Introduction

Liberal democracy is under pressure. In the midst of a global democratic recession (Lührmann & Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019), scholars and activists recognize that democracy's survival is not guaranteed, even in countries previously considered stable democracies. Today's democratic decline is characterized by a gradual process, often under the guise of legality (Lührmann & Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Runciman, Reference Runciman2018). Leaders such as Orbán, Bolsonaro, and Trump, despite their authoritarian leanings, were elected through democratic processes and have maintained substantial public support. Consequently, contemporary democratic backsliding in developed nations is more frequently linked to the actions of ordinary citizens at the polls than to military coups or other overtly anti-democratic means (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016).

Democracy researchers stress the significance of vigilant citizens in thwarting authoritarian takeovers, underscoring the essential role of ordinary citizens' commitment to democracy (Linz & Stepan, Reference Linz and Stepan1996). While most citizens in democratic societies strongly support abstract notions of popular rule (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Bol and Ananda2021; Wuttke, Gavras, et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022), beneath the surface, the attitudinal foundations of democracy seem more precarious (Wuttke, Reference Wuttke2022). Some self-professed democracy supporters actually fail to embrace crucial liberal democratic principles like pluralism or compromise (Kirsch & Welzel, Reference Kirsch and Welzel2018). Moreover, even among those who uphold liberal-democratic values, a tendency exists to prioritize partisan allegiances over these fundamental principles (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klaasen and Slade2020; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020). Additionally, despite the general appeal of democratic ideals, widespread dissatisfaction with how democracy functions, particularly during crises, remains a significant concern (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klaasen and Slade2020).

These conditions create ample opportunities for political elites to exploit the fragile commitment of citizens to liberal democracy (Arceneaux et al., Reference Arceneaux, Bakker, Hobolt and De Vries2020; De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Nachtwey & Frei, Reference Nachtwey and Frei2021). Moments of significant stress, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, present windows of opportunity for politicians to leverage weaknesses in democratic commitment, intensifying pre-existing anxieties, discontent and uncertainties (Becher et al., Reference Becher, Marx, Pons, Brouard, Foucault, Galasso, Kerrouche, Alfonso and Stegmueller2021; Bor et al., Reference Bor, Jørgensen and Petersen2021; Daniele et al., Reference Daniele, Martinangeli, Passarelli, Sas and Windsteiger2020).

In the United States, France, Germany, and other Western democracies, debates surrounding the COVID-19 response turned into discussions about democracy itself. Anti-system forces attempted to seize on concerns regarding executive overreach and restrictions on civil liberties and direct those into opposition against the liberal-democratic order as a whole (Amat et al., Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó‐Gimeno and Muñoz2020; Kolvani et al., Reference Kolvani, Lundstedt, Edgell and Lachapelle2021). Recognizing these vulnerabilities of citizen commitment to democracy, this study shifts focus to practical measures that political actors can implement who strive to sustain liberal democracy. We ask: What can be done to bolster citizen commitment to liberal democracy in times of crisis?

Redefining the concept of ‘democratic persuasion’ (Brettschneider, Reference Brettschneider2010), this study explores the efficacy of an actionable intervention to foster citizen commitment to liberal democracy. It examines whether political elites can bolster citizen support for democracy through targeted communication addressing citizens' concerns and advocating for liberal democracy. Specifically, in 16 digital town hall meetings between ordinary citizens and members of German parliaments, we randomly assigned if the legislators spent some of their time in a deliberate attempt to persuade the attending citizens of the value of liberal democracy. The findings indicate that democratic persuasion can significantly affect certain aspects of citizen commitment to liberal democracy, albeit with varied effects across different indicators and primarily in the short term.

Citizen commitment to democracy in times of crisis

The current state of mass commitment to democracy in Western societies can be summarized as a ‘precarious simultaneity of widespread but superficial support for democracy’ (Wuttke, Reference Wuttke2022). While there is a strong endorsement of democracy in the abstract (Wuttke, Gavras, et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022), deeper support for its fundamental procedures, practices and principles is lacking. Abstract support for democracy becomes more tenuous when considering the actual implementation of democracy and its institutions, which points to the fragility in the substantive backing of democracy among certain population segments.

Substantive support for the core principles of democracy is crucial for citizens to serve as effective safeguards against democratic erosion. Given that contemporary challenges to democracy often masquerade as democratic acts (Runciman, Reference Runciman2018), effective commitment to democracy necessitates a deep understanding and support of its foundational principles to recognize and respond to their breaches. The principles that underpin liberal democracy – pluralism, compromise and the rule of law (Skaaning, Reference Skaaning, Crawford and Abdul‐Gafaru2021) – are particularly relevant here because it is the liberal variant of democracy that is the specific target of current attacks (Pappas, Reference Pappas2019). Pluralism has been questioned by populist politicians who do not accept trade-offs or the need to compromise between competing legitimate interests in diverse societies (Pappas, Reference Pappas2019). Likewise, at the individual level, empirical findings show that some citizens do not fully endorse pluralist principles because they lack a sophisticated and properly ordered political belief system (Kirsch & Welzel, Reference Kirsch and Welzel2018) or because they subordinate these principles to partisan interests when they stand in conflict (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020).

In addition to embracing pluralist values, the perception of democracy as a legitimate system is another fundamental aspect of democratic commitment (Diamond, Reference Diamond2020). Legitimacy perceptions cannot be taken as given even among staunch liberal democrats, as they can erode when the government is perceived – rightly or wrongly – as failing to uphold democratic ideals (Lipset, Reference Lipset1981). Perceiving a system as legitimate also hinges on the evaluation of a system's current functionality. Surveys reveal widespread dissatisfaction with how democracy operates (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klaasen and Slade2020). Although satisfaction with democracy is inherently complex (Valgarðsson & Devine, Reference Valgarðsson and Devine2022), we consider it a key component of democratic commitment since discontent can diminish citizens' resolve to defend their democratic system against threats (Saikkonen & Christensen, Reference Saikkonen and Christensen2021).

Hence, some of the fragility in democratic support stems from citizens' dissatisfaction with and misunderstandings about democratic procedures, principles and practices. Rather than a direct desire to dismantle democratic governance (Wuttke, Gavras, et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022), these vulnerabilities present opportunities for potential autocrats to exploit (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic serves as a stark example of the vulnerabilities within democratic systems, demonstrating how pre-existing weaknesses, when combined with external shocks, offer opportunities for radical elements to alienate segments of the population from the democratic system. Crises, such as a pandemic, incite anxiety and uncertainty (Bor et al., Reference Bor, Jørgensen and Petersen2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, democratic (and undemocratic) governments decided to mitigate health risks through temporary, but wide-ranging, restrictions on individual liberties. In some cases, these decisions were enacted by executive orders at the expense of parliamentary deliberation. Even when objectively warranted and complying with the legal democratic order, to some citizens these decisions and the decision-making process appeared at odds with the principles that liberal democracy is supposed to hold dear (Amat et al., Reference Amat, Arenas, Falcó‐Gimeno and Muñoz2020). In situations when democratic representatives need to balance multiple undesired outcomes and mitigate trade-offs between multiple desirable values, citizens' tolerance of ambiguity is put to a stress test (Furnham & Ribchester, Reference Furnham and Ribchester1995). When such dilemmas are not convincingly communicated, discontent with the democratic process may emerge, including among citizens who consider themselves committed democrats.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, liberal democracies like the United States, France, and Germany saw extremist, populist and fringe groups quickly mobilize, exploiting public sentiments against governmental measures seen as overreaches. For instance, in Germany, the ‘Querdenken’ movement voiced strong opposition, labelling the government's actions as dictatorial while the radical-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) claimed that Germany was ‘no longer a democratic country’ (Küppers & Reiser, Reference Küppers and Reiser2022; Nachtwey et al., Reference Nachtwey, Schäfer and Frei2020). Similar protests took place in France and the Netherlands (France24, 2021; The Guardian, 2021). When the opportunity arose, critics of liberal democracy did not forfeit the chance to capitalize on the weaknesses of citizens' commitment to democracy. This situation highlights the need for proponents of democracy to develop counter-strategies to reinforce citizens' commitment to democracy during times of crisis, ensuring the resilience of democratic institutions.

Acknowledging that anti-system movements often sidestep direct opposition to liberal democracy is pivotal (Küppers & Reiser, Reference Küppers and Reiser2022; Nachtwey et al., Reference Nachtwey, Schäfer and Frei2020; Nachtwey & Frei, Reference Nachtwey and Frei2021). Instead, they frequently adopt pro-democratic or pro-liberal rhetoric which resonates with a significant number of citizens who, while supportive of liberal-democratic ideals in theory, express dissatisfaction with their practical implementation. This nuanced strategy by anti-system movements necessitates a sophisticated response from proponents of liberal democracy, tailored to bridge the gap between the democratic ideal and democratic reality (Ferrin & Kriesi, Reference Ferrin and Kriesi2016).

The concerns of citizens disillusioned with democracy, such as the infringement of individual liberties during the pandemic, have a basis in reality. This critique harbours the potential for destabilization when it overlooks the essential trade-offs and conflicts inherent in pluralistic societies. The core of democratic decision-making in pluralist societies involves balancing competing goals and interests. When necessarily imperfect policy outcomes are not seen as complex challenges requiring compromise but rather as manifestations of a corrupt or failing system, democracy's legitimacy suffers (Müller, Reference Müller2021).

Addressing concerns exploited by malevolent actors, yet rooted in legitimate or pro-democratic sentiments, poses a significant challenge. Providing context and alternative interpretations is essential. By not dismissing citizens' concerns and instead engaging with their perspectives, there is potential to shift views towards supporting the system. This approach encourages citizens to reconsider their stance, moving away from destabilizing viewpoints towards those that bolster democratic stability.

Making the case for democracy

The influence of political elites on public opinion is well-documented (Lenz, Reference Lenz2012; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Yet, political elites such as legislators who belong to political parties are usually incentivized to put their communicative power in the service of instrumental goals like winning office or building support for their party (Cantoni & Pons, Reference Cantoni and Pons2021; Wantchekon, Reference Wantchekon2017). We ask what would happen if politicians spent a share of their discursive capital not on their own candidacies, other parties or policies (López-Moctezuma et al., Reference López‐Moctezuma, Wantchekon, Rubenson, Fujiwara and Lero2022; Wantchekon, Reference Wantchekon2017), but on explaining the value of the democratic system that allows election debates and policy discussions to happen in the first place: Can political elites utilize their public platform to strengthen citizen commitment to democracy, and if yes, how can this be achieved? In a time when democracy itself is at stake, pro-democracy politicians should have an interest in working to sustain the liberal democratic system of government.

Interventions to foster democratic attitudes have so far concentrated on societies in transition to democracy (Finkel et al., Reference Finkel, Neundorf and Ramirez2023; Gibson, Reference Gibson1998) or on fragile states (Mvukiyehe & Samii, Reference Mvukiyehe and Samii2017). As the fragility of established democracies becomes increasingly apparent, there is a clear need to trial democracy-supporting interventions within established democracies. Most of these interventions rightly focus on what political elites can do to counter explicitly anti-democratic behaviours and rhetoric of fellow politicians (Hobolt & Osnabrügge, Reference Hobolt and Osnabrügge2022). Our focus, however, is on what politicians can do to strengthen the resilience of liberal democracy at the societal level by addressing citizens' concerns.

One line of research that is relevant to understanding the effects of democracy-related communication examines counter-strategies to fake news, misinformation and belief correction (Nyhan, Reference Nyhan2020). However, straightforward dissemination of facts does not always yield positive outcomes and may sometimes lead to unintended consequences (Nyhan, Reference Nyhan2020). A significant insight from these studies is the influential role of trusted intermediaries and political elites in shaping public perception and beliefs, indicating their potential in effective communication on democracy (Nyhan, Reference Nyhan2021).

Legislator-to-citizen communication is one channel through which public opinion may be shaped. We know that personal encounters between politicians and citizens can be an effective way of shaping citizens' attitudes, perhaps because the direct contact facilitates trust (Cantoni & Pons, Reference Cantoni and Pons2021; Foos, Reference Foos2018; Wantchekon, Reference Wantchekon2017). Town halls serve as effective platforms for this exchange, allowing politicians to engage with large groups of citizens (Abernathy et al., Reference Abernathy, Esterling, Freebourn, Kennedy, Minozzi, Neblo and Solis2019; López-Moctezuma et al., Reference López‐Moctezuma, Wantchekon, Rubenson, Fujiwara and Lero2022; Minozzi et al., Reference Minozzi, Neblo, Esterling and Lazer2015; Wantchekon, Reference Wantchekon2017). The efficacy of these interactions is further enhanced when communication is respectful, acknowledging participants' viewpoints in a non-judgmental manner (Muradova, Reference Muradova2021). This approach, supported by both survey-experimental (Xu & Petty, Reference Xu and Petty2022) and field-experimental evidence (Kalla & Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2020), suggests that respectful, direct encounters between citizens and politicians are a viable strategy for enhancing democratic commitment.

This approach goes beyond traditional civic education methods, the most recognized form of pro-democracy interventions (Finkel et al., Reference Finkel, Lim, Neundorf, Öztürk and Shephard2022, Reference Finkel, Neundorf and Ramirez2023). While civic education primarily targets the youth, democratic persuasion is aimed at adults, who possess extensive, often complex experiences with democratic politics. These experiences can lead to ambivalence towards democracy, as discussed above. Political persuasion, to be effective, must engage with the existing beliefs of citizens (Altay et al., Reference Altay, Schwartz, Hacquin, Allard, Blancke and Mercier2022). Therefore, democratic persuasion should directly address adults' concerns regarding the democratic process, its representatives and its outcomes.

Democratic persuasion

To delineate how interactions between citizens and politicians might bolster citizens' commitment to democracy, this study adopts and refines the notion of ‘democratic persuasion’ (Brettschneider, Reference Brettschneider2010). We understand democratic persuasion as the concerted effort to persuade the public in favour of democratic decision-making by acknowledging legitimate criticism, while actively making the case for democracy.

Democratic persuasionFootnote 1 is premised on the observation that while there is broad, abstract support for democracy, this often coexists with specific apprehensions regarding its application and a limited grasp of its core principles and mechanisms. It targets not the small minority of hardline democracy opponents but rather focuses on engaging those ‘wavering democrats’ who may not fully subscribe to liberal-democratic ideals or who have become disillusioned with the current state of democratic practices (see V-DEM, 2020).

Democratic persuasion recognizes that even committed democrats can harbour doubts about democracy's functionality, accepting the existence of varied legitimate views on its processes. It offers system-supporting perspectives by highlighting democracy's intrinsic value, elucidating the trade-offs and inherent imperfections in government decisions. Additionally, it aims to rectify misconceptions and counter misinformation through honest dialogue, leveraging these exchanges as opportunities to clarify and reinforce democratic principles. This approach comprises two main strategies: affirming democratic decision-making's value and directly addressing and correcting doubts and false beliefs about democracy.

Democratic persuasion is not limited to a specific group and can be utilized by anyone, from ordinary citizens in daily interactions to professors and politicians. Its most significant potential for attitude change lies with elites who can communicate with a large number of individuals. To test the efficacy of this strategy, we propose the following hypothesis:

Democratic persuasion hypothesis. Exposure to democratic persuasion increases support for democracy and facilitates understanding of the trade-offs inherent in political decision-making, increases trust in politicians and reduces reservations towards the political process and democratic institutions.

Design

Setup

We conducted 16 digital town hall meetings between ordinary citizens and members of German state and federal parliaments, ostensibly on the topic of the COVID-19 pandemic. We worked together with politicians and randomly assigned half of the town halls to include the democratic persuasion intervention, where politicians made the case for democracy, following a concise lightning talk by a professor about democracy in times of COVID-19.Footnote 2 We implemented this field experiment in collaboration with eight federal and state legislators, representing five German parties. Four legislators were members of governing parties at the federal level (one CDU, three SPD) and four legislators were members of federal opposition parties (two Free Democrats (FDP), one Green, one Left Party). We deliberately excluded representatives from the radical right AfD, anticipating their probable reluctance towards the intervention. Additionally, due to concerns that AfD politicians' opposition to the COVID-19 vaccine might lead to the spread of harmful misinformation, we chose to prioritize public health. The town halls took place between November 2020 and January 2021, amidst Germany's ‘second wave’ of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the town hall, we pre-registered the theoretical arguments, hypotheses, power analysis and the analysis syntax (see https://osf.io/b8de9/).

Sample

Social media acts as a conduit for disseminating misinformation and extremist narratives concerning both the COVID-19 pandemic (Küppers & Reiser, Reference Küppers and Reiser2022) and democratic practices (Guess et al., Reference Guess, Nyhan and Reifler2020). We, therefore, deliberately used Facebook ads to recruit a heterogeneous sample of German citizens via quota sampling to participate in one of the 16 Zoom town halls. We used the following demographic strata to target the ads, which were reflective of the latest German census estimates: (1) age groups (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60+), gender (M/F), education (low, middle, high) and federal state. The town halls were advertised on Facebook as opportunities for citizens to meet members of parliament and discuss with them about COVID-19 – without explicit reference to democracy. Interested Facebook users were directed to an online survey where they were informed about the town halls and the associated academic study, gave consent on participation and data processing and filled in a baseline survey. During the survey, six respondents were screened out for meeting the criteria of militant anti-democracy (see online Appendix 10.1). All other respondents were asked to select one town hall meeting from a list of town halls with information on the date, the name of the participating politician and the location of the politician's electoral district. We did not indicate the party affiliation of the politician but since the name of the politician was displayed on the sign-up page, participants' party preferences played a (small) role in their town hall choice (see online Appendix 10.1).

A total of 529 individuals registered for the town hall meetings, but only 183 participated and completed the post-town hall survey. The dropout rate exceeded expectations, resulting in a smaller sample size than initially planned in the pre-registered power analysis.Footnote 3

Treatment assignment

Each parliamentarian participated in two 60-minute town halls, with one randomly assigned to include democratic persuasion, ensuring each politician conducted one control and one treatment session. Citizens were self-selected into a town hall of their choice and were aware that each politician conducted two town hall meetings. However, they were unaware of the systematic differences between these two town halls. Because pair block randomization was conducted within politicians, there is no reason to expect systematic differences in potential outcomes between town halls conducted by the same legislator. We show balance tests in online Appendix 10.9. Overall, treatment and control groups are well balanced on pre-treatment attitudes and most demographics. Given the multiple tests we conducted, there is some demographic covariate imbalance on age groups and whether respondents are based in East Germany (more respondents in the treatment group are based in East Germany). We report both unadjusted and covariate-adjusted complier average causal effect estimates throughout the paper.

Experimental conditions

The concept that democratic persuasion is a strategy anyone can utilize was illustrated in the treatment town halls, where various participants (politicians, an academic and citizens) participated in democratic persuasion activities. Hence, our intervention is a bundle of treatments but the focus of our intervention is clearly on the politician who we instructed to engage in democratic persuasion in the treatment town halls. Notably, politicians dominated speaking time across both experimental conditions. On average, politicians spoke for 47 per cent of the time in the democratic persuasion town hall and for 56 per cent of the time in the standard town hall, underscoring their central role in the intervention. The academic spoke for 9 per cent of the duration of the treatment town hall only, and audience members spoke for approximately 33 per cent of the time, in both conditions. The ratio of politician to academic intervention time was hence five to one in the democratic persuasion town hall, and all audience members combined had a lower speaking time than the politician.

Prior to each town hall, we briefed politicians and their staff on the setup and experimental conditions, advising them to conduct the standard town hall as usual while emphasizing democratic persuasion in the treatment condition. We detailed the persuasion strategy, gaining all politicians’ agreement to follow through. Random assignment determined the sequence of town halls, with some politicians starting with the standard format before the democratic persuasion session, and others doing the reverse.

Each town hall proceeded according to the following script: the moderator opened the event, introduced the member of parliament and outlined the question-asking process. After the introduction, the control and experimental town halls diverged. Following Broockman and Kalla (Reference Broockman and Kalla2016), the democratic persuasion intervention consisted of a bundle of elements, with a view of manipulating individual elements of the intervention in subsequent work after having first tested the efficacy of the broader concept (Kalla & Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2020). Central to the intervention was that politicians were instructed to connect their discussion of pandemic politics with the recurring attempt to engage in democratic persuasion. That is, politicians were encouraged to circle back to the question of democracy where possible during the ensuing Q&A, proactively addressing concerns about the practice of democracy and explaining the process of democratic decision-making in a pluralistic society.

This element of our intervention was accompanied by other manifestations of democratic persuasion. After the introduction, subjects in the treatment condition listened to a short presentation, lasting around 4-5 minutes, about ‘Democracy in times of COVID-19’ by a political scientist whom we consider as representing societal elites with communicative power. The presentation challenged the thesis that ‘during the pandemic, civil liberties were restricted to an extent that it is no longer possible to speak of proper democracy in this country’. The presentation (see the Online Repository) implemented democratic persuasion by highlighting the trade-offs democratic decision-making faced between individual freedoms, such as the freedom of assembly and the state's duty to avoid harm. After the presentation, a member of the German federal parliament or a member of one of the state parliaments took up the baton and engaged in democratic persuasion during short introductory remarks that lasted around 5 minutes. In the standard town hall, the politician was invited to speak for 10 minutes about relevant aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic such as economic and public health measures, but did not stray into discussions on democracy, unless explicitly asked by one of the attendants in the Q&A. There was no presentation element to the standard town hall condition. A research assistant (confederate) participated in all the town halls, serving as an ice-breaker to ask one of the first questions. In the democratic persuasion town halls, the confederate's question was concerned with the shortcomings of democracy during the pandemic. In the standard town halls, the question concerned practicalities of policies in relation to amateur sports.

In both experimental setups, following the politician's introductory remarks, the moderator transitioned to the question-and-answer session, allowing citizens to pose questions based on the sequence of their raised virtual hands in Zoom. This approach was designed to ensure that every participant interested in asking a question had the opportunity to do so, fostering an inclusive and interactive environment for dialogue.

The size of the town halls varied and ranged from 8 to 30 participants (5–19 wave 2 respondents), averaging 17 participants (13 wave 2 respondents). The experiment was approved by the LSE ethics review committee. We discuss the ethics of the experiment and the democratic persuasion intervention in detail in online Appendix 10.7.

Measures

Attitudinal outcomes were measured via a three-wave panel survey. Subjects completed the baseline survey after signing up via Facebook. The first post-treatment survey was administered at the end of the town hall via Zoom poll. A second post-treatment wave was distributed one month after the town hall, but the analysis of this was not pre-registered. A total of 183 subjects answered the first post-treatment wave on Zoom, and 144 participants answered the second post-treatment wave.

We pre-registered four primary outcomes which are detailed in the results section (see online Appendix 10.3 for question wordings), each mapping onto the concepts described in the hypothesis: satisfaction with democracy (measured on a scale from 1 to 5, referring to democratic support as mentioned in the hypothesis), support for pluralism (scale ranging from 1 to 4, referring to the trade-offs mentioned in the hypothesis), concern about democratic rights (binary, 0/1, referring to reservations towards the political process mentioned in the hypothesis) and a three-point behavioural action scale which includes whether subjects signed two petitions to defend democratic pluralism and signed up for a ‘democracy newsletter’. To keep the experiment authentic, we used active petitions that relate to the concept of defending liberal democracy: One petition was against the delay of the German federal election; and the other focused on defending liberal rights in the European Union. We also measured agreement with trust in politicians, with the Churchill sentiment on democracy, and with populist attitudes. Due to strong floor and ceiling effects pre-treatment, we pre-registered classifying those measures as secondary and reported results in the appendix (see online Appendix 10.10). We also measured support for COVID-19 social distancing measures as a secondary outcome.

Analysis

We estimate treatment effects based on randomization inference using one-tailed tests (as pre-registered), testing whether we can reject the sharp null hypothesis. The randomization-inference procedure accounts for the pair-random assignment of town halls to treatment and control within each politician and the fact that subjects are clustered within town halls. The comparison is hence between subjects who attended the treatment town hall and subjects who attended the control town hall, held by the same politician. We report the unadjusted and covariate-adjusted difference-in-means estimates (covariates: pre-treatment measure of the outcome, gender, age, education, ideology, region, party ID, all measured pre-treatment).

Results

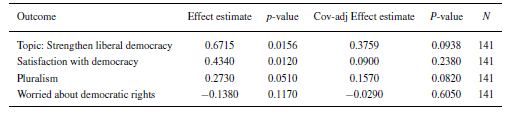

The town halls took place amid contentious and consequential times. For many participants, the issues at stake were pressing and personal. For a significant number, this represented the first occasion for public dialogue on their pandemic-related concerns or for direct engagement with parliamentary representatives. Table 1 shows that citizens went into these gatherings with diverging viewpoints. The town halls attracted a diversity of opinions, reflecting the heated discussions that took place in Germany and many other countries in the winter of 2020/2021.

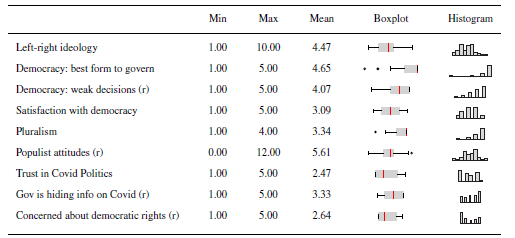

Table 1. Relevant variables before treatment

Note: Populism, concerns about rights were measured on a binary scale in waves 2 and 3.

The quota sampling aimed to minimize bias in the demographic targeting for the town hall advertisements. Unlike other Facebook-recruited studies (Finkel et al., Reference Finkel, Neundorf and Ramirez2023), citizens needed to reserve time to participate in a 60-minute town hall meeting. As is common for acts of political engagement, self-selection resulted in an over-representation of university-educated individuals (see online Appendix 10.8). There is little evidence of political bias with regard to democracy-related or ideological orientations. Both left- and right-leaning citizens joined the town hall meetings, yielding a composition of ideological orientations among the participants that closely mirrors the distribution in the general population of German citizens.

On average, participants held positive attitudes toward the abstract concept of democracy and towards pluralist principles, although variation in the latter was notable. However, the fragility in commitment to democracy was evident, especially in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, with many participants expressing dissatisfaction with democratic processes and concerns over democratic rights' infringement during the pandemic. For instance, one in five participants accused the government of hiding important information on the pandemic. Hence, the sample of participants comprises a mix of committed and wavering democrats. How did exposure to democratic persuasion change their attitudes towards democracy?

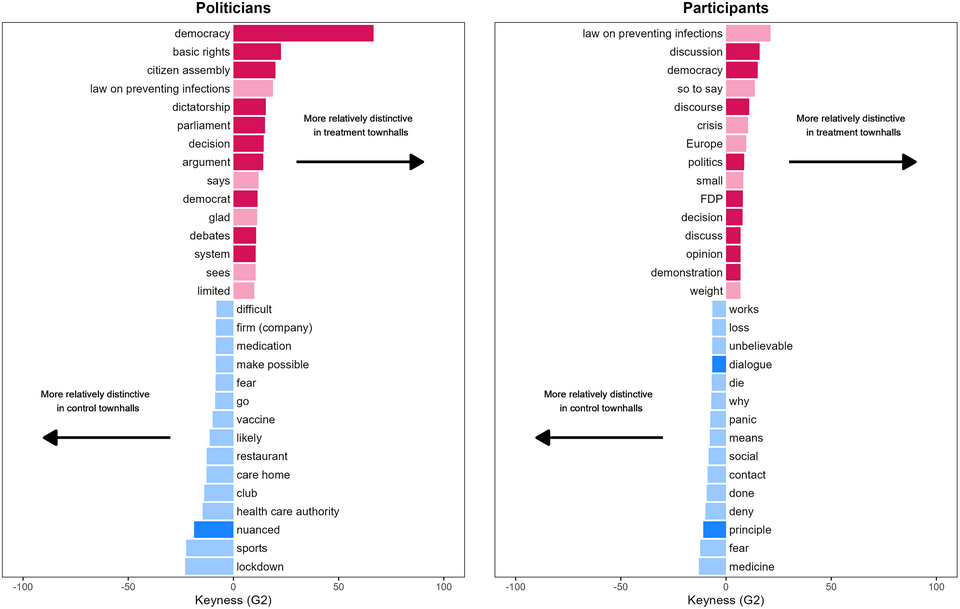

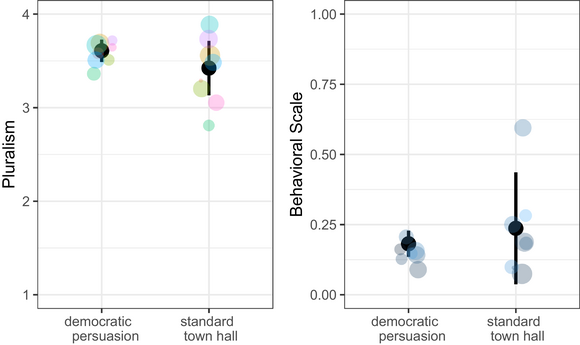

Figure 1 shows how the town halls unfolded in the two experimental conditions, based on the results of a keyness analysis of everything that was said during these meetings. Separately for politicians and participants, the plots show which terms were most distinct for the treatment (red) and control (blue) town halls. Words that relate to the concept of democracy are displayed in darker colour.

The results confirm that politicians in the treatment condition spoke much more frequently about democracy, an indicator that they carried out democratic persuasion as intended. This shift in emphasis also influenced participant interactions, leading to more questions and comments about the procedural and practical aspects of democracy, while topics related to the medical, psychological and economic facets of the pandemic received less attention in the treatment town halls.

Figure 1. What was said in the democratic persuasion versus control town hall. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 1 also conveys a sense of how politicians tried to make the case for democracy. Politicians in the treatment condition emphasized fundamental principles of liberal democracy (‘basic rights'). They also discussed the institutions (‘parliament’, ‘citizen assembly') and democratic processes (‘debates’, ‘argument’, ‘decisions') through which democratic politics could take on the challenge of complex decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here is an example of how one politician of a governing party opened the discussion in the treatment condition. The quote showcases democratic persuasion's proactive engagement with existing concerns and the attempt to explain the principles and processes by which liberal-democratic politics responded to the crisis:

I am looking forward to this dialogue in the time of the second lockdown (…) when many say our democracy has already been abolished and we live in a dictatorship. I disagree. What we have in terms of rule of law, executive, judiciary, legislative is outstanding. It could still be better. Government should no longer act by decree. We must uphold the prerogative of parliament's law also in times of a pandemic. This is one topic where we can learn from the mistakes we made early this year and we debate this in parliament on Wednesday. (…)

Any decision we take involves balancing the arguments of multiple sides. (…) No one was spoon-fed with wisdom. I hope, I and my party never believe to have a monopoly on the truth and I hope all citizens realize that (…) decisions are always compromises and that we can change our minds when receiving new information. (…) Democracy lives on disagreement. (…) We need to find ways to listen to each other and to then compromise. This is why I am now looking forward to an honest, civil discussion with you.

An opposition politician in the democratic persuasion condition answered a question by a town hall participant on democracy during the crisis and how opponents of the government's crisis politics were, in their opinion, unfairly treated, in the following way, explaining the role of the opposition in parliamentary decision-making:

When it comes to concrete policy-making, I will give you an example, based on the law to prevent infectious diseases. We proposed, as an opposition party in the German federal parliament, an alternative to the government's proposal, which would have addressed many points of criticism that were made by the public, also on social media, in facebook groups etc […] We have proposed this amendment in parliament - it was debated in the Bundestag. But the majority decided differently - and after all, it was a democratic process, where the opposition had the opportunity to propose an alternative. At the same time I'm also really concerned that some of our political competitors – but to be fair there is also a broad spectrum of views in other parties – don't distinguish clearly between ‘anti-democrats’ and people who express criticism of the substance of specific policies.

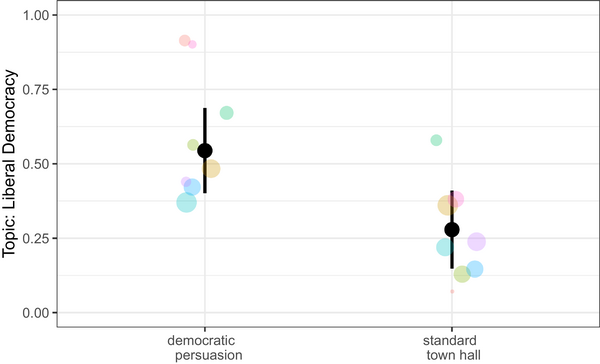

Participants recognized that politicians made the case for democracy in the treatment town halls. Figure 2 shows the results of a manipulation check: whether subjects correctly identified the theme of the town hall as ‘advocating for liberal democracy’ among a set of four themes. The figure shows that subjects in the ‘democratic persuasion’ condition were 26 percentage points (24 percentage points covariate-adjusted) more likely than subjects in the standard town hall condition to identify ‘liberal democracy advocacy’ as the major theme of the democratic persuasion town hall. This difference is significant with p = 0.001 (one-sided), indicating that the manipulation succeeded.

The findings highlight the central role of democracy in the treatment town halls, suggesting three key insights. First, the results bolster confidence in the internal validity of the experiment. Second, as expected, politicians’ usual way of communicating with citizens leaves ample room for the inclusion of democratic persuasion strategies. Lastly, the politicians demonstrated both willingness and ability to use democratic persuasion effectively when prompted. This shows the potential for enhancing democratic engagement through deliberate dialogue.

Figure 2. Manipulation check. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Moving to identifying the impact of democratic persuasion on citizen commitment to democracy, we observe some evidence that randomly assigned exposure to democratic persuasion made citizens more committed to democracy as they left the town hall meeting.

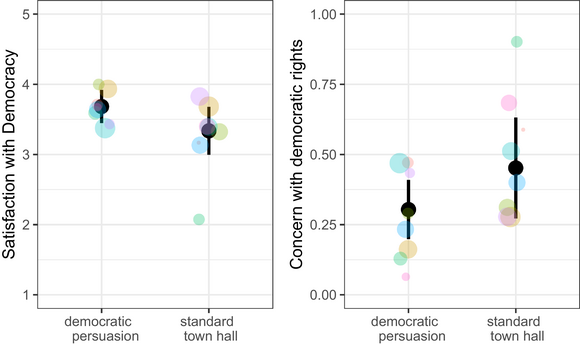

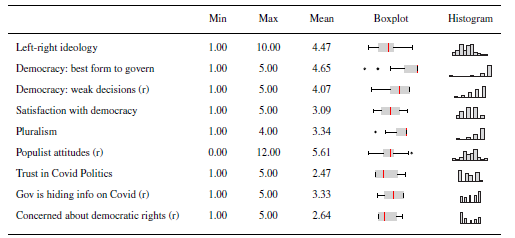

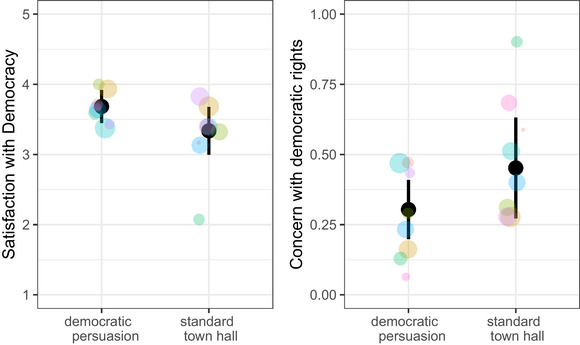

The left panel of Figure 3 reports mean levels of satisfaction with democracy, comparing participants who attended the democratic persuasion town hall to the participants in the standard town hall. Arguably, any interpretation of a population's satisfaction with democracy needs to be situated in its specific context. At the time of the town halls, politicians at the political fringes aggressively questioned the legitimacy of the government's pandemic response and stirred doubts about whether Germany could still be considered a democratic country (Küppers & Reiser, Reference Küppers and Reiser2022; Nachtwey et al., Reference Nachtwey, Schäfer and Frei2020). Without taking a stance on the merits of particular policies, our intervention deliberately sought to bolster citizens’ satisfaction with the democratic process as experienced during the COVID-19 crisis, based on the idea that citizens who view this system favourably will likely see more reason to defend it against attacks.

Figure 3. Treatment effects on satisfaction with democracy and concerns with democratic rights. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Estimated mean attitudes in both experimental conditions with 95 per cent confidence intervals: bubbles in the background show cluster means for each town hall; the size of the bubble indicates townhall size; the colour of the bubble is a function of the experimental block, reflecting the politician who conducted the town hall; the colours have no political meaning.

The results show that democratic persuasion led a number of dissatisfied citizens to change their minds on democracy. Subjects who were randomly assigned to attend the democratic persuasion town hall were 0.35 points (on a 1–5 scale) more satisfied with democracy than subjects who attended the standard town halls (see online Appendix 10.5 for tabulated results).Footnote 4 The effect is different from zero with p = 0.03 (unadjusted, one-sided) and 0.07 (covariate-adjusted, one-sided, pre-registered), exhibiting some sensitivity to the analysis specification.

Are these meaningful effect sizes? The difference between individuals who participated in the control town halls and those who were exposed to democratic persuasion corresponds to a medium-sized effect of 0.36 standard deviations. This effect size indicates a 60 per cent chance that a subject in the treatment group reported higher satisfaction with democracy than a person in the control group (Gruijters & Peters, Reference Gruijters and Peters2017). Considering satisfaction with democracy as a binary variable, the observed effect size implies that for every seven citizens exposed to democratic persuasion, one of them will switch from dissatisfaction to expressing satisfaction with the democratic system (Gruijters & Peters, Reference Gruijters and Peters2017). Hence, these data show that democratic persuasion has the potential to make a practical difference in how citizens think about democracy.

The right-hand panel of Figure 3 reports on another aspect of democracy's perceived legitimacy in times of existential crisis. Given the rhetoric from the political fringes that Germans would no longer be living in a democratic country, we measured the degree to which citizens were concerned for their democratic rights. The democratic persuasion town halls highlighted the inevitable trade-offs elected politicians faced during the pandemic. The treatment sought to alleviate concerns about the temporary restriction on civil liberties by pointing to the democratic quality of the process preceding these decisions. As a result, the share of respondents who maintained worries about their democratic rights is 15 (unadjusted) or 13 (covariate-adjusted, pre-registered) percentage points lower in the treatment group, depending on specification (p = 0.12/0.09).

The online Appendix provides additional evidence that democratic persuasion effectively convinced citizens of the legitimacy of COVID-prevention measures (Table A10), which we pre-registered as a secondary outcome. The increased support for a battery of social distancing measures indicates that we do not find any trade-off between communicating effectively about democracy and persuading citizens about the values of public health policies. In contrast, it may be the case that some citizens had concerns about the social distancing measures introduced by the government based on democratic grounds that could be alleviated when addressed by politicians.

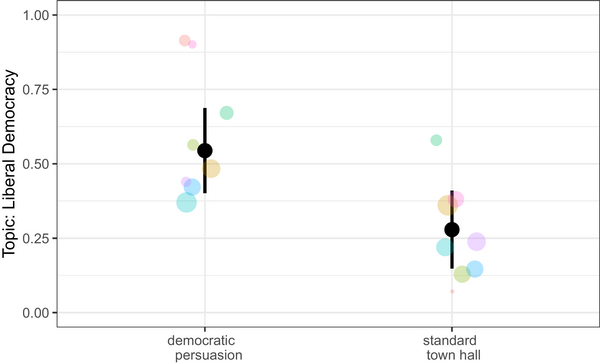

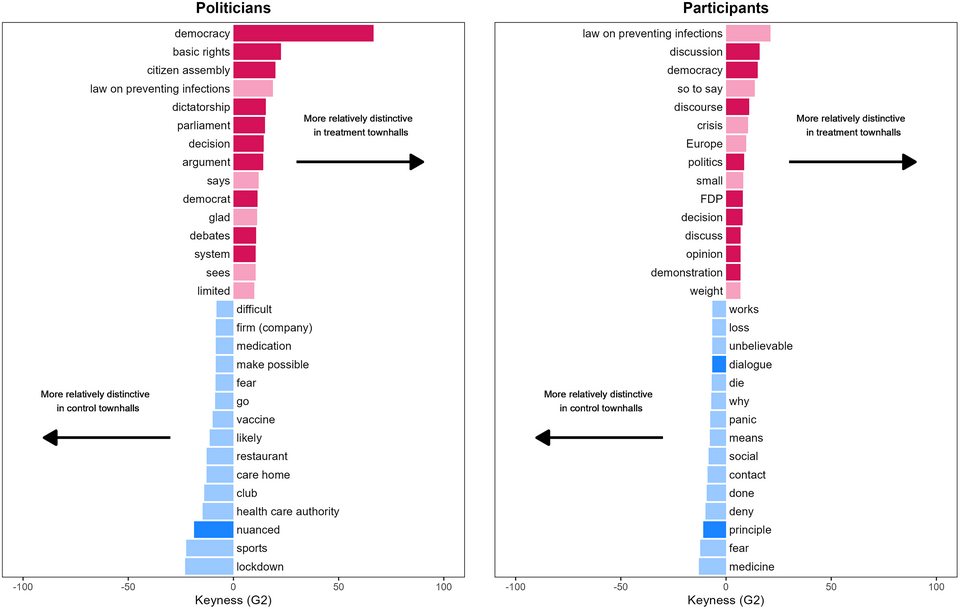

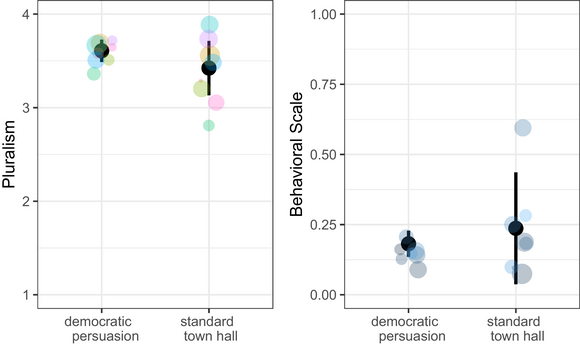

Moving away from outcomes on the specific Covid-context, the left-hand panel of Figure 4 shows endorsement of pluralist orientations, an index capturing four statements on core ideas underpinning liberal democracy (e.g., ‘when making political decisions, the interests and values of different social groups often conflict with one another';‘what is called a compromise in politics is just a betrayal of principles', reversed). Endorsement of these values is likely to foster a commitment to the liberal-democratic political system and may ease understanding of the trade-offs that are inherent in democratic governance.

Figure 4. Treatment effects on concerns with democratic rights and the on behavioural scale. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Estimated mean attitudes in both experimental conditions with 95 per cent confidence intervals; bubbles in the background show cluster mean for each town hall; the size of the bubble indicates townhall size; the colour of the bubble is a function of the experimental block, reflecting the politician who conducted the town hall; the colours have no political meaning.

Despite reflecting deep-rooted and therefore less malleable value orientations, participants in the treatment town halls endorse pluralist values slightly more strongly, but the effect is estimated with considerable noise. On a scale from 0 to 4, the endorsement of pluralist values is higher in the treatment group by 0.18 (unadjusted) or 0.1 (covariate-adjusted, pre-registered) scale points (p = 0.07 and 0.11, respectively). Exploratory analyses indicate that effects on the composite index are largely driven by facilitating acknowledgment that ‘politicians often find themselves in a situation in which they cannot fulfill all legitimate wishes at the same time and have to balance priorities’ (0.07, p = 0.09, unadjusted).

Beyond attitudes, we also investigate whether pro-democratic rhetoric affects behaviours. Figure 4 displays the results of our pre-registered behavioural outcome: a behavioural outcomes scale, which ranges from 0 to 3 actions that subjects could take: subscribe to a democracy newsletter and sign two pro-democracy petitions. Outcomes in the two randomly assigned groups are not significantly different (see online Appendix 10.6 for results on single indicators). Given the observed null results, it might be the case that some compensatory behaviours occurred among subjects in the control town hall. It is possible to imagine that subjects who wanted to learn more about democracy but were not catered to in the control town hall, were more likely to sign up for the newsletter than subjects who had just discussed for 45 minutes about democracy.

Democratic persuasion also had no discernible effects on the evaluation of the participating politician (−0.01 with p = 0.48), a pre-registered secondary outcome. This suggests that the treatment effects reported earlier are not simply driven by higher likability perceptions of the politician in the treatment condition. In exploratory analyses, we also find no evidence that persuasion effects would differ significantly by party alignment between politician and respondent or whether the treatment was delivered by a government or by an opposition politician (see online Appendix 10.12). Although we interpret this finding cautiously because the interaction between alignment and the treatment is underpowered, the absence of differential effects conditional on party alignment would not be surprising given that the democratic persuasion intervention did not emphasize partisan differences, and recent research finds that party supporters update their views even in the presence of party cues (Coppock, Reference Coppock2023; Tappin et al., Reference Tappin, Berinsky and Rand2023).

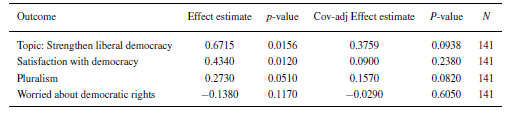

Finally, we estimate if effects decay over time. Results from a third survey wave, fielded around 1 month after the town halls, indicate that participants in the treatment group remain more likely to adequately recall that the democratic persuasion town hall focused on making the case for liberal democracy (Table 2). Moreover, there is some evidence that the positive effect on pluralistic attitudes lasted at least for 1 month, again with slight sensitivity to the analysis specification (covariate-adjusted p = 0.08, unadjusted p = 0.05).Footnote 5

Table 2. Effects on primary outcomes 1 month after the treatment

Discussion

This research explores methods to bolster citizen commitment to democracy during crises, introducing democratic persuasion as a practical, actionable intervention to strengthen the societal foundations of liberal democracy. Our field experiment provides mixed findings including tentative evidence that political elites can sway public opinion towards liberal democracy by engaging existing concerns while actively making the case for this system of government.

We observe null effects on petition signatures and newsletter sign-ups. Citizens who were randomly assigned to democratic persuasion expressed higher satisfaction with democracy, more strongly endorsed pluralist values and expressed fewer concerns about their rights and about the legitimacy of public health measures relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. This experiment and all analyses were pre-registered, and all effects went in the hypothesized direction. Some of the observed effects are sizable. Among participants who were dissatisfied with the democratic process during the COVID-19 crisis, exposure to democratic persuasion led to a change of mind of one in every seven citizens so that these citizens saw democracy in a more positive light after the town hall. Yet, as many of the estimated effects hover around the threshold of statistical significance, and as some group differences were measured with considerable noise, uncertainties remain about some of the reported findings.

The analysis suggests that while democratic persuasion shows promise in influencing democratic attitudes, its effects may diminish over time, with only one of three attitudinal changes enduring a month post-treatment. This could be understood as indicating the necessity for continuous engagement in democratic persuasion by pro-democracy legislators to ensure lasting attitudinal change among citizens.

While this study involved legislators from five political parties across different government levels in Germany, it focused solely on one country at one point in time. From a theoretical point of view, we expect the results to generalize to similar contexts, where citizens have experienced democracy for a sustained period of time, but where the liberal democratic system is under pressure from political actors that try to exploit apparent shortcomings by denying trade-offs and spreading misinformation. Scaling this intervention presupposes pro-democratic citizen predispositions and a majority of political elites supporting democracy. Its applicability is less clear in places like the United States, where politicians affiliated with one of the two main political parties regularly question the foundations of liberal democracy.

Another generalizability issue concerns the sample of town hall participants which was skewed towards educated citizens. Although this form of biased self-selection into political exposure resembles real-world mechanisms, arguments could be made for stronger or weaker persuasive effects among citizens with less formal education. While these questions deserve further study, it is important to note that democratic persuasion is not limited to town halls but much of its untapped potential might lie in mediated communication (e.g., Clayton & Willer, Reference Clayton and Willer2021), although one study of pre-recorded videos, where politicians appealed to Republican voters in the context of the 2021 Capitol riots in the United States shows null effects (Wuttke, Sichart, et al., Reference Wuttke, Sichart and Foos2024).

This study aims to inspire further exploration into academic-driven interventions to reinforce the foundations of liberal democracy. This experiment prioritized the authenticity of democratic persuasion within an ecologically valid online town hall setting, accepting limitations on isolating specific intervention components. Surveys or lab experiments provide more control over the administration of and compliance with interventions. For instance, experiments with greater sample sizes could test whether particular messages are more effective in specific segments of the population.

Our argument for democratic persuasion as a non-judgemental rhetorical strategy is based on the assertion that existing doubts and discontent often have at least some foundation in political and social reality. That means political communication can clarify misconceptions or highlight principles and trade-offs that were not apparent to citizens who do not spend their days thinking about the complexities of political institutions and processes. If politicians who support the liberal democratic system fail to act, the stage is left to politicians who attempt to seize upon concerns and anxieties of citizens and turn them against the liberal democratic order. Highlighting the potential value of democratic persuasion does not mean that political actors should abandon issue-based or election-driven persuasion as a goal, but they might engage in democratic persuasion alongside it. Since we do not find any apparent trade-off between democratic persuasion and issue-based persuasion (on social distancing measures), and no negative effects on trust in the representative, there are few drawbacks to engaging in this communicative strategy. At the same time, for a resilient democratic culture, political communication can only ever be one of many strategies that pro-democracy actors can pursue, others being the defence and strengthening of formal democratic institutions and delivery on policy commitments that benefit a majority of citizens (Diamond, Reference Diamond2020; Pappas, Reference Pappas2019; Runciman, Reference Runciman2018).

In a time when democracy is under pressure, it is worth recalling that an act of democratic persuasion stood at the outset of the American experiment of self-governance. The Federalist Papers were a document of political theory but also the deliberate attempt of political leaders to convince a hesitant public of the value of a republican constitution. Likewise, in Germany after the experiences of Nazism, the Holocaust and defeat in WW2, political science was refounded as democracy science to act on the insight that democracy cannot be taken for granted and that academics have a responsibility to promote democratic ideas among the citizenry (Zeuner Reference Zeuner1989). Now that liberal democracy has come under pressure again, as academics, it is worth taking up the tradition of political science as democracy science; and for political and social elites with some communicative power, it is worth taking up the tradition of democratic persuasion.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tim Andler, Stella Canessa, Len Metson, Florian Sichart and Olea Rugumayo for outstanding research assistance and WZB Berlin, and particularly Macartan Humphreys, for funding, support and feedback. We are also grateful for comments and suggestions that we received at the EPSA and EPOP 2021 annual conferences and the research seminars at the University of Vienna and Aarhus University. We thank Denis Cohen, Lala Muradova, Suthan Krishnarajan and Miriam Sorace for stimulating discussions.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: