Anorexia nervosa is a severe and disabling mental illness that mainly affects adolescent females. It carries a considerable risk of a chronic course and the mortality rate in anorexia nervosa is among the highest of all mental disorders. Reference Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales and Nielsen1 The peak age of anorexia nervosa onset occurs in adolescence at a crucial stage in a young individual’s educational and psychosocial development. Reference van Eeden, van Hoeken and Hoek2 The disorder is associated with numerous somatic (e.g. cardiovascular problems, osteoporosis) Reference Fayssoil, Melchior and Hanachi3 and psychiatric comorbidities (e.g. depression, anxiety disorders). Reference Nickel, Maier, Endres, Joos, Maier and Tebartz van Elst4,Reference Marucci, Ragione, De Iaco, Mococci, Vicini and Guastamacchia5 Moreover, anorexia nervosa is linked to high costs for sufferers, carers and society in general. Reference Ágh, Kovács, Supina, Pawaskar, Herman and Vokó6–Reference Surgenor, Dhakal, Watterson, Lim, Kennedy and Bulik9 Hoeken and Hoek Reference van Hoeken and Hoek10 reviewed the recent literature on the burden of eating disorders and concluded that they have a negative impact on years lived with disability (YLD), quality of life, economic costs and childbearing. Compared with other disorders, eating disorders are more disabling than for example severe heart failure, but less so than schizophrenia as measured by disability weights. 11 Further, increasing YLD rates in eating disorders signal that the burden is growing in contrast to other mental disorders. 8,Reference van Hoeken and Hoek10 Several studies have reported increased healthcare utilisation in individuals with anorexia nervosa, including in- and out-patient care, and a higher rate of emergency visits compared with healthy controls. Reference Ágh, Kovács, Supina, Pawaskar, Herman and Vokó6,Reference Simon, Schmidt and Pilling7,Reference Mitchell, Myers, Crosby, ONeill, Carlisle and Gerlach12,Reference Striegel-Moore, DeBar, Wilson, Dickerson, Rosselli and Perrin13 Healthcare costs were found to be high around the time the eating disorder diagnosis was made and remained high during the following years. Reference Mitchell, Myers, Crosby, ONeill, Carlisle and Gerlach12 Striegel-Moore et al Reference Striegel-Moore, DeBar, Wilson, Dickerson, Rosselli and Perrin13 examined in- and out-patient utilisation in adults with anorexia nervosa and reported increased health service use both twelve months before and a year after diagnosis.

Studies evaluating ‘non-healthcare’ costs suggest that a history of anorexia nervosa may have a severe long-term impact on work life and educational achievement. Reference Hjern, Lindberg and Lindblad14–Reference Ratnasuriya, Eisler, Szmukler and Russell16 A large Swedish register study of former in-patients with anorexia nervosa reported lower employment rates and a subgroup of 21.4% who depended on benefits for their income. Reference Hjern, Lindberg and Lindblad14 In an 18-year follow-up study of a community-based sample of anorexia nervosa, 25% had no employment due to psychiatric morbidity. Reference Wentz, Gillberg, Anckarsäter, Gillberg and Råstam15 Follow-up studies on in-patients with anorexia nervosa reported that 50–71% were unemployed after about 20 years; Reference Ratnasuriya, Eisler, Szmukler and Russell16,Reference Löwe, Zipfel, Buchholz, Dupont, Reas and Herzog17 however, employment rates similar to those of controls have also been reported. Reference Mustelin, Raevuori, Bulik, Rissanen, Hoek and Kaprio18 Educational levels have been reported to be both comparable with and lower than among unaffected peers. Reference Mustelin, Raevuori, Bulik, Rissanen, Hoek and Kaprio18–Reference Maxwell, Thornton, Root, Pinheiro, Strober and Brandt20 The wide variability in reported employment outcomes can be attributed to key differences across long-term follow-up studies – such as sample selection, e.g. out-patients versus in-patients, community-based versus clinical cases and the age groups studied (adolescent-onset versus adult-onset cases). These methodological differences also contribute to inconsistent findings regarding predictors of outcomes in anorexia nervosa.

Taken together, previous research highlights a significant burden of anorexia nervosa; however, research examining the very long-term health economic impact of the disorder is limited. Furthermore, only a few studies have compared the burdens of disease between individuals with and without eating disorders. Reference van Hoeken and Hoek10 Since 1985, our research group has prospectively followed a group of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa cases recruited from the community together with a comparison group (the Gothenburg anorexia nervosa study). The overall aim of the present study was to examine the health economic burden of anorexia nervosa over a period of 30 years.

The specific aims were to explore whether middle-aged individuals with a history of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa differ from matched comparison cases regarding (a) utilisation of healthcare (in- and out-patient care) and medication, (b) amount of social assistance received and (c) days of sick leave and disability pension. An additional aim was to (d) identify early predictors of healthcare consumption in individuals with adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa.

Method

Participants

All participants were part of the so-called Gothenburg anorexia nervosa study, an epidemiological study of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa ongoing since the mid-1980s. The study was initiated by M.R and C.G. At the time of the study start, all 4291 individuals born in 1970 and living in Gothenburg, Sweden, were screened for anorexia nervosa. Twenty-four adolescents (22 girls and 2 boys) were diagnosed with the disorder and constituted a population-based group of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa. Another 27 adolescents with the disorder (26 girls and one boy), born in 1969 and in 1971–1977, were also detected at the time of screening and constituted a population screening group. Due to the similar group structure of the population-based group and the population screening group, the two groups were combined to form a group consisting of 51 individuals (48 females, 3 males), the anorexia nervosa group (for details see Reference Råstam21,Reference Råstam, Gillberg and Garton22 ). All participants in the anorexia nervosa group met the criteria for the disorder according to the DSM-III-R Reference Spitzer, Williams and American Psychiatric23 and DSM-IV 24 at recruitment.

A healthy comparison group (COMP group) with no history of eating disorders was recruited in collaboration with the school health nurses involved in the anorexia nervosa screening in Gothenburg. The comparison cases were matched for schooling, age and gender. Baseline data on social class were collected and indicated no differences in socioeconomic status between the anorexia nervosa and COMP groups.

The anorexia nervosa and COMP groups were examined on five occasions at mean ages of 16 (Study 1), 21 (Study 2), 24 (Study 3), 32 (Study 4) and 44 years (Study 5). Reference Wentz, Gillberg, Anckarsäter, Gillberg and Råstam15,Reference Råstam21,Reference Råstam, Gillberg and Garton22,Reference Dobrescu, Dinkler, Gillberg, Råstam, Gillberg and Wentz25–Reference Wentz, Gillberg, Gillberg and Rastam27 In Study 5, all 102 participants were traced (51 anorexia nervosa and 51 COMP). Four individuals in the anorexia nervosa group declined to participate (drop-out rate 4%), while all 51 individuals in the COMP group participated in Study 5. All participants were alive, 64% had full symptom recovery and 19% still met the criteria for an eating disorder diagnosis. Reference Dobrescu, Dinkler, Gillberg, Råstam, Gillberg and Wentz25 Full symptom recovery was defined according to Strober et al Reference Strober, Freemen and Morrell28 as ‘patients who have been free of all criterion symptoms of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa for not less than 8 consecutive weeks’. It requires the sustained absence of weight deviation, compensatory behaviours and deviant attitudes regarding weight and shape, including weight phobia. We also required the participants to be free from all criteria of a binge-eating disorder and that the individuals had been free from the above symptoms for at least 6 months. The examinations were performed from 2015 through 2016.

Assessments at Study 5

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI 6.0) Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller29 was used to assess current psychiatric disorders. In addition, the Eating Disorder section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) was administered. Reference First30 A checklist for DSM-5 eating disorders was included to gather additional information on eating disorder symptoms according to the DSM-5. 31 All participants were asked brief questions about their current living situation, marital status, education and employment. For details, see Dobrescu et al. Reference Dobrescu, Dinkler, Gillberg, Råstam, Gillberg and Wentz25

Data on the highest attained level of education was categorised into three groups: (a) up to elementary school (9 years), (b) up to secondary education (12 years) and (c) post-secondary education (>12 years). Employment was categorised into (a) full-time student, (b) work (full-time), (c) work 50–90%, (d) less than 50% work, (e) parental leave and (f) no employment.

National registers

The National Patient Register (NPR) stores data from 1964 and contains information on in- and out-patient care. Information regarding specialised out-patient visits were included in this register from 2001. The NPR gathers information on main and secondary diagnoses coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, eighth revision [ICD-8], 32 in use between 1968 and 1986; the International Classification of Disease, ninth revision [ICD-9] 33 in use between 1987 and 1996; and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, tenth revision [ICD-10], 34 in use since 1997. The validity of the NPR is high. Reference Ludvigsson, Andersson, Ekbom, Feychting, Kim and Reuterwall35 Days admitted to in-patient care and the number of out-patient visits were calculated based on data from the NPR. Admittances stored in the NPR are assigned a code for the admitting department (e.g. psychiatry, paediatrics). Using the admitting department code for the admission/healthcare visit, in-patient and out-patient care was classified into psychiatric or somatic. In addition, we separately examined admissions with a registered eating disorder diagnosis as the main diagnosis (including ICD codes ICD-8: 306.5; ICD-9: 307.1, 307B, 307F; and ICD-10: F50.0–F50.9).

The Swedish Prescribed Drug Register has been recording data since 2005 and contains all prescribed medicines classified according to the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification system (ATC). The drug register has almost complete coverage. Reference Wettermark, Hammar, Fored, Leimanis, Otterblad Olausson and Bergman36 The number of prescribed psychotropic medications (ATC codes N05 and N06) was collected.

The National Register of Social Assistance stores data on social assistance from 1990. Temporary financial support is granted to individuals in Sweden who are unable to support themselves or their children. Data were collected on the number of months that each individual had received social assistance.

The Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SIAS) administers the areas of social insurance that provide financial security in the event of illness and disability and for families with children. SIAS keeps registers with information on a variety of benefits within the social insurance system from 1998. Data on sick leave and disability pension were collected. Sick leave was defined as absence due to illness/disability>14 days, as the Swedish social insurance agency only stores information about sick leave from day 15. To receive government sick leave payments, an individual must have been at least partially employed during the preceding year. All individuals aged 19–64 years and living in Sweden can be granted a disability pension if their work capacity has been permanently reduced due to disease or injury. To receive a disability pension in Sweden, an individual’s work capacity must be expected to be reduced by at least 25% for at least one year. The net number of days with sick leave and/or disability pension was calculated.

Regarding all registers used, we had access to data until 31 December 2015.

Early predictors of healthcare consumption

The early predictors focused mainly on variables assessed in Study 1 Reference Råstam21,Reference Råstam, Gillberg and Garton22 and on premorbid/retrospective childhood data. The early predictors examined were: age at anorexia nervosa onset, lowest z-BMI during the first episode of anorexia nervosa, premorbid social class, premorbid perfectionism, autism (ASD) or obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) in Study 1. A structured parental interview of the early development of the child was performed in Study 1 and a semi-structured parental interview as well as a clinical psychiatric examination of the child was conducted to assess personality disorders. Based on de-identified case notes regarding the premorbid history of the participants, a psychiatrist blind to group status (C.G.) assigned the personality disorder diagnoses and relevant personality traits, e.g. premorbid perfectionism. No validated instrument was used to assess premorbid perfectionism as no such instrument existed at the time of the original study, in the 1980s.

Ethical approval

The procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. Ethical approval for the project was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board at the University of Gothenburg (398-14). An amendment regarding additional data collection from the SIAS was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority in 2023 (2023-03127-02). Ethical approval was obtained for each of the five assessments over the 30-year period and included permission to collect registry data for all participants across the same timeframe.

Statistical analysis

For comparisons between groups, mainly non-parametric tests were used, as the scale scores were not normally distributed, and the group sizes were relatively small. The chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used for dichotomous variables and the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables. All tests were two-tailed and conducted at a significance level of 0.05.

Predictive factors

The variables analysed as predictors of healthcare consumption were: age at anorexia nervosa onset, lowest z-BMI during the first episode of anorexia nervosa, premorbid social class, premorbid perfectionism and ASD or OCPD in Study 1.

For binary outcomes (ever admitted to psychiatric in-patient care, ever visited psychiatric out-patient care, ever received disability pension or ever prescribed psychotropic medication), logistic regression was used in both univariable and multivariable analyses. Results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Discriminatory performance was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). In the multivariable models, variable importance was assessed using the Shapley decomposition of Tjur’s coefficient of discrimination. Tjur’s discrimination index quantifies a model’s ability to distinguish between outcome groups (e.g. admitted versus not admitted to psychiatric care) by calculating the mean difference in predicted probabilities between those groups. The model’s total discriminatory performance was then partitioned across individual predictors using Shapley values, which equitably attribute each predictor’s contribution by averaging over all possible predictor orderings. The resulting relative importance values were re-scaled to sum to 1 (or 100%), providing an interpretable measure of each variable’s contribution to the model’s overall performance.

For discrete count variables (days in psychiatric in-patient care, days in somatic in-patient care, visits to somatic out-patient care, days of disability pension, days of sick leave and prescriptions of psychotropic medication), log-linear quasi-Poisson regression was used in both univariable and multivariable analysis. Overdispersion and heteroscedasticity were addressed through quasi-likelihood estimation and a robust s.e. (HC3 method), ensuring valid inference despite potential violations of standard Poisson model assumptions. Results are presented as fold changes with 95% confidence intervals, representing the multiplicative change in expected outcome counts per one-unit increase in the predictor.

Correlations between healthcare utilisation outcomes and predictors were performed using Spearman correlation coefficients.

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0 for macOS (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA; see https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics); SAS/STAT version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA; see https://www.sas.com/); and R version 4.4.1 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; see https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/), with variable importance using the domir R package version 1.2.0 (see https://cran.r-project.org/web//packages/domir/index.html).

Individuals who had emigrated

A small number of individuals emigrated in young adulthood (anorexia nervosa n = 3; COMP n = 2) and another group of individuals were living abroad at the time of the 30-year follow-up (anorexia nervosa n = 3; COMP n = 7). As register-based data were not available for periods spent abroad, these individuals were retained in the analyses and were assumed to have zero healthcare consumption and social welfare receipt during the time they resided outside Sweden.

Results

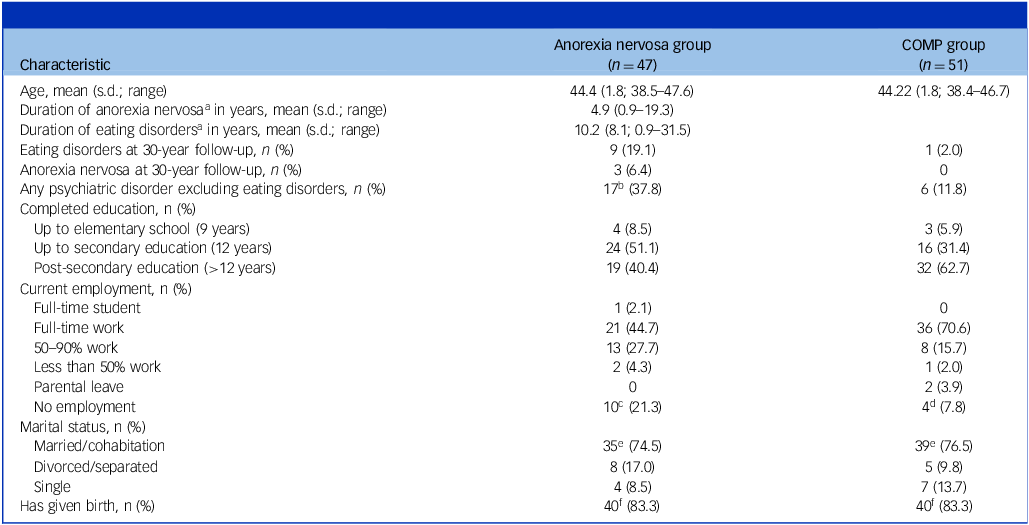

The clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics in the anorexia nervosa and COMP groups at the 30-year follow-up

COMP, Comparison.

a. Including several episodes during a follow-up period of 30 years.

b. Based on 45 individuals in the anorexia nervosa group.

c. Sick-leave or disability pension (n = 8), unemployed/applying for jobs (n = 2).

d. Sick-leave or disability pension (n = 2); housewife (n = 1); unemployed/jobseeker (n = 1).

e. One individual had a partner but was not cohabiting.

f. Based on 48 females in the anorexia nervosa and COMP group, respectively.

Healthcare utilisation

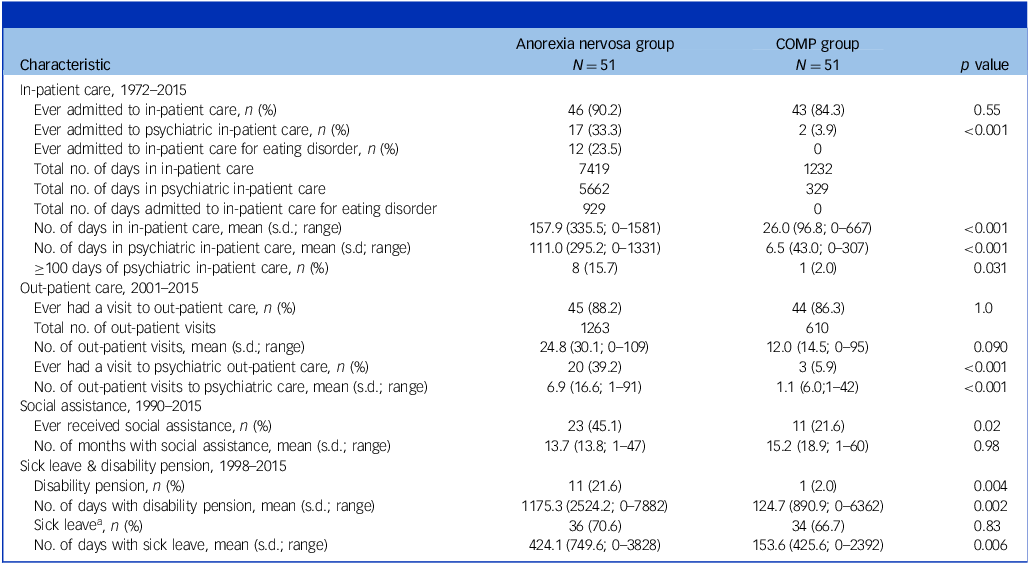

The anorexia nervosa group had a mean number of days in in-patient care of 157.9 (s.d. 335.5) compared with 26.0 (s.d. 96.8) days in the COMP group (p < 0.001). The mean number of days in psychiatric in-patient care in the anorexia nervosa group was 111.0 (s.d. 295.2) compared with 6.5 (s.d. 43.0) in the COMP group (p < 0.001). The anorexia nervosa group had more visits to psychiatric out-patient care (mean: 6.9 (s.d. 16.6)) than controls (mean: 1.1 (s.d. 6.0); p < 0.001) (Table 2). Over the 30-year period, 33% of the individuals in the anorexia nervosa group, compared with 3.9% in the COMP group, had been admitted to psychiatric in-patient care (p <0 .001) (Table 2). The long-term pattern of in-patient care consumption (year: 1972–2015) in the anorexia nervosa and COMP groups is illustrated in Fig. 1. The pattern shows a peak of in-patient care utilisation around time of anorexia nervosa onset and the following years (1986–1993). At later age (year: 2004–2008) a less prominent increase in psychiatric in-patient care consumption could be observed in the anorexia nervosa group.

Fig. 1 Days of in-patient care on a timeline from 1972 to 2015, in the anorexia nervosa and COMP groups. The number of days per two years (e.g. 1972–1973) for psychiatric and somatic care, respectively, are displayed. COMP, Comparison.

Table 2 Utilisation of healthcare, medication, social assistance and sick leave and disability pension in the anorexia nervosa and COMP groups

COMP, Comparison.

a. Absence due to illness/disability >14 days.

Medications prescribed

The anorexia nervosa group had a mean number of 78.9 (s.d. 257.8) prescriptions of psychotropic medication compared with 6.4 (s.d. 25.6) in the COMP group (p = 0.045). Forty-three per cent in the anorexia nervosa group compared with 31% in the COMP group were ever prescribed psychotropic medication, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.31). The most frequently prescribed group of pharmaceuticals in the anorexia nervosa group was psycholeptic drugs (e.g. anxiolytics) followed by psychoanaleptic drugs (e.g. antidepressants) (Table S1).

Sick leave and disability pension

The anorexia nervosa group had a mean number of 424.1 (s.d. 749.6) days of sick leave compared with 153.6 (s.d. 425.6) in the COMP group (p = 0.006). The mean number of days with disability pension in the anorexia nervosa group was 1175.3 (s.d. 2524.2) compared with 124.7 (s.d. 890.9) in the COMP group (p = 0.002) during the study period (Table 2).

Social assistance

More individuals in the anorexia nervosa group compared with the COMP group had received social assistance at some point during the 30-year period (anorexia nervosa: 45%; COMP: 22%); p = 0.02). The mean number of months with social assistance was equally distributed across groups (p = 0.98) (Table 2).

Predictors of healthcare consumption

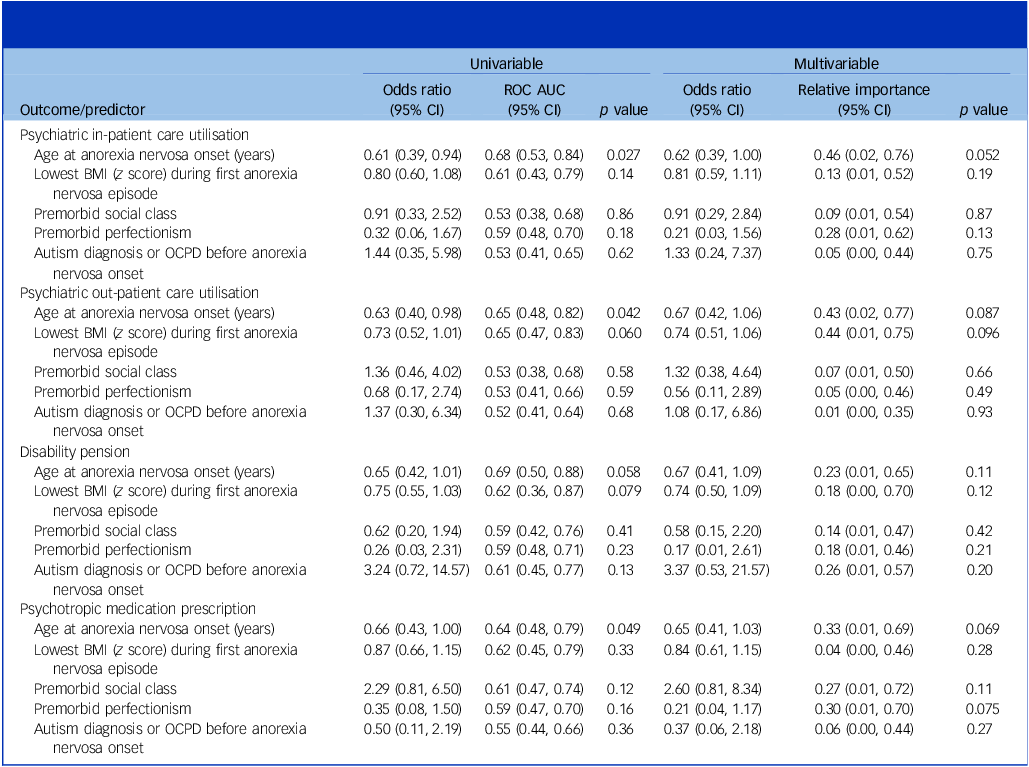

The univariable analysis for binary outcomes showed that age at anorexia nervosa onset was statistically associated with psychiatric in-patient care (odds ratio 0.61 per one-year increase, 95% CI: 0.39–0.94, p = 0.027), psychiatric out-patient care (odds ratio 0.63, 95% CI: 0.40–0.98, p = 0.042) and psychotropic medication prescription (odds ratio 0.66, 95% CI: 0.43–1.00, p = 0.049), with a similar but non-significant association for disability pension (odds ratio 0.65, 95% CI: 0.42–1.01, p = 0.058) (Table 3). This means that individuals with a later onset of anorexia nervosa were less likely to require psychiatric in- and out-patient care and psychotropic medication. For every one-year increase in age at anorexia nervosa onset, the odds of utilising psychiatric out-patient care decreased by 37% (odds ratio 0.63, 95% CI: 0.40–0.98). Point estimates and confidence intervals remained largely unchanged in the multivariable analyses (Table 3). Age at onset also emerged as the most influential variable in the multivariable models, explaining the largest proportion of discrimination performance, ranging from 23% for disability pension to 43% for psychiatric out-patient care and 46% for psychiatric in-patient care (Table 3, Fig. S1). No other predictors were significantly associated with any of the binary healthcare utilisation outcomes.

Table 3 Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses of predictors of psychiatric healthcare utilisation, disability pension and psychotropic medication use in the anorexia nervosa group

ROC AUC, receiver operating characteristic area under the curve; OCPD, obsessive–compulsive personality disorder.

Statistical analyses were conducted using logistic regression. Results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals, representing the effect per one-unit increase in each predictor. All listed variables were included in the multivariable analyses.

Discriminatory performance of the univariable models was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

In the multivariable models, variable importance was quantified as relative importance, derived from Shapley decomposition of Tjur’s coefficient of discrimination. This method decomposes the model’s total discriminatory performance into contributions from each predictor, averaging across all possible orderings to ensure a fair attribution. Relative importance values were rescaled to sum to 1 for each model, allowing direct comparison of each variable’s contribution to the overall model performance.

Among the discrete count outcomes, a higher minimum BMI z-score was significantly associated with fewer somatic in-patient care days (0.87-fold change per 1 z-score increase, 95% CI: 0.77–0.98, p = 0.025). This means that the number of days in somatic in-patient care decreases for every increase of the BMI z-score at anorexia nervosa onset. Premorbid ASD or OCPD was associated with greater psychiatric in-patient care (7.95-fold change, 95% CI: 2.00–31.7, p = 0.005) and more disability pension days (3.79-fold change, 95% CI: 1.17–12.2, p = 0.030). Premorbid perfectionism was associated with significantly fewer psychiatric in-patient care days (0.03-fold change, 95% CI: 0.01–0.18, p < .001), disability pension days (0.03-fold change, 95% CI: 0.00–0.25, p = 0.002) and psychotropic prescriptions (0.07-fold change, 95% CI: 0.02–0.32, p = 0.001), with the associations for in-patient care (p = 0.049) and disability pension (p = 0.004) remaining significant in multivariable models (Table S2).

Discussion

In the present 30-year follow-up study of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa, we found increased healthcare utilisation in this group including in-patient care, psychiatric out-patient care and prescribed psychotropic medication. The anorexia nervosa group had more days of sick leave and disability pension compared with their matched comparison cases. Less than half the anorexia nervosa group worked full time. A subgroup of 22% depended on benefits for their income, among this group were two individuals with enduring eating disorders and most participants presenting with prominent ASD features. Forty-five percent in the anorexia nervosa group had received social assistance at some point. A lower age at anorexia nervosa onset emerged as a predictor of requiring more in- and out-patient care and psychotropic medication.

The participants in the Gothenburg anorexia nervosa study had a good long-term outcome regarding mortality and full symptom recovery, as presented previously. Reference Dobrescu, Dinkler, Gillberg, Råstam, Gillberg and Wentz25 We therefore expected healthcare utilisation to decline over time and employment status to normalise in the long term. In line with other reports of healthcare utilisation in anorexia nervosa, Reference Ágh, Kovács, Supina, Pawaskar, Herman and Vokó6,Reference Mitchell, Myers, Crosby, ONeill, Carlisle and Gerlach12,Reference Striegel-Moore, DeBar, Wilson, Dickerson, Rosselli and Perrin13 we found increased consumption compared with controls, including in-patient care, visits to psychiatric out-patient care and prescribed psychotropic medication. Examining the patterns of in-patient care over a 30-year period (Fig. 1), the most prominent trends of high in-patient care occurred around the time of the study start (1985) and the following 8 years. A less prominent increase in psychiatric in-patient care in the anorexia nervosa group could be observed later (year 2004 to 2008). During these years, the majority of the participants went through pregnancies and childbirth. As pregnancy and the transition to motherhood can be an especially challenging time for individuals with a history of eating disorders, Reference Makino, Yasushi and Tsutsui37,Reference Sommerfeldt, Skårderud, Kvalem, Gulliksen and Holte38 the elevated rates may reflect a period in life when the participants had an increased risk of relapse. Over one third of the anorexia nervosa group had ever been admitted to psychiatric in-patient care and 23% had been hospitalised with an eating disorder diagnosis. These results reflect the proportion of individuals with anorexia nervosa in need of more intense treatment alternatives in the course of their illness, which is reported to be approximately 20 to 30%. Reference Herpertz-Dahlmann39

In line with results presented by Striegel-Moore et al Reference Striegel-Moore, DeBar, Wilson, Dickerson, Rosselli and Perrin13 anxiolytics and antidepressants were commonly prescribed to individuals with a history of anorexia nervosa. This was an expected finding as 38% in the anorexia nervosa group were found at the 30-year follow-up to have other psychiatric disorders, with anxiety disorders being the most common psychiatric comorbidity. Reference Dobrescu, Dinkler, Gillberg, Råstam, Gillberg and Wentz25 A considerable subgroup of 31% in the COMP group had also been prescribed psychotropic medication compared with 43% in the anorexia nervosa group, although this difference was not statistically significant. However, the number of prescriptions was much higher in the anorexia nervosa group.

In total, 22% in the anorexia nervosa group received a disability pension, which is comparable to results reported in a Swedish register study of anorexia nervosa patients; Reference Hjern, Lindberg and Lindblad14 however, we expected a better outcome as the register sample included in-patients only. The long-term follow-up studies by Löwe Reference Löwe, Zipfel, Buchholz, Dupont, Reas and Herzog17 and Ratnasuriya Reference Ratnasuriya, Eisler, Szmukler and Russell16 also included severe cases of anorexia nervosa and in contrast to these two studies, outcome regarding employment was better in our study. Compared with another community-based long-term follow-up study, the FinnTwin study, Reference Mustelin, Raevuori, Bulik, Rissanen, Hoek and Kaprio18 the outcome was worse regarding employment and disability pension. In contrast to the results of the present study, the FinnTwin study reported no differences between individuals with anorexia nervosa and their unaffected controls regarding employment status, sick leave and disability pension. Our study had a much longer follow-up period than the FinnTwin study and no evidence-based treatment for anorexia nervosa had been developed by the time the participants in our study had their anorexia nervosa onset, which may explain the worse outcome. In terms of educational attainment, 40% in the anorexia nervosa group had a university degree, which is in line with results from the FinnTwin study. Reference Mustelin, Raevuori, Bulik, Rissanen, Hoek and Kaprio18

Age at anorexia nervosa onset emerged as a predictor of healthcare consumption including in- and out-patient care and psychotropic medication. The predictor had significant odds ratios in all univariable models except for disability pension and explained relatively large proportions of the variance in all multivariable models (binary outcomes), albeit not statistically significant. This finding is in line with outcome studies of childhood-onset anorexia nervosa that have shown an unfavourable course of illness for this group, including higher rates of chronicity and morbidity. Reference Herpertz-Dahlmann, Dempfle, Egberts, Kappel, Konrad and Vloet40 Furthermore, it reflects the findings from a previous follow-up study of this sample where a lower age at onset of the disorder predicted an increased risk of not achieving full eating disorder symptom recovery. Reference Dobrescu, Dinkler, Gillberg, Råstam, Gillberg and Wentz25

The outcome regarding the discrete count variables showed a less consistent pattern across outcomes and predictors. However, results indicate that ASD or OCPD before anorexia nervosa onset predicted an increased number of days in psychiatric in-patient care and more days of disability pension. This is in line with the poorer outcomes considering overall functioning and longer duration of anorexia nervosa observed in individuals with comorbid ASD. Reference Nielsen, Dobrescu, Dinkler, Gillberg, Gillberg and Råstam41,Reference Saure, Laasonen, Lepistö‐Paisley, Mikkola, Ålgars and Raevuori42 Furthermore, longer duration of admission has been observed in individuals with anorexia nervosa and coexisting ASD. Reference Zhang, Birgegård, Fundín, Landén, Thornton and Bulik43 When controlling for other variables the predictor did not remain significant.

Premorbid perfectionism predicted a lower consumption of psychiatric in-patient care, psychotropic medication and fewer days of disability pension. Considering that our research group has previously reported that premorbid perfectionism predicts a good anorexia nervosa outcome in the same sample, this finding was not unexpected. Reference Dobrescu, Dinkler, Gillberg, Råstam, Gillberg and Wentz25 In contrast, perfectionism has also been described as a risk factor for developing and maintaining anorexia nervosa and is linked to worse treatment outcomes. Reference Fairburn, Cooper, Doll and Welch44,Reference Sutandar-Pinnock, Blake Woodside, Carter, Olmsted and Kaplan45 One possible reason why individuals with premorbid perfectionism use less healthcare is that they may follow treatment recommendations more closely, making them less likely to relapse. However, when interpreting the results, the fact that no validated instrument was used to assess premorbid perfectionism, as no such instrument existed 30 years ago, should be taken into account.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this research, which is based on a prospective design, has the longest follow-up period of any anorexia nervosa study in the world. The sample is community-based and has been followed along with a matched comparison group. As far as we know, this is the first long-term follow-up study of anorexia nervosa examining health economic outcomes including healthcare utilisation, social assistance, sick leave and disability pension over a period of 30 years. The study mainly relied on data from Swedish national registers supplying reliable information on outcome measures over a long period of time. In addition, we combined register data with information from interviews and self-reports collected at the 30-year follow-up examination. The 4% drop-out rate at the 30-year follow-up examination was notably low compared with other long-term follow-up studies, indicating strong participant retention and a minimal risk of attrition bias.

The current study has some limitations to be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample size is relatively small and only half the group was drawn from a total birth cohort, which reduces the generalisability to some extent. Due to the nature of the study, a 30-year follow-up design, the sample size was limited from the beginning, and no formal power analysis was performed. Second, some limitations relate to the registry data: (a) specialised out-patient care by health professionals other than physicians was not stored in the NPR, and such data would have been valuable for estimating treatment efforts during the follow-up period; (b) data from primary care visits are not included in the registries; (c) no information was found in the registries after the emigration of some participants. In our analysis, these individuals were retained and considered to have ‘no healthcare visits,’ which may underestimate healthcare utilisation as these participants are likely to have used healthcare abroad to some extent; (d) NPR in-patient diagnoses were available for the entire study period (1964–), whereas NPR out-patient diagnoses (2001–) and the Swedish prescribed drug register (2005–) were not yet available at the time of the participants’ anorexia nervosa onset. It would have been beneficial to have access to out-patient care data around the time of the onset of anorexia nervosa to obtain a more comprehensive estimate of the healthcare needs and utilisation at the time of anorexia nervosa onset; (e) the prescribed drug register data-set lacked detailed information on the duration and indication of prescribed medications, which prevented us from determining whether the prescriptions were intended for eating disorder symptoms, comorbid conditions or other purposes. Third, there are some limitations regarding the assessed diagnoses and traits. A notable limitation is the absence of a validated instrument to assess premorbid perfectionism, as no such tool was available at the time, 30 years ago. Instead, perfectionism was evaluated through extensive interviews and a psychiatrist blinded to group status assigned the perfectionistic traits based on de-identified case-notes. The use of retrospective data and de-identified clinical notes introduces potential limitations including the risk of diagnostic misclassification. Although no formal diagnostic assessments for ASD or OCPD were conducted, the diagnoses were based on comprehensive developmental histories and clinical observations in Study 1. Another methodological limitation relates to the use of different diagnostic criteria at baseline (DSM-III R, DSM-IV) and follow-up (DSM-5). Changes between DSM editions may affect the consistency of diagnoses over time, potentially influencing prevalence rates, interpretation of remission and the classification of comorbidities. Fourth, outcomes may also have been influenced by other factors such as treatment quality and policy shifts over 30 years. For instance, access to eating disorder treatment may have varied over time, particularly given that no specialised eating disorder clinics for children and adolescents were available at the start of the study in 1985. The first specialised eating disorder unit in Gothenburg opened in 1994 and evidence-based treatments have since been developed. Moreover, in Sweden, it has become increasingly difficult to obtain disability pension or sickness compensation over the years, especially following the implementation of the ‘rehabilitation chain’ in 2008, which introduced clear time limits for how long an individual can receive sickness benefits. The rehabilitation chain made it more difficult to remain in the sickness insurance system long-term and reduced the pathway to receiving disability pension. While these societal and policy shifts may have had an impact on outcomes, it was beyond the scope of this study to analyse these factors in detail – an important limitation to acknowledge. In addition, our study did not include any estimates related to the burden of caregiving for a family member with anorexia nervosa, which must be considered a limitation. Eating disorders affect not only the individual with the disorder but also relatives, in particular caregivers (parents). Family members are usually the main carers for most of the duration of the eating disorder. Reference Treasure, Murphy, Szmukler, Todd, Gavan and Joyce46 This is an important aspect in terms of burden-of-disease studies in anorexia nervosa that has received very limited attention and should be addressed in future burden-of-disease studies of eating disorders. A final limitation is the relatively small sample size in relation to the number of evaluated predictors. Although point estimates and confidence intervals remained largely unchanged, several predictors that were statistically significant in univariable analyses became non-significant or borderline significant in multivariable models. This pattern, however, suggests limited multicollinearity and minimal confounding between covariates, thereby supporting the reliability of the univariable estimates despite reduced statistical power in the adjusted models.

Implications

In this 30-year follow-up study of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa, increased healthcare utilisation was observed and remained for several years after the anorexia nervosa onset. Individuals with a lower age at onset of the disorder were more likely to require in- and out-patient care over the years, even after the majority had overcome their eating disorder. Additionally, a significant minority experienced long-term impairments in work capacity. These findings suggest that healthcare planning for individuals with anorexia nervosa should incorporate early occupational therapy, return-to-work support and interventions targeting social functioning. This study can inform policy-makers about the long-term burden of anorexia nervosa and the related costs to enable effective and informed decisions about priority areas and to allocate resources to reduce this burden. Investments in targeted prevention, early detection and treatment of childhood-onset anorexia nervosa are particularly important measures to decrease the long-term burden and costs to society.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10494

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, S.R.D., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants in the original study and the follow-ups.

Author contributions

S.R.D. and E.W. conceived and carried out the study, participated in the acquisition of the data and together with M.R. and K.B. were involved in data analyses, the interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. C.G., I.C.G. and L.D. participated in the acquisition of the data and were involved in the data interpretation. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

E.W. received support from the Jane and Dan Olsson Foundations (2015 and 2016-55), the Wilhelm and Martina Lundgren Foundation (vet2-73/2014, and 2017-1555), the Petter Silfverskiöld Memorial Foundation (2016-007), the Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-813401 and #ALFGBG-965750) and the Swedish Research Council (2023-01799). S.R.D. received support from the Royal and Hvitfeldt Foundation (2016) and the Foundation for Queen Silvia Children’s Hospital (2018). L.D. was supported by Queen Silvia’s Jubilee Fund (2016) and the Samariten Foundation (2016-0150). C.G. received grant support from the Swedish Research Council (521-2012-1754), the AnnMari and Per Ahlqvist Foundation and the Swedish State Support for Clinical Research. All authors, except K.B., received research support from the Birgit and Sten A. Olsson Foundation for research into mental disabilities.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.