Psychiatric advance directives have shown benefit in reducing rates of detention to hospital, supporting patients in communicating their preferences and improving therapeutic relationships. Reference Barrett, Waheed, Farrelly, Birchwood, Dunn and Flach1–Reference Gergel, Das, Owen, Stephenson, Rifkin and Hindley5 The Independent Review of the Mental Health Act has recommended statutory advance directives to promote patient choice and autonomy. Reference Wessely, Gilbert, Hedley and Neuberger6

We use the term psychiatric advance directives in reference to previous research as our focus is on advance directives in mental health. In the USA, Germany and New Zealand the implementation of psychiatric advance directives has been challenging. Reference Swartz, Swanson, Easter and Robertson7–Reference Thom, Lenagh-Glue, O’Brien, Potiki, Casey and Dawson9 Procedural problems, mistrust, poor understanding, lack of support from professionals and long completion time have been reported as barriers, whereas clinician facilitation, better training and awareness featured as enablers in previous research. Reference Swartz, Swanson, Easter and Robertson7,Reference Lenagh-Glue, Potiki, O’Brien, Dawson, Thom and Casey10–Reference Lequin, Ferrari, Suter, Milovan, Besse and Silva17

Studies found that patients generally viewed psychiatric advance directives positively. Reference Gergel, Das, Owen, Stephenson, Rifkin and Hindley5,Reference Maître, Debien, Nicaise, Wyngaerden, Le Galudec and Genest18 However, professionals remain concerned that patients may have poor understanding of their care plan and make choices that aren’t in their best interest. Reference Nicaise, Lorant and Dubois19–Reference Farrelly, Lester, Rose, Birchwood, Marshall and Waheed22 Limited literature indicates that female gender, older age, higher levels of education, higher socioeconomic status and willingness to be admitted to hospital are associated with better engagement with psychiatric advance directives. Reference Choi, Kim and McDonough23,Reference Gowda, Noorthoorn, Lepping, Kumar, Nanjegowda and Math24

In the East London NHS Foundation Trust (ELFT), according to the information obtained from electronic patient records, only one in nine patients on a Care Programme Approach (CPA) had their contingency safety plan identified as an advance directive in 2019. Following NHS England’s decision to move away from the prescriptive CPA framework for the provision of mental healthcare, psychiatric advance directives can be a valuable tool for prospective, co-produced care planning. 25 Our study therefore aims to assess practice in using psychiatric advance directives for patients in the ELFT who received care under CPA provision, to evidence best practice decisions.

Method

Design and aim

This retrospective service evaluation analysed routine care data from electronic health records to investigate the prevalence of psychiatric advance directives among patients receiving care in community mental health services within the ELFT under the CPA, and to identify factors associated with the clinical application.

Participants and inclusion criteria

The study population consists of all patients aged 18–75 years who were managed under the CPA in Community Mental Health Services within the ELFT between 2021 and 2022. According to the CPA policy, this includes individuals with complex mental health needs, 25 and it can therefore be argued that patients within this cohort would benefit from and could be expected to have advance directives in place.

Ethics

Based on the guidance from the Health Research Authority, consent was not necessary for this study (service evaluation of routinely collected clinical data). The Governance and Ethics Committee for Studies and Evaluations of the ELFT approved the access and use of anonymous data for service evaluation (ethics committee reference number: G2007d).

Procedure

We submitted a request to the data informatics team at the ELFT to obtain a pseudonymised data set pertaining to the following parameters in our sample: patient demographics (gender, age, ethnicity and housing status), clinical data (ICD-10 code for primary diagnosis and additionally recorded diagnoses, cluster code according to the Mental Health Clustering Tool, number of previous hospital admission, patient-reported outcome and experience data from the DIALOG Scale), service-level data (locality within ELFT) and the advance directive status recorded. Within ICD-10 code data, we included adverse social circumstances and personal history of non-adherence as separate categories for analysis, because of their relevance to the research question.

Advance directive status at the ELFT is recorded routinely on the safety plan for patients. The completion of the safety plan includes aspects of personalised advance directives optionally. The patient can then choose the option ‘this is my advanced directive’. Electronic patient records have a tick box embedded and this then pulls through to the patient portal front page. It also appears as a statement on the printed version of the safety plan for the patient.

Data cleaning

There were 70 different ethnicity values recorded, which were grouped into five broad categories: White, Asian and Asian British, Black and Black British, and Mixed race, as well as any other ethnic group. Housing status data had over 40 different values and was categorised into domiciled, healthcare facilities, socio-therapeutic facilities and homeless or temporary accommodation. Within Trust directorates, Luton, Bedfordshire and Luton and Bedfordshire were combined into one category. The allocated cluster was categorised according to the super-cluster differentiation into psychotic, non-psychotic and organic. Finally, the number of previous hospital admissions was analysed by allocating them into range categories, including no admissions, one to four admissions, five to nine admissions and ten or more admissions.

DIALOG measure

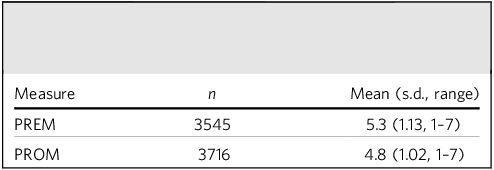

The DIALOG questionnaire has 11 items. Reference Priebe, Kelley, Golden, McCrone, Kingdon and Rutterford26 For the purpose of this analysis and meaningful interpretation, we analysed DIALOG items according to the evidence base with categories of patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) and patient-reported experience measure (PREM). PROM is the mean score for questions measuring satisfaction with mental health, physical health, job situation, accommodation, leisure, relationships, friendships, personal safety and finances. PREM is the mean score for questions measuring satisfaction with treatment, including medication, practical help and meetings.

Statistical analysis

The study used SPSS version 25 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) for data analysis. Descriptive statistics was used to provide an overview of the data. Missing data was addressed with multiple imputation and pooled data was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were found to be normally distributed and were analysed with the independent t-test. Categorical variables were analysed with binomial logistic regression. Independent variables were analysed with binomial logistic regression. No statistical correlation was found between any of the variables.

Missing data analysis was conducted on the data-set to assess percentage of missing data. We considered data in all categories that were not recorded for any reason as missing data. Missing data were addressed with the fully conditional specification method multiple imputation of the six missing variables. Five iterations were executed in the imputation. Pooled data was used for binomial logistic regression.

Results

Demographic, clinical and service-level characteristics

There were a total of 4807 records identified as patients under the CPA within the Trust for the index time period of the study. Of these, a sample size of 4563 records showed an age range from 18 to 75 years and were included for analysis. A total of 1425 patients (31.2%) had an advance directive.

In the three East London localities, we found an equal number of patients on the CPA (Newham: n = 576, 12.6%; City and Hackney: n = 829, 18.2%; Tower Hamlets: n = 719, 15.8%), whereas the Luton/Bedfordshire locality had the highest percentage of patients on the CPA (n = 2018, 44.2%) and forensic service had the lowest (n = 334, 7.3%).

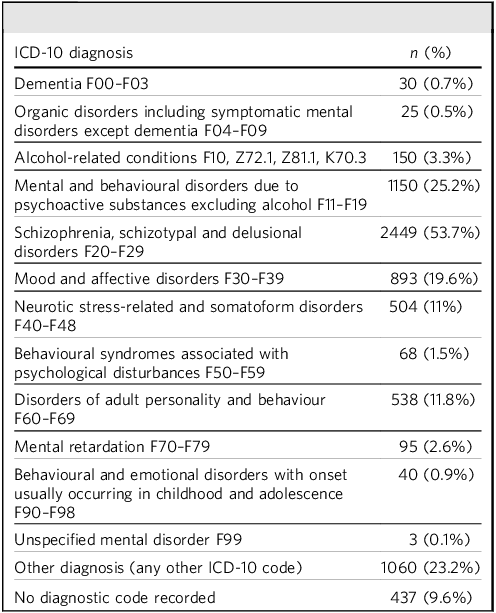

Patients were mostly male (56.9% male, 43.1% female), and the average age was 42.1 years (s.d. 14.3, range 18–75). Ethnicity distribution was as follows: White n = 2017, 44.2%; Asian or Asian British n = 881, 19.3%; Black or Black British n = 1042, 22.8%; Mixed race n = 203, 4.4%; other ethnic group n = 218, 4.8%; not known n = 202, 4.4%. Most patients were domiciled (n = 2952, 64.7%), living in healthcare facilities (n = 313, 6.9%), living in socio-therapeutic facilities (n = 188, 4.1%) or in homeless or temporary accommodation (n = 185, 4.1%), and the housing status was not recorded for (n = 925, 20.3%). The most common diagnosis among patients was within the ICD 10 F20–F29 category of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (53.7%). A total of 23.5% of patients were recorded having a personal history of non-adherence with medication (ICD-10 code Z91.1) and 4.3% of patients were recorded as having adverse social circumstances (ICD-10 code Z55–65). Most patients were within the psychotic cluster (69%), followed by non-psychotic (n = 874, 19.2%), organic (n = 45, 1%) and no cluster recorded (n = 495, 10.8%). Most patients had between one and four hospital admissions (n = 2413, 52.9%), followed by no admission recorded (n = 1932, 42.3%), four to nine admissions (n = 189, 4.1%) and ten or more admissions (n = 29, 0.6%). The average PREM score was 5.3 and average PROM score was 4.8.

Predictors of advance directive status

All of the above demographic, clinical and service characteristics were included in the model.

Categorical variable analysis

Binomial logistic regression analysis was run on pooled multiple imputation data to analyse categorical variables to identify predictors for advanced directive status.

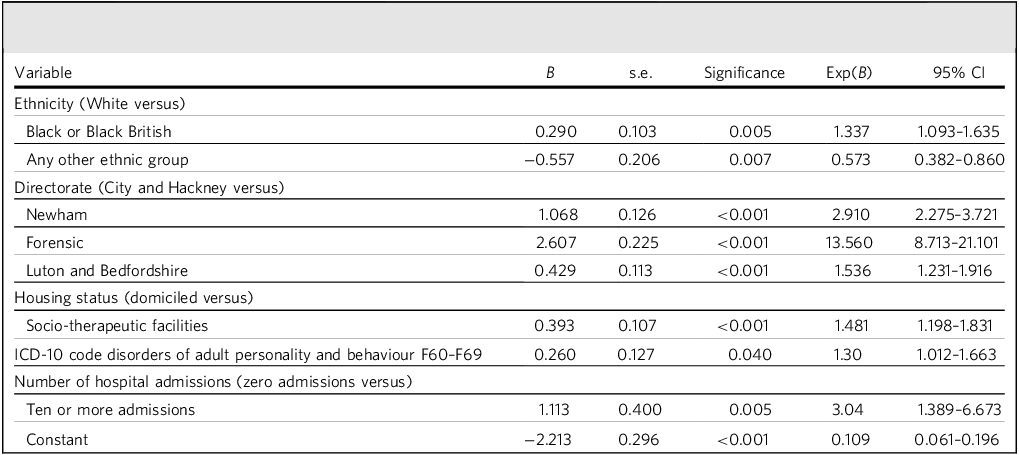

Tables 1 and 2 include the distribution of diagnoses in the sample and mean patient-reported measures, respectively. Table 3 includes five variables that were found to be predictors for advance directive status. Black or Black British ethnicity was positively associated with having an advance directive. In contrast, being of any other ethnic group (other than White, Asian, Black or Mixed race) was negatively associated with having an advance directive. Patients in directorates Newham, forensic services and Luton and Bedfordshire were more likely to have advance directive in place compared with City and Hackney. Of these, being treated in forensic services had the highest likelihood, with an odds ratio of 13.560 (95% CI 8.713–21.101). Having a diagnosis of disorders of adult personality and behaviour was positively associated with having an advance directive. Patients who had ten or more hospital admissions were around three times more likely to have advance directive compared with patients who had no admissions.

Table 1 Distribution of ICD-10 diagnoses

Table 2 Mean patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) and patient-reported experience measure (PREM)

Table 3 Predictors of advance directive status (including patient-reported outcome measure and patient-reported experience measure in analysis)

Engagement with DIALOG and advance directive status

We defined engagement with DIALOG as having at least one DIALOG score recorded. A total of 3738 (81.9%) patients had engagement with DIALOG, with 825 (18.1%) patients having no DIALOG responses recorded. The binary logistic regression analysis was re-run with the same above variables, but PROM and PREM scores were excluded from the analysis and engagement with DIALOG was included as a variable instead. Engagement with DIALOG was found to be a positive predictor of advance directive status, with an odds ratio of 2.690 (95% CI 2.1156–3.355). Other variables yielded similar results as the previous analysis, and summary of predictors is included in the Supplementary Material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2025.10172.

Continuous variable analysis

A pooled independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the average PREM and PROM scores for groups of patients with and without an advance directive. There were statistically significant differences in the mean PREM scores (mean difference = 0.039, 95% CI 0.096–0.248) and PROM scores (mean difference = 0.032, 95% CI 0.173–0.299).

Discussion

This study evaluates a sample from a representative NHS Trust, contributing to the limited evidence base on the prevalence of psychiatric advance directives. We found that 31% of our patient sample had an advance directive in place. The population was predominantly male (56.9%), with an average age of 42 years. We are unable to compare our uptake against national or regional standards because of a lack of available data on advance care planning in mental health. Audits within Kent and Medway Partnership Trusts in 2009 and 2014 found that 10% of patients under the enhanced CPA had advance directive. Reference Harman-Jones, Askari, Isaac-Momoh, Adebowale and Sarfarz27 In Australia, a specialist memory clinic reported advance care plan completion at 8.8% among older adults, Reference Lewis, Rand, Mullaly, Mellor and Macfarlane28 and another large multicentre audit found that 60% of patients with dementia had an advance care plan. Reference Bryant, Sellars, Sinclair, Detering, Buck and Waller29 However, this population had an average age of 85 years and is not comparable to our population. Despite a more relevant age demographic, the available data from the USA on psychiatric advance directive uptake (reported at 4–13% and 7% from studies in 2003 and 2006) Reference Swanson, Swartz, Ferron, Elbogen and Van Dorn3,Reference Swanson, Swartz, Hannon, Elbogen, Wagner and McCauley30 is outdated and may not reflect current practice accurately, particularly within the NHS.

Our findings are nonetheless encouraging and indicate a step in the right direction toward more shared decision-making in the care of patients with serious mental illness. Ongoing research and up-to-date audits conducted at other NHS Trusts will be necessary to get a more complete picture of the current practice and inform both local and national policy decisions.

Discussion of specific predictors found to be associated with the application of an advance directive

Ethnicity

Our results show that among patients within any other ethnic group (other than White, Black or Mixed race), there was a lower likelihood of completion of advance directive compared with White patients. Factors likely to have an impact are cultural beliefs, language barriers, concerns about stigma, lower mental health literacy and the resulting challenges to accessing services. Reference Memon, Taylor, Mohebati, Sundin, Cooper and Scanlon31–Reference Torres Stone, Cardemil, Keefe, Bik, Dyer and Clark36 Given previous reports in the literature, our findings are as expected and highlight the need for improved efforts to engage ethnic minority groups in advance care planning.

In stark contrast, our findings show that there was a 30% higher likelihood of having an advance directive among patients of Black or Black British ethnicity compared with White patients. Black patients experience the same difficulties that hinder ethnic minorities engaging with mental health services. Moreover, Black patients are more likely to be admitted under compulsory detention, have higher rates of in-patient admission and tend to access mental health services through crisis care pathways. Reference Weich, McBride, Twigg, Duncan, Keown and Crepaz-Keay37–Reference Babatunde, Ruck Keene, Simpson, Gilbert, Stephenson and Chua42 Additionally, Black Caribbean patients have reported feeling disempowered during the treatment process and had lesser experiences of shared decision-making than was reported by their White counterparts. Reference Bhui, Stansfeld, Hull, Priebe, Mole and Feder39

Research has suggested that there is a higher demand for psychiatric advance directives among groups that experience disempowerment. Reference Swanson, Swartz, Ferron, Elbogen and Van Dorn3 A sense of loss of autonomy could mean that there is reduced completion of psychiatric advance directives despite the demand, but no meaningful correlation was found. Considering the challenging circumstances under which Black patients navigate the mental health system, it could be reasonably expected that they experience disenfranchisement and therefore lower engagement with advance care planning. However, it is possible that, paradoxically, these very circumstances are contributing to an increased uptake of psychiatric advance directives among this population as a means of gaining more control over their treatment.

Another factor to be considered here is that ELFT has a notably high representation of Black and minority ethnic staff, comprising 51.9% of the workforce, compared with only 25.7% in the NHS workforce. 43,Reference Carter44 Research suggests that patients are more likely to develop a better relationship with clinicians of the same ethnic background because of a shared cultural understanding, and are generally more satisfied with their care. Reference Moore, Coates, Watson, de Heer, McLeod and Prudhomme45 Clinician facilitation has been consistently found to be important to the successful completion of psychiatric advance care plans. Reference Philip, Chandran, Stezin, Viswanathaiah, Gowda and Moirangthem13,Reference Lenagh-Glue, Thom, O’Brien, Potiki, Casey and Dawson14,Reference Juliá-Sanchis, García-Sanjuan, Zaragoza-Martí and Cabañero-Martínez16,Reference Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen, Van Dorn, Ferron and Wagner46 A higher proportion of Black and minority ethnic staff likely contributes to a more conducive partnership between patients and staff, which can promote both clinician facilitation of and patient engagement with psychiatric advance directives.

Further research needs to be done in other regions, and we also need qualitative research within this population group to corroborate and understand these findings.

Directorate and localities

Our study found that within the directorates Newham, forensic and Bedfordshire and Luton, a higher number of patients had an advance directive, and further exploration could reveal useful information for directorate management teams for service improvement, aiming to improve take up of advance directives.

It is worth noting that our findings indicate that patients within forensic services were approximately 13 times more likely to have an advance directive. A greater emphasis on relational security necessitating higher staffing ratios, improved continuity of care and better rapport between patients and staff might be contributing factors. Staff attitudes and structural factors within forensic services create an environment that promotes a more collaborative approach, with greater patient involvement in decision-making. These might be factors that significantly enhance engagement with psychiatric advance directives within forensic services. Reference Kennedy47–Reference Selvin, Almqvist, Kjellin and Schröder50

Housing status

This study found that patients living in socio-therapeutic settings are more likely to have an advance directive compared with individuals settled in more independent living conditions. This finding indicates that staff support and engagement may be a crucial factor in the completion of advance care plans among patients.

The study found no significant association between homelessness and the completion of an advance care plan, despite the known difficulties that homeless individuals face in engaging with mental health services. Reference Nordentoft, Knudsen, Jessen-Petersen, Krasnik, Saelan and Brodersen51–Reference O’Carroll and Wainwright53

Number of hospital admissions

Patients with ten or more hospital admissions were three times more likely to have an advance directive. Patients with high number of admissions would have had experiences of higher levels of pressure to engage with treatment or take medication, which has been found to be associated with an increased motivation to complete an advance care plan. Reference Swanson, Swartz, Ferron, Elbogen and Van Dorn3 Studies have found that patients see mental health advance care plans as a means to avoid detention, and can use these to make their wishes known in relation to in-patient admission. Reference Gowda, Noorthoorn, Lepping, Kumar, Nanjegowda and Math24,Reference Swanson, Swartz, Hannon, Elbogen, Wagner and McCauley30 As such, psychiatric advance care plans can be utilised by patients as a means to exercise control and communicate their views on their care, and it would make sense that patients with repeated in-patient admissions would be more likely to engage with them. Reference Gergel, Das, Owen, Stephenson, Rifkin and Hindley5,Reference Maître, Debien, Nicaise, Wyngaerden, Le Galudec and Genest18 Moreover, a subset of patients with high number of admissions are ‘frequent attenders’ in accident and emergency departments. For these, advance care planning may be initiated by frequent attender multidisciplinary teams. Patients may also use advance directives to request crisis admissions for early support. Qualitative research and further exploration of these varied and complex reasons behind the uptake of advance care plans among this group could provide useful insights.

ICD-10 diagnoses

Patients with a recorded diagnosis of personality disorder were more likely to have an advance care plan in this study. This finding corroborates previous research that found a higher demand for psychiatric advance care planning among patients with a history of self-harm and suicidal ideation. Reference Swanson, Swartz, Ferron, Elbogen and Van Dorn3 However, there is limited evidence to consider reasons for this finding and more qualitative research would be needed within this group.

Patients with diagnosed personality disorders, particularly those with emotionally unstable personality disorder, often feel stigmatised and dismissed in psychiatric settings. Reference Bradbury54–Reference Myers56 Advance directives are a tool that can help patients articulate their treatment preferences, giving them a sense of control over their mental healthcare. Reference Olsen57 Evidence also suggests that advance directives can reduce compulsory treatment by encouraging collaborative planning. Reference Thomas and Cahill58 As such, advance directives may be a way for patients with personality disorder to feel more empowered and less dismissed by mental health services, and more in control of their care.

Further research is furthermore needed to understand the implications of the negative association between not having a recorded ICD-10 code and having an advance directive. Possible explanations include the fact that these patients are in earlier stages of their illness, undergoing assessment, and advance care planning was yet to be considered.

DIALOG PROM and PREM scores

This study found that PROM and PREM scores were associated with the completion of advance directives. Considering the importance of clinician support and facilitation toward enabling completion of advance directives, it aligns with an expectation that that there is an association with patient experience of medication, practical support and meetings. Reference Gergel, Das, Owen, Stephenson, Rifkin and Hindley5,Reference Lenagh-Glue, Thom, O’Brien, Potiki, Casey and Dawson14,Reference Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen, Van Dorn, Ferron and Wagner46 However, the differences between the mean scores of both groups for both measures are very small, and might not bear much significance in practice.

Patients who engaged with the DIALOG assessment tool were over 2.5 times more likely to have an advance directive in place, and this appears to be an important finding with clinical relevance. The DIALOG assessment and corresponding intervention (DIALOG +) is a tool that aims to facilitate structured communication between patients and clinicians to support dialogue about important aspects of life and healthcare experience. Reference Priebe, McCabe, Bullenkamp, Hansson, Lauber and Martinez-Leal59 As part of the care planning process, care providers go through the DIALOG scale questionnaire with patients at regular intervals. Reference Mosler, Priebe and Bird60 Research suggests that patients are more likely to complete psychiatric advance care plans if they receive support from someone during their treatment journey, Reference Philip, Chandran, Stezin, Viswanathaiah, Gowda and Moirangthem13,Reference Lenagh-Glue, Thom, O’Brien, Potiki, Casey and Dawson14 and staff efforts to engage patients in completing DIALOG may instil a sense of feeling supported. Structured communication with the aim of understanding patient perspectives could support engagement in advance care planning with staff. However, further research is needed to understand this association, preferably with qualitative research of patients and staff.

For some patients, advance care planning may be a way to assert personal healthcare wishes and retain control within their care trajectory amid coercive practices and systemic barriers. Psychiatric advance directives are a valuable tool for healthcare professionals to support patients with shared decision-making about their care and, for patients with severe mental illness, they promote empowerment and shared decision-making for care planning. Regardless, staff support is an important facilitator to completion, and structured communication and stronger therapeutic relationships, as well as an established co-production service culture, are likely to encourage advance care planning.

To understand the utility and implications of psychiatric advance directives in practice, a national audit initiative to adequately record and monitor the uptake of psychiatric advance directives according to standardised definitions could inform further research in this area. Moving forward, qualitative research is required to involve patient, carer and professional perspectives to better understand individual and systemic factors influencing the completion of advance care plans; this should evaluate the content of psychiatric advance directives, the quality of co-production and the impact on recovery. In addition, focused research studies in ethnic minority groups and specialist services like forensic services are needed.

Limitations

This study has included a large population size in a broad age range; however, it has several limitations. The primary method of analysis was secondary retrospective data analysis, which may have resulted in inaccuracies or incomplete data. There are inevitable variations in documentation practices across various localities and services, which may affect the reliability of the findings. A significant proportion of the data was missing. Despite our attempt at addressing this with multiple imputation, there is still a likelihood of biases introduced owing to missing data. The results should also be interpreted in light of the possibility of non-response bias because of the sizeable proportion of missing DIALOG responses. Grouping of values for analysis may have resulted in the loss of subtle nuances, potentially leading to an oversimplification of the data.

In this study, the outcome of interest is the presence of an advance directive. However, the study does not consider the nature or content of the recorded advance directives. In comparing the study’s findings against existing research, terms such as ‘psychiatric advance directives’, ‘advance statements’ and ‘joint crisis plans’ were treated synonymously, despite potential conceptual and practical differences. Without information about the content, it is unclear if they truly reflect patient-led directives or are staff-led care plans with varying levels of patient involvement. This ambiguity limits interpretability and should be considered when evaluating the findings.

About the authors

Immanuel Amrita Rhema, MBChB, MRCPsych, is a Higher Trainee Doctor in General Adult Psychiatry with East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Mohamed Ibrahim, MBBS, MRCPsych, is a Higher Trainee Doctor in General Adult Psychiatry with East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Hajara Begum is a Quality Assurance Service User Lead with East London Foundation NHS Trust, London, UK. Paul Binfield is the Director of People Participation with East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Doris McMeel is a Project Facilitator at East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Sophia Parveen is a Lived Experience Expert with People Participation at East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Lara O’Connell is the Senior People Participation Lead at East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Frank Röhricht, MD FRCPsych, is a Consultant Psychiatrist and Medical Director at East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; and Honorary Professor of Psychiatry at the Department of Psychiatry, Queen Mary University London, London, UK.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2025.10172.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author, I.A.R., on reasonable request.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to study design and manuscript writing. H.B., P.B., S.P. and L.O. provided expert lived experience advice. I.A.R. and M.I. conducted the statistical analyses. All co-authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no grant from any funding agency.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.