INTRODUCTION

In the early decades of the sixteenth century, on the eve of Saint John’s Day, the miners of the Tretto upland, a mining area nestled at the foothill of the Alps near the city of Vicenza, witnessed the blossoming of silver veins. At midnight, they gazed at the hilly landscape and saw turquoise flames rising from the cracks of the earth, illuminating the night sky with curved, arch-like lines. This event was accompanied by strident noises that frightened the miners, some of whom claimed to have seen dark, human-shaped figures emerging from the subsoil. Those who braved their fear gained insights into the nature of silver veins. By observing how veins interacted with the landscape, miners inferred their properties, foresaw their economic potential, and predicted their cyclical life.Footnote 1

Saint John’s Eve and Saint John’s Day, known together as Midsummer, herald the beginning of the summer season. In early modern Europe, rural communities celebrated this day with bonfires and harvest festivals imbued with ritualistic and folkloric significance revolving around the passage of time and the changing of seasons.Footnote 2 Blurring the boundaries between the subterranean world and the realm of the living, this time of transition had implications in the miners’ knowledge and belief systems. In Central European mining communities, it was believed that trees, branches, and hazelwood collected on this night possessed dowsing powers that would guide miners to potential excavation sites.Footnote 3 In Tretto, Saint John’s Eve was the one night of the year when miners believed it was possible to find alchemical plants capable of transmuting metals into gold. While sightings of flashing lights occurred irregularly throughout the year and did not evolve into annual mining festivities, they did serve as material manifestations of the porous boundaries between the underground and the surface world, and as evidence of the relationship between humans and minerals.

The significance of Saint John’s Eve extended beyond mining and reflected the organic and vitalist theories that typically shaped human-nature interactions in the early modern period. The ripening of veins and their passage into the human realm was part of the cultural and scientific framework through which early modern people conceived and engaged with mineral resources. Describing the moment when veins matured after a long period of gestation in the subsoil, early modern texts on mining and metallurgy framed the generation of minerals through organic analogies with the plant world.Footnote 4 According to these analogies, mineral resources were not static elements separated from the human domain and awaiting extraction by the masterful hands of miners. Their production—that is, the labor put into excavating ores and refining them into metals—depended on and was entangled with the generative powers of nature.Footnote 5

Similar views influenced interactions between humans and nature in the Venetian lagoon and its surrounding territories. Drawing on the concept of Republican nature, recent studies have shown that Venetian magistracies implemented successful preservation policies aimed at key economic resources for the lagoon’s survival—notably water and timber. Karl Appuhn has insightfully argued that Venetian officials’ conceptualization of forest landscapes was shaped by what he terms managerial organicism—a sophisticated combination of a “vitalist conception of nature with a state-directed effort at forest preservation.”Footnote 6 Venetian ruling elites recognized the economic value of resources as products of nature, while also acknowledging the interdependence between human actions and the natural world as crucial for forest preservation. In other words, magistrates’ policies sought to preserve nature for the collective good.

These views of human-nature interactions proved particularly successful because they leveraged “more inclusive forms of experience and knowledge-sharing” between elite magistrates and workers on the ground.Footnote 7 For example, when drafting new fishery regulations for the Venetian lagoon, the water officers (Savi alle Acque) of the Republic of Venice consulted with fishing communities to understand the impact of diverting the Brenta river (1604–13) on the lagoon’s condition. While some of the fishermen’s suggestions, collected in interviews conducted in 1623, were incorporated into new regulations over the course of the seventeenth century, not all workers’ opinions made it past the officials’ filters. At times, “the interviewees expressed natural, theological or fatalistic views about the lagoon” that differed from the technical expertise of the water officials.Footnote 8 Historians argue that navigating these diverse opinions “had the advantage of ensuring the participation of different interest groups” and distributed political power in Venetian society’s highly hierarchical structure.Footnote 9 However, worker perspectives on human-nature interactions, which could offer “an alternative framework for landscape, where reality and its potential for imagining and representation intersected,” were often lost in the process.Footnote 10

How do we account for these rejected views? And what can they tell us about human-nature relationship in early modern Europe? The answers to these questions reveal bottom-up concepts of and interactions with mineral resources. This article brings attention to these overlooked perspectives by defining mines as resource landscapes, despite the absence of this expression in the vocabulary of period actors. Miners in Tretto used two key terms to define resources in connection with the landscape. The term blossom (fiorire) captures the concept of mineral resources undergoing generation, decay, and renewal throughout the Tretto upland. Miners saw veins reaching maturity, leading them to conceptualize mineral resources as living beings with life cycles similar to plants, animals, and humans.Footnote 11 In a more practical sense, the term prophecy (profezia) refers to the mining landscape as a space for economic foresight. By observing veins transitioning from the underground realm to the surface, miners grappled with the cyclical nature of minerals and developed methods to predict the future of mining activities.Footnote 12 Bringing these vernacular meanings to the forefront of human-nature interactions defines mines as spaces of both concrete and imaginary actions. In other words, it sheds light on how humans’ interactions with minerals situated laboring bodies, belief systems, and materials at the intersection of landscapes and resources.

Bottom-up views of the uncertainties and futurities of mineral resources are vividly illustrated in the chronicle Notizie del Tretto (News from Tretto), written by the local clerk Iseppo Gorlin from Schio (d. ca. 1614). Gorlin penned the chronicle sometime between 1586 and 1614, during his tenure drafting public and private legal documents in the town of Schio and the community of Tretto. He documented events from a hundred years before, including the discovery of mineral resources in the Tretto upland by a German friar named Fra Bernat, a mountain magus and necromancer who roamed across the Tretto around the 1490s. From the fifteenth to the seventeenth century, the term magus referred to practitioners of a new domain of knowledge—known as natural magic—that sought to investigate the secrets of nature by using principles of natural philosophy and the ancient art of magic. Walking a fine line with respect to heresy, these practitioners ranged from alchemists, and astrologers to priests and necromancers—the latter often associated with treasure hunting and rural beliefs about the abundance of the fields. Magi employed various learned and practical methods, including natural philosophy practices and divinatory powers, “to draw on and enhance the secret forces of nature.”Footnote 13

To reconstruct Fra Bernat’s discoveries, Gorlin primarily relied on miners’ testimonies. He claimed to have interviewed elderly miners who worked alongside Fra Bernat, yet given the century-long gap, it is unlikely that any direct witnesses were still alive. Rather, these accounts point to a living tradition of oral history surrounding local mineral resources, passed down from generation to generation in Tretto. For this reason, I argue that Fra Bernat’s activities, as outlined in the chronicle, offer insights into the perspectives of local miners regarding mineral resources and mining landscapes. Despite the chronological gap between the events and Gorlin’s writing, the chronicle enjoyed a long afterlife, underscoring the lasting significance of miners’ accounts of mineral discoveries in the Venetian mainland. While the original manuscript has not survived, five copies are known to exist: three date from the seventeenth century, one from the eighteenth century, and one from the nineteenth century.Footnote 14 The chronicle’s enduring appeal lies in its detailed descriptions of the discovery of mineral resources and its precise representation of geomorphological landscapes—hills, rivers, fields, mountains, and also towns, churches, and toponyms—that later attracted the attention of geologists like Pietro Maraschini (1774–1825).Footnote 15

Reconstructing miners’ perspectives through texts authored by individuals of different social ranks poses certain challenges. In her study of the visibility of fossil finders in eighteenth-century Europe, Lydia Barnet has demonstrated that the complex social hierarchies in mines and quarries influenced how naturalists chose to portray the contributions of earth workers. Their depictions focused on the physical labor of workers rather than workers’ views on nature and its materials.Footnote 16 The clerk Iseppo Gorlin authored his chronicle from a similar position. Gorlin aims to present silver mining to local and distant investors as a stable and predictable activity, as it was in the early years of the sixteenth century. Although he relies on miners as the witnesses to the opportunities generated by silver extraction in Tretto, Gorlin often portrays their contribution to this prosperous past in ambiguous terms, especially since he describes them as doubting Fra Bernat’s methods and guidance. By diminishing the role of the miners, Gorlin positions himself as a credible mediator between the miners’ vernacular practices and new investors. He substantiated miners’ testimonies by collecting notarial deeds of enriched miners and by consulting written memoirs left by German experts who had migrated to the Tretto in the early sixteenth century.Footnote 17 Unpacking the layers that construct Gorlin’s credibility reveals that concerns about time, uncertainty, and the predictability of minerals were shared not only by elite authors and investors but also by miners, highlighting how chronicles like Gorlin’s capture bottom-up vernacular frameworks of underground resources.

I will use an unedited seventeenth-century copy of the chronicle housed in the Processi subsection of the collection Deputati alle Miniere (Mining deputies) in the Venice State Archive. By comparing it with later copies, the text—though partially incomplete—reveals original materials, suggesting that it may be the earliest copy ever made of the chronicle.Footnote 18 After first investigating Gorlin’s intentions in writing the chronicle, as well as the miners’ testimonies that he included, I will delve into miners’ vernacular meanings of blossom and prophecy to understand how they made sense of the cyclical lives of minerals. Building on this analysis, my aim is to show how the dialogues between local miners and Fra Bernat shed light on miners’ labor engagement with mineral resources through necromancy and treasure hunting. By uncovering vernacular meanings and practices, this essay contributes to the discussion on human-nature relationships in early modern Europe, demonstrating that laypeople conceptualized and engaged with nature in ways that did not always align with the economic objectives of resource managers.

THE NEWS FROM TRETTO: UNCERTAINTIES AND FUTURITIES OF MINERAL RESOURCES

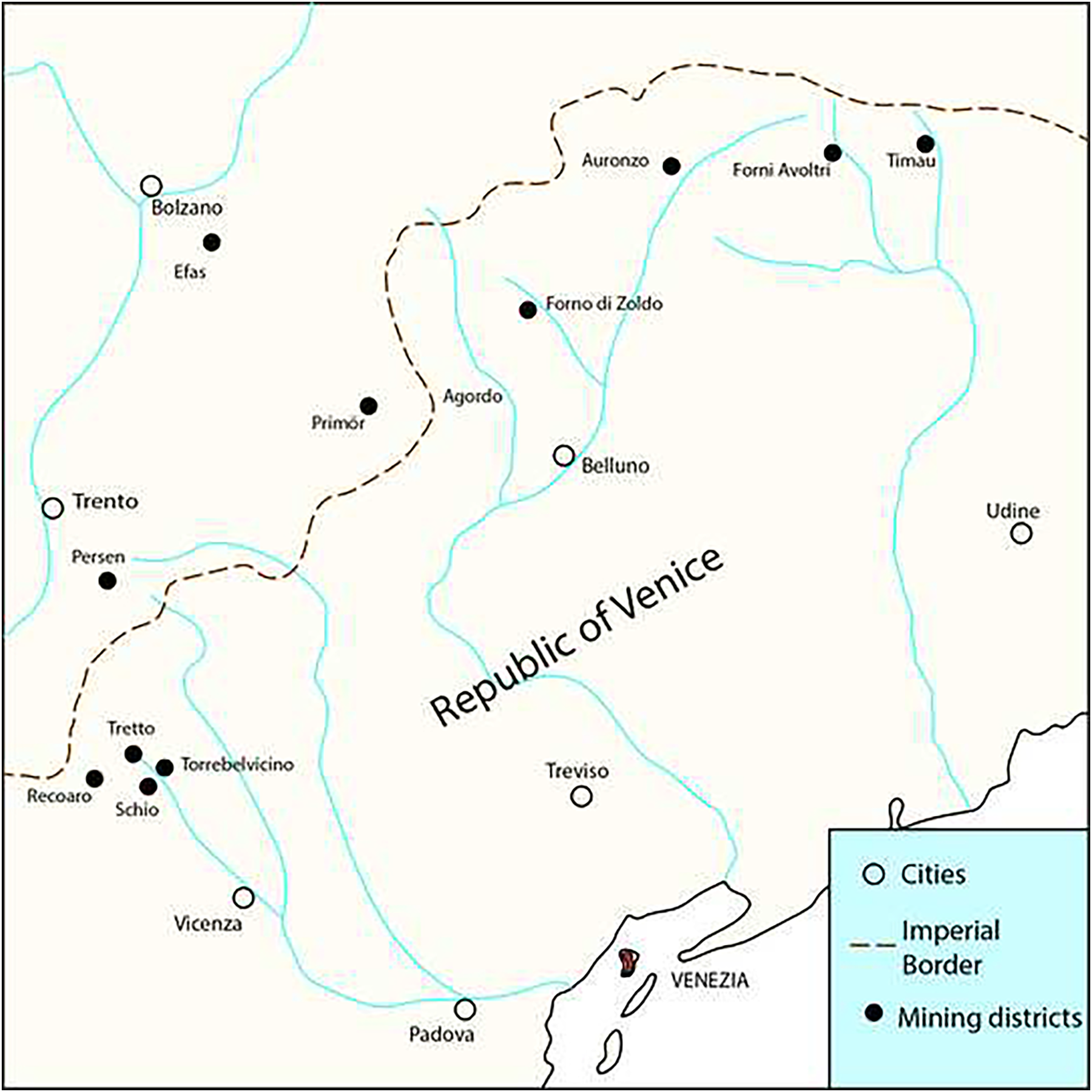

After touring the mines of Upper Germany, Austria, and Northeast Italy in 1512, the metallurgist and mining expert Vannoccio Biringuccio (1480–1539) had no doubts. The silver ores extracted from the mines of Schio and Vicenza in the Tretto upland were unequivocally deemed “the best containing the purest silver.”Footnote 19 This assessment came after he visited mines in the eastern Alpine regions, in Schwaz, Bleiberg, Innsbruck, Halle, and Rattenberg.Footnote 20 Biringuccio’s account illuminates the favorable conditions that characterized mining activities in the Republic of Venice at the turn of the sixteenth century. According to the Venetian magistrate in Vicenza, Nicolò Bernardo, miners were finding “great quantity of ores” as early as 1506 and earned high profits of around 7 to 8 ducats daily from this activity.Footnote 21 Underground resources generated prospects of immense wealth, but early modern people knew the risks all too well. In a late fifteenth-century Latin text, two friends debate the opportunities of investing in the mines, and one of them warns his companion that “if one gets rich, one hundred more work for nothing; they plunge in for gold and silver, yet dig out dirt and rocks.”Footnote 22 These uncertainties loomed large in Tretto as well. Here, scattered evidence from the financial reports of the Schio mining office indicates that mining activities did not endure beyond the 1530s.Footnote 23 In 1527, nobleman and Procurator of Saint Mark Vincenzo Grimani (1491–1546) complained that “every year incomes are sinking so much that it seems like veins are disappearing from these mountains.”Footnote 24 By 1549, the mine superintendent in Vicenza witnessed the substantial phase of abandonment of the mines by informing the Council of Ten that only “poor farmers” were working the mines in Tretto (fig. 1).Footnote 25

Figure 1. The Venetian mining districts around 1500. Vergani, Reference Vergani2003, 21.

Gorlin’s account of the Tretto and its mining community sought to revive the promising gains generated at the time Biringuccio visited the mines. Between the Middle Ages and the early modern period, medium-sized towns like Schio, Thiene, and Bassano, each with around two thousand inhabitants, played a central role in the vibrant manufacturing activities in the foothills of the Venetian Alps. Leveraging abundant timber and water resources, the region specialized in wool and silk production, exporting both low- and high-quality cloth across the Alpine pass into German-speaking regions.Footnote 26 By the turn of the seventeenth century, however, wool production in the territory north of Vicenza had declined considerably, and the silk industry still faced some regulations imposed by Venice on mainland cities.Footnote 27 As a result, local entrepreneurs from Schio and Vicenza and distant investors from Venice, Verona, and Padova shifted their focus to other possible sources of revenue, including mining. The extraction of kaolin clay already employed a significant number of the inhabitants of the Tretto in the early seventeenth century. The so-called terra bianca was mined in Tretto, sold between Vicenza and Venice, and used in the pottery industry and in painting.Footnote 28 In addition to kaolin, silver mining had long attracted the interest of Venetian noblemen such as the aforementioned Grimani and the patrician Alvise Pisani (d. 1528), also a Procurator of Saint Mark and a major investor in the largest mining partnership (compagnia granda) operating in Tretto in the 1520s.Footnote 29 This interest in the region’s mineral wealth made it relevant for Gorlin to write about the “treasures” once found in Tretto. Having been “asked many times by several noblemen about these places and that white earth and their silver mines and other metals,” Gorlin sought to address the risks surrounding mining by demonstrating how miners in Tretto dealt with the uncertainty and unpredictability of mineral resources.Footnote 30

Bridging vernacular practices with investor expectations posed significant challenges for Gorlin. His chronicle centers on the discoveries of silver deposits attributed to a German magus in Tretto. After a brief introduction outlining the community’s origins, the text is organized into seventeen sections, each devoted to a specific silver vein identified by Fra Bernat and named after a denomination of local miners (e.g., Buca della Regina or “Queen’s mine”). However, Gorlin did not witness these events firsthand. According to his father’s testament, he was born in 1569 and died in 1614, nearly a century after the mining boom in Tretto that Biringuccio situated at the turn of the sixteenth century.Footnote 31 Since Fra Bernat “came to these lands eighty or one hundred years ago,” precisely during this prosperous period, the chronicle must have been written between the 1590s and 1610s.Footnote 32 Writing at a time when the wealth of the Tretto upland had long vanished, Gorlin needed to establish his credibility as a witness to miners’ practices and as mediator between a period long gone and a potential resurgence of wealth and prosperity.

To do so, Gorlin first used miners’ testimonies. Detailed information about mineral discoveries were the result of miners’ memories of Fra Bernat’s abilities and doings, which Gorlin acquired through interviewing individuals who had worked alongside the German friar and shared their experience with the clerk. Among them was a certain Bartolomeo Todeschin, described as “a very old worker with a great memory,” as well as others whom Gorlin directly interrogated and “held memories about him and spoke with him [Fra Bernat].”Footnote 33 Although Gorlin emphasized his familiarity with those who conversed with Fra Bernat by claiming to have interviewed “the last men who worked in the mines,” it is more realistic to say that he spoke with miners who were active in the second half of the sixteenth century, not those who had directly interacted with Fra Bernat during the early mining boom in Tretto.Footnote 34 It is unlikely that miners working alongside the German magus in the 1490s lived long enough to speak with Gorlin one hundred years later.

In light of this time gap, the miners in Tretto were as much witnesses of mining knowledge as Gorlin himself. For them, Fra Bernat was not just a subject of local testimonies—as Gorlin presents him—but rather the embodiment of their own understanding of how the silver mining boom had begun a century earlier. Since those living in the 1590s still recalled Fra Bernat’s actions in detail, and no other sources corroborate his arrival in Tretto, the memory of his visit must be understood as part of miners’ vernacular knowledge of mineral resources. Fra Bernat’s presence and discoveries during the mining boom at the turn of the sixteenth century, including what miners believed were his magical and necromantic powers, were assimilated into a body of knowledge about the underground world of resources and its economic uncertainties that was passed down through the generations. It is by sourcing this local community knowledge that Gorlin describes Fra Bernat’s doings and builds his authorial credibility, a common practice among humanists and naturalists writing how-to books and treatises to attract investments in mining and bolster their reputations as men of science.Footnote 35

Gorlin deployed his professional background to intermediate between miners’ vernacular knowledge and future investors. The hearsay surrounding a German friar who unearthed rich treasures through necromantic powers likely struck noblemen and local entrepreneurs as both intriguing and ambiguous. From the second half of the sixteenth century onward, the use of necromancy (negromanzia) for treasure hunting—that is, the evocation of spirits through the consultation of prohibited books—appears with increasing frequency in the records of the Inquisition in Venice. One well-known case involved a Venetian nobleman, a friar, and several others attempting to discover “a huge mass of Gold.”Footnote 36 Yet Venetian noblemen, including high-ranking figures of the caliber of Procurators of Saint Mark, had no mining experience, were bound to reside in the city, and could not personally verify the existence of “silver veins so large that are worth millions in gold,” as described in the chronicle.Footnote 37 They relied instead on agents and factors to inquire into the status of the mines.

In his role as a local notary, Gorlin fulfilled precisely this intermediary function. Because miners’ testimonies referred to episodes and practices unfamiliar to distant investors, Gorlin legitimized their trustworthiness by providing forensic accounts of these events. Local clerks in mining territories were often called upon to witness legal transactions, such as partnership agreements between shareholders and payment contracts between mine owners and worker crews, as well as notarial deeds documenting the material conditions of miners and their families including rent contracts, dowries, and inventories.Footnote 38 As the youngest son of a local notary who operated between Schio and Tretto in the early decades of the sixteenth century, Gorlin inherited his father’s profession, granting him firsthand access to miners’ material lives and labor practices.Footnote 39 For example, he reported on the success of a miner, Zuanne dal Soglio, in 1525, personally reading the notarial deeds detailing his acquisition of “land and houses” after “selling the ores in Venice and bringing back money for himself and his family.”Footnote 40 By relying on forensic documentation on miners’ properties and fortunes that held legal validity in court, he claimed to “bear witness” (“farne memorie”) to the wealth of Tretto. The notarial documentation Gorlin had access to is strikingly similar to archival documentation available today on the Soglio family. The family appears in various notarial deeds in Tretto and Schio, and one of Zuanne’s relatives, Amadio dal Soglio, a silver smelter in Torrebelvicino, was among the four smelters who in 1531 signed a petition voicing complaints of “other smelters” against the use of a new silver refining method that allegedly worked “without fire.”Footnote 41 By presenting notarial deeds of well-known and successful individuals in Tretto, Gorlin legitimized miners’ testimonies of Fra Bernat’s findings and reinforced his credibility with readers.

Finally, Gorlin’s direct testimony further promotes mining in Tretto as a predictable and successful activity. He often portrays himself as a posthumous witness to Fra Bernat’s work, recalling events (“I remember”) and observing results (“I’ve seen his prophecies happen”) related to the German magus’s predictions in Tretto.Footnote 42 Gorlin’s ability to detect and evaluate Fra Bernat’s doings stems from his self-proclaimed status as a “professor of nature,” a title he asserts in the first pages of the chronicle. He attributes these skills to an alleged lineage tracking back to a German expert—his grandfather, “Master assayer Michael of Bayern.”Footnote 43 Michael was a German metalworker who appears in the correspondence of Venetian mining officials as the highest-ranking silver assayer of the Tretto mines in the first years of the sixteenth century. Here, Michael was renowned for his metalworking and engineering skills. In 1494, he patented a water-draining machine and used it in combination with the excavation of draining galleries to facilitate the outflow of water from the mines.Footnote 44 Gorlin makes his connection to this expertise explicit. He claims to have inherited “some regained memories I possess in my house, which were left by Master assayer Michael of Bayern,” through which he accessed his alleged grandfather’s activities.Footnote 45

By connecting to skilled workers and expertise from across the Alps, Gorlin positioned himself as the perfect intermediary between the German magus’s mining practices and investors from across the Venetian mainland. Like Gorlin, investors in Venice and Vicenza were well aware that the success of the Tretto mines in the early sixteenth century was due to the presence of German miners who came from the neighboring Habsburg territories. In 1488, the Council of Ten (Venice’s magistracy overseeing mining up until the establishment of the Deputati alle Miniere in 1665) issued new mining laws inspired by the regulations of the Tyrolean silver mines, which had experienced an economic and productive boom in the late fifteenth century.Footnote 46 The prospect of exploiting unchartered territories, combined with the existence of similar legal frameworks, made migration to the Venetian mainland attractive to German-speaking miners from Upper Germany and Austria. They brought with them advanced technical expertise that was among the most sophisticated, both technologically and bureaucratically, in early modern Europe.Footnote 47

In short, the News from Tretto engages with the futurity and uncertainty of mineral resources. Because the volatile situation of silver mining had misled prominent investors such as Vincenzo Grimani, the chronicle portrays the Tretto as a promising opportunity for new investments. Rather than writing a mining treatise grounded in humanist knowledge, Gorlin created a social and ethnographic account of the mining community, using miners’ testimonies, notarial deeds, and German expertise to build a compelling case for the profitable potential in Tretto. Gorlin’s rhetorical construction of his authorship further reinforces his role as a trustworthy mediator between miners and investors—bridging bottom-up understandings of subsoil resources and the risks of financial investments. Miners’ vernacular knowledge lies concealed behind this intermediation. For Gorlin, the time collapse between Fra Bernat’s arrival and miners’ testimonies is a gap to be bridged with other legitimizing sources. For the miners, however, it reflects how deeply the figure of the German friar was embedded in their understanding of resource landscapes. In a way, Fra Bernat was to miners what the clerici vagantes were to peasant workers in the rural community in Northeast Italy—roaming priests who wore a piece of yellow net draped over one shoulder and possessed prophetic powers over the prices of wheat and wine, and were believed to be able to influence the fertility of the fields.Footnote 48 Gorlin and prospective investors were not the only ones concerned about the futurity and uncertainty of resources—it was a central preoccupation for the miners themselves. Their accounts of blossom and prophecy attested to a vernacular knowledge system specific to the mining community, designed to address the economic risks inherent in mining operations. Legitimizing himself as a forensic expert and “professor of nature,” Gorlin introduces these concepts to investors unfamiliar with them, demonstrating that these ideas and practices serve as reliable methods for navigating the uncertainties and predictability of mining.

BLOSSOM AND PROPHECY: CONCEPTUALIZING MINING RESOURCE LANDSCAPES

Early modern mines were intricate resource landscapes in early modern Europe. While they offered the allure of substantial profits for states, individuals, and communities, mines also presented challenges that unsettled miners, investors, and mine owners. For example, one of the foremost concerns for miners was the uncertainty regarding the depth, location, and extension of underground veins.Footnote 49 In Tretto, miners confronted this uncertainty by thinking of mineral ores as present and future resources. Miners conceptualized ores as blossoming like plants and forecasted their economic potential through prophecies, viewing mineral resources as living entities whose economic viability could be anticipated. Seeing veins blossoming, then, was more than just a visual phenomenon for miners. It led them to conceptualize the subterranean world as a creator of living beings, including mineral resources.

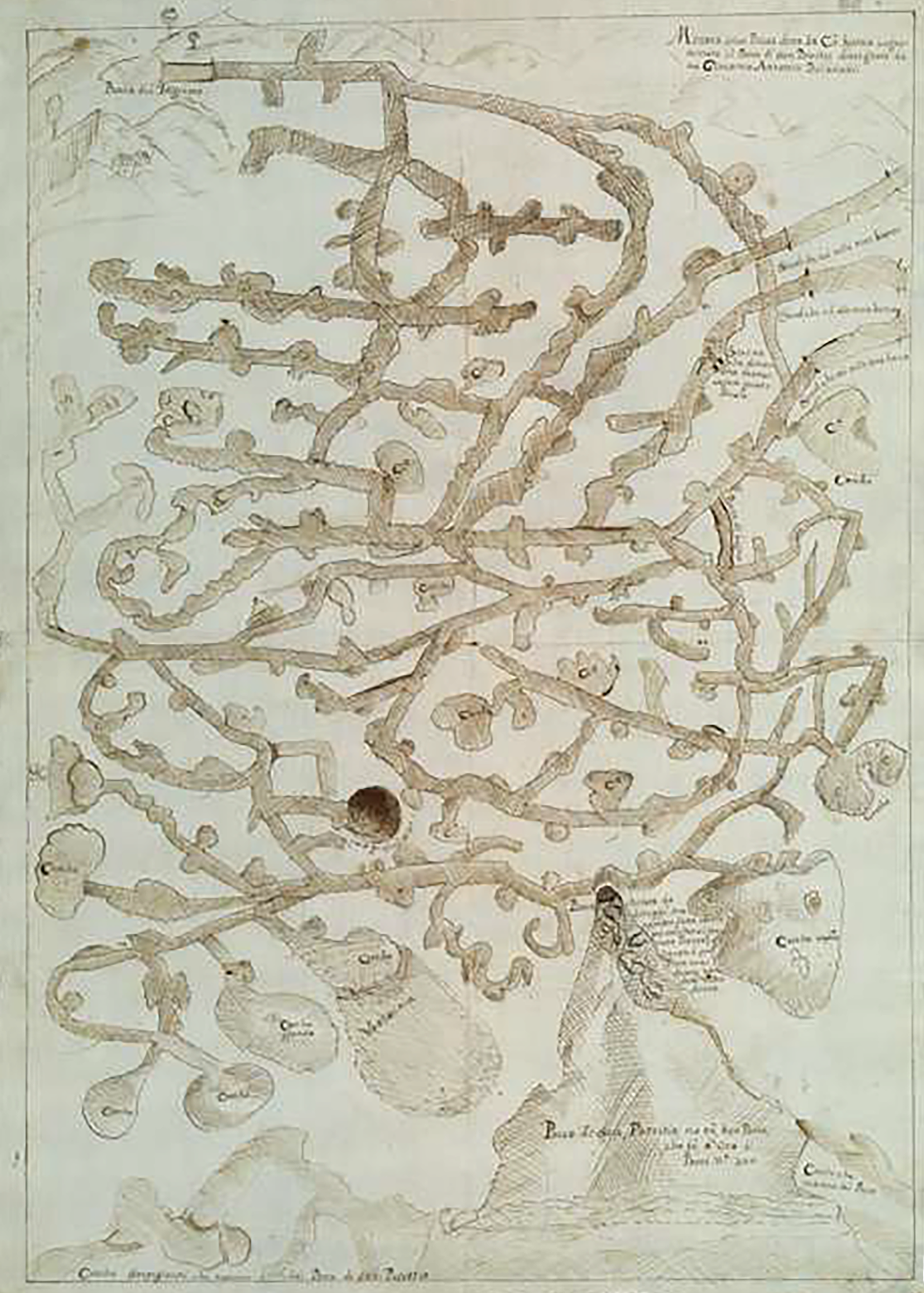

Gorlin provided a vivid description of this conceptualization based on miners’ testimonies. Two brothers, Zulian and Andrea Quartiero, recounted seeing the “Faeo vein” blossom twice in a field next to their house on Saint John’s Eve. They witnessed azure flames (fig. 2) followed by “a great noise that could have shattered nearby houses.”Footnote 50 The dual blossoming was interpreted as the ripening of ores occurring in two locations: “it starts on the part of the morning side [east] and goes towards the evening in the guise of arquebus powder set on fire.”Footnote 51 The blurring of boundaries between the subterranean world and the surface allowed other living entities inhabiting the subsoil to emerge above ground. Gasparo and Giovanni Battista, two miners who lived in Tretto, climbed a small hill to witness veins blossoming at midnight. After seeing the flames, Gasparo saw a “dark man” (“huomo negro”) emerging from the holes from which the vein blossomed.Footnote 52 Terrified, they fled, and shortly after, Gasparo “fell ill and took much time to recover.”Footnote 53 While witnessing such events put miners’ lives at risk, the sight of veins blossoming aligned with theories proposed by natural philosophers and mine practitioners who perceived mineral resources as living entities beneath the earth’s surface.Footnote 54

Figure 2. Depiction of the mine of “San Patrizio” attached to an official survey of the Tretto mines in 1681. At the bottom-right side of the drawing, the Venetian official remarked that the entrance to the gold mine was obstructed by someone “to hide the precious treasure,” and that this is the place where miners said to have seen “everything azure.” ASVe, DM, Atti, b. 279, Disegno 1. By permission of Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e il Turismo/Archivio di Stato di Venezia – Sede ai Frari. Further reproduction is prohibited.

Despite the enthralling sights of blossoming veins, establishing mining as a predictable and profitable endeavor in Tretto remained a significant challenge. Although the blossoming of veins was said to occur on Saint John’s Eve, it remained unpredictable for the rest of the year. Miners proposed two explanations for this inconsistency. The first explanation revolved around a vow made by a man named Michele Pozzan, a very poor peasant with two sons. Michele’s fortune seemed to change dramatically as he appeared to “find veins everywhere he went, whether toiling, ploughing, planting a tree or a rose, or tending to his garden.”Footnote 55 However, the wealth from his discoveries corrupted his soul: he adopted a lavish lifestyle, drinking only from “golden cups,” accumulating debts with fellow miners, and “gambling parts of his revenues.”Footnote 56 Determined to repent, Michele vowed to God to walk barefoot to the local church and celebrate mass in honor of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary, renouncing his luck and thereby sealing the community’s fate of no longer finding metals. As a result, Michele swiftly fell back into poverty, leading Gorlin to recall providing alms to Michele’s sons and grandsons.Footnote 57

Secondly, alongside the corrupting influence metals had on humans, “miners also blamed time,” believing that veins were not yet ripe “because they lacked the perfect humor.”Footnote 58 The inability to profit from these discoveries was due to the fact that the “humor and value” of the veins changed “every hundred years, according to their disposition of the generation and declination of these metals and fossils.”Footnote 59 Fra Bernat also told miners that the size of the veins influenced their attitude and their preservation: “the disappearance of small veins is easier than the bigger because the weak veins fear too much and become something that wants little or nothing, but the bigger veins do not fear and last longer.”Footnote 60 Confronted with the agency of unruly mineral resources, miners were powerless to alter the disposition and slow growth of veins.

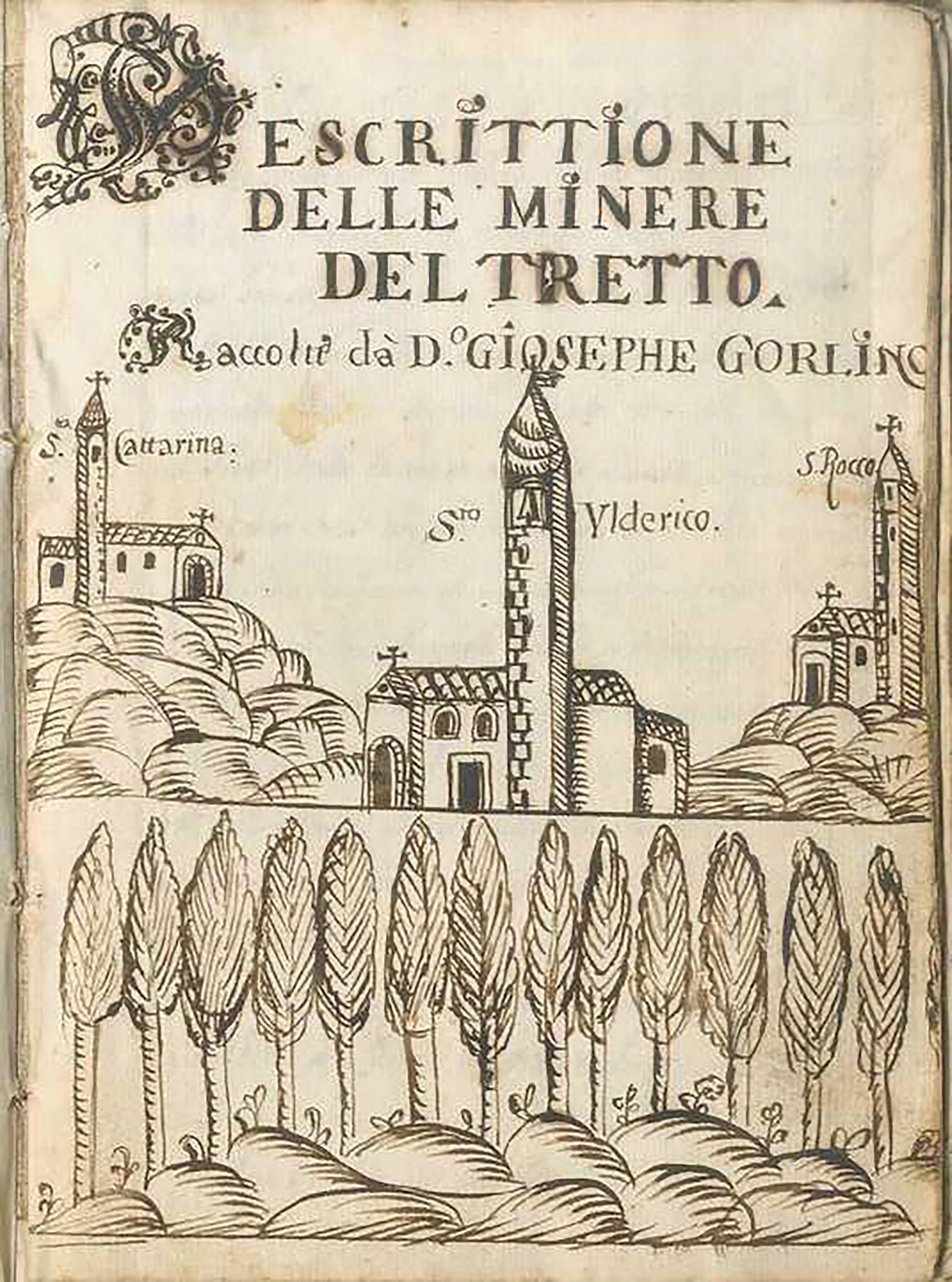

Miners coped with the unpredictable nature of silver veins by observing how they interacted with the landscape and by drawing parallels between silver ore and plants they found on the surface. During the night, flashing vamps emitted turquoise shades without warmth, scorching the soil and leaving clear traces that allowed miners to identify metal deposits on the surface.Footnote 61 Additionally, miners would estimate the “size and value” of deposits by observing the height of the flame, which corresponded to the depth reached by the vein underground: “it rises as high in the air as it goes deep beneath the vein in the earth.”Footnote 62 To detect the properties of veins, miners drew analogies with the material landscape. In the frontispiece of the 1675 copy of the chronicle (fig. 3), the depiction of the three most important churches in Tretto is accompanied by a line of trees and plants that occupy half of the page. While the trees symbolize the importance of timber for fueling furnaces and securing the shafts, the depiction also emphasizes the connections between metallogenesis and plants, a common way of articulating ideas about mining.Footnote 63 For instance, miners likened ores to the size of a “cart full of hay,” or “in guise of an onion,” requiring them to peel away layers until reaching the core where the purest metal lay hidden.Footnote 64 They also searched for an alchemical plants capable of transforming metals into gold, one in particular called “erba lunaria,” or moonwort.Footnote 65 The paragraph describing this plant deserves to be reported entirely:

during the night of Saint John, [when] one can see it blossoming and lightening as a small candle or a star, and it stands on the side of the road that goes to the Campello, so one needs to have a crossbow and…as soon as the archer will see the plant blossoming he will need to toss some rods towards the light and the next morning find the rods and next to them one will find the moonwort which will be in the guise of a red-stem plant with azure-colored marjoram leaves, with the milk [i.e., sap] like saffron and the leaves as coins.Footnote 66

Figure 3. Frontispiece of Gorlin’s chronicle copied by Giovanni Formenton in 1675. Biblioteca Bertoliana di Vicenza, Collezione Beltrame, MS 3555. Nuova Biblioteca Manoscritta. By permission of Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e il Turismo / Biblioteca Civica Bertoliana di Vicenza. Further reproduction is prohibited. https://nbm.regione.veneto.it/Generale/ricerca/AnteprimaManoscritto.html?codiceMan=65034&tipoRicerca=S&urlSearch=area1%3Dformenton+tretto&codice=&codiceDigital=.

Although Gorlin attributes the description of the moonwort to Fra Bernat, miners witnessed its alchemical power by remembering that a sheep accidentally fed on the moonwort and had “died because she could not eat anymore as her teeth had turned into gold.”Footnote 67

The interactions between mineral resources and the landscape represented a form of economic foresight that materialized as a prophecy. The ripening of veins in the underground was an inherent part of metals’ life cycle: “the humor, flower, value, and excellence [of the veins] walk away but also come back with time,” as described by miners who had allegedly spoken with the German magus.Footnote 68 They recounted seeing this promising vision of veins behaving like withered flowers that bloom anew. This phenomenon was vividly illustrated by the friar on his left-hand thumbnail: “and he showed…the future year after year on the thumbnail of his left hand…as if it was reflected in a small mirror, everything one needed to know by mind and occasion was displayed there…you could see the mount flashing, the men finding veins, running to their fellow miners, riding to Venice to secure the investitures, putting them in their bags, and returning to their companions to claim ownership of the mines and seal them with doors.”Footnote 69

While such a vision renewed miners’ hopes, the prophecy also symbolized their constant reminder of the inevitable life cycle of mineral resources. On one hand, it depicted a period of intense activities and bustling work, coinciding with the silver boom that characterized the Tretto mines in the first two decades of the sixteenth century, reconstructed by Gorlin through the recollections of old miners and notarial documents.Footnote 70 On the other, the prophecy evoked miners’ fears regarding decaying, unripe, and unproductive mineral resources. Miners recounted that “the friar said that there will be a moment when the mines here will be worth like his shoes.”Footnote 71 Gorlin corroborates the prophecy by witnessing to a similar declining situation in the last decades of the sixteenth century, noting that “it has been for twenty years that here nobody works.”Footnote 72 The decline in production in the Tretto mines was further confirmed by the accounting records of the Venetian tithe, the tax levied on refined metal, which received the equivalent of just 100 kilograms of silver in 1525.Footnote 73

Thinking of veins as blossoming prompted miners to adjust to the temporal phases of mineral resources and grapple with their cyclical nature. Witnessing the transition from the underground to the surface allowed them to conceptualize silver ores as present and future resources. However, it also confronted them with the inevitability of resource life cycles, making them realize that the blossoming would not recur, and that the mines were on the brink of decline.

LABORING NATURE

Confronted with such suggestions, Gorlin reports that miners developed an ambiguous relationship with the magus. One of the features they recollected about Fra Bernat was his ability to “see inside the mountains,” earning him the name of “gold magus, or of the mountain.”Footnote 74 These designations referred to Fra Bernat as a practitioner of natural magic and, at the same time, as the mining folklore figure of the Bergverständiger, the knower of the mountain, “who demonstrated a mastery of the hidden knowledge of nature, especially when prospecting.”Footnote 75 In Central European mining traditions, expert prospectors combined practical knowledge of minerals with the use of their body as a searching device. Similarly, when Fra Bernat stood on a vein, he would step on it with “his foot, and say ‘here’s where the vein lies.’”Footnote 76 Gorlin highlights miners’ doubts about this practice. He depicts them as skeptical of Fra Bernat—“nobody wanted to believe him”—and dismissive of his guidance as “mockeries.”Footnote 77 It was particularly Fra Bernat’s physical traits that generated confusion among miners. They described him as “a certain German friar [Fratte Todescho] who came to Tretto,…for perhaps a month and a half, during part of the carnival and almost the entire Lenten season, dressed in a very poor sackcloth that was worn and torn, and his shoes were so tattered that his heels and toes protruded through.”Footnote 78 This appearance did not align with the image of an expert miner who had enriched himself through this craft. In fact, Fra Bernat had poor physical traits and no beard (“era huomo senza barba”), leading local miners to perceive him as a woman.Footnote 79 The friar’s shabby clothes and ripped shoes also contributed to miners’ doubts. They said that “if you truly knew about this treasure you would keep it for you and you would buy new shoes and clothes with it.”Footnote 80

Gorlin’s portrayal of the local miners as suspicious of outside expertise was a widespread practice elite authors deployed in order to downplay local knowledge and create their authorial credibility. Despite this framing, the chronicle reveals that miners followed Fra Bernat’s instructions and were convinced of his mining abilities. For example, the abovementioned Bartolomeo Todeschin, who had saved the magus from an attack led by some women in the market square, was rewarded by being shown a vein that was discovered through Fra Bernat’s divination rod—the forked twig.Footnote 81 The reference to the rod demonstrates that the enrichment of miners was the result of Fra Bernat’s use of natural magic, and also indicates that miners had become familiar with his methods.

Miners who referred to Fra Bernat as a necromancer further illuminate their acquaintance with such practices. Gorlin notes that while many revered him “like a saint, others regarded him like a madman, others like a necromancer.”Footnote 82 This ambivalence reveals that while some doubted his abilities, others placed his skills within a familiar framework of labor activities and knowledge that characterized early modern miners’ practices in the underground.Footnote 83 For example, working in the depths of the mountain, the miners of Tretto knew that necromancy could be employed to confront hidden forces governing nature, including spirits and daemons.Footnote 84 Gorlin spoke with miners who believed that “any vein can’t be found if you don’t hear first its guard or Salbanello who pounds in the mountain…and the more you hear it the more certain are the signs of finding the vein soon.”Footnote 85 The materialization of these guards was indicative of the presence of rich veins, but often represented an impediment to miners’ work. Spirits and daemons populating the Buca della Regina mine tricked miners by “hiding miners’ tools every night.”Footnote 86

Necromancy helped overcome such obstacles. Dialoguing with the world of the dead was a ritual and ceremonial skill intricately associated with treasure-hunting initiatives. It aimed to invoke and command spirits, directing treasure hunters to the location of the ores. This practice was well documented in Central European mines, as well as in Northern Italy. In the second half of the sixteenth century, the Venetian Inquisition found evidence of necromantic practices employed in treasure hunting across the lagoon and the Terraferma.Footnote 87 During these ventures, groups of treasure hunters, including local noblemen and learned humanists, hired local priests to perform necromantic rituals with the aim of guiding the crew to the location of the treasure. These testimonies also revealed that necromancy was particularly effective in “exorcizing or neutralizing the spirits guarding [the treasure].”Footnote 88

Inquisition trials also reveal that necromancy was often associated with “rites and ceremonies performed according to instructions laid down in the various pseudo-Solomonic and other magical textbooks.”Footnote 89 However, miners’ portrayals of Fra Bernat as a necromancer points to a more practical use of these arts, one that refrains from the consultation of learned books and engages directly with underground resources.Footnote 90 Gorlin’s account of the construction of the local church in Tretto had already established connections between the town and the world of the dead. The fourteenth-century edifice, named after the Augsburg saint Ulrich by the first German miners who worked in Tretto, was situated in an area labeled by Gorlin as “ella, the German word for hell.”Footnote 91 Unlike the nobles and treasure hunters, miners’ use of necromancy was geared toward navigating the presence of malevolent spirits protecting mineral resources in Tretto. To release mineral ores from the guard of the spirits, “old miners and mineral practitioners” advised making some offerings, ranging from material objects to blood sacrifices.Footnote 92 A spirit might request a small “manza” (mancia, or tip), like a folded red ribbon, which allowed miners to please the sabanello who obstructed their work in the Buca della Regina mine.Footnote 93 However, bypassing these spirits could also exact a higher toll on miners. When Fra Bernat assisted Zuanne dal Scoglio and his crew in finding the rich silver vein of the Boschetto, which was concealed in a cave beneath an old field of chestnut trees, he warned them that “the first to enter may die because the guard of that treasure is in the guise of a big dragon and will do everything possible to kill the miner who enters first.”Footnote 94 To provide a trustworthy picture of a profitable activity, then, Gorlin turns to miners’ familiarity with Fra Bernat’s necromantic practices. By suggesting that miners’ offerings, including potential deaths, could expedite nature’s processes and overcome obstacles, necromancy could alter the rhythm of the subterranean world for miners’ own return.

TREASURE HUNTING FOR THE COMMON GOOD?

Blossom and prophecy represented miners’ vernacular frameworks for conceptualizing resources. Both addressed concrete phenomena and economic foresights, serving as reminders of the inevitable cyclical life of mineral resources. Necromancy, then, symbolized the concrete labor practices that could disrupt this cycle and activate mineral resources for profit at any time. How did this bottom-up understanding of the resource landscape differ from officially accepted mining practices? Economic uncertainties rendered mining a less stable occupation compared to other crafts prevalent in the Vicentine uplands, such as agriculture, grazing, and textile manufacturing, that had traditionally employed the majority of the population.Footnote 95 To elevate mining to the same level of other crafts and attract investors, natural philosophers and practitioners across Europe devised bureaucratic norms that portrayed mining as a stable, fair, and profitable activity.Footnote 96 Just like other state authorities invested in mineral extraction, the Republic of Venice sought to solve mining risks through the design of ordinances and regulations that would administrate and ensure a continuous and stable economic activity. These principles were outlined in the body of mining laws issued in 1488, first composed in thirty-three chapters and later expanded to define roles for miners, shareholders, and mine owners, while positing interactions between officials, authorities, and local inhabitants. Great emphasis was placed on the role of Venetian officials seated in the mining offices in Agordo and Schio, whose knowledge and expertise guided the management and provisioning of resources and administrated the mines in pursuit of “public and private benefit.”Footnote 97 Prospectors and surveyors, tasked with finding and measuring the location, direction, width, and extension of veins, held some of the highest and best-paid positions in the hierarchical division of labor within mining enterprises.Footnote 98 Highly skilled practitioners who could envision the properties of veins and organize the labor force accordingly became essential across Venetian mines.

The fact that Fra Bernat—not these mining officials—provided solutions to these challenges highlights the significant divide between official mining administration and miners’ resource landscapes in Tretto. Gorlin turns to the recollections of workers who had seen Fra Bernat’s prophecies and treasure-hunting practices solving the uncertainties surrounding the life cycle of minerals. “He came to get the mines back on track and was not believed,” says the chronicle, but after his departure, everything he predicted “turned out to be true, as suddenly mining improved better than ever.”Footnote 99 While some information regarding mineral deposits predates the arrival of the German friar, the chronicle emphasizes the decisive role of his contribution. For instance, the Vena del Faeo (the vein of Mount Faeo) had been abandoned until Fra Bernat provided local miners with precise guidance on its underground course, along with accurate indications of the signs left by the vein on the surface.Footnote 100

Mining officials do not appear as guarantors of mining predictability and stability, and this extends beyond the long-standing antagonism of mine laborers towards state oversight.Footnote 101 Mining officials in Tretto were also heavily criticized by shareholders and noblemen for the corrupt state of the mines. In a letter to the Council of Ten in 1527, Grimani attributed the decline of mining output to the actions of “Your Excellency’s ministers and officials…who are the principal cause of chaos and discordance, as they contribute to stealing and smuggling the veins, to tyrannizing, not administrating justice, and listening to no one but those they choose.”Footnote 102 Gorlin echoed these complaints by presenting miners’ recollections of the negative impact Venetian officials had on mining. For instance, he relies on an episode when the Venetian superintendent halted some miners who had discovered rich veins in the Orc’s Rock mine because “the tithe needed to be paid before any vein would be taken out of the mines.”Footnote 103 Miners believed they had struck it rich, but that night, while awaiting the correct procedure to be enforced, the mine collapsed, burying the rich treasure forever. The fact that Gorlin only references Venetian officials to show their ignorance of natural challenges in the underground served his intentions to renew mining activities after a period of corrupt bureaucratic interference, and it was also symptomatic of widespread distrust toward Venetian officials and their capacity to manage profitable mining enterprises.

By contrast, miners’ knowledge of Fra Bernat’s treasure hunting symbolized a different understanding of economic production and resource extraction. The inhabitants of Tretto engaged in a variety of economic activities, many of which had little to do with mining. Between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, groups of shepherds rented the hilly lands of the pre-Alpine valleys from the feudal lords of Schio and Vicenza, using them as fertile grazing areas for sheep and cattle. These shepherds also practiced agriculture, charcoal making, and wool production in Schio, but among what Gorlin called the most “ingenious” of them, there were also those who “made wooden clocks, while others entered and excavated the bowels of the Earth.”Footnote 104 This pluriactivity was a common trait of the early modern economy, and for Gorlin, it served as yet another piece of evidence of the magnetism that the hidden riches of Tretto exerted over its inhabitants and, eventually, in Venice. Yet, from the miners’ perspective, treasure hunting was not just an economic pursuit but also a reflection of their own self-perception as occasional miners. During Fra Bernat’s brief stay, the German friar’s indications favored farmers and peasants who “were poor and believed to be good people.”Footnote 105 His primary targets, then, were not professional miners but rather the improvised and multitasking inhabitants of Tretto. Engaged in various economic activities and interacting with diverse resource landscapes, the people of Tretto viewed mining as treasure hunting—an occasional pursuit that contrasted with the more continuous modes of production favored by state officials.

Although driven by individual profit-making efforts, treasure hunting in Tretto carried a resource-provisioning connotation that rivaled official mining. In a society where people acted as if material wealth was quantitatively limited and could not be increased, the pursuit of profit through treasure hunting provided impoverished individuals with the opportunity to climb the ladder of an expanding commercial society.Footnote 106 In this regard, Fra Bernat’s treasure hunting shares similarities with the reckless ore exploitation of greedy miners—precisely the kind of behavior that mining legends codified in nineteenth-century folklore sought to discourage.Footnote 107 But Fra Bernat also indicated the presence of deposits that “could be divided among the community so that nobody will be ever poor but only rich.”Footnote 108 For instance, while walking up the road leading to the village of Santa Caterina, the friar informed the local inhabitants that “here lies a gold and copper vein, the value of which will enrich the whole community due to the great commercial trade it will engender.”Footnote 109 Despite its resemblance to rash exploitation, treasure hunting, as recalled by miners, represented a distinct way of conceptualizing resource landscapes—one that contrasted with later condemnations of greedy mining. Treasure hunting was widely recognized among miners as a method of working with nature, providing alternative, locally sourced solutions that could benefit the entire community.

CONCLUSION

In 1526, the poet Giovan Battista Dragoncino (1497–1533) described the mining activities in Tretto as “the house of Vulcan,” where the “cracking sound of bellows, wheels, and hammers” was produced by “weird devices” that “shake and shudder the Earth.”Footnote 110 While these sounds and images surely captivated contemporary observers, they only scratched the surface of the complexity of mining landscapes. Miners had intricate ways of conceptualizing mineral resources that went beyond mechanical and technological extraction. Their work involved understanding the cyclical life of metals beneath the earth’s surface, where ores grew, decayed, and defined the economic prosperity of miners. This process could unfold slowly and perilously: the richness of mineral ores might not have reached its peak, leaving local miners impoverished, or it could lead to sudden and dangerous discoveries, as in the case of Michele Pozzan, whose dissolute lifestyle led him to make vows against mining. Visualizing resources during blossoming events and predicting their economic potential through prophecies shaped miners’ perceptions of mineral resources and their uncertain life patterns. Like the clanging of hammers and the dynamic movements of wheels tolled the rhythm of ore extraction and processing, strident noises and the sight of dark figures climbing the cracks of the earth accompanied the metals’ life cycles in the underground and their emergence into the world on the surface.

Chronicles like Gorlin’s account of the Tretto deepen our understanding of earth workers’ perspectives on nature. By framing the discovery of mineral ores through Fra Bernat’s abilities, Gorlin positioned himself as an intermediary between past successful production periods and new prospective interests in the Tretto mines. At the same time, through the reconstruction of the mine’s history based on the recollection of local miners, we gain insights into the vernacular meanings of nature and labor. According to miners’ views, understandings of and interactions with resources were intertwined with agrarian and mining belief systems, indicating that mining landscapes were not just sites of imagined wealth but also of active engagement with nature and its resources. Mining labor in Tretto involved efforts to overcome hidden forces and spirits through offerings that could include extreme measures such as human sacrifices. This bodily engagement with resources coexisted with agrarian rites that revolved around nature’s seasonal rhythms and provided miners with opportunities to unlocked mineral resources. The significance of the erba lunaria in this context lies in its connection to alchemical traditions, as well as with ritualistic celebrations in rural settings such as Saint John’s Eve.

Exploring miners’ interactions with mineral ores has the potential to complement and challenge historians’ contributions to current debates on human-nature relationships, offering a bottom-up and more inclusive perspective of conceptual and practical ideas of resources in early modern Europe. Focusing on the Republic of Venice, this article has shed light on two broader implications in this direction. First, vernacular practices and meanings of metals extraction found expression in various cultural layers that extended beyond humanist circles and managerial solutions. The description of blossoming events in Tretto refers to a widespread analogy between plants and metals that was used by early modern elite authors in various ways. The closest description of such phenomenon is found in Ulrich Rülein von Kalbe’s (or von Calw, 1465–1523) Bergbüchlein (Booklet on mining, 1505–18), which linked the Aristotelian-Arabic theory of the generation of metals to “fumes and vapours (called exhalationes minerales) of sulphur and quicksilver” rising from the cracks of the earth.Footnote 111 In this framework, testimonies of blossoming events in Tretto remain exceptional, especially in their detailed references to minerals interacting with the landscape, providing miners with the opportunity to anticipate the future of resources. Moreover, the notion that nature’s secrets could be unlocked through interactions with superior and intelligible creatures—such as Fra Bernat, who “knew the virtue of the heavens, metals, stones, plants, and animals”—was a widespread conviction beyond the circles of learned humanist in the Renaissance.Footnote 112 These beliefs also emerged in rural agrarian rites that articulated the daily engagement of peasants and miners with nature. In Northeast Italy, Inquisition trials investigating the cult of the Night Battles (or Benandanti) identified popular belief systems of resources that were shared among rural communities across Lower Germany, Austria, and Northern Italy. These fertility cults recognized roaming priests who approached peasants with the intent to provide them with treasures and wealth.Footnote 113

Secondly, miners’ vernacular practices often diverged from the provisioning schemes of mineral resources established by administrators and officials. Prophecy as a form of economic foresight resonated with the ambitions and anxieties of early modern miners and investors, addressing their concerns about the inherent uncertainty of mining. But resource landscapes, as a space of entanglements of plants, metals, and human activities, situated mining at the crossroads of belief systems and vernacular knowledge of nature that often diverged from official managerial practices. Gorlin’s depiction of Fra Bernat shifted the focus of collective gains away from Venetian policies and officials, and miners’ familiarity with the use of necromancy substantiated labor practices that leaned more towards treasure hunting than official mining activities. This epistemological and practical shift was not just the result of sporadic and occasional mining activity. Beyond Gorlin’s rhetorical construction of authorial credibility and his intent to build investor trust in these practices, the chronicle shows us that the inhabitants of Tretto framed mining as a distinct form of economic production based on a unique human-nature interaction—one rooted in sporadic and supplementary treasure hunting rather than the continuous extraction favored by state officials. Despite its irregular and individual profit-making nature, treasure hunting still provided the community and investors with mineral resources as effectively as, if not more effectively than, state-led initiatives. This interpretation does not aim to diminish the role of managerial organicism in resource provisioning, as envisioned by Karl Appuhn and other scholars. Examples like copper extraction in Agordo demonstrate long-term and efficient mining administration that persisted even beyond the fall of the Republic in 1797. What this article has aimed to show is a different perspective, one that did not always align with administrative practices and did not filter through their archives.

***

Gabriele Marcon is a Senior Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Economic and Social History at the University of Vienna. His research interests lie at the intersection of economic history and the history of science, with a particular focus on mining in Europe and Spanish America. He is the principal investigator of the ESPRIT research project “Mining the Earth, Roaming the Globe: German-Speaking Miners in Europe and Spanish America, 1500–1800,” funded by the Austrian Science Fund (grant DOI 10.55776/ESP324). His current book project is titled Renaissance Underground: German Mining Science and the Quest for Metals in Early Modern Italy.