This article reports on a one-of-a-kind patolli board found in Residential Complex 6L13 of the Classic period Maya capital Naachtun, northern Petén. It introduces how this find may enhance our understanding of the practice of gaming among the Maya. Here we present only the primary data, acknowledging that additional excavations will be needed to enable full interpretation of the board.

The word patolli, sensu stricto, refers to a Postclassic Central Mexican board game described in ethnohistorical accounts, depicted in many Postclassic codices and sometimes found archaeologically (Durán Reference Durán1971; Gallegos Gómora Reference Gallegos Gómora1994; Swezey and Bittman Reference Swezey and Bittman1983; Źrałka Reference Źrałka2014). However, the word has become widely accepted as a general term for all Mesoamerican board games (Acosta Reference Acosta1961:43; Swezey and Bittman Reference Swezey and Bittman1983:412–413; Verbeek Reference Verbeeck1998:82; Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:200), including those that have no spatial, temporal, or cultural connection to Central Mexico or the aforementioned specific game. In the following discussion, we use the word patolli in this general sense of a Mesoamerican board game, without implying any further meaning.

In the Maya region, dozens of game boards have been found, almost exclusively in the Lowlands, primarily within palaces and temples located at site epicenters (Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:210). In nearly all instances, these game boards were incised into plaster benches and floors (Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:201). Although several variants of patolli boards exist in Mesoamerica, in the Maya region, the most common design features a circuit of squares arranged in the form of a cross enclosed within a rectangular frame. In the past five years, structures containing groups of boards have been identified in Belize, at Xunantunich (Fitzmaurice et al. Reference Fitzmaurice, Watkins and Awe2021) and Gallon Jug (Novotny and Houk Reference Novotny and Houk2021), and in the state of Campeche, Mexico (INAH 2024), suggesting that people might have gathered in specific structures reserved for the practice of one or more types of board games. Although the cosmographic and esoteric aspects of patolli are often stressed—together with their role in divination and, maybe, communication with the world of the dead (Fitzmaurice et al. Reference Fitzmaurice, Watkins and Awe2021:65, 72; Johnson and Johnson Reference Johnson and Johnson2021:53)—in many cases, the boards were probably also used for entertainment (Fitzmaurice et al. Reference Fitzmaurice, Watkins and Awe2021:74). This is not without importance: common engagement in games could strengthen the sense of community (Novotny and Houk Reference Novotny and Houk2021:8). For a more mundane and practical interpretation, see Euan Canul et alia (Reference Euan Canul, Martín, Ramos, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2005), who consider that some incised boards at Chichen Itza could be the work of bored guards watching over the entrance of the group of the Initial Series. None of this, of course, is in complete contradiction with the probable cosmographic symbolism of the board and the game nor with its possible use in ritual; indeed, this polysemy of the game has been noted repeatedly (Fitzmaurice et al. Reference Fitzmaurice, Watkins and Awe2021; Walden and Voorhies, Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:198, 201). In fact, many questions remain concerning who could play patolli, and in which context, because of the mode of creation of the boards. Despite the growing number of examples, the way the Maya created them—that is, by incising plaster floors—still proves a challenge when it comes to dating and interpreting the games, as in most cases, only a terminus post quem can be established, with no direct association between the game and the structure’s original function or date of construction.

Context of the Naachtun Patolli Board

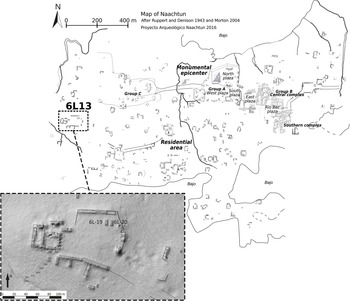

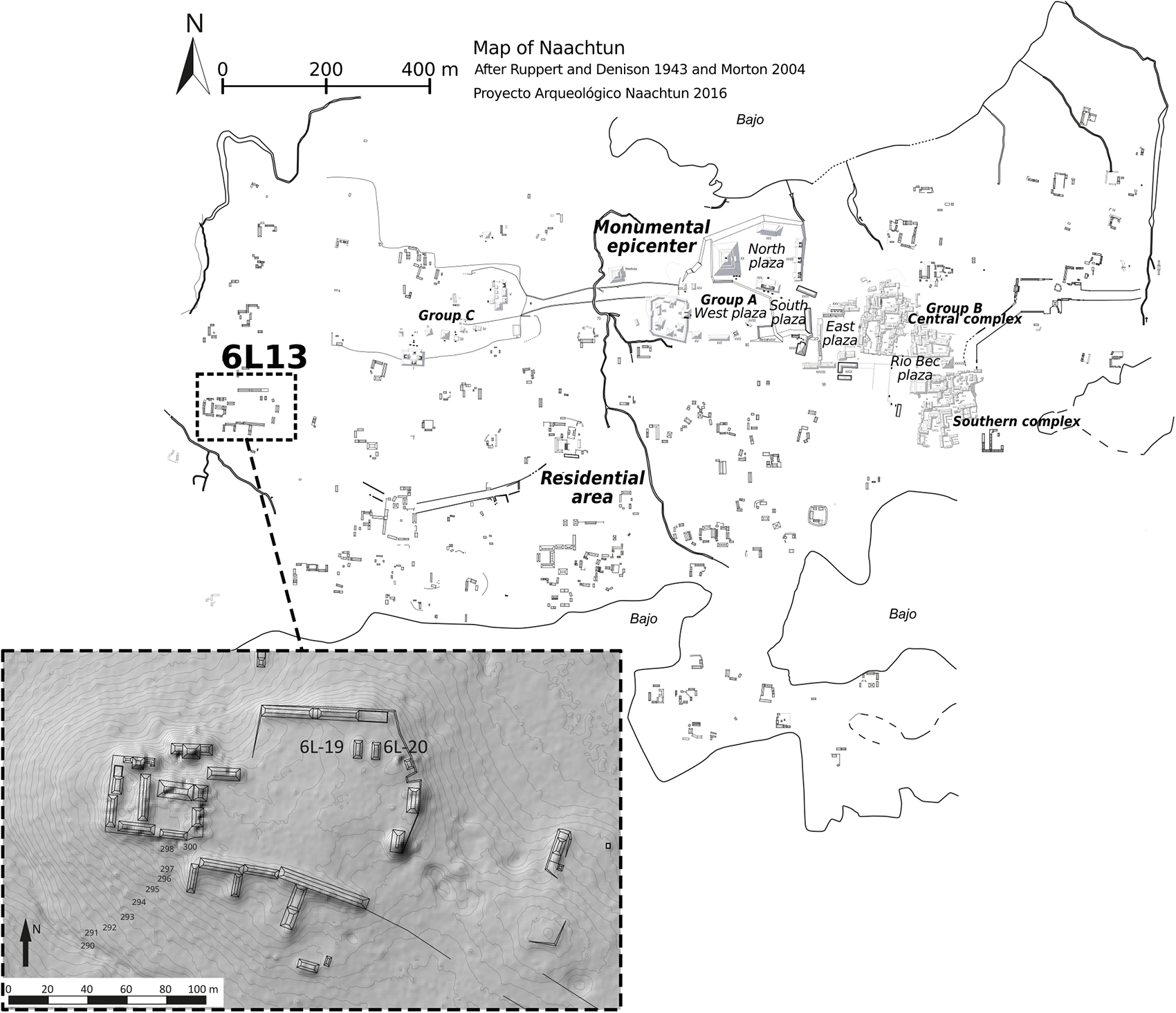

Located in northern Petén, Guatemala, Naachtun is a large, Classic period regional capital lying between Tikal and Calakmul (Figure 1). It was reported by scientists in the 1920s and mapped by the Carnegie Institution in the 1930s (Ruppert and Denison Reference Ruppert and Denison1943), but excavations started only in 2004, with a two-season project led by universities of Calgary, Canada, and San Carlos, Guatemala (Walker and Reese-Taylor Reference Walker and Reese-Taylor2012). Since 2010, the Proyecto Petén-Norte Naachtun (CNRS, France, University of Paris 1 and University of San Carlos) has conducted yearly excavations under the direction of Philippe Nondédéo. Current knowledge indicates that the site was a dispersed hamlet during the Preclassic period and that at the beginning of the Early Classic period, Naachtun experienced a sudden growth and the establishment of the Suutz’ dynasty, responsible for the creation of more than 70 monuments during the Classic period (Hiquet et al. Reference Hiquet, Castanet, Dussol, Nondédéo, Testé, Purdue, Tomadini, Grouard, Dorison, Brysbaert, Vikatou and Pakkanen2022, Reference Hellmuth2023; Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, Lacadena, Garay, Kettunen, López, Kupprat, Lorenzo, Cosme and de León2018). The city played an active part in the geopolitics of the Classic period (such as the AD 378 Teotihuacan “Entrada” or the conflicts between Tikal and the Snake state). Although its dynasty collapsed at the end of the Classic period, it continued to be occupied into the Terminal Classic, and there is evidence for sporadic Early Postclassic activity (Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, Sion, Lacadena, Cases, Hiquet, Okoshi, Chase, Nondédéo and Arnauld2021).

Figure 1. Map of the Maya sites mentioned in the text.

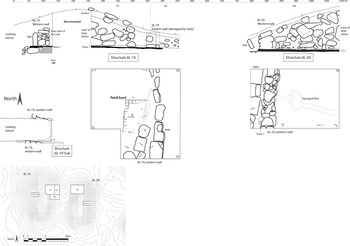

Group 6L13 is one of the largest complexes in Naachtun’s residential area (Figure 2). Lying 250 m west of epicenter Group C, the site’s Early Classic dynastic ritual seat, it has characteristics of both public and private, residential functions. These characteristics lead us to suggest it was the seat of a powerful household, maybe housing the head of the neighborhood and possibly having administrative or fiscal functions. Eleven test pits have been excavated over the entire group, mainly to establish its chronology (Hiquet et al. Reference Hiquet, González, Cano, Nondédéo, Hiquet, Michelet, Sion and Garrido2014, Reference Hiquet, Schwendener, Sotz, Nondédéo, Michelet, Hiquet and Garrido2016; Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, Guzmán, Hiquet, Nondédéo, Begel and Cotom-Nimatuj2024). Group 6L13 had a long occupational sequence, spanning the Late Preclassic to the Terminal Classic. There are indications that its inhabitants held a wealthy or powerful position within local society until the Terminal Classic period, as evidenced by the architecture (most structures were vaulted, and some mounds, probably oratories, are 4 m high), spatial organization (including a large plaza, and probable palatial structures to the west of the compound), material culture, and funerary data. This prosperity may explain the interest of modern looters, as evidenced by a total of 64 looting trenches across the group’s 24 structures. During the Early Classic period, Group 6L13 yielded more Teotihuacan-related artifacts than any other residential compound at Naachtun, including not only five intact tripod cylinder vessels recovered from looted tombs but, more significantly, a large quantity of green obsidian and fragments of at least three Thin Orange vessels. At the beginning of the Late Classic period, Group 6L13 underwent a remarkable period of growth around a large plaza. In the northeast corner of this plaza lie a pair of medium-sized, parallel-sided structures: 6L-19 to the west and 6L-20 to the east. Both mounds are approximately 7.5 m long, 3.5 m wide, and 1.5 m high. The aim of the 2023 excavations was to determine whether they formed a ballcourt. An east–west trench was excavated, taking in the northern half of both mounds (Figure 3). The trench yielded no definitive evidence for the function of these structures, but the patolli board was found inlaid into the superior floor (Floor 1) under Structure 6L-19, partially covered by the east wall of the structure. Before we describe the board in detail, we examine the stratigraphy revealed by excavations to highlight its archaeological context.

Figure 2. Maps of Naachtun with inset of Group 6L13.

Figure 3. Plan and cross section of the excavations in Structures 6L-19 and 6L-20, with inset of the localization of the excavations.

Structures 6L-19 and 6L-20 were both damaged by looters. The looter tunnels were cleaned and described in 2015 by Estrada (Reference Estrada, Nondédéo, Michelet, Hiquet and Garrido2016), and the one affecting the western side of 6L-19 was reopened in 2023 by Hiquet (Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, Guzmán, Hiquet, Nondédéo, Begel and Cotom-Nimatuj2024) to contextualize the data yielded by that year’s excavation, including establishing the depth of the floor in the tunnel versus that in the test pit. This tunnel shows that an earlier version of Structure 6L-19 existed (6L-19Sub) under Floor 1 (the floor into which the patolli board was inlaid and on top of which Structure 6L-19 was built). In the looter tunnel, one can observe the probable northern wall of that sub, oriented east–west. Two elements help in clarifying the construction sequence of 6L-19: (1) the footprints of the two versions of 6L-19 partially overlap; that is, the footprint of 6L-19Sub is not completely subsumed in the perimeter of 6L-19; and (2) Floor 1 completely covers 6L-19Sub; that is, Floor 1 is not an addition abutting onto the wall of 6L-19Sub but instead seals its remains. 6L-20 also had at least one sub, which appears to have been constructed mainly of perishable materials (Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, Guzmán, Hiquet, Nondédéo, Begel and Cotom-Nimatuj2024:301–302). Only a line of small stones was found, along with a posthole (Figure 4).

Figure 4. View of Structure 6L-20 Sub, from the south.

Floor 1 was thus laid over 6L-19Sub. At present, no feature apart from the patolli board has been found to be directly associated with this floor. Unless evidence of a perishable structure—such as postholes—emerges, it is possible that the board was left exposed on an exterior surface for some time, which may account for the original method of its creation, because it is outlined by small sherds set into the plaster.

Sometime after the construction of Floor 1 and its mosaic patolli board, the perimeter wall of 6L-19 was built, with a southwest–northeast orientation. This wall partially covered the board, leaving the remaining portion protruding to the west (Figure 3). The wall is thin and roughly constructed, consisting of heterogeneous blocks. It has an average width of around 40 cm and a maximum preserved height of 60 cm. On the west and east sides of the structure, the exterior base of the wall was bordered by a row of slabs laid on their edge, which had been more finely worked than the rest of the wall. All the slabs of the eastern wall were found leaning toward the space between 6L-19 and 6L-20. The interior space of Structure 6L-19 measures 3.1 m in width. Excavations within this space revealed a dense concentration of intermingled stones, some the size of vault slabs—one even featuring a beveled edge—forming a layer approximately 1 m thick. At the bottom of this layer, the stones tend to lie horizontally, while higher up in the layer, the stones lie at an incline. Excavations of mound 6L-20 showed the same characteristics of the walls and their inner fill. The matrix between the stones contained what appeared to be disaggregated lime mortar, which may indicate that they constitute the collapsed debris of a wall dating to the Late Classic period, based on ceramics recovered from this layer. At first glance—and considering the volume of stones—they may appear to represent the collapsed remains of vaulted structures. Yet the dimensions observed for room 6L-19 are incompatible with a vaulted room. Gilabert Sansalvador (Reference Gilabert Sansalvador2018:201) proposed the “luz coefficient” (λ) (referring to the Spanish term for the width of a vault at its widest point) to quantify the characteristics of vaulted rooms. The coefficient relates the width of the walls to the width of the room. Applying this coefficient to 6L-19, we obtain a result of 0.129 (0.4/3.1), which is even lower than the extreme (0.16) found by Gilabert Sansalvador for the finest vaulted rooms of the Puuc and Chenes architectural traditions. Given that, in addition, the construction quality of 6L-19 is poor, it is highly unlikely that it was a vaulted room. More plausibly, the final phase of 6L-19 consisted of a 3.1 m wide room with masonry walls and a presumed perishable roof, incorporating reused vault slabs from another structure in the construction of the perimeter wall.

A Unique Patolli Board: Construction Technique, Dimensions, and Material Selection

The Naachtun 6L-19 patolli board is unique in that its squares are outlined with small ceramic sherds inlaid into fresh plaster, resembling a floor mosaic (Figures 5 and 6). The 1 to 3 cm tesserae form a rectangular layout, subdivided into squares and roughly aligned with the cardinal directions. Due to architectural activities postdating its creation, the board was significantly damaged. We note that some of the sherds were removed during the excavation of the layer directly above the floor, before we came upon the board. Because it was soon remarked that all the sherds the excavators were getting from that centimeter-thin layer had a uniform color, shape, and size, they were set aside for ceramic analysis. Some tesserae remain embedded in the plaster; others, displaced by small roots that damaged the floor, remain roughly aligned in their original positions; still others have disappeared. Fortunately, in some cases in which the tesserae are no longer in situ, their imprints remain preserved in the floor. Because most of these imprints have distinct, well-defined edges, it should be possible to reposition some of the isolated sherds during a conservation campaign.

Figure 5. View of the patolli board in Structure 6L-19. (Color online)

Figure 6. Drawing of the patolli board in Structure 6L-19. (Color online)

The board consists of a rectangular frame with a central cross. This is the most common form of patolli board in Mesoamerica, particularly among the Maya (Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:202), labeled Type II in Swezey and Bittman’s seminal typology (Reference Swezey and Bittman1983). As nearly half of the board is missing, it is difficult to establish the exact number of squares and original dimensions of the board. The west and north sides are the best preserved, the west side being the only side with full evidence of the number of squares. It had 11 squares, with the central cross acting as a bisector starting either side of the sixth, central, box (Figures 5 and 6). The north side may have had seven squares, although it is difficult to be certain because of the damage suffered by the east part of the board. When we count from the (complete) northwest corner, we see that there is good evidence that on the north side the central cross started from either side of the fifth, rather than the sixth, box. According to this reconstruction, the north and south sides (approximately 78 cm long, with approximately seven squares) did not have the same number of squares, and dimensions, as the west and east sides (110 cm long, with 11 squares). Assuming the north and south sides had seven squares, then including the central cross, the board would have had 45 squares. A large, empty imprint (possibly an additional marker or decoration) was found to the north, outside the board. The suggested pattern of the board is consistent not only with the placement of the remaining tesserae but also with the well-preserved area of stucco with no imprints present between the frame and the central cross. This indicates, for example, that unlike in some of the excavated examples at Gallon Jug (Novotny and Houk Reference Novotny and Houk2021), no inner circle existed. It is impossible, however, to exclude the possibility that the board was square, with 11 squares per side, or had a more complex design, which has become unrecognizable by the damage caused by later activities.

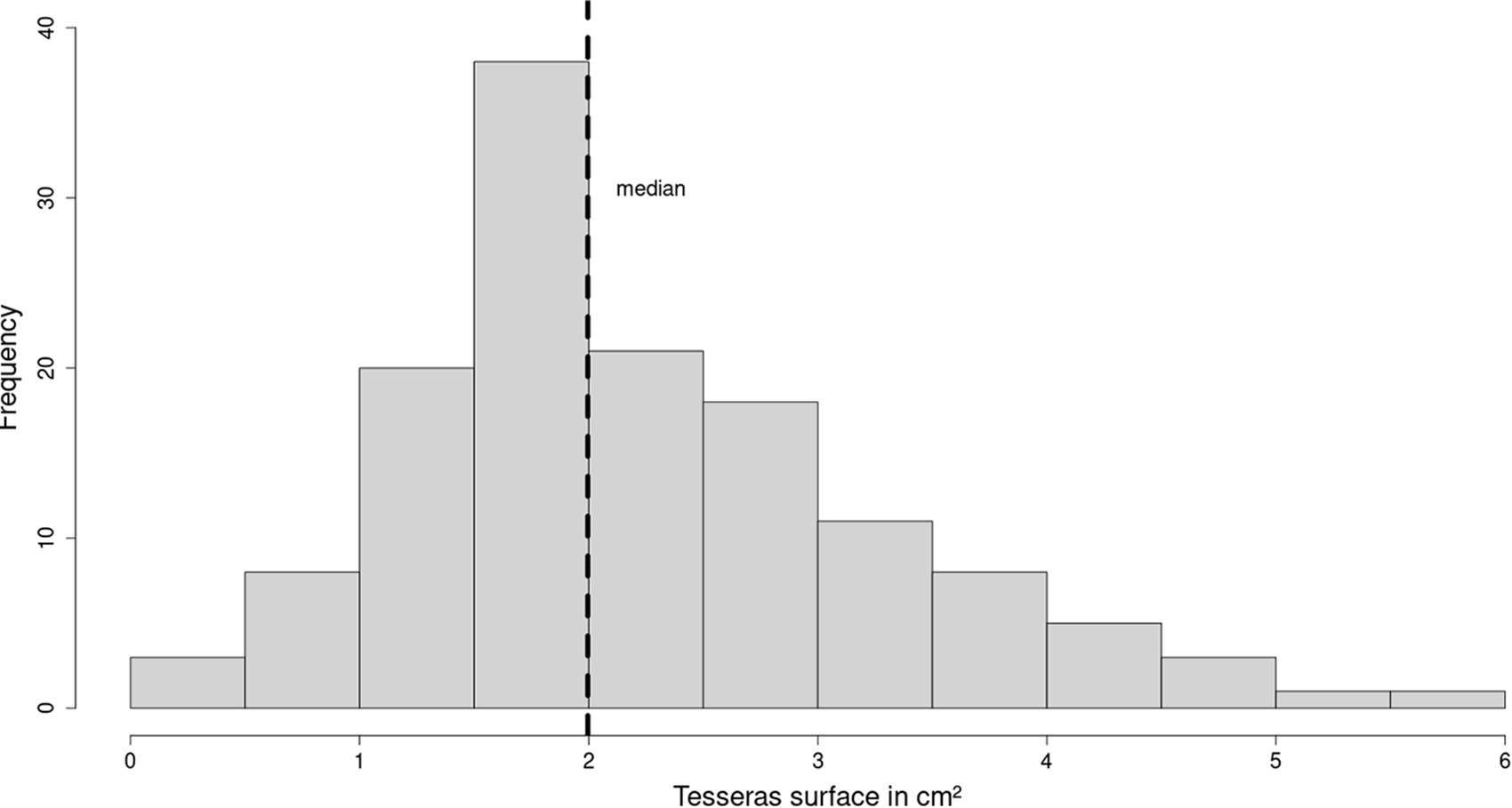

To better understand the way the mosaic board was created, we calculated the total number of sherds used to complete the design, based on the 94 sherds that are still set in the floor and the 55 empty imprints. We digitized the pattern of the best-preserved sides of the mosaic in QGIS (http://www.qgis.org.). We then generated the centroid for each in situ tessera and each imprint and calculated the average distance between nearest neighbors, obtaining an average of 2.5 cm. We then simulated the dimensions and configuration of the board to obtain an estimate of the number of tesserae and their probable positions. Based on an estimated number of 7 × 11 squares and estimated dimensions of 80 × 110 cm, we produced a grid of squares each measuring 11.25 × 10 cm. We then projected the centroids of probable tesserae on the grid, spaced at an interval of 2.5 cm. Because of the uneven sizes of the squares’ borders, the software occasionally produced centroids that were unrealistically close. To avoid this issue, we merged points that were too close to their neighbor, by creating buffers around each point, merging overlapping buffers, and extracting centroids from these buffers. The resulting model for tessera distribution is a close match for the original distribution from the archaeological remains (Figures 6 and 7). The model estimates the number of tesserae required to produce the full board as 478. Some uncertainty certainly affects the modeling; the relevant point to stress here is that several hundred sherds would have been needed to execute the full design. The tesserae were not purposefully made to form the mosaic: They are recycled materials.

Figure 7. Idealized reconstruction of the board according to the remaining elements, indicating the original number of tesserae calculated from the average distance between sherd centroids.

The Maya collected small, irregularly shaped fragments from various worn vessels, mostly homogeneous in size, although several sherds have a larger surface area. Digitizing the drawn record of the board, we obtained a median surface area per tessera of 1.99 cm2, a mean surface area of 2.25 cm2, and a standard deviation of 1.05 (Figure 8). This general homogeneity in size suggests some form of standardization. The creators also sought homogeneity in color: all the sherds have a reddish hue (Figures 5 and 9). Most are red or orange monochromes, a few have no slip but red paste, and others are mostly red polychromes. Red sherds may have been selected for their visibility (as they contrast more sharply with the mortar than gray, brown, or unpainted ones) or because of their cardinal symbolism, as in the Maya worldview, red is associated with the East (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Brittenham, Mesick, Tokovinine and Warinner2009). As a matter of fact, Źrałka notes the tendency to find the boards in structures positioned to the east, which “might have some calendar and astronomical connotations” (Źrałka Reference Źrałka2014:151). Although 6L-19 is the western structure of the pair 6L-19/6L-20, this pair is found to the east of the 6L13 compound. A few examples of patolli boards were painted on mortar surfaces and hence have color. The three painted cases mentioned by Walden and Voorhies (Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017) are either red or black, tied to the East and West, respectively, in Maya cosmography—they are painted red at Ruiz, a small Postclassic site in Chiapas (Lowe Reference Lowe1959:31), and black at Uxmal (Smith Reference Smith and Hammond1977:359) and Dzibilchaltun (Andrews Reference Andrews, Wyllys and Robertson1974:144).

Figure 8. Histogram of the distribution of the size (surface) of tesserae still in place in the board.

Figure 9. Weathered sherds from the patolli. (Color online)

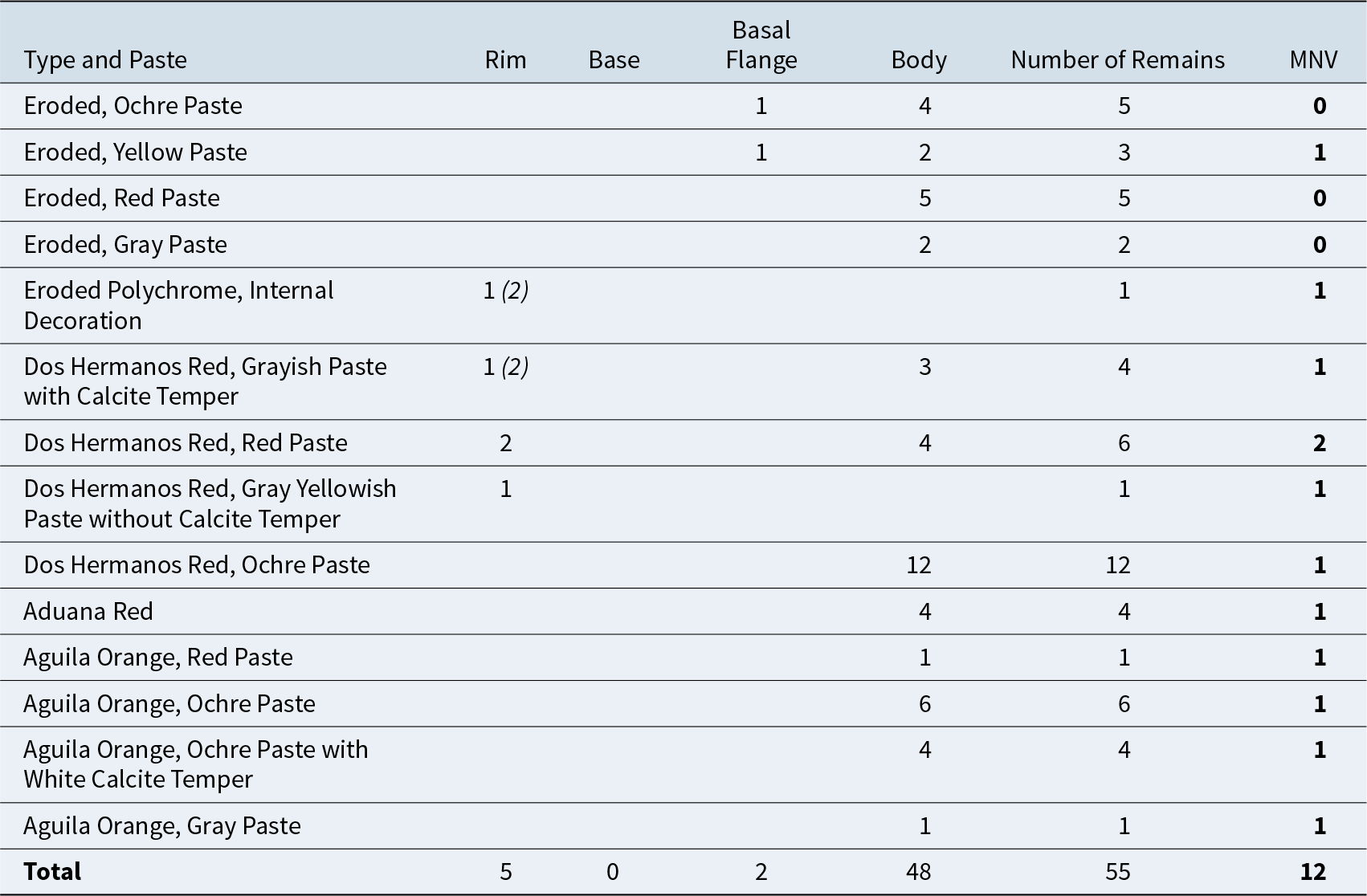

We proceeded to a type-variety-mode analysis of a sample of 57 sherds that probably pertain to the board but either were found in position but unbonded with the mortar or were accidentally removed from the floor during excavation. All come from the few centimeters just above the board and have dimensions comparable to the sherds still bonded to the floor. This sample yielded a conservative estimate of the minimum number of vessels (MNV) of 12 (Table 1), which likely underestimates the total number of vessels whose fragments were gathered, because most sherds, in addition to being very small, pertain only to the body of the vessel. Given the typological variety and the state of preservation of the tesserae—many of which are weathered (Figure 9)—it seems unlikely that the creators of the board obtained the sherds by smashing vessels on purpose. Rather, it is more likely that they collected sherds from a domestic midden.

Table 1. Calculation of the Minimum Number of Vessels of the Sample of Analyzed Sherds from the 6L-19 Patolli Board.

Although such small fragments are difficult to date, our analysis indicates they belong to Early Classic types. Most belong to Dos Hermanos Red and Aguila Orange types. Two fragments of large basal flanges, characteristic of the fourth-century AD production at Naachtun, were identified (they probably pertained to polychrome types, such as Dos Arroyos Orange Polychrome or Caldero Buff Polychrome). A rim fragment of an eroded polychrome dish with flaring sides decorated only on the interior dates slightly later, from the end of the Early Classic period (AD 400–550). The same temporal frame applies to the 94 sherds still in place, although our analysis of these was limited to observation of their surface (one is an incised orange type, probably Pita Incised). The date of the board is uncertain because if these hundreds of small sherds were obtained from a nearby midden they could be older than the date of construction of the board. The tesserae thus provide a terminus post quem for the board as a whole of the fifth century AD. To avoid damaging the board, we did not test the floor in Structure 6L-19 and thus do not know its age. However, we dug a small pit in the uppermost layer of flooring of nearby and parallel Structure 6L-20. No direct stratigraphic connection can be made between the floors of 6L-19 and 6L-20 because the space in between was not excavated, but the ceramics in the fill of the upper floor in 6L-20 are of types from the beginning of the Late Classic period.

Discussion: The Uniqueness and Relevance of the Naachtun Patolli Board

It appears that the Naachtun patolli board is unique among the corpus of patolli boards among the Maya, and even in the rest of Mesoamerica,in several ways.

1. It was inlaid in the recently constructed floor, whereas most known boards were etched—either on plastered floors and benches or, less frequently, on lintels and stone monuments (Fitzmaurice et al. Reference Fitzmaurice, Watkins and Awe2021:66; Swezey and Bittman Reference Swezey and Bittman1983:374; Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:201–202, Table 12.1)—and the remainder were drawn or painted on floors.

2. We can establish its relative date, whereas with etched or painted patolli boards, it is difficult to establish their chronology in relation to the occupational and construction sequences. Were they created shortly after construction, or are they later additions to existing architecture? Was it the original users of the structures who played the patolli, or later occupants or “squatters”? These questions, which are essential to all studies of patolli (and graffiti) in the Maya area (Andrews Reference Andrews1980; Fitzmaurice et al. Reference Fitzmaurice, Watkins and Awe2021:77; Hellmuth Reference Hellmuth2023; Kampen Reference Kampen1978:165; Patrois Reference Patrois2013; Smith Reference Smith and Hammond1977; Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:204, 208; Źrałka Reference Źrałka2014), are clearly answered for this Naachtun board because its most obvious characteristic is its contemporaneity with the construction of the floor. This means it must have been included in the architectural design from the moment of construction, even if the stratigraphy indicates this construction was probably an open space (possibly roofed but not walled). Note also that in some cases, excavators reported termination deposits of ceramic and various materials scattered right on top of the etched patolli boards (Novotny and Houk Reference Novotny and Houk2021). Here, no such deposit was found, either above the board or elsewhere in the structure. We can therefore rule out the possibility that the board was created as part of a termination ritual (as has been suggested for some graffiti; e.g., by Kampen Reference Kampen1978).

3. It may have had a longer use life than etched or painted boards. Fitzmaurice and colleagues (Reference Fitzmaurice, Watkins and Awe2021) have discussed the use life of etched patolli boards. The small amount of effort invested in their creation (often shallow scratches in the floor, with what seems to be poor attention given to the shape and regularity of the squares) suggests they were not durable. Were they made to be played only once, or for longer? With the inlaid board from Naachtun, some effort was invested to create a durable board. The creators had to gather hundreds of sherds of similar size and color and then inlay them into plaster. This is much costlier than the common modes of creation. Because it is impossible to know how long the board was exposed before the construction of 6L-19 (i.e., the stratigraphic sequence leaves a small possibility that in spite of the investment it represents, this board was not played for long), we cautiously suggest that the 6L-19 patolli board was planned to be played for a long time.

4. Floor mosaics are exceptionally rare in Maya architecture. While there are countless examples of portable artifacts fabricated or decorated with the mosaic technique, in shell, iron-ore, jade, or turquoise, to the best of our knowledge, no clear example of a floor mosaic exists in this part of the Western Hemisphere before the colonial period. Although the massive Olmec greenstone pavement offerings at La Venta (Drucker et al. Reference Drucker, Heizer and Squier1959) are a case of immovable ornamentation, the size of the slabs makes this ornamentation very different from the tesserae of a mosaic. In addition, unlike a mosaic, they were never meant to be exposed.

5. If the board is Early Classic, it is among the earliest in the Maya corpus. Early Classic Maya examples do exist, for example at Tikal (Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes 2015) and Copan (Fash and Fash Reference Fash, Fash and Uriarte2015), but as summarized by Walden and Voorhies (Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:203), Late Classic to Early Postclassic (AD 600–1200) examples predominate. The authors note, however, that the corpus may be biased by excavation strategies: many early examples must have been etched on earlier, sealed stucco layers, and these may not have been as systematically and completely exposed as the most recent archaeological layer (Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:209–210).

However, while it is unusual in these five aspects, when it comes to form, number of squares, and dimensions, this board falls well within the canons of the Maya corpus. Most Type II boards, like the one studied here, are positioned along the cardinal directions (Źrałka Reference Źrałka2014:151). Although many Mesoamerican boards have 11 squares on each side (Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:201), including the famous Seibal altar board (Smith Reference Smith and Hammond1977) and the board from Calakmul Structure VII (Gallegos Gómora Reference Gallegos Gómora1994), examples of Maya boards with an dissimilar number of squares on the east and west sides versus the north and south sides abound, including the extreme case of the board etched in the Str. 60-2 Room at Nakum (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1913:Figure 49f). While 57 squares appear to be standard in Postclassic depictions and Maya archaeological examples in the known corpus, the total number of squares varies (Gallegos Gómora Reference Gallegos Gómora1994; Smith Reference Smith and Hammond1977:356–357; Swezey and Bittman Reference Swezey and Bittman1983:400; Walden and Voorhies Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:197; Źrałka Reference Źrałka2014). The dimensions also vary, as shown in Gallegos Gómora’s (Reference Gallegos Gómora1994) list of other Maya examples: most measured around 40–70 cm a side, but they span the interval 10–100 cm. The board from Naachtun, while comparatively large, is therefore not unmatched. To sum up, the 6L-19 board appears to be the creative work of innovators, but it is a functional board, meeting the criteria of the Maya corpus for everything other than its mode of creation.

Conclusions

The 6L-19 patolli board, an outlier in the Mesoamerican corpus in terms of its execution, represents a unique stratigraphic position and construction technique, which offer a fresh perspective and invaluable information on some long-unresolved questions on this type of board game among the Maya. It is an unequivocal indication that a patolli board could be included in the design of a space from the beginning. Unlike the dozens of examples engraved in plaster, rock, or monuments, which are more difficult to date and are always suspected of being late additions unrelated to the original use of the building, the Naachtun example was part of the floor since its construction. Current evidence suggests the board may not have been located within an enclosed room. Further excavations will be aimed at understanding the function of Structures 6L-19 and 6L-20 and establishing whether there is an as-yet-undiscovered roofed space, to better contextualize this one-of-a-kind board and fully exploit its rich potential for understanding of how patolli was played during the Classic period.

Acknowledgments

Permissions were granted by the Instituto de Antropología e Historia, Guatemala. UMR 8096 ArchAm provided funding for copy editing of the manuscript. We thank the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. We are also grateful to the workers from the Uaxactun community for their hard work and assistance, which made this investigation possible.

Funding Statement

The Naachtun Archaeological Project is funded by the Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires Etrangères (France), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Pacunam Foundation, the Perenco Company, and the Del Duca Foundation; it is part of the activities of the Centre d’Etudes Mexicaines et Centraméricaines.

Data Availability Statement

The patolli board is still in place in mound 6L-19, protected by plastic bags and fine sediment. The excavation was stopped at the level of the floor and the trench was carefully backfilled. Sherds that were moved by roots and during degradation of the floor and whose position could not be firmly reconstructed were brought to the Naachtun Project’s laboratory in Guatemala City for analysis.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.