In November 1922, Adolf Hitler addressed a large crowd at the Kindl-Keller beer hall in Munich. In the crowd was Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl, who would become an important supporter, financier, and gateway into Munich’s upper classes. When he first laid eyes on Hitler, he was unimpressed, noting that Hitler looked “like a waiter in a railway-station restaurant.” But Hitler electrified the room, hitting his routine talking points: the November Revolution, the Treaty of Versailles, the dangers of Marxism and pacifism, Jewish profiteers, and the promises of anti-republicanism seen in Benito Mussolini’s March on Rome. In Putzi’s estimation the room was populated almost exclusively by men, mostly lower middle class young men and former soldiers. He further claimed that the hustle and bustle of the large space—which could hold at least three thousand people—followed Hitler’s lead. When he spoke, “the hubbub and mug-clattering had stopped, and they were drinking in every word.” During a pause, Hitler took a long drink of beer, which “supplied the finishing touch, the local, personal note, acting as a further impetus to the enthusiasm of the malt-minded Munichers.” Hitler then handed the mug to his bodyguard Ulrich Graf who, Putzi noted, clearly had a revolver in his pocket. Footnote 1

This scene draws attention to the dynamic of the space, the ambiance, the local meanings, and the persistent threat of violence. What follows considers the spaces in which the early Nazi movement emerged, grounding the mass mobilization and violence of the movement in the specific contexts of postwar Munich and its iconic beer halls. Such a tight focus on local violence remains uncommon in early Weimar scholarship even two decades after Benjamin Ziemann called for “detailed studies of the logic of action in local and regional case studies.”Footnote 2 His own study of rural Bavaria and Dirk Schumann’s influential analysis of Saxony did much in this direction, but in most other locales, notably Berlin, robust scholarship has primarily focused on the later years of the Republic and clashes with communists.Footnote 3 Neither the temporal scope nor the thematic lessons of such scholarship proves entirely applicable to Munich. For one, despite its Council Republic past, Munich was not a communist city—even in the depths of hyperinflation and the Ruhr Crisis.Footnote 4 Instead, in the wake of the Council Republic, Munich emerged as a hub of the variegated right, home to monarchists, radicals, and antisemites. The prominent place of a diverse community of Jews in the Revolutions of 1918/1919, supplied “ammunition” for a rapidly expanding antisemitism, and counterrevolutionaries in Germany and across Central Europe flocked to the city.Footnote 5 That Munich could become such a hub of the right was aided by the fact that it was the only place in Germany where the Kapp Putsch had any lasting effect: the ousting of social democratic Minister President Johannes Hoffmann, which paved the way for the monarchist, antisemitic, and anti-communist leadership of Gustav von Kahr and his Chief of Police Ernst Pöhner.Footnote 6

This turn to the antisemitic and counterrevolutionary right in Munich was part of a broader redefinition of society and politics. As Martin Geyer argues, wartime and postwar Munich went topsy-turvy under the combined pressures of inflation and a cacophony of crisis discourses that facilitated a renegotiation of the politically possible.Footnote 7 Our focus here on the early Nazi movement in and around the city’s beer halls confirms the significance of local conditions in Munich—myriad right-wing forces, the legacy of the revolutions, and the increasingly ubiquitous antisemitism—while also drawing renewed attention to hostility against social democracy and the parliamentary republic at large.Footnote 8 In Munich’s beer halls, and in the violence that spilled out of them, the national and local pillars of the Republic itself were among the most frequent targets: the “November Criminals” who had paved the way, the Social Democratic Party (SPD), its Bavarian chairman Erhard Auer, and its newspaper the Münchener Post. The threat of another Communist, or allegedly “Judeo-Bolshevik” revolution of course remained central to Nazi rhetoric, but Munich was not a communist city, and the early Nazi movement just as vehemently—perhaps more so—harped on the persistent shame of the present.

Focusing on events in and around beer halls in the years prior to the Hitler Putsch, this article makes interlocking arguments about spatial practices, political violence, and mass mobilization in the early Nazi movement. First, beer halls played a crucial role for the mass political and populist aspirations of the Nazi Party or NSDAP.Footnote 9 At a practical level, they functioned as early party headquarters, they facilitated mass mobilization, and, in their raison d’être, they served copious quantities of alcohol, which lowered inhibitions and fostered both sociability and violence. But, as we will see, Munich’s beer halls had long been relatively inclusive places—among the most welcoming for all classes, women, and Jews, for example—and long part of Munich’s civil society. Spatially, then, the early Nazi movement worked to recode the function of the space, to build a mass movement in part by making the beer halls part of an exclusionary, uncivil society.Footnote 10

Second, that goal encouraged the pursuit of control and therefore, in seeking to recode Munich’s beer halls, the Nazi movement relied on violence that both benefitted from and further undermined the gaps in state authority. What became the SA originated in these contested spaces: fighting and removing political and ideological opponents within the beer halls on the one hand and contesting streets and disrupting the meetings of political rivals on the other. The SA was not unique as a paramilitary but somewhat more so in its fusion of paramilitary and political party, making it the first of the party Kampfbünde that became the hallmark of Weimar political violence after 1923.Footnote 11 This imbrication of party and paramilitary emerged in part from the conditions of Munich’s beer halls, where ideological aims, aspirations of spatial authority, and mass mobilization melded together and grew into the gaps left open by the Bavarian and Munich governments. In these years, as Chief of Police Pöhner subsequently acknowledged, the Munich police “held [their] protecting hands over the National Socialist Party and Herr Hitler” in hopes of undermining the political left.Footnote 12 Bavarian SPD Chairman Erhard Auer repeatedly failed—in the press, in speeches, and in the Landtag—in prodding the state to exert its monopoly of violence.Footnote 13 When the state and the police chose to act, or more often not act, they participated in defining the permissible boundaries of the evolving spatial politics of the Nazi movement.Footnote 14

Finally, in the years prior to the Beer Hall Putsch, the fusing of spatial violence and party politics was the result of a learning process. At a practical level the movement drew lessons and refined battle tactics. It furthermore learned to wield violence for mass political aims and got its first taste of contesting and transforming space. Beyond refining practices and ideologies, the movement was also beginning to define what the Volk looked like, who was included, and what measures might protect it. The mass mobilizing and violent nature of the movement in general and its antisemitic and anti-republican components in particular emerged not only from the convictions that leaders or attendees brought into the beer halls, but from lessons learned in and around them: hold ground, restrict access, limit discourse, move as a unit. Taken together, we see in Munich’s beer halls a melding of the postwar condition, the desire to form a mass movement and Volkspartei, and the definition of both that “Volk” and an embodied Other, not as a rhetorical symbol but as human opponents to keep out of the room, off the streets, and out of the nation.

This article is broken into three sections. The first analyzes the culture and space of Munich’s beer halls up to the early 1920s, to establish how they became so contested and belligerent. The second then shifts toward how the Nazi movement transformed the beer halls through both rhetorical and physical violence, and by building a broad mass movement with a youthful, hyper-masculine bent. Finally, the third section reveals how the violent culture of the beer hall expanded beyond it by way of the SA, while the beer halls themselves remained central to the aspiration of mass mobilization. Munich’s beer halls had long been important social institutions, but in the early 1920s they became mass political and militarized spaces where ideology, violence, and spatial practice took on increasingly radical dynamics.

The Culture and Space of the Beer Hall

Munich’s beer halls were one among many sorts of contested spaces where social and political life transformed in the years following the Great War. As Dirk Schumann has shown in Saxony, the contestation of public and semipublic spaces was “the by-product of a new style of politics that sought the control of public space in order to pave the way for and sustain the control of parliaments and governments.”Footnote 15 In Italy too, in the same years studied here, Fascists, socialists, communists, and anarchists fought for control of everyday spaces, with bars in particular becoming “important spaces in which political power was contested between fascists and anti-fascists.”Footnote 16 Once in power, both the Fascists and the Nazis continued to seek control as bars remained crucial spaces of public life, political authority, and potential subversion.Footnote 17 Setting the foundation for how the early Nazi movement operated in and around Munich’s beer halls, this section takes a granular look at the spaces themselves, their materiality, their traditions, and how they transformed in the immediate postwar years. Beginning in the nineteenth century, spaces of alcohol consumption became crucial to social and political life in Germany. In the Imperial period, pubs and taverns became the core of political life, facilitating social ties and civic exchange—a topic particularly well explored in the case of northern working-class bars and the SPD.Footnote 18 Such work tends to say little about Munich, where spaces were often significantly bigger and discourse more varied. The particulars of the spaces and their traditions provide important foundations for their later use as sites of mass mobilization and political radicalism.

In the nineteenth century, Munich’s beer halls were perhaps the most inclusive spaces in the city. Early images reveal men, women, children, and dogs scattered around adjacent beer gardens and patrons included dignitaries, intellectuals, farmers, craftsmen, servants, workers, and soldiers alike.Footnote 19 Women were clearly outnumbered by men but their presence remains notable. Munich’s Jewish community likewise frequented beer halls and beer gardens apparently “tailor-made for Orthodox Jews” who “could bring their own kosher food” and “drink beer that conformed to the Jewish dietary laws.”Footnote 20 The Orthodox Feuchtwanger family had a reserved regular’s table which they visited every Saturday after synagogue.Footnote 21 The Hofbräuhaus in particular sold the cheapest beer in the city by royal decree, making it attractive to many in the lower classes. One turn of the century commentator—surely overstating his case—even claimed that at the Hofbräuhaus, “all class differences disappeared.”Footnote 22 We should be wary of rosy hindsight and the postwar tendency to remember a prewar tranquility, but these were relatively inclusive spaces, part of a democratizing, though not fully democratic, Imperial Germany.Footnote 23

The physicality of the spaces was crucial to both their pre- and postwar dynamics. In contrast to typical northern German working-class taverns that sat ten to twenty people, the main festival halls could usually sit over two thousand and large informal seating areas encouraged a sort of social mixing uncommon in neighborhood taverns. The Berlin transplant and later Nobel prize winner Paul von Heyse praised the leveling experience writing that “here one finds on fraternal benches… great and small in familiar mix.”Footnote 24 Such social mixing was given a boost when the scale of the spaces increased. At least twenty large beer halls were built or renovated between 1880 and the First World War. The form was in the “New Bavarian Renaissance” style which featured ornate exteriors, large vaulted main rooms, and smaller, cozier side rooms.Footnote 25 Such Munich-style Bierpaläste also cropped up around Germany beginning in the 1880s, but by the Weimar period, most of them outside Munich had closed, at least temporarily.Footnote 26

If the cavernous size and “fraternal benches” had encouraged a sort of open sociability, the materiality of the space could also fuel intense violence. Restaurants and bars generally are stocked with potential weapons: sharp cutlery, kitchen knives, heavy pots and pans, and ashtrays and plates which can be used as long-range projectiles. And indeed in later years the Munich Police would seek to control the “liberal supply of missiles at hand” and attempt to “disarm” combatants by forbidding the sale of food and drink and even the distribution of ashtrays because, “experience has proved that these can be used as missiles of an offensive and even dangerous character.”Footnote 27 Perhaps the single most dangerous and effective weapon was integral to the space of the beer hall: the heavy beer mug or stoneware stein, which can easily deliver life-threatening injuries. At almost one and a half kilos (more than three pounds) when empty, a one-liter Maßkrug is a formidable object. A recent medical study found that being struck with one can result in traumatic brain injury, intracerebral bleeding, skull fracture, and death. If the vessel shatters, shards can be and often are used as stabbing weapons. The study detailed several recent cases including one in which glass shards lodged into an young man’s ocular cavity, prolapsing his iris, and leaking his intraocular fluid.Footnote 28 In Munich’s beer halls, this dangerous drinking vessel is stored by the hundreds if not the thousands.

How the spaces became so violent requires, at the least, a consideration of how broader contexts transformed what people brought into and hoped for from the spaces. As Edward Soja has argued, the physical reality of a built space always exists in a trialectic with different sorts of convictions about them and the meanings and experiences of them.Footnote 29 The Nazis were not the first or the only group to use beer halls for mass political purposes. Beginning with the wave of renovations around the turn of the century, Munich’s beer halls became increasingly important as the new large spaces and adjoining rooms were rented out for celebrations and political events, thereby becoming “the center of political life” throughout the twentieth century.Footnote 30 In the context of the immediate postwar period, however, the beer halls took on particular significance as political spaces in part because the consolidating state failed to establish its monopoly of violence and the peaceful operation of the institutions of governance. Just four days after the assassination of Kurt Eisner, soldiers and workers assembled in Munich’s beer halls to demand a soviet republic.Footnote 31 And indeed, in the crucial moment of April 1919, the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils seized control of a government meeting at the Mathäserbräu and proclaimed their communist Republic of Councils. What came next—brief soviet revolution and violent counterrevolution—was pivotal in the trajectory of Munich politics, galvanizing bourgeois Münchner against the communist left and radicalizing the ultranationalist and antisemitic right.Footnote 32

Far from an isolated incident, the beer halls remained sites of radical mass politics and violence, a place where new political forms could grow in the gaps left open by the state, whether those be crises of political legitimacy or the “protecting hands” and blind eye of the police. The NSDAP (and its predecessor, the DAP) met in Munich’s beer halls. The fledgling party had neither a headquarters (until the end of 1921) nor historic sites of organizing akin to socialist-oriented labor union buildings. In the pursuit of a mass movement, Party meetings moved from the side rooms to the main halls where Hitler and the leadership could call on “the people” as liters of beer helped foster cross-class sociability, lowered inhibitions, and, as we will see, cultures of violence. But they would also be contested. Less than a year after the Councils seized control of the Mathäserbräu, over two thousand people packed into the Festsaal of the Hofbräuhaus for the first mass event hosted by the NSDAP. As Hitler took the floor, some in the audience heckled and threw beer steins. Hitler dodged the heavy projectiles as Nazi supporters returned fire, throwing their own steins and wielding truncheons and whips to establish control of the room.Footnote 33 Once they had dispatched the hecklers, Hitler announced the radical vision of the party in its newly crafted program, the Twenty-Five Points. The conflict preceding this announcement, taken in sequence with the establishment of the Council Republic in the Mathäserbräu reveals a layered contestation, first for the specific spaces, and second for the fate of the city, the state, and the country.

In the Nazi Beer Halls

The Nazi movement was never able to conquer or capture the beer halls in any permanent sense. In this way they were distinct from the later institution of the Sturmlokal which was more of a base or “fortified position in the battle zone.”Footnote 34 In the beer halls, the Nazi movement would seek control for a night, usually once or twice a week, but their use of the venues made ideological convictions spatial and transformed practices. While beer halls long had a political function, they became central to a movement that sought both a particular kind of community and a war against those they deemed to be at fault for their national misery. This section analyzes verbal and physical violence and—as far as possible—the composition of the crowd in order to reveal how the early Nazi movement recoded the beer halls. Radical rhetoric not only catered to broad discontent, but also took form in space as the NSDAP began to define what their mass movement ought to look like. The words of leaders and the composition of the movement reveal the emerging double-edge of exclusion and inclusion that would later define the Nazi regime. Beer hall events fostered an exclusionary culture, especially in relation to Jews, which became violent thanks to the tolerance of the police. At the same time, the party attempted to foster a masculine mass movement marked by male bonding and the camaraderie of drinking, singing, and physical exercise. Determined to undo alleged injustices to the nation, the early Nazi movement began to define its sense of community within the space of the beer hall.

Munich’s beer halls were the first spaces in Germany to echo with Nazi vitriol. The demonization and rhetorical othering of Jews was immediate, but the emergence of practices and cultures of excluding real, embodied people emerged over the course of a few months. When the party announced the Twenty-Five Points in their first ever mass meeting in February 1920, Jews were explicitly excluded from their conception of the German nation, but this was hardly revolutionary given that in Munich alone there were already fifteen different antisemitic völkisch groups.Footnote 35 But the “Jewish Question” remained a frequent talking point, often framed as the glue that bound a range of contradictory claims. For instance, in June, attendees in the Bürgerbräukeller were told it was the Jews who had both reduced the German people to helots via their control of finance capital and manipulated the workers through their control of unions and leftist movements.Footnote 36 Commentary about Jews in particular promoted violence quite quickly and was structured into the participatory elements of mass meetings. For instance, on May 27 and May 31, 1920, Anton Drexler and Hitler respectively led crowds in the Hofbräuhaus and Bürgerbräukeller in a call and response routine about what was to be done with the Jews. Apparently choreographed, both crowds called out: “String them up! Slaughter them!”Footnote 37 In the same room a few months later, likely to many of the same people, Hitler addressed a crowd over two thousand strong, explaining why the party was antisemitic, and he so enlivened the crowd that he was interrupted by cheers fifty-eight times.Footnote 38 In his standard two-hour speech format, this would mean a cheering interruption about every two minutes. He hit common tropes of contemporary antisemitism, but also clarified that the goal of the party was not parliamentary but populist and centered in the beer hall: “We don’t want to go to parliament but rather to climb onto the beer table and work restlessly, to go out and call on the people so that the truth [of the Jewish threat] wins.” The party aimed to resurrect “the moral strength of the Volk” through nothing other than the “removal of the Jews.” This specific juxtaposition mirrors the rhetoric of exclusion found in the Twenty-Five Points, but Hitler also added a more pointed, personal claim, declaring that “if a Jew gets in my way, I will eliminate him.”Footnote 39

As a generation of scholarship has established, radical language does not readily translate into radical action, but words do matter and soon began to influence violent deeds. At the end of September 1920, words and deeds came together in the recoding of space. Once again in the large Festsaal of the Hofbräuhaus, the party hosted an event denouncing the Talmud as the alleged source of “Jewish hatred and contempt for humanity.” In attendance was Munich Rabbi Dr. Leo Baerwald and members of the Reich Federation of Jewish Frontline Soldiers including Hermann Klugmann, who came to confront antisemitic hatred. Whatever civility the space used to offer was now absent. They found themselves in a hostile crowd of some fifteen hundred, scrutinized with “dark, probing looks” and suffering verbal abuses until Baerwald moved toward the front of the room to speak. His move to contest the Nazi codification of space was limited, as he was introduced to the roaring crowd by Ottmar Rutz as the “Rassejude Baerwald” and forced to answer only yes-or-no questions. Things became violent when he denied that the Talmud instructed Jews to violate non-Jewish women. In an uproar, Klugmann remembered, “a mob rushed at us, beating us wildly” and the group fled the room and “never again attempted to intervene in the discussion of a national socialist meeting.”Footnote 40 Outside, on Müntzstrasse, policemen stood watch but chose not to intervene, “so as to not increase the excitement of the fanatical masses.”Footnote 41 For Munich’s Jewish community, this event was indicative of an “emboldened antisemitism” emerging in the city which left many with “rather little hope for improvement.”Footnote 42 The Nazi movement also got bolder, framing the composition of the space in racial terms. In the same room, two months later, Hitler made the somewhat remarkable claim that, “I would rather have a hundred Blacks (Neger) in the room than one Jew.” The Jews were unwelcome in the room and in the country, he claimed, noting that it was the “oriental rabble”—a common epithet for Jews—who support the Treaty of Versailles and who “must be the first to be removed from the Volk.”Footnote 43 Both comments, which met wild applause, depended on a parallel construction that emphasized the removal of Jews in the name of ideological and political claims to space—over both the beer hall and the nation. By this point, not only did promotional materials explicitly prohibit the attendance of Jews, but members of Munich’s Jewish community had been forcibly removed.Footnote 44

The expulsion of Baerwald and his group on September 30, 1920 came just weeks after the first report that the Nazi Party was taking measures to police their own events. While there is some debate as to the precise origins of the SA proper, the organization of party toughs took shape as part of recoding public space, both ensuring control at Nazi events and disrupting speakers at rival political gatherings.Footnote 45 In early September, Munich police inspector Karl Angstl reported having encountered enforcers, or “Ordnungsleute,” equipped with swastika armbands at a three-thousand-person event in the Kindl-Keller—at the time the largest beer hall in the city. He described how their deployment throughout the space would effectively deter any opponents with intentions to violently dissolve (Sprengungabsichten) the event. On the strength of the enforcers, he decided that “the organization is able to restore peace and order in the hall without the assistance of the police,” and he was apparently undisturbed by the implied violence by which they could control the space and “restore peace and order.” To Angstl, it seemed obvious that the Nazis had already won the space and that the role of the police was only to contain violence from exploding outward from the beer halls and onto the streets. What happened within them, apparently, was not their concern. His recommendation for containment—posting patrols tasked with protecting those ejected from future meetings from further attacks—seems to have been in effect when Baerwald and his group were pushed out of the Hofbräuhaus.Footnote 46

The space left open for the coexistence of both a party paramilitary and state forces henceforth became foundational for the violent dynamics of the early Nazi movement. The Baerwald group was not alone in its ejection. A month and a half later, a group of men from the Republican Protection League, a small paramilitary led by Hermann Schützinger, entered the Hofbräuhaus intent on disrupting yet another tirade against the Talmud by Ludwig Ruez. The meeting was hosted by the similarly named German National Socialist Workers’ Party (DNSAP), with origins in Bohemian pan-Germanism, but the room was full thanks to the many Nazis in attendance, including Hitler, who spoke at least twice. When someone in the “overfilled” Festsaal recognized Schützinger and his men, the room descended into a full-blown brawl. Newspapers reported that at least one enforcer had been badly bloodied by a beer stein to the face.Footnote 47 Schützinger’s group was initially targeted as a pro-Republican paramilitary, but their removal also testifies to the explanatory power already invested in the figure of the Jewish menace. According to the master of the watch, officer Georg Mauerer, as the men were removed, Nazi supporters shouted, “beat the dogs down—they’re paid for by the Jews.” Mauerer reported having heard this from outside the building because, once again, the police did not intervene in what he later called a “major brawl.” Instead, he and other members of the police waited outside, tolerating violence and acting only when Schützinger and four of his men were “violently brought out,” at which point he and the assembled protection force “freed the men from the crowd.”Footnote 48

What exactly the dynamics of these early events looked like is hard to tell. Turning to party membership statistics allows for some basic and cautious inferences if we assume that those who joined the party stand in rough proportion to those who attended events—the major exception being those who attended to disrupt. Workers were always underrepresented and the lower middle and middle classes overrepresented. But statistical analysis of membership might also suggest that class was the least important social indicator, when read against region, age, and gender, and especially when read against the fact that basically no other party enjoyed a more class-diverse base.Footnote 49 Beyond membership, in Klugmann’s account from September 1920, he notes that the Hofbräuhaus was “packed with people from all social classes: party members in uniform or wearing insignia, men and women of all ages, and Catholic clergy, recognizable by their clothing.”Footnote 50 On the gender front, and somewhat anecdotally, another 1920 report noted that about a quarter of attendees were women, which is notably higher than party memberships would suggest.Footnote 51 Still, the movement most directly appealed to men. It sought attendance by veterans by waiving their admission prices and incorporating military symbols and music.Footnote 52 The movement also appealed to young men that were too young to have served in the war.Footnote 53 This was explicitly the goal for the SA, which was limited to young men between seventeen and twenty-three. For the young men who joined the SA, most “believed that they were being called to take up where their fathers had left off in 1918,” and fought with dogged determination against perceived national humiliations.Footnote 54 This in part explains the quick turn to violence by Saalschutz forces tasked with keeping order in the beer halls.

While it proves difficult to definitively pin down the specific dynamic of any given space, especially as crowds get larger, the environment of early Nazi events was clearly that of an evening drinking bout. The socially elite Hermann Göring dismissed many of Hitler’s early followers as a “bunch of beer-swillers… with a limited, provincial horizon.”Footnote 55 But for an organization seeking to generate a mass movement, what better place to meet the disgruntled people where they are? Furthermore, a night of drinking may have been conducive to joining the movement. Reflecting on the years before the Beer Hall Putsch while in prison, Hitler declared that “in the morning and even during the day people’s will power seems to struggle with the greatest energy against an attempt to force upon them a strange will and a strange opinion. At night, however, they succumb more easily to the dominating force of a stronger will.”Footnote 56 Beyond a sort of ideological imposition, such spaces were particularly well suited to the masculinist culture of the movement. Spaces of public drinking had long been “part of the masculine cultural sphere,” even in the more progressive socialist movement.Footnote 57 For the Nazis, however, the beer halls catered to what ideologue Alfred Rosenberg called the “highest manifestation of masculinity”—the ability to consume the most beer.Footnote 58 In such “male dominated” spaces, as historian Edward Westermann has recently noted, the “ability to hold one’s alcohol and the willingness to fight emerged as the hallmarks of male virtue” in the postwar milieu.Footnote 59

The physical violence SA men used in attempting to assert control of beer hall events reached a relative climax in the so-called “Battle of the Hofbräuhaus” in November 1921. The event and its aftermath reveal not just the importance of seeking control, but also the ways in which the Nazi movement learned from and evolved out of such violent moments. On the 4th of the month, social democrats and other leftists attended and attempted to disrupt a Nazi event in the Hofbräuhaus. In Mein Kampf, Hitler recalled getting word of their intentions too late and fewer than fifty SA men faced several hundred proletarian opponents. Standing on a table for his speech, as he so often did in the Hofbräuhaus, Hitler remembered seeing his “enemies… ordering beer after beer and putting the empty mugs under the table” thereby accumulating whole “batteries” of projectiles as well as a substantial buzz. When the conflict broke out, “the whole hall was filled with a roaring, screaming crowd, over which, like howitzer shells, flew innumerable beer mugs.”Footnote 60 After some twenty minutes of fighting with mugs, fists, truncheons, and eventually bullets, the room was cleared, and the battered and bloodied Nazi combatants returned so Hitler could finish his speech. Five days later, Hitler addressed a contingent of SA men, celebrating their victory but also educating them in the ways of war. On the one hand, he quickly set to work mythologizing victory, declaring it the SA’s “baptism of fire.” He drew multiple analogies to the First World War including citing the Battle of Liége to argue that a well-organized small group can defeat a stronger enemy. But perhaps more telling he also criticized their performance saying the whole thing could have lasted just five minutes. Adopting the tone of a seasoned veteran he explained that “you must move as a group, table by table, and take them out one at a time. You must not despair if you get hit a few times. Anyone who goes into battle must expect that.”Footnote 61 His speech and his later reminiscences in Mein Kampf reveal much about how the movement made sense of beer halls as battlegrounds and ideological combat zones. The very name bestowed on the event—The Battle of the Hofbräuhaus—was militaristic and it was described in terms reminiscent of the First World War: fighting table by table, expecting some losses, and avoiding the howitzer shells whizzing overhead.

The SA men Hitler addressed had by and large missed the war and he left little room for interpretation about what the purpose of their fighting had been. Moving beyond just the tactical points of beating the socialists out of the room, he turned toward larger ideological aims too, underscoring that “when you hold firmly together, and always bring new young people along, that is how we will carry away the victory over the Jews.”Footnote 62 It was violence carried out in the name of a greater ideological aim, perpetrated by specific SA men, but indicative of the youthful core of the movement. The enemy was not just the socialist disruptors but the Jews behind the scenes who could only be combatted by a movement of young men committed to the goal. In the aftermath of this conflict the movement not only espoused antisemitism in their own events but also actively fostered it beyond them. Speaking to about a hundred and twenty-five SA men later that month, Hitler urged the SA to infiltrate the political meetings of rival groups and heckle and disrupt every speaker “until he addresses the Jewish Question.”Footnote 63 This spilling out of SA violence receives more treatment in the next section but this was how ideologies, practices of violence, and the pursuit of spatial control were combined in Munich’s beer halls. The Battle of the Hofbräuhaus went on to assume mythical significance for the movement. On the one-year anniversary, Hitler stressed (and exaggerated) both the events and this larger ideological aspect, claiming that the small group of SA men bested “nearly 400 soldiers of the Judeo-Marxist hit squad.” In still later accounts, he would put the number as high as 800.Footnote 64 Subsequent narratives of the event not only emphasized the imbalanced numbers and the triumph against all odds as a symbol of SA strength, but also as a signal of “the superiority of the party’s ideas.”Footnote 65 It was not just a bar fight but a battle for control of perhaps the most crucial space for public discourse in the city.

The Battle of the Hofbräuhaus exemplifies how the early Party positioned the beer hall space as a battleground not only in the present moment but in memory, using war-like imagery to romanticize their violent actions and to glorify their movement. In the process, they became part of a larger effort to forge and strengthen masculine bonds. Just two weeks after the Battle of the Hofbräuhaus, for example, fifty-three SA men marched and drilled physical exercises for over an hour and a half under the command of a man named Böckel.Footnote 66 As they marched, they sang nationalist and antisemitic songs including the “Swastika Song,” the “Ehrhardt Song,” and the “Hitler Guard.” When they were done, they first received a schedule of events to show up for in the coming week including two mass meetings in the Hackerkeller and Hofbräuhaus. They then received feedback on the day, with Böckel praising their performance, except in one instance in which a man got a cramp and everyone marched on. He chastised, “We can never leave one of our comrades behind [on a march], and also not during a battle in the Hofbräuhaus.”Footnote 67 The criticism reveals not just an aspiration for closer camaraderie and the solidarity of the emerging Männerbund, but also an insight into what the training was for. Just weeks after the Battle of the Hofbräuhaus, and after receiving the schedule for the week, it is hard to miss the connection between paramilitary efficacy and the larger goals of the movement. As George Mosse wrote more generally, the purpose of physical fitness in Nazism was “not just the steeling of [a man’s] body, but the fulfillment of his worldview.”Footnote 68 Through to the eve of the Beer Hall Putsch, the SA and their growing network of rightwing paramilitary groups cemented their physicality, masculinity, and camaraderie in and around the beer halls. As the movement tightened its bonds with other groups on the völkisch right, the spaces played a similar role. In early 1923, for example, over six thousand men from various “patriotic” organizations gathered in southwestern Munich for four hours of physical exercise before moving to the Salvatorkeller and Bürgerbräukeller to drink and solidify their masculine bonds.Footnote 69

Spilling out of the Beer Halls

As the previous section made clear, it can be hard to demarcate the mass movement dynamics at play in a beer hall event and the culture of youthful and violent camaraderie of the SA. The SA emerged in part to police beer hall events and thereby both shifted the experience of them and evolved in response to them. This section balances the actions and culture of the SA as it left the nest of the beer hall with the ongoing importance of these spaces for the early movement. After Hitler assumed unchallenged leadership of the NSDAP in the summer of 1921 he also sought to tighten his control on the movement and party beyond Munich. Over the next year and a half, the Munich SA traveled outside the city, shoring up the uniformity of the movement and exporting their practices and culture. From excursions into and beyond the city to contesting control of the city itself, the process by which radical political aims fused to efforts at spatial control spilled beyond the beer halls. This was particularly true for the SA, but for the movement more broadly, Munich’s beer halls remained central to the mass political drive of the party.

In the months leading up to the “Battle of the Hofbräuhaus,” political conditions both in Munich and beyond transformed dramatically. For one, Munich and Bavaria were shaken up when the dissolution of the massive Citizens’ Defense Force (Einwohnerwehr) led to experienced paramilitary men finding new organizational homes. Most went to new bourgeois-conservative-restorationist groups like Organization Pittinger and Bund Bayern und Reich, but many also turned to the völkisch and populist options provided by Bund Oberland and the NSDAP/SA.Footnote 70 But more broadly too, larger conditions kept politics unstable. For example, as prices rose and currency depreciated, food prices in 1921 were almost eight times higher than they had been at the end of the war. Moreover, in August, Gustav von Kahr further undermined national political legitimacy when he rejected the national state of emergency declared by Reich President Friedrich Ebert after the assassination of Reich Finance Minister Matthias Erzberger. In this context, Hitler and the SA stepped up their agitation, crashing a September meeting of the Bavarian separatist Bayernbund in the Löwenbräukeller which descended into a brawl.Footnote 71

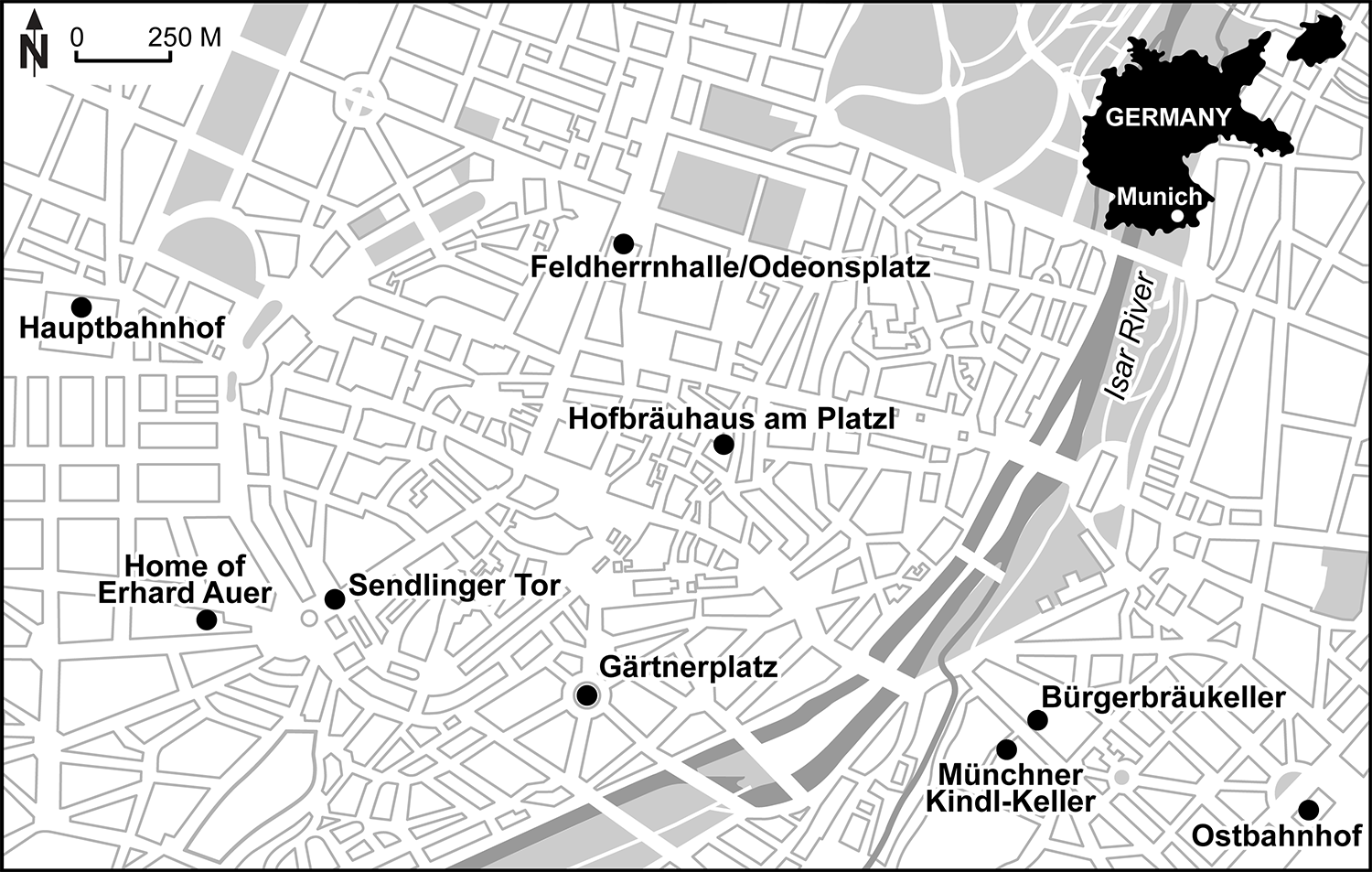

The violence also erupted outward as the movement extended its combination of ideology, violent practice, and pursuit of spatial control. In mid-October, a group of some seventy-five SA enforcers led by Emil Maurice marched from their meeting in the Hotel Adelmann on Isartorplatz to Munich Central Station in hopes of greeting Hitler as he returned from Vienna. Before the column embarked, Maurice declared that this was not just a meet-and-greet with Hitler but an ideological mission through the city; he finished his speech with the imperative that “every Jew we encounter will be beaten up.”Footnote 72 As they marched to Central Station, the men extended the spirit and the letter of the charge. On the way they sang antisemitic songs that dehumanized Jews and rendered them Other, juxtaposing “German land” and the “Jews Republic.” When they got to Central Station, despite a six-man police presence, they assaulted a bystander who called them “insolent brutes” (freche Kerle). The police intervened only to take the victim out of the station and made no effort to stop the group as they lingered on the platforms singing antisemitic songs while “Jews in the station gradually dispersed.” When the train arrived, the group was disappointed to find that Hitler had already gotten off at Ostbahnhof. Map 1 Rather than giving up, they marched on in that direction, zigzagging along a route some four and a half kilometers long. On the way, they stopped at the home of Ehrhard Auer where they hurled epithets about Jews and the Workers’ Councils until someone inside turned off the lights and they eventually moved on. As they continued toward Sendlinger Tor, the group encircled someone they identified as a Jew. They taunted him for his appearance but moved along after he repeatedly explained he was not Jewish, he just had a crooked nose—a defense that saved him, but perpetuated a stereotype. As it turned out, Hitler was not at or near Ostbahnhof, nor could he be found at local Party hangouts like the Gaststätte Eisernes Kreuz. Still, the actions of the group had extended the spatial dynamics already present in the beer halls into the train station and onto the streets. And it had also generated support. As the column marched along Müller-, Fraunhofer-, and Reichenbachstrasse—streets in the area of Gärtnerplatz—frequent calls of “Heil” and “Bravo” could be heard emanating from the windows.Footnote 73

Map 1: Points of Reference in Munich. Credit: Syracuse University Cartographic Lab.

That the SPD and Erhard Auer in particular were central targets of such violence reflects not only the relatively weak position of the KPD in Munich and the general conflation of all forms of Marxist politics, but also the fact that Auer and the SPD were core pillars of the much hated parliamentary republic. Since December 1920 at the latest, the NSDAP had taken a particularly hostile position toward Auer after he denounced Hitler’s call for a pogrom while speaking in the Hofbräuhaus. Like the process by which Nazi rhetoric evolved into deeds in the case of Munich’s Jews, Auer and the SPD became physical targets too. It began with beer hall speeches and articles in the Völkischer Beobachter, but by the autumn of 1921, Auer had to dodge bullets while walking home and the offices of the Münchener Post were attacked, windows smashed, and swastikas painted on the walls. Just six days after SA men shouted at his home on their march through the city, another assassination attempt was made on Auer’s life. In both cases, it remains unclear who was behind the attempts, but the SPD blamed the Nazis.Footnote 74 In response, Auer, the Münchener Post, and the SPD became more outspoken in their hostility. In multiple speeches in the Landtag and in letters to numerous Federal Ministers and even the Chancellor, Auer denounced Nazi violence and the inaction of the Bavarian state and police, a state of affairs that led to further political militarization.Footnote 75 As one reporter in the Münchener Post put it in detailing street violence in September 1922, “almost every day brings new evidence of what the swastika-wearing rowdies—that were so lovingly nurtured under the Kahr-Pöhner era—are allowed to do in Munich.”Footnote 76

The spatial practices taking shape in the Nazi movement were not limited to Munich. The party already had cells throughout Bavaria by this time, but central control remained weak. In the late summer and autumn of 1922, Nazis from Munich traveled to such places and brought with them their own organization and modes of operation. In August and September, for example, Munich Nazis made several illustrative excursions to Bad Tölz, a town on the Isar River some thirty kilometers south of Munich. In mid-August, almost twenty SA men rode their bikes to the town before setting up shop at the local party hangout, Gasthof zum Ostwaldbräu. Upon arrival they unfurled a large swastika flag and put it in a window for all to see. After an hour of socializing and drinking, they assembled with the flag to march through the town singing antisemitic songs including the “Ehrhardt Song” and “Throw the Jews Out.” When they marched past the Park Hotel, some of the Jewish guests emerged to heckle the column and, in some cases, hit the men with sticks. The local police found the whole episode “provocative and annoying” and in violation of the public peace, but they did nothing about it.Footnote 77 Writing of this episode, Daniel Siemens’ rightly summarizes it as such:

The day trip started with several hours of physical exercise (such as cycling), continued with the symbolic occupation of a central public place in the city (the hotel) and the performance of rites of male sociability there, and reached its climax with the successful provocation of the hotel’s affluent Jewish guests. The trip thereby provided key benefits popular among male youth: an intensified appreciation of the body and its physical strength, the opportunity to feel manly by the demonstration of power and energy, and, last but not least, a means to enjoy collectively experienced ‘fun.’Footnote 78

More than a typical case of rightwing masculine bonding, the episode fused ideology and spatial control. Moreover, it formed part of a practice of expansion. A few weeks later, the local party in Bad Tölz held its first ever public event, an event at which Hitler spoke, and which was supported by the presence of Munich SA men. Earlier that day, three trucks full of Munich Nazis, identified by their flags and swastika armbands, loudly drove through Munich throwing fliers en route to Bad Tölz, where they harassed the Jewish guests in the Park Hotel and at the town spa before helping to keep order at Hitler’s speech.Footnote 79 The episode at the hotel was not a one off, but rather part of a concerted expansion into Bad Tölz.

Beginning around this time, party events took a turn, becoming not just bigger or more geographically expansive, but more organized and more openly hostile to the powers of the state. In August, Hitler spoke to some 5000 people in the Kindl-Keller and urged the SA and anyone else who would listen to become agents of a mass coup attempt. In September, the party defied a police ban on hosting a mass event. In October, Munich SA men continued to travel and spread their influence and practices. Some 800 traveled by train with Hitler and most of the upper leadership to Coburg in Upper Franconia to participate in “German Day.” They ignored warnings of public incitement, unfurled banners, marched through the streets, and brawled with local socialists for ten minutes before they “triumphantly claimed the streets of Coburg as theirs.”Footnote 80 One must imagine that on a train ride that lasted four hours or more, the men had gotten drunk. It was, after all, the cultural norm of their Munich movement. That Saturday night, some twenty to thirty Nazis stumbled out of the local Hofbräuhaus and brutally assaulted a socialist named Dürrkopp. When the police inquired, Hitler reportedly claimed that “we are ourselves the police,” which the Münchener Post noted was an indication that state authorities had accepted Hitler’s terror in Coburg just as readily as their counterparts in Munich. The city was, the Post claimed, on the brink of a “Jewish pogrom” and the next day, defying police orders, the Nazis and their supporters marched through the city singing antisemitic songs and intimidating Jews, workers, and other onlookers and demonstrators.Footnote 81 The Post was not alone in assigning significance to the event. For his part, Hitler later inflated the significance from his jail cell, writing that “many for the first time recognized in the National Socialist movement the institution which in all probability would someday be called upon to put a suitable end to the Marxist madness.”Footnote 82 This is perhaps not a surprising reflection given that mere weeks after the Coburg incident, growing aspirations for a coup took inspiration from Mussolini’s so-called March on Rome which “suggested the model of a dynamic and heroic nationalist leader marching to the salvation of his strife-torn country.”Footnote 83

Back in Munich, Hitler and the party leadership worked to coordinate and centralize the growing movement and once again, the city’s beer halls were crucial. On November 30, 1922, for example, the party held five simultaneous meetings at 8:30pm at the Löwenbräukeller, Bürgerbräukeller, Thomasbräukeller, Schwabingerbrauerei, and of course, the Hofbräuhaus. Thousands of fliers and posters flooded the streets in the hours before and by the time of the events, the rooms were full—so full in fact that the doors were closed at each one and the police had to hinder further entrance at the Schwabingerbrauerei and the Hofbräuhaus. The Nazis were prepared for significant conflict. A week earlier there had been an ordinance against the carrying of weapons and while the police claimed no rubber truncheons were seen, many “walking sticks” were reported and, lest we forget, beer halls themselves provided an abundance of projectiles and melee weapons in the form of dishes, chair legs, and beer steins.Footnote 84 Armed or not, SA men were stationed throughout the events, but they had also assembled what police chief Eduard Nortz called a “reserve assembly protection force” in a bar in Gärtnerplatz which was equipped with two personnel trucks at the ready to transport a contingent of party toughs—presumably drinking at the bar—to wherever a fight broke out.Footnote 85 The events went off without significant disturbance but were an important spectacle. Each one adopted a resolution denouncing the revolution and declaring the impotence of parliamentary government in the face of national reconstruction. Hitler spoke at each, rushing around to each location where he and the respective event hosts—including Munich leaders like Hermann Esser and Dietrich Eckart as well as Austrian Nazis Walter Ruhl and Sepp Koller—hit the standard talking points, railing against Versailles, the Jews, Marxism, and the importance of national and pan-German awakening.Footnote 86 The message and the coordination depended on controlling the beer halls with both Saalschutz detachments and the militarized mobile “protection force.”

The year 1923 was of course a pivotal year. Most infamous is the November coup attempt, the Beer Hall Putsch. The year also started with a crucial event, the first full party rally on the last weekend of January. As part of centralizing the party, Munich hosted Nazis and their supporters from across Bavaria and in some cases beyond it. Fearful of a potential coup, the Interior Ministry declared a state of emergency and canceled the public outdoor events. Hitler vigorously protested, Ernst Röhm called in the support of the Reichswehr, and Police President Nortz proved disinterested in enforcing the ban.Footnote 87 The rally began with another series of simultaneous events—this time twelve of them—hosted in breweries and the major Munich beer halls. As they had the previous November, men stood ready to be deployed as needed to battle with socialists and other opponents. Trucks ferrying SA men from one beer hall to another were seen crisscrossing the city as the Nazis sought to link spaces under their control and perhaps to artificially boost their apparent omnipresence.Footnote 88 That first night, Hitler was greeted “like a savior” by the roaring crowds. In the Löwenbräukeller, he strode in for the first time with his arm raised in the air—a gesture that would of course become standard to the party.Footnote 89 The next day, the hungover masses began drinking again at noon and continued to do so late into the evening with major midday events like swearing in the swastika flag. While most public events took place in the Marsfeld, near the Circus Krone, the bulk of the weekend and the informal bonding among Nazis from across Bavaria took place in Munich’s beer halls. There was no violence that weekend. The police later reported—likely in a justification of Nortz’s passivity in the run-up—that the Saturday night was one of the quietest in a long time.Footnote 90 Still, there were clear signs that tensions in Munich were coming to a head. On that “quiet” Saturday, Nazis occupying the Pschörrbräu openly threatened Erhard Auer who was dining there that night. The policeman Franz Lang escorted Auer home and the latter confessed that his own protection guard was also stationed in the city. In his report, Lang reflected on the fact that the police had indeed failed to rein in political combat organizations which seemed to “strengthen the germ of civil war.”Footnote 91

In the next six months, the Bavarian government and the Munich police became more concerned about the political threat posed by the Nazis and their right-wing allies. Still, they remained more concerned about leftist forces. In Saxony and Thuringia, the “Proletarian Hundreds” appeared poised to stage a Moscow-inspired revolution and the Munich Police worried that the SPD Security Division was similarly aiming at the bourgeoisie. That September, the police advised disbanding the socialist force—which had emerged in response to Nazi violence and aimed to protect the Republic—but not the Nazi SA.Footnote 92 On the right, the Nazi movement continued to tighten its relationship to other far-right organizations, following the pattern of physical activity and copious beer consumption.Footnote 93 The movement continued to grow in the face of spiraling inflation and political uncertainty as many Münchner flocked to the beer halls to hear potential solutions from the magnetic Hitler. By September, the Nazi Party was the only party in Munich that could overcome the challenge of steep prices to still fill the city’s enormous beer halls.Footnote 94 One exception, of course, was official government events, such as the one in the Bürgerbräukeller in November 1923, when Gustav von Kahr’s speech to some three thousand attendees was disrupted in what became known as the Beer Hall Putsch. By that point, Hitler and Kahr had become estranged as the latter, a conservative antisemite but a monarchist at heart, sought to distance himself from the growing power of the völkisch right.

The Beer Hall Putsch was the culmination of many of the spatial practices developed by the Nazi movement over the course of several years in Munich’s beer halls. There was no doubt an element of newness and intensity, but the course of events demonstrated both the lack of organization and preparedness and the simple fact that beer hall tactics were ill-suited to revolutionary strategy. The opening drama of the Putsch was quite literally a battle for control of the Bürgerbräukeller: armed men securing the room, a shot fired into the ceiling, a machine gun trained on the door, and Hitler’s alleged proclamation of spatial control: “the German revolution has broken out… This hall is surrounded!”Footnote 95 The putschists quickly set to the work of both revolution—beginning by securing the endorsements of Kahr, Seisser, and Lossow—and asserting control of the space. Some officials, like members of Minister President Knilling’s cabinet were removed from the hall and placed under house arrest in Julius Lehmann’s villa. For other sorts of enemies, namely Jews, Nazi control of the Bürgerbräukeller transformed the space itself into a prison. When SA men learned that the Jewish factory owner Ludwig Wassermann was in the room, they “arrested” him, and rather than transferring him to house arrest or the like, they imprisoned him on the spot. As the Putsch went on, the Bürgerbräukeller continued to serve this special function as men from the SA and Bund Oberland scoured the city for people with “Jewish sounding” names. Many Jews and alleged Jews were arrested, including Justin Stein, Isidor Bach, Julius Heilbronner, and Karl Luber, the son-in-law of Erhard Auer. In the latter case, Luber was abducted from Auer’s home after the SA broke in and ransacked the space looking for Auer himself. In most cases they were taken to be held in special custody in the basement of the Bürgerbräukeller, where they were beaten and threatened with being shot.Footnote 96 The use of the space as a prison reveals a great deal about how the movement understood its spatial authority. While political rivals were taken elsewhere, ideological enemies were concentrated in the tried and tested space of the beer hall.

The fate of the coup is well known. Failing to take charge of major governmental centers and having lost control of Kahr, Seisser, and Lossow, Hitler and Ludendorff set off on their final march which ended in a shoot-out in the streets near the Feldherrnhalle. As the smoke settled that morning, back in the deserted Bürgerbräukeller, the space was devastated. There were bullet holes in the ceiling and the hall was a wreck. The management hit the Nazi Party with a bill that included having exhausted all the food and beer on the premises, as well as compensation for 143 steins, 80 glasses, 98 stools, and 148 sets of cutlery.Footnote 97 Beyond drinking the hall dry, one has to imagine that a large portion of the small wares, especially the steins and cutlery, were stolen for use as weapons as the Nazi movement and their allies sought to transform radical ideology into armed insurrection. The events of the Putsch were an extension and obvious radicalization, of earlier patterns. Yet, the Nazi movement had no clue how to stage a successful coup. Beyond Röhm’s capture of the District Military Headquarters on Schönfeldstraße, the major Reichswehr detachments did not join the cause and the putschists failed to capture key government, communication, and transportation centers—indeed in the latter two cases they made no effort at all. Rallying in and marching between beer halls was not great preparation for actual revolution. Still, the conquest of the Bürgerbräukeller was familiar and smooth and the use of it as an ad hoc prison for ideological opponents reveals the radicalization of claims to authority and practices of spatial control. The practices of beer hall violence that developed over the course of the previous four years were entirely present, but the larger strategy and the mass support was not.

Conclusion

Beer halls were not merely settings but spaces in which the social practices and ideological meanings of both urban life and the Nazi movement were under negotiation. By the early 1920s they became important sites for the movement as it built popular support, developed practices of violence, and extended ideologies into physical space. The NSDAP was far from alone in holding meetings in taverns, bars, and beer halls. But for a movement lacking the ideological coherence of Marxism in its various forms, the spaces themselves played a key role in early efforts to translate nebulous and radical ideological rhetoric into social and political practices and, ultimately, revolutionary insurrection. The specific postwar conditions of Munich and the desire to form a mass movement hostile to republican governance provided Nazi radicalism an opportunity to begin defining both “the people” and an embodied Other. As we have seen, for instance, rhetoric around the Jews—or the Jew—found physical expression on the bodies of pedestrians with large noses, Rabbis seeking to speak, and people with “Jewish sounding” names imprisoned in the Bürgerbräukeller. The embodied Other and the central drive to destroy the Republic collided in November 1923, but that moment can be fruitfully understood as the culmination of the beer hall politics that characterized the early Nazi movement.

The interplay of the physical space, ideological convictions, and performative behaviors in the volatile context of postwar Munich transformed the beer halls as a site of movement-building. As the Nazis worked to control beer halls, they developed a repertoire of spatial practices that would develop throughout the course of both the movement and the regime. The cultures of masculinity, camaraderie, and ideological violence fed into the extreme violence seen in the 1940s.Footnote 98 Even without that referent, the practices developed in Munich in the early 1920s continued into later, yet more extreme conflicts in both the Weimar Republic and the Nazi regime. Understanding how spatial practices evolved beyond postwar Munich remains a task that other scholars might fruitfully locate in the evolving dynamics of built, ideological, and lived space.Footnote 99 But looking at the contestation of Munich already reveals other important lessons learned and practices developed. Beyond the issues of violence and exclusion, for example, this study of the beer halls has implications for the later populist dynamic at the core of Nazism. Because the party was so small in these years and the events so sporadic, it could hardly be described as a fully realized mass or populist movement on the order of its Depression-era successes. But the foundation lines were there. In the exaltation of the Volk, the calling-in of “the people,” and the persistent denunciation of “illegitimate predators”—the November Criminals, the Jews, Marxists, and so on—the early Nazi movement sought to instigate a shift in political consciousness. Even if the Nazi movement would not achieve it for several years, their early beer hall politics and practices aimed to foster a widespread “righteous indignation” and a conviction “that basic political legitimacy has to be reordered.”Footnote 100

What Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl observed on a November night in 1922 was by that point a well-oiled machine, built over years to contest space through radical rhetoric and battle tactics. Between 1919 and 1923, Munich’s beer halls became the battleground for many political factions, but the Nazis evolved a particular spatial politics in which radical ideas became violent practices. The spaces were radical and seething with rage at the shame of Versailles, the new Republic, and the readymade scapegoats of Marxists and Jews. From rabblerousing speeches to the forced removal of Jews to an insurrection attempt that targeted both political and racial opponents, the progression described here reflects the transformation of spatial practices between a radical movement and an accommodating state.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008938925101301.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Teresa Walch, the members of the 2025 New Directions in German History Workshop at the University of Rochester, and the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions on various iterations of this article.

Robert Shea Terrell is Associate Professor of History at Syracuse University. His first book A Nation Fermented: Beer, Bavaria, and the Making of Modern Germany, appeared with Oxford University Press in 2024. He is currently working on a history of food and restaurants in Munich.

William Johnson is a High School World History Teacher in New Jersey. He graduated Summa Cum Laude from Syracuse University in May 2025 with a bachelors in Social Studies Education and European History.