Introduction

Palaeoparasitology, the study of parasites in past human and animal populations, provides important data for the range of parasites that have been sustained in human populations before the modern era (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2024). This evidence exemplifies the successes of modern public health measures and allows us to explore drivers of parasite transmission within Britain throughout history. As we continue to study more historical sites, patterns in parasite transmission throughout specific regions arise and allow for more nuanced study into the palaeoepidemiology of parasite infections to truly understand when and how parasites have been controlled throughout human history (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2025). Here, we present evidence for parasite transmission at the Roman fort of Vindolanda and compare this to other sites within Roman Britain and the Roman Empire more broadly, to explore gastrointestinal parasite infection in Roman military settlements.

Vindolanda is a Roman military fort located just south of Hadrian’s Wall between Carlisle and Corbridge in modern-day Northumberland, Britain. Hadrian’s Wall was built by the Romans in the early 2nd century. CE as a defensive fortification, running east-west from the North Sea to the Irish Sea (Breeze, Reference Breeze2019). Excavations at Vindolanda have provided some of the most important evidence for life in Roman Britain, particularly military settlements along Hadrian’s Wall. In-depth insights into daily life have been gained through the analysis of exceptionally well-preserved organic objects, such as wood and leather, which are normally lost to archaeologists. Of particular value are more than 1000 thin wooden tablets, written with ink, that provide documentation of activities at the Roman site, including acquisition of materials, military communications, and personal communications (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Thomas and Tomlin2010).

The site was occupied by the Romans between the 1st and 4th century CE. Throughout that time there were various infantry and cavalry units stationed at the fort, including the First Cohort of Tungrians from modern-day Belgium, the Ninth Cohort of Batavians from modern-day Netherlands, the Second Cohort Nervian from modern-day France/Belgium, the Fourth Cohort Gauls from France, and the Vardulli cavalry from Spain (Birley, Reference Birley2009). There were multiple construction phases at Vindolanda with the initial, primarily timber-constructed fort, rebuilt as the garrison troops stationed there fluctuated as they responded to conflicts in the Empire. In the 3rd century, there was extensive construction at the site that included a village-like settlement (vicus) outside the walls of the fort (Blake, Reference Blake2014). Archaeological evidence shows that the site was not only inhabited by military personnel, but also women and children and others who supported the needs of the community, as was the case at many Roman military sites (Driel-Murray, Reference Driel-Murray1999; Greene, Reference Greene, Collins and McIntosh2014). Of relevance to our study of health and disease, and specifically parasite infections at Vindolanda, is the infrastructure that was built to manage human waste. The fort hosted two Roman bath houses, the pre-Hadrianic baths and later 3rd century baths (Birley, Reference Birley2001). The 3rd c. baths had water supplied from an aqueduct that channelled water from a spring located northwest of the vicus (Blake, Reference Blake2014). The natural springs located northwest of the site were also used to bring water into other areas of the site, as evidenced by ditches, stone aqueducts and timber pipes (Blake, Reference Blake2014). Managing drainage was equally important, especially with the high water table at Vindolanda, thus a number of ditches and drains are located around the site to remove water and waste (Birley and Blake, Reference Birley and Blake2005; Blake, Reference Blake2014).

Aside from providing exceptional archaeological evidence for life in Roman Britain, Vindolanda also provides us the opportunity to further understand health and disease on the northern frontiers of the empire. The work of palaeoparasitologists in Britain has been relatively extensive compared to other regions (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Flammer, Nicholson, Loe, Reeves, Allison, Guy, Doriga, Waldron, Walker, Kirchhelle, Larson and Smith2022; Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Redfern and Mitchell2024). This allows us to move away from broadscale analysis of parasite infections in past populations to a more nuanced analysis of how parasite infections varied within and between communities. Climate and ecology are major determinants of parasite endemicity regionally. However, there are a myriad of important social, cultural, political, and environmental factors that contribute to transmission on a finer scale which may result in variation in parasite infections at Vindolanda compared to other Roman sites in Britain.

Palaeoparasitological analysis of faecal material from Vindolanda can provide important evidence for parasite infections amongst the Roman military and associated community. The majority of existing palaeoparasitology data from Roman Britain comes from urban sites, particularly from London and York (Wilson and Rackham, Reference Wilson, Rackham and Buckland1976; Rouffignac, Reference Rouffignac1985; de Moulins, Reference de Moulins, Maloney and de Moulins1990; Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Flammer, Nicholson, Loe, Reeves, Allison, Guy, Doriga, Waldron, Walker, Kirchhelle, Larson and Smith2022; Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Redfern and Mitchell2024). The only other site along Hadrian’s Wall where palaeoparasitological analysis has been undertaken is Carlisle (Jones and Hutchinson, Reference Jones, Hutchinson and McCarthy1991). The exceptional preservation at Vindolanda offers an important opportunity to deepen our understanding of parasite transmission and gastrointestinal disease amongst the Roman military living in the northern frontiers of the empire. Thus, the aim of this study was to understand parasite infections at Vindolanda using samples collected from the length of a drain and fort ditches.

Materials

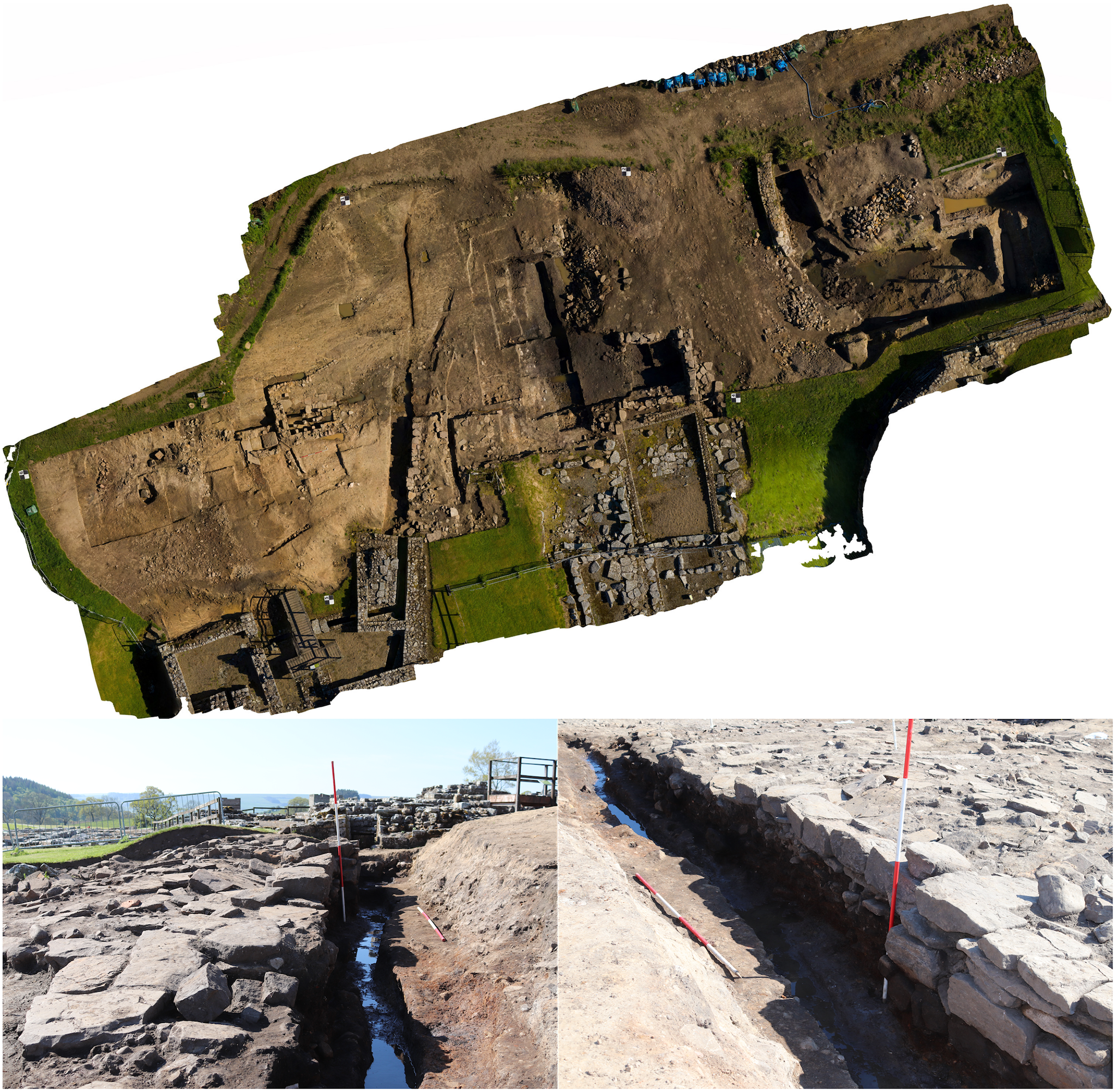

During the 2019 excavation season the main drain carrying latrine waste from the 3rd century bath house latrine down to the stream and valley to the north of Vindolanda was excavated (Figure 1). Excavations started at the remains of a 17th–19th century farmhouse (Smith’s Chesters). Below the farmhouse and its associated cobbled yard, the sealed deposits from the 3rd century bath house drain were uncovered (Collins, Reference Collins2020). Artefacts recovered from the drain included Roman beads, pottery and animal bones. The western edge of the drain had been cut into a combination of natural and re-deposited clay that had been brought in to cover the remains of much earlier fort defensive ditches, before the construction of the 3rd century latrines took place. The eastern side was backed onto the sandstone foundations of a vicus building. This was constructed with large slabs of packed sandstone and boulder clay packing the joints, creating an effective barrier to water loss.

Figure 1. Aerial view of the latrine drain (top). Photos of the latrine drain during excavation (bottom).

The depth of the drain varied from 1.3 m at its southern end where it exited the latrine, to 18 cm deep at its termination. The main drain split into two channels around 9 m to the north of the latrine, with the main channel continuing directly to the northwest, maintaining a slight slope of only 2–3 degrees, and a steeper extension or branch channel cut to the northeast. The northeastern channel followed the steeper slope of the hill and therefore gained a much greater 10–14 degree angle, enabling the more rapid removal of water through this side channel.

The drain had three primary fills. An upper fill consisting of deposits of dark brown soil, masonry, and lime mortar which formed after the drain was no longer in use, likely associated with the abandonment of the latrine and baths towards the end of the 3rd century (context V19-2). Below this were the two primary occupational deposits. Context V19-11 was contemporary with the final use of the latrine and baths, and it contained a soil/silt mixture that had a large volume of fine ash and soot in it, staining the soil black. The primary fill of the drain was in a shallow channel about 30 cm wide and 20 cm deep, cut into the base of the drain, and this contained a finer grey silty soil (context V19-26).

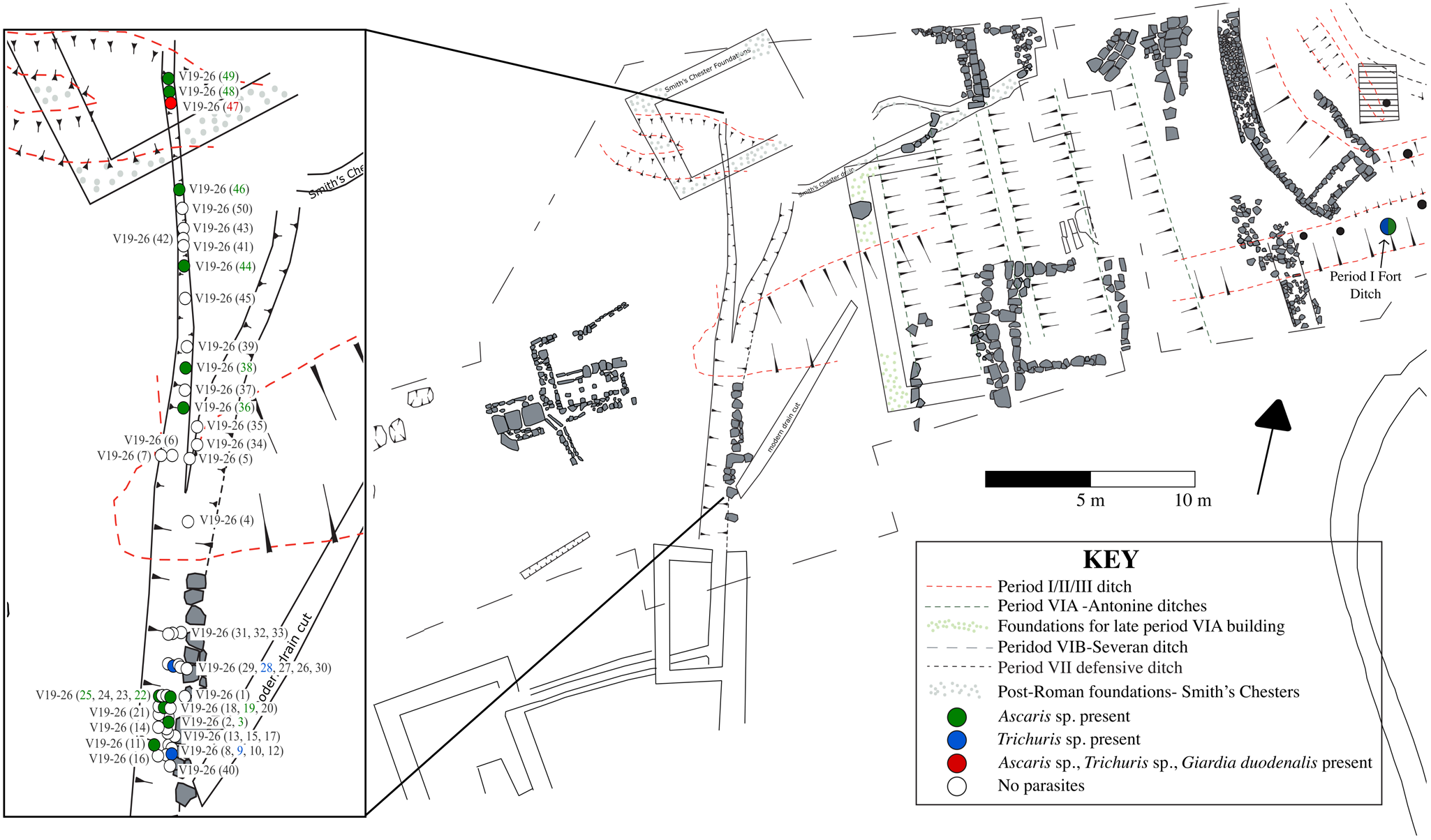

Fifty-eight sediment samples were collected along the length of the drain from the two primary occupational contexts. Fifty samples came from the primary fill (see Figure 2, V19-26) and eight samples came from the final use of the latrine (V19-11). In addition, one sample was also collected from the nearby Period I Fort Ditch. The Period I Fort at Vindolanda was constructed in 85 CE and occupied until 91/92 CE. Its northern ditch was filled with 2.3 m of organically preserved anaerobic material, sealed below 2 m of clay and rampart material from the later builds. The artefacts from these deposits included finely preserved leather shoes, leather bags and tent panels, some woven textiles, and a matt of yellow hair on the jawbone from a small dog.

Figure 2. Excavation plan from Vindolanda showing the drain that was sampled for palaeoparasitological analysis and the location of samples from the primary fill (V19-26). The inset shows the location of parasite samples along the length of the drain with coloured circles indicating the parasite taxa found.

The samples were split between two labs for analysis. Samples V19-26 41–50 and seven samples from V19-11 were processed in the Ancient Parasites Lab at the University of Cambridge. Samples from V19-26 1–40, and one sample each from V19-11 and from the northern Period I Fort ditch were processed at the University of Oxford.

Methods

All samples were disaggregated and microsieved to concentrate material within the size range of helminth eggs. This material was viewed with a compound light microscope at 200x and 400x magnification to detect preserved helminth eggs.

As the samples were processed in two separate laboratories there were slight variations to the methods used. At the University of Oxford (V19-26 samples 1–40, V19-11 and Period I Fort ditch), 5–7 g of sediment was rehydrated in ultrapure water with gentle agitation (Titertek shaker setting 3) then filtered using sieves with 1030 and 500 µm mesh. Material less than 500 µm was collected and concentrated by centrifugation (400 g, 10 min). The remaining pellet was resuspended in ultrapure water and microscopy was performed (Anastasiou and Mitchell, Reference Anastasiou and Mitchell2013; Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Flammer, Nicholson, Loe, Reeves, Allison, Guy, Doriga, Waldron, Walker, Kirchhelle, Larson and Smith2022). For samples processed at the University of Cambridge (V19-26 samples 41–50 and V19-11), 0.2 g of sediment was rehydrated in 0.5% trisodium phosphate with intermittent vortexing until all material was disaggregated. Samples were then microsieved using sieves with 300, 160, and 20 µm mesh. Material between 20 and 160 µm was collected and concentrated by centrifugation (3000 g, 5 min). The pellet was resuspended in glycerol and microscopy was performed (Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Micarelli, Ward, Prowse, Carroll, Killgrove, Rice, Franconi, Tafuri, Manzi and Mitchell2021).

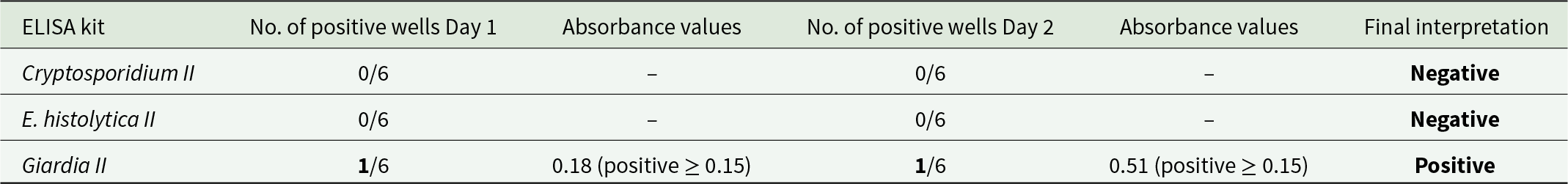

In addition, one sample with preserved helminth eggs (V19-26 sample 47) was tested using commercial ELISA kits to detect preserved antigens from Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica, and Giardia duodenalis. The ELISA kits used were Entamoeba histolytica II, Giardia II, and Cryptosporidium II produced by TECHLAB (Blacksburg, Virginia, USA). A 1 g subsample was disaggregated in 0.5% trisodium phosphate, microsieved to collect material less than 20 µm, and centrifuged to concentrate material. The remainder of the test procedure followed the manufacturer’s test protocol. A total of 6 technical replicates and one biological replicate on a separate day were tested. A sample was considered positive if biological replicates were both positive (i.e. a positive result was obtained on 2 separate days, with 2 separate ELISA kits, using 2 separate subsamples). Absorbance values were obtained using an ELISA plate reader at 450 nm and positive results were called using the interpretive criteria in the manufacturer’s test protocol. Appropriate colour changes in each well were also visually confirmed.

Results

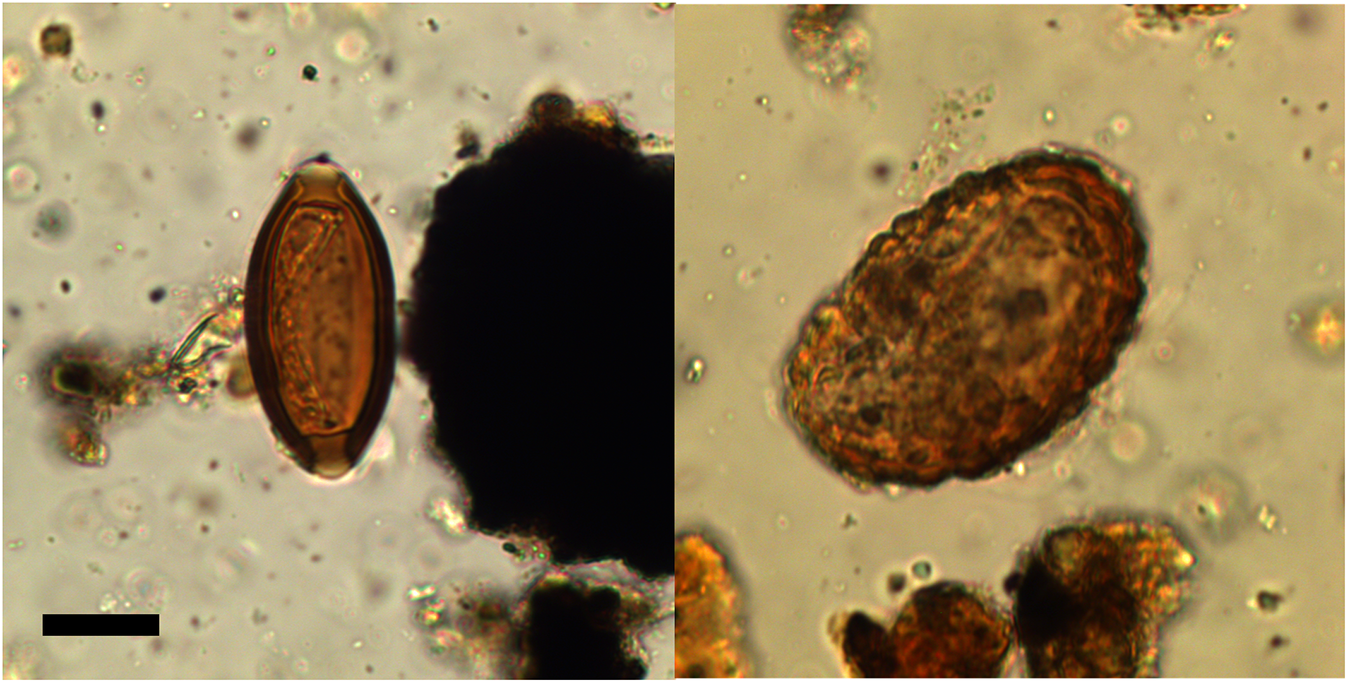

Helminth eggs were found in 28% (14/50) of samples collected from the primary fill (V19-26) along the length of the 3rd century CE drain (Figure 2). The helminth taxa recovered from the primary fill of the drain were Ascaris sp. (roundworm) and Trichuris sp. (whipworm) (Figure 3). G. duodenalis was also detected using ELISA in the sample tested (V19-26 sample 47) (Table 1). This was also the only sample that contained both Ascaris sp. and Trichuris sp. eggs together. Ascaris sp. was found alone in 22% (11/50) of samples, while Trichuris sp. was found alone in 4% (2/50) of samples. In comparison, 25% (2/8) of the samples from the final fill of the drain (V19-11) contained helminth eggs, one had both Ascaris sp. and Trichuris sp. eggs and one had only Ascaris sp. eggs.

Figure 3. Trichuris sp. (left) and Ascaris sp. (right) eggs recovered from Vindolanda. Scale bar is 20 µm.

Table 1. ELISA results from Vindolanda drain sample V19-26 sample 47. The ELISA kit used with number of positive wells on both days of testing is presented with the absorbance values from positive wells and cut-off value for determining positivity

Finally, the sample collected from the Period I Fort ditch (1st century CE) contained Ascaris sp. and Trichuris sp. eggs.

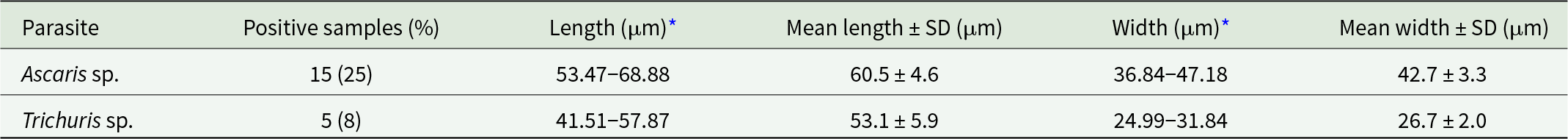

The mean size of Trichuris sp. eggs was 53.1 µm long (standard deviation 5.9) and 26.7 µm wide (standard deviation 2.0, N = 10) (Table 2). For only those with preserved polar plugs the mean length was 57.3 µm long (standard deviation 0.4) and 27.3 µm wide (standard deviation 2.3, N = 6). The typical size range of Trichuris trichiura (human-infecting whipworm) is 50–60 µm long and 20–30 µm wide (Garcia, Reference Garcia2016; Ryoo et al. Reference Ryoo, Jung, Hong, Shin, Song, Kim, Ryu, Sohn, Hong, Htoon, Tin and Chai2023). The mean size of Ascaris sp. eggs recovered were 60.5 µm long (standard deviation 4.6) and 42.7 µm wide (standard deviation 3.3, N = 10). Approximate egg concentrations were calculated and ranged from 5 to 84.7 eggs per gram (epg) for Ascaris and 35 to 79.9 epg for Trichuris in the drain samples from the primary fill (V19-26). The egg concentrations in one V19-11 subsample were 10 epg for both Ascaris and Trichuris and in the other subsample were 61.7 epg of Ascaris with no Trichuris, while remaining samples contained no eggs. Egg concentrations in the Period I Fort Ditch were higher at 648.1 epg for Ascaris and 787.8 epg for Trichuris.

Table 2. Number of positive samples for each parasite taxa with size ranges and mean dimensions for each parasite taxa

* 10 eggs of each taxa were measured. SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

Sampling along the length of a drain at the Roman Fort of Vindolanda has provided evidence for parasite presence at the site. Parasites were recovered from 28% of samples from the primary fill (3rd century CE) collected along the length of the drain. All parasites recovered are spread by ineffective sanitation. Ascaris sp. (roundworm) and Trichuris sp. (whipworm) are both soil-transmitted helminths (worms). Eggs were identified to the genus-level given the inability to differentiate between closely related species based on morphology. Ascaris lumbricoides and Ascaris suum are indistinguishable under the microscope and while the size of different Trichuris sp. eggs is variable, the typical size range of T. trichiura overlaps that of T. suis (pig-infecting whipworm) (Beer, Reference Beer1976) precluding differentiation of the eggs identified in our samples. The large size range of the Trichuris eggs recovered from the drain samples is partially attributed to variation in preservation of the polar plugs. However, for the minority of eggs that were the largest, we cannot rule out that some may be from other animal species whose faeces may have contaminated the drain such as Trichuris muris from mice. Ascaris sp. and Trichuris sp. can cause co-infections and are often found within the same populations today (Howard et al. Reference Howard, Donnell and Chan2001; Lepper et al. Reference Lepper, Prada, Davis, Gunawardena and Hollingsworth2018). Similarly, they are commonly detected together in communal deposits from Roman period sites, including those in Britain (Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Redfern and Mitchell2024, Reference Ledger, Murchie, Dickson, Kuch, Haddow, Knüsel, Stein, Pearson, Ballantyne, Knight, Deforce, Carroll, Rice, Franconi, Šarkić, Redžič, Rowan, Cahill, Poblome, de Fátima Palma, Brückner, Mitchell and Poinar2025). Interestingly, however, one study analysing pelvic soil samples from Roman period Britain did not detect any co-infections of Ascaris sp. and Trichuris trichiura in Roman period individuals (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Flammer, Nicholson, Loe, Reeves, Allison, Guy, Doriga, Waldron, Walker, Kirchhelle, Larson and Smith2022). Thus far, only one study from Roman Britain has shown evidence for co-infection of Ascaris sp. and Trichuris sp. in one individual (Jones, Reference Jones1987). G. duodenalis, which was also identified in the drain, is a unicellular flagellate that is often transmitted through contaminated drinking water or food (Minetti et al. Reference Minetti, Chalmers, Beeching, Probert and Lamden2016). The presence of these three parasites is suggestive of faecal contamination of drinking water and/or food sources at the Roman fort in the 3rd century CE. Additionally, the sample collected from the earlier Period I Fort ditch (1st century CE) also contained Ascaris sp. and Trichuris sp. indicating that these parasites were persistently present through time at the site.

Ascaris sp. was present in 15 samples while Trichuris sp. was present in only five. This may indicate a predominance of Ascaris sp. infection in the community. However, the reproductive potential and worm burdens of these two parasites should be kept in mind. Female A. lumbricoides worms can release up to 200 000 eggs per day (Phuphisut et al. Reference Phuphisut, Poodeepiyasawat, Yoonuan, Watthanakulpanich, Chotsiri, Reamtong, Mousley, Gobert and Adisakwattana2022) while Trichuris trichiura worms only release 18 000 (Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Tejedor, Thamsborg, Alstrup Hansen, Dahlerup and Nejsum2016). For this reason the definition of a heavy worm burden for Ascaris and Trichuris are different, with heavy Ascaris infection defined as ≥50 000 eggs per gram of stool and Trichuris ≥10 000 eggs per gram (Montresor et al. Reference Montresor, Crompton, Hall, Bundy and Savioli1998). However, the total number of worms that an individual can carry from the two species also varies. The absolute number of Trichuris worms that an individual can carry being higher than that of Ascaris (Brooker, Reference Brooker2010). Despite the variation in fecundity of these two worms, the much larger proportion of samples that contain Ascaris sp. eggs may suggest that Ascaris sp. was more common within the community.

Transmission of both Ascaris sp. and Trichuris sp. within one community is expected based on the similarities in their faecal-oral transmission route (Else et al. Reference Else, Keiser, Holland, Grencis, Sattelle, Fujiwara, Bueno, Asaolu, Sowemimo and Cooper2020). Both are endemic in many tropical or subtropical low and lower middle income countries (Holland et al. Reference Holland, Sepidarkish, Deslyper, Abdollahi, Valizadeh, Mollalo, Mahjour, Ghodsian, Ardekani, Behniafar, Gasser and Rostami2022). However, it is clear that these infections were common in past European populations (e.g. Roche et al. Reference Roche, Pacciani, Bianucci and Le Bailly2019; Flammer et al. Reference Flammer, Ryan, Preston, Warren, Přichystalová, Weiss, Palmowski, Boschert, Fellgiebel, Jasch-Boley, Kairies, Rümmele, Rieger, Schmid, Reeves, Nicholson, Loe, Guy, Waldron, Macháček, Wahl, Pollard, Larson and Smith2020; Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Flammer, Nicholson, Loe, Reeves, Allison, Guy, Doriga, Waldron, Walker, Kirchhelle, Larson and Smith2022; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2023; Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Redfern and Mitchell2024).

One other possibility to keep in mind is the zoonotic potential of Ascaris. While Ascaris presence in archaeological sites is commonly linked to human-to-human transmission as a result of poor sanitation in the past, epidemiological data in modern populations points to the zoonotic potential of A. suum infecting humans (Anderson, Reference Anderson1995; Nejsum et al. Reference Nejsum, Betson, Bendall, Thamsborg and Stothard2012; da Silva et al. Reference da Silva, Barbosa, Magalhães, Gazzinelli-Guimarães, Dos Santos, Nogueira, Resende, Amorim, Gazzinelli-Guimarães, Viana, Geiger, Bartholomeu, Fujiwara and Bueno2021). This is particularly relevant to the Roman period when there is a distinct reliance on pigs, especially in the Mediterranean region (King, Reference King1999). However, zooarchaeological studies in Britain have highlighted the variation in foodways across the Empire and shown that in Roman Britain cattle were the dominant domesticate followed by sheep and pigs to a lesser extent (Rizzetto et al. Reference Rizzetto, Crabtree and Albarella2017). These broad comparisons by region, however, do not consider site type. For example, studies have shown that even within a single region animal husbandry varied between urban, rural and military sites (Valenzuela-Lamas and Albarella, Reference Valenzuela-Lamas and Albarella2017). At Vindolanda, the exceptional preservation of the Vindolanda tablets give us particular insight into meat preferences, with pig being a popular source of meat as documented in written records from the site (Pearce, Reference Pearce2002). A. lumbricoides is classically considered the human-infecting species of roundworm while A. suum is the pig-infecting species. However, a multitude of experimental and clinical cases exist of human infection with A. suum (Bendall et al. Reference Bendall, Barlow, Betson, Stothard and Nejsum2011; Nejsum et al. Reference Nejsum, Betson, Bendall, Thamsborg and Stothard2012; Betson et al. Reference Betson, Nejsum, Bendall, Deb and Stothard2014). For example, multiple infections were documented in schoolchildren in Denmark after the school garden was fertilized with pig manure (Roepstorff et al. Reference Roepstorff, Mejer, Nejsum and Thamsborg2011). The use of pig faeces as fertilizer or pig faeces contaminating crops and water sources could additionally lead to human infections in the Roman period. Unfortunately, it is not possible to distinguish between the two species using morphological appearance, thus we have identified the eggs as Ascaris sp. Similarly T. suis (pig whipworm) has been shown to establish infections in humans, however, it is expected that reproductive capacity is limited in these cases (Nejsum et al. Reference Nejsum, Betson, Bendall, Thamsborg and Stothard2012). Thus, while the Trichuris eggs recovered from Vindolanda could be from either species, if the drain primarily contained human faecal material from the bath complex it seems more likely that the Trichuris eggs are from T. trichiura, the transmission of which would be more easily maintained within the population. Finally, we need to consider that if pigs were reared or butchered within the vicinity of this drain, the faecal material and intestinal contents of pigs could have been washed into the drain leaving behind T. suis eggs that may have infected pigs at the site.

G. duodenalis was also detected using ELISA. Studies suggest that the Giardia II ELISA kits we used, which target the Giardia Cyst Wall Protein 1, have a high sensitivity and specificity for G. duodenalis in fresh faecal samples, ranging from 91% to 100% sensitivity and 97.8% to 100% specificity (Boone et al. Reference Boone, Wilkins, Nash, Brandon, Macias, Jerris and Lyerly1999; Silva et al. Reference Silva, Pacheco, Martins, Menezes, Costa-Ribeiro, Ribeiro, Mattos, Oliveira, Soares and Teixeira2016). However, sensitivity is expected to be lower in archaeological samples. The presence of G. duodenalis further exemplifies the transmission of faecal-oral diseases at the site. This is the first evidence for G. duodenalis in archaeological contexts in Britain. G. duodenalis has also been detected in latrines from Iron Age Jerusalem (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Wang, Billig, Gadot, Warnock and Langgut2023), Roman period Italy and Turkey (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Arnold-Foster, Yeh, Ledger, Baeten, Poblome and Mitchell2017; Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Micarelli, Ward, Prowse, Carroll, Killgrove, Rice, Franconi, Tafuri, Manzi and Mitchell2021) and later time periods in Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Israel/Palestine, and the Netherlands (Gonçalves et al. Reference Gonçalves, Araújo, Duarte, da Silva, Reinhard, Bouchet and Ferreira2002; Le Bailly et al. Reference Le Bailly, Gonçalves, Harter-Lailheugue, Prodéo, Araujo and Bouchet2008; Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Stern and Tepper2008; Bartošová et al. Reference Bartošová, Ditrich, Beneš, Frolík and Musil2011; Yeh et al. Reference Yeh, Prag, Clamer, Humbert and Mitchell2015; Eskew et al. Reference Eskew, Ledger, Lloyd, Pyles, Gosker and Mitchell2020; Graff et al. Reference Graff, Bennion-Pedley, Jones, Ledger, Deforce, Degraeve, Byl and Mitchell2020; Rabinow et al. Reference Rabinow, Wang, van Oosten, Meijer and Mitchell2024). We cannot confirm that the detection of G. duodenalis indicates human infection as many other animals can also be infected with G. duodenalis, and the drain could have been contaminated with run-off from other areas of the site contaminated by animal faeces. However, the suite of parasites found, which all have common transmission routes and are often co-endemic in human populations, in a drain primarily carrying latrine contents, lends weight to them originating from infected people living at Vindolanda.

Parasite evidence from Roman Britain has recently been reviewed (Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Redfern and Mitchell2024). Across Roman Britain, Ascaris and Trichuris are the most common parasites found, with at least one of these taxa being found at every site studied (Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Redfern and Mitchell2024). However, Dibothriocephalus sp. (fish tapeworm), Taenia sp. (beef or pork tapeworm), Fasciola sp. (common liver fluke), and Dicrocoelium sp. have also been recovered (Pike, Reference Pike1968; Rouffignac, Reference Rouffignac1985; de Moulins, Reference de Moulins, Maloney and de Moulins1990; Jones and Hutchinson, Reference Jones, Hutchinson and McCarthy1991; Boyer, Reference Boyer, Connor and Buckley1999; Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Flammer, Nicholson, Loe, Reeves, Allison, Guy, Doriga, Waldron, Walker, Kirchhelle, Larson and Smith2022). Of particular relevance to the current study is the palaeoparasitological investigation undertaken on occupation layer sediments dating from the 1st–4th century CE from Carlisle, another site along Hadrian’s Wall, only 40 km from Vindolanda. In these sediment samples eggs of Ascaris, Trichuris and Fasciola sp. were recovered (Jones and Hutchinson, Reference Jones, Hutchinson and McCarthy1991). Given the sample type studied, it may well be that the Fasciola eggs recovered represent infection of animals kept near the site. Regardless, this study confirms that Fasciola was present in the region at this time though we find no evidence for infections at Vindolanda. Elsewhere in the Empire we also have similar evidence for transmission of Ascaris and Trichuris in military settlements in the absence of other helminths including at Carnuntum in Austria (Aspöck et al. Reference Aspöck, Feuereis, Radbauer, Jansen, Koloski-Ostrow and Moormann2011), Valkenburg on Rhine in the Netherlands (Jansen and Over, Reference Jansen, Over and Corradetti1966), Bearsden in Scotland (Knights et al. Reference Knights, Dickson, Dickson and Breeze1983) and Viminacium in Serbia (Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Rowan, Marques, Sigmier, Šarkić, Redžić, Cahill and Mitchell2020; Marković et al. Reference Marković, Raičković Savić, Mitić and Mitchell2024). Whether this is reflective of the overall predominance of Ascaris and Trichuris in the Roman period as a whole, or a particular pattern seen in military settlements will likely be further elucidated as we gain more evidence from palaeoparasitological studies.

The sampling approach undertaken in this study highlights the value of collecting samples from multiple locations along archaeological drainage features to increase chances of recovering biological remains in faecal material. As to be expected in archaeological settings, not all samples collected from the same drain were positive for parasites. However, by collecting multiple samples, we can increase our ability to more accurately reconstruct parasite presence in archaeological contexts. In addition, collecting samples along the course of drains (as done in this study) may provide information on drainage design and use. The drain sampled in this study consisted of two channels fed from one larger channel that was connected to the latrine (see Figures 1 and 2). The samples that were collected from the northeastern channel did not contain any parasite eggs, while multiple samples collected from the northwestern channel and the wider portion that fed these two channels did contain parasite eggs. This may indicate that the northwestern channel was carrying the bulk of the latrine run-off, or that the slower rate of flow in this channel allowed for more deposition of faecal material, while the steeper northeastern channel carried this material away on a stronger current. However, fewer samples were collected from the eastern channel, thus it is possible that this channel did originally contain faecal material but we did not have adequate samples to detect this. One limitation of studying drain samples is that run-off from the town can also be carried within the drain, thus recovered parasite eggs may also represent general environmental contamination. In this study, while we expect the bulk of the fill of the drain to have come from the latrine it was connected to, there is a possibility for material from other areas of the settlement to be washed into the drain.

While latrines and cesspit fill are very common sample types for palaeoparasitological analysis, drain samples have also proven to be a useful sample type for recovering parasite eggs. This has been undertaken in other archaeological sites, particularly in the Roman period where the architectural remains of drains have been preserved. Ascaris and/or Trichuris have been recovered from Roman period drains from the sites of Vagnari and Vacone, Italy and Sardis, Türkiye (Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Rowan, Marques, Sigmier, Šarkić, Redžić, Cahill and Mitchell2020, Reference Ledger, Micarelli, Ward, Prowse, Carroll, Killgrove, Rice, Franconi, Tafuri, Manzi and Mitchell2021). From Roman Britain, eggs from Ascaris and Trichuris were recovered from a sewer system in York (Wilson and Rackham, Reference Wilson, Rackham and Buckland1976). Samples collected from both latrines and latrine drains in the Hellenistic City of Delos, Greece contained Ascaris, Trichuris and Strongyle-type eggs (Roche et al. Reference Roche, Capelli, Bouet and Le Bailly2025). While these findings were useful in confirming the use of drain structures as possible structures for carrying faecal waste, samples were not collected along the length of these drain structures precluding further analysis of drain function.

The impact that these parasites would have had on the community of Vindolanda is likely to be similar to what was experienced elsewhere in the Roman Empire. Palaeoparasitological studies undertaken in various regions of the Roman Empire suggest that gastrointestinal parasite infections, especially with Ascaris and Trichuris, were likely quite common (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2017; Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Murchie, Dickson, Kuch, Haddow, Knüsel, Stein, Pearson, Ballantyne, Knight, Deforce, Carroll, Rice, Franconi, Šarkić, Redžič, Rowan, Cahill, Poblome, de Fátima Palma, Brückner, Mitchell and Poinar2025). This was no different for Roman military troops stationed at Vindolanda. Palaeoparasitological studies on other Roman sites have shown that environmental contamination with eggs from Ascaris and Trichuris was occurring and likely contributed to ongoing transmission of these parasites (Van Geel et al. Reference Van Geel, Buurman, Brinkkemper, Schelvis, Aptroot, van Reenen and Hakbijl2003; Roche et al. Reference Roche, Jouffroy-Bapicot, Vannière and Le Bailly2020; Gaillot et al. Reference Gaillot, Dendievel, Argant, Audibert, Bouby, Delhon, Dessaint, Gunnell, Maicher, Le Bailly and Monin2024). The presence of parasites transmitted by the faecal-oral route indicates that other pathogens transmitted by the same route could have been supported in the community and some of these pathogens may have contributed to disease outbreaks (e.g. Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, norovirus, adenovirus, rotavirus, enterovirus). There is written evidence for conjunctivitis spreading at the fort when the First Cohort of the Tungrians were stationed there (Jackson, Reference Jackson1990; Birley, Reference Birley2009:68). A letter recording the strength of the unit states that 10 men were unfit for duty as they were suffering from conjunctivitis. One must wonder if the cause of conjunctivitis was one of these common gastrointestinal viruses that are also common causes conjunctivitis such as adenovirus and enterovirus.

Conclusion

Palaeoparasitological analysis of samples from the length of a latrine drain and ditches at the Roman site of Vindolanda along Hadrian’s Wall reveal evidence for the presence of Ascaris, Trichuris, and Giardia duodenalis at the site. These results provide further evidence for the types of gastrointestinal diseases that Roman military units likely experienced and are remarkably similar to those found in other regions of the Empire. The sole presence of parasites related to sanitation conditions exemplifies the risk for infections transmitted by the faecal-oral route in Roman military settlements. This study also highlights the value of sampling multiple locations along archaeological drains to increase detection of ancient parasites as well as investigate drainage patterns within a site.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Vindolanda Trust and excavation teams and TechLab, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA for donating ELISA kits used in this study.

Author contributions

M.L.L., P.F., A.S., A.B., P.D.M. conceptualized the study. M.L.L. and P.F. performed laboratory analysis. AB contributed to excavation and sample collection. M.L.L. was responsible for writing original manuscript draft. M.L.L., P.F., A.S., A.B., P.D.M. were responsible for writing and editing the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Doctoral Award to M.L.L. A Cambridge Commonwealth, European and Internal Trust and Trinity Hall College Award to M.L.L.

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.