1. Devolution and fiscal rules

Alesina and Spolaore (Reference Alesina and Spolaore1997) set out a simple model that highlights some of the complexities of devolution and funding. In their model, country size is a trade-off between economies of scale (larger countries can have lower taxes as government is more efficient) and ‘distance’ from government (‘distance’ should be broadly interpreted as distance in preferences, but since they assume physical distance and preference distance are correlated, it can in this case be thought of as physical distance). Given this trade-off, they can solve for optimal country size (i.e. as chosen by the benign social planner). However, they also find that, if left to individuals within that country to choose, country size will be smaller than optimal. This is because those most distant from government may be prepared to give up scale efficiencies to have a less distant government, but that decision will have an externality as it also reduces scale efficiencies for those less distant. Given this externality, Alesina and Spolare suggest that a fiscal transfer from the centre to the periphery can be used to maintain optimal country size. This may imply that fiscal rules for devolved nations should involve some form of fiscal transfer to the periphery, and indeed, there is evidence that such transfers have historically occurred between England and Scotland in the form of higher funding per head in Scotland.

2. Scotland’s first framework: the Goschen formula

In 1888, in the (extended) run-up to Irish home rule, the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Goschen came up with a formula to allocate funding to Ireland, Scotland and the rest of the UK—9%, 11% and 80%, respectively. The precise reasoning behind Goschen’s split between Ireland, Scotland, and the rest of the UK is not clear, but it is most commonly assumed to bear some relation to probate tax revenues (see Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2003). In practice, however, the 11/80 split between Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom (rUK) was very close to the population shares measured at the time (13.9%)Footnote 1.

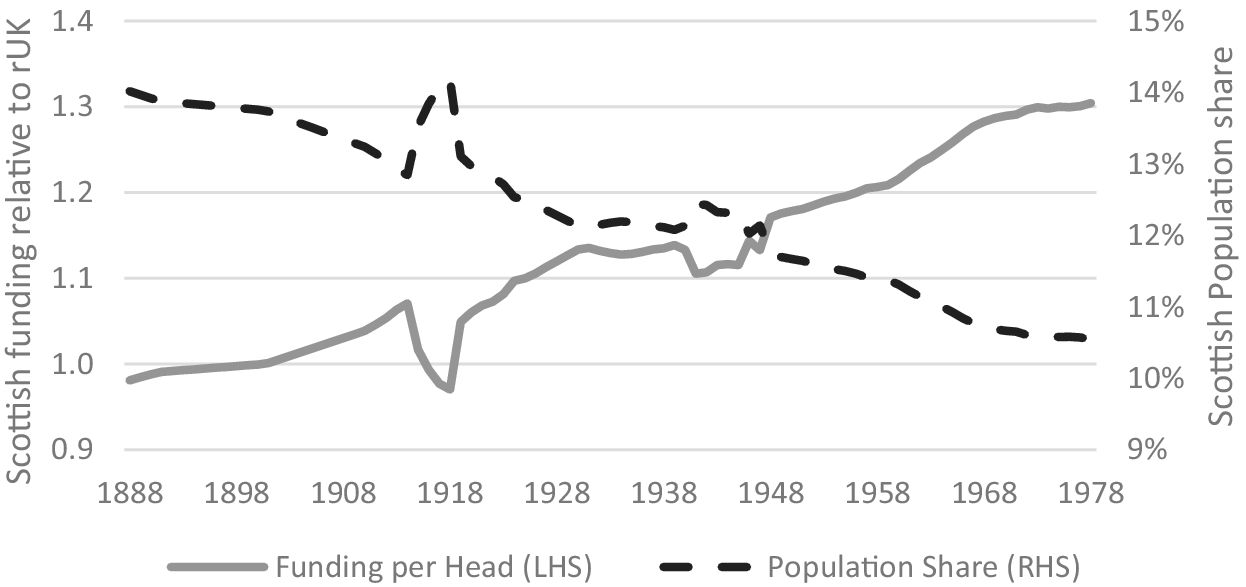

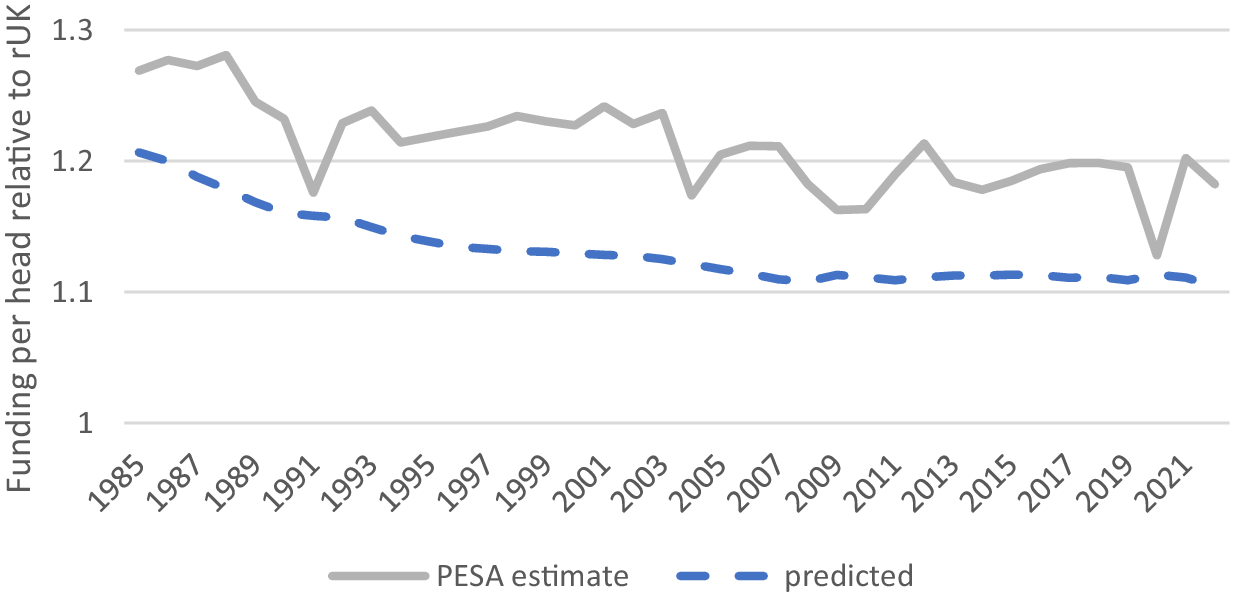

Although mainly focused on education spending, the Goschen formula tended to be the starting point for all negotiations on funding splits for the next 90 years, even after it was officially dropped in the 1950s. However, over this period, there was a steady decline in Scotland’s share of the UK population due largely to differences in net migration. Figure 1 shows how Scotland’s shrinking population share meant that the 11/80th split became increasingly generous (in terms of funding per head).

Figure 1. Scotland’s population share and Goschen implied funding per head (1888–1978).

3. Scotland’s current framework: the Barnett formula

Although the Goschen Formula was still used as a guide even after it was dropped in 1957, the prospect of a devolution referendum and the growing arguments over funding decisions led the UK Treasury to seek a new funding formula. Although probably devised by Treasury official Sir Leo Pliatsky it became known as the Barnett formula after Joel Barnett—the Chief Secretary to the Treasury at the time. All evidence suggests that it was only meant as a temporary measure to reduce haggling over spending allocations, but—like the Goshen Formula before it—it has continued in operation well beyond its expected lifespan.

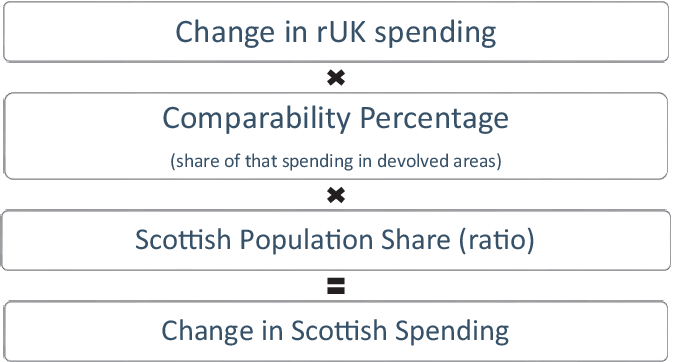

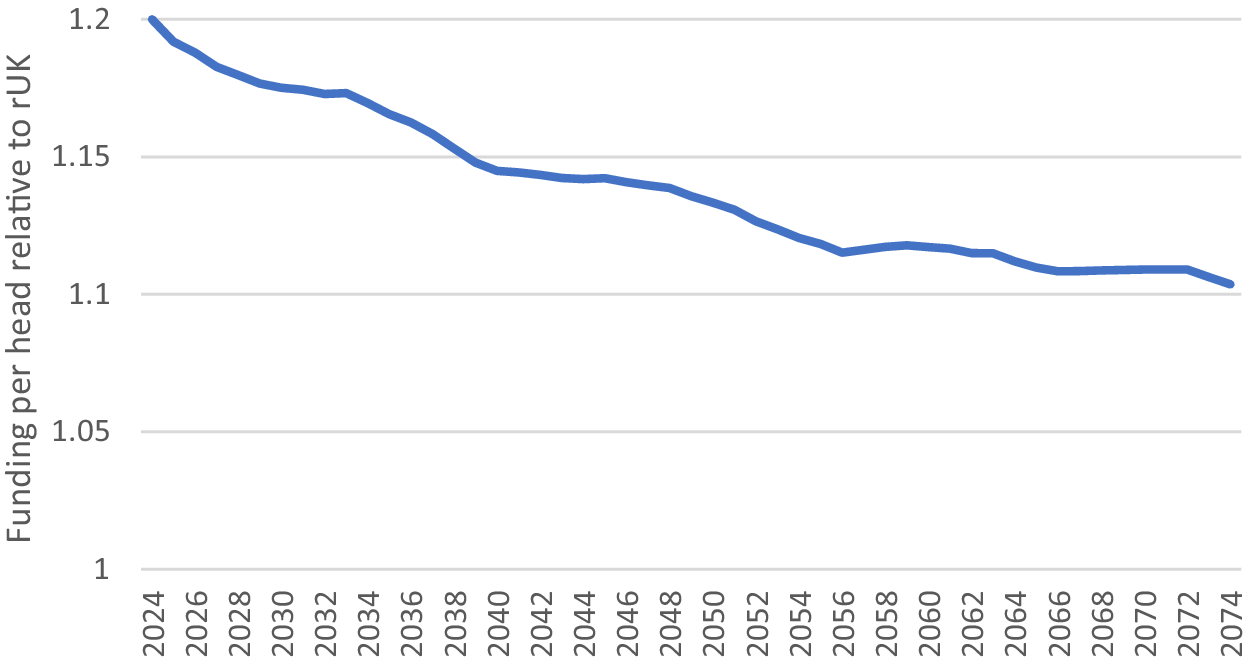

The formula, shown in Figure 2, seems fairly simple—any change in rUK (or just England in some cases) funding results in the same per capita funding change in Scotland unless that change is in a reserved area (e.g. defence) which has not been devolved (the comparability percentage). Despite this apparent simplicity, it has three key features that have caused both controversy and confusion. The first is that the formula is based on delivering per capita spending levels that are equal across Scotland and the rUK and thus significantly less funding for Scotland than the Goschen formula delivered. Second, it applies to changes in funding rather than the level of funding, so once implemented did not result in an immediate alignment of Scottish funding per head with that of the rUK but a gradual one as increases in the total size of the UK budget (due largely to inflation) resulted in a larger share of total funding being determined by the formula. Finally, although many areas of reserved spending are straightforward, a number have been controversial (e.g. funding for the London Olympics was allocated as reserved, effectively making the devolved nations contribute to its funding)Footnote 2.

Figure 2. The Barnett formula.

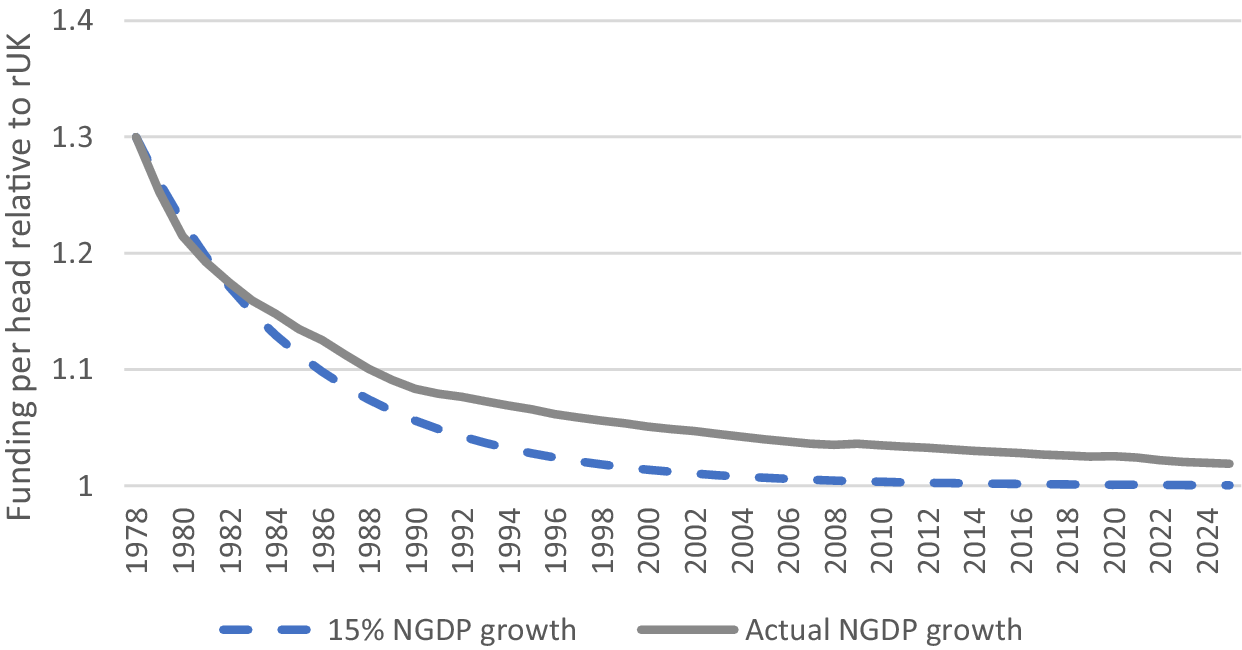

3.1. The Barnett squeeze

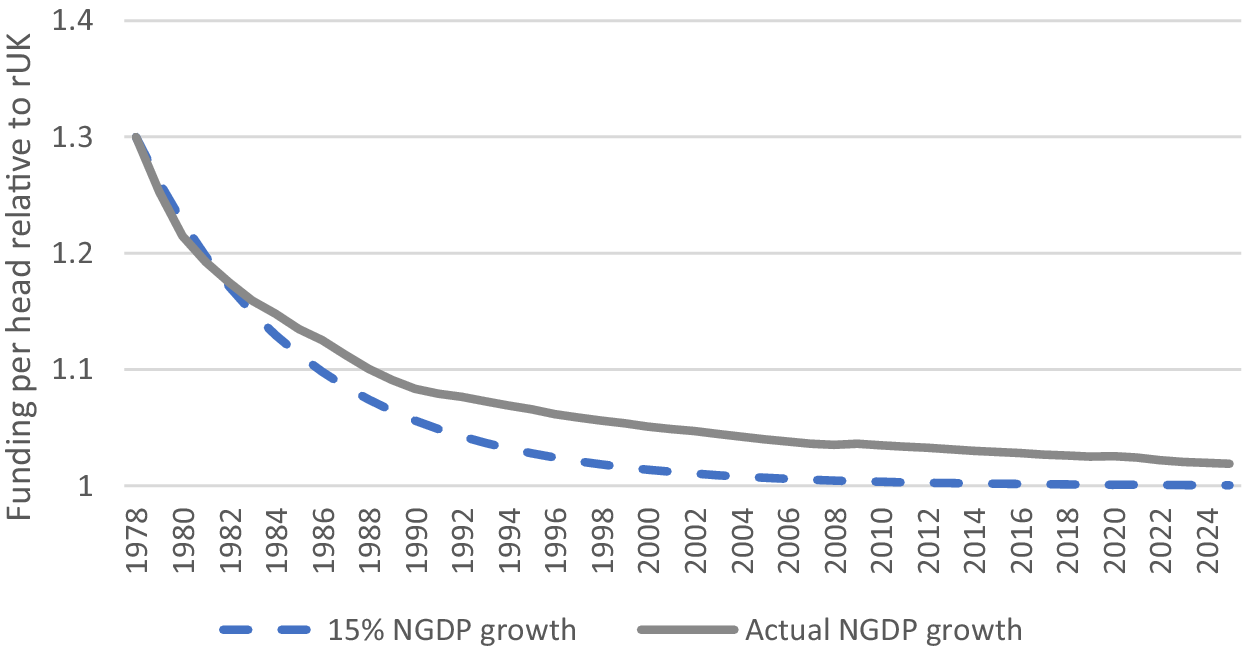

As noted above, since the Barnett formula applies to changes (i.e., increases) in funding rather than the level, its impact on the overall balance of funding between Scotland and rUK is not immediate but depends, amongst other things, on how fast the budget grows over timeFootnote 3. Given that, by the 1970s, the Goschen formula implied Scottish funding per head was about 130% of that in England and Wales, whilst the Barnett formula implies equal funding per head it is clear that the formula has a tendency to reduce Scotland’s share of funding, but the speed at which this occurs depends on how fast the budget grows in nominal terms.

Figure 3 shows two estimates of the convergence of Scottish and rUK funding per head (in non-reserved areas) that the simple application of the Barnett formula should have produced. The first shows the convergence that could have occurred if nominal GDP growth had continued at its 1970s average (i.e. the rate of convergence that might have been expected when the formula was introduced) whilst the second is based on nominal GDP growth that actually occurred. In both cases, government spending is assumed to be a fixed share of nominal GDP, and that funding starts at the 130% level predicted by the Goschen formula.

Figure 3. The Barnett squeeze.

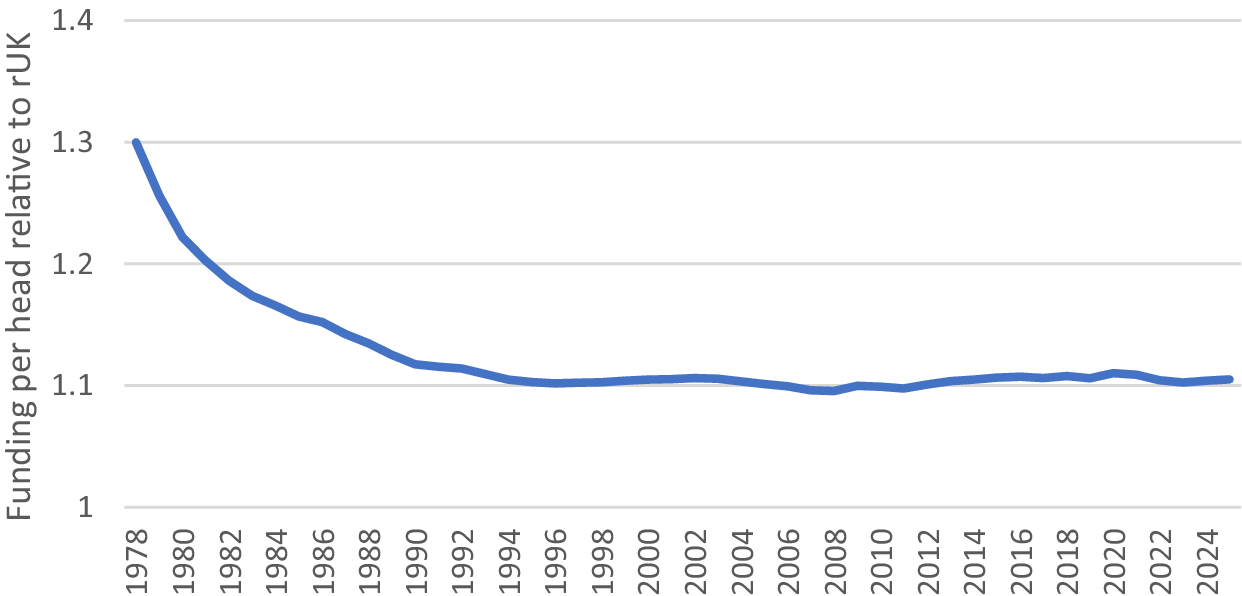

3.2. Barnett and population share

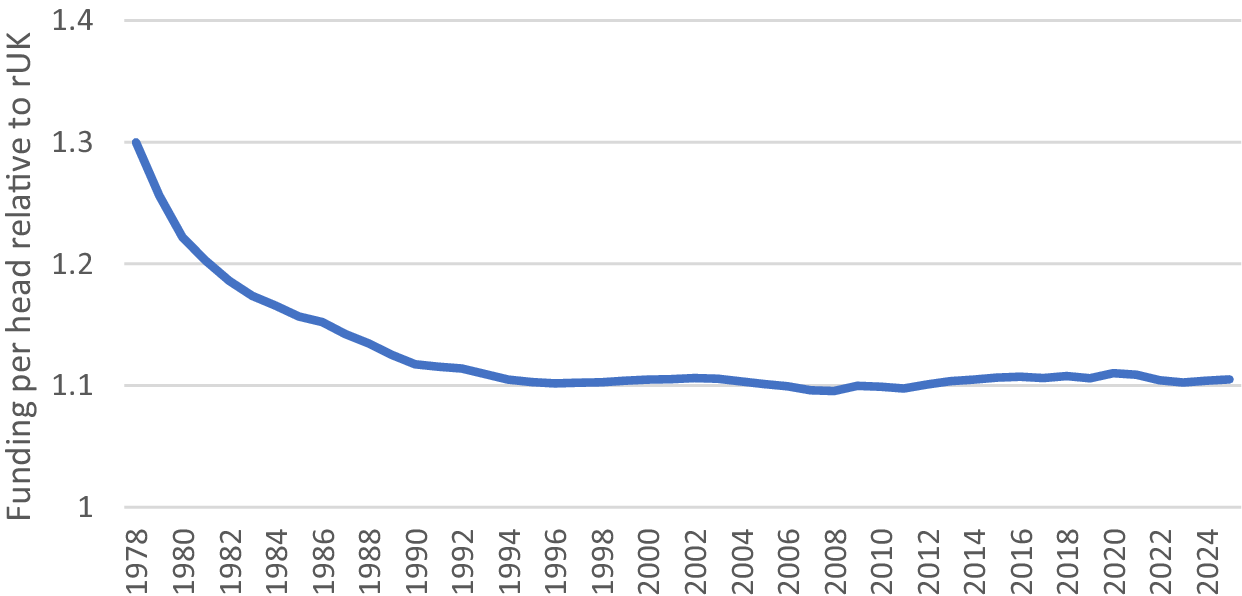

A second—probably unanticipated—effect of applying the Barnett formula to changes in funding rather than their level is that trends in population can affect the level of funding per head. Thus, in the case of Scotland, which has had a steadily falling share of the total UK population at the rate of about 0.03 percentage points per year, the Barnett formula will tend to deliver more funding per head in Scotland than the rUK, counteracting the Barnett Squeeze. The reason this occurs under Barnett is that the higher level of funding Scotland received when its population share was higher is not reduced as the population share falls, as only changes in funding are allocated at the new lower population share. Thus, with a steadily declining population share, Scotland’s funding per head can remain higher than the rUK, though the extent of that higher funding will also depend on how fast the budget is increasing, so higher inflation will tend to erode the population effect, as a fast-growing budget will make changes in funding a larger share of the total budget. Figure 4 shows the Barnett Squeeze based on actual nominal GDP growth and population trends (as before, government spending is assumed to be a fixed share of nominal GDP, and relative funding per head starts at 130%).

Figure 4. Barnett squeeze adjusted for falling population share.

As the chart indicates, the Barnett Squeeze is still quite significant in the early years, but funding converges at about 110% of rUK levels as the population effect creates a persistent (for as long as the population share keeps declining) funding advantage for Scotland (see Heald, Reference Heald1994 for a more in-depth analysis of the dynamics of the Barnett Formula).

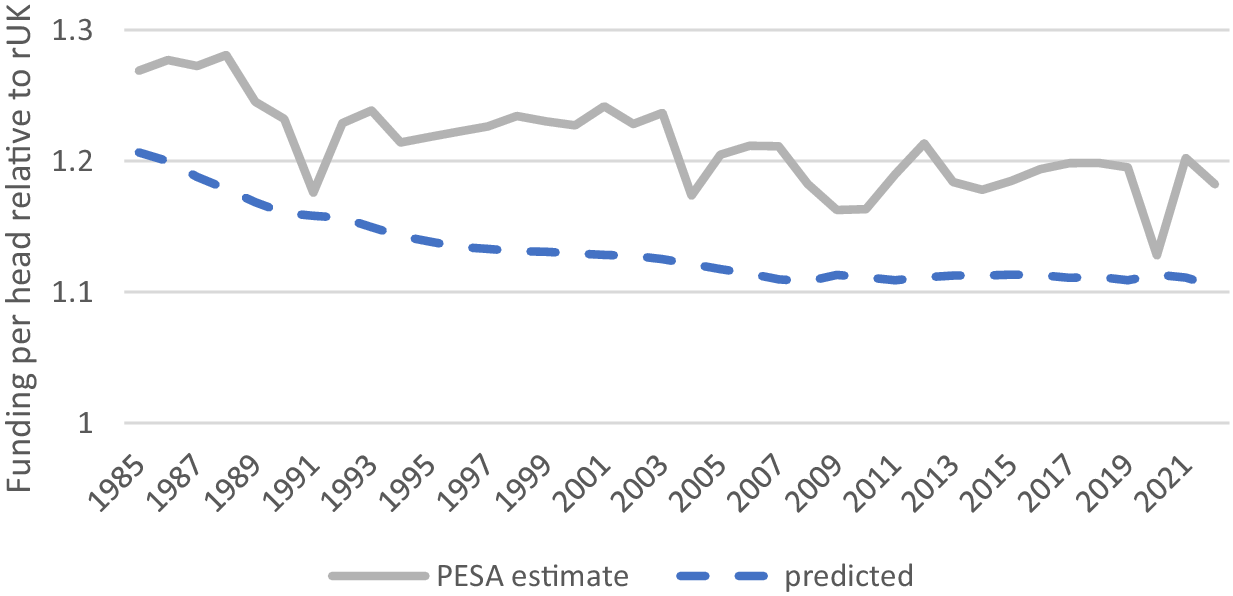

3.3. Barnett in practice

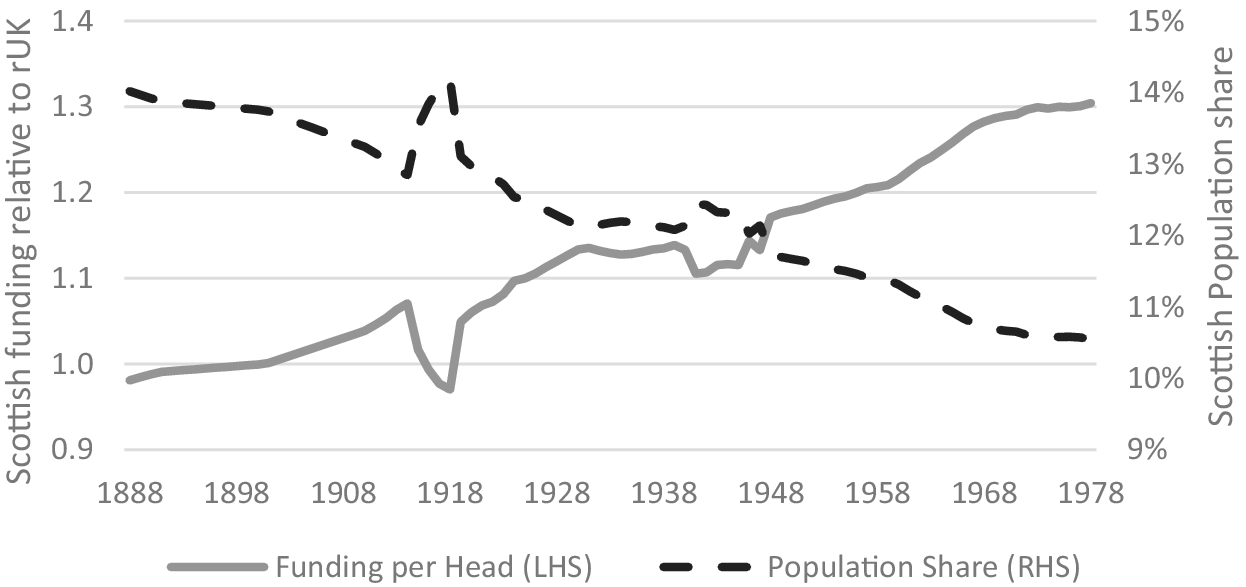

Despite the logic of the Barnett Squeeze, most evidence suggests that Scotland has maintained much higher funding per head than the formula would imply (even allowing for the population effect) although the comparison is not straightforward. Figure 5 compares the predicted path of Scottish funding per head relative to the rUK with an estimate of actual funding per head from various editions of the Treasury’s public expenditure statistical analysis (PESA) document.

Figure 5. Actual and predicted relative funding per head.

As Figure 5 shows that whilst actual Scottish funding per head has shown some tendency to converge with the rUK as predicted by the Barnett squeeze, that convergence is far less than would be expected if the Barnett formula had operated precisely as expected. There are probably two reasons for this. First, over most of its operation, the Barnett formula has only been used as a guide rather than a precise allocation process and there have been a number of cases of ‘formula bypass’ whereby funding decisions have been made using different criteria. For example, for the period up until 1992, the Scottish population share used in the formula was not updated, so it did not allow for a falling population share. This resulted in a two percentage point improvement in Scotland’s relative funding per head compared with the correct application of the formula. Second, the comparability ratio has not always been applied as might be expected, and so Scotland has perhaps been protected from some changes in rUK spending. For example, for an extended period, devolved nations were protected from the squeeze on central government funding to English local authorities but effectively benefited from the reallocation of spending this allowed to other, devolved, areas. Again, this resulted in about a 2% gain in funding (see Phillips, Reference Phillips2014).

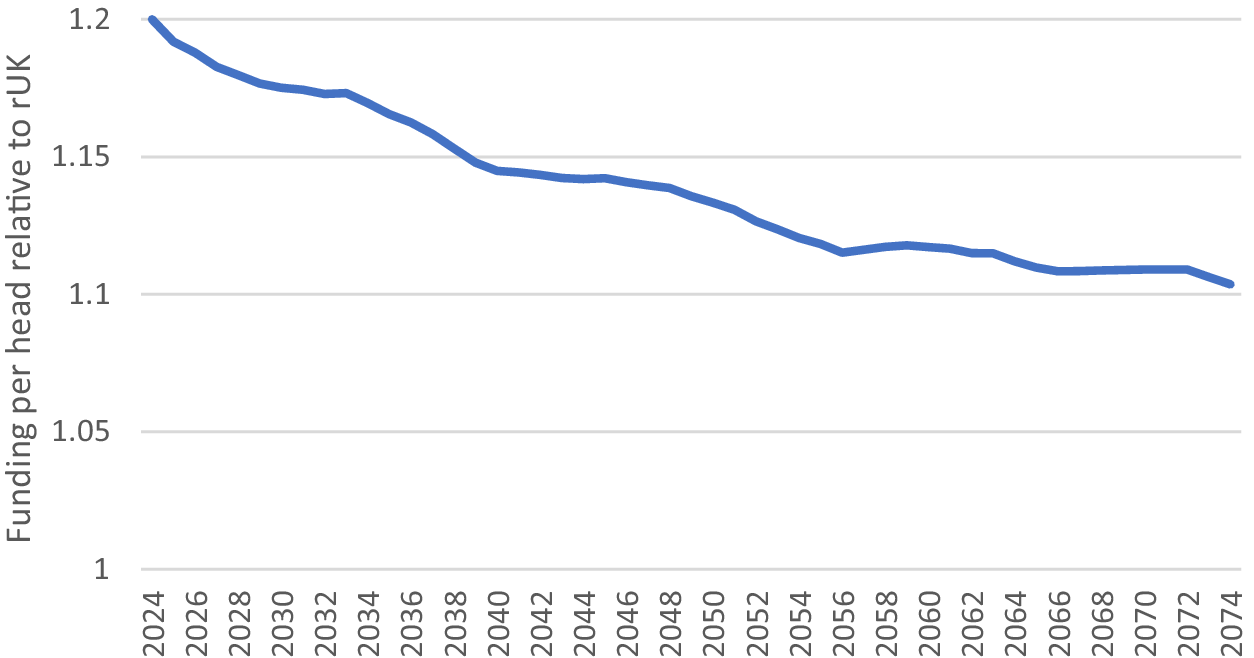

4. Scottish funding in the future

Whilst it is hard to pinpoint each occasion on which the Barnett formula was bypassed, what is very likely to be the case is that these events have become less frequent (if they have occurred at all) since the new fiscal framework was implemented in 2016. This is because the new framework, despite notionally reducing the role of the Barnett formula, has made the funding formula far more mechanical and rules-based than in the past, thus making bypass events much less likely. As a result, the Barnett squeeze has probably already begun to assert itself more strongly—though so far it has been offset by higher taxes in Scotland (resulting in an improved ‘net position’ in the new framework). However, given that the Scottish population share is projected to continue its trend decline, Scottish block grant funding is likely to eventually converge on spending per head in Scotland of around 110% of the rUK level (assuming nominal GDP growth of 4% p.a.). Of course, the Scottish government can try to continue to offset this Barnett Squeeze effect by increasing devolved tax revenue per head in Scotland, but this is not without its own problems.

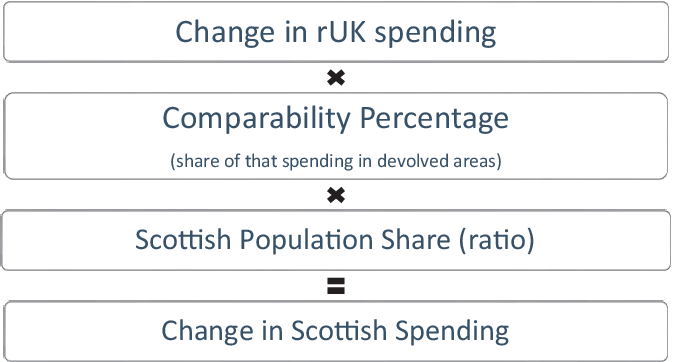

On the basis that current Scottish funding per head stands at about 120% that of the rUK, Figure 6 presents an illustrative path of relative funding per head over the next 50 years on the following assumptions. First, no formula bypass or other deviations from Barnett will occur from now on. Second, the Scottish population share develops as predicted in the latest population projections. Third, that rUK spending grows at a nominal 4% p.a., and finally, that devolved tax revenue per head in Scotland is in line with the rUK. The path of relative funding shown in Figure 6 implies funding per head grows about 0.25% slower in Scotland than it does in the rUK over the next 20 years.

Figure 6. Projected relative funding per head.

5. Conclusion

For over 100 years, Scotland has operated with significantly higher funding per head than the rest of the United Kingdom, as would be predicted by Alesina and Spolaore (Reference Alesina and Spolaore1997). However, the size of that margin seems to have been determined almost by accident, largely due to the trend decline in the Scottish population share. Currently, it is likely that this margin will go through a period of considerable reduction—again as a presumably unanticipated side effect of other reforms. Although this potential decline in relative funding will be somewhat hidden in the mechanics of the fiscal framework, it could add significantly to existing fiscal pressure on the Scottish government, with Scottish funding per head growing more slowly than in the rest of the United Kingdom for many years.