1. Introduction

The influence of financial motives, markets, and investors on health services provision has strongly increased in recent decades (OECD, 2024). Since the 1990s, market-oriented reforms have reshaped healthcare provision, driven by promises of efficiency, competition, and enhanced patient choice. Policies such as the separation of funding and service delivery, performance-based reimbursement, and diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment models have facilitated the expansion of private for-profit ownership in healthcare provision (Molinuevo et al., Reference Molinuevo, Fóti and Kruse2017). Unlike public or non-profit organisations, private for-profit entities allocate a share of their surplus (revenues minus expenses) to shareholders and/or other investors (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014). While private sector involvement has long been embedded in social health insurance (SHI) systems such as Germany and the Netherlands, internal market reforms have also expanded its role in National Health Systems (NHS), such as Italy and the UK (Montagu, Reference Montagu2021).

The involvement of for-profit private investment in health services provision and its impact on access, quality, efficiency and costs is a contentious social and political issue worldwide, reflecting significant variations in private sector investment-ownership across countries (Chalkley & Sussex, Reference Chalkley and Sussex2018). Previous literature has investigated the link between ownership – whether public, for-profit, or non-profit – and health system outcomes (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023; Goodair et al., Reference Goodair, Bach-Mortensen and Reeves2024). From an economic perspective, private investors can help address major challenges in the healthcare sector by increasing providers’ access to capital, promoting competition, and fostering innovation (Barros et al., Reference Barros, Brand, Maeseneer, Jönsson, Lehtonen and McKee2015). However, depending on their organisational objectives, the presence of private investors can also pose risks.

For financial reasons private investors may engage in undesirable but profitable practices, including supplier-induced demand, undue price increases, cost-cutting at the expense of care quality, and cherry-picking of the most profitable patients and services (Heins et al., Reference Heins, Price, Pollock, Miller, Mohan and Shaoul2010). These risks increase when health policy fails to correct the agency problems caused by the presence of asymmetric information and misaligned financial incentives. Furthermore, competition authorities have raised concerns over the growing consolidation of the healthcare market across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, calling for further investigation to better assess its implications (OECD, 2024). This includes the emergence of ‘too big to fail’ providers and ‘care deserts’, whose scale may limit regulatory leverage and create pressure for state support in the event of failure.

In general, mitigating the risks of private for-profit investment in, and ownership of, healthcare providers requires a robust regulatory framework and, for those included in state purchasing arrangements, effective contracts (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023; Heins et al., Reference Heins, Price, Pollock, Miller, Mohan and Shaoul2010). While governments implement a range of interventions – including entry barriers, oversight mechanisms, and contractual agreements – to influence the structure, conduct and performance of private providers, these frameworks inevitably contain gaps that can be exploited by investors to increase profits. Striking this balance requires careful consideration of the capacity of government to intervene effectively and its tolerance for risks related to private investor-ownership in the healthcare market.

A key policy question is how policymakers can encourage investors that have objectives and incentives aligned with social goals while curtailing the influence of others, whose activities may undermine key health system objectives, such as equity of access and quality of care.

The role of private sector investment-ownership in healthcare and their impact on service delivery remain subjects of polarised policy debate (Chalkley & Sussex, Reference Chalkley and Sussex2018). Research on the different forms of investor-ownership and the implications of this for public policy – particularly in European countries – remains limited (Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Schulmann, Tille, Rice, Mercille, Timans, Allin, Dottin, Syrjälä and Sotamaa2025). While existing literature largely focuses on private equity firms in the US (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023; Kannan et al., Reference Kannan, Bruch and Song2023; Unruh & Rice, Reference Unruh and Rice2025), private investment in healthcare is more diverse, with different ownership models operating under distinct regulatory systems, giving rise to different incentives. Without a nuanced understanding of the diverse configurations of private investor-ownership and regulatory models across countries, it is impossible to engage in informed policy analysis.

Understanding these variations is critical to identifying both the opportunities and risks associated with different investment-ownership models, particularly in determining whether different types of investors have equally strong incentives to pursue positive or negative behaviours that may affect purchasers and patients.

Therefore, this paper aims to (i) present a typology that categorises the different types of private investor-ownership in health service provision, by drawing on principal-agent theory; (ii) examine their strategic, operational, and financial incentives in the healthcare market to identify risks and opportunities associated with each investor-ownership type; (iii) present a comparative case study of five countries (the UK, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and the US), mapping current private investor-ownership models, reviewing current regulations directed at private investor-ownership, and assessing the existing evidence on the effectiveness of these regulations; and (iv) provide an overview of key overarching lessons and recommendations for policymakers.

2. Method

A literature search was conducted to identify relevant domains for developing a typology of private investor-ownership models in health service provision and to examine regulatory frameworks governing private ownership across the five jurisdictions mentioned above. We searched Google Scholar for peer-reviewed literature and supplemented this with targeted grey literature searches using Google to capture policy documents and regulatory materials not available through academic databases. Our search strategy encompassed three primary areas of inquiry (i) health economics literature examining ownership structures and competitive dynamics in healthcare markets, which informed our understanding of the economic context; (ii) corporate finance and private equity scholarship, which provided the conceptual foundation for defining ownership domains within our typology; and (iii) empirical studies investigating the relationship between ownership configurations and healthcare outcomes.

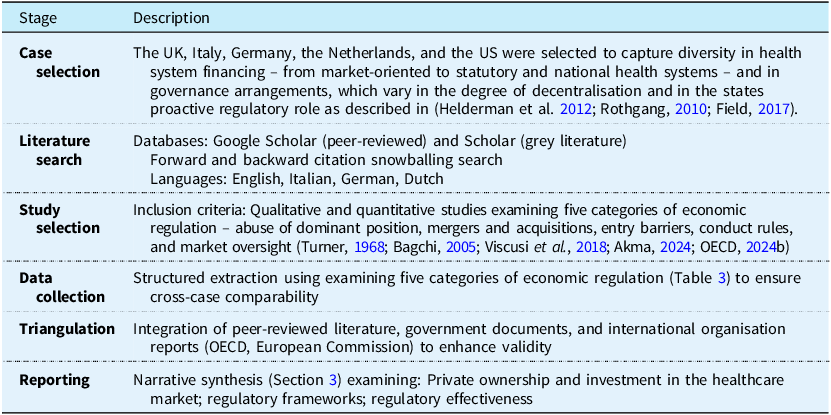

The typology was constructed using three theoretically and empirically informed a priori domains (strategic, operational, and financial) identified as key determinants of investors’ behaviour and incentives in previous literature (Kaplan & Stromberg, Reference Kaplan and Stromberg2009; Arora & Purohit, Reference Arora and Purohit2024; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Munnich, Richards, Whaley and Zhao2023; Matthews & Roxas, Reference Matthews and Roxas2023; Schoenmaker & Schramade, Reference Schoenmaker and Schramade2023). This tripartite classification reflects established understanding of how ownership structures shape organisational objectives and performance in healthcare delivery systems. For the case study analysis, we follow a six-steps approach (Table 1), including case selection, literature search, study selection, data collection and analysis, data triangulation and reporting (Ebneyamini & Sadeghi Moghadam, Reference Ebneyamini and Sadeghi Moghadam2018; Goodrick, Reference Goodrick2020).

Table 1. Case study analysis – six steps

3. Developing a typology of private investor-ownership in the market for healthcare provision

This section outlines a typology that categorises the different types of private investor-ownership in health service provision, examining how ownership shapes incentives in the healthcare market. Unlike previous typologies, which have primarily examined public and private providers within health systems and different forms of privatisation (Cortez & Quinlan-Davidson, Reference Cortez and Quinlan-Davidson2022; Molinuevo et al., Reference Molinuevo, Fóti and Kruse2017; Montagu, Reference Montagu2021), our focus is on the nature of ownership as conferred by the nature of equity investment in healthcare provision. Our analysis focuses on investor ownership of private health service providers, including of virtual health care services, and therefore excludes producers, distributors, or retailers of medical equipment, devices, such as digital health technologies and pharmaceuticals.

By distinguishing between different ownership and investment models, we aim to provide a more granular understanding of the various forms of private investor-ownership in health service provision. This framework offers a more nuanced perspective on the objectives and incentives of private investors identifying risks and opportunities associated with each investor-ownership type and highlighting the implications of different ownership structures for healthcare outcomes such as equitable access, quality, efficiency, and cost.

3.1 Economic background

In real-world healthcare markets, the assumptions of perfect competition – such as perfect information and free entry – are systematically violated. Under conditions of market failure – including information asymmetry, incomplete regulation, and contractual incompleteness – ownership becomes a key determinant of provider behaviour (Arrow, Reference Arrow1963; Chalkley & Sussex, Reference Chalkley and Sussex2018; Heins et al., Reference Heins, Price, Pollock, Miller, Mohan and Shaoul2010; Shleifer, Reference Shleifer1998). The complexity of healthcare services renders it impossible to specify every aspect of quality and delivery in contractual agreements (Chalkley & Sussex, Reference Chalkley and Sussex2018). Patients cannot function as fully informed consumers, and contracts established by public authorities or purchasers – acting as their agents in the market – are inherently incomplete. Consequently, in practice ownership represents a critical driver of provider behaviour. Close attention must therefore be paid to how for-profit entities respond to market failures, and to the potential for such responses to compromise healthcare outcomes.

Hence, institutional arrangements within the healthcare market regulating the providers’ entry and behaviour are crucially important. Due to their distinctive characteristics – such as clarity of objectives, including profit maximisation, and pressures on organisational and managerial performance from shareholders and creditors – private investors tend to prioritise financial returns. They often operate under hard budget constraints, meaning that failure to generate adequate profits eventually leads to insolvency. As a result, they may exploit market failures, engaging in behaviours such as supplier-induced demand, cherry-picking of profitable patients and services, quality-shading, and the externalisation of costs onto the public system (Heins et al., Reference Heins, Price, Pollock, Miller, Mohan and Shaoul2010).

3.2 A typology of private investor-ownership and their incentives

Our typology (Table 2) distinguishes between five ownership models in health service provision: non-profit, sole proprietor and partnership, shareholder ownership (in the form of a public corporation), venture capital (VC), and private equity (PE). For each type, by defining eight attributes, the framework highlights how different investor-ownership types shape strategic (ownership structure, investment horizon, growth orientation); operational (role of investors in provider management, extent of public transparency); and financial (capital structure, access to external capital, profit focus) incentives in the healthcare market (Schoenmaker & Schramade, Reference Schoenmaker and Schramade2023, Chang, Reference Chang2023, Eckbo, Reference Eckbo2007).

Table 2. A typology of private investor-ownership in the healthcare sector

Our typology shows that PE-owned provider organisations, which are highly responsive to investor expectations, tend to exhibit highly leveraged capital structures, with debt typically borne by the acquired asset, in contrast to other investor–owner types. This introduces an element of financial fragility into the healthcare network and raises the potential for a ‘too big to fail’ scenario. PE ownership also entails an aggressive focus on profit maximisation within a short investment time-horizon (Eckbo et al., Reference Eckbo, Phillips and Sorensen2023). In contrast, other forms of investor-ownership of corporates, such as public corporations, are marked by less aggressive emphasis on short-term profits, more gradual growth orientation, and less direct involvement in strategic, operational, and financial decision-making. These differences also extend to levels of public transparency. While Public Limited Companies (PLCs) are subject to the highest disclosure requirements due to securities regulation, PE and VC firms, as well as sole proprietors, operate with minimal obligations for public financial reporting, limiting external oversight and accountability (Table 2).

Notwithstanding the different objectives, capital structures, and profit strategies defining the different forms of ownership, all private healthcare entities – including non-profits – may be incentivized to exploit regulatory gaps, contractual incompleteness, and information asymmetries, including those between providers and patients, and providers and purchasing agencies. However, these incentives are typically more pronounced for some ownership forms than for others – in particular, PE firms, and potentially VC investors, due to their stronger financial return imperatives and shorter investment horizons – are a priori most likely to respond sensitively, and opportunistically, to any such lacunae.

PE firms are motivated to aggressively pursue short-term returns because the dominant performance metric (Internal Rate of Return; IRR) disproportionately overvalues cash flows received in the early years of an investment (Phalippou, Reference Phalippou2020; Reference Phalippou2025). This reliance on a gameable and misleading metric can distort investor expectations and drive strategies that undermine long-term outcomes, with potentially significant implications for the provision of healthcare services.

3.3 Ownership structures and healthcare outcomes

While economic theory suggests that private entities can foster competition innovation, efficiency, and enhance consumer choice in the healthcare sector, close attention should be paid to how private investors respond to market failures, and the potential for such responses to undermine equity, access, and quality of care (Chalkley & Sussex, Reference Chalkley and Sussex2018; Heins et al., Reference Heins, Price, Pollock, Miller, Mohan and Shaoul2010; Barros et al., Reference Barros, Brouwer, Thomson and Varkevisser2016). Previous studies have shown that investor-ownership types might significantly affects healthcare delivery outcomes. For instance, while for-profit providers (including PE) have being found highly effective at providing cost-efficient care (Beyer et al., Reference Beyer, Demyan and Weiss2022), PE ownership has been consistently associated with both increased costs to patients or payers and some harmful impacts on quality and access (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023; Cerullo et al., Reference Cerullo, Yang, Roberts, McDevitt and Offodile2021; Matthews & Roxas, Reference Matthews and Roxas2023; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Cardenas, Torabzadeh, Whaley and Borkar2025). The highly leveraged financial structures typical of PE firms have also been found to pose risks to operational sustainability and patient safety (Karamardian et al., Reference Karamardian, Jagtiani, Chawla and Nembhard2024).

The effects of investor-ownership types might highly context-dependent, shaped by variations in local market structures and the strength of regulatory oversight across countries. Understanding the configurations of private ownership and investment within healthcare market across countries – situated within their broader regulatory frameworks – is thus essential for identifying the risks and opportunities associated with different investor-ownership models. Despite the rise of PE across high-income countries, much of the existing evidence focuses on the US healthcare system (Cerullo et al., Reference Cerullo, Lin, Rauh-Hain, Ho and Offodile2022; Nie et al., Reference Nie, Hsiang, Marks, Laditi, Varghese, Umer, Haleem, Mothy, Wang and Patel2022; Pauly & Burns, Reference Pauly and Burns2024; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Fuse Brown and Papanicolas2025b), which is characterised by a health system and institutional arrangements that differ significantly from those in other high-income countries, thereby limiting the generalizability of these findings (Borsa et al., Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023).

To address this gap, in section 4, we draw comparisons between the US and four selected European countries with different health systems to further contextualise the regulatory environments and market dynamics shaping private ownership-investment across different institutional contexts. Considering that our typology highlights how PE poses distinguished risks in the market compared to other investor-ownership types, the cases study analysis mainly focuses on the regulation of PE in the healthcare market.

4. Private ownership and regulation in healthcare provision: a comparative case study analysis

4.1 The UK

4.1.1 Private ownership and investment in the healthcare market

Despite the UK’s publicly financed and state-owned healthcare system, privately delivered services have long played a role, in sectors such as general practice, orthopaedics, optometry, and dental care (Chalkley & Sussex, Reference Chalkley and Sussex2018). Both for-profit and non-profit providers deliver NHS-funded as well as private services. The private healthcare market was estimated at £12.4 billion in 2023, reflecting continued merger and acquisition activity and consolidation, especially among hospital groups. In general practice, new organisational models have emerged, including ‘super-partnerships’ of up to 100 partners, some general practitioners (GP)-owned and others acquired by US firms (Fisher & Alderwick, Reference Fisher and Alderwick2023). The UK healthcare market has seen a gradual increase in private equity activity services (Bayliss, Reference Bayliss2022). Some financial investors have also capitalised on the stability of NHS-funded contracts. For instance, The Priory, one of the largest private mental health providers, derives 85% of its revenue from NHS and public sources (Bayliss, Reference Bayliss2016). In mental health, market concentration is relatively high. Four companies control 65% of the private market, including Cygnet, Elysium Healthcare, and The Priory, all owned by for-profit investors (Bayliss, Reference Bayliss2022). In long-term care, five major for-profit corporate providers – HC-One, Four Seasons, Care UK, Barchester, and Bupa – together hold about 11% of the market, operating around 50,000 beds (Bourgeron et al., Reference Bourgeron, Metz and Wolf2021).

4.1.2 Regulatory framework

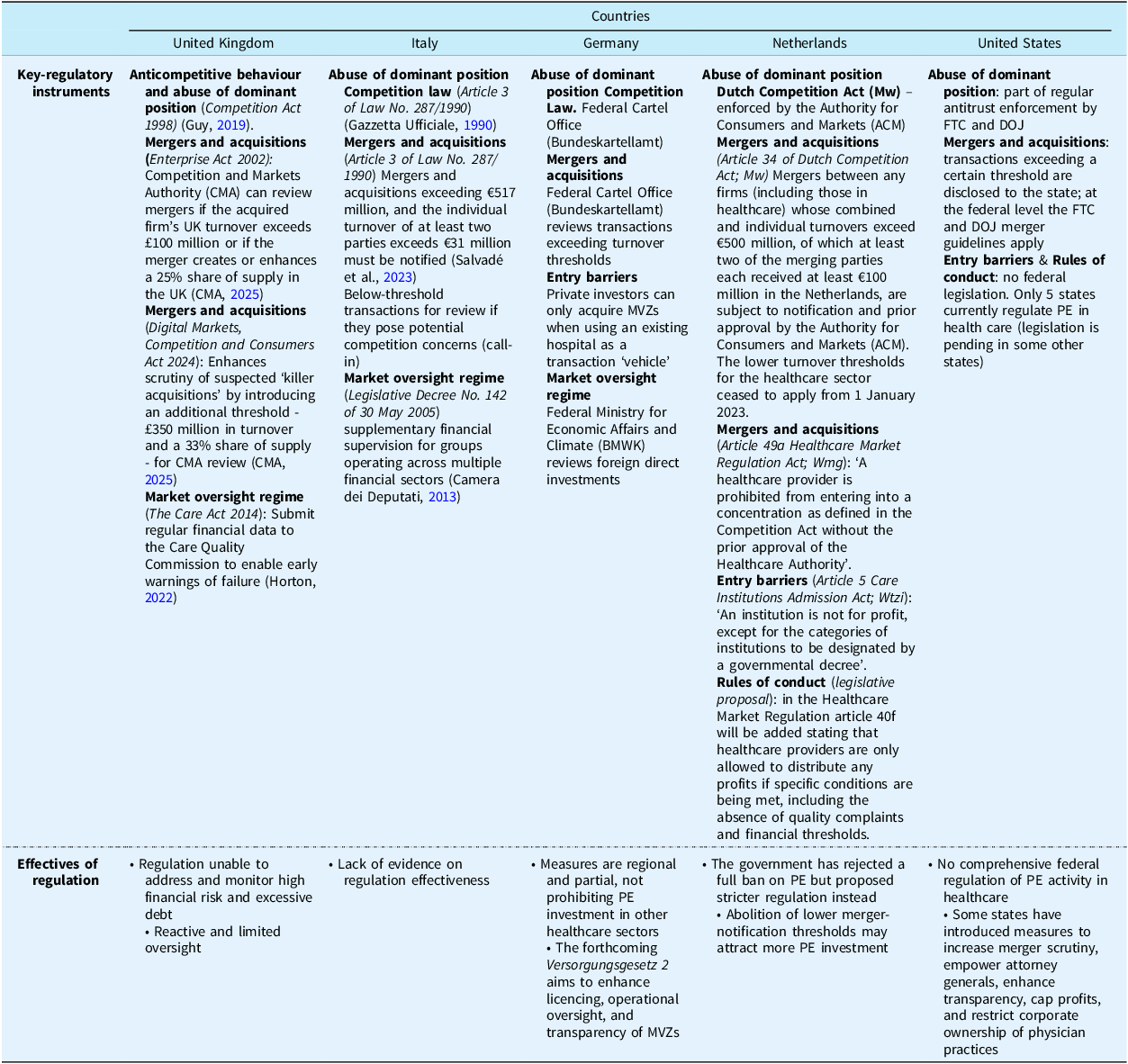

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) enforces provisions of the Competition Act 1998 (CMA, 2016), responsible for preventing anticompetitive behaviours such as cartels, price-fixing, and abuse of dominant position in healthcare markets (Guy, Reference Guy2019). Under the UK’s Enterprise Act 2002, the CMA can review mergers if the acquired firm’s UK turnover exceeds £100 million or if the merger results in or increases a 25% share of supply in the UK (CMA, 2025). The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 enhances scrutiny in cases of suspected ‘killer acquisitions’ by introducing a new threshold of £350 million in turnover and a 33% share of supply. In response to the collapse of Southern Cross in 2011, the 2014 Care Act introduced a market oversight regime - large investor-owned care home providers (often offshore-owned) must submit financial data to the Care Quality Commission (CQC) to enable early warnings of failure – aimed at ensuring continuity of care in case of failure.

4.1.3 Effectiveness of regulation

Strategies pursued by private equity firms in the acquisition of care home chains in the UK have been linked to their financial collapse. Many of the strategies used by investment firms to generate returns expose entire chains of care homes to high costs and debt, increasing the risk of bankruptcy and closure, while shifting profits offshore through complex corporate structures and subsidiaries in tax havens (Horton, Reference Horton2021). Investor returns are often achieved by cutting labour costs, with pay disparities in care firms resembling those seen in large corporate sectors (Walker, Kotecha, Druckman, & Jackson, Reference Walker, Kotecha, Druckman and Jackson2022). The market oversight regime introduced following the collapse of home care chains has been criticised as reactive, with insufficient regulation of ownership and limited investor accountability (Horton, Reference Horton2022). The Act also created a moral hazard by shifting the financial burden of provider failure onto local authorities, weakening incentives for financial prudence among large private providers. Despite a significant share of services provided by private investors is publicly funded through revenue from local authorities, taxpayers receive little transparency or accountability in return (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Cowie, Earle, Folkman, Froud, Hyde, Johal, Jones, Killett and Williams2016).

4.2. Italy

4.2.1 Private ownership and investment in the healthcare market

Italy’s NHS is primarily tax-funded, with a mixed healthcare provision model that includes both public and private providers, operating on a for-profit or non-profit basis (Toth, Reference Toth2016). Around one-third of all Servizio Sanitario Nazionale (SSN)-funded services are outsourced to private actors (Toth, Reference Toth2016). Sole proprietorships are prevalent among GPs and specialists (Green, Reference Green2012). Between 2017 and 2021, 69 PE deals were recorded in the healthcare services sector (Bava & Tamborini, Reference Bava and Tamborini2023). The total PE investment across healthcare and pharma reached its record – €17.1 billion in 2021 (Bava & Tamborini, Reference Bava and Tamborini2023). The highest concentration of financial capital is found in outpatient diagnostics and specialist ambulatory care, as well as in long-term care services (Trianni & Gazzetti A., Reference Trianni and Gazzetti2023). Private equity has capitalised on the growing demand for elderly care, with residential care (RSA) operating at full capacity. In 2023, elderly care facilities experienced the highest revenue growth among private healthcare subsectors (+14.0%), surpassing diagnostics, rehabilitation, and acute hospital care (Area Studi Mediobanca, 2014). While PE involvement in public-private partnerships has traditionally focused on non-clinical services (e.g., infrastructure and facility management (Cappellaro & Longo, Reference Cappellaro and Longo2011), it is now shifting toward direct clinical service provision. This expansion is particularly targeting smaller, highly profitable providers in Northern regions as part of broader consolidation strategies (Bava & Tamborini, Reference Bava and Tamborini2023).

4.2.2 Regulatory framework

In Italy, Article 3 of Law No. 287/1990 prohibits the abuse of a dominant position in the healthcare market, preventing practices such as unjustifiably high prices, restrictive contractual conditions and concentration (Gazzetta Ufficiale, 1990). This law mandates that mergers and acquisitions exceeding €517 million, and the individual turnover of at least two parties exceeds €31 million must be notified to the Italian Competition Authority (AGCM) for prior approval to (Salvadé et al., Reference Salvadé, Marini, Balestra, Pinto, Turrini and Simonet2023). AGCM the authority to ‘call in’ below-threshold transactions for review if they pose potential competition concerns, particularly in sectors like healthcare (Immordino et al., Reference Immordino, Graffi and Zappasodi2022; Modrall, Reference Modrall2023).

4.2.3 Effectiveness of regulation

Overall, in Italy, while the role of private investors has long been consolidated, the role of private equity in healthcare provision is still emerging and is expected to expand in the coming years. Despite these trends, evidence on the financialization of healthcare in Italy remains limited, highlighting the need for further investigation. Given the scarce evidence on the implementation and effectiveness of current regulations and the growing financialization of profitable sectors such as nursing homes, additional research is needed to assess the broader implications for the healthcare system.

4.3 Germany

4.3.1 Private ownership and investment in the healthcare market

Over the past decades, regulatory changes have reshaped the German healthcare market, both facilitating (early 2000s) and recently restricting private investment. In 2004, there was a health system financing reform that enabled private investments into primary care. This opened the door for PE funds to enter the sector. Following this reform, private investments in German primary care indeed expanded significantly (Tille, Reference Tille2023). In 2015, legislation passed which strongly facilitated the expansion of so-called ‘Medizinisches Versorgungszentrums’ (MVZs); i.e., healthcare facilities providing a platform for various medical specialties to collaborate, bolstering outpatient care as well as treatment coordination and resource sharing. In that year the requirement for cross-specialty integration was removed. This made the MVZs an attractive business venture for private investors. Since 2015, the number of MVZs has nearly doubled to about 4,200 of which 21% are owned by PE with the highest percentages in dentistry, ophthalmology, radiology and orthopaedics (Deloitte, 2023). Most PE firms are from neighbouring countries and the US (Scheuplein et al., Reference Scheuplein, Evans and Merkel2019). Due to privatisations, also the share of for-profit hospitals has also increased significantly over the years (Klenk, Reference Klenk2011). In this sector there are four major players: Rhon-Klinikum, Fresenius-Helios Group, Asklepios Kliniken, Sana Kliniken AG.

4.3.2 Regulatory framework

In Germany, the Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt) enforces the prohibition on abuse of a dominant position. It also reviews transactions exceeding turnover thresholds. In addition to the general antitrust law, in healthcare private investors can only acquire MVZs when using an existing hospital as a transaction ‘vehicle’. To ensure that acquisitions do not pose risks to German society, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate (BMWK) reviews foreign direct investments, with stricter rules for investments in critical infrastructure (including healthcare). As a result, when an investor acquires >10% of the voting rights they must notify the BMWK.

4.3.3 Effectiveness of regulation

In response to concerns about the growth in private investments in MVZs and its impact on costs and quality, the German government in 2019 introduced restrictions on how PE firms can establish and operate MVZ’s in dentistry and non- medical dialysis services (Marwood Group, 2019). The legislative changes, based on regional market shares, did not prohibit private equity investments in these areas nor did they affect PE investment in other health care sectors. New legislation – i.e., the ‘Versorgungsgesetz 2’ – aims to further develop the regulatory framework for MVZs focusing on their establishment, licencing, operation and transparency. Hence, due to concerns about profit maximisation at the expense of quality and accessibility Germany is attempting to limit the influence of PE in its healthcare system.

4.4 The Netherlands

4.4.1 Private ownership and investment in the healthcare market

The Dutch health system has a unique institutional setting which can be described as an evolution of market-oriented health care reforms (Helderman et al., Reference Helderman, Schut, van der Grinten and van de Ven2005). Except for the university medical centres and Public Health Services, all healthcare providers are private entities operating on a profit or non-profit basis. Under the current legislation, healthcare institutions are not allowed to have a profit motive – meaning they cannot distribute profits to stakeholders or employees (non-distribution constraint) – except for categories of institutions to be designated by the Minister of Health. In practice, however, almost all healthcare providers are designated as exception to general the rule: e.g., primary care (incl. GPs), pharmaceutical care (incl. pharmacies), dental care, midwifery care, district nursing. The mandatory not-for-profit in fact therefore only applies to providers of inpatient care like hospitals and nursing homes. Although private for-profit ownership is widespread within the Dutch healthcare system, this most often does not involve PE. Recent research by (EY Consulting, 2024) found that almost all cash flows under SHI (Zvw/Wlz) concerns healthcare institutions without PE participation (>95%), except for maternity care (75-80%) and dental care (75-80%). Nevertheless, there are concerns about the growing share of private equity in Dutch healthcare. In recent years, almost 50% of the concentrations assessed by the Healthcare Authority (NZa) were traceable to firms in which private equity has a stake (NZa, 2025).

4.4.2 Regulatory framework

The Dutch Competition Act (Mw), enforced by the Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM), prohibits the abuse of a dominant position. This prohibition of course also applies to private for-profit healthcare providers. This also true for ACM’s preventive merger control. Mergers between any firms (including those in healthcare) whose combined and individual turnovers exceed €500 million, of which at least two of the merging parties each received at least €100 million in the Netherlands, are subject to notification and prior approval by the ACM. The lower turnover thresholds for the healthcare sector, that had been in place since 2008, ceased to apply from 1 January 2023. Following the Healthcare Market Regulation Act (Wmg), healthcare provider are prohibited from entering a concentration as defined in the Competition Act without the prior approval of the Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZa). Through the healthcare-specific concentration test, the NZa checks that the concentration process has been carried out carefully. In addition, the concentration and the planned changes must not affect the continuity and accessibility of healthcare services. This applies to clients, staff and other stakeholders involved in the concentration process. The NZa also examines whether the standards of essential care are at risk. Between 2014 and 2023, almost 50% of the concentrations assessed by the Healthcare Authority (NZa) were traceable to healthcare institutions in which private equity had a stake (NZa, 2025). These most often involved dental care.

4.4.3 Effectiveness of regulation

In the Netherlands, although the traditionally private nature of the Dutch healthcare system is not in question, there is growing concern about the role of private equity in healthcare. Some worrying case studies – see for example De Rijk (Reference De Rijk2023) and the bankruptcy of the new commercial GP chain Co-Med in 2024 – have fuelled to public and political debate about private investments in healthcare. Contrary to the wishes of parliament, the government has repeatedly stated that there will be no total ban on PE. Instead, earlier this year a proposal for additional regulation has been proposed. As part of this broader plan, in the Healthcare Market Regulation Act article 40f will be added stating that healthcare providers are only allowed to distribute any profits if specific conditions are being met, including strict financial thresholds and the absence of quality complaints. In response to the abolishment of the lower notification thresholds for healthcare mergers, the ACM warned that this makes the Netherlands more attractive for PE firms. It has therefore asked for the introduction of a ‘call-in’ option meaning the power to assess transactions that do not meet the thresholds for a mandatory merger control notification.

4.5 United States

4.5.1 Private ownership and investment in the healthcare market

In the US health system, private for-profit ownership is historically widespread. However, over the past 10-15 years PE market penetration increased substantially (Abdelhadi et al., Reference Abdelhadi, Fulton, Alexander and Scheffler2024; Aldridge et al., Reference Aldridge, Hunt, Halloran and Harrison2024). This mainly concerns investments in hospitals, hospices and physician practices. From 2010-2020, PE acquisitions nearly tripled (Cai & Song, Reference Cai and Song2024). This involves funds from different investors, including pension funds, endowments, institutions, sovereign funds and individuals. At the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) level, for some specialties the market share of physician practices owned by PE firms may now exceed 50% which has raised concerns about their market power (Abdelhadi et al., Reference Abdelhadi, Fulton, Alexander and Scheffler2024). In some states more than 15% of the hospitals are owned by PE (Blumenthal et al., Reference Blumenthal, Gumas, Shah, Gunja and Williams2024).

4.5.2 Regulatory framework

At the federal level, mergers and acquisitions in which PE is involved are part of the regular antitrust enforcement by Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and US Department of Justice (DOJ). Same applies for the prohibition on abuse of a dominant position. Most existing state laws require that transactions exceeding a certain threshold are disclosed to the state. However, most PE acquisitions fall below the notification thresholds resulting in limited antitrust oversight. In 2021, the Biden administration issued an Executive Order to encourage federal agencies to work toward improving competition. As a result, the FTC has issued guidelines to expand regulatory review of merger impact on competition to include ‘roll-ups’; i.e., serial acquisitions that together exceed regulatory thresholds above which a merger is considered anticompetitive (Cai & Song, Reference Cai and Song2024). There is no specific federal legislation for regulating PE in healthcare while only five states currently do have this, but legislation is pending in some other states (Blumenthal et al., Reference Blumenthal, Gumas, Shah, Gunja and Williams2024).

4.5.3 Effectiveness of regulation

In their systematic review, with most of the studies included occurring in the US, Borsa et al. (Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Bruch2023) conclude that PE ownership is often associated with harmful impacts on costs to patients or payers and mixed to harmful impacts on quality. In a later study and as another example, (Kannan et al., Reference Kannan, Bruch and Song2023) find that PE acquisition of hospitals was on average associated with increased hospital-acquired adverse events. Despite these concerns, there is no federal action on regulating PE in healthcare (Blumenthal et al., Reference Blumenthal, Gumas, Shah, Gunja and Williams2024). At the state level, some policies have tried to increase pre-transaction regulation of mergers & acquisitions, empower attorney generals, increase transparency of PE, cap profits & establish spending floors, and limit corporations form owning physician-operated medical practices (Cai & Song, Reference Cai and Song2024). Overall, Democratic states are more likely to regulate PE than Republican states (Table 3).

Table 3. Key regulatory instruments and effectiveness of regulation of private investment-ownership in five high income countries

5. Discussion

This study contributes to the emerging literature on ownership in healthcare markets, by presenting a novel typology that categorises the different types of private investor ownership in health services provision. We systematically map the financial, strategic, and operational attributes of private investor-owners that determine their behaviour and incentives in healthcare markets, highlighting that not all private sector ownership forms have the same incentives in the health service market. Our proposed typology functions as a conceptual lens to better understand the policy relevance and implications of the ownership forms we observe in particular countries and service domains. The typology’s strength lies in identifying characteristics and mechanisms that apply independently of country context, allowing for nuanced analysis. Our typology demonstrates that ownership itself can be a determinant of healthcare provider behaviour, thereby supporting the argument that both market and ownership regulation are necessary.

Empirically, the typology provides a country-level analytical tool to identify emerging trends and regulatory gaps. It enables the mapping of incentives, risks, and opportunities associated with each ownership type and can be applied both ex ante and ex post to analyse how ownership dynamics evolve as investment horizons or models change within and across countries. Our comparative case study analysis of five countries demonstrates that, despite differences in public–private financing and provision, all five countries are experiencing a diversification of private investment in healthcare, with an emerging role for financial actors, such as PE investors, particularly in areas with relatively low barriers to entry, including outpatient care, elderly care, and diagnostics, consistent with findings from previous studies (OECD, 2024).

To our knowledge, only Tracey et al. (Reference Tracey, Schulmann, Tille, Rice, Mercille, Timans, Allin, Dottin, Syrjälä and Sotamaa2025) have reviewed policy options for regulating PE in healthcare, focusing on countries such as Canada, Germany, Finland, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the US. We broaden this by including other forms of private investor ownership and additional countries unexplored in previous literature, such as Italy and the UK.

5.1 Lessons learnt from the analysis of regulatory efficiency

We found that regulation of PE and other investor ownership remains largely absent across countries, albeit Germany and the Netherlands are moving to strengthen oversight of ownership, while the UK and US remain focused on regulating markets, regardless of ownership. The latter is notable in light of recent developments such as the collapse of healthcare providers chains in the UK and the Netherlands, which exposed the systemic risks associated with highly leveraged investor models. Although the presence of PE in Italy remains limited, it is expanding – particularly in homecare – where similar vulnerabilities may emerge.

These findings are broadly generalisable to other high-income countries, as the patterns observed across our case studies align with previous international evidence (Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Schulmann, Tille, Rice, Mercille, Timans, Allin, Dottin, Syrjälä and Sotamaa2025; OECD, 2024). Regulation in all five countries examined predominantly targets market conduct and competition oversight rather than provider ownership. As shown by Tracey et al. (Reference Tracey, Schulmann, Tille, Rice, Mercille, Timans, Allin, Dottin, Syrjälä and Sotamaa2025), this pattern is replicated in Finland, France, and Ireland, where regulatory frameworks also focus on merger-notification thresholds and competition law. The risks identified extend beyond our sample. Similarly to the UK, in 2022, Australia experienced the bankruptcy of its largest private equity-backed oncology chain following the accumulation of AUD 2 billion in debt (OECD, 2024), demonstrating similar vulnerabilities in systems permitting high leverage and inadequate financial oversight.

The current regulation lags behind market developments. Overall, existing regulatory frameworks were typically designed for traditional ownership models; i.e., non-profit organisations and private businesses characterised by gradual growth, transparent governance, and alignment between business objectives and professional ethics. These systems rely substantially on relational contracting and trust-based oversight mechanisms. However, for-profit ownership in healthcare is increasingly diversifying across many countries (Singh, 2025b), with emerging investor types such as private equity operating under fundamentally different incentive structures characterised by high leverage, short investment horizons, and aggressive profit-extraction mechanisms. Existing regulatory and contracting systems have not yet adapted to address the agency problems posed by these investment models, which become deeply embedded in both clinical and financial decision-making.

Our typology examines how ownership models shape financial, strategic, and operational incentives. These incentives affect financial sustainability – such as the degree of debt leveraged – which, in the event of collapse, can undermine quality and access. They may also generate broader systemic risks, including ‘too big to fail’ scenarios and ‘care deserts’ in underserved areas. Given the role of private equity in delivering publicly financed services like community and mental healthcare, such failures risk undermining public confidence in the national health system. In contexts with limited public provision, governments are often forced to intervene to correct market failures. Failure to do so may require absorbing losses or ensuring service continuity using public funds.

From the analysis of regulatory efficiency three policy lessons emerge. First, ownership-specific regulation is critical: current frameworks that treat all providers alike fail to capture the distinct incentives and financial risks posed by heterogeneous investor-owned entities, particularly private equity firms employing high leverage and short investment horizons. Second, regulatory approaches must transition from reactive intervention to anticipatory oversight, incorporating continuous monitoring of financial viability, debt-to-equity ratios, ownership changes, and corporate restructuring activities to enable early detection of systemic risks. Third, transparency and accountability mechanisms require substantial strengthening. Ownership structures – including below notification thresholds or offshore arrangements – must be disclosed to ensure appropriate stewardship of public resources – when private investment delivers publicly funded healthcare services – and protection of patient welfare.

However, regulatory effectiveness remains contingent on country-specific institutional and policy contexts, including health system architecture, public-private financing configurations, regulatory enforcement capacity, and political commitment to proactive oversight. Consequently, although the fundamental challenges posed by investor ownership in healthcare are consistent across nations, policy responses must be tailored to prevailing institutional arrangements which can differ significantly from one country to another.

5.2 Towards ownership-specific regulation

Policy debates and ad hoc regulatory responses often marginalise the importance of different forms of private ownership, yet in the context of market and policy failures, these matter greatly. What is needed is a more nuanced understanding of different forms of investor-ownership in healthcare, along with a more tailored regulatory approach -one that can balance the potential benefits of private ownership in its different forms with safeguards that effectively mitigate potential disadvantages. Regulatory and contracting frameworks should be informed by a clear understanding of the heterogeneity among for-profit ownership models. Forms of regulation specifically related to ownership – reflecting what forms of ownership in healthcare provision societies, regulatory, purchasers, etc. should (not) be promoted – are notable for their absence. This may need to be revisited going forward, as greater diversity in ownership becomes the norm.

Overall, there is an urgent need for more anticipatory, rather than reactive, regulatory strategies. On the one hand these strategies must protect against investor-ownership types that focus on aggressive, short-term profitability with high leverage, while ensuring that owners focused on long-term growth can achieve that goal in a manner consistent with key health policy goals of equity, efficiency and quality of care. From this perspective, a combination of entry regulation and behavioural oversight to better align the incentives of diverse private investors with public health objectives is crucially important. Strengthening ownership-specific oversight – through transparency requirements, entry regulation, and behavioural monitoring – will be critical to align private investment with public health objectives and thus to prevent the recurrence of systemic failures observed in several countries.

5.3 Limitations

This study examined primarily European countries, where evidence on private investor ownership remains limited. While our typology’s core dimensions (ownership structure, capital composition, governance involvement, and investment horizon) reflect fundamental mechanisms of financial control and managerial incentives applicable across contexts, institutional expressions vary with national regulatory capacity, capital market maturity, and healthcare financing models. The framework remains analytically valid but requires contextual interpretation when applied beyond Europe and North America. Future research should test this typology in additional European countries and in low-and middle-income markets with rapidly evolving private investment activity and ownership diversification, such as India and China (PitchBook Data, Inc., 2025).

Additionally, we focus on healthcare services, but the typology can be applied to other sectors – such as digital health technologies, medical devices and the pharmaceutical markets which have seen significant private equity activity – which require further analysis. However, in these services areas, the presence of investors tends to be less politically or ethically contested, as these sectors are historically associated with commercial innovation. Instead, investor involvement in the delivery of healthcare services often raises concerns in the public debate. While contractual incompleteness – an underlying theoretical assumption of our model – enables for-profit entities to exploit information asymmetries, contract design is beyond the scope of this empirical analysis. Future research should examine contracting mechanisms in greater depth to clarify how governments can strategically use contracting authority to align private sector behaviour with public health objectives.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tom Kruijt (Erasmus School of Health Policy & Management) for his excellent research assistance on the German and US case studies.

We thank you Dr Sara Allin and the European Health Policy Group participants for the feedback provided to an earlier draft of the paper.

Financial support

No financial support is declared by authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Use of AI tools

The authors acknowledge the use of AI (Claude) exclusively for English proofreading. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the manuscript.