Introduction

The COVID‐19 pandemic posed a significant challenge for governments worldwide, requiring an effective response to a rapidly evolving public health crisis. The success of public health measures and the overall response to a crisis like the COVID‐19 pandemic depends on high levels of public compliance and trust in public officials (Bargain & Aminjonov, Reference Bargain and Aminjonov2020; Jørgensen et al., Reference Jørgensen, Bor, Lindholt and Petersen2021). High levels of political trust have been shown to improve compliance, influencing outcomes such as vaccination rates, adherence to laws and regulations, and resilience to misinformation (Devine et al., Reference Devine, Valgarðsson, Smith, Jennings, Scotto di Vettimo, Bunting and McKay2023; Marien & Hooghe, Reference Marien and Hooghe2011). Political trust can be volatile during crises (Devine & Valgarðsson, Reference Devine and Valgarðsson2024),Footnote 1 which amplifies uncertainty and demands accountability as they directly impact citizens' lives and test leaders' abilities to respond effectively (Boin et al., Reference Boin, Ekengren and Rhinard2020). In democracies, leaders' crisis responses can significantly influence public support and even shape political careers (Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Nord and Falkheimer2015).

Communicative interventionsFootnote 2 by political leaders have proven essential for delivering key messages and sustaining public support.Footnote 3 An expanding body of research examines the influence of direct leader communication on public compliance and democratic attitudes. These studies have found that leader communication can affect, and in some instances even reduce, public compliance (Anderson & Hobolt, Reference Anderson and Hobolt2022). For example, President Bolsonaro's anti‐isolation speeches reduced compliance and increased mortality rates in Brazil (Ajzenman et al., Reference Ajzenman, Cavalcanti and Da Mata2020; Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Gagete‐Miranda and Rettl2020), President Macron's call for cooperative behaviour elevated people's willingness to comply (Anderson, Reference Anderson2023), and President Trump's tweets have been shown to have a similarly negative effect on compliance with stay‐at‐home orders in the United States (Bisbee & Lee, Reference Bisbee and Lee2022). The prevailing trend in the literature suggests a consistent effect in line with the message delivered by leaders, except for a notable exception found in the study by Wuttke et al. (Reference Wuttke, Sichart and Foos2024), where the authors found a null effect of pro‐democracy speeches on democratic attitudes.

In communicative interventions, the messenger's identity plays a crucial role (Kuipers et al., Reference Kuipers, Mujani and Pepinsky2021), along with the content of the message and the timing and context (Eisele et al., Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2021). Subgroups within the population can also have differentiated responses to such communication, as shown by Jørgensen et al. (Reference Jørgensen, Bor and Petersen2024), where a press conference decreased trust among unvaccinated individuals, while it remained high among vaccinated. In this paper, we examine whether communicative interventions effectively increase public support during crises, identify the groups most receptive, explore the mechanisms behind these effects and make suggestions into why some leader communications are more successful than others in generating political trust.

Empirically, we examine this by leveraging the quasi‐experimental event that occurred when the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, held a televised speech on 18 March 2020 directly communicating with the German people. In this speech, which was watched by more than 25 million German citizens,Footnote 4 Merkel referred to coronavirus as “Germany's greatest challenge since World War II” (Editorial, 2020a). For the first time in her 14 years in office, the Chancellor directly addressed the nation in a televised speech, in addition to her annual New Year address (Editorial, 2020c). Her speech has been referred to as ‘extraordinary’, ‘rare’, ‘one‐of‐a‐kind’ and ‘unprecedented’ across media outlets (Editorial, 2020b).

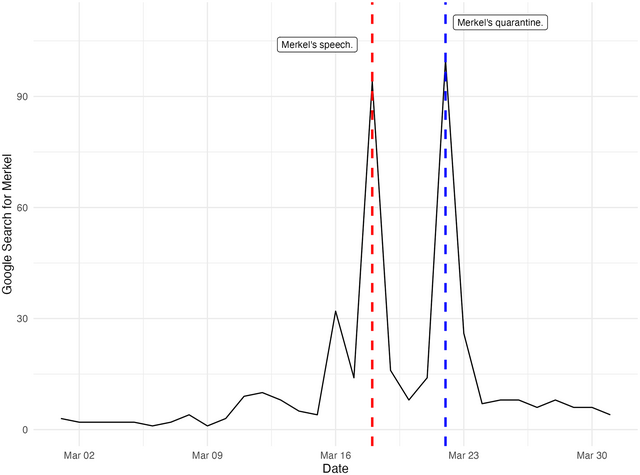

Figure 1 displays the Google search trends for March 2020 in Germany. The red line represents the date of Merkel's televised speech. Employing an unexpected‐event‐during‐survey design (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020), we find that Angela Merkel's speech is associated with a statistically significant 7 percentage point increase in public trust in federal institutions and a substantial reduction in nonresidential mobility of up to 25 percentage points. We rule out explanations such as lockdowns and other pandemic events as potential factors to account for these results. Using a causal forest approach, we show which subgroups of the population were more receptive to Merkel's speech. Additionally, we compare the content and effects of Merkel's speech with those of Mark Rutte and Boris Johnson, delivered around the same time, but do not observe similar effects from their speeches. This comparison highlights possible mechanisms driving the substantial increases in political trust following Merkel's address. The sentiment and automated communication analysis following Eisele et al. (Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2021) suggest that, compared to the speeches by Rutte and Johnson, Merkel's address emphasized solidarity and unity, with a notably positive sentiment, factors that may have strengthened its impact on public support.

Figure 1. Google search interest in ‘Angela Merkel’ in Germany.

Note: Search interest relative to peak interest (100). The red line indicates the day of Merkel's speech. The blue line marks the time when Merkel entered quarantine after her doctor tested positive. She tested negative a few days later. We later confirm the robustness of our results prior to this spike.

This study contributes to the literature in three primary ways. First, it advances research on political trust during crises (for a review, see, e.g., Devine et al., Reference Devine, Gaskell, Jennings and Stoker2021). Second, it builds on the expanding literature that examines factors in the formation of trust during the pandemic, such as government response to the crisis (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Sohlberg, Ghersetti and Johansson2021; Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Boulton and Scheffer2022; Toshkov et al., Reference Toshkov, Carroll and Yesilkagit2022), lockdowns (Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021; Schraff, Reference Schraff2021), external influences (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Bakker, Hobolt and Arceneaux2021) and perceptions of risk (Kritzinger et al., Reference Kritzinger, Foucault, Lachat, Partheymüller, Plescia and Brouard2021). Finally, it extends the literature on the role of political communication in sustaining public support in crisis (see, e.g., Anderson & Hobolt, Reference Anderson and Hobolt2022). Our research builds on existing work on if and how communicative interventions enhance political trust, while also expanding understanding by identifying responsive population subgroups and breaking down elements that might make political communication effective. In major crises, for example, pandemics, natural disasters, or terrorist attacks, effective communication is essential to secure the trust of citizens in government responses (Ajzenman et al., Reference Ajzenman, Cavalcanti and Da Mata2020; Brader & Tucker, Reference Brader and Tucker2012; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012; Samuels & Zucco, Reference Samuels and Zucco2014; Tesler, Reference Tesler2012). Our research highlights the potential of leaders to strategically use communicative interventions to build trust, with broader implications for crisis governance beyond pandemics.

Research Design

We conduct an unexpected‐event‐during‐survey‐design to identify the causal effect of the then German Chancellor Angela Merkel's speech on citizens' political trust and compliance (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó‐Gimeno and Hernández2020). Merkel addressed the nation on 18 March 2020, in a 12‐minute speech, to explain the measures the government was taking to combat the coronavirus pandemic. Emphasizing the importance of slowing the spread of the virus, she urged all citizens to do their part in preventing its spread by limiting public interaction and following hygiene measures. She said, ‘I truly believe that we will succeed in the task before us, so long as all the citizens of this country understand that it is also their task’. Further, she stated, ‘I want to tell you why we need your contribution and what each and every person can do to help’. Merkel concluded by urging everyone to follow the government's guidelines and take care of themselves and their loved ones.Footnote 5

Since Angela Merkel's speech was unexpected, unannounced, and highly salient (see Google trends in Figure 1 and Twitter trends in Online Appendix Figure G.1), it is reasonable to assume that the timing of each interview is as good as random with respect to the timing of Angela Merkel's televised speech.

The survey

We rely on Wave 46 of the German Internet Panel (GIP) which was fielded between 1 and 31 March 2020 to conduct the unexpected events during survey design. The GIP collects panel data on individual attitudes and preferences, which are important for political and economic decision‐making, using incentivized web surveys (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Fikel, Friedel, Krieger and Rettig2021).

We use this survey for two reasons. First, Angela Merkel's speech on the 18th of March coincided with their fieldwork period and did not interrupt the running of the web‐based data collection. Online Appendix Figure B.1 plots the daily distribution of completed surveys. The initial spike on the 1st of March is due to email invitations being sent out on that day.Footnote 6 Second, the GIP recruits participants offline based on a random probability sample of the general population in Germany aged 16–75. This helps with issues of imbalances that, for instance, apply to quota sampling. Balance tests by speech treatment for the covariates can be found in Online Appendix Tables B.1 and B.2. Summary statistics of key variables can be found in Online Appendix Table B.3.

Identification strategy

Political trust can be conceptualized as the belief that a trusted entity (whether a person or institution) will act to achieve positive outcomes, even when there is no way to verify or guarantee those outcomes (Easton, Reference Easton1965). In crises, following Devine et al. (Reference Devine, Valgarðsson, Smith, Jennings, Scotto di Vettimo, Bunting and McKay2023), we view it as relational citizens who place trust in the government to implement effective responses. We operationalize it using a variable that measures trust in the federal government. Specifically, we use a question that asks respondents to indicate their level of trust in various institutions, including the federal government, on a scale from 1 (no trust at all) to 7 (very high level of trust).

Our treatment variable ![]() is a dummy variable taking the value of 1 if the individual was surveyed after the speech took place and 0 otherwise. The number of participants within the treated and control groups is as follows:

is a dummy variable taking the value of 1 if the individual was surveyed after the speech took place and 0 otherwise. The number of participants within the treated and control groups is as follows: ![]() and

and ![]() . We estimate the treatment effect with OLS using the following specification:

. We estimate the treatment effect with OLS using the following specification:

where ![]() is the main coefficient of interest,

is the main coefficient of interest, ![]() captures federal state fixed effects and

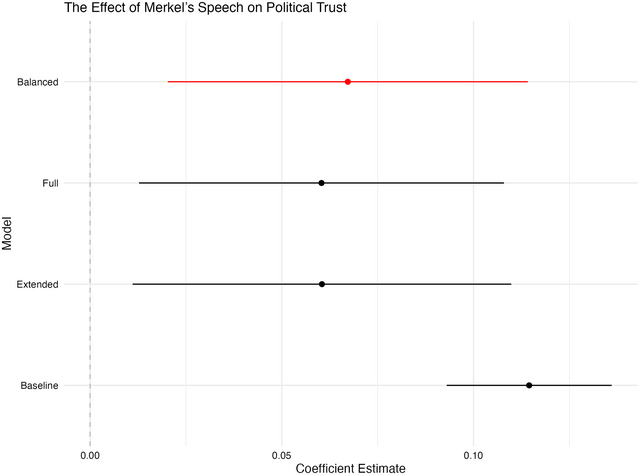

captures federal state fixed effects and ![]() is the error term. We assess the impact of Merkel's speech on political trust using four specifications. The ‘Basic' model incorporates the treatment and country fixed effects, with errors clustered at the country‐day level. The ‘Extended' model introduces a time variable to account for linear and quadratic time trends. The ‘Full' model adds individual‐level controls. Finally, the ‘Balanced' model employs entropy balancing to address any imbalances between treatment and control groups (Hainmueller & Xu, Reference Hainmueller and Xu2011), therefore, we use this model as the primary model. Additional details can be found in Online Appendix Section C.

is the error term. We assess the impact of Merkel's speech on political trust using four specifications. The ‘Basic' model incorporates the treatment and country fixed effects, with errors clustered at the country‐day level. The ‘Extended' model introduces a time variable to account for linear and quadratic time trends. The ‘Full' model adds individual‐level controls. Finally, the ‘Balanced' model employs entropy balancing to address any imbalances between treatment and control groups (Hainmueller & Xu, Reference Hainmueller and Xu2011), therefore, we use this model as the primary model. Additional details can be found in Online Appendix Section C.

The set of demographic control variables ![]() includes gender, age, education, employment status, marital status, number of household members, occupation and internet use.

includes gender, age, education, employment status, marital status, number of household members, occupation and internet use.

Results

Public trust

To visually display the discontinuities around Merkel's speech, Figure 2 presents daily binned averages of trust in government in March 2020. Eyeballing this figure, it is clear that there is a positive shift in trust in the government following the speech.

Figure 2. Daily trends in political trust.

Note: The figure shows daily binned averages of trust in government in March 2020. The vertical line indicates the date of Merkel's speech. A uniform kernel with quantile‐spaced bandwidth and entropy weights is applied following Calonico et al. (Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik2015).

For causal identification, we first compute treatment effects among all respondents. This allows us to understand the overall effect of the speech. Figure 3 shows that trust in the federal government has increased by 7 percentage points after the Merkel speech in the ‘Balanced' model (p ![]() 0.01). Next, we restrict the sample to only include respondents interviewed before 22 March, the day that Merkel went into quarantine after her personal physician tested positive. This allows us to isolate the immediate 3‐day effect of the speech and serves as a robustness check, ruling out the possibility that the treatment effect was influenced by the second spike in Figure 1 or the partial lockdown announcement, both of which occurred on 22 March. The treatment effect remains at 7 percentage points in this model (Online Appendix Table D.1).

0.01). Next, we restrict the sample to only include respondents interviewed before 22 March, the day that Merkel went into quarantine after her personal physician tested positive. This allows us to isolate the immediate 3‐day effect of the speech and serves as a robustness check, ruling out the possibility that the treatment effect was influenced by the second spike in Figure 1 or the partial lockdown announcement, both of which occurred on 22 March. The treatment effect remains at 7 percentage points in this model (Online Appendix Table D.1).

Figure 3. The effect of Merkel's speech on trust in government.

Note: The red line indicates the primary model referenced in the main text. Full estimates can be found in Online Appendix Table C.1. The outcome variable is normalized to vary between 0 and 1 for ease of interpretation.

To check if the observed effect is driven by an ideological shift, we examine the impact of the speech on respondents’ ideological placement of CDU/CSU. We also examine its effect on other parties’ ideological placement and respondents’ own ideological position as a placebo test. The results show no significant effect on the ideological placement of Merkel's party, other parties or respondents’ self‐reported ideology. These findings confirm that the treatment effect is not due to a shift in ideological positions (Online Appendix Table D.2).

Next, we investigate to what extent partisanship conditions the effect of the Merkel speech (Bolsen et al., Reference Bolsen, Druckman and Cook2014; Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013). After controlling for former political affiliation from September 2019, the magnitude and sign of the treatment effect remain unchanged (Online Appendix Table D.3). We also look into the interaction effect of pre‐treatment political affiliation with speech treatment on trust in government. These results indicate that, although there are effect size differences in partisan responses, motivated reasoning did not underpin the overall treatment effect (Online Appendix Figure D.1).

Moreover, the estimates are robust to assuming treatment on the day of the speech, excluding the day of the speech from the sample, controlling for the introduction of partial lockdown, and controlling for the number of Covid‐19 cases per million (Online Appendix Table D.4). We also check if Merkel's speech affected other political variables, and we only find an effect on trust in federal court, suggesting a general boost in institutional trust (Online Appendix Table D.5).

Finally, we analyse public compliance captured through mobility data from Google LLC (2021). Due to space constraints, this analysis is presented in Online Appendix Section E. In brief, we observe a notable decrease in non‐residential mobility and an increase in residential mobility following Merkel's speech. This finding aligns with the literature on public compliance, which suggests that political communication can significantly influence public behaviour during crises (e.g., Anderson & Hobolt, Reference Anderson and Hobolt2022). We discuss details of this analysis and its limitations in Online Appendix Section E.

Heterogeneity

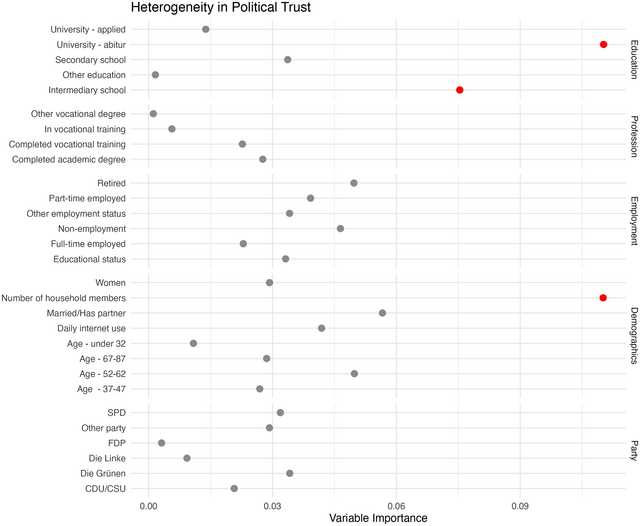

We supplement this analysis by incorporating a machine learning technique that provides insights into how political communication can be most effective for specific population subgroups. To achieve this, we employ a causal forests approach, which is a specific application of the generalized random forests algorithm developed by Athey et al. (Reference Athey, Tibshirani and Wager2019). We use causal forests to estimate conditional average treatment effects (CATEs) for covariates including gender, age, education, occupation, employment, marital status, number of household members, internet usage and pre‐treatment party affiliation. The method identifies regression trees that predict significant variations in effect size by randomly partitioning the data. We rank the covariates by their contribution to predicting the outcome variable using a measure of variable importance, which is calculated by computing a weighted sum of how frequently a variable was used in a tree split. Figure 4 shows that educational status and household size are among the most significant predictors of heterogeneous treatment effects. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is the higher likelihood that these groups have watched Merkel's speech, which could be attributed to factors like accessibility and media consumption. However, we refrain from making definitive claims about the reasons behind the increased receptiveness of these groups to Merkel's speech, as our primary goal is to highlight heterogeneity without introducing researcher bias, as intended by Athey et al. (Reference Athey, Tibshirani and Wager2019).

Figure 4. Heterogeneous treatment effects on political trust based on causal forest.

Note: Variable importance measures variable importance as the sum of the absolute values of the standardized total causal effect estimates (CATEs) across all trees in the forest, for each covariate. The red points highlight the three covariates with the highest variable importance.

Mechanisms

To be fair, a key question remains: Why do we observe such increases in political trust following Merkel's speech? Was it the speaker's identity, the specific message, or the unique German context? This question is challenging to address due to the absence of counterfactuals. Nevertheless, we take on this challenge by comparing Merkel's speech to other televised speeches by then‐Prime Ministers Mark Rutte (the Netherlands) and Boris Johnson (United Kingdom) given that same month. We find no similar effects of their speeches on political trust in the Netherlands or attitudes in the United Kingdom. More details on case selection, speeches, datasets, and variables are presented in Online Appendix Section F.

This finding challenges the notion that any leader's speech significantly boosts political trust. This raises the question: What was unique about Merkel's speech? Possible factors include its mode, reach or content. Notably, all speeches were broadcast on prime‐time TV and were of similar length (though Merkel's was the longest). Thus, mode and reach alone cannot fully explain the difference in impact.

To examine differences in content, we conducted a sentiment analysis of the three speeches. Results show that Merkel's speech emphasizes positive sentiment and trust more than those of Rutte and Johnson, focusing on reassurance and solidarity. Rutte's speech leans towards anticipation, likely preparing the public for future actions, while Johnson's speech shows slightly higher levels of fear and negative sentiment. Online Appendix Figure F.5 illustrates these results, with further details in Online Appendix Section F.3.

Finally, following Eisele et al. (Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2021)'s conceptual framework of crisis communication, we decompose the speeches into four dimensions using automated content analysis: (1) accessibility, (2) potential to allay fears, (3) accommodation of public concerns and (4) political alignment conveyed in it. As shown in Online Appendix Figure F.6, Merkel's speech, while less accessible yet similarly accommodating to Rutte's and Johnson's, stands out with its high alignment, indicating a heightened focus on unity and cooperation. Further details on this analysis can be found in Online Appendix Section F.4.

Taken together, our content analysis highlights differences in the political communication strategies of the three leaders. These findings align with Kneuer and Wallaschek (Reference Kneuer and Wallaschek2022), who emphasize solidarity as a central theme in Merkel's narrative. Similarly, Mintrom et al. (Reference Mintrom, Rublee, Bonotti and Zech2021) suggest that Merkel portrayed a unified German collective, contrasting with Johnson's framing of COVID‐19 as an adversarial force. Merkel's focus on unity and collective responsibility, in contrast to the frames of Rutte and Johnson, may have uniquely contributed to the observed increase in political trust in Germany.

Discussion

The COVID‐19 pandemic has brought to the forefront the crucial role that effective communication by political leaders plays in maintaining citizens’ trust in government institutions during times of crisis. The earlier literature studied political trust in crises (see, e.g., Devine et al., Reference Devine, Valgarðsson, Smith, Jennings, Scotto di Vettimo, Bunting and McKay2023), government crisis responses such as lockdowns in sustaining public support (see, e.g., Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021), the impact of political communication on public support (see, e.g., Anderson & Hobolt, Reference Anderson and Hobolt2022), and the content of political communication in crisis communication (see, e.g., Eisele et al., Reference Eisele, Tolochko and Boomgaarden2021). In this article, we build on the existing literature regarding if and how communicative interventions increase political trust while furthering understanding by identifying responsive population subgroups and deconstructing elements that contribute to effective political communication, offering suggestions as to why some leaders' communications are more successful at generating public support than others.

Our empirical analysis shows that Merkel's speech significantly increased trust in federal institutions and reduced nonresidential mobility in line with the communicated guidelines. No similar change in political trust is observed in response to Rutte's speech in the Netherlands or in general attitudes following Johnson's speech in the United Kingdom. Our analysis also demonstrates demographic heterogeneity in susceptibility to Merkel's speech, complementing the findings by Jørgensen et al. (Reference Jørgensen, Bor and Petersen2024) on heterogeneous responses to political communication. These findings suggest that not all communicative interventions can replicate the impact of Merkel's speech. This raises the question of what exactly made Merkel's speech effective. Although we cannot definitively pinpoint the exact mechanism, we suggest that the particular sentiment and content of her speech, emphasizing unity and solidarity with a positive sentiment, may have played a role in sustaining public support. However, we cannot entirely rule out the influence of Merkel's identity or the unique German context.

Understanding the mechanisms behind effective communication remains challenging without an ideal counterfactual. We addressed this by comparing Merkel's speech with those of Rutte and Johnson from the same month. While this comparison highlighted differences in content and delivery, it did not fully clarify the causal factors involved or how content intersects with leader attributes and other contextual factors, such as the political climate, timing of the communication, and media coverage at the time. Future research should extend this approach across diverse settings to better capture how communicative content, leader attributes, and context interact to shape public support during crises. Analysing a broader range of speeches delivered at various crisis points, examining how leader identity and other contextual factors influence tone, style, and substance and investigating how these resonate with different demographic groups will help refine our understanding of effective political communication. Integrating insights from both political trust and communication literature will further support this effort.

Acknowledgements

We thank the VolkswagenStiftung for generously funding the COVIDEU project on which this study is based (Grant: 9B051). We are also grateful to the panel members at MPSA 2023, attendees and discussants at EPSA 2023, and members of the COVIDEU project and the Humboldt Comparative Political Behavior Research Group for their valuable feedback. Additionally, we thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments, which greatly improved this paper.

Data availability statement

Replication material for this study is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JFYMOK.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure B.1: Data collection around the speech.

Table B.1: Balance table by speech treatment.

Table B.2: Balance table by speech treatment.

Table B.3: Summary statistics.

Table C.1: Merkel's speech and trust in federal government.

Table D.1: Restricting sample to pre‐quarantine period.

Table D.2: Merkel's speech and ideological placement.

Figure D.1: Marginal effects of Merkel's speech on trust in government, comparing pre‐treatment CDU/CSU affiliation with other party affiliations.

Table D.3: Merkel's speech, political affiliation and political trust.

Table D.4: Robustness checks with the day of speech.

Table D.5: Merkel's speech and other political variables.

Figure E.1: Aggregate mobility in March 2020 (Red line depicts Merkel's speech).

Table E.1: Merkel's speech and mobility at state‐date level.

Figure F.1: Google search interest in ‘Mark Rutte’ in the Netherlands.

Figure F.2: Daily trends in political trust in the Netherlands.

Figure F.3: Google search interest in ‘Boris Johnson’ in the United Kingdom.

Figure F.4: Daily trends in life satisfaction in the UK.

Figure F.5: Sentiment distribution across speeches of Rutte, Merkel, and Johnson.

Figure F.6: Comparison of scores by measure in speeches from Merkel, Rutte, and Johnson.

Figure G.1: Twitter trends on the day of the speech, 18 March 2020. Merkel's televised speech took place on 19:00.