1. Introduction

Consider the existence and stability of solitary wave solutions of

where ![]() $5 \leq p\in\mathbb{N}$ and

$5 \leq p\in\mathbb{N}$ and ![]() $\mathcal{H}$ is the Hilbert transform. Equation (1.1) is a generalized version of the Benjamin equation [Reference Benjamin7, Reference Benjamin8]

$\mathcal{H}$ is the Hilbert transform. Equation (1.1) is a generalized version of the Benjamin equation [Reference Benjamin7, Reference Benjamin8]

which describes the unidirectional propagation of internal waves and governs approximately the evolution of waves on the interface of a two-fluid system, where the lower fluid with greater density is deep, and the surface effect is not negligible. Here, the waves can propagate along the interface between two fluids [Reference Albert, Bona and Restrepo1] because of the density difference.

Equation (1.1) has attracted considerable attention in the past decades, see [Reference Albert, Bona and Restrepo1, Reference Albert and Linares3, Reference Amick and Toland6, Reference Bona and Chen9, Reference Bona, Souganidis and Strauss14, Reference Chen and Bona16, Reference Pava32, Reference Pava33]. It has the solitary wave solution of the form

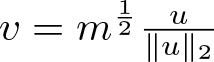

where ![]() $c \gt 0$ is the dimensionless wave speed and both

$c \gt 0$ is the dimensionless wave speed and both ![]() $u(\xi)$ and its derivatives tend to zero as the variable

$u(\xi)$ and its derivatives tend to zero as the variable ![]() $\xi$ approaches

$\xi$ approaches ![]() $\pm\infty$. By substitution of (1.2) into (1.1) and integration once, we have

$\pm\infty$. By substitution of (1.2) into (1.1) and integration once, we have

whose action functional is given by

where the corresponding energy ![]() $E(u)$ is defined by

$E(u)$ is defined by

\begin{equation*}

E(u)=\int_{\mathbb{R}}\big[(u^{\prime})^2-2u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}-\frac{2}{p+1}u^{p+1}\big]dx.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

E(u)=\int_{\mathbb{R}}\big[(u^{\prime})^2-2u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}-\frac{2}{p+1}u^{p+1}\big]dx.

\end{equation*} By the Sobolev embedding theorem, ![]() $E(u)$ is a continuous function from

$E(u)$ is a continuous function from ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$ to

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$ to ![]() $\mathbb{R}$. One of interesting and important problems on equation (1.1) is the stability of solitary waves in

$\mathbb{R}$. One of interesting and important problems on equation (1.1) is the stability of solitary waves in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$, which is defined by

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$, which is defined by

Definition 1.1. We say that the set ![]() $G\subset X$ is stable, if for every

$G\subset X$ is stable, if for every ![]() $\epsilon \gt 0$ there exists

$\epsilon \gt 0$ there exists ![]() $\delta \gt 0$ such that for every initial data

$\delta \gt 0$ such that for every initial data ![]() $\phi_0$ satisfying

$\phi_0$ satisfying

\begin{equation*}

\inf_{g\in G}\|\phi_0-g\|_{X} \lt \delta,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\inf_{g\in G}\|\phi_0-g\|_{X} \lt \delta,

\end{equation*} then the solution ![]() $\phi(x,t)$ of equation (1.1) with

$\phi(x,t)$ of equation (1.1) with ![]() $\phi(x,0)=\phi_0$ satisfies

$\phi(x,0)=\phi_0$ satisfies

\begin{equation*}

\inf_{g\in G}\|\phi(\cdot,t)-g\|_{X} \lt \epsilon,~~t\in\mathbb{R}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\inf_{g\in G}\|\phi(\cdot,t)-g\|_{X} \lt \epsilon,~~t\in\mathbb{R}.

\end{equation*} Otherwise, we say that the set ![]() $G$ is unstable.

$G$ is unstable.

Quite a few powerful methods were proposed for studying the orbital stability of solitary waves in the past decades. For example, the stability/instability criterion was introduced by Grillakis–Shatah–Strauss (GSS) [Reference Grillakis, Shatah and Strauss20, Reference Grillakis, Shatah and Strauss21]. It usually needs to show that the solitary wave solution is a local constrained minimizer of a Hamiltonian functional, which can be undertaken by means of spectral properties of a linear operator derived from the solitary wave equation. The method developed by Cazenave-Lions [Reference Cazenave and Lions15] is associated with the constrained variational problem and the global minimization problem, based on the conservation laws of mass and energy and the compactness of any minimizing sequences. Both methods are widely used in various dispersive evolution equations, see [Reference Albert, Bona and Saut2, Reference Albert and Pava4, Reference Albert and Toland5, Reference Bona and Li10, Reference Bonheure, Casteras, Gou and Jeanjean11, Reference Bonheure, Casteras, Moreira dos Santos and Nascimento12, Reference Jeanjean, Jendrej, Le and Visciglia22, Reference Kichenassamy23, Reference Li and Bona24, Reference Lions26–Reference Lopes30, Reference Pava32, Reference Pava34].

For equation (1.1), there is no scale invariance and it contains the singular integral term ![]() $\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}$ which makes the uniqueness of the solution be still an open problem, see [Reference Frank and Lenzmann18, Reference Frank, Lenzmann and Silvestre19]. To apply the Cazenave–Lions method, we shall consider a corresponding minimization problem

$\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}$ which makes the uniqueness of the solution be still an open problem, see [Reference Frank and Lenzmann18, Reference Frank, Lenzmann and Silvestre19]. To apply the Cazenave–Lions method, we shall consider a corresponding minimization problem

\begin{equation}

I(m)=\inf\Big\{E(u):u\in S_m\Big\},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

I(m)=\inf\Big\{E(u):u\in S_m\Big\},

\end{equation}where

\begin{equation*}

S_m:=\big\{u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})~\big|~F(u):=\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^2dx=m\big\}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

S_m:=\big\{u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})~\big|~F(u):=\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^2dx=m\big\}.

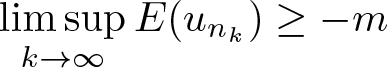

\end{equation*} Since ![]() $I(m) \lt -m$, it is difficult to prove the non-vanishing of any minimizing sequence by the concentration-compactness principle. To tackle this problem, under the assumption of the sufficiently small

$I(m) \lt -m$, it is difficult to prove the non-vanishing of any minimizing sequence by the concentration-compactness principle. To tackle this problem, under the assumption of the sufficiently small ![]() $m$, Angulo [Reference Pava32] applied a skilful auxiliary function to establish the compactness of any minimizing sequence when

$m$, Angulo [Reference Pava32] applied a skilful auxiliary function to establish the compactness of any minimizing sequence when ![]() $2\leq p \lt 5$, which implies that the set of minimizers is orbitally stable. When

$2\leq p \lt 5$, which implies that the set of minimizers is orbitally stable. When ![]() $p \gt 5$, the instability of solitary wave solutions for (1.1) was explored in [Reference Pava33]. From the variational perspective, the energy functional

$p \gt 5$, the instability of solitary wave solutions for (1.1) was explored in [Reference Pava33]. From the variational perspective, the energy functional ![]() $E$ has a geometry of local minima under the mass constraint when

$E$ has a geometry of local minima under the mass constraint when ![]() $p \gt 5$. However, it is natural to ask whether there exist stable solitary waves when

$p \gt 5$. However, it is natural to ask whether there exist stable solitary waves when ![]() $p \gt 5$ and

$p \gt 5$ and ![]() $p=5$. The goal of this study is to answer this question.

$p=5$. The goal of this study is to answer this question.

In order to present our discussions in a straightforward manner, let us summarize our main results here.

Theorem 1.2 When ![]() $p=5$, there exists

$p=5$, there exists ![]() $m_0 \lt k_*$ such that when

$m_0 \lt k_*$ such that when ![]() $m\in(m_0,k_*)$, for any sequence

$m\in(m_0,k_*)$, for any sequence ![]() $\{u_n\}\subset H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying

$\{u_n\}\subset H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying ![]() $F(u_n)\to m$ and

$F(u_n)\to m$ and ![]() $E(u_n)\to I(m)$, there are a subsequence, still denoted by

$E(u_n)\to I(m)$, there are a subsequence, still denoted by ![]() $\{u_n\}$, a sequence of points

$\{u_n\}$, a sequence of points ![]() $\{x_n\}\subset \mathbb{R}$ and a function

$\{x_n\}\subset \mathbb{R}$ and a function ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ such that

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ such that ![]() $u_n(\cdot+x_n)\to u$ strongly in

$u_n(\cdot+x_n)\to u$ strongly in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$, where

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$, where ![]() $k_*$ is given by (3.5). In particular, there exists a solution

$k_*$ is given by (3.5). In particular, there exists a solution ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ to the minimization problem (1.3).

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ to the minimization problem (1.3).

Denote the set of the minimizers for ![]() $I(m)$ by

$I(m)$ by

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal{G}_m:=\Big\{u\in H^1(\mathbb{R}):F(u)=m~{\rm{and}}~E(u)=I(m)\Big\}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal{G}_m:=\Big\{u\in H^1(\mathbb{R}):F(u)=m~{\rm{and}}~E(u)=I(m)\Big\}.

\end{equation*} From Theorem 1.2, it follows that the set ![]() $\mathcal{G}_m$ is not empty.

$\mathcal{G}_m$ is not empty.

Theorem 1.3 When ![]() $p=5$, the set

$p=5$, the set ![]() $\mathcal{G}_m$ is orbitally stable for all

$\mathcal{G}_m$ is orbitally stable for all ![]() $m\in(m_0,k_*)$, where

$m\in(m_0,k_*)$, where ![]() $m_0$ and

$m_0$ and ![]() $k_*$ are the same as given in Theorem 1.2.

$k_*$ are the same as given in Theorem 1.2.

When ![]() $p \gt 5$, we see that

$p \gt 5$, we see that ![]() $I(m)=-\infty$ for any

$I(m)=-\infty$ for any ![]() $m \gt 0$. So, the minimization problem (1.3) becomes trivial. According to the geometry of local minima under the mass constraint, we can find an open set

$m \gt 0$. So, the minimization problem (1.3) becomes trivial. According to the geometry of local minima under the mass constraint, we can find an open set ![]() $\mathcal{O}\subset H^1(\mathbb{R})$ (see (4.6)) such that any possible local minimizer of

$\mathcal{O}\subset H^1(\mathbb{R})$ (see (4.6)) such that any possible local minimizer of ![]() $E$ under the mass constraint must belong to

$E$ under the mass constraint must belong to ![]() $\mathcal{O}$. To study the orbital stability of solitary wave solutions for

$\mathcal{O}$. To study the orbital stability of solitary wave solutions for ![]() $p \gt 5$, we shall consider the local minimization problem

$p \gt 5$, we shall consider the local minimization problem

Theorem 1.4 When ![]() $p \gt 5$, the following three assertions are true.

$p \gt 5$, the following three assertions are true.

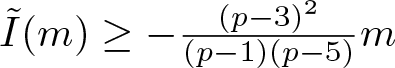

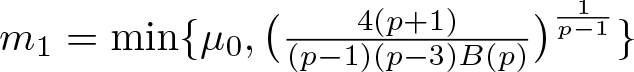

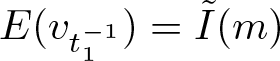

(i) There exists ![]() $m_0 \gt 0$ such that

$m_0 \gt 0$ such that ![]() $\tilde{I}(m)=-m$ for any

$\tilde{I}(m)=-m$ for any ![]() $m\in(0,m_0]$ and the infimum

$m\in(0,m_0]$ and the infimum ![]() $\tilde{I}(m)$ is not achieved for any

$\tilde{I}(m)$ is not achieved for any ![]() $m\in(0,m_0)$.

$m\in(0,m_0)$.

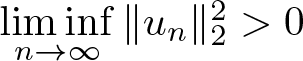

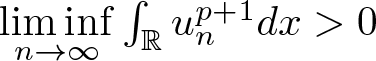

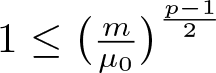

(ii) There exist ![]() $\tilde{m}_0$ and

$\tilde{m}_0$ and ![]() $\mu_0$ such that for all

$\mu_0$ such that for all ![]() $m\in(\tilde{m}_0,\mu_0)$, any minimizing sequence

$m\in(\tilde{m}_0,\mu_0)$, any minimizing sequence ![]() $\{u_n\}$ for

$\{u_n\}$ for ![]() $\tilde{I}(m)$ has a subsequence

$\tilde{I}(m)$ has a subsequence ![]() $\{u_{n_k}\}$, which converges to

$\{u_{n_k}\}$, which converges to ![]() $u$ strongly in

$u$ strongly in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$. Then,

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$. Then, ![]() $\|u\|_2^2=m$ and

$\|u\|_2^2=m$ and ![]() $E(u)=\tilde{I}(m)$.

$E(u)=\tilde{I}(m)$.

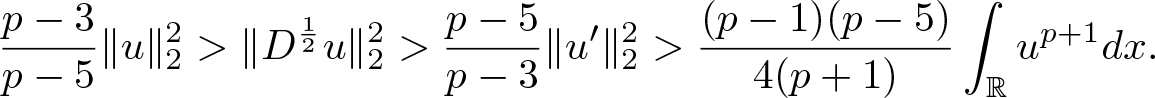

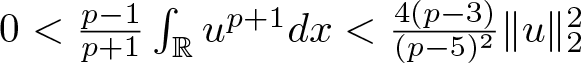

(iii) Any minimizer of ![]() $\tilde{I}(m)$ which solves

$\tilde{I}(m)$ which solves

satisfies

\begin{equation*}

0 \lt \omega \lt -1+\frac{(p-3)^2}{(p-1)(p-5)}+\frac{4(p-3)}{(p-5)^2}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

0 \lt \omega \lt -1+\frac{(p-3)^2}{(p-1)(p-5)}+\frac{4(p-3)}{(p-5)^2}.

\end{equation*} For ![]() $p \gt 5$, we denote

$p \gt 5$, we denote

From Theorem 1.4, we know that the set ![]() $\tilde{\mathcal{G}}_m$ is not empty.

$\tilde{\mathcal{G}}_m$ is not empty.

Theorem 1.5 When ![]() $p \gt 5$, the set

$p \gt 5$, the set ![]() $\tilde{\mathcal{G}}_m$ is orbitally stable for all

$\tilde{\mathcal{G}}_m$ is orbitally stable for all ![]() $m\in(\tilde{m}_0, \mu_0)$, where

$m\in(\tilde{m}_0, \mu_0)$, where ![]() $\tilde{m}_0$ and

$\tilde{m}_0$ and ![]() $\mu_0$ are the same as given in Theorem 1.4.

$\mu_0$ are the same as given in Theorem 1.4.

Throughout this article, we denote the Fourier transform by  $\mathcal{F}(u)(\xi)=\hat{u}(\xi)=\int_{\mathbb{R}}e^{-ix\cdot \xi}u(x)dx$ if

$\mathcal{F}(u)(\xi)=\hat{u}(\xi)=\int_{\mathbb{R}}e^{-ix\cdot \xi}u(x)dx$ if ![]() $u\in L^1(\mathbb{R})$. As usual, we extend it to tempered distributions, and introduce the Fourier integral operator

$u\in L^1(\mathbb{R})$. As usual, we extend it to tempered distributions, and introduce the Fourier integral operator ![]() $|D|-1$ defined by

$|D|-1$ defined by ![]() $(|D|-1)u=\mathcal{F}^{-1}((|\cdot|-1)\hat{u})$. Given a tempered distribution

$(|D|-1)u=\mathcal{F}^{-1}((|\cdot|-1)\hat{u})$. Given a tempered distribution ![]() $u$, we see that

$u$, we see that ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ if and only if

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ if and only if ![]() $\hat{u}\in L^2(\mathbb{R})$ and

$\hat{u}\in L^2(\mathbb{R})$ and ![]() $(|\cdot|-1)\hat{u}\in L^2(\mathbb{R})$. We denote by

$(|\cdot|-1)\hat{u}\in L^2(\mathbb{R})$. We denote by ![]() $\|\cdot\|_p$ the standard norm on

$\|\cdot\|_p$ the standard norm on ![]() $L^p(\mathbb{R})$.

$L^p(\mathbb{R})$.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We present several technical lemmas in Section 2. We consider the minimization problem (1.3) and prove Theorems 1.2 and 1.3 in Section 3. We investigate the problem of minimizing the energy with the ![]() $L^2$-norm in the set

$L^2$-norm in the set ![]() $\mathcal{O}$ when

$\mathcal{O}$ when ![]() $p \gt 5$ and then prove Theorems 1.4 and 1.5 in Section 4.

$p \gt 5$ and then prove Theorems 1.4 and 1.5 in Section 4.

2. Several lemmas

In order to make the paper sufficiently self-contained, let us recall the local well-posedness of the Cauchy problem to (1.1) and Gagliardo–Nirenberg type inequalities for fractional derivatives.

Lemma 2.1. ([Reference Pava33, Theorem 2.1]) Let ![]() $p\in \mathbb{N}$ and

$p\in \mathbb{N}$ and ![]() $p\geq2$. For

$p\geq2$. For ![]() $u_0\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ there exists

$u_0\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ there exists ![]() $T=

T(\|u_0\|_{H^1}) \gt 0$ and a unique solution

$T=

T(\|u_0\|_{H^1}) \gt 0$ and a unique solution ![]() $u(t)\equiv U(t)u_0\in C([0,T); H^1(\mathbb{R}))$ of (1.1) with

$u(t)\equiv U(t)u_0\in C([0,T); H^1(\mathbb{R}))$ of (1.1) with ![]() $u(x,0)=u_0(x)$. For

$u(x,0)=u_0(x)$. For ![]() $T \gt 0$ the map

$T \gt 0$ the map ![]() $u_0\to U(t)u_0$ is Lipschitz continuous from

$u_0\to U(t)u_0$ is Lipschitz continuous from ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$ to

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$ to ![]() $C([0,T); H^1(\mathbb{R}))$. In addition,

$C([0,T); H^1(\mathbb{R}))$. In addition, ![]() $T=+\infty$ if we have

$T=+\infty$ if we have

(i) for ![]() $2\leq p \lt 5$,

$2\leq p \lt 5$, ![]() $u_0\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ and no restriction on the data is needed;

$u_0\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ and no restriction on the data is needed;

(ii) for ![]() $p=5$,

$p=5$, ![]() $\|u_0\|_2$ has to be not too large; and

$\|u_0\|_2$ has to be not too large; and

(iii) for ![]() $p \gt 5$,

$p \gt 5$, ![]() $\|u_0\|_{H^1}$ is small.

$\|u_0\|_{H^1}$ is small.

Lemma 2.2. ([Reference Brézis and Lieb13, Theorem 1])

Let ![]() $0 \lt p \lt \infty$. Suppose that

$0 \lt p \lt \infty$. Suppose that ![]() $f_n\to f$ almost everywhere and

$f_n\to f$ almost everywhere and ![]() $\{f_n\}$ is a bounded sequence in

$\{f_n\}$ is a bounded sequence in ![]() $L^p(\mathbb{R})$. Then

$L^p(\mathbb{R})$. Then  $\lim\limits_{n\to\infty}(\|f_n\|_p^p-\|f_n-f\|_p^p-\|f\|_p^p)=0$.

$\lim\limits_{n\to\infty}(\|f_n\|_p^p-\|f_n-f\|_p^p-\|f\|_p^p)=0$.

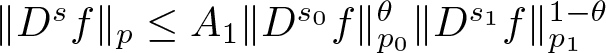

Lemma 2.3. ([Reference Pava32, Lemma 2.1])

If ![]() $f\in S(\mathbb{R})$, then

$f\in S(\mathbb{R})$, then  $

\|D^sf\|_{p}\leq A_1\|D^{s_0}f\|_{p_0}^\theta\|D^{s_1}f\|_{p_1}^{1-\theta}

$ holds, where

$

\|D^sf\|_{p}\leq A_1\|D^{s_0}f\|_{p_0}^\theta\|D^{s_1}f\|_{p_1}^{1-\theta}

$ holds, where ![]() $p_0,\,p_1\in(1,\infty)$,

$p_0,\,p_1\in(1,\infty)$, ![]() $s_0,\,s_1\in[0,\infty)$,

$s_0,\,s_1\in[0,\infty)$, ![]() $s=\theta s_0+(1-\theta)s_1$, and

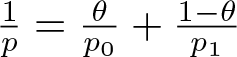

$s=\theta s_0+(1-\theta)s_1$, and  $\frac{1}{p}=\frac{\theta}{p_0}+\frac{1-\theta}{p_1}$, and

$\frac{1}{p}=\frac{\theta}{p_0}+\frac{1-\theta}{p_1}$, and ![]() $S(\mathbb{R})$ is the Schwartz space.

$S(\mathbb{R})$ is the Schwartz space.

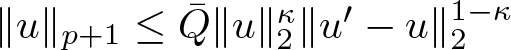

Lemma 2.4. ([Reference Ferndez, Jeanjean, Mandel and Maris17, Theorem 1.1])

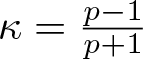

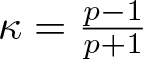

If ![]() $p\in(1,\infty)$ and

$p\in(1,\infty)$ and ![]() $\kappa\in(0,1)$, then

$\kappa\in(0,1)$, then  $

\|u\|_{p+1}\leq \bar{Q}\|u\|_2^{\kappa}\|u^{\prime}-u\|_2^{1-\kappa}

$ holds for any

$

\|u\|_{p+1}\leq \bar{Q}\|u\|_2^{\kappa}\|u^{\prime}-u\|_2^{1-\kappa}

$ holds for any ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ if and only if

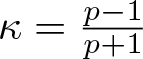

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ if and only if ![]() $p=5$, where

$p=5$, where  $\kappa=\frac{p-1}{p+1}$ and the best constant

$\kappa=\frac{p-1}{p+1}$ and the best constant ![]() $\bar{Q}$ is defined in (3.13).

$\bar{Q}$ is defined in (3.13).

From Lemma 2.4, we can derive the following corollary immediately.

Corollary 2.5. The supremum ![]() $

\sup\{Q_\kappa(u)~|~u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\setminus\{0\}~{\rm{and}}~\|(|D|-1)u\|_2\leq R\|u\|_2\}

$ is finite for any fixed

$

\sup\{Q_\kappa(u)~|~u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\setminus\{0\}~{\rm{and}}~\|(|D|-1)u\|_2\leq R\|u\|_2\}

$ is finite for any fixed ![]() $R \gt 0$ if

$R \gt 0$ if

\begin{equation}

\kappa\geq\frac{1}{2}~~{\rm{and}}~~1-\kappa\leq\frac{1}{2}-\frac{1}{p+1},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\kappa\geq\frac{1}{2}~~{\rm{and}}~~1-\kappa\leq\frac{1}{2}-\frac{1}{p+1},

\end{equation} where ![]() $Q_\kappa(u)$ is defined in (3.13).

$Q_\kappa(u)$ is defined in (3.13).

3. Global minimization of the energy with  $L^2$-norm

$L^2$-norm

In this section, we consider the minimization problem (1.3) and the orbital stability of solitary wave solutions for (1.1). For any function ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ and any

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ and any ![]() $a,\,b \gt 0$, setting

$a,\,b \gt 0$, setting ![]() $u_{a,b}(x)=au(\frac{x}{b})$, we get

$u_{a,b}(x)=au(\frac{x}{b})$, we get

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&\|u^{\prime}_{a,b}\|_2^2=a^2b^{-1}\|u^{\prime}\|^2_2,~~~

\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u_{a,b}\|_2^2=a^2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2,\\

&\|u_{a,b}\|_2^2=a^2b\|u\|^2_2,~~~

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}_{a,b}dx=a^{p+1}b\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&\|u^{\prime}_{a,b}\|_2^2=a^2b^{-1}\|u^{\prime}\|^2_2,~~~

\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u_{a,b}\|_2^2=a^2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2,\\

&\|u_{a,b}\|_2^2=a^2b\|u\|^2_2,~~~

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}_{a,b}dx=a^{p+1}b\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}Using Plancherel’s Theorem yields

\begin{align*}

\|u\|^2_2&=\frac{1}{2\pi}\|\hat{u}\|^2_2,~~~

\|(|D|-1)u\|^2_2=\frac{1}{2\pi}\|(|\cdot|-1)\hat{u}\|^2_2,\\

\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2&=\frac{1}{2\pi}\||\xi|\hat{u}\|_2^2

=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\xi|^2|\hat{u}|^2d\xi.

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\|u\|^2_2&=\frac{1}{2\pi}\|\hat{u}\|^2_2,~~~

\|(|D|-1)u\|^2_2=\frac{1}{2\pi}\|(|\cdot|-1)\hat{u}\|^2_2,\\

\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2&=\frac{1}{2\pi}\||\xi|\hat{u}\|_2^2

=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\xi|^2|\hat{u}|^2d\xi.

\end{align*}From Lemma 2.3 it follows that

\begin{equation}

\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2\leq\|u^{\prime}\|_2\|u\|_2.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2\leq\|u^{\prime}\|_2\|u\|_2.

\end{equation} The strict inequality in (3.2) holds except for ![]() $u=0$.

$u=0$.

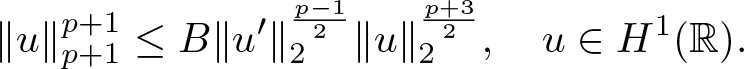

For any ![]() $p\geq2$, we have the Gagliardo–Nirenberg–Sobolev inequality [Reference Nirenberg31]

$p\geq2$, we have the Gagliardo–Nirenberg–Sobolev inequality [Reference Nirenberg31]

\begin{equation}

\|u\|_{p+1}^{p+1}\leq B\|u^{\prime}\|_2^{\frac{p-1}{2}}\|u\|_2^{\frac{p+3}{2}},~~~u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}}).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\|u\|_{p+1}^{p+1}\leq B\|u^{\prime}\|_2^{\frac{p-1}{2}}\|u\|_2^{\frac{p+3}{2}},~~~u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}}).

\end{equation} We denote the best constant ![]() $B$ in (3.3) by

$B$ in (3.3) by

\begin{equation}

B(p)=\sup_{u\in{H^1({\mathbb{R}})}\setminus\{0\}}\frac{\|u\|_{p+1}^{p+1}}

{\|u^{\prime}\|_2^{\frac{p-1}{2}}\|u\|_2^{\frac{p+3}{2}}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

B(p)=\sup_{u\in{H^1({\mathbb{R}})}\setminus\{0\}}\frac{\|u\|_{p+1}^{p+1}}

{\|u^{\prime}\|_2^{\frac{p-1}{2}}\|u\|_2^{\frac{p+3}{2}}}.

\end{equation} For ![]() $I(m)$ defined by (1.3), we have the following properties.

$I(m)$ defined by (1.3), we have the following properties.

Proposition 3.1. (i) If ![]() $p \gt 5$, we have

$p \gt 5$, we have ![]() $I(m)=-\infty$ for all

$I(m)=-\infty$ for all ![]() $m \gt 0$.

$m \gt 0$.

When ![]() $p=5$, the following statements are true.

$p=5$, the following statements are true.

(ii) The function ![]() $I(m)$ is concave on

$I(m)$ is concave on ![]() $(0,\infty)$.

$(0,\infty)$.

(iii) For any ![]() $m \gt 0$, we have

$m \gt 0$, we have ![]() $I(m)\leq-m$.

$I(m)\leq-m$.

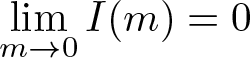

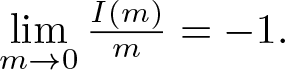

(iv)  $\lim\limits_{m\to0}I(m)=0$ and

$\lim\limits_{m\to0}I(m)=0$ and  $\lim\limits_{m\to0}\frac{I(m)}{m}=-1.$

$\lim\limits_{m\to0}\frac{I(m)}{m}=-1.$

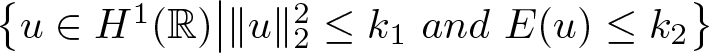

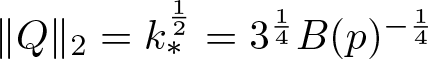

(v) Let ![]() $B(p)$ be given as in (3.4) and

$B(p)$ be given as in (3.4) and

\begin{equation}

k_*=3^{\frac{1}{2}}

B(p)^{-{\frac{1}{2}}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

k_*=3^{\frac{1}{2}}

B(p)^{-{\frac{1}{2}}}.

\end{equation} Then ![]() $I(m)$ is finite for any

$I(m)$ is finite for any ![]() $m\in(0,k_*)$ and

$m\in(0,k_*)$ and ![]() $I(m)=-\infty$ if

$I(m)=-\infty$ if ![]() $m\geq k_*$. In addition, for any

$m\geq k_*$. In addition, for any ![]() $k_1 \lt k_*$ and

$k_1 \lt k_*$ and ![]() $k_2 \gt 0$, the set

$k_2 \gt 0$, the set  $\big\{u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\big|\|u\|_2^2\leq k_1~and~E(u)\leq k_2\big\}$ is bounded in

$\big\{u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\big|\|u\|_2^2\leq k_1~and~E(u)\leq k_2\big\}$ is bounded in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$.

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$.

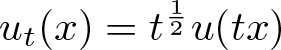

Proof. (i) Let ![]() $u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$ satisfy

$u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$ satisfy ![]() $F(u)=m$ and

$F(u)=m$ and  $\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$. Set

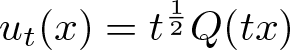

$\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$. Set  $u_t(x):=t^{\frac{1}{2}}u(tx)$. Then

$u_t(x):=t^{\frac{1}{2}}u(tx)$. Then ![]() $F(u_t)=\|u_t\|_2^2=\|u\|_2^2=m$ according to (3.1). So we have

$F(u_t)=\|u_t\|_2^2=\|u\|_2^2=m$ according to (3.1). So we have ![]() $I(m)\leq E(u_t)$. From (3.1) it follows that

$I(m)\leq E(u_t)$. From (3.1) it follows that

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(u_t)&=t^2\int_{\mathbb{R}}(u^{\prime})^2dx-2t\int_{\mathbb{R}}u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}dx

-\frac{2}{p+1}t^{\frac{p-1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx\\

&=t^2\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2t\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2-\frac{2}{p+1}t^{\frac{p-1}{2}}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(u_t)&=t^2\int_{\mathbb{R}}(u^{\prime})^2dx-2t\int_{\mathbb{R}}u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}dx

-\frac{2}{p+1}t^{\frac{p-1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx\\

&=t^2\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2t\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2-\frac{2}{p+1}t^{\frac{p-1}{2}}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} When ![]() $p \gt 5$, letting

$p \gt 5$, letting ![]() $t\to \infty$, we obtain

$t\to \infty$, we obtain  $

I(m)\leq\lim\limits_{t\to\infty}E(u_t)=-\infty.

$

$

I(m)\leq\lim\limits_{t\to\infty}E(u_t)=-\infty.

$

(ii) Notice that ![]() $u\in S_m$ if and only if there exists

$u\in S_m$ if and only if there exists ![]() $v\in S_1$ such that

$v\in S_1$ such that ![]() $u=\sqrt{m}v$. For any

$u=\sqrt{m}v$. For any ![]() $m \gt 0$ and

$m \gt 0$ and ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying  $\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$, there holds

$\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$, there holds

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(u)=E(\sqrt{m}v)&=m\|v'\|_2^2-2m\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2

-\frac{2}{p+1}m^{\frac{p+1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}v^{p+1}dx\\

&=m\big(\|v'\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2\big)

-\frac{2}{p+1}m^{\frac{p+1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}v^{p+1}dx.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(u)=E(\sqrt{m}v)&=m\|v'\|_2^2-2m\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2

-\frac{2}{p+1}m^{\frac{p+1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}v^{p+1}dx\\

&=m\big(\|v'\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2\big)

-\frac{2}{p+1}m^{\frac{p+1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}v^{p+1}dx.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}It follows from (1.3) and (3.7) that

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

I(m)&=\inf\big\{E(\sqrt{m}v)|v\in S_1\big\}\\

&=\inf\Big\{m\big(\|v'\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2\big)

-\frac{2}{p+1}m^{\frac{p+1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}v^{p+1}dx~\Big|~v\in S_1\Big\}.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

I(m)&=\inf\big\{E(\sqrt{m}v)|v\in S_1\big\}\\

&=\inf\Big\{m\big(\|v'\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2\big)

-\frac{2}{p+1}m^{\frac{p+1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}v^{p+1}dx~\Big|~v\in S_1\Big\}.

\end{aligned}

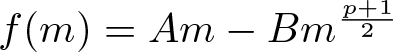

\end{equation*} For any ![]() $A\in\mathbb{R}$ and

$A\in\mathbb{R}$ and ![]() $B\geq0$, setting

$B\geq0$, setting  $f(m)=Am-Bm^{\frac{p+1}{2}}$, we have

$f(m)=Am-Bm^{\frac{p+1}{2}}$, we have

\begin{equation*}

f'(m)=A-\frac{p+1}{2}Bm^\frac{p-1}{2}~~{\rm{and}}~~f^{\prime\prime}(m)=-\frac{(p+1)(p-1)}{4}B

m^\frac{p-3}{2}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

f'(m)=A-\frac{p+1}{2}Bm^\frac{p-1}{2}~~{\rm{and}}~~f^{\prime\prime}(m)=-\frac{(p+1)(p-1)}{4}B

m^\frac{p-3}{2}.

\end{equation*} It is easy to see that ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}(m)\leq0$, and thus

$f^{\prime\prime}(m)\leq0$, and thus ![]() $f$ is concave on

$f$ is concave on ![]() $(0,\infty)$. Therefore, the infimum of a family of concave functions is also a concave function.

$(0,\infty)$. Therefore, the infimum of a family of concave functions is also a concave function.

(iii) For any ![]() $m \gt 0$ and

$m \gt 0$ and ![]() $\epsilon \gt 0$, we choose a function

$\epsilon \gt 0$, we choose a function ![]() $\eta\in C_c^{\infty}(\mathbb{R})$ such that

$\eta\in C_c^{\infty}(\mathbb{R})$ such that ![]() $\|\eta\|_2^2=2\pi m$ and the support of

$\|\eta\|_2^2=2\pi m$ and the support of ![]() $\eta$ is contained in the annulus

$\eta$ is contained in the annulus ![]() $B(0,1)\setminus B(0,1-\epsilon)$. Let

$B(0,1)\setminus B(0,1-\epsilon)$. Let ![]() $u=\mathcal{F}^{-1}(\eta)$. Then

$u=\mathcal{F}^{-1}(\eta)$. Then ![]() $u\in \mathcal{S}(\mathbb{R})$ and

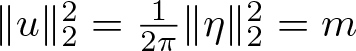

$u\in \mathcal{S}(\mathbb{R})$ and  $\|u\|_2^2=\frac{1}{2\pi}\|\eta\|_2^2=m$. By the Fourier transform, Plancherel’s formula and the fact that

$\|u\|_2^2=\frac{1}{2\pi}\|\eta\|_2^2=m$. By the Fourier transform, Plancherel’s formula and the fact that ![]() $0\leq(|\xi|-1)^2\leq4\epsilon^2$ on the support of

$0\leq(|\xi|-1)^2\leq4\epsilon^2$ on the support of ![]() $\eta$, we deduce

$\eta$, we deduce

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

&\int_{\mathbb{R}}(u^{\prime})^2dx-2\int_{\mathbb{R}}u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}dx

+\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^2dx

=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{\mathbb{R}}\big(|\xi|^2-2\xi+1\big)|\hat{u}(\xi)|^2d\xi\\

&\quad =\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{B(0,1)\setminus B(0,1-\epsilon)}

\big(|\xi|-1\big)^2|\eta(\xi)|^2d\xi

\leq\frac{4\epsilon^2}{2\pi}\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\eta(\xi)|^2d\xi=4\epsilon^2m

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

&\int_{\mathbb{R}}(u^{\prime})^2dx-2\int_{\mathbb{R}}u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}dx

+\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^2dx

=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{\mathbb{R}}\big(|\xi|^2-2\xi+1\big)|\hat{u}(\xi)|^2d\xi\\

&\quad =\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{B(0,1)\setminus B(0,1-\epsilon)}

\big(|\xi|-1\big)^2|\eta(\xi)|^2d\xi

\leq\frac{4\epsilon^2}{2\pi}\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\eta(\xi)|^2d\xi=4\epsilon^2m

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}and

\begin{equation*}

I(m)+m\leq E(u)+\|u\|_2^2\leq

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(u^{\prime})^2dx-2\int_{\mathbb{R}}u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}dx

+\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^2dx\leq4\epsilon^2m.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

I(m)+m\leq E(u)+\|u\|_2^2\leq

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(u^{\prime})^2dx-2\int_{\mathbb{R}}u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}dx

+\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^2dx\leq4\epsilon^2m.

\end{equation*} This indicates that ![]() $I(m)\leq-m+4\epsilon^2m$. Given that

$I(m)\leq-m+4\epsilon^2m$. Given that ![]() $\epsilon \gt 0$ is arbitrary, we see that (iii) follows.

$\epsilon \gt 0$ is arbitrary, we see that (iii) follows.

(iv) Using Plancherel’s formula again leads to

\begin{equation}

(1-\epsilon)\|v'\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2+\frac{1}{1-\epsilon}\|v\|_2^2

=\frac{1-\epsilon}{2\pi}\int_{\mathbb{R}}\Big(|\xi|-\frac{1}{1-\epsilon}\Big)^2|\hat{v}

(\xi)|^2d\xi\geq0.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

(1-\epsilon)\|v'\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2+\frac{1}{1-\epsilon}\|v\|_2^2

=\frac{1-\epsilon}{2\pi}\int_{\mathbb{R}}\Big(|\xi|-\frac{1}{1-\epsilon}\Big)^2|\hat{v}

(\xi)|^2d\xi\geq0.

\end{equation} Notice that the inequality sign in (3.8) is strict if ![]() $v\neq0$. When

$v\neq0$. When ![]() $p=5$, the Gagliardo–Nirenberg–Sobolev inequality (3.3) gives

$p=5$, the Gagliardo–Nirenberg–Sobolev inequality (3.3) gives

\begin{equation}

\|v\|_{p+1}^{p+1}\leq B\|v'\|_2^2\|v\|_2^4.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\|v\|_{p+1}^{p+1}\leq B\|v'\|_2^2\|v\|_2^4.

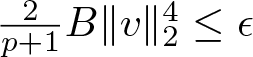

\end{equation} Let ![]() $0 \lt \epsilon \lt 1$. For any

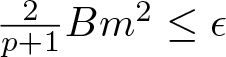

$0 \lt \epsilon \lt 1$. For any ![]() $v\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying

$v\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying  $\frac{2}{p+1} B \|v\|_2^4 \leq \epsilon$, from (3.9) we derive

$\frac{2}{p+1} B \|v\|_2^4 \leq \epsilon$, from (3.9) we derive

\begin{equation*}

E(v)\geq(1-\epsilon)\|v'\|^2_2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

E(v)\geq(1-\epsilon)\|v'\|^2_2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}v\|_2^2

\end{equation*} and from (3.8) we get  $E(v)\geq-\frac{1}{1-\epsilon}\|v\|^2_2$. This gives

$E(v)\geq-\frac{1}{1-\epsilon}\|v\|^2_2$. This gives ![]() $I(m)\geq-\frac{m}{1-\epsilon}$ for the positive

$I(m)\geq-\frac{m}{1-\epsilon}$ for the positive ![]() $m$ satisfying

$m$ satisfying  $\frac{2}{p+1} B m^2 \leq \epsilon$. Taking into account (iii), we obtain the desired result (iv).

$\frac{2}{p+1} B m^2 \leq \epsilon$. Taking into account (iii), we obtain the desired result (iv).

(v) For ![]() $u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$, we deduce from (3.2) and (3.3) that

$u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$, we deduce from (3.2) and (3.3) that

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(u)&\geq\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|u\|_2\|u^{\prime}\|_2-\frac{2}{p+1}B(p)\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2\|u\|_2^4\\

&=\Big(1-\frac{B(p)}{3}\|u\|_2^4\Big)\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|u\|_2\|u^{\prime}\|_2.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(u)&\geq\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|u\|_2\|u^{\prime}\|_2-\frac{2}{p+1}B(p)\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2\|u\|_2^4\\

&=\Big(1-\frac{B(p)}{3}\|u\|_2^4\Big)\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|u\|_2\|u^{\prime}\|_2.

\end{aligned}

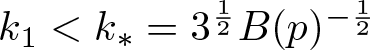

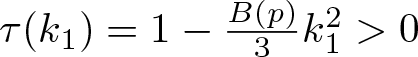

\end{equation} Let  $k_1 \lt k_*=3^{\frac{1}{2}}B(p)^{-{\frac{1}{2}}}$ and

$k_1 \lt k_*=3^{\frac{1}{2}}B(p)^{-{\frac{1}{2}}}$ and  $\tau(k_1)=1-\frac{B(p)}{3}k_1^2 \gt 0$. For any

$\tau(k_1)=1-\frac{B(p)}{3}k_1^2 \gt 0$. For any ![]() $u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$ such that

$u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$ such that ![]() $\|u\|_2^2 \lt k_1$, from 3.12 it follows that

$\|u\|_2^2 \lt k_1$, from 3.12 it follows that

\begin{equation}

E(u)\geq\tau(k_1)\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2k_1^{\frac{1}{2}}\|u^{\prime}\|_2

\geq\min_{s\in \mathbb{R}}\big(\tau(k_1)s^2-2k_1^{\frac{1}{2}}s\big)

=-\frac{k_1}{\tau(k_1)}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

E(u)\geq\tau(k_1)\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2k_1^{\frac{1}{2}}\|u^{\prime}\|_2

\geq\min_{s\in \mathbb{R}}\big(\tau(k_1)s^2-2k_1^{\frac{1}{2}}s\big)

=-\frac{k_1}{\tau(k_1)}.

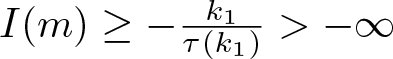

\end{equation} We infer that  $I(m)\geq -\frac{k_1}{\tau(k_1)} \gt -\infty$ for

$I(m)\geq -\frac{k_1}{\tau(k_1)} \gt -\infty$ for ![]() $m\in(0, k_1]$. Since

$m\in(0, k_1]$. Since ![]() $k_1 \lt k_*$ is arbitrary, we see that

$k_1 \lt k_*$ is arbitrary, we see that ![]() $I(m)$ is finite on

$I(m)$ is finite on ![]() $(0, k_*)$. Moreover, if

$(0, k_*)$. Moreover, if ![]() $\|u\|_2^2\leq k_1 \lt k_*$ and

$\|u\|_2^2\leq k_1 \lt k_*$ and ![]() $E(u)\leq k_2$, then (3.11) implies that

$E(u)\leq k_2$, then (3.11) implies that ![]() $\|u^{\prime}\|_2$ is bounded. Thus,

$\|u^{\prime}\|_2$ is bounded. Thus, ![]() $\|u\|_{H^1(\mathbb{R})}$ is bounded.

$\|u\|_{H^1(\mathbb{R})}$ is bounded.

Let ![]() $Q$ be an optimal function for the Gagliardo–Nirenberg–Sobolev inequality (3.3) with

$Q$ be an optimal function for the Gagliardo–Nirenberg–Sobolev inequality (3.3) with ![]() $p=5$ such that

$p=5$ such that  $\|Q\|_2=k_*^{\frac{1}{2}}=3^{\frac{1}{4}}B(p)^{-{\frac{1}{4}}}$. Such a function

$\|Q\|_2=k_*^{\frac{1}{2}}=3^{\frac{1}{4}}B(p)^{-{\frac{1}{4}}}$. Such a function ![]() $Q$ exists because if

$Q$ exists because if ![]() $u$ is an optimal function for (3.3), the rescaled function

$u$ is an optimal function for (3.3), the rescaled function ![]() $u_t(x)$ is an optimal function too. Then

$u_t(x)$ is an optimal function too. Then

\begin{equation*}

\frac{2}{p+1}\|Q\|_{p+1}^{p+1}=\frac{2}{p+1}B(p)\|Q'\|_2^2\|Q\|_2^4=\|Q'\|_2^2.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\frac{2}{p+1}\|Q\|_{p+1}^{p+1}=\frac{2}{p+1}B(p)\|Q'\|_2^2\|Q\|_2^4=\|Q'\|_2^2.

\end{equation*} For ![]() $t \gt 0$, let

$t \gt 0$, let  $u_t(x)=t^{\frac{1}{2}}Q(tx)$. From (3.1) and (3.6) it follows that

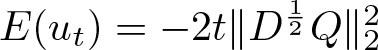

$u_t(x)=t^{\frac{1}{2}}Q(tx)$. From (3.1) and (3.6) it follows that ![]() $\|u_t\|_2^2= \|Q\|_2^2=k_*$ and

$\|u_t\|_2^2= \|Q\|_2^2=k_*$ and  $E(u_t)=-2t\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}Q\|_2^2$. Letting

$E(u_t)=-2t\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}Q\|_2^2$. Letting ![]() $t\to\infty$ leads to

$t\to\infty$ leads to ![]() $I(k_*)=-\infty$. If

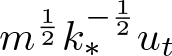

$I(k_*)=-\infty$. If ![]() $m \gt k_*$, using the test function

$m \gt k_*$, using the test function  $m^{\frac{1}{2}}k_*^{-\frac{1}{2}}u_t$ and letting

$m^{\frac{1}{2}}k_*^{-\frac{1}{2}}u_t$ and letting ![]() $t\to\infty$, we obtain

$t\to\infty$, we obtain ![]() $I(m) =-\infty$.

$I(m) =-\infty$.

For any ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying ![]() $F(u)=m$ and

$F(u)=m$ and  $\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$, a direct calculation gives

$\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$, a direct calculation gives

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(u)+\|u\|_2^2&=\int_{\mathbb{R}}\big[(u^{\prime})^2-2u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}-\frac{2}{p+1}u^{p+1}\big]dx

+\|u\|_2^2\\

&=\|u^{\prime}-u\|_2^2\Big(1-\frac{2m^{\frac{p-1}{2}}}{p+1}Q(u)^{p+1}\Big),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(u)+\|u\|_2^2&=\int_{\mathbb{R}}\big[(u^{\prime})^2-2u\mathcal{H}u^{\prime}-\frac{2}{p+1}u^{p+1}\big]dx

+\|u\|_2^2\\

&=\|u^{\prime}-u\|_2^2\Big(1-\frac{2m^{\frac{p-1}{2}}}{p+1}Q(u)^{p+1}\Big),

\end{aligned}

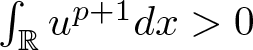

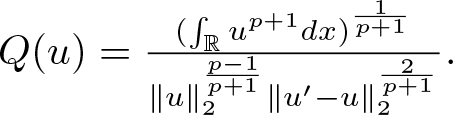

\end{equation} where  $

Q(u)=\frac{(\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx)^{\frac{1}{p+1}}}

{\|u\|_2^{\frac{p-1}{p+1}}\|u^{\prime}-u\|_2^{\frac{2}{p+1}}}.

$ Denote

$

Q(u)=\frac{(\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx)^{\frac{1}{p+1}}}

{\|u\|_2^{\frac{p-1}{p+1}}\|u^{\prime}-u\|_2^{\frac{2}{p+1}}}.

$ Denote

Remark 3.2. If ![]() $\tilde{Q}$ is finite, it follows from (3.12) that

$\tilde{Q}$ is finite, it follows from (3.12) that ![]() $

E(u)+\|u\|_2^2\geq0

$ for any

$

E(u)+\|u\|_2^2\geq0

$ for any ![]() $u$ satisfying

$u$ satisfying ![]() $F(u)=m$, provided that

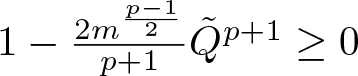

$F(u)=m$, provided that ![]() $m$ is small enough so that

$m$ is small enough so that  $1-\frac{2m^{\frac{p-1}{2}}}{p+1}\tilde{Q}^{p+1}\geq0$. This indicates that

$1-\frac{2m^{\frac{p-1}{2}}}{p+1}\tilde{Q}^{p+1}\geq0$. This indicates that ![]() $I(m)\geq -m$ for the sufficiently small

$I(m)\geq -m$ for the sufficiently small ![]() $m$, and thus the minimization problem (1.3) does not admit minimizers for the sufficiently small

$m$, and thus the minimization problem (1.3) does not admit minimizers for the sufficiently small ![]() $m$ either. If

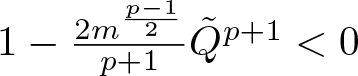

$m$ either. If ![]() $\tilde{Q}=\infty$, for any

$\tilde{Q}=\infty$, for any ![]() $m \gt 0$ we can find

$m \gt 0$ we can find ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\setminus\{0\}$ such that

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\setminus\{0\}$ such that  $1-\frac{2m^{\frac{p-1}{2}}}{p+1}\tilde{Q}^{p+1} \lt 0$. Then taking

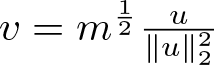

$1-\frac{2m^{\frac{p-1}{2}}}{p+1}\tilde{Q}^{p+1} \lt 0$. Then taking  $v=m^{\frac{1}{2}}\frac{u}{\|u\|_2^2}$ leads to

$v=m^{\frac{1}{2}}\frac{u}{\|u\|_2^2}$ leads to

From (3.12) we can see that ![]() $E(v)+\|v\|_2^2 \lt 0$, and thus

$E(v)+\|v\|_2^2 \lt 0$, and thus ![]() $I(m) \lt -m$.

$I(m) \lt -m$.

Let ![]() $p\in[2,\infty)$ and

$p\in[2,\infty)$ and ![]() $\kappa\in(0,1)$. For all

$\kappa\in(0,1)$. For all ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\setminus\{0\}$ we define

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\setminus\{0\}$ we define

\begin{equation}

Q_\kappa(u)=\frac{\|u\|_{p+1}}{\|u\|_2^\kappa\|(|D|-1)u\|_2^{1-\kappa}},~~~

\bar{Q}:=\sup_{u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\setminus\{0\}}Q_\kappa(u).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

Q_\kappa(u)=\frac{\|u\|_{p+1}}{\|u\|_2^\kappa\|(|D|-1)u\|_2^{1-\kappa}},~~~

\bar{Q}:=\sup_{u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})\setminus\{0\}}Q_\kappa(u).

\end{equation} Note that ![]() $\bar{Q}$ is finite if and only if the Gagliardo–Nirenberg type inequality

$\bar{Q}$ is finite if and only if the Gagliardo–Nirenberg type inequality

\begin{equation*}

\|u\|_{p+1}\leq C\|u\|_2^{\frac{p-1}{p+1}}\|u^{\prime}-u\|_2^{\frac{2}{p+1}}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\|u\|_{p+1}\leq C\|u\|_2^{\frac{p-1}{p+1}}\|u^{\prime}-u\|_2^{\frac{2}{p+1}}

\end{equation*} holds for all ![]() $u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$. Thus,

$u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$. Thus, ![]() $\bar{Q}$ is the best constant of this inequality.

$\bar{Q}$ is the best constant of this inequality.

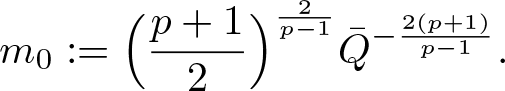

Let

\begin{equation}

m_0:=\Big(\frac{p+1}{2}\Big)^{\frac{2}{p-1}}\bar{Q}^{-\frac{2(p+1)}{p-1}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

m_0:=\Big(\frac{p+1}{2}\Big)^{\frac{2}{p-1}}\bar{Q}^{-\frac{2(p+1)}{p-1}}.

\end{equation} As we will see later, the problem (1.3) admits solutions if and only if ![]() $-\infty \lt I(m) \lt -m$. We have already known that

$-\infty \lt I(m) \lt -m$. We have already known that ![]() $I(m) =-\infty$ for all

$I(m) =-\infty$ for all ![]() $m$ when

$m$ when ![]() $p \gt 5$, see Proposition 3.1 (i).

$p \gt 5$, see Proposition 3.1 (i).

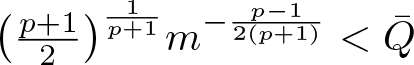

Proposition 3.3. When ![]() $p=5$ and

$p=5$ and ![]() $m_0$ is given by (3.14), we have

$m_0$ is given by (3.14), we have ![]() $m_0 \lt k_*$ and

$m_0 \lt k_*$ and ![]() $I(m)=-m$ when

$I(m)=-m$ when ![]() $m\in(0,m_0]$ and

$m\in(0,m_0]$ and ![]() $-\infty \lt I(m) \lt -m$ when

$-\infty \lt I(m) \lt -m$ when ![]() $m\in(m_0,k_*)$, where

$m\in(m_0,k_*)$, where ![]() $k_*$ is given in Proposition 3.1 (v).

$k_*$ is given in Proposition 3.1 (v).

Proof. If ![]() $m\in(0,m_0]$, for all

$m\in(0,m_0]$, for all ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying ![]() $F(u)=m$, from Lemma 2.4 and Remark 3.2 it follows that,

$F(u)=m$, from Lemma 2.4 and Remark 3.2 it follows that,

Hence, ![]() $I(m)+m\geq0$. By virtue of Proposition 3.1 (iii), we obtain

$I(m)+m\geq0$. By virtue of Proposition 3.1 (iii), we obtain ![]() $I(m)=-m$.

$I(m)=-m$.

If ![]() $m \gt m_0$, then

$m \gt m_0$, then  $\big(\frac{p+1}{2}\big)^{\frac{1}{p+1}}m^{-\frac{p-1}{2 (p+1)}} \lt \bar{Q}$. Choose

$\big(\frac{p+1}{2}\big)^{\frac{1}{p+1}}m^{-\frac{p-1}{2 (p+1)}} \lt \bar{Q}$. Choose ![]() $u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$ such that

$u\in H^1({\mathbb{R}})$ such that

\begin{equation*}

Q(u) \gt \Big(\frac{p+1}{2}\Big)^{\frac{1}{p+1}}m^{-\frac{p-1}{2 (p+1)}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

Q(u) \gt \Big(\frac{p+1}{2}\Big)^{\frac{1}{p+1}}m^{-\frac{p-1}{2 (p+1)}}.

\end{equation*} Let  $v=m^{\frac{1}{2}}\frac{u}{\|u\|_2}$. Then

$v=m^{\frac{1}{2}}\frac{u}{\|u\|_2}$. Then ![]() $\|v\|_2^2=m$ and

$\|v\|_2^2=m$ and ![]() $Q(v)=Q(u)$. From (3.12) it follows that

$Q(v)=Q(u)$. From (3.12) it follows that ![]() $E(v)+\|v\|_2^2 \lt 0$. Thus, we have

$E(v)+\|v\|_2^2 \lt 0$. Thus, we have ![]() $I(m) \lt -m$.

$I(m) \lt -m$.

To show ![]() $m_0 \lt k_*$, which is equivalent to that

$m_0 \lt k_*$, which is equivalent to that ![]() $B(p) \lt \bar{Q}^{p+1}$ when

$B(p) \lt \bar{Q}^{p+1}$ when ![]() $p=5$, where

$p=5$, where ![]() $B(p)$ is given by (3.4), we denote by

$B(p)$ is given by (3.4), we denote by ![]() $\mathcal{Q}(u)$ the quotient in the right-hand side of (3.4). Let

$\mathcal{Q}(u)$ the quotient in the right-hand side of (3.4). Let ![]() $u_*$ be an optimal function for (3.4). Then

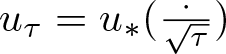

$u_*$ be an optimal function for (3.4). Then  $u_{\tau}=u_*(\frac{\cdot}{\sqrt{\tau}})$ is also an optimal function for (3.4), that is,

$u_{\tau}=u_*(\frac{\cdot}{\sqrt{\tau}})$ is also an optimal function for (3.4), that is, ![]() $\mathcal{Q}(u_{\tau})=B(p)$ for

$\mathcal{Q}(u_{\tau})=B(p)$ for ![]() $\tau \gt 0$. The conclusion follows if there is

$\tau \gt 0$. The conclusion follows if there is ![]() $\tau \gt 0$ such that

$\tau \gt 0$ such that ![]() $\mathcal{Q}(u_{\tau}) \lt Q_{\kappa}(u_\tau)^{p+1}$ which is equivalent to that

$\mathcal{Q}(u_{\tau}) \lt Q_{\kappa}(u_\tau)^{p+1}$ which is equivalent to that ![]() $\|u^{\prime}_{\tau}-u_\tau\|_2^2 \lt \|u^{\prime}_\tau\|_2^2$, or using Plancherel’s theorem gives

$\|u^{\prime}_{\tau}-u_\tau\|_2^2 \lt \|u^{\prime}_\tau\|_2^2$, or using Plancherel’s theorem gives

\begin{equation*}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(|\xi|-\tau)^2|\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi \lt \int_{\mathbb{R}}|\xi|^2|\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(|\xi|-\tau)^2|\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi \lt \int_{\mathbb{R}}|\xi|^2|\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi.

\end{equation*}The inequality can be written as

\begin{equation*}

-2\tau\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\xi||\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi+

\tau^2\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi \lt 0,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

-2\tau\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\xi||\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi+

\tau^2\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi \lt 0,

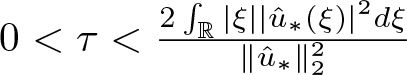

\end{equation*} if  $0 \lt \tau \lt \frac{2\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\xi||\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi}{\|\hat{u}_*\|_2^2}$. Thus, we have

$0 \lt \tau \lt \frac{2\int_{\mathbb{R}}|\xi||\hat{u}_*(\xi)|^2d\xi}{\|\hat{u}_*\|_2^2}$. Thus, we have ![]() $m_0 \lt k_*$. The rest arguments follow directly from Proposition 3.1 (v).

$m_0 \lt k_*$. The rest arguments follow directly from Proposition 3.1 (v).

Lemma 3.4. Assume that ![]() $p=5$ and

$p=5$ and ![]() $m\in(m_0,k_*)$, where

$m\in(m_0,k_*)$, where ![]() $m_0$ and

$m_0$ and ![]() $k_*$ are defined by (3.14) and (3.5), respectively. Then for any

$k_*$ are defined by (3.14) and (3.5), respectively. Then for any ![]() $m'\in(m_0,m)$ we have

$m'\in(m_0,m)$ we have ![]() $I(m) \lt I(m')+I(m-m')$.

$I(m) \lt I(m')+I(m-m')$.

Proof. For the fixed ![]() $m'\in(m_0,m)$, it suffices to prove that

$m'\in(m_0,m)$, it suffices to prove that

\begin{equation}

\forall~\theta\in(1,\frac{m}{m'}):~~I(\theta m') \lt \theta I(m').

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\forall~\theta\in(1,\frac{m}{m'}):~~I(\theta m') \lt \theta I(m').

\end{equation}Note that if (3.15) holds, then we have

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

I(m)=& \frac{m-m'}{m}I(m)+\frac{m'}{m}I(m)=\frac{m-m'}{m}I\left(\frac{m}{m-m'}(m-m')\right)

+\frac{m'}{m}

I\left(\frac{m}{m'}m'\right)\\ \lt &I(m')+I(m-m').

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

I(m)=& \frac{m-m'}{m}I(m)+\frac{m'}{m}I(m)=\frac{m-m'}{m}I\left(\frac{m}{m-m'}(m-m')\right)

+\frac{m'}{m}

I\left(\frac{m}{m'}m'\right)\\ \lt &I(m')+I(m-m').

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} Assume that ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfies

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfies ![]() $\|u\|_2^2=m'$. To prove (3.15), we consider

$\|u\|_2^2=m'$. To prove (3.15), we consider ![]() $v=\sqrt{\theta}u$. Note that

$v=\sqrt{\theta}u$. Note that ![]() $\|\sqrt{\theta}u\|_2^2=\theta\|u\|_2^2=\theta m'$ and

$\|\sqrt{\theta}u\|_2^2=\theta\|u\|_2^2=\theta m'$ and ![]() $\theta\in(1,\frac{m}{m'})$. Then

$\theta\in(1,\frac{m}{m'})$. Then

\begin{equation}

I(\theta m')\leq E(\sqrt{\theta}u)=\theta E(u)+\frac{2}{p+1}(\theta-\theta^{\frac{p+1}{2}})

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \lt \theta E(u) \lt \theta (I(m')+\epsilon).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

I(\theta m')\leq E(\sqrt{\theta}u)=\theta E(u)+\frac{2}{p+1}(\theta-\theta^{\frac{p+1}{2}})

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \lt \theta E(u) \lt \theta (I(m')+\epsilon).

\end{equation} Taking into account the arbitrariness of ![]() $\epsilon \gt 0$, we obtain

$\epsilon \gt 0$, we obtain ![]() $I(\theta m') \lt \theta I(m')$.

$I(\theta m') \lt \theta I(m')$.

Now, we are ready to prove Theorem 1.2.

Proof of Theorem 1.2

Let ![]() $\{u_n\}$ be a minimizing sequence. It follows from Proposition 3.1 (v) that

$\{u_n\}$ be a minimizing sequence. It follows from Proposition 3.1 (v) that ![]() $\{u_n\}$ is bounded in

$\{u_n\}$ is bounded in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$. Using (3.8) with

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$. Using (3.8) with ![]() $\epsilon=0$ we infer that for any

$\epsilon=0$ we infer that for any ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying  $\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$ there holds

$\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$ there holds

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx&=\frac{p+1}{2}\big(\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2+\|u\|_2^2\big)

-\frac{p+1}{2}\big(E(u)+\|u\|_2^2\big)\\

&\geq -\frac{p+1}{2}\big(E(u)+\|u\|_2^2\big).

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx&=\frac{p+1}{2}\big(\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2+\|u\|_2^2\big)

-\frac{p+1}{2}\big(E(u)+\|u\|_2^2\big)\\

&\geq -\frac{p+1}{2}\big(E(u)+\|u\|_2^2\big).

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} For ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ and

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ and ![]() $t \gt 0$, using Hölder’s inequality and the Sobolev embedding yields

$t \gt 0$, using Hölder’s inequality and the Sobolev embedding yields

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx&=\int_{\{u \lt t\}}u^{p+1}dx+\int_{\{u\geq t\}}u^{p+1}dx\\

&\leq t^{p-1}\int_{\{u \lt t\}}u^2dx+\Big(\int_{\{u\geq t\}}u^{p'+1}dx\Big)^{\frac{p+1}{p'+1}}

\mathcal{L}\big(\{u\geq t\}\big)^{1-\frac{p+1}{p'+1}}\\

&\leq t^{p-1}\|u\|_2^2+\Big(C_S\|u\|_{H^1({\mathbb{R}})}\Big)^{p+1}

\mathcal{L}\big(\{u\geq t\}\big)^{1-\frac{p+1}{p'+1}},

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx&=\int_{\{u \lt t\}}u^{p+1}dx+\int_{\{u\geq t\}}u^{p+1}dx\\

&\leq t^{p-1}\int_{\{u \lt t\}}u^2dx+\Big(\int_{\{u\geq t\}}u^{p'+1}dx\Big)^{\frac{p+1}{p'+1}}

\mathcal{L}\big(\{u\geq t\}\big)^{1-\frac{p+1}{p'+1}}\\

&\leq t^{p-1}\|u\|_2^2+\Big(C_S\|u\|_{H^1({\mathbb{R}})}\Big)^{p+1}

\mathcal{L}\big(\{u\geq t\}\big)^{1-\frac{p+1}{p'+1}},

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} where ![]() $p' \gt p$ and

$p' \gt p$ and ![]() $\mathcal{L}$ denotes the Lebesgue measure in

$\mathcal{L}$ denotes the Lebesgue measure in ![]() $\mathbb{R}$.

$\mathbb{R}$.

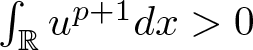

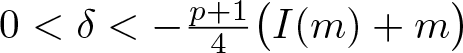

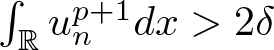

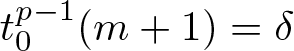

Choose  $0 \lt \delta \lt -\frac{p+1}{4}\big(I(m)+m\big)$. Since

$0 \lt \delta \lt -\frac{p+1}{4}\big(I(m)+m\big)$. Since ![]() $F(u_n)\to m$ and

$F(u_n)\to m$ and ![]() $E(u_n)\to I(m)$ as

$E(u_n)\to I(m)$ as ![]() $n\to\infty$, from (3.17) we have

$n\to\infty$, from (3.17) we have  $\int_{\mathbb{R}}u_n^{p+1}dx \gt 2\delta$ for the sufficiently large

$\int_{\mathbb{R}}u_n^{p+1}dx \gt 2\delta$ for the sufficiently large ![]() $n$. Choose

$n$. Choose ![]() $t_0 \gt 0$ such that

$t_0 \gt 0$ such that  $t_0^{p-1}(m+1)=\delta$. Given the boundedness of

$t_0^{p-1}(m+1)=\delta$. Given the boundedness of ![]() $\{u_n\}$ in

$\{u_n\}$ in ![]() $H^1({\mathbb{R}})$ and (3.18), there is a constant

$H^1({\mathbb{R}})$ and (3.18), there is a constant ![]() $a \gt 0$ independent of

$a \gt 0$ independent of ![]() $n$, such that

$n$, such that ![]() $\mathcal{L}(\{u_n\}\geq t_0

\})\geq a$ for the sufficiently large

$\mathcal{L}(\{u_n\}\geq t_0

\})\geq a$ for the sufficiently large ![]() $n$. According to Lieb’s Lemma [Reference Lieb25], there exists a constant

$n$. According to Lieb’s Lemma [Reference Lieb25], there exists a constant ![]() $b \gt 0$ independent of

$b \gt 0$ independent of ![]() $n$, and for the large

$n$, and for the large ![]() $n$ there exists

$n$ there exists ![]() $x_n\in \mathbb{R}$ such that

$x_n\in \mathbb{R}$ such that

\begin{equation}

\mathcal{L}\Big(\{x\in B(x_n,1)\big|u_n\geq\frac{t_0}{2}\}\Big)\geq b.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathcal{L}\Big(\{x\in B(x_n,1)\big|u_n\geq\frac{t_0}{2}\}\Big)\geq b.

\end{equation} We now replace ![]() $u_n$ by

$u_n$ by ![]() $u_n(\cdot+x_n)$, which is still a minimizing sequence and satisfies (3.19). Since

$u_n(\cdot+x_n)$, which is still a minimizing sequence and satisfies (3.19). Since ![]() $\{u_n\}$ is bounded in

$\{u_n\}$ is bounded in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$, there exists

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$, there exists ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ and a subsequence, still denoted by

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ and a subsequence, still denoted by ![]() $u_n$, such that

$u_n$, such that

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&u_n\rightharpoonup u ~~~{\rm{weakly~in}}~H^1({\mathbb{R}}),\\

&u_n\to u~~~{\rm{in}}~L^p_{loc}({\mathbb{R}})~~{\rm{for}}~p\geq1~{\rm{a.e.}}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&u_n\rightharpoonup u ~~~{\rm{weakly~in}}~H^1({\mathbb{R}}),\\

&u_n\to u~~~{\rm{in}}~L^p_{loc}({\mathbb{R}})~~{\rm{for}}~p\geq1~{\rm{a.e.}}

\end{aligned}

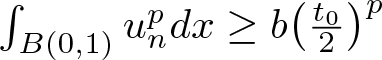

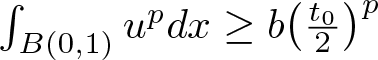

\end{equation} Clearly,  $\int_{B(0,1)}u_n^pdx\geq b\big(\frac{t_0}{2}\big)^{p}$ holds for the sufficiently large

$\int_{B(0,1)}u_n^pdx\geq b\big(\frac{t_0}{2}\big)^{p}$ holds for the sufficiently large ![]() $n$. Passing to the limit, we get

$n$. Passing to the limit, we get  $\int_{B(0,1)}u^pdx\geq b\big(\frac{t_0}{2}\big)^{p}$. Then we get

$\int_{B(0,1)}u^pdx\geq b\big(\frac{t_0}{2}\big)^{p}$. Then we get ![]() $u\neq 0$. Let

$u\neq 0$. Let ![]() $\|u\|_2^2=m_1$. We know that

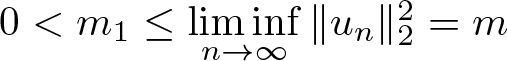

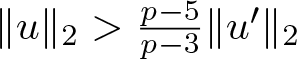

$\|u\|_2^2=m_1$. We know that  $0 \lt m_1\leq\liminf\limits_{n\to\infty}\|u_n\|_2^2=m$. To show that

$0 \lt m_1\leq\liminf\limits_{n\to\infty}\|u_n\|_2^2=m$. To show that ![]() $m_1$ can be equal to

$m_1$ can be equal to ![]() $m$, we argue by contradiction by assuming that

$m$, we argue by contradiction by assuming that ![]() $m_1 \lt m$. Then

$m_1 \lt m$. Then

Observe that if ![]() $\epsilon$ is positive and small, and

$\epsilon$ is positive and small, and ![]() $f$ is a function such that

$f$ is a function such that ![]() $|F(f)-m| \lt \epsilon$, then

$|F(f)-m| \lt \epsilon$, then ![]() $F(\beta f)=m$, where

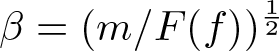

$F(\beta f)=m$, where  $\beta =(m/F(f))^{\frac{1}{2}}$ satisfies

$\beta =(m/F(f))^{\frac{1}{2}}$ satisfies ![]() $|\beta-1|\leq A_1\epsilon$ with

$|\beta-1|\leq A_1\epsilon$ with ![]() $A_1$ independent of

$A_1$ independent of ![]() $f$ and

$f$ and ![]() $\epsilon$. So we get

$\epsilon$. So we get

where ![]() $A_2$ depends only on

$A_2$ depends only on ![]() $A_1$ and

$A_1$ and ![]() $\|f\|_{H^1}$. A similar result holds for the function

$\|f\|_{H^1}$. A similar result holds for the function ![]() $g$ such that

$g$ such that ![]() $|F(g)-(m-m_1)| \lt \epsilon$.

$|F(g)-(m-m_1)| \lt \epsilon$.

From [Reference Pava32, Theorem 2.8], there exist a subsequence ![]() $\{u_{n_k}\}$ of

$\{u_{n_k}\}$ of ![]() $\{u_n\}$ and the associated functions

$\{u_n\}$ and the associated functions ![]() $f_{n_k}$ and

$f_{n_k}$ and ![]() $g_{n_k}$ such that for all

$g_{n_k}$ such that for all ![]() $k$ there hold

$k$ there hold

\begin{equation*}

E(f_{n_k})\geq I(m)-\frac{1}{k},\ \

E(g_{n_k})\geq I(m-m_1)-\frac{1}{k},\ \

E(u_{n_k})\geq E(f_{n_k})+E(g_{n_k})-\frac{1}{k}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

E(f_{n_k})\geq I(m)-\frac{1}{k},\ \

E(g_{n_k})\geq I(m-m_1)-\frac{1}{k},\ \

E(u_{n_k})\geq E(f_{n_k})+E(g_{n_k})-\frac{1}{k}.

\end{equation*}Then we have

\begin{equation*}

E(u_{n_k})\geq I(m)+I(m-m_1)-\frac{3}{k}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

E(u_{n_k})\geq I(m)+I(m-m_1)-\frac{3}{k}.

\end{equation*} Thus, (3.21) follows by taking the limit ![]() $k\to\infty$. However, from Lemma 3.4 we know that

$k\to\infty$. However, from Lemma 3.4 we know that ![]() $I(m) \lt I(m_1)+I(m-m_1)$. This contradiction means that

$I(m) \lt I(m_1)+I(m-m_1)$. This contradiction means that ![]() $m_1=m$.

$m_1=m$.

To show that ![]() $u_n\to u$ strongly in

$u_n\to u$ strongly in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$, we know that

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$, we know that ![]() $u_n\to u$ strongly in

$u_n\to u$ strongly in ![]() $L^2(\mathbb{R})$ due to (3.20) and the fact of

$L^2(\mathbb{R})$ due to (3.20) and the fact of ![]() $\|u_n\|_2^2\to m$. The weak convergence

$\|u_n\|_2^2\to m$. The weak convergence ![]() $u_n\rightharpoonup u$ in

$u_n\rightharpoonup u$ in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$ indicates that

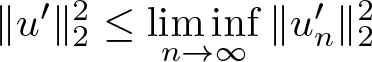

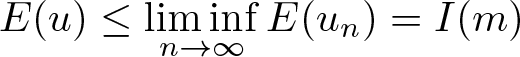

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$ indicates that  $\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2\leq \liminf\limits_{n\to\infty}\|u^{\prime}_n\|_2^2$ and

$\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2\leq \liminf\limits_{n\to\infty}\|u^{\prime}_n\|_2^2$ and  $E(u)\leq \liminf\limits_{n\to\infty}E(u_n)=I(m)$.

$E(u)\leq \liminf\limits_{n\to\infty}E(u_n)=I(m)$.

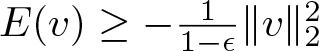

On the other hand, we have ![]() $E(u)\geq I(m)$ due to

$E(u)\geq I(m)$ due to ![]() $F(u)=m$. Thus,

$F(u)=m$. Thus, ![]() $E(u)=I(m)$ and

$E(u)=I(m)$ and ![]() $u$ solves the minimization problem (1.3). Moreover, we have

$u$ solves the minimization problem (1.3). Moreover, we have ![]() $\|u^{\prime}_n\|_2^2\to\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2$. Since

$\|u^{\prime}_n\|_2^2\to\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2$. Since ![]() $u^{\prime}_n\rightharpoonup u^{\prime}$ weakly in

$u^{\prime}_n\rightharpoonup u^{\prime}$ weakly in ![]() $L^2(\mathbb{R})$, we infer that

$L^2(\mathbb{R})$, we infer that ![]() $u^{\prime}_n\to u^{\prime}$ strongly in

$u^{\prime}_n\to u^{\prime}$ strongly in ![]() $L^2(\mathbb{R})$. This implies that

$L^2(\mathbb{R})$. This implies that ![]() $u_n\to u$ strongly in

$u_n\to u$ strongly in ![]() $H^1(\mathbb{R})$.

$H^1(\mathbb{R})$.

Proof of Theorem 1.3

In view of the definition of the orbital stability, we need to prove that the solution ![]() $\phi(t)$ of (1.1) exists globally, at least for initial data

$\phi(t)$ of (1.1) exists globally, at least for initial data ![]() $\phi_0$ sufficiently close to

$\phi_0$ sufficiently close to ![]() $\mathcal{G}_m$.

$\mathcal{G}_m$.

Since ![]() $p=5$, we deduce from the conservation laws and (3.2) and (3.3) that

$p=5$, we deduce from the conservation laws and (3.2) and (3.3) that

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(\phi_0)=E(\phi(t))&=\|\phi'(t)\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}\phi(t)\|_2^2-\frac{1}{3}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(\phi(t,x))^{6}dx\\

&\geq\|\phi'(t)\|_2^2-2\|\phi'(t)\|_2\|\phi_0\|_2-\frac{1}{3}B(p)

\|\phi'(t)\|^{2}_2\|\phi_0\|^{4}_2\\

&\geq\|\phi'(t)\|_2^2-2\epsilon\|\phi'(t)\|^2_2-2C(\epsilon,\|\phi_0\|_2)

-\Big(\frac{\|\phi_0\|^2_2}{k_*}\Big)^2

\|\phi'(t)\|^2_2.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

E(\phi_0)=E(\phi(t))&=\|\phi'(t)\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}\phi(t)\|_2^2-\frac{1}{3}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(\phi(t,x))^{6}dx\\

&\geq\|\phi'(t)\|_2^2-2\|\phi'(t)\|_2\|\phi_0\|_2-\frac{1}{3}B(p)

\|\phi'(t)\|^{2}_2\|\phi_0\|^{4}_2\\

&\geq\|\phi'(t)\|_2^2-2\epsilon\|\phi'(t)\|^2_2-2C(\epsilon,\|\phi_0\|_2)

-\Big(\frac{\|\phi_0\|^2_2}{k_*}\Big)^2

\|\phi'(t)\|^2_2.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} This implies that the solution ![]() $\phi(t)$ of (1.1) with initial data

$\phi(t)$ of (1.1) with initial data ![]() $\phi_0$ is global when

$\phi_0$ is global when ![]() $\|\phi_0\|^2_2 \lt k_*$. In addition, we deduce from

$\|\phi_0\|^2_2 \lt k_*$. In addition, we deduce from ![]() $m \lt k_*$ that there exists

$m \lt k_*$ that there exists ![]() $\epsilon \gt 0$ such that

$\epsilon \gt 0$ such that ![]() $\|v\|^2_2 \lt k_*$ for all

$\|v\|^2_2 \lt k_*$ for all ![]() $v\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying

$v\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying ![]() $dist(v,\mathcal{G}_m) \lt \epsilon$. Thus, when

$dist(v,\mathcal{G}_m) \lt \epsilon$. Thus, when ![]() $dist(\phi_0,\mathcal{G}_m) \lt \epsilon$, the solution

$dist(\phi_0,\mathcal{G}_m) \lt \epsilon$, the solution ![]() $\phi(t)$ of (1.1) with initial data

$\phi(t)$ of (1.1) with initial data ![]() $\phi_0$ exists globally.

$\phi_0$ exists globally.

To show the stability of the set ![]() $\mathcal{G}_m$, we prove by way of contradiction. Assume that there exist

$\mathcal{G}_m$, we prove by way of contradiction. Assume that there exist ![]() $\epsilon_0 \gt 0$ and a sequence of initial data

$\epsilon_0 \gt 0$ and a sequence of initial data ![]() $\{\phi_0^n\}$ such that

$\{\phi_0^n\}$ such that

\begin{equation}

dist(\phi^n_0, \mathcal{G}_m) \lt \frac{1}{n},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

dist(\phi^n_0, \mathcal{G}_m) \lt \frac{1}{n},

\end{equation} and there exists ![]() $\{t_n\}$ such that the corresponding solution sequence

$\{t_n\}$ such that the corresponding solution sequence ![]() $\{\phi_n(t_n)\}$ of (1.1) satisfies

$\{\phi_n(t_n)\}$ of (1.1) satisfies

We claim that there exists ![]() $v\in \mathcal{G}_m$ such that

$v\in \mathcal{G}_m$ such that

\begin{equation*}

\lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\|\phi_{0,n}-v\|_{H^1}=0.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\|\phi_{0,n}-v\|_{H^1}=0.

\end{equation*} Indeed, by (3.23) there exists ![]() $\{v_n\}\subset \mathcal{G}_m$ such that

$\{v_n\}\subset \mathcal{G}_m$ such that

\begin{equation}

\|\phi_{0,n}-v_n\|_{H^1} \lt \frac{2}{n}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\|\phi_{0,n}-v_n\|_{H^1} \lt \frac{2}{n}.

\end{equation} That is, ![]() $\{v_n\}\subset \mathcal{G}_m$ implies that

$\{v_n\}\subset \mathcal{G}_m$ implies that ![]() $\{v_n\}\subset S_m$ is a minimizing sequence of

$\{v_n\}\subset S_m$ is a minimizing sequence of ![]() $E$. By virtue of Theorem 1.2, there exist a subsequence

$E$. By virtue of Theorem 1.2, there exist a subsequence ![]() $\{v_{n}\}$, a sequence

$\{v_{n}\}$, a sequence ![]() $\{x_n\}\subset \mathbb{R}$ and

$\{x_n\}\subset \mathbb{R}$ and ![]() $v_0\in\mathcal{G}_m$ such that

$v_0\in\mathcal{G}_m$ such that

\begin{equation}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|v_{n}(\cdot+x_n)-v_0\|_{H^1}=0.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|v_{n}(\cdot+x_n)-v_0\|_{H^1}=0.

\end{equation}Therefore, the above claim follows from (3.25) and (3.26) immediately. Then we get

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|\phi_{0,n}\|_2^2=\|v\|_2^2=m,~\ \

\lim_{n\to\infty}E(\phi_{0,n})=E(v)=I(m).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|\phi_{0,n}\|_2^2=\|v\|_2^2=m,~\ \

\lim_{n\to\infty}E(\phi_{0,n})=E(v)=I(m).

\end{equation*}By the conservation of mass and energy, we have

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2^2=m,~\ \ \lim_{n\to\infty}E(\phi_n(t_n))=E(v)=I(m).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2^2=m,~\ \ \lim_{n\to\infty}E(\phi_n(t_n))=E(v)=I(m).

\end{equation*} Using (3.22) and the fact that ![]() $\{\phi_n(t_n)\}$ is bounded in

$\{\phi_n(t_n)\}$ is bounded in ![]() $H^1$, we set

$H^1$, we set

\begin{equation*}

\varphi_n=\frac{\sqrt{m}\phi_n(t_n)}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\varphi_n=\frac{\sqrt{m}\phi_n(t_n)}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}.

\end{equation*} Then ![]() $\|\varphi_n\|^2_2=m$ and

$\|\varphi_n\|^2_2=m$ and

\begin{align*}

E(\varphi_n)&=\Big(\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)^2

\Big(\|\phi^{\prime}_n(t_n)\|^2_2-\frac{1}{2}\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}\phi_n(t_n)\|_2^2\Big)\\

&~~~~-\Big(\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)^{p+1}\frac{2}{p+1}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(\phi_n(t_n,x))^{p+1}dx\\

&=\frac{m}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2^2}E(\phi_n(t_n))\\

&\quad +\Bigg[\Big(\frac{\sqrt{m}}

{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)^2

-\Big(\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)^{p+1}\Bigg]\frac{2}{p+1}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(\phi_n(t_n,x))^{p+1}dx,

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

E(\varphi_n)&=\Big(\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)^2

\Big(\|\phi^{\prime}_n(t_n)\|^2_2-\frac{1}{2}\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}\phi_n(t_n)\|_2^2\Big)\\

&~~~~-\Big(\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)^{p+1}\frac{2}{p+1}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(\phi_n(t_n,x))^{p+1}dx\\

&=\frac{m}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2^2}E(\phi_n(t_n))\\

&\quad +\Bigg[\Big(\frac{\sqrt{m}}

{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)^2

-\Big(\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)^{p+1}\Bigg]\frac{2}{p+1}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}(\phi_n(t_n,x))^{p+1}dx,

\end{align*}which implies that

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{n\to\infty}E(\varphi_n)=\lim_{n\to\infty}E(\phi_n(t_n))=I(m).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\lim_{n\to\infty}E(\varphi_n)=\lim_{n\to\infty}E(\phi_n(t_n))=I(m).

\end{equation*} Thus, ![]() $\{\varphi_n\}\subset S_m$ is a minimizing sequence of

$\{\varphi_n\}\subset S_m$ is a minimizing sequence of ![]() $E$. According to Theorem 1.2, there exist a subsequence (still denoted by)

$E$. According to Theorem 1.2, there exist a subsequence (still denoted by) ![]() $\{\varphi_{n}\}$, a sequence

$\{\varphi_{n}\}$, a sequence ![]() $\{x_n\}\subset \mathbb{R}$ and

$\{x_n\}\subset \mathbb{R}$ and ![]() $\tilde{v}\in \mathcal{G}_m$ such that

$\tilde{v}\in \mathcal{G}_m$ such that

\begin{equation}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|\varphi_n(\cdot+x_n)-\tilde{v}\|_{H^1}=0.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|\varphi_n(\cdot+x_n)-\tilde{v}\|_{H^1}=0.

\end{equation} By the definition of ![]() $\varphi_n$, we obtain

$\varphi_n$, we obtain

\begin{equation}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|\varphi_n-\phi_n(t_n)\|_{H^1}

=\lim_{n\to\infty}\Big(1-\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)

\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_{H^1}=0.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\lim_{n\to\infty}\|\varphi_n-\phi_n(t_n)\|_{H^1}

=\lim_{n\to\infty}\Big(1-\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_2}\Big)

\|\phi_n(t_n)\|_{H^1}=0.

\end{equation}From (3.27) and (3.28) it follows that

which contradicts (3.24). Consequently, the proof is complete.

4. A local minimization problem

In this section, we investigate the ![]() $L^2$-supercritical case by considering a local minimization problem. For any

$L^2$-supercritical case by considering a local minimization problem. For any ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ satisfying  $\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$, we let

$\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx \gt 0$, we let  $u_t(x)=t^{\frac{1}{2}}u(tx)$ and denote

$u_t(x)=t^{\frac{1}{2}}u(tx)$ and denote

\begin{equation*}

\varphi_u(t)=E(u_t)=t^2\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2t\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2-\frac{2}{p+1}

t^{\frac{p-1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\varphi_u(t)=E(u_t)=t^2\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2t\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2-\frac{2}{p+1}

t^{\frac{p-1}{2}}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx,

\end{equation*} \begin{equation}

D(u)=\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{4(p+1)}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

D(u)=\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{4(p+1)}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.

\end{equation}Lemma 4.1. Let ![]() $a,~b,~c \gt 0$ and define

$a,~b,~c \gt 0$ and define ![]() $f:~[0,\infty)\to \mathbb{R}$ by

$f:~[0,\infty)\to \mathbb{R}$ by

\begin{equation}

f(t)=at^2-2bt-ct^{\frac{p-1}{2}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

f(t)=at^2-2bt-ct^{\frac{p-1}{2}}.

\end{equation}Then we have

(i) The second derivative ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}$ is decreasing. There exists a unique

$f^{\prime\prime}$ is decreasing. There exists a unique ![]() $t_{infl} \gt 0$ such that

$t_{infl} \gt 0$ such that ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}(t_{infl})=0$, where

$f^{\prime\prime}(t_{infl})=0$, where ![]() $t_{infl}$ is given by

$t_{infl}$ is given by

\begin{equation*}

t_{infl}=\Big(\frac{8a}{(p-1)(p-3)c}\Big)^{\frac{2}{p-5}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

t_{infl}=\Big(\frac{8a}{(p-1)(p-3)c}\Big)^{\frac{2}{p-5}}.

\end{equation*} (ii) The derivative ![]() $f'$ is increasing on

$f'$ is increasing on ![]() $[0,t_{infl}]$ and decreasing on

$[0,t_{infl}]$ and decreasing on ![]() $[t_{infl},\infty)$, and we have

$[t_{infl},\infty)$, and we have ![]() $f'(t_{infl}) \gt 0$ if and only if

$f'(t_{infl}) \gt 0$ if and only if

\begin{equation*}

a^{\frac{3-p}{2}}b^{\frac{p-5}{2}}c \lt \frac{8}{(p-1)(p-3)}\Big(\frac{p-5}{p-3}\Big)

^{\frac{p-5}{2}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

a^{\frac{3-p}{2}}b^{\frac{p-5}{2}}c \lt \frac{8}{(p-1)(p-3)}\Big(\frac{p-5}{p-3}\Big)

^{\frac{p-5}{2}}.

\end{equation*} When ![]() $f'(t_{infl}) \gt 0$, the following three statements are true.

$f'(t_{infl}) \gt 0$, the following three statements are true.

(iii) There exist a unique ![]() $t_1\in(0,t_{infl})$ and a unique

$t_1\in(0,t_{infl})$ and a unique ![]() $t_2\in(t_{infl},\infty)$ such that

$t_2\in(t_{infl},\infty)$ such that ![]() $f'(t_1)=0$ and

$f'(t_1)=0$ and ![]() $f'(t_2)=0$. The map

$f'(t_2)=0$. The map ![]() $f$ is decreasing on

$f$ is decreasing on ![]() $[0,t_1]$, increasing on

$[0,t_1]$, increasing on ![]() $[t_1,t_2]$, decreasing on

$[t_1,t_2]$, decreasing on ![]() $[t_2,\infty)$ and attains its minimum at

$[t_2,\infty)$ and attains its minimum at ![]() $t_1\in [0,t_2]$.

$t_1\in [0,t_2]$.

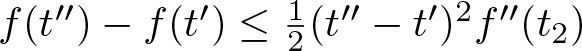

(iv) For ![]() $t_2\leq t' \lt t^{\prime\prime}$, we have

$t_2\leq t' \lt t^{\prime\prime}$, we have  $f(t^{\prime\prime})-f(t')\leq\frac{1}{2}(t^{\prime\prime}- t')^2f^{\prime\prime}(t_2)$.

$f(t^{\prime\prime})-f(t')\leq\frac{1}{2}(t^{\prime\prime}- t')^2f^{\prime\prime}(t_2)$.

(v) We have

\begin{equation*}

f(t_{infl})-f(t_1)=h\Big(\frac{t_{infl}}{t_1}\Big)t_1^{\frac{p-1}{2}}c,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

f(t_{infl})-f(t_1)=h\Big(\frac{t_{infl}}{t_1}\Big)t_1^{\frac{p-1}{2}}c,

\end{equation*}where

\begin{align*}

h(s)&=\frac{(p+1)(p-5)}{8}s^{\frac{p-1}{2}}-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{4}s^{\frac{p-3}{2}}\\

&\quad+\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{8}s^{\frac{p-5}{2}}+\frac{p-1}{2}(s-1)+1,

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

h(s)&=\frac{(p+1)(p-5)}{8}s^{\frac{p-1}{2}}-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{4}s^{\frac{p-3}{2}}\\

&\quad+\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{8}s^{\frac{p-5}{2}}+\frac{p-1}{2}(s-1)+1,

\end{align*} and the function ![]() $h(s)$ satisfies

$h(s)$ satisfies ![]() $h(1)=h'(1)=h^{\prime\prime}(1)$ and

$h(1)=h'(1)=h^{\prime\prime}(1)$ and

\begin{equation*}

h^{\prime\prime}(s)=\frac{(p-1)(p-3)(p-5)}{16}s^{\frac{p-9}{2}}(s-1)\Big(\frac{p+1}{2}s-\frac{p-7}{2}

\Big).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

h^{\prime\prime}(s)=\frac{(p-1)(p-3)(p-5)}{16}s^{\frac{p-9}{2}}(s-1)\Big(\frac{p+1}{2}s-\frac{p-7}{2}

\Big).

\end{equation*} Hence, ![]() $h(s)$ is positive, increasing and convex on

$h(s)$ is positive, increasing and convex on ![]() $(1,\infty)$.

$(1,\infty)$.

Proof. (i) From (4.2) it follows that

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

f^{\prime\prime}(t)&=2a-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{4}ct^{\frac{p-5}{2}},\\

f^{\prime\prime\prime}(t)&=-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)(p-5)}{8}ct^{\frac{p-7}{2}} \lt 0.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

f^{\prime\prime}(t)&=2a-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{4}ct^{\frac{p-5}{2}},\\

f^{\prime\prime\prime}(t)&=-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)(p-5)}{8}ct^{\frac{p-7}{2}} \lt 0.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} So, ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}$ is decreasing. Solving

$f^{\prime\prime}$ is decreasing. Solving ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}(t)=0$, we know that there exists a unique

$f^{\prime\prime}(t)=0$, we know that there exists a unique ![]() $t_{infl} \gt 0$ such that

$t_{infl} \gt 0$ such that ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}(t_{infl})=0$, where

$f^{\prime\prime}(t_{infl})=0$, where

\begin{equation*}

t_{infl}=\Big(\frac{8a}{(p-1)(p-3)c}\Big)^{\frac{2}{p-5}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

t_{infl}=\Big(\frac{8a}{(p-1)(p-3)c}\Big)^{\frac{2}{p-5}}.

\end{equation*} (ii) From ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}(t_{infl})=0$, we have

$f^{\prime\prime}(t_{infl})=0$, we have ![]() $f^{\prime\prime} \gt 0$ on

$f^{\prime\prime} \gt 0$ on ![]() $[0,t_{infl}]$ and

$[0,t_{infl}]$ and ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}(t) \lt 0$ on

$f^{\prime\prime}(t) \lt 0$ on ![]() $[t_{infl},\infty)$. Then

$[t_{infl},\infty)$. Then ![]() $f'$ is increasing on

$f'$ is increasing on ![]() $[0,t_{infl}]$ and decreasing on

$[0,t_{infl}]$ and decreasing on ![]() $[t_{infl},\infty)$. From the derivative expression

$[t_{infl},\infty)$. From the derivative expression

\begin{equation*}

f'(t_{infl})=\Big[\frac{8}{(p-1)(p-3)}\Big]^{\frac{2}{p-5}}\frac{2(p-5)}{p-3}a^{\frac{p-3}{p-5}}

c^{-\frac{2}{p-5}}-2b \gt 0,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

f'(t_{infl})=\Big[\frac{8}{(p-1)(p-3)}\Big]^{\frac{2}{p-5}}\frac{2(p-5)}{p-3}a^{\frac{p-3}{p-5}}

c^{-\frac{2}{p-5}}-2b \gt 0,

\end{equation*} we know that ![]() $f'(t_{infl}) \gt 0$ is equivalent to

$f'(t_{infl}) \gt 0$ is equivalent to

\begin{equation*}

a^{\frac{3-p}{2}}b^{\frac{p-5}{2}}c \lt \frac{8}{(p-1)(p-3)}\Big(\frac{p-5}{p-3}\Big)

^{\frac{p-5}{2}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

a^{\frac{3-p}{2}}b^{\frac{p-5}{2}}c \lt \frac{8}{(p-1)(p-3)}\Big(\frac{p-5}{p-3}\Big)

^{\frac{p-5}{2}}.

\end{equation*}(iii) By using (i) and (ii), we see that (iii) follows immediately.

(iv) Given that ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}$ is decreasing on

$f^{\prime\prime}$ is decreasing on ![]() $[0,\infty)$ and

$[0,\infty)$ and ![]() $f' \lt 0$ on

$f' \lt 0$ on ![]() $(t_2,\infty)$, we have

$(t_2,\infty)$, we have

\begin{align*}

f(t^{\prime\prime})-f(t')&=\int_{t'}^{t^{\prime\prime}}\Big(f'(t'+\int_{t'}^sf^{\prime\prime}(\tau)d\tau)\Big)ds

\leq\int_{t'}^{t^{\prime\prime}}\int_{t'}^sf^{\prime\prime}(\tau)d\tau ds\\

&=\frac{1}{2}(t^{\prime\prime}-t')^2f^{\prime\prime}(t_2).

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

f(t^{\prime\prime})-f(t')&=\int_{t'}^{t^{\prime\prime}}\Big(f'(t'+\int_{t'}^sf^{\prime\prime}(\tau)d\tau)\Big)ds

\leq\int_{t'}^{t^{\prime\prime}}\int_{t'}^sf^{\prime\prime}(\tau)d\tau ds\\

&=\frac{1}{2}(t^{\prime\prime}-t')^2f^{\prime\prime}(t_2).

\end{align*} (v) Let  $s=\frac{t_{infl}}{t_1}$

$s=\frac{t_{infl}}{t_1}$ ![]() $(s \gt 1)$. Letting

$(s \gt 1)$. Letting ![]() $f^{\prime\prime}(t_{infl})=f^{\prime\prime}(t_1s)=0$, we get

$f^{\prime\prime}(t_{infl})=f^{\prime\prime}(t_1s)=0$, we get  $a=\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{8}ct_1^{\frac{p-5}{2}}s^{\frac{p-5}{2}}$. Combining this with

$a=\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{8}ct_1^{\frac{p-5}{2}}s^{\frac{p-5}{2}}$. Combining this with ![]() $f'(t_1)=0$ gives

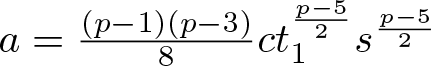

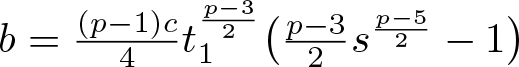

$f'(t_1)=0$ gives  $b=\frac{(p-1)c}{4}t_1^{\frac{p-3}{2}}\big(\frac{p-3}{2}s^{\frac{p-5}{2}}-1\big)$. Substituting the values of

$b=\frac{(p-1)c}{4}t_1^{\frac{p-3}{2}}\big(\frac{p-3}{2}s^{\frac{p-5}{2}}-1\big)$. Substituting the values of ![]() $a$ and

$a$ and ![]() $b$ into

$b$ into ![]() $f(t_1s)-f(t_1)$, we can arrive at the desired result (v).

$f(t_1s)-f(t_1)$, we can arrive at the desired result (v).

We now take the ![]() $H^{-1}-H^1$ duality product of the equation

$H^{-1}-H^1$ duality product of the equation

with ![]() $u$. Then any solution

$u$. Then any solution ![]() $u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ of (4.3) satisfies the identities

$u\in H^1(\mathbb{R})$ of (4.3) satisfies the identities ![]() $N_\omega(u)=0$ and

$N_\omega(u)=0$ and ![]() $P_\omega(u)=0$, where

$P_\omega(u)=0$, where

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

N_\omega(u)&=\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2+(1+\omega)\|u\|_2^2-

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx,\\

P_\omega(u)&=-\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2+(1+\omega)\|u\|_2^2-\frac{2}{p+1}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

N_\omega(u)&=\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2+(1+\omega)\|u\|_2^2-

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx,\\

P_\omega(u)&=-\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2+(1+\omega)\|u\|_2^2-\frac{2}{p+1}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}Let

\begin{equation*}

P_1(u)=\frac{1}{2}\Big(N_\omega(u)-P_\omega(u)\Big)=\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-

\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2

-\frac{p-1}{2(p+1)}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.\\

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

P_1(u)=\frac{1}{2}\Big(N_\omega(u)-P_\omega(u)\Big)=\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-

\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2

-\frac{p-1}{2(p+1)}\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx.\\

\end{equation*} To analyze the properties of the function ![]() $\varphi_u$, we observe

$\varphi_u$, we observe

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\varphi^{\prime}_u(t)&=2t\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2-\frac{p-1}{p+1}t^{\frac{p-3}{2}}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx=\frac{2}{t}P_1(u_t),\\

\varphi^{\prime\prime}_u(t)&=2\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{2(p+1)}t^{\frac{p-5}{2}}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx=\frac{2}{t^2}D(u_t).

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\varphi^{\prime}_u(t)&=2t\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-2\|D^{\frac{1}{2}}u\|_2^2-\frac{p-1}{p+1}t^{\frac{p-3}{2}}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx=\frac{2}{t}P_1(u_t),\\

\varphi^{\prime\prime}_u(t)&=2\|u^{\prime}\|_2^2-\frac{(p-1)(p-3)}{2(p+1)}t^{\frac{p-5}{2}}

\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx=\frac{2}{t^2}D(u_t).

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} For any ![]() $u\neq0$, there exists a unique

$u\neq0$, there exists a unique ![]() $t_{u,infl} \gt 0$ such that

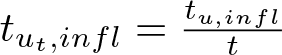

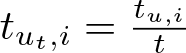

$t_{u,infl} \gt 0$ such that ![]() $\varphi^{\prime\prime}_u(t_{u,infl})=0$, where

$\varphi^{\prime\prime}_u(t_{u,infl})=0$, where

\begin{equation}

t_{u,infl}=\Big(\frac{4(p+1)}{(p-1)(p-3)}\int_{\mathbb{R}}(u^{\prime})^2dx\Big)

^{\frac{2}{p-5}}\Big(\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx\Big)

^{-\frac{2}{p-5}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

t_{u,infl}=\Big(\frac{4(p+1)}{(p-1)(p-3)}\int_{\mathbb{R}}(u^{\prime})^2dx\Big)

^{\frac{2}{p-5}}\Big(\int_{\mathbb{R}}u^{p+1}dx\Big)

^{-\frac{2}{p-5}}.

\end{equation} We have ![]() $\varphi^{\prime\prime}_u \gt 0$ on

$\varphi^{\prime\prime}_u \gt 0$ on ![]() $(0,t_{u,infl})$ and

$(0,t_{u,infl})$ and ![]() $\varphi^{\prime\prime}_u \lt 0$ on

$\varphi^{\prime\prime}_u \lt 0$ on ![]() $(t_{u,infl},\infty)$. Hence,

$(t_{u,infl},\infty)$. Hence, ![]() $\varphi ^{\prime}_u$ is increasing on

$\varphi ^{\prime}_u$ is increasing on ![]() $(0,t_{u,infl}]$ and decreasing on

$(0,t_{u,infl}]$ and decreasing on ![]() $[t_{u,infl},\infty)$, and attains its maximum at

$[t_{u,infl},\infty)$, and attains its maximum at ![]() $t_{u,infl}$. If

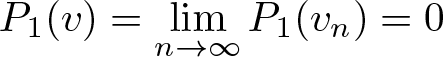

$t_{u,infl}$. If ![]() $\varphi^{\prime}_u(t_{u,infl})\leq0$, the mapping