Wisconsin–Madison, which was home to a large German immigrant population that had been rocked by vitriolic anti-German sentiment during the war, students and faculty dedicated their commemorative funds to a Memorial Union building that could house the student union.Footnote 65 In its center, staff included the Rathskeller, a room modeled on a German beer hall, in a nod to the state’s German history, but that past was understood to be an entirely mythical one. In its successful effort to extend commemorative recognition beyond America and her allies, Harvard stood alone.

As in many places, the road to Harvard’s war memorial had been long and beset with controversies. The school had proposed early on to build a church, one that could replace the current too-small Appleton Chapel.Footnote 66 The decision was decried on all sides, both by alumni and by current students. Some felt that Harvard had showed how little living memorials such as buildings could do when it built Memorial Hall in honor of students who had died in the Civil War a generation earlier. No one paid attention to it now, after all, or even knew it was a memorial, grumbled three displeased alumni.Footnote 67 Others felt that Harvard had a perfectly good church already, and that tearing it down to build a larger one would simply show the community’s dwindling religious observance, for surely it would only be full on Sundays.Footnote 68

But the most serious complaint came from Harvard’s religious minorities, who felt that the decision to build a memorial church reflected Harvard’s deep nativism and anti-Semitism. What use would Catholic students have for a Protestant church? And what use would Jewish and agnostic students have for a church at all?Footnote 69 This was not an empty question: among Harvard’s 386 dead, the highest percentage of dead for any university in the country, were approximately ninety Catholics, twenty Jews, and ten other religious minorities. “It is preposterous to believe that Jews, Agnostics, Christian Scientists, etc. can have any honest sympathy in a Protestant Memorial,” argued the student newspaper, the Crimson, noting additionally that Roman Catholics could not worship in non-dedicated churches.Footnote 70 Harvard undergraduates themselves came out strongly against the church, collecting signatures for a petition protesting the chapel and dedicating an issue of the Crimson to detailing exactly how many students would not be sufficiently honored by such a memorial.Footnote 71

Many alumni claimed not to see what the problem was, a response that revealed the depth of Harvard’s virulent anti-Semitism problem. Surely, one alum noted, “any broad-minded Jew” would not find the church objectionable, so long as he was a “high-minded Hebrew.”Footnote 72 The idea of a church was really non-religious, argued others, because it was only meant to provide a space of contemplation. But in any case, the donations had been made and Harvard Corporation officials felt it impossible to renege on their commitment, a decision which Harvard president Lawrence A. Lowell communicated quite clearly to all petitioners who came before him.Footnote 73 And so, in March 1931, the protests against the chapel began to take a different form.

“While, in the light of the facts, any determined opposition to the Chapel, its location, or size vanished, one feature of the proposed Memorial met with keen regret,” began a March letter from the Harvard Student Council to Lowell. “This was the omission of any mention of the Harvard Dead of the Central Powers.”Footnote 74 Four German graduates of Harvard had died fighting for Germany against the Allied Powers. Students now began to argue that perhaps these alumni, as Harvard men first and Germans second, ought to be commemorated in the church as well. The Crimson joined them, arguing that “to exclude [German dead] would be an insult upon men who died in pursuit of their duty as they conceived it.”Footnote 75 These men had followed the morals that Harvard had taught them, students argued. When asked, they had laid down their lives for their country. Should not that loyalty and sense of duty be honored?

In fact, argued the Methodist Wesley Foundation, it would be positively unchristian not to list the German students. “The proposed restriction is narrow-minded and unchristian, for the Memorial is taking the form of a chapel, a religious edifice, built for the worship of God, symbolic of love and truth, of the Fatherhood of God, and of the Brotherhood of man, irrespective of country, race, or creed,” the students argued in a resolution sent to Lowell. “[B]oth as a Memorial to Harvard men and as a Chapel for the worship of God, the building fails in spirit.”Footnote 76

It was an interesting turn – and one that Lowell and others could be forgiven for suspecting had more to do with the anti-chapel angle than with the Germans themselves. “The students believe that if the proposed new chapel is to be built at all, it should be in honor of all Harvard Alumni who fought in the World War, regardless of which side they took,” the Wesley Foundation’s letter began.Footnote 77 Lowell and the Harvard Corporation contended that the terms of the donation for the church had excluded honoring enemy dead, and that was where the issue should lie.Footnote 78 But Lowell also took pains to emphasize the flaws, as he saw it, in the students’ pivot: “That the memorial in this case is a chapel is immaterial,” he wrote one dissenting student group. “If the list is right for any memorial it is right for a chapel. If not fit for a chapel because unchristian it is bad for any purpose.”Footnote 79 If it had been the intention of the students to halt the chapel’s construction over these concerns, their “unchristian” argument worked perhaps too well: far from stalling any plans, Lowell was soon receiving letters from Christian religious leaders and Harvard alumni arguing in favor of the Christian principles that had inspired students to include their German peers, and, by extension, in favor of the chapel.Footnote 80 But in the cacophony, the questions of anti-Semitism, nativism, and accessibility for all non-Christian students at Harvard melted away.

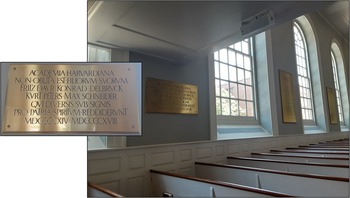

Throughout the spring, President Lowell received threats both to withdraw donations if Harvard went ahead with any plan to honor the German students and to withdraw donations if they didn’t.Footnote 81 Publicly, Lowell maintained the stance that the Harvard Corporation funds had been collected to honor only Allied students. But privately, Lowell surveyed members of the War Memorial Fund for their opinions on a third possibility: that while the church would name only the Allied students on its walls, a separate plaque might be added somewhere within the church to acknowledge the German students. The donors, while warning that they could not speak for the commission as a whole, agreed. “It seems to us wholly appropriate,” they offered, “that the University … should say in their Chapel … We remember too, those other sons of Harvard, who once lived and studied here side by side with you and were your friends, whose lives were also sacrificed in that war wherein you played so noble a part.”Footnote 82 Lowell had privately even begun work on a possible inscription for the memorial. Notably, while the dedicatory language of the chapel was to be in English, the plaque honoring German students was written only in Latin, a language that most Harvard students would have been able to read, but which (reflecting the controversy the memorial had engendered) might not have been immediately apparent to the wider community passing through the church:

ACADEMIA HARVARDIANA

NON OBLITA EST FILIORUM SUORUM

FRITZ DAUR · KONRAD DELBRUCK

KURT PETERS · MAX SCHNEIDER

QUID DIVERSIS SUB SIGNIS

PRO PATRIA SPIRITUM REDIDERUNT

MDCCCCXIV - MDCCCCXVIIIFootnote 83

The public would not learn of this decision until after the main chapel had been unveiled on Armistice Day, 1932.Footnote 84 But the dedication of the plaque appeared in the papers one month later in December 1932. Moreover, the plaque was placed at eye level, where it might be seen by all those who sat in the pews on any given Sunday (Figure 6).Footnote 85 This, of course, meant that Harvard’s Jewish or Catholic students were no more likely to see it than they were to use the church on a weekly basis, but that was never the point. Perhaps the request to include German students had been made too soon in the eyes of many Americans, admitted the Nashville Tennessean. Yet over the two years that the debate had raged, opinions had softened. The courage of young men to fight for their homeland, the paper argued, was what made war memorials powerful no matter where the young men were from. “The Harvard memorial,” they concluded, “now becomes a symbol of growing understanding.”Footnote 86

Figure 6. Though the plaque was written in Latin and thus not easily readable by every outsider who entered, Harvard placed its memorial plaque to its German students directly above the pews in the sanctuary of Memorial Church, where students might see and reflect upon it every time they attended services. Two photographs placed one on top of the other. The close-up shows a gold plaque with Latin writing on it. The wider shot shows the plaque’s location in Harvard Memorial Church, hanging above the pews.

But Harvard’s gesture, made from a genuine spirit of international fellowship, revealed the depth of its ignorance about what this war had meant to immigrant communities in America, and even more about what it had meant in Europe. It is striking that the only letter Lowell received about the plaque from an actual German suggested that the gesture, while demonstrative of the “noble spirit” of Americans, was unnecessary. The author, Walter Bonsack, a noted metallurgist born in Berlin but currently residing in Cleveland, suggested that if Harvard wished to create “a warmer feeling toward America and her people,” they might instead dedicate a plaque to the three German students at a university in Germany, where Germans themselves might see it.Footnote 87 But the German people had never really been at the center of Harvard’s debate, and the suggestion went nowhere.Footnote 88

In the following years the Harvard chapel became an unwitting prop in the German effort to normalize the new Nazi regime in America. The willingness of German schoolboys to die for their country in World War I had become a central cornerstone of Nazi mythology about the war thanks to a legend about the Battle of Langemarck in fall 1914, during which, it was claimed, students had rushed into battle singing “Deutschland über alles.”Footnote 89 On Germany’s Memorial Day in March 1935, members of the German consulate in Boston visited Harvard, and laid a wreath with a swastika at its center at the base of the memorial plaque. With both prominent Harvard faculty members and visiting professors from Nazi Germany in attendance, the gesture was understood – and decried – as an endorsement of both the regime and its policies, and in particular as a deadly insult to Harvard’s Jewish students and faculty.Footnote 90 The German War Memorial had been offered as a gesture of goodwill and international friendship, but it had never really understood the immigrant American perspectives on the fallout of World War I. As such, it was read by the Germans themselves, as well as by Jews and other groups under threat from the Nazi regime, as a welcome sign for current German policies. Harvard’s gestures, now couched firmly in the language of Christian goodwill, did nothing to assuage this impression.

Shifting meanings, shifting places

At the start of 1934, Cornell University announced a new plan for a memorial to Cornell’s own German student, Hans Wagner, of the class of 1912, who also had fought and died for Germany. Money in the Hans Wagner Memorial Fund would be donated, reported the Cornell Daily Sun, to fund lectureships at the university for scholars who had fled Nazi Germany and were rebuilding their lives in the United States.Footnote 91 “Since the aftereffects of the World War and the unfairness of the Versailles Treaty were directly responsible for the ruthless, nationalistic spirit in present-day Germany,” the Sun concluded, “it is entirely appropriate that the Hans Wagner Memorial Fund originally intended to be used as a demonstration of international goodwill, should be used to aid those who have borne the brunt of the consequences.”Footnote 92

By and large, the rise of Nazi Germany put an end to American efforts to honor Germany’s fallen. For immigrant Americans themselves, however, the gestures made at Harvard and elsewhere had done little to nothing to suggest that their voices were welcome in the public sphere, and they watched the growing shadow in Germany with deep concern. On 22 September 1935, the Sunday before Rosh Hashana and the start of the Jewish year 5696, a small memorial was dedicated in Portland, Maine. Neither the first nor the most prominent world-war memorial in the city, it was dedicated by the Jewish War Veterans of the state, and it honored a single man, Jacob Cousins, the first Maine Jew to die in the war. A boulder with an engraving of Cousins’s face, it was modest but well placed on the upper level of Portland’s Eastern Promenade overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, in a park originally designed by Frederick Law Olmstead. The Promenade was already home to several Civil War memorials, including a bench and two cannons, ensuring that this new memorial would be understood as part of a larger civic commemorative project.Footnote 93 This signaled a clear departure from previous commemorative efforts by the Jewish community: here was a memorial that they wanted the general public to see.

Reports on the dedication were limited to the local Portland papers and the Boston Jewish Advocate. But their language was stern, straightforward, and urgent. “Jacob Cousins left a torch for us to carry,” extolled the event’s main speaker, Jean Mathis, a Jewish New Yorker who had earned the Croix de Guerre, the Distinguished Service Cross, and the Silver Cross for his wartime service. “Jacob Cousins gave his life to make the world safe for democracy, and today we want no Naziism, no Fascism, no Communism.”Footnote 94 Other speakers echoed this plea, reminding the assembled that Jews and Christians were equal in the eyes of God, and that it had taken the shared blood of both to sustain democracy in the world war.Footnote 95 They had clear grounds for their urgency. The Nuremberg Laws had been passed by the Nazi Party in Germany on 15 September, exactly one week earlier.

But for other communities, shifting winds in Europe were reason only to conceal themselves further. Fort Douglas reopened its gates less than a decade after the dedication of the German War Memorial, this time interning German and Italian Americans.Footnote 96 It was probably a very rare camp official who paused amidst the bustle of wartime activity to consider Steinicke’s German War Memorial, and an even rarer one who remembered the history it represented. Across the country, a new generation of immigrant Americans, now from a far wider population, were rounded up into new internment camps. Subsumed by a new war and new losses, most immigrant communities must have thought that hiding their memorials away from the public had been the safest plan after all.

Eliana Chavkin (she/her) is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at Brown University’s Pembroke Center, where she studies trends in American commemorative practices. Her book project focusses on the myriad ways in which Americans commemorated World War I. She holds a PhD (2025) and an MA (2023) from the University of Minnesota and a BA from Bryn Mawr College (2016). Her research interests include memory studies, World War I studies, twentieth- and twenty-first-century American history, and commemorative practices worldwide. She can be reached at eliana_chavkin@brown.edu.