The study of music and music making in nineteenth-century Australia has been a central focus of Australian musicological research since the discipline’s formalized beginnings in the mid-twentieth century. Many such studies have drawn on press archives for information about the music heard in the Australian colonies, but also the social and cultural context that surrounded music making, and its reception in a rapidly industrializing society. Since 2009, the National Library of Australia’s Trove database has made access to an extraordinary number of digitized historical newspapers available, alongside other sources like musical scores, images, books, and periodicals, greatly assisting in the continuation of this research. This review article explores Trove as a tool for research into music in nineteenth-century Australia, considering its offerings and functionality, as well as its potential for researchers through several examples of projects that have successfully exploited its resources.

When researching music and music making in nineteenth-century Australia, there is some important historical context to consider. Although the vast majority of digitized sources concern music of the European tradition, by the time the British invaded in the 1770s, the continent had been home to a wide variety of Indigenous musical practices spanning over 60,000 years, and forming part of what are today considered the oldest continuing cultural traditions in global history. These are largely oral traditions – as Catherine Ellis observed, song is itself ‘the central repository of Aboriginal knowledge’ – and thus many digitized sources relating to nineteenth-century First Nations music making tend to be themselves mediated through colonial collectors and collecting practices.Footnote 1 One of the consequences of this is that, compared to sources relating to European music, digitized materials relating to Indigenous music traditions are limited.

Even within the transplanted European musical tradition, the availability and scope of sources vary from state to state. In the nineteenth century, the singular political entity of ‘Australia’ did not exist, but was rather a collection of six individual colonies established under different circumstances with distinct histories. In fact, the notion of an encompassing ‘Australian’ national history was itself a product of the late nineteenth century, as the ‘desire for nationhood’ and need to curate a ‘proud and uplifting history’ worthy of a ‘new nation’ grew in the lead up to Federation in 1901.Footnote 2 Although many histories of the nineteenth-century ‘British world’ focus on Australia through the lens of convict transportation, only Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), was explicitly founded for this purpose. New South Wales, though settled as a penal colony in 1788, had been first claimed as a possession of the British government more than a decade earlier, and South Australia (established in 1836) was founded entirely by Nonconformist free settlers.Footnote 3 The Western Australian Swan River Colony was the first established entirely by private capital,Footnote 4 while Melbourne (then Port Phillip) was founded in 1835 on pastoral leaseholds by the children of convicts, and Victoria declared a separate colony in 1851 three months before its central region struck gold. In North-Eastern Australia, a former convict settlement on the Brisbane River became its own colony of Queensland in 1859, but with much of its administration still controlled from Sydney, it was more like a ‘branch office than a colony’ until the early twentieth century.Footnote 5

These different political and social contexts had consequences for music making in the nineteenth century. For instance, Victoria, following the gold rush of 1851, became the most prosperous colony, with a matching cultural, industrial, and population boom, which facilitated the establishment of some of Australia’s oldest musical-cultural institutions. But every colony maintained its own musical activities and institutions, influenced by differences in governance, migrant populations, and even the natural environment.Footnote 6 Equally, though many free settlers from Britain saw Australia as a fresh start, free from the poverty and social stratification of British society,Footnote 7 at the same time, Britain’s cultural influence remained strong, and many ideas and institutions were ‘imported from metropolitan society and planted in the colonial environment’.Footnote 8

Music making in Australia in the nineteenth century was, then, broadly of a ‘transplanted’ quality, similar to other settler colonial societies around the world, including the United States.Footnote 9 European music making in Australia – according to Roger Covell, in his still-landmark study – began wearing ‘a frilly bonnet and a crinolined dress and sometimes a military uniform’, with file and drum bands, or British parlour music, transplanted at the same time as the convicts developed their own distinct culture of ballads.Footnote 10 But as the nineteenth-century progressed, the musical landscape also expanded, and with faster networks of communication with the ‘old world’, Australian audiences were exposed to much of the same music as their contemporaries in Europe. A strong tradition of choral societies was modelled on those of Britain, and German migrants established their own widely supported Liedertafel societies.Footnote 11 Opera performance grew through touring companies and the efforts of local entrepreneurs like W.S. Lyster,Footnote 12 while orchestral music reached its peak in the later decades of the century, particularly following Frederic Cowen’s monumental orchestral series at the Melbourne Exhibition in 1888.Footnote 13 In all these spaces, music making was supported by an endless procession of migrant and itinerant musicians, including teachers, conductors, performers and composers, and was supported by a growing middle-class audience. Ultimately, it is clear that, as Katherine Brisbane asserts, Australia was not culturally isolated in the nineteenth century, but rather, in a prominent global financial and industrial centre following the gold rushes, much of the population expressed a strong desire for cultural entertainment, creating audiences who were both ‘cosmopolitan and discriminating’.Footnote 14

Trove

The National Library of Australia’s Trove is the most significant digital resource for any researcher working on nineteenth-century Australian music and musical life. Already in day-to-day use by practically all historical musicologists working on the region, Trove is an aggregate database and single point of entry into, at the present time, over 14 billion items held in the digital collections of hundreds of museums, galleries, libraries, and other collecting institutions across Australia.Footnote 15 Sources are grouped into nine different categories, each originating as a separate digital archiving project in the early 2000s, combined into Trove by the NLA in 2009. These categories are newspapers and gazettes; magazines and newsletters; images, maps and artefacts; research and reports; books and libraries; diaries, letters and archives; music, audio and video; people and organizations; and websites. While these categories are primarily format-based, the same items can appear under multiple categories (for example, an illustrated book may appear under both books and images).Footnote 16 This allows researchers to discover connections between objects and materials beyond initial descriptive information. By the same token, searching across categories can provide additional insights. As Graeme Skinner has described, music researchers can uncover both digitized scores and period newspaper articles and advertisements detailing a work’s performance and publication history through the same search.Footnote 17 This is useful for dating undated works, as well as providing broader historical and cultural context for otherwise poorly understood publications.Footnote 18

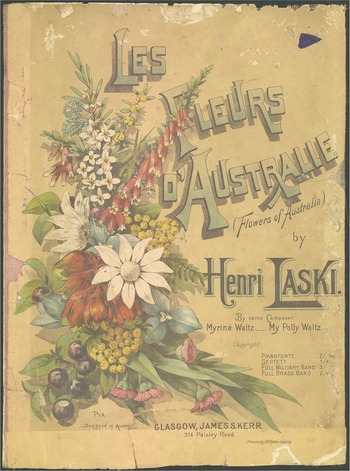

While there is potentially useful material for music research in all of Trove’s categories, the two most often used for the study of music-making in nineteenth-century Australia are the collection of musical scores and the expansive database of digitized newspapers. The NLA began digitizing its colonial sheet music holdings in 2001 as a test case for its larger digitization program. That music was chosen for this project was largely, Skinner notes, ‘an accident of its peculiar features’: the scores were out of copyright, each work usually only a few pages long, and music seen to have general historical interest.Footnote 19 Since around 2005, the NLA has also collaborated with Australian state and territory libraries to make their individual colonial sheet music holdings digitally available.Footnote 20 As a result, Trove’s sheet music holdings are expansive and comprehensive, with almost all of the NLA’s 13,000 sheet music items now digitized. Many of these sources include highly decorative cover art, and they demonstrate collectively the breadth of nineteenth-century Australian musical taste, with works ranging from imported publications to those produced locally.Footnote 21

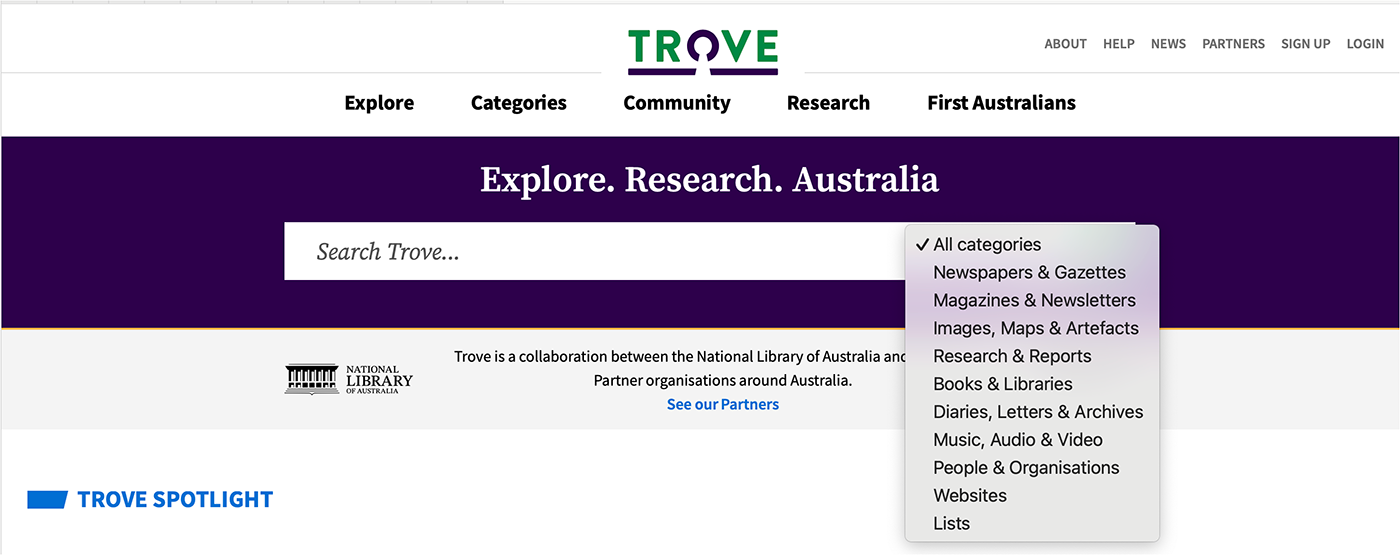

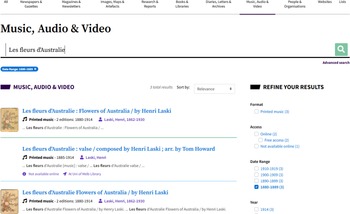

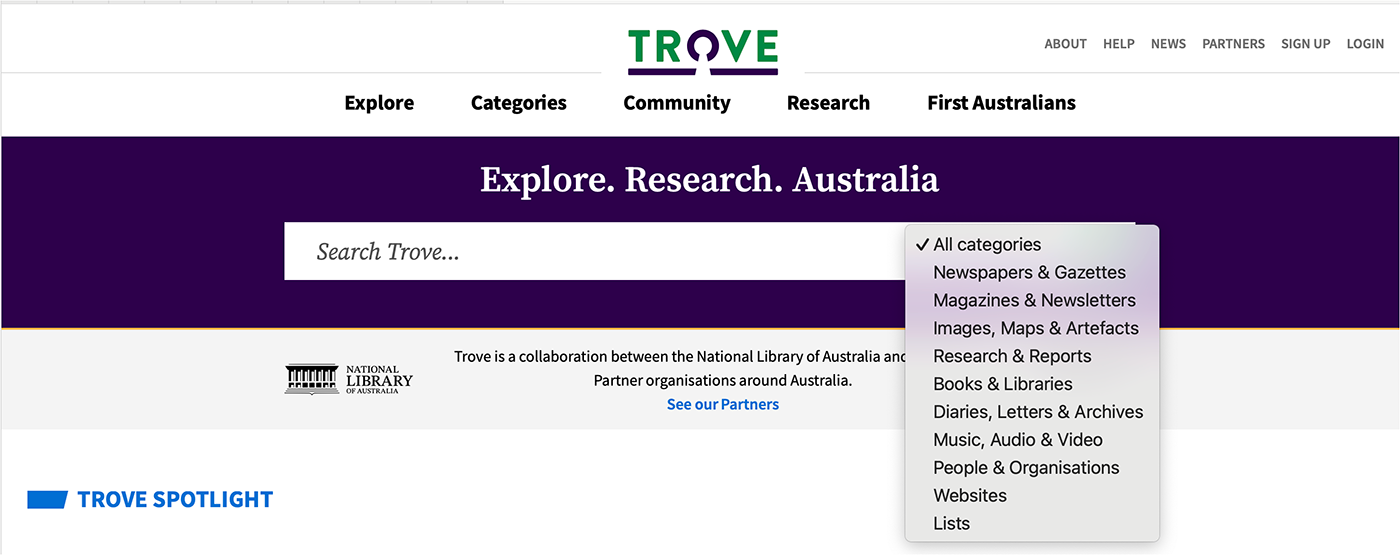

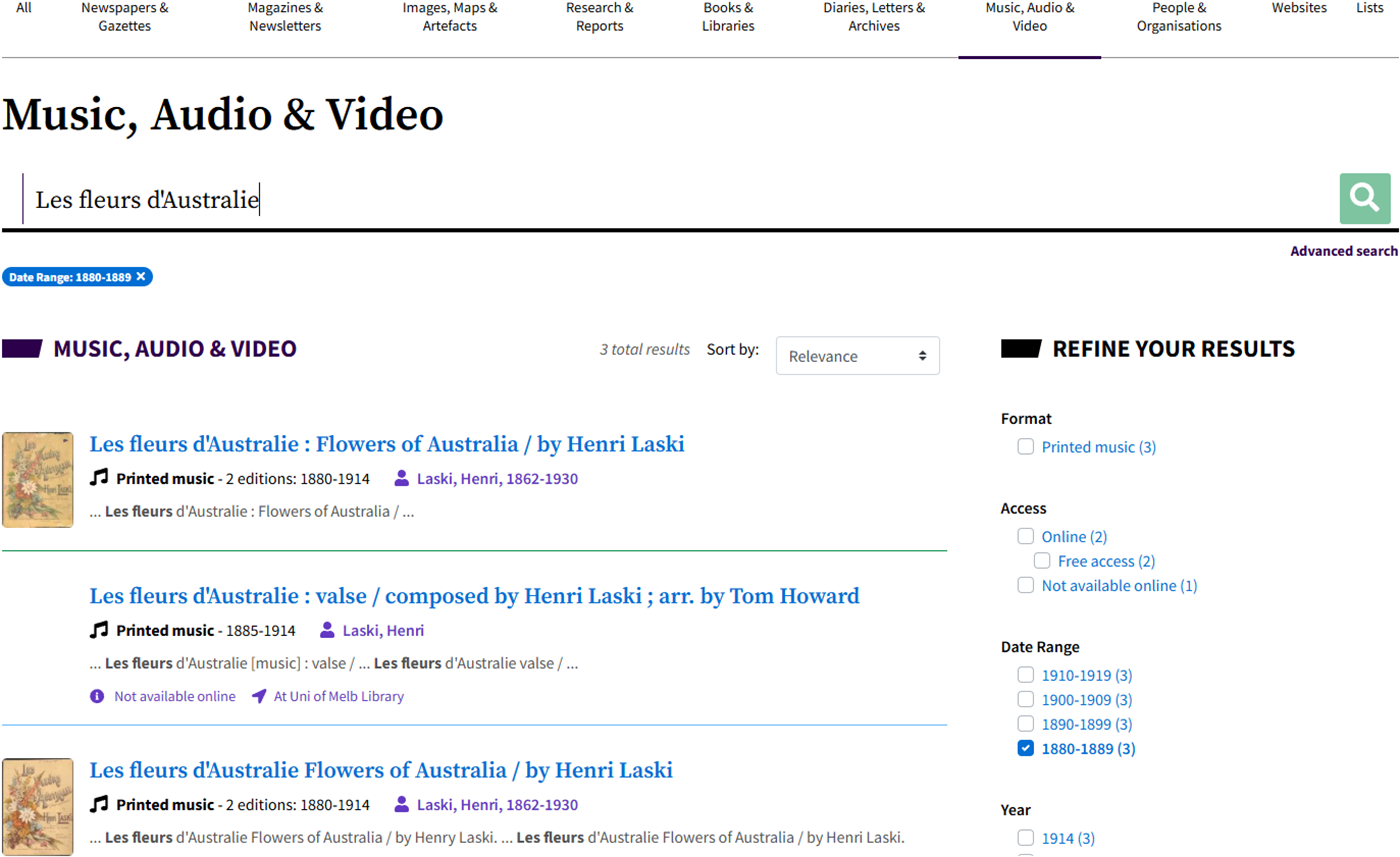

To search sheet music and scores specifically, search terms can be entered into the ‘Search Trove’ box on the front page of the website, with ‘Music, Audio & Video’ selected from the dropdown menu of categories (Figure 1). From there, searches can be further refined by filters, offered through menus on the right-hand side of the results page (Figure 2) or through the ‘advanced search’ link on the home page, allowing results to be refined by date, place of publication, format, availability (online or physical), and language. Once a particular work has been located, the ‘Get’ option links to the immediately accessible online versions of the source (Figure 3), while ‘Borrow’ lists and links to institutions that hold hard copies (though ‘borrow’ might be a slightly misleading term, as many major Australian collecting institutions require sources like these to be consulted in reading rooms on site). The ‘Buy’ category is perhaps less useful for historical sources, as it shows places where the source might be available for purchase. Further down the page, researchers can also find related materials, including user-created lists (discussed below) that include the selected record, and other editions, whether print or digitized.

Figure 1. Trove digital home page with search box where ‘Music, Audio & Video’ can be selected from the dropdown menu.

Figure 2. Search results of a Music, Audio & Video search through Trove, with filters selected from the right-hand list.

Figure 3. Digitized cover of Henri Laski, Les fleurs d’Australie: Flowers of Australia (Glasgow: James S. Kerr, 1880), accessed via Trove.

The most heavily used category on Trove, however, both in general and for music research, is ‘newspapers and gazettes’. As John Rickard describes, in nineteenth-century Australia, newspapers were ‘much devoured’, and high circulation, state-based publications were complemented by local newspapers produced in towns of almost every size.Footnote 22 Although a dedicated Australian musical periodical did not exist until 1911, with the launch of the Australian Musical News, many general newspapers had music columns and staff critics, and they regularly reported on concerts and new musical publications.

Trove’s digitized newspaper archive contains copies of publications digitized through the Australian Newspaper Digitization Program, which is a further collaboration between the NLA and state and territory libraries. Here, the NLA coordinates and provides the digital infrastructure while the state libraries collect and select newspapers of local relevance.Footnote 23 Files are generally derived by scanning microfilm copies of newspapers, and the project’s focus has largely been on publications that are out of copyright (created prior to 1955). The earliest paper digitized is the first issue of The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, of 1803, but most publications date from later in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with a few later titles included through agreements with individual publishers.

As an ongoing project, Trove’s newspaper offerings continue to expand, and as of February 2025 more than 25 million pages of Australian newspapers have been digitized. This figure, striking in itself, is even more incredible when considered in comparison to other national newspaper digitization projects in regions with historically larger populations and publication numbers. For instance, at the same date, just over 15 million pages of US newspapers have been digitized by Chronicling America, 17 million pages of European news by Europeana Newspapers, and roughly 89 million pages of UK newspapers by the proprietary British Newspaper Archive. Yet, as Katherine Bode argues, the size of such a collection does not necessarily correlate to how representative it is. The thousand or so titles currently covered by Trove is, despite including a number of complete runs, only roughly 13 per cent of all historical Australian newspapers known to have existed – a low rate that might perhaps ‘underscore the partiality’ of other global newspaper digitization projects.Footnote 24 Further, while Trove’s newspaper coverage is national, it is not necessarily uniform across the former colonies, with some of the less populated states (including Tasmania and Western Australia) better represented than those with historically larger populations. This is because, with smaller populations leading to fewer newspapers, complete coverage is more easily achieved. Trove’s coverage also, perhaps unsurprisingly, leans slightly more heavily towards metropolitan, rather than regional, publications.Footnote 25

The simplest approach to using Trove’s newspaper database for music research is through keyword searching, through the same general search box described above for finding sheet music. Trove’s default state is to search at the article level, and filters for newspaper sources – in addition to date and place of publication – allow researchers to refine by publication title as well as article-type, including (among others) advertising, detailed lists, family notices, and obituaries (Figure 4). Within each digitized article, Trove also actively encourages researchers to annotate and correct OCR texts, which in turn aids future accessibility of those sources.

Figure 4. A search for newspaper articles with the capacity to filter by publication title, article type and date.

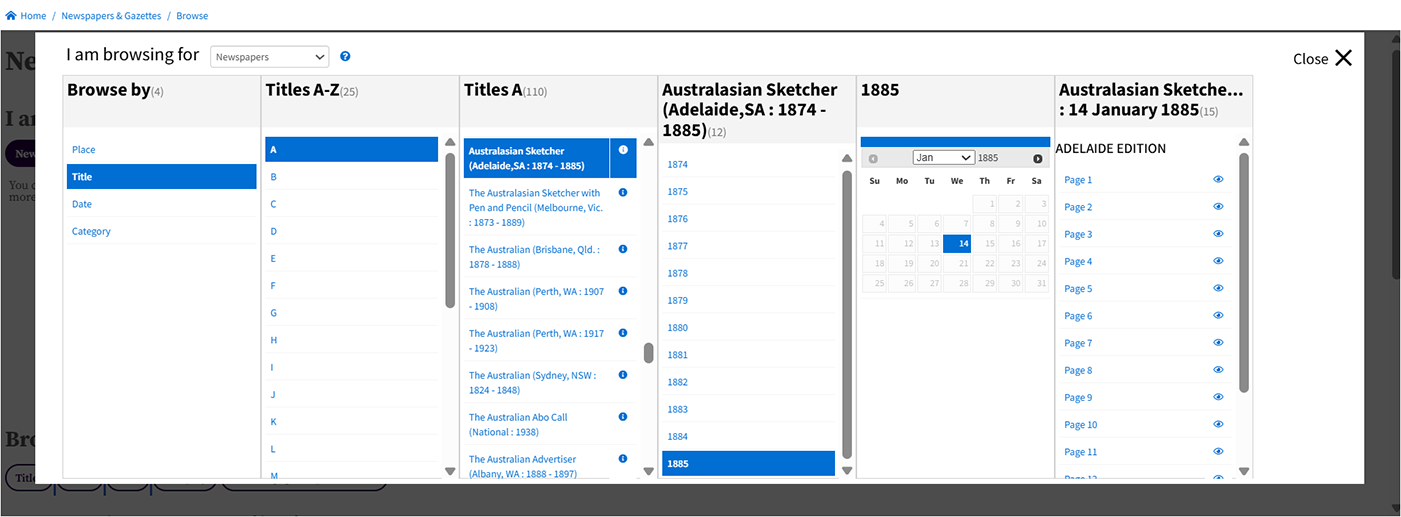

While it is also possible to browse titles, the browse interface is less user-friendly. From the ‘explore’ tab on the website’s front page, a researcher can ‘open browser’ for newspapers to browse by title, date, place of publication, or category. Selecting one of these options opens up a pop-up of nested lists: for example, when browsing by title, an A-Z list precedes a list of alphabetised titles, years, dates, page numbers, and then finally articles (Figure 5). Once viewing a particular article or page of a publication, browsing can advance through ‘previous’ and ‘next’ buttons found through dropdown links that appear when the cursor hovers over the page number, or through date breadcrumbs at the top of the article viewer.

Figure 5. Trove’s ‘browse’ interface for newspapers by title.

A further useful feature of Trove is the capacity to create lists. A user can create a private list, adding relevant records from across their Trove searches, as well as any other web resources, which can be ordered, named and described by the list creator. Building on the way Trove encourages users to collaborate, users can also choose to make their lists public, sharing their research with others as public lists appear in the same search results as other categories. There are currently 1,279 public lists described as containing material on the topic of ‘colonial music’, while a more modest 178 results appear for lists tagged ‘19th-century music’. Trove also offers the capacity to create collaborative lists, moderated by their list owners and editable by any users who have requested to join and are approved by the owner.

Projects Using Trove

Trove has become central to the research process of many musicologists working on Australian topics. It is often the first place searched for information, and one of my colleagues even described her method for finding a new research topic as ‘pouring a glass of red and plugging keywords into Trove until something interesting comes up’. Many important recent publications – though not explicitly describing the use of Trove in their methodologies – have successfully exploited the digitized newspaper database. For instance, many of the chapters concerning the performance and reception of Bach in the nineteenth century in the collection Bach in Australia edited by Kerry Murphy, Denis Collins and Samantha Owens, make evident use of the database through the particular sources cited (confirmed by conversation with several of the authors). For instance, in the first three chapters of the book, exploring the St. Matthew Passion in late nineteenth-century Australia, the authors Jan Stockigt, Alan Maddox, and Andrew Frampton all integrate their analysis with a study of the work’s reception using press reviews found through Trove, demonstrating what can be achieved through the combination of Trove’s powerful press searching tool and other archival sources.Footnote 26 In a similar manner, Laura Case’s recent article, ‘The Adaptation of Violin Playing by Indigenous People in Early Twentieth-Century Western Australia and New South Wales’ uses newspaper articles, found through Trove, in combination with other contemporary secondary literature, to explore interactions between European colonizers and Aboriginal people through the lens of the European violin at the very end of the nineteenth century. In particular, Case has uncovered important illustrative material to support her interrogation of this transculturated musical tradition, using photographs published in a number of newspapers and digitized through Trove.Footnote 27

But there are also several major research projects that make use of Trove more explicitly. Among the most prominent is Graeme Skinner’s Australharmony, itself a major research resource, building on work begun during Skinner’s doctoral studies. Australharmony documents Indigenous, settler, and visitor music and musical life in colonial and twentieth-century Australia, curating materials found through Trove and other sources to create what Skinner describes as ‘a virtual anthology of Australian colonial music and documentation’.Footnote 28 Regularly updated, and, as the all-caps headings at the top of each page notes – ‘always under construction’ – the site covers a range of materials, including an expansive bibliography and an alphabetized ‘biographical register’ of ‘musical personnel’ active in Australia, with entries on nearly 3000 musicians (linked to key documents and resources, often from Trove). Other resources include checklists of and documentary references to Indigenous song, listings of musical prints, advertisements, organizations, events, bands, original compositions, arrangements, and editions, and also links to newspaper references or other supporting documentation. Australharmony also includes specific pages dedicated to significant musical figures and events with summarized, collated, and linked resources. Skinner has also curated a selection of more than 22,000 items on Trove through the tag ‘Australian colonial music’, which can also be accessed through Australharmony, It is difficult to overstate just how spectacular a resource Australharmony is, and the work Skinner has done and freely offered to researchers in such a comprehensive way.

Beyond Skinner’s work, a number of more targeted recent publications have also explicitly made use Trove’s newspaper database. Paul Watt’s 2019 article ‘Buskers and Busking in Australia in the Nineteenth Century’, for instance, provides the first broad assessment of busking across a single country and century, using Australia as an example specifically because the necessary research was so easily facilitated by Trove. Watt’s keyword searches of ‘busking’ and ‘street music’ resulted in over 200 articles, and he used the contents to provide an account of Australian busking activity, from who the musicians were, their repertory, instruments, and economic circumstances, to their audience reception and the ‘narratives of danger, nuisance, sickness, and immorality’ that emerged in relation to busking in the press.Footnote 29 By using Trove for data collection, Watt makes clear the limitations of the approach, including that the database is not comprehensive, containing only the newspapers the NLA and its partner institutions have chosen to digitize, as well as problems with optical character recognition and misspellings of key terms. Yet, as Watt notes, while ‘the data selected for this documentary history ultimately amounts to fragmented history’, it still offers a ‘variety of views’ that can be ‘described as representative if not comprehensive’.Footnote 30

One final example of the possibilities Trove offers can be seen in a recent article by John Whiteoak, ‘Investigating “Improvisatory Music” in Australia before Jazz through the Trove Digitized Australian Newspaper Database’. In 1999, Whiteoak published his pioneering study into improvisatory music in the era before jazz, Playing Ad Lib: Improvisatory Music in Australia 1836–1970. Research for this book, and the doctorate on which it was based, was ‘undertaken via a column-by-column, page-by-page and issue-by-issue search’ of the Australian newspapers Whiteoak had access to in hard copy, or on microfilm and microfiche.Footnote 31 Revisiting this work with the aid of the Trove newspaper database using systematic keyword searching, Whiteoak was able to confirm a number of his original conclusions, backing them up with even more data. He could strengthen assertions that had previously been presented as speculative, and in a few instances, critique certain conclusions that wider searching revealed to be either lacking nuance or problematic.Footnote 32 Furthermore, Whiteoak believes one of the major outcomes of the expanded Trove-based research was the uncovering of a number of new avenues for further research, with consequences for New Jazz Studies and musicology more broadly.

With such a vast resource as Trove, coupled with projects that further bring its contents into musicological focus such as Skinner’s Australharmony, researchers working on Australian music and musical life in the nineteenth century are perhaps some of the best served in the world for digital sources. Yet, while Trove offers a powerful tool for researchers, to quote Uncle Ben in Spiderman, with great power comes great responsibility. There are many limitations to using Trove, which researchers need to approach with care. For instance, as is frequently discussed in general Victorian era historical studies, digitized newspaper databases, though now ubiquitous in scholarly practice, should not be allowed to obscure information ‘that only that un-digitized title or that unseen manuscript may be able to tell us’.Footnote 33 And as we have seen, Trove – a large-scale, multi-year and systematic digitization project – is nowhere near complete or fully representative, and we should not, as Patrick Leary warns, allow its ease of access to suppress ‘our awareness of, and curiosity about, what is absent’ from its results.Footnote 34

Further still, while there are certainly ways to work with wholly digital corpuses of data in a manner that acknowledges and accommodates the limitations of the approach (as in Watt’s article, described above), as an editor and reviewer, I am also increasingly aware of the number of articles submitted for publication that simply present a collation of information from Trove’s newspaper database, with little analysis and limited efforts to situate that raw material in any sort of argument or historical context. As Bode argues, in using any mass-digitized collection, ‘understanding the collection’s relationship to the historical context it appears to represent is essential’ and ‘documentation does not supplant the need for critical analysis’.Footnote 35 Trove is not the be all and end all, but it is an incredibly powerful tool, and one that Australians should be both proud and protective of, given the seemingly constant threat to its existence by government cost cutting.Footnote 36 It is an important resource that opens up many significant new avenues for research into music and musical life in Australia in the nineteenth century.