Introduction

To judge from polls, citizens are deeply concerned about lobbying. They share a profound and widespread belief that politicians and lobbyists are unethical. A recent Eurobarometer report revealed that 79 per cent of Europeans agree that overly close links between business and politics in their country has led to corruption and more than half believe that the only way to succeed in business is through political connections.Footnote 1 This reflects an understanding of politics wherein wealthy lobby groups ‘buy’ political influence, similar to buying a car from an expensive dealership (Grossman & Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman1994). Many political insiders (and most lobbyists), by contrast, tend to emphasize the beneficial effects of interest group engagement in democratic decision making. They argue that the interactions between lobbyists and politicians are part of a deliberative process in which concerns of citizens and other stakeholders find their way to the decision‐making process through argumentation and an exchange of ideas (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018). Interest groups then function as guardians of the people and ensure that politicians respond to pressing societal demands. From this perspective, public congruence is a key attribute for interest groups seeking to influence public policy.

The fundamental question underlying these debates is whether congruence with public opinion or the economic resources invested in lobbying are more important for policy influence. Separately, both perspectives have found much resonance in the literature. Much of the early work on lobbying influence in the United States focused on the impact of economic resources on public policy (see Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1971; Grossman & Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman1994; Mahoney & Baumgartner, Reference Mahoney and Baumgartner2015; McKay, Reference McKay2012; Smith, Reference Smith1999). On the one hand, these arguments gained traction in more recent studies looking at interest group success in Europe and the United States (Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015; Eising, Reference Eising2007; Hall & Deardorff, Reference Hall and Deardorff2006; Thrall, Reference Thrall2006). On the other hand, we have recently witnessed a wave of studies focusing on how interest groups articulate public preferences to politicians (Bevan & Rasmussen, Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2020; Giger & Klüver, Reference Giger and Klüver2016; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018, p.112; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Lowery, Fellowes and McAtee2004; Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Klüver and Pickup2018). Both strands of literature have been key in our understanding of lobbying influence, but studies combining both public congruence and economic resources into one explanatory framework remain largely absent. As a result, we do not know which perspective more accurately depicts patterns of interest group influence. This paper takes a first step in addressing this lacuna by providing an argument about how public congruence and economic resources relate to each other and conjointly affect an interest group's chances of influencing public policy. We propose that policymakers prioritize exchanges with resourceful interest groups, because these groups are better equipped to produce and communicate valuable expertise (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2019; Stevens & De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020). Yet, we expect that policymakers will further filter out the expertise provided by interest groups that also have public opinion on their side. Moreover, interest organizations which enjoy broad public approval, but have limited resources, will not be able to leverage this political advantage because they lack the capacity to transpose congruence with public opinion into a credible and salient signal of political pressure. Hence, interest groups are more likely to be influential if they have both economic resources and public opinion on their side.

For our empirical analysis, we draw from a sample of 41 policy issues for which public opinion polls were conducted in the European Union (EU), with extensive content analysis of 2,085 news media articles and 183 lobbyists’ survey responses. Our article proceeds as follows. First, we briefly summarize the academic debate on lobbyists’ role in the political process and outline our theoretical framework. Second, we develop our main argument on how public congruence and economic resources conjointly affect policy influence. In The Argument and Research Design sections we present our research design and empirical findings, respectively. We conclude with an overview of our main results and reflect on potential pathways for future research.

What explains influence? Transaction versus transmission

In line with Dür and De Bièvre (Reference Dür and De Bièvre2007, p.3), we conceptualize influence as ‘control over policy outputs’. We thus consider interest groups as influential if they manage to influence policy decisions in a desired direction. We conceive of popular support as ‘congruence’, or the degree to which the general public is aligned with an interest group's position on a particular policy (Flöthe & Rasmussen, Reference Flöthe and Rasmussen2019; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018; Willems & De Bruycker, Reference Willems and De Bruycker2021). Economic resources in the context of interest groups refer to the combination of financial and human resources that they can use to influence policy making. This can be measured by factors such as the number of full‐time employees and the amount of funds available for lobbying purposes (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2019, p.163). The role of economic resources, and public congruence for lobbying influence and power more broadly, have long been debated in the political science discipline. The next two sections provide a brief overview.

The transaction perspective

The importance of economic resources for lobby influence has a long tradition. In this view, lobbying is seen as part of a transaction where policy influence is ultimately sold to the highest bidder. As Lowery notes ‘In its most extreme versions, organized interests are assumed to act like shoppers in a grocery store, interacting hardly at all while lining‐up to sequentially and with certainty purchasing goods even until the store's shelves are bare. As a result, the transactions perspective viewed organized interests as pervasive threats to democratic governance’ (Reference Lowery2007, p.32). Whether or not the economic resources that interest groups possess are decisive for policy influence has been a central concern of political scientists. On the one hand, several studies link interest groups’ resources to the influence they gain in politics. This is most apparent in the United States. In their influential article with the telling title ‘Protection for Sale’, Grossman and Helpman (Reference Grossman and Helpman1994) develop a model which directly ties campaign contributions to political influence in trade policy. This model has influenced a wave of studies highlighting the importance of economic resources for political influence (e.g. Grether et al., Reference Grether, De Melo and Olarreaga2001; McCalman, Reference McCalman2004; Eicher & Osang, Reference Eicher and Osang2002; Mitra et al., Reference Mitra, Thomakos and Ulubaşoğlu2002; Matschke & Sherlund, Reference Matschke and Sherlund2006; Ederington & Minier, Reference Ederington and Minier2008).

Yet, there is also an important strand of literature downplaying the importance of economic resources for influence. In the United States, three studies stand out. First, Smith (Reference Smith1999, Reference Smith2000) examined 2,364 stands the Chamber of Commerce took on political issues over a 40‐year time span. He finds the Chamber of Commerce was not very effective at achieving its policy goals in US politics, despite being one of the most resource‐rich lobby organizations in the United States. Second, Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009) examined the impact of interest groups on 98 cases of Congressional policy making. They find a robust, yet rather small effect of the financial expenditures on lobbying and the success they have in influencing political decision making (see also Drope & Hansen, Reference Drope and Hansen2004 and Mahoney & Baumgartner, Reference Mahoney and Baumgartner2015 for similar findings). Third, McKay (Reference McKay2012), based on an extensive survey of 776 lobbyists, finds that there is no significant relation between resources that groups spend on lobbying and the preferences groups see attained in political decision making.

In the European context the link between economic endowment and influence is far less clear, mostly because studies have focused on the differences between interest group types rather than organizational capacities (see for instance Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015). This is perhaps caused by the more ambiguous role of money in European politics. In contrast to the United States, donations to politicians are severely limited. Money is used to develop more elaborate expertise and strategies instead of directly subsidizing a candidate's campaign. Several studies in Europe took up economic resources as a control variable in the analysis and find mixed results. For instance, Klüver (Reference Klüver2013), Junk (Reference Junk2019) and De Bruycker (Reference De Bruycker2019) all find no robust link between economic resources and lobby success. A recent study by Stevens and De Bruycker (Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020), however, suggests that economic resources can strengthen influence, but only when issues are of low salience in the news media. In short, the effect of money on influence in both the United States and European contexts remains unclear or contingent at best.

The transmission perspective

The second perspective is closely linked to the pluralist view and conceives of interest groups as transmission belts between the public and politicians (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Hanegraaff and Braun2017; Lowery, Reference Lowery2007; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018). As such, this transmission perspective has a more optimistic outlook on the role of interest groups in democratic systems: Interest groups are not bargaining with policymakers over who gets what, when and how, but instead are aggregating and transmitting the views of their constituents to policymakers (Flöthe & Rasmussen, Reference Flöthe and Rasmussen2019; De Bruycker & Rasmussen, Reference De Bruycker and Rasmussen2021). The key question underlying this transmission perspective is whether politicians, through the intermediating effect of interest groups, act more in line with public opinion or whether interest groups (mainly) push politicians away from the will of the people. So far, the results are again quite mixed. In the most extensive study carried out in the US context to date, Gilens and Page (Reference Gilens and Page2014) find no link between public opinion, via interest group involvement, to policy making in US politics. While they find a significant link between public opinion and policy output, this effect disappears once interest groups are added to the equation. This strongly suggests that interest groups steer policymakers away from what the general public wants. Bevan and Rasmussen (Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2020) are less skeptical, as they find that the number of voluntary associations in a policy area has a positive conditioning effect on the link between public priorities and attention for them in the President's State of the Union Address. Yet, they add that this congruence disappears in later stages of the legislative cycle. In its most positive outlook, we could interpret this as an indication that interest groups signal public grievances quite well, but this does not seem to translate into legislation.

In a European context, the scarce research results on the topic find a link between public opinion, interest groups and policymakers. Based on 118 Swiss public referenda, Giger and Klüver (Reference Giger and Klüver2016) show that legislators who have strong ties with sectional groups are significantly more likely to deviate from the preferences of their voters, whereas links with cause groups increase the congruence between what voters want and what their representatives do. In what we consider as the most extensive analysis of the link between influence and public opinion, Rasmussen et al. (Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018, p. 159) find that diffuse interests ‘benefit from the support of public opinion in attaining their preferences’. Yet, public congruence does not affect preference attainment for business groups. In short, it seems that in the European context the pluralist ideal of interest groups as transmission belts between citizens and policymakers is more valid than in the US context.

The interplay between public congruence and economic resources

Our article integrates the transaction and transmission perspectives into one explanatory framework to analyze how public congruence and economic resources work together and conjointly affect an interest group's chances of influencing public policy. Importantly, our argument builds on three assumptions. First, we assume that the congruence that an interest group enjoys is not necessarily a commodity in a quid pro quo, but rather a selection criterion that policymakers use to single out interest groups to transact or exchange expertise with. That is, we focus in this paper on issues for which public opinion polls exist and therefore policymakers can know, to a certain extent, what the public wants. Here, congruence is not part of an interest group's capacity to transmit information about public opinion, but rather a signal of their ability to supply politically opportune and legitimate expertise. Second, we assume that economic resources are required to operationally transmit opposition and support for policy initiatives and successfully pressure policymakers. Through high profile ‘outside’ lobbying campaigns and a strong prominence in new(s) media debates, interest groups can leverage public congruence and more easily pressure policymakers for influence. Third, we do not see resources and public opinion as strictly exogenous. In some cases, organizations may mobilize resources to sway public opinion into a preferred direction. In what follows, we further explain our analytical model and present our hypotheses.

First, economic resources are key for interest groups to engage in successful transactions with policymakers. An interest group will obviously not transfer economic resources to a policymaker's bank account. Rather, economic resources will be spent on staff costs, rent, consultancy and advocacy material (e.g., amendment proposals, policy briefs, research reports, etc.), hence, in developing and communicating critical expertise. As previous research shows, interest groups with more economic resources have more and better expertise to offer (Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2019). While economic resources may not be the actual commodity offered by interest groups, the expertise that result from these resources are all the more valuable to policymakers (McKay, Reference McKay2012). Such input greatly simplifies policymakers’ daily activities (e.g., drafting and amending policy proposals, preparing parliamentary questions, rebuttals, etc.), and saves them scarce time and resources. Moreover, a large number of studies have shown that economic resources and expertise are crucial to getting a foot in the door and directly accessing policymakers (e.g. Rasmussen & Gross, Reference Rasmussen and Gross2015; Persson & Edholm, Reference Persson and Edholm2018).

Second, interest groups may adopt a more antagonistic approach and aim to transmit political pressure on behalf of their constituents by signaling their opposition or support (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). Yet, mobilizing and coordinating protest events, producing politically valuable insights or developing tailored and media‐savvy advocacy material that generate media exposure, all require financial means and specialist staff (Danielian & Page, Reference Danielian and Page1994; Thrall, Reference Thrall2006). In short, interest groups need resources as a stepping‐stone to produce and effectively convey political pressure and expertise. This is why we consider economic resources and, more specifically, its resulting staff expertise as a key commodity for securing influence. We hypothesize:

H1: Resource‐rich interest groups have a higher chance of influencing policy outcomes.

Not only economic resources but also congruence with public opinion makes interest groups more likely to attain their preferences (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018). While empirical research substantiates this claim, especially in a European context, the question remains whether public congruence also enhances the influence of individual organizations in shaping policy outcomes. We argue that congruence with public opinion is certainly helpful for securing influence, but not necessarily in its own right. First, high levels of congruence provide interest groups with a momentum to convey their expertise. Policymakers require expertise and policy input to make informed decisions, but they also strive to respond to the broader public to maintain legitimacy, enhance their reputation and secure their re‐election. Consequently, policymakers are more likely to be receptive to an interest group's expertise when the group is perceived as representing a widely supported stance.

Second, interest groups aiming to influence policy making through pressurizing tactics stand on firmer ground if the public is on their side (Kollman, Reference Kollman1998). Yet, the size and nature of this competitive advantage will depend on how interest groups use congruence. That is, without the required capacity to leverage public congruence through costly campaigns it is unlikely that interest groups will succeed in signaling a salient and credible signal of political pressure. Public congruence then serves as a ‘sieve’ that policymakers use to filter out the expertise and pressure from interest groups that is useful for developing politically viable and technically sound policy solutions. From this perspective, public congruence does not lead to influence in its own right. Rather, it will amplify or weaken the effect of pressure and expertise on influence.

A third potential route is that interest groups try to change public opinion to their advantage. Groups may try to increase the salience of policy issues (Agnone, Reference Agnone2007; Dür & Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014, p. 1213) or sway public opinion by promoting particular policy frames (Boräng & Naurin, Reference Boräng and Naurin2015; Dür, Reference Dür2019). Yet, doing so is usually a long term process and involves intensive media campaigning efforts which, as mentioned, requires considerable financial means (Crepaz et al., Reference Crepaz, Junk, Hanegraaff and Berkhout2022, p.76; Junk, Reference Junk2016; Thrall, Reference Thrall2006). Yet, even if an interest group manages to secure influence by swaying public opinion, this does not change our general expectation that public congruence does not affect influence directly, but rather facilitates pressure and expertise‐driven exchanges. As such, also in this alternative route, the importance of public opinion for influence should be contingent on the resources an organization has at its disposal.

All this leads us to expect that an organization's congruence with public opinion conditions the effect of the resources it possesses on influence. As such, while ‘a little help from the people’ certainly facilitates interest groups’ chances of success (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018), we expect that it is primarily wealthier interest groups that will benefit from the people's help in influencing policy decisions. The distinction between ‘success’ and ‘influence’ is critical here as the former allows for coincidence to be at play while the latter requires an intervention by the interest group. In our analytical framework such an intervention applies to the costly supply of expertise and pressure, but not necessarily to congruence. Only when interest groups actively shape public opinion can we then speak of influence, but as mentioned, we deem this as mostly incidental and still conditional upon economic affluence. Hence, we hypothesize:

H2: An interest group's public congruence has no direct effect on influencing policy outcomes.

H3: The more economic resources an interest group has, the more likely that greater public congruence will strengthen its influence on policy outcomes.

Research design

To test our hypotheses, we focus on the case of EU public policy. Depending on the hypothesis considered, the EU can be seen as unlikely or conducive to confirming our hypothesis. As regards the importance of economic resources (H1), the European Commission (EC) has the exclusive right to propose legislation and hence wields a strong control over the EU's agenda. Compared to executive bodies in other polities, the EC is much more technocratic and staffed with non‐elected officials (van der Veer, Reference van der Veer, Bertsou and Caramani2020). Lobbying the EC is, hence, strongly geared towards providing research, evidence‐based input and technical expertise, that is, the type of lobbying expenditures that require economic resources (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013; Flöthe, Reference Flöthe2019). With regard to the importance of public congruence (H2), EU policy making is generally more complex, opaque and further removed from citizens’ everyday experiences (Follesdal & Hix, Reference Follesdal and Hix2006). The EU executive has an ‘extremely’ technocratic style of engaging with European citizens and journalists (Rauh, Reference Rauh2022). Hence, it is arguably much easier for policymakers to disregard public opinion in Brussels than in a domestic European or US context in which policymakers are more directly accountable to their constituents (Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik2013). Hence, we see the EU as an unlikely context for public congruence to affect influence (H2) and to constrain the role of economic resources for interest group influence (H3).

The starting point for our project is a sample of 41 issues drawn from Eurobarometer polls for which the fieldwork was conducted between 1 January, 2012, and 31 December, 2014. We only included questions that were surveyed in all the EU member states, and that could be connected to a specific policy. In this study, an EU policy issue is operationalized as a specific policy topic for which the EU is at least partially competent. In addition, we only considered questions that pertained to the opinion of citizens in terms of agreement or disagreement about a specific policy (see Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018). All the sampled issues were in one way or the other subject to ongoing (at the time) decision‐making processes in the EU. For most issues in our analysis binding agreements or secondary legislation was proposed (e.g., directives or regulations), while other issues have been addressed in non‐binding negotiations or soft‐law only (e.g., announcements or resolutions). As an example, one of our issues involved the question of whether citizens agreed with or opposed the introduction of a financial transaction tax. The 41 selected issues vary with respect to crucial criteria, such as media salience, policy field, interest group scope and polarization (see Supporting Information Appendix for more information).

To identify relevant interest groups on the sampled set of issues, we conducted a large content analysis of news media sources. In a first step, the relevant media coverage in eight media outlets related to the sampled set of cases was assembled manually. In the Supporting Information Appendix, we discuss the studied media outlets, why we selected them and the conducted reliability tests in detail. Based on extensive keyword searches, 2,085 articles were identified. Once articles were mapped, the statements made by interest groups in these articles were archived and coded. A statement is a quote or paraphrase in the news that can be connected to a specific actor. In total, 1,715 statements from interest groups were identified. Based on this media analysis, we identified 449 interest groups active on our sampled cases.

After identifying the interest groups active on the sampled issues in the news media, we developed an online survey to approach them. The survey was sent out for each issue separately. Contact persons were lobbyists that made statements in the coded news stories or other relevant experts active in the organizations, identified via the organization's website or through desk research. In the survey, respondents could name other relevant organizations. This led us to identify an additional 239 relevant interest organizations that did not appear in the media. We contacted these in a second wave of the survey. In total, we approached 613 interest groupsFootnote 2 out of the 688 identified organizations, from which 183 experts completed the survey. The survey had a response rate of 30 per cent, which is comparable to other survey projects on EU interest group politics (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013; Dür & Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014). The experts questioned in the survey are public affairs specialists who worked on the policy issue in question. On average, our respondents self‐indicated to have an expertise level of 7.65 (S.E. = 1.87) on a scale ranging from 1 (no knowledge) to 10 (perfect knowledge).

All this resulted in a dataset with 688 interest groups active on the sampled set of issues. Our dependent variable, influence, is a notoriously difficult phenomenon to measure. In our project, we used a reputational measure of influence, also called ‘attributed influence’ (Heaney, Reference Heaney2014). More specifically, we asked the expert respondents to indicate which of the active interest groups were influential, that is, ‘able to significantly impact the EU's decision‐making process on this issue’. Respondents could also name their own organization as influential. We linked the attributed influence scores to the identified interest group population to establish our measure of influence. We combined the responses from all the consulted experts for each issue in a proportional index to arrive at an intersubjective assessment of lobbying influence. This measure captures the relative share of respondents who identified the organization as influential. Six organizations were dropped because no surveys were conducted for their issue, and hence no measure of attributed influence could be identified. Sixty per cent of all active interest groups were not identified as influential, that is, none of the experts indicated that these groups had an impact on the decision‐making process. The remaining 40 per cent receive influence scores ranging from 0.03 to 1, depending on the relative share of organizations that had indicated them to be influential. For instance, on the issue of ‘accessibility for disabled’ the European Disability Forum was identified by the seven consulted experts as influential and hence received an influence score of ‘1’. BusinessEurope, by contrast, was also active on the issue but none of the experts identified it as influential and hence it received an influence score of ‘0’.

We conceive of influence as ‘control over’ rather than ‘agreeing with’ policy outcomes (Dür & de Bièvre, Reference Dür and De Bièvre2007). This is why we avoid using the more common ‘preference attainment’ measure as a proxy for influence. While studies on preference attainment have greatly advanced studies on lobbying success, one downside of this measure is that it black‐boxes the behavioral interventions of interest groups. As a result, preference attainment may be due to exogenous factors rather than interest group activities alone (Dür, Reference Dür2008), which may lead to an overestimation of public congruence relative to economic wealth. This problem would persist if one would use a more sophisticated measure of preference attainment as developed by Dür et al. (Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015) or Klüver (Reference Klüver2013) as it does not take into account that policy outcomes may move toward an organization's preferred outcome because of coincidence or via the actions of other interest groups. In other words, preference attainment is less suitable when seeking to analyze the influence of individual interest groups. There are, however, also downsides to reputation‐based measures of influence. For instance, a common criticism on attributed influence is that it may be biased in favour of large and well‐known organizations (Dür, Reference Dür2008, p. 566) or it may be biased towards organizations which saw their preferences attained and were therefore considered influential. We however think that our approach does not suffer from such invalidations. First, our measure focused on influence reputation for specific policy issues, and we consulted highly informed policy experts. Second, as can be seen in the analysis section, business groups are not considered more influential than non‐governmental organizations (NGOs). If our measure had tapped into more generic and simplistic power perceptions, we would likely have found that ‘big business’ is influential (Dür, Reference Dür2008, p. 566). Third, we especially have no reasons to believe that the hypothesized interaction between resources and public congruence is amplified or weakened by our operationalization of influence. Fourth, we made sure to rely on the collection of respondents active on one policy issue to assess influence (see former point). Combined, we believe this is the most accurate assessment of organizational level influence on specific EU policies to test our hypotheses regarding the relative importance of public congruence and economic resources.

To measure the congruence with public opinion an interest group experienced on an issue, our first key independent variable, we matched its position on the issue as reported in the survey or media with the percentage of European citizens adopting the same position on that issue as indicated in the Eurobarometer opinion poll (see also Flöthe & Rasmussen, Reference Flöthe and Rasmussen2019)Footnote 3. When multiple Eurobarometer surveys were conducted on the issue, we took the one closest to the center of the time period under consideration (November 2013). While public opinion certainly evolved during the time period considered, these changes were rather limited (Mean change of −0.39%; S.D. = 2.90). The European Banking Federation (EBF), for instance, was opposed to further regulation of wages in the financial sector (Issue ID3). According to Eurobarometer (November 2013), this position was only supported by 12 per cent of European citizens, which represents the group's value on the public congruence variable. Note that, 155 organizations did not adopt a clear position in favour or against the issue and as a result no measure of public congruence could be identified for these organizations; they were therefore excluded from further analysis.

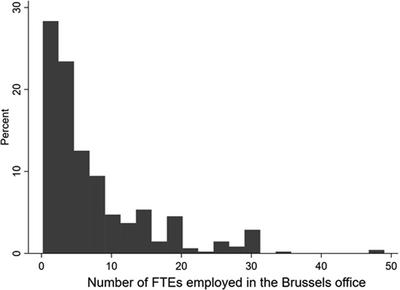

To measure our second key independent variable ‘economic resources’, we rely on the number of staff members (FTEs) who are employed by the organization in their Brussel's office, as indicated in the European Transparency Register (TR). We believe that the number of staff members effectively captures our presumed theoretical relationship, in which pressure or expertise are transformed into influence: Financial means are necessary to pay lobbyists’ salaries, but it are ultimately (paid) lobbyists who coordinate and develop campaigns to generate pressure and/or process and exchange expertise with policymakers. The number of staff members was coded by two student assistants. The overview of the responses is shown in Figure 1. We are aware that the register has faced reliability issues since its conception (Greenwood & Dreger, Reference Greenwood and Dreger2013), but in recent years it has become more consistent and the incentives of interest groups to offer accurate information has significantly increased due to intense monitoring by news media and NGOs (e.g., ALTER‐EU, Corporate Europe Observatory, Politico EU). To assess the reliability of this measure and our assumption that staff expertise is directly coupled with financial resources, we correlated the number of staff members in the Brussels office with the financial means spent on lobbying as indicated in the TR. Our measure of full‐time equivalents in the Brussels office strongly correlates (r = 0.7; P = 0.00) with the reported financial resources invested in lobbying in the TR. Moreover, the average reported change in FTEs between 2011 and 2015 as indicated in our survey is 0.45, which shows that organizational capacities in Brussels remained rather stable over the time period under consideration. Groups for which we could not identify the staff capacity of their Brussels office (n = 143) were excluded from further analysis. Importantly, we also did the same analyses with financial resources as a proxy for economic resources, which generated the same results (see Supporting Information Appendix).

Figure 1. FTEs working in the Brussels office.

We also considered a number of important control variables, both at the level of the individual organization as well as their engagement with the issue. First, the interest group literature sometimes confounds financial resources and public congruence with the type of interests represented (Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018). Therefore, we consider whether an interest group is a civil society organization (0) or a business group (1) in our analyses. Business or professional interest associations are membership organizations with firms or professionals as members, and civil society groups have individuals as members (directly or indirectly via lower level associations). Second, earlier research has demonstrated that influence can be explained by the policy position an interest organization adopts. Namely, those interests that seek policy change are less likely to achieve their goals (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009). Consequently, we control for whether an interest organization supported or opposed policy change. Third, to account for whether influence estimates were biased due to a participation in our expert surveys, we included (1) a dummy indicating whether the organization participated in the expert survey and (2) the number of experts that participated in the survey for each issue (μ = 11). Fourth, as our measures of influence reputation might be related to the breadth of policy areas in which an interest group is active, we controlled for the number of policy areas in which an organization is active as indicated in the TR. Fifth, we also took issue salience and issue polarization into account as both may affect the interplay between public congruence and economic resources. On salient issues, policymakers are likely to be aware of and take into account public opinion, while the role of economic resources diminishes (Stevens & De Bruycker, Reference Stevens and De Bruycker2020). On issues where public opinion is polarized, it is more difficult for policymakers to estimate public opinion which, in turn, can strengthen the role of economic resources. Hence, we estimate our models taking into account the salience and public polarization of policy issues. Salience was measured by taking the average number of articles that covered an issue across the eight news outlets that were scrutinized.Footnote 4 Issue polarization was measured by calculating the dispersion of positions adopted by public opinions on a policy issue (100‐|(% public opinion oppose ‐ % public opinion in favour)|). Higher values reflect relatively more equal proportions of the public in favour and against a policy initiative. Finally, as EU‐level organizations might have a stronger influence in Brussels compared to their national counterparts, due to their physical presence in Brussels and specialist focus on EU public affairs, we controlled for whether an organization has a national, EU‐wide or international constituency.

Results

In this section, we provide the descriptive and multivariate results of our analyses. Based on descriptive binary analyses between influence and public congruence, we find that groups that enjoy higher levels of public congruence also have a higher influence reputation. Both are positively and significantly correlated (Pearson's r = 0.19; P < 0.01). Groups that are aligned with a majority of the European public have an average influence score of 0.14, while for groups that were advocating a minority position this is only 0.08 (F = 7.99; P < 0.01). In addition, the number of FTEs that interest groups employ in their Brussels office is significantly and positively related to an organization's influence reputation (Pearson's r = 0.24; P < 0.01). The mean influence score for an interest group with 1 FTE is 0.03, while the influence score amounts to 0.42 for groups with 20 FTEs (F = 2.14; P < 0.01). Based on these binary descriptive data, both resources and public congruence seem to matter for influence, but the strength of their association is larger for economic resources. This indicates that interest groups’ economic resources carry a stronger weight than public congruence in influencing policy decisions. Moreover, economic resources seem to be unrelated to an interest group's public congruence as both variables are uncorrelated (Pearson's r = −0.02; P = 0.76). This bolsters our assumption that interest groups cannot easily change public congruence to their advantage, even if they have the economic means to set‐up large scale campaigns.

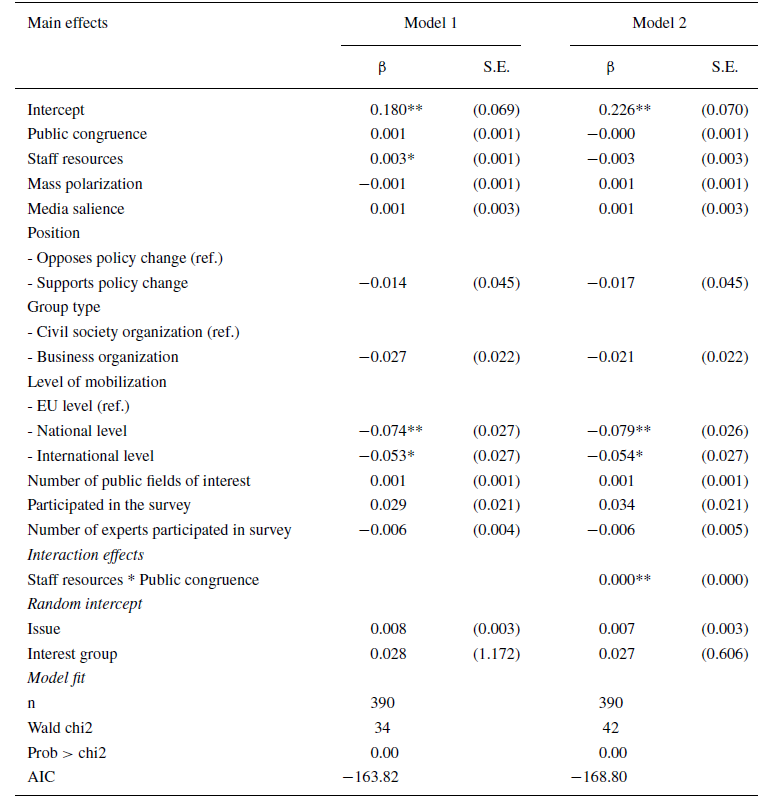

To test our hypotheses, we ran a mixed‐effects ordinary least squares regression with the influence reputation score as the dependent variable. One unit of analysis in the regression analysis constitutes an interest organization active on one of the sampled issues (group‐issue dyads). We only consider interest groups for which a position in favour or against an issue, as well as the staff resources, could be identified (n = 390). We included random intercepts for issues and interest groups to account for the nesting of interest groups in the sampled issues. Table A3 in the Supporting Information Appendix gives an overview of the descriptive values of the variables included in the regression model. Model 1 in Table 1 presents the main effects of our predictors on influence reputation and Model 2 presents the interaction effect with a multiplicative term for staff resources and public congruence. The interaction effect between public congruence and economic resources is crucial in testing our hypothesis on the contingent impact of public congruence on influence (H3).

Table 1. Mixed‐effects ordinary least squares regression of influence reputation

Significance levels indicated by †< 0.10 *< 0.05 **< 0.01

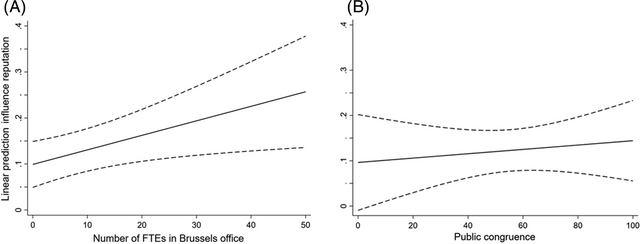

From the main effects in Model 1, we conclude that staff resources have a positive and significant effect on influence reputation, but congruence with public opinion does not. Hence, the results from our binary analyses do not fully hold true after controlling for potential confounders in the regression analysis. Also, when considering the effect of public congruence in a model excluding economic resources, it does not affect influence significantly (see Supporting Information Appendix). The analysis shows that staff resources are more critical than public congruence for influencing policy when both are included in one model. The main effects of staff resources on influence reputation are shown in Figure 2a. The figure shows that groups with limited resources (1 FTE) have a predicted influence reputation score of 10 per cent while for groups with very high levels of resource endowment (50 FTEs) the predicted influence score amounts to 25 per cent. Predicted influence scores are not significantly different across different levels of public congruence (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Predictive margins of (a) staff resources and (b) public congruence on influence reputation (based on Model 1).

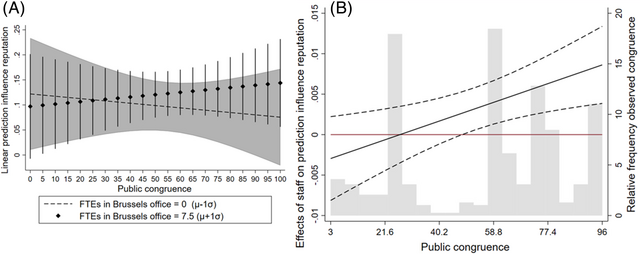

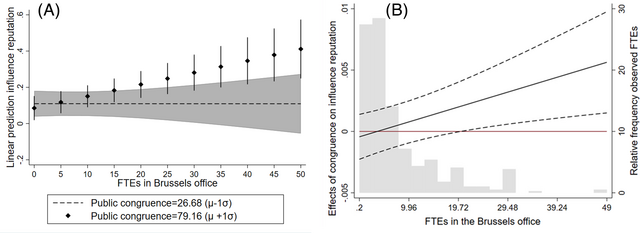

Model 2 shows whether and how public alignment and staff resources conjointly affect influence reputation by including an interaction term between these two variables. The coefficient of the interaction term is positive and significant, suggesting that the effects of economic resources and congruence with public opinion are contingent on one another. To properly interpret the interactive terms, we present predictive margins and average marginal effects in Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2a presents the predicted influence scores for groups with high (μ + 1σ) and low (μ ‐ 1σ) levels of staff resources for different levels of public congruence. Interestingly, the figure shows that for groups with greater financial capacities, the more public approval their position enjoys, the higher their influence scores. For groups with lower expenditures, public approval seems to have no or even a negative effect on the predicted influence scores. Figure 2b on the right‐hand side allows us to estimate whether the observed differences are statistically significant (Brambor et al., Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006). To properly interpret the interactive terms, we present average marginal effects in Figures 3 and 4 (Brambor et al., Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006). Figure 3b presents the average predicted change on the influence score for a one unit increase in the staff resources variable for different levels of public congruence. It shows that groups with more staff capacities are more influential, as long as the public congruence that they enjoy is not lower than 50 per cent.

Figure 3. Predictive margins (a) and average marginal effects (b) of economic resources on influence reputation for different levels of congruence with public opinion with 95 per cent CFIs. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 4. Predictive margins (a) and average marginal effects (b) of congruence with public opinion on influence reputation for different levels of economic endowment with 95 per cent CFIs. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 4a shows the predicted influence scores for groups with high (μ + 1σ) and low (μ ‐ 1σ) levels of public congruence for different levels of financial endowment. The figure illustrates that groups with low levels of public congruence do not seem to benefit from more economic resources, while groups with high levels of public congruence see their influence score increase the more lobbyists they employ. When looking at Figure 4b, we only see statistically significant differences for those groups with very high staff resources (more than 20 staff members). For a one percentage point increase in public congruence, we only see significant changes in the predicted influence score for groups with very high levels of staff resources. This confirms hypothesis 3, as it shows that only groups with vast economic resources benefit from congruence with public opinion. Resource‐rich interest groups see their chances of influencing policy outcomes increase the more they are aligned with public opinion. Resource‐poor interest groups, by contrast, do not have a higher chance of influencing policy outcomes if they defend more popular policy goals. Conversely, the results show that the effect of economic resources is also confined by public congruence. More specifically, Figure 3b indicates that employing one additional staff member only increases influence if the interest group agrees with at least 50 per cent of the European public.

We ran a battery of alternative models to assess the robustness of our findings, namely (1) a model with a binary operationalization of influence, (2) models with financial resources spent on lobbying as an alternative proxy for economic resources, (3) models with non‐attitudes as an additional measure of public salience, (4) models in which public congruence and economic resources are estimated separately, (5) models incorporating national public opinion data, (6) models including fixed effects for issues, and (7) models with bin estimators for staff resources and public congruence to test the linearity assumption for the continuous interaction between public congruence and economic resources (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019). The robustness checks support the validation of our hypotheses and can be found in the Supporting Information Appendix.

Also, the control variables yield some interesting results. First, we do not find significant differences between business groups and civil society organizations or between groups lobbying in favour or against a policy initiative. Second, EU‐level organizations are significantly more likely to be seen as influential compared to their national or international counterparts. This is not surprising given that EU‐level groups are often physically based in Brussels, better acquainted with the EU's political system and more specialized in EU policy dossiers. Third, interest groups that are active in more policy fields do not enjoy a significantly stronger influence reputation. Fourth, groups from which experts participated in our survey do not have a significantly stronger influence reputation. Moreover, when more experts were consulted on an issue, this does not significantly affect the influence reputation measure for an organization. Finally, our controls for the issue characteristics of media salience and mass polarization do not affect influence reputation.

Conclusion: A paradox of public congruence

This article examined the extent to which lobbying influence is determined by the highest bidder or boosted by congruence with public opinion. Theoretically, the paper argued that economic resources enable interest groups to cultivate expertise and exert pressure on policymakers. However, we posited that policymakers will be more receptive to the expertise and pressure conveyed by interest groups based on the groups’ degree of congruence with public opinion. Thus, while economic resources are a vital component for developing effective lobbying campaigns, congruence with public opinion acts as a criterion for policymakers to determine the relevance and credibility of input from interest groups. As a result, the paper argued that interest groups with greater economic resources are more likely to reap the benefits of aligning with public opinion, as they have the means to cultivate expertise and generate pressure on policymakers, while policymakers will also be more receptive to their input due to their congruence with public opinion.

Our study relied on a sample of 41 EU policy issues for which public opinion polls were conducted, with extensive content analysis of 2,085 news media articles and 183 lobbyists’ online survey responses. Our findings indicate that both public congruence and economic resources play a significant role in determining an interest group's influence, with their effects being intertwined. Specifically, we discovered that affluent interest groups benefit from being in line with public opinion, while resource‐limited organizations do not experience an increase in influence despite widespread public agreement with their position.

Our paper contributes to the literature on interest group influence (Bunea & Baumgartner, Reference Bunea and Baumgartner2014, p. 1431; Pritoni & Vicentini, Reference Pritoni and Vicentini2022; De Bruycker & Beyers, Reference De Bruycker and Beyers2019; Dür et al., Reference Dür, Bernhagen and Marshall2015). Our results highlight that resources matter considerably for interest group influence – something which has often been ignored in EU studies. In line with recent empirical findings, our study also confirms the importance of congruence with public opinion and further explored its contingent effects (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018; Willems & Beyers, Reference Willems and Beyers2022). However, our study has limitations and further research is necessary. Our analysis was limited to issues with available public opinion data, which makes it easier for policymakers to assess a group's alignment with public opinion. This limits the generalizability of our findings to issues where no public opinion data are available. We attempted to mitigate this by controlling for factors such as issue salience, public polarization and non‐attitudes in our models, but it does not fully address this concern. Further research, including targeted polls, is needed to examine the impact of public congruence and economic resources on interest groups' influence for issues where public opinion is unknown to policymakers.

Second, our study was conducted within the context of EU policy making, which may not be representative of other political systems. It would be valuable for future studies to test our findings in other contexts, such as the United States, national European contexts and non‐Western political systems. The role of economic resources may be more pronounced in the United States, where financial donations to political candidates are more common. On the other hand, public congruence may have a greater impact on influence in contexts where the executive can be held accountable by voters and where elections are more competitive and visible (Hanegraaff & De Bruycker, Reference Hanegraaff and De Bruycker2020; Gromping, Reference Gromping2019). This may not be the case in the EU, where citizens are more distant from policymakers and there is a lack of a conventional media space. Further research in various institutional settings is needed to fully understand the relationship between public congruence and economic resources on interest group influence.

Finally, our findings have important normative implications and suggest a paradox of public congruence. On the one hand, current research has long viewed the impact of public opinion on interest group lobbying as positive and desirable, with interest groups serving as a transmission belt between society and policy (Albareda, Reference Albareda2018; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018; Willems & De Bruycker, Reference Willems and De Bruycker2021). Our findings support this view by showing that interest groups with a high level of public congruence have a greater chance of affecting policy outcomes, even in a complex and technical EU policy context. Furthermore, our study finds that resource‐rich groups only see limited benefits from their financial resources if they do not have significant public support. On the other hand, our results raise questions about who benefits from public congruence. Our findings indicate that public congruence reinforces the power of wealthy interest groups while being inconsequential for resource‐poor organizations, supporting elitist claims of biased representation (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960). Ultimately, a pluralist paradise may indeed exist, but it is a luxurious destination reserved for interests with the financial means to reach it.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Adrià Albareda, Frank Baumgartner, Adriana Bunea, Michael Klitgaard, Garry Marks, Anne Rasmussen, and the four anonymous reviewers, for their invaluable comments and support. Additionally, we are grateful for the comments received from participants who provided feedback at the Comparative Agendas Project Annual Conference in Budapest (2019), the ECPR General Conference in Wrocław (2019), the European Union Studies Association Biennial Conference in Denver (2019), and the Politicologenetmaal in Antwerp (2019).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: