Ireland was England’s first colony. Political, economic, and cultural imperialism characterized the early decades of the seventeenth century as the Stuart monarchs set out to make Ireland English and to introduce Protestantism as the state religion. The Catholic majority, understandably resentful of these efforts to colonize and to commercialize, rose in rebellion on 22 October 1641. This insurrection triggered a decade-long colonial war in Ireland that formed part of a wider conflagration that engulfed the British Isles, now known as the “Wars of the Three Kingdoms.”Footnote 1

Even though English authorities thwarted an attempt to seize Dublin Castle, they could not prevent Catholic insurgents from capturing strategic strongholds, especially in Ulster, and launching violent onslaughts against the Protestant inhabitants, many of whom were (to use modern parlance) “settler colonists” who had intensively colonized Ireland from the 1570s in a series of plantations. Over the winter of 1641 and spring of 1642, the bloodletting spread to engulf the rest of the country. The Protestants retaliated with equal force in what became one of the most brutal periods of sectarian violence in Irish history. The precise number of men, women, and children who lost their lives in the aftermath of the rebellion or subsequent war will never be known but historians suggest that at least twenty per cent of the population perished.Footnote 2 Indeed, it is likely that more people died during the course of the 1640s than in the rebellion of 1798, or in the Northern Ireland “Troubles” (1968–1998). Moreover, what we understand today to be “ethnic cleansing” undoubtedly occurred in 1640s Ireland, even if contemporaries did not use this language.Footnote 3

As part of the conflagration, incidents of sexual violence—stripping, castration, mutilation, rape, gang rape, and reproductive violations—were said to have occurred across the island against women and some men. The historical and legal evidence for this violence was recorded in witness statements that form part of an archive, known as the “1641 Depositions.” Though testimony that related sexual violence was rarely used in the courtroom, Protestant propagandists—from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries—manipulated these accounts to instill fear and justify retribution. Given their intensely sectarian and one-sided nature, it is little wonder that the “1641 Depositions” have been dubbed as the most controversial documents in Irish history.Footnote 4

The Archive

The “1641 Depositions” comprise an archive assembled over the course of the 1640s and early 1650s that records the events that surrounded the outbreak, course, and impact of the 1641 rebellion and ensuring decade-long war.Footnote 5 About 8,000 depositions or witness statements, examinations, and associated materials, by men and women of all social classes are extant. Bound in thirty-one volumes, the “1641 Depositions” have been housed since 1741 in the Manuscripts and Archives Research Library of Trinity College Dublin.Footnote 6

The “1641 Depositions” were assembled in two phases with the explicit purpose of recording losses suffered by the Protestant community and amassing detailed evidence to justify the retribution against the Catholic community that would follow once the state had re-established control in Ireland. In December 1641, a Commission for Distressed Subjects was established and charged with collecting sworn statements from refugees who fled to Dublin. It consisted of eight Church of Ireland clergymen. The deponents presented their accounts orally in response to a set of questions, which are no longer extant. The commissioners recorded these narratives and then repeated them aloud so that changes could be made.Footnote 7 The second phase of collection dated from the 1650s, when Oliver Cromwell ruled Ireland, and a group of more than 70 commissioners gathered evidence against individuals accused of acts of murder or massacre, allegedly committed during the 1640s. Between 1652 and 1654, these men and women were tried in newly established High Court of Justice or war crimes tribunals.Footnote 8 The “1641 Depositions” were then lodged in an office of “discriminations” in Dublin. Officials drew on them during the mid-1650s when adjudicating which Catholic landowners should be transplanted to estates in Connacht. Again, after the restoration of Charles II and the Stuart dynasty in 1660, the depositions informed decisions made by the commissioners of the Court of Claims, as Catholics and some Protestants scrambled to recover lost lands.Footnote 9

In other words, the “1641 Depositions” were largely deployed in court in cases that related to property or, in the instance of the High Court of Justice, to murders committed during the 1640s. Jennifer Wells has shown how the High Court of Justice, operated by military and legal officials, placed emphasis on the laws of war and how the criminal trials followed the same procedure with “elaborate prosecutions and defenses, replete with counsel and witnesses.”Footnote 10 Though the details are opaque, it appears that in the absence of a witness, the court relied on evidence recorded in the “1641 Depositions,” including hearsay testimony, as well as live witnesses. Thus, over a period of two years, the High Court of Justice at Dublin and Cork, which are the only court records that survive, tried 110 defendants, finding 56 men and women guilty on 150 counts of murder and accessory to murder; a further 39 were pardoned.Footnote 11 Violence committed against women forms part of the record of the court. For example, in 1653, Brian McCosker was tried for the murder on 15 November 1641 of William Norman of County Tyrone. William’s daughter, Mary, testified how Brian “whom she knew from a child” hung her father from a beam in their home, “put skeyns” to her breast, and threatened her mother. Mary’s twenty-one-year old daughter, Sarah, who had been twelve in 1641, testified to her grandfather’s murder as “an eye-witnesse of it.”Footnote 12 In another trial, Mary FitzGerald from County Kildare related how, in 1642, the accused men “did cruelly dragg her through the fire & carried her away.”Footnote 13

Though sometimes alluded to, direct references to sexual violence only appear in the proceedings of a single prosecution: the trial for high treason, as well as for murder, of Sir Phelim O’Neill, who was one of the leaders of the 1641 rebellion. The indictment included evidence of “rape” and “cruelties” and accused Sir Phelim and men under his command of committing numerous atrocities. They stripped naked Mr Starkey, the 100-year-old school master from Armagh, along with two of “his daughters virgins,” and drowned them in a pit; “they ravished Mr Allens wyff beefor her husbands face” before murdering them both; they thrust “a wodden pricke. up a mans fundant [i.e. fundament or anus]”; they laid “brilles on theire private p[ar]ts of the English”; they ripped an unborn infant from “a Scotchwomans belly”; and from James Maxwell’s wife, who was in labor, they “dragd away the child half borne.”Footnote 14

At the trial, a handful of “1641 Depositions” were cited as evidence. By far the most important was that of an Anglican clergyman, Robert Maxwell from County Armagh, who had been held hostage by Sir Phelim but escaped to testify on 22 August 1642.Footnote 15 Given the importance of Maxwell’s testimony in the conviction of Sir Phelim it is worth quoting it at length, even if the stories of what allegedly happened are graphic and the details deeply disturbing:

And that his [James Maxwell’s] wife Grisell Maxwell being in Childbirth, the Child halfe borne and halfe vnborne, they stript starke naked, and drove her about an arrow flight to the blackwater and drowned her. The like they did to another English woman in the same parish in the begining of the rebellion, which was little inferiore (if not more vnnaturall and barbarous) then the roasting of Mr Watson alive after they had cutt a Collop out of either buttocke. That a scotch woman was found in the Glyn wood lying dead, her belly ripped vpp, and a liveing child crawling in her wombe … That Mr Starkie Schoolmaster att Armagh a gent[leman] of good parentage and parts being vpwards of 100 yeares of age they stript naked, caused 2 of his daughters virgins, being likwis{e} naked, support him vnder each arme not being able to goe of himse{lf} and in that posture carried them all three a quarter of a mile to a turff pitt and drowned them, feeding the lust of theire eyes and the Crueltie of theire harts with the selfe same obiects at the same tyme … If any women were found dead lying with theire faces Downwar{ds} they would turne them vpon theire backes, and in great flockes { } vnto them censuring all partes of theire bodies, but especially such {as} are not to be named which afterwards they abused so many wayes { } so filthyly as chast[e] eares would not endure the very naming.Footnote 16

Maxwell finished his harrowing deposition by relating how a leading Monaghan insurgent had made sadistic “sport” by taking “a woodden prick or broach and thrust it vpp into the fundament of an English or scottish man, and then after drive him about the roome with a Joynt stoole vntill through extreame payne he either faynted or gave content to the spectators by some notable skypps and ffrisks.”Footnote 17 In short, according to Maxwell, rape, torture, genital and reproductive mutilation of the living and dead, ritual spectacle, and extreme humiliation at the hands of men loyal to Sir Phelim were precursors to death, often by drowning.

Our challenge is how best to interrogate gruesome accounts like these to better understand the nature of sexual violence in early modern Ireland. As Maxwell’s deposition vividly illustrates, the “1641 Depositions” are far from neutral or, to quote Alexandra Walsham, they are not “unproblematic reservoirs of historical fact.” Instead, the archive “operates as a distorting filter, lens and prism.”Footnote 18 The fact that the majority of deponents were Protestant and that Protestant clergymen, like Maxwell, and later officials collected the testimony on behalf of the state means that “1641 Depositions” are what Ben Kiernan has dubbed a “single-purpose” archive.Footnote 19 There is no comparable body of evidence to record the violence that Catholic women suffered at the hands of the government/Protestant forces, even if a few did testify during the early 1650s about their harrowing experiences a decade earlier.Footnote 20

Given this bias, one has to ask if the archive is of any value to scholars? Here, the extensive corpus of work by Ann Laura Stoler is particularly relevant. Stoler invites us to look again at how we interrogate our archives, to examine “archive-as-subject” rather than simply extract information (“archive-as-source”) and to read colonial archives “against their grain.”Footnote 21 She looked at the Dutch archives but her methodology is equally relevant to other colonial archives which are also sites of knowledge production capable of distorting the past.Footnote 22 So, if we acknowledge their biases and read the “1641 Depositions” “against their grain,” they provide important insights into the nature of violence committed during the 1640s.Footnote 23

In the “1641 Depositions,” people (mostly Protestants) of all backgrounds told of their experiences, what they had seen, and what they had heard following the outbreak of rebellion on 22 October 1641. As in any legal document, the format of each deposition was fairly standard and included basic biographical information: the name, address, marital status, and, in some cases, the deponent’s age and occupation. After relating any losses, the deponent first provided an account of what had been seen and experienced—eye-witness evidence—followed by what had been heard from others, the hearsay evidence, which was admissible in court. The eye-witness testimony usually included the names of assailants, their words, and their actions. Though legal documents, some of these are also deeply personal narratives that documented losses and alleged crimes committed against the deponent, their kin or community by Irish insurgents, including assault, imprisonment, the stripping of clothes, hostage taking, sexual violence, and murder. The hearsay evidence tended to be vaguer and often included more sensational claims, especially about the frenzied violence inflicted on other people.

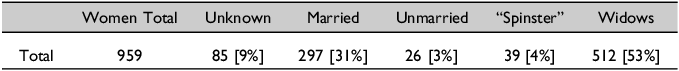

In all, there were 959 female deponents (see Table 1), which means that roughly one eighth of all deponents were women, which, by early modern standards, was an exceptionally high proportion. In addition, thousands more women were named in the depositions given by men. Of the female deponents, 512 (or fifty-three per cent) were listed as widows, 297 (or thirty-one per cent) as married, and sixty-five as single (seven per cent described as “spinster” or unmarried). Without the protection of their menfolk, the unmarried and widowed women, who accounted for at least sixty per cent of all female deponents, were particularly vulnerable. Yet, even the married women, whose spouses were away fighting, were often defenseless and might be viewed as widows in waiting. Whatever their marital status, a very high proportion of these women had caring responsibilities for infants, children, grandchildren, elderly parents, and infirm relatives. Of the widows analyzed here, twenty-five per cent mentioned dependent children in their depositions, along with step-children, and grandchildren, and nearly fifty were responsible for the care of four children or more. For example, Agnes Windsor, about fifty years old, from County Fermanagh, deposed on 5 January 1642 that she, her husband, William, a tanner, and her extended family of ten children, five described as “infants,” were all robbed and stripped. William and her eldest son later died in military service, while two of her daughters were murdered outside Naas, leaving her to care for one grandchild, along with her four other children.Footnote 24

Table 1. Status of Women Who Deposed (as recorded in the “1641 Depositions“)

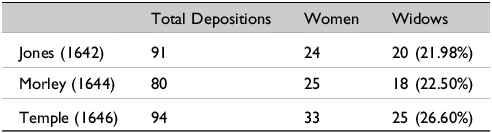

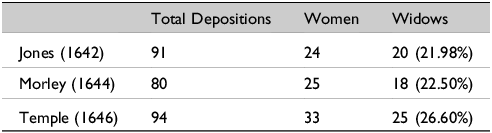

Table 2. 1641 Depositions by Widows that Appeared in Print

In the pre-war years, these women lived in family units in urban and rural communities and came from every province and every county. Scrutiny of surnames suggests that they were the wives, sisters, and daughters of colonists who had settled in Ireland in significant numbers during the Munster plantation of the 1580s and then during the Ulster plantation of the early seventeenth century. The occupation and/or social status of a woman’s husband is listed in over a third of depositions given by all women and in fifty per cent of those provided by married women. The bulk of husbands were drawn from the gentle and “middling sort,” something that makes the “1641 Depositions” so extraordinary. These are the people who are so absent from history, especially in Ireland.

Violence Recorded in the Archive

Analysis of the “1641 Depositions” given by women reveals the full range of their suffering: robbery, assault, hostage taking, captivity, stripping, rape, gang rape, military action, killing, mass killing, and death.Footnote 25 At least seventy-five per cent recorded robbery, the loss of goods and debts, and destruction of property by neighbors, servants, and tenants, whom they named, as well as by men and women they could not identify. Robbery was often accompanied by incidences of extreme violence—assault, stripping, torture, and killing—which women experienced in their homes, in captivity, or as they travelled in search of refuge. The winter of 1641–2 was the coldest on record and freezing conditions claimed the lives of many, who died of exposure. For those who survived, these experiences often left them physically maimed and emotionally scarred.

The insurgents stripped more than one quarter of the women, sometimes more than once, as they looked for money, jewels, and other valuables that might be hidden in clothing, shoes, or even in their hair. Ellen Adams, who had been married to a minister from County Fermanagh, was stripped and received wounds to her hands, sides, skull (“searching for money as they pretended”) and a deep gash under her jaw bone almost removed her tongue.Footnote 26 Of course, stripping was more than about finding money or the economic value of clothing. It was a means of humiliation, which “evoked a subversion of colonial relationships.”Footnote 27 One of the best-known narratives that later appeared in print was by Magdelene Redman from Durris in King’s County.Footnote 28 In her deposition, Madeline recounted her journey, along with twenty-two other (unnamed) widows. After the rebels robbed them, they “were also stript, starke naked and then they covering themselves … in strawe the rebells then and there burned and lighted the straw with fyer.” Other “rebells more pittifull then the rest” urged restraint, which allowed the tortured refugees to escape. Terrified, they languished in the “wild woods” for five days “in frost and snow.” It was so cold that the snow lay “unmelted” on their skin and “some of their children died in their arms.” The desperate group finally found refuge at Birr castle, where forty of “those stript persons” died.Footnote 29

The high incidence of stripping, a form of sexual assault in itself, makes the virtual absence of reported rape in the “1641 Depositions” all the more striking. Mary O’Dowd argues rape was underreported, while Nicholas Canny and Morgan Robinson suggest that the lack of reports meant rape rarely occurred.Footnote 30 Others point to the high burden of proof needed in early modern rape cases (vaginal penetration, ejaculation, and lack of consent) and suggest that female Protestant victims proved reluctant to subject themselves to this.Footnote 31 In groundbreaking research on sexual violence and the “1641 Depositions,” Naomi McAreavey has drawn inspiration from Garthine Walker’s work on the language and conventions surrounding “rape narratives,” as recorded in English court records, and applied this to the “1641 Depositions.” While acknowledging the differences, especially the brevity of the account (“rape fragments”) and the fact that it is often hearsay evidence, McAreavey has shown how reports in the “1641 Depositions” broadly conform with Walker’s “rape narratives.”Footnote 32 That said, there is unique emphasis in the “1641 Depositions” on the presence of men during the violation. Catholic men were active perpetrators, while Protestant men were forced to observe the assault, as in the case of Mr and Mrs Allen mentioned earlier.

While victims remained silent, others recorded the violence they suffered and clearly felt aggrieved that often-named perpetrators were rarely held to account. For example, two deponents—one from 1642 and another from 1645—reported that they had heard that Hubert Farrell raped Sarah Adgor on 10 December 1641. Reluctant to talk about it, “Sarah afterwards confessed & told to her mother, And although that fowle offence was generally talked of & beleeved yet the offender escaped vnpunished.”Footnote 33 Slightly more detailed was the account by Christopher Cooe, a Galway merchant, of the rape of a servant called Mary. Christopher and his wife “credibly heard” from Mary that “one Liuetenant Bourk had at her Masters howse in Tuam aforesaid forceibly ravished her, and to prevent her crying out one of his souldjers thrust a napkin into her mowth and held her fast by the haire of her head till the wicked att [act] was performed.”Footnote 34 The rapist, an Irish lieutenant, forced himself on Mary as his men gagged her and looked on. Whether they also assaulted her is not stated. However, another deposition related the gang rape of Elizabeth Woods. William Collis, a saddler from Kildare, claimed that he “heard divers of the Rebells at Kildare say & confesse That seven of … hadd Ravished & had Carnall knowledge of an English protestant: woman (one presently after another) soe as they gaue her not tyme to rise till the last act performed.”Footnote 35

Rape, as we know from earlier Irish and other, more recent, conflicts, is “the ultimate act of aggression and humiliation of an enemy” and “the mother’s milk of militarism.” Given the nature of the violence reported in the “1641 Depositions” and prevalence of rape in earlier Irish conflicts, it is hard to believe that rape was not more widespread in 1640s Ireland.Footnote 36 Of course, the language used to describe sexual violence poses challenges since modern terminology is rarely used. Euphemisms like “ravish,” “defile,” “abuse,” “deflower,” “use,” “force,” and “dispoyle” were more common than “rape.” Metaphors and phrases like “taken by the haire,” “stripped to the skin,” “wicked act,” “had Carnall knowledge of,” “tooke to themselues,” or “to vse or rather abuse her as a whore” suggest sexual violation and demand close reading of the historical record. Consider the pain and distress recounted by Amy Manfin in her deposition of 2 March 1642. Widow Manfin, “a Brittish protestant” from Queen’s County, had witnessed the murder of her husband at the hands of her neighbor’s “plowman.” Her assailants had then “cawsed her to stand in her husbands blood And also cawsed her to stripp herself, And after they took her by the haire of her head, and dragged her throughe thornes. And then bade her gett her thence.”Footnote 37 Rape is not mentioned but the fact Amy was stripped and taken “by the haire” suggests sexual violation and torture, as does the phrase “dragged her throughe thornes.”

How then do we decode references to sexual violence and better understand how women experienced extreme trauma? Here, research done by Rosemary Byrne in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia in assessing oral evidence in twentieth-century international criminal law might offer some fascinating insights into how best to decode the testimony of seventeenth-century witnesses like Amy Manfin. Byrne shows how shame and privacy concerns, along with the fact that some victims were clearly suffering from post-traumatic or extreme stress disorders, meant that women often withheld or obfuscated the fact that they had been raped or experienced extreme sexual violence.Footnote 38 Joanna Bourke concurs. In a groundbreaking survey of global sexual violence since the nineteenth century, Bourke notes how victims often struggled “to access a language for reporting sexual violence” and instead spoke in euphemisms.Footnote 39 Sensitive to intersectional vulnerabilities, Bourke offers a nuanced analysis of how feelings of shame, closely associated with social and cultural notions of honor, meant that women preferred to remain silent rather than seek justice.

In 1640s Ireland, the shame and social stigma attached to rape, the circumstances in which the deponents gave their testimony, and the fact that the male commissioners were clergymen (or later military or government officials) probably stopped more cases being reported. In an unpublished treatise, dating from 1643, the commissioners reflected on the “rare mention of rapes.” They argued that the absence of reports should not be seen as evidence that “this barbarous outrage” did not occur, adding:

Wickednesses of that nature have commonly noe witnesses, but the graceless actors … and the miserable sufferer, whose presen[t] thraldome under such miscreants suffers not relation, or modesty, they having escaped (especially where complaint can procure noe redresse or revenge) forbid an indiscret publication, w[i]th all the friends and kindred of such miserable sufferers, whose inconsiderate rashness had sometimes rumoured monstrous usages of that kind by the rebells, have since proved very tender in touching on such reports [which might result in a child](though forced) of their owne blood, and might some way reflect on their same whom their affection wisheth every way unspotted.Footnote 40

In other words, the commissioners held that rapes probably did occur but the victims, fearing that the perpetrator would not be caught, preferred to keep silent. These women were not “willing to speake … but rather chooseing to referre them to the judgment of that day, when such hidden things of dishonesty shall be accompted for and punished.”Footnote 41 Ultimately, God would punish the rapist.

In addition to being violated, women had to bear witness to harrowing sexual assaults carried out against their loved ones. Mary Smyth’s unfortunate husband, Henry, was killed near their home in Castlelyons in County Cork. The rebels then “cut off his tongue and secret members [i.e. his genitals].”Footnote 42 In another example, Martha Pigott and her grandchildren were forced to watch the “unhumane massacre” of her son, William, and her husband, John. In her deposition of October 1646, Martha clearly struggled to relate what happened: “modesty wou[l]d blush to relate it,” she said, but added that “those cruel executioners slit … [John’s] private parts in many pieces.”Footnote 43 The grotesque castrations of John Pigott and Henry Smyth, like the attacks on pregnant women, which were recorded in Robert Maxwell’s deposition (above), symbolized the drive to eliminate a future for the Protestant settler population.Footnote 44 Interestingly, in July 1647, Martha also petitioned the Westminster parliament in London. Her later narrative was less graphic and she did not mention John’s genital mutilation and humiliation. The 1647 account is so interesting for what it does not say. No doubt Martha wanted to protect her husband’s honor and masculinity.Footnote 45

One can only begin to imagine the physical pain and psychological torment that these women endured as a result of their own distressing experiences and the suffering they witnessed. Mary, the servant raped in her master’s house in Tuam, “had layn sick vpon it for 3 or 4 dayes and was in such a condition that she thought shee should neuer bee well nor in her right mynd againe the fact was soe fowle & greivous vnto her.”Footnote 46 Mary’s body may have healed quickly but she feared for her future mental well-being. Ellen Matchett’s account of her mother’s death gives voice to the extreme distress she had lived through. During the early weeks of the rising, Ellen and her family had fled County Armagh for the safety of Dublin. En route, the insurgents stripped and assaulted them, wounding her mother who, rather than risking everyone’s lives, persuaded the rest of the family to leave her behind by the side of the road. It was to Ellen’s “unspeakable grief” that she left her “wounded bleeding mother there where she dyed.”Footnote 47 Though the trauma itself was often unspeakable, Naomi McAreavey has suggested that the sharing and voicing of these stories with the commissioners who collected the “1641 Depositions,” along with other supportive networks of women, was “part of the process by which women came to terms with traumatic experiences.”Footnote 48

When viewed as trauma narratives, the “1641 Depositions” might allow us to explore the psychological impact of the war in general and sexual violence in particular and to determine the extent to which female deponents experienced what is known today as post-traumatic stress disorder or related conditions.Footnote 49 Here, however, Joanna Bourke injects an important note of caution. She argues that not “all victims of sexual violence will suffer similar forms of psychological trauma.” Thus, while recognizing the extreme distress, Bourke refers to rape as a “bad event” rather than a traumatic one that inevitably results in some sort of disorder. She suggests that experiencing a “bad event” can also “inspire creative behaviour, bolster the development of closer interpersonal bonds with allies and encourage a clearer sense of self.”Footnote 50

Did sharing “details of that fowle offence” with her mother bring comfort to Sarah Adgor? Mary told Christopher Cooe and his wife about Lieutenant Bourk’s “wicked act” but also held that as a result she would never be in “her right mynd againe.” The extent to which the “bad events” recorded in “1641 Depositions” can be interrogated to reveal a wider range of responses to sexual violence remains to be recovered. At the very least, we need to be mindful of how current understandings of the archive perpetuate the narrative of women exclusively as victims. Heeding the warnings of a generation of feminist scholars, this archive also needs to be interrogated to reveal women’s agency, their survival strategies, their active participation in protest and violence, as well as the role they played in local conflict resolution.Footnote 51 Careful thought also needs to be given to how best to capture emotion or, to use contemporary language, the “passions” —like grief, anger, and fear—linked to violence. How did these emotions foster resistance and resilience? A deeper analysis of how emotions, especially fear, were manipulated for political purposes remains to be undertaken.Footnote 52

Curation: Political Context of the Past and Present

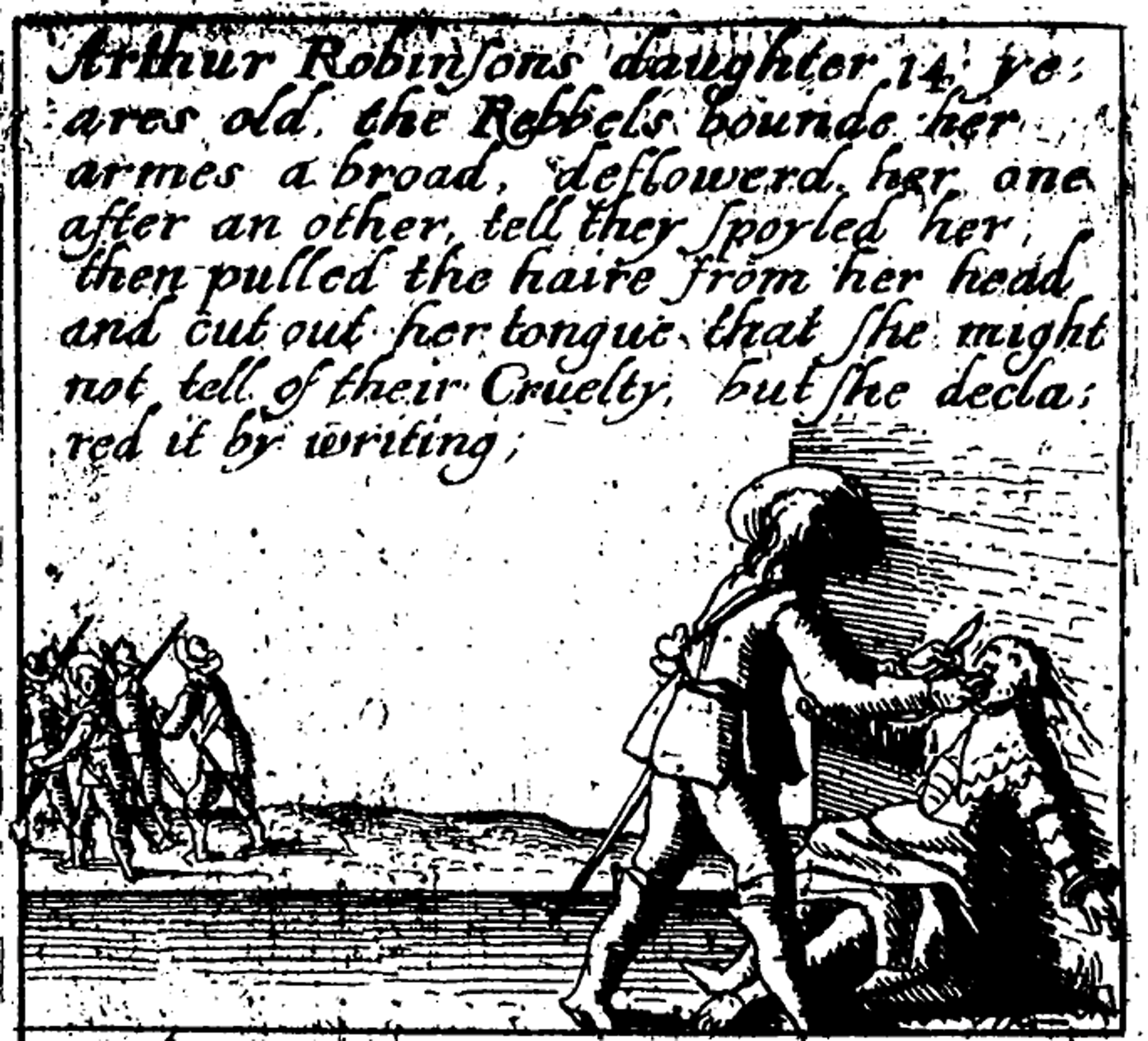

The speed with which selections from the “1641 Depositions” entered into the public sphere of print is striking. They fanned the flames of anti-Catholicism both in Ireland and in England and instilled fear as Protestant propagandists seized on accounts of sexual violence. By relating gruesome and grotesque narratives, they exploited gender to win the hearts and minds of their readers, emphasizing the vulnerability of women and children.Footnote 53 For example, James Cranford’s Teares of Ireland… (London, 1642), which was heavily illustrated with graphic woodcuts, many of which depicted naked women or others who had been raped or tortured, circulated widely and undoubtedly shaped the social memory of the 1641 rebellion. In one harrowing woodcut, a soldier pinned against a wall a young girl, with her legs spread and skirts raised, and the caption explained how the insurgents “deflowered her one after an other, till they spoyled her then pulled the haire from her head and cut out her tongue that she might not tell of their cruelty but she declared it by writing” (see Plate 1).Footnote 54

Plate 1. James Cranford, Teares of Ireland… (London, 1642).

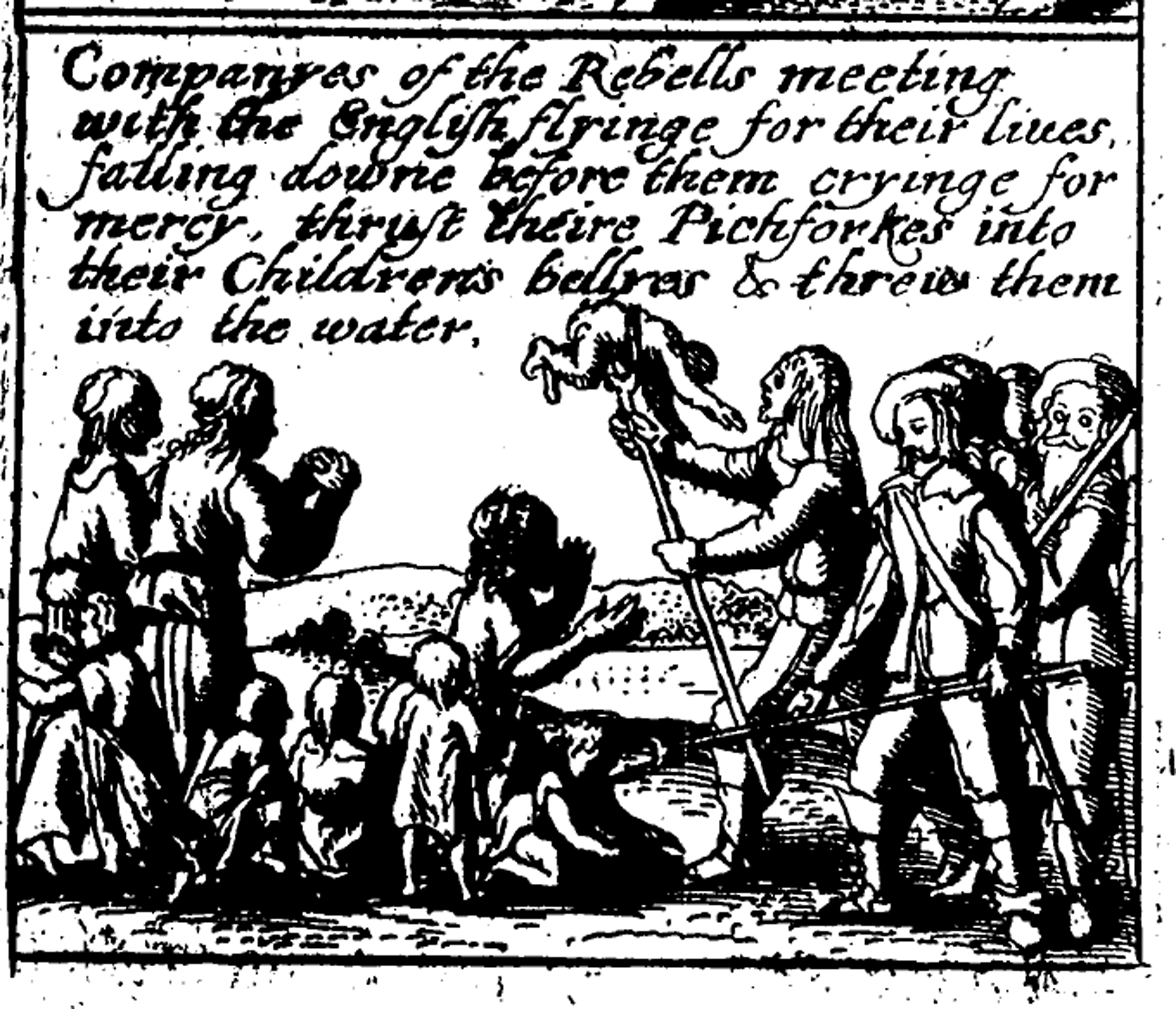

In another woodcut, Irish insurgents impale an infant on a pike in front of a group of distraught mothers and terrified children (see Plate 2).Footnote 55 Elsewhere equally disturbing images were presented—of fetuses being ripped from the bellies of pregnant women or of infants having their brains bashed out or of children being roasted on spits—that aimed to instill fear and to provoke emotional responses from audiences familiar with the Old Testament and with atrocity works that circulated widely in Ireland, Britain, and Europe, including Foxe’s Book of Martyrs or Las Casas’ Mirror of Spanish Tyranny, where children were also impaled.Footnote 56 Interestingly, John Rothwell published Cranford’s Teares of Ireland and the Lamentations of Germany (1638), which represented extreme sexual violence committed by the Swedes and other protagonists in Germany, linking the conflicts and female victimhood in the minds of the readers, as well as instilling fear and a desire for retribution.Footnote 57

Plate 2. James Cranford, Teares of Ireland… (London, 1642).

Another broadsheet from 1647 entitled A Prospect of Bleeding Irelands Miseries depicted a woman at prayer with her hair and clothing dishevelled and her breasts exposed, suggesting that she has been violated (see Plate 3). She was surrounded by corpses and speech bubbles testify to the sorrow she feels at having lost her children and loved ones. The woman represented Ireland, a country now bereft and despoiled, with families and communities completely shattered. In the text that surrounds the image, it is claimed that the Irish insurgents “have most villainously ravished virgins and women, and afterwards have bin so bloody and hard-harted, as to dash their childrens brains out.” The parallels between 1640s Ireland and the Dutch Republic are worth noting. There, too, references to rape in the legal records were rare. Yet, it did occur and instances of stripping, nakedness, torture of exposed bodies and sexual organs formed the mainstay of anti-Spanish propaganda during the early seventeenth century, much as they did anti-Irish “massacre” pamphlets during the 1640s.Footnote 58

Plate 3. A Prospect of Bleeding Irelands Miseries (London, 1647).

Of lasting significance were historical accounts, largely derived from the “1641 Depositions,” written during the 1640s and then reprinted at moments of political crisis until the nineteenth century. Henry Jones’ A Remonstrance of Divers Remarkeable Passages Concerning the Church and Kingdome of Ireland appeared in London in 1642 and reproduced (almost in full) the depositions of twenty-four women, of whom twenty were widows (see Table 2). Thomas Morley in his A Remonstrance of the Barbarous Cruelties and Bloody Murders Committed by the Irish Rebels Against the Protestants in Ireland (1644) referred in the margins to twenty-five female deponents, eighteen of whom were widows. Two years later Sir John Temple’s The Irish Rebellion was published, replete with carefully selected extracts from the depositions of thirty-three women, twenty-five of whom were widows.Footnote 59 Though the overlap between the “1641 Depositions” that Jones, Morley, and Temple reproduced was limited, all three favored widows from Ulster and exploited the trauma of Protestant women for political ends. In a fascinating study of history and memory, Sarah Covington, describing the “1641 Depositions” as dozens of “memory fragments,” has shown how Temple shaped these into social memory that, in turn, validated retribution after 1649 and across time.Footnote 60

In short, in addition to linking female victimhood and violence through the medium of print, these propagandists used stories lifted from the “1641 Depositions” to characterize the perpetrators as monstrous and barbaric. Though vulnerable, Protestant women were, according to Temple, also blessed with qualities—valor, loyalty and honor—normally the preserve of men.Footnote 61 In contrast, he demonized the “meere” Irish women, whom he represented as being as brutal and barbarous as their menfolk.Footnote 62 These women appear in the “1641 Depositions” as war mongers, “whorish women,” and “lewd viragoes.”Footnote 63 In addition to instilling terror, this manipulation allowed Temple and his ilk to advocate for a radical policy of retribution that in turn justified the expropriation of Irish land. From the seventeenth to twentieth centuries, these works, particularly Temple’s The Irish Rebellion, fed into established anti-Catholic narratives that helped to stir up sectarianism and to sustain a Protestant Unionist identity, especially in Ulster.Footnote 64

Of course, archives themselves are repositories of memory. In an insightful book on the archive of the American Civil War, Yael Sternhell notes that “archives do not simply reflect the past but actually shape the present and the future.” She continued that “Archives have the power to make myths and hide truths, to generate cohesion and fuel resistance, to valorize war and foster reconciliation.”Footnote 65 This rings so true for the “1641 Depositions.” The fact that propagandists, like Temple, ransacked and manipulated the “1641 Depositions” for political purposes was one reason behind the decision to publish the archive in its entirety. This could only happen when Ireland was at peace after the conclusion of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. The graphic and sectarian content of the “1641 Depositions” explained why attempts by the Irish Manuscripts Commission to publish them in the 1930s failed. A letter, dating from October 1935, from the Stationer’s Office to the president of the Irish Manuscripts Commission acknowledged that the censor “could not interrupt the Commission in its publication programme” but “we can visualise the mild uproar which will follow the appearance of the more gruesome of the Depositions. Anything savouring of selection would probably be disturbing, but there is something to be said notwithstanding, we think, for the exercise of the blue pencil.” The outbreak of the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland in 1968 thwarted another attempt.Footnote 66 It was a case of third time lucky.

From 2010, the “1641 Depositions” have been freely available online and between 2014 and 2026 the Irish Manuscripts Commission published them in 12 volumes. On 22 October 2010, the anniversary of the outbreak of the 1641 Rebellion, Dr Mary McAleese, then President of Ireland, launched the “1641 Depositions” website and an accompanying exhibition on “Ireland in Turmoil” in the Long Room at Trinity.Footnote 67 Though no reference was made to sexual violence, she acknowledged that “The events of 1641 have been the subject of considerable dispute and controversy. … Facts and truth have been casualties along the way and the distillation of skewed perceptions over generations have contributed to a situation where both sides were confounding mysteries to one another.” Ian Paisley, the late Lord Bannside, who during the “Troubles” had repeatedly invoked 1641 to stir up anti-Catholic sentiment, also attended the 2010 launch and responded to the website and exhibition. “Here are the tragic stories of individuals, and here too is the tragic story of our land. To learn this, I believe, is to know who we are and why we have had to witnesses our own troubles in what became a divided island. A nation that forgets its past commits suicide.” The fact that Ireland was at peace allowed public figures to make speeches like these and to embrace with such enthusiasm an historical project that until relatively recently polarized institutions of the state, its subjects, and scholars themselves. In short, with the digitization and online publication of the “1641 Depositions,” memory was finally becoming history.Footnote 68

Conclusion

While the “1641 Depositions” provide a range of original and important insights into the nature of sexual violence against women living in wartime Ireland, they are clearly complex and biased and need to be consulted alongside other extant sources. Our challenge is to look at the “1641 Depositions,” which for centuries have been subverted by sectarian polemicists and propagandists, on their own terms. To listen to the voices (and the silences) of the deponents—women like Sarah Adgor, Amy Manfin, Martha Pigott, Madeline Redman, Elizabeth Woods, and hundreds of others like them—as they shared their own stories, experiences, and memories and struggled to come to terms with harrowing trauma and extreme violence.Footnote 69

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248025101089.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research & Innovation programme under grant agreement No 101097003. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. Jane Ohlmeyer is the Principal Investigator for VOICES, https://voicesproject.ie/, accessed 13 May 2025.