Introduction

The growing participation of women in the labour market represents a key transformative phenomenon in contemporary social and economic evolution, demonstrating steady growth over recent decades (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Jadick, Spence, DeReus, Sucandy and Rosemurgy2020), particularly in Western countries where women’s labour rights have significantly advanced (Nappo & Lubrano Lavadera, Reference Nappo and Lubrano Lavadera2024). However, this growth has also made more evident persistent inequalities, highlighting that increased female presence in various sectors has not necessarily translated into real equity regarding working conditions, salaries, and promotion opportunities (Milovanska-Farrington & Farrington, Reference Milovanska-Farrington and Farrington2022; Sukri, Ngah & Yiaw, Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023). Numerous structural and cultural barriers remain, embodied in gender biases and stereotypes deeply rooted in various occupational environments (Azima & Mundler, Reference Azima and Mundler2022; Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023), perpetuating dynamics that result in workplace discrimination, wage inequality, and unequal opportunities for women compared to their male counterparts (Milovanska-Farrington & Farrington, Reference Milovanska-Farrington and Farrington2022; Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023).

Among these barriers, the sexual division of labour emerges prominently, assigning women significantly greater domestic responsibilities and disproportionate workloads, a phenomenon known as the ‘double shift’ (Dethier, Stevens & Boden, Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024; Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023). This implies physical overload accompanied by invisible emotional and administrative responsibilities, such as household financial management, family activity coordination, and everyday domestic tasks (Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024). This additional burden negatively impacts mental health, considerably increasing stress, anxiety, and depression levels, reducing job satisfaction, and worsening overall quality of life (Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo & Cobos-Sanchiz, Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024).

Furthermore, gender interacts with factors such as ethnicity, culture, or socio-political context, exacerbating labour inequalities and generating significantly different experiences regarding job satisfaction among women from various backgrounds (Hersch, Reference Hersch2023; Hwang & Hoque, Reference Hwang and Hoque2023). For instance, in Western contexts, Black and Asian women report significantly lower job satisfaction levels compared to their colleagues (Hersch, Reference Hersch2023). Similarly, in strongly patriarchal cultural realities, such as certain regions in the Middle East or rural areas of Asia, women encounter more intense barriers to accessing better-paying, higher-responsibility positions due to both legal structures and social traditions limiting their full labour market participation (Sjølie, Akin & Lauritzen, Reference Sjølie, Akin and Lauritzen2023; Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023).

Regarding happiness, it is relevant to clarify that satisfaction and happiness are similar concepts but present some differences. Following Diener, Suh, Lucas and Smith (Reference Diener, Suh, Lucas and Smith1999), happiness refers to a broad evaluation of life satisfaction and positive affect, while satisfaction is a cognitive assessment of one’s overall life circumstances, both being central constructs in the study of subjective well-being. In this sense, it should be underlined that context relevance is a variable of happiness. Studies show that women with higher educational levels and in societies where their rights have long been recognized report lower satisfaction rates.

Conversely, in countries where women’s incorporation into the labour force is recent and still perceived predominantly as a male domain, higher job satisfaction levels are observed among women compared to men (Noll Araya, Romero Alonso & Ortiz Bacigalupo, Reference Noll Araya, Romero Alonso and Ortiz Bacigalupo2023). For example, a study in Iran on nurses’ job satisfaction showed that female nurses reported greater workplace happiness than their male colleagues, which is explained by the context of limited women’s rights in Iran, where the opportunity to work and achieve economic independence significantly boosts satisfaction (Mousazadeh, Yektatalab, Momennasab & Parvizy, Reference Mousazadeh, Yektatalab, Momennasab and Parvizy2018). In specific sectors such as agriculture, logistics, or health, these inequalities are even more pronounced, as these are traditionally male-dominated fields (Azima & Mundler, Reference Azima and Mundler2022; Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023; Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023).

Recent phenomena such as the COVID-19 pandemic have intensified work-family balance issues (Hennein, Gorman, Chung & Lowe, Reference Hennein, Gorman, Chung and Lowe2023), renewing academic interest in studying the effects of teleworking on female job satisfaction. Although teleworking has potential for improving work-life balance, it has also been linked to increased stress, feelings of guilt due to family interference in the workplace, and decreased job enjoyment, particularly among women (Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023).

Additionally, recent research on new forms of sexism, such as reverse sexism – the belief that men now experience systemic discrimination and gender biases – reveals how these emerging perceptions influence career planning, professional development, and women’s job satisfaction, adding complexity to workplace gender dynamics (Campos-García, Reference Campos-García2021; Morando, Zehnter & Platania, Reference Morando, Zehnter and Platania2023). This perception may minimize the actual difficulties faced by women by propagating the notion that gender inequality has already been overcome or even reversed.

Within this complex scenario, it is essential to highlight that women’s low job satisfaction impacts not only women’s quality of life but also organizational competitiveness and efficiency. Numerous studies emphasize that when employees – both men and women – feel supported in their well-being and satisfaction, organizations tend to experience increased productivity, reduced turnover rates, improved organizational climate, enhanced performance, decreased absenteeism, and a more collaborative work environment (Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024; Nappo & Lubrano Lavadera, Reference Nappo and Lubrano Lavadera2024; Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023).

Although promoting employee happiness has proven beneficial for organizations (Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo & Mansfield, Reference Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo and Mansfield2012; Wu, Rafiq & Chin, Reference Wu, Rafiq and Chin2017; Albarracín et al., Reference Albarracín, Núñez-Sánchez, Morales-Rodríguez, Molina-Gómez and Melé2024), women generally report lower levels of happiness compared to men. This difference is influenced by environmental factors, gender roles imposing greater workloads, limited leisure and rest time, and working conditions. From a strategic perspective, it seems ineffective for a significant portion of the workforce to remain unsatisfied. Therefore, companies that focus on enhancing employee happiness could achieve improved overall productivity and competitiveness.

Given this complex scenario, conducting a systematic bibliometric review on the job satisfaction of working women becomes essential. Understanding the current state of research will help identify trends, detect critical knowledge gaps, and establish clear directions for future studies, providing organizations with valuable insights to design inclusive and effective labour policies. To summarize, this study seeks to address the following research questions:

• Q1: What are the trends in publications and citations?

• Q2: Who are the main authors in this field?

• Q3: What are the main research clusters?

• Q4: What are the future research trends?

While RQ1–RQ4 are standard in bibliometric reviews, in this study, they are explicitly anchored to the field of women’s job satisfaction. Accordingly, RQ1 (trends) is interpreted across the disciplinary areas most active in the field (Economics and Business, Psychology, Public Health, Social Sciences); RQ2 (main authors) considers specialization and geographical contexts; RQ3 (research clusters) is read through the integration of non-work determinants and gendered structures observed in the maps (e.g., work–family conflict, mental health); and RQ4 (future trends) synthesizes substantive avenues already surfaced by the evidence (intersectionality, digital transformation/remote work, mental health, and feminist/critical metrics).

Appropriateness and contribution of a bibliometric review

Given our research questions (Q1–Q4) – which integrate performance analysis and science mapping – a bibliometric review constitutes the most suitable design to structure a fragmented field, uncover the underlying knowledge network and thematic bridges, and translate the mapped patterns into prospective research agendas. Within our WoS-based corpus, the field exhibits disciplinary dispersion and lacks a stable core of highly prolific authors, further supporting the relevance of a conceptual mapping approach. Accordingly, our contribution extends beyond descriptive reporting by (i) providing a structural baseline of prevailing trends, key actors, and thematic clusters; (ii) identifying integrative linkages that connect women’s job satisfaction with work–family conflict and mental health (Figs. 6–7) and (iii) proposing an integrative conceptual framework that informs the targeted research agendas elaborated in Conclusions.

Methodology

This study employs a bibliometric review method, a type of systematic literature review (SLR). Bibliometric analysis is a widely used and rigorous technique for exploring and evaluating large volumes of literature, enabling observation of the evolution of a specific field and its primary trends (Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey & Lim, Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021). Bibliometric analysis should consider both scientific performance and scientific mapping. Performance analysis assesses contributions of research components, while scientific mapping focuses on relationships among these components (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021).

For this paper, an exhaustive review of literature from 2010 on women’s workplace happiness was conducted using the Web of Science (WoS) platform. WoS comprises databases collecting bibliographic references and citations from periodicals dating back to 1900.

This study relies on the WoS Core Collection due to its editorial curation, metadata stability, and retrospective depth (Martínez, Herrera, Contreras, Ruíz & Herrera-Viedma, Reference Martínez, Herrera, Contreras, Ruíz and Herrera-Viedma2015; Sánchez-Núñez, Cobo, De Las Heras-Pedrosa, Peláez & Herrera-Viedma, Reference Sánchez-Núñez, Cobo, De Las Heras-Pedrosa, Peláez and Herrera-Viedma2020), as well as the precision and reliability of its research information. These features enhance the reproducibility and comparability of science mapping in the fields of management and organization. Since existing databases differ structurally in their coverage across disciplines, languages, and regions, this analysis was conducted using a single database to minimize exogenous heterogeneity and maximize traceability. This approach enables us to report the query string, filters, and extraction date, thereby ensuring exact replication (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Reference Mongeon and Paul-Hus2016).

The bibliometric study included scientific publications containing the concepts (wom?n) NEAR/7 (‘job satisfaction’ OR ‘workplace happiness’ OR ‘work satisfaction’) between 2010 and 2024. The search was conducted on 9 September 2024, yielding 590 documents. The initial selection process involved retaining only articles, resulting in 441 documents. Next, articles from the core collection were selected for their scientific quality (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021), reducing the total to 318 documents. Finally, the focus was limited to English-language publications, resulting in 307 final documents.

Despite its advantages, bibliometric analysis remains a relatively recent tool in business research and often underutilizes its full potential when restricted to a limited data set or bibliometric techniques, leading to an incomplete understanding (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021). Therefore, a rigorous protocol is advisable for correct application (Serrano, Navarro & González, Reference Serrano, Navarro and González2022). This article employs the SPAR-4 protocol for conducting a comprehensive bibliometric analysis.

SPAR-4 review protocol

This study follows the Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews protocol developed by Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani (Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). This protocol is designed to describe the intellectual structure and interrelationships within the body of scientific production, rather than to assess the methodological quality of individual studies or estimate effect sizes. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as patterns of co-occurrence and connectivity, not as causal evidence or quality hierarchies.

Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews is a structured framework for conducting SLRs. It provides researchers with a comprehensive set of procedures and rationales that guide each stage of an SLR, ensuring a rigorous and transparent review process (Sauer & Seuring, Reference Sauer and Seuring2023).

In this Figure 1 summarizes the procedure guiding this review.

Figure 1. SPAR-4 protocol. Visual description of the SPAR-4 protocol used to carry out this review.

Incorporation of gender perspective in the review

The systematic inclusion of a gender perspective enables a deeper understanding of disparities in women’s job satisfaction and happiness (Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023; Milovanska-Farrington, Reference Milovanska-Farrington2023). Feminist theory and gender studies highlight that equity gaps and power asymmetries in the workplace largely stem from persistent gender stereotypes and roles (Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024). Thus, this bibliometric review addresses not only scientific productivity or citation evolution but also cross-cutting factors influencing opportunities, well-being, and professional development for women across various cultures and sectors (Azima & Mundler, Reference Azima and Mundler2022; Hwang & Hoque, Reference Hwang and Hoque2023).

Applying a gender perspective in the analysis necessitates identifying biases within both literature and search methodologies (Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023; Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023). Likewise, this approach demands incorporating intersectional elements such as ethnicity, social class, or sexual orientation, recognizing that overlapping inequalities exacerbate discrimination and affect women’s job satisfaction (Abu-Kaf, Kalagy, Portughies & Braun-Lewensohn, Reference Abu-Kaf, Kalagy, Portughies and Braun-Lewensohn2023; Hersch, Reference Hersch2023).

Data acquisition, cleaning, and processing

Data source and search

We queried WoS on 9 September 2024 using the string (wom?n) NEAR/7 (‘job satisfaction’ OR ‘workplace happiness’ OR ‘work satisfaction’) for the period 2010–2024, which returned 590 records. We then applied sequential filters: articles only (441), Core Collection subset (318), and English-language publications, yielding the final corpus of 307 records. We follow the Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews protocol to ensure transparency and replicability (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021).

Database selection and replicability rationale

The study relies on the WoS Collection to ensure editorial curation, metadata stability, and exact replicability of the search process (search string, filters, and extraction date, as previously reported). Integrating databases with structurally different coverage and indexing policies (e.g., Scopus) may distort performance indicators and network topologies, thereby limiting cross-study comparability in science mapping (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Reference Mongeon and Paul-Hus2016). Although Google Scholar provides extensive coverage, the literature highlights its noisy metadata, limited deduplication and export functions, and reproducibility challenges, making it unsuitable as a primary source for rigorous bibliometric analyses (Gusenbauer & Haddaway, Reference Gusenbauer and Haddaway2020; Harzing & Alakangas, Reference Harzing and Alakangas2016; Martín-Martín, Orduna-Malea, Thelwall & Delgado López-Cózar, Reference Martín-Martín, Orduna-Malea, Thelwall and Delgado López-Cózar2018). Recent methodological reviews position WoS and Scopus as the leading databases for bibliometric research, with the choice contingent upon study objectives. For our purpose – conceptual mapping requiring high metadata comparability and traceability – WoS offers the most appropriate fit (Pranckutė, Reference Pranckutė2021). The scope limitations of a single-database design are discussed in Limitations.

Rationale for query operators and filters

The NEAR/7 operator was chosen to promote semantic proximity among key terms, aligning the retrieval with our specific focus on women’s job satisfaction; we acknowledge it may exclude relevant but less proximate expressions. The Core Collection restriction and article-type filter prioritize metadata quality and comparability; the English-language constraint supports consistency in keyword processing and interpretation. These decisions are recognized as coverage constraints and are discussed in Limitations.

Processing for analyses

Publication and citation trends were generated using WoS-provided data (Fig. 2). For the keyword co-occurrence network (Fig. 6), we used VOSviewer.1.6.20: from 1,532 keywords retrieved, we set a minimum co-occurrence threshold of 5, obtaining 102 terms; after removing duplicate keywords, the final set comprised 97 terms (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010). We also produced a word cloud (Fig. 7) with Bibliometrix R to visualize the most frequent concepts (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). The chosen threshold (5) reflects a balance between parsimony and inclusion (we considered six but opted for five to capture a broader set of connections).

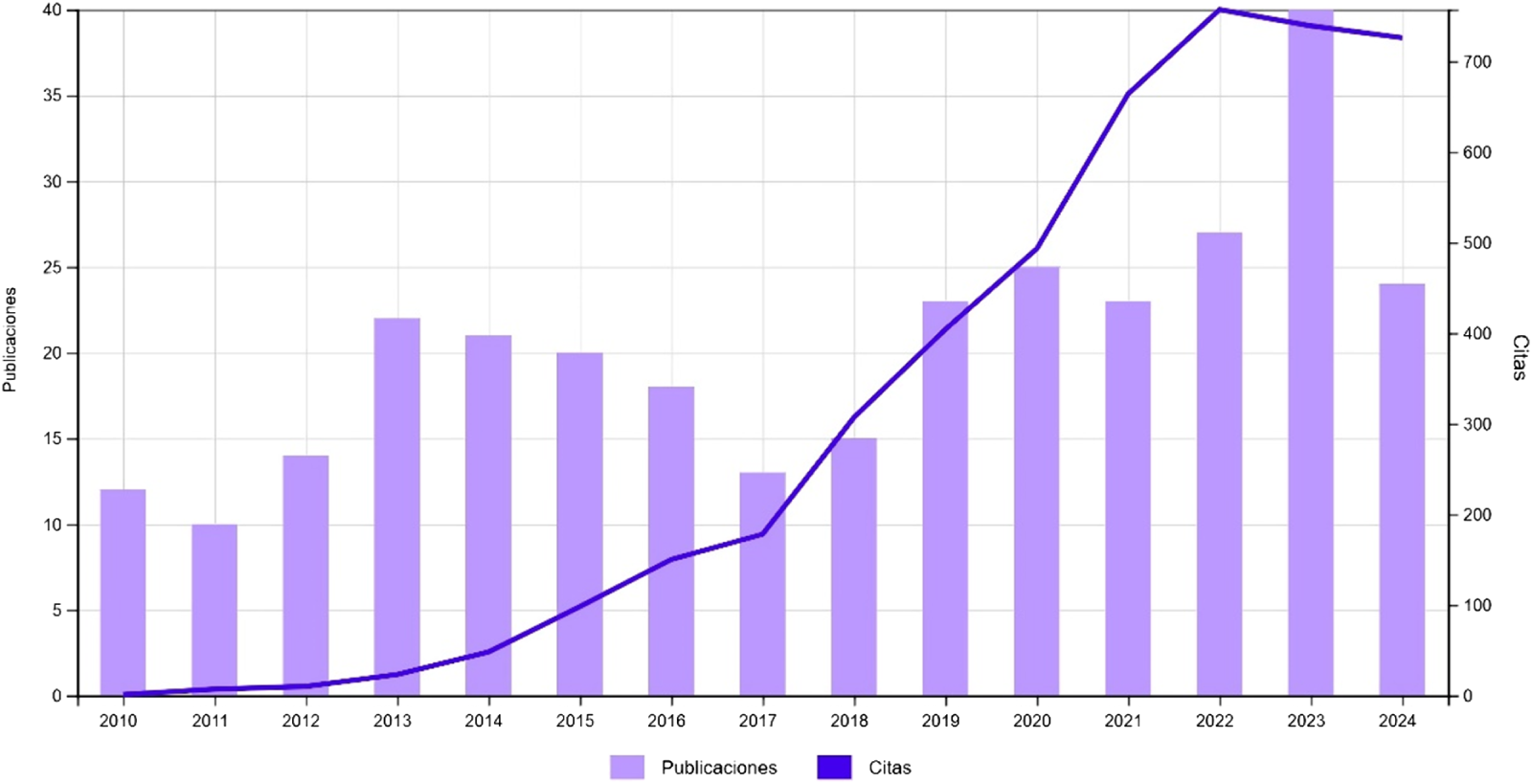

Figure 2. Evolution of publications and citations from 2010 to 2024.

Time window

We predefined a contemporary time window (2010–2024) to ensure alignment between the review’s scope and its research questions. The primary objective is to capture the current configuration and recent evolution of the field, rather than to reconstruct its entire historical trajectory. This temporal design provides sufficient longitudinal depth to address RQ1–RQ3 and to translate the mapped evidence into RQ4 (future trends), as reflected in the publication and citation dynamics reported in Fig. 2 and respective sections. Furthermore, co-occurrence-based science mapping benefits from the enhanced consistency and comparability of metadata (e.g., author keywords) in the past decade and a half, facilitating more robust network construction and cluster interpretation (Aria & Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017; Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021; Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015). It is important to note that the choice of 2010 as the starting point does not reflect any exogenous event but rather a deliberate design decision consistent with the study’s objectives and bibliometric techniques.

Results

Citation and publication analysis

The study began with an analysis of publication and citation trends. For this purpose, data provided by WoS was used to generate a graph summarizing information on these indicators. As shown in Fig. 2, two distinct trends can be observed. On the one hand, publications show an overall upward trend, although not a consistent one. Periods of growth in the number of publications compared to the previous year alternate with periods of decline. However, starting in 2017, there is a notable increase in the number of annual publications, reaching 40 in 2023. At the time of conducting the search, 24 articles had already been published in 2024, exceeding the average of the previous five years, although likely falling short of the 2023 result.

On the other hand, citation trends display a more consistent upward progression from the beginning of the review period, with the exception of 2023, which saw a slight decrease. Over the analysed period, citations rose from just 1 in 2010 to 757 in 2022. As previously noted, 2023 experienced a minor decline, but based on the data available for 2024, this drop appears to be a temporary fluctuation. This shows that it is a topic that generates growing interest in the scientific community.

Analysis by journals

The total number of journals that have published at least one article related to this field is 227. As shown in Fig. 3, where we highlight the 20 journals with the highest number of publications, there is no clear leading journal in this area. Therefore, the field presents significant fragmentation.

Figure 3. Publications by magazines from 2010 to 2024.

The journal Gender in Management is the one with the highest number of publications, totalling 10 articles. This represents only 3.25% of all publications. In second place is Social Indicators Research, with eight publications, accounting for 2.60% of the total. Following these are two journals with seven publications each: Frontiers in Psychology and International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Each of these represents 2.28% of the total scholarly output in this field.

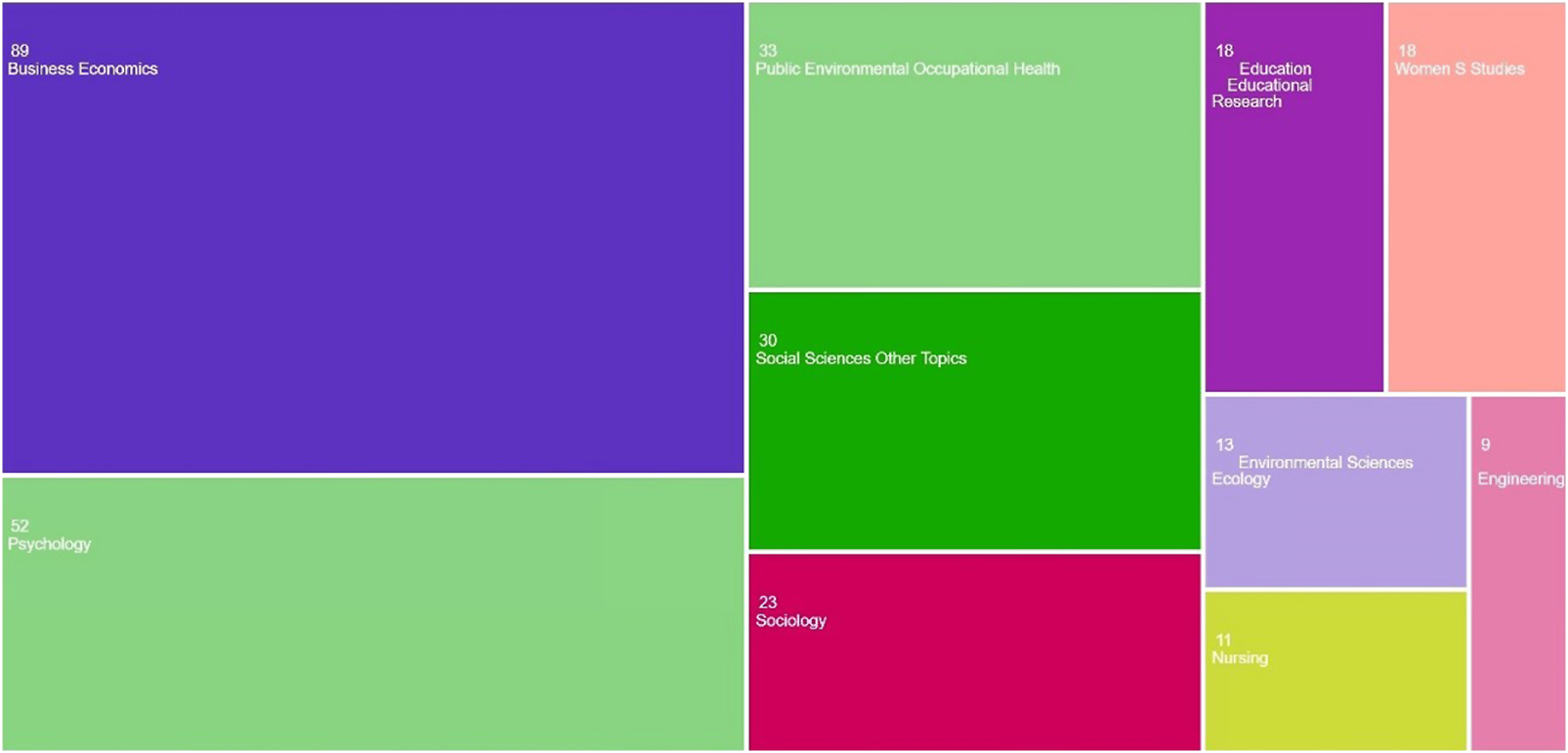

Given this fragmentation and the absence of clear reference journals, it becomes necessary to analyse the prominent knowledge areas related to this topic (Fig. 3) to better understand the scientific production in the field. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the four main areas of study that have been published on women’s happiness at work are: Economics and Business, Psychology, Public Health, and Social Sciences. These four fields together account for 204 out of the 307 articles included in this analysis.

Figure 4. Main areas of publications. Source prepared by the authors using Web of Science.

Nevertheless, the area of Economics and Business stands out as the most prolific, with 89 publications – nearly 30% of the total. This indicates that the topic of working women’s happiness is of particular interest to economic literature, especially in relation to business and resource management.

Considering all the points discussed thus far, we can now address the first research question posed in this review: Q1: What are the trends in publications and citations?

The trend – particularly in terms of citations – has shown a clear upward trajectory over the past 14 years, reaching its peak in 2022. Although the total number of publications is not particularly high, there is a growing interest in the topic among researchers. This interest is concentrated primarily in four main fields: Economics and Business, Psychology, Public Health, and Social Sciences, with Economics and Business leading significantly.

This suggests that the happiness of working women is increasingly seen as a relevant concern within the realms of business and organizational management. While there is some thematic concentration in terms of academic discipline, there is no single journal that stands out as a reference in the field. As previously noted, the journal with the highest number of publications has only 10 articles out of a total of 307, and the total number of journals that have published at least one article on this topic is 227 – a notably high figure that contrasts somewhat with the increasing scholarly interest in the subject.

Authorship and citation analysis

The analysis in this section will allow us to answer Q2: Who are the main authors in this field?

The review reveals a noteworthy finding: the absence of prolific authors in this area, which highlights a lack of specialization in the field.

As shown in the following Fig. 5, only three authors have more than two publications: Nuria Sánchez Sánchez, Adolfo Cosma Fernández Puente, and Hayfa Tlaiss. The first two, Sánchez-Sánchez, N. and Cosma-Fernández, A., each have four articles, while the third, Tlaiss, H., has three. Together, this represents just over 3.5% of the total. It is important to note that Sánchez-Sánchez, N. and Cosma-Fernández, A. have collaborated on all four of their articles, meaning their contributions overlap. In contrast, Tlaiss, H. has conducted her research either individually or, at most, with one co-author. This fact might lead us to reconsider how authorship is classified, potentially viewing Sánchez-Sánchez, N. and Cosma-Fernández, A. as a single authorship unit, which would place Tlaiss, H. as the second most prolific contributor. Nevertheless, the overall number of publications remains low, highlighting the limited specialization in this field.

Figure 5. Leading authors. A graphic illustrating the main authors who have contributed to these topics.

Sánchez-Sánchez, N. and Cosma-Fernández, A.´s publications focus on the European and Spanish contexts, whereas Tlaiss, H. conducts her research in the Middle East, particularly in Lebanon. This contrast allows us to explore two different realities regarding the management of working women’s happiness: one in Western countries, where women’s rights and labour market access are more advanced; and another in Middle Eastern countries, where women have less presence in the workforce, and their rights are more restricted. Naturally, these two contexts yield different results regarding women’s job satisfaction and its determinants (Mousazadeh et al., Reference Mousazadeh, Yektatalab, Momennasab and Parvizy2018; Noll Araya et al., Reference Noll Araya, Romero Alonso and Ortiz Bacigalupo2023).

It is particularly noteworthy that, despite being among the most prolific authors, none of the three have published any articles on this topic since 2021.

Beyond Tlaiss, H., the number of contributors with only one or two publications increases significantly, reaching a total of 87 individuals who have authored at least one article related to this field of study. This further underscores the fragmentation of the field and the scarcity of well-established academic figures.

Regarding the most cited articles, the following stand out:

• Feng and Savani (Reference Feng and Savani2020): COVID-19 created a gender gap in perceived work productivity and job satisfaction: implications for dual-career parents working from home. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 35(7/8), 719-736. 176 citas

• Glass, Sassler, Levitte and Michelmore (Reference Glass, Sassler, Levitte and Michelmore2013): What’s so special about STEM? A comparison of women’s retention in STEM and professional occupations. Social forces, 92(2), 723-756. 168 citas.

• Clark, Chatterjee, Martin and Davis (Reference Clark, Chatterjee, Martin and Davis2020): How commuting affects subjective wellbeing. Transportation, 47(6), 2777-2805. 140 citas

• Batz-Barbarich, Tay, Kuykendall and Cheung (Reference Batz-Barbarich, Tay, Kuykendall and Cheung2018): A meta-analysis of gender differences in subjective well-being: Estimating effect sizes and associations with gender inequality. Psychological Science, 29(9), 1491-1503. 101 citas

It is worth highlighting from these findings that the works by Feng and Savani (Reference Feng and Savani2020) and by Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Chatterjee, Martin and Davis2020) include enriched cited references – a recent feature designed to help readers better understand why and how a specific reference was used in the work being viewed. In the case of Feng and Savani (Reference Feng and Savani2020), these enriched references are closely linked to the relationship between women’s family life – and the extensive responsibilities it entails – and job satisfaction. This duality is compelling and may warrant deeper investigation. Meanwhile, in the study by Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Chatterjee, Martin and Davis2020), the enriched references focus on the influence of commuting on women’s job satisfaction. This is also an interesting perspective, as it adds an additional stress factor to those already associated with paid labour and domestic work. This may align with the perspective of certain authors who link overall satisfaction – including job satisfaction – to the availability of leisure time (Bernhardt, Reference Bernhardt2004; Blossfeld & Drobnic, Reference Blossfeld and Drobnic2001; Neuwirth & Wernhart, Reference Neuwirth and Wernhart2008).

Keyword analysis

The following analysis focuses on co-occurrence, that is, the joint appearances of two terms within the same article, which helps to identify the conceptual and thematic structure of the literature under review (Gálvez, Reference Gálvez2018). Based on this co-occurrence of terms, different clusters will be generated and analysed subsequently.

To create the keyword co-occurrence network shown in Fig. 6, the software VOSviewer was used. In this case, concerning the analysis of working women’s happiness, a total of 1,532 keywords was retrieved. For inclusion in the analysis, a minimum co-occurrence threshold of five was established, resulting in 102 keywords. After refining the data to remove duplicates, five keywords were excluded, leaving a final set of 97.

Figure 6. Keyword Co-occurrence. A graphic in which we can observe the main clusters and the relationships between the main words.

When interpreting the results, it is important to note that the size of the labels and circles is proportional to the frequency and strength of the connections (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010).

As can be observed, the most frequent keywords and those with the strongest connections are ‘job satisfaction’, ‘gender’, ‘women’, and ‘work’. A large portion of the literature related to this topic is built around these terms. One particularly interesting relationship is the link between job satisfaction and family. In this regard, other relevant associations emerge that connect job satisfaction with family conflicts, gender, stress, and mental health. These relationships provide scientific evidence that supports the connection between women’s job satisfaction and their family realities. This reinforces the idea that gender roles and the double burden carried by women significantly influence their job satisfaction (Akobo & Stewart, Reference Akobo and Stewart2020; Andrade, Miller & Westover, Reference Andrade, Miller and Westover2022; Feng & Savani, Reference Feng and Savani2020).

It is also noteworthy how the concept of gender is strongly connected with terms related to mental health and stress. This suggests a growing interest in analysing the intersection between mental health and work, and how working women – due to gender stereotypes and dual roles – tend to show different outcomes (Batz-Barbarich et al., Reference Batz-Barbarich, Tay, Kuykendall and Cheung2018).

To better understand the scope of this study, a word cloud was also generated featuring the most frequently used concepts in the analysed literature (Fig. 7). As shown, the most prominent words are gender, work, woman, and job satisfaction. At a lower level – but still significant enough to be included in the visualization – we find terms related to non-work domains such as ‘family conflict’, ‘work-family conflict’, ‘family’, ‘life satisfaction’, ‘health’, and ‘mental health’.

Figure 7. Keyword word cloud. A graphic that represents the strength of word associations.

This demonstrates that the job satisfaction of working women is influenced by a variety of factors, not only workplace conditions. One of these key factors is related to family responsibilities and domestic obligations. Likewise, the notable presence of words such as ‘gender’, ‘sex’, ‘woman’, and ‘man’ indicates that existing research consistently identifies gender-based differences in job satisfaction.

Cluster analysis

From the bibliometric review and the keyword co-occurrence analysis, several clusters emerged that group together themes and research approaches related to women’s job satisfaction. The use of VOSviewer (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021) enabled the identification of interconnections among key concepts and helped to distinguish both established and emerging lines of inquiry within the field.

To construct these clusters, both the relative distances between nodes and their connectivity were considered in order to form coherent groups (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010). In this study, six distinct clusters were identified, each representing a major line of research on women’s happiness and job satisfaction. Each of these clusters is described in detail below.

Cluster 1: Variables of job satisfaction

This group, composed of 26 terms, is highly heterogeneous, as it brings together many of the variables that may influence working women’s job satisfaction and its impacts – or consequences. The most frequently occurring terms are performance and impact, although model and antecedents are also significant. Analysing these terms, we can affirm that this cluster is characterized by concrete and quantitative studies on the happiness of working women, focusing on how it is approached through the actions performed and the impact of the different variables involved.

At the same time, a diverse range of analyses can be observed, aiming to relate women’s job satisfaction to different factors. Authors explore how religion and values may influence women’s workplace happiness (Arias, Masías, Muñoz & Arpasi, Reference Arias, Masías, Muñoz and Arpasi2013; Jurek, Niewiadomska & Szot, Reference Jurek, Niewiadomska and Szot2023; Kalagy, Abu-Kaf & Braun-Lewensohn, Reference Kalagy, Abu-Kaf and Braun-Lewensohn2022; Tziner, Shkoler & Fein, Reference Tziner, Shkoler and Fein2020), how gender differences themselves may condition this satisfaction (Milovanska-Farrington, Reference Milovanska-Farrington2023; Pita & Torregrosa, Reference Pita and Torregrosa2021), or how organizational characteristics shape job satisfaction (Clark, Rudolph, Zhdanova, Michel & Baltes, Reference Clark, Rudolph, Zhdanova, Michel and Baltes2017; Samo, Ozturk, Mahar & Yaqoob, Reference Samo, Ozturk, Mahar and Yaqoob2019). These varied approaches contribute to a deeper understanding of the wide range of elements that can influence the job satisfaction of working women.

Cluster 2: Women, work, and structural inequalities

This cluster is composed of 20 terms, with the most frequently occurring being women and work, appearing 81 and 69 times, respectively. This cluster explores how work influences – or fails to influence – women’s happiness and overall life satisfaction. When analysing the term work within this cluster, it is understood as referring to work in general, not just ‘paid employment’. From this perspective, the focus is on understanding how work overload affects working women (Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024; Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023; Orešković et al., Reference Orešković, Milošević, Košir, Horvat, Glavaš, Sadarić and Orešković2023) and how, in workplace environments dominated by gender stereotypes, women tend to report lower levels of happiness (Otten & Alewell, Reference Otten and Alewell2020; Rebelo, Delaunay, Martins, Diamantino & Almeida, Reference Rebelo, Delaunay, Martins, Diamantino and Almeida2024).

This cluster also includes research on horizontal and vertical labour segmentation, the gender pay gap, and the limited opportunities for advancement available to women (Milovanska-Farrington & Farrington, Reference Milovanska-Farrington and Farrington2022). Likewise, it incorporates analyses of the influence of ethnicity and culture on women’s experiences, particularly those belonging to minority groups or originating from societies with deeply entrenched patriarchal structures (Abu-Kaf et al., Reference Abu-Kaf, Kalagy, Portughies and Braun-Lewensohn2023; Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023).

Another important topic in this cluster is the relationship between family and work, and how this dynamic affects the job satisfaction of working women (Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023; Theule, Ward, Keates, Cook & Bartel, Reference Theule, Ward, Keates, Cook and Bartel2023). The concept of ‘double presence’ – which implies significant involvement in both professional and domestic spheres – is highlighted as a source of physical and emotional overload (Giurge, Whillans & Yemiscigil, Reference Giurge, Whillans and Yemiscigil2021; Smeets, Whillans, Bekkers & Norton, Reference Smeets, Whillans, Bekkers and Norton2020).

Cluster 3: Working conditions and health

Cluster 3 focuses on how working conditions influence the health of employed women and, in turn, how this affects their job satisfaction. It comprises a total of 14 terms, with health, burnout, and stress being the most frequent, appearing 69, 64, and 56 times, respectively. The studies within this cluster explore how employment and working conditions affect health, and how health, in turn, impacts job satisfaction.

In this context, research shows that institutional support and mentoring networks contribute to improving women’s job satisfaction and retention (Hennein et al., Reference Hennein, Gorman, Chung and Lowe2023; Nappo & Lubrano Lavadera, Reference Nappo and Lubrano Lavadera2024). Moreover, the presence of women in leadership roles is associated with greater satisfaction within organizations (Faghihi, Farshad, Abhari, Azadi & Mansourian, Reference Faghihi, Farshad, Abhari, Azadi and Mansourian2022; Milovanska-Farrington, Reference Milovanska-Farrington2023; Seely, Reference Seely2024). Conversely, environments characterized by persistent gender stereotypes and a lack of recognition for female talent foster a climate that is not conducive to women’s professional development (Morando et al., Reference Morando, Zehnter and Platania2023).

Additionally, studies within this cluster examine the relationship between burnout and job satisfaction, highlighting how burnout disproportionately affects women (Aazami, Shamsuddin, Akmal & Azami, Reference Aazami, Shamsuddin, Akmal and Azami2015), and how it is closely linked to perceptions of injustice and difficulties in achieving work-family balance (Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024; Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023).

Notably, the findings from this cluster reinforce the urgent need to promote structural changes that address the root causes of imbalances in the work environment, in order to preserve the mental and physical health of women workers (Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024).

Cluster 4: Gender, satisfaction, and job satisfaction

This cluster examines the influence of gender on job satisfaction and how it, in turn, impacts overall life satisfaction. It is composed of 13 terms, with job satisfaction, gender, and life satisfaction being the most frequently used, appearing 96, 89, and 54 times, respectively.

Several studies focus on how the balance between personal life and work affects job satisfaction and how women, in particular, experience greater overload, which reduces their level of job satisfaction (Anton, Reference Anton2024; Cunha, Cruz & Belim, Reference Cunha, Cruz and Belim2025; Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024; Nappo & Lubrano Lavadera, Reference Nappo and Lubrano Lavadera2024).

Among the research that delves into the work-life balance, one interesting line of inquiry explores how part-time employment facilitates such reconciliation. In most cases, it is women who accept these types of contracts in order to ‘fulfil their gender obligations’ (Theule et al., Reference Theule, Ward, Keates, Cook and Bartel2023). However, this situation is generally not satisfying for women, who would prefer to advance their careers rather than maintain the traditional role focused on domestic tasks. Nonetheless, factors such as the gender pay gap and cultural norms lead many to accept this role (Navarro & Salverda, Reference Navarro and Salverda2019).

Cluster 5: Satisfaction and mental health

This cluster is composed of 11 items, with the most frequently appearing being work-family conflict, satisfaction, and mental health, with 51, 50, and 43 occurrences, respectively. The studies in this cluster explore how conflicts between family responsibilities and work affect the job satisfaction of working women and how this, in turn, impacts their mental health.

A key finding is that, due to taking on a greater share of domestic responsibilities, working women experience work overload, which negatively affects both their satisfaction and mental health – contributing to chronic stress, anxiety, and depression (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Cruz and Belim2025; Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024; Roeters & Craig, Reference Roeters and Craig2014). The heavier workload typically assumed by women generates greater psychological distress and tension, making it harder for them to feel satisfied overall, including in the workplace (Anton, Reference Anton2024; Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Cruz and Belim2025).

These negative effects are exacerbated when organizations fail to offer flexible scheduling, adequate leave policies, or support networks, which increases dissatisfaction and psychological discomfort (Pinnington, Aldabbas, Mirshahi & Brown, Reference Pinnington, Aldabbas, Mirshahi and Brown2024).

The literature also highlights the protective role of social support. Workplace environments that foster collaboration, mutual assistance, and empathetic organizational climates can promote resilience and improve the mental health of working women (Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023; Hennein et al., Reference Hennein, Gorman, Chung and Lowe2023).

Cluster 6: Work–family resources and outcomes

This cluster includes 10 terms, with the most frequently occurring being outcomes, family conflict, and resources. The studies in this cluster examine the importance of work-life balance in women’s job satisfaction. This issue gained particular relevance following the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Orešković et al., Reference Orešković, Milošević, Košir, Horvat, Glavaš, Sadarić and Orešković2023). During this period, both work and domestic demands increased, leading to family conflict (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Cruz and Belim2025; Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024; Li & Wang, 2022) and a rise in emotional spillover between the two domains (Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023).

Within this context, research highlights the need for organizations to be aware of how work-life balance affects female employees’ experiences, and to implement strategies that address this reality (Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023; Rouxel, Michinov & Dodeler, Reference Rouxel, Michinov and Dodeler2016).

Cross-cluster thematic synthesis (antecedents, moderators/mediators, outcomes, and contexts)

Purpose

To enhance comparability and interpretability, the six clusters are synthesized into four analytical categories – antecedents, moderators/mediators, outcomes, and contexts/theoretical lenses – grounded in the clusters’ highest-weight terms and their roles within the network (Figs. 6–7). This synthesis addresses RQ3 and provides the conceptual scaffolding for RQ4.

Antecedents (drivers and conditions)

C1 (Variables of Job Satisfaction) contributes quantitative determinants (e.g., performance, model, antecedents) (Cluster 1: Variables of job satisfaction). C3 (Working Conditions and Health) adds work environment factors (e.g., burnout, stress, health) and organizational characteristics (mentoring, leadership) (Cluster 3: Working conditions and health). C2 (Women, Work, and Structural Inequalities) introduces structural drivers (segmentation, pay gap, stereotypes, intersectionality).

Moderators/mediators (mechanisms and resources)

C5 (Satisfaction and Mental Health) highlights work–family conflict and psychological mechanisms (stress, mental health) that transmit or condition effects (Cluster 5: Satisfaction and mental health). C6 (Work–Family Resources and Outcomes) incorporates resource-based and family-conflict dynamics, including post-COVID intensification (Cluster 6: Work–family resources and outcomes). Organizational support and leadership (C3) also function as moderating factors.

Outcomes

Across clusters, job satisfaction (and life satisfaction) emerge as focal outcomes – explicitly in C4 (Gender, Satisfaction, and Job Satisfaction) and implicitly in C1 and C6 through outcome-related terms (outcomes, impact) (Cluster 1: Variables of Job Satisfaction, Cluster 4: Gender, satisfaction, and job satisfaction, Cluster 6: Work–family resources and outcomes).

Contexts/theoretical lenses

C2 captures structural and intersectional contexts (patriarchal norms, pay gap, ethnicity). C4 links gender and life satisfaction, bridging work and non-work domains (Cluster 2: Women, Work, and Structural Inequalities, Cluster 4: Gender, satisfaction, and job satisfaction).

Implication

This cross-cluster synthesis elucidates how antecedents and contextual factors operate through moderators and mediators to produce outcomes in women’s job satisfaction. It provides a structured analytical bridge from RQ3 to the evidence-derived research agendas presented in Conclusions.

Trends

The reviewed studies point to four key lines of development that are particularly relevant for guiding future research on women’s happiness and job satisfaction, thereby addressing Q4: What are the future research trends? Each of these areas is discussed below, incorporating the literature referenced in this article:

Deepening the gender–culture intersection

As the evidence suggests, the relationship between gender and job satisfaction varies according to cultural context, ethnicity, and socioeconomic structures (Hersch, Reference Hersch2023; Hwang & Hoque, Reference Hwang and Hoque2023). Various studies show that factors such as religion, patriarchal traditions, and local regulations can either exacerbate or mitigate the gender gap (Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023; Kalagy et al., Reference Kalagy, Abu-Kaf and Braun-Lewensohn2022; Saldías & Moyano, Reference Saldías and Moyano2023). Moreover, globalization and migration have led many working women to operate in culturally diverse contexts, which necessitates a better understanding of how these differences affect their job satisfaction.

In this regard, comparative and intersectional studies are needed, incorporating samples from different regions and demographic groups in order to identify the specific factors that influence women’s happiness at work (Hersch, Reference Hersch2023). Analysing variables such as ethnicity, social class, or rural/urban origin would offer deeper insight into the complexity of women’s experiences (Azima & Mundler, Reference Azima and Mundler2022).

Impact of digital transformation and remote work

The consolidation of remote work, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has reshaped the landscape of work-family balance (Feng & Savani, Reference Feng and Savani2020; Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023). While teleworking may offer greater autonomy and flexibility, it also carries the risk of blurring the boundaries between personal and professional life – especially for women, who tend to bear a greater share of domestic responsibilities, thereby reinforcing traditional gender roles (Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024; Orešković et al., Reference Orešković, Milošević, Košir, Horvat, Glavaš, Sadarić and Orešković2023).

Future research should focus on identifying organizational factors that foster the positive use of digital tools, avoiding excessive workloads and the perpetuation of gender stereotypes (Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023; Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023).

Mental health and a holistic approach to satisfaction

Work overload and the ‘double presence’ of women – in both professional and domestic spheres – have been consistently associated with higher risks of stress, anxiety, and depression (Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024; Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023). This psychological distress has a negative impact on work performance and overall quality of life for women (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Cruz and Belim2025). This scenario calls for a holistic approach that addresses not only improvements in working conditions (e.g., more balanced schedules, shared domestic responsibilities) but also the implementation of professional support programmes and peer support networks (Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023).

From an organizational standpoint, studies suggest introducing mentoring or coaching strategies, in which experienced professionals support younger women or those with greater caregiving responsibilities (Hennein et al., Reference Hennein, Gorman, Chung and Lowe2023). Additionally, providing spaces for sharing experiences and challenges, along with developing corporate policies focused on preventing burnout, is essential to mitigate the effects of female work overload (Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023; Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023). At the same time, there is a need to reformulate certain sociocultural standards that continue to view women as the primary caregivers (Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024).

New approaches to measuring happiness and satisfaction

Authors such as Serrano et al. (Reference Serrano, Navarro and González2022) propose incorporating qualitative and mixed methodologies into the measurement of these concepts in order to capture women’s subjective experiences in diverse contexts. This would allow researchers to detect nuances related to emerging forms of sexism (such as ‘reverse sexism’) and to evaluate how these dynamics impact job satisfaction (Morando et al., Reference Morando, Zehnter and Platania2023).

Implications for management

The findings of this review have significant implications for organizational management, particularly regarding the design of more equitable, sustainable, and gender-sensitive work environments. First, the evidence shows that women’s job satisfaction cannot be addressed in isolation; it must be integrated into a holistic vision that considers the intersection of working conditions, patriarchal structures, and gender roles (Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024; Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024). Accordingly, human resources departments must move beyond gender-neutral approaches and develop strategies that explicitly acknowledge the domestic and emotional overload that disproportionately affects women (Giurge et al., Reference Giurge, Whillans and Yemiscigil2021; Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023).

One such strategy should involve implementing co-responsible work-life balance policies. These should not only offer flexible hours or teleworking options, but also include institutional support systems such as childcare services, equal parental leave, and regulated digital disconnection mechanisms (Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023; Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023). These policies must be designed using a ‘responsible flexibility’ approach, avoiding the risk of turning them into an additional burden for women – as has occurred in many cases following the widespread adoption of telework during the pandemic (Feng & Savani, Reference Feng and Savani2020).

Furthermore, recognizing the impact of emotional well-being on productivity highlights the urgency of integrating mental health programmes into organizational culture. Companies should promote a supportive psychosocial environment, including peer support networks, gender-sensitive mentoring, and access to emotional management resources (Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023; Hennein et al., Reference Hennein, Gorman, Chung and Lowe2023). These efforts contribute to improved job satisfaction while reducing absenteeism, burnout, and staff turnover (Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024; Nappo & Lubrano Lavadera, Reference Nappo and Lubrano Lavadera2024).

From a strategic perspective, organizations must recognize that women do not constitute a homogeneous group. Variables such as race, sexual orientation, disability, or migration status intersect with gender to create distinct inequalities (Abu-Kaf et al., Reference Abu-Kaf, Kalagy, Portughies and Braun-Lewensohn2023; Hersch, Reference Hersch2023). Therefore, designing effective inclusion policies requires intersectional organizational diagnostics and the use of gender- and diversity-sensitive indicators.

Additionally, there is a need to review performance evaluation, promotion, and compensation systems. The literature reviewed warns that women continue to face glass ceilings and systemic biases that hinder their access to leadership positions, which affects both motivation and well-being (Milovanska-Farrington & Farrington, Reference Milovanska-Farrington and Farrington2022; Morando et al., Reference Morando, Zehnter and Platania2023). Promoting salary transparency, inclusive career development plans, and female leadership contributes not only to equity but also to organizational innovation and sustainability (Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023).

Finally, it is recommended to foster an organizational culture that actively challenges gender stereotypes. This includes mandatory equality training, accessible reporting mechanisms, and affirmative actions that promote the representation of women at all hierarchical levels (Azima & Mundler, Reference Azima and Mundler2022). As the evidence shows, an inclusive culture not only increases the satisfaction and engagement of female employees but also has a positive impact on the organization’s overall performance (Erdogan et al., Reference Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo and Mansfield2012; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Rafiq and Chin2017).

Conclusions

Following this bibliometric review on the happiness of working women, several conclusions can be drawn that help to further understand this field of study.

First, it is important to highlight the marked fragmentation observed in the scientific output within this area. This can be interpreted as a sign that, despite growing interest, the field still lacks the consolidated academic foundations that typically emerge when a subject reaches more mature stages of development. In bibliometric analysis literature, this phenomenon is associated with the absence of ‘core authors’ whose work guides future trends (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021). This dispersion of contributions may be attributed to the emerging and multidisciplinary nature of the topic, the lack of specialized academic networks, or the fact that many authors approach the subject sporadically.

Second, the analysis of women’s job satisfaction cannot be separated from patriarchal structures and gender roles, which continue to assign the majority of reproductive and caregiving work to women (Dethier et al., Reference Dethier, Stevens and Boden2024; Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023). These structures perpetuate the double burden and hinder full professional development, as domestic responsibilities compound with work demands, negatively affecting women’s mental health and workplace experience (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Cruz and Belim2025; Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024). Additionally, persistent stereotypes, sexist attitudes, and discrimination in many sectors undermine well-being and limit women’s participation in decision-making spaces (Morando et al., Reference Morando, Zehnter and Platania2023). In this sense, the patriarchal structure not only directly impacts women’s workplace happiness but also reinforces both symbolic and material barriers that limit their professional advancement and work-life balance (Hwang & Hoque, Reference Hwang and Hoque2023).

A third fundamental aspect concerns the intersection of gender, race, class, and sexual orientation – variables that, when overlapping, exacerbate inequality. Studies on Afro-descendant women or those from ethnic minorities show lower levels of job satisfaction, often linked to multiple forms of discrimination, job insecurity, and limited organizational support (Hersch, Reference Hersch2023). Similarly, social class and sexual orientation emerge as factors that can widen equity gaps by restricting access to high-responsibility roles or better working conditions (Abu-Kaf et al., Reference Abu-Kaf, Kalagy, Portughies and Braun-Lewensohn2023). This scenario becomes even more complex in sociocultural contexts where patriarchal values are deeply rooted, and where women are often subject to legal and traditional constraints that hinder their professional development (Barequet et al., Reference Barequet, Rosenblatt, Schaap Fogler, Pedut-Kloizman, Gaton, Loewenstein and Habot-Wilner2023; Sjølie et al., Reference Sjølie, Akin and Lauritzen2023).

Fourth, it is important to emphasize the contribution of this review to the field of feminist and labour studies. The bibliometric analysis reveals that, while there is a notable diversity of perspectives, few studies address women’s job satisfaction from an intersectional and holistic standpoint (Hwang & Hoque, Reference Hwang and Hoque2023). Consequently, this review suggests the need to build bridges between disciplines – Economics, Psychology, Sociology, and Gender Studies – and to intensify research from a feminist perspective in order to shed light on how power dynamics and patriarchal norms shape women’s workplace experiences (Morando et al., Reference Morando, Zehnter and Platania2023).

Finally, from a feminist standpoint, several strong recommendations emerge. First, there is an urgent need to implement more equitable labour policies, such as parental leave that is not limited to mothers but instead promotes fathers’ shared responsibility in caregiving tasks (Hennein et al., Reference Hennein, Gorman, Chung and Lowe2023). Second, continued progress is needed in reducing the gender pay gap by promoting transparency in salary scales and penalizing discriminatory practices (Milovanska-Farrington, Reference Milovanska-Farrington2023). Third, the redistribution of caregiving duties remains a major challenge to achieving genuine work-life balance. Measures such as tax incentives for hiring care services or the establishment of childcare facilities within organizations are proposed as potential solutions (Sukri et al., Reference Sukri, Ngah and Yiaw2023).

Limitations

This article is not without limitations, and the authors are fully aware of them. The WoS-only decision prioritizes metadata consistency and quality over breadth of coverage. We acknowledge that this choice may underrepresent certain parts of the scholarly output (e.g., regional or non-English-language journals) and that indicators may vary if another source or a multi-database design were used. Consequently, the conclusions should be interpreted as relative patterns within the WoS universe – appropriate for conceptual mapping and performance analysis – while not exhaustive of the entire documentary ecosystem. (Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Reference Mongeon and Paul-Hus2016).

Furthermore, the use of the Boolean operator NEAR/7 in the search query restricted the retrieved articles to those in which the search terms occurred within seven words of each other. While this choice enhanced semantic precision, it may also have excluded potentially relevant studies. Nevertheless, this decision was made to ensure alignment between the search strategy and the specific objectives of the study. In addition, the co-occurrence threshold set at five and the removal of duplicates influenced the overall network topology, particularly cluster size and the visibility of less frequent terms.

Regarding the tools, VOSviewer applies normalization based on association strength and modular clustering algorithms – well-established practices that are, however, subject to certain limitations: (a) variations in counting methods (full vs. fractional counting), which may bias the relative centrality of authors or countries; and (b) the well-documented resolution limit of modularity, whereby smaller communities may be merged into larger clusters. To mitigate these risks, we report all parameter settings, interpret clusters with caution, and consider sensitivity analyses and cross-validations as potential extensions for future research. (Perianes-Rodríguez, Waltman & Van Eck, Reference Perianes-Rodríguez, Waltman and Van Eck2016)

On the other hand, we acknowledge that a narrative SLR or a meta-analysis could provide in-depth assessments of methodological quality and syntheses of effects, respectively. However, these approaches would be less suitable for reconstructing the thematic architecture and research trajectories of large and heterogeneous corpora – precisely the distinctive contribution of the bibliometric approach adopted here. We therefore propose, as future research directions, combining this mapping with qualitative or mixed-method SLRs focused on specific subtopics (Snyder, Reference Snyder2019).

Finally, the threshold for keyword co-occurrence was set at five, resulting in a total of 102 terms, which were reduced to 97 after data refinement. Although this is a substantial number, it may have slightly distorted the outcomes regarding word relationships and cluster formation. Initially, a co-occurrence threshold of six was considered, which would have produced more concise results, but the decision was ultimately made to use five in order to capture a broader range of connections.

Integrative synthesis and conceptual framework

The performance indicators and disciplinary distribution (Figs. 2–4; Citation and publication analysis, Analysis by journals) evidence a growing scholarly interest coupled with marked fragmentation, thereby addressing RQ1. The authorship and citation analyses (Fig. 5; Authorship and citation analysis) reveal the absence of core authors and a recent discontinuity among the most prolific contributors, responding to RQ2 and illustrating the field’s developmental immaturity. The co-occurrence map and cluster descriptions (Figs. 6–7; Keyword analysis, Cluster analysis) demonstrate how research on women’s job satisfaction is interconnected with work–family conflict and mental health, directly informing RQ3. Finally, the Trends subsection (Trends) – explicitly linked to RQ4 – and Conclusions (Future Research Directions) translate these mapped patterns into substantive research agendas encompassing intersectionality, digital transformation and remote work, mental health, and feminist or critical metrics.

Provenance of the synthesis and links to Conclusions

The research agendas subsequently articulated in Conclusions stem from three converging strands of evidence: (i) the co-occurrence neighbourhoods surrounding job satisfaction, which prominently feature work–family conflict and mental health (Figs. 6–7; Keyword analysis, Cluster analysis); (ii) cluster-specific emphases and research gaps (e.g., Clusters 5–6); and (iii) field-level indications of fragmentation and the absence of core authors identified through RQ1–RQ2.

Building on these patterns, we propose an integrative conceptual framework wherein structural and contextual determinants shape organizational enablers and constraints, which in turn condition individual experiences that ultimately influence women’s job satisfaction and its associated outcomes.

Future research directions

The research directions below are evidence-derived from co-occurrence neighbourhoods (Figs. 6–7), cluster emphases/gaps (Keyword analysis, Cluster analysis), and field-level fragmentation signals from RQ1–RQ2 (Citation and publication analysis, Analysis by journals, Authorship and citation analysis), as synthesized in a respective section.

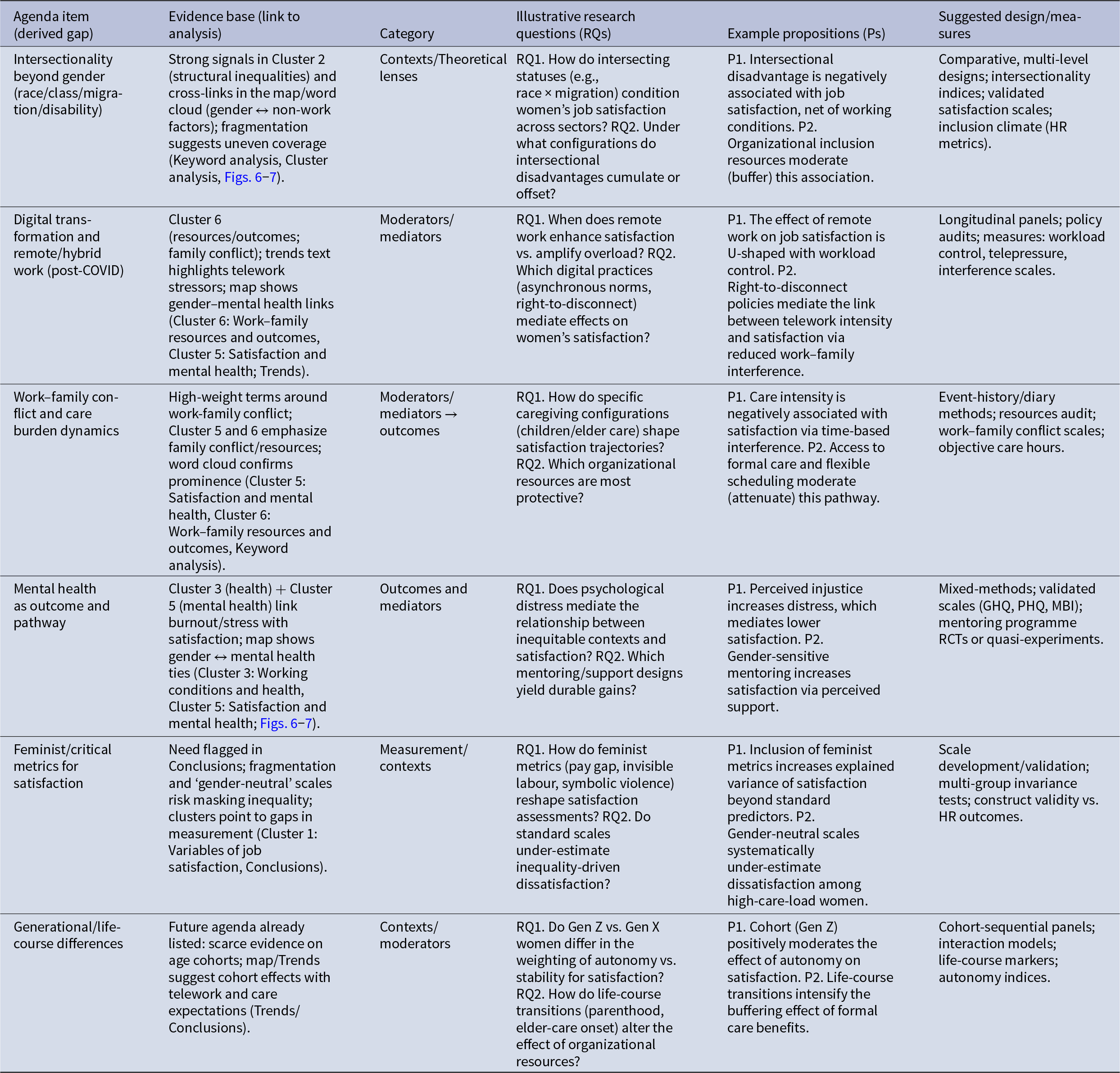

The folloing Table 1 presents a future research agenda logically derived from a critical analysis of the literature, which systematically identifies and categorizes key knowledge gaps and proposes stimulating questions and propositions to guide subsequent studies.

Table 1. Evidence-derived research agenda for women’s job satisfaction

Based on the findings of this review, several lines of research are proposed, ideally to be developed through case studies that could deepen our understanding of women’s job satisfaction:

1. Exploring the impact of intersectionality. Although the literature acknowledges the influence of race, class, and sexual orientation, more empirical studies are needed to analyse how these variables interact and generate different patterns of satisfaction and disadvantage (Hersch, Reference Hersch2023).

2. Assessing the influence of digital transformation and remote work. The rise of remote work raises questions about its effects on women’s autonomy and mental load (Feng & Savani, Reference Feng and Savani2020; Lu & Zhuang, Reference Lu and Zhuang2023). It is essential to investigate the conditions under which telework becomes a source of empowerment or, conversely, reinforces overload and the invisibility of the double burden.

3. Further analysis of women’s mental health. Overexposure to stress, lack of familial support, and patriarchal demands threaten women’s emotional well-being (Matud et al., Reference Matud, Sánchez-Tovar, Hernández-Lorenzo and Cobos-Sanchiz2024; Mentus & Zafirović, Reference Mentus and Zafirović2023). Longitudinal studies would be valuable to assess the effectiveness of burnout prevention programmes or mentoring networks across different professional sectors.

4. Integrating feminist metrics and perspectives into the measurement of satisfaction. It is recommended to design tools that incorporate dimensions such as the gender pay gap, work-life balance, and symbolic violence. These metrics should better capture women’s subjective experiences, rather than reproducing a gender-neutral approach that conceals inequality (Morando et al., Reference Morando, Zehnter and Platania2023; Serrano et al., Reference Serrano, Navarro and González2022).

5. Generational differences. It would also be important to explore generational differences in women’s job satisfaction. Very little research examines the workforce – and especially women – based on their generational cohort. As a result, findings are often generalized and treat ‘women’ as a homogeneous category. It would be both interesting and essential to understand what contributes to job satisfaction among women belonging to different generations: Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, and Gen Z.

Acknowledgements

Funding for open access charge by Universidad de Málaga / CBUA.

Conflict(s) of interest

The authors declare none.

Isaac Albarracín is a PhD candidate in Business and Management at the University of Granada (UGR). He is developing his doctoral dissertation on Happiness Management, with a focus on gender and generational perspectives. His research combines management, organizational psychology, and innovation to explore how workplace happiness drives performance, engagement, and employee retention. With over 3,000 hours of teaching and training experience, his work is characterized by the integration of Design Thinking, Gamification, and LEGO® Serious Play® into organizational contexts. He is an active researcher, presenting at international conferences such as the Academy of Management (AOM), and contributing to the emerging field of workplace happiness.

Jesús Molina-Gómez is a professor in the Department of Economics and Business Management at the University of Malaga (UMA). He received his PhD in Economics and Business Management from UMA Málaga and is an expert in management and marketing with over 25 years of experience in the consulting sector. With over 3.500 teaching hours, his work is distinguished by its multidisciplinary nature. He is an active researcher with over 25 publications in top-tier journals and books, focusing on areas like emotional competence, human resources, sustainability, and internal marketing. His studies have been published in peer-reviewed journals such as Eurasian Business Review, Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, Plos One, Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, among others. Furthermore, he demonstrates leadership through his direction of university chairs in FinTech, supervision of undergraduate and master’s theses, and his role as a member of the Board of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management.

Pere Mercadé-Mele is an associate professor in the Department of Economic Structure at the University of Málaga, Málaga, Spain. He received his PhD in Economics and Business Management from the University of Málaga. His current research interests include corporate social responsibility management, tourism, and consumer behaviour. His studies have been published in peer-reviewed journals such as Tourism Management Perspectives, Agribusiness, Eurasian Business Review, British Food Journal, Journal of Business Economics and Management, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, among others.

José M. Nuñez-Sánchez is a professor in the Department of Economics and Business Management at the University of Malaga (UMA). He received his PhD in Economics and Business Management from UMA Málaga and is an expert in management and marketing with over 25 years of experience in the wellness sector. With over 2,500 teaching hours, his work is distinguished by its multidisciplinary nature. He is an active researcher with over 20 publications in top-tier journals and books, focusing on areas like internal marketing, corporate well-being, and organizational happiness. Furthermore, he demonstrates leadership through his direction of university chairs, supervision of undergraduate and master’s theses, and his role as a member of the Board of the World Happiness Foundation.