Introduction: What This Element Is About

We have many beliefs. Some are justified. Consider scientific beliefs that are formed after carefully consulting the available evidence and ruling out alternative hypotheses, or perceptual beliefs about nearby objects formed in good lighting conditions, or your clear recollections of what you had for breakfast this morning.

Other beliefs are not justified. Consider beliefs formed via wishful thinking, or beliefs tainted by bias, or beliefs formed from shoddy guesswork.

It’s easy enough to list some paradigmatic examples of justified and unjustified beliefs. Can we say anything more systematic about the distinction? That is, can we give a general account of what makes a belief justified or unjustified?

This question has received a tremendous amount of attention from epistemologists. There are at least two reasons why epistemologists have been so interested in justification. First, justification matters to us. We want our beliefs to be justified. Second, many epistemologists have held that justification is closely connected with other epistemic statuses, for example, knowledge. Someone who merely believes, for no good reason, that there is an even number of stars in the universe and happens to get this right does not know that there is an even number of stars. This has suggested to some epistemologists that justification is a necessary condition on knowledge. If this is right, then insofar as epistemologists are interested in understanding knowledge, they should also be interested in understanding justification.

This Element is about how to understand justification. Specifically, it is about one prominent theory of justification: reliabilism. The key idea behind reliabilism is that justification is closely connected to reliability:

Core Reliabilist Idea: Whether a belief is justified is largely a matter of whether it is reliably formed.

Reliabilism is a controversial view. Some of the controversies are in-house: There are disagreements among reliabilists about how to understand the sort of reliability required for justification. The more significant controversies concern whether we should buy into the core reliabilist idea in the first place. Why think reliability has anything to do with justification?

The aim of this Element is to explore these controversies and make progress toward resolving them. I start (Section 1) by explaining reliabilism in more detail. I proceed (Section 2) to highlight some selling points of reliabilism. These include its ability to capture our intuitive judgments about paradigm cases of justified and unjustified beliefs, its response to skepticism, and its ability to situate epistemic properties within a naturalistic worldview. These selling points go some way to answering the question: Why think justification has anything to do with reliability?

After the good news comes the bad. Section 3 reviews some problems facing reliabilism. Philosophers have objected that reliability is not necessary for justification (Section 3.1), that it is not sufficient for justification (Sections 3.2 and 3.3), and also that the very idea of a reliably formed belief cannot be articulated with sufficient precision (Section 3.4). These problems have convinced some philosophers that reliabilism must be abandoned.

While these philosophers do not always agree on what should take its place, one popular alternative is evidentialism. The key idea behind evidentialism is that justification is closely tied to evidence:

Core Evidentialist Idea: Whether a belief is justified is largely a matter of whether it is supported by the believer’s evidence.

But should we abandon reliabilism so readily? Not so fast, say I. Reliabilism has significant explanatory advantages, and evidentialism faces problems of its own. This raises an interesting prospect. Perhaps some view that synthesizes elements of reliabilism with aspects of evidentialism could offer the best of both worlds, retaining the advantages of reliabilism while also avoiding its problems.

The second half of the Element is devoted to exploring this prospect: I examine in detail different ways of synthesizing reliabilism with evidentialism. We’ll see (Section 4) that many extant attempts to wed reliabilism with evidentialism face important difficulties: They either fail to fully solve the problems for reliabilism, or they abandon the very features that rendered reliabilism attractive. In Section 5, I sketch two paths toward developing a more promising synthesis – a synthesis that retains the virtues of both views while avoiding the most pressing worries.

What is my overall message about reliabilism? Is the view correct? My answer will not be one of unqualified endorsement, but one of cautious optimism. The advantages of reliabilism should not be abandoned lightly. Moreover, some of the problems for reliabilism arose because of some specific – and ultimately dispensable – features of early formulations of reliabilism. A view that retains reliabilist commitment while adopting a somewhat different structure (in particular, taking on board evidentialist elements) offers a promising path forward.

1 Reliabilism, A Primer

1.1 Process Reliabilism Introduced

The key reliabilist idea is that justification is a matter of reliability: A belief is justified provided it is reliably formed. But what does this mean? The most common answer spells this out in terms of the reliability of the process through which the belief was formed and sustained. This theory is known as “process reliabilism.” In its simplest version:

Simple Process Reliabilism: A belief is justified iff it is produced by a reliable belief-forming process.

Process reliabilism has been developed in most detail by Alvin Goldman (see esp. Goldman Reference Goldman and Pappas1979, Reference Goldman1986, Reference Goldman and Pappas2012), though other epistemologists have also made important contributions to process reliabilism.Footnote 1 Perhaps the earliest explicit formulation of a reliabilist theory, due to Ramsey (Reference Ramsey and Braithwaite1931), also appealed to the reliability of the belief-forming process (though Ramsey’s view was proposed as a theory of knowledge rather than justification).

How should we understand the notion of a belief-forming process? The background thought is that different cognitive processes are responsible for different beliefs. Compare my current perceptual belief that there is a dog outside my window with my recollection that I ate foie gras for breakfast this morning. If asked to describe the process responsible for the former belief, a natural answer would be vision. If asked to name the process responsible for the latter belief, a natural answer would be memory. For process reliabilists, the key idea is that the justificatory status of the belief depends on the reliability of the process that caused it. If my vision is reliable, then my resulting belief that there is a dog outside my window is justified.

Now, there are tricky issues about how to describe the relevant belief-forming processes. For example, why describe the process responsible for my belief about the dog as vision, rather than vision of a dog, or vision of an animate creature formed in good lighting conditions on a Tuesday afternoon? This turns out to be one of the main challenges to reliabilism: the “Generality Problem.” We’ll discuss this issue in detail in Section 3.4.

Process reliabilism is not the only reliabilist theory of justification.Footnote 2 But it is the most well-developed and prominent reliabilist theory of justification. For this reason, it will serve as our primary focus, though I will highlight differences with other reliabilist theories when they prove relevant.

1.2 What Is Reliability?

What does it mean for a process to be “reliable”? Typically, reliabilists hold that a process is reliable if it tends to produce true beliefs rather than false beliefs (Goldman Reference Goldman and Pappas1979, Reference Goldman1986; Lyons Reference 77Lyons2009). The underlying thought is that we can define reliability in terms of a regular tendency to produce successful outputs. For example, a reliable vending machine tends to successfully deliver whatever item one has selected. Similarly, a reliable belief-forming process usually produces successful beliefs rather than unsuccessful beliefs. This is then combined with the idea that truth is the epistemic success condition for belief: A belief is successful, from the epistemic point of view, if and only if it is true.Footnote 3

How should we understand a tendency to produce true beliefs? Perhaps the most common understanding is that a process tends to produce true beliefs if it produces a high ratio of true to false beliefs in some relevant domain of situations (Goldman Reference Goldman and Pappas1979). This proposal calls for clarification on two fronts.

The first concerns how to define the relevant domain of situations. One option is to say that the relevant situations are those which are nearby to the world of the believer. Another is to say that the relevant situations are those where conditions are normal for the operation of the belief-forming process. We’ll discuss these options – and some others – in more detail in Section 3.

On to the second point of clarification: How reliable does a process need to be? According to Goldman (Reference Goldman and Pappas1979), we should not expect a precise answer. Our ordinary concept of justification is vague. This is, Goldman thinks, not a problem for reliabilism: We should only expect precision in an analysis to the extent we find precision in the analysandum (the concept we are trying to analyze). Consider an analogy with other gradable adjectives, such as “tall” and “expensive.” We should not expect an analysis of our ordinary concept expensive to deliver a precise cut-off for what counts as expensive.

1.3 Reliabilism about Justification v. Reliabilism about Knowledge

This Element will focus on reliabilism as a theory of justified belief. However, it is worth noting that some philosophers present reliabilism as a theory of knowledge. As previously noted, one of the earliest reliabilist proposals was due to Ramsey (Reference Ramsey and Braithwaite1931), who proposed that a belief amounts to knowledge if it is true, certain, and reliably formed.

Several other theories of knowledge have strong reliabilist affinities. For example, Goldman’s (Reference Goldman1967) causal theory of knowing held that A knows p if and only if there is an appropriate causal connection between the fact that p and A’s belief that p. This view has clear reliabilist elements. Specifically, the emphasis on the causal processes responsible for the belief is a key feature of reliabilism (more on this later).

Or consider so-called “truth-tracking” theories of knowledge. The basic idea behind these theories is that a belief amounts to knowledge if it reliably tracks the truth. To illustrate with an analogy from Feldman (Reference Feldman2002), consider a thermometer that is perfectly reliable. Part of what this means is that if it is 98 degrees outside, the thermometer will read “98.” Moreover, if it were not 98 degrees outside, the thermometer would not read “98.” In such circumstances, we might be willing to say the thermometer “knows” the temperature. According to truth-tracking theories, this metaphorical knowledge is pretty much the way real knowledge works: knowledge involves having beliefs that reliably track facts in the world.Footnote 4

There are different ways of spelling out the relevant sense of “tracking.” Nozick (Reference Nozick1981) developed this idea in terms of a condition he called “sensitivity”:

Sensitivity: Suppose A believes p using method X. Then A’s belief amounts to knowledge only if in the nearest possible worlds where p is false and A uses X to arrive at a belief about whether p is true, A does not believe p.Footnote 5

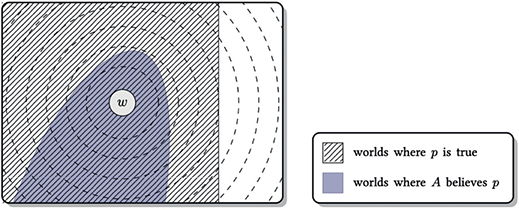

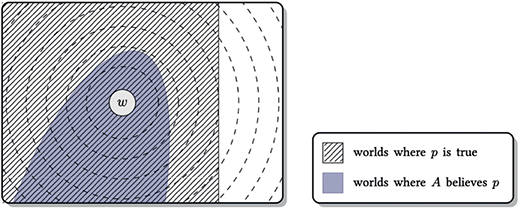

For example, suppose I look out of my window and come to know that there is a dog outside. According to sensitivity, this requires that in all the most similar scenarios where there is not a dog outside but I still look out of my window, I do not come to (falsely) believe that there is a dog outside. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1 A sensitive belief. (At none of the nearest worlds to w where p is false is p believed.)

More recently, some epistemologists have proposed a slightly different truth-tracking condition, called “safety”:

Safety: Suppose A believes p using method X. Then A’s belief amounts to knowledge only if in the nearest possible worlds where A believes p using X, p is true.Footnote 6

To illustrate using the dog example: According to Safety, if I come to know that there is a dog outside my window, this means that in the most similar scenarios where I look out of my window and form the belief that there is a dog outside, my belief is true: There is a dog outside.

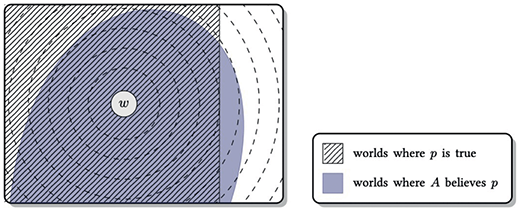

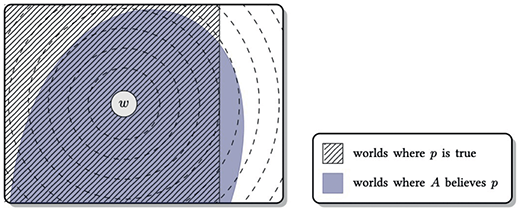

Both sensitivity and safety can be viewed as ways of articulating a reliabilist condition on knowledge. Both claim that knowledge involves reliably tracking the truth; they just differ in the range of scenarios across which reliability is required. Sensitivity focuses on scenarios where the relevant proposition is false: The question is whether the agent avoids believing a falsehood in those scenarios. Safety looks at nearby scenarios where the agent forms the same belief, asking whether the agent’s belief is true in those scenarios. (See Figure 2.)Footnote 7

Figure 2 A safe but insensitive belief. (At all the nearest worlds to w where p is believed, p is true. But at the nearest worlds where p is false, p is still believed.)

How do these proposals relate to process reliabilism? There are clear similarities. Both sensitivity and safety assign an important role to the method responsible for the belief, which seems roughly the same as the process which caused the belief (talk of “methods” and “processes” seems interchangeable). But unlike process reliabilism, sensitivity and safety are factive conditions: If a belief is either sensitive or safe, it follows that it is true. By contrast, most process reliabilists want to allow that reliability is compatible with error. Most hold that the threshold for reliability is not 100 percent, so a belief can be reliably formed yet still false. This difference can be traced to the different properties of knowledge and justification. Knowledge is factive: If a belief amounts to knowledge, it is true. By contrast, most philosophers have thought that it’s possible to have justified false beliefs.

This difference illustrates a more general point. We should expect some differences between a reliabilist condition on knowledge and a reliabilist condition on justification, given the important differences between knowledge and justification.

1.4 The Revolutionary Nature of Reliabilism

By now, “reliabilism” is part of our shared philosophical vocabulary. But when it was first introduced, reliabilism was a revolutionary idea. Indeed, much of the ongoing resistance to reliabilism stems from the radical nature of its central claims.

What makes reliabilism so radical? In retrospect, we can view reliabilism as a leading character in two closely related philosophical revolutions – what we might call the “externalist revolution” and the “causal revolution.”

1.4.1 The Externalist Revolution

Historically, many philosophers have thought about justification in “internalist” terms. Roughly, they have sought to explain justification in terms of factors that are accessible to an individual’s mind. A particularly clear version of this internalist orientation can be found in Descartes’ Meditations. Descartes can be interpreted as posing a version of our starting question: Which beliefs are justified? To answer this question, he considers a series of skeptical possibilities designed to cast doubt on his beliefs. If he can discern no grounds for rejecting some skeptical hypothesis h, then he provisionally rejects any beliefs that are incompatible with h. Crucially, the grounds in question are internalist grounds: They are sensory experiences or a priori considerations that are accessible to Descartes from his armchair.Footnote 8

This internalist tradition also has many contemporary adherents. Consider evidentialism, the view that justification is a matter of evidential support. This view is often considered the main rival to reliabilism. (Though whether they are necessarily rivals can and should be questioned; indeed, this will be one of the major themes of this Element.) While there are different ways of articulating evidentialism, a common formulation goes like this:

Evidentialism: Necessarily, S is epistemically justified in believing p at time t iff S’s total evidence supports believing p at t.Footnote 9

Evidentialism is not wedded to internalism. All depends on how we unpack the notions of evidence and evidential support. That said, most evidentialists have been internalists. For example, Conee and Feldman (Reference Conee, Feldman and Smith2008) defend a picture on which an agent’s ultimate evidence consists in their experiences. One possible motivation for this picture comes from the idea that we have privileged introspective access to our experiences. If justification is entirely a function of evidence, and evidence itself consists in mental states to which we have armchair access, then justification depends entirely on facts that are accessible to us – or so the thought goes.Footnote 10

Reliabilism marks a sharp break with this internalist tradition. According to reliabilism, the ultimate grounds for justification are facts about the reliability of our belief-forming processes. Whether a belief-forming process is reliable is typically not something that will be accessible to the believer from the armchair. This is because whether a process is reliable typically depends on contingent facts about what the world is like. For example, vision is typically a reliable way of forming beliefs about objects in one’s immediate surroundings. But suppose we lived in a world where optical illusions and mirages were commonplace. In such a world, vision would be unreliable.

This aspect of reliabilism has a surprising and – in the eyes of some – disconcerting consequence: There is an element of luck in whether we are justified in believing something. Two people can be alike “from the inside”: They can have all the same experiences and phenomenal states, yet one of their beliefs is justified and the other not. This consequence forms the backbone of a major objection to reliabilism – the “new evil demon problem” (to be discussed in Section 3).

1.4.2 The Causal Revolution

Another distinctive feature of reliabilism is its emphasis on causal factors. For reliabilists, the justificatory status of a belief depends on the reliability of the process that caused that belief. Much of the internalist tradition described earlier focuses on the epistemologist’s job as a constructive or ameliorative project: The aim of the game is to construct a new and improved positive rationale for our beliefs. This approach typically pays little attention to the question of what factors have caused ordinary people’s beliefs. At least for Descartes, there was a presumption that whatever factors had causally sustained these beliefs in the past were epistemically inadequate, which is why a new philosophical rationale is needed. By contrast, reliabilism puts the causal question front and center.

In this regard, reliabilism can be viewed as part of a larger causal revolution that occurred in the mid twentieth century. This movement sought to analyze a variety of concepts in causal terms. Some examples:

Causal Theories of Perception. For an influential early example, consider Grice’s causal theory of perception (Grice Reference Grice1961). Suppose you go out celebrity-spotting in Hollywood and you see your favorite celebrity, Nicolas Cage. According to Grice, part of what is involved in seeing Nicolas Cage is for you to have a certain visual experience that is caused, in an appropriate way, by Nicolas Cage. If instead, your visual experience was caused by a Cage doppelganger, or by a Madame Tussaud’s wax sculpture, then you did not see Nicolas Cage.Footnote 11

Causal Theories of Content. Around the same time that process reliabilism was developed, various philosophers explored the idea that mental and semantic content can be explained in causal terms. Causal theories of content come in different forms. But to illustrate the basic idea, consider my concept of my next-door neighbor, Fred. According to causal approaches, part of what makes my concept about Fred – rather than, say, about his identical twin, or someone else named “Fred” – is that I have causally interacted with Fred.Footnote 12

Thus, reliabilism is a contribution to a multifaceted research program seeking to explain philosophical concepts in causal terms.

The causal aspect of reliabilism is closely tied to its historical dimension. The factors that caused a belief are part of its history. Consequently, reliabilists hold that the history of a belief determines whether that belief is justified. Process reliabilism thus stands opposed to current “time-slice” theories, which maintain that the justificatory status of a belief at time t is entirely a function of facts that obtain at time t.Footnote 13

Having articulated some key reliabilist concepts, I now turn to consider why many philosophers have found reliabilism an attractive view.

2 The Appeal of Reliabilism

Why think justification has anything to do with reliability? This section highlights some reasons for finding reliabilism attractive. Along the way, I discuss whether rival theories – such as internalist evidentialism – can claim the same advantages.

2.1 Capturing Paradigm Cases

An initial motivation for reliabilism is its ability to capture paradigm cases of justified and unjustified beliefs. Consider: What are some processes that typically cause unjustified beliefs? Goldman answers:

Here are some examples: confused reasoning, wishful thinking, reliance on emotional attachment, mere hunchwork or guesswork, and hasty generalization. What do these faulty processes have in common? They share the feature of unreliability: they tend to produce error a large proportion of the time.

What are some processes that typically yield justified beliefs? Goldman answers:

They include standard perceptual processes, remembering, good reasoning, and introspection. What these processes seem to have in common is reliability: the beliefs they produce are generally true.

Goldman’s observations strike me as correct. Many paradigm instances of epistemically “good” (justification-conferring) processes are reliable, and similarly, many paradigm instances of epistemically “bad” (unjustified belief-producing) processes are unreliable.

While this point is suggestive, as an argument for reliabilism it has two limitations. First, there might be other properties besides reliability that “good” processes have in common. Evidentialists will stress that Goldman’s examples of good processes also typically result in evidentially supported beliefs. Similarly, Goldman’s examples of bad processes typically result in beliefs that are not evidentially supported. Evidentialists may claim that our intuitions are being driven by the presence or absence of evidential support rather than reliability. Second, it is not obvious that all beliefs resulting from reliable processes are intuitively justified, or that all beliefs resulting from unreliable processes are intuitively unjustified. Many of the putative counterexamples to reliabilism purport to show that this is not the case (more on this in the next section).

2.2 The Truth Connection

Another argument for reliabilism is more theoretical. Reliabilism captures the idea that there is an important connection between justification and truth.

We care about having true beliefs. That is:

Truth Goal: All else equal, we want to have true beliefs and to avoid having false beliefs.Footnote 14

We also care about having justified beliefs. As noted in the Introduction:

Justification Goal: All else equal, we want to have justified beliefs, and to avoid having unjustified beliefs.

What is the connection between the Truth Goal and the Justification Goal? Are these just completely separate things we happen to care about from the epistemic point of view? Such a disconnect seems both implausible and theoretically dissatisfying. Surely there is some unifying thread explaining why both truth and justification are epistemically valuable.

Reliabilism offers a way of drawing this connection. Justified beliefs are truth-conducive: They are formed in a manner that tends to yield the truth. So achieving the Justification Goal is conducive to attaining the Truth Goal.Footnote 15

This is a selling point, to be sure. But is this selling point unique to reliabilism? Consider evidentialism. As we will see shortly, many evidentialists explain evidential support in probabilistic terms: A belief is supported by the evidence if it is likely to be true, given the evidence. Evidentialists might claim that this secures a connection between justification and truth: If someone achieves the Justification Goal, their belief is likely to be true, given their evidence.

This is right, as far as it goes. But exactly what sort of connection the evidentialist establishes between justification and truth depends on how we understand evidential probability. As we have seen, many evidentialists understand evidence and evidential support in purely internalist terms. Consequently, a person’s belief can satisfy the (internalist) evidentialist’s condition even if their belief is anti-reliable – that is, it is formed in a manner that leads to falsehood far more frequently than truth. By the reliabilist’s lights, this calls into question whether this provides a sufficiently robust connection between justification and truth to be worth caring about. This marks one of the major divisions between reliabilists and internalists.Footnote 16

2.3 Naturalistic Reduction

2.3.1 Reliabilism’s Reductive Ambitions

Another motivation for reliabilism is its naturalistic payoff. Reliabilism explains justification using non-epistemic, naturalistic concepts. This motivation played a prominent role in Goldman’s Reference Goldman and Pappas1979 paper, where he declares, “I want a theory of justified belief to specify in non-epistemic terms when a belief is justified” (90). To introduce some helpful terminology, let us call a theory “naturalistically reductive” if it satisfies this goal – that is, if it explains justification without recourse to any epistemic concepts.

What is an “epistemic” concept? It is hard to give a precise account of the epistemic/non-epistemic divide. But, very roughly, epistemic terms are those studied by epistemologists, for example, “knows,” “has evidence that,” “is rational in believing,” and so on. For reliabilists, justification is a matter of reliability. Reliability is a non-epistemic notion: It is a matter of tending to produce true beliefs.Footnote 17

Why hanker after a reductive theory? Consider examples of successful reduction in science: say, the reduction of temperature to average kinetic energy, or the reduction of chemical properties to atomic physics. These are widely regarded as great achievements. They are great achievements, at least in part, because they enable us to see how different parts of the world fit together. Chemical properties do not “float free” of the underlying atomic properties. By reducing the former to the latter, we integrated the two into a unified worldview. Naturalists in epistemology have a similar goal. Epistemic properties do not float free from non-epistemic properties; the former depend on the latter. A naturalistically reductive view would allow us to see how epistemic properties fit into the natural world.

2.3.2 Comparison with Evidentialism

This marks a potential advantage of reliabilism over evidentialism. Evidentialists explain justification in further epistemic terms – namely, whether an agent’s evidence supports believing some proposition.

Closer examination reveals that evidentialists rely on two epistemic notions in their analysis. First, evidentialists explain justification in terms of the believer’s evidence – that is, the evidence that the believer possesses. Second, evidentialists say that justification is a function of whether someone’s (possessed) evidence supports believing some proposition. So evidentialists invoke two epistemic notions: (i) the notion of possessing some evidence e; and (ii) the notion of e supporting some belief.

Of course, there is nothing to stop evidentialists from providing a naturalistic reduction of these notions. But the devil is in the details. And spelling out these devilish details is harder than has been traditionally recognized. So it is worth taking a brief excursion into the evidentialist’s options and seeing what obstacles arise. (Readers uninterested in the nuts and bolts of evidentialism’s reductive prospects should feel free to skip ahead to Section 2.4.)

2.3.3 Explaining Evidence Possession

According to one influential version of evidentialism, an agent’s evidence at time t consists in some of their mental states at t. On the face of it, this would seem to be a purely naturalistic approach of evidence possession: There does not seem to be anything inherently epistemic about the notion of being in some mental state. However, things are not so simple. Complications arise when we ask: Which mental states make the cut? Presumably not all of them. Suppose someone has a memory that is so deeply repressed that it would take years of extensive therapy to unearth. Most evidentialists would not want to consider this memory part of the agent’s evidence (McCain Reference McCain2014: 35). This is particularly true of internalist evidentialists who claim that justification depends only on features of the agent’s mental life that are accessible to them.

Partly for this reason, many evidentialists have identified an agent’s evidence with a particular subset of their mental states: Their experiences or their seemings (i.e., the way things seem to them).Footnote 18 But does this restriction solve the problem? It’s doubtful that we always enjoy untrammeled access to our own experiences. I might experience a mild feeling of envy toward a colleague’s success without being in a position to recognize that my experience is one of envy. Even if we restrict ourselves to still further to perceptual experiences or seemings, the problem persists. To take an example from Chisholm (Reference Chisholm1942): I might have a fleeting experience of a speckled hen, without having access to the exact number of speckles. In a similar vein, Schwitzgebel (Reference Schwitzgebel2008) reports a range of empirical studies indicating that people are frequently mistaken about certain aspects of their perceptual experiences (e.g., the extent of their visual field). Thus insofar as evidentialists want to maintain an accessibility constraint on evidence, they should deny that all of an agent A’s experiences – even all of A’s perceptual experiences – comprise A’s evidence.

Could evidentialists avoid the problem by just defining evidence in terms of accessibility? One might propose that an agent’s evidence at time t is whatever mental states (or experiences specifically) the agent can access at t. The worry with this move is that “accessibility” appears to be an epistemically loaded notion. For a mental state to be accessible, in the relevant sense, is for the agent to be in a position to justifiably believe (or rationally believe, or know) that they are in that state. So if we define evidence in terms of accessibility, the resulting account of justification will not be naturalistically reductive. Worse, if the notion of accessibility is defined in terms of “justification” specifically, then the resulting account will be circular: We will have defined justification in terms of evidence, which is in turn defined in terms of justification.Footnote 19

This is not to suggest that evidentialists have no other resources available. From the perspective of this Element, one attractive strategy would be to explain accessibility in terms of reliability. For example, one might identify an agent’s evidence as those mental states which the agent can reliably form beliefs about, or which serve as the inputs to their reliable processes. I explore such ideas in more detail in Section 5. For now, the important point is that any such move would mark a big departure from a “pure” internalist evidentialism, and a major step toward the reliabilist camp.

2.3.4 Explaining Evidential Support

Even if the evidentialist can unpack evidence possession in non-epistemic terms, there remains the question:

Evidential Support Question: How should we understand evidential support? What does it take for evidence e to support believing p?

One common way of explaining evidential support is probabilistic. According to probabilistic views, e provides some support for a proposition p just in case it raises the probability of p:

Support as Probability-Raising: Evidence e supports p iff Pr(p|e) > Pr(p).

Evidentialists might suggest an agent’s possessed evidence supports a belief just in case it boosts the probability of this belief’s content above some threshold:

Probabilistic Account of Belief Support: Evidence e supports believing p iff Pr(p|e) > t, where t is some threshold.

But how should we understand the probability function involved?

One approach says that Pr represents the subjective degrees of belief, also known as credences, of the agent. For subjective Bayesians, there are no constraints on these credences save internal coherence requirements (specifically, the requirement that the agent’s credences obey the probability axioms) and the diachronic requirement to update by conditionalizing on one’s total evidence. Credences are psychological states, which presumably can be understood in non-epistemic terms. So this approach is naturalistically reductive. But it is too permissive. To take an example from Greco (Reference Greco2013), suppose an agent starts off assigning credence 1 to the proposition that space invaders are lurking in our midst, and that to protect ourselves, we need to wear tin hats. Then for any evidence the agent gets that is logically consistent with this proposition, the probability of this proposition conditional on the agent’s evidence will be 1. But it seems absurd to say that this agent’s evidence supports believing this proposition, or that their resulting belief is justified.

This suggests that Pr cannot be any old credence function. Rather, Pr must represent epistemically rational or justified credences. But then we’ve just pushed our question back a step: How can we explain what it is for a credence to be epistemically rational or justified in non-epistemic terms?Footnote 20

This is not to suggest that no answer can be provided. Here too, we might try to answer this question using reliabilist resources. I revisit this possibility in detail in Section 5.3.

2.4 Anti-Skeptical Payoff

2.4.1 Enter the Skeptic

Right now, the following seems to you to be true:

CHAIR: You are sitting in a chair, reading this book.

(Ok, I don’t actually know if you seem to be sitting in a chair, but play along.)

Enter our old friend the skeptic. They start by spinning a yarn. You are not really sitting in your chair right now, reading a book. Rather, you are the victim of an evil demon, who has given you the illusion of sitting in a chair. Or you are a brain in a vat, plugged into a computer that is running a program designed to simulate your reading environment. Next, the skeptic claims that you cannot rule out the possibility that their tale is true. From this, they draw the conclusion that you cannot be justified in believing CHAIR.

2.4.2 Enter the Reliabilist

Reliabilism offers a straightforward response. According to process reliabilists, we need to ask: “What is the process responsible for your belief in CHAIR?” Presumably, the answer involves your visual and haptic senses. Next, we ask, “Are your senses reliable?” If, as a matter of fact, you are not in a skeptical scenario, the answer is plausibly yes. According to our common-sense understanding of the world, the senses typically yield true beliefs. If this common-sense conception of the world is correct, your belief in CHAIR is justified. The mere conceivability of vivid skeptical scenarios does not impugn the justificatory status of your beliefs.

Some find this reliabilist response unsatisfying. A natural reaction is to say, “But we can’t tell whether our beliefs about the external world are produced by reliable processes! To assert that they are is to assume the very point at issue.” This response – while initially tempting – faces two problems. The first is a dialectical point. The justificatory skeptic claims that justified beliefs about the external world are impossible: You cannot be justified in believing CHAIR regardless of what the world is like. That is, the justificatory skeptic says that even if the external world is exactly as common sense tells us, you still cannot be justified in your beliefs about the external world. The reliabilist shows how we can deny this. The reliabilist offers a possibility proof for justification: If both reliabilism and our common-sense understanding of the world are correct, then many of our beliefs about the external world are justified, contrary to what the skeptic claims.

Second, we should scrutinize the claim that we cannot tell whether our beliefs about the external world are produced by a genuinely reliable process. Here’s something you also believe:

REL: My belief in CHAIR is justified.

What is the process responsible for your belief in REL? The answer may well be complex; it might involve, inter alia, your memory of your senses’ past track record (e.g., that they tend not to lead you astray). Call whatever process is responsible for your belief in REL, ‘PREL.’ Now, the reliabilist can make the same move as before: If PREL is reliable, then your belief in REL is justified. If so, there is a real sense in which you can tell that your beliefs about the external world are produced by a reliable process. You can tell this in the sense that you can justifiably believe that they are so produced.

Admittedly, you cannot tell this in a way that is likely to convince the skeptic. You cannot point to any features of your experiences that prove that the skeptical hypothesis is false. But, according to reliabilists, providing such a proof is not required for justification. This is a key part of the externalist revolution.

2.4.3 Enter the Evidentialist

So the reliabilist offers a simple response to the skeptic. What does the evidentialist say? Here much depends on how we flesh out the details. As we saw, many evidentialists identify your evidence with certain experiences. And these experiences are often taken to include various appearances or seemings. They might thus think that your current evidence includes the proposition:

APPEARS: It appears that you are sitting in a chair, reading this book.

But how does this approach answer this skeptic? Why think that APPEARS supports believing CHAIR?

Evidentialists might point out that since CHAIR makes APPEARS very likely (Pr(APPEARS|CHAIR) ≅ 1), and since we shouldn’t in general expect to have appearances of sitting in chairs, it follows from Bayes’ theorem that Pr(CHAIR|APPEARANCES) > Pr(CHAIR). Consequently, APPEARS provides at least some evidence for CHAIR. But this point does not get us very far. After all, compare CHAIR with the corresponding skeptical hypothesis:

DEMON-CHAIR: You are not really sitting in a chair, reading this book, but an evil demon is giving you the illusion of doing so.

By analogous reasoning, we can show that Pr(DEMON-CHAIR|APPEARS) > Pr(DEMON-CHAIR) – that is, the appearance of being in a chair provides some evidence that a demon is deceiving you into sitting in a chair.Footnote 21 So what is the basis for concluding that APPEARS favors CHAIR over DEMON-CHAIR?Footnote 22

3 Headaches for Reliabilists

In the last section I painted a rosy picture of reliabilism, highlighting its explanatory virtues and advantages over rival theories. But not all is smooth sailing. Reliabilism faces a litany of challenges – challenges that have persuaded many epistemologists that reliabilism is untenable. This section reviews some of the most pressing challenges for reliabilists, along with some responses.

Here I focus on three types of challenges. First, challenges to the idea that reliability is necessary for justification; second, challenges to the idea that reliability is sufficient for justification; and third, challenges to the idea that there is a fact of the matter about which process is responsible for an agent’s belief on a given occasion.

3.1 The New Evil Demon Problem

3.1.1 The Problem

The most famous objection to the idea that reliability is necessary for justification is the “New Evil Demon Problem” (Cohen Reference Cohen1984; see Graham Reference Grahamforthcoming for a state-of-the-art discussion). Consider:

Renée and the Demon. Renée’s life seems perfectly ordinary. Alas, her perceptual experiences (and those of anyone else who inhabits her world) are caused by an evil demon hell-bent on deceiving Renée. When she seems to pick up her coffee cup in the morning, this is just a demon-induced illusion: there is no coffee cup in front of her. When she seems to scoop up her dog’s poop on the walk, this is really … Well, you get the picture.

A common intuition about this case is that Renée’s perceptual beliefs are justified. For example, when she appears to see a tree in front of her, she is justified in believing that there is a tree in front of her. This poses a problem for reliabilism about justification.Footnote 23 At Renée’s world, perception is systematically unreliable, thanks to the demon’s machinations.

The New Evil Demon Problem is not just a problem for reliabilism. It threatens a wide variety of externalist views of justification. For example, it also poses a problem for hardline “knowledge first” views, according to which a belief is only justified if it amounts to knowledge.

Partly for this reason, some have regarded Renée and the Demon as a counterexample not just to reliabilism, but to any externalist theory. After all, the thought goes, the reason why we judge Renée to be justified is that her situation is internally indistinguishable from someone in the “good case” – that is, her counterpart who is not demonically deceived. And this, in turn, has suggested to some that justification supervenes on internally accessible states.

3.1.2 Bullet-Biting

One response is to deny that Renée is justified in holding her perceptual beliefs. Proponents of this response usually concede that Renée’s beliefs have some positive epistemic status. But they deny that this status is the same as justification.

What is this positive status, if not justification? A couple of answers have been proposed.

Conditional Reliability. One answer, suggested by Lyons (Reference Lyons2013), appeals to conditional reliability. Consider a process such as believing the conjunction of your other beliefs. Is this process reliable? Yes, if your other beliefs are true; no, if they are false. According to Goldman (Reference Goldman and Pappas1979) and Lyons (Reference Lyons2013), we can evaluate a belief-dependent process along these lines (i.e., a process that takes other beliefs as input) for conditional reliability – that is, whether it typically delivers true outputs when it operates on true input beliefs.

Lyons (Reference Lyons2013) suggests that there is a positive status associated with being the output of a conditionally reliable process, and that many of Renée’s beliefs enjoy this status. Suppose Renée has various perceptual beliefs – she is drinking coffee, birds are chirping nearby – and from these beliefs she infers their conjunction. The belief in their conjunction was formed by a conditionally reliable belief-dependent process (conjunction introduction). Because of this, her conjunctive belief possesses a positive epistemic status, even though this status does not rise to the level of justification.Footnote 24

Does this response solve the problem? Let me flag two worries. First, as Lyons recognizes, this response only delivers the conclusion that Renée’s inferential beliefs have some positive epistemic status. But her non-inferential beliefs – which presumably include her basic perceptual beliefs – lack this positive status. After all, these beliefs are the outputs of a belief-independent process, which is straightforwardly unreliable. While Lyons embraces this consequence, those who feel the force of the New Evil Demon intuition may be left dissatisfied.

Second, we might question whether conditional reliability is, on its own, anything to write home about. Suppose Ken believes a host of absurdities: The moon is made of cheese, techno music is the highest form of art, cats are better than dogs, and so on. And suppose Ken infers the conjunction of these beliefs. In doing so, he uses a conditionally reliable belief-forming process. But does this mean that his resulting conjunctive belief has some valuable epistemic property, albeit one that falls shy of justification? This seems dubious. Intuitively, his conjunctive belief is just as absurd, and just as epistemically criticizable, as the most epistemically offensive of its conjuncts.

Blamelessness. An alternative answer is to say that while Renée’s beliefs are not justified, they are epistemically blameless (Williamson forthcoming). Proponents of this approach emphasize that there is a distinction between (i) complying with a norm N, (ii) blamelessly violating N. For example, suppose the speed limit is 60 mph. Suppose my speedometer has just stopped working, but I have no reason to suspect it is broken. As a matter of fact, I am driving 61 mph, but my speedometer says I’m doing 59. I have broken the norm set by the speed limit, but I have done so blamelessly, because I have a good excuse for my violation.

I think proponents of this response are right that norm violation can come apart from blameworthiness. However, it’s not clear that this gives us a full solution to the problem, for two reasons. First, there is a residual intuition that Renée is, in some sense, complying with her epistemic obligations. Suppose Renée has the perceptual experience of sipping a coffee. What doxastic state should she adopt? Should she believe she is not sipping coffee? Should she suspend judgment on the question altogether? Neither seems right. This provides some reason to think that Renée is not merely blameless for holding her beliefs. She is – in some sense – believing as she should (cf. Schechter Reference Schechter and Carter2017).

There is also a more general worry about the bullet-biting response. Proponents of the bullet-biting response are committed to an error theory. They claim that when we intuit that Renée’s belief is justified, we are making a mistake. Specifically, we are confusing two distinct statuses: Justification and blamelessness. (Other versions of the bullet-biting response will say something similar, just swapping out blamelessness with another epistemic status.) But it is questionable whether we have any independent reason to think that people are systematically confused on the distinction between justification and blamelessness.

These concerns provide some motivation for considering alternatives to the bullet-biting response. Is there any way to square reliabilism with the intuition that Renée’s beliefs are justified?

3.1.3 Attributor Reliabilism

One strategy for reconciling reliabilism with the New Evil Demon intuition is to reconsider which worlds to use when evaluating the reliability of a process. A process can be reliable at one world, but unreliable at another. Perception is reliable at our world (we hope!), but not at Renée’s world. The New Evil Demon objection tacitly assumes that reliability should be indexed to the world inhabited by the subject of the justification ascription (i.e., the believer’s world). But perhaps we should reject this assumption.

If reliability is not indexed to the subject’s world, then what world should we use when assessing processes for reliability? One possibility is to index it to the world of the attributor – that is, the person who is ascribing justification. Here’s one way of fleshing this out:

Attributor Reliabilism: An utterance of “A’s belief is justified” is true, as evaluated at a world of evaluation w iff A’s belief is formed by a process that is reliable at w (i.e., A’s belief-forming process is disposed to produce true rather than false beliefs at w).Footnote 25

How does this help with Renée and the Demon? The key idea is that the world of evaluation might differ from the world inhabited by the subject of the justification ascription. Suppose we ascribe justification to Renée by saying, for example:

(1) Renée is justified in believing there is a tree in front of her.

Let ‘@’ denote our world – the world of people attributing justification to Renée by uttering (1). According to Attributor Reliabilism, we will evaluate the reliability of Renée’s belief-forming process at @, not at the demon world (wD) which Renée inhabits. Since perception is reliable at @, Attributor Reliabilism predicts that our utterance of (1) is true.

Is this solution satisfactory? Consider the demonic architect of Renée’s world. Suppose this demon, sitting atop their demon throne in their demon world (wD), is watching over Renée. This demon pronounces:

(2) Renée is not justified in believing there is a tree in front of her.

Attributor Reliabilism predicts that (2) is true, as evaluated at wD.

We can take this argument a step further. Suppose this demon now turns his gaze toward @ and considers us, and pronounces:

(3) Their perceptual beliefs are not justified.

Attributor reliabilism predicts that (3) is also true, as evaluated at wD.

Whether this is a devastating problem is open for debate. Attributor reliabilists may retort that we don’t have clear pre-theoretic intuitions about the truth-values of justification ascriptions at distant worlds. Rather, when we evaluate a justification ascription for truth or falsity, we are evaluating it for truth or falsity at our world. Attributor Reliabilism predicts that (2) and (3) are false as evaluated at our world.

3.1.4 Normal Worlds Reliabilism

Another option is to index reliability to normal worlds:

Normal Worlds Reliabilism: S’s belief is justified iff it is formed by a process that is reliable in normal worlds.

The guiding thought is that Renée’s demon world is abnormal. Perhaps the abnormality of her circumstances is what deprives her belief of justification. But how should we understand this notion of “normal worlds”?

Goldman’s Account of Normal Worlds. In Epistemology and Cognition, Goldman suggested that the normal worlds are worlds consistent with our “general beliefs” about the sorts of objects, processes, and events that obtain in the world (Reference Goldman1986: 107). This definition makes normality dependent on whatever we happen to believe about the world. Some have wondered whether this dependence makes the notion ill-suited to play a foundational role in a theory of justification. Pollock and Cruz (Reference Pollock and Cruz1999) raise the worry that if our general beliefs about the world are not themselves justified, then they shouldn’t get to play a role in determining the justificatory status of beliefs. Graham (Reference Grahamforthcoming) raises the concern that these general beliefs about the world may turn out to be inconsistent. If so, does that mean that there are no normal worlds? Yet another worry is that this way of defining normality reintroduces the sort of relativity that some find troubling about Attributor Reliabilism. Imagine a demon world where it is generally known that perception is unreliable. The worlds that are normal from the perspective of that world will be other demon worlds.

Faced with these objections, some might be tempted to abandon Normal Worlds Reliabilism altogether. But perhaps that would be too hasty. Perhaps we should instead cast about for a different understanding of normal worlds …

Functionalist Accounts of Normal Worlds. Another option is to relativize normality to belief-forming processes:

Process-Relative Normal Worlds: The normal worlds, for a belief-forming process X, are those where conditions are normal for the operation of X.

On this account, different sets of worlds will be “normal” for different belief-forming processes.

This might just seem to push things back a step: How should we understand “conditions that are normal for the operation of a belief-forming process”? One strategy is to unpack this notion in functionalist terms. Roughly:

Functionalist Account of Normality: The conditions that are normal for the operation of a process X are conditions in which X can fulfill its function.

Versions of this idea have been developed, in somewhat different forms, by Burge (Reference Burge2003, Reference Burge2010), Graham (Reference Graham2012, forthcoming), Kelp (Reference Kelp2019), and Simion (Reference Simion2019).Footnote 26

Applied to Renée: Renée has the misfortune of inhabiting a world where her perceptual systems cannot fulfill their functions. After all, the function of perceptual systems is to accurately track various features of the world. Renée’s demonic deceiver has ensured that her perceptual systems cannot do this at her world (wD). If she were in a world like ours, Renée’s perceptual systems would be able to fulfill their functions. Consequently, the normal worlds for Renée’s belief-forming process are worlds like ours.

How should we understand talk of the “function” of belief-forming processes? One influential approach explains functions in etiological terms. On Wright’s (Reference Wright1973) account:

Wright Functions: The function of X is Z iff:

(1) X is there because it does Z, and

(2) Z is a consequence of X’s being there.

For example, the function of the heart is to pump blood because (i) hearts are around because they pump blood; and (ii) pumping blood is a consequence of hearts being there. Applied to a belief-forming process such as vision, one might hold that the function of vision in creatures like us is to enable accurate representation of distal objects in one’s environment. This is because (i) creatures like us have vision because it enables such representations; and (ii) enabling accurate representations of distal objects is a consequence of vision.

This is an attractive approach. But I want to highlight a complication. The foregoing paragraph applied a Wright-style etiological account of function to vision in creatures like us. What about creatures like Renée? We are not told Renée’s biographical or biological backstory. If Renée came from a world like ours and was transplanted to a demon world, the etiological account will say her vision has the same function that vision has at our world. But what if Renée and her ancestors always inhabited a demon world? What if Renée’s vision (and that of her ancestors) never managed to accurately track features of the world? Then a Wright-style account of functions seems to predict that vision in Renée has no function, or, at least, it does not have the function of accurately tracking features of the world. So we seem to be saddled with the result that, in this version of the story, there are no normal worlds for Renée – no worlds, that is, where conditions are normal for the operation of her perceptual systems.

Some might embrace this result: If Renée really comes from a world where vision has no function at all, then her perceptual beliefs are not justified.Footnote 27 But some might find this a bitter pill to swallow. We might wonder: Is this really more palatable than the more straightforward bullet-biting response (Section 3.1.2)?

Parallels in the Theory of Knowledge. Normal Worlds Reliabilism remains a topic of continued interest among epistemologists. It also parallels recent proposals in the theory of knowledge. Several philosophers in the last decade have proposed broadly reliabilist accounts of knowledge where normality plays a prominent role. For example, Greco (Reference Greco2014) offers an information-theoretic analysis of knowledge, indebted to Dretske (Reference Dretske1981), according to which:

Information-Theoretic Analysis of Knowledge: A knows p iff both:

(1) A is in a state that carries the information that p, and

(2) A’s being in this state causes or constitutes S’s believing that p.

According to Greco, the notion of “carrying information” itself can be cashed out in terms of normality:

Normality Analysis of “Carrying Information”: A is in a state s that carries the information that p iff both:

(1) Whenever conditions are normal, A is in s only if p, and

(2) Conditions are normal.

Another normality-based account of knowledge comes from Beddor and Pavese (Reference Beddor and Pavese2020), who defend a variant of a safety condition on knowledge (Section 1). Rather than defining safety in terms of nearby worlds, they define it in terms of normal worlds. Specifically:

Normality-Based Safety: Suppose an agent A believes p at w, using process X. A’s belief that p amounts to knowledge iff p is true in all worlds w’ where both:

(1) S believes p using X, and

(2) Conditions are at least as normal for the operation of X as those which obtain at w.Footnote 28

Unlike Greco’s version of Dretske’s analysis, this theory allows that knowledge is possible even when conditions are abnormal. What’s required is that your belief-forming process must get things right not just in your abnormal circumstances, but also in circumstances that are more normal than yours.

A full discussion of these views is outside the scope of this Element. The important point is that Normal Worlds Reliabilism is not without precedent or parallel. It bears an intriguing resemblance to various recent theories of knowledge.

Let’s now switch gears and consider challenges to the idea that reliability is sufficient for justification.

3.2 Clairvoyants & Rogue Neurosurgeons

3.2.1 The Challenge

According to Simple Process Reliabilism, reliability is sufficient for justification: If someone’s belief is the result of a reliable process, then their belief is justified. The person does not need to know, or justifiably believe, or even have reason to believe that their belief was reliably formed.

This feature of reliabilism gives rise to a family of counterexamples. These counterexamples share the following structure: An agent forms a belief through a process that happens to be reliable, but the agent does not have any good reason to think they are using a reliable process. Consider:

Norman (Bonjour Reference BonJour1980) Norman happens to be a clairvoyant. His clairvoyance is highly reliable: whenever he gets a compelling clairvoyant hunch about some matter, his hunch is invariably correct. However, Norman has never bothered to check the reliability of his clairvoyance; indeed, he has no evidence for or against the presence of this clairvoyant faculty. One day while eating breakfast Norman gets a clairvoyant hunch that the U.S. president is in New York. Based on his hunch, Norman comes to believe the president is in New York.

By stipulation, Norman’s belief is the result of a reliable process. So, according to Simple Process Reliabilism, his belief is justified. But, according to BonJour, this is wrong: Norman’s belief is not justified.

In support of this claim, BonJour considers two possibilities. The first is that Norman believes he has clairvoyance, and this belief is part of his basis for thinking the president is in NY. But, BonJour asks, “is it not obviously irrational, from an epistemic standpoint, for Norman to hold such a belief when he has no reasons at all for thinking that it is true or even for thinking that such a power is possible?” (Reference BonJour1980: 62). If the answer is yes – as BonJour implies – then, BonJour contends, Norman’s belief about the president’s whereabouts is also irrational.

The second possibility is that Norman does not believe he has clairvoyance. In that case, BonJour claims, Norman’s beliefs are deeply puzzling:

From his standpoint, there is apparently no way in which he could know the President’s whereabouts. Why then does he continue to maintain the belief that the President is in New York City? Isn’t the mere fact that there is no way, as far as he knows or believes, for him to have obtained this information a sufficient reason for classifying this belief as an unfounded hunch and ceasing to accept it? And if Norman does not do this, isn’t he thereby being epistemically irrational and irresponsible?

Consequently, BonJour contends, Norman’s belief about the president’s whereabouts is “epistemically irrational and irresponsible, and thereby unjustified, whether or not he believes himself to have clairvoyant power” (Reference BonJour1980: 63).

Structurally similar examples abound:

Truetemp. (adapted from Lehrer Reference Lehrer1990) Truetemp goes to the doctor for what he thinks will be routine brain surgery. Truetemp’s doctor has other ideas; unbeknownst to Truetemp, she is an inventor and experimental neurosurgeon with little regard for informed consent or IRBs. While Truetemp is under anaesthesia, his doctor implants a device of her own devising, a “Tempucomp.” One part of the Tempucomp is an extremely accurate thermometer affixed to Truetemp’s scalp. Another part of the Tempucomp is a computational device in Truetemp’s brain, capable of generating thoughts. The thermometer reliably transmits its readings of the ambient temperature to the computational component, which generates the corresponding thoughts in Truetemp’s brain. The doctor does not tell Truetemp about any of this; when he wakes up, he has no idea that he has such a device implanted in his brain. After leaving the hospital, Truetemp finds himself struck by the thought that is exactly 74.5 degrees outside. He consequently believes that it is exactly 74.5 degrees outside, but never bothers to check this against any other source of information.

Truetemp’s belief is produced by a reliable process (the Tempucomp). So if reliability were sufficient for justification, his belief would be justified. But, Lehrer claims, this is intuitively incorrect. To see the pull of this intuition, note that his belief about the temperature is extremely specific: exactly 74.5 degrees. Most ordinary humans cannot tell the temperature with such precision. Since TrueTemp has no reason to think he has had a Tempucomp in his head, he has no reason to think that he is different from ordinary humans in this respect.

3.2.2 Attributor Reliabilism and Normal Worlds Reliabilism, Reprised

Can the problem be avoided? One natural thought is that we could redeploy some of the maneuvers developed in response to the New Evil Demon Problem. Take Attributor Reliabilism. Applied to Norman: Attributor reliabilists might argue that clairvoyance is not reliable in the actual world. In our world, people who form beliefs about the locations of distant objects on the basis of hunches tend to be mistaken about them. So we can correctly judge:

(4) Norman’s belief that the president in New York is unjustified.

This attribution is true relative to our world of evaluation (@).

It is, however, less straightforward to apply this maneuver to Truetemp. After all, the process responsible for Truetemp’s belief about the temperature is something like: forming beliefs about the temperature based on a Tempucomp – call this process “T.” Since T has never been instantiated in the actual world, it is unclear how to assess it for reliability.

Some might think there is an easy fix: just expand our domain of evaluation. Specifically, we could revise Attributor Reliabilism to say that an ascription of the form, “A’s belief is justified” is true at a world of evaluation w iff A’s belief was produced by a process that tends to produce true beliefs at the nearest worlds to w where that process is instantiated. Applied here, the idea would be that the ascription:

(5) Truetemp’s belief about the temperature is justified.

is true at our world (@) iff T tends to produce true rather than false beliefs at the nearest worlds to @ where T is instantiated. But at the nearest worlds to @ where T is instantiated, it does tend to produce true beliefs. (After all, we stipulated that the Tempucomp functions extremely well, never yielding errors about the temperature.) So this approach would still predict Truetemp’s belief is justified.

Similar points hold for Normal Worlds Reliabilism. Consider first Goldman’s version of the view, where the normal worlds are those worlds consistent with many of our general beliefs about the world. As Goldman notes, there is a widespread belief that clairvoyance is not reliable, so at all normal worlds (in Goldman’s sense) this process will be unreliable. In other worlds, Norman ain’t normal! However, it is less clear that this helps with Truetemp, since ordinary people don’t have beliefs about the reliability of Tempucomps.

What if we go the functionalist route, identifying the normal worlds for a process X with those worlds where conditions are conducive to the fulfillment of X’s function? Any such account should allow for functions that are derived from intentions. For example, the reason why the function of the gas gauge in my car is to indicate the fuel level is that it was designed to indicate the fuel level. Similarly, the Tempucomp was designed to accurately record the ambient temperature and to transmit these recordings to a person’s brain. So the worlds where the Tempucomp fulfills this function will be worlds where the Tempucomp is reliable. Once again, we have failed to find an explanation that predicts that Temp’s belief-forming process is unreliable.

3.2.3 Primal Systems

Another response to these counterexamples has been developed by Lyons (Reference 77Lyons2009). A distinctive feature of BonJour and Lehrer’s examples is that our characters’ belief-forming processes have a somewhat unusual etiology. This is particularly clear in the case of Truetemp, whose heat-detecting abilities result from a newfangled technology surreptitiously implanted into his brain. Things are less clear-cut in the case of Norman; BonJour does not tell us where Norman’s clairvoyance comes from. But, according to Lyons, the example suggests that Norman’s clairvoyance stems from some recent development, such as “a recent encounter with radioactive waste” or a “neurosurgical prank” (Reference 77Lyons2009: 118–119).

This leads Lyons to suggest both a diagnosis of the source of the problem and a proposed fix. The diagnosis: The etiology of Norman and Truetemp’s beliefs deprives their beliefs of justification. Specifically, their beliefs are not justified because they are not produced by what Lyons call a “primal system,” where a primal system is roughly akin to a module (in the sense of Fodor Reference Fodor1983). An important feature of primal systems, as Lyons understands them, is that they involve some combination of learning and innate constraints. This characteristic is not shared by either Truetemp’s Tempucomp or Norman’s clairvoyance. For example, the surgically implanted Tempucomp is neither innate nor the result of learning.

This diagnosis also suggests a solution. According to Lyons, in order for a non-inferential belief to be justified, it’s not enough for it to be reliably formed. It must also be the result of a primal system.

Lyons supports this solution by offering variants of Norman, for example:

Nyrmoon (adapted, with slight modifications, from Lyons Reference 77Lyons2009). Nyrmoon belongs to an extraterrestrial species that have evolved a form of highly reliable clairvoyance. For them, clairvoyance functions as a normal perceptual faculty. (It works by picking up highly attenuated energy signals from distant events, which members of their species experience as strong “hunches.”) However, Nyrmoon is so unreflective that he has never bothered to form any beliefs about the reliability of his clairvoyance. One day, while eating his breakfast he gets a clairvoyant hunch that his president is currently in Nu Yark (a large city on their planet). Based on this hunch, he comes to believe his president is currently in NY Yark.Footnote 29

Lyons claims that Nyrmoon’s belief is intuitively justified, unlike Norman’s. What explains this difference? The answer, says Lyons, lies in the etiology of their belief-forming processes. Nyrmoon’s belief is the result of a primal system; it is part of his innate cognitive endowment.

While this is an ingenious solution, two points are worth noting. First, the primal systems view is not the only possible explanation for why Nyrmoon’s belief is justified. Another relevant feature of the case is that clairvoyance is an evolved trait in Nyrmoon’s species, and has acquired the function of tracking distant events through this evolutionary process. Thus, the functionalist version of Normal Worlds Reliabilism will agree that Nyrmoon’s belief is justified.Footnote 30

Second, we might question this shared assumption that the etiology of a belief-forming process plays such a crucial role in determining justificatory status. Consider the following variant:

Noramoon. Nyrmoon has a cousin, Noramoon, who was born with a birth defect depriving her of the clairvoyant abilities of her conspecifics. But an hour after her birth she was exposed to some radioactive waste. By a stroke of luck (the sort of luck that is the bread and butter of superhero origin stories), this causes her to develop a clairvoyant ability that is even more reliable than that of her fellow clairvoyants. She likewise forms the belief that the president is in NuYark.

Lyons’ proposal predicts that whereas Nyrmoon’s belief is justified, Noramoon’s belief is not. Is this prediction correct? Different readers may have different intuitions here, and it is not my goal to try to legislate which intuitions are correct. But, speaking for myself, I am inclined to think that Noramoon’s belief is just as justified as Nyrmoon’s.

Now, there is an interesting question as to why Noramoon’s belief is justified (assuming it is), whereas Norman’s belief is not. One possible answer is that Noramoon belongs to a species whose members have evolved clairvoyant powers, unlike Norman. If so, then perhaps the etiology of the belief-forming process is still relevant to justification, just in a more indirect way: Perhaps we need to look at the etiology of sufficiently similar belief-forming processes characteristic of that agent’s species. Another possible answer is to appeal to subtle differences in Noramoon’s background information and Norman’s background information. I explore this alternative answer in Section 3.2.5.

3.2.4 Agent Reliabilism

Another variant of reliabilism has been defended by John Greco under the banner of “agent reliabilism” (Reference Greco1999, Reference Greco2000, Reference Greco2003). Agent reliabilism claims that in order for a belief to be justified, it’s not enough for it to be produced by a reliable belief-forming process. Rather, the belief must result “from stable and reliable dispositions that make up [the agent’s] cognitive character.” (J. Greco Reference Greco1999: 287–288) And this in turn requires that the dispositions are both stable and “well integrated with [the agent’s] other cognitive dispositions.” (J. Greco Reference Greco2003: 74)

Could agent reliabilism solve our problems? It might seem the answer is yes. Agent reliabilists might argue that Norman’s clairvoyance is not well integrated with his other cognitive dispositions, in which case his clairvoyant belief would not be justified. (Likewise with Truetemp and his Tempucomp.)

But how should we understand this notion of cognitive integration? Greco offers some remarks on the matter: “one aspect of cognitive integration concerns the range of outputs – if the products of a disposition are few and far between, and if they have little relation to other beliefs in the system, then the disposition is less well integrated on that account.” (Reference Greco2003: 74) But, as Greco acknowledges, we can imagine a version of the Norman scenario where this condition is met. Perhaps every day Norman finds himself forming a belief about the distant location of some object or person. And suppose all of the resultant beliefs are logically consistent with the beliefs he forms through his other senses. So they are coherent with these other beliefs, in at least this minimal sense.Footnote 31,Footnote 32

In other passages, Greco suggests that in order for a disposition to be well integrated with an agent’s cognitive character, it must be responsive to “dispositions governing counterevidence that disallow his clairvoyant belief.” (Reference Greco2003: 475) The suggestion here seems to be that Norman has counterevidence which defeats his belief. This is an intriguing suggestion, and I think it is onto something important. But it deserves further scrutiny. Does Norman have defeating counterevidence? Let’s take a closer look …

3.2.5 Appealing to Defeat

The idea that Norman has defeating counterevidence has been defended independently, by philosophers who do not subscribe to agent reliabilism. Here, for example, is Goldman (Reference Goldman1986):

BonJour describes this case as one in which Norman possesses no evidence or reasons of any kind for or against the general possibility of clairvoyance, or for or against the thesis that he possesses it. But it is hard to envisage this description holding. Norman ought to reason along the following lines: ‘If I had a clairvoyant power, I would surely find some evidence for this. I would find myself believing things in otherwise inexplicable ways, and when these things were checked by other reliable processes, they would usually check out positively. Since I lack any such signs, I apparently do not possess reliable clairvoyant processes.’

Call this the “defeater diagnosis.” There is, I think, something very attractive about this proposal. Norman’s absence of any evidence in favor of his clairvoyance is itself evidence that he lacks clairvoyance. Moreover, Norman presumably lacks evidence that anyone else has reliable clairvoyant powers. (If he’s like us, he is even aware of self-proclaimed clairvoyants who turned out to be cranks.) Here too, this absence of evidence is itself evidence – specifically, evidence that people do not possess clairvoyant abilities. Arguably, these features of his background information are partially responsible for the intuition that Norman’s belief is not justified.

A similar diagnosis extends to Truetemp: He has all sorts of indirect evidence that he does not have a Tempucomp in his head (what are the odds?), and that consequently he is an ordinary human, who is incapable of detecting the temperature with such fine-grained precision. And this evidence seems like it is part of what diminishes the justificatory status of his belief.

One way of testing the defeater diagnosis is to consider a variant of Norman where he has not yet acquired any defeating evidence. I present to you:

Baby Norman. Baby Norman has highly reliable clairvoyance. Being a baby, has never had the opportunity to check the reliability of his clairvoyance, or to amass any track record evidence of its reliability. As he lies in his crib, he forms all sorts of beliefs using his senses. He uses his vision to form the belief that his mother is standing over his crib. He uses his hearing to form the belief that the dog is barking. And he uses his clairvoyance to form the belief that his father is in the kitchen.

In this version of the case, the line of reasoning that Goldman suggests Norman should engage in – If I had a clairvoyant power, I would surely have found some evidence for this by now. Since I have found no evidence for this, this is evidence that I lack a clairvoyant power – is inapplicable. Is baby Norman’s clairvoyant belief that his father is in the kitchen justified?

Speaking for myself, I am inclined to think the answer is yes. At the very least, it seems that there is an important justificatory difference between adult Norman’s belief and his infant counterpart’s. To draw out this intuition, recall BonJour’s contention that it would be irrational for (adult) Norman to think the president is in NY, since it is irrational for him to think he has clairvoyance. By contrast, it does not seem that it is irrational for baby Norman to hold his clairvoyant belief concerning his father’s whereabouts. For those who share the judgment that there is an important justificatory difference between our two Normans, this suggests that the defeater diagnosis is on the right track.

Let me briefly consider two ways of pushing back against the defeater diagnosis. First, even those who agree that there is a justificatory difference between baby Norman and adult Norman may still have the residual intuition that there is something epistemically amiss about baby Norman’s clairvoyant belief. Specifically, some might think that his clairvoyant belief is less justified than, say, his visual or auditory beliefs. (See Graham Reference Graham2017.) I confess that I do not share this residual intuition myself. But my goal here is not to dictate what people’s intuitions should be. Rather, I will just note that there is nothing to prevent us from combining the defeater diagnosis with one of the other responses to the clairvoyance objection discussed in this section, such as Normal Worlds Reliabilism or the primal systems view. According to this “combination response,” baby Norman’s clairvoyant belief is less than fully justified, because of its strange etiology. But adult Norman’s clairvoyant belief is in even worse epistemic shape, since it is held in the face of defeating evidence.