Opening the fourth poem of his Peristephanon, Prudentius (d. after 405 CE) painted an arresting scene of the eschatological future. The cities of the Christian world processed in personified forms toward the seat of judgement, each bearing the martyrs it had produced as sacrifices to be offered to Christ. Cities from across the Mediterranean world appear. Several are Iberian—Córdoba, Tarragona, Girona, Calahorra, Barcelona, and more—while others are from further afield—Carthage, Tangiers, Narbonne, and Arles. The scene recalls both the solemn, staged processions of late antique civic ceremonial and those of its Christian liturgical derivatives. Two features stand out. First, Prudentius’s view of cult was resolutely urban: each martyr pertained to a given city and was in some sense its particular offering to the universal Church. Second, it was in the liturgical form of civic ceremonial that Prudentius chose to dramatize this link. There is perhaps no clearer evocation of the inextricable link between city, ceremony, and martyr in late antique literature.Footnote 1

When we move forward in time to the medieval martyr passions, however, the place of the civic in martyr cult becomes more difficult to establish. The bulk of Iberian martyr passions survive in compilations known collectively as the Pasionario Hispánico, the earliest manuscripts of which were copied in a handful of tenth- and eleventh-century monastic scriptoria (San Pedro de Cardeña, Santo Domingo de Silos, perhaps San Pedro de Arlanza) in the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain.Footnote 2 The core of the collection seems to have been in circulation by 806, when an anonymous martyrologist in Lyon drew on a primitive version containing at least forty-eight texts, but no evidence proves the existence of such an authoritative collection in the Visigothic period.Footnote 3 The collection, as we have it, was the product of a particular tradition of compilation in certain monasteries, not a general liturgical book provided for the use of the whole Iberian church.Footnote 4 The putative late Roman or Visigothic provenance of any passion text has to be argued, therefore, on a case-by-case basis. While substantial progress has been made in this regard, the passions remain difficult texts, rarely attributable to a precise historical moment or author.

What does this mean for the study of civic Christianity in the post-Roman centuries? Martyr passions have, of course, long been mined for evidence by scholars of Visigothic religion, who have frequently regarded them as ‘popular’ texts that communicated with a wide audience when they were read liturgically on the feast days of the saints.Footnote 5 On this understanding, martyr passions, like sermons, offer a glimpse of the pastoral encounter between preacher and congregation. Such scholarship follows well-trodden paths for thinking about the role of martyr cults in urban religion.Footnote 6 The monastic transmission of the passions should give us pause, however. They come down to us in manuscripts produced in a context distant from the social world of the late antique city, raising the suspicion that much has been lost in transmission. On a skeptical reading, their view of the city could be little more than an imaginary and archaizing one, reframed for an audience of sequestered spiritual professionals.

Thus, a countervailing strand of scholarship situates martyr passions within the context of monastic spirituality, as evidence for the patronage of saints’ cults by monasteries and their narrow elites of spiritual practitioners. It has been suggested, for example, that the Passion of Eulalia of Mérida comes down to us in a Visigothic redaction attuned to the cultural exigencies of a female coenobium.Footnote 7 Similarly, the remarkable historical accounts of Iberian Christian origins contained in the Visigothic Confession of Leocadia of Toledo and Passion of Vincent, Sabine, and Christeta of Ávila have been identified with the elitist ascetic ecclesiology of figures such as Valerius of Bierzo (d. c. 695), an eremitic Galician monk whose interest in the martyrs was founded on the distinctly un-civic idea that they were the precursors to a small elite of monastics who had withdrawn from city life.Footnote 8 Even Prudentius’s writings are now more typically placed within the context of private devotional reading than public, urban cult.Footnote 9 Of course, monastic and popular use are not mutually exclusive. Texts could move between contexts with ease, and monastics often played a role in urban cult. Yet, the very notion that martyr passions constitute direct evidence for civic religion remains questionable. While monastic engagement with the passions is evident from the manuscripts, the putative civic origins that lie behind these later copies can be revealed only through extended argument.

In what follows, I aim to establish a firmer basis for the civic context of martyr passions through a single case study: that of the ‘Eighteen’ or ‘Innumerable’ martyrs of Zaragoza, the very martyrs whom Prudentius was celebrating in the poem mentioned above. Less famous than their co-citizen Vincent of Zaragoza, they attracted a cult that was primarily local in the Visigothic period before spreading further afield in the post-Visigothic centuries.Footnote 10 The cult benefitted, however, from being situated in a city that flourished in late antiquity. A major urban settlement in the Roman period, covering an area of up to seventy hectares at its imperial apogee, Zaragoza remained a substantial city, with an intramural area of around forty-five hectares by the time it was enclosed in new defensive walls in the third century.Footnote 11 Despite suffering many of the transformations of classical monumental space typical of late antique cities, including a degree of urban abatement from the third century onwards, it enjoyed considerable investment in its fortifications and retained at least some elements of a recognizably classical ceremonial life.Footnote 12 Indeed, it was a city in which the Roman Emperor Majorian saw fit to stage an adventus in the 460s, and one in which games were still held as late as 504/505.Footnote 13 It continued to be an important regional center through the Visigothic and Umayyad periods.Footnote 14

Beyond the importance of the city, there are two main reasons why Zaragoza’s martyrs constitute such a valuable case study in civic use of martyr cult. First, the provenance of the redactions of the Passion of the Innumerable can be established with a degree of precision unparalleled in the wider Iberian corpus.Footnote 15 It has long been argued, most influentially in an article from 1933 by André Lambert, that the earliest surviving version of the Passion (BHL 1505) was composed in the 590s in Zaragoza, in the fraught wake of the Visigothic conversion to Nicene Christianity.Footnote 16 Its Visigothic provenance has never been in doubt, therefore, even while attempts to attach it to known figures like Braulio of Zaragoza (d. 651) or Eugenius II of Toledo (d. 657) have failed. It is clear, too, that the Passion was intended for oral delivery on the martyrs’ feast day.Footnote 17 Uniquely, then, this text offers a secure basis on which to see how martyr cult was framed within a particular civic context of public cult and doctrinal conflict, in a city whose post-Roman development is comparatively well known.

Second, there survives an additional Carolingian redaction of the text (BHL 1503), produced in the monastery of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris, over 800 kilometers away. This redaction, which survives in manuscripts from the ninth century onwards, mainly from France, was most likely produced in the 860s, shortly after the monks Usuard and Odilard returned from their journey through al-Andalus. It has never been critically edited, and demands study in its own right.Footnote 18 The Passion of the Innumerable was not unique in undergoing réécriture in Frankish scriptoria, as a recent study of a ninth-century version of the Passion of Cucufas of Barcelona, perhaps produced in Saint-Denis in Paris, has shown.Footnote 19 The Zaragozan Passion does, however, offer us a particularly clear and well-evidenced example of the process of ‘monasticization’ undergone by urban cult texts when they were uprooted from their immediate local context and reworked for more generic cloistered use. In what follows, I will refer to its two versions as the “Iberian redaction” and the “Carolingian redaction,” respectively.

A comparison of these two texts leads us to conclusions of a wider import. It shows, first, that the Iberian line of transmission was considerably more textually conservative than its Carolingian counterpart, suggesting that a great deal of Iberian material might be found in the Pasionario Hispánico that has not undergone the réécriture that occurred elsewhere. Second, the Iberian redaction of the Passion of the Innumerable rewards study on its own terms. It stands out as precious and rare evidence for urban religiosity in the Visigothic period and provides a window onto the ways ecclesiastical authorities leveraged the ideology of consensus around shared martyrs and persecution history as a tool in their management of community relations, particularly in the wake of the confessional conflict between Nicene and Homoian Christians that erupted in the 580s. In sum, the Passion of the Innumerable allows us to study both the civic and the monastic framings of cult and to place them in dialogue. This is an exercise with wider implications for how we think about the Iberian passions, and indeed for liturgy, pastoral care, and the Christian crowd in the Visigothic world.

The Iberian Redaction

From the ‘Eighteen’ to the ‘Innumerable’ Martyrs of Zaragoza

The cult of the Zaragozan martyrs presents immediate difficulties: it is a moving target, shifting appreciably in focus and scope as we trace it through time. It is essential to recognize at the outset that the Passion of the Innumerable reflects only one distinctive framing of the cult, which does not coincide in all elements with those that came before and after. Our earliest evidence, Prudentius’s Peristephanon, addresses the “Eighteen” martyrs of Zaragoza. These were said to have been martyred in a persecution that also saw the torture of individuals such as the virgin Engratia, a confessor saint whose injuries constituted a kind of “living martyrdom,” and the confessors Gaius and Crementius.Footnote 20 Prudentius tells us that the relics of the Eighteen consisted of a single urn of mingled ashes, held together as one in an extramural martyrium, at the beginning of the fifth century.Footnote 21 By the Visigothic period, we know that these ashes were held alongside Engratia’s relics in what Eugenius II of Toledo called “the basilica of the Eighteen.” An inscription, composed by Eugenius II for the site, enumerated the names of the Eighteen in a virtuoso feat of versification and described Engratia’s separate relics laying alongside those of the Eighteen.Footnote 22

By the central Middle Ages, however, Engratia had come to eclipse the other martyrs and confessors. In manuscripts of the Old Hispanic rite from the tenth and eleventh centuries, it is usually Engratia, rather than the Eighteen or the Innumerable, whose name leads the cult. The process by which this happened is opaque and hard to trace. It is evident, nonetheless, that when the Zaragozan martyrs’ relics, apparently lost during the period of Muslim rule, were rediscovered in the fourteenth century, the cult was framed as that of “Santa Engracia and the Santas Masas.” A grand Hieronymite monastery was founded in the fifteenth century over the cult site, where it controlled the memory of the martyrs until its destruction by Napoleonic forces in the early nineteenth century. The modern-day parochial basilica of Santa Engracia, built on the same site, retains this focus on Engratia in its vision of the cult.Footnote 23

The Visigothic Passion of the Innumerable is different. Its protagonist is not the Eighteen or Engratia but rather the whole, amorphous Christian crowd (agmina populorum, turba christianorum, or ueluti copia magnae multitudinis agnorum). In the Passion, every attempt is made to render the crowd of martyrs as a representative, diverse body of Christians. We are told that it encompassed people “from masters right down to slaves,” that it encompassed people old and young, and that both men and women were present.Footnote 24 Indeed, this group was so large and representative, “that you would believe that the whole multitude of the people of the city were departing entire for the spectacle of the raging sword.”Footnote 25 This is martyrdom articulated on a truly civic scale. Yet, the relationship between the Innumerable and the Eighteen is left strangely undetermined. The Eighteen were all said to be men, for example, while the Innumerable crowd was diverse and representative.Footnote 26 The Passion takes the cult of the Eighteen and pushes its rhetoric of abundance and copiousness to new heights, interpreting freely the situation in which the martyrs came to their deaths in order to assert an almost universal vision of martyrdom. Understanding this shift, which distinguishes the Visigothic Passion from evidence for the late Roman and high medieval cult, is our first task. Only once this is clarified can we turn to the immediate historical civic context in which the text belongs.

The content of the Passion of the Innumerable can be briefly summarized. It begins with an elevated, classicizing reflection on the contrast between ancient and Christian models of remembrance, chastising ancient heroes for the impermanence of their memorials in contrast to the eternity of the martyrs.Footnote 27 Next, the Passion establishes the historical context for its main events, which are situated within the spree of violence wrought by the persecuting governor Datian during the Diocletianic persecution.Footnote 28 Vincent of Zaragoza and Encratia receive passing mention, alongside a dutiful roll call of the names of the Eighteen, but the bulk of the Passion proper concerns the whole, undifferentiated Christian crowd of the city.Footnote 29 The narrative is very brief. Arriving at Zaragoza, Datian realizes that he cannot possibly defeat in open confrontation the “innumerable multitude of Christians contained in the ambit of the city.”Footnote 30 Accordingly, he hatches an underhanded plan to draw out the Christian community. A public announcement will lure the Christians to the extramural site of martyrdom. Once through the city gates, soldiers will emerge from hiding places to slaughter them. The scheme is narrated once in prospect, as Datian informs his men of the plan and once again as it happens.Footnote 31 After their death, Datian has the martyrs burned and mixes their ashes with those of criminals drawn from prison in an attempt to hinder the development of the cult.Footnote 32 Finally, the Passion opens out into a rhetorical final section that upbraids Datian for his futile efforts to destroy their cult while praising the exceptional fecundity of Zaragoza in producing martyrs.Footnote 33

As we have seen, the protagonist of the Passion is the whole Christian crowd, and yet the Passion lays claim to the heritage of the Eighteen and Engratia. This presents ambiguities. Consider the martyrs’ relics. The Eighteen were venerated as a mass of mingled ashes, held together in a single urn. In this, they were like the ashes of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste in Asia Minor, and the so-called “Massa candida” of Utica in North Africa, a group of three-hundred or so anonymous martyrs, whose bodies, Prudentius says, were destroyed together in a pit of quicklime. In fact, the Utica martyrs may have provided the inspiration behind the later use of the name “Sancta massa” for the Innumerable of Zaragoza.Footnote 34 Yet, the Passion of the Innumerable makes the further claim that Datian mingled the Innumerable’s ashes with the those of executed and cremated criminals, a crucial detail absent from Prudentius and the liturgical texts. Its function in the Passion is clear enough: it serves both to underline the martyrs’ imitation of Christ (in being mingled with criminals upon their execution, they imitated his death, flanked by convicts on the cross) and to emphasize their indivisible unity.Footnote 35 Yet, it is difficult to reconcile with what we know of the relics of the Eighteen. Was the Passion just engaged in a rhetorical play—a hyperbolic description of the existing relics of the Eighteen—or was it referring to a different set of relics preserved apart from the Eighteen and Engratia? The former is more likely, but we cannot be certain. The Passion does not try to reconcile the two ideas.

Other sources do more to complicate than to clarify matters. In a letter to the priest Iactatus, the seventh-century bishop Braulio of Zaragoza makes the remarkable claim that, while the cathedral church of Zaragoza has a large collection of relics, around seventy of which are in common use, his predecessors had removed all of their labels and placed them together in a single room, rendering them an unidentifiable mass. This had apparently been done to stop them being taken away by interested parties. Braulio was writing about the relics of the cathedral, not the basilica of the Eighteen, and he was responding to a request for apostolic relics, not those of local martyrs, but his account is illuminating and suggestive evidence for dislocation in the city’s wider relic cult.Footnote 36 It is possible that most of the city’s relics were, at some point, kept as a single, indistinguishable collection.

As we will see, part of the explanation for the difference between the Eighteen and the Innumerable lies in the fact that the Passion of the Innumerable derives from a novel celebration of the Zaragozan martyrs, which, initially at least, stood apart from the established celebration of the Eighteen and Engratia. Yet, the Passion laid claim to the latter, and it was the sole Passion used for them in medieval liturgical collections, even as Engratia rose to preeminence in the central Middle Ages. The Innumerable are best understood, then, as an augmentation of the specific cult of the Eighteen, taking the already existing rhetoric of abundance present in Prudentius to new rhetorical heights.

To help us to understand how the Eighteen and Innumerable could coexist, it is useful to compare the Passion to accounts of group martyrdoms found elsewhere. A tension between the individuality and group agency is visible throughout group martyr narratives. Early examples, such as the Passion of the second-century martyrs of Lyon and Vienne or the curt courtroom dialogues pertaining to the Scillitan martyrs in North Africa, tended to highlight the agency of individuals within the group.Footnote 37 There was, however, a tendency for the numbers in martyr cults to inflate over time, producing an ever-great number of less individualized “companions” to the main protagonists. Only a relatively small number of martyrs were named in the earliest account of the martyrs of Lyon and Vienne, for example, yet their number had risen to forty-eight by the time of Gregory of Tours (d. 594). Though he was able to enumerate their names individually, their relics were sometimes transmitted with labels referring simply to “the forty-eight martyrs.”Footnote 38 In other cases, cults embraced large-scale anonymity and reached extraordinary scales. A relic label from late sixth-century Rome refers to “St. Cornelius and many thousands of saints,” while a seventh- or eight-century example from the cathedral treasury of Sens attests a curiously precise “one-thousand-and-thirty martyrs.”Footnote 39 The latter may be the martyrs of Nicomedia in Asia Minor, a group who were already commemorated in seventh-century Jerusalem as a group of 1,000 or 1,003 (according to Georgian witnesses), before ballooning to a full 20,000 in their commemoration in tenth-century Constantinople.Footnote 40

The cult text that comes closest to the rhetoric of abundance expressed in the Passion of the Innumerable is, however, one somewhat closer to home, namely, that of the martyrs of Agaunum (Saint-Maurice, modern-day Switzerland). The probably legendary Passion written by Eucherius of Lyon (d. c. 449) leaned heavily on the sheer scale of their martyrdom (they were reportedly a military legion of 6,600 soldiers) while also drawing out six individual names for special commemoration.Footnote 41 Eucherius’s text might have influenced the author of the Passion of the Innumerable: both texts boast that their locale produced “so many thousands of martyrs,” in language suggestive of textual dependency, and both contrast this exceptional fecundity with the fate of those places that boast only a small number.Footnote 42 Though these parallels must be treated with caution, given that there is no evidence of the martyrs of Agaunum attracting cult in Hispania, they are nonetheless striking. Whether they indicate a direct dependency or show the independent development of cults that celebrated sheer quantity, they provide an invaluable parallel for the tension between abundance and specificity that marks the different framings of the Zaragozan martyrs.

With regard to the precise notion of “innumerability,” there is no need to seek a particular textual precursor, since the notion of the saints’ uncountable abundance appears throughout the hagiographical record. The Passion of Eulalia of Mérida, for example, opened by stating that “unnumberable (innumerus) is the people (populus) and infinite the multitude,” who faced cruel martyrdom through devotion to Christ.Footnote 43 Valerius of Bierzo wrote of “the bodies of innumerable saintly martyrs” distributed around the cities and provinces of the world.Footnote 44 The massed heavenly crowds revealed in visions of the beyond were also frequently “innumerable.”Footnote 45 Such language was simply part of the wider rhetoric of bountifulness that marked the hagiographical imaginaire.

That being said, there is one possible intertext that requires close consideration. This is the short text De laude Pampilone, contained in the famous Codex Rotense (Madrid, Real Academia de la Historia, MS 78, fols. 190r–190v), a manuscript written in Navarre around the year 1000.Footnote 46 Here, in a pair of texts purporting to derive from the time of the Roman emperor Honorius (384–423), we find imperial praise of the city of Pamplona, which claims that it is protected by the patronage of the “innumerable martyrs” granted to it by the Lord (Quam Dominus pro sua misericordia innumerauilium martirum reliquiarum condidit artem). We are told, furthermore, that the prayers of these martyrs aid the city, which is surrounded by hostile “barbarian peoples,” and that, even “if people remained silent” about the martyrs, “the stones would cry out.”Footnote 47 The latter claim is noteworthy, given that we do in fact find complete silence in the sources of the later Roman and Visigothic periods about the putative martyrs of Pamplona. Nonetheless, the evocation of “innumerable martyrs” is unusual enough to merit comparison with the texts from Zaragoza. In addition, the fact that it comes from a city in Tarraconensis, the same province as Zaragoza, makes a relationship between the two texts probable. It is most likely that the Pamplona text borrows from the Zaragozan rather than the other way round, but this remains to be demonstrated.

In the Codex Rotense, the words “De laude Pampilone” are given as the title for a sequence of two texts. The first is a letter from Honorius to soldiers stationed in Pamplona. This is widely regarded as an authentic (albeit rather corrupt) text dating to the early fifth century.Footnote 48 Following this is the praise of the city of Pamplona. If this, too, was an authentic late Roman text, it might follow that the Zaragozan cult was drawing on language already developed in Pamplona, a rival city in the competitive provincial world of Tarraconensis.Footnote 49 Certainly, it was common for emperors to send praises of cities they were addressing and to bolster their historical claims, as the Orcistus dossier from the reign of Constantine illustrates.Footnote 50 Nothing, then, excludes the authenticity of this text at first sight.

The authenticity of the praise text is, however, doubtful. Its first editor, José María Lacarra, suggested that it could be Visigothic, while subsequent scholars have often connected it with the formation and consolidation of the Kingdom of Navarre. The most recent discussion of the text is agnostic on its origin but argues for a terminus post quem in the seventh century on account of its confusion between the ethnic groups referred to the Vaccaei and Vascones, a conflation first attested in the writings of Isidore of Seville (d. 636).Footnote 51 Additionally, the complete lack of evidence for Pamplona’s martyrs in other sources should give us pause. This is not in itself a decisive argument. We know, for example, from Valerius of Bierzo that the city of León held (unnamed) martyrs’ relics, despite there being no other evidence for them in other sources.Footnote 52 Yet, in the case of Pamplona, it seems likely that its claims were simply copied from those of Zaragoza.

Especially indicative here is the idea presented in De laude Pampilone that the stones of the city would themselves proclaim the martyrs if human beings were to fall silent, since this echoes the idea (if not the precise language) of a passage in the Toledan Confession of Leocadia, which describes the persecution wrought by Datian in Zaragoza:

And afterwards he seized on most happy Zaragoza, like a lion gnashing at the teeth. If the human tongue would pass over in silence how many insults and blows were in that place—of how many tortures and how many effusions of blood had been carried out—the land itself, polluted with the blood of Christians, would speak, for there would be no excepted place which would not hold the revivified and most flourishing ashes of the martyrs in the site of cremation.Footnote 53

That De laude Pampilone echoes both the language of the cult of the Innumerable of Zaragoza and an idea expressed in the Confession of Leocadiae in a passage about Zaragoza strongly suggests that it is dependent on them and therefore has a terminus post quem in the seventh century.

Though De laude Pampilone is most likely not a precursor to the Passion of the Innumerable, it does point us to an important wider theme. Martyr cults were potent civic resources with consequences that could be political, economic, and social, as well as spiritual, and they were subject to competition and imitation. Other cities in Tarraconensis boasted their own prominent cults: Tarragona had Fructuosus, Augurius, and Eulogius; Girona had Felix; Calahorra had Emeterius and Celedonius; and Barcelona had Cucufas and Eulalia, the latter of whom was probably invented in imitation of Mérida’s homonymous patron.Footnote 54 Zaragoza was, of course, the home of one of the most long-established and widely known Iberian martyrs, Vincent.Footnote 55 Yet, Vincent’s actual martyrdom had occurred in Valencia, not Zaragoza, and his corporeal relics were held there, initially in an extramural martyrium and later, from the mid-sixth century, in the ecclesiastical complex established at the civic heart of the city, over the old Roman forum.Footnote 56 Zaragoza retained Vincent’s tunic, an important relic in its own right, and, according to Gregory of Tours, it was used in civic rituals, such as when it was paraded around the city walls in a penitential procession during a Frankish siege in 541.Footnote 57 Yet, the city’s claims on Vincent were hotly contested. In the fifth century, Prudentius referred repeatedly to Vincent as “ours,” meaning to connect him to his own region of Zaragoza, but a Visigothic sermon of the sixth century that made similar proprietorial claims has been connected convincingly to Valencia.Footnote 58

Amidst this crowded and competitive world, Zaragoza stood to benefit from cultivating its own, inalienable claim to a prestigious martyrial patronage. Sheer fecundity in the production of martyrs heightened this claim. It was certainly leveraged by Visigothic commentators on the city. Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies contains a glowing encomium of Zaragoza that includes the claim that it is “flourishing with the tombs of the holy martyrs.”Footnote 59 If, as is usually thought, Isidore’s literary executor Braulio of Zaragoza was responsible for this passage, this serves as an excellent illustration of the importance that such claims had for civic leaders and of the spread of such claims beyond the city. The special place allotted to Zaragoza’s sufferings in the historical preface to the Toledan Confession of Leocadia provides another seventh-century illustration.Footnote 60 That said, the cult of the Innumerable was, in this period, a fundamentally local cult. There is little to indicate its adoption by other cities or religious centers in Iberia or elsewhere. Thus, while civic competition is an important angle to consider, a more primary and fundamental concern is that of the social world of the city of Zaragoza itself. In fact, the Passion of the Innumerable provides a uniquely rich insight into the role of martyr cult in urban religiosity in the Visigothic period. It is to this that we now turn.

Nicenes, “Homoians,” and the Christian Crowd

Unusually for a martyr passion, we can be precise about the origins of the Visigothic redaction of the Passion of the Innumerable. It was written, in the first instance, for the celebration of a newly-consecrated church dedicated to the Zaragozan martyrs. This comes across clearly in the Passion’s closing section, when the preacher, having mocked the futility of the persecutor Datian’s attempts to destroy the martyrs, mentions as a final insult to him the consecration of a site of cult:

At last, we have consecrated to the Lord almighty a temple (aula) in their [the martyrs’] honor, so that the Christian people, dancing joyously, might not cease to come together in festivities and delights for those whose name your ferocity tried to extirpate entirely.Footnote 61

On its own, this reference to a newly consecrated aula is non-specific and might even be thought to refer to the original late Roman martyrium. But, as André Lambert long ago argued, the text of a mass prayer for the martyrs gives us a strong reason to believe that the consecration was, in fact, a Nicene reconsecration occurring after the Visigothic abjuration of Homoian belief (that is, the Christological doctrine that its Nicene “Catholic” opponents called “Arianism”).Footnote 62

The reasons are as follows. The mass prayer opens with a condemnation of what it describes, somewhat circuitously, as “Gothic ‘paganism’, as if under the faith” (gothica quasi sub fide gentilitas). This is clearly meant to refer to Visigothic Homoianism, although neither the word “Arian” nor “heresy” is openly deployed. Rather, the mass prayer assimilates Christological unorthodoxy to “gentility,” that is, to the “pagan-ness” that was central to the world of the martyr passions, and regards it as, at best, quasi-Christian. The text goes on to speak of the Gothic conversion from false to true faith in terms that can only refer to the events in and around the Third Council of Toledo of 589, the council at which the Visigoths, under Reccared (r. 586–601), officially abjured Homoianism and accepted the Nicene confession:

The faith of that people was, indeed, feigned then, but is now steadfast; it was then false, now true; then corrupt, now pure; and the one who held to error, with the diminishment of division, now exhibits completeness, with the distinction of the names of unity.Footnote 63

The mass prayer, like the Passion, is preserved only in later manuscripts, in this case dating to the eleventh century at the earliest. Yet, internal evidence indicates that the opening sections of the mass prayer were composed in the wake of Visigothic conversion. Its references, which are not entirely explicit, could hardly be understood otherwise. Moreover, the text was evidently written for a local audience. The mass prayer refers to nostra Cesaraugusta when comparing the city’s martyrial riches to Rome and expresses the need to caution against the idea that “our” praise of the martyrs’ beneficence for the city comes merely from vainglory or vanity.Footnote 64 Both the mass prayer and the Passion, it would seem, reflect the fallout from recent Visigothic confessional conflict.

Religious conflict became a prominent part of Visigothic political and ecclesiastical life only in the 580s, when King Leovigild (r. 569–586) worked to promote his confessional position more assertively across the kingdom.Footnote 65 He organized a Homoian council, modified elements of Homoian practice (for example, relaxing the requirement that Nicene Christians be rebaptized if they are to convert), and sought high profile converts. Of these, the most famous was Vincent, bishop of Zaragoza.Footnote 66 Although Isidore of Seville records Vincent’s decision to accept Leovigild’s position we know little of the events set in motion in Zaragoza itself, and the lack of a narrative source like the Lives of the Fathers of Mérida renders the course of the city’s confessional conflict hard to reconstruct. That said, it is clear from the Méridan text that Homoian bishops sought to take in hand formerly Nicene places of worship and, crucially, relics. In Mérida, Eulalia’s tunic was the locus of competition; Leovigild himself attempted to appropriate it for the royal city of Toledo.Footnote 67 We know less about Zaragoza, and, as a city with a convert bishop rather than an imposed Homoian alternative, its dynamics may have been different from Mérida’s. It is certainly likely, however, that confessional conflict had an impact on local martyr cults.

More is known about the period that followed Visigothic conversion. The consequences of the Third Council of Toledo had to be worked out in the provinces. Thus, in 592 the provincial Second Council of Zaragoza gathered fourteen bishops and their representatives from across the province of Tarraconensis to address problems that had emerged in the wake of Visigothic conversion. The brief canons tell us that the bishops discussed the integration of formerly Homoian clergy into the Nicene fold, the reconsecration of formerly Homoian churches, and the testing (that is, trial by fire) of relics held at these formerly Homoian sites.Footnote 68 The absence of the recently-converted bishop Ugnas of Barcelona from proceedings may suggest ongoing tensions between the old Nicene episcopate and formerly Homoian bishops.Footnote 69 It is in relation to this period of transition around 592 that the “consecration” mentioned in the Passion should be understood. It refers to a reconsecration performed in the wake of the Second Council of Zaragoza in 592.

The reconsecration seems to have been celebrated separately to the main feast day of the Zaragozan martyrs. This explains the puzzling divergence in the feast days recorded in different sources.Footnote 70 The Eighteen were traditionally commemorated around Easter, as the unanimous witness of the Frankish and Iberian calendars tells us. These typically give dates of either 15 or (more often) 16 April for their feast day, although it seems that it was initially a moveable feast, placed on the Wednesday of Easter week, as is explained by the calendar that appears among the introductory folios of the tenth-century León Antiphoner.Footnote 71 If so, this made it the only moveable martyr’s feast in the Old Hispanic liturgy.Footnote 72 The earliest texts of the Passion, however, pertain to a different celebration on 3 November. This is the date given in the earliest manuscript (a ninth-century copy of the Carolingian redaction). The Iberian texts of the Passion tend to lack liturgical dates, but our earliest witness—the tenth-century Cardeña text—carries the Passion in a place consistent with a November date.Footnote 73 The other tenth-century text lacks the folios which covered this part of the liturgical year, but it contains a text of the Passion in an eleventh-century interpolation, which places it among those intended for April and May celebrations. Oddly, this is the only Iberian witness to provide an explicit liturgical date, and it gives 3 November in contradiction to its interpolated position.Footnote 74 It was presumably either cut or copied from a collection that placed it in November, before being reused for the differently-oriented cult in the eleventh century. Others place the Passion in April. This speaks of lingering uncertainty over the divergent dates in tenth- and eleventh-century Iberia. Their status vis-à-vis one another was not settled in the early or central Middle Ages.

The simplest way to resolve the divergence is to suggest that there were two distinct cults in operation: a longstanding and widespread Easter cult for the Eighteen and Engratia, and a separate November cult for the Innumerable, the latter created for local use on the occasion of the reconsecration. The Carolingian monk Usuard, who encountered the cult and its Passion text when travelling through Zaragoza in the mid-ninth century, seems to have considered them to be two different, complimentary feast days. Incorporating new information into his Martyrology, which built on Frankish exemplars, he not only updated an existing entry for 16 April on the Eighteen, based on Prudentius, but also added a new, separate entry for 3 November on “the innumerable holy martyrs of Zaragoza,” who suffered under Datian, using novel information from the Passion. Footnote 75 The Innumerable cannot be so straightforwardly distinguished from the Eighteen, however. It remains the case that there is no trace of any separate Passion text for the Eighteen or indeed for Engratia, despite her already being the preeminent figure for the April feast day at the time of the earliest Iberian liturgical and calendrical manuscripts. It is always the Passion of the Innumerable that appears in the medieval manuscripts. Although it seems likely, then, that our extant Passion derives from a novel November feast day held in celebration of the reconsecration, it was not only a text of local significance. Rather, it channeled the wider Zaragozan tradition through its framing of the cult and became the sole martyr passion used for all the martyrs on both sides of the Pyrenees, even when Engratia emerged as the central figure. It must therefore be regarded as a recasting of the same cult.

What did this novel framing of the cult express to its local audience? To answer this, we first have to attend to the context in which it was read out. We know from external evidence that the liturgical reading of martyr passions and other hagiographies during the mass was well established by Visigothic period. It had long been common practice in North Africa, as is evident from Augustine’s numerous sermons on saints, and in late antique Gaul, though the practice was notably not accepted in Rome or (under Roman influence) in the Carolingian world.Footnote 76 In Hispania, our best evidence for the practice comes from Zaragoza itself. In the prologue to the Life of Aemilian, a hagiography about a sixth-century hermit saint, Braulio of Zaragoza specified that the text should be read at the saint’s mass. He noted, moreover, that in order to accommodate this he had written it in “plain and open” style and decided not to compose a sermon so as to avoid the service becoming overlong.Footnote 77 Braulio was writing about a monastic confessor saint but he does not give the impression that he is suggesting anything unusual, thus implying that it was standard practice for the much more numerous passions. This is to speak only of the Visigothic period. Marginal notes in later manuscripts suggest that by the tenth century, at least, passions were more often read at matutinum, the Old Hispanic liturgy’s pre-dawn service, than they were at mass.Footnote 78 But this does not negate the Visigothic evidence. That Braulio’s Life of Aemilian was divided up into lections for matutinum in the eleventh century, for example, shows only that later monastic copyists were happy to adapt old texts to new practices.Footnote 79 Evidence contemporary to the Visigothic kingdom records that passions were read at mass, when the broadest audience would be present.

Certainly, the Passion seems to presume a wide, civic audience. It closes with a rich laus urbis, aimed squarely at edifying and inspiring its local constituency. Rhetorically addressing the city itself, the preacher exclaims:

O fortunate city—and fortunate beyond measure! —Zaragoza, anointed (circumlita) with the blood of the blessed ones, you have consecrated to the omnipotent Lord the gifts of so many thousands of martyrs! Let all the cities of the world rejoice with you, then, decorated with the precious blood of the martyrs! … And, indeed, let that head of peoples/gentiles (caput gentium), most noble of cities, golden Rome, who with two consuls of Christ, namely the great holy apostles Peter and Paul, bears the sweet, growing rose fragrance of innumerable martyrs!Footnote 80 Let also the multitude of the regions of all Spania rejoice with us, bearing with themselves the dignity of the Christian name!Footnote 81

It is in this passage, and the wider laus urbis of which it is a part, that we can begin to see how the text aims to engage with and understand its intended audience among the Christian community of the city.

Before doing so, however, it is useful to draw out some of the intertexts contained in this important passage, since they help us clarify and situate the message the author was projecting to its audience. The appeal to Rome as “ipsa caput gentium, nobilissima urbium, aurea Roma” is especially illuminating.Footnote 82 A great deal is contained in this curious locution. Historians have previously noted a parallel passage in Isidore’s In Praise of Spain, the preface to his History of the Goths, where the Goths are described as coveting “golden Rome, head of the peoples” (aurea Roma caput gentium).Footnote 83 There is in fact another, hitherto unexplored, Isidorian intertext earlier in the same section of the Passion, namely, its invocation “O fortunate city—and fortunate beyond measure! —Zaragoza” (O felix et nimium felix ciuitas Cesaragusta), which parallels Isidore’s claim in De uiris illustribus that anyone who could say they had read all of Gregory the Great’s works would be “fortunate, however, and fortunate beyond measure” (Felix tamen et nimium felix).Footnote 84 Drawing only on the first intertext, Luis García Moreno argued that the Passion must have been a seventh-century production dependent on Isidore.Footnote 85 This need not be the case, however. As Thomas Deswarte has rightly noted, there is no need to presume Isidore’s priority.Footnote 86 In fact, as I will show, both passages can be traced back to earlier sources, which were just as likely to be picked up first by our anonymous Zaragozan writer as by the Sevillan bishop.

The phrase Felix et nimium felix is easily explained. It derives from a speech that Virgil placed into Dido’s mouth at the moment in which she is about to die by her own hand in the fourth book of the Aeneid. Footnote 87 It does not strain belief to think that our Zaragozan author, whose classicizing tone is evident in the preface to the Passion, knew this famous text, and there is accordingly no need to presume dependence on Isidore. The phrase caput gentium is more complex and demands more exposition, but it brings us to the same conclusion. This phrase is not just a simple reworking of the traditional notion of Rome as caput mundi or caput orbis, refracted through an early medieval tendency to see the world as a collection of gentes, as has been suggested by recent commentators on Isidore.Footnote 88 Rather, it was a notion that, in the Passion, recalled a specifically Biblical intertext, namely Psalm 17:44 (18:43): “You have delivered me from the strivings of the people, and you have made me the head of the gentiles (caput gentium).” More specifically, it reflected the use to which Augustine put this verse in a sermon on the Roman martyrs and apostles Peter and Paul. Unpacking this reference tells us a great deal about the geographical imaginary of the Passion’s author and the way they invoked a vision of orthodox universality.

To understand the phrase caput gentium, we need first to return to the Psalmic verse quoted above. As Gerda Heydemann has reminded us, early medieval thought on ethnicity was as informed by the Bible as by Roman ethnography, and the word gentes in texts of the era as often means “gentiles” as it does “peoples.”Footnote 89 The verse was routinely interpreted in patristic exegesis as a prophesy to be read in Christ’s own voice, wherein he predicted the supersession of the Jews (the former chosen people of God) by the gentes. Christ was heralding the emergence of the “gentile church,” in which he, as the ecclesia’s head, would become caput gentium. This reading is attested in Augustine, Cassiodorus, and Isidore, among others, and had a particular importance in anti-Jewish Christian writings on the Old Testament.Footnote 90

It is in Augustine’s work, however, that we see the passage explicitly placed into dialogue with traditional ideas of Rome. In City of God, Augustine noted that it was the apostles, taking Christ’s message to the many peoples of the world, who truly rendered him caput gentium. Footnote 91 Among these, Peter and Paul stood out. By taking the evangelical message to Rome, they conquered the symbolic center of the worldly empire for Christianity. Thus, in a sermon preached ad populum on the feast day of the apostles Peter and Paul, Augustine praised Rome for its twin martyr-apostles, saying, “Thus, Rome, head of the gentiles (caput gentium), holds two lights of the gentiles, lit by him who ‘illuminated every person coming into this world’.”Footnote 92 This is the crucial intertext for the Passion of the Innumerable’s use of the phrase. All the elements are present: the Psalmic caput gentium is attached to the earthly city of Rome in the manner of caput mundi, and this is done so in the context of praising Peter and Paul, the city’s apostolic patrons.

This helps us understand what is being said in the Zaragozan context. Rome is not just appealed to for its former imperial glory or even as the site of particularly important martyrs and cults. Nor is it invoked as an ecclesiastical center (indeed, the Visigothic church was somewhat estranged from papal power).Footnote 93 Rather, Rome serves as the symbolic center of the universal “gentile church” founded by the evangelical conquest of Rome by Christ’s apostles. This was a notion that found liturgical expression in Hispania and elsewhere, particularly in liturgy on Peter and Paul.Footnote 94 Just as Rome once subjugated the gentes to its apparently universal imperial authority, so too has the Christian church subdued and incorporated the gentes, in both senses of the word.

Our Iberian preacher’s appropriation of the phrase is particularly interesting in light of the alternative visions of Christian community presented at the Third Council of Toledo only a few years earlier. Here, at this grand royal-sponsored convocation, the theme of the “calling of the gentiles” was certainly present, but the accent was very much on the specific importance of the gens Gothorum. Footnote 95 Leander of Seville, by contrast, allotted no special place to the Goths in the sermon that he preached on the calling of the various gentes to the universal ecclesia. Footnote 96 Leander’s brother Isidore, however, continued the pro-Gothic line of political theology in his historical writings, composed in the earlier seventh century.Footnote 97 Indeed, Isidore’s use of the phrase caput gentium in the History of the Goths was in precisely this vein, positioning the Goths as conquerors and legitimate heirs to the imperial power of Rome. Perhaps Isidore, who knew well the anti-Jewish use of the Psalmic verse, intended an echo of supersessionist ideology here: the Goths superseded Rome in the government of Hispania just as the gentes superseded Israel in God’s salvific plan.Footnote 98 Either way, this shows a very different sensibility to the author of the Passion of the Innumerable, whose appeal to a Romanizing vision of universality omitted any special place for the Goths. It seems most plausible, then, that the Zaragozan author of the Passion was making use of Augustine’s sermon on Peter and Paul directly rather than drawing on Isidore.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that the median audience member would have understood these wider political resonances, still less the Virgilian intertext. There is, however, much to be said about the way in which the text sought to engage with its audience. Its message was one of civic pride, and its archaizing imperial imaginaire was part of this. This would have been apparent even without knowledge of the precise intertexts adduced above. The Passion’s main pastoral message, however, was less about Zaragoza’s place within a wider constellation of cities than about the assertion of Christian unity and harmony within Zaragoza itself. Most fundamentally, the Passion used the Innumerable to elaborate an ideological vision of civic unanimity, which overrode internal conflict and difference. This must be understood as an intervention into the deeply riven world of post-Homoian Zaragoza, when the wounds of confessional conflict were still fresh. The Passion’s rhetoric of unity and its attempt to bind the Christian community in celebration of the city’s exceptionally fecund martyrial tradition can be read both as efforts to construct a new vision of community and subtly polemical ways of laying claim to the contested heritage of the cult after a period of Homoian possession.

This was accomplished through a language of civic unanimity, which had long pervaded martyrial literature. Writing of the cult of Hippolytus in the city of Rome, Prudentius had claimed that “the love of their religion masses Latins and strangers together in one general body,” and that “with equal ardor patricians and plebian host are jumbled together shoulder to shoulder, for the faith banishes distinctions of birth.”Footnote 99 Similar imagery appears in the Visigothic passions. Thus, the Passion of Eulalia of Mérida described its protagonist entering the city’s forum as a kind of adventus, witnessed publicly by the entire city:

But blessed Eulalia, filled with faith, came to the forum of her own volition. Then the rumor ran through the areas neighboring the forum and there assembled an innumerable crowd, vast beyond measure, so much so that no one remained in their house. For so great was the fame holy Eulalia’s purity and countenance, that all the inhabitants of the city of Mérida came together for the arrival (aduentus) of blessed Eulalia, that, absorbed in love of her, they might see the young slave girl (uernula), and senator (senatrix) and inhabitant of that province contending with the governor.Footnote 100

In all of these cases, as in countless others, the Christian crowd was a positive, legitimizing presence.Footnote 101 As Shane Bobrycki has recently shown, post-Roman Christian crowds were, in contrast to the frequently feared and despised crowds of the Roman elite imagination, typically presented as positive, ordered evocations of the social hierarchy, witnessing and legitimizing the power of the holy bishop or the saint.Footnote 102 The crowds of the Iberian martyr passions are no exception.

Hagiographical discussions of crowds often encouraged their present-day audiences to identify themselves with the crowds of the Roman past. In this, the ancient crowd, who witnessed the martyrs’ suffering, was held up as a model for present-day crowd, who bore witness in their observance of saints’ days.Footnote 103 Yet, as we have seen, in the Passion of the Innumerable the logic of identification is somewhat different since the ancient crowd is not just spectator but protagonist. This fact allows the present-day crowd to identify much more directly with the ancient martyrs. Twice the audience is instructed that to join themselves with the martyrs by “suffering with” (compatior) them:

Let the organs of our hearts resound with melodious voices, so that—while we join ourselves to them by suffering the same afflictions along with them—we might, by their prayers and with Christ the Lord helping, be worthy to be associate with them in the eternal dwelling-places.Footnote 104

And again:

Behold! Seeing the ashes of the Innumerable holy martyrs with our own eyes, let us venerate them with the greatest exultation; and, joyful in their triumphs, let us be joined with them by suffering with them.Footnote 105

This was, of course, not intended as a spur to martyrdom in the present (violence is rather toned down in the text) but to convey instead a sense of affective harmony linking the crowd and the ancient martyrs in sympathy across the centuries.Footnote 106

A further way in which the Passion articulated a link between past and present crowds was through its depiction of communal liturgical forms. In the Passion, the martyrs are depicted as if they are already partaking in their own civic celebration. There is an unusually festive atmosphere, foregrounding the imagery of communal joy over the austere accomplishments of martyrial fortitude.Footnote 107 The crowd of martyrs process through the city streets to their martyrdom, joining together in singing Luke 2:14: “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will for all men”.Footnote 108 In this, they paralleled those other martyrs whose steadfastness before their ordeals saw them joyfully chant songs of praise to God as they approached death.Footnote 109 More importantly, however, they served to prefigure the celebrations of the present-day Christian crowd who constituted the Passion’s audience. The feast days of martyrs involved communal singing, which is evident from several surviving hymns datable to the Visigothic period, as did liturgical life more generally.Footnote 110 The Lives of the Fathers of Mérida, for example, describe the custom of the church of Mérida on Easter Sundays, whereby the bishop and Christian community processed from the cathedral after mass to the extramural martyrial church of Eulalia, singing as they went.Footnote 111 The joyful, singing crowd of the Passion therefore anticipated the present-day celebrations of the Christian audience, creating an affective link across the centuries.

The final way in which the martyrs and the present-day Christian crowd were linked was through the idea of sacrifice. The Passion delights in a sacrificial inversion. While the persecuting governor Datian was supposed to be forcing Christians to offer sacrifices to the Roman gods, he was, in fact, acting as an unwitting priest, dedicating Christian martyrs as sacrifices to their own God and rendering them future patrons of their cities:

But by the providence of the almighty Lord, it happened that, for the adornment and patronage of several cities, he [Datian], with his sacrilegious spirit, dedicated to Christ the Lord sacrosanct sacrifices, through the intercession of which assistance is often given to the citizens, by the Lord’s grace.Footnote 112

In framing the martyrs as civic sacrifices, the Passion followed a tradition with deep roots. Many of the earliest martyr texts, drawing especially on strands of Jewish thought, understood martyrdom in a sacrificial, quasi-liturgical light.Footnote 113 In some passions, the martyrs themselves described their activity in this way. Eulalia of Mérida, to pick just one example, says to the governor, “I will offer a living sacrifice to my Lord, offering myself to him just as he has been offered for me, that he might liberate us from the power of darkness and the devil’s imperium.”Footnote 114 The idea of martyrs as sacrifices also drew on the inheritance of Roman civic religion, where sacrifices were public acts performed on behalf of a given citizenry.Footnote 115 This stands out in the passage quoted above, in which the martyrs’ sacrifices are said to furnish cities with intercessors who act as patrons for their citizens.Footnote 116 In this way, the martyrs were thought to be bound to the city and its community through being consecrated as sacrifices on its behalf.

The Passion should not only be seen in the light of the apparently inclusive, unifying ideals of civic religion, however. The text also intervened, with a light touch, in a context marked by bitter confessional strife, and its rhetoric of unity can only be adequately understood against this background. It is notable that the Passion, like the mass prayers, never directly speaks of “Arians” or “heretics.” In fact, it demonstrates less explicit anxiety about Trinitarian thought than many other Visigothic passions, several of which put statements of orthodox Trinitarian doctrine into their protagonists’ mouths for pedagogical and, perhaps, polemical reasons.Footnote 117 That said, we can still detect allusions to matters of doctrinal orthodoxy in the Passion. The text makes clear that only Christians of the right confession can join with Zaragoza’s bonanza of saints, for it is the “unity of the holy catholic faith” that “associates us with the merits of the present holy martyrs.”Footnote 118 This was a subtly exclusive vision of unity, appealing to a wider Christian world to bolster the claims of local Nicenes against those they considered “Arian” heretics. There were doubtless people present in Zaragoza whom such a vision was meant to exclude.

This was an understated message, but one which would have been legible in a recently riven city. The martyrs were enrolled in the service of a vision of universality identified with Rome and founded on orthodoxy. Zaragozans could be proud of their special relationship to their local martyrs, but only if they were correctly orientated within a wider, doctrinally pure community defined by its catholicity. The Passion used the martyrs to assert civic harmony, overlaying a divided city with the image of a common history, common patrons, and a common civic life. This is not to say that these appeals to unity had their desired effect. Santiago Castellanos has justly characterized the unanimous crowds of hagiography as representative of an “ideological screen” placed over the complex realities of society by their elite authors.Footnote 119 Nonetheless, the very fact that a preacher presented such a text to the people of the city is an important historical datum in its own right. It helps to provide an explanation for the unusual choice to render the Christian crowd the protagonist of the Passion and to sideline Engratia and other individuals. In the face of division, the Passion reimagined the city’s martyrs as a pious, harmonious civic group whose example could be held up as a model for the present.

Cult and Monastery in Visigothic Zaragoza

Thus far, we have contextualized the Passion entirely in the context of public preaching. What of the role of the putative monastery that guarded the saints’ relics? The evidence for this is, in fact, sparse in the extreme. We know that Zaragoza had at least one monastery in its environs, and that this had a close relationship with the episcopate. John, the elder brother and episcopal predecessor of Braulio of Zaragoza, was “a father to monks” (pater monachorum) before he served as the city’s bishop, as was Braulio’s successor Taio.Footnote 120 At the Thirteenth Council of Toledo in 683, Zaragoza was represented by the abbot Fredebadus as a stand-in for the bishop.Footnote 121 In none of these cases, however, is the identity of the monastery given. We have no reason to assume that these references pertain to the same monastery, still less that this monastery was at the site of the relics of Engratia and the Eighteen. Historians, however, remain prone to interpret all references to monasticism in Zaragoza in the light of the putative monastery of these martyrs.Footnote 122 André Lambert, in particular, framed his whole discussion of the Visigothic Passion within a (highly conjectural) account of monastic history in the Iberian north-east.Footnote 123

Historians’ over-interpretation of the evidence rests, however implicitly, on a weight of tradition that derives from the early modern Hieronymite monastery of Santa Engracia and the Santas Masas. Constructed under Aragonese royal patronage in the last decade of the fifteenth century, the monastery laid claim to the cult for over three centuries before it was razed to the ground in the Napoleonic siege of the city.Footnote 124 Its monks produced voluminous scholarship arguing, among other things, that the monastery’s crypt, in which apparent relics of Engratia and the Santas Masas had been rediscovered in the fourteenth century, was continuous with the Roman cult site, and that the cult site had been monastic in character ever since the time of Paulinus of Nola.Footnote 125 The crypt, which survives today under the nineteenth-century parochial church, contains late Roman sarcophagi, which have traditionally been identified with those uncovered in the inventio. It is far from clear that they are identical with these, however, since a great deal was destroyed in the Napoleonic attack. Critical modern scholarship has remained prudently agnostic on the links between the crypt, the sarcophagi, and the historic cult site.Footnote 126 None of this would prove monastic continuity either way, even if continuity in the location of the cult site could be established. We do better to extricate our analysis from the paradigms developed by apologists from the Hieronymite monastery and to investigate the cult from strictly contemporary evidence.

The strongest evidence for a monastery at the cult site of the Zaragozan martyrs is found in Ildefonsus’s account of Eugenius II of Toledo’s life, although it remains ambiguous. Ildefonsus tells us that Eugenius first served as a cleric in Toledo before desiring to live the life of a monk. Accordingly, he fled to Zaragoza, where he pursued the lifestyle of a monk (propositum monachi) at the “sepulcher of the martyrs.” After some time, he was drawn back to Toledo at the urging of King Chindasuinth (r. 642–653) to become the metropolitan bishop of the royal see.Footnote 127 The “sepulcher of the martyrs” in Zaragoza could indeed have been that of Engratia and the Eighteen, as most historians have presumed, but this is not said explicitly and elsewhere Braulio mentions Eugenius’s service as an archdeacon in the basilica of the martyr Vincent.Footnote 128 For his part, Eugenius wrote verse inscriptions for the martyrial basilicas of both the Eighteen and Vincent. He may have been involved with both at different times, but in neither case does he refer to monastic life.Footnote 129 By contrast, his dedicatory poem for a lay-founded basilica dedicated to the martyr Felix does make special mention of a monastic community based there.Footnote 130

Beyond Ildefonsus’s remarks, all we know for certain about Eugenius’s time in Zaragoza comes from Braulio’s correspondence, in which Eugenius appears exclusively as a deacon or archdeacon. This clerical ascription need not contradict Ildefonsus’s account of Eugenius’s monastic vocation, but it should affect how we interpret it. Evidently, one could be both a monk and a deacon. The author of the Lives of the Fathers of Mérida (or at least its first three books) described himself as a “deacon of Christ” (levita Christi) living under an abbot.Footnote 131 Certainly Braulio himself sometimes ordained monks. In a tense letter written to a bishop Wiligildus of an unknown see, Braulio was forced to apologize for taking in a monk who had fled a monastery in the latter’s diocese and for subsequently ordaining him as a subdeacon in Zaragoza contrary to canonical stipulations.Footnote 132 The parallel here is not exact. Eugenius was not a wandering monk; he was fleeing clerical office for a monastic life, which was in some cases a canonically approved course of action.Footnote 133 It remains significant, however, that Braulio always positions Eugenius as a cleric and that Braulio was known to employ monastics as clerics.

How, then, are we to understand Eugenius’s monastic vocation? With little evidence for the Zaragozan site, we need to appeal to comparative evidence. The case of Mérida’s extramural cult site for Eulalia provides the clearest Iberian parallel. There were certainly both male and female religious monasteries dedicated to Eulalia, but it is not clear that either was coterminous with the cult site.Footnote 134 Indeed, when the Lives of the Fathers of Mérida does make explicit mention of the extramural martyrial basilica of Eulalia, the monastic life it describes is focused on single cells. Thus, we hear of a solitary African monk, Nanctus, who stayed in a cell close by to the basilica of Eulalia for a period of time before becoming a recluse in a more remote part of Hispania. In this story, the basilica and cells are overseen by a deacon and seem to have been available to passing ascetics for short stays.Footnote 135 The bishop of Mérida, Paul, retired to the same kind of cell shortly before his death.Footnote 136 This implies a relatively informal, loose organization at the cult site.

Frankish evidence also provides a valuable comparative perspective. French scholars of Merovingian martyr cult have developed the category of the “martyrial basilica” in order to make sense of the frequent references in the writing of Gregory of Tours and others to abbots who served in such institutions.Footnote 137 Martyrial basilicas were urban or suburban basilicas with attached communities of clerics or monastics operating under an abbot or other superior, whose work was chiefly directed at the maintenance of public martyr cult. These are not monasteries in the cloistered, coenobitic model, set apart from the city and its clerical hierarchy. Indeed, as Hélène Noizet has emphasized, they were largely integrated into diocesan structures and functioned in an outward-facing way, overseeing and administering large public cults, which attracted visitors and were integrated into the liturgical life of the city.Footnote 138 According to this model, we could imagine the monastic life present at the Zaragozan site as one consisting of clerics and monastics living a communal life in service of the public cult of the martyrs. A structure of this kind may explain how Eugenius was able to pursue a monastic vocation at the tomb of the martyrs while also serving as a cleric.

In summary, the evidence for monastic life at the tomb of the Zaragozan martyrs is very thin. There might well have been monastics attached to the cult site, but these probably served in the public side of the cult in the manner of those at martyrial basilicas in Gaul. None of this detracts from the analysis of the Passion of the Innumerable as a work of civic preaching elaborated above. The ‘monastic’ and the ‘civic’ were not diametrically opposed: monastics could plausibly play a role in civic cult without thereby ‘monasticizing’ a cult or alienating it from its origins. Yet, it remains important to recognize that the Visigothic cult of the Zaragozan martyrs was not dominated by a monastery in the way it would be from the fifteenth century onwards. For the Passion’s earliest secure connection to monastic life, we have to look beyond the Iberian Peninsula to the Carolingian north.

The Carolingian Redaction

Saint-Germain-des-Prés and Zaragoza

As far as we know, the Passion of the Innumerable first crossed the Pyrenees in the second half of the ninth century when it was taken by the monks Usuard and Odilard to the Parisian monastery of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.Footnote 139 Unlike the Passions of Fructuosus, Augurius, and Eulogius of Tarragona, Vincent of Zaragoza, and Eulalia of Mérida, which already circulated outside of the Peninsula in late antiquity and appeared in Carolingian hagiographical collections in the eighth and ninth centuries, the Passion of the Innumerable depended entirely on these Parisian monks’ journey into al-Andalus for its northward spread.Footnote 140 The anonymous early ninth-century martyrologist of Lyon, for example, knew Prudentius’s account of the Eighteen but did not know the Passion of the Innumerable, while the grand “Legendary of Moissac,” produced in Aquitaine around the year 1000, did not include the Passion among its ten Iberian passions.Footnote 141 It was from Saint-Germain in the Frankish north that the Passion disseminated in Francia, and it was here that the distinctive Carolingian redaction was made in the second half of the ninth century.Footnote 142 This text has been little studied, however, and no critical edition exists. Fine-grained analysis is required to clarify its relation to the Iberian redaction. By comparing the two versions, we can better see how certain interventionist monastic lines of transmission altered received texts. This makes the conservatism of the Iberian lines stand out all the more strongly.

First, it is useful to clarify the long history of contacts between Saint-Germain-des-Prés and Iberian martyr cults. The eighth-century history known to modern scholars as the Liber historiae Francorum says that the monastery was founded in the sixth century by Childebert I (r. 511–558) after relics of Vincent were taken from Zaragoza following a Frankish siege.Footnote 143 Whether or not this origin story is true—and there are reasons to question it—the monastery of Saint-Germain-des-Prés certainly did nurture a close interest in his cult.Footnote 144 By the time Usuard and Odilard crossed the Pyrenees around 857, the tradition was already long established that Childebert had received relics of Vincent’s after the siege.Footnote 145 The monks set off in search of the relics of Vincent’s body, historically held in Valencia, but soon discovered that they had been translated. Upon hearing of the new martyrs of Umayyad Córdoba, they contented themselves with the relics and Passion of George, Aurelius, and Nathalie. These they acquired in Córdoba itself, where they met several local clerics and monastics. Crucially, for our purposes, they took a somewhat circuitous route, which took them through Zaragoza, where diplomatic contacts smoothed their passage through the Muslim territories.Footnote 146

Little is known about the state of the cult of the Innumerable (or indeed of Engratia) in the ninth century. In 714, the city was conquered by Arab and Berber troops through force of arms rather than by negotiated treaty, leading the Christian Chronicle of 754 to remember Zaragoza as an “ancient and once flourishing city … which was now, by the judgment of God, openly exposed to the sword, famine, and captivity.”Footnote 147 Yet, the city went on to flourish under Umayyad government and, as the administrative center of the northernmost region of the new polity, it enjoyed clear pre-eminence over the former regional capital of Tarragona.Footnote 148 Charlemagne’s attempt to conquer the city was a decisive failure, meaning that Muslim control was assured thereafter until the twelfth century.Footnote 149 Usuard and Odilard encountered an eminent Umayyad city, then, which had been under Muslim control for almost a century and half. Zaragoza did retain a Christian community, however. An intriguing letter from the priest Evantius of Toledo on ‘Judaizing’ Christians, written around 731, demonstrates continuity in the communal Christian life in the city in the eighth century (and in clerical anxieties over apparently ‘Judaizing’ practices).Footnote 150 We have no evidence for the development of the cult of the ‘Innumerable’ in this period, besides a single, probably forged, charter of 985 attesting a church dedicated to the Sanctas Massas (among others), but it is probably safe to assume that Usuard and Odilard encountered a still functioning cult.Footnote 151

During their journey they accrued a large amount of information about the Iberian martyrs, both from Eulogius’s testimony and from liturgical and calendrical texts. The fruit of this investigation is evident in Usuard’s later Martyrology. Footnote 152 The pair evidently collected many texts during their journey. Several more were composed or recomposed afterwards, including a new, much-augmented redaction of the Passion of Vincent, and a Translation accounting for his relics’ journey to Castres. In addition, there was a further Translation composed by the monk Aimon for the relics of George, Aurelius, and Nathalie. This story is well known.Footnote 153 What is important to note here, however, is that the manuscript which contains these varied items of Vincentiana, a Saint-Germain manuscript of the later ninth century (now Paris, BnF, Latin 13760), is also the first to attest the Carolingian redaction of the Passion of the Innumerable of Zaragoza. Indeed, it provides the earliest text of any redaction of the Passion. Crucially, it also contains the earliest copy of another sermon on Vincent known as Cunctorum licet, the significance of which will become apparent shortly.

The Carolingian redaction of the Passion of the Innumerable is not radically different, but it pays to compare it with the Visigothic text, hailing as they do from radically different environments. Rosa Guerreiro has suggested that the Carolingian text, which predates the Iberian one in the manuscripts, reflects a more primitive “Aragonese” text.Footnote 154 A close comparison of the two redactions makes clear, however, that the Saint-Germain manuscript preserves a newer Carolingian redaction, secondary to the more primitive redaction preserved in the (later) Iberian witnesses. To be sure, the Carolingian redaction does not constitute a réécriture on the scale of that of the Passion of Vincent, which greatly augmented and elaborated the Visigothic base text.Footnote 155 There was clearly a greater emphasis put on reworking and redefining the Passion of the monastery’s patron saint than there was on editing the other texts that had come north. Nonetheless, the Passion of the Innumerable clearly was edited, and the edits, though comparatively few, tell us much about how the Passion was understood in a new context, far from the center of cult.

In short, the Carolingian Passion of the Innumerable wrenched the text away from its immediate local context, removing much of the florid and effusive laus urbis, and rendered the text more generic and more universal, that is, more fitting for use in a distant monastery. There is still much civic material in the text, as there is in most martyr passions, and the Carolingian redaction cannot be said to be radically abridged, but the small details are telling. The Carolingian text is in many ways more “correct”: it has a smoother style, with fewer redundant words, and some of its passages have better grammar and less garbled spelling.Footnote 156 Elsewhere in the text, the unusual verb praestrepo, -ere (“to cause a din”), which is rare outside of Iberian texts, was removed by the Carolingian editor.Footnote 157 Likewise, the unusual phrase caput gentium is absent from the Carolingian version.

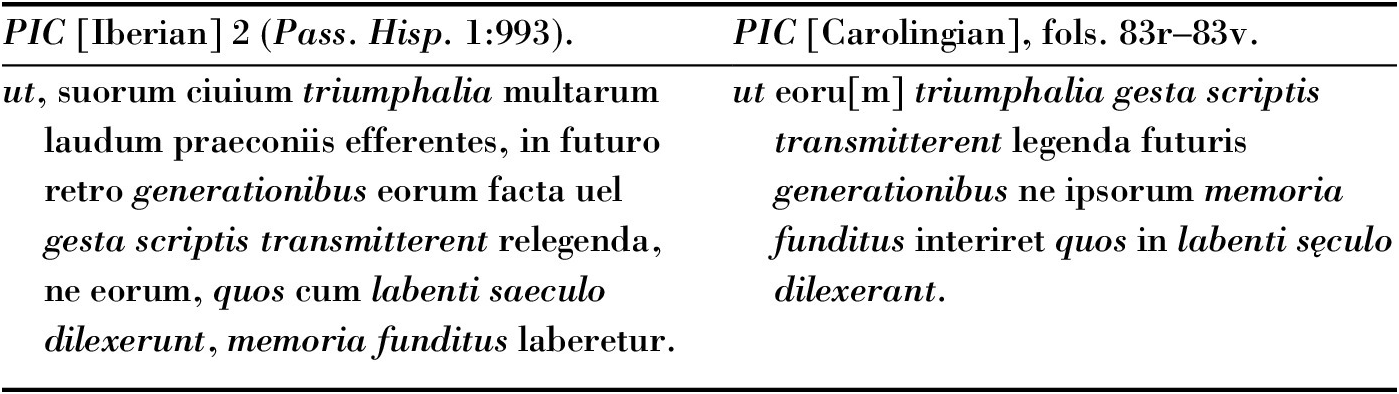

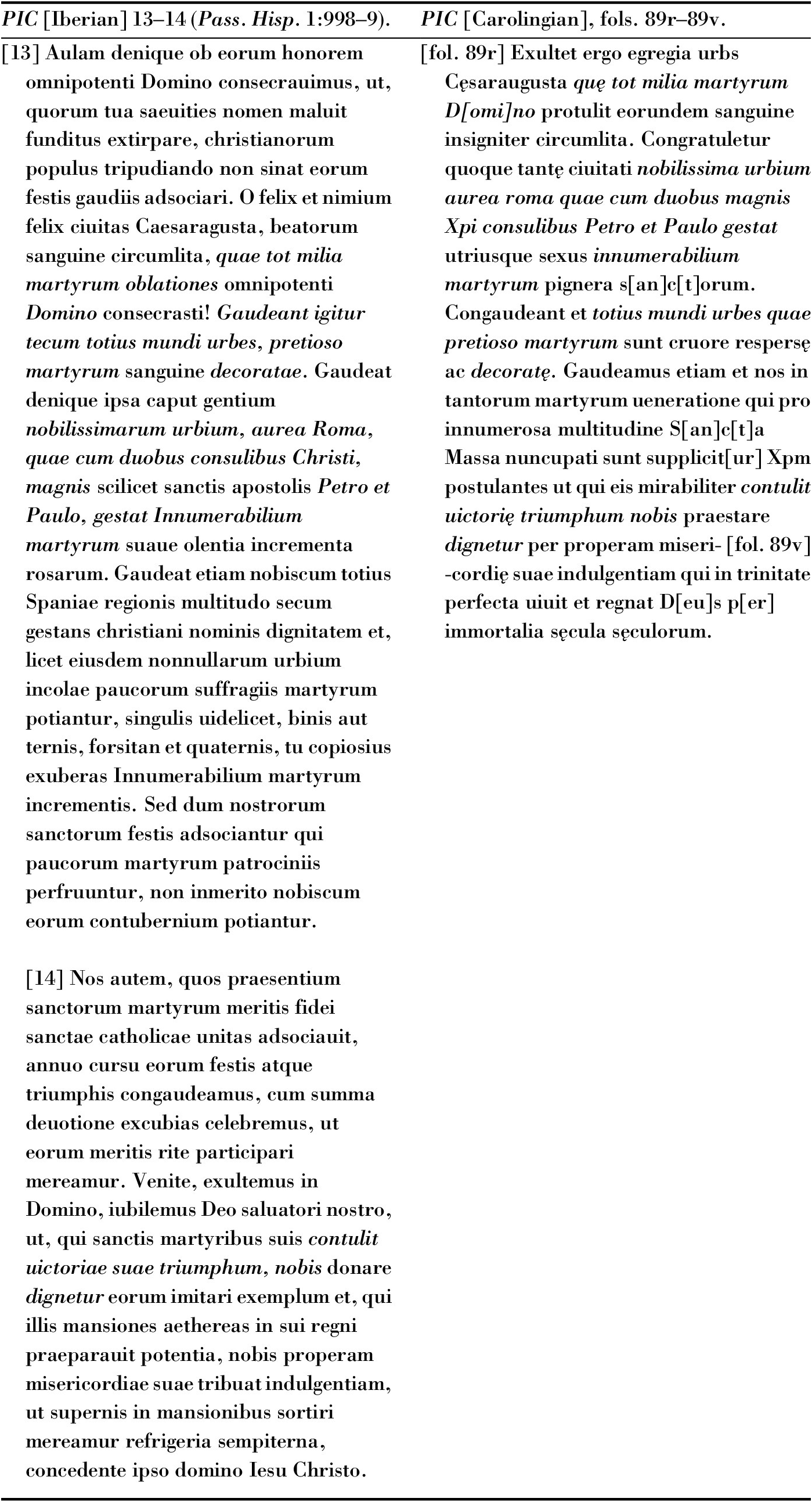

Some changes in style, however, evince a more substantial shift in the tone of the text, particularly in the diminution of its civic imagery. In the opening section, which evokes the modes of remembrance and memorialization practiced in Roman society, the Iberian text makes reference to “the triumphs of their citizens” proclaimed by the praeconia, that is, most literally the “public criers” of the town or else the more figurative notion of the “public proclamation” or “laudation.” The Carolingian text, by contrast, omits this Roman civic language, speaking only of the memorialization of ancient deeds in texts (Table 1). Though a minor change, it is illustrative of a wider move away from the imaginaire of the Roman city and its public sphere.

Table 1. Prefatory Material

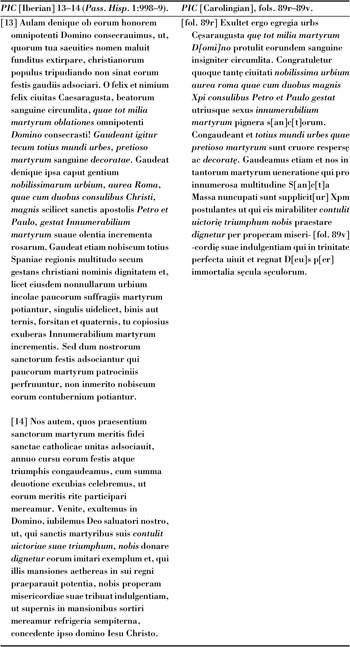

The shift away from the exigencies of public delivery is most evident in the closing section of the Passion. In the Iberian text, we find an effusive laus urbis addressed directly to a local crowd gathered in Zaragoza. The Carolingian text, by contrast, carries a much-attenuated closing section, significantly shorter and less rhetorical than its Iberian precursor. Although it draws on some similar themes (the exceptional fecundity of Zaragoza in producing martyrs; the need for Rome and the wider world to celebrate its martyrs), the Carolingian text does so without any indication that it is aimed at a specifically local audience. There is no indication of the doctrinal issues that mark the Iberian text or any mention of the newly reconsecrated church. Moreover, the closing passage has been wrested away from the specific historical and geographical circumstances in which it was composed, with its special mention of the cities of Spania, and made into a more universal evocation of the significance of the cult (Table 2). This is civic cult as seen from afar, over the walls of a Frankish monastery.Footnote 158

Table 2. Laus urbis

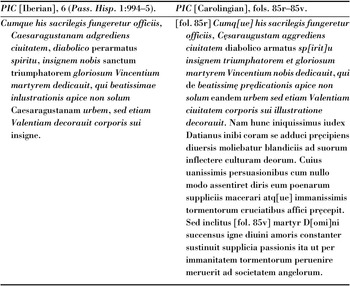

The Carolingian text is shorter overall than its Iberian precursor with some significant contractions. It omits, for example, the rhetorical mockery of Datian that follows the narrative of martyrdom in the Iberian redaction. The one area in which it expanded on the Iberian text, however, was in its discussion of Vincent of Zaragoza, a martyr who held much greater importance for the monks of Saint-Germain-des-Prés than the Innumerable (Table 3).

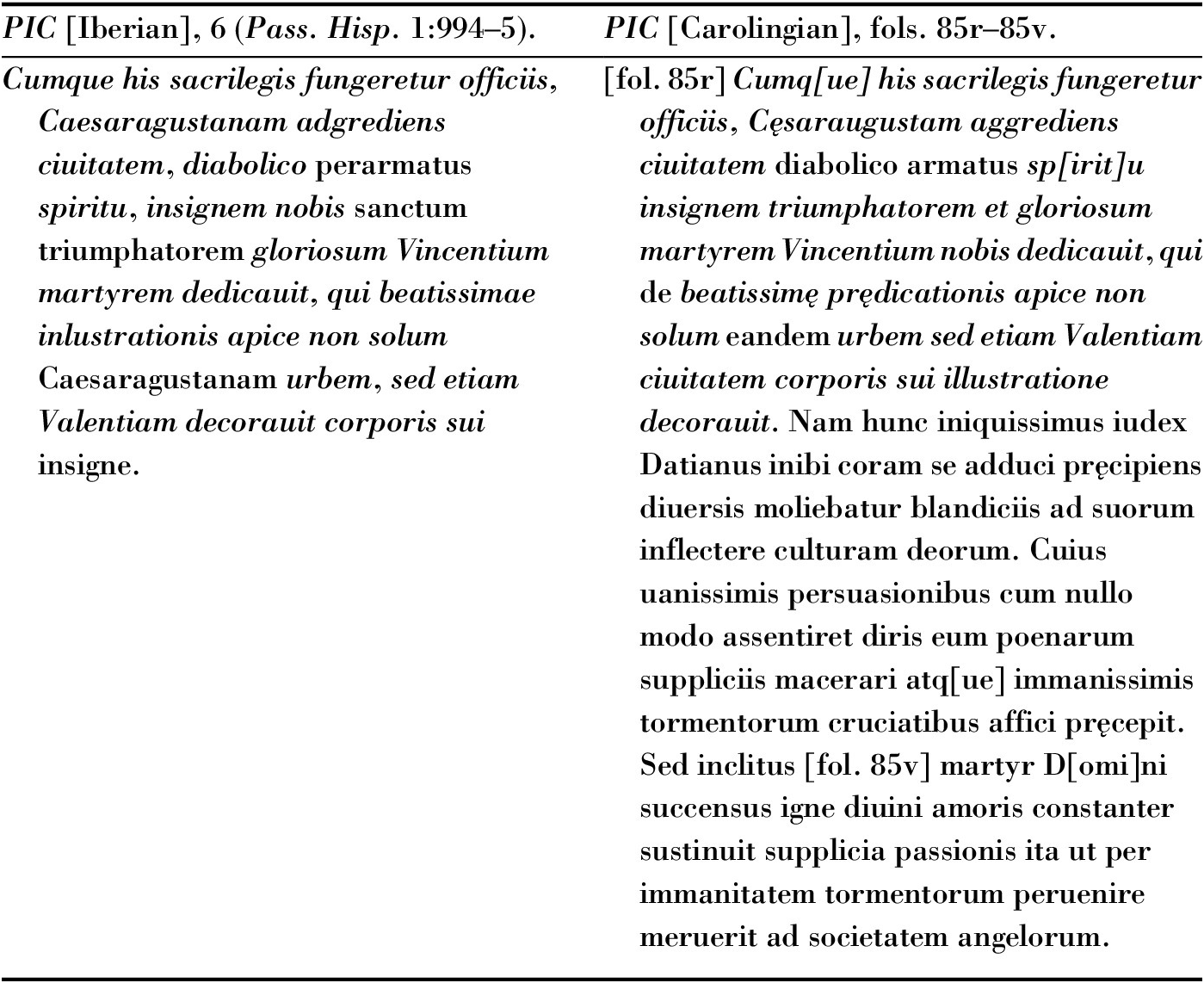

Table 3. Material on Vincent of Zaragoza