Introduction

An overwhelming consensus among political scientists is that political parties are the cornerstone of democracy. Strong, ideologically driven, and programmatic parties are necessary for stable electoral competition (Gallagher et al. Reference Gallagher, Laver and Mair2011). Parties mediate between the public and policymakers by translating people’s demands into policy (Aldrich Reference Aldrich1995). They also mobilize the electorate during and beyond election day (Verba et al. Reference Verba, Nie and Kim1978), and party elites impose discipline within Congress, urging members to align with a broader agenda (McCarty et al. Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2001). Parties are significant even for people who care little about politics; simply knowing a candidate’s party affiliation allows voters to make informed choices and hold leaders accountable (Dalton and Wattenberg Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2002). As a result, it is difficult to envision a functioning democracy and stable electoral competition when parties are weak and disconnected from voters.

Nevertheless, parties are not performing at their peak worldwide. A good example of this trend is Chile, where previous research has found that parties have weak roots in society (Luna Reference Luna2014; de la Cerda Reference de la Cerda2022), fail to represent the interests of the electorate (Luna and Altman Reference Luna and Altman2011; Luna and Rosenblatt Reference Luna and Rosenblatt2012), and struggle to translate voters’ demands into policy (Morgan and Meléndez Reference Morgan and Meléndez2016; Disi and Mardones Reference Disi and Mardones2019). In this sense, we should expect an unstable, personalistic, and volatile electoral competition.

However, we observe remarkable ideological stability. Until 2019, center-left and center-right party coalitions dominated the electoral arena without serious challengers, and the country exhibited low levels of electoral volatility (Roberts Reference Roberts2015). Although the last decade witnessed a party realignment, new political actors are easily classified within the traditional left-right spectrum (Visconti Reference Visconti2021). While there have been independent presidential candidates, and others with vague ideologies, they have either disappeared or adopted clearer ideological stances. Elections, therefore, are more stable and predictable than expected in a country with such a debilitated party system.

We argue that the persistence of ideological identification, as opposed to party identification, is a key factor explaining stability in electoral competition. Ideological persistence, we claim, acts as a stabilizing force, a type of glue that articulates electoral politics. Why does ideology persist? We expect to demonstrate that, while ideology is usually defined as a set of political attitudes, it also comes with an affective component (Jost Reference Jost2006); thus, it goes beyond preferences towards specific policies (Mason Reference Mason2018). Ideology, therefore, persists because it is not only a bundle of preferences, but also displays features of an enduring social identity, sharing similarities with partisanship or religion (Green et al. Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002; King 2).

To test this argument, we first provide descriptive evidence about party affiliation, ideology, and preferences over issues. We show that ideological identification has been fairly stable, unlike partisan affiliation, which exhibits a sharp decline over time. We also find that ideology is transmitted across generations and that ideological groups display out-group animosity. In contrast, issue preferences prove highly volatile, even over short periods, highlighting the distinction between ideological identity and policy views.

Second, we provide causal evidence, addressing whether people vote based on ideological or issue alignment. Results indicate that ideological voting consistently outweighs issue voting. For example, a left-wing and pro-immigration voter would rather prefer a left-wing and anti- immigration candidate to a rightist pro-immigration, and vice versa.

Third, we use topic modeling to analyze text data from open-ended questions. In these questions, we asked respondents words that came to their mind when thinking about “the Left” and “the Right.” Overall, we observe that two topics emerge: first, an ideological label, and second, a value judgment, with an affective component. When looking at people with an ideology—left or right—we clearly see that the in-group is considered virtuous, and the out-group as morally corrupt. These results provide evidence for the existence of symbolic boundaries and in-group affect.

Fourth, we examine how the 1988 plebiscite that ended 17 years of dictatorship was a “critical juncture” that reinforced ideological identification. Using a regression discontinuity design (RDD), we show that voting eligibility substantively increased ideological identification. Given the stability that Chilean electoral politics has exhibited after such an event, we believe that the positions acquired then endured the passage of time (Tironi and Agüero Reference Tironi and Agüero1999), although there are clear signs that the post-authoritarian cleavage is weakening.

We provide different pieces of evidence showing how ideology is the key factor that structures electoral competition in Chile, that ideology has a familial and affective component, and that ideological identification was reinforced in the 1988 plebiscite. We argue that a plausible and coherent interpretation of these results is to view ideology as displaying features of a social identity. This perspective allows us to link ideological identification to a sense of belonging to a social group (Scheepers and Ellemers Reference Scheepers and Ellemers2019). Interpreting ideology in this manner provides a compelling explanation for the article’s findings.

Our article contributes to four areas. First, we use the lens of social identity theory to reinterpret ideological identification as a socially rooted and affectively charged political marker in a context of weak party institutionalization. While previous research on ideological voting in Chile has emphasized spatial models—where voters minimize distance between themselves and candidates—we argue that ideological attachments also operate through cultural, familial, and affective channels. These attachments are not merely about issue congruence; they carry symbolic, moral, and social meanings that more closely resemble identity-based commitments.

Second, our article contributes to the literature on political development in Latin America by exploring how ideological stability can persist despite party system erosion. Ideology, we claim, is not only a by-product of policy preferences or anti-party sentiment, but also a durable marker shaped by key political events, intergenerational transmission, and socialization processes. In this sense, our study is in dialogue with recent work on political identities and negative partisanship in the region, but offers a distinct theoretical lens (Meléndez Reference Meléndez2022).

Third, we challenge the prevailing assumption that party decline necessarily leads to electoral volatility and instability. While previous research has extensively documented the weakening of traditional party structures in Chile and Latin America (Luna and Altman Reference Luna and Altman2011; Luna and Rosenblatt Reference Luna and Rosenblatt2012; Luna Reference Luna2014), our findings reveal that ideological stability endures despite the erosion of political parties. This suggests that even in fragmented and unstable political landscapes, ideological identity can provide a stabilizing force, anchoring political preferences over time.

Fourth, we demonstrate how critical political moments shape and solidify ideological identification. High-intensity political events, particularly those that generate strong emotional and social mobilization, can have long-lasting effects on individuals’ ideological attachments. More broadly, our results suggest that once ideological identification is established, it remains durable, even in contexts of weak partisanship, electoral fragmentation, and institutional instability.

While much of the literature has been pessimistic about the future of democracy, given the lack of trust in political parties and the collapse of class-based organizations, we offer a more nuanced view. When understanding ideology this way, we could expect that societal forces might create political stability. In this vein, we argue that the deeper societal foundations that shape ideology are the true cornerstone of democracy, far more consequential than electoral rules, district sizes, or even political parties.

Ideology and Parties

The traditional concept of ideological voting can be traced back to Downs (Reference Downs1957), who proposed a model based on a continuous left-right ideological scale, allowing voters and politicians to position themselves accordingly. This scale serves as a synthesis of political preferences, presuming some basic shared understanding of what constitutes the Left and the Right. Empirical research has built on Downs’ foundational idea of an ideological continuum, demonstrating that voters’ ideological placements remain stable over time (Knight Reference Knight2006; Jost et al. Reference Jost, Federico and Napier2009) and play a crucial role in explaining electoral choices (Fleury and Lewis-Beck Reference Fleury and Lewis-Beck1993; Calvo and Murillo Reference Calvo and Murillo2019).

The political sociology literature offers an explanation of where ideology comes from and its connection to political parties. The classic examination of parties in Europe ties ideology, defined as a set of beliefs about collective life, to certain cleavages ingrained in society. Such cleavages reflected the primary sources of political conflict, in turn affecting individual political preferences. Ideology, then, can be seen as a by-product of societal structures manifesting in a political worldview (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). This analysis assumes that political parties are, in essence, the reflection of these societal cleavages. In other words, parties were the organizational manifestation of social cleavages, and ideology served as the interpretative and mobilizing force that links social divisions to political action.

The connection between political parties and traditional class cleavages has significantly weakened. Globally, the rise of single-issue parties lacking strong ideological coherence has challenged broader, more established parties. Additionally, traditional parties face accusations of elitism and unresponsiveness, leaving voters with fewer meaningful choices. In Latin America and beyond, scholars have observed that political parties have weak societal ties, fail to represent the electorate’s interests, and exhibit low levels of popular support, as reflected in public opinion data (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2006; Lupu Reference Lupu, Carlin, Singer and Zechmeister2015).

If political parties are in decline, we might expect ideological identification to fade as well. Since parties articulate social cleavages and are often held together by ideology, their demise would naturally weaken ideological alignment. In the absence of parties, we should expect high levels of volatility, with elections turning into personality contests. Yet this has not been the prevailing pattern in many democracies. Instead, we observe striking stability in electoral outcomes, with contests still structured by some version of the left-right divide. In many cases, new parties have achieved rapid electoral success, but these parties are generally iterations, and often more radical versions, of the old ones.

Why do elections and political competition remain ideologically grounded without strong parties? Put another way, a puzzle emerges in countries that exhibit stable and programmatic electoral competition despite parties lacking societal roots, legitimacy among the electorate, and robust organizational capacity.

The Concept of Social Identity

As mentioned in the introduction, we argue that ideological identification in Chile displays several features consistent with identity-based attachments.Footnote 1 In this sense, it is necessary to explain what a social identity is and how it can become politicized.

A social identity is based on the notion of social categorizations, where humans classify others into groups to organize and better understand the social world. This process can lead to in-group attachment, which typically implies the identification of an out-group (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel and Turner1979). Importantly, many types of groups, defined by age, race, ethnicity, religion, and party identification, can potentially become social identities, (Norris and Mattes Reference Norris and Mattes2003; Cameron Reference Cameron2004; Kuo et al. Reference Kuo, Malhotra and Mo2017; Green et al. Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002; Trachtman et al. Reference Trachtman, Anzia and Hill2023). Scholars have identified different factors that transform group membership into an identity, such as intense political events (Tilly Reference Tilly2003), social conflicts (Kim and Zhou Reference Kim and Zhou2020), personal experiences (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2005), or cultural changes (Gennaioli and Tabellini Reference Gennaioli and Tabellini2019).

A key question is how a social identity can become politicized. A good example is ethnicity in Latin America. While this is a multiethnic and multicultural region, ethnic and cultural minorities have been historically neglected by the state (Van Cott Reference Van Cott2007; Madrid Reference Madrid2012). However, in recent decades, ethnic mobilization has been on the rise, translating into successful ethnic parties, such as Movimiento al Socialismo in Bolivia (Alberti Reference Alberti2015; Anria Reference Anria2018). Therefore, a group that was not salient in the recent past mutated and turned into a relevant political identity with substantive electoral implications.

If ideology displays features of a social identity, then it is a key component of how people perceive themselves and understand the world. Being leftist or rightist goes beyond a set of beliefs on, for instance, the role of the state, or regarding individual liberties. Instead, it is an essential feature of how people define themselves. In this sense, ideology could even shape social, communitarian, and affective life. Besides this social dimension, there is also a cognitive one. Ideology shapes our understanding of the world. It is a framework used to make sense of political events and to establish positions on different issues.

Social identities have consequences. Indeed, scholars have identified effects on electoral choices (Andersen and Heath Reference Andersen and Heath2003), political preferences (Klar Reference Klar2013), non-political attitudes (Phillips and Carsey Reference Phillips and Carsey2013), and even participation in protests (DeLeon and Naff Reference DeLeon and Naff2004). Likewise, it could also have arguably undesirable effects, such as an intensification of prejudice, in-group and out-group biases, and negative attitudes toward the opposition party (Miller and Conover Reference Miller and Conover2015; Iyengar and Krupenkin Reference Iyengar and Krupenkin2018). In addition, ideology can create symbolic boundaries, that is, conceptual and moral distinctions that define who belongs to the in-group and who is excluded. These boundaries are visible when, for instance, ideology is used to deploy contrasting moral judgments to differentiate “us” from “them.”

Some critics of the role of ideology hold that voters do not understand the meaning of Left and Right (Converse and Pierce Reference Converse and Pierce1986); therefore, they will struggle to vote following traditional spatial models, where voters minimize positions between them and the competing candidates. Precisely, group membership does not require a sophisticated understanding of the policies promoted by each side; instead, it just requires identification with your in-group and differentiation with your out-group. That being said, we do not deny a spatial component in ideological voting; instead, we claim that for some people, a movement between left and center-left could be less costly than an analogous change between center-left and center-right, because the latter would imply moving to “another tribe.”Footnote 2

Hypotheses

To test the validity of our argument—that is, establishing the centrality of ideology, and its connection to social identity—we need to find evidence supporting these four assertions:

1. Ideological alignment is the primary driver of voting decisions for an important share of the electorate.

2. Ideological identification should mean more than a collection of preferences over issues.

3. Ideological identification should have some social and familial component, such as intergenerational transmission.

4. People holding ideologies should exhibit some degree of in-group bias and out-group animosity.

The logic of hypothesis 1 is straightforward. The first-order priority of an article that highlights the importance of ideology is to prove that, in fact, ideology drives voting decisions as opposed to other drivers, such as issue alignment. Regarding the second hypothesis, we claim that if ideology has an identitarian component, it should be more meaningful than a set of positions over issues discussed in the public sphere, such as the economy, immigration, climate change, and others. In other words, there must be a component of ideology that is not captured by, for instance, an index of preferences on a set of items. We will provide evidence of these two hypotheses through a conjoint experiment that examines voting patterns of different groups, and that uses different definitions of ideology. Hypothesis 3 touches more directly on the idea that ideology is a social identity. If that is plausible, then we should observe some correlation between the political views of people and their parents, since identitarian markers are usually transmitted through the family. Hypothesis 4 builds on the idea that social identities involve not only attachment to the in-group but also animosity toward the out-group. In other words, individuals with a defined ideology tend to attribute moral virtues to their own group and moral corruption to ideological opponents.Footnote 3

Chile as Case Study

While the identity-based view of partisanship is well-established in the United States (Green et al. Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002; Mason Reference Mason2018) and in some multiparty systems (Bankert et al. Reference Bankert, Huddy and Rosema2017), our study extends these insights to the Latin American context, where low levels of partisanship are the norm.

The case of Chile provides an ideal opportunity to study ideology as the structuring force of electoral politics. Chile has had a long history of ideological competition that dates from the last century (Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela1985; Montes et al. Reference Montes, Mainwaring and Ortega2000; Torcal and Mainwaring 2003; Navia and Osorio Reference Navia and Osorio2015; Valenzuela et al. Reference Valenzuela, Scully and Somma2007). During the twentieth century, the country developed a programmatic party system, with strong parties clearly aligned either with the left (e.g., Communist and Socialist), the Right (e.g., Conservative and National), and the Center (e.g., Christian Democrat and Radical) (Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995). The presence of these well-defined parties with distinct programmatic agendas fostered ideological identification among the public.

Even when the Pinochet dictatorship tried to depoliticize society, the authoritarian experience reinforced ideological identification. The 1988 plebiscite was a critical milestone in defining people’s political identity. In fact, support and opposition to Pinochet were articulated around two broad coalitions: the center-Left, who were against him, and the Right, who supported him (Valenzuela and Constable Reference Valenzuela and Constable1989). As a result, the concepts of left and right were firmly attached to the evaluation of this 17 year dictatorship (Tironi and Agüero Reference Tironi and Agüero1999).

In the post-authoritarian period, political parties positioned themselves clearly along the left and right ideological spectrum (López et al. Reference López, Miranda and Valenzuela-Gutiérrez2013; Argote and Navia Reference Argote and Navia2018), with voters using that information to make consistent electoral decisions (Zechmeister Reference Zechmeister2015; Calvo and Murillo Reference Calvo and Murillo2019; Visconti Reference Visconti2021). The left-of-center parties, ranging from the centrist Christian Democrats to the leftist Socialist Party, embraced a social democratic platform, advocating for income redistribution and more state intervention. Right-wing parties leaned towards a more conservative social agenda with market-oriented values, emphasizing economic freedom and limited government (Luna Reference Luna2014). This partisan landscape remained stable until the 2010s, when new parties emerged on the Left, challenging the center-left establishment. The main leader of these new challengers was Gabriel Boric, whose meteoric political career catapulted him to the presidency in 2021.

Right-wing parties also had challengers. A new far-right party, Partido Republican, started to make strides in 2017; by 2021, their presidential candidate, José Antonio Kast, defeated the traditional center-right, advancing to the second round of the presidential election. Even if the advancement of new political parties has changed the partisan landscape, such realignment was not led by non-ideological outsiders. Instead, the new actors are clearly identifiable with a position in the left-right spectrum (Visconti Reference Visconti2021).Footnote 4

Descriptive Evidence

Data and Measures

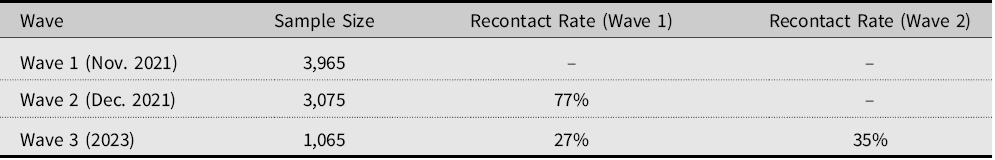

For our descriptive analysis, we draw on two data sources. First, we use the publicly available data collected by Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP) between 1994 and 2023. Each cross-section of the CEP survey, which was conducted face-to-face in all its iterations, is nationally representative. In most of the waves, CEP has asked about ideological and partisan identification. Second, we engaged in primary data collection, using Netquest, a research firm with extensive experience in Latin America. This data was collected online, using a quota approach resembling the Chilean census, stratifying in key demographics such as age, gender, region, and education. This data collection effort is part of a larger project whose aim is to study political attitudes using panel data. We collected the first two waves (3,965 and 3,075 observations, respectively) in November and December 2021. Two years later, in 2023, we recontacted about 25% of the original sample, leaving us with a sample size of 1,065 respondents (see Table 1). We use waves 2 and 3 for the descriptive analysis presented in this section. We will indicate which sample we are using in the figure and table notes.Footnote 5

Table 1. Sample Sizes and Recontact Rates Across Waves

To measure ideology, we asked about self-positioning on the left-right scale, where 1 means extreme left and 10 means extreme right. We defined a left-wing person as one who responded between 1 and 4; a right-wing person as someone positioned between 7 and 10; and a centrist person as one choosing either 5 or 6 (see the distribution of ideology in Figure A1 in the Supplementary Material). Approximately 75% of the sample identified with some ideological position in the first wave of the panel data. Meanwhile, we define party affiliation as equal to one if the respondent identifies with any party, zero otherwise.

We also use questions about preferences regarding policy issues, including immigration, feminism, and the role of the state in the economy. In the case of immigration, we asked the following question: “With respect to immigration, could you tell me which statement is closer to your beliefs?” The answers were: 1) The government should decrease the number of immigrants by closing the border or expelling illegal immigrants. 2) The government should encourage immigration. 3) The government should keep the current policy, keeping the same number of immigrants. Regarding feminism, we asked “Do you consider yourself a feminist?” and the answers were either yes or no. In addition, we examine questions to measure the voting preferences of respondents’ parents.

If ideology displays features of a social identity, we should observe a clear correlation between the respondent and her/his parents, as the family is a key source of socialization. To this end, we asked respondents their recollection of whether their parents voted against or in favor of Pinochet in 1988. Finally, we attempt to measure out-group animosity by asking if they would never vote for the Right or the Left, or if they would depending on the candidate. Note that this statement is quite strong, as the word “never” implies in every circumstance.

Results

When looking at the trend of ideology over time using repeated cross-sectional data (Figure 1), we observe fair levels of stability. In fact, the percentage of respondents identified with either the Right or the LeftFootnote 6 is similar in 2023 compared to 1995; 18% and 20%, respectively. There is, however, a transitory increase of respondents identified with no ideology, peaking in 2019, precisely in the middle of an acute social and political crisis, whose main theme was a generalized discontent with the political establishment (Somma et al. Reference Somma, Bargsted, Disi Pavlic and Medel2021; Cox et al. Reference Cox, González and Le Foulon2024; Argote and Visconti Reference Argote and Visconti2023).Footnote 7 However, the trends in partisanship show a very different picture. Figure 2 displays party identification over time: if in 1994, more than 70% of Chileans identified with any of the existing parties, such percentage decreased to 36% in 2023. It is worth noting that, again, the lowest levels of party identification occurred in 2019; since then, there has been a slight resurgence, which is mostly explained by the rise of the far-right Republican Party.Footnote 8 The analysis of issues over time also shows high degrees of instability, as Figure A2 shows. For example, pensions were not even a priority in the 1990s and early 2000s, but they rose to the top by 2019. On the contrary, although poverty was a key issue in the 1990s, it is less of a priority nowadays.

Figure 1. Ideology Over Time 1995–2023.

Source: CEP. Number of observations: 38,388.

Figure 2. Party Affiliation Over Time 1994–2023.

Source: CEP. Number of observations: 78,432.

We can now turn to the descriptive analysis of our panel data over two waves. Figures 3 show the distribution of ideology in 2021 and 2023. We see that both distributions are practically identical; the only change is a tiny decrease among people without ideology (see Figure A3 for more details). However, such comparison only shows the aggregate distribution, without considering possible changes within respondents. In Table A1, we observe potential changes among the same respondents surveyed two years apart.Footnote 9 We see that less than 1% of respondents (7 in total) changed from left (right) to right (left).

Figure 3. Ideology over Two Waves.

Source: Netquest panel. Number of unique observations: 1,065.

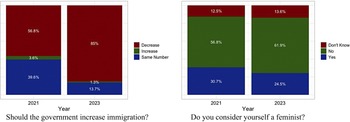

However, this stability is not mirrored when analyzing preferences over key issues, even considering the same people over time. The left panel of Figure 4 shows the percentage breakdown of what the government should do about immigration. We see a striking increase of about 30 percentage points among the people who want to decrease the number of immigrants in only two years. Regarding feminism, in the right-hand panel of Figure 4, we also see a five percentage point decrease among people identified as feminists.Footnote 10 The analysis of the panel data clearly shows a swing to conservative positions among key issues. However, this shift does not materialize in an increase in ideological identification with the Right.

Figure 4. Preferences over issues (Two Waves).

Source: Netquest panel. Number of unique observations: 1,065.

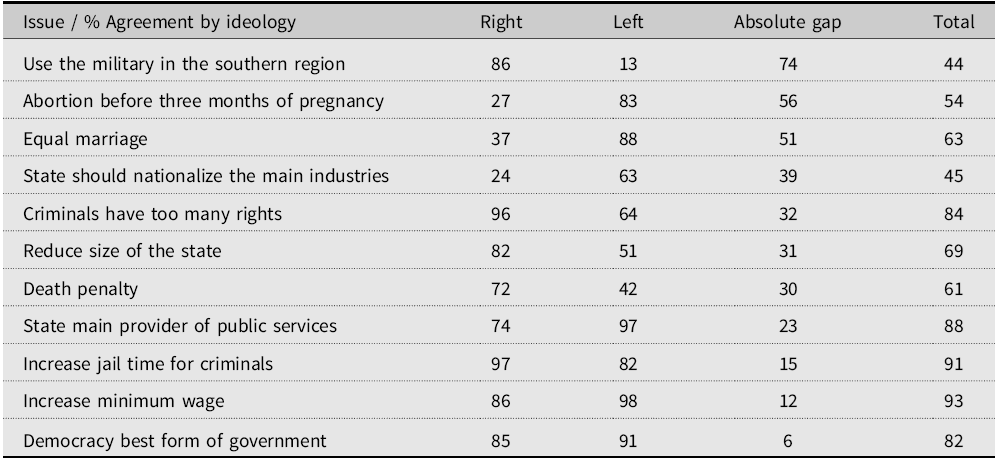

What does it mean to identify with the Right or the Left? Table 2 displays the percentage of agreement with a battery of issues, including topics related to law and order, the economy, the role of the state, and cultural issues. This descriptive analysis provides several insights. First, we see that two of the three topics with more disagreement across left and right belong to what has been called “cultural issues,” such as abortion and equal marriage. The other topic is the use of the military in dealing with a civil conflict in Chile’s southern region; not surprisingly, the Right firmly supports that policy, whereas the Left opposes it. Then, there is a level of disagreement over economic policies, nationalization of the main industries or the size of the state, although the disagreement is not as pronounced as we may have expected. For instance, more than half of left-wing people believe in reducing the size of the state and that criminals have too many rights. Finally, we see a virtual agreement in questions about the role of the state in the economy and views about democracy. Surprisingly, a large majority of right-wing respondents believe in increasing the minimum wage and with the notion that the state should be the primary provider of public services. The main takeaway from the analysis of ideology by issue is that there is no straightforward correspondence between ideology and issues. In fact, while there are gaps in cultural issues and the use of the military, the disagreement over topics related to law and order and the economy is not as pronounced as one might expect.

Table 2. Issue Agreement by Ideology

Source: Netquest panel. Number of unique observations: 3,075.

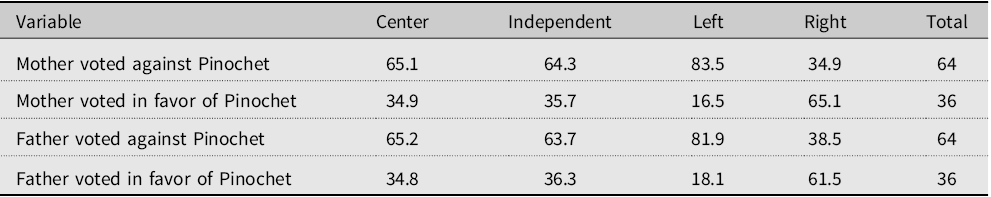

Let us now examine whether ideology is transmitted within the family. If ideology is a social identity, we should expect a strong correlation between respondents’ self-reported ideology and their parents’ ideology. In Table 3, we observe precisely that. For instance, among leftist people, more than 80% of both parents voted against Pinochet; among right-wing respondents, a majority (more than 60%) voted in favor of Pinochet.Footnote 11

Table 3. Ideology by Parents’ Vote in 1988 Referendum

Source: Netquest panel. Number of unique observations: 2142. There were 1823 who did not remember or did not know.

Finally, we can explore the degree of out-group animosity among people who identify with an ideology. When asking whether you would never vote for either the Left or the Right, we observe clear signals of animosity. Sixty-three percent of leftist would never vote for the Right, and 65% of rightists hold an analogous position. In this sense, despite the radicalism of such assertions, we see a clear majority of ideologues holding this position.

Experimental Evidence

Data and Research Design

In the first wave of the panel data described in the previous section, administered in 2021, we included a conjoint experiment,Footnote 12 which allowed us to explore the idea of ideology more in-depth.Footnote 13 Our rationale was the following: if ideology is the structuring force of electoral competition, and its meaning goes beyond preferences over issues, there are two observable implications. First, ideological alignment should matter more than issue alignment when voting for a candidate, as congruence in social identity must have higher weight than agreement over a single issue. Second, a better way to define ideology is to use self-identification on the left-right scale instead of a sum of preferences over policies. Accordingly, we designed our study to test these two propositions empirically.

Ideology vs. Issues

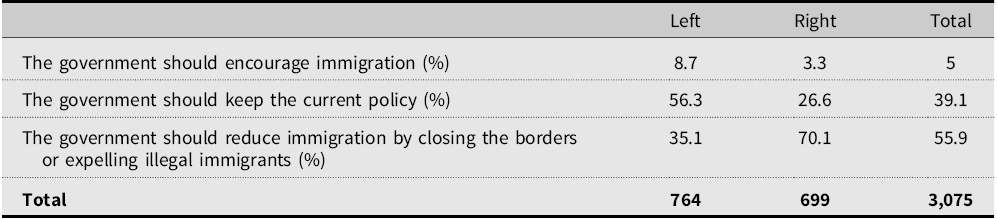

To test whether ideology matters more than specific issues, we first selected an issue with a clear difference between the Left and the Right, namely, immigration, whose phrasing was described in the previous section. When looking at the cross-tabulation by ideology (Table 4), we clearly see that decreasing immigration is typically associated with the Right, whereas maintaining the same policy is the option preferred by the Left.Footnote 14

Table 4. Attitudes Towards Immigration by Ideology

Note: The percentages displayed are the column percentages. We omitted centrists and respondents who do not identify with an ideology on the left-right scale, to provide a clearer contrast between left and right.

Then, we did the following exercise: we identified a subsample of respondents who are both right (left) and anti (pro) immigration.Footnote 15 In other words, we took the subset of people who identify with an ideology and with a preference for an issue.Footnote 16 For each of the described subgroups, we administered a conjoint experiment, presenting profiles of two hypothetical candidates for president of Chile. For each candidate, we simultaneously randomize six different attributes: 1) ideology (left or right); 2) gender (man or woman); 3) age (35, 45, 55, and 65 years old); 4) support for feminism (yes or no); 5) proposal about immigration (new restrictions, or no restrictions), and 6) proposal about crime (more punitive or less punitive). We repeated the experiment five times per respondent. Table A2 displays an example of two possible profiles.

As the reader may have realized, we included preferences over immigration policy to mimic the subsamples defined above; precisely, the point of this analysis is to determine whether people with an ideological identification and a preference over an issue would prioritize ideology or issue alignment when choosing a candidate. Importantly, for every issue in the conjoint experiment, we use two levels per attribute to help us compare ideological positions (e.g., left vs. right) and across preferences over issues sharply (e.g., pro or anti-immigration).

Among the subsamples, we estimated the marginal means, that is, the predicted value of a given attribute or combination of attributes. As the outcome is binary, the marginal mean takes values between 0 and 1.Footnote 17 The regression equation can be described as follows:

$${Y_i} = \;{\beta _0} + \beta Righ{t_i} + {\beta _2}Femal{e_i} + \;\mathop \sum \limits_{\left\{ {j = 1} \right\}}^{\left\{ 3 \right\}} {\tau _j}Age{\left( j \right)_i} + {\beta _3}Feminis{t_i} + {\beta _4}AntiIm{m_i} \; \; \;+ {\beta _5}Punitiv{e_i} + \varepsilon $$

$${Y_i} = \;{\beta _0} + \beta Righ{t_i} + {\beta _2}Femal{e_i} + \;\mathop \sum \limits_{\left\{ {j = 1} \right\}}^{\left\{ 3 \right\}} {\tau _j}Age{\left( j \right)_i} + {\beta _3}Feminis{t_i} + {\beta _4}AntiIm{m_i} \; \; \;+ {\beta _5}Punitiv{e_i} + \varepsilon $$

Where Y i represents a binary choice for respondent i. The coefficients of interest are β 1, the effect of being right-wing as opposed to left-wing, and β 4, the effect of being against immigration.Footnote 18 In addition, we interacted two attributes of the conjoint experiment ideology and immigration issue. This exercise aimed to analyze whether, for example, the effect of right-wing ideology was still prominent among pro-immigrant candidates. To this end, we estimate the following regression:

$${Y_i} = \;{\delta _o} + {\delta _1}Righ{t_i} + \;{\delta _2}Anti\;Im{m_i} + \;{\delta _3}{\left( {Right*Anti\;Imm} \right)_i} + \;{\delta _4}Femal{e_i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{\left\{ {j = 1} \right\}}^{\left\{ 3 \right\}} {\tau _j}Age{\left( j \right)_i} + {\delta _5}Feminis{t_i} + {\delta _6}Punitiv{e_i} + \varepsilon \;$$

$${Y_i} = \;{\delta _o} + {\delta _1}Righ{t_i} + \;{\delta _2}Anti\;Im{m_i} + \;{\delta _3}{\left( {Right*Anti\;Imm} \right)_i} + \;{\delta _4}Femal{e_i} + \mathop \sum \limits_{\left\{ {j = 1} \right\}}^{\left\{ 3 \right\}} {\tau _j}Age{\left( j \right)_i} + {\delta _5}Feminis{t_i} + {\delta _6}Punitiv{e_i} + \varepsilon \;$$

Here, the coefficients of interest are δ 1, δ 2, and δ 3, the latter representing the interaction term between both attributes.

In all models, we cluster the standard errors at the respondent level. It is important to discuss upfront how realistic it is to observe a misalignment between ideologies and issues—for example, a left-wing anti-immigration candidate. Given the proportional electoral system and the large number of parties in the Chilean context, it is credible to find such profiles. Indeed, several center-left politicians have taken a restrictive view towards immigration, including current president Boric, who has stated that illegal immigrants will be expelled from the country if they do not get legal status (Reyes Reference Reyes2022).

Is Ideology Just a Sum of Issues?

The second implication is that self-identification is more important than the sum of preferences over individual issues. Therefore, the correct definition of ideology should be self-identification instead of agreement with a set of issues that we may expect to align with either the Left or the Right. To test this proposition, we created an alternative definition of ideology by selecting preferences regarding five issues. Crucially, people must have consistent preferences over these topics in the direction that we may think corresponds with either left or right. Thus, we defined a right-wing person as follows: someone who agrees with 1) reducing the size of the state, 2) using the military to tackle political violence in Chile’s southern region, 3) criminals having too many rights, 4) reducing the number of immigrants, and 5) who disagrees with abortion in the first three months of a pregnancy. Regarding the Left, we defined a leftist person as follows: someone who agrees with 1) equal marriage, 2) increasing the minimum wage, 3) abortion, 4) that the state should own the main companies, and 5) that the state should be the main provider of health care and education.Footnote 19 Note that we did not use exactly the same issues for both left and right, as we sought to define them by issues that really matter to them.Footnote 20 After defining ideology in this way, we estimate the regression described before.

Results of Conjoint Experiment

Main Findings

Respondents in both subsamples consider ideology more important than the stance towards immigration. In the case of the Left and pro-immigration subgroups, Figure 5 displays the marginal mean of left-wing ideology and the immigration attribute. We see that the marginal mean of a candidate with a leftist ideology is 0.71 [CI: 0.67, 0.74]; in contrast, these respondents are practically indifferent regarding immigration. A similar trend is observed in the rightist subsample: the marginal mean of right-wing ideology is considerably higher than the one about new restrictions on immigration.

Figure 5. Marginal Means Ideology and Immigration.

Note: The outcome is the preference for a given candidate. The other conjoint attributes are omitted (see Appendix A for the complete results). Coefficients represent the marginal means. The dots represent the point estimates, and the lines 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors are clustered at the respondent level. Number of observations Left and pro-immigration subsample: 4,960 (496 survey participants). Number of observations Right and anti-immigration subsample: 4,900 (490 survey participants).

When looking at the interaction terms between immigration and ideology, a similar pattern emerges. Figure 6 shows that being a left-wing candidate is clearly more relevant than being pro- immigration for this subgroup. Indeed, the marginal mean of a leftist pro-immigration candidate is practically identical to the one of a left-wing anti-immigration candidate. Among the right-wing subsample, there is a clear preference for right-wing candidates who propose no restrictions to immigration (marginal mean: 0.54, 95% CI: [0.51, 0.58]), compared to leftist anti-immigrant (marginal mean: 0.34, 95% CI: [0.30, 0.38]). In practice, this means that these right-wing respondents are not willing to choose a left-wing candidate, even if they propose more restrictions on immigration (see Figures A5, A6, A7, and A8 for the average marginal component effect (AMCE) and the interacted AMCE for both subsamples).

Figure 6. Marginal Means Interaction between Ideology and Issues.

Note: The outcome is the preference for a given candidate. The other conjoint attributes are omitted (see Appendix A for the complete results). Coefficients represent the marginal means. The dots represent the point estimates, and the lines 95% confidence intervals. Standard errors are clustered at the respondent level. Number of observations Left and pro-immigration subsample: 4,960 (496 survey participants). Number of observations Right and anti-immigration subsample: 4,900 (490 survey participants). subsamples).

Now, we analyze the results when using an alternative definition of ideology. In Figure A11, we observe that for both left and right, the effect of ideology, defined as a summary of policy preferences, seems totally irrelevant. In fact, a left-wing pro-immigration person, defined this way, seems to be indifferent even between a leftist or a rightist candidate and between pro or anti-immigration candidates. The same applies to the case of the Right. In fact, the eight estimated marginal means are around 0.4. This finding suggests that ideological identification is not correctly captured by just eliciting preferences over a sum of issues. In other words, when asking a person about their ideology, what matters is the position they reveal because it signals their own identity.

Robustness Checks, External Validity and Conjoint Diagnostics

As robustness checks, we present two additional analyses: first, the role of ideology against two alternative issues, namely, crime and feminism; second, the relevance of ideological alignment versus a disagreement over two issues. Moreover, we present conjoint diagnostics and address potential external validity issues. In general, our results are consistent with the idea that ideology prevails. For more details, see Appendix B for robustness checks, Appendix C for external validity, and Appendix D for conjoint diagnostics.

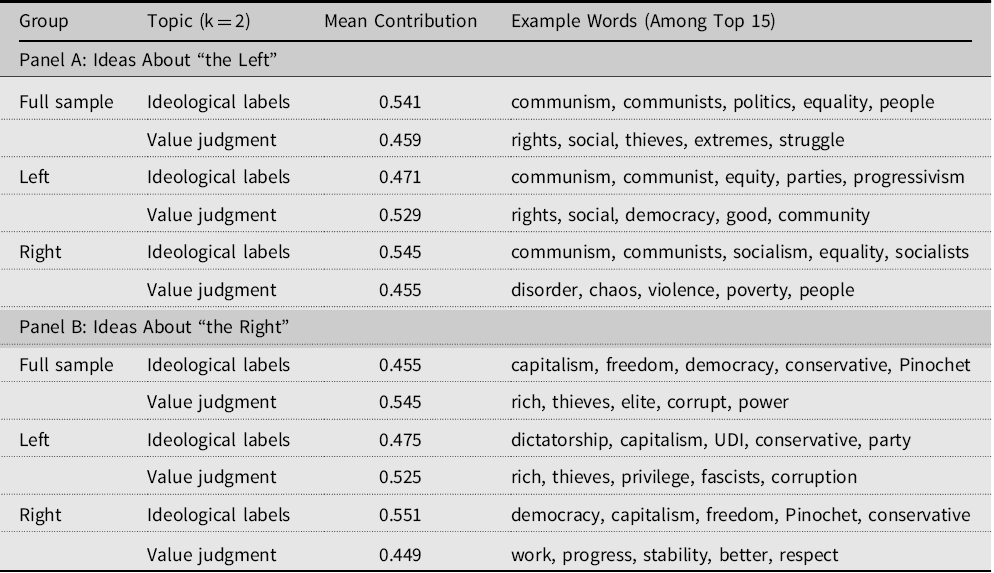

In-Group and Out-Group: Topic Modeling of Open-Ended Questions

In this section, our aim is to describe whether there is a moral or affective component of ideology. To this end, we asked respondents, in the first wave of the Netquest survey, what ideas came to their minds when thinking about “the Left” and “the Right.” To analyze the answers, we use topic modeling, a text analysis technique. This unsupervised machine learning method is appropriate for exploring collections of unstructured text, as it identifies clusters of co-occurring words—referred to as topics—without requiring prior assumptions about content. We use Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), which models each survey response as a combination of topics, and each topic as a distribution of words. This method enables a systematic examination of what comes to people’s minds when thinking about ideological labels.

The key advantage of this approach is that the researcher does not determine ex-ante which topics emerge from the text (Catalina 2016). Instead, the researcher selects the number of topics (k) to estimate and then interprets their substantive meaning by examining the most frequent words within each topic. In practice, scholars typically begin with a given number of topics, inspect the results, and adjust the specification based on interpretability and thematic coherence (Grimmer Reference Grimmer2010). The intuition is that more topics enable one to “zoom-in” on narrower themes (Catalinac Reference Catalinac2016), while fewer topics yield broader, more aggregated themes. Following this logic, we began by estimating a model with four topics, given the relatively short length of the open-ended responses in our dataset. However, we subsequently reduced the model to two topics after observing considerable overlap—only two emerged as substantively distinct and interpretable.Footnote 21 We estimate topic models separately for all respondents and for subgroups who identify as left-leaning or right-leaning. This disaggregated approach allows us to compare how each ideological camp characterizes itself and its opponents, shedding light on affective polarization and identity-based framing.

For each document—in this case, an individual open-ended response—the topic model estimates the mean contribution of each topic. This is the proportion of the document that is associated with a given topic. In other words, the model produces a distribution of topics for every response. A higher mean contribution indicates that a particular topic dominates the response’s content. Aggregating these probabilities across documents allows us to assess the overall prevalence of each topic within a subgroup or the entire sample.

Table 5 presents the results of this analysis. Across all subgroups, two dominant topics consistently emerge when respondents reflect on either “the Left” or “the Right.” The first is labeled “Ideological labels,” as it captures the ideological terms and categories people associate with political identities. The second, “Value judgment,” reflects moral language—positive or negative—attached to those identities. Strikingly, the mean contribution of each topic is consistently around 50% in all groups, indicating that both dimensions are nearly equally salient in how individuals think about political ideologies.

Table 5. Topic Prevalence and Representative Words for Open-Ended Questions on Ideological Labels

In the top panel, which reports associations with “the Left,” we observe that both left- and right-leaning respondents emphasize the same ideological keywords in the “Ideological labels” topic; terms such as “communism,” “communists,” and “socialists” dominate. However, the “Value judgment” topic reveals sharp affective differences. Left-leaning respondents tend to use positive language to describe their own group, invoking words like “good,” “rights,” and “community.” In contrast, right-leaning respondents characterize the Left using negative moral terms such as “thieves,” “chaos,” and “violence.”

The bottom panel, which focuses on perceptions of “the Right,” reveals a similar structure. Both ideological camps invoke common ideological markers such as “capitalism” and “conservative.” However, their value judgments diverge substantially. Left-wing respondents use highly critical terms such as “thieves,” “corrupt,” and “rich,” whereas right-leaning respondents emphasize more affirmative values, using words like “progress,” “respect,” and “stability.”

To further strengthen the link between our findings and the social identity literature, we emphasize that the value-laden language observed in our topic modeling is evident when people refer to the ideological in-group using words widely recognized as markers of affective attachment, such as “good,” “community,” and “respect.” These serve as evidence of in-group affect. In addition, this pattern reveals the presence of symbolic boundaries that define who belongs to the in-group and who is excluded. These boundaries are visible in the ways respondents use shared ideological labels, draw on historically grounded references (e.g., Pinochet, communism), and deploy contrasting moral judgments to differentiate “us” from “them.” The consistent pattern in which individuals describe their ideological in-group using morally affirmative language, while applying negative moral descriptors to the out-group, aligns closely with established indicators of identity-based partisanship and ideological sorting (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012).

Taken together, these findings suggest that both ideological labels and moral evaluations are central to how citizens understand the political spectrum. Yet beyond doctrinal content, ideological identity is deeply affective: it reflects not only how people think, but also how they feel, particularly toward their political in-group and out-group.

The 1988 Plebiscite and Voters’ Ideological Identification

So far, we have shown that ideology matters and that there is a social and moral component attached to it. The next step is to better understand the origin of ideological identification in the last decades. Importantly, finding an effect of voting in the plebiscite does not undermine previous evidence on the socialization process of ideology. People’s ideology can be influenced by both their parents’ ideology and salient events.

As we previewed in the context section, the 1988 plebiscite in Chile was crucial in the country’s history. It marked a turning point regarding the rule of General Augusto Pinochet and the dictator- ship that started in 1973. The plebiscite was held on October 5, 1988, and it asked Chilean voters whether they approved of extending Pinochet’s presidency for another eight-year term. People could vote YES to express support for extending Pinochet’s rule or NO to end his regime and begin the transition to democracy (Boas Reference Boas2015). Eligibility to participate in this plebiscite could have been key in defining people’s ideological attitudes. Even though participants and non-participants were both exposed to the campaign, the former could have experienced this process differently, as they had a say in the first free and fair election in decades. Consequently, we exploit the fact that some voters born in 1970 were either eligible or ineligible to vote in the October 5, 1988, plebiscite by just a few days. Citizens needed to be 18 years old on the day of the election to be able to participate. Therefore, eligibility to vote was determined by the day of birth, creating a discrete threshold.Footnote 22 Therefore, we compare people who were 17 at the time of the plebiscite (control) against those who were barely 18 (treatment).

We use the CEP survey data, from 1995 to 2017, to estimate a regression discontinuity design in time (RDiT), where days until the plebiscite is the running variable, and treatment is a dichotomous variable equal to one when respondents are eligible to vote, zero otherwise (Hausman and Rapson Reference Hausman and Rapson2018; Carreras et al. Reference Carreras, Visconti and Acácio2021). We grouped the survey years into four periods, roughly coincidental with presidential mandates, in order to address whether the passage of time affects the results: (i) 1996-2005, (ii) 1996-2009, (iii) 1996-2013, and (iv) 1996-2017.

As explained above, eligibility to vote is the treatment (i.e., born before October 5th, 1970), and days after and before eligibility to vote is the running variable, which can take positive and negative values. For example, −1 means that the respondent was born on October 6, 1970, implying that s/he was not eligible to vote by one day. The outcome of interest is to express any ideological identification (1: any values between 1 and 10 in the ideological spectrum, 0: none). We estimate the following local-linear regression discontinuity specification:

Where the outcome of interest δ, of individual λ, surveyed in wave δ, is regressed on days until the plebiscite, being eligible to vote ((Eleg)) and the interaction between the two, which allows for varying slopes at both sides of the threshold. δ accounts for survey and λ for municipality fixed effects. The parameter of interest is β 2, the effect of being eligible to vote on ideological identification at the cutoff. Also, we weighted the observations using a triangular kernel, assigning importance to respondents closer to the cutoff, and we rely on the MSE optimal bandwidth (Cattaneo and Titiunik Reference Cattaneo and Titiunik2022). Standard errors are clustered at the municipality level. We restrict the analysis to people with birthdays +/- 150 days from October 5th, 1970, to generate a reasonable bandwidth and conduct a sensitivity test in Appendix H. In Appendix G, we conduct a continuity test using two placebo pre-treatment covariates: gender and education (i.e., subjects’ characteristics that should been affected by being above or below the cutoff). The assumption is that we should observe a smooth transition at the cutoff, and that expectation is confirmed by obtaining null results when using both covariates as the outcomes.

Figure 7 provides the RD estimates for the four above-mentioned periods. We consistently observe that being eligible to vote in the 1988 plebiscite significantly increases the probability of identifying with any ideology. In the first 16 years of democracy (until 2006), the average effect of the plebiscite was an increase in reporting an ideology of 50 percentage points (95% CI: [42, 60], MSE bandwidth: 39 days).Footnote 23 Meanwhile, when expanding the analysis to the first 28 years of democracy (until 2017), the average effect of the plebiscite decreases, reaching 33 percentage points (95% CI: [7, 59], MSE bandwidth: 34 days). Therefore, even though the effect of the plebiscite has diminished its impact, it has long-term effects. In this sense, we confirm that highly salient political events make people more conscious of their political positions, generating long-lasting ideologies. These findings align with previous results showing that ideology is relevant in explaining how people understand and evaluate reparation and political forgiveness after the dictatorship in Chile (González et al. Reference González, Manzi and Noor2013; Balcells et al. Reference Balcells, Palanza and Voytas2022). However, it is important to notice that RDDs estimate a local average treatment effect, meaning that the results are strictly valid only for units near the cutoff. Therefore, we must be cautious when assuming that the same effect holds for individuals further away.

Figure 7. RD Estimates: Effect of Eligibility to Vote in the 1988 plebiscite on Ideological Identification.

Although the 1988 plebiscite has lost some of its influence as a driver of people’s ideological attitudes, recent events in Chilean politics, such as the 2019 Social Outburst and the 2022 Constitutional Plebiscite, have heightened polarization and contributed to the re-politicization of voters (Cox et al. Reference Cox, González and Le Foulon2024; Saldaña et al. Reference Saldaña, Orchard, Rivera and Bustamante-Pavez2024).Footnote 24 As a result, there are strong reasons to expect the persistence of ideology in the coming years in Chile, even as we move further away from the end of the Pinochet dictatorship.Footnote 25

Discussion

To clarify our conceptual stance, we do not claim that ideological identification in Chile fully satisfies all the definitional conditions of a politicized social identity. Instead, we argue that it exhibits features consistent with identity-based attachments. These include durable commitments to ideological markers over time, intergenerational transmission, and moral and symbolic framing of ideological camps. These dimensions align with key elements of social identity theory, such as affective attachment, in-group favoritism, and the perception of ideological affiliations as central to self-conception and group-based differentiation. While these patterns may fall short of a full- fledged social identity in the strictest theoretical sense, they nonetheless suggest that ideology in Chile functions as more than a mere bundle of issue preferences.

In addition, we want to directly address three plausible counterarguments to our claim that ideology, as a stabilizing force for electoral politics, is a social identity.

For some readers, our argument may imply that ideological preferences are static. Although we claim ideology is stable over time, we do believe that specific events could detonate a realignment. In fact, as we demonstrated before, the 1988 plebiscite was a key issue in realigning preferences in a dichotomous way, where the centrist Democracia Cristiana coalesced with the Left, which is at odds with the party’s historical position. More recently, we may consider the constitutional plebiscite of 2022, which happened as a by-product of the 2019 social outburst, as a new moment of realignment, as centrist voters decided to favor the position of right-wing parties. In this sense, there are critical junctures that may move the ideological needle, although not as fast as, for instance, preferences over specific policies.

Other readers may argue that “negative partisanship,” that is, that people vote primarily to prevent the party they dislike from gaining power (Samuels and Zucco Reference Samuels and Zucco2018), is a better explanation for the observed findings. A growing body of research on political identities in Chile and Latin America emphasizes the role of negative partisan attachments—such as anti-Pinochetismo and anti-comunismo—in shaping long-term political behavior (Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser2019; Meléndez Reference Meléndez2022; Cavieres et al. Reference Cavieres, Guzmán-Castillo and Meléndez2025). These antagonistic identities have helped structure the political landscape by clearly demarcating symbolic boundaries between opposing camps, even in contexts of partisan dealignment. In Chile, such identities provided a durable basis for ideological alignment during and after the transition to democracy, particularly by crystallizing the divide between authoritarianism and democratic forces. This pattern reinforces the view that ideological attachments can persist even when they are no longer tightly anchored to party structures or consistent policy preferences.

While the concept of negative identities offers valuable insights, its explanatory scope may be more limited in certain contexts. These attachments are historically contingent, rooted in specific political moments, and may lose salience over time. While that plebiscite served as a critical juncture that aligned political identities along a democracy/authoritarian cleavage, our evidence suggests that its influence weakens with generational replacement. What emerges in its place are social dynamics and in-group narratives that sustain ideological identification in the absence of strong party linkages.

While out-group rejection remains part of the story, in-group cohesion also plays a central role. The emotional and symbolic dimensions of ideology—such as moralized perceptions of “left” and “right,” intergenerational transmission, and consistency in candidate preference—point to its function as a social identity rather than merely a collection of policy positions or reactive sentiments. Taken together, these perspectives are not mutually exclusive but complementary. Negative political identities help explain the origins and persistence of ideological divisions in post-authoritarian contexts.

Another potential criticism is that ideology signals preferences across a bundle of issues. For instance, Orr et al. (Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023) argue that in the United States, partisanship serves as such a signal, thereby weakening the notion of partisan loyalty. We present several pieces of evidence to refute that point. First, we define ideology as a set of preferences over issues in Figures A11, finding that under such definition, ideological alignment is irrelevant. Second, we test the importance of ideology against two issues (Figure B3), generally finding support for our hypotheses. Third, we find that ideology prevails even in issues where respondents are ideologically inconsistent (see Appendix E).

It is also essential to consider whether these findings generalize to other Latin American countries. On the one hand, the decline of partisanship in the region has been a persistent trend, largely driven by political disillusionment, economic instability, and the rise of outsider candidates. Traditional party systems—once anchored in strong ideological and organizational structures—have weakened due to corruption scandals, policy failures, and increasing voter volatility (Lupu Reference Lupu2016; Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2018). Yet ideology has remained a central organizing force in countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador, and Colombia. Indeed, while partisan attachments have eroded, the left-right spectrum continues to serve as a critical heuristic for voters, shaping their perceptions of candidates and political parties (Wiesehomeier and Doyle Reference Wiesehomeier and Doyle2012; Zechmeister and Corral Reference Zechmeister and Corral2012; Saiegh Reference Saiegh2015). The enduring relevance of ideology thus suggests that, even amid declining party loyalty, ideological commitments remain a powerful force.Footnote 26

Conclusion

In this article, we provided evidence supporting, at least partially, the following six assertions: 1) Ideological identification has been mostly stable in Chile in the past 30 years, contrary to party identification. 2) People can rapidly change their preferences over issues but not their ideological positioning. 3) Ideology is transmitted through the family. 4) Ideological alignment is much more relevant than issue alignment when voters make electoral decisions. 5) There is both in-group favoritism and out-group animosity among ideologues. 6) Ideological identification substantively increases in highly intense political events. We claim that a plausible interpretation of these results is to consider ideology as a social identity. For the literature of political behavior, these findings imply that ideological labels can work as a “social identity cue” for votersReference Green, Palmquist and Schickler, and as a result, be of extraordinary power when predicting people’s electoral choices.

We also contribute to long-lasting debates on Latin American politics. Most of the literature explaining Chile’s relative political stability compared to other Latin American countries highlights the role of parties and the high levels of institutionalization. Therefore, having old, national, and well-organized parties has been used to explain stable electoral competition (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring1999). Previous research has highlighted the relevance of rules and institutions as a key factor explaining stability and economic success (Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995). Instead, we argue that stability can persist even when parties are weak, provided that an identity, such as ideology, serves as a stabilizing force in electoral competition.

It is important to emphasize that we analyze approximately half of the sample, namely, either left- or right-wing voters. In this sense, our argument applies mainly to this subset of the electorate. Thus, an obvious question remains: what about the other half of respondents, those who either identify as centrists or do not have an ideology? A fraction could be considered latent ideological voters, mimicking the electoral behavior of the explicitly ideological voters (Visconti Reference Visconti2021). Others may guide their electoral decisions by anti-establishment sentiments, therefore choosing independent candidates (Argote and Visconti Reference Argote and Visconti2023; Titelman and Sajuria Reference Titelman and Sajuria2023). Finally, there could be a third group that might be considered “innocent of ideology,” that is, without a clear grasp of the basic meaning of left and right. This latter group is, most likely, less politicized and unwilling to vote. Thus, they would need to coordinate behind a non-ideological candidate to introduce instability and unpredictability into electoral competition, an unlikely scenario for a group that is less engaged in politics. Note that in the United States, about half of voters identified as either Democrats or Republicans, and the literature on polarization focuses heavily on them. It is not unusual, therefore, to study a large section of the electorate rather than the electorate as a whole.

Future research could illuminate the role of ideology on moderate or centrist voters. We excluded this group from the main analysis to be able to make direct comparisons between different ideologies and issues. However, subsequent studies could zoom-in on these subgroups of voters to better understand their decision-making process. For instance, an interesting research question is whether centrist voters are as ideological as, say, left-wing ones, or instead, their centrism equals pragmatism.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2025.10028

Data availability statement

Data and code are available at Harvard Dataverse.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matias Bargsted, Ewon Baik, Rodrigo Castro Cornejo, Loreto Cox, Maria Victoria Murillo, Eric Plutzer, Javier Sajuria, Robert Shapiro, Noam Titelman, ACCP 2023, MPSA 2024, Seminario Interdisciplinario en Comportamiento Político y Opinión Pública, and the University of Southern California Center for International Studies seminar participants for their comments and suggestions. Authors acknowledge funding from the Center for International Studies of the University of Southern California, and the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development by the Millennium Nucleus Center for the Study of Politics, Public Opinion, and Media in Chile, MEPOP (grant number NCS2024_007) This study was preregistered at Open Science Framework before finishing data collection and having access to the final dataset. All errors are our own.

Competing interests

Pablo Argote and Giancarlo Visconti declare none.