Pray you tread softly, that the blind mole may not | Hear a footfall.

ShakespeareFootnote 1

The real in its reality or taken as real is the real as an object of the senses; it is the sensuous. Truth, reality, and sensation are identical. Only a sensuous being is a true and real being.

Ludwig FeuerbachFootnote 2

I have discovered the organ of hearing in the common cockroach.

Gottfried TreviranusFootnote 3

The Aural Machine

In 1821, the leading music critic in Vienna, Friedrich August Kanne, reflected on why he valued music so much. What he called ‘the magic of music’ resided in its capacity to recapitulate and transform melodic figures into ever ‘new but analogous forms’.Footnote 4 The character of opening figures is pregnant with meaning, we learn, such that perceptive listeners anticipate, even venerate, their latent development as a ‘magical means’ [Zaubermittel]. Decades later, the city’s inaugural University Professor of Music, Eduard Hanslick, would likewise write of the ‘gratifying reasonableness’ found in musical structures that are ‘based on certain fundamental laws of nature governing both the human organism and the external manifestations of sound’. These relations (triangulating a network of law–organism–sound) reside ‘instinctively in every cultivated ear, which by mere contemplation immediately perceives the organic, rational coherence of a group of tones, or its absurdity and unnaturalness’.Footnote 5 For some, this perceptual ability even resided in the mechanism of hearing itself. Arthur Schopenhauer, for one, credited the auditory nerve’s ‘objective’ sentient perceptionFootnote 6 with making musical sounds uniquely suitable for supplying ‘the material to express the endless multiplicity and variety of the concepts of [human] reason’, no less.Footnote 7

Ostensibly, these paeans to instrumental music merely particularize for sound the principle of ordered magnitudes once prescribed in Aristotle’s Poetics — between the ‘parts’ of tragedy. Yet as Kanne’s case makes clear, they also answer an intrinsically human need, one arising from our mind’s ‘inner […] purposiveness’ and the expectation that art will triumph over arbitrary relationships ‘snatched from this life’. This need to order makes us human, he continues, leading us to take joy in recognition and despise randomness:

For the human mind wants to order, to form its world, and clarify the miraculous. That’s why compositions that arose from lofty masters’ quills have this character of interesting us, and fill the soul with such rare magic. Their great, ravishing power becomes explicable when one thinks that even the simple sound of a melody from one instrument has such a wonderful influence on primitive peoples; indeed, even animals can’t resist taking part. Whoever has observed the movements of an elephant at the sound of a flute, he will confess that music’s influence on animals is of the highest, most marvellous kind. The mighty animal uses the flexibility of his trunk to make known the movement of his inner nature.Footnote 8

Does it now? Here the path from human psychology to animal justification is revealing. Kanne cascades the magical effects of varied thematic recurrence down a biological hierarchy, such that the same cognitive effect, discernible in non-European listeners and elephants, marks the music and the hierarchy. In a racialized world view, all this was to be measured by the governing criterion of the human soul [menschliche Seele], as seated in the Austrian capital of Leopold II: a stark exemplification of the late Enlightenment liberal subject coupled to the high-water mark of music’s putatively most autonomous form in Viennese Classicism.

Under such logic, music shores up the identity of being ‘human’ as much as human listening authenticates the value of what great music is or should be. Being animal becomes an index for calibrating through sound the higher value of being human. If a dialectic between colonizer and colonized sees the swaying trunk as a feint, or a cognitively muted response to sounds more fully grasped by ‘higher’ life forms, a human–non-human dialectic hints at the limitation of human listening itself: music affects all ‘ears’ — an ancient, Orphic power — but unequally. In an age of imbrications between music theory and natural science, this second dialectic offers the more searching logic. Consider Schopenhauer’s parallel: he explains a disparity between human and non-human perceptual experience by reference to a theosophy of the four kingdoms: ‘The four voices or parts of all harmony […] correspond to the four grades in the series of existences, hence to the mineral, plant, and animal kingdoms, and to man.’Footnote 9 Taken literally, this analogy between frequency and world structure relativized humans’ place in both. Nineteenth-century listeners become a minor fraction, a dispensable constituent of what musical sound means in the totality of the world.Footnote 10 These contrasting logics — colonialist, humanist — are differently framed, admittedly, in their approaches to difference and contingent identities.Footnote 11 But in all this we may wonder: if only certain human ears could ‘clarify the miraculous’ or intuit music’s ‘rare magic’, when did the agents of this construction of human listening become aware of its limitations vis-à-vis non-human ears? Put more provocatively, when did a concept of animal aurality begin to denaturalize the Edenic concert? To ask such a question risks aesthetic blasphemy. It requires us to answer first how an alterity relation with ‘other’ listening bodies initially arose (prior to sound-recording technology).Footnote 12 In its most consequential terms, it also raises the prospect that an awareness of non-human listening may have had epistemic consequences, serving to challenge certitudes of human self-identity (ordained exceptionalism via an immortal soul, development of language, mental and moral supremacy) within European centres at the time.Footnote 13

For decades now, humanists have been talking about a crisis in humanistic thought. When John Blacking postulated in 1973 that ‘essential physiological and cognitive processes that generate musical composition and performance may even be […] present in almost every human’, he pronounced the matter significant ‘for the future of humanity’.Footnote 14 Yet just five years into that future, the philosopher Stanley Cavell retorted with what seemed an antagonistic question: ‘Can a human being be free of human nature?’Footnote 15 It tapped into an idea steadily crystallizing within the humanities, that we may unwittingly be slumbering in an ‘anthropological sleep’, as Michel Foucault had put it in 1966, in which ‘the pre-critical analysis of what man is in his essence becomes the analytic of everything that can, in general, be presented to man’s experience’.Footnote 16 Half a century on and the debate has broken from its humanist logics into discourses of the non-human other, from a transspecies (posthumanist) perspective on music that, for Gary Tomlinson, can reveal ‘transspecies capacities that remain to us obscure’ and inhere within a ‘general dedomestication of our own capacities’, to the ‘alien listening’ postulated by Alexander Rehding and Daniel Chua, and the ‘new bioegalitarianism’ envisioned by Rosi Braidotti, which proposes that we relate to animals ‘as animals ourselves’.Footnote 17

With critical spectacles on, then, Kanne’s ostensibly appreciative words from 1821 might seem to have aged badly. They can be read as one side of what Giorgio Agamben has called ‘the anthropological machine’, in which animals are contradistinguished from humans at the cost of certain humans becoming animal. Historically, this is a symmetrical exchange between inside and outside, inclusion and exclusion, that at once dances on the head of a linguistic pin (‘man-ape’ versus ‘ape-man’) and yet encompasses the mechanisms by which certain humans have disempowered certain other humans by assigning them to the subhuman category of ‘animal’, from the European Jew of the 1930s (or ‘non-man produced within the man’) to the slave or barbarian foreigner (‘an animal in human form’).Footnote 18 Like the posthumanist commentaries with which it resonates, Agamben’s ‘machine’ has chiefly served to reinforce the conception of an indeterminate zone between the categories of human and animal.Footnote 19

Historically speaking, nowhere was this indeterminate zone laid bare more systematically than in the advent of a modern comparative anatomy. For here the categories of animality and humanity were not obviously separable as collections of anatomical data. On this material platform, their long-standing cultural opposition started to become bridgeable, problematically so, leading naturalists such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach to argue (implausibly) that humans must be distinguished from animals by hidden physical workings, just as they were by the hidden workings of the mind and soul.Footnote 20 Each claim for shared morphology and function of body matter served as the grappling hooks of so many climber-anatomists dissecting away a taboo of cultural signification, meaning that by 1860 one of Europe’s leading anatomists could state: ‘physically, man is an animal, undeniably so’.Footnote 21 While animal–human commentaries have more recently been linked to questions of identity and difference within postcolonial and posthuman studies, the professionalization of European comparative anatomy can offer a richly documented order of knowledge for histories of listening.Footnote 22 In brief, it was formalized as a path of study in Paris during 1793, i.e. in the teeth of the French Revolution, the very year Louis xvi and Marie Antoinette were executed, a new constitution proclaimed, and war declared on the British. The Jardin royal des plantes médicinales (Royal Garden of Medicinal Plants) had been transformed into the Muséum d’histoire naturelle (Museum of Natural History) in the course of the Revolution. The Jardin’s existing officers had called for the motto egalité to be taken seriously within the new institution, resulting in the dismissal of the Intendant and — remarkably by current standards — the conversion of the post into no less than three (later four) new professorships in anatomy. Georges Cuvier (1769–1832) took up the first chair in ‘Comparative Anatomy’ in October 1802, having renamed his predecessor’s chair from simply ‘The Anatomy of Animals’.Footnote 23 The whole episode hints at the social mechanisms that could elevate an entire profession, underscoring Michel Serres’s laconic formulation that ‘with the French Revolution, the scientists came to power’.Footnote 24

Prior to this institutional footing, the discipline’s historical crux rested on an observation by Carl Linnaeus, the eighteenth-century Swedish zoologist and the first arch-taxonomist of living forms, that ‘there is hardly a distinguishing mark which separates man from the apes, save for the fact that the latter have an empty space between their canines and other teeth’.Footnote 25 Beyond this false stitch, his ensuing decision to root a ‘human’ identity not in the faculty of reason or language, in moral character (prohairesis), music, or the soul, but more flimsily in mere acts of self-recognition arguably led to a central plank in the modern construct ‘human’.Footnote 26 In Agamben’s paraphrase:

Homo sapiens […] is neither a clearly defined species nor a substance; it is, rather, a machine or device for producing the recognition of the human. […] It is an optical machine constructed of a series of mirrors in which man, looking at himself, sees his own image always already deformed in the features of an ape. Homo is a constitutively ‘anthropomorphous’ animal (that is, ‘resembling man’, according to the term that Linnaeus constantly uses until the tenth edition of his Systema [1758]), who must recognize himself in a non-man in order to be human.Footnote 27

The machine’s visual dimension — recognition, mirrors, optics, looking — seems fitting as signage that enables the taxonomia of ordered knowledge. It reflected the medium of print in which readers pored over unfamiliar animal bodies presented in lithographs and etchings (epitomized in the almost two thousand plates of the Comte de Buffon’s thirty-six-volume Histoire naturelle),Footnote 28 and in taxidermy, the 3D spectacle of choice for shop windows, exhibitions, and private homes, arguably turning the preserved animal body into a visual medium for reinforcing European expansion through the narratives it told about other global regions.Footnote 29 Yet for Linnaeus, the act of self-recognition was already ironic; for Homo sapiens to recognize themselves in non-man ‘in order to be human’ was a denial of what is physiologically similar as much as an assertion of undefinable difference. Its origin, again, was Aristotelian, for the philosopher’s History of Animals notably denied a recognizable visage to anything but humans: ‘We do not speak of the face of a fish or of an ox.’Footnote 30 For our purposes, this also has a traceable auditory counterpart in Enlightenment aesthetics, an aural ‘machine’ — adapting Agamben — a series of echoes in which ‘man’, hearing himself speak or perform, hears his own music already deformed in animal utterances and in projections about their auditory psychology.Footnote 31

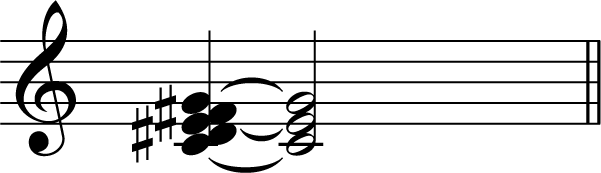

It doesn’t take long to begin revealing a genealogy of anecdotes that show the aural machine in action. To take two anglophone commentators: half a century after Kanne, the psychologist and pianist Edmund Gurney unquestioningly takes art music as a benchmark when he wonders how a gunshot (the ‘coarsest […] most excruciating sound’) can be a source of pleasure to culturally refined ears (‘or it would not be so constant a feature of modern melodrama’), while, contrariwise, the difference between a beautiful and a ‘moderately good’ soprano timbre is readily discernible even by the ‘East End roughs’ of London. His point was that all ears are physiologically equipped to support high and low cultural tastes, regardless of training, class, or colonial baggage: ‘Savages […] whose delight in what seem to us hideous noises can in no way be held to prove that they are incapable of enjoying what they have never heard.’Footnote 32 If we look back half a century before Kanne, the itinerant music historian Charles Burney proposed in 1771 that the very harshest noise is tolerable providing it resolves into concord, and posited that this principle might even supersede a logic of harmony. He tacitly drew on human hearing to rationalize the growing use of non-tonal dissonances he heard among Italian folk musicians. Like Kanne, the argument relies on a singular ear, with its corollary a set of listening techniques trained on an intentional object (the triad), to establish the limits within which the resolution of discords can take place. (Example 1 realizes his illustration: C, D♯, E, F♯, G played simultaneously on the harpsichord, where D♯ and F♯ are released first.) ‘The ear must be satisfied at last,’ he explains. ‘I am convinced, that provided the ear be at length made amends, there are few dissonances too strong for it.’Footnote 33 To ask ‘which ear?’ risks anachronism, and seems unnecessarily disparaging given both writers’ observational intelligence within their periods of cosmopolitanism. In each case, a particular kind of human listening defines the value of musical sounds in the context of European modernity, whether according to pattern recognition (Kanne), noise–tone distinctions (Gurney), or dissonance treatment (Burney).

Example 1. Charles Burney’s example of harmonies, to be played on the harpsichord, that illustrates the human ear’s tolerance for harsh dissonance providing it resolves. Burney, The Present State of Music in France & Italy, 2nd edn (T. Becket, 1773), pp. 159–60.

As for the interpretive wrapper of historians reading such sources, Tomlinson has emphasized the nature of functional tonality itself as an ‘aural habitus’, a supra-individual system based on custom. In its collective emergence among listeners of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this becomes an alibi for our three witnesses above: ‘beyond the control of individuals, growing and spreading as a network of largely unspoken and partially inarticulable preferences, a social force-field of semi-conscious priorities’.Footnote 34 The question arises: why hold historical individuals accountable for ways of listening that are irreducible to individual agency if not to align with the historian’s own ideology? What does it mean for these ways of listening to play a positive role in our cultural constitution but for them to be not merely hidden from us (the action of ideology, opposed by critique) but wholly inarticulable? On this count, the pitfall of postulating collective agency for a concept of ‘western aurality’ is the intrinsic fallibility of those humans equipped to write historical accounts of western music in the first place. Carl Dahlhaus was among the earliest to identify the ‘ideal’ listener (‘sought by historians of reception’) as a figment of our historico-analytical presuppositions, reducing it to nothing but the assumed intention behind a composer’s text; for Suzanne Cusick three decades later, the ‘ideal’ listener became a more pernicious counterpart of ‘the music itself’, that seemingly male-scientific camouflage for ‘people with the special training required to interpret meanings that are encoded in patterns of sound’ — for both, a convenience of historical method that can only deceive.Footnote 35 Either might have had in mind the archetype set out in Heinrich Schenker’s early essay on ‘Musical Listening’ (1894) for the Neue Revue, which tasked late nineteenth-century ears with the purest form of ideality. It opens:

The most perfect perception of a musical work is and remains that which not only takes in its entire tonal material, but also recognizes and tactilely feels out [durchfühlt] the compositional laws prevailing in it (unknown or familiar), the destiny of the piece, as it were.Footnote 36

Only the most gifted musicians can achieve this feat by listening, he lamented, reflecting a cynicism not of method (cf. Dahlhaus) or towards human exceptionalism (cf. Tomlinson), but simply towards fellow humans (cf. Agamben).

From ‘Our Ear’ to ‘Some Ear’

Setting aside such debates, it was precisely the relatability of body physiologies and the assumed constancy of a physics of sound that offered a basis for human–animal comparisons during the early century. Coeval with Kanne, the 22-year-old Italian philosopher and poet Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837) was also fascinated by the appeal of musical sounds, but approached them from a materialist tradition, i.e. a world view rooted in the primacy of matter. His speculations on animal hearing in his Zibaldone sought to rationalize how sounds might be understood to affect different species in the same way. Following some bluff scepticism over Kanne’s main point (‘You can see how pointless is the absolute conviction that, because music is especially pleasing to human beings, it must have an effect on animals’), he argued that different aural perceptions of the same sound must be a question of degrees of difference, not kind.Footnote 37 This left the door open to comparative (interspecies) listening, at least across minimal anatomical differences:

It is not difficult to suppose that sounds have some effect on animals, but it is not necessarily so, or necessarily the same sounds that affect people (we know that among men some nations enjoy sounds that are quite different from ours, and which we would find intolerable). Their organs and, independently of these, their whole way of life are different from ours, and we cannot know what effect this difference has. However, if it is not too great, or if there is at least some affinity with us in this respect, sound will make some impression on such animals.Footnote 38

Biographically, Leopardi was personally attuned to physiological affinities. His lifelong physical discomfort, as a likely sufferer of ankylosing spondylitis (a chronic inflammatory condition that progressively deformed his spine), resulted in ‘accentuation or remission of stimuli’, his medical notes explain, creating an unusually changeable neural platform for experiencing the world.Footnote 39 When he compared animal bodies to humans in this context, physical difference is assumed to be directly proportional to perceptual difference. (Eighteenth-century luminaries such as Johann Gottfried Herder had advocated a similar physiological determinism, but without the frame of materialism.)Footnote 40 Even for those with similar bodies, harmonic beauty was ‘never absolute’; disagreements between European music theorists arise due to potentially limitless cognitive differences, we learn, and animals too are individuals:

so even if the abstract idea of harmony could be conceived by animals, it would not follow that their ideas of harmony and beauty would be the same as ours. And so it is not music as art but its matter, sound, which has an effect on certain animals. Footnote 41

With this, the phenomenon of animal listening inaugurated a reduced field of study in which only the physical dimension of sound remains.Footnote 42 Leaving aside the postulate of ‘sonic matter’, listener psychology was unquantifiable and unknowable (especially among animals), so any tractable comparison between humans and animals would have to reside in objectively physical causes and effects: sonic vibration on physiological matter.

This new view of listening, as a physical measure of bodies, was wholly in keeping with a mechanical explanation of nature, rooted in an Anglo-French tradition of mechanical philosophers from Isaac Newton and Marin Mersenne to John Robison (1739–1805) and Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827), whose so-called ‘demon’ famously held that every event is explained by prior events acting upon it: ‘We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its anterior state and as the cause of the one which is to follow.’Footnote 43 Against this absolute causal determinism, human listening was exceptional, but not quite sui generis. Its special status was mirrored in debates over teleology (i.e. the study of final causes), for both explained events in relation to human origins rather than the pure mechanics of the universe. For philosophers like Friedrich Lange (1828–75), the problem was epitomized in Socrates’ conception of the architect of the world as a person; any form of teleological thinking could only be anthropomorphic because ‘the world is explained from man, not man from the universal laws of nature’.Footnote 44 The reason that exists in nature is fundamentally human reason, in this sense, just as the music that exists in the world is fundamentally understood only by humans.Footnote 45

If the anthropological identity being projected here was latent, for the emergent disciplines of zoology and comparative anatomy it was explicit. As Bennett Zon has shown, imagery of discrete gradations — steps, ladders, tables — had been used since the early sixteenth century to illustrate the fixed hierarchy of a ‘Great Chain of Being’, in which lower creatures precede their higher cousins, a view refined in Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s 1809 theory of progressive transformisme, the ‘transmutation’ of species from lesser to greater biological complexity, where a cumulative inheritance of acquired characteristics drives the alteration of one species into another (prior to Darwin’s theory of natural selection in 1859).Footnote 46 For musically inclined Victorians, the differing capacity of animals to make ‘music’ is the animating fantasy of this discourse; its formulations have been well documented by scholars like Zon, who traces those theological naturalists inclined to assign birds an animal soul corresponding to their relative musical abilities, and like Rachel Mundy, whose critique of how cultural categories are assigned indicates that theories of musical evolution often covertly became ‘a means to debate the right to personhood’, with song itself ‘a measure of other species’ worth’.Footnote 47

But this is not an article about animal music; it is about an awareness of non-human listening among European commentators. Since the mid-eighteenth century, the Chain’s hierarchy was faithfully reflected in the progressively limited auditory abilities naturalists ascribed to animals. This extended from the Scottish surgeon John Hunter’s (1728–93) thoughts on hearing in fish, as ‘a link in the chain of the varieties in this sense in different animals, in which there is a regular progression, viz from the most perfect animals down to the most imperfect’, to the Harvard zoologist Louis Agassiz’s (1807–73) later pronouncements on the entire kingdom, where hearing mechanisms are ‘more and more simplified, as we descend the series’.Footnote 48 In a sense, the discussion below tracks the breaking down of this way of thinking during the mid-nineteenth century. It traces the processes of discovering and reflecting on new understandings of how anatomical and physiological differences between species were thought to determine perceptual difference. Above all, it asks: when did the penny drop that human hearing was neither the only aural reality nor necessarily the ‘highest’ or truest in the natural world?

For the biologist Thomas Huxley (1825–95) in 1863, this was ‘the question of questions for mankind’, namely ‘the ascertainment of the place which Man occupies in nature and of his relations to the universe of things. Whence our race has come; what are the limits of our power over nature, and of nature’s power over us.’Footnote 49 A shifting perspective is already evident in British definitions of music in the wake of evolutionary theory. Charles Darwin, who derived ‘intense pleasure’ from music but once confessed ‘I am so destitute of an ear, that I cannot perceive a discord or keep time’, would argue in The Descent of Man (1871) that, in principle, any ear able to discriminate between multiple sounds is one that is also sensitive to musical notes.Footnote 50 The capacities are two sides of the same coin, in other words. By the end of the century, the English musicologist W. J. Treutler appeared to bridge the positions above in a kind of interspecies aesthetics, telling the Musical Association in London that

for our purpose we may define music as a succession of sounds so combined and modulated as to please, not only the ear — our ear — but some ear; that is the fundamental idea — the object of music is the gratification of the sense of hearing.Footnote 51

A consequence of this zoological episteme was that the emergent scene of a professional comparative anatomy afforded musicians and scientists a basis on which to understand their auditory environment as quantifiably distinguishable from that of animals, and that in turn afforded critical distance from their own auditory environment for the first time. Here we are faced with a slow process of self-alienation by which certain human listeners, encountering a concept of animal aurality, became newly distanced from their own ‘musical’ auralities, making it possible to stir, if not quite awaken, from their anthropological sleep.

In what follows I argue that this process of aural self-alienation can be attributed in large part to a new order of physiological self-knowledge emerging from comparative anatomy. That is, physiological properties of the human subject became important aesthetic, philosophical, and critical questions thanks to thinkers like Ludwig Feuerbach and Karl Marx, thereby establishing the conditions for the idea that animals with physical organs and their own physiologies were also to be implicated in those same aesthetic, philosophical, and critical questions. As we shall see, this comparative logic bears witness to the aural machine’s role in establishing an ‘indeterminate zone’ between the categories of human / animal listening.

Feuerbach’s Anthropological Materialism: ‘I […] Make the Ear Divine’

Hitherto, the bodies registering sound stimuli we have been tracing are all human. Historically, this bias becomes explicable when we consider that it was Feuerbach’s Critique of Hegelian Philosophy (1839) and his subsequent Principles of the Philosophy of the Future (1843) that first broke with Hegel to establish a widespread philosophical materialism rooted in human perception, exerting ‘a powerful and immediate influence’ in the literary centres of the German Federation.Footnote 52 Intellectual historians have long acknowledged that his impact on European thinkers such as Marx or Ludwig Büchner was profound, for he established a relation between philosophical theory and human activity, experience, and culture, thereby ‘turn[ing] philosophy first into a critique of philosophy itself’, in Mark Wartofsky’s paraphrase.Footnote 53 Less appreciated in this epistemic move is the amplified role it created for humankind. ‘The new philosophy’, Feuerbach asserts in Principles, ‘makes man, including nature (as the basis of man) the sole, universal and highest object of philosophy, that is, anthropology including physiology becomes the universal science.’Footnote 54 As is well known, his outlook was conceived as a release from captivity, his writings a coiled spring finally loosed from the caged abstractions of Hegel’s Berlin lecture theatre. He remonstrated against a dualist world view whose mental side had been sustained by an immaterial God and the ‘logico-metaphysical shadows’ of idealism, in which the essence of God and that of speculative thought are held to be synonymous:Footnote 55 ‘God is pure spirit, pure essence, and pure action […] without […] sensation, or matter. Speculative philosophy is this pure spirit and pure activity realized as an act of thought — the absolute being as absolute thought.’Footnote 56 To renounce immaterial speculation meant embracing a cluster of concepts newly revised as modern: scientific approaches to tactile, anatomical flesh; human bodies’ relation to the environment; and the agency behind mechanical acts of perception. ‘What is light […] without the eye? It is nothing’, Feuerbach observes. ‘Only the consciousness of seeing is the reality of seeing or real seeing.’Footnote 57 Epistemologically, this proto-ecological outlook represented a profound turn away from systematic idealism. In contrast to a metaphysical theology that regarded God as a ‘pure object of the mind’, it was modern man who now occupied the rhetorical centre ground, chiefly as an object (and agent) of sensory apparatus, whose field of comprehension, as well as his immediate reality, was defined by the perceptual acts he was able to accomplish.Footnote 58

Once born, this ostensibly liberating idea was immediately vulnerable to co-option in divergent directions. (Its appropriation by different actors reflects individuals’ mistrust or confidence in their sentient kin, exemplifying the reflexive principle that accounts of encroachment between animal and human categories convey as much about how the narrators view their own humanity as they do about their attitudes and relations to non-human animals.)Footnote 59 To start with the negative side, it would become twisted in Arthur de Gobineau’s biological world view as a means of contradistinguishing races in his Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines of 1853–55:

I have shown the unique place in the organic world occupied by the human species, the profound physical […] differences separating it from all other kinds of living creatures. […] The immense superiority of the white peoples in the whole field of the intellect is balanced by an inferiority in the intensity of their sensations. In the world of the senses, the white man is far less gifted […] so is less tempted and less absorbed by considerations of the body.Footnote 60

It is indicative of the frailty of such a baseless supposition that it would be precisely inverted by fellow racial theorist Francis Galton in 1883: ‘A delicate power of sense discrimination is an attribute of a high race.’Footnote 61 On the more positive side, the physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach would write in 1866 of humans’ innate capacity to train sense acuity by attention, practice, and habitual activity within an environment: ‘The sense acuity of Indians, instructed on nothing but natural objects, has already become proverbial.’Footnote 62 His ‘well-practised ear’ (das wohlgeübte Ohr, an unapologetic riff on the Well-Tempered Clavier) advocated the benefits of aural training inspired by this idea; even simple experiments in dyadic intervals and harmonic progressions show that ‘the same sentient object can give rise to quite different perceptual experiences’,Footnote 63 and since his purpose was pedagogical, he proceeds to make the obvious point:

The ear is able to fix individual sounds just as the eye orientates itself by particular points. […] Not everyone knows how to follow a symphony in its individual voices. The musician must learn to listen, as the painter learns to see.Footnote 64

Beyond the historical orbit of Mach’s ‘physical music theory’ (physikalische Musiktheorie), even a brief look forwards at the correspondence with Steven Feld’s celebrated call for an acoustic epistemology, or acoustemology (that echoes ‘how sounding and the sensual, bodily, experiencing of sounds is a special kind of knowing, or put differently how sonic sensibility is basic to experiential truth’), indicates that a human-universalizing impulse remained embedded within the ethnomusicological toolkit of the 1990s (here regarding the Kaluli people).Footnote 65 Feld has since opened up the concept as a broader relational ontology, applicable to interspecies and posthuman logics — ‘life is shared with others-in-relation’Footnote 66 — but this extendibility only underscores that the sustained anchor of Feuerbach’s anthropo-physiology bears historical consideration across potentially wider periods and disciplinary grooves than its reception suggests.

As an avowed monist, Feuerbach’s broader aim was to bridge the Cartesian divide by positing humans as nothing less than ‘the living superlative of sensualism, the most sensual and sensitive being in the world’.Footnote 67 This impulse aligned his writings with the ongoing achievements of the natural sciences in understanding knowledge through the mechanics of sensation. Human aurality was implicated from the outset. As though responding to Feuerbach, Richard Pohl’s introduction to his eight Akustische Briefe (1852–53), serialized in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, positioned the link between sentient mechanism and mind as critical for understanding modern aesthetics. He recapitulated Kanne’s point about pattern recognition, that the human mind instinctively ‘searches for the law to which [similar phenomena] are all subject’, and had no qualms about recognizing that the entire world of appearances rests on the ‘unmovable basis of general mechanical principles’,Footnote 68 continuing:

If we claim that the arts, as a product and excursion of the human mind, stimulated by sense impressions, calculated on sense impressions, and using the means that material nature offers us to do so — that the arts must ultimately also be included in this cycle of cause and effect, in this law-governed context of natural phenomena — is this claim not still met with dissent from all sides? No matter; the ultimate purpose of these letters is precisely to demonstrate the necessity of a law-governed connection between natural phenomena and mental activity in relation to music. Footnote 69

Writing in Feuerbach’s shadow, Pohl explicitly linked this musical turn to a schism in human identity; mechanism might explain sentient perception, even cognitive activity (for materialists), but Geist alone explains artistic creativity. In moments of creativity, we see and feel ‘the artistic achievements of divine, Promethean sparks in humans, there where something comes into being from the apparent void and the “animation” of matter begins — there calculation and explanation stop — there we feel that we are human’.Footnote 70 That is, not animal, whose status as bête-machine had been stable since Descartes. The creative agency that, for Pohl, was still irreducible to Hegelian Geist (and correspondingly nostalgic), for Feuerbach was expressed differently: as human consciousness. They were parallel but not synonymous. Far from a retreat into idealism’s abstractions, this built on Feuerbach’s view that human sensing was never merely the product of mechanical causality. It always went hand in glove with mental agency: ‘thinking as such is present and active in all the activities of our senses’, he asserts in 1835, where sensation, correspondingly, is understood as ‘reason identical with our unmediated, individual senses, or personal sensate reason’.Footnote 71 Mentally alert listening thus constituted a force of consciousness enabled by one’s physiological condition, whether in contemplating the thematic permutations of a keyboard sonata or in the abstract task of perceiving objects ‘as differentiated from ourselves’.Footnote 72 What Pohl’s critique reveals is that Feuerbach was only one among a number of ‘individual voices […] forging energetically forwards’ in pursuit of an uneasy integration of physical causality and music aesthetics.Footnote 73

Away from music, Feuerbach’s prestige — and notoriety — for tarnishing Hegel, his erstwhile teacher in Berlin, was famously immediate: ‘We all became at once Feuerbachians’, Friedrich Engels recalled of his intellectual patricide.Footnote 74 That his ideas immediately spilled over into the political sphere underscores their attractiveness in Nachmärz circles beyond theology and aesthetics. Already in 1845, Marx and Engels would write of ‘the real individuals, their activity and the material conditions under which they live’ as first premises for their newly minted materialist conception of history. With historical distance, this now reads as a first shoot growing from the strengthening tree of Feuerbach’s anthropo-physiology:

The first premise of all human history is, of course, the existence of living human individuals. Thus the first fact to be established is the physical organisation of these individuals and their consequent relation to the rest of nature […] Men can be distinguished from animals by consciousness, by religion or anything else you like. They themselves begin to distinguish themselves from animals as soon as they begin to produce their means of subsistence, a step which is conditioned by their physical organisation. By producing their means of subsistence men are indirectly producing their actual material life.Footnote 75

Consider the reactionary chain that preceded this centring of ‘material life’. If Hegel’s Aesthetics had foretold the ‘end of art’ in the early 1820s, predicting a chilling segue from artistic creativity to ‘intellectual consideration […] knowing philosophically what art is’, Marx’s doctrine of historical materialism, connecting historical change to productive forces, presided over the ‘end of philosophy’ itself in 1845.Footnote 76 While his historical materialism separates from a strictly philosophical materialism thereafter, their common root in human physiology — an ‘anthropological materialism’, as Alfred Schmidt memorably put it — is clear.Footnote 77

Marx acknowledged as much. He maintained that human sense acuity has both been shaped by and has shaped our social and civic developments (‘a musical ear, an eye for beauty of form — in short, senses capable of human gratification […] the forming of the five senses is a labour of the entire history of the world down to the present’), marking them out, on the grandest of terms, as a newly burnished index for an undocumented human past.Footnote 78 This was one reason why Foucault regarded Marx as the first epistemological mutation of modern history.Footnote 79 Rather than being just a physiological trace of societal toil, the human senses, in Marx’s bio-historical construct, now presented the possibility of a dialectic between identity and acuity that laid claim to what was perceptually and psychologically ‘real’, no less, for individuals:

Man’s human relations to the world — seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, feeling, thinking, observing, experiencing, wanting, acting, loving — in short, all the organs of his individual being […] are in their objective orientation, or in the orientation to the object, the appropriation of the object, the appropriation of human reality.Footnote 80

Logically, this appropriated reality was deterministic and hence infinitely changeable (in nuce: different acuities create different realities), for the proposed capacity of ‘organs’ to determine or manipulate one perceptual reality presupposes the existence of others, an insight prescient of writings about diverse animal sentience in the ensuing decades. Thus what was initially envisaged (by Kanne, Feuerbach, et al.) as a singular perceptual reality for humans carried a latent pluralism from the outset. Critically, this remained fixed for individuals in the absence of physical change. Marx rejected the idea that the limitations of consciousness are removed simply by seeking to swap one kind of conscious perception for another, in effect by thinking oneself into another reality: ‘This demand to change consciousness amounts to a demand to interpret reality in another way, i.e. to recognize it by means of another interpretation.’Footnote 81 The sentient grounding of German philosophy c. 1845 was never subject to abstract volition, in other words, which made it all the more appealing as an object of study vis-à-vis Darwinism, as Marx later acknowledged in Das Kapital (1867).Footnote 82

Ears did not escape this epistemic change. The episteme being inaugurated here makes the turn from (divine) abstractions to (human) sense immediacy (Feuerbach’s ‘humanization of God’)Footnote 83 pivotal for those contemporary writers who understood music as a sensate, intentional object, permitting Feuerbach, in an aside, to note without profanity: ‘If I make the tone divine, I also make the ear divine.’Footnote 84 The terms of this divine ear were ‘limitless’ vis-à-vis animals, as we shall see, for its status was inherited from an unseated God, chronologically and epistemologically, so it retained a double trace of man’s theological origins in Derrida’s sense of a ‘simulacrum of presence that […] refers beyond itself’, i.e. where the trace of godliness can simulate a presence in human aurality without being a presence.Footnote 85 Yet it was also now explicitly the object of a concretizing sensory outlook.Footnote 86 What this paradox meant for musical readers of Feuerbach, from Richard Wagner to Felix Mendelssohn, Pohl to Franz Brendel, is that a human outlook remained an essential framework in these debates, and — correspondingly — human listening was sovereign.Footnote 87

Animal Sentience: ‘A Mystery Impenetrable to our Intellect’

If Feuerbach’s writings had made the categories of God and ‘man’ continuous, the agents of comparative anatomy achieved the same for the categories of human and animal. Archeologically, this parallel exchange bears some consideration, for each are moments of theoretical transformation that established a new perspective. But where did they connect? In 1878, the English psychologist and Helmholtz student James Sully (1842–1923) drew out the implications for music: ‘The facts of comparative anatomy would seem […] to support the hypothesis that sensibility to musical tone extends through a much larger number of species than those known to be musical.’Footnote 88 Helmholtz himself was doubtful, and joked in private correspondence about an ongoing zoological obsession among his physiologist colleagues.Footnote 89 Yet given the widespread consensus after Sensations of Tone (1863) that pitch and melodic relationships are sensible via the mechanically predictable behaviour of the organ of Corti, mammals with developed cochleae were by anatomical class endowed with the ‘physiological basis of musical sensibility’, according to Sully, while reptiles and amphibia, having no less rudimentary cochleae than birds, must by similar logic be possessed of only ‘a latent sensibility to tones and melody’.Footnote 90

Paradoxically, naive deductions of this sort drew authority from the cutting edge of empirical knowledge. Sully argued that since avian and human ears obeyed the same physiological principles, avian melodies too were explicable by Helmholtz’s recently minted ‘affinity theory’, a principle for determining pleasing melodic intervals based on the presence of at least one common overtone between adjacent pitches:

The harmonic affinities of notes are clearly perceived and selected by most singing birds. Thus among the commonest intervals are the fifth and fourth, both of which are marked by the presence of a common partial tone.Footnote 91

Sully had studied with Helmholtz in Berlin during 1871–72, and proudly noted their attendance of Wagner operas together.Footnote 92 Beyond a master–pupil influence, his ready attribution to birds of a physiological music theory laid bare the relatable forms between living bodies now viewed as material assemblages (and inviting casually inductive comparisons such as ‘primitive human melody was probably inferior to that of many [modern] birds’).Footnote 93 It was a levelling gesture between all organic bodies, in other words, that played into a ‘presumptuous priority’ of psychophysiology over history that Benjamin Steege has identified as a hallmark of Helmholtz’s early reception.Footnote 94

Behind Sully’s claim for mental faculties was arguably a deeper presumption concerning sensationalism, i.e. the long-standing belief that all knowledge originates with sense stimuli, which was now cautiously being extended to animals. Since the early seventeenth century, the Anglo-French doctrine of sensationalist psychology had held that all ideas or thoughts were less-perfect copies of immediate physical sensations. In this context, anatomists from Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802) to the Gallic triumvirate of Pierre Cabanis (1757–1809), Lamarck (1744–1829), and Cuvier shared a common theoretical inheritance in which the sensationalist interpretation of ideas meant the mechanism of animal cognition was similar to human cognition: ‘thus no insuperable metaphysical or psychological barriers separated men from animals’, as Robert J. Richards summarized.Footnote 95 Human acts of knowing, including — at a push — listening to melodic figures in Vienna or folk harmonies in Naples, drew on precisely the same resources as animals, in such a view, even while no anatomist could deny that sense acuity in animal bodies was determined in ways particular to their anatomy.

Historically, the underlying discourse was Aristotelian (De sensu), and even before John Locke’s canonical formulation of it in 1689,Footnote 96 it was frequently transmitted by scholastic thinkers through the Latin catchphrase ‘Nihil est in intellectu quod non prius fuerit in sensu’ [‘there is nothing in the intellect that did not first originate in the senses’]: from Thomas Aquinas’s De veritate (1256–59), where it concerned the gradual transfer of ‘things’ from their own ‘material conditions to the immateriality of the intellect, by means of the immateriality of the senses’, to Valascus de Tarenta’s Philonium (1418), where it emerged specifically in the context of deafness.Footnote 97 By the later nineteenth century, anatomically schooled materialists took up this notion (and this phrase) with almost undignified alacrity, as though its heritage were a vindication of their outlook.Footnote 98 Yet as the case of Erasmus Darwin shows, mere belief in sensationalism didn’t lead to greater knowledge of animal sentience. His tract on ‘the essential properties of bodies’, Zoonomia (1794), is an example of a foundational text that emanates from this sensationalist tradition yet fails to draw any conclusions about sensory acts of knowing, leaving unmet the challenges of how to establish the limits of animal sense or the threshold between sense and signification — what would later become the field of biosemiotics.Footnote 99 He simply rooted both in the sensorium, defined as a watery ‘spirit of animation’ (a fluid substance flowing through the brain and nerves, cleansing the muscles) coupled to neural sentience, or ‘the medullary part of the brain, spinal marrow, nerves, organs of sense and of the muscles’.Footnote 100 This flagrant lack of specificity about where the mechanisms of sensation imbricate with perception — the interface of sign and biology — is characteristic of a range of early nineteenth-century writings. It reminds us that by the early 1800s, anatomical drawings and language, what Michel Serres once called ‘the empire of signs’, was an ageing dominion of knowledge that excluded the experience of bodies, leaving the experience of sensation, and the possibility of their own codes of meaning, inscrutable.Footnote 101

Cuvier, the ‘father of comparative anatomy’, was cautious from the outset.Footnote 102 Materialists’ scrutiny of fibrous neural mechanisms offered no route to understanding sentience, he warned. Like Darwin, he sidestepped attempts to explain ‘the production of a sensation’ itself, calling it ‘a mystery impenetrable to our intellect’; after all, empirical work on animal bodies could yield no answer, so any theoretical speculation remained ungrounded.Footnote 103 His vast taxonomy of animal forms, Le Règne animal (1817), which ensured his pre-eminence within the French life sciences, noted only that both internal and external organs were permeable by particular kinds of sensation or irritation. Amid his typological endeavour, then, there was no attempt to understand animal ears or eyes as the generator of particular sentient experience; the absence and presence of organs was merely a fact of classification (‘many animals have neither ears nor nostrils; several are without eyes, and some are reduced to the single sense of touch, which is never absent’).Footnote 104 Detecting a cochlea, oval window, auditory meatus, or chain of ossicles mattered insofar as it affected form, and hence schematic order. The problem, in short, was that while sensationalism implicated animal anatomy within the same epistemic order that held sense acuity to be the governing framework for (human) aesthetics, the lack of any means for ascertaining the experience of animal sense modality or acuity meant that anatomists with reputations to defend, such as Cuvier, felt it safer to give up any pretence at understanding it.

Signs versus General Laws

After this failure of physiological anatomy, it may be no coincidence that a semiotic theory emerges at precisely this time of need. As is well known, a theory of the sign character of sentient experience would first emerge in 1867, with Charles Sanders Peirce’s ‘New List of Categories’, which set out from the premise that ‘conceptions’ exist to reduce the plethora of sensory impressions to unity, whose necessity for understanding the content of consciousness validates those particular conceptions.Footnote 105 By introducing ‘a concept of gradation among those conceptions which are universal’, Peirce famously proposed a framework (initially likeness, indices or signs, general signs; later icon, index, symbol) to systematize the content of conscious sense impression according to a theory of three kinds of representation. While these conceptions sought universality without specifying the human limits of that universality, their initial explanation via verbal syntax indicates a ‘human’ universality in Feuerbach’s sense: ‘The unity to which the understanding reduces [sense] impressions is the unity of a proposition. This unity consists in the connection of the predicate with the subject.’Footnote 106 With common verbs like ‘to be’ (as in ‘The stove is black’), the potentially indefinite determinations of the predicate led Peirce to realize graphically eight ‘possible extensive relations of subject and predicate’, sketched in the early 1860s (see Figure 1), underscoring how these different kinds of relation subsisted initially within the computational potential of language rather than in suppositions about the mechanisms of neural stimuli.

Figure 1. Charles Sanders Peirce’s graphic realization of the permutations for all ‘possible extensive relations of Subject and Predicate’, via the geometric relationships of blue and red signs, c. 1864. Source: Houghton Library, Harvard University, bMS Am 1632 (927). Used with permission.

Nevertheless, his semiotic theory would later be applied to understandings of the history of sense mechanism, most notably in Tomlinson’s recent trilogy of texts on evolution, setting out from his multi-disciplinary study of the evolution of human musicking, A Million Years of Music. Footnote 107 Here, building on the work of anthropologist Terence Deacon, Peircean semiotics affords an alternative to tracking developmental laws (after Cuvier et al.), namely by refining extant theories of ‘symbolic cognition’, or the evolved capacity of hominins to make symbols or create meaning in relation to the sign character of stimuli received. This is specifically construed as ‘meaning, reference and referentiality, and representation’, and Tomlinson is careful to differentiate the sign-making of some animals from the simple processing of ‘contentless […] information’ by all living things in order to ‘distinguish discrete processes and levels of complexity involved in organismal response and cognition’.Footnote 108 In other words, Peircean methods have led to a call for so-called ‘phylogenetic cognitivism […] to include […] accounts of the emergence of the modern human mind’, with an obvious corollary in modern human listening.Footnote 109

Specifically for a theory of evolution, this symbolic cognition is refined to account for listening practices, where sound (ostensibly a signalling device) points to no sign, just as Feuerbach’s human sentience points to no environmental need; Tomlinson’s key insight is the notion of ‘an indexical systematicity’,Footnote 110 i.e. a capacity of hominins to adapt the semiotic system of creating meaning from indexical gestures that point to the presence of a thing (‘ancient gesture-calls’) to a system of discrete pitch organization, i.e. a set of sonic references that have become abstracted from whatever they initially pointed to, therefore leaving quasi-indexical signs without any symbolic value: ‘For hundreds of millennia and across at least several species [of hominins], the elaboration of indexicality toward greater complexity, precision and ordering predominated, with little or no trace of symbols.’Footnote 111 Nearly two centuries after Peirce, this adaptation of semiotics allows Tomlinson to postulate categorical differences in the sign-making capacity of humans in an otherwise continuous phylogenetic history. Okay, you say, but to what extent does it apply to animals?Footnote 112 Here Cuvier’s problem returns. On the one hand, for theorists Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb, the abstraction of symbolic value from a stimulus is a ‘diagnostic trait of human beings’; on the other hand, the perception of likeness or iconic similarity (Peirce’s first kind of representation) is ‘shared by a wide array of cognizant species, in principle by any organism with a neuromuscular system’.Footnote 113 From today’s perspective, semiotics demonstrably provides an intellectual framework for animal sentience, then, and while its dissemination as an intellectual proposition emerged in the decade of Tristan und Isolde, there are no traceable points of contact with the early discipline of comparative anatomy (which, again, perhaps reflects the habits of exclusion in Agamben’s machine, where all semiotics implicitly focused on modes of representation for highly educated humans).

So what, if anything, was the role of Cuvier’s work in shaping musicological knowledge, given the absence of a method to assess the sign character of sentient experience? If he can be said to have had an influence on nineteenth-century Musikwissenschaft at all, it concerns his advocacy of natural laws. His opening sentence defined the project of comparative anatomy as ‘the laws of the organization of animals, and of the modifications which this organization undergoes in the various species’.Footnote 114 Seventy years later, the stated principles underlying Guido Adler’s (1855–1941) influential prospectus for musicology in 1885 would see ‘the actual focal point of all music-historical work’ as ‘the investigation of the laws of art of different periods’.Footnote 115 His ensuing history of tonal music (Der Stil in der Musik) famously grouped works (qua organisms) into stylistic periods as ‘a plurality of individual organisms whose exchangeable relations and co-dependence form a whole. Here law and chance intertwine in art, in just the way that […] [others have] posited them in relation to natural phenomena.’Footnote 116 In his early 20s, Adler’s immediate source had been the prominent biologist and Darwinist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), snippets from whose evolutionary writings he copied out by hand in 1878.Footnote 117 Shortly thereafter, the opening statement of his doctoral dissertation made the key move, positing works explicitly as body forms or organisms whose growth is beholden to a law-governed teleology: ‘The development of tonality is organic. In a steady succession, one moment of development follows the other in order to bring the organism to perfection.’Footnote 118 The particulars of this analogy were severe and self-serving. Within the period of tonality itself, his model would attribute to musical works a specifically stylistic progression ‘in accordance with the laws of organic evolution’, from archaic to classical and finally mannerist growth [Manieristen] — categories that underscore the cultural power that anatomically derived laws wielded over art.

Back in 1814, Cuvier’s claim had carried the authority of the nascent discipline. An inductive approach, postulating general laws on the basis of specific corpora, was new for anatomy; it famously led Cuvier to hypothesize a genealogy of four body archetypes (embrachements), separable by their organization.Footnote 119 ‘Only organized bodies can enjoy life’, he explained, for each ‘has one proper form, not only in general and externally, but also in the detail of the structure of each of its parts’. From this it followed that ‘the form of a living body is more essential to it than its matter’, for matter is ceaselessly replaced.Footnote 120 The laws arising from a visual array of organized forms, from Cuvier’s ‘law of correlation’ (‘give me the bone, and I will describe the animal’) to the laws of function versus those of morphology, even formed the topic of a public debate with naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772–1844) at the French Academy of Sciences in 1830.Footnote 121 Paradoxically, the debate’s unclear outcome left ‘an extraordinary degree of unanimity on the issues brought forth’, for the episode solidified the belief that natural laws must govern the animal corpus and could be extrapolated from corpora.Footnote 122 The resulting two-step process in comparative anatomy was summarized by a leading textbook: ‘Empiricism is the first premise just as abstraction is the second.’Footnote 123 By the 1850s zoologists such as Karl Vogt would hold comparative anatomy to be nothing but a means of establishing laws.Footnote 124 Its primary goal, he explains, was to understand individual modifications according to their causes, and explicitly to ‘restore the original type from which the various forms that come before our eyes have developed’, exemplifying the belief among contemporary historians that to know the origin of something was to know its essence.Footnote 125

If (for Adler et al.) this foreshadows certain musical hierarchies of work over individual performance, underlying structure over surface texture, and genealogical status over aesthetics or gnostics, we should remember that unlike works, animal bodies were not primarily metaphysical. Hence their modes of visual representation in Peircean semiotics were categorically different, as icons (body depictions) as opposed to symbols (score notation). Accepting this, we might conclude that Adler extrapolated a genealogy of musical styles that pass before our ears, just as Cuvier’s and Vogt’s lawfully organized bodies pass ‘before our eyes’, and that this has provided an enduring licence for categorizing non-physical ontologies arising from the analysis of score notation. For a history of animal listening, the practice of grouping taxonomies by morphological kinship rather than by likeness of sentient function appeared unassailable. After all, the former was ocular and intuitively persuasive, the latter (how bodies experience the world) couldn’t be known with certainty; so the attempt to find common traits between ‘traces of [sentient] orders’, in Foucauldian terms, remains a story of false starts.Footnote 126

False Starts and Fish Ears

Indeed, historians of the nineteenth century are confronted by the persistent failure of knowledge about animal hearing to gain a secure foothold in the respectable work of anatomical dissection. ‘Who shall decide when doctors disagree?’ mused one popular account on auditory sense in lobsters from 1864; its author, William Houghton, raised a sceptical eyebrow at the French naturalist Alfred Moquin-Tandon (1804–63), who had argued optimistically that molluscs, too, were cognisant of sound, before adding that hearing in insects ‘has long been a disputed point’. His brisk survey of animal hearing closed by recommending an ironic ‘silent hymn of praise’ to the Creator of all things.Footnote 127

This is not to say the enterprise is a story of simple failure. Beyond popular readings and coffee-table anthologies such as Brehm’s Animal Life (1873), the question of insect hearing proved a lightning rod for speculation among professional anatomists.Footnote 128 As the Finnish anatomist Eric Bonsdorf (1810–98) acknowledged, the spectrum of opinion was wide. Many anatomists denied any sense of hearing to insects (among them Linnaeus, whom we met earlier); some pronounced it doubtful and unknown, while a fringe minority regarded it as a certainty.Footnote 129 A representative from this latter group is the Paris-based naturalist Hercule Strauss-Durckheim (1790–1865), who likened insect antennae to the strings of the aeolian harp, vibrating mechanically according to different aerial undulations; they perform the same function as the three bony ossicles in the human middle ear, he thought, yet the sheer diversity of forms, of which he catalogued twelve (Figure 2), left a daunting gulf between form and function that demanded we ‘admit numerous differences of functions’.Footnote 130 In similar vein, the Leipzig-based physician Ernst Weber argued that once the possibility of different functions is accepted, hearing in insects ‘can hardly be doubted’, for it allows for cross-modal mechanisms for auditory perception, e.g. receiving sound by wing movement and the body’s surface of ‘horned shields’.Footnote 131 It was amid equal clouds of uncertainty that the German physician Gottfried Treviranus (1776–1837) uttered what no musicologist wants to hear: ‘I have discovered the organ of hearing in the common cockroach’ (Figure 3).Footnote 132 But again, the ultimate purpose of the semicircular membrane he uncovered, with its neural extensions connecting brain to antennae, remained guesswork: ‘The similarity […] with an ear drum […] seems so conspicuous to me that anyone who sees this part must immediately suppose it to be the ear of a cockroach.’Footnote 133 Amid such imaginative play, Bonsdorf soberly put his finger on the methodological challenge of attributing auditory response to animals in the shadow of human aurality:

When these authors […] admit the perception of sounds, and yet deny the organ of hearing, they appear to me to stand in the same predicament as if they had said that insects indeed hear, but yet they do not hear truly; than which nothing could be conceived or expressed more absurd.Footnote 134

Figure 2. Hercule Strauss-Durkheim’s illustration of twelve insect antennae; ‘On the Antennae and the Hearing of Insects’, The Field Naturalist, 1 (1833), p. 61.

Figure 3. Gottfried Treviranus’s illustration of ‘the alleged organ of hearing’ [‘die muthmasslichen Gehörorgane’] in the common cockroach. This membrane-covered hole is given as hh, where oo = the eyes, ff = the lowest limbs of the cut-off antennae, gg = pits in which the antennae sit. Treviranus, ‘Resultate einiger Untersuchungen über den inner Bau der Insekten’, Annalen der Wetterauischen Gesellschaft für die gesammte Naturkunde, 2 (1809), pp. 169–73.

In the aural imagination, if hearing without ears was not ‘true’, what it was remained uncertain. To imagine what cannot be heard not only contradicted the central tenet of sensationalism, it invited potentially limitless supposition. So for Bonsdorf, whether antennae might perform the same function as ears was a ‘very difficult question’, prompting him to stretch credulity by likening their form and hollow structure to semicircular canals, which — his assembled sources led him to believe — most likely correspond to ‘the seat of hearing, or receptacle of the impression of sounds’.Footnote 135 In short, beyond myriad erroneous conclusions, the attribution of partial hearing to ‘lower’ organisms originated in a pervasive uncertainty of form and function, coupled to beliefs over biological hierarchy. As such it functions as a metonym for broader assumptions about ‘untrue’ hearing at the time among animality in toto.

A representative case is the popular question of whether or not fish could hear. As with insects, this prompted a range of speculative articles and pamphlets as well as correspondence and commentary, from the Transactions of the Royal Society in London to Weber’s Latin tract On the Ears and Hearing of Man and Animals (1820), part 1 of which concerned the aural system in fish (De aure animalium aquatilium).Footnote 136 At stake was whether hearing could be proven to exist without external organs and how experiments concerning behaviour might plausibly show this. At root, however, the underlying question was subtly different: just how low did the auditory Chain of Being go?

As early as 1650, the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher had wondered if fish were an endpoint, deaf and mute. In his Musurgia universalis, he compared the anatomical shapes and functions of ear parts across mammals. His cutaway presentation of ‘the aural organs of various animals’, reproduced in Figure 4, is indicative of the intuitive assumption that hearing required visible organs for channelling vibrations, not least external pinnae. Fish had none, so were immediately problematic. ‘It is doubtful whether fish have ears’, he remarked; the holes below the eyes could be designed for hearing or smelling, he suggested: ‘nobody has adequately investigated’ — an indicative judgement that would be parroted until Weber’s treatise in 1820. Kircher surmised incorrectly that the density of water slows down sonic vibrations for aquatic creatures such as whales or seals, causing hearing ‘in a muffled way […] they have not a refined organ of hearing like terrestrial creatures’.Footnote 137 His words were still quoted in the 1760s, with popular summaries appearing as late as the 1870s,Footnote 138 by which time a litany of experiments — ranging from comical to fiercely detailed — had primed the debate.

Figure 4. Athanasius Kircher’s illustration of the anatomy of different animal ears. Box from left to right: human, cow, horse, dog, followed by leopard, cat, above rat, pig, then sheep and goose. Folio 14 in Musurgia universalis, 2 vols (1650), i, p. 12.

The English naturalist William Arderon (1703–67), for example, after placing various fish in glass jars and observing no reaction from his aquatic subjects to ‘whistling, howling, and the sounds of several musical instruments’ nearby, explains that he flicked the glass with his thumbnail, and, receiving little reaction, reported to the Royal Society in 1748 that in the ‘highest probability, [fish] are really destitute of that Sense’.Footnote 139 Decades later, John Hunter concluded contrariwise that ‘it is evident fish possess the organ of hearing’, after he observed ‘three curved tubes […] semi-circular canals’ in tiny cavities made of cartilage that project laterally from the sides of salmon and cod skulls. His empirical proof was thin, however,Footnote 140 and he would be corrected by Weber, whose dissections revealed in 1820 that lampreys (Petromyzon) are in fact destitute of semicircular canals, and their auditory nerves ‘do not belong to the ear’.Footnote 141 Weber concludes his study with twenty-seven ‘new observations’ about the aural anatomy of fish, revealing an astonishing range of empirical minutiae that counted as pioneering knowledge of anatomy, if not of aquatic auralities.Footnote 142 Three sample observations are:

-

• The ray’s ear has not one but two external passages for receiving sound (the windows of the vestibulum membranaceum and the vestibulum cartilaginieum, which he likens to the oval and round windows, respectively, in humans).Footnote 143

-

• The ossicles in carp convey vibrations directly to the cranium, via two auditory ‘holes’ (fossae) through which an oily fluid transmits vibration from the auditory canal to the cranium cavity via two occipital bones.Footnote 144 (See Figure 5a.)

-

• In herrings, the right and left membranous vestibules of the inner ear actively ‘communicate […] by means of a transverse membranous canal’ below the brain, where mercury injected in one side ends up in the other, suggesting a materially shared aural effect between ‘ears’.Footnote 145 (See Figure 5b.)

Figure 5a. Ernst Weber’s illustrations of unusual aural mechanisms in carp. Nos. 3–5 show the incus, malleus, and stapes (ossicles) in the common carp, connecting directly to the cranial cavity via an oily fluid; no. 7 shows the occipital foramen ‘through which the membranous auditory fossa has free communication with the cranial cavity’ [‘per quod fossa auditoria membranacea liberum cum cranii cavo commercium habet’]. It implies a role for bone vibration in auditory perception. Weber, De aure et auditu hominis et animalium (Fleischerum, 1820), Figure 10 and ‘Explicatio tabularum’, pp. 7–8.

Readers encountering such thickets of anatomical detail were offered no matching postulates about the auditory perception resulting from these forms, e.g. that carp skulls might vibrate in the perception of sound, or that a materially shared effect might link both sides of a herring’s inner ears. Instead, the explanatory strategy is anthropomorphic. In the absence of a mammalian cochlea, i.e. a dedicated auditory organ, a majority of fish possess three tiny bones on each side of their skull, which may be compared — we learn — to the stapes, incus, and malleus in humans, just as the two cavities (atria), that are in turn shut by the movement of the stapes, may be compared to the oval window in humans.Footnote 146 Comprehending anatomical form and function by comparison to human bodies was a familiar strategy, as a form of analogy.Footnote 147 Yet in bridging human–animal forms by reference to the former, it also reflects a necessarily human-centric mode of thought (cf. Lange’s teleology), and it is perhaps no coincidence that Weber’s major treatises on the sensation of touch, De tactu (1834) and Der Tastsinn und das Gefühl (1846), would concern humans alone, arising in large part from empirical work on his own body.Footnote 148

Figure 5b. Ernst Weber’s illustrations of unusual aural mechanisms in herring. No. 2 shows the membranous canal connecting the two membranous vestibules of the inner ear in herrings. This implies a direct material link between left and right auditory perception. Weber, De aure et auditu hominis et animalium (Fleischerum, 1820), Figure 66 and ‘Explicatio tabularum’, pp. 21–22.

Separately, the more testable question of how efficiently water could transmit sounds sheds light on a certain naivety within contemporary empiricism. Arderon, for his part, devised two experiments: words spoken on the river bank were clearly audible by a swimmer submerged two feet, he reports; a gunshot was audible twelve feet underwater. The lunacy of inverting this test — by first ringing a submerged bell, then throwing ‘a kind of Hand-Granado’ underwater to see if sound made below the surface was audible above — is indicative of the brute curiosity characterizing such gentlemen naturalists. But it also marks the frustrations of method in such an intractable quest. Among his many letters to the Royal Society, Arderon dutifully reported both the ‘prodigious hollow Sound’ of the underwater grenade and the softly ringing bell.Footnote 149 It was received politely at the Society, without further comment.

The later application of different aural experiences to animal anatomies that arise from a watery medium represents a first strike at the assumption that human aurality was sovereign. Speculation crystallized around how effectively sound was communicated for fish and amphibians versus mammals and birds. In one case, the Scottish anatomist Alexander Monro (1733–1817) had written of how ‘the tremor of the chain of small bones will be much less interrupted by air than it would have been by a watery liquor filling the cavity of the timpanum’, meaning that for amphibious creatures ‘two different impressions are made on the membrane of the oval hole’: one above the water (resulting in stronger sound impressions) and one below. Published in 1785, his views built on Aristotle’s ‘two classes’ of aquatic animals, i.e. those that exist entirely within water, and those that breathe air. They were conjectural but acquired nuance through experimentation.Footnote 150 After failing to hear a ticking watch he placed between his tongue and the roof of his mouth, he determined that the purpose of the Eustachian tube must be to furnish air to the tympanic cavity rather than to receive impressions, and he differentiated the split auditory world of genuine amphibians from that of whales, who appear amphibious but whose physiological need for breath ensured their ears were primarily ‘calculated to receive sound from the air by an external meatus’.Footnote 151 If Monro’s speculations were guided by physical form and the facts of anatomical knowledge, others, such as the French surgeon Claude-Nicolas Le Cat in his Physical Essay on the Senses (1750), were less constrained: the absence of a cochlea meant no sensibility for harmony, rendering all cochlea-less animals ‘as stupid as Fish’, while the unusually keen hearing of birds, he proposed, simply resulted from their heads’ lack of ‘complicated muscles’, leaving them ‘almost entirely sonorous like a Bell. Hence must they necessarily be agitated by the sounds which present them.’Footnote 152 His anticipation of the same logic that would inform Strauss-Durckheim’s aeolian antennae underscores the slippage between imagination and biological theory that hindered any serious attempts to ‘hear into’ another organism’s environment, even while it remains the case that disputes over animal abilities more typically centred on ‘problems of brute instinct and intelligence’ rather than on anything approaching aesthetic judgement.Footnote 153

To be sure, the same slippage is mirrored in certain pronouncements about human hearing, as guided by a latent music-theoretical imagination. In 1826, the leading young physiologist in Germany, Johannes Müller, decried the ‘many useless hypotheses about the function of the [ear’s] individual parts’, noting there was not ‘a multitude of strings’ to discover in the eardrum, varying their lengths according to the drum’s dimensions (cf. Justinius Andreas Kerner), nor were the semicircular canals formed in the proportions of a single triad, the octave, the third, and the fifth (cf. Andreae Comparetti): ‘We do not see in the cochlea a musical instrument,’ he asserts firmly, ‘but only a very perfect apparatus for exposing all individual parts of the nerve to tremors.’Footnote 154 To study this more objective ‘perfection’, he proposed a process of deduction based on the size of the auditory nerve and the laws of sound conduction. But for leading acousticians such as Ernst Chladni, even theories of mechanical propagation fell short. His summary of recent literature on animal ears, in the final chapter of his Treatise on Acoustics (both 1802 and 1809 editions), could only follow Cuvier’s lead in ignoring the ‘mystery impenetrable to our intellect’. Commentaries on hearing in everything from cuttlefish to insects, salamanders to birds, are dutifully referenced, but their peripheral status was obvious. The pithy summary that closes the final short chapter on animal hearing was conceived less for rhetorical weight than for eyebrow-raising curiosity: ‘The organs required for hearing are found, therefore, in all animals examined up until now, but some auxiliary organs, designed to hear more perfectly, are located only in some classes of animals.’Footnote 155 The nature or telos of this perfection, and its distribution between classes, remained an open question. Chladni’s chapter amounts to tokenism, where brevity reflected a sense that serious experimentalists ought to engage the claims of eighteenth-century naturalists about animal sentience, but that these were so fraught with methodological uncertainty that harmless synopsis offered the lesser evil.

Feuerbach’s Animals

What had really induced me to attach so much importance to Feuerbach was his conclusion that the only reality was that which the senses perceived.

Richard WagnerFootnote 156

Not so for Feuerbach, who took up the question of animal sentience directly. He studied Cuvier’s writings on animals while completing his doctorate in natural sciences at the University of Erlangen (1827–28) and duly cited the Frenchman in the opening sentences of The Essence of Christianity (1841) regarding the limits of animal consciousness.Footnote 157 But while for him animal senses were limited, physiological ‘man’ took on some attributes of a Catholic God as ‘the infinite being, the being without any limitations’.Footnote 158 How could this limitlessness align with the empirical limits of human aural perception — especially when it contrasts with the putatively ‘untrue’ hearing of animals, despite humans and animals having ‘senses in common’?Footnote 159 How, in other words, did Feuerbach distinguish animal sentience from human ‘universal’ sentience?