The emergence of antimicrobial resistance in human pathogens is strongly linked to the use of antimicrobials in livestock (Aarestrup FM, 2015). Therefore, farmers are expected to implement reduction strategies. In dairy farming, a high volume of antibiotics is used for dry cow therapy (Kuipers et al., Reference Knappstein and Barth2016) and for decades, blanket dry cow therapy (BDCT) has been used as part of mastitis control programmes (Neave et al., Reference Müller, Nitz, Tellen, Klocke and Krömker1969) to cure and prevent intramammary infections (IMI). Since 2022, in the European Union (Regulation (EU) 2019/6) this prophylactic use of antimicrobials has been restricted to exceptional cases only. As internal teat sealants (ITS) are a non-antibiotic and well-established alternative to prevent new IMI (reviewed by Pearce et al., Reference Nitz, Wente, Zhang, Klocke, Tho Seeth and Krömker2023), different strategies for selective dry cow therapy (SDCT) are implemented and no adverse effects on udder health were observed (reviewed by Kabera et al., Reference Kabera, Dufour, Keefe, Cameron and Roy2021; McCubbin et al., Reference Lindena and Johns2022). Treatment decisions are most often based on somatic cell count (SCC) in composite milk, rather than on the detection of pathogens. Although many cows have only one or two infected quarters at dry-off (McDougall et al., Reference McCubbin, de, Lam, Kelton, Middleton, McDougall, de, Godden, Rajala-Schultz, Rowe, Speksnijder, Kastelic and Barkema2021), all quarters of the selected cows are usually treated with antibiotics.

Aiming for more targeted antibiotic use, we investigated a quarter-selective dry cow therapy (QSDCT). Previous approaches on quarter-level have already shown promising potential for reduction of antibiotic use by treatment based on the results of a California Mastitis Test (CMT) or rapid culture. For example, abstaining from antibiotic treatment of unsuspicious quarters determined by CMT resulted in a reduction of antibiotic use of 36% (McDougall et al., Reference McDougall, Williamson, Gohary and Lacy-Hulbert2022) and 31% to 87% (Swinkels et al., Reference Silva Boloña, Valldecabres, Clabby and Dillon2021). By QSDCT with treatment decisions based on growth in rapid culture, reductions of antibiotic use of 55%, 58% and 74% were demonstrated by Rowe et al. (2020), Kabera et al. (Reference Ivemeyer, Bell, Brinkmann, Cimer, Gratzer, Leeb, March, Mejdell, Roderick, Smolders, Walkenhorst, Winckler and Vaarst2020) and D'Amico et al. (Reference Crippa, de Matos, Souza and Silva2024).

Moreover, a treatment based on detecting mastitis pathogens was successfully tested at two research stations in Northern Germany (Knappstein and Barth, Reference Kabera, Roy, Afifi, Godden, Stryhn, Sanchez and Dufour2016). Following laboratory analysis of milk samples, only quarters infected with major pathogens or non-aureus staphylococci (NAS) were treated with antibiotics at dry-off. However, antibiotic treatment of NAS as the most frequently detected pathogen group before dry-off (McDougall et al., Reference McCubbin, de, Lam, Kelton, Middleton, McDougall, de, Godden, Rajala-Schultz, Rowe, Speksnijder, Kastelic and Barkema2021) should be questioned, as the risk of cure after antibiotic treatment did not significantly differ from self-cure risk (Müller et al., Reference McDougall, Williamson and Lacy-Hulbert2023).

We consequently investigated a pathogen-based QSDCT, treating only quarters of cows infected with major bacterial pathogens with antibiotics. We hypothesized that QSDCT could reduce antibiotic use on commercial dairy farms while maintaining high cure risks of antibiotic-treated major pathogens. In addition, we tested the hypotheses that neither self-cure risks of minor pathogens nor risks for new IMI by major pathogens are negatively influenced by the infection status of other quarters within cow at drying off.

Materials and methods

Herd selection

Following a call for participation published in a nationwide German farmer's magazine, 40 dairy farms expressed an interest in conducting QSDCT and supplied general farm data, data on udder health and information on dry cow management. To participate, farms had to follow a monthly milk recording scheme, be certified according to the German quality management system (QM-Milch, Reference Piccart, Verbeke, de, Piepers, Haesebrouck and De Vliegher2019) and have at least 75 cows. The motivation of farm managers, their willingness to participate in stable schools (Ivemeyer et al., 2015) and share knowledge and experiences with scientists and other farms as well as the location of the farms across Germany and the proximity to the other farms in one planned stable school area played a role in the selection process, whereas the proximity to the research institutes was not considered as a selection criterion.

A total of 16 dairy farms were selected. To assess the udder health status of the herds, a basic survey was conducted, where quarter milk samples from approximately 75 randomly selected lactating cows per farm were collected (Beckmann et al., Reference Beckmann and Barth2025 and K. Knappstein, accepted). After sampling, one of the farms was excluded due to a high prevalence of contagious pathogens (29% of cows) and another was excluded due to difficulties to organise sampling in the appropriate time schedule. Two other farms replaced these farms, resulting in 16 dairy farms finally included in the study.

The herd size of the farms averaged 309 cows, ranging from 79 to 1,280 cows. Three of them were organic farms. In 2021, the average annual milk yield per cow was 9,642 kg (ranging from 7,911 to 11,217 kg) and the average milk SCC based on monthly milk recording ranged from 138,000 to 335,000 cells/mL. German Holstein was the dominant breed on most farms (farm data: Supplementary Table S1).

On all farms, dry cows were housed separately from the main herd, mostly in free-stall barns during the first weeks after dry-off and on deep bedding 2 or 3 weeks before calving. Except for four farms, all dry cows were kept on pasture or had access to pasture during the summer months. All lactating cows were also housed in free-stall barns. Eleven farms milked their cows in a parlour, two farms in a rotary, two farms used an automatic milking system and one farm used both a parlour and an automatic milking system. One farm milked three times per day, all other farms milked twice daily. Before the beginning of the project, all farms used SDCT on cow level, primarily based on SCC of milk at the last or the last three milk recordings before drying off (Supplementary Table S2).

Sampling and laboratory procedures

Quarter milk samples were scheduled from approximately 75 drying off procedures per farm. This sample size per farm was based on the average herd size in Germany in order to achieve a sufficient number of dry periods within the limited study period even for medium-sized farms while avoiding repeated inclusion of cows. Depending on the herd size, the sampling was conducted during a time period of 5 to 18 months per farm between February 2021 and December 2022. During the study, the strategy included sampling of each cow at least 14 days before the scheduled drying off date and again 3 to 5 days after calving. In case of unclear microbiological findings, resampling was required the following week (Supplementary Figure S1). On 11 farms, all cows that entered the dry period were included. With regard to seasonal effects, in herds > 300 cows, approximately 10 cows per farm and month were randomly selected by farm personnel based on readiness for dry-off in the respective calendar week. Farm staff responsible for sampling was trained with leaflets, videos and personal instructions. On most farms, sampling was performed mainly by the farm or herd manager and early in the week to avoid extended mail delivery time. Cows with clinical mastitis symptoms (i.e. clots, wateriness, heat, swelling of the udder) on the first 2 days after calving had to be sampled immediately and before antibiotic treatment. If postpartum sampling took place from Friday to Sunday, farmers were asked to store the samples in a refrigerator until shipment, early in the following week.

Bacteriological analysis was performed at the laboratory of the Max Rubner-Institut (Kiel, Germany) according to the guidelines of the German Veterinary Medical Society (Reference D'Amico, Neves, Grantz, Taechachokevivat, Ueda, Dorr and Hubner2018). Briefly, 0.05 mL per quarter milk sample were spread on a blood agar plate and incubated 18-24 h at 35°C. If no growth was detected, incubation was prolonged to 48 h. Isolates were subcultured on blood agar and identified based on biochemical reactions. Somatic cell count in quarter milk samples was determined by flow cytometry according to ISO 13366-2 by a Fossomatic FC (Foss GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). For details on laboratory analyses see Supplementary file.

Definitions

The IMI status of the udder quarter was based on bacteriological analysis: No IMI: no bacteriological growth observed; IMI with major pathogen: Detection of at least 1 colony corresponding to 20 cfu/mL of milk of the following species: Staphylococcus (S.) aureus, Streptococcus (Str.). dysgalactiae, Str. uberis, other esculin-positive streptococci including enterococci, Gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli, Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., Klebsiella spp., Serratia spp., Proteus spp., Pasteurella spp. and Pseudomonas spp., Trueperella pyogenes, yeasts; IMI with minor pathogen: Detection of more than 20 colonies of NAS and Corynebacterium spp. corresponding to bacterial counts exceeding 400 cfu/mL; Mixed IMI: Detection of two different pathogens with at least one major pathogen; Contaminated sample: growth of at least three different colony types, considered as no IMI if quarter SCC ≤ 200,000 cells/mL and as IMI if quarter SCC > 200,000/mL of milk.

Based on the comparison of IMI status of the same quarter before dry-off and after calving, the following definitions were applied: Cure of IMI: the initial pathogen present at drying off was absent after calving or a different pathogen was identified after calving; Persistent IMI: detection of the same pathogen at dry-off and after calving; New IMI: no IMI at dry-off but IMI after calving, different pathogens identified at dry-off and after calving, treatment of a previously uninfected quarter for clinical mastitis at any stage during dry period or clinical symptoms at sampling after calving, even if no pathogen was detected. By definition, a quarter with different pathogens before dry-off and after calving was considered at risk for developing both a dry period IMI cure and new IMI.

Dry cow strategy

The farm specific results of the basic survey (Beckmann et al., Reference Beckmann and Barth2025 and K. Knappstein, accepted) and the QSDCT planned were discussed via web conferences with the respective farm managers and their consulting veterinarians. Treatment decisions were made at the quarter level and based on the bacteriological outcomes:

- For quarters either not infected or infected with minor pathogens, only ITS were applied.

- Quarters infected with major pathogens were treated with antibiotics and ITS. Only if IMI with major pathogens were detected in at least three quarters within cow, all quarters received antibiotic treatment. The choice of drug was the responsibility of the farm veterinarian. Fourteen of 16 farms used long-acting antibiotic drugs with at least two active ingredients (mostly penethamate hydriodide, benethamine penicillin and framycetin sulfate).

- When yeasts were detected neither antibiotic nor ITS were used to avoid the risk of introducing other pathogens into the quarter.

- On two farms, IMI with NAS in combination with a quarter SCC > 500,000 cells/mL were treated with antibiotics and ITS – on one farm because of a generally increased IMI rate by NAS in the basic survey and on the other farm at the request of the farm manager. However, many of these NAS isolates showed antibiotic resistance; therefore, both farm managers discontinued antibiotic treatment of NAS.

Data collection and statistical analyses

For each cow sampled, breed, date of birth, parity and relevant dry-off and calving dates were recorded. Data on milk yield (in kg per cow and day) and SCC in composite milk (in 1,000 cells/mL) of the last three recordings before dry-off were taken from monthly milk recording data per dry period and cow. Information on any abnormalities of milk samples (e.g. clots, atrophied quarters, current antibiotic treatment) as well as the results of bacteriological analysis, resistance testing and recommended dry cow therapy were recorded per quarter.

All participating farms already used selective dry cow strategies at the cow-level before the study commenced (Supplementary Table S2). The theoretical antibiotic use according to the previous strategy of SDCT was estimated per farm based on milk recording data, quarter milk SCC on the sampling day before dry-off (used to replace CMT results for farms where CMT was performed at dry-off), or previous udder diseases. Based on this estimate the potential for reduction of antibiotic use by QSDCT was calculated.

Cows that were culled, died or failed the inclusion criteria were excluded from the analyses (Supplementary Table S3). The statistical unit was the udder quarter and all statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Three outcomes of interest were investigated: Cure of IMI with major pathogens, self-cure of IMI with minor pathogens and new IMI with major pathogens. After a descriptive data analysis, binomial logistic regression models using SAS procedure GLIMMIX and a logit link function were calculated. Fixed effects were added to the models using step-wise forward selection and all possible two-way interactions were tested. The best model was selected according to the lowest Akaike's information criterion. For the cows with two dry periods during the study period, both were included in the descriptive analysis. For the statistical analyses, one of these dry periods was randomly selected (coin toss) to avoid introducing another level of nesting.

Possible effects on the cure of major pathogens (uncured/cured) could not be examined using a statistical model due to the very small number of uncured quarters.

To explore possible effects on the self-cure of minor pathogens (uncured/cured), only data of cows that were dried off without antibiotic treatment were used. The final model included minor pathogen group (NAS, Corynebacterium spp.), quarter SCC group (categorized as ≤ 100,000; 101,000 – 200,000; 201,000 – 400,000 and > 400,000 cells/mL), the quarter location (front, hind quarter) and the presence of at least one other infected quarter with minor pathogens within cow (no, yes) at dry-off as fixed effects. Due to the low variation of the outcome variable between the farms, only a random intercept for cow was included in the model to account for the clustering of quarters within cow. Due to significant correlations with quarter SCC group, neither the parity group at dry-off (categorized as 1; 2; ≥ 3) nor the milk yield group at last recording before dry-off (categorized as < 15.0; 15.0 – 19.9; 20.0 – 24.9 and ≥ 25.0 kg) entered the model as fixed effects.

To test for possible effects on the outcome variable new IMI with major pathogens after calving (remained uninfected/newly infected with major pathogens), only quarters that were not infected before dry-off and received only ITS were included in the model. In general, cows infected with yeasts as well as cows that received antibiotics on all quarters, on contaminated quarters or on quarters infected with minor pathogens were excluded. In the final model, only the presence of at least one quarter infected with major pathogens within cow at dry-off (no, yes) was included as fixed effect. As only quarters without IMI at dry-off entered the model, this fixed effect compared the new IMI risk between those cows with and without major IMI at dry-off. Cow and farm random intercepts accounted for the clustering of quarters within cow and cows within farm. Due to significant correlations with the presence of at least one quarter infected with major pathogens within cow at dry-off, neither the parity group nor the quarter SCC group at dry-off entered the model as fixed effects. The effect of having at least one quarter infected with minor pathogens within cow (no, yes) and the effect of quarter location were tested, but led to a higher Akaike's information criterion.

Statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 1,478 dry periods were sampled on the 16 farms between February 2021 and December 2022. Overall, 323 (21.9% of enrolled) of the data sets of dry periods were excluded from the study (Supplementary Table S3). In addition, 90 individual quarters were excluded from the analysis due to a missing diagnosis before dry-off or after calving (i.e. atrophied udder quarters, contaminated blood agar plate, leaking vials). Finally, 1,155 dry periods of 1,126 cows were included in the descriptive analysis comprising 4,530 quarters. The number of cows analysed per farm ranged between 60 and 83. One farm had only 31 eligible cows.

Proportions of sampled cows in parity 1, 2 and ≥ 3 were 34.1%, 27.2% and 38.7%, respectively. Cows had an average dry period length of 52 ± 9.6 days (mean ± standard deviation). At milk recording before dry-off, mean milk yield per cow and day was 19.8 ± 6.4 kg (farm data: Supplementary Table S4). On average, cows were sampled 16 ± 5.2 days before dry-off and 5 ± 2.6 days after calving.

Prevalence of IMI at dry-off and antibiotic use

Within the 4,530 quarters remaining for analysis, major pathogens were responsible for 6.9% (n = 314/4,530) of IMI before dry-off (Supplementary Table S5). About one third (n = 101/314) of these IMI were caused by Str. uberis. Minor pathogens were detected in 13.1% (n = 595/4,530) of the quarters, representing about 60% of all IMI (595/988) before dry-off. 1.7% (n = 79/4,530) of all quarters were considered as infected due to high SCC in contaminated samples.

At drying off, 8.1% of all quarters (366/4,530) were treated with antibiotics, consisting of 312 quarters with IMI by major bacterial pathogens and 54 quarters for other reasons. Depending on the farm and the IMI status of the herd, antibiotic usage varied from 2.6% to 28.8% of quarters (Supplementary Table S6). The farm that contributed only 31 eligible dry periods to the whole data set had an even lower percentage of 1.7% treated quarters. According to the previous criteria for SDCT applied by the farms before the study (Supplementary Table S2), 42.2% of the quarters (= equivalent to the number of treated cows) would have been treated with antibiotics, ranging from 30.2% to 68.4% depending on the farm (Supplementary Table S6). Thus, QSDCT resulted in a further potential for reduction of antibiotic use of 80.8% on average (formula: (1 – (8.1/42.2)) *100).

Bacteriological cure risk

Cure risks of IMI were calculated for quarters with distinct culture result (contaminations not included) that were dried off according to the strategy and varied by pathogen and treatment at dry-off (Table 1). The bacteriological cure risk of antibiotic-treated quarters infected with major pathogens was 97.1%. The lowest cure risk was found for S. aureus with 86.2%, whereas all other species showed cure risks above 95%. Self-cure risks of 81.6% for NAS and 83.0% for Corynebacterium spp. left untreated were observed (Table 1). In the few cases of antibiotic treatment, IMI caused by NAS (n = 15) and Corynebacterium spp. (n = 3) were completely cured (data not shown).

Table 1. Bacteriological cure risks of intramammary infections (IMI) with major pathogens after antibiotic treatment and IMI with minor pathogens without antibiotic treatment at the quarter level at dry-off

1 Quarters with a different minor and/or major pathogen after calving compared to the initial pathogen present at dry-off or quarters infected at dry-off that had clinical symptoms without pathogen detection after calving.

2 Including enterococci.

3 Escherichia coli, Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., Klebsiella spp., Serratia spp., Proteus spp., Pasteurella spp., Pseudomonas spp.

4 Isolation of two different pathogens on the same quarter. Each mixed IMI had at least one major pathogen to which cure risk was related.

5 Minor pathogens were only considered as IMI if bacterial counts exceeded 400 cfu/mL.

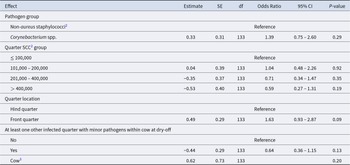

The statistical analysis regarding self-cure risk of IMI with minor pathogens included 455 quarters from 317 cows. The model revealed that self-cure of IMI by minor pathogens was not affected by the detected pathogen group (Table 2). In addition, neither the level of quarter SCC nor the quarter location or the presence of at least one other infected quarter at dry-off had a significant effect on the self-cure risk of IMI with minor pathogens.

Table 2. Model terms1 of the final mixed logistic regression model for self-cure risk of quarters infected with minor pathogens at dry-off from 16 herds in Germany

1 CI = confidence interval; df = degrees of freedom; SE = standard error.

2 SCC = somatic cell count; in quarter milk samples before dry-off.

3 Random effect.

Prevalence of IMI after calving and new IMI risk

In total, 781 out of 4,530 (17.2%) quarters were infected after calving, with 219 (4.8%) quarters infected with major pathogens, 484 (10.7%) quarters infected with minor pathogens, 16 (0.4%) quarters with clinical symptoms and 62 (1.4%) quarters were contaminated with > 200,000 cells/mL (Supplementary Table S5). Although the percentage of IMI with major pathogens before dry-off and after calving were in a similar range, only 4.6% (10/219) of the IMI after calving had persisted over the dry period. The vast majority was new IMI and in half of the farms, at least as many quarters became newly infected with major pathogens as were cured over the dry period. Among 665 of 4,530 quarters (14.6%) with new IMI after calving (contaminations and quarters with clinical symptoms included), the microbiological findings were primarily minor pathogens with 57.3% (n = 381), followed by 9.8% Str. uberis (n = 65), 8.9% contaminated quarters with SCC > 200,000/mL (n = 59), 5.9% other esculin-positive streptococci (n = 39) and 5.4% Gram-negative bacteria (n = 36). Thus, the majority of major mastitis pathogens were of environmental origin (Supplementary Table S5).

Regarding the new IMI risk in dependence of treatment, 16.0% (565/3,525) of the untreated quarters that had no IMI before dry-off showed new IMI after calving (range per farm 8.3% – 35.0%), whereas 9.7% (56/577) of the untreated quarters with IMI by minor pathogens (range per farm 0.0% – 17.7%) and 8.7% (27/312) of the antibiotic-treated quarters with IMI by major pathogens (range per farm 0.0% – 30.0%) had new IMI after calving (Table 1).

Regarding new IMI with major pathogens the data basis of the final model included 3,028 quarters from 1,028 cows. Results from the logistic regression model indicated that the presence of at least one quarter infected with major pathogens within cow did not increase the risk for new IMI in uninfected quarters compared to those cows that were not infected with major pathogens before dry-off [Odds Ratio = 2.01, df = 2,000, 95% CI: 0.72–5.65, P = 0.19].

Discussion

The farmers participating in this study might not be representative of German dairy farms as they responded voluntarily to a call in a farmer's magazine, had initial experience in SDCT and an interest in sustainable reduction of antibiotic use. Considering that one farm had to be excluded after the basic survey due to high prevalence of S. aureus and Str. agalactiae and that in two of the participating farms 21% and 22% of all quarters were infected with major pathogens before dry-off, farmers’ interest in reducing antibiotic usage did not seem to be uniformly associated with a low prevalence of IMI caused by major pathogens. However, the interest in reduction of antibiotic use is reflected in dry cow strategies as all but two of the farms had several years of experience with ITS and all farms already used SDCT. This is in contrast to other German dairy farms, where 60% of 7,300 participants in a survey routinely used BDCT (Lindena and Johns, Reference Kuipers, Koops and Wemmenhove2020).

In general, the current study is limited by the lack of a true control group with a different strategy. While a BDCT control group could not be included as the European Regulation (EU), 2019/6 specifies that antimicrobials should not be applied routinely, a SDCT control group was not included with intention. Many previous studies have already shown that SDCT is possible without adversely affecting udder health (reviewed by Kabera et al., Reference Kabera, Dufour, Keefe, Cameron and Roy2021; McCubbin et al., Reference Lindena and Johns2022). Instead, it was decided to use the selection criteria previously applied on the farms in order to carefully estimate the potential for reduction of antibiotic use when transitioning from SDCT to QSDCT.

Collecting triplicate milk samples one week apart is often considered to be the gold standard sampling strategy to detect IMI (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Dohoo, Olde Riekerink and Stryhn2010). However, this is too time consuming and expensive for commercial dairy farms. In order to detect IMI as precisely as possible with one sampling, 0.05 mL per quarter was spread on a blood agar plate and quarters were considered infected if ≥ 20 cfu/mL of major pathogens were found. This threshold was intentionally set low to avoid missing IMI, but with the risk of unnecessarily treating quarters based on contaminated samples. However, in 95% (296/312) of quarters with IMI by major pathogens 100 cfu/mL were exceeded. Including SCC in the definition of IMI with major pathogens would have made only little difference because only 12 quarters had SCC < 100,000/mL (data not shown). Detection of minor pathogens was only considered as IMI with > 400 cfu/mL to avoid overestimating cure risks or new IMI risks. Since no exact species identification of minor pathogens was performed, cure and new IMI with the same pathogen may be misclassified as persistent IMI. Furthermore, the sampling times were a compromise to afford enough time for laboratory analysis and to reduce the risk of missing IMI. In samples taken too close after calving, the detection of pathogens might be compromised by the inhibitory property of colostrum or the possible presence of antibiotic residues.

In the current study, using a pathogen-based QSDCT resulted in an average antibiotic usage on 8% of all quarters with high variations between the farms (Supplementary Table S6). Although recent quarter-based studies also reported reductions of antibiotic use, antibiotic use was eight times higher (64%) when treatment was based on CMT score ≥ 'trace' (McDougall et al., Reference McDougall, Williamson, Gohary and Lacy-Hulbert2022) and about five times higher (42% and 45%) when treatment decisions were based on “growth” on rapid cultures (Kabera et al., Reference Ivemeyer, Bell, Brinkmann, Cimer, Gratzer, Leeb, March, Mejdell, Roderick, Smolders, Walkenhorst, Winckler and Vaarst2020; Rowe et al., 2020). Even when only quarters were treated with antibiotics that showed growth on selective media for Gram-positive bacteria, the antibiotic usage observed was three times higher (26%) than in our study (D'Amico et al., Reference Crippa, de Matos, Souza and Silva2024). Compared to the SDCT previously practiced on the participating farms, QSDCT resulted in an additional 81% reduction of antibiotic usage in our study. However, this calculation was an estimate and farmers could consider additional information leading to more or less antibiotic treatment at dry-off.

For the evaluation of the reduction of antibiotic use, it is essential that cure risks of IMI are not impaired. In general, the cure risk of 97% for IMI with major pathogens was very high in the current study. Given that other quarter-based approaches also reported high cure risks (Kabera et al., Reference Ivemeyer, Bell, Brinkmann, Cimer, Gratzer, Leeb, March, Mejdell, Roderick, Smolders, Walkenhorst, Winckler and Vaarst2020; Rowe et al., 2020; Swinkels et al., Reference Silva Boloña, Valldecabres, Clabby and Dillon2021; McDougall et al., Reference McDougall, Williamson, Gohary and Lacy-Hulbert2022; Silva Boloña et al., Reference Schmenger and Krömker2025), there was no evidence to suggest negative effects of quarter-level treatment on bacteriological cure risks. Since antibiotic treatment of IMI caused by Gram-negative bacteria showed no additional benefit compared to self-cure at dry-off (Müller et al., Reference McDougall, Williamson and Lacy-Hulbert2023), additional reductions of antibiotic use could be achieved leaving them untreated. However, this would make only little difference (0.5%) in terms of reducing antibiotic usage in the current study due to the low prevalence at dry-off. Furthermore, the low prevalence of Gram-negative bacteria and the majority of IMI being caused by Gram-positive bacteria emphasized the possibility of using narrow spectrum antibiotics at dry-off. When interpreting the high cure risks for antibiotic-treated quarters in this study, it is important to note that targeted antibiotic use was always in accordance with the results of resistance testing. The consistent use of ITS as a barrier to pathogen entry may also have improved the calculated cure risks by preventing reinfections with the same pathogen which would not have been differentiated from persistent IMI.

Given that increasing antimicrobial resistance in NAS is worrying (reviewed by Crippa et al., Reference Browning, Mein, Brightling, Nicholls and Barton2024), withholding antibiotic treatment from IMI with minor pathogens was an important part of the strategy. Antibiotic use would have been 2.6 times higher if minor pathogens had been consistently treated with antibiotics. The high self-cure risks indicated no need for antibiotic treatment which is supported by results from other studies also describing high self-cure risks of 87% for minor pathogens (McDougall et al., Reference McDougall, Williamson, Gohary and Lacy-Hulbert2022), or 68% (Müller et al., Reference McDougall, Williamson and Lacy-Hulbert2023) for NAS only. However, given that NAS are also found in clinical mastitis samples (Schmenger and Krömker, Reference Rowe, Godden, Nydam, Gorden, Lago, Vasquez, Royster, Timmerman and Thomas2020), some veterinarians initially expressed concerns about leaving NAS untreated (especially in cases of a high SCC). The assumption, that certain strains cause higher SCC (Piccart et al., Reference Pearce, Parmley, Winder, Sargeant, Prashad, Ringelberg, Felker and Kelton2016) and might be more resistant to self-cure was dispelled, as no significant effect of the level of SCC on the self-cure was found in our study.

In the past, the use of antibiotics at dry-off was aimed not only at treating existing IMI but also at preventing new IMI. It is therefore important to consider the new IMI risk in dry cow strategies, but study comparisons are difficult due to different definitions for IMI and the use of ITS alone or in combination with antibiotics. While an older field trial without ITS indicated an increased risk for new IMI in untreated quarters (Browning et al., Reference Beckmann and Barth1994), this higher risk could not be confirmed in more recent quarter-level field studies using ITS (Kabera et al., Reference Ivemeyer, Bell, Brinkmann, Cimer, Gratzer, Leeb, March, Mejdell, Roderick, Smolders, Walkenhorst, Winckler and Vaarst2020; Rowe et al., 2020). In contrast, a recent Irish study (including only cows with one IMI and using ITS) found a higher risk of new IMI in uninfected quarters when comparing QSDCT with BDCT (Silva Boloña et al., Reference Schmenger and Krömker2025). However, this conclusion was based on new IMI definitions including SCC and/or culture and S. aureus dominated in the herds (Silva Boloña et al., Reference Schmenger and Krömker2025). As in the present study, a major IMI did not increase the risk for a new IMI in uninfected quarters of the cow compared to those cows without major IMI, future studies should include an uninfected treatment group. Compared to studies reporting new IMI risks of 17% (Kabera et al., Reference Ivemeyer, Bell, Brinkmann, Cimer, Gratzer, Leeb, March, Mejdell, Roderick, Smolders, Walkenhorst, Winckler and Vaarst2020) and 20% (Rowe et al., 2020) in BDCT + ITS groups, the new IMI risk in our study was in the same range despite a much lower antibiotic usage. This illustrates that BDCT is not of advantage in terms of preventing new IMI.

Sixty-five percent of newly infected quarters in our study were minor pathogens and 35% were major pathogens. Among the latter, 76% were environmental pathogens. Since the presence of at least one quarter infected with major pathogens did not increase the risk of a new IMI in uninfected quarters of the cow, other factors during the dry period seemed to be responsible. Different factors at quarter level (e.g. hyperkeratosis on teat end) and cow level (e.g. parity, body condition score, SCC), as well as hygiene management factors at farm level (e.g. frequency of bedding cubicles and cleaning calving pens), are known as risk factors for new IMI and clinical mastitis after calving (Green et al., 2007; Nitz et al., Reference Neave, Dodd, Kingwill and Westgarth2021). Thus, sustainable reduction of antibiotic usage by QSDCT must also focus on these factors to prevent new IMI.

In conclusion, QSDCT based on bacteriological outcomes can be successfully applied on commercial dairy farms, resulting in a substantial reduction of antibiotic use. High cure risks of IMI with major pathogens were achieved by targeted antibiotic treatment, whereas high self-cure risks of IMI with minor pathogens indicated no need for antibiotic treatment at dry-off. However, the necessity for prevention of new IMI became obvious in order to achieve a long-term reduction of antibiotic consumption.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029925101234.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all participating dairy farmers for performing the sampling, implementing this dry cow strategy and sharing their experiences. We thank the laboratory staff of the Max Rubner-Institut (Kiel, Germany) for their technical assistance. For their helpful comments on the manuscript, we would like to thank Christina Umstätter and Eberhard Hartung. This work (Model- and Demonstration Project for animal welfare) was financially supported by the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture based on a decision of the Parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany, granted by the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food, grant number 2819MDT211/212.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was not necessary because the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are routinely applied on commercial dairy farms for assuring animal health.

Competing interests

The authors have not stated any conflicts of interest.