1 Variation in a Complex System

The essential idea behind this work is that the grammar is a complex system, a network (Schneider, Reference Schneider, Mauranen and Vetchinnikova2020). This means that individual constructions are connected to one another through INHERITANCE RELATIONS (with some constructions being more item-specific versions of others) and SIMILARITY RELATIONS (with some constructions carrying the same form or the same meaning as others). If the grammar is structured as a network, then we would hypothesize that grammatical variations spread through this network structure and thus that differences between dialects, between registers, and between individuals are best represented as differences between networks.

The case-studies in this Element examine variation across individuals (authorship) and geographic populations (dialect) and contexts of production (register). In all three cases, we will show that the amount of syntactic variation is remarkable so long as we possess sufficient means of observation. We will quantify the amount of variation by taking a classification approach which predicts underlying categories (like dialect membership) given the usage of constructions. Higher prediction accuracy indicates that there is more variation because a category which has more unique variants is easier to distinguish. Thus, we will first show that there is significant syntactic variation in each case by using constructional features to predict individuals, dialects, and registers.

We will then use similarity measures to construct networks that represent variation in the population. A similarity measure allows us to estimate, for instance, how grammatically distinct individuals from Chicago and Los Angeles and New York are from one another. While classifiers are supervised models, having access to training samples, similarity measures are unsupervised. The first question, for classifiers, is the magnitude of syntactic variation if we observe usage in many contexts all over the world all at once. The second question, for similarity measures, is the structure of syntactic variation and how the diffusion of variants takes place across a grammar which is a complex system. How pervasive is syntactic variation? How is it organized within the grammar? How is it organized within the larger population? These are the questions that we address at scale using computational methods.

Going back to the idea that syntactic variation is both robust and widespread, what exactly constitutes sufficient means of observation in this context? There are three necessary components: First, we must have a model of the grammar which includes both (i) constructions at different levels of abstraction as well as (ii) relations between those constructions. This Element thus depends on recent computational work in Construction Grammar (Dunn, Reference Dunn2024), without which we would not be able to observe the grammar as a complex system.

Second, we must have observations of language use that adequately represent the speech community as a complex network, rather than carry out dialectology within a single local region, like Northeastern vs Midwestern American English, we need to view the population itself as a global network with varying degrees of mutual exposure between local nodes. This Element thus depends on recent work in geographic corpora (Dunn, Reference Dunn2020) without which we would not be able to observe the full range of speakers of English around the world.

Third, because modeling variation within a complex system goes beyond the capabilities of even multivariate regression models, we must have high-dimensional and network-based models in order to adequately observe variation. Thus, this Element depends on more recent work in machine learning, relying on classifiers and unsupervised similarity measures and graph-based models. In practical terms, these three components combine to enable a comprehensive computational theory of syntactic variation that was not previously feasible: computational grammars applied to large digital corpora and analyzed using high-dimensional models.

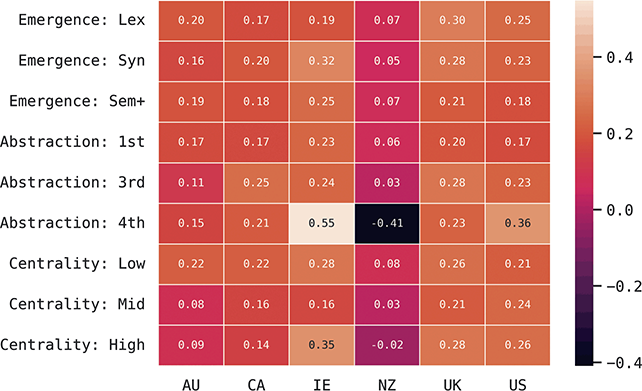

Returning to the case-studies, once we have shown how substantial the amount of syntactic variation is, our main hypothesis is that the structure of that variation depends on the network structure of the grammar. For instance, processes of diffusion are expected to follow pathways that already exist in the form of relations between constructions. This hypothesis can be divided into three testable predictions: First, we expect that different parts of the network will contain more or less amounts of variation; for instance, not all parts of the grammar will have equally high classification accuracy. Second, we expect that the three kinds of variation will exist in different parts of the grammar; for instance, we expect that individual variation exists in more concrete constructions (more item-specific), while register variation is spread across all constructions. Third, we expect that, if processes of diffusion are concentrated on specific nodes of the grammar, observed similarity relationships will not be constant across the grammar. For instance, New Zealand English might be more similar to Australian English in phrasal verbs but at the same time more similar to British English in passive constructions. In other words, diffusion – and thus synchronic – similarity operates across the existing network structure of the grammar.

This first section introduces a conceptual framework for combining computational syntax with computational sociolinguistics. To ensure reproducibility, all input data, resources, and analysis are available in an open source repository.Footnote 1

1.1 Computational Syntax and Computational Sociolinguistics

This section briefly contextualizes this work within both computational syntax and computational sociolinguistics in order to understand why the increased scale that computational methods provide is important. Starting with computational syntax, a construction grammar is a network of form-meaning mappings at various levels of schematicity (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006) which are built out of emerging ontologies of slot constraints (Croft, Reference Croft, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013). This grammar is a network composed of inheritance relationships and similarity relationships between pairs of constructions (Diessel, Reference Diessel2023). CxG is a usage-based approach to syntax: concrete and item-specific constructions are learned first and only later generalized into schematic constructions (Doumen, Beuls, & Van Eecke, Reference Doumen, Beuls, Van Eecke, Vlachos and Augenstein2023; Nevens et al., Reference Nevens, Doumen, Van Eecke and Beuls2022).

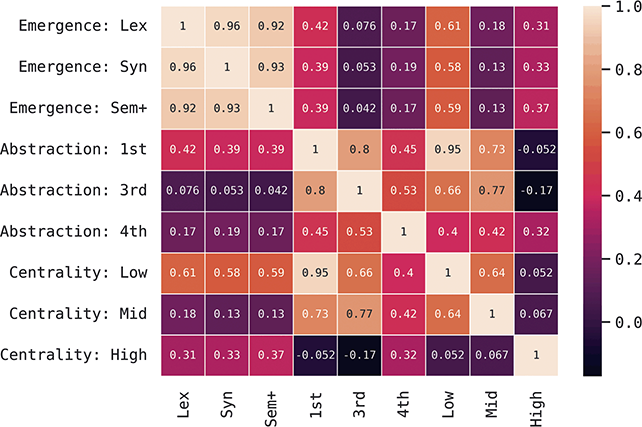

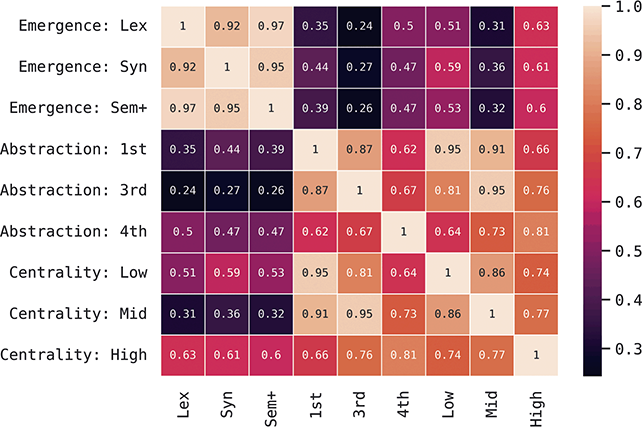

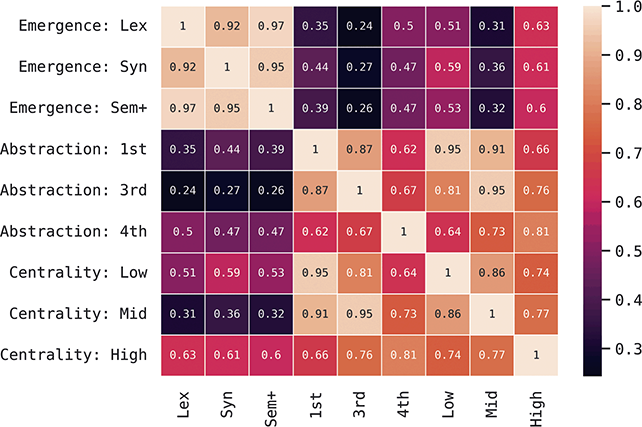

Given that the grammar is a complex system, variation will be influenced by three factors: first, the level of abstraction or how schematic a construction is; second, the degree of centrality or how core a construction is within the grammar (Hollmann & Siewierska, Reference Hollmann and Siewierska2011); and, third, the order of emergence or how early a construction is learned (Dunn, Reference Dunn2022). Because the indexicality or social meaning of constructions is a means by which they can be differentiated (Leclercq & Morin, Reference Leclercq and Morin2023), variation is an inherent property of the grammar from the very beginning.

The basic idea in this Element is that we first use computational syntax to learn an unsupervised representation of the grammar of English and then use this rich feature space as a means of understanding variation across individuals, populations, and registers. Relying on unsupervised computational syntax means that (i) the methods are reproducible and do not begin with annotator bias; (ii) the grammar represents both inner-circle and outer-circle dialects equally, unlike annotated corpora; (iii) the grammar provides a much broader and deeper feature space for observing variation; and (iv) the structure of the grammar as a complex network is directly available to our experiments.

This work thus builds on a long history of computational models of the emergence of construction grammars, from specific families like argument structure constructions (Alishahi & Stevenson, Reference Alishahi and Stevenson2008; Barak & Goldberg, Reference Barak and Goldberg2017) to shallow but wide-coverage models of holophrase constructions (Wible & Tsao, Reference Wible and Tsao2010, Reference Wible and Tsao2020) to template-based methods that build on annotations and introspection (Perek & Patten, Reference Perek and Patten2019). Some work has taken an agent-based approach in which individual learners acquire constructions during communication until all observed utterances can be successfully interpreted (Beuls & Van Eecke, Reference Beuls and Van Eecke2023). This body of work as a whole can be viewed as a discovery-device grammar (Goldsmith, Reference Goldsmith, Chater, Clark, Goldsmith and Perfors2015) which formulates syntactic representations given exposure to a corpus. Thus, CxG as a theory can be viewed as a mapping between exposure and an emergent grammar.

At the same time, this work also builds on a long history of corpus-based models in computational sociolinguistics, in which an unelicited corpus of usage is taken as a representation of dialectal production (Grieve, Reference Grieve2016; Szmrecsanyi, Reference Szmrecsanyi2013). This tradition depends on corpora that represent specific dialect communities, whether compiled manually (Greenbaum, Reference Greenbaum1996) or drawn from web pages (Cook & Brinton, Reference Cook and Brinton2017; Davies & Fuchs, Reference Davies and Fuchs2015) or pulled from geo-referenced social media posts (Donoso, Sánchez, & Sanchez, Reference Donoso, Sánchez and Sanchez2017; Eisenstein, O’Connor, Smith, & Xing, Reference Eisenstein, O’Connor, Smith and Xing2014; Gonçalves & Sánchez, Reference Gonçalves and Sánchez2014; Mocanu et al., Reference Mocanu, Baronchelli and Perra2013; Wieling, Nerbonne, & Baayen, Reference Wieling, Nerbonne and Baayen2011).

Work in computational sociolinguistics has established that lexical usage on social media mirrors usage as captured by dialect surveys (Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Montgomery, Nini, Murakami and Guo2019) and also that digital communities develop their own nongeographic variants (Lucy & Bamman, Reference Lucy and Bamman2021). Because corpora provide more samples, thus providing more robust and diverse examples of usage, computational sociolinguistics has also found that categories like gender are more complex when viewed at scale (Bamman, Eisenstein, & Schnoebelen, Reference Bamman, Eisenstein and Schnoebelen2014). Other work has looked at the disproportionate influence that inner-circle varieties like American English exert in digital spaces (Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Loureiro-Porto, Ramasco and Sánchez2018) and at how deeper syntactic variation can be modeled as differences in constraint rankings (Grafmiller & Szmrecsanyi, Reference Grafmiller and Szmrecsanyi2018; Szmrecsanyi & Grafmiller, Reference Szmrecsanyi and Grafmiller2023).

Much of this work has focused on variation across groups, with groups represented by categorical variables like gender or location or context. But the speech community is also a network in which each individual is a node represented by its degree of contact within the network (Fagyal et al., Reference Fagyal, Swarup, Escobar, Gasser and Lakkaraju2010). English, in particular, forms a global network with exposure and contact between geographically distant dialects. These long-distance connections are created as a result of immigration, mass media, and digital communication platforms (c.f., Dąbrowska, Reference Dąbrowska2021). Thus, each local population is a node in a global network of English users. We must take seriously the idea that both language (Beckner et al., Reference Beckner, Ellis and Blythe2009) and the speech community (Schneider, Reference Schneider, Mauranen and Vetchinnikova2020) are complex networks.

The advantage of a computational approach is scale: we can observe variation across a wider selection of the grammar and across a wider selection of the speech community. Traditional work has always been severely limited in scale, and as a result has placed undue importance on distinctions like weak vs strong ties. In part, this is because the networks being observed in such studies are cognitively and socially unrealistic (Fagyal et al., Reference Fagyal, Swarup, Escobar, Gasser and Lakkaraju2010). Such traditional work has also assumed that only face-to-face conversations are interactive (Trudgill, Reference Trudgill2014), much like early work in dialectology assumed that speakers were geographically immobile. Both of these assumptions, if they ever were valid, are clearly no longer applicable: the speech community now is highly mobile both within and between countries and engages in long-distance interactions through digital avenues like social media. Work in computational sociolinguistics has shown, for instance, that studies which rely on unrealistically small networks overstate the importance of strong vs weak ties within a network (Laitinen & Fatemi, Reference Laitinen, Fatemi, Rautionaho, Parviainen, Kaunisto and Nurmi2022; Laitinen, Fatemi, & Lundberg, Reference Laitinen, Fatemi and Lundberg2020).

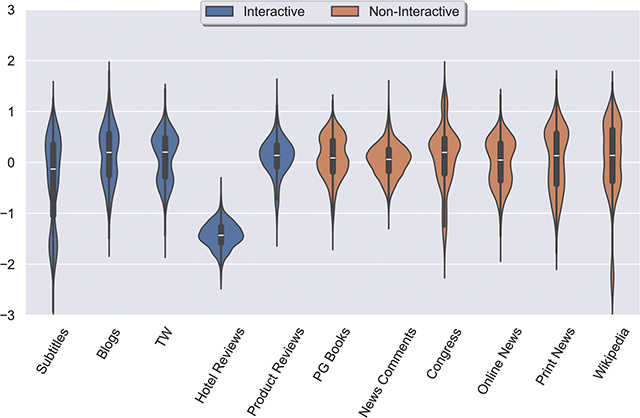

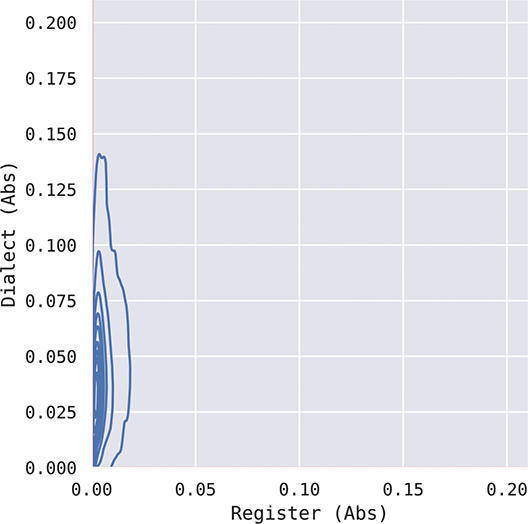

This Element relies on social media data to observe individual and dialectal variation, but then considers variation across contexts in the final section. While traditional methods have relied on the idea of a pure vernacular as the only valid source of observing variation, this assumption is not suitable to language use in the contemporary world. Written and digital registers are important sources of exposure, and there is not a clear distinction between formal writing and the spoken vernacular. Even within a single register there are many sub-registers that can be difficult to distinguish: register is a continuum (Biber, Egbert, & Keller, Reference Biber, Egbert and Keller2020; Egbert, Biber, & Davies, Reference Egbert, Biber and Davies2015). Rather than ignore register variation in the quest for a pure vernacular, we therefore end this Element by looking at variation across contexts and explicitly compare the way in which dialectal variation and contextual variation are structured in grammar.

To conclude, this work is situated within the traditions of both computational syntax and computational sociolinguistics. Both rely on computational models and large corpora to expand the scale of our understanding of language and to make our findings more reproducible. This is important because, if both language and the speech community are complex networks, then variation can be seen as an emergent property of language use. Small-scale approaches which rely on manual analysis of only a few samples from a few speakers will always be inadequate for understanding a complex system. The Element shows in detail how we can move beyond these methodological limitations.

1.2 A Computational Model of the Grammar

A model of grammatical variation must operate on some feature space which serves as a description of the grammar itself. In early corpus-based work on syntactic variation, this description was simply a single alternation: for example, contracted vs noncontracted forms (Grieve, Reference Grieve2011), agreement in existential-there constructions (Collins, Reference Collins2012), adverb placement in verb phrases (Grieve, Reference Grieve2012), or genitive and dative alternations (Szmrecsanyi et al., Reference Szmrecsanyi, Grafmiller, Heller and Rothlisberger2016). The problem is that studies of individual alternations have no capacity to generalize: Are other features undergoing the same direction of change? Do these features have an impact on other portions of the grammar, leading to syntactic chain-shifts? How representative are these features of the grammar as a whole? Is this variation located in the center or in the periphery of the grammar? These questions cannot be addressed given individual features.

As a result, the next wave of work focused on aggregating across individual features: for example, a set of 57 surface-level variants like nonstandard reflexives (Szmrecsanyi, Reference Szmrecsanyi2013), a set of 135 surface-level variants like previous vs prior (Grieve, Reference Grieve2016), and a set of 3 more abstract constructions like the dative and the genitive (Szmrecsanyi & Grafmiller, Reference Szmrecsanyi and Grafmiller2023). While this line of work is less arbitrary than individual features, it is still based on fixed introspection-based choices derived from prestigious inner-circle varieties. More importantly, many of these representations remain relatively surface-level, often more on the lexical end of lexico-grammatical continuum. Given that the grammar ranges from highly item-specific holophrase constructions to highly abstract families of constructions like the transitive, where is variation located across levels of abstraction? We could never answer this kind of question using hand-curated surface-level alternations which are ultimately located in a single region of the grammar.

To resolve these weaknesses, more computationally-driven work has connected the study of variation within a grammatical feature space (Dunn, Reference Dunn2018a, Reference Dunn2019b) with grammar induction or the learning of such a feature space (Dunn, Reference Dunn2017). The idea in this approach is to view the feature space as a discovery-device grammar, D, which provides a usage-based model of how constructions emerge given exposure (a corpus, CORPUS). Thus, a specific grammatical feature space is the output of a discovery-device grammar: G = D(CORPUS). As a result, the feature space is not fixed and need not implicitly maintain an inner-circle focus. A model of variation (VAR) works on top of a grammatical feature space: VAR(G). Here that feature space is actually a model of an entire grammar and maintains its network structure: VAR(D(CORPUS)). So the grammar is a network learned from a corpus, its linguistic experience, and the model of variation operates on top of that replicable and dynamic feature space.

We have several important questions about language variation and change which can only be investigated using this high-dimensional discovery-device approach: First, do processes like diffusion operate on individual constructions alone or do they operate on nodes within the grammar, creating a pressure that applies with diminishing force as it passes through the grammar network? Second, can a dialect be influenced simultaneously in two different directions, so that individual constructions would show opposing directions of change? Third, what impacts does change in one part of the grammar have on other parts of the grammar, not because of continued diffusion but because of internal impacts from syntactic chain-shifts? Fourth, does the level of abstraction impact the order of variation, with more concrete and idiomatic and item-specific constructions changing first? These are all questions which we can only approach with a principled and systematic grammar: individual constructions or arbitrary collections of alternations are both inadequate to the task.

For these reasons, we need to start our study of grammatical variation with a reasonably adequate model of the grammar. We draw on work in computational construction grammar (Dunn, Reference Dunn2024). Constructions are constraint-based representations composed of (i) slots and (ii) slot-fillers that are derived from specific ontologies or systems of categorization. For example, in (1a) the construction has three slots or positions. The first slot is defined with semantic information and the remaining slots are defined with syntactic information. In this case, then, we have three positions and two ontologies or systems of categorization used to define what linguistic material those positions can hold. This is the basic form of a construction.

(1a) [ transfer-event – noun phrase – noun phrase ]

(1b) “send me the bill”

(1c) [ give – noun phrase – a hand ]

(1d) “give me a hand”

Small changes in these constraints can lead to significant changes in the set of utterances which they license. For example, if we replace the semantic slot-constraint in (1a) with a lexical constraint in (1c), we now have an item-specific and idiomatic construction, as in (1d). This construction is still productive in the sense that it licenses or produces a varied set of utterances; however, it is less productive and more concrete than the original in (1a). From a usage-based perspective, the grammar is learned from exposure to usage together with general learning principles. We would expect, then, that each individual has a unique set of linguistic experiences (different exposure) and would learn slightly different slot-constraints. Because constructions can overlap (e.g., 1a and 1c would produce some of the same utterances), individuals might have different sets of constructions even when their production largely overlaps.

The advantage of a discovery-device or computational approach to grammatical representation is that we can capture such differences. There is no theoretical reason to posit that all dialects of English have the same set of ditransitive constructions, for instance, or that each dialect has the same ontology of slot-constraints. A reliance on simplified, abstracted, bleached constructions is a practical problem: in our view, linguists in an armchair cannot use introspection to find out what the ontology of slot-constraints in Nigerian English is or what the inventory of ditransitives in Indian English is. These are empirical questions. Our approach here is to model the learning of constructions given exposure, where learning is grammar induction using machine learning and exposure is a corpus. This is not an exact analogy to human learning; for example, language use in a corpus is structured much differently than language use in an embodied, situated context. It remains the case, however, that a corpus-based approach with a discovery-device grammar is much more realistic than previous methods based on individual constructions or arbitrary surface-level alternations.

The challenge of learning construction grammars and what that looks like computationally is a matter for other work (Dunn, Reference Dunn2017, Reference Dunn2018b, Reference Dunn2018c, Reference Dunn2019a, Reference Dunn2022, Reference Dunn2023a, Reference Dunn2024; Dunn & Nini, Reference Dunn and Tayyar Madabushi2021; Dunn & Tayyar Madabushi, Reference Dunn and Nini2021). What we will do here is briefly sketch what such a grammar looks like:

First, a construction grammar must define the sets of slot-constraints. This encompasses both what ontologies are relevant (i.e., syntactic, semantic, etc) as well as which specific categories are actually in these ontologies. In computational CxG, this is done using distributed representations (i.e., embeddings).

Second, a construction grammar must define how such slot-constraints are combined into constructions. In computational CxG, this is a sequential model much like a phrase structure grammar (as opposed to, for instance, a relational model like a dependency grammar): slot-constraints are contiguous.

Third, a construction grammar must define how individual constructions are related to one another (i.e., parent-child relationships). In computational CxG, similarity between constructions is measured using both (i) similarity of representations and (ii) similarity of utterances in a reference corpus. These similarities are used to organize constructions at three levels of abstraction: first- and second-order constructions (the most concerete), third-order constructions (mid-level), and fourth-order constructions (the most abstract). In terms of hierarchy, fourth-order constructions are the parents of third-order constructions. These are learned upwards, starting from concrete surface-level forms. Thus, our exploration of syntactic variation here is organized by increasingly abstract constructions; first-order constructions have a single representation while fourth-order constructions are groups or families of related representations.

Fourth, a construction grammar must posit a means by which constructions are learned from exposure; in computational CxG the optimization metric is based on Minimum Description Length (Grünwald, Reference Grünwald2007), which means that the learner is balancing what information needs to be memorized (tending towards large shallow grammars) and what information needs to be computed (tending toward small but highly abstract grammars). This balance implicitly depends on the amount of exposure: larger corpora, which encompass more linguistic experience, support larger and more item-specific grammars.

For the sake of example, we discuss several constructions from the tweet-specific grammar used in the Element. These examples are all first-order constructions; third-order and fourth-order constructions are more abstract families that combine these lower-level constructions. In (2) we see a noun phrase derived from the early-stage (local only) grammar (c.f., Section 1.3); there are two slots, each defined by a syntactic constraint. These constraints are in fact learned as centroids within an embedding space. The label syn refers to the ontology used to define the slot constraint; the number 174 is an arbitrary identifier; the name <buttercream-custard> is a human-readable label which provides two exemplars of the category. As we might expect, this is not a generic notion of noun; here all fillers are edible physical items, such as peanut butter cup. In (3) we see a different noun phrase from the late-stage (multiple constraint) grammar; these slot-constraints are derived from three sources (lexical, syntactic, and semantic). These particular constraints result in definite noun phrases describing an individual, like the happiest person. These two noun phrases are simple examples of the range of utterances produced by simple data-driven slot-constraints.

(2) [ syn:174 <buttercream-custard> – syn:174 <buttercream-custard> ]

(2a) peanut butter cup

(2b) chocolate milk

(2c) banana ice-cream

(2d) chocolate fudge

(3) [ sem:141 <which-whereas> – syn:66 <shadiest-silliest> – lex: “person” ]

(3a) the worst person

(3b) the smartest person

(3c) the funniest person

(3d) the happiest person

Comparable examples of verbal constructions are shown in (4) and (5). In (4), we see an early stage (i.e., with only syntactic constraints) construction with verbs of thinking that introduce a subordinate clause that is not included in the construction. For example, with still don’t know who the construction contains the verb and adverb with an object relative clause attached, but not contained. In (5) we see a late-stage construction, here with only semantic constraints, that again contains a main clause verb phrase together with the subject of a subordinate clause, as in i know i’m. Because constructions are joined together to create a complete utterance, this would be combined with a construction covering the remainder of the subordinate clause with the overlapping slot-constraint providing the link in that chain.

(4) [syn:100<always> – syn:143<won’t> – syn:88<understand> – syn:100<always>]

(4a) still don’t know who

(4b) really do think that

(4c) just don’t care if

(4d) honestly don’t think he

[]

(5) [sem:1<he-we> – sem:377<think-know> – sem:1<he-we> – sem:675<now>]

(5a) i know i’m

(5b) i think i’m

(5c) i swear i’m

(5d) i suggest that we

This section has described the grammatical representations and given a few examples of nominal and verbal constructions. For more discussion of the idea (i) of slot-constraints formulated as centroids within an embedding space, (ii) of early vs late grammars based on the order of emergence, (iii) of how constructions might be joined together into larger structures, and (iv) of how slot-constraints emerge, see an overview of computational CxG (Dunn, Reference Dunn2024).

1.3 Networks: Structure within the Grammar

Our reason for looking at variation across the grammar, rather than variation across a few constructions, is to understand how changes spread across the network and how syntactic chain-shifts can occur as these changes spread. The question in this section is how we move from viewing the grammar as a flat feature set – a set of constructions – to viewing the grammar as a connected network. We can categorize constructions based on (i) when they are learned or their order of emergence and (ii) their level of abstractness and (iii) their centrality in the grammar. In the first case we can contrast early and late constructions (order of emergence). In the second case we can contrast abstract vs item-specific constructions (level of abstraction). And in the third case we can contrast central and peripheral constructions (degree of centrality).

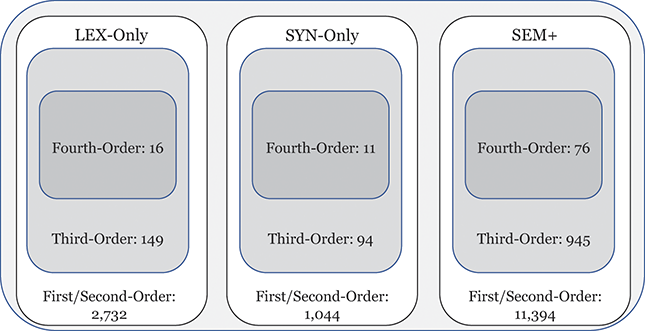

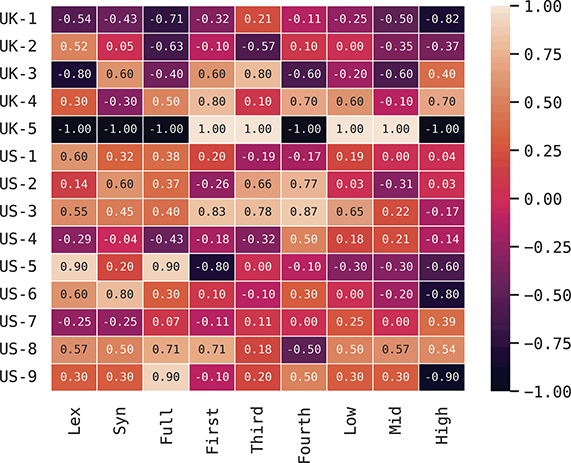

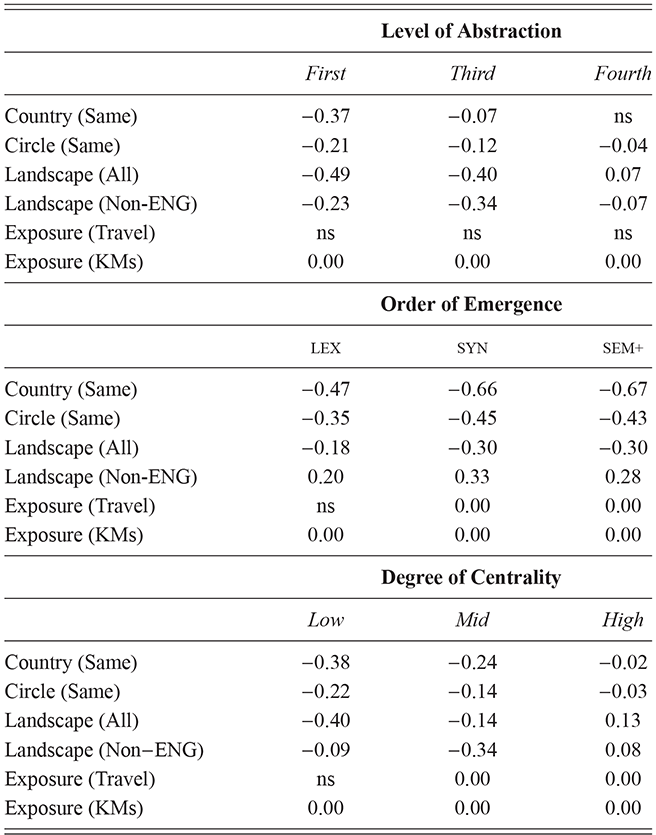

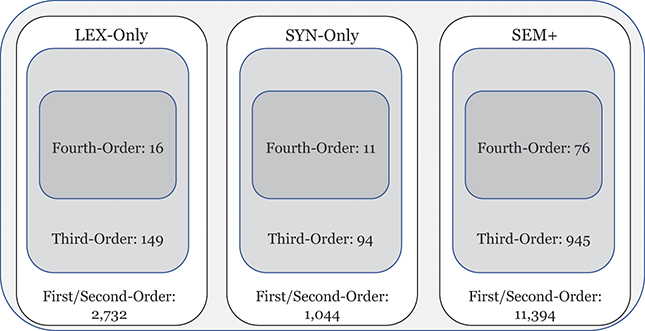

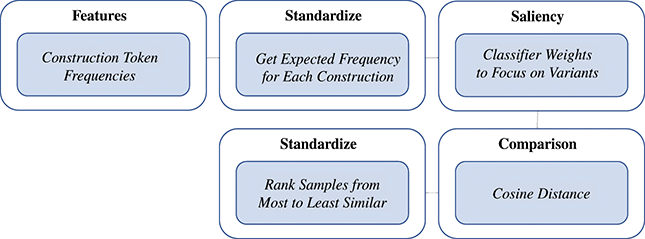

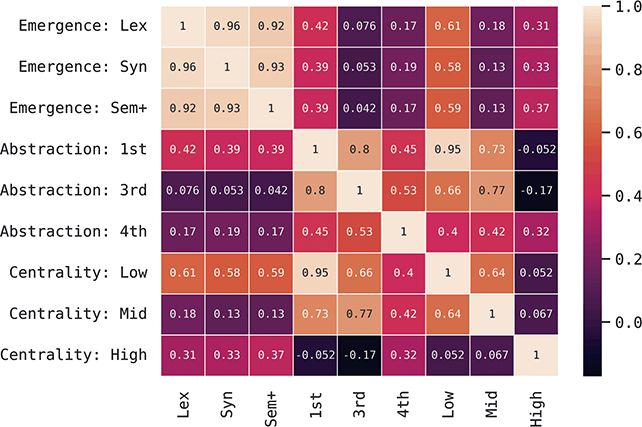

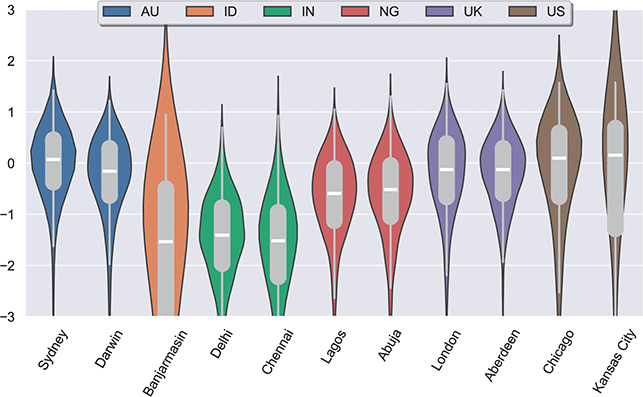

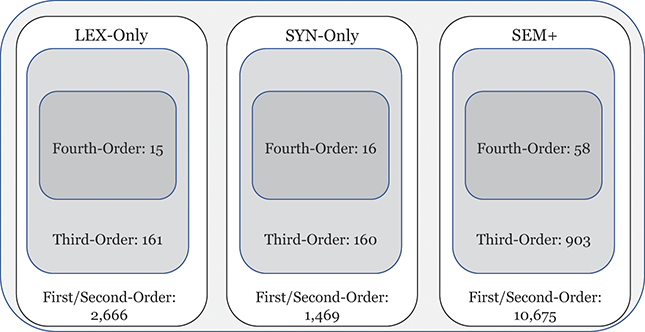

This approach to categorizing constructions within the grammar is visualized in Figure 1. The grammar as a whole contains 15,172 constructions across orders of emergence and levels of abstraction. These are organized into 1,190 mid-level constructions (e.g., third-order) and 103 high-level (e.g., fourth-order) constructions. To be clear, a third-order construction is a bundle of related first-order constructions; thus, in terms of the inheritance hierarchy, the first-order constructions are children of a third-order construction and siblings of other first-order constructions in the same cluster. Rather than develop more abstract human-readable representations for third-order constructions, we instead look at many different first-order constructions as a way of understanding that more abstract representation.

Figure 1 Division of constructions in the grammar by emergence and abstractness.

Figure 1Long description

The illustration depicts the number of constructions in different portions of the grammar. First/Second-Order constructions make up most of the grammar, with Fourth-Order constructions being the least common. Similarly, late-stage SEM+ constructions are more common than early-stage LEX-Only constructions.

We can examine differences by order of emergence by comparing groups from left to right in Figure 1. We can examine differences by level of abstraction by comparing nested boxes from top to bottom in Figure 1. And we can examine variation within specific nodes of the grammar by focusing only on siblings: members of the same box in Figure 1. Thus, considering the late-stage sem+ grammar, we could observe 11,394 surface-level constructions or 945 mid-level constructions or 76 high-level constructions. These represent the grammar across different levels of abstraction. Finally, we can examine strata of centrality by using frequency weights derived from an independent reference corpus.Footnote 2

What does this mean in theoretical terms? We might expect that individual differences within a given population occur in more concrete constructions (first-order) and at later stages of emergence (sem+). We might expect that similarity between dialects is consistent across sibling constructions but differs only in disconnected nodes of the grammar (i.e., within separate fourth-order constructions). And we might expect that different registers have the same constructions but differ in the centrality of those constructions. Dividing the grammar like this allows us to examine variation in a way that individual constructions or a flat set of constructions cannot.

The examples in Section 1.2 contrasted early-stage and late-stage grammars. Here we consider examples at different levels of abstraction. The previous examples were first-order constructions, defined as having slot-constraints that are drawn from the basic ontology (lexical items) rather than allowing other constructions as fillers. Here we look at examples of third-order and fourth-order constructions which are more abstract representations that contain many sibling constructions. These are only identified by cluster id, without a human-readable representation, so we examine each by giving three representative first-order constructions. But it is important to note that these constructions are more abstract than these first-order examples because they describe many such first-order siblings.

The three verbal constructions in (6–8) are siblings within a third-order construction. This means that they are more concrete individual constructions which correspond to the same abstract construction. When we examine variation, we could look at the lower-level frequencies of (6–8) individually or we could look at the higher-level frequencies of this third-order construction. This is what we mean by operating across different levels of abstraction. Here, each first-order construction has a main verb that encodes the subject’s modal state while carrying out an action which is encoded within an infinitive clause.

(6) [syn:185 <permitted> – sem:14 <then-once> – syn:67 <antagonize-placate>]

(6a) tried to intimidate

(6b) refused to allow

(6c) trying to spoil

(6d) unable to vanquish

(7) [syn:185 <permitted> – sem:14 <then-once> – lex: stop]

(7a) failed to stop

(7b) trying to stop

(7c) able to stop

(7d) decided to stop

(8) [syn:185 <permitted> – sem:14 <then-once> – syn:88 <understand-believe>]

(8a) delighted to see

(8b) refusing to forgive

(8c) obligated to love

(8d) seeks to reassure

At a higher level of abstraction, a fourth-order construction is similarly composed of many third-order constructions, thus encompassing a greater portion of the grammar. The constructions in (9–11) are first-order constructions which are examples of other third-order constructions within the same fourth-order construction represented in (6–8). In other words, (6–8) are siblings of one another and cousins of (9–11). The construction in (9) again uses the main verb to encode the subject’s mental state, but now this is directed towards an adpositional phrase which is attached to but not contained within the construction. In (10) there is an infinitive verb which instead encodes the speaker’s state, and in (11), more similar to (6–8), the object of the action is now included within the construction. These are three examples from other third-order constructions, all contained within the same abstract fourth-order construction. From the perspective of variation, we could observe differences at any of these levels of abstraction. From a usage-based perspective, we would expect more variation at lower levels of abstraction.

(9) [ syn:159 <terrified> – sem:14 <then-once> – sem:141 <which-whereas> ]

(9a) excited over the

(9b) impressed at the

(9c) amazed when the

(9d) disgusted at the

(10) [ sem:14 <then-once> – syn:168 <demonstrate> – sem:141 <which> ]

(10a) to applaud the

(10b) to recognize the

(10c) to welcome the

(10d) to embrace the

(11) [syn:185<permitted> – sem:14<then-once> – syn:88<believe> – sem:25<them>]

(11a) trying to convince me

(11b) fails to remind me

(11c) proceeded to ask us

(11d) supposed to tell me

These examples are all first-order constructions. Higher-order abstractions are made by viewing these more concrete constructions as children of larger and more diverse constructions. The emergence of constructions proceeds upwards, starting with first-order constructions and generalizing to higher-orders of structure.

1.4 Overlap: Comparing Grammar and Usage

We now have a robust network representation of the grammar that we can use for finding variation between individuals, populations, and registers. How do we conceptualize differences in the grammar? The main concept is overlap: two individuals, for instance, will share a large portion of the grammar but will not share certain nodes within it. The more the two grammar networks overlap, the more similar these two individuals are.

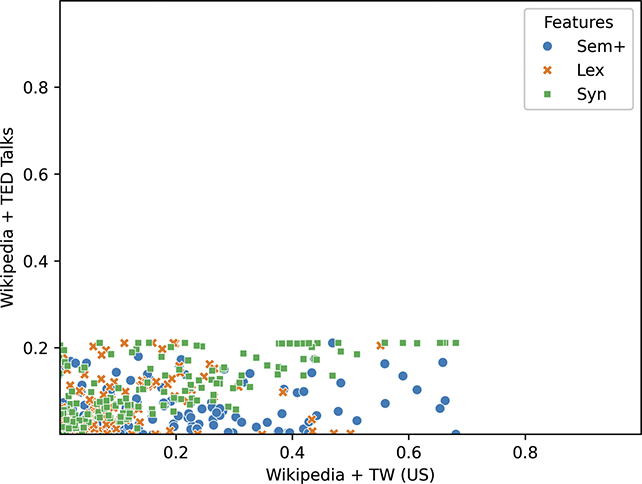

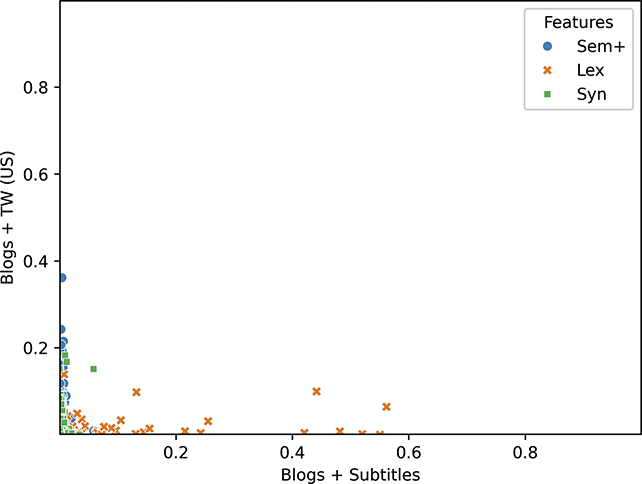

We could calculate overlap in terms of the grammar itself (c.f., Dunn & Nini, Reference Dunn and Nini2021; Dunn & Tayyar Madabushi, Reference Dunn and Tayyar Madabushi2021): if we learn a unique grammar given a simulation of the exposure experienced by an individual speaker of a dialect, for instance, how much does that learned grammar differ from the same simulation in other dialect areas? This is a comparison of the grammar itself because we have two networks learned independently under different conditions, where each condition is a type of exposure (i.e., a model of Midwest American English is exposed to corpora from that region).

Another approach is to calculate overlap in terms of the usage of a single umbrella grammar by different populations (c.f., Dunn, Reference Dunn2019b, Reference Dunn2023b): here we learn a single grammar network given a sample of usage from many dialects and individuals, essentially creating an abstraction which is not situated within a single speech community. We then compare dialect groups, for instance, given their usage of different portions of this grammar; some portions might be completely unused (and thus not entrenched at all), while other portions are used infrequently (and thus only weakly entrenched). Thus, dialects would differ in their relative entrenchment of different portions of the grammar.

These contrasting paradigms have their own strengths and weaknesses. Comparing grammars allows us to simulate different types of exposure and is more naturalistic in the sense that speakers of a dialect have arrived at that dialect directly rather than first learning a generic grammar and then selecting certain variants. On the other hand, comparing grammars in this way provides two distinct feature spaces which makes measuring overlap more difficult; and the grammar learning process itself is subject to certain bits of random noise so that some variation will be arbitrary.

Comparing usage allows us to obtain fine-grained measures of overlap within a single feature space and it maps well to noncomputational work in variation, which by definition assumes a single shared feature space through which each group is analyzed. On the other hand, the usage approach is not naturalistic because no individual learner has equal exposure to all dialects or attaches equal prestige to all sources of exposure. Thus, it is an artificial simulation of variation, albeit one whose artifice is shared by much previous work.

In this Element we compare usage. Thus, the methodology is to first learn a grammar network for each register (c.f., Section 1.2), in which all dialects and all individuals are equally represented. This forms an umbrella grammar which should capture portions of the grammar that, in fact, are acquired by only limited sections of the overall population. In other words, while our purpose is to study variation, we start with a grammar which essentially posits a single network for English within each register. We then take the usage of constructions as a measure of the entrenchment of different portions of this grammar within each population or individual.

Once we have learned this register-specific umbrella grammar, we use the token frequency of its constructions to estimate the entrenchment of each construction for individuals and populations. Higher token frequencies reflect entrenched forms. From a conceptual level, this methodology maps well onto previous work in dialectology; an exploration of grammar overlap situated within the learning process remains a question for future work.

1.5 Modeling Variation: Classification and Similarity

Given a grammar and a corpus of usage, our next challenge is to model variation in the entrenchment of that grammar for the group which produced that corpus. There are two basic approaches to this problem: classification (more common in computational work) and similarity measures (more common in dialectometry). Here we draw on both types of model and it is worth thinking through the essential differences between these models of grammatical variation.

The idea behind a classification approach is that we have multiple groups which we hypothesize will differ in the entrenchment of constructions: different dialects, for instance. The classifier takes these group labels as a given, never directly evaluating their validity. The classifier is instead focused on finding parts of the grammar that can reliably distinguish between the given groups: what is the difference between American English and British English grammar, for example, such that we can reliably predict for any given sample whether it belongs to one or the other dialect? Variation is ultimately about linguistic differences between groups and classifiers are the most robust computational model available for finding and characterizing differences.

There are two main advantages to a classification approach: First, classifiers can work in high-dimensional feature spaces and are not troubled by overlapping or correlated features (which many constructions are by definition). Second, classifiers come with a ground-truth evaluation: how accurately can they predict dialect membership? At the end of the modeling process, we can measure precisely how well the classifier works and we can evaluate the relative magnitude of variation in different parts of the grammar.

But there are some disadvantages to a classification approach as well: First, the groups must be defined in advance and there is no direct mechanism for saying that a sample is partly British English and partly American English. We can use a classifier to simulate similarity values and we can conduct an analysis of errors; but no sample on its own can straddle the category boundary. Second, a classifier requires training data that takes the form of samples from the corpus together with their label. Actual variation emerges from the kinds of exposure a learner encounters. It is not the case that a human first has equal exposure to all dialects and then acquires their own dialect by selection. Thus, while quite powerful as a model of variation a classifier is somewhat unnatural in that it is exposed to both samples and labels. On the other hand, this difference is perhaps not so strong because human learners, also, can guess the group memberships of their interlocutors. This is especially the case if dialect perception is indeed robust, so that speakers can intuit the dialects they are exposed to. At any rate, it is the supervised nature of classifiers that makes them both a powerful but also somewhat unnatural model of variation.

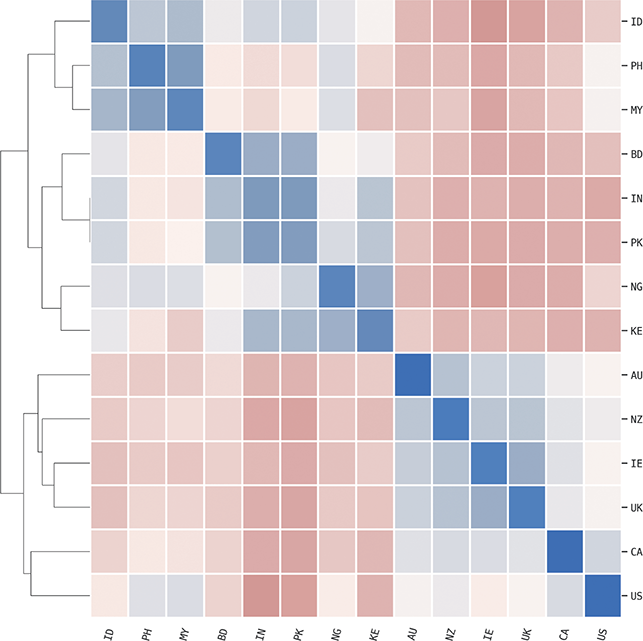

An alternate approach is to calculate pairwise similarity values between individual samples, so that labels like American English are not included in the model. This is an unsupervised approach, not trained with examples but allowing variation to emerge naturally as the difference between pairs of samples. Similarity measures are pairwise: for instance, between one sample of American English from Chicago and one sample of British English from London. By sampling many pairs from the underlying population we can construct confidence intervals on the similarity between the grammar of these dialects themselves.

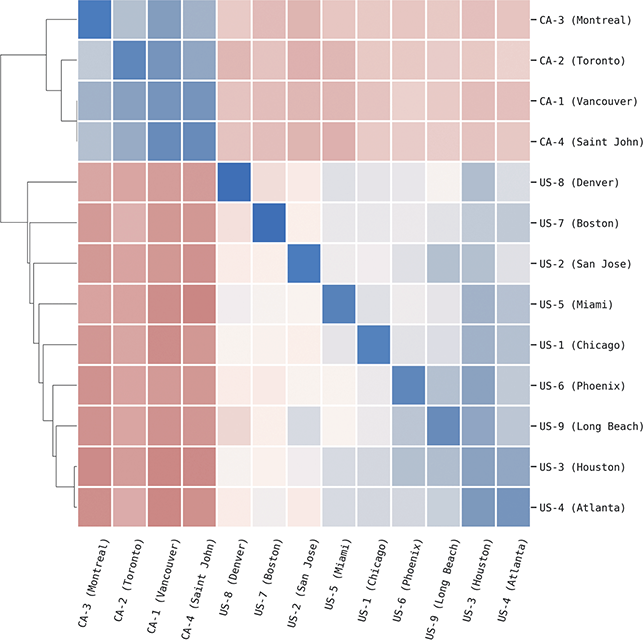

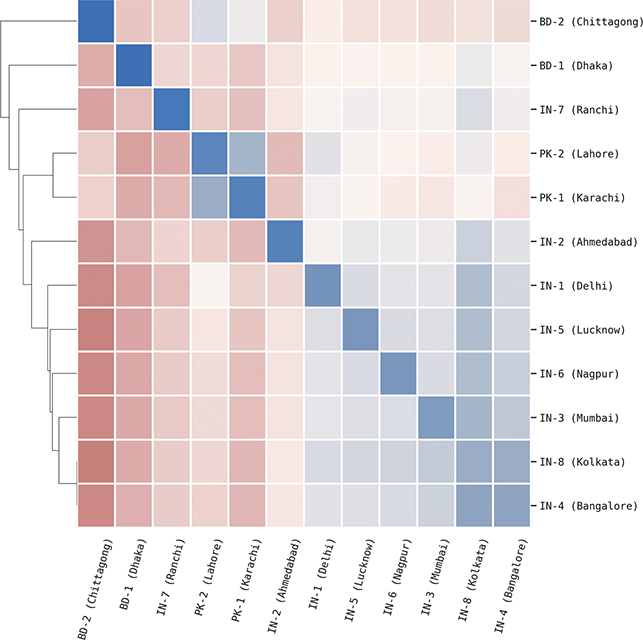

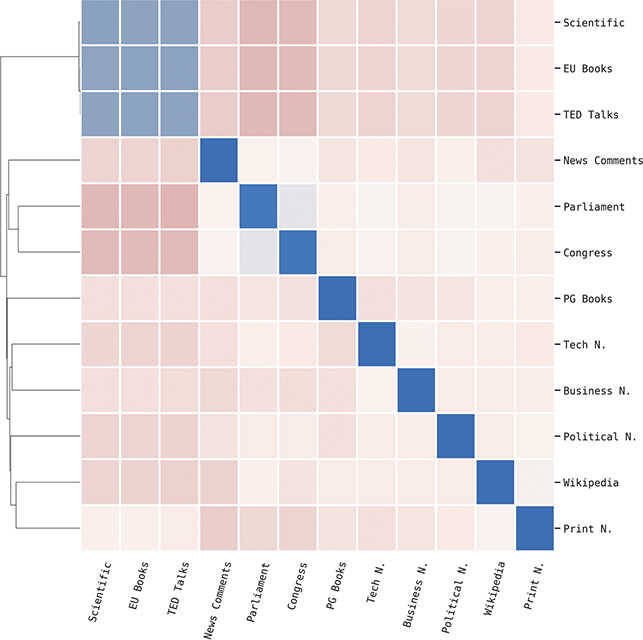

The scale of similarity estimates, however, makes them difficult to interpret on their own. For instance, in this Element we work with 304 local populations distributed across fourteen countries. This creates a tremendous number of pairwise similarities between local dialects (46,360 to be precise). We thus make sense of these similarities by creating a graph structure in which each local dialect is a node and the similarity between them within some part of the grammar is the edge weight.

The advantage of a similarity-based approach is that we make no assumptions about labels: the ontology of dialects is discovered, not assumed. For example, we conduct an accuracy-based validation of all similarity measures used in this Element which checks to see if samples from the same condition (i.e., the same individual or the same dialect) or more similar to one another than to samples from another condition. Thus, this validation step ensures that each individual or dialect or register does, in fact, have a unique grammar. Further, we can measure homogeneity and heterogeneity within dialects more directly because individual samples can be placed between categories. Thus, we could see that one local region is situated halfway between two standard national dialects like American and British English. This is the reason that dialectometry has often relied on similarity values.

But there are a few disadvantages as well. In the first case, an unsupervised approach views all features as equal contributors to similarity; this means that the signal of variation can be overwhelmed by the noise of unvarying parts of the grammar. Put another way, a classifier can pick a varying construction out of a haystack, but a similarity measure will be prone to overlooking small differences. The larger the feature space, the more true this becomes. In the second case, similarity measures do not have a direct ground-truth evaluation unless we happen to have participant-based ratings of dialect similarity, which are themselves not a direct view of differences in dialect production. And yet it is essential that we have some measure for how good the model is. Thus, the most common approach is to evaluate similarity measures using a classification task: for instance, what percentage of samples of American English are most similar to other samples of American English? The important point is that even unsupervised models must be evaluated before they are interpreted.

From a practical perspective, classifiers scale very well over a large number of samples, while similarity measures can be troublesome in large datasets. For instance, training a classifier with five groups each with 100 samples is not much different than training a classifier with 20 groups each with 1,000 samples. And yet the number of pairwise comparisons to make in a similarity-based approach grows very quickly. The second case involves many, many more comparisons than the first. A common solution is to sample a fixed number of comparisons per group, for efficiency. Thus, we might calculate a thousand pairwise similarities between each dialect; this improves but does not remove the tractability problem.

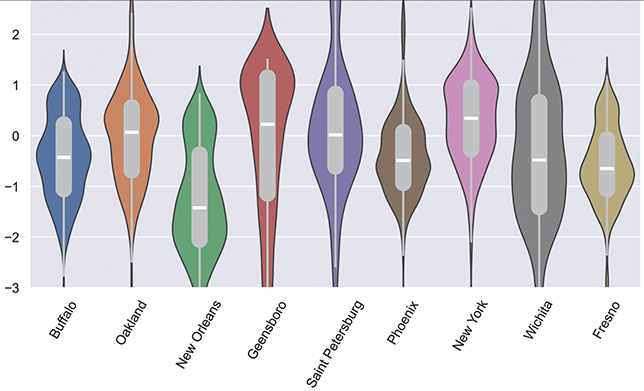

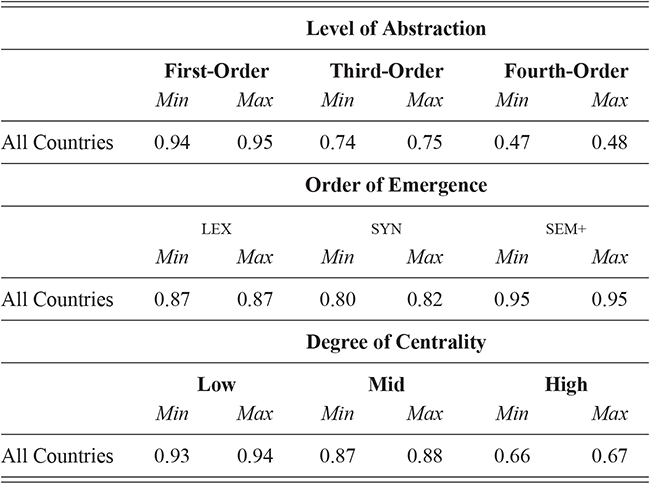

The output of a similarity-based approach is thus a distribution of pairwise similarity measures between groups. We could simply take the mean of this distribution, but that would erase potentially important information. A realistic similarity-based approach, then, requires thinking about dialectal variation as a second-order set of distributions: the difference between American English and British English is a not a single measure (like 0.59) but rather a distribution of such measures, a sample from the underlying population. Here we use a sample of 1,000 pairwise comparisons and then calculate the Bayesian mean with a confidence interval of 95% to get the minimum and maximum similarity for each comparison.

If we work with similarities, we end up with a distance matrix in which each group has a similarity/distance to every other group within a given portion of the grammar. This can be viewed also as a graph so that graph-based measures can be calculated upon it. For instance, if we had 20 dialect groups this would give a distance matrix with 190 cells (ignoring self-similarity and assuming that syntactic similarity is symmetrical). This then needs to be converted into a graph where each dialect is a node and each part of the grammar is a type of edge and that edge weight is the estimated similarity (itself a distribution and not a single measure).

To summarize, we rely on two types of models to study syntactic variation: classifiers (supervised) and similarity measures (unsupervised). We evaluate the quality of both types of models using a prediction task, thus providing accuracy by class (like dialect) and by feature (like highly abstract constructions). Classifiers provide feature weights that tell us what parts of the grammar are in variation. They also provide error analysis to tell us what groups are easily confused (a confusion matrix). We primarily use classifiers to measure the magnitude of variation at each level of community structure in each portion of the grammar: for instance, where is syntactic variation located in the grammar? Similarity measures provide an estimated distance matrix which compares each group (like dialect) with every other group and with itself. This distance matrix is quite large at the scale of our experiments, so we further view this is a graph structure with nodes and edge weights. We primarily use similarity measures to take a more nuanced view of variation and to understand how diffusion operates across the network structure of the grammar itself.

1.6 Corpora: Observing Unelicited Production

For the experiments in this Element we use unelicited written corpora as evidence of the linguistic production of both individuals and groups of individuals. By unelicited we mean that these are naturally occurring texts that were created without any interventions by researchers (unlike dialect surveys or interviews, for instance). By production we mean that these corpora provide a sample of language use but no sample of dialect perception.

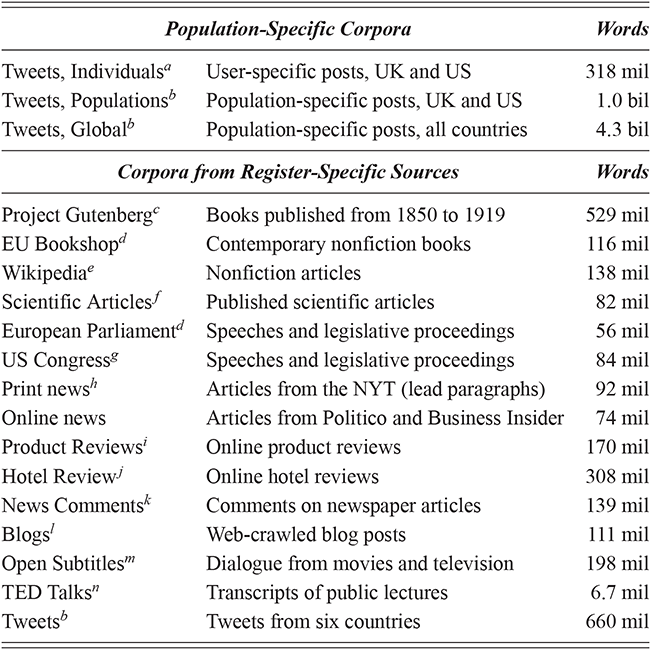

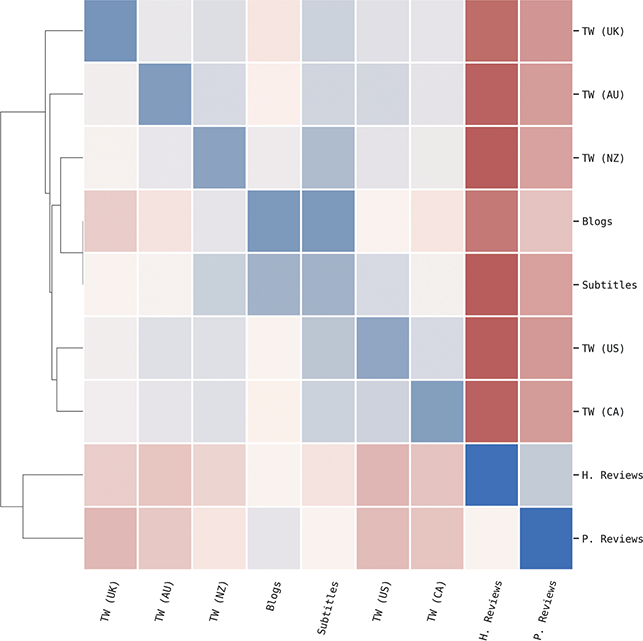

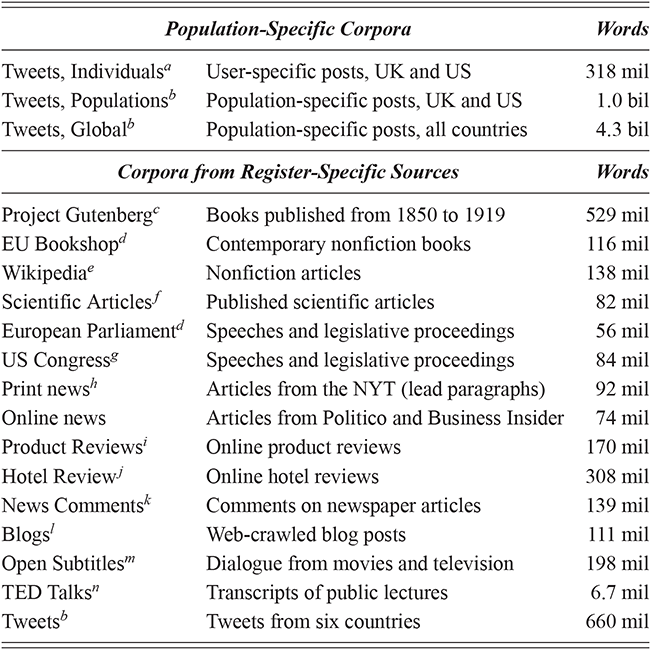

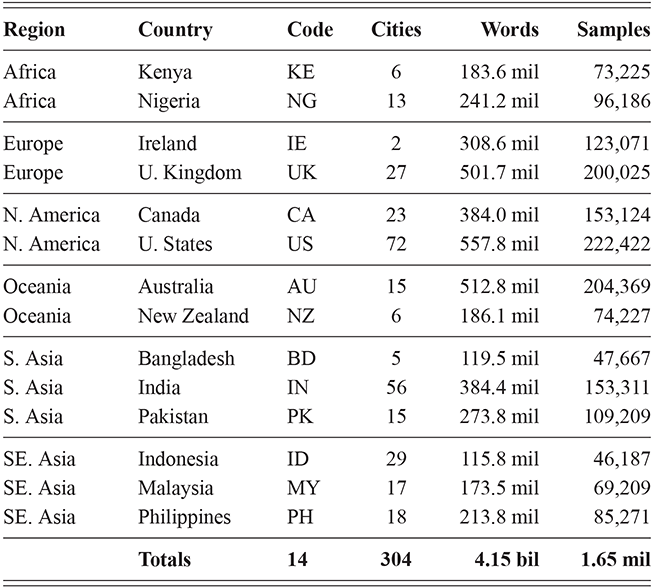

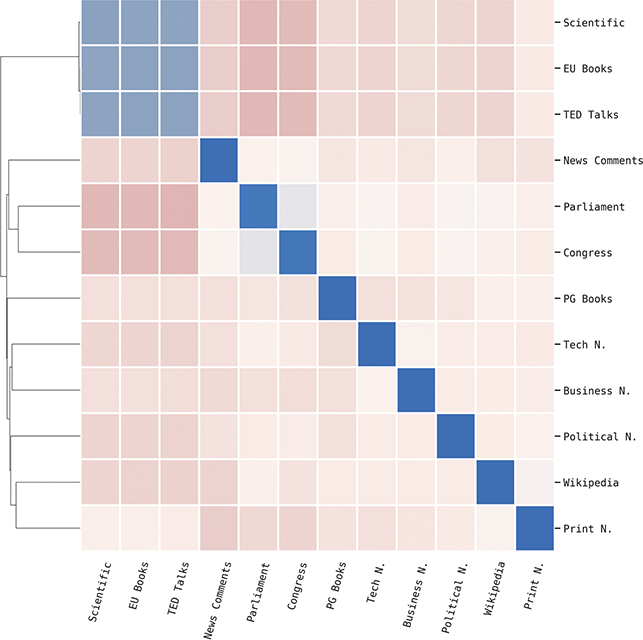

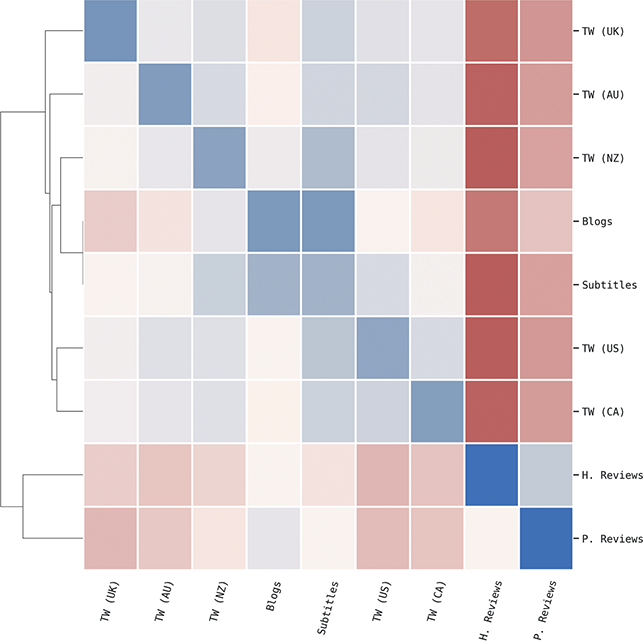

This section describes the two types of corpora used in these experiments: First, geo-referenced corpora which provide samples of the production of unique local populations; for this we use social media data (tweets). Second, register-specific corpora which are used to sample production within specific contexts; for this we use corpora representing a range of formal and informal contexts, from novels to newspaper comments. These corpora are listed by type in Table 1, with a brief description along with the number of words in each. A more detailed discussion of the methods involved in creating geo-referenced corpora follows in Section 1.7.

aGrieve et al. (Reference Grieve, Montgomery, Nini, Murakami and Guo2019)

bDunn (Reference Dunn2020)

cRae, Potapenko, Jayakumar, and Lillicrap (Reference Rae, Potapenko, Jayakumar and Lillicrap2020)

dTiedemann (Reference Tiedemann2012)

eOrtman (Reference Ortman2018)

fSoares, Moreira, and Becker (Reference Soares, Moreira and Becker2018)

gGentzkow, Shapiro, and Taddy (Reference Gentzkow, Shapiro and Taddy2018)

hParsons (Reference Parsons2019)

iZhang, Zhao, and LeCun (Reference Zhang, Zhao and LeCun2015)

jLi (Reference Li2012); McKenzie and Adams (Reference McKenzie and Adams2018)

kKesarwani (Reference Kesarwani2018)

lSchler, Koppel, Argamon, and Pennebaker (Reference Schler, Koppel, Argamon and Pennebaker2006)

mLison and Tiedemann (Reference Lison and Tiedemann2016)

nReimers and Gurevych (Reference Reimers and Gurevych2020)

All corpora are divided into sentence-level units,Footnote 3 with tweets assumed to each contain a single sentence. In cases where the language of a sample is in question (i.e., with tweet collection), only samples identified as English by two state-of-the-art language identification models are retained (Dunn, Reference Dunn2020; Dunn & Nijhof, Reference Dunn and Nijhof2022). The same pre-processing is used for all corpora: removing non-alpha-numeric characters, case folding, separation of characters joined by punctuation (i.e., country’s becomes country s), and removal of common templates like URLs and currencies.Footnote 4 This produces corpora which are comparable, with low-level orthographic differences like punctuation or capitalization which vary by register having been removed.

The advantage of a computational approach is scale: we can work with many populations across many contexts of usage. The disadvantage is meta-data: we know less about the demographics and the identity and the attitudes and the general cognitive abilities of each individual participant. For instance, we might have two speakers from the same local dialect, one who identifies closely with that local area and one who identifies as a global citizen without the same local attachments. We work with corpora from two conditions: first, aggregated corpora in which each sample represents an arbitrary selection of language users from the same place and, second, individual corpora in which each sample represents the production a single language user. We can use the individual-specific corpora, for example with measures of homogeneity, to determine how much internal variation there is within each local population.

Regardless, our analysis is not able to take into account what parts of the local population first adopt variants or refuse to alter their production to match the larger community. These kinds of questions require meta-data that is not available. But we can aks questions about (i) whether diffusion occurs equally across all nodes in the grammar; (ii) whether variation is stronger in the center or the periphery of the grammar; (iii) whether register variation is located in the same regions of the grammar as dialectal variation; and (iv) whether outer-circle communities vary in the same ways that more well-studied inner-circle communities vary. These are important questions which are not possible to ask without sufficient a scale of observation. And yet the trade-off of such scale is that we have less knowledge about perception and about language attitudes.

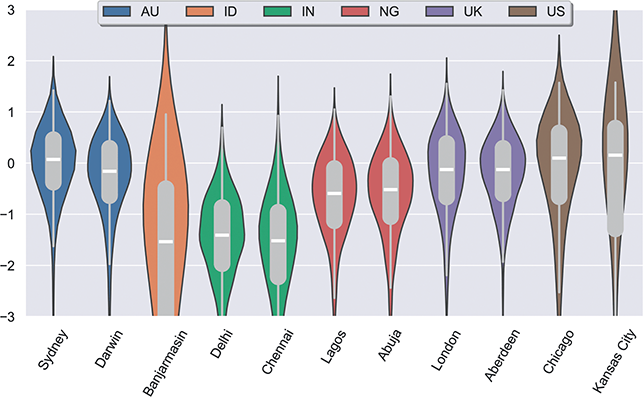

1.7 Networks: Structure within the Population

If variation is driven by our unique linguistic experiences, then differences in exposure will lead to differences in production. We have previously discussed the grammars and the data to be used; here we consider in more detail how to view the speech community as a network given geographic corpora. Geo-referenced social media posts (tweets) are used to represent the production of both (i) individuals and (ii) the background populations from which those individuals are drawn. Thus, we have corpora whose samples are aggregated tweets from just one person and corpora from the same places whose samples are tweets aggregated across many individuals. When we work with individuals vs dialect groups, we focus only on two inner-circle varieties (US and UK English). When we work with dialect groups alone, we focus on global data that includes many outer-circle populations from a total of fourteen countries.

The geographic social media corpora are constrained to the local areas around airports, as a proxy for urban areas: within 50km for the UK and within 50km or adjacent counties for the US. These approaches to spatial selection are governed by the meta-data available from the two existing corpora used: one collected between 2014 and 2017 (Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Montgomery, Nini, Murakami and Guo2019) and one between 2018 and 2022 (Dunn, Reference Dunn2020). The spatial areas represented in the two data sets overlap but the time period does not, so that there are no duplicate observations and no duplicate threads between the two corpora. This means that no portion of the individual-specific corpora is duplicated in the aggregated corpora.

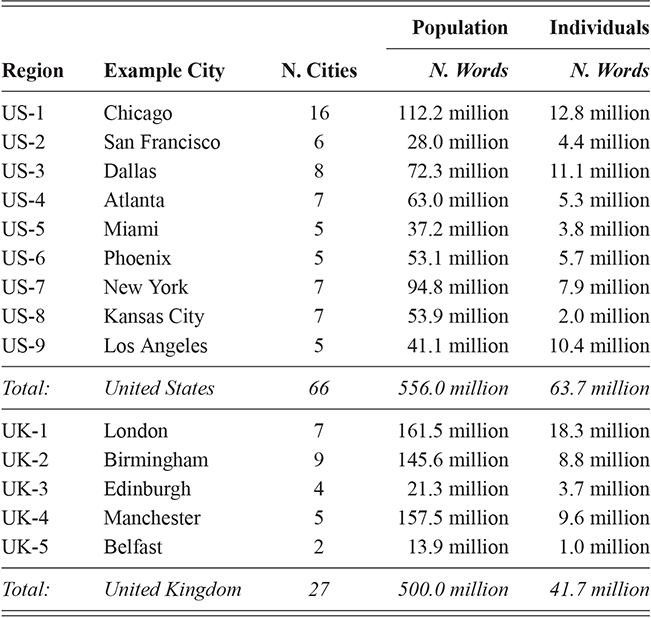

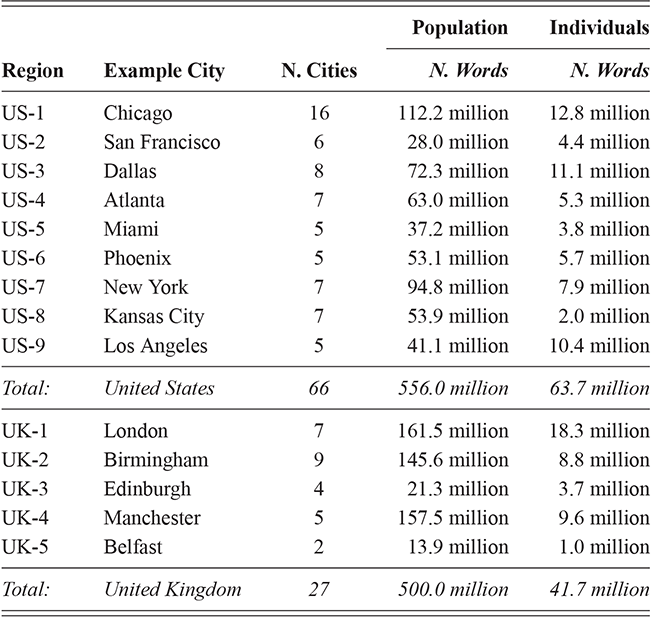

The first corpus (2014–2017) is used to represent individuals: any single user who produces at least 50k words is included. Tweets are aggregated into samples of at least 2,500 words; thus, each individual is represented by at least 20 samples. This corpus contains samples from 6,744 individuals across the US and UK. The second corpus (2018–2022) is used to represent the local populations to which those individuals belong. This corpus represents the same locations in the US and the UK (c.f., Table 2), but at a different time period so that no samples overlap. While the adjacent time periods ensure there is no overlap in specific communicative situations (e.g., threads of tweets), the distance in time is short enough that we would not anticipate any grammatical change to have occurred between the two periods. This second corpus is also divided into samples of 2,500 words, with tweets from the same place being combined into samples.

These two data sets are thus comparable in every way except that one is aggregated by individual and one by time and place. We take this to represent both (i) variation across individuals from the same population and (ii) variation within the larger populations from which those individuals are drawn. The overview of the corpora is shown in Table 2: the US is divided into nine regional dialects and the UK into five. Each region is composed of multiple metro areas; note that all data here is collected from urban areas to avoid rural-urban divides in density. The corpora representing populations are the largest (at 554 million words for the US and 471 million for the UK), though the corpora representing individuals remain large as well (at 182 million words for the US and 135 million words for the UK).

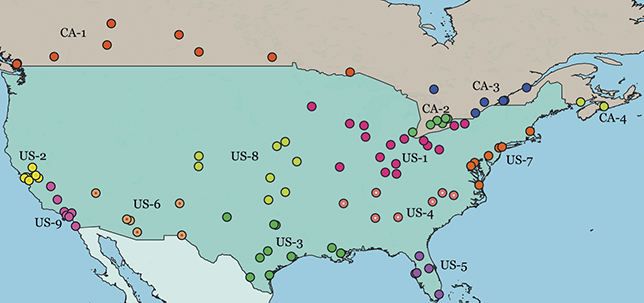

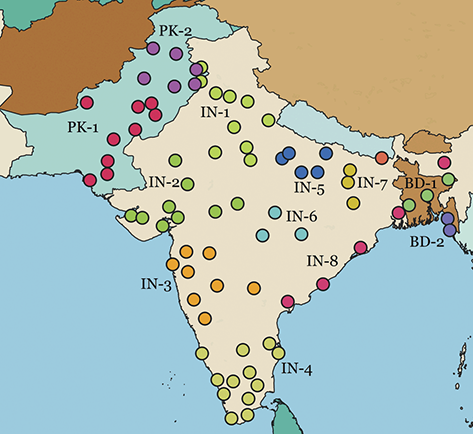

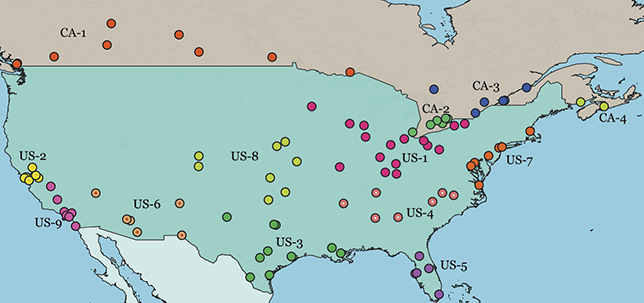

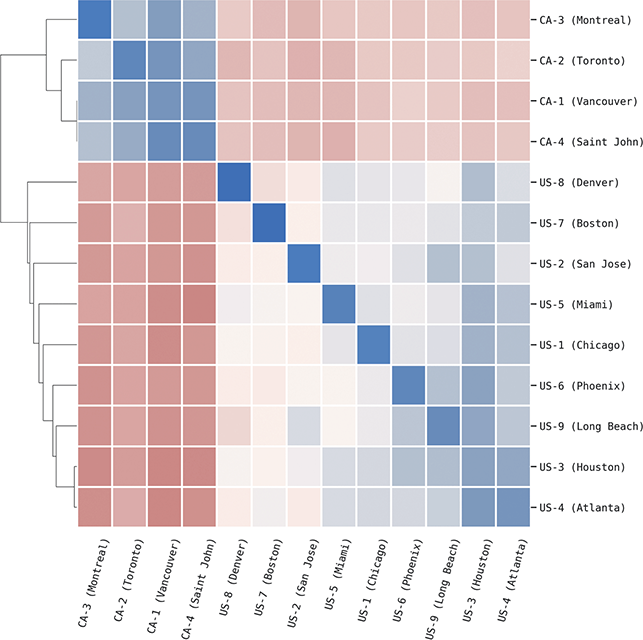

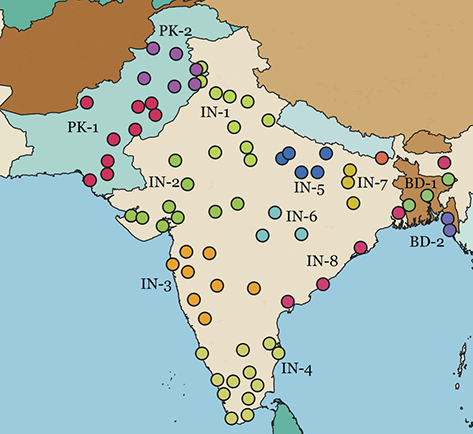

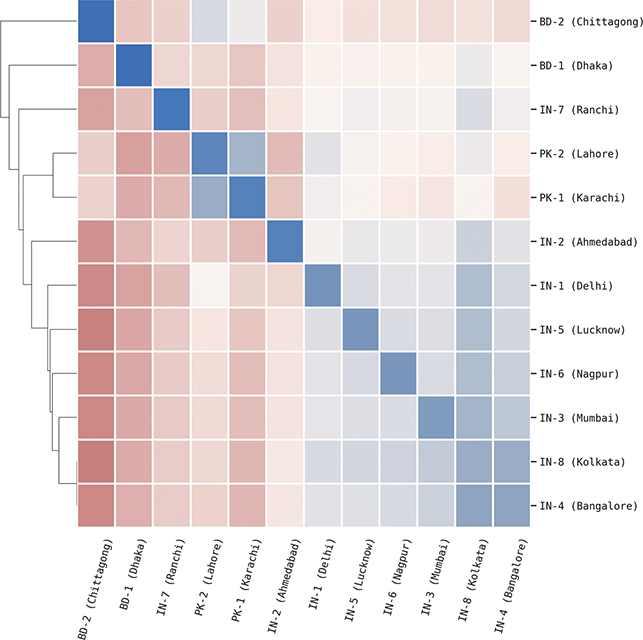

Local populations are represented by the nearest airport; because of ease of movement within urban areas, this city-level grouping is the most fine-grained spatial distinction available from corpora. This spatial hierarchy has three tiers: (1) the country (US vs UK), (2) the region (Midwest vs West Coast), and (3) the specific metro area (e.g., Indianapolis vs Chicago). The first and third levels are pre-defined because they derive from nation-states and city locations. For the second, we use the density-based H-DBSCAN algorithm to clusters metro areas into regional groups (Campello, Moulavi, & Sander, Reference Campello, Moulavi, Sander, Pei, Tseng, Cao, Motoda and Xu2013; Campello et al., Reference Campello, Moulavi, Zimek and Sandler2015). A refinement of the DBSCAN, this algorithm groups points spatially into local clusters, where each point is an airport. The result is a set of regional areas within a country. For example, the nine areas within the United States are shown in Figure 2, where each color represents a different group. Manual adjustments of unclustered or borderline points is then undertaken to produce the final clusters; these are visualized and available as spatial files in the supplementary materials.

Figure 2 Map of local populations represented in the US and Canada.

This three-level hierarchy of populations is shown in Table 2, with US regions on the top and UK regions on the bottom. An example city is given for each region id, drawn from the most frequent city within each region. Thus, the region US-1 refers to the Midwest, with the exemplar city being Chicago. The number of metro areas within each region is also shown; for example, US-1 contains sixteen metro areas, each defined geographically by its airport.

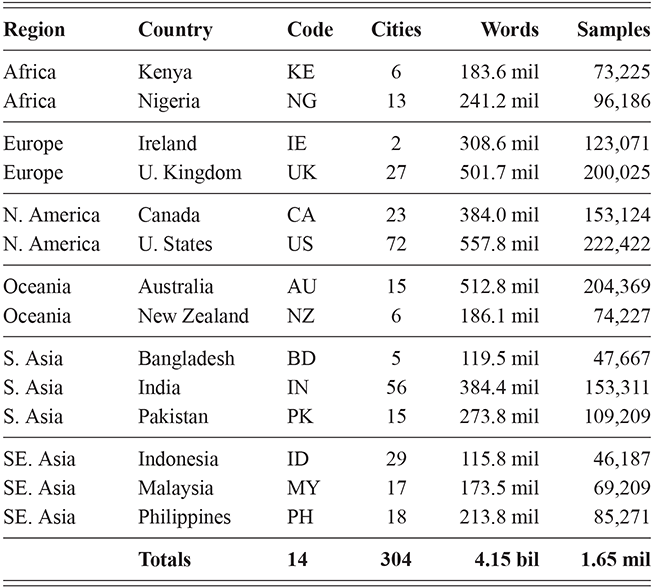

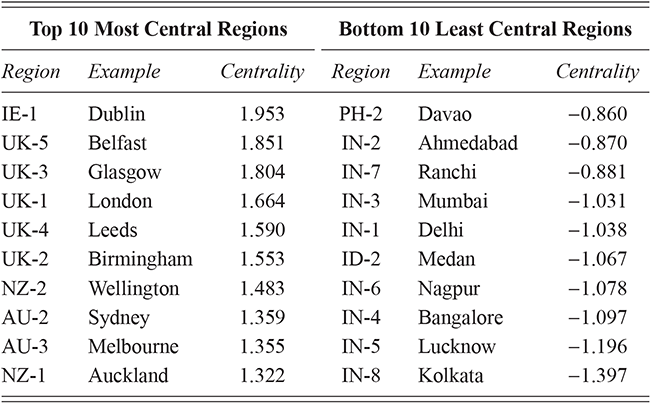

The corpora used for global variation in English is an expansion of the population-based corpora described above, but including more countries around the world. It thus follows the same three-tiered spatial organization: by country, by region, and by local metro area. Regions are again based on spatial clustering. This leads to corpora representing 14 different countries, with a total of 304 local metro areas grouped into 54 regions, as shown in Table 3. The corpus as a whole has 4.16 billion words or 1.66 million samples. Some countries are better represented than others, however: the US, UK, and India all have over 250k samples while Cameroon has only 4.9k and Uganda 3.3k. For this reason we are careful to measure confidence bounds for each estimated similarity value, so that areas with fewer samples are not represented by a simple mean if there is high variance present.

To summarize this section, we have three variants of tweet-based corpora which operationalize the population network in different ways: (i) individual-specific samples from the US and the UK divided into local areas; (ii) population-level samples from the US and the UK divided into the same local areas and not overlapping in time; (iii) population-level samples created in the same manner as the second corpus but containing samples from fourteen countries in order to provide a more realistic global model of variation in English.

2 Variation across Individuals

We turn now to our first case-study: individual variation within local populations in the US and UK. We start by presenting a usage-based view in which the unique linguistic experience of individuals leads to unique grammars. The case-study itself focuses on identifying individual differences and measuring where such differences are located in the grammar. We end by comparing individual-specific corpora with aggregated corpora from the same local dialects. Much work in computational sociolinguistics depends on aggregated corpora and this experiment allows us to validate the degree to which aggregated and individual-specific samples agree on the uniqueness of local dialects.

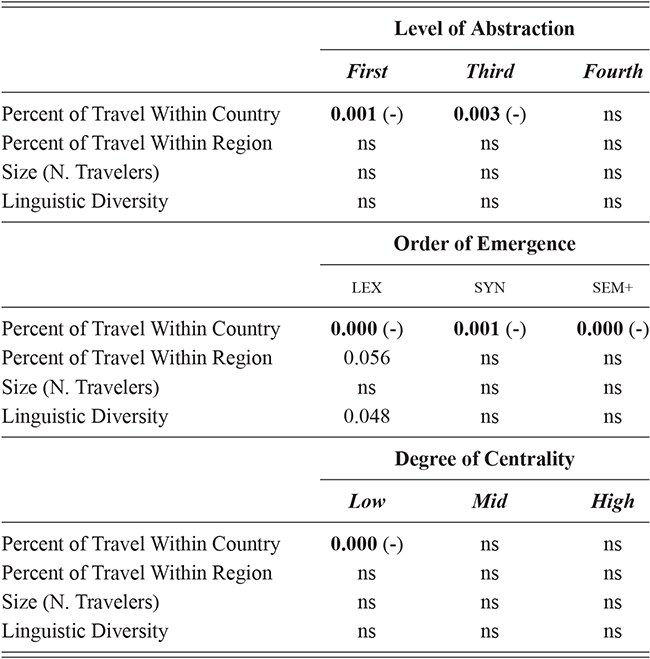

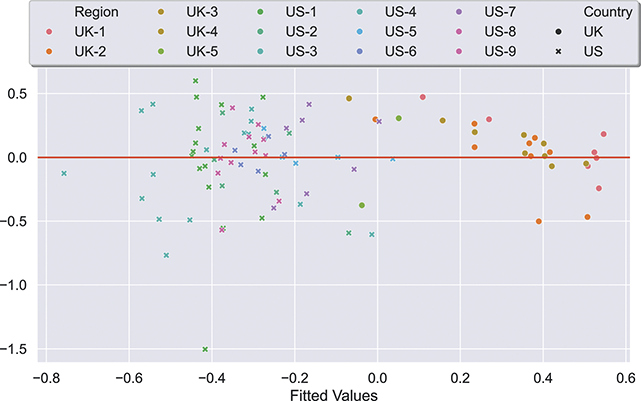

We start by using classification-based experiments to measure the magnitude of individual variation and determine where in the grammar it is located. To do this, we train separate classifiers for each city to identify individuals from that city. Thus, we are relying on different nodes within the grammar to distinguish between individuals from the same local dialects producing language in the same register. We then use similarity-based experiments to model the structure of variation without training samples. We use the homogeneity of individuals from the same population as a measure of the amount of individual differences. We then undertake a regression analysis to determine whether factors like population contact and language contact are able to explain why some local dialects are more homogeneous than others, where homogeneity means that speakers from a given population are more similar.

2.1 Individual Experiences Lead to Individual Differences

From a usage-based perspective, an individual’s grammar emerges given exposure to usage. In this context, usage is simply the production of other speakers. Two individuals from the same city are likely to have highly overlapping exposure: they experience the same local dialect, the same language contact situations, the same media sources, and so on. As a result, individual differences in the grammar should be weaker than population-based differences because the differences in exposure during learning are smaller within the same local population. Our operationalization of exposure is the observed production of others within the same register (social media).

We have divided the grammar into different types of constructions based on (i) the level of abstraction, (ii) the order of emergence, and (iii) the degree of centrality. Constructions are expected to be learned first as more concrete and item-specific representations which are then generalized into higher order constructions. Thus, we hypothesize that two speakers from the same local dialect should differ in the specific low-level constructions they are exposed to but should reach similar higher-order generalizations. In the same way, we hypothesize that constructions on the periphery are subject to individual differences, while constructions in the core of the grammar are more stable.

The presence of individual differences in the grammar has been to some degree ignored within linguistics, with its focus on forming generalizations about a language which require consistency within a speech community. The presence of individual differences, however, has been robustly established within the field of forensic linguistics which is focused precisely on leveraging individual differences for practical purposes (Nini, Reference Nini2023). Further, although much work seeks to generalize over individual differences, it remains the case that even experimental work must grapple with their presence (Kidd & Donnelly, Reference Kidd and Donnelly2020). From a usage-based perspective, however, such differences are expected because speakers have different levels of entrenchment for even those constructions which they share (Langacker, Reference Langacker1987). Beyond entrenchment, minor differences in slot-constraints can lead to constructions with slightly different patterns of production. Since each construction has many slot-constraints, this leads to a large number of minor individual differences in the grammar. If this usage-based view is correct, we should see high accuracy in lower-order constructions (learned directly from exposure) but lower accuracy in higher-order constructions (generalized on top of lower-order constructions).

2.2 Magnitude and Robustness: How Much Individual Variation?

We use a classifier to measure the magnitude and robustness of individual variation by comparing the production of different users within the same city. This kind of model learns to connect variants with individuals; the goal is to distinguish between samples that represent different users. Thus, a higher prediction accuracy indicates that there is more variation because individuals are more easily identified. In general, classes that are difficult to distinguish are more similar and those which are easy to tell apart are more different. We further use cross-validation to ensure that accuracy is consistent across different sets of samples, to avoid overfitting any one part of the corpus. More consistent accuracy across folds indicates that the variation is robust because it does not depend on a specific set of samples.

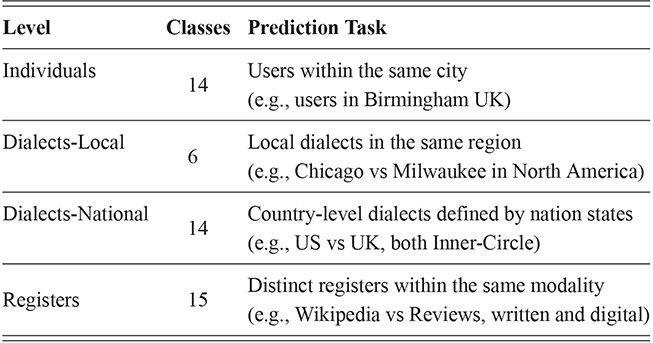

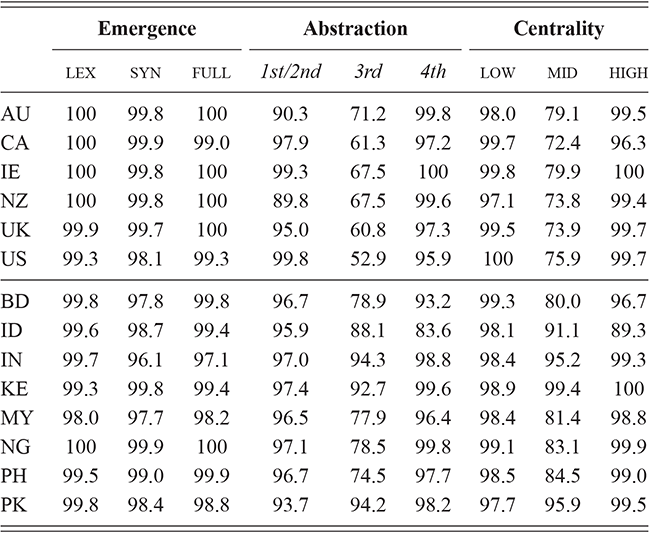

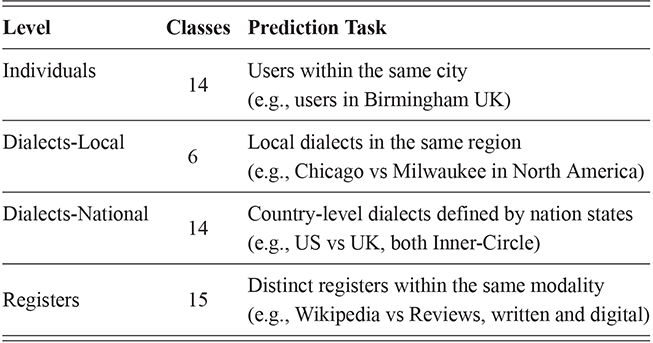

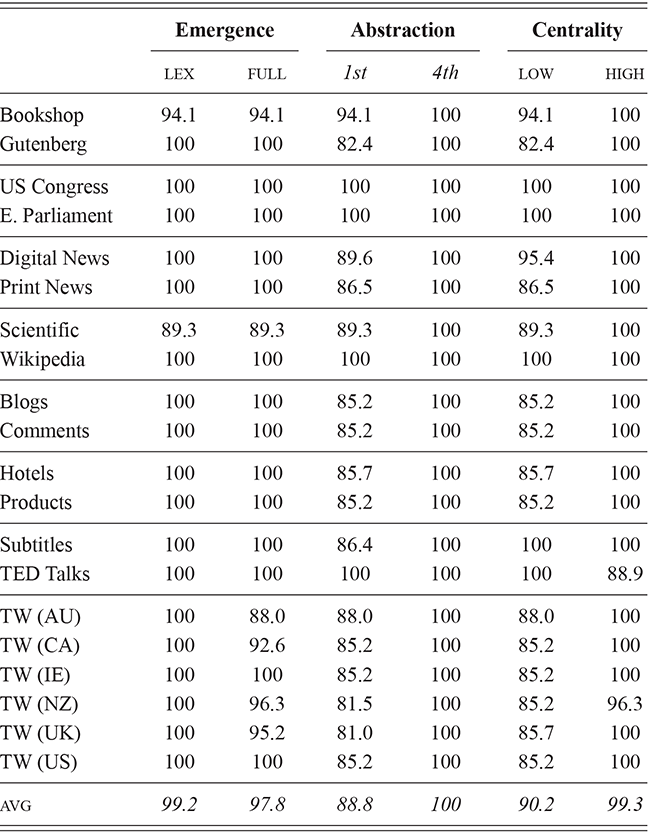

For this and future classification-based experiments, we use a Linear Support Vector Machine (SVM). The experimental design discussed in this section remains consistent across individual differences (users within the same city), local and national dialects (aggregated samples from different regions and countries), and context (samples from different written registers). This consistency makes it possible to compare the magnitude and location of each type of syntactic variation. A break-down of the range of classification tasks is given in Table 4, ranging from individual differences at the top to registers at the bottom. With the exception of local dialect classification, all levels of variation are constrained to the same number of classes to make the results directly comparable.Footnote 5

To support this comparison, we fix the number of individuals per city at fourteen, so that the number of classes can be the same across cities with different numbers of samples. For instance, Chicago is represented by almost 20x the number of individuals as Minneapolis; by constraining the numbers of users observe, we make these cities directly comparable. The task is to distinguish between fourteen arbitrary individuals from the same city. This task is then repeated ten times with different sets of individuals, as described below, to provide a better estimate of individual differences within each local dialect community.

The question is not just the magnitude and robustness of syntactic variation in written registers but also where in the grammar that variation is located. Thus, we train nine separate classifiers, one for each nodes within the grammar as shown in Figure 1. The prediction accuracy of each part of the grammar, measured using the f-score, allows us to observe the magnitude and robustness of individual variation across different portions of the grammar. The higher the prediction accuracy, the more variation there is in that portion of the grammar. Thus, if lower-levels of abstraction have a higher f-score, this means that individuals are more different in these more concrete constructions but more similar in abstract families of constructions.

Because we are working with large corpora, we are able to estimate classification accuracy across many samples. First, for each of the classification problems in Table 4 we take ten rounds that each work with a different sub-set of the data. For individual differences, this means that for each round we take a random sample of fourteen individuals from a given city. Thus, these results do not rely on a single small set of users. This replication of the experiment across ten rounds of arbitrary users allows us to calculate a confidence interval for the results. Within each round, we use five-fold cross-validation to estimate the classifier performance. This again provides a sample of classification accuracy across different permutations of the data within each round; cross-validation ensures that all samples rotate between the testing set and the training set so that the classifier does not over-fit a specific testing set.

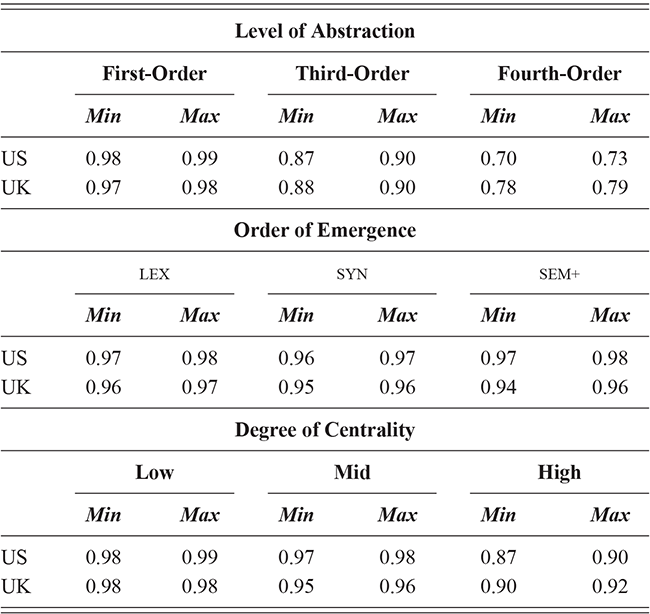

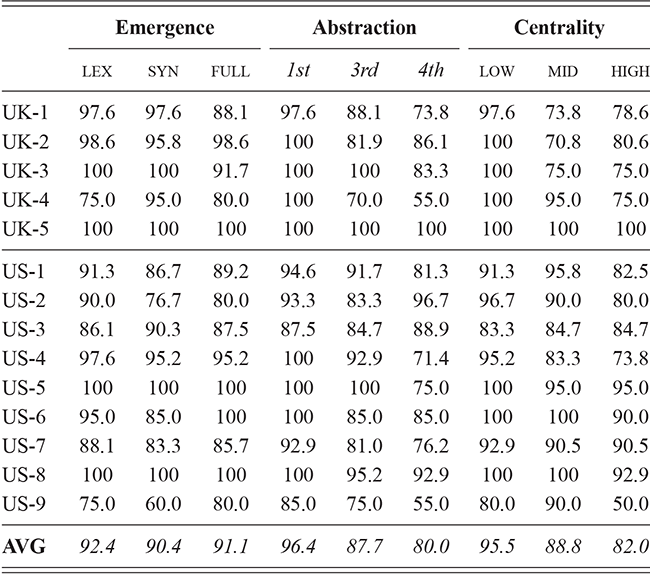

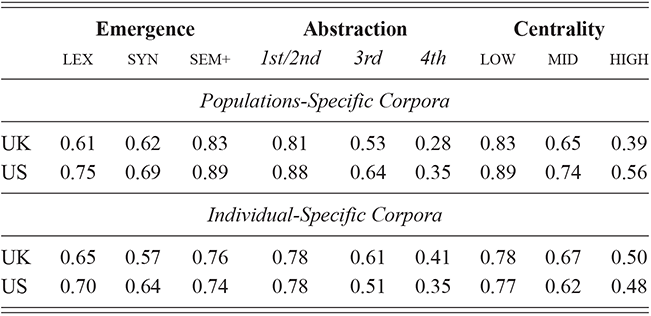

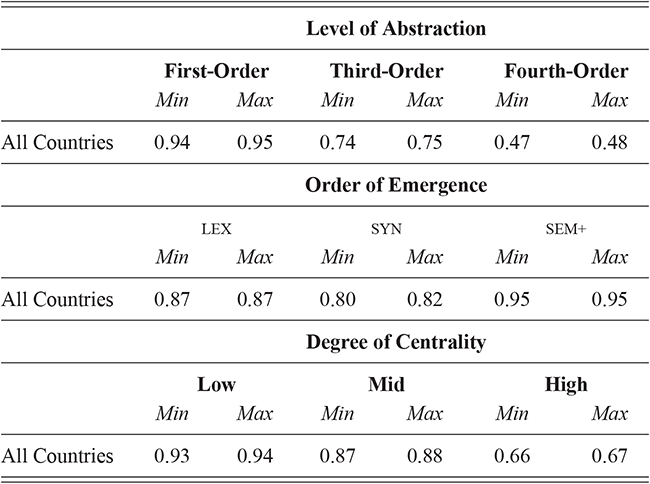

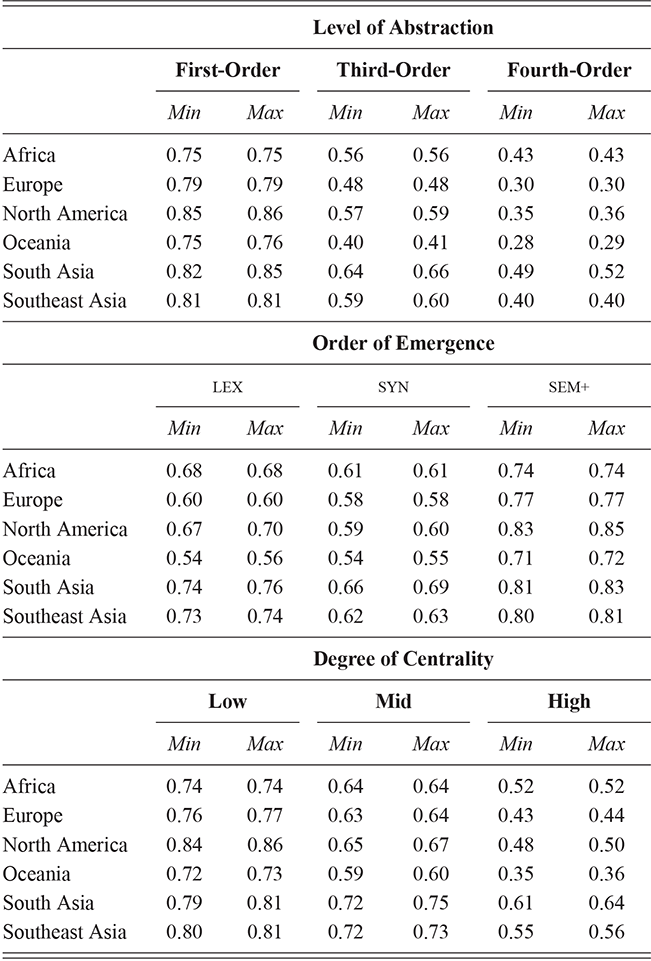

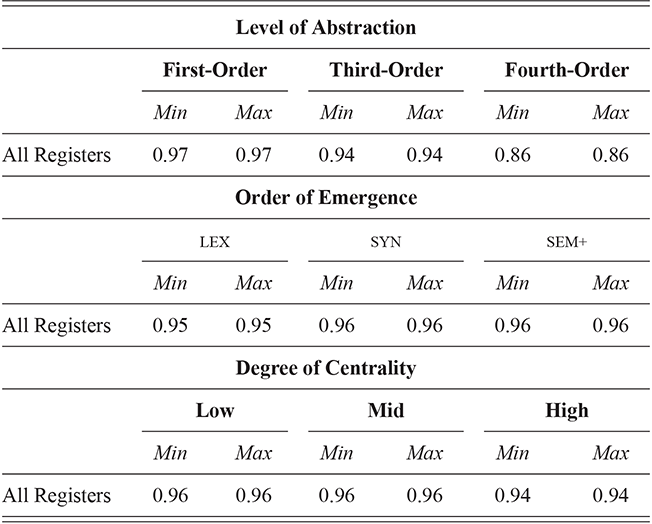

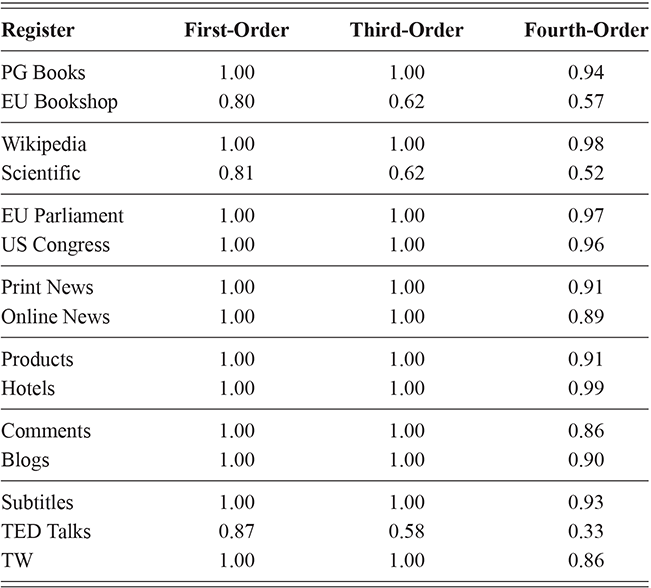

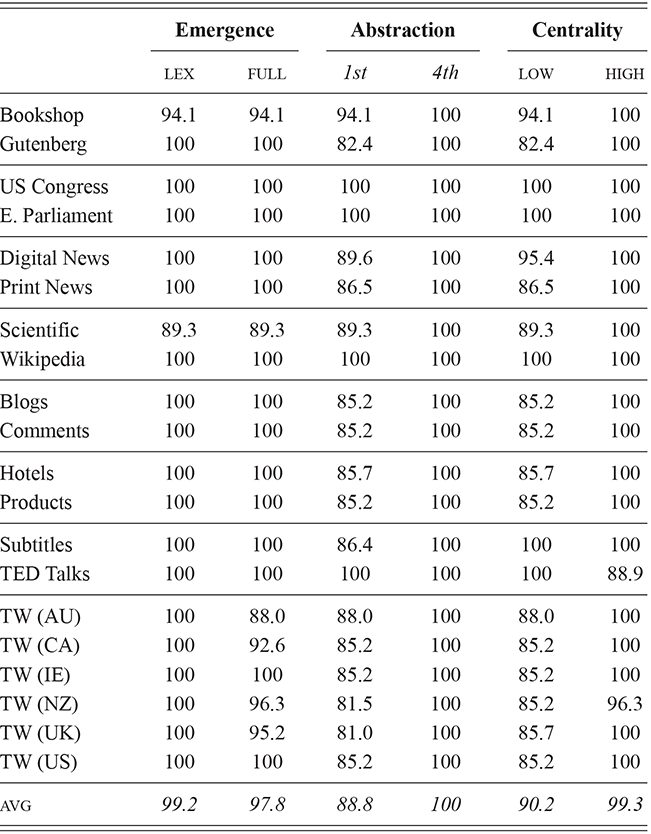

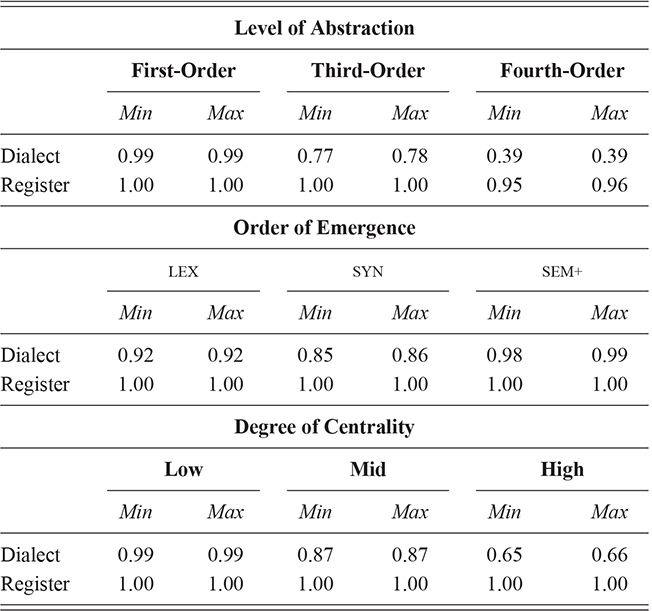

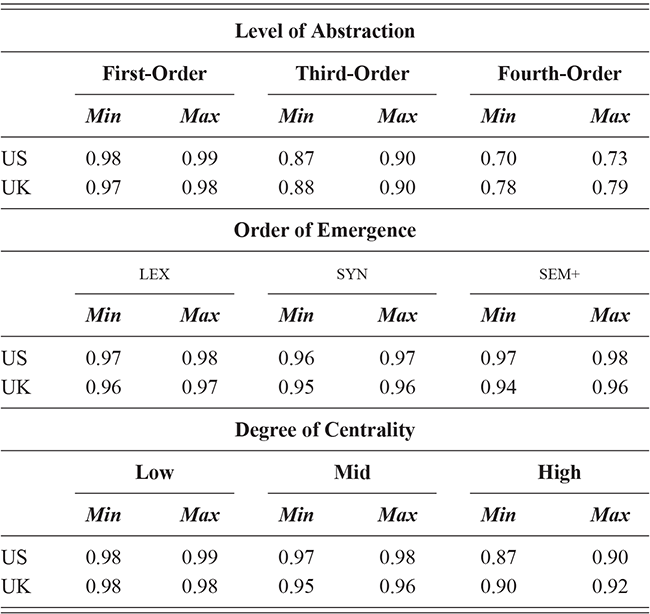

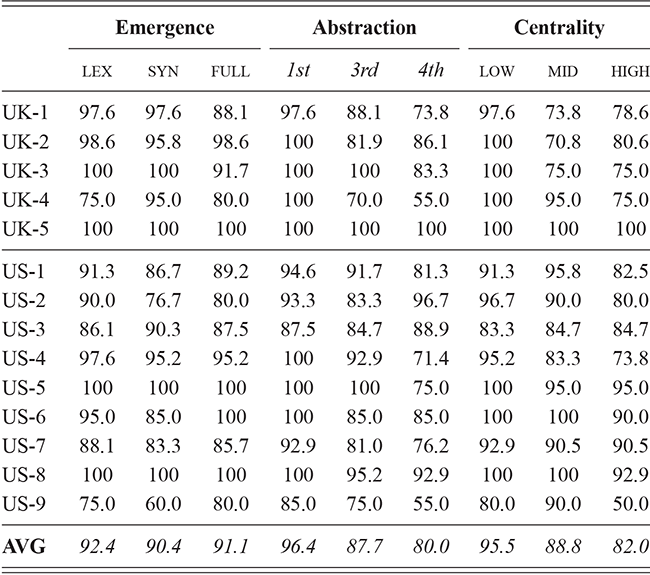

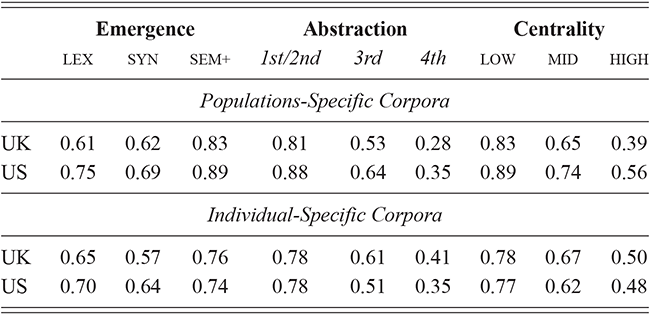

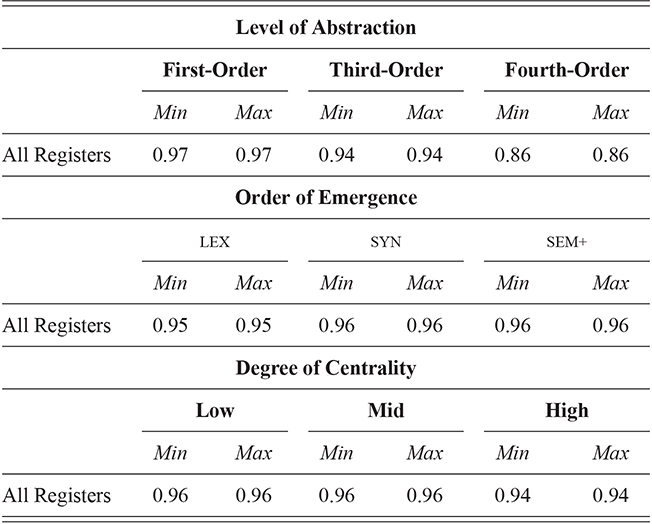

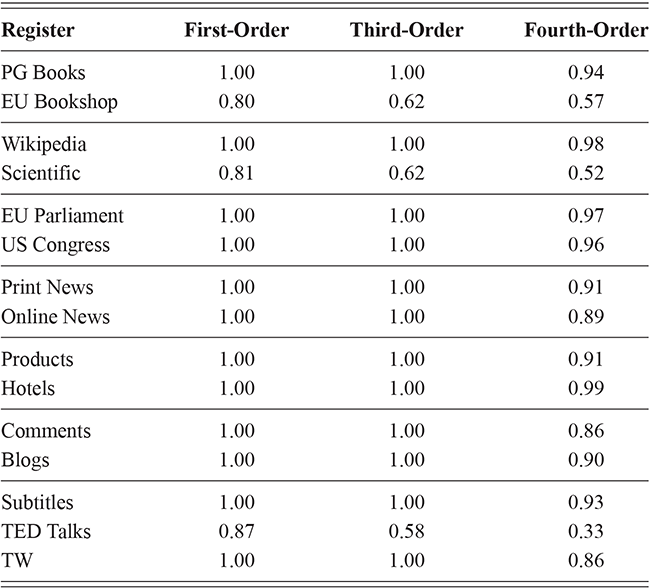

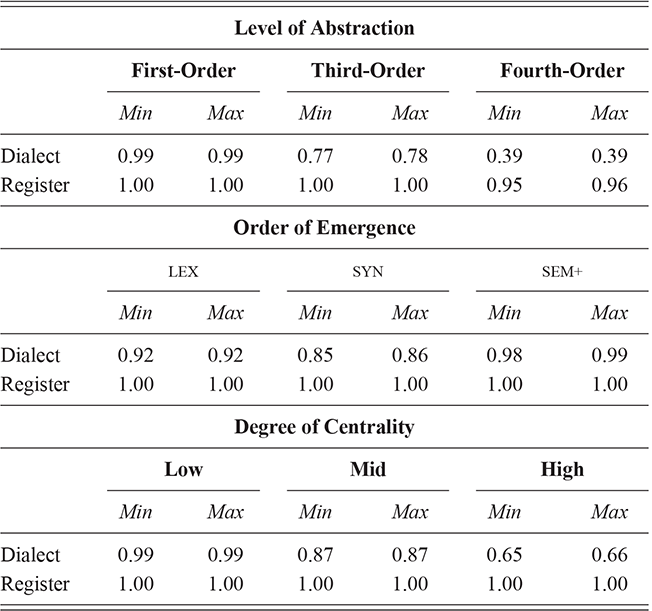

We thus are estimating classification accuracy across fifty individual classifiers for each city (ten by selection of users and five by cross-validation within each set of users). The reported values are a Bayesian estimate of the mean f-score with a confidence interval of 95%. For example, in Table 5, the f-score of individual classification using the first-order portion of the grammar has a minimum value of 0.98 and a maximum value of 0.99. This provides both magnitude (number of errors) and robustness (variation in magnitude). In other words, magnitude is the estimated prediction accuracy and robustness is the variation in prediction accuracy. The results in this table are aggregated by country; the full city-level results are available in the supplementary material.

With reference to the results in Table 5, it is clear that there is a tremendous amount of individual syntactic variation in written data representing these local dialects: even when drawing individuals from the same location the model is easily able to distinguish between them. In fact, one motivation for including similarity measures in this Element is that the sheer amount of variation leads to a ceiling effect for these classifiers: performance reaches the maximum possible accuracy in several conditions. Thus, these results show that the magnitude of individual variation within cities is high. Further, the robustness is also relatively high: we might expect, for instance, that some cities or some individuals would be distinct and thus easily identified, but that other cities or individuals would have lower accuracy. Here we see, however, that the minimum and maximum estimates (with a 95% confidence interval) are generally within one point. This means that our estimates of individual uniqueness are quite robust.

At the same time, we are aggregating across many cities in many regions of the US and the UK, and there are some exceptions to this level of accuracy. For instance, in London the cross-fold f-score for the high-frequency core constructions ranges from 0.89 to 0.94, a fairly wide range. In Newcastle, however, this range is only between 0.95 and 0.97. So, London has fewer individual differences in this part of the grammar than Newcastle. For our purposes, we are viewing individual differences within each city as a sample of the underlying population within each country; thus, the results in Table 5 are aggregated to show that country-level estimate. The point is that there is a great deal of syntactic variation even across individuals and even in written registers. A deeper exploration of city-level variation in the amount of individual differences follows in the next sections.

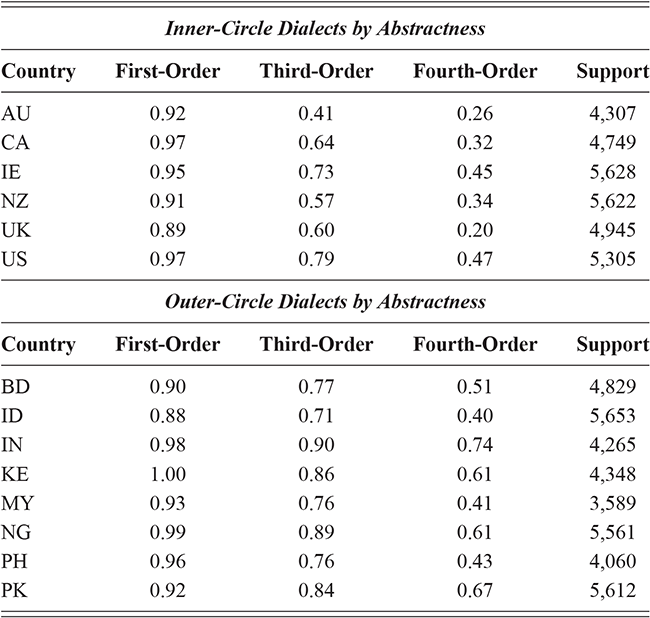

These country-specific estimates of the magnitude of individual variation show that individual differences are much stronger in specific parts of the grammar. Starting with level of abstraction, there is a consistent trend that more concrete (lower level) constructions differ more between individuals. First-order constructions (the most concrete) obtain a minimum f-score of 0.98 in the US and 0.97 in the UK. This high level of accuracy indicates that individuals are generally quite easy to tell apart given syntactic production. At the next level of abstraction, this minimum f-score falls to 0.87 (US) and 0.88 (UK), a significant drop. And, finally, within the most abstract constructions, the minimum f-score drops further to 0.70 (US) and 0.78 (UK). This means that individual differences across both dialects are concentrated in the most item-specific and surface-level constructions. Interestingly, the two dialects score quite closely until we reach fourth-order constructions, in which case the UK has a much higher score. This indicates that the US has fewer high-level differences than the UK.

For order of emergence, on the other hand, there is no significant difference between early-stage and late-stage constructions: the confidence intervals overlap. This means that a representation-based division of the grammar has no impact at all on the model, which in turn means that individual differences are not organized by order of emergence. Within degree of centrality, there is no difference between constructions on the periphery and those in the main part of the grammar. However, performance falls significantly for high-frequency core constructions (although not to the same level as highly abstract constructions). This means that within the core grammar there is less variation across individuals than in the rest of the grammar; this effect is smaller than for level of abstraction in terms of magnitude and robustness.

This section has used classification experiments to determine how much variation there is across individual users and how consistent or robust that level of variation is. Our first conclusion is that there is a tremendous amount of syntactic variation in these written registers. At the same time, this variation is not distributed evenly across the grammar: level of abstraction has a strong and significant impact, with most variation contained in more concrete and lower-level constructions. This effect is not seen at all for order of emergence and only slightly for degree of centrality. While all cases remain significantly higher than the baseline, this indicates that individual variation is concentrated in specific parts of the grammar network.

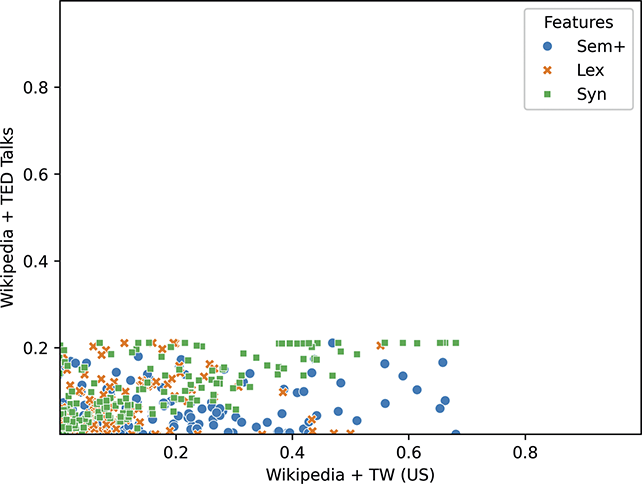

2.3 Evaluating Individual Similarity Measures

The results in the previous section relied on a classifier; in this section we detail the methodology for measuring similarity between conditions (i.e., between individuals within the same city). The distinction between these two approaches to variation, at a conceptual level, was presented in Section 1.5. Here we focus on the specific details of the similarity measures and then compare a classification-based and a similarity-based model of variation. Our focus here is on validating the similarity measures using a classification task: are individuals from one city more similar to one another than to individuals from other near-by cities? Thus, this validation task measures how much confidence we should have in these unsupervised measures; it looks much like a classification task, in that we are predicting categories (same vs different). However, the purpose is to ensure that the measure is valid before we dig deeper into individual differences in the next section. The combination of classifiers (supervised) and similarity measures (unsupervised) here provides converging evidence that further strengthens our understanding of syntactic variation.

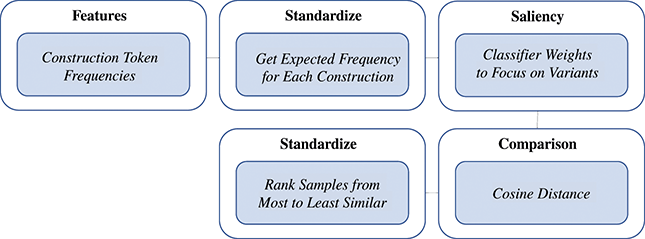

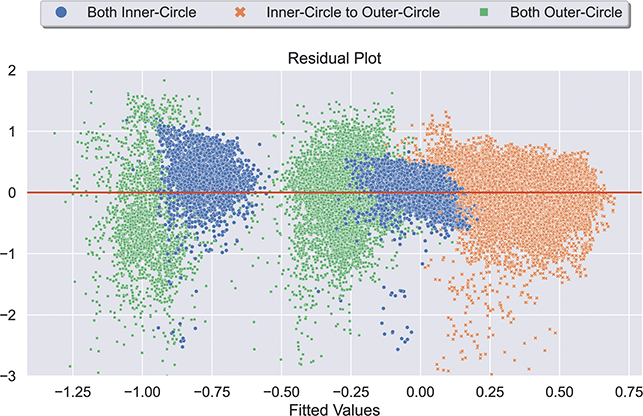

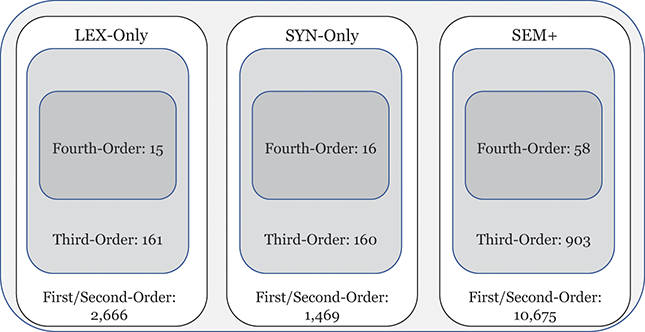

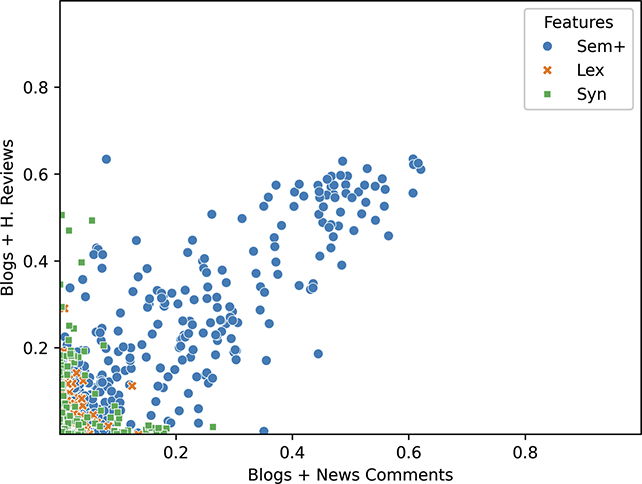

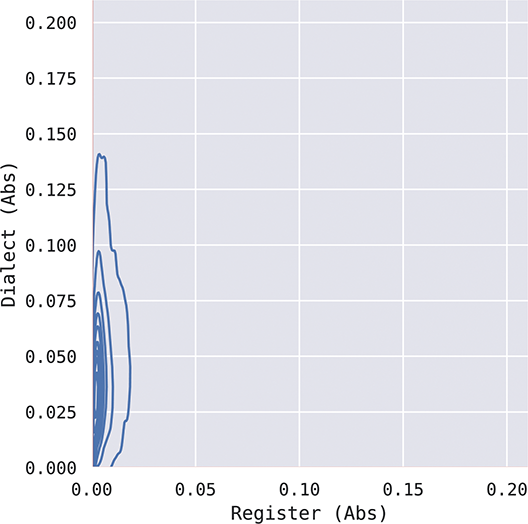

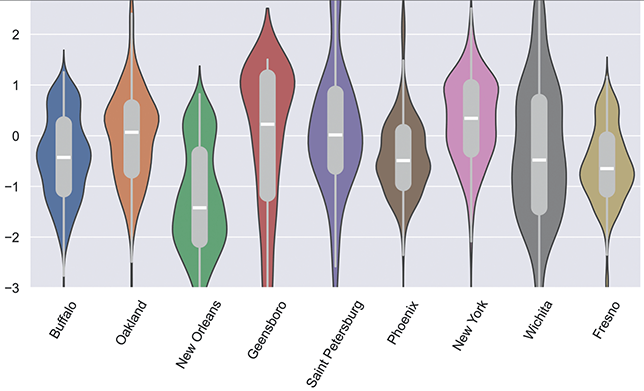

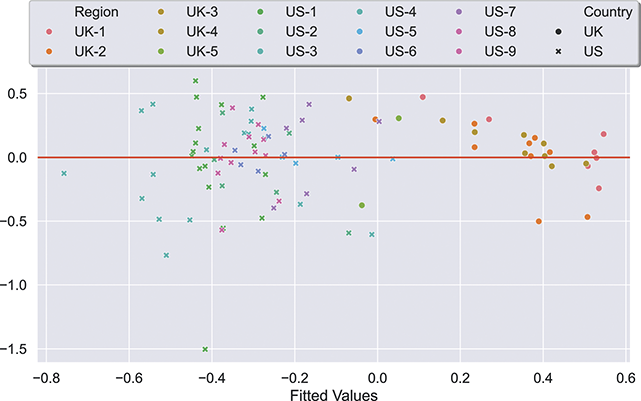

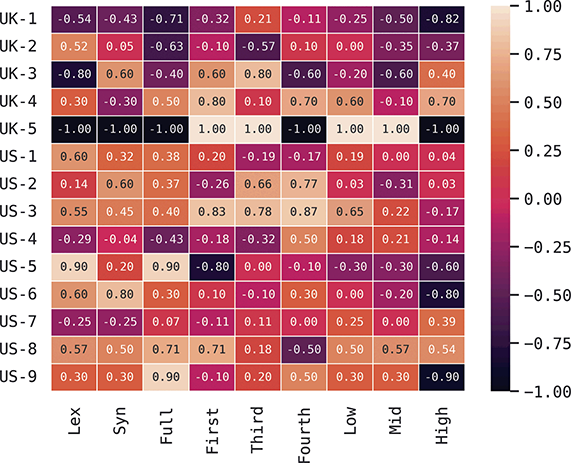

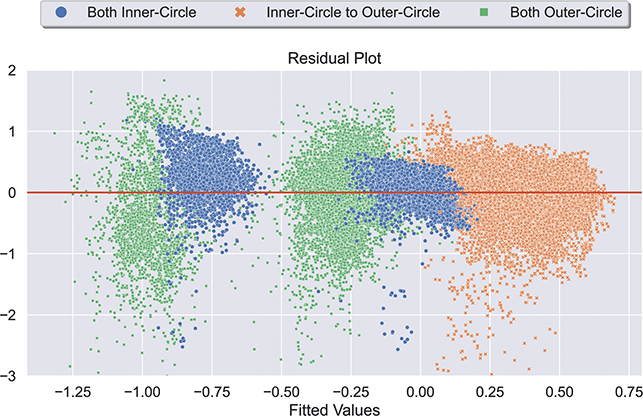

For working with a large set of features, as we are here, a similarity value can become overwhelmed by small differences in very frequent features. Thus, we adopt a pipeline which controls for the absolute frequency of constructions, as shown in Figure 3. First, we start with the token frequencies (usage) of constructions in each sample. These are the basic observable. Second, we standardize frequencies across the entire corpus so that our representation of each sample controls for the expected frequency of each construction. Thus, a very common construction will not have more impact than an uncommon construction because we are focusing on differences from the expected (z-score standardized) frequency. A high value means that a construction is used more in this sample than in most samples and a low value means that a construction is used less often than expected. Third, we take the classifier weights from the Linear SVM used to measure the magnitude of variation to focus the similarity measure on more salient constructions. We take the mean absolute feature weight as an indication of the degree to which each construction is subject to variation; a high weight means that the construction has positive predictive power and a low weight means that the construction has negative predictive power. By taking the absolute value across all classes, we are taking information about the degree to which a construction varies but not about the way in which it varies. This enables the similarity measure to focus on the most salient constructions for modeling variation. Fourth, cosine distance is used to represent the similarity of samples, with high values indicating large differences and small values indicating small differences. Fifth, to make the comparison robust across both locations and nodes within the grammar, we standardize the cosine distances. This provides a rank of all samples from the most similar to the least similar that accounts for the average distance between samples. Thus, a distance of 2.0 would be two standard deviations above the mean distance. This final standardization is helpful for interpreting and comparing distance measures across specific experiments. The end result of this pipeline is a rank, for each experiment, of the most similar samples to the least similar samples.

Figure 3 Pipeline for measuring similarity between conditions, whether based on samples from dialects or registers.

Figure 3Long description

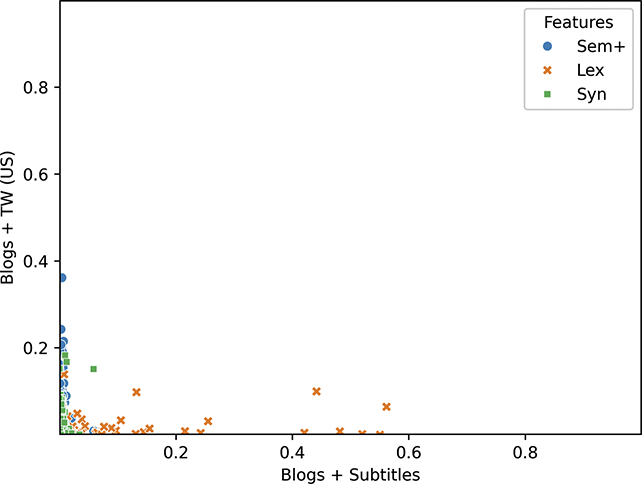

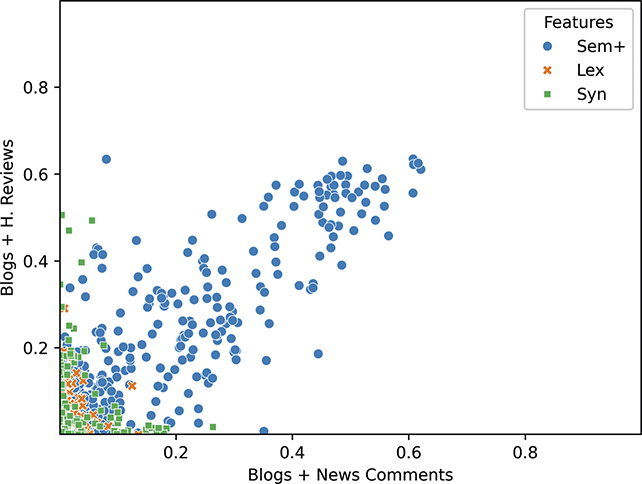

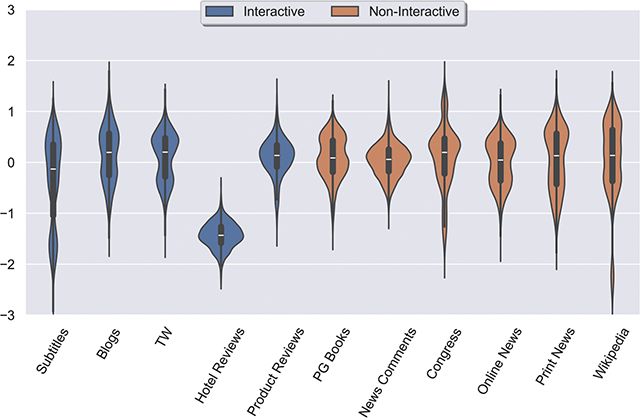

First, feature frequencies are extracted; second, these frequencies are standardized; third, classifier weights are used to focus on specific constructions; fourth, cosine distance is used to measure distance; and fifth, these distances are standardized into rank order.