1. Introduction

In this article, we revisit the question about the existence of the genitive alternation in Old English. The term genitive alternation, as applied to Present-Day English, refers to the alternation within the syntactic context of the noun phrase between a dependent noun phrase marked with ’s and a prepositional phrase headed by of for the marking of a range of entity-to-entity relations. For example, within a noun phrase headed by the noun bike, the semantic relation of ownership can be marked either by ’s, as in (1), or by an of-phrase, as in (2).

Researchers have sought to extend the scope from the Present-Day alternation to earlier times. Most research has focused on Late Modern English (seventeenth century and later), but Rosenbach & Vezzosi (Reference Rosenbach, Vezzosi, Sornicola, Poppe and Shisha-Halevy2000; also Rosenbach et al. Reference Rosenbach, Stein, Vezzosi, Bermúdez-Otero, Denison, Hogg and McCully2000; Rosenbach Reference Rosenbach2002) traced the alternation as far back as c. 1400 CE. For Old English (c. 650–1100 CE), a different alternation is studied under the name of ‘genitive alternation’, namely the alternation between pre-nominal and post-nominal genitives, which has been claimed as the Old English correlate of the Present-Day English genitive alternation (Anderson Reference Anderson2013; Cichosz & Grabski Reference Cichosz and Grabski2020; Ceolin Reference Ceolin2021).Footnote 1 It is, however, well-known that already in Old and Early Middle English some entity-to-entity relations in the noun phrase which were marked by genitive case morphology, from which ’s developed, could also be marked by prepositional phrases headed by of (Curme Reference Curme1913; Thomas Reference Thomas1931; Koike Reference Koike2004, Reference Koike2006; and especially Allen Reference Allen2003, Reference Allen2008, Reference Allen, Dufresne, Dupuis and Voca2009). The questions we seek to answer are whether the genitive alternation, defined as an alternation between an adnominal noun phrase marked with genitive case morphology or a diachronically related form like ’s (henceforth gen) and a prepositional phrase headed by the preposition of (henceforth of), can be found in Old English, and if it can, how it relates to the Present-Day English alternation.

One of the aims of this article is to develop a robust methodology for identifying the alternation in Old English corpus data. In the empirical part of our study, we conduct a series of targeted corpus searches in the York–Toronto–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose (henceforth YCOE, Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Warner, Pintzuk and Beths2003). We reach the conclusion that there is indeed alternation between of-phrases and genitive-case-marked noun phrases in the Old English noun phrase, and that this alternation is observed in at least some of the same semantic contexts as is the genitive alternation of Present-Day English. Hence, we argue that there is plausibly a continuous genitive alternation in English evident already in Old English. However, we also note significant changes, calling for an understanding of the alternation as affected by both stability and change.

Our study is part of a tradition of variationist studies of historical corpus data. The purpose of this study is not to conduct a statistical variationist analysis of the factors that explain the distribution of the alternants in contexts where both can in principle be used, i.e. choice contexts. Instead, it focuses on the preconditional challenge of establishing the existence and extent of these choice contexts in historical data. This is a particular problem for the genitive alternation, as the choice contexts are typically assessed on the basis of speaker judgements of semantic equivalence.

This article begins with a brief recap of existing studies of the genitive alternation and of the relation between gen and of with a particular focus on Old English, and considers issues for the establishment of alternations in historical data (section 2). Sections 3 and 4 explain how we identified alternation between gen and of in Old English corpus data, and present our findings, which are compared to the Present-Day English alternation. In section 5, we draw out generalizations about (dis)continuity in the history of alternations, and reflect on the methodology for identifying alternations in historical corpus data. Section 6 concludes.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. The diachrony of the genitive alternation

The main focus of genitive alternation studies has been on Present-Day English, with an expanding focus on the Late Modern English period (Altenberg Reference Altenberg1982; Rosenbach Reference Rosenbach2002; Wolk et al. Reference Wolk, Bresnan, Rosenbach and Szmrecsanyi2013; Biber et al. Reference Biber, Egbert, Gray, Oppliger, Szmrecsanyi, Kytö and Pahta2016; Szmrecsanyi et al. Reference Szmrecsanyi, Biber, Egbert and Franco2016). The main diachronic study going back further in time is Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2002), which identifies the Late Middle English period, c. 1400 CE, as the moment of emergence of this alternation.

With regard to Old English, Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2002: 177–8; summarizing from Rosenbach & Vezzosi Reference Rosenbach, Vezzosi, Sornicola, Poppe and Shisha-Halevy2000; Rosenbach et al. Reference Rosenbach, Stein, Vezzosi, Bermúdez-Otero, Denison, Hogg and McCully2000) states that the Present-Day English genitive alternation best corresponds in the Old English period to the variation between pre-nominal and post-nominal genitives, that is between Godes sunu and se sunu Godes, both ‘God’s son’. Position relative to the head noun is the alternating feature rather than the formal and morphosyntactic difference between gen and of. For Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2002: 233), the genitive alternation is only evident in the history of English once both the alternants have reached the status of clitic ’s and possessive marking of, respectively, with the transition from a case desinence to a clitic ’s being considered in greater detail than the development of of.Footnote 2 In other words, the genitive alternation is the specific alternation between the clitic ’s and of, shaped by factors like animacy and topicality, and only when both alternants and factors are in place can the genitive alternation be said to have begun. This is only true in the later Middle English period. An alternation between gen and of for Old English is also rejected based on the relative frequency of both forms: ‘the of-genitive has not yet been established as the major grammatical variant as opposed to the inflected genitive’ (Rosenbach Reference Rosenbach2002: 178).Footnote 3

Several scholars have, similarly, taken the view that the genitive alternation as it exists in Present-Day English simply does not exist in Old English, for the reason that only gen (and not of) can be used to mark certain types of adnominal dependents which are viewed by those scholars as definitional to the genitive alternation. For instance, Ceolin (Reference Ceolin2021: 2–3) states:

while in PDE [Present-Day English] [nominal] arguments are introduced either by the clitic ’s or the preposition of, in OE [Old English] they were always case-marked. Although OE already had the preposition of, this was limited to partitive readings, and therefore could not be used to express possession or to introduce arguments.

Instead, Ceolin (Reference Ceolin2021) treats the alternation between pre-nominal and post-nominal gen as the equivalent of the Present-Day alternation, because both of these forms are ‘genitives’ in the sense of marking possessive modifiers and nominal arguments. Anderson (Reference Anderson2013) and Cichosz & Grabksi (Reference Cichosz and Grabski2020) adopt a similar perspective, exploring the alternation between pre-nominal and post-nominal genitives in terms of factors like weight and animacy, explicitly drawing on research on the Present-Day English genitive alternation.

2.2. The competition between gen and of in Old English

The relation between adnominal noun phrases marked by gen and prepositional phrases headed by of has not only been studied by scholars intent on studying the genitive alternation. From the early twentieth century onward, studies of Old (and Middle) English morphosyntax have noted and discussed the fact that gen and of can appear in similar contexts in Old English (Curme Reference Curme1913; Thomas Reference Thomas1931; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1985: §1202, 1203; Allen Reference Allen2008; Taylor Reference Taylor2022). These studies consider the possibility of these two morphosyntactic forms appearing in similar contexts as part of a general interest in the change from synthetic to analytic expression of grammatical relations in the history of English. As an example, Nunnally (Reference Nunnally, Rissanen, Ihalainen, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen1992), who studies how the genitive-marked adnominal noun phrases in the Latin Vulgate are translated in the West-Saxon Gospel of Matthew, a Late Old English text, concludes that his study can also ‘shed light upon the question of whether OE [Old English] possessed a periphrastic genitive’, with his answer being unequivocally that it did not (Nunnally Reference Nunnally, Rissanen, Ihalainen, Nevalainen and Taavitsainen1992: 367).

The oldest study, Curme’s, argues for a different position, suggesting that already ‘centuries before the Norman French came in’ (Reference Curme1913: 165), of is in competition with gen, and that by the tenth century of ‘has developed perceptibly in the direction of becoming a mere substitute for the old synthetic genitive … not only in northern English but also in the literary language of the South’ (Reference Curme1913: 161). Allen (Reference Allen2008: 72–4; with reference to Mitchell Reference Mitchell1985: §1201, 1203) identifies some possible contexts for semantic overlap between Old English of and gen, including ‘examples in which of is used in a partitive sense where a genitive would undoubtedly be an alternative’.

There is thus some evidence for an alternation between gen and of in Old English, but it is limited in scope. Allen (Reference Allen2008) does not seek to provide a detailed exploration of the nature and frequency of those contexts, instead establishing primarily whether uses of of claimed to mark possession and part–whole relation by previous scholars can be counted as secure examples. Curme’s (Reference Curme1913) data set, being based exclusively on examples from Old English translations of the Bible and interlinear glosses of biblical texts, is relatively limited compared to what can now be compiled using electronic corpora. Many later studies discussing Old and Middle English (e.g. Mustanoja Reference Mustanoja1960; Koike Reference Koike2006; Allen Reference Allen2008; Rosenbach Reference Rosenbach2002, Reference Rosenbach2014) rely on Thomas’ (Reference Thomas1931) PhD study, which traced the relative frequency of pre-nominal gen, post-nominal gen and of-phrases in Old and Middle English poetry and prose, for frequency information rather than collecting this data afresh.

Limitations in the existing evidence to address our research questions are also shaped by the different research goals. Biber et al. (Reference Biber, Egbert, Gray, Oppliger, Szmrecsanyi, Kytö and Pahta2016) describe variationist and text-linguistic approaches, with the latter applying methods from corpus linguistics to the study of variants in historical texts, as ‘yield[ing] distinct, yet complementary, descriptions of grammatical change in the use of genitive constructions’ (2016: 374). Text-linguistic studies tell us about the changes in overall frequency of each variant individually, whereas variationist approaches are not concerned with this type of frequency information, but tell us how the relative frequency of the variants changes in contexts where both can be used. Our aim in this study is to use the YCOE corpus to investigate whether instances of competition could be argued to amount to choice contexts.

2.3. Studying the gen–of alternation in historical corpus data

Determining what the choice contexts are is a crucial part of any variationist study. This is obvious too from the great care that researchers investigating the genitive alternation take in explaining how they determine whether tokens are equivalent or interchangeable (for instance, Jankowski & Tagliamonte Reference Jankowski and Tagliamonte2014: 310–12; Szmrecsanyi et al. Reference Szmrecsanyi, Biber, Egbert and Franco2016: 4–6). Most commonly, for studies of Present-Day English, it is the researchers who decide this based on their usage intuition, relying on inter-annotator measurements to ensure reliability. This is the method which has been applied for Late Modern English too (Biber et al. Reference Biber, Egbert, Gray, Oppliger, Szmrecsanyi, Kytö and Pahta2016; Szmrecsanyi et al. Reference Szmrecsanyi, Biber, Egbert and Franco2016). However, this method becomes more problematic the further back in history one goes and impossible to justify for Old English. In fact, difficulties in determining choice contexts might explain the overwhelming focus of variationist studies of Old English on word order phenomena, notably VO and OV orders (Taylor & Pintzuk Reference Taylor, Pintzuk, Meurman-Solin, López-Couso and Los2012), ACC DAT and DAT ACC orders in the double objective construction (De Cuypere Reference De Cuypere2015a), pre-nominal and post-nominal adjectives (Grabksi Reference Grabski2020), as well as pre-nominal and post-nominal gen (see section 2.1). The question whether the two variants are equivalent simply does not arise. In this study, we explore whether targeted corpus searches can help to identify when and where different variants may be interchangeable and equivalent. In the remainder of this section, we provide a brief discussion of the premises behind the methodology we will explain and apply in section 3.

A study that more closely resembles ours in its goals is De Cuypere (Reference De Cuypere2015b), which set out to establish whether a prepositional phrase headed by to was already an alternative to a dative-case-marked indirect object with ditransitive verbs in Old English, as is the case for Present-Day English.Footnote 4

From a methodological perspective, the dative alternation can be isolated with the help of lists of Old English ditransitive verbs and the morphosyntactic annotation in the YCOE. Concretely, De Cuypere (Reference De Cuypere2015b: 3–4) uses part-of-speech and syntactic tags to identify verbs with two objects, one in accusative case and the other in dative case. This gives him a list of ditransitive verbs, which he supplements with other instances of known Old English ditransitive verbs from dictionary and grammar descriptions. This list can then be used to target these verbs in the alternating syntactic configuration, with one nominal phrase object and one prepositional phrase object that contains the preposition to. Footnote 5 The envelope of variation, i.e. the entire set of choice contexts, is restricted by the argument structure and semantics of the verbs for this alternation. For the genitive alternation, there is no set of lexical items that we can use to guide the corpus search; whether a noun can take a genitive-case-marked dependent is not necessarily determined by the semantics of the noun, and genitive-case-marked dependents are ubiquitous.

In order to study the genitive alternation in Old English, we thus need to design a systematic bottom-up corpus-based approach that works for the variants in Old English. We do not take the circumscription of choice contexts attested for later stages of English to apply to Old English, as several existing studies do (see section 2.1). The envelope of variation for the genitive alternation is often circumscribed using semantic relations that can be expressed with both ’s and of and those that cannot. Our study relies on semantic relations to map out the envelope of variation for Old English in a comparable way, without, however, excluding relations that are categorical, that is that do not allow for alternation, for Present-Day English.

The determination of choice contexts hinges on the notion of equivalence. Indeed, some of the differences in proposals as to when the genitive alternation emerges in English arise because of different understandings of what it means to say that of is a ‘genitive’ construction. In certain studies, when it comes to identifying or rejecting of as a ‘genitive’ and hence a potential alternant with gen, the status of of as a functional rather than lexical preposition seems to have equal or more importance than the particular semantic relations it can mark (see section 2.2). We found the discussion in Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2019), which contrasts semantic–pragmatic studies, which seek ‘full equivalence’ across all levels of meaning – truth-conditional, pragmatic, functional – with the ‘softer view of equivalence’ (Rosenbach Reference Rosenbach2019: 761), useful to define equivalence for the purposes of our study. Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2019: 761) further explains:

They [variationist studies] proceed from the observation that there are alternative ways of ‘saying the same thing’ within a speech community (Labov Reference Labov1972: 188) and then capture this sameness (i.e. equivalence) under the abstract notion of the linguistic variable. That is, the observation of variation logically comes first and testifies to the equivalence of alternating constructions in language usage. What matters is what speakers treat as ‘saying the same thing’.

For variationist studies, variants do not need to be completely semantically equivalent; it is sufficient that they are roughly semantically equivalent, and share some meaning component. The linguistic variable is typically rather abstract. Rosenbach uses the various ways to express future in English, e.g. will, be going to, be V-ing, as an example. They ‘share the meaning of FUTURE but differ in the expression of PREDICTION, INTENTION, PROXIMITY etc.’ (Rosenbach Reference Rosenbach2019: 762). She views the role of semantic–pragmatic studies as important in theoretically capturing what meaning is shared in order to define the linguistic variable, with the knowledge that such studies will provide a more comprehensive and in-depth semantic analysis of each individual variant. We take Rosenbach’s (Reference Rosenbach2019) discussion as a guideline in approaching the Old English data, insofar as we look for the ability to alternate in usage, and take the existing semantic descriptions of gen and of as our starting point in establishing whether there is rough semantic equivalence and therefore alternation in Old English.

Finally, it is necessary to be more precise as to the nature of the alternation we seek to identify. The goal of our method is to resemble the speaker-judgement applied to the Present-Day English genitive alternation as closely as possible.Footnote 6 Our starting point is an awareness from existing research (Allen Reference Allen2008; Taylor Reference Taylor2022) that gen and of can both be used in Old English to mark relations like subset. Our aim in data collection is to systematically assess the existence and scope of an alternation between gen and of across all possible semantic relations in Old English.

3. Finding the gen–of alternation in Old English corpus data

3.1. A methodology for identifying gen–of alternation

The data for our investigation comes from the York–Toronto–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Warner, Pintzuk and Beths2003), a 1.5-million-word corpus comprising Old English prose texts dating from the 700s to 1100s. The corpus has 97 distinct texts from a range of genres. Texts are categorized into one of four time periods; one time period (O1) covers texts up to 850 CE, and the remaining three cover 100-year periods until 1150 CE.

Our methodology for identifying alternation begins with one of the potential alternants. We targeted instances of of in the corpus, on the grounds that, of the two potential alternants, of is the less frequent in Old English, and hence offers a more manageable prospect for subsequent manual sorting and coding of corpus-retrieved data.

An automatic search using Randall’s (Reference Randall2010) CorpusSearch II retrieved 5,778 instances of prepositional phrases headed by of, from which those modifying a noun were identified manually. Manual identification of adnominal of was necessary as the syntactic governance of prepositional phrases in the YCOE is often underspecified insofar as the syntactic annotation provided in the corpus is not intended to be a claim about the governance of a particular PP. The ‘default’ and by far the most common annotation marks a PP as a modifier of IP, even in cases where a different dependency is justified and preferable, for example, where the PP is a verbal complement (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Warner, Pintzuk and Beths2003). Annotating the adjunction sites of prepositional phrases has been recognized as a significant challenge in corpus development in general. The majority of the 5,578 instances of of-phrases in YCOE was dependent on verbs; of-phrases were also observed dependent on adjectives and as dependents of other prepositions (see further Elenbaas Reference Elenbaas2014; Taylor Reference Taylor2022). These were discarded, leaving a data set of 515 examples of noun phrases with dependent prepositional phrases headed by of.

Having identified examples of of, the semantic relation marked by of in each of the 515 noun phrases was coded manually. The semantic relation marked by the of-phrase relative to the head noun in each noun phrase was coded in a two-stage process. Initial coding made use of a simple threefold taxonomy of entity-to-entity relations adapted from that used in Aikhenvald’s (Reference Aikhenvald, Aikhenvald and Dixon2012: 3–6) typological survey of possession marking. In this threefold taxonomy, relations are either core or associative. Core relations are further divided into part–whole relations, on the one hand, and relations typically considered under the umbrella of ‘possession’ (ownership and kinship), on the other.

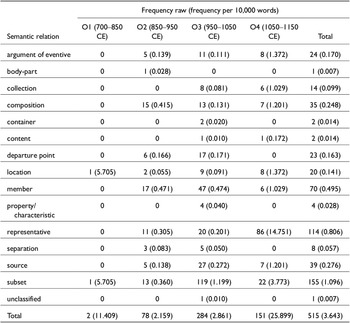

In our second round of coding, relations marked by of were further identified using a more fine-grained taxonomy, adapted from examples of specific relations given by Aikhenvald (Reference Aikhenvald, Aikhenvald and Dixon2012), from the semantic classification applied to uses of of-phrases in Present-Day English used by Payne et al. (Reference Payne, Pullum, Scholz and Berlage2013) and from accounts of the use of of by Mitchell (Reference Mitchell1985) and Middeke (Reference Middeke2021). The latter were needed as, even though Payne et al.’s taxonomy of relations is one of the most detailed and considered we have encountered, this proved in fact unequal to our needs, as of in Old English marks relations not listed by Payne et al. (Reference Payne, Pullum, Scholz and Berlage2013) for the Present-Day preposition. A full list of the relations identified as being marked by of is given in table 1, accompanied by short examples drawn from our data demonstrating what is meant by each relation and by basic frequency information.Footnote 7

Table 1. Frequency of semantic relations marked by adnominal of-PPs

The range of semantic relations marked by of during the Old English period is varied but considerably smaller than the range of relations marked by the Present-Day English preposition. As discussed in detail in Taylor (Reference Taylor2022), at this stage in the history of English, of was a lexical preposition rather than the functional preposition it would later develop into (see also Koike Reference Koike2004; Allen Reference Allen2008). We do not consider that the lexical status of Old English of is a barrier to exploring alternation, considering alternation as we do as a question of choice contexts rather than functional equivalence (see section 2.3).

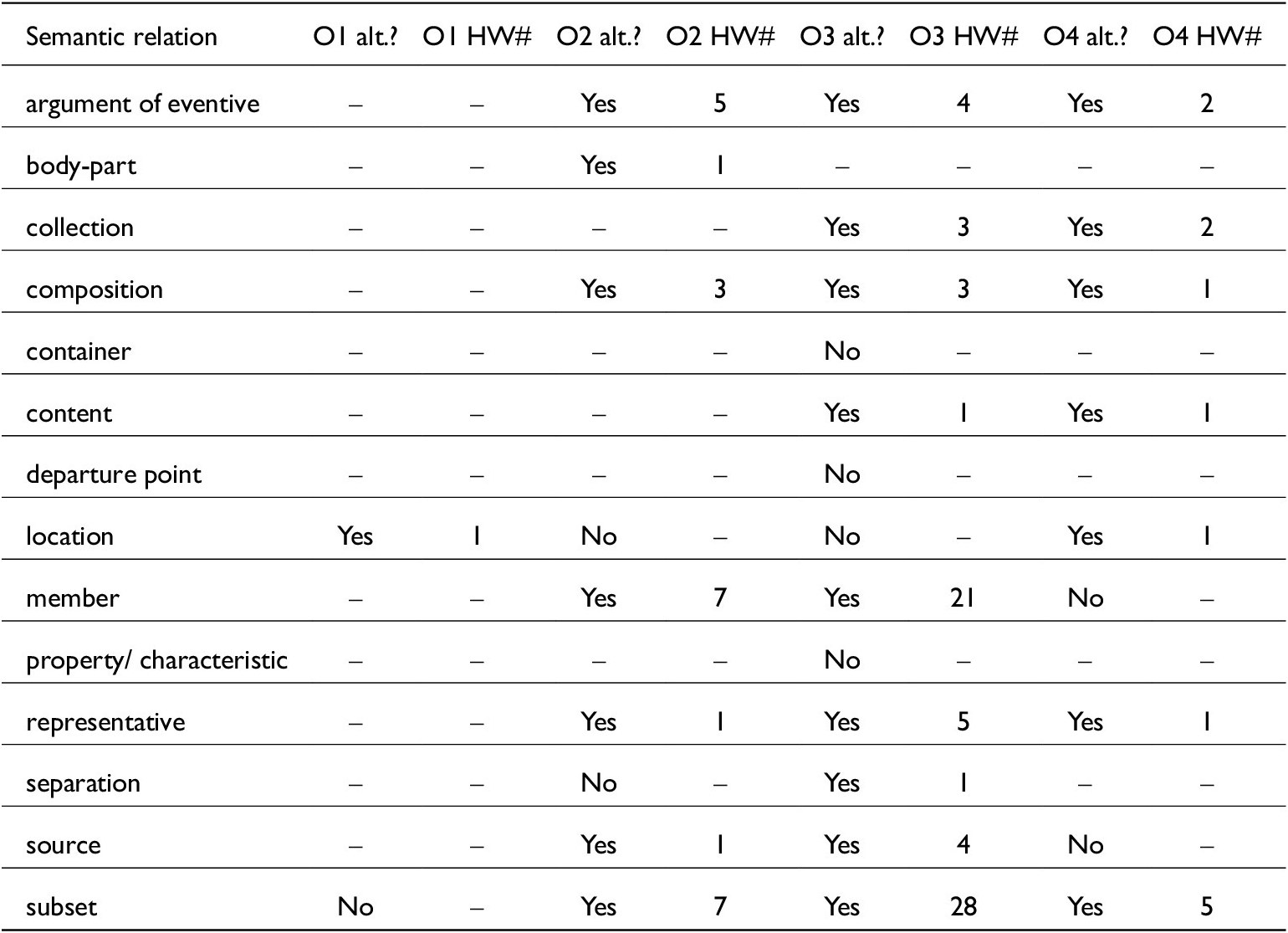

Table 2 gives more detailed frequency information by period. Broadly speaking, there is stability between the O2 and O3 periods, i.e. over the 200 years 850–1050 CE, followed by an increase in the use of of in the majority of relations in period O4, from 1050–1150 CE.

Table 2. Raw and relative frequency (per 10,000 words) of semantic relations marked by adnominal of-PPs

With examples of adnominal of-phrases coded for the semantic relation marked by of, the next step in our data collection was the identification of examples of gen in alternation with of. This means identifying instances where an adnominal genitive marks one of the semantic relations already observed marked by of. The identification of genitives ‘marking the same semantic relation’ was operationalized in the first instance by head noun: we searched the corpus by isolating examples of gen with the same head noun as occurred in our set of corpus-retrieved noun phrases with of, and searched within these examples for instances of gen with the same (or a closely synonymous) dependent noun and marking the same relation(s) as of marks with that head noun. Where noun phrases with exactly the same head and same dependent noun were not found, we expanded our search targeting noun phrases with gen in which either the head noun or the dependent noun was synonymous with those observed in our data with of.

In practice, this meant automatically retrieving all noun phrases with an adnominal genitive from the YCOE, and then semi-automatically searching this file for a given head noun, with spelling variants. Examples of noun phrases with the targeted head noun and an adnominal genitive were then manually searched to identify those with the same or synonymous dependent noun, and examined to determine the semantic relation marked by gen. As illustrated with the worked example below, ‘synonymy’ is operated in context: it was assessed for the nouns in the corpus data individually rather than taken in the strict sense.

The process of searching the corpus for instances of gen that alternate with of is explained with reference to (5) and (6). The head noun of the relevant noun phrase in (5) is eowd ‘flock’, the dependent noun is man ‘man’ and the relation marked was classified as a collection relation.

Our corpus-retrieved file of all noun phrases with an adnominal genitive was searched for the noun eowd. Footnote 8 Spelling variants like eowod, eowed were identified using lexicographical resources (Cameron et al. Reference Cameron, Amos and diPaolo Healey2024), and these variants were also searched for. The search retrieved 17 examples of the noun eowd with an adnominal genitive. Of these examples, three had dependent nouns which like that in (5) referred to groups of men – gebroðor ‘brother’ and the third-person plural pronoun heora. All of these three noun phrases were identified as examples in which gen marks the collection relation; (6) is one.

In order to identify alternation, examples of gen marking the same relations as marked by of – with sameness operationalized by head nouns and dependent nouns – were sought in the same texts, or, failing this, in texts by the same author or, failing this, texts from the same YCOE period as our corpus-retrieved examples of of. In the case of the collection relation with eowd just discussed, (5) and (6) are not from the same text, but are from different texts from the same 100-year period, 950–1050 CE (O3). Examples from other periods were recorded during data collection, but are not counted as examples of an alternation in our presentation of the data.

It is at this point that our methodology for establishing whether or not an alternation exists in a historical data set makes explicit our assumptions about the nature of an alternation. By seeking examples within the same text or in texts by the same author or in texts from the same period, we operationalize the assumption that an alternation constitutes a choice context for a contemporary language user, in this case both an ‘author’, as well as a roughly contemporary language user living in a given 100-year period. The latter can be thought of as similar to a researcher assessing equivalence for Present-Day (and Late Modern) English.

A privileging of noun phrases with the same head noun and same dependent noun (or with either a synonymous head or a synonymous dependent, but not both) reduces the risk that differing identification of semantic relation will lead to debate as to whether or not an alternation between of and gen is actually observed in a given semantic context. To some extent, focusing on the same head and dependent noun means that whether or not our identification of a given semantic relation as ‘composition’ or ‘membership’ is universally accepted, the presence of an alternation between of and gen in marking the relation between head x and dependent y – however it might be classified – holds. There are, of course, instances in which same head and same dependent does not equate to same semantic relation; even in our relatively small data set of examples of of, we observe that the relation holding between the head noun folc ‘people’ and dependent nouns that are proper noun place names was, in one example, that of location, and, in another, that of representative.Footnote 9 Nonetheless, our targeting of head nouns maximizes the opportunity for identifying alternation in a data set of adnominal genitives which is otherwise unmanageably large, at over 58,000 noun phrases, for manual coding of semantic relations. Additionally, searching for noun phrases by way of their head noun allows for the identification of relations marked by gen other than those which have been typically discussed in the literature as relations for which the genitive case can be used.

3.2. Contexts for gen-of alternation in Old English

We have used a conservative method for identifying alternation, restricted by the range of semantic relations and head nouns found in the data for of. There are no doubt other examples of gen, with other head nouns, that mark the semantic relations we identified in the examples of of. We have not looked into the frequency with which gen expresses these relations. The method followed provides us with a principled basis for assessing the question of the existence and scope of the genitive alternation in the data.

Table 3 gives a summary of where, in terms of semantic relations and periods of Old English, any example of alternation was identified. The number of different head words found is also given, to provide some sense of the evidence of the alternation per semantic relation in each period. A full list of the different head words observed is provided in Appendix 1.

Table 3. Alternation observed between gen and of, and the number of distinct headwords (HW#) for which alternation is observed, by period and semantic relation

The relations attested with the greatest number of head nouns across multiple periods are subset and membership relations. The evidence for other relations, notably separation and body-part relations, is weak. This reflects the low frequency of of, being the least frequent alternant and hence the limiting factor on the total number of examples with either alternant, and the low number of distinct head words for these relations.Footnote 10 We are mindful of the fact that frequency of both alternants is an important factor in the establishment of an alternation (see e.g. Jankowski & Tagliamonte (Reference Jankowski and Tagliamonte2014: 310–12) on the practice of excluding near-categorical contexts in variationist studies in the context of the genitive alternation), and of the fact that lack of frequency was a reason for some researchers to argue against the existence of the genitive alternation in Old English (see section 2). However, the specific relations that are attested compel us to view our data as part of the genitive alternation, as we will explain in section 3.3. Borrowing De Cuypere’s (Reference De Cuypere2015b) characterization this could be considered the incipient stage of the alternation.

Taking into account the number of examples of of, the number of head nouns and the number of different periods for which the alternations are observed, we proceed with our discussion on the cautious basis that an alternation can be suggested for the marking of arguments of eventives – which includes the specific relations of agent, theme and stimulus – composition, membership, representative and subset relations. These relations constitute the choice contexts for the genitive alternation in Old English. Illustrative examples of the alternation for these relations are given in (7)–(16).

Subset

Membership

Argument: agent

Representative

Composition

It can further be noted that no lectal factors seem to emerge from our data (see Pijpops et al. Reference Pijpops, Franco, Speelman and Van de Velde2024). Alternants are found within the same text, within texts by the same author, within texts of the same dialectal provenance and within texts of the same genre.

3.3. Comparison with the Present-Day English alternation

Several of the semantic relations for which an alternation between gen and of has been identified in Old English by this study are semantic relations which do not feature in the genitive alternation in Present-Day English. Composition, subset and membership relations are marked exclusively by of in Present-Day English. These relations cannot be marked by the ’s-alternant, as demonstrated for composition by (17)–(18), for subsets by (19)–(20) and for membership by (21)–(22).

There does exist some overlap between the alternation of of and gen in Old English and the Present-Day English genitive alternation. This overlap lies in the marking of the representative relation and the arguments of eventive noun phrases, specifically the relations of agent, theme and stimulus. In Present-Day English it is possible to mark these semantic relations using either the ’s-variant or the of-variant, as (23)–(24) for representatives, (25)–(26) for agents, (27)–(28) for stimuli and (29)–(30) for themes demonstrate. All examples are taken from the British National Corpus (2007), henceforth BNC, and were accessed via the BNCweb interface.

There is hence the possibility of a continuity between Old English and Present-Day English in terms of alternation between gen and of in the representative relation and in the three argument relations of agent, stimulus and theme.

Eventive noun phrases have often been either excluded from variationist and historical studies of the genitive alternation (Rosenbach Reference Rosenbach2002: 122; Feist Reference Feist2012: 283–4; contrast Szmrecsanyi et al. Reference Szmrecsanyi, Biber, Egbert and Franco2016: 5) or treated as a special case (Allen Reference Allen2008; Wolk et al. Reference Wolk, Bresnan, Rosenbach and Szmrecsanyi2013: 398), on the grounds that the semantic relations linking participants to events sit outside whatever taxonomy of semantic relations is adopted in a given study (Wolk et al. Reference Wolk, Bresnan, Rosenbach and Szmrecsanyi2013). Sometimes, too, it has been suggested that interchangeability between gen and of is not possible in eventive noun phrases (Feist Reference Feist2012: 283–4). This previous lack of interest in eventive noun phrases as a choice context for the genitive alternation prompted us to further look into the alternation between gen and of in Old English for the semantic relations of agent, theme and stimulus.

4. The genitive alternation and the marking of arguments

4.1. Marking arguments of eventive nouns in Old English

A corpus search of YCOE for noun phrases headed by the same eventive nouns as were observed in contexts for the alternation between gen and of – namely, andetness ‘confession’, gitsung ‘coveting’, herung ‘praising’ and tyhting ‘persuasion’ – reveals that for one such head noun, gitsung ‘coveting’, there is a more abundant alternation in the marking of the semantic relation of stimulus than one limited to gen and of. For example, there are noun phrases headed by gitsung with a dependent on-phrase marking the stimulus relation in the corpus, one of which is provided in (31).

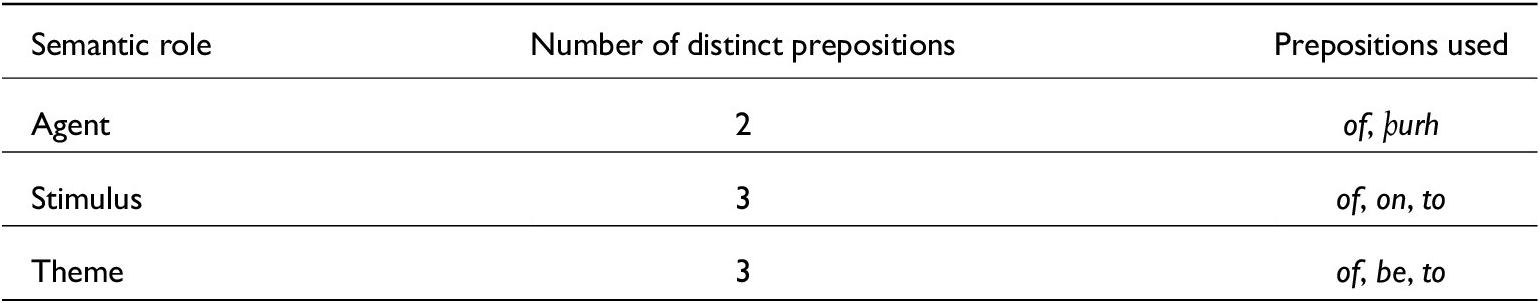

In order to explore the possibility of multiple alternating prepositions further, data was retrieved from the YCOE corpus pertaining to other eventive noun phrases headed by nouns not observed with of using the morphological markers of eventive nouns derived from verbs, namely the suffixes -ung and -ness. Manual classification identified the morphosyntactic means by which the semantic relations of agent, stimulus and theme, i.e. those semantic relations identified as contexts for the alternation between gen and of, were marked in the noun phrase. This data confirmed that several prepositional phrases beyond of are used to mark these semantic relations in Old English, and that there is alternation between gen and these other prepositional phrases in the marking of these three relations. In total, there are five different prepositional phrases observed in alternation with gen: of-phrases, be-phrases, on-phrases, to-phrases and þurh-phrases, as outlined in table 4.Footnote 12

Table 4. Prepositions marking agent, stimulus and theme

By identifying a number of prepositions other than of which are part of the alternation of gen and of, our findings are in line with various studies investigating polynary case-preposition alternations in verbal argument structure, like Zehentner (Reference Zehentner2017, Reference Zehentner2019, Reference Zehentner2021) outlining the double object construction and its various prepositional competitors in Middle English, and Middeke (Reference Middeke2021) identifying multiple alternations with more than two alternants involving case and prepositions in the context of the argument structure of Old English verbs.

4.2. Comparison with the Present-Day English alternation

Some recent studies of the genitive alternation in Present-Day English have questioned whether the genitive alternation involves only two alternants, ’s and of, or whether further alternants need to be included. This is an important question in variationist studies on account of the Principle of Accountability, one element of which is that a variant should be studied in relation to all variants with which it competes in the context of the linguistic variable (Labov Reference Labov1969: fn. 20). Building on the pioneering research of Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2006, Reference Rosenbach2007), studies, in particular those addressing Late Modern English, propose and model a ternary variation involving adnominal nouns as third variant in the alternation, e.g. the BBC director vs the director of the BBC vs the BBC’s director (Biber et al. Reference Biber, Egbert, Gray, Oppliger, Szmrecsanyi, Kytö and Pahta2016; Szmrecsanyi et al. Reference Szmrecsanyi, Biber, Egbert and Franco2016). Yet Szmrecsanyi et al. (Reference Szmrecsanyi, Biber, Egbert and Franco2016: 25–6) acknowledge this may be only the tip of the iceberg, with prepositional phrases headed by prepositions other than of mentioned as further variants, without exploring this suggestion in detail.

In the context of our findings for Old English, it seems pertinent to at least cursorily assess whether Present-Day English allows for other prepositions to mark arguments of eventive nouns. An exploratory search of the BNC using individual lexical items reveals a small number of suggestive examples, illustrated in (32)–(37) for the patient relation of the noun invasion. As well as ’s (32), (proper) noun modification (33) and an of-phrase (34), this semantic relation is observed marked by an into-phrase (35), an on-phrase (36) and an upon-phrase (37). In Present-Day English, of is a functional preposition, yet the prepositions into and upon at least are lexical.

It is up to future research to reveal the extent to which there is polynary alternation between gen and of and other alternants, including other prepositional phrases in Present-Day English. In both Old and Present-Day English there is some evidence for alternation between lexical and functional prepositions, which is another avenue for further future exploration.

5. Studying the genitive alternation in historical data

5.1. The diachrony of the genitive alternation

The genitive alternation is usually traced back to c.1400 CE. Based on our findings, we put forward the possibility of a continuous alternation between Old English and Present-Day English in at least some semantic contexts. In addition, other contexts in which the Old English alternation is observed, but which are not contexts for the Present-Day alternation, namely composition, subset and membership relations, are nevertheless marked by one of the alternants of the Present-Day English alternation, of. This suggests that the contexts of alternation evident in Old English for gen and of have been, in some instances, joined by additional contexts in Present-Day English (e.g. kinship relations), in other instances, carried forward into Present-Day English (e.g. representative relations), and, in still further instances, removed from the envelope of variation (e.g. subset relations). Putting Old English and Present-Day English side-by-side, what emerges is a changed envelope of variation, changed both by expansion and contraction in respect of different semantic relations. The nature of the variation can be linked to the distinct meaning of gen and of in the two periods, in particular, of being a lexical preposition as opposed to a functional one. For Old English, semantic relations can be used to determine the envelope of variation, likely because the semantics of of is a main determinant for interchangeability. However, for other periods, other features may be key: for instance, Rosenbach (Reference Rosenbach2007) proposed that animacy can be used to define the emerging variation between the ’s-genitive and noun modifiers in Late Modern English.

Even though gen and of are central to the alternation in Old and Present-Day English, it appears that polynary alternation is neither a historical feature nor a recent development, but an ongoing dimension to this alternation. For Old English, at least one set of alternants are other lexical prepositions like on; for Late Modern and Present-Day English, noun modifiers have been recognized as a third alternant. The existence of a pronominal alternant of the type John his horse / Caroline her horse, has further been recognized for Middle and Early Modern English (Allen Reference Allen2008: ch. 6). However, it is likely that this only scratches the surface; the search for other alternants, for example adjectival modification, e.g. the Belgian capital is a major – and challenging – item on the to-do list in the field (see also Szmrecsanyi et al. Reference Szmrecsanyi, Biber, Egbert and Franco2016: 25–6). What the suggestion of a continuous plurality of alternants entails is that the possibility of polynary alternation needs to be taken seriously as a facet in the alternation between gen and of, in any period, whether approached synchronically or diachronically.

Our findings point to a complex history of continuity and discontinuity, and of waxing and waning in terms of alternants and envelope of variation. These findings are line with Zehentner’s (Reference Zehentner2017, Reference Zehentner2019, Reference Zehentner2021) work on the dative alternation. She observed that alternants can not only be gained, but also lost, and that the choice contexts between them can decrease or disappear completely over time, and she models this in a Construction Grammar framework and in terms of competition between forms.

5.2. A bottom-up approach to identifying alternations in historical data

At the end of the article, we consider the main take-aways from our effort to study the genitive alternation in Old English corpus data. In order to investigate alternations in their full complexity in historical periods, a bottom-up approach is needed. It is not enough to look for a replication of the Present-Day English alternation, limiting one’s methodology to targeting choice contexts and meanings relevant to the Present-Day English alternation. Approaching Old English noun phrases from the starting point of the genitive alternation in Present-Day English entails excluding precisely those contexts in which the alternation is in fact observed in Old English.

Debates about competition and functional equivalence between genitive case morphology and of-phrases in Old English prompted us to revisit the question about the genitive alternation in Old English. But we adopted a looser definition of equivalence, in line with variationist work on the genitive alternation, for our corpus study. We used interchangeability as a criterion, meaning that the lexical preposition of can alternate with gen.

The identification of alternation and choice contexts started from the exhaustive sampling of one of the alternants, in our case of. We then used semantic relations to map out the semantic space of of. A similar exhaustive sampling of gen was not feasible, and we therefore used the nouns and in particular the head noun as reference point. This not only helped with the amount of the data points, but also put the analysis on a more robust evidence base than just assessing semantic relations for a variety of English that is removed from ours in time. We used semantic relations found in this way for gen to capture the envelope of variation.

With this method, we established the existence of alternating examples, the envelope of variation and, in a subsequent step, also the existence of possible further alternants. Once this is done, the next step could be to conduct a variationist study of the factors determining the choice of alternants, starting with the identification of all examples of gen within the envelope of variation in a representative sample. Of course, given the small numbers of examples for of in Old English, this type of analysis is not possible. However, the methodology we have set out can be applied to later data periods, allowing us to track the shape of the genitive alternation over time, and identify periods in which both alternants are frequent enough to conduct further analysis. More generally, we think our methodology offers a fruitful means of identifying an alternation for which the choice contexts are not known or are in need of re-examination.

6. Conclusion

We have argued that there exists alternation between gen and of in Old English which is plausibly a direct forerunner of the genitive alternation of Present-Day English. This challenges claims that pre- versus post-nominal gen is the genitive alternation in Old English, and that it is not until c.1400 CE that the Present-Day alternation starts to develop. We proposed that the diachrony of the genitive alternation not only has a longer time depth, but is also more complex than previous studies have suggested. It is characterized by continuity and discontinuity of the alternants and waxing and waning of the envelope of variation. We used a new, bottom-up methodology to identify possible alternation and map out the envelope of variation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the audience at ICHL25 in Oxford and ICAME45 in Vigo for their feedback on earlier versions of this article. We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, and to the editor for her further suggestions and encouragement.

Appendix

Table A1. Headwords for which alternation is observed, by period and semantic relation