Introduction

Human beings learn to reason by analogy very early in their lives. Research in cognitive science shows that children as young as 1, 2 or 3 years old already use analogical reasoning;Footnote 1 even young infants are capable of certain forms of relational thinking. Analogies help infants and children understand the world,Footnote 2 so it is therefore unsurprising that analogical reasoning is also very common among adults, both in everyday lifeFootnote 3 and in scientific contexts. Cognitive scientists have demonstrated that “scientific breakthroughs often depend on the right analogy”.Footnote 4 More broadly, it is now “accepted that analogical reasoning is a core component of [human] intelligence”.Footnote 5

Among all human beings, lawyers certainly stand out in this regard: they are known to regularly use analogies, and analogies are central to legal reasoning.Footnote 6 Thus, as a legal discipline, international humanitarian law (IHL) is expected to feature a reasonable number of analogies. Yet, a preliminary examination of analogical reasoning in the field suggests that IHL analogies significantly surpass this expectation, strongly reinforcing the hypothesis that analogies seem not merely common but massively used in IHL. Indeed, analogies permeate the entire domain of IHL. A reader who starts to pay attention to them will quickly notice their voluminous occurrence in IHL historical documents, preparatory works, academic literature and case law. IHL scholars often rely on or consider analogical argumentsFootnote 7 – this author included.Footnote 8 This hypothesis of a massive use of analogies in IHL is accompanied by another hypothesis: that analogical reasoning is key to understanding the normative content and structural development of the field.

However, as an independent subject of inquiry, analogies are largely overlooked in IHL. Indeed, despite some significant scholarly contributions over the last century,Footnote 9 such as in legal theory and general international law, analogies remain under-explored overall in legal scholarship.Footnote 10 There is a noticeable gap between the common use of analogies in law and the relatively limited academic attention devoted to them. Scott Brewer emphasized years ago that “despite … its special prominence in legal reasoning …, [reasoning by analogy] remains the least well understood and explicated form of reasoning”.Footnote 11 International law does not escape this observation, except perhaps in a few niche areas such as international investment law;Footnote 12 in contrast to that body of law, IHL exemplifies the gap between practice and research on analogies.

In IHL, very few authors have studied the use of analogies,Footnote 13 and when they have, their analyses have often been limited in scope or depth. Examples of narrowly scoped analyses can be found in the work of Marco Sassòli and Sandesh Sivakumaran. Both restrict their investigation on analogical reasoning in IHL to a single area: the development of the law governing non-international armed conflict (NIAC) by analogy with the law applicable to international armed conflict (IAC).Footnote 14 Although it bears a compelling title, Kevin Jon Heller’s book chapter on “The Use and Abuse of Analogy in IHL” provides an example of an analysis that limits itself in depth – as well as in scope – by adopting a narrowly framed approach. Specifically, Heller considers US analogies in IHL through a single research question: the legal foundation of US authority to analogize NIACs with IACs.Footnote 15

Given the absence of in-depth and widely scoped research on analogical reasoning in IHL, discussing analogies in this field remains a challenge. IHL experts may recognize an analogy when they encounter one – or even suggest analogical reasoning themselves – but they struggle, or at least refrain from, explaining what it is, how it functions, what its purposes or roles are and why it is persuasive.Footnote 16 This article seeks to open the debate on the issue rather than comprehensively address all the relevant questions regarding analogies in IHL.

Consequently, this article pursues two objectives. First, it conducts an empirical investigation into the prevalence and significance of analogies in IHL. Based on the collected data, the article proposes a taxonomy of IHL analogies. Second, building on the hypothesis that analogical reasoning plays a key role in the normative content and structural development of IHL, the article analyzes these analogies from an axiological perspective, identifying the underlying values and benefits that they convey. Before proceeding, however, some preliminary remarks on the scope and boundaries of the research are necessary.

Research boundaries

In short, this article addresses the role(s) of legal analogies in the historical development of IHL, from 1864 to 2001. Each term in the formulation of this research topic warrants clarification and commentary. The following paragraphs will define each term and thus clearly delineate the scope of the article – what it will accomplish and what it will not. Each term reflects deliberate decisions made by the author.

Notion of analogies

Analogy is a polysemous concept.Footnote 17 In his recent doctoral dissertation, Balthazar Durand-Jamis identifies eleven distinct definitions of analogy within legal theory;Footnote 18 it is therefore necessary for the present author to clarify how the term is understood in the context of this article. Analogy has here both a broad and a narrow understanding.

First, in its broad understanding, analogy is largely defined as encompassing two variants. The dataset used to support the proposed taxonomy and analysis includes IHL analogies that pertain either to a similarity of terms or to a similarity of relations. Analogical reasoning may refer to a similarity of terms (similitude de termes) between a known situation of warfare and a novel one, thereby enabling the extension of the existing legal framework from the former to the latter. In this article, analogy also involves a similarity of relations (similitude de relations), whereby the legal relationship between a known warfare situation and its corresponding legal regime serves to clarify the legal relationship between a novel warfare situation and its own corresponding legal regime (as it is or ought to be).Footnote 19 Furthermore, the dataset accounts for all subcategories of analogy, such as a contrario or a fortiori analogies. This inclusive approach allows for a more comprehensive overview of the phenomenon of IHL analogies. A caveat is necessary, however: although this essay focuses on analogies, different forms of reasoning are often intertwined in legal argumentation, making it complex to isolate analogical reasoning from other forms.Footnote 20

Second, in its narrow understanding, the term “analogy” as used in this article excludes other related concepts or methods of reasoning which are often associated with analogical thinking. These concepts or methods refer to a very specific and distinctive form of analogical reasoning, such as the concept of legal fiction, which also exists in IHL. A fiction disregards differences and emphasizes similarities between two situations in order to construct legal identity where there is none factually.Footnote 21 The application of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (AP I) to “peoples … fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination” is a notable example of legal fiction.Footnote 22 There are important factual differences between national liberation wars and IACs, such as the nature of the belligerents. While IACs traditionally oppose two States, national liberation movements are non-State actors. However, lawmakers eventually began to ignore these differences and to consider the two as identical from a legal perspective in AP I. In the interest of analytical clarity, certain specific concepts – like legal fictions – are thus not included in the scope of this article.

In addition to defining analogy, it is useful to outline the basic steps of analogical reasoning, as the article will refer to technical terminology. Indeed, analogies are often discussed using specialized vocabulary. With a strong inspiration from cognitive science (especially psychological research), it is now widely accepted that analogical reasoning involves three steps:Footnote 23

1. Retrieval: the analogizer must select or retrieve from his/her memory a relevant source – i.e., a known situation already governed by law – to which the target can be compared. The target is the unknown situation for which a legal solution is sought.

2. Mapping: the analogizer must map the source and the target – i.e., determine the connections that are the similarities and differences between the two. Two situations may be similar and different from many viewpoints.Footnote 24 There are surface-level (dis)similarities (often identified during retrieval) and deeper relational similarities (typically analyzed during mapping).Footnote 25 What matters is that the similarities are relevant for legal purposes.Footnote 26 Analogies depend more on the quality than on the quantity of the (dis)similarities.Footnote 27

3. Transfer (or extension): when the relevant similarities outweigh the critical differences, the analogizer may transfer or extend the legal solution – or certain structural elements – from the source to the target.

Notion of legal analogies

This article exclusively presents and scrutinizes data on legal analogies in IHL – that is, analogies which have contributed to the normative development of this field.Footnote 28 The analogies under examination have resulted in the creation of new IHL rules which have been incorporated into formal sources of international law and are now binding on parties to armed conflict; in other words, they have triggered legal evolution within the field. By contrast, this article does not investigate analogies that did not help develop IHL norms.

In this respect, the present article does not explore the many descriptive or factual analogies found in heritage documents and preparatory works of classical IHL conventions. These analogies serve an explanatory function: they help the reader to grasp the reality on the ground and provide a better understanding of certain situations. Their function is more metaphorical in nature. They create vivid and concrete associations in the minds of people, guiding them toward a particular understanding of the unknown situation.Footnote 29 For example, during the fourth session of the International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (International Conference), held in Berlin in April 1869, attorney Buchner analogized wartime rescuers with firemen, as both were expected to perform auxiliary tasks in the absence of emergencies requiring their specialized intervention.Footnote 30 In their seminal works, Henry Dunant and Gustave Moynier compared wars between nations with, respectively, chivalric duels and criminal legal fighting.Footnote 31 While Dunant considered that it was necessary to mitigate bloodshed in duels both between nations and individuals, Moynier linked warfare and legal proceedings through shared elements such as material strength, skills and procedural fairness. During the 1974–77 Diplomatic Conference, which led to the adoption of the two Additional Protocols, Sweden proposed an analogy between the risks faced by civilians during wartime hostilities and those encountered in peacetime motor traffic.Footnote 32 While certainly evocative, these descriptive analogies did not have any normative purpose and did not contribute to the development of the IHL framework.

Likewise, this article does not examine historical analogies that occasionally appear in IHL discourse. These analogies draw comparisons between past and contemporary armed conflicts.Footnote 33 For instance, during the 19th plenary meeting of the 1949 Diplomatic Conference, which resulted in the adoption of the four Geneva Conventions, the Venezuelan delegate compared the relatively new phenomenon of civil wars to two earlier forms of conflict: the conflict between patricians and plebeians in Antiquity, and the class conflict between the workers and capitalists during the Industrial Revolution.Footnote 34 Again, while such historical analogies may have offered valuable insights into the factual understanding of warfare, they did not lead to normative developments.

Focus on the role(s) of analogies

This article deliberately accepts a premise without challenging it. In other words, it starts from a straightforward observation: that analogies are used in IHL. Whether such use is acceptable within IHL does not change the reality that analogies are present in this branch of international law. Accordingly, this article does not examine the criteria for validity or admissibility of analogical reasoning in IHL. In particular, it does not engage with the contested issue of lacunae in the international legal order.Footnote 35 While this is a relevant and worthwhile topic of inquiry, this author has decided to set it aside for the purposes of this article.

Similarly, this article does not – and cannot – offer a complete theory of analogies in IHL. Several dimensions fall outside the scope of this analysis, including the nature or potential distinctive features of IHL analogies. The decision to exclude these dimensions stems from three considerations. The first and most obvious reason is that any thorough theoretical analysis of IHL analogies presupposes a broad, yet detailed, overview of their practical use in the field. Establishing such an empirical foundation is a critical preliminary step. Second, exploring the role(s) of analogies in IHL development is likely to be of greater interest to most IHL lawyers than engaging in abstract debate about, for example, the deductive or inductive nature of analogical reasoning in the field. Third and finally, this author is of the view that the mental process of analogizing in IHL does not fundamentally differ from the cognitive process of analogizing in general international lawFootnote 36 – however, analogies may assume a particularly notable role in IHL. Thus, this article focuses on identifying IHL analogies and on examining their role(s) in the development of this legal field.

Focus on the development of IHL

The objective of this article is to examine how analogical reasoning has specifically contributed to the development of IHL, not international law more broadly. Two formal sources of international law – customary norms and general principles of lawFootnote 37 – consistently rely on analogical reasoning, regardless of the legal field. The mental process behind the identification of customary norms and general principles of law inherently involves some sort of analogical reasoning. Customary norms rely on a comparative exercise of analogous State practices,Footnote 38 while general principles of law usually consist of domestic law analogies, as the analogical source is to be found in domestic law. The analogizer induces a principle from various domestic legal systems and then applies it deductively to the target situation under international law.Footnote 39

However, through customary norms and general principles of law, analogical reasoning contributes not to the “content” but rather to the “form” of IHL norms – that is, their customary or principled nature. For instance, customary IHL prohibits attacks against civilians.Footnote 40 Analogical reasoning helped determine the customary nature of this rule (its form), but not the rule itself (its content – i.e., the idea that any attack against civilians is prohibited). To the best of this author’s knowledge, no clear analogy led to the idea that one cannot attack civilians. Consequently, analyzing all IHL customary rules and general principles of law does not, in itself, say much about the specific role of analogies in shaping the substantive content of IHL. This does not imply that no IHL customary norm or principle is relevant to the present inquiry; relevance arises when the content of the rule or principle itself originates from, or gives rise to, analogical reasoning.

Furthermore, analogies do not independently generate normative content. They are not formal sources of international law (nor, a fortiori, of IHL). Their contribution to IHL development depends on their incorporation into a recognized formal source of IHL, most commonly a treaty, a customary rule or a general principle of law.Footnote 41 These formal sources may confer normative status upon analogies by embedding either the analogical reasoning itself or its outcome. As An Hertogen has concluded, “analogy does not have more force than international law gives it”.Footnote 42

Temporal scope of the research: 1864 to 2001

This article examines the role of analogies in the historical development of IHL, focusing on the contribution of analogical reasoning to well-established IHL norms. By contrast, it does not present data on the use of analogies in the current and future development of IHL. Numerous ongoing debates suggest potential evolutions in IHL based on analogical arguments. These debates span a wide range of topics and touch upon changes in armed conflicts such as the actors involved, the domains of warfare and the means and methods of combat. Among the most prominent issues are detention in NIACs, warfare in cyberspace and outer space, and the use of autonomous weapons systems.Footnote 43 At the moment, it remains uncertain whether analogical reasoning will play a decisive role in shaping IHL norms in these areas. These norms are still under discussion and have not yet (fully) crystallized. While analogical trends in contemporary IHL discourse are also worth exploring, it is essential to first understand how analogical reasoning has contributed to the development of the existing legal framework.

The temporal scope of this article’s research extends from 1864 to 2001. The year 1864 is widely recognized as the birth of modern IHL, marked by the adoption of the First Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field.Footnote 44 Moreover, accessing IHL historical documents prior to this date is significantly more difficult,Footnote 45 which justifies the starting point of the dataset. As for the end date, the early twenty-first century represents a turning point for IHL, particularly in response to the global fight against terrorist armed groups (when constituting organized armed groups under IHL). Since 2001, new challenges have emerged – both related and unrelated to counterterrorism – that have profoundly altered the realities of warfare and have placed considerable pressure on the legal system. These evolving circumstances have prompted a period of reflection and transformation within the discipline. Nevertheless, as previously noted, this process is still ongoing, rendering any analysis of analogical reasoning in relation to these challenges necessarily prospective. Accordingly, this essay adopts a retrospective perspective, focusing on analogies that have already contributed to the development of IHL.

To clarify, the selection of 2001 as the end date for the dataset does not imply that no significant developments in IHL have occurred thereafter. On the one hand, several treaty norms were indeed adopted post-2001 in specific areas of IHL – however, a preliminary review did not lead this author to anticipate a central role for analogical reasoning in the legal evolution of these areas. While analogical reasoning appears to have been pivotal in the historical development of IHL, it may not have played a similarly prominent role across all areas. For instance, Additional Protocol III was adopted in 2005,Footnote 46 and the Convention on Cluster Munitions in 2008.Footnote 47 A cursory examination of these two treaties, including a keyword-based search (see Annex), did not suggest that the norms they introduced serve as very compelling examples of analogy-driven legal development within IHL.

On the other hand, the choice of 2001 as a cut-off date does not preclude the consideration of post-2001 IHL documents, insofar as they relate to and elucidate norms established prior to that year. For example, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) published its study Customary International Humanitarian Law (ICRC Customary Law Study) in 2005,Footnote 48 and released updated Commentaries on Geneva Conventions I, II, III, and IV in 2016, 2017, 2020 and 2025, respectively.Footnote 49 The ICRC Customary Law Study codified customary rules that, for the most part, had likely crystallized before 2001. The updated Commentaries address norms adopted in 1949; in this context, both historical insights into the adoption of these norms and post-1949 developments that were already widely accepted by 2001 are taken into account. Conversely, more recent, innovative and still-contested interpretations are excluded from consideration.

Taxonomy

With these research boundaries set, this section classifies the data collected on IHL analogies between 1864 and 2001 into three categories. It provides a selection of relevant examples and explanatory commentaries for each category. It should be noted that this section does not offer an exhaustive catalogue of all analogies in IHL – the number of occurrences is too great to be comprehensively addressed within the scope of this article. Instead, it highlights the most compelling and illustrative examples, thereby privileging a qualitative over a quantitative approach.Footnote 50

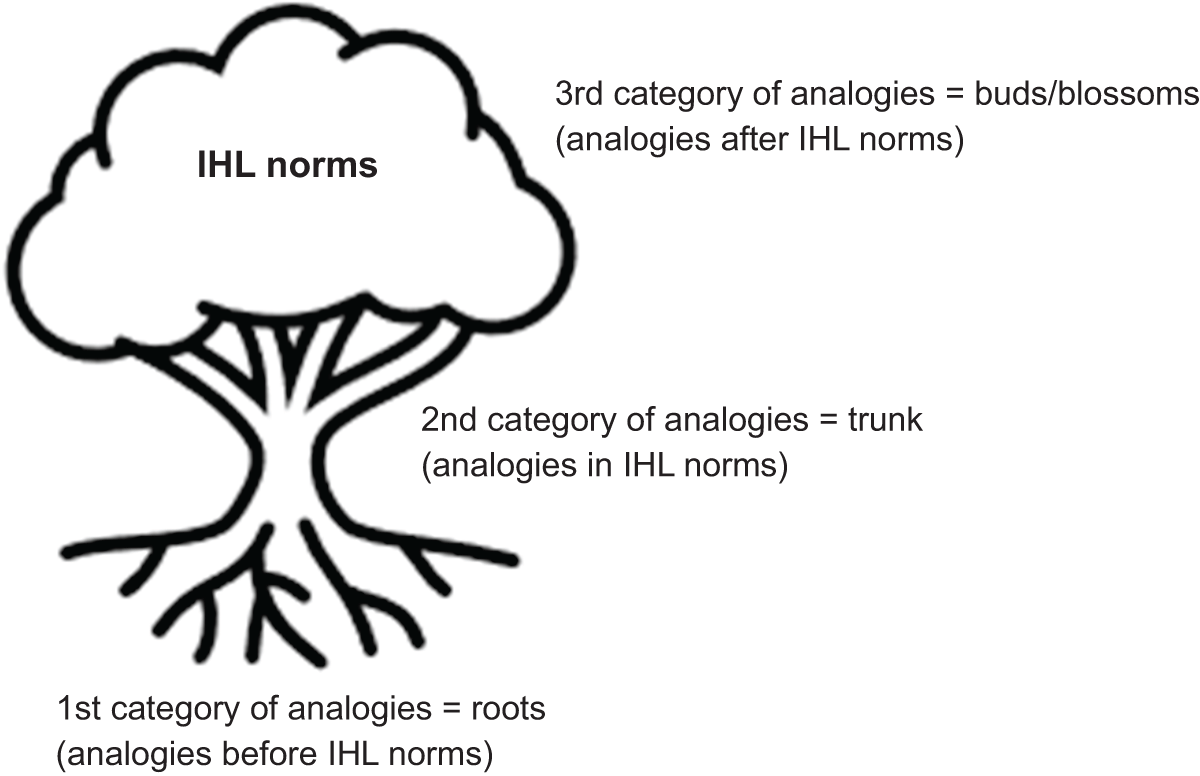

The classification is based on two related criteria: the chronological relationship between analogies and the corresponding IHL norms, and the identity of the actors involved in the analogizing process, namely lawmakers, norm-appliers and norm-interpreters (notably, international judges). For descriptive purposes (and acknowledging that this author herself engages in analogical reasoning), a tree metaphor proves useful (see Figure 1). Some analogies precede the adoption of a norm and may be likened to the roots of an adopted IHL norm; others are embedded in the very trunk of the adopted norm, while still others emerge after the norm’s adoption, branching out like buds or blossoms.

Figure 1. Categories of IHL analogies.

Analogies before IHL norms

Analogies were often used before the adoption of IHL norms; on a time scale of such cases, analogies came first, and IHL norms second. Many of the most important milestones in the legal evolution of IHL originated in analogical reasoning, and numerous IHL norms are thus the product or result of analogical thinking. Indeed, States – acting as lawmakers – frequently reasoned by analogy to shape the content of new IHL norms.Footnote 51 In this first category of analogies, those applied before IHL norms, they preferred to employ this reasoning themselves rather than to leave it to any norm-applier or norm-interpreter. Here IHL lawmakers are the analogizers, and analogies function as a legislative technique.Footnote 52 Because IHL lawmakers typically aim to establish not merely isolated rules but comprehensive legal regimes (States would not gather to multilaterally discuss the adoption of a single IHL norm), they often use multiple analogies around the same theme. Although lawmakers seldom make their analogical reasoning explicit in the final legal texts, traces of such reasoning are often discernible in the drafting of these norms, particularly through cross-references or the use of similar language drawn from existing norms.

To illustrate this category of analogies, the regulation processes of four landmark legal regimes in IHL will be briefly examined through the analogical lens: the regulation process of maritime warfare, the regulation process of air warfare, the regulation process of civilian detention and the regulation process of NIACs. Each of the four analyses below adopts a chronological perspective and presents analogical occurrences following the moment of their appearance in time.

From land warfare to maritime warfare

Geneva Conventions I and II (GC I and GC II) both address the protection of wounded and sick (and, in the case of GC II, shipwrecked) members of armed forces. GC I pertains to land warfare,Footnote 53 while GC II governs maritime or naval warfare.Footnote 54 Even though these two conventions regulate distinct domains of warfare, the parallels between them are striking, both in the structure of their chapters and the phrasing of their provisions. Historical evidence suggests that these similarities are not coincidental but rather the result of a deliberate analogical reasoning between warfare on land and warfare at sea, at least in relation to the protection of people in wartime (Geneva law).Footnote 55 Land warfare received the earliest attention from lawmakers, beginning in 1864 with the previously mentioned Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field.Footnote 56 Thereafter, land warfare served as the analogical source to which maritime warfare – the analogical target – was compared. The legal framework developed for land warfare was used as a model for regulating maritime warfare, based on the assumption that the two war situations were sufficiently similar. However, where crucial differences were identified, the legal regime for land warfare was adapted to account for the specificities of maritime warfare.

The heritage collection on the First Geneva Convention is very illuminating in this regard. In his 1870 Etude sur la Convention de Genève, Gustave Moynier noted that the idea of analogizing maritime warfare with land warfare had already emerged in 1864.Footnote 57 The draft convention submitted by the International Committee for Relief to the Wounded (ICRW)Footnote 58 for the 1864 Diplomatic Conference included a provision on the issue in its Article 11, which stated: “Des stipulations analogues à celles qui précèdent, relatives aux guerres maritimes, pourront faire l’objet d’une Convention ultérieure entre les Puissances intéressées.”Footnote 59 A few years later, in preparation for the 1868 Diplomatic Conference to revise the First Geneva Convention, the ICRW proposed, as a point of discussion, the extension of the existing land warfare framework to maritime warfare.Footnote 60 The States attending the Conference approved ten additional draft provisions addressing this issue.Footnote 61 Commenting on these draft articles, Moynier wrote:

Les développements dans lesquels nous sommes entré, au sujet des articles de la Convention primitive, nous dispenseront de longues explications sur les articles additionnels qu’il nous reste à passer en revue, car il y a entre eux de grandes analogies. Ce sont les mêmes principes qui les ont dictés les uns et les autres, et ils ne diffèrent guère qu’en ce qui tient aux conditions spéciales de la guerre sur terre ou sur mer. Footnote 62

Carl Lueder, in his 1876 monograph, also examined these ten draft articles. He concurred with Moynier on the appropriateness of analogical reasoning between land and maritime warfare, stating:

Le principe directeur de ces dispositions doit être celui-ci: extension à la guerre maritime des articles valables pour la guerre sur terre; ou plutôt: mêmes articles pour la guerre sur terre et pour la guerre maritime; mêmes principes humanitaires pour tous les genres de guerre, autant du moins que les conditions spéciales de la marine ne réclament pas des dispositions particulières.Footnote 63

Nevertheless, Lueder expressed reservations about the mapping step of the analogical process. Indeed, he appeared to disagree with some of the relevant dissimilarities identified by the 1868 Diplomatic Conference – although he did not elaborate on this point.Footnote 64 Furthermore, his rather detailed analysis offered mild criticism on the analogical solution adopted at the Conference, suggesting that the transfer step could have been implemented differently. He proposed a more economical approach, advocating for a single provision prescribing the analogical application of the 1864 Geneva Convention to maritime warfare.Footnote 65

During the second session of the 1869 International Conference in Berlin, which focused on voluntary rescue in maritime warfare, the analogy between land and maritime warfare was made explicit with a rare transparency on the analogical process. Dr Steinberg, rapporteur of the committee on signals for rescue vessels, explained the rationale behind the committee’s decision to adopt a common signal to notify rescue vessels to intervene on the battlefield. He stated: “Les Articles additionnels de la Convention de Genève relatifs à la guerre maritime ayant été calqués sur les articles relatifs à la guerre sur terre nous nous placerons pour ces motifs au point de vue de l’analogie.”Footnote 66 Steinberg then identified four critical differences between land and maritime warfare to justify the need for a specific rescue signal at sea. These differences are grounded in the technological context of the time. The first difference touched upon the “action theatre”: on land, soldiers hors de combat could wait for combat to cease before receiving care, whereas at sea, immediate rescue was required in the face of shipwreck. The second difference concerned the scope and evolving nature of war theatres: land warfare was geographically limited by the number of combatants, while maritime warfare could shift in location and scale due to the use of steamboats. The third difference pertained to the nature of military power. On land, military power resided in armed forces, while at sea, it resided in vessels; the destruction of a vessel could end combat, even if the vessel crews were unharmed. The last difference referred to the consequences of defeat: on land, defeated soldiers were typically just wounded, but at sea, they were often also at risk of drowning and thus dying.Footnote 67

Beyond the heritage collection on the First Geneva Convention, subsequent treaties on maritime warfare leave no doubt as to the importance of analogies in their development. At the turn of the twentieth century, the titles of the two Hague Conventions on maritime warfare made the lawmakers’ intent very clear. The 1899 Hague Convention III was entitled Convention (III) for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention of 22 August 1864.Footnote 68 Similarly, the 1907 Hague Convention X – which replaced the 1899 Convention – was titled Convention (X) for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention.Footnote 69 In its 1960 Commentary on GC II, the ICRC emphasized that the maritime conventions were “simply presented as an extension” of the land conventions.Footnote 70 The ICRC has also underlined, in its updated 2017 Commentary on GC II, that the titles of the 1899 Hague Convention III and the 1907 Hague Convention X “reflected the spirit of both Hague Conventions: affirming that the protective rules agreed upon for land warfare extended to armed conflict at sea”.Footnote 71

Hague Convention X was eventually superseded in 1949 by GC II – which “received its own appropriate name” for the first time.Footnote 72 However, the same analogical approach persisted during the 1949 Diplomatic Conference. This approach was generally accepted by the ICRC and by State delegates who voted in favour of GC II,Footnote 73 despite some disagreements regarding specific (dis)similarities between land and maritime warfare, such as those concerning the transfer of prisoners.Footnote 74 Nonetheless, certain State representatives remained broadly sceptical. For instance, during a meeting of Committee I, the French representative argued that the analogy between the two conventions was superficial, asserting that the maritime convention “va beaucoup plus loin et … soulève des questions beaucoup plus importantes de droit international” compared to its land-based counterpart.Footnote 75

From land and maritime warfare to air warfare

Unlike maritime warfare, which is at the very least regulated by GC II regarding the protection of wounded, sick and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea, air warfare is not governed by a dedicated modern IHL treaty. Only two aspects of air warfare are addressed in non-specific IHL instruments:Footnote 76 the protection of medical aircraft, as provided in Articles 36 and 37 of GC I, Articles 39 and 40 of GC II, and Articles 24–31 of AP I;Footnote 77 and the status of aircraft occupants in distress, as regulated by Article 42 of AP I.Footnote 78 The analogical mindset behind these provisions is less immediately apparent than that which informed the development of the maritime conventions (GC II and its predecessor treaties). There is no dedicated air warfare convention whose structure mirrors that of earlier treaties; additionally, the number of relevant provisions is limited, and they are dispersed across GC I, GC II, and AP I. These provisions also differ in form and content from other contemporary IHL norms. Further, the wording of the relevant articles in GC I and GC II is identical. At first glance, it may thus not be obvious that these air warfare provisions are based on analogies with other IHL regimes. Yet, and again, the analysis of historical documents reveals a consistent reliance on analogical reasoning for regulating air warfare (the target), drawing from both land and maritime warfare (the sources).

The retrieval step in this analogical process was neither straightforward nor uniform. In some instances, lawmakers drew from both land and maritime warfare as sources; in others, they debated which of the two was more appropriate. Such divergence is unproblematic, as lawmakers are not required to select one single, exclusive source. Lawmakers do not analogize at the general level of entire domains (in the present case, air warfare and land or maritime warfare). Even if this author identifies one or another entire domain as a source or target to simplify the language in this article, it is more accurate to consider, as previously introduced, that there are multiple analogies with distinct features of a domain as target or source situations.Footnote 79 In other words, there are several sources and targets. Besides, disagreements on the source are to be expected because the retrieval step inherently involves subjective judgement: reasonable lawmakers may reasonably disagree on the most relevant source. Nevertheless, regardless of the source chosen, there is little doubt that analogies played a role in shaping the limited set of IHL provisions on air warfare.

A Commission of Jurists appointed by the 1922 Washington Conference adopted Article 17 of the 1922–23 Hague Rules, which addressed the control of wireless telegraphy in time of war and air warfare. This article provided that the principles applicable to land and maritime warfare should also apply to air warfare.Footnote 80 Although not legally binding, the provision has likely acquired a customary nature over time.Footnote 81 It illustrates that the jurists did not choose between land or maritime warfare as the exclusive analogical source.

The following year, on behalf of the French Ministry of War, Dr Niclot proposed at the 11th International Conference in 1923 that the protection of medical aircrafts be included among the topics for future discussion.Footnote 82 In response, the ICRC prepared a draft convention in anticipation of the 12th International Conference in 1925. This draft adopted the same analogical approach as Article 17 of the Hague Rules: both land and maritime warfare were retained as source analogues. With the assistance of Charles-Louis Julliot, Paul des Gouttes – representing the ICRC – drafted a treaty entitled the Convention Additionnelle à la Convention de Genève de 1906 et à celle de La Haye de 1907 pour l’Adaptation à la Guerre Aérienne des Principes de la Convention de Genève.Footnote 83 Article 1 of the draft Convention stated: “Sont applicables à la guerre aérienne toutes les prescriptions de la Convention de 1906 [land warfare] et de la Xe Convention de La Haye du 18 octobre 1907 [maritime warfare], qui peuvent lui être appliquées, et pour autant qu’elles ne sont pas modifiées par les dispositions suivantes.”Footnote 84 The draft was approved by the 12th International Conference with only minor changes.Footnote 85

Air warfare was not on the official agenda of the 1929 Diplomatic Conference, but both the French and British delegations raised the issue.Footnote 86 The special committee tasked by Commission I with examining sanitary aviation voted, by six votes to one, in favour of incorporating a single provision into the revised Geneva Convention, rather than drafting multiple articles or a separate treaty.Footnote 87 As a result, Article 18 was adopted in the 1929 Geneva Convention for the wounded and sick in the field.Footnote 88 The first paragraph of this provision provides that “[a]ircraft used as means of medical transport shall enjoy the protection of the Convention during the period in which they are reserved exclusively for the evacuation of wounded and sick and the transport of medical personnel and material”.Footnote 89 The incorporation of Article 18, which forms the chapter relating to medical transports together with Article 17 on mobile medical formations, reflects IHL lawmakers’ main intent to analogize air warfare with land warfare, and more specifically, medical aircraft with mobile medical units.Footnote 90

The analogy between land and air warfare persisted beyond the Second World War. The relevant provisions of GC I and GC II remain closely aligned with Article 18 of the 1929 Geneva Convention.Footnote 91 However, discussions leading up to the 1949 Geneva Conventions show that maritime warfare was, at times, preferred over land warfare as the analogical source. For example, during the 1947 Conference of Government Experts, the Australian representative proposed in Committee II that civilian aircrew members be analogized with merchant seamen.Footnote 92 Similarly, in preparation for the 1949 Diplomatic Conference, the ICRC suggested defining hospital aircraft by analogy with hospital ships.Footnote 93

Two decades later, the analogical approach remained prominent both for IHL experts and the ICRC. Regarding the status of aircraft occupants (in distress), the ICRC surveyed experts prior to the 21st International Conference in 1969. Some experts compared the “airman in distress” to “a shipwrecked individual”, and “armed parachutists” to “combatant[s] proceeding to attack or in flight”.Footnote 94 Notably, the ICRC report even used the term “air-wrecked”.Footnote 95 Ahead of the second Conference of Government Experts in 1972, the ICRC introduced a new provision on the status of aircraft occupants in its draft additional protocol. The commentary accompanying the draft stated:

This article is entirely new. In the era of The Hague, there was no “vertical” dimension to military operations. Consequently a proposal, which reflects the customs which have grown up since the appearance of air warfare, was formally submitted to the first session of the Conference of Government Experts and at which the situation of airmen in distress was compared to that of the shipwrecked.Footnote 96

Regarding the protection of medical aircraft, the report of the second Conference of Government Experts reveals divergent views, particularly concerning the capture of permanent medical aircraft crews. One expert asserted that such crews should enjoy the same status as hospital ship crews under GC II (i.e., not subject to capture), while others contended that they should be treated like other medical transport personnel under GC I (i.e., subject to capture). The latter opinion was ultimately adopted by Commission I.Footnote 97

The final records of the 1974–77 Diplomatic Conference provide further examples of analogies. During the 39th plenary meeting, the Syrian delegate proposed analogizing a paratrooper to a land soldier attempting to escape – both, in his view, should be excluded from protection. However, he rejected the analogy between “an aviator trying to return to his territory” and a shipwrecked person, arguing that the former is “hors de combat and attempting to escape”, and therefore should not benefit from protection.Footnote 98 During the 47th meeting of Committee II, the Canadian representative analogized a “forward helicopter” to a “wheeled ambulance”.Footnote 99 Presenting a series of draft articles to Committee III, the ICRC affirmed:

If the Conference went no further than the Conference of Government Experts on the Reaffirmation and Development of International Humanitarian Law applicable in Armed Conflicts in resolving the problems of humanitarian rules at sea and in the air, it would be desirable for it at least to adopt a resolution inviting parties to a conflict to apply those rules by analogy. Footnote 100

Note that the prohibition on attacks against aircraft occupants in distress is not only established by Article 42 of AP I but also forms part of customary international law, as confirmed by Rule 48 of the ICRC Customary Law Study.Footnote 101 In its commentary to the rule, the ICRC highlights that “[a] parallel can be drawn here with the shipwrecked, who are considered to be hors de combat … even though they may swim ashore or be collected by a friendly ship and resume fighting”. The ICRC adds that “persons bailing out of an aircraft in distress have been called ‘shipwrecked in the air’”.Footnote 102

To conclude on the regulation process of air warfare, these instances of analogical reasoning confirm that drawing analogies between air warfare and either land warfare – especially when addressing medical aircraft – or maritime warfare – especially when addressing aircraft occupants in distress – was the approach of both the lawmakers and the ICRC in respectively adopting or supporting successive treaty provisions and in shaping customary international law.

From prisoners of war to civilian internees

It is hardly a secret that Title II, Section IV of Geneva Convention IV (GC IV)Footnote 103 on the protection of civilians closely mirrors Title III, Section II of Geneva Convention III (GC III) on the protection of prisoners of war (PoWs).Footnote 104 Even a non-expert in IHL would likely notice the striking similarities upon a first reading of the two conventions. In its 1958 Commentary on GC IV, the ICRC emphasized that “the regulations applicable to civilians reproduce almost word for word the regulations relating to prisoners of war”.Footnote 105 The updated 2025 ICRC Commentary on GC IV also underlines that, “[f]rom the beginning, protections for civilians, in particular for civilian internees, were modelled on the protections afforded to prisoners of war”.Footnote 106

This resemblance was not achieved by chance: IHL lawmakers built Title II, Section IV of GC IV upon an analogical reasoning between, on the one hand, the internment of PoWs and, on the other, the internment of civilians. In its preliminary remarks to the four Geneva Conventions, the ICRC explicitly indicated that “Section IV deals with internment. It is divided into twelve Chapters, the contents of which are in general analogous to the provisions adopted for prisoners of war.”Footnote 107 Thus, in the analogical process, the internment of PoWs served as the source situation, while the internment of civilians constituted the target situation. Historical documents and preparatory works contain numerous direct references to this analogical reasoning.

The idea of analogizing civilian internees with PoWs dates back to 1934. The Tokyo Draft International Convention – concerning the condition and protection of civilians of enemy nationality in the territory of a belligerent or in a territory occupied by it – articulated the analogical reasoning in one single provision. Article 17 of the Tokyo Draft stipulated that “the Convention of July 27, 1929, concerning the treatment of Prisoners of War is by analogy applicable to Civilian Internees”.Footnote 108 The same idea was considered crucial at the 1946 Preliminary Conference of National Red Cross SocietiesFootnote 109 and at the 1947 Meeting for the Study of Treaty Stipulations Relative to the Spiritual and Intellectual Needs of Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees.Footnote 110 During both gatherings, however, the need for (additional) rules specific to civilian internment was also debated. The Preliminary Conference was divided on this issue,Footnote 111 while the 1947 Meeting “decided that several distinct rulings should be adopted for Civilians”.Footnote 112 Similarly, Commission III of the 1947 Conference of Government Experts – tasked with examining the protection of civilians in wartime – argued that simple cross-referencing to the legal regime applicable to PoWs was insufficient. The Commission maintained that most provisions concerning PoWs should be adapted when being transferred to civilian internees.Footnote 113

By the time of the 1949 Diplomatic Conference, the analogy between PoWs and civilian internees was largely taken for granted.Footnote 114 Rather than listing the positive references to this reasoning, it is more revealing to highlight the negative reactions, which underscore the centrality of the analogical mindset among lawmakers. Even those who opposed the analogy felt compelled to refer to it. They did not reject the relevance of analogizing as such, but they instead used analogical reasoning (and thus vocabulary) to highlight critical differences, invalidate the suggested analogy and justify their objections. For instance, during the 20th meeting of Committee III, the Canadian representative affirmed that “the analogy between internees and prisoners of war had been carried too far” in the context of war allowances. He contended that enemy aliens should not receive allowances similar to those granted to PoWs, as the latter “had earned a standard of treatment which had not been earned” by the former.Footnote 115 At the 22nd meeting of the same forum, the Canadian delegate also declared, in relation to another issue, that

[i]nternees in the territory of a belligerent are normally people who have made their homes in that country, so that there is not the slightest resemblance between the resettlement problem of the German prisoner of war who has been captured by, say, the Canadian army and brought to Canada and the problem of the German civilian who made his home in Canada as an immigrant twenty-five years ago and who was interned in the last war because he loved Hitler too much. There is no comparison, and this continual pressure to get into this Civilian Convention everything that appears in the Prisoners of War Convention is completely illogical.Footnote 116

In the same vein, the British representative considered that, in contrast to PoWs, civilian internees should not enjoy more favourable treatment than the Detaining Power’s own citizens. He remarked at the 31st plenary meeting that “it would be difficult to find a falser analogy than that between prisoners of war and internees in the present connection”.Footnote 117

In conclusion, the similarities between GC III and GC IV regarding internment are not historical accidents, but rather are the result of a deliberate choice made by the lawmakers in the drafting of the Conventions. Lawmakers intentionally constructed an analogical bridge between, on the one hand, the existing and revised legal regime for PoWs – dating back to the 1929 ConventionFootnote 118 – and, on the other, the newly established regime for civilian internees.

From international to non-international armed conflicts

Among the hundreds of articles in the Geneva Conventions of 1949, only one common provision addresses NIACs: common Article 3.Footnote 119 AP I contains 102 articles applicable to IACs, whereas Additional Protocol II (AP II) includes twenty-eight articles which govern certain types of NIACs.Footnote 120 This significant imbalance in the number of provisions between the legal regimes applicable to IACs and NIACs may obscure the analogical connections between them. Nevertheless, the preparatory works of the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols show that the treaty legal framework for NIACs was conceived through analogical reasoning with IACs. Thus, in the analogical process, NIACs served (and often still serve) as the target situation, while IACs functioned as the source.Footnote 121 This article does not aim to provide a comprehensive historical account of the development of common Article 3 and AP II, but the following paragraphs, while not exhaustively indexing all analogical occurrences throughout the drafting history of common Article 3 and AP II, pinpoint a few key instances of analogical reasoning to highlight its importance in the lawmakers’ decisions.

During the 1949 Diplomatic Conference, the Joint Committee – tasked with examining the common articles to all four Geneva Conventions – established a special subcommittee to consider, among other issues, the applicability of IHL to NIACs. This subcommittee instructed two successive working parties to draft a new common provision addressing this matter. According to the report of the 23rd meeting of the special subcommittee, the second working party ultimately abandoned the analogy between NIACs and IACs, even though it had initially explored this approach:

The application of the Civilians Convention raised the greatest difficulties. After having successively abandoned the idea of an application by analogy – which was considered dangerous, because it permitted too much freedom of interpretation – and that of an enumeration of the Articles which would be inapplicable in the case of civil war – a system which appeared complicated and of doubtful efficacy – the Working Party considered it advisable to impose on the Contracting States only one obligation; that of complying in all cases with the underlying humanitarian principles of the Convention.Footnote 122

The Joint Committee’s report to the plenary session confirmed that the lawmakers in this committee considered but ultimately rejected the idea of analogizing NIACs with IACs.Footnote 123 This is also clear from the fact that the Committee endorsed the second working party’s final determination to invalidate the analogy with IACs: indeed, the draft prepared by the said second working party – which “lays down a minimum of humanitarian rules which both Parties [to a NIAC] are bound to respect” – was amended by the special subcommittee and subsequently approved by the Joint Committee itself.Footnote 124 Thus, in 1949, NIACs were not considered sufficiently similar to IACs to transfer the latter’s legal regime to the former. Nonetheless, even if considered unsuccessful, the analogical reasoning between the two types of armed conflicts was at the core of the discussions.

In 1972, the ICRC submitted two draft protocols to government experts, which “contained identical, or at least very similar, provisions on certain subjects”.Footnote 125 Commission II of the Conference of Government Experts examined the protection of victims in NIACs. The first issue debated was the “degree of similarity in the protection of victims of both types of conflict and hence the question of whether one or two protocols are needed”.Footnote 126 While some experts favoured a single protocol applicable to both IACs and NIACs, many others supported the adoption of two distinct protocol instruments – these experts argued that the “basic principles” of AP I “could be adapted, or purely and simply adopted” in AP II.Footnote 127 They identified two crucial differences between IACs and NIACs: the “political aspects of the two types of conflict” and the “conditions affecting the implementation of the two Protocols”.Footnote 128 Beyond these occurrences, the analogical vocabulary is present in the report of the second session of the Conference.Footnote 129

The final version of AP II, with its twenty-eight articles, is significantly shorter than AP I. This disparity may suggest a lack of analogical intent, but this would be an incorrect conclusion. The approved version of AP II was the result of a last-minute compromise – the penultimate draft of AP II more largely resembled AP I and illuminates the analogical mindset between IACs and NIACs in the drafting process of the adopted version of AP II. In addition, several State delegates referred to analogical reasoning during the 1974–77 Diplomatic Conference.Footnote 130 The 1987 ICRC Commentary on AP II notes that

approximately two weeks before the end of the Conference, the draft Protocol II … was more complete and detailed than the ICRC draft. By analogy with draft Protocol I, some provisions had been added …; other articles … had been transposed from draft Protocol I to draft Protocol II in such a way that the wording was no longer restricted to basic rules.Footnote 131

However, a number of States were opposed to such a protective draft, either because it threatened national sovereignty and the principle of non-interference with internal affairs, or because it was too detailed and difficult to apply in NIACs.Footnote 132 There was thus a real risk that no consensus at all on AP II would see the light of day at the 1974–77 Diplomatic Conference. To avoid a complete deadlock on NIACs, the Pakistani delegation suggested a simplified (or rather reduced) version of AP II on 31 May 1977.Footnote 133 The remaining provisions “did not include any drafting modifications” compared to the penultimate draft of AP II;Footnote 134 therefore, the remnants of this draft still draw on analogies with IACs, even though the shrinkage of provisions makes it less explicit.

To conclude this section on the first category of analogies (analogies before IHL norms), it is clear that analogies underpin many well-known IHL norms. Although States are the formal IHL lawmakers, their representatives are human beings – and, like all human beings, they naturally tend to reason by analogy. As such, IHL lawmakers very frequently rely on analogical reasoning to design new rules. As the following section will show, they also sometimes oblige or invite those who apply or interpret the law to do the same.

Analogies in IHL norms

The second category in the taxonomy encompasses all analogies that are directly embedded in IHL norms. In a chronological perspective, there is thus a sort of simultaneity between analogies and IHL norms because the former are provided for in the latter. In this category, IHL norms are not the outcome of analogical reasoning; rather, these norms expressly require or encourage such reasoning. Lawmakers do not reason by analogy themselves; instead, they impose or suggest such reasoning upon any entity or individual applying or interpreting the relevant norm.Footnote 135 Through the decision of the lawmakers, this entity or individual becomes the analogizer. In other words, and in contrast to the first category of analogies, the analogizers are here the norm-appliers or norm-interpreters, not the lawmakers.

However, lawmakers still initiate the analogical reasoning. Indeed, they conduct the retrieval step and identify one or several sources for the analogies, while the norm-appliers or norm-interpreters retain freedom regarding the mapping and transfer steps. To clarify the point, if the lawmakers tell norm-appliers and norm-interpreters what to do (i.e., an analogy with one or several specific sources), they do not tell the latter how to do it. Norm-appliers and norm-interpreters still enjoy some discretion and subjectivity in the analogical process.

In this second category, analogies thus constitute a mandatory or authorized method of reasoning in the application of an IHL norm. Collected data reveal three options for the lawmakers: they can either explicitly require, implicitly require or implicitly propose an analogical reasoning. The following subsections provide examples for each option.

Express obligation

IHL lawmakers sometimes adopt a norm using explicit language that compels the norm-appliers or norm-interpreters to reason by analogy. Such express obligations to reason by analogy are rare. The 1949 Geneva Conventions offer a very good example, although this approach was later abandoned in AP I. Articles 4 of GC I and 5 of GC II provide that

[n]eutral Powers shall apply by analogy the provisions of the present Convention to the wounded and sick [and shipwrecked], and to members of the medical personnel and to chaplains of the armed forces of the Parties to the conflict, received or interned in their territory, as well as to dead persons found.Footnote 136

Interestingly, the US Law of War Manual mentions these provisions as examples of “treaty requirement[s] to apply rules by analogy”.Footnote 137

In its 2016 Commentary on GC I, the ICRC notes that “[s]ince, by definition, neutral Powers are not Parties to the international armed conflict, the application expected of them is ‘by analogy’, as if they were Parties to the conflict (mutatis mutandis)”.Footnote 138 In other words, the drafters of the Geneva Conventions identified the source situation as the reception and detention of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked by an adverse belligerent party, and the target situation as their reception and internment by a neutral power. However, they did not specify the (dis)similarities between the source and target situations (mapping), nor did they explain how to apply the provisions of GC I and II to neutral powers (transfer). Consequently, norm-appliers and norm-interpreters – including neutral powers and individuals such as judges – retain a degree of discretion in their analogical reasoning.

Although the terminology in Articles 4 of GC I and 5 of GC II was ultimately adopted, the phrase “by analogy” was not universally accepted and sparked debate during the 1949 Diplomatic Conference. The UK, in particular, was highly critical, describing the phrase as “difficult to interpret”, “confusing the minds of serious students”, “completely loose” or “far too wide”.Footnote 139 The UK questioned the retrieval step in the analogical process and emphasized a fundamental difference between the source and target: while belligerents are fighting one another in the source situation, neutral powers provide assistance in a charitable manner in the target situation.Footnote 140 At the 26th meeting of Committee I, the British delegate suggested an alternative: to explicitly list the provisions applicable to neutral powers, rather than referring to an analogy. This alternative did not convince all State representatives, including the delegate from the USSR, who responded that “no list could provide for all possible cases”.Footnote 141 The British proposal was eventually rejected by seventeen votes to six, with four abstentions.Footnote 142

This was not the last time that the phrase “by analogy” faced opposition. The draft of AP I initially included a provision similar to Articles 4 of GC I and 5 of GC II; State experts retained the same wording during the second session of the Conference of Government Experts in 1972.Footnote 143 However, during the 1974–77 Diplomatic Conference, State delegates reached a different conclusion. Other English-speaking countries, such as Australia, criticized the phrase “by analogy” as ambiguous in the English version (though acceptable in the French version).Footnote 144 While the Drafting Committee also initially chose to maintain the terminology for the sake of consistency,Footnote 145 New Zealand and other sponsoring States submitted an amendment to remove the disputed phrase.Footnote 146 This amendment was adopted by twenty-seven votes to ten, with four abstentions.Footnote 147 As a result, unlike Articles 4 of GC I and 5 of GC II, Article 19 of AP I does not expressly require the norm-appliers or norm-interpreters to employ analogical reasoning. It merely states that “[n]eutral and other States not Parties to the conflict shall apply the relevant provisions of this Protocol to persons protected by this Part who may be received or interned within their territory”.Footnote 148

These historical developments in the drafting of GC I, GC II and AP I clearly highlight some opposition to the phrase “by analogy”, thereby illustrating how analogical reasoning, as an explicit treaty requirement, was undoubtedly at the core of the discussions. These developments also lead us to the next section of this article. The change and deletion of the phrase “by analogy” in AP I was justified by a fear that neutral powers would be considered to be on the exact same footing as belligerent parties, while it was undisputed that some provisions of AP I relating to the protection of persons could not apply to them.Footnote 149 Nonetheless, in its 1987 Commentary on AP I, the ICRC aptly notes that this change was “only a question of wording, for basically it is quite clear that the situation under the Conventions was precisely the same”.Footnote 150 Consequently, if analogical reasoning is, after all, not an express requirement within Article 19 of AP I, the drafters of that provision do implicitly oblige the norm-appliers or norm-interpreters to resort to such reasoning in continuation of Articles 4 of GC I and 5 of GC II. Such an implicit obligation is indeed another option for lawmakers, and one that we shall further explore in the following section.

Implicit obligation

Lawmakers rarely explicitly compel norm-appliers or norm-interpreters to engage in analogical reasoning. They more frequently impose such reasoning in an implicit way, particularly through the legislative technique of open listing.Footnote 151 This technique involves enumerating several situations as examples (or sources), thereby requiring the norm-appliers or norm-interpreters to apply the norm to analogous situations (or targets) not expressly mentioned in the text. In doing so, norm-appliers or norm-interpreters broaden the scope of application of a norm to encompass similar cases or situations.Footnote 152

The selection of examples or sources by lawmakers is far from being a trivial step. Gérard Cornu notes that “un exemple légal n’est pas une application quelconque, mais une illustration choisie pour être topique”.Footnote 153 Actually, lawmakers themselves reason by analogy to guide norm-appliers or norm-interpreters to these specific sources. All the listed sources share a common feature: they exemplify a general legal principle.Footnote 154 To properly reason analogically, norm-appliers and norm-interpreters must first discern the general legal principle underlying the lawmakers’ choice of sources, and then determine whether the target situation constitutes another valid illustration of that principle.

This type of analogy through the legislative technique of open listing is typically signalled by specific vocabulary such as “and (other) similar…” or “and (other/all) analogous…”. Numerous examples can be found throughout history and the current framework of IHL, whether in declarations or treaties. For instance, the 1899 Hague Declaration (IV, 1) states that “[t]he Contracting Powers agree to prohibit, for a term of five years, the launching of projectiles and explosives from balloons, or by other new methods of a similar nature”.Footnote 155 Article 5 of the 1922 Treaty Relating to the Use of Submarines and Noxious Gases in Warfare establishes signatories’ agreement on the prohibition of “[t]he use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and all analogous liquids, materials or devices”.Footnote 156

Another illustrative example is to be found in Article 12 of GC I and of GC II. This common provision obliges parties to armed conflicts to treat and care for wounded, sick or shipwrecked members of the armed forces “without any adverse distinction founded on sex, race, nationality, religion, political opinions, or any other similar criteria” (in French: “sans aucune distinction de caractère défavorable basée sur le sexe, la race, la nationalité, la religion, les opinions politiques ou tout autre critère analogue”).Footnote 157 The 2016 ICRC Commentary on GC I indicates that “[t]he drafters wisely anticipated a dynamic evolution of the catalogue of prohibited criteria and chose a sufficiently open formulation which could accommodate additional grounds”.Footnote 158

Discussions during the 1949 Diplomatic Conference reveal that this kind of wording (“other similar …”/“autre … analogue”) in Article 12 entails analogical reasoning. The Afghan delegation, for instance, objected to the phrase “critères analogues” on the grounds that it did not see any similarity between the explicitly listed criteria.Footnote 159 At the eighth meeting of Committee III, the Afghan delegate argued:

[Q]u’est-ce, à proprement parler, qu’un critère si ce n’est une règle précise, une pierre de touche, qui permet en passant du connu à l’inconnu, procédant par analogie – je souligne ces mots – de discerner dans une situation nouvelle le ou les facteurs qui ramènent la multiplicité des phénomènes à un principe juridique connu. S’il n’y a pas d’affinité profonde entre les termes …, il ne saurait y avoir non plus de règle fixe, de critère. Il n’y a plus de place que pour la confusion juridique, disons plutôt la confusion tout court. … Ainsi, on supprimerait l’expression “critères analogues” qui me paraît tout à fait équivoque.Footnote 160

The Danish representative disagreed, however, stating at the 24th plenary meeting that

it is [not] very difficult to discern an analogy between the different cases. Other cases could be imagined, for instance, social differences between the rich and the poor, or the caste system in certain countries. The analogy is simply that it is a question in each case of differences between human beings.Footnote 161

In any case, this type of wording now appears to be part of customary international law, as reflected in Rule 88 of the ICRC Customary Law Study.Footnote 162

APs I and II provide further examples of an open-ended list. Article 51(5)(a) of AP I prohibits

an attack by bombardment by any methods or means which treats as a single military objective a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives located in a city, town, village or other area containing a similar concentration of civilians or civilian objects.Footnote 163

Article 1(2) of AP II provides that “[t]his Protocol shall not apply to situations of internal disturbances and tensions, such as riots, isolated and sporadic acts of violence and other acts of a similar nature, as not being armed conflicts”.Footnote 164

In contrast to the set of examples in the previous section (in which lawmakers explicitly require norm-appliers and norm-interpreters to engage in analogical reasoning), the language used in these examples containing open-ended lists does not initially appear to be particularly compelling. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to argue that norm-appliers are under an implicit obligation to apply these norms to cases that are analogous to those explicitly contemplated by the lawmakers. They cannot ignore a blatant similarity between two situations, one foreseen by the lawmakers and the other not, and choose not to apply the relevant IHL norm to the latter. To illustrate this point with some of the previous examples, when confronted with new means of warfare that are similar to existing ones whose use is already prohibited under a norm with an open-ended list, norm-appliers cannot simply disregard this similarity and associated prohibition, and proceed to use these new means on the battlefield. There is good reason to argue that such use would constitute a violation of IHL. Similarly, it is unacceptable and arguably unlawful for norm-appliers to discriminate against the wounded and sick based on a new criterion not explicitly mentioned by the lawmakers when that criterion closely resembles those already provided.

Implicit invitation

In addition to compelling norm-appliers and norm-interpreters to reason by analogy, IHL lawmakers may alternatively invite them to do so. Such an invitation amounts to an authorization or a discretionary faculty for norm-appliers, rather than an obligation to analogize. The collected data indicate that this type of invitation is implicit in IHL norms.

A paradigmatic example of this subcategory can be found in common Article 3, which reflects the analogy at the origin of this provision and of AP II – namely, the analogical reasoning between IACs and NIACs.Footnote 165 Paragraph 3 of common Article 3 states that “[t]he Parties to the conflict should further endeavour to bring into force, by means of special agreements, all or part of the other provisions of the present Convention”.Footnote 166 This provision encourages parties to a NIAC to adopt special agreements that transfer norms applicable to IACs to NIACs. As Marco Sassòli has noted, it thereby prompts parties to engage in analogical reasoning between IACs and NIACs through the mechanism of special agreements.Footnote 167 Although this invitation to analogy does not appear to be expressly articulated in the preparatory works of the Conventions,Footnote 168 it nonetheless emerges as the practical effect of the provision. Beyond common Article 3, Article 19(2) of the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property similarly contains an implicit invitation to analogize through special agreements.Footnote 169

In this second category of analogies (analogies in IHL norms), lawmakers still initiate the analogical reasoning process, either by imposing it (as in the first two subcategories) or by suggesting it (as in the third subcategory) to the norm-appliers and norm-interpreters. However, as will be shown in the third and final category of this taxonomy, lawmakers are not always involved in the analogical process.

Analogies after IHL norms

IHL lawmakers sometimes adopt norms that subsequently appear too vague, or legal regimes that later prove insufficient. As a result, norm-appliers and norm-interpreters often try to resolve these challenges, particularly through legal interpretation.Footnote 170 Among various interpretive tools, analogical reasoning is a highly appreciated option (albeit one that may occasionally have a creative, quasi-legislative dimension), responding to a need for clarification in practice. In this third category of the taxonomy, analogical reasoning does not arise directly from the content of the norm itself (second category); rather, it emerges post hoc, in the context of the norm’s application and interpretation. In other words, from a chronological standpoint, IHL norms come first, and analogies only second.

In this third category of analogies, as in the second category (analogies in IHL norms), norm-appliers or norm-interpreters act as the analogizers – but in this third category, they enjoy full discretion in the analogical process. In the absence of any directive from lawmakers, norm-appliers or norm-interpreters independently retrieve a source, map it onto the target, and transfer the legal solution from the source to the target.

The following subsections will present two sets of examples. The first set refers to IHL norms that contain undefined concepts which analogy helped to clarify, while the second set relates to IHL norms whose scope of application was extended through an analogy. In the first case, the target is the situation referred to in the norm that remains vague or ambiguous under IHL. In the second case, the target is the situation which is excluded from the norm’s scope of application before any analogical reasoning.

Definition of concepts

Regarding the first scenario described above, numerous examples of such analogies have emerged following the adoption of the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols. Norm-appliers and norm-interpreters quickly recognized that key concepts were left undefined in the treaties, necessitating interpretation to enable their practical application. This gap was often addressed through analogy with earlier or contemporary legal instruments that provided definitions for similar concepts and situations in different contexts. In his work on analogical reasoning in international law, Jean Salmon wrote that the source “est fréquemment trouvé[e] dans des textes conventionnels distincts (antérieurs, contemporains ou postérieurs) de celui qui fait l’objet [de la cible], mais qui portent sur la même matière ou la même notion juridique”.Footnote 171

Instances of third-category analogies can thus be found in successful attempts to clear up the remaining grey areas in the dense text of the four Geneva Conventions. To mention just one, GC IV refers to “occupied territory/ies” approximately forty times without offering a definition of the phrase.Footnote 172 It is now well accepted that this concept can be interpreted by analogy with Article 42 of the Hague Regulations, which now have a customary nature.Footnote 173 This provision states that “[t]erritory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army”.Footnote 174 In its 2025 updated Commentary on GC IV, the ICRC declares that “the notion of occupation is derived from Article 42”.Footnote 175 A similar approach was adopted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in its Kordić and Čerkez judgment of February 2001. The Trial Chamber affirmed the following:

The question arises what is meant by the term “occupied territory” for the purposes of the application of Article 53 of Geneva Convention IV. … In light of the absence of a definition of the term “occupied territory” in the Geneva Conventions, and considering the customary status of the Hague Convention (IV) and the Regulations attached thereto, the Trial Chamber will have recourse to that Convention in defining the term.Footnote 176

The legal developments since the adoption of AP II are particularly illustrative of this third category of analogies. As previously noted, AP II retains elements of a more comprehensive draft that was more explicitly inspired by AP I.Footnote 177 Many provisions, including definitional clauses, were ultimately deleted.Footnote 178 As a result, AP II employs several terms – such as “military objectives” (Article 15) and “medical personnel” (Articles 9 and 12) – without defining them. This has led norm-appliers and norm-interpreters to rely on definitions provided in AP I.Footnote 179 For example, in its Statement of Understanding dated 20 November 1990, the government of Canada declared that it “understands that the undefined terms used in Additional Protocol II which are defined in Additional Protocol I shall, so far as relevant, be construed in the same sense as those definitions”.Footnote 180

Analogical reasoning with prior legal regimes is a common feature of IHL and extends beyond the frameworks of the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols. To take one such example, Protocol III to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons – the Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Incendiary Weapons – uses the notions of “civilian” and “civilian population” but does not define them, even in the definitional provision of Article 1. Therefore, upon ratifying Protocol III in February 1995, the UK stated that “[t]he terms ‘civilian’ and ‘civilian population’ have the same meaning as in Article 50 of the First Additional Protocol of 1977 to the 1949 Geneva Conventions”.Footnote 181

While the above examples show analogies with definitions already established in IHL, norm-appliers and norm-interpreters have sometimes drawn analogies with definitions established under other branches of international law. International judicial practice offers a salient example of this. Clear analogical occurrences with other branches of international law are relatively limited in international case law because States have the primary law-making authority and most significant legal reforms have happened through conventions or customary law.Footnote 182 In addition, international judges rarely acknowledge that they are filling a legislative gap and resorting to analogical reasoning.Footnote 183 However, they offer some interesting examples of analogy, as illustrated by the following paragraphs.

IHL lawmakers did not define torture in wartime (target); consequently, the ICTY interpreted the notion of torture under IHL by analogy with international human rights law (IHRL). It retrieved a source (i.e., the situation of torture in peacetime), mapped it onto the target, and transferred the legal solution of the source to the target – i.e., it transferred and adapted the legal definition of torture under IHRL to IHL.Footnote 184

This example is well known among IHL experts, although it is not typically analyzed through an analogical lens, as the ICTY judges did not present their reasoning as such. Nevertheless, the language used by the ICTY judges to explain their reasoning clearly reflects the steps of analogical reasoning. In the 2001 Kunarac judgment, the Trial Chamber held that “[b]ecause of the paucity of precedent in the field of international humanitarian law, the Tribunal has, on many occasions, had recourse to instruments and practices developed in the field of human rights law”.Footnote 185 It further noted that “notions developed in the field of human rights can be transposed in international humanitarian law only if they take into consideration the specificities of the latter body of law”.Footnote 186 The following year, in the 2002 Krnolejac judgment, Trial Chamber II emphasized that

[i]n attempting to define an offence or to determine whether any of the elements of that definition has been met, the Trial Chamber is mindful of the specificity of international humanitarian law. … In particular, when relying upon human rights law relating to torture, the Trial Chamber must take into account the structural differences which exist between that body of law and international humanitarian law, in particular the distinct role and function attributed to states and individuals in each regime. However, this does not preclude recourse to human rights law in respect of those aspects which are common to both regimes. Footnote 187

These excerpts reveal that the ICTY employed terms such as “structural differences”, “common aspects” and “specificities” – all of which are central to the mapping process. Moreover, the use of verbs such as “transpose” closely corresponds to the transfer process. It is difficult to deny that the ICTY reasoned by analogy to define torture under IHL, and this definition, inspired by IHRL, now appears to be accepted as part of customary IHL.Footnote 188

Extension of applicability