Blackface, a quintessential signifier of the minstrel repertoire, continues to travel through time and space frequently unmoored from knowledge about its antecedents. Or so claim its embodiers; others are all too aware of its racist citationality.Footnote 1

In the nineteenth season of the Polish edition of the popular television format Twoja Twarz Brzmi Znajomo (Your Face Sounds Familiar, autumn 2023; Polsat), Jakub Szmajkowski, a relatively anonymous male singer performed an impersonation of the globally acclaimed American rap star Kendrick Lamar. The white singer copied the Black rapper’s dance moves, characteristic high-pitched voice, and also his skin color. Darkened by professional make-up artists, with his hair braided in cornrows, he skipped all the f-words, yet not the N-word. Szmajkowski’s performance delighted the jury and won him the whole competition, whose basic premise is to “transform into different legendary singers.”Footnote 2

This was by no means the first time blackface has appeared in the Polish version of the show, which started off in 2011 in Spain, was developed by the multinational corporation Benijay Entertainment headquartered in France, and has been present in more than forty countries around the world. In the eighteen previous seasons of the show in Poland, darkening celebrities was a common practice (in the impersonations of among others Beyoncé, Grace Jones, Michael Jackson, Louis Armstrong, or Lizzo).Footnote 3 Moreover, the racist controversy is a part of the show’s global history, as performances in blackface were recorded also in Spain, Greece, Italy, Czechia, Croatia and China.Footnote 4

In Poland, the use of blackface had already been a matter of debate in 2018 (impersonation of Drake) and 2021 (Kanye West and Tina Turner), though their dynamics differed from the most recent case. They started with public outrage expressed online, followed by articles in the gossip press, eventually forcing a reaction from the local branch of Benijay. The 2018 statement proudly listing some of the show’s “legendary performances” involving blackface, opens with the ignorant expression of being “greatly surprised … with the numerous negative comments.”Footnote 5 Feeling surprised at an accusation of anti-black racism is one of the narrative tropes for the Polish version of what Gloria Wekker deemed “white innocence,” constituted by reactions of “denial, disavowal, and elusiveness” at any mention of the entanglement of race in relations of power.Footnote 6 In Poland, it is often paired with a self-assuring “colonial exceptionalism,” defined by Filip Hertza as superiority built on the assumption of being historical outsiders to colonialism, “obscur[ing] the many ways in which the region communicated and interacted with global Empires… .”Footnote 7

The producer’s statement unapologetically doubles down on the show’s copycat formula: the artists are constantly “striving to be as close to the original [performance] as possible,” they “intend … to faithfully mirror the [original] performance and honor the artists.” Facing this combination of declared mimicry and alleged affirmation, one could simply repeat race and performance scholar Ayanna Thompson’s rhetorical question: “Will it surprise you to learn that the early nineteenth-century originators of blackface minstrelsy claimed their performances were both imitative in an ethnographic way and celebratory of black culture?”Footnote 8

The exhibitory value of the Black body under the control of a white performer and white judges, embodied for the satisfaction of a white public, needs to be reinterpreted to take into account the relations of power anchored in referencing blackness in Poland today, as well as the historical formulas of recognizing and imagining blackness. The synchronic and diachronic orders are both crucial for understanding how a society without history of overseas colonies and Black enslavement engaged in colonial imagination and racial hierarchies.Footnote 9

Not long after Szmajkowski’s impersonation, Benijay announced that it “condemns” its Polish branch and decided to ban cross-racial performances globally.Footnote 10 Thus, not only the formula, but also the intervention came from the outside, in this case both through a top-down structure of corporate management, and via the geographical power axis; from the global center to the extra-colonial territory with its “lateral society.”Footnote 11 The whole uproar did not fuel sufficiently convincing arguments against cross-racial impersonations in Poland.

Out of multiple possible ways of understanding what actually happened, we would like to propose a historical contextualization. It proves that—contrary to common belief—blackface as a regular practice did not start in Poland in the twenty-first century, but has a complex history. In fact, although we have been investigating the history of racialization and exoticization in Poland for a while, we were still astonished by the multiplicity of past instances and their similarity to contemporary performances.

Importing Blackface

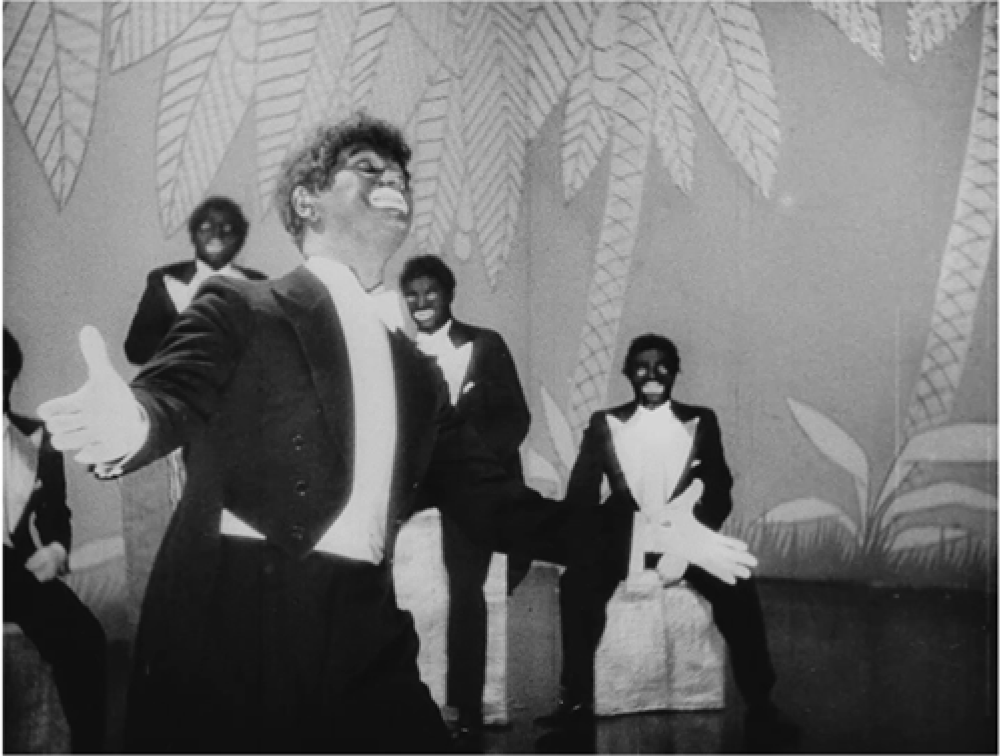

In the climax of the 1934 Polish feature film Kocha, lubi, szanuje (Respects, Likes, Loves, dir. M. Waszyński), the main protagonist, a nouveau-riche owner of a revue theater, played by Eugeniusz Bodo, the biggest male star of interwar Polish cinema, performs in blackface in his own venue. Assisted by a chorus of men in tuxedos and blackface, he sings a song in English, which is unusual for a Polish movie of that time (Fig. 1). The lyrics of Oh Alaska, written by Polish songwriter Bolesław Rajfeld and not free of grammatical mistakes, tell a story of a trip around the world in pursuit of love. Bodo closes the act with a radical change of tone and cries: “Sonny Boy”—a phrase borrowed from none other than Al Jolson.

Figure 1. Film still from Kocha, lubi, szanuje (1934, dir. M. Waszyński). Copyright: Fototeka, Filmoteka Narodowa—Instytut Audiowizualny.

Jolson, once a Warner Brothers’ favorite, had already passed the peak of his popularity in 1934. Yet Universal Studios quoted his act in the company’s first production in Poland.Footnote 12 At the time of the release of Kocha, lubi, szanuje, commentators were hopeful about the influx of American capital.Footnote 13 This transatlantic influence was reflected in the conspicuous use of references to American films that featured exoticism and blackface. Bodo unexpectedly switching to “Sonny Boy” was a reference to The Singing Fool (dir. L. Bacon, 1928, screened in Poland in 1929), as well as The Jazz Singer (dir. A. Crosland, 1927, screened in Poland in 1930). Moreover, Kocha … is based on an extended dream sequence about an escape from the economic crisis, similarly to Roman Scandals (dir. F. Tuttle, 1933, Polish premiere in 1934), featuring Eddie Cantor in blackface. Finally, a different bit in the Polish movie—an “exotic” dance by a female star Loda Halama—bears striking resemblance to Marlene Dietrich’s performance in Blonde Venus (dir. J. von Sternberg, 1932). However, the emphatic use of intertextual references did not grant the movie local or international success.Footnote 14

Sound film—with Singing Fool’s premiere in Warsaw’s Splendid cinema on September 27, 1929 as the first “talkie” shown in Poland—became the principal medium of blackface’s transfer to Poland.Footnote 15 Al Jolson’s blockbusters were among the most popular and influential sound movies circulating in Poland at the time. Other notable productions, featuring white actors in blackface performing a single sketch, include Swing Time (dir. G. Stevens, 1936) and the aforementioned Roman Scandals. Tuttle’s film exemplifies the kind of “accidental blackface,” in which a character unintentionally gets blackened with mud or soot. The “accidental blackface” forms a subtype of the “one scene only” blackface that predominates in the 1930s, as feature films were still heavily influenced by vaudeville and burlesque.Footnote 16 We compiled a list of more than eighty predominantly American feature films and cartoons produced before 1940 that contain blackface. Polish audiences had the opportunity to see around thirty of them between 1918 and 1939, with a typical delay of one to two years.Footnote 17

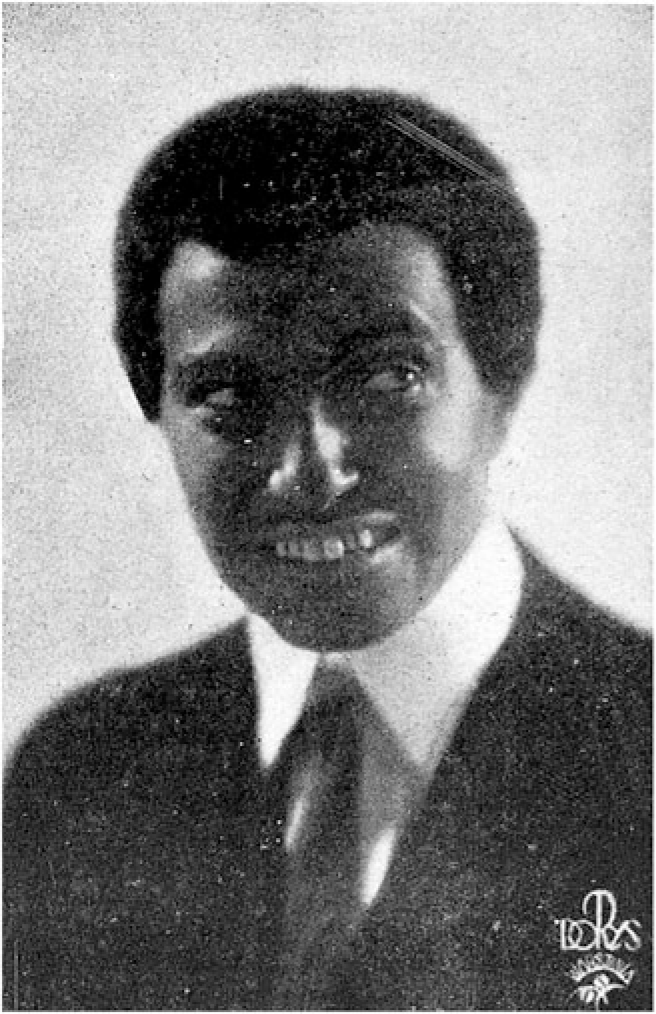

We argue that blackface embedded in movie plots through sudden stage performances was almost immediately brought to Poland and imitated.Footnote 18 It functioned as a novel fashionable formula, a point of reference for local artists, a building block of American cinema which itself constituted “the very symbol of contemporaneity, the present, modern times,” as characterized by Miriam Hansen.Footnote 19 It also influenced artistic forms predating the popularization of sound film. As early as January 1930, soon after the Warsaw premiere of The Singing Fool, a renowned actress, Ida Kamińska, took the lead role in a stage production of The Jazz Singer in Warsaw (Fig. 2).Footnote 20

Figure 2. Promotional photo of Ida Kamińska in theater production of Jazz Singer (Warsaw, 1930). Nasz Przegląd Ilustrowany, dodatek do Naszego Przeglądu, March 23, 1930, 7.

In a book on “exporting blackface minstrelsy,” Chinua Thelwell specifies the phases of globalization of the phenomenon recognized by multiple scholars as “the first popular culture in the United States”Footnote 21 and “the first American mass culture”Footnote 22:

In the first wave, T. D. Rice and several American blackface acts went to London and Canada between 1836 and the 1840s… . The second wave comprised professional American, British, and Australian minstrel troupes who toured several international oceanic circuits from the 1850s to the 1880s. During the third wave, a relatively small number of blackface vaudeville acts traveled abroad from the 1890s to 1915. The fourth wave of blackface imagery was disseminated in Hollywood films, print media advertisements, and American comic book illustrations from 1915 to the 1960s. The last wave, the fifth wave, is best described as a self-aware and ironic form of blackface distributed by American movies and TV shows in the post–civil rights era.Footnote 23

The fourth, Hollywood based wave brought blackface imagery to Poland on a large scale.Footnote 24 It appeared as a fad, initially coupled with the technical invention of the “talkies.” As such, this type of blackface did not last and its imitations exhausted its appeal. And yet, it points to a sense of belonging to the global entertainment industry and the will of local filmmakers to act as active agents on that market. Polish entrepreneurs, like director Michał Waszyński, stayed up to date with the latest trends and engaged in the international cinematic order. Blackface seemed to serve them as a template promising both international attention and local curiosity. Yet, if the historian of popular media Nicholas Sammond is right that blackfacing “has always been a creature of its time, refracting contemporary anxieties about the power and meaning of whiteness through nostalgic fantasies about blackness,” we should take a closer look at cases of blackface in Poland that “translate” it for the specific context of a newly independent country in east-central Europe.Footnote 25

Blackface Without Blackness

If Kocha, lubi, szanuje employs blackface as an imported cinematic module, there are multiple examples of visual representations where blackface can be seen as participating in the more complex set of Polish “colonial fantasies.”Footnote 26 After regaining independence in 1918, Poland went through a period of redefining itself on the global map of what historian Piotr Puchalski calls “the colonial world order.”Footnote 27 For the first time in Polish history, a strong emphasis on the sea—maritime trade, military fleet and “maritime education and upbringing”—became an important propagandist theme, and the establishment of the modern port city Gdynia became a flagship project of modernization.Footnote 28

Around 1930, the economic crisis further accelerated public interest in partly mythical overseas lands promising resources to reinvigorate the struggling state’s economy and land to cultivate by the growing number of unemployed. Actual colonial undertakings and efforts to build international cooperation were relatively minor compared with the popularity of colonial culture. The membership of the Maritime and Colonial League, an organization built to resemble its German counterpart, Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft, exceeded 900,000 in a country of 35 million in the late 1930s. The League organized innumerable local and nationwide events, maritime festivities, parades and exhibitions. Above all, it had multiple widely-read illustrated magazines.Footnote 29

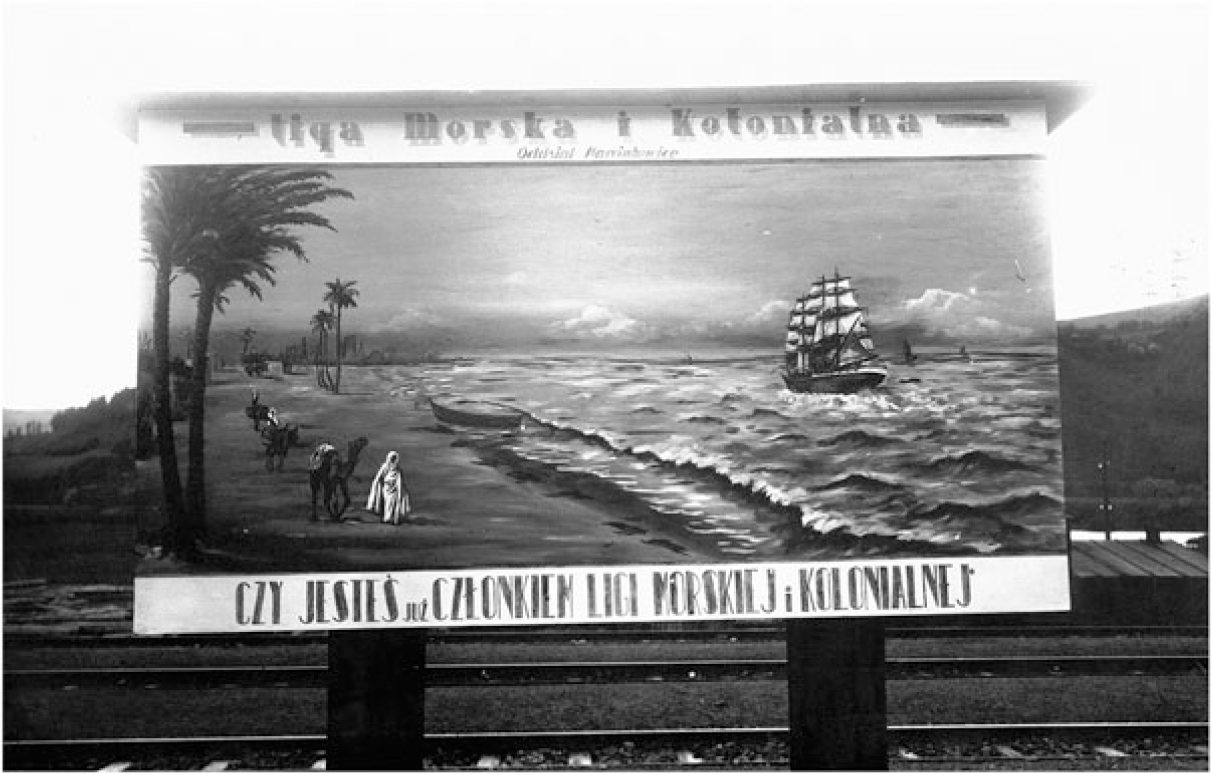

Thus, interest in colonies, accompanied by an outdated wish to join the ranks of colonial empires, coincided with a proliferation of visual media that lured readers with exotic landscapes and intense colors. International “racial” and ethnographic cinema, local “exotic movies,” comic strips, billboards displaying the League’s advertisements (Fig. 3), and illustrated magazines printed by wannabe colonialists, travelers and journalists, all turned colonial fantasies into a mass product manufactured by Polish culture in the 1930s. The gate to this world—a world available to most Poles only through images and literature—lay in the Baltic Sea.

Figure 3. 1936 outdoor advertisement of the Maritime and Colonial League. “Are you a member of the Maritime and Colonial League already?” (photo: National Digital Archive, Poland, open access).

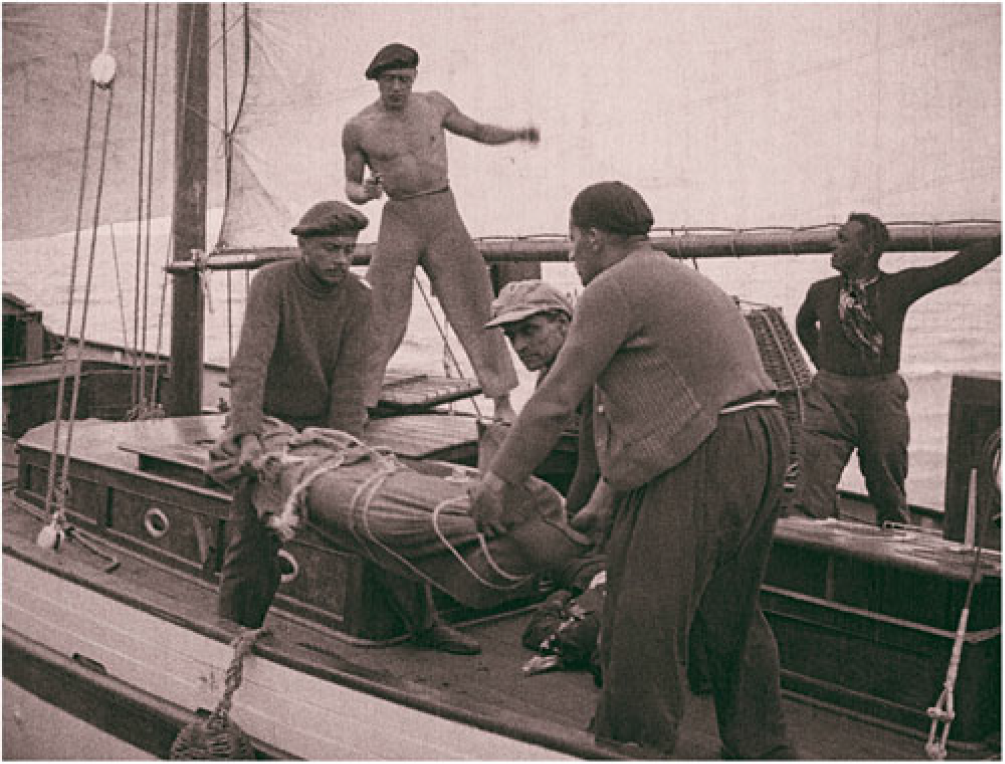

The first Polish maritime blockbuster, the 1927 Zew morza (Call of the Sea, dir. H. Szaro), was filmed with the assistance of the Polish navy. The movie, which promoted a vision of modern “Maritime Poland,” employed blackface to portray a ragtag crew of contemporary sea smugglers turned pirates. Blackface is used here to allow the actor to pass as Black and not be recognized as wearing make-up. The role of the extra is in fact a minor one (Fig. 4): he lingers in the background while white pirates—including a German boatswain, the story’s villain—kidnap the Polish protagonist and steal his priceless engineering blueprints. Thus, the “Black” pirate serves as an almost negligible visual token that embodies the dangerous side of the maritime world. The multiracial crew of pirates conveys ideas of marginality, externality, and threatening diversity that are overcome in the movie’s climax by the newly created Polish fleet with its shining torpedo-boats and hydroplanes. The blackened actor’s minor role is crucial for communicating these ideas—it is the variable that defines the brigand as truly exotic and primitive.Footnote 30

Figure 4. Film still from Zew morza (dir. H. Szaro, 1927). Copyright: Fototeka, Filmoteka Narodowa—Instytut Audiowizualny.

The modern, maritime world, in which Poland had to find its place, was not solely a “colonial world order,” but also a racial order. Due to a very small African diaspora and the infrequent intercontinental relations of the newly created state, the entertainment and culture industries were the principal sources of visions of racial differences. Extremely popular international “ethnographic cinema” and related film genres—from the 1922 Nanook of the North (dir. R. Flaherty) to the 1931 Tabu (dir. F. W. Murnau)—took upon themselves the role of presenting racialized Others. It was a role in which the movie industry in the 1920s and 30s succeeded what Dagnosław Demski and Dominica Czarnecka characterize as “ethnic shows”: “a form of entertainment that involved displaying members of Non-European communities to the public of the Old Continent, which regarded these peoples as ‘exotic’ … that developed on a massive scale in the latter half of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century.”Footnote 31

Still, while in the interwar period the formula of displaying the non-white body converts to a cinematic image, matched by the growing popularity of western black theater and revue performers (like Louis Douglas), other general mode of performing blackness—the formula of mimesis—gains unexpected popularity in Poland.Footnote 32 It transcends the aforementioned transplantation of the American blackface formula to Polish cinema and theater. This second type of blackface is undoubtedly eclectic, sometimes grassroots and makeshift, yet surprisingly common. It is often performed directly in front of a public, without the proxy of visual media and traditional theatrical setting. It is certainly somewhat conscious of its conventionality and sometimes comical in its intentions. Here are some examples: In the summer of 1938, in the Silesian town of Siemianowice, the Maritime and Colonial League organized a show promoting its “Maritime Week.” Four steelworkers, aged seventeen through nineteen, jumped over a fire on a floating raft decorated with palm trees. “Disguised as Negros, with their bodies covered in tar mixed with kerosene and with flammable loincloths on,” the boys caught fire and jumped into the water to save their lives.Footnote 33 One of them, Bolesław Dulewski, could not swim and suffered deadly burns (which is the reason why the case is mentioned in the press at all).

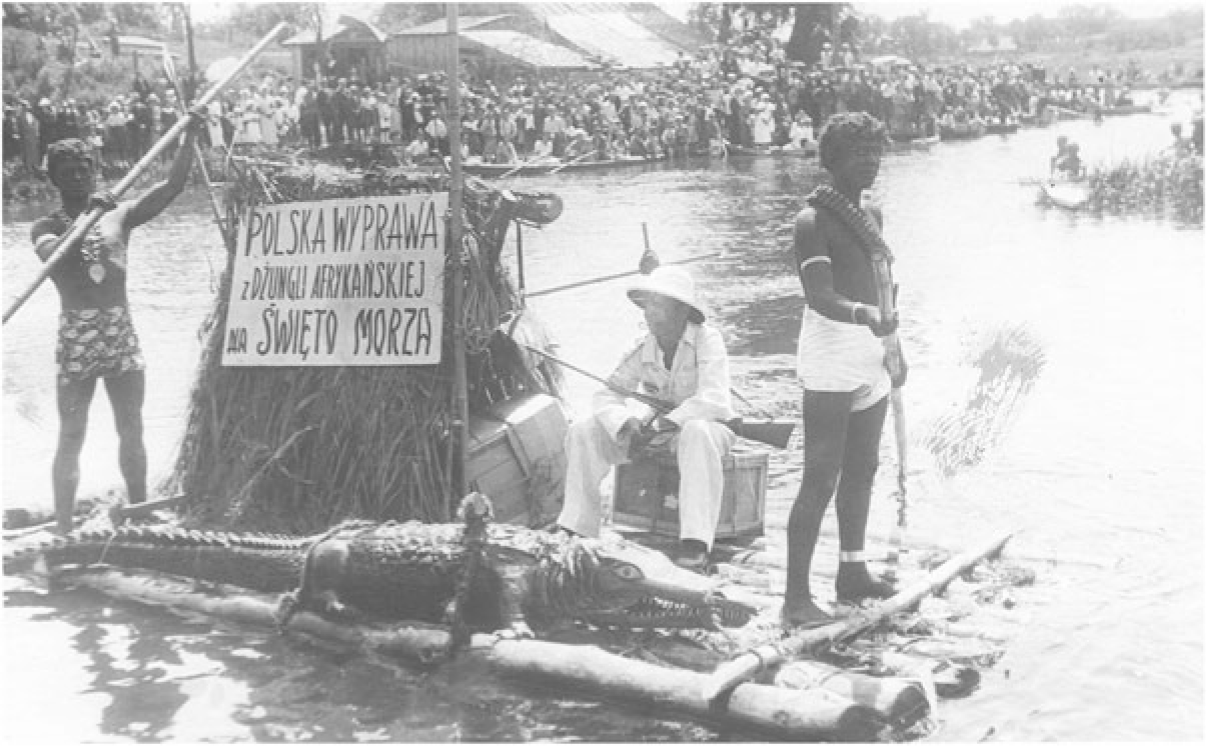

A similar performance, but with no tragic outcome, took place in Gdynia two years earlier. According to the magazine Morze (The Sea), a whole “exotic palm tree island swam onto the offshore [stage] with a fire on it—a fire, in which a white captive was being tortured by black savages.”Footnote 34 The performance was one of the sensations of the state-organized Marine Days. Almost at the same time, 500 km southeast in the marshes of the town of Włodzimierz (today’s Ukraine), men on rafts, wearing wigs and full body make-up, pretended to be members of a “Polish expedition from the African jungle to the Marine Days” (Fig. 5). The racial hierarchy was performed explicitly as the leading raft carried a white man, dressed in colonialist attire including a characteristic Pith helmet, sitting down and holding a rifle on his lap.

Figure 5. Marine Day Celebrations in Włodzimierz, 1936 (photo: National Digital Archive, Poland, open access).

Similar motifs of exoticism can be found in a wider Maritime and Colonial League’s aesthetic framework: cardboard palm trees or potted plants, primitive huts and rafts, papier-mâché figures of fantastic animals, and cartoonish representations of Sub-Saharan Africans climbing trees (Fig. 6). This visual primitivism—hard to reconcile with often up to date information conveyed in some of the League’s publications—exposes the impossible anachronistic dream of becoming a real colonial empire. It was a vision supported by the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, an institution that dreamt of its own missions. In general, it was a dream about what anthropology recognizes as “a myth of first contact,” a fantasy of simple, clear-cut racial relations and hierarchies.Footnote 35 Simultaneously, it is a dream about escaping modernity straight to an exotic, palm-tree lined island (an escape paradoxically made possible by the modern maritime-colonial world).

Figure 6. 1938 parade of the Maritime and Colonial League (photo: National Digital Archive, Poland, open access).

The usurped blackness analyzed through the scope of blackface technique’s application in the discussed period in Poland seems always twofold: radically modern and essentially primitive. In fact, if we look closer, these modes intertwine constantly. The theater manager’s performance in blackface with a blackfaced choir of tuxedoed men in Kocha, lubi, szanuje takes place against a backdrop of painted palm trees. The League’s parade repertoire involved not only Black “primitives,” but also a modern figure of a “Black soldier”: a man from Inowrocław wearing black gloves, black paint on his face, and a classic Polish military uniform.Footnote 36

The image of blackness produced by blackface performances in interwar Poland reconciles two radically disjointed temporal orders. As a result of a hasty attempt to make up for lost time, it neutralizes the contradiction between modernity and primitivism, refinement and savagery. It inscribes them all on the Black body at a decisive time for defining racial differences and internalizing the global racial order by Polish society.

Sounds Familiar

The end of 1930s brought the premiere of the film Strachy (Fears, dir. E. Cękalski, K. Szołowski, 1938), based on a popular novel by Maria Ukniewska. At first sight, the use of blackface in the movie seems analogous to colonial and maritime celebrations: it sets up a background for action and adds exotic ornamentation. However, the movie is everything but straightforward. It gives a socially engaged and moving record of the ill fate of young women dancers in the framework of a lighthearted romance genre. Exploitation, poverty, misogyny in the workplace and at home constitute everyday conditions for working class women forced to create visibly enthusiastic shows. The women perform three distinct dance routines: a type of ballet mécanique; a naval seamen routine; and a supposedly indigenous African dance in full body black makeup (Fig. 7).Footnote 37

Figure 7. Promotional photo for the movie Strachy (dir. E. Cękalski, K. Szołowski, 1938). Copyright: Fototeka, Filmoteka Narodowa—Instytut Audiowizualny.

The way blackface is implemented in Strachy comes close to what scholars recognized in selected cases of blackface minstrelsy as radical social commentary.Footnote 38 First, blackface is a part of a juxtaposition of staged worlds and the real world behind the scenes; in the words of William J. Mahar: “what society promised and what it actually delivered.”Footnote 39 Secondly, the use of blackface allows for the introduction of topics difficult to discuss openly.Footnote 40 In this case it is entangled in a political statement about the condition of the working class in Poland: a statement dangerous to express explicitly in a country with active censorship and strong policies curtailing left-wing political activity, and certainly a risky statement to convey through cinematic representations of working class men, dangerous as a revolutionary force. Last but not least, Strachy conducts an even more complex critique of Polish modernity through its internal spectacles. The movie recognizes the clinch of a working-class body between the everyday struggles and possibilities offered by the public discourse of the time: maritime discipline and nationalism; anachronistic colonial fantasies, promising an impossible escape; and regimes of industrial factories forming bodies into what Siegfried Kracauer in a strikingly similar context called “mass ornament.”Footnote 41

Ultimately blackness once again serves merely as a node in an argument, a token, a signifier with a vague and imaginary reference, a building block of a metaphor, playing its role in someone else’s story. While the movie to a certain degree successfully builds a realistic and politically engaging argumentation, it ultimately engages in stereotypes, reifying figures and visual sensationalism (Fig. 8). It focuses on exposing bodies: blackened bodies but also bodies of young white working class women, and thus reaffirms the cultural status quo, both racist and patriarchal.Footnote 42

Figure 8. Promotional photo for the movie Strachy (dir. E. Cękalski, K. Szołowski, 1938). Copyright: Fototeka, Filmoteka Narodowa—Instytut Audiowizualny.

That certainly is not the only analogy between the ambitious 1938 movie and the twenty-first century television format. Similarly to the historical practice, Twoja Twarz Brzmi Znajomo exercises the formula of a makeover, allowing viewers to witness the process of putting on the makeup, promising to take us behind the scenes to witness stars in the making. Its scenic performances are exactly one time routines. The performers appropriate someone’s identity to momentarily abandon all its determinants after the last tone of the song. The identity is defined by strong one-dimensional features, but most importantly by performance of the bodily capabilities. Thus, the show itself constructs a perfect setup for what Catherine Baker, following Lisa Nakamura, called “spectacles of race.”Footnote 43 In a country where ethnic minorities and citizens not regarded as white are certainly underrepresented in the public sphere, Twoja Twarz Brzmi Znajomo put blackness in a secure slot of an entertainment show, where literally no one speaks their own voice. As such, it continued the local tradition—whose existence we have tried to prove—of usurping blackness as if a Black person was primarily a fantasy or, as Saidiya Hartman famously wrote, “a vessel for the uses, thoughts, whims, and feelings of others.”Footnote 44

Łukasz Zaremba is Assistant Professor in Visual Studies at the Institute of Polish Culture, University of Warsaw; independent curator, author of multiple publications on image theory, conflict in visual culture, and contemporary iconoclasm and monuments. He is currently developing a research project entitled “Colonial Complex: Visual Culture and Colonialism without Colonies in the Interwar Poland,” financed by the Polish National Science Centre. Under the label “Colonial Complex,” he investigates the role of visual culture in imperial fantasies and the racialized ways of seeing in Poland.

Maciej Duklewski is a PhD candidate in History and Art History at the Interdisciplinary Doctoral School, University of Warsaw. He is currently investigating the history of worker photography, cultural politics, and left-wing aesthetic theory in twentieth century Poland. He is a co-investigator in the research project “Colonial Complex: Visual Culture and Colonialism without Colonies” financed by Polish National Science Centre.