Introduction

A significant body of research on Southeast Asian politics focuses on the persistence of clientelism (Hicken et al. Reference Hicken, Aspinall and Weiss2019, Reference Hicken, Aspinall, Weiss and Muhtadi2022; Ravanilla et al. Reference Ravanilla, Haim and Hicken2022; Tomas and Ufen Reference Tomas and Ufen2013). Other recent literature on Thailand has focused on new styles of participation and protest that have been evident in the colour-coded conflicts that emerged in the early 2000s (Anurat Phuntungpoom Reference Phuntungpoom2021; Naruemon Thabchumpon Reference Naruemon2016; Suthida Pattanasrivichian Reference Pattanasrivichian2016; Tanet Charoenmuang Reference Charoenmuang, Montesano, Chong and Heng2019) and the subsequent re-emergence of student movements in the late 2010s (Aim Sinpeng Reference Sinpeng2021a; Akanit Horatanakun Reference Horatanakun2023; Kanokrat Lertchoosakul Reference Lertchoosakul2021). These two different approaches to political organisation in Thailand are seldom linked. Little attention has been paid to the broader implications of the erosion of longstanding clientelistic networks on political organisation; yet this very erosion is a primary factor in the emergence of new forms of networks that rely on more egalitarian methods of participation. These new networks have been oppositional and have faced heavy resistance from both the state and entrenched hierarchies that seek to maintain the vertical clientelistic networks of the status quo.

This analysis first looks at the erosion of clientelistic ties and the use of brokers in an attempt to reinforce those ties. It argues that the broker system may be able to slow the erosion of clientelism, but cannot prevent it. It then examines the enabling and motivating factors that have allowed and encouraged the emergence of new styles of networks. Evidence of the development and transformation of network politics can be found in the Red Shirts movements, student movements, and even the clientelistic networks of provincial political families, which have all been significant actors in the transformation of Thai politics over the past two decades. It concludes by looking at the nature of these new networks and their likely effect on Thai politics and society.

Clientelism, Patron-Client Ties and Thai Politics

Research on Southeast Asian politics has long emphasised clientelism, defined by personalised, hierarchical relationships of exchange between patrons and clients (Scott Reference Scott1972a). This literature outlines a pyramidal structure stretching from national politicians to voters that has historically been maintained through face-to-face interaction and the exchange of favours and support (Scott Reference Scott and Neher1979; see Figure 1). Scott (Reference Scott1972b) noted that these personalised relationships had begun to erode as early as the colonial period, due to political, social and economic change. Later scholars accepted this process of erosion was taking place but argued that “brokers” could sustain clientelism by acting as intermediaries who connect politicians to voters, sometimes by reinforcing weak ties with cash or goods (Hicken et al. Reference Hicken, Aspinall, Weiss and Muhtadi2022; Kitschelt and Wilkinson Reference Herbert and Wilkinson2007; Stokes Reference Stokes, Stokes and Boix2007). As Suthikarn Meechan (Reference Meechan2023: 39) concludes, contemporary patron-client networks depend not on strong patron-client bonds but on “the key role that brokers play in closing status disparities.”

Figure 1. Pyramidal Clientelistic Structure with Brokers.

We do not dispute the importance of brokers. Rather, we argue that the broker system is a rearguard action—a temporary correction that may slow but cannot prevent the ongoing erosion of patron-client ties. Indeed, evidence suggests brokers are most effective where dense social ties exist (Ravanilla et al. Reference Ravanilla, Haim and Hicken2022); their utility declines as society modernises, a context in which new types of political organisation have gained importance. Keck and Sikkink, in a study of international activists, noted that networks need not be top-down nor bottom-up; they may be horizontal, agile, fluid, and even behave as if a single actor. Such networks tend to emerge in times of rapid change (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). New technologies are enabling such forms of political organisation, creating networks that compete with broker-mediated pyramids. Such networks can mobilise rapidly and sustain momentum under pressure, as seen in the Arab Spring (Howard and Hussain Reference Howard and Hussain2013), even if they face challenges achieving long-term impact (Tufekci Reference Tufekci2017).

This article applies these insights to Thailand. We argue that the rise of these networks, not just the decline of clientelism, is reshaping the country’s political landscape. They combine top-down, bottom-up, and horizontal ties and thrive in periods of political disruption. It is the emergence of these new networks—not the perpetuation of brokering—that will be the focus of the remainder of this article. We examine the factors enabling their rise and analyse how they are reorienting Thai politics.

Methodology

This article employs a qualitative case study approach to examine the evolution of political networks in Thailand, focusing on three types: political families, which are particularly vulnerable to leadership decapitation; the Red Shirts, notable for their resilience despite internal fragmentation; and student groups, which, while currently dormant, retain latent mobilisation potential. This approach allows for a comparative analysis of how different network models, active during distinct phases of recent Thai political history, have adapted to technological change and to state repression aimed at weakening or eliminating them. Data were collected between 2018 and 2024 through semi-structured interviews and focus groups with participants selected via purposive and snowball sampling techniques. The sample included six categories of actors—national and local politicians, grassroots activists, vote canvassers, student activists, local officials, and academics—chosen for their roles and influence in political activities.Footnote 1 Alongside interviews and focus groups, the study incorporated document analysis of protest materials, junta decrees, and campaign archives.

Analytical procedures drew on process tracking to identify patterns of adaptation in network strategies following the 2014 coup, with particular attention to shifts from analogue to digital forms of organisation. This method was supported by a thematic analysis of the interview transcripts, focus group discussions, and digital content. The study followed established research protocols for interviewing activists under restrictive political conditions (Ajil Reference Ajil2024). Despite these strategies, several limitations remain. The dataset reflects an urban and class bias, as digital activism is more visible in metropolitan areas, while rural and working-class networks often rely on analogue methods and face greater barriers to digital access. This digital divide—a well-documented structuring force in global activism (Norris Reference Norris2001)—means the study’s findings on digital-native networks are most applicable to urban, educated youth, potentially obscuring the strategies of peripheral and less affluent groups. Compared to student activists or Red Shirts members, access to political family elites was more restricted, requiring a greater reliance on secondary and publicly available materials. Moreover, the regional emphasis on northern and northeastern Thailand, while crucial for capturing the Red Shirts’ rural base and the power of provincial dynasties, may not fully account for Bangkok’s distinct sociopolitical dynamics. Lastly, although the sample included female participants, the analysis could more explicitly examine gendered leadership patterns within these networks, an area for future research.

New Network Styles: Rapid Change as an Enabling Factor

The emergence of new forms of networks has been enabled by two primary factors: economic growth and new technologies. For local-level networks, especially in the provinces, decentralisation has also been an important factor, as it shifted resources, responsibilities, and opportunities to the local level.

While Thailand has experienced rapid economic growth since the 1970s, the downturns during the Asian Financial Crisis, the 2008 global recession, and the pandemic may cause us to overlook just how successful Thailand has been. In 1970, per capita gross domestic product was just (current) USD 198. By 1992, it reached (current) USD2,231, a more than tenfold increase. Despite the three downturns, by 2023, per capita gross domestic product had more than tripled again, reaching (current) USD 7,172 (World Bank 2024). This rapid economic growth has enabled the formation of new styles of networks in at least three ways. Firstly, the economic growth led to increased mobility, as jobs opened up in urban areas. As people left their homes behind, they also left their patron-client networks behind. Second, even for those who did not leave their hometowns, economic growth expanded markets. Where once there were few places to buy and sell goods, leaving villagers dependent on a small number of patrons, the expansion of markets opened up new avenues to buy and sell goods, increasing the bargaining power of villagers and reducing their class-based economic dependency on a small patron class. And third, increasing wealth broke patrons’ monopoly on information, a key pillar of their class power, opening up opportunities to gain knowledge and to interact with the wider world in a variety of ways, as rising incomes enabled everything from travel to greater access to new technologies. Decentralisation enhanced these economic trends by extending both economic and political power into local and provincial politics, further expanding local economies and making participation in local politics more valuable and desirable.

Rapid economic growth made available in Thailand a host of new, disruptive technologies that were being developed around the world during the last part of the 20th century and beyond. New technological innovations that arrived in Thailand during this period included cable television (1989), satellite television (1991), and public internet access (1994), first through computers and later through smartphones. Computers, smartphones, and the internet also made available a wide range of applications, from spreadsheets and databases to public and private fora (such as Facebook, Line, and Telegram) to encrypted communications (such as Signal). In addition, the spread of some long-standing technologies has had a significant impact during this period, as access became easier, notably community radio.

As new technologies made their way into local communities, they provided new avenues for politicians to communicate with voters and for interest groups to organise themselves, with each different type of new technology enabling different styles of communication and organisation, and each supporting different types of networks. For example, cable and satellite television allowed the creation of dedicated channels, some of them focused on particular parties and their supporters, such as Pheu Thai’s Voice TV (launched 2009) or Blue Sky for the Democrat party (launched 2011). Yet such television channels were top-down in nature and required large-scale investment. They allowed better dissemination of information without going through the clientelistic broker system, but did little to create networks. The spread of community radio made it easier and cheaper to broadcast information so that knowledge of local issues could more easily be disseminated to those who chose to listen. Community radio also provided a limited degree of public interaction through talk radio. Yet only small, limited networks formed around community radio among the content creators. For the most part, community radio, like cable and satellite television, served primarily to disseminate information rather than create networks of its own.

Internet-oriented technologies and applications provided much more potential for the creation of new types of networks. Not only did Internet-oriented technologies allow dissemination of information through media such as websites, YouTube channels and blogs, but they also allowed interaction between individuals and institutions through, for example, institutional websites and Facebook pages; between any two individuals with internet access through email or apps such as Instagram or WhatsApp; and among groups of like-minded individuals through, for example, internet forums or dedicated Line or Facebook groups. Internet-oriented technologies allowed the creation of relationships that did not even require geographical proximity or familiarity. In this way, they enabled the creation of new types of networks without the hierarchies and face-to-face relationships of patron-client networks.

New Network Styles: Political Disruption as a Motivating Factor

While some political families began to develop new types of networks to supplement their existing broker-reinforced patron-client ties quite early in the expansion of new technologies, these enabling factors were generally insufficient to move them away from the clientelistic networks that had served them so well in the past. Nor did new technologies alone create networks that could challenge clientelistic networks in local or national politics. The political disruption caused by two coups, one in 2006 and the other in 2014, would provide the motivation necessary to create new types of networks to challenge military rule.

The coup in 2006 imposed martial law, abrogated the constitution, and allowed censorship (Chambers Reference Chambers2010: 109) as coup leaders sought to weaken the popular Pheu Thai party (Kingsbury Reference Kingsbury2017: 113). The 2006 coup led to the creation of a new type of network, the Red Shirts network, which formed to oppose the military government. This Red Shirts network is discussed further below. Yet the 2006 coup group chose to hold new elections just a year later, and despite their efforts to remove Pheu Thai, it again won the election. Consequently, in 2014, the military carried out a second coup, this time remaining in power for five years in an extended and more successful attempt to undermine Pheu Thai effectiveness.

In 2014, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha, backed by General Prawit Wongsuwan, carried out a coup, removing a Pheu Thai government from power. The generals established a military regime, dubbed the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO). The junta made proclamations instituting martial law and imposed sweeping restrictions on the media, internet, and political rallies. Some members of the cabinet were prosecuted, including those in control of public activities and the media. Activists and webmasters were arrested, and political activities and academic forums criticising the government were banned (Naruemon Thabchumpon Reference Naruemon2016; Saksith Saiyasombut Reference Saiyasombut2015; Suthikarn Meechan Reference Meechan2023). The NCPO then sought to impose its perspective on all opposition, employing attitude readjustment camps for those who proved recalcitrant (Elinoff Reference Elinoff2021:5; Ockey Reference Ockey, Ratuva, Compel and Aguilar2019). This repression would later inspire the re-emergence of the student movement, employing a new style of network, discussed further below.

The junta also sought to pressure powerful provincial politicians linked to Pheu Thai to join its own political party. Among those facing pressure was Bunloet Buranupakorn, who was suspended and charged for distributing leaflets opposing the new military-backed constitution.Footnote 2 Under such pressure, Bunloet stepped away from politics. Other provincial politicians moved to one of the pro-military parties. Still others cautiously continued to support Pheu Thai. Junta-exerted coercion and pressure proved a powerful motivating force for moving opposition away from public activities to more secure, private digital platforms such as Telegram, Line, and closed Facebook groups. Where economic growth, technological development, and decentralisation enabled new forms of political networks, it was political disruption that motivated more extensive shifts to new forms of networks.

Family Networks: Patronage and the Digital Realm

Thai political families (Ban Yai) have historically entrenched their power through broker-mediated patronage networks, using local intermediaries to distribute resources, secure votes, and maintain influence. This enduring dominance is exemplified by dynasties such as the Thepsuthin clan in Sukhothai and the Promphat family in Phetchabun, which have maintained control in Thailand’s Lower North since the mid-20th century (Chambers and Watcharapol Supajakwattana Reference Chambers and Supajakwattana2025). The resilience of many such families contrasts sharply with the more transient influence of movement-based networks, including the Red Shirts and student activists, underscoring the adaptability to state repression of many familial patronage systems in Thai politics.

However, the 2014 military coup exposed the fragility of these traditional structures when faced with state repression. The case of Bunloet Buranupakorn—the Pheu Thai-aligned patriarch of Chiang Mai’s most powerful political family—illustrates this tension as set out below (Chambers et al. Reference Chambers, Jitpiromsri and Takahashi2023; Ockey Reference Ockey2017). Prior to his eventual arrest in 2016 for opposing the junta’s draft constitution, Bunloet’s success was built on hybrid campaign techniques that merged traditional patronage with data-driven digital campaigning. His arrest marked a turning point—demonstrating that even well-entrenched, highly successful political families could collapse if they directly challenged military authority. In contrast, families like the Jureemas of Roi-Et chose strategic alignment with the junta, ensuring survival at the cost of political autonomy. Nishizaki (Reference Nishizaki2022) and Suthikarn Meechan (Reference Meechan2023) argued that the junta’s carrot-and-stick approach, which combines reward and punishment, split political families into collaborators and resisters —a useful, if somewhat oversimplified, framework.Footnote 3 This same divide is reflected in their technological adoption rates.

The different approaches and results between the Buranupakorn and Jureemas families highlight a key dynamic in post-coup Thailand: political families must now carefully navigate between resistance and accommodation, with technology playing an increasingly central role in their strategies. For political survival, this need to adapt to technology is even more salient in highly developed provinces, such as Chiang Mai, where a large student population and a burgeoning middle class create both the demand for and the capacity to use sophisticated digital political tools.

Technology as a Patronage Supplement

The Buranupakorn family’s Khunnatham [morality] network offers a compelling case study in how Thailand’s political families are adapting to the digital age while maintaining traditional power structures. Their innovative approach combines database politics with conventional patronage systems, creating a hybrid model of political influence. By compiling a private database of Khunnatham supporters—comprising some 5% of Chiang Mai’s registered voters—the family gained the ability to communicate directly with constituents via personalised text messages. This effectively circumvented the traditional pyramid of political brokers, creating a direct channel to the grassroots. Yet the broker system remained, as it strengthened relationships through personal ties, even as the direct connection between leadership and grassroots created new, different types of loyalty. This technological adaptation allowed for more efficient voter engagement while preserving the crucial element of personal connection that underpins Thai patronage systems.

The family’s strategy demonstrates a sophisticated blending of old and new methodologies. As Chief of the Provincial Administrative Organisation (PAO), Bunloet Buranupakorn maintained the symbolic importance of face-to-face patronage by personally approving local development projects, even as his political apparatus increasingly employed data analytics to identify and target swing voters. This dual approach, which merges global digital campaign techniques with locally grounded political traditions, represents a significant evolution in how Thai political families maintain and exercise power after the 2014 coup, particularly in adapting international digital populism strategies to Thailand’s unique rural political context.

Social media has also provided a crucial platform for revealing the diversity present within notable political families, including the Buranupakorn clan. Thassanee Buranupakorn, a former MP of the Pheu Thai party, made a public announcement regarding her resignation from the party in 2023. This decision followed Pheu Thai’s contentious choice to establish a coalition government that incorporated pro-junta parties, namely the Phalang Pracharath Party (PPRP) and the United Thai Nation Party (UTNP). Facing a restricted political environment and potentially leveraging the distinct communication strategies available to women in a patriarchal system, Thassanee used Facebook and various social media platforms to publicly declare her resignation, showcase her ongoing political initiatives, and engage in discussions on a broader range of political topics. This act not only exposed a rift within a powerful clan but also demonstrated how digital tools enable new forms of political expression and personal branding when traditional channels are suppressed.

The Jureemas family exemplifies how traditional political families have adapted to modern challenges while preserving their core patronage networks. Their longstanding dominance in provincial politics dates back to the 1960s, with family members consistently securing influential positions, such as Anurak Jureemas, who has been a member of Parliament for nine terms and a cabinet minister in several coalition governments. Other family members, most notably Bunjong Kosajiranund, have secured lasting local power, serving over two decades as mayor of Roi-Et city, despite national political shifts. The families’ enduring influence is reinforced through tightly woven broker-reinforced patron-client networks, which include alliances with municipal officials, community leaders, and business owners, allowing them to maintain control over local resources and policy implementation. Strategically, the family has aligned itself with the Yellow Shirts movement and royalist factions, positioning itself as a key ally for the military junta (Suthikarn Meechan Reference Meechan2023) —a move that distinguishes them from other political families like the Red Shirts-aligned Buranupakorn.

While traditional patronage remains central to their power structure, the Jureemas family, including their local team “Pitak Thongthin” [safeguard local interests], has supplemented its strategy by cautiously adopting modern digital tools. Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok have been incorporated to broaden voter outreach, particularly during national elections. For instance, during the 2019 and 2023 elections, Anurak’s social media team effectively engaged voters and younger generations online, though these efforts remained secondary to their well-established offline networks (Suthikarn Meechan Reference Meechan2024). Through this hybrid approach, the Jureemas family continues to adapt to Thailand’s changing political landscape while sustaining their influence.

The Buranupakorn and Jureemas families’ use of Facebook and TikTok to modernise their appeals while maintaining traditional power structures is not unique to Thailand. This mirrors a broader regional trend of political dynasties adapting to the digital age. In the Philippines, the Marcos family famously leveraged TikTok and other platforms to execute a sophisticated rebranding campaign, targeting youth voters and successfully rehabilitating their image to return to power (De Guzman Reference De Guzman2022). This suggests that digital tools are often used not to dismantle patronage politics, but to make it more palatable and resilient in the 21st century.

The divergent strategies of the Buranupakorn and Jureemas families—rapid innovation versus cautious hybridity—underscore how Thailand’s political families balance technological adaptation with kinship-based authority. While the success of the Buranupakorn local “Khunnatham” team’s database experiment led to local dominance and subsequently emboldened their resistance, triggering junta backlash, the Jureemas clan’s incremental approach for modern and youth-targeted online campaigns extended their rural patronage networks in more limited ways, posing little threat to the junta—the family then supported the coup regime. This Jureemas approach underscores the ability to preserve traditional power through the use of technology.Footnote 4

As illustrated in Figure 2, political families embody a modernised form of traditional organisation—upholding rigid hierarchies while cautiously embracing digital tools. These networks function through pyramid structures, with authority concentrated in family patriarchs, cascading down through trusted intermediaries (brokers, administrators, and analysts) who oversee relationships, data, and campaign logistics. Although they utilise social media and online campaigns, technology primarily serves to amplify, rather than transform, their analogue power structures, resulting in a system where digital efficiency bolsters traditional patronage.

Figure 2. Modernised Pyramid of Adapted Familial Networks.

This model excels in message control and resource discipline, but it compromises the adaptability characteristic of decentralised movements. These political families’ resilience stems from their ability to improve their digital outreach without upsetting their core hierarchies, a strategic manoeuvre that demonstrates their understanding of the demands of contemporary politics. Nevertheless, their commitment to top-down control ultimately constrains their ability to evolve in line with the more fluid, network-based political engagement seen in the cases that follow below.

In summary, these political families strategically leverage technology to reinforce—not replace—their patronage systems. Their approach demonstrates a sophisticated adaptation to technological change while highlighting the inherent limitations associated with efforts to modernise fundamentally rigid power structures. Adaptation proceeded much more rapidly and robustly in Chiang Mai, with its larger middle classes and its multitude of university students, underscoring how class and educational capital shape the efficacy of digital political strategies. The outcome is a potent yet potentially fragile hybrid, particularly in Chiang Mai, where digital tools have maintained traditional authority rather than democratised it.

The Red Shirts: Adaptive Resistance Networks

The Thai political landscape of the mid-2000s was marked by the rise of two opposing alliances. The Yellow Shirts (People’s Alliance for Democracy, PAD) and the Red Shirts. These movements emerged from distinct socio-political contexts and employed contrasting strategies to advance their goals. The Yellow Shirts appeared in 2005 as a movement against Thaksin Shinawatra. It was based on royalist, nationalist, and urban middle-class values (Aim Sinpeng Reference Sinpeng2021b; Suthida Pattanasrivichian Reference Pattanasrivichian2016). Led by figures such as media tycoon Sondhi Limthongkul and conservative elites, the movement drew support from the monarchy, military, and judiciary (Jory Reference Jory2014: 3; Kanokrat Lertchoosakul Reference Lertchoosakul2018: 46; Pavin Chachavalpongpun Reference Chachavalpongpun2013: 7).

The Red Shirts movement emerged as a direct response to a specific critical juncture: the 2006 military coup that removed Thaksin Shinawatra from power. From its inception, the movement’s strength lay in its hybrid structure, which combined traditional clientelistic networks with modern communication technologies. Its peak influence around 2010 was a direct result of this political disruption. The Red Shirts were comprised of rural grassroots supporters, pro-democracy activists, and local politicians linked to Thaksin’s parties. While the Yellow Shirts represented urban middle classes and elites, the Red Shirts championed the socio-economic grievances of the rural and urban working classes. While these two movements were made up of diverse interests, fundamentally they represented a clash between royalist conservatism, promoted by the elite and the more established urban middle classes, and the democratic and economic aspirations of the lower classes.

In terms of mobilisation strategies, the Yellow Shirts used various media platforms, such as the ASTV satellite television channel, The Nation and Manager newspapers, and Voice of Dharma radio shows, to disseminate their anti-Thaksin campaigns and rhetoric. Elite networks and large urban rallies in Bangkok further solidified their power by effectively inflaming anti-Thaksin sentiment. This influence was particularly evident when the military seized power in the 2006 coup, following the constitutional court’s disbanding of Thaksin’s Thai Rak Thai Party in 2006 and subsequently the People’s Power Party in 2008. (Group discussions 2018a).

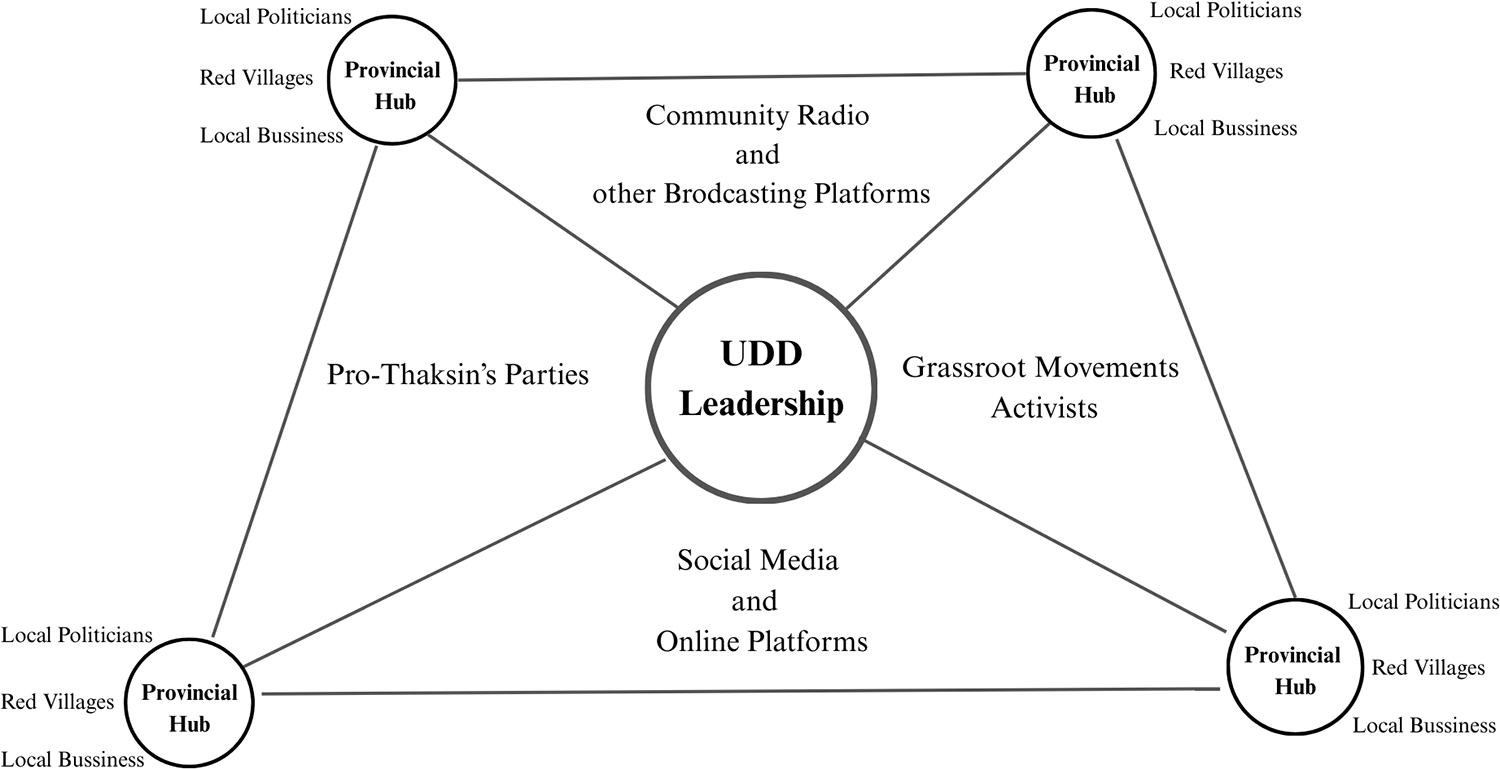

In stark contrast, the Red Shirts developed an innovative hybrid organisation that combined hierarchical leadership with decentralised grassroots networks. At its core was the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD), which provided centralised direction through national leaders connected to Thaksin’s political machine. (Anonymous interview 2018b). However, the Red Shirts movement’s true strength came from its “Red Villages for Democracy” (Naruemon Thabchumpon Reference Naruemon2016), community-based groups that maintained autonomy while coordinating through local radio stations and face-to-face networks. Community radio has been more than just a platform for communication; it has also been a platform for creating content free from the monopoly of the major Bangkok-based, state-owned, and elite-owned radio stations, thus escaping the traditional censorship framework. In fact, community radio empowers the locals, as those who become reporters or news anchors are close to the community members who are their friends or neighbours (Anonymous interview 2019e). Community radio stations thus play a vital role in the Red Shirts network as an intermediary hub for both mobilisation and for informing local communities of Red Shirts viewpoints on national issues and sociopolitical development (Kajonsak Sithi Reference Sithi2015). With the Red Shirts’ leaders facing a multitude of state attacks, their networks experienced a gradual decline following the military coup in 2014, under the junta’s mechanisms of control.

In response to governmental oppression, the Red Shirts employed various strategies to sustain their movements. To convey their message to supporters while evading government censorship, they utilised media platforms, such as local cable television in provinces, satellite TV, YouTube, and Facebook, to livestream rallies, promote and sell merchandise, and solicit financial support. The “1110 model” of mobilisation, employing local level brokers, was a notable practice wherein groups organised protests by enlisting 10 participants from each village, all transported by a single bus. This method enabled the organisation of local coordination for large-scale demonstrations (Yanyong Pivpong and Supawatanakorn Wongthanavasu Reference Pivpong and Wongthanavasu2015: 224). Perhaps most significantly, they transformed traditional rural clientelistic networks into horizontal solidarity movements, functioning alongside vertical ties, while converting personal loyalty to Thaksin into collective political consciousness.

The Yellow Shirts also expanded their influence through digital media, using Facebook and online platforms to coordinate protests and share royalist content. Despite these modern tools, they maintained a strong top-down structure, relying on elite alliances and institutional backing. Their protests were centrally coordinated, led by a group of prominent figures and anti-Thaksin movements under the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), which expanded the movement’s reach through urban rallies and media campaigns to coordinate protests and share royalist content. Although there were Yellow Shirt supporters in provinces, they were mostly centralised in urban areas (Suthikarn Meechan Reference Meechan2023: 153-156). This urban, elite-aligned core was visibly distinct, its symbolic unity reinforced through consistent branding, most notably the iconic yellow shirts and wristbands.

In contrast, the Red Shirts employed a hybrid structural organisation model. The United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD) established a formal hierarchy comprising national leaders and provincial coordinators, including other pro-democracy grassroots movements and activists who linked with the UDD and acted independently. The Red Shirts can thus be seen as part of Thai Rak Thai and its successor parties since the major parts of the network are led by politicians (Suthikarn Meechan Reference Meechan2023: 162-164). Yet local entities such as “Redshirt Villages for Democracy” also maintained a degree of grassroots autonomy. This dual structure allowed the movement to function as both a cohesive political entity supporting Thaksin-aligned parties and a decentralised protest network.

This decentralisation was facilitated by a robust media ecosystem. Local newspapers, cable television, community radio programmes, and social media utilised by the Red Shirts network facilitated the dissemination of shared values and promoted cooperation. Both traditional and modern methods facilitated local leaders and activists in independently mobilising support, thereby ensuring resilience against state crackdowns.Footnote 5 However, various forms of local media faced closure, leading to extensive self-censorship (Anonymous interview 2019c, 2019d). Thus, the Red Shirts combined traditional clientelistic networks with modern communication technologies. They transformed from largely vertical loyalties into many horizontal connections, particularly in Thailand’s Northeast, linking villages across regions. While the use of community radio to coordinate makes the Red Shirts’ networks somewhat unique in the region, hub and spoke style networks have been used by other decentralised activist networks, such as development-oriented NGOs in the Philippines, with varying degrees of central coordination (Constantino-David Reference Constantino-David, Edwards and Hulme1992).

The 2014 Coup Impact: Fractured Hierarchies and Persistent Networks

The 2014 military coup severely weakened the Red Shirts’ organisational framework by purposefully dismantling their national leadership and directly targeting their grassroots networks. The junta used various strategies to suppress the movement. Politically, Thaksin’s parties, the People’s Power Party and its successor, the Pheu Thai Party, which served as the movement’s political arm, were weakened by military interventions and a lack of representation in Parliament, resulting in severed connections between local and national leaders. Simultaneously, on the organisational front, key allies of the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD) were arrested or forced into exile, and their alliances were disbanded. Legally and through media control, martial law prohibited public gatherings, and the government shut down Red TV channels and community radio stations, both of which played critical roles in mobilising supporters in rural areas to come out to protests. This effectively destroyed the movement’s formal infrastructure.

Collectively, these measures fundamentally transformed the organisational architecture of the Red Shirts. Prior to the 2014 coup, the network functioned efficiently as a hub-and-spoke system, with the UDD leadership serving as the central hub that coordinated provincial spokes, including local politicians, Red Villages, and community radio stations. However, the repression following the coup shattered this hierarchy. The outcome was akin to a fractured wheel: while individual segments, or local nodes, maintained their structure, they began to operate semi-independently. Consequently, they were forced to rely on horizontal trust networks and digital workarounds when vertical channels were cut off.

The Red Shirts’ resilience, based on strategic adaptation, is rooted in several key factors. First, local leaders demonstrated their capacity to maintain their influence by actively participating in local councils, business initiatives, and bureaucratic networks. This embeddedness secured their ongoing political status under the junta. Furthermore, following the 2014 coup, national and local elections were not allowed for five years or more, so that these local executives and councillors remained embedded in their roles for extended periods without electoral competition.

Secondly, due to governmental repression, the Red Shirts’ mass mobilisation and political activities encountered obstacles; however, clientelistic relationships in Thailand’s rural Northeast, the network’s core region, persisted. This enabled many supporters of the movement to sustain their loyal voter base, as demonstrated by the general election outcomes for the Pheu Thai electorate. The Red Shirts supporters expanded political support to include the opposition Future Forward Party in 2019 and its successor, the Move Forward Party, in 2023 (Suthikarn Meechan Reference Meechan2024).

Finally, the Red Shirts facilitated the persistence of grassroots groups, despite the collapse of the group’s national coordination and formal structures (Anonymous interview 2018a, 2019a, 2019b). Consequently, grassroots activists sustain informal networks within their villages, whereas radical dissidents engage in underground resistance efforts. However, the organisational structure, a hybrid of top-down leadership (UDD) and grassroots independent groups, contributed to both their strength in centrally coordinated mobilisation and their potential challenges in maintaining cohesive action across diverse factions. Furthermore, their ability to tap into both long-standing social connections and novel forms of mobilisation underscores their deep roots within Thai society and their capacity to adapt to modern methods of outreach.

While the movement never fully regained its pre-2014 strength, its hybrid model of organisation—hierarchical yet also decentralised and horizontal—became a partial blueprint for Thailand’s newer pro-democracy movements. Youth-led protests, for instance, adopted the effective strategies of the Red Shirts, including mass mobilisation and organised protest management, while rejecting their Thaksin-aligned leadership.Footnote 6 Local Red Shirts networks continue to demonstrate substantial mobilisation capacity, reflecting strong support and a cohesive collective voice. This capability highlights an important change in Thai politics: while authoritarian regimes may dismantle hierarchical structures, decentralised, socially embedded networks demonstrate a much greater resilience. The legacy of the Red Shirts persists, despite a marked decline in influence, as an instructive example of adaptation to repression, wherein formal hierarchies confer electoral influence and informal networks facilitate survival. The Red Shirts experience indicates that movements can endure state repression when founded on political parties, local political offices, and robust grassroots connections.

The post-coup Red Shirts movement thus operates as a sophisticated hybrid political model, blending traditional organisational structures with modern digital mobilisation strategies. At its core, following the 2014 coup, lies a distinctive “fractured wheel” structure that combines limited centralised coordination through UDD leadership and pro-Thaksin parties with semi-autonomous provincial networks. These local networks, represented by circles in Figure 3, function largely independently and comprise local politicians, rural communities, and businesses. This dual structure enables both limited top-down strategic direction and grassroots flexibility, allowing the movement to maintain cohesion while adapting to local conditions. The Red Shirts’ strength stems from their multi-layered communication system, which integrates traditional platforms like community radio and face-to-face networks—which sustain crucial local trust relationships—with digital tools, including social media and messaging apps, that enable rapid regional coordination.

Figure 3. Hybrid Red Shirts Movement as a Fractured Wheel (Post-Coup).

This hybrid approach grants the movement remarkable resilience: its decentralised nature preserves functionality during central leadership crises, while horizontal connections between provincial nodes permit localised responses without sacrificing broader movement unity. However, this complex system also generates inherent tensions, particularly in balancing institutional discipline with grassroots spontaneity and in managing uneven technological adoption across different regions. When compared to other networks, the Red Shirts’ model demonstrates distinct advantages – it maintains greater organisational stability than student activists’ purely digital approaches while showing more adaptability than political families’ rigid hierarchies. Ultimately, the Red Shirts’ success lies in their strategic synthesis of analogue trust networks with digital scalability, offering a replicable template for political mobilisation that harnesses technological innovation without abandoning tried-and-tested organisational foundations in the face of authoritarian pressure.

Students: Leaderless Networks and Digital Dissent

After the 2014 coup, Thailand experienced a resurgence of youth-led resistance, marked by a transition from institutionalised, official umbrella organisations for university students to a new wave of youth-led movements. The contemporary student movement, which reached its zenith by 2020, was motivated by a series of events: the extended period of authoritarian governance that followed the 2014 coup, the widespread perception of the resulting political order as illegitimate, and more proximately, the machinations of the coup regime following the 2019 election. This resistance movement operated via decentralised, digitally native networks, replacing earlier hierarchical student organisations. This shift signifies more than just a tactical adjustment; it reflects a fundamental reimagining of political engagement in the digital age, drawing on links with the Red Shirts and comprising a part of the broader dissent landscape in Southeast Asia.

From Hierarchies to Hashtags

The transformation of Thailand’s student activism from the 1970s to the 2020s reveals a profound shift in organisational strategies and resistance tactics that mirror broader technological and political changes in society. The leading role of the National Student Centre of Thailand (NSCT) exemplified the student movements of the 1970s.Footnote 7 Their efforts were organised according to the distinct hierarchies established across university campuses. Hierarchically-organised student associations engineered large-scale protests, such as the pivotal uprising in 1973; their visibility regarding personnel and institutions rendered them vulnerable to state repression. The 1976 Thammasat Massacre demonstrated this vulnerability starkly, as authorities targeted identifiable leaders and campus gathering points to dismantle the movement. Despite their hierarchical organisation, in some ways, the student movements of the 1970s also rejected institutionalised hierarchy, such as that between generations of students in the form of the SOTUS system (Thongchai Winichakul Reference Winichakul2015: 5).Footnote 8 They adopted the communist appellation “sahai” (comrade) among themselves, which sought to reshape social hierarchies (Bolotta Reference Bolotta2024). But they continued to rely on hierarchical institutional structures for centralised leadership.

The consequences of political and digital disruption, including the 2014 coup and the COVID-19 pandemic, indirectly reshaped Thailand’s modern student movements. The student activism that emerged following the 2014 coup differs markedly from earlier forms, incorporating lessons learnt from the Red Shirts. This most recent student movement has adopted a decentralised, digitally native model, effectively leveraging new technologies while navigating the challenges posed by increased state surveillance. Facilitating secure communication among individuals involves maintaining and managing communication between and among members of networks utilising encrypted messaging applications, such as Telegram and Signal.

The use of encrypted channels like Telegram and Signal is a necessary adaptation to state surveillance, though Thailand’s digital environment remains relatively more open than in countries like Vietnam, where Decree No. 147/2024 has made anonymity nearly impossible and forced dissent almost entirely into obscured online discourses (Thiện Reference Thiện2024). This relative openness in Thailand has allowed for the resurgence of large-scale offline protests, a tactic far riskier in Vietnam’s more restrictive context.

Modern youth activist groups, along with smaller allied groups, have emerged autonomously on digital platforms and university campuses, operating independently of formal university unions and student councils. Examples include Free Youth and the United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration. The groups have increased the scale of protests and introduced innovative strategies to confront the junta-backed government while also addressing fundamental issues in Thai sociopolitics, particularly inequality and non-democratic frameworks.

The new youth movements—comprising university and high school students and older generations as allies—employ viral symbols like the three-finger salute from the Hunger Games, cartoon characters, and white ribbons to encourage solidarity (Kanokrat Lertchoosakul Reference Lertchoosakul2021; Wichuta Teeratanabodee Reference Teeratanabodee2023). The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated digital adaptations and global youth movements by enabling and motivating new frameworks for online mobilisation and decentralised resistance. Health practices and legal restrictions, including the transition to online classes for students in universities and schools, led to the suspension of physical mobilisation (Anonymous interview 2024b; group discussion 2024a). The reduction in mass demonstrations was accompanied by a corresponding rise in participation on digital platforms.

The operational differences between 1970s activism and early 2020s youth-led movements are significant. During the 1970s, face-to-face meetings were crucial for activists. Although modern student movements work in more decentralised ways with fewer face-to-face interactions due to technological advancements and increased accessibility, in-person meetings among group leaders and members remain essential for building movement partnerships and expanding networks of friendship (Anonymous interview 2024c, 2024f; Group discussion 2024b, 2024c), and are no longer limited to Bangkok and major provincial universities but also extend to other institutions and schools in the provinces (Thai Lawyers for Human Rights 2021).

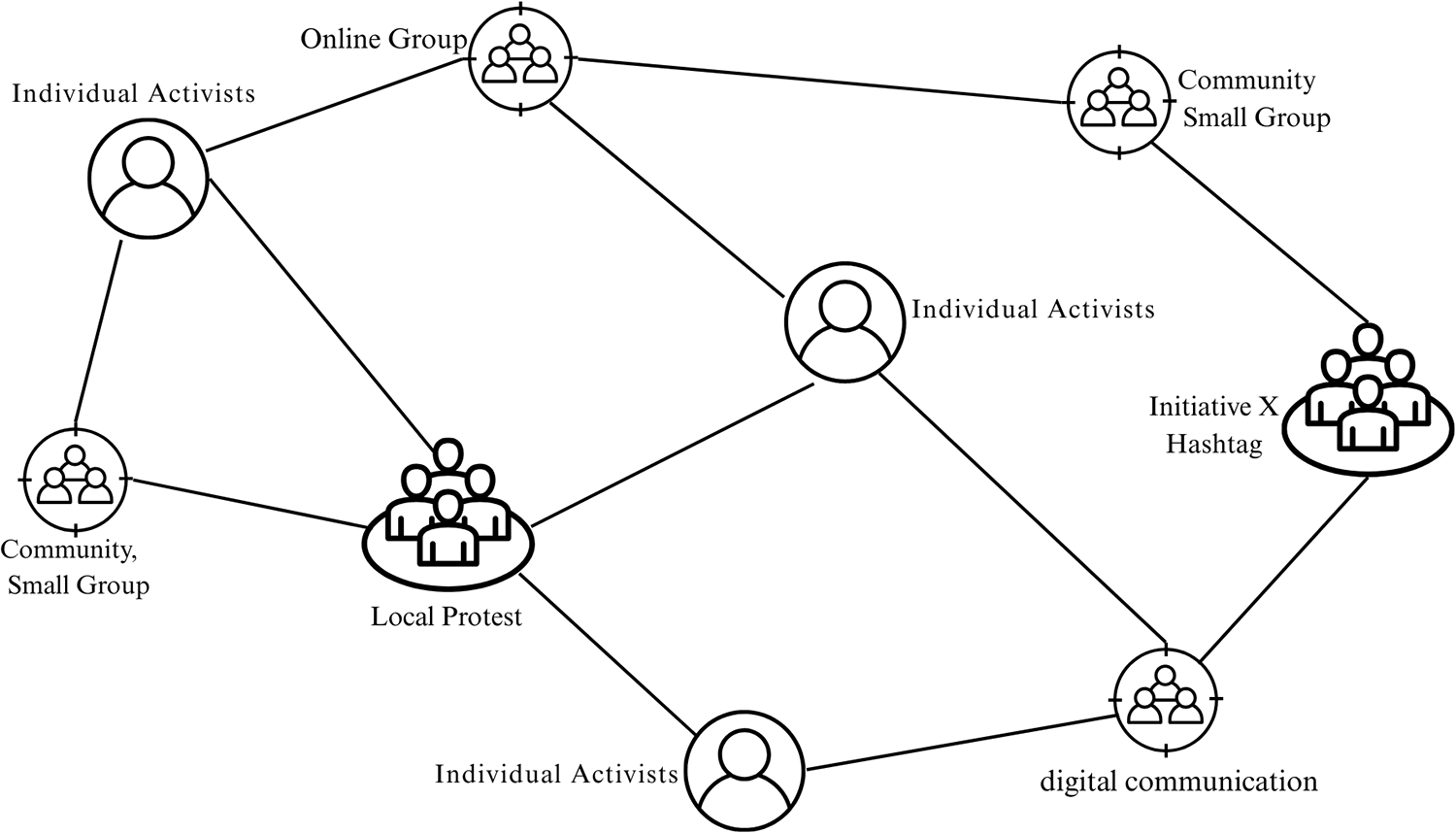

Additionally, some youth-led movements align with other movements or key supporters with whom they can connect on media or online platformsFootnote 9, including Red Shirts activists and certain political parties they support. These student networks function with limited vertical supervision and generally comprise individuals who engage exclusively through digital personas. A multitude of individuals have not met in person and are oblivious to each other’s true identities (Group discussion 2024a, 2024b). These movements are distinctly compartmentalised, with substantial protests arising from informal coalitions of small, independent groups.

The protests of 2020–2021 demonstrate that small groups can collaborate in networked protests while retaining their autonomy. This approach enhances legitimacy, engages a broader public, and complicates governmental repression of dissent by connecting diverse social and political causes. Youth collectives prioritise self-organised agendas and identities by structuring themselves around functional roles rather than formal leadership positions. In contrast to earlier generations with clearly defined leaders, today’s activists mobilise university and high school students, citizens across the country, and diaspora communities—while mitigating risks through decentralised, platform-dependent strategies. This model not only widens participation but also complicates state efforts to dismantle dissent through traditional intimidation tactics.Footnote 10

From Smartphones to Street Protests: The Tech-Driven Networks

Digital tools have evolved into essential components for contemporary student activists in Thailand, serving as the foundation for resistance efforts. These movements draw inspiration from and parallel other youth movements, such as the Milk Tea Alliance, which emerged in 2020 to unite netizens and activists across Asia in opposition to authoritarianism and in support of democratic values. Unlike familial networks, which incorporate technology as a supplement to existing structures, today’s youth-led movements have built their organisational models around digital platforms. Since the Bloody May events of 1992, in which students, supported by urban middle and lower classes, played a significant role in challenging the military’s actions (Anonymous Interview 2024e; McCargo Reference McCargo2002: 40), employing tools such as mobile phones, pagers, and radios to inform and mobilise protesters, the evolution of youth-led political mobilisation in Thailand now operates through three primary mechanisms. Firstly, coordination has evolved through applications and online platforms to mobilise, evade censorship, and organise protests. For instance, encrypted channels like Telegram and Signal facilitate the organisation of flash protests, while social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter (X)Footnote 11, Instagram, and TikTok, as well as live streaming on Clubhouse and YouTube Live, help maintain momentum. Use of such tools also facilitates outreach to previously inaccessible groups, particularly in remote provinces.

Secondly, financial support has gone beyond regular donations. Beyond simply raising awareness, activists sustain the momentum of their movements by selling protest-themed merchandise—such as clothing, stickers, and artwork—and using crowdfunding to finance legal aid, medical supplies, and logistical support.Footnote 12 Lastly, they engage in information warfare through anonymous Twitter/X accounts, spreading dissent while eluding state surveillance. This digital-native approach shows both regional parallels and unique Thai characteristics. The movement’s base, predominantly drawn from educated urbanites, has developed a distinctive protest culture that blends online coordination with performative street theatre and pop culture—such as the Harry Potter and Hamtaro themed protests (Noppatjak Attanon Reference Noppatjak2020). This creative synthesis of digital and physical resistance tactics sets Thailand’s movement apart from other student movements.

However, this decentralised model presents inherent structural challenges that impact the movement’s cohesion and longevity. Without a central organisation, things become fragmented; for instance, the groups “Bad Student” (Tuwanont Phattharathanasut Reference Phattharathanasut2024), which advocates for education reform and youth rights; “Free Youth,” which calls for reforms in Thailand’s democracy and monarchy; “Thalu Wang,” which seeks to challenge royal institutions; and “Thalu Gas” operate as independent mobs, arriving with large firecrackers and slingshots to confront the crowd control police (Anusorn Unno Reference Unno2021:6). Thus, while these youth movements share common goals, they occasionally pursue different objectives and methods of activism.

Thailand’s student movements have persisted in their activism despite various challenges, leveraging digital networks as a manifestation of a broader transformation in modern activism. Their strategic engagement with the digital realm to contest established norms and institutions in pursuit of democracy is facilitated by communication and organisation via online platforms and social media, contrasting significantly with earlier methods. This structure is characterised by decentralisation and flexibility and features predominantly horizontal forms of organisation. It encompasses various groups and individuals, distinguishing itself from conventional clientelistic networks. Thai student networks deviate from patronage politics: brokers are absent, while hashtags and horizontal alliances assume central importance. The absence of rigid hierarchies renders these movements more difficult for authorities to dismantle, offering lessons that inspire activists across Southeast Asia. Digital tools enable a single tweet to become an instant rallying call and foster a more inclusive form of engagement.

Thai students insist that their movement is leaderless (although some acknowledge that leadership still exists in practice) (Anonymous interview 2024c, 2024d, 2024f), as any student can initiate a hashtag, create a meme, or even call for action. Many students participate as individuals joining activities initiated by others. However, many other students participate as part of a formal group, such as a university club, or as part of an informal group of friends and acquaintances, sometimes growing out of the protests themselves. Such groups do have leaders. The movement’s vulnerability stems from its reliance on such de facto leaders, including Parit “Penguin” ChiwarakFootnote 13 and Panusaya “Rung” Sithijirawattanakul, and leaders of the United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration, who face multiple criminal charges (Bangkok Post 2021). Their arrests can unite supporters but also starkly underscore the lack of formal mechanisms of coordination, a vulnerability of leaderless movements. Legal persecution and numerous arrests have systematically diminished the number of such leaders within the movement (Anonymous interview 2024d, 2024h; Janjira Sombatpoonsiri et al. Reference Sombatpoonsiri, Williams and Ruijgrok2025; Group discussion 2024c).

The decentralised model employed by the student movement presents inherent structural challenges. Leaderless networks often face difficulties in decision-making and coordination, and the absence of clear leadership can lead to confusion and inefficiency, making negotiation within the movement and with the state difficult. While these leaderless networks excel at evasion and rapid mobilisation, their struggles with sustainability and achieving concrete policy change are a common weakness. This approach contrasts with the 2019 Indonesian student movement (#ReformasiDikorupsi), which, while also propelled by digital media, leveraged more formal student union structures and established alliances. These characteristics allowed them to extract significant concessions from the government (Sastramidjaja Reference Sastramidjaja2020). Similarly, the Bangladesh student movement adopted a hub-and-spoke-style network, with students forming committees at each university, with the central hub consisting of leaders from Dhaka-based universities (Zainuddin et al. Reference Zainuddin, Islam and Arif2025: 2-3).

The Thai student movement’s horizontal model, while a strength for security, may impose limitations on bargaining power and on long-term political impact. It is also vulnerable when the state limits access to the internet; indeed, the Indonesian and Bangladesh models are likely to become more common as states selectively limit internet access to control protest movements, as we saw in Bangladesh (Zainuddin et al. Reference Zainuddin, Islam and Arif2025: 5). The weaknesses of decentralised leadership are also apparent when contrasted with the student uprisings in Thailand during the 1970s and the prominent roles of students in the 1990s, when established student unions played a significant part in organising efforts. In the 2020s, the pattern of resistance appears fragmented and lacks a central leader capable of uniting the various allied movements into a cohesive political network (Anonymous interview 2024e, 2024g).

Figure 4 depicts a “leaderless mesh” model of student networks that is digitally native and highly decentralised, relying on fluid, issue-based mobilisation and peer-to-peer communication. This structure exemplifies the nature of contemporary activism, in which small community groups and individual activists function as foundational units. Through digital communication tools, such as social media hashtags and online platforms, loosely connected actors can quickly organise local protests or launch initiatives without relying on central leadership. The structure prioritises adaptability and flexibility, enabling the organic emergence of ideas and movements while leveraging technology to enhance their impact and reach. In contrast to hierarchical organisations, this model is characterised by networked collaboration, which enables each participant—whether an individual activist or a small group—to contribute to and influence collective action without the need for strict, top-down control. This approach enhances the movement’s resistance to suppression; however, such movements may encounter difficulties maintaining coordination or expanding beyond localised initiatives.

Figure 4. The Leaderless Mesh of Decentralised Student Networks.

Comparative Analysis of Thai Political Networks

Thai political networks over the past two decades can be effectively analysed through three distinctive models, each representing an evolutionary response to successive political crises.

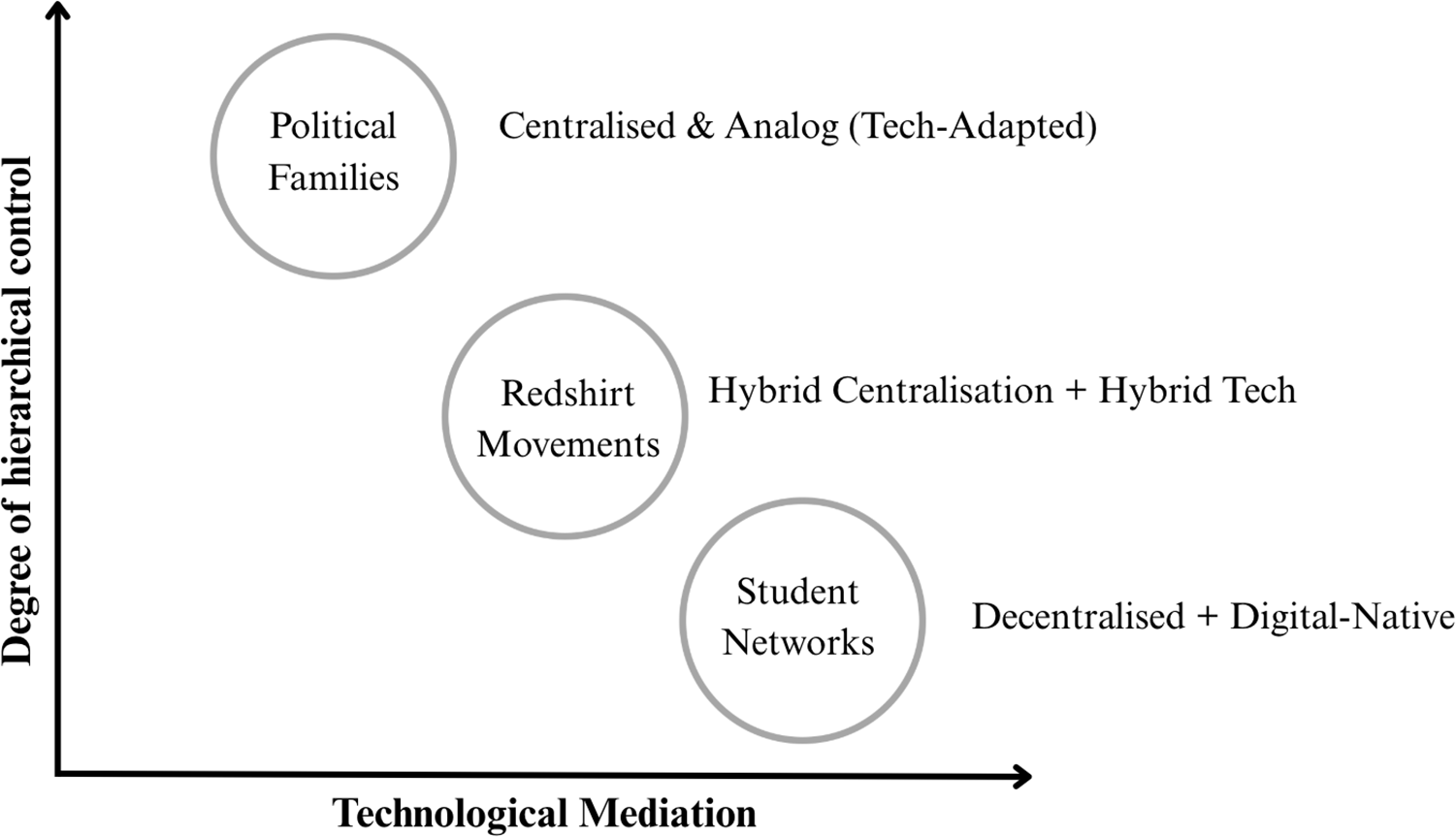

This analysis treats them as ideal types to illustrate a partial, incomplete shift from persistent, hierarchical analogue clientelism (political families) to adaptive hybrid structures (the Red Shirts, peaking around 2010) and finally to decentralised, digitally native networks (student movements, peaking around 2020), with each new type of network facing heavy resistance from the state. This chronological progression demonstrates how repression and technological change have successively reshaped the strategies of political opposition, with the limitations and lessons of earlier movements informing the adaptations of later ones. Accordingly, the following comparison examines their organisational logics and adaptation strategies at their points of most salient activity to map this evolution, not to suggest they are perpetual or equal rivals in the current political arena (see Table 1).

Table 1. Comparative Analysis of Thai Political Networks

Source: Naruemon Thabchumpon (Reference Naruemon2016); Interviews and group discussions (2018–2024); Tanet Charoenmuang (Reference Charoenmuang, Montesano, Chong and Heng2019); Kanokrat Lertchoosakul (Reference Lertchoosakul2021); Aim Sinpeng (Reference Sinpeng2021a, Reference Sinpengb); Nishizaki (Reference Nishizaki2022); Suthikarn Meechan (Reference Meechan2023, Reference Meechan2024)

Political families remain rooted in provincial aristocratic-style networks that predate electoral politics. Many descend from local nobility or Sino-Thai elites who inherited both authority and patronage resources. The patron-client ties they employ are akin to clientelistic relationships formed by the aristocracy prior to the electoral era. Before the 2014 coup, political families operated with hierarchical structures centred on family patriarchs or, less frequently, matriarchs, leveraging local brokers to maintain patronage networks and mobilise voter support. The Red Shirts, organised by the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD), employed a hybrid structure that connected central leadership with provincial hubs and community radio networks—a system that effectively disseminated ideology and coordinated mass demonstrations from rural bases. At the time, student activism had become institutionalised within university frameworks, leveraging institutional channels for political expression while remaining relatively marginal in national politics, at least since the 1990s.

The 2014 coup necessitated significant structural adaptations across all three networks, revealing stark differences in their political objectives and operational strategies. Political families, such as the Jureemas and Burunupakorn clans, embraced digital tools—such as Facebook and TikTok campaigns or Line groups—to modernise their outreach while reinforcing, rather than replacing, traditional patronage systems. This digital overlay supplements the enduring analogue power structures reinforced by brokers at middle and lower levels that allow the political families to maintain hierarchical control. In contrast, the Red Shirts’ transition from a hub-and-spoke model to a fractured wheel exemplifies how state repression can accelerate organisational innovation, forcing a shift towards decentralised resilience over central control. This adaptation is not readily available to hierarchical political family networks. Following the suppression of community radio, the Red Shirts fragmented into semi-autonomous Facebook groups—a more disruptive and enduring transformation. This shift preserved grassroots connections but at the cost of national coherence and communal unity, creating a paradox of greater online reach alongside weaker social bonds. Within these spaces, administrators and influencers cultivate ideological echo chambers (Kurlantzick Reference Kurlantzick2014: 15), eroding the personal ties that once defined the movement.

Student movements underwent the most radical transformation, abandoning formal hierarchies in favour of leaderless mesh networks reliant on encrypted apps like Signal and Telegram, complemented by symbolic tactics such as the three-finger salute. Their digitally native strategies prioritise security and viral mobilisation via meme warfare, enabling short-term evasion of state surveillance. However, these tools have proven less effective for sustained movement-building, leaving their long-term political impact uncertain.

Thailand’s political networks have employed diverse survival strategies to navigate junta repression, each entailing distinct trade-offs. Political families, like the Jureemas clan, have pursued stability through alignment with pro-junta factions, leveraging their entrenched local influence to weather regime changes. Conversely, the Buranopakorn clan has opted for a more confrontational approach, maintaining its power base in Chiang Mai’s municipal politics—a Red Shirts stronghold—by balancing resistance with traditional patronage. This pragmatic stance helps them preserve power but also exposes them to significant risks, including the targeted elimination of leaders and a generational shift towards more progressive politics—trends that could undermine their reliance on established patronage systems.

The Red Shirts have responded with a strategy of decentralised resistance, relying on grassroots hubs and broadcasting platforms for local mobilisation. However, their hybrid structure struggles to reconcile deep communal ties with effective national coordination. Student movements, on the other hand, have embraced radical reinvention through leaderless, digitally native networks, which helps them evade suppression but leaves them without institutional foundations. While effective in the short term, these evasion tactics often result in recurring burnout and internal conflicts, limiting their long-term political impact.

Concerning adaptation, oppression has unevenly accelerated organisational innovation among Thailand’s political networks, leading to complex adaptations in response to regime coercion and technological advances. Political families have carefully added digital tools to their outreach efforts to make them more modern. For example, they use voter databases and Line groups to strengthen their existing hierarchies. This strategy allows them to maintain local dominance, but their centralised leadership makes them vulnerable to top-down coercion, such as the imprisonment or co-option of key figures, and challenges from emerging political rivals. The Red Shirts thrive during periods of upheaval by leveraging grassroots networks and local broadcasting, but they find their decentralised structures fractured under sustained repression. Their approach creates a paradox where strong communal bonds exist alongside weak national coordination, limiting their ability to scale resistance effectively. Student movements represent the most radical form of adaptation, adopting leaderless digital networks and encrypted messaging to evade state surveillance.

As Morozov (Reference Morozov2011) contends, the internet can paradoxically reinforce authoritarianism by making dissent easier to monitor and suppress, whereas digital activism itself can be shallow and potentially distract from more effective offline organising. While their agile, tech-savvy tactics facilitate short-term survival, the absence of institutional foundations often leads to activist burnout and infighting, underscoring the inherent tension between evasion tactics and the long-term work of movement-building. These cases collectively demonstrate how Thailand’s opposition networks adapt to repression through divergent strategies, each achieving resilience in distinct ways but often at a significant cost.

Thailand’s experience exemplifies a broader tension in contemporary political organising: resilience depends not only on technological adoption but also on balancing competing imperatives—security versus scalability, decentralisation versus coherence, and innovation versus institutional memory. The most sustainable movements combine digital adaptability with structured long-term public engagement, evolving beyond reactive protest into sustained political influence. These cases reveal an evolutionary spectrum—from rigid hierarchies to decentralised networks—with hybrid forms occupying the middle ground. Repression catalyses divergent innovations, yet each approach reflects deeper generational and ideological rifts within Thailand’s opposition. For instance, older political dynasties, accustomed to analogue methods and centralised control, have adapted by integrating technology into their existing structures, reflecting a more traditional and established political worldview. In contrast, younger activists—often associated with student movements—have gravitated towards decentralised, digitally native networks, reflecting both their technological fluency and their preference for fluid, non-hierarchical organising. The Red Shirts movement occupies an intermediate position, blending traditional grassroots structures with selective technological adoption—a hybridity that mirrors its ideologically and generationally diverse base. These divergent adaptive strategies carry significant implications for democratic resistance in digitally mediated authoritarian contexts (see Figure 5). Ultimately, the resilience and potential effectiveness of opposition groups depend on understanding how their underlying structures shape innovation under conditions of state repression. This analysis concludes that the adoption of digital tools is not uniform; rather, it is mediated by pre-existing organisational forms and generational dispositions, which collectively shape the broader landscape of political contention.

Figure 5. A Spectrum of Nature of Networks in Thai Politics.

Figure 5 maps Thailand’s political networks along two analytical axes: centralised authority (vertical) and reliance on digital tools (horizontal). This heuristic framework synthesises the country’s evolving political landscape by illustrating the dominant organisational logic of key actors rather than capturing the full fluidity of each case. For example, the Red Shirts’ plotted position reflects their post-2014 “fractured wheel” structure, a departure from their more centralised pre-coup organisation. Political families dominate the upper-left quadrant, maintaining rigid hierarchies through analogue patronage systems—brokers, local politicians, local officials, and community radio—while selectively co-opting digital tools to reinforce, rather than replace, these traditional structures. Student movements cluster in the lower-right quadrant, embodying radical decentralisation and a near-total reliance on native digital tactics, such as hashtags, encrypted messaging, and online campaigns. The Red Shirts occupy an intermediate position, blending formal leadership with grassroots autonomy via hybrid communications that span community radio and social media. However, this adaptability, while enabling resilience, also exposes the movement to instability and fragmentation.

This spectrum reveals a fundamental inverse relationship between hierarchy and digital reliance. Highly centralised networks depend on traditional power structures to maintain control, thereby reducing the incentive for widespread adoption of digital tools. By contrast, decentralised networks rely on digital technologies to compensate for their lack of formal authority and to coordinate collective action. The 2014 coup marked a critical turning point, accelerating this adaptation as grassroots actors leveraged digital platforms to bypass traditional intermediaries and flatten organisational hierarchies. Nevertheless, traditional power structures have proven resilient. Hybrid actors—such as pro-Thaksin parties—strategically combine top-down command with digital outreach, demonstrating how established organisations co-opt technological innovations to maintain, rather than transform, their core strategies of influence.

Repression shapes these networks in distinct ways: political families restore centralised leadership at the expense of local autonomy; the Red Shirts fragment into semi-autonomous, community-based clusters; and student movements retreat into dormancy while retaining encrypted infrastructure for rapid reactivation. This adaptive spectrum—from centralised fragility to decentralised resilience—demonstrates that political actors respond to authoritarian constraints according to structural compatibility as much as innovative capacity. More broadly, it reveals a persistent organisational dilemma: decentralised networks gain resilience against repression but often lack coordinated strategic capacity, whereas hierarchical networks mobilise resources and wield authority efficiently but remain acutely vulnerable to targeted suppression. Thus, the most sustainable movements are likely those that can strategically blend hierarchical cohesion with grassroots adaptability.

The analytical boundaries between network types remain porous and fluid. For example, the support of some former Red Shirts for the Move Forward Party (now the People’s Party) demonstrates how movement-based networks can transition into more institutionalised political forms without erasing their ideological origins. Recent local elections (2025) further exemplify this adaptive capacity, showing how political families leveraged social media and younger dynastic candidates to counter the rise of reformist parties like the People’s Party (Chambers Reference Chambers2025; Chambers and Watcharapol Supajakwattana Reference Chambers and Supajakwattana2025). This demonstrates that even as digital activism reshapes political engagement, traditional elites continue to adapt their strategies to maintain influence, integrating hierarchical control with new forms of mobilisation.

In conclusion, this framework demonstrates how political organisation in Thailand is evolving beyond the broker system and provides comparative insights into how networks worldwide adapt to the dual pressures of technological change and state suppression. Technology serves as both a disruptive force and a tool for co-option, enabling decentralised actors to resist repression while allowing hybrid hierarchies to sustain influence. When states actively restrict digital access during periods of resistance—as seen recently in Bangladesh—concrete, place-based structures regain critical importance. This dynamic underscores the delicate balance between innovation and institutional resilience.

Conclusion

The partial, ongoing transformation of Thailand’s political networks —from hierarchical patronage systems to complex, fluid, decentralised networks of vertical and horizontal ties–indicates a significant change in the structure and struggle for power. Although traditional political families, similar to their counterparts in the Philippines, cautiously adopt digital tools to maintain patronage and reinforce control, grassroots actors such as Thailand’s Red Shirts and student collectives exemplify broader trends that have been observed in Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. These movements utilise digital platforms to amplify marginalised voices and establish adaptive networks that can endure state repression. The alterations significantly affect Thailand’s democratic progression: the reduction of broker-dependent clientelism may diminish elite control in electoral politics, while decentralised digital activism enhances the visibility of marginalised voices.

To avoid overgeneralising, this claim requires significant nuance. Thailand’s conservative social order, underpinned by the military-monarchy nexus, has proven highly resistant to these new forms of oppositional networks, ensuring that traditional power structures remain resilient despite the erosion of clientelism and the rise of digital activism. This study demonstrates that political networks are evolving in complex, uneven ways. Although traditional patron-client relationships have eroded since the colonial period, they continue to exist through intermediaries and are reinforced by modern communication technologies, especially in engaging younger voters. Political families, including the Buranupakorn and Jureemas families, enhance rather than supplant these connections through digital outreach. The Red Shirts represent a hybrid model that integrates hierarchical leadership with community radio and social media to promote ideological unity while preserving certain face-to-face patron-client interactions. Conversely, student movements have predominantly forsaken conventional hierarchies, opting for decentralised, egalitarian digital networks that emphasise flexibility and anonymity rather than centralised authority.

Yet these movements continue to face enduring challenges in coordination, sustainability, and evasion of state surveillance. The democratic trajectory of Thailand has been significantly affected by this evolution. Student movements utilise technology to dismantle hierarchical structures, whereas political families leverage it to strengthen them. This fundamental divergence elucidates the challenges faced by the Thai establishment in suppressing youth-led mobilisations, despite the effective dismantling of Red Shirts strongholds: a decentralised network cannot easily be neutralised through traditional strategies of leadership decapitation. These dynamics highlight the operational vulnerabilities and the emancipatory potential of digital mobilisation in contested political contexts.

These developments challenge the notion of nationally unified, linear democratisation. Variations in digital access, generational divides in technology adoption, and the enduring influence of the military complicate this narrative. Rural areas remain tethered to analogue patronage, while urban youth dominate digital discourse. Moreover, the rise of new network forms—driven by regime changes, repression, and electoral competition—suggests that ideological and economic shifts alone may not be the primary forces reshaping Thailand’s class system. Instead, more participatory and egalitarian political organisations, embedded with ideological change in their very structures, could prove more resilient against repression and more effective at undermining traditional hierarchies than ideology or economic transformation alone.

Future research should investigate how emerging technologies—such as AI-generated disinformation, encrypted organising tools, and digital surveillance systems—are transforming political mobilisation, especially in the context of increased authoritarian surveillance, which also raises critical questions about the cohesion and sustainability of leaderless movements. Comparative studies throughout Southeast Asia are necessary to evaluate how varied political environments adapt to or resist digital disruption, including the impact of disparities in digital access, generational divides, and regime counterstrategies. Ultimately, Thailand’s developing networks illustrate a conflict between innovation and authoritarian-imposed continuity, wherein technology facilitates resistance but does not ensure systemic transformation. This dynamic provides essential insights for researchers in authoritarian resilience and global digital activism, emphasising both the potential and constraints of networked politics in contested democracies.

Competing Interests

The authors report no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgement

Suthikarn Meechan thanks the Mahasarakham University for financial support for this research project. James Ockey would like to thank the Nicholas Tarling Trust for providing funding for field research for this project.