Introduction

There is growing recognition of the heterogeneous nature of auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) – hearing voices without any external stimuli – which have long been considered a cardinal symptom in schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs). Large-scale studies have reported diverse phenomenological characteristics of AVH in people with SSDs, which differed in features such as linguistic complexity, acoustic properties, location, identity, and personal pronouns (Larøi, Reference Larøi2006; Nayani & David, Reference Nayani and David1996; Plaze et al., Reference Plaze, Paillere-Martinot, Penttila, Januel, De Beaurepaire, Bellivier and Cachia2011; Stephane, Thuras, Nasrallah, & Georgopoulos, Reference Stephane, Thuras, Nasrallah and Georgopoulos2003). A formative cluster analysis of auditory hallucinations based on their content and themes has identified four different subtypes, namely those that involved commands and running commentary, that sounded like one’s own thought, that were replays of memory, and nonverbal sounds (McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Trauer, Mackinnon, Sims, Thomas and Copolov2014). Each subtype may map onto distinct neurocognitive mechanisms and require different etiological accounts (Jones, Reference Jones2010; McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Thomas, Strauss, Dodgson, Jones, Woods and Sommer2014). For AVH, one prominent model is the inner speech theory, which suggests that some forms of AVH, particularly those that are free-flowing and resemble the verbal mentation typical of inner speech, are a case of misattribution of one’s inner speech to an external source (Allen, Aleman, & McGuire, Reference Allen, Aleman and McGuire2007; Fernyhough, Reference Fernyhough2004; Jones & Fernyhough, Reference Jones and Fernyhough2007), although the precise mechanistic instantiation remains a matter of debate (Fletcher & Frith, Reference Fletcher and Frith2009; Moseley, Fernyhough, & Ellison, Reference Moseley, Fernyhough and Ellison2013; Whitford, Reference Whitford2019; Wilkinson & Fernyhough, Reference Wilkinson, Fernyhough and Radman2017).

While these neurocognitive accounts provide a potential framework to explain how AVH may be generated, they do not address why inner speech is readily attributed externally (rather than internally) to form AVH (Fernyhough, Reference Fernyhough2004). To this end, a developmental approach to inner speech has been proposed (Fernyhough, Reference Fernyhough1996). Specifically, inner speech under Vygotsky’s view (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky, Rieber and Carton1987) is conceptualized as the end product of a gradual internalization of external dialogue that a child engages with her caretakers, which moves from explicit exchanges with a social target (i.e. conversation) and later on with oneself (i.e. private speech), to fully internalized utterances (i.e. inner speech) that ultimately reduce to a more condensed form, though people can flexibly move between these forms (Fernyhough, Reference Fernyhough2004; Fernyhough & Borghi, Reference Fernyhough and Borghi2023). An upshot of this approach is that inner speech, even in its most abstract form, is “irreducibly dialogic” (Jones & Fernyhough, Reference Jones and Fernyhough2007). In other words, the inherently social nature of inner speech, combined with a faulty self-monitoring system, may heighten the likelihood of external attribution. This could provide one way to explain why AVH often contain back-and-forth qualities in the form of multiple voices, but it remains to be seen how it can be integrated with other frameworks (cf. Kapur, Reference Kapur2003; Morrison, Reference Morrison2001).

It remains unclear whether the frequency and phenomenology of inner speech are different in voice-hearers with SSDs compared with healthy individuals. The re-expansion model of AVH proposed by Fernyhough (Reference Fernyhough2004), which is derived from Vygotsky’s view (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky, Rieber and Carton1987), suggests that while voice-hearers would enjoy a normal quantity of inner speech, AVH occur when they misinterpret the normatively re-expanded inner speech as alien under conditions of stress. Indeed, an early study using unstructured interviews found no differences in the quantity and form of inner speech between individuals with SSDs and healthy individuals (Langdon, Jones, Connaughton, & Fernyhough, Reference Langdon, Jones, Connaughton and Fernyhough2009). However, subsequent studies examining the quality of inner speech found mixed results using a psychometrically validated instrument, the Varieties of Inner Speech Questionnaire (VISQ), which, in its revised version, categorized the phenomenological qualities of inner speech into five varieties: dialogic (inner speech that occurs as a back-and-forth conversation), evaluative/critical, other people (inner speech in others’ voices), condensed (abbreviated sentences), and positive/regulatory (Alderson-Day et al., Reference Alderson-Day, Mitrenga, Wilkinson, McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough2018; McCarthy-Jones & Fernyhough, Reference McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough2011). Specifically, while de Sousa et al. (Reference de Sousa, Sellwood, Spray, Fernyhough and Bentall2016) found that individuals with SSDs endorsed more other people and condensed inner speech than healthy individuals, Rosen et al. (Reference Rosen, McCarthy-Jones, Chase, Humpston, Melbourne, Kling and Sharma2018) found higher levels of all varieties of inner speech in people with psychosis, except for condensed inner speech. Evaluative and other people inner speech were found to be associated with the severity of hallucinations (de Sousa et al., Reference de Sousa, Sellwood, Spray, Fernyhough and Bentall2016; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, McCarthy-Jones, Chase, Humpston, Melbourne, Kling and Sharma2018), and higher dialogic inner speech was recently found to be correlated with more severe hallucinations (Mahfoud et al., Reference Mahfoud, Hallit, Haddad, Fekih-Romdhane and Haddad2023).

The reliance on participants’ retrospective estimation of inner speech experiences may lead to biases (Heavey & Hurlburt, Reference Heavey and Hurlburt2008; Hurlburt, Alderson-Day, Kühn, & Fernyhough, Reference Hurlburt, Alderson-Day, Kühn and Fernyhough2016; Hurlburt, Heavey, & Kelsey, Reference Hurlburt, Heavey and Kelsey2013). One way to circumvent such issues is to employ experience sampling methodology (ESM) to examine the presence and relations of inner speech, AVH, and affect moment-by-moment, given that these experiences fluctuate across time. As a structured diary in the daily living environment, ESM has been proven to be a feasible and reliable tool to capture subjective momentary experiences like AVH and affect in people with SSDs (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Eisner, Allan, Cartner, Torous, Bucci and Thomas2023; Myin-Germeys et al., Reference Myin-Germeys, Kasanova, Vaessen, Vachon, Kirtley, Viechtbauer and Reininghaus2018; Oorschot, Kwapil, Delespaul, & Myin-Germeys, Reference Oorschot, Kwapil, Delespaul and Myin-Germeys2009; So et al., Reference So, Chung, Tse, Chan, Chong, Hung and Sommer2020).

The present study aimed to examine the frequency and phenomenological qualities of inner speech based on the 26-item VISQ – Revised (VISQ-R) in individuals with SSDs and current AVH (‘SSD’) and healthy controls (‘HC’) using ESM. As previous cross-sectional studies reported higher levels of distinct varieties of inner speech in people with SSDs compared with healthy participants (de Sousa et al., Reference de Sousa, Sellwood, Spray, Fernyhough and Bentall2016; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, McCarthy-Jones, Chase, Humpston, Melbourne, Kling and Sharma2018), we hypothesized that SSD would report higher momentary intensity of various inner speech varieties than HC, but the frequency of inner speech moments would be similar between the two groups. Within the SSD participants, based on the established theoretical associations between inner speech and AVH, we hypothesized that the momentary intensity of inner speech varieties would be associated with the momentary intensity of AVH. To evaluate the assertion of the re-expansion model of AVH, where misattributions occur when inner speech is re-expanded under stress (Fernyhough, Reference Fernyhough2004), we took a simple approach of operationalizing stress as negative affect (NA) and explored the moderating role of momentary affect and baseline negative emotional states in the momentary associations between inner speech varieties and AVH within SSD, given that stress and affect are closely related (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Myin-Germeys, Derom, Delespaul, van Os and Nicolson2007), and that momentary affective dynamics are disrupted in schizophrenia (So et al., Reference So, Chau, Chung, Leung, Chong, Chang and Sommer2023).

Methods

Participants

Two groups of adult participants took part in the study: SSD and HC. For the SSD group, inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of an SSD based on the Chinese-bilingual Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Axis I Disorders (SCID; So et al., Reference So, Kam, Leung, Chung, Liu and Fong2003) and an age of 18 years or above. The presence of AVH was defined by scoring 3 or above (from a range of 1–7) on item P3 hallucinatory behavior of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler1987) in the past week, with follow-up on the Psychotic Symptoms Rating Scales (PSYRATS; Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier, & Faragher, Reference Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier and Faragher1999) to confirm that the hallucinations were auditory-verbal in nature. HC participants had no present or past diagnosis of a DSM-IV Axis I disorder (based on SCID). Exclusion criteria for all groups included a history of alcohol or substance dependence within the past year (except nicotine dependence), a history of a neurological illness, drug-induced or organic psychosis, and intellectual disability based on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Fourth Edition (Hong Kong) short form (WAIS-IV[HK]; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2008).

SSD participants were outpatients referred by clinicians from public psychiatric services in the New Territories East Cluster and the Kowloon West Cluster of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority. HC participants were recruited through university newsletters and word-of-mouth, and were age- and gender-matched to the SSD group. The study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong-New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (2020.477) and the Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee (KW/EX-21-038(157-03)), and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

The novelty of our variables (e.g. inner speech and AVH), lack of prior effect size estimates, and the potential for biased estimates with a pilot study (Albers & Lakens, Reference Albers and Lakens2018) precluded an a priori power analysis. Thus, we targeted 35 participants per group, drawing on a review of 68 ESM studies in psychosis, which reported a median sample size of 35 (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Eisner, Allan, Cartner, Torous, Bucci and Thomas2023) and recent ESM studies examining within-person effects of AVH in people with SSDs (Fielding-Smith et al., Reference Fielding-Smith, Greenwood, Wichers, Peters and Hayward2020; So et al., Reference So, Chung, Tse, Chan, Chong, Hung and Sommer2020). With a maximum of 60 observations per participant (see ESM procedure), this sample size should provide adequate power to test the hypotheses.

Measures

Baseline measures

Symptom severity ratings for the SSD participants were obtained by administering the PANSS (Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler1987) and the PSYRATS (Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier, & Faragher, Reference Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier and Faragher1999) during semi-structured interviews by graduate-level psychologists who were trained and supervised by an experienced clinical psychologist or psychiatrist. The validated Chinese version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales – Short Form (DASS-21; Moussa, Lovibond, & Laube, Reference Moussa, Lovibond and Laube2001) was used to assess levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. General intelligence was estimated using the WAIS-IV[HK] short form (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2008).

ESM measures

All participants were provided with an iPod Touch (fifth generation) preinstalled with a custom-built ESM app. The app emitted a ‘beep’ signal 10 times a day over 6 consecutive days at pseudo-random moments, with each signal at least 30 min apart. The prompts would only occur during participants’ waking hours within a 10–12-h timeframe. This signal-contingent protocol has been shown to lead to satisfactory compliance in our previous ESM studies (So et al., Reference So, Chung, Tse, Chan, Chong, Hung and Sommer2020, Reference So, Chau, Chung, Leung, Chong, Chang and Sommer2023). Upon each signal, all participants were asked to respond to the same set of ESM items covering inner speech and affect. The SSD group also responded to items relating to AVH. All ESM items were rated on 7-point Likert scales ranging from ‘Not at all’ (1) to ‘Very much’ (7). Each ESM questionnaire was only accessible for 15 min after the signal emission. Before the actual testing, all participants completed a practice run, during which the distinction between the inner speech and AVH items was emphasized for the SSD group. Specifically, as participants in the SSD group discussed their AVH experiences in detail with the researcher during the assessment interview, they were instructed to only refer to these experiences for the AVH item, and not the inner speech items, particularly when discerning the ‘other people’ inner speech from AVH.

For the inner speech varieties, five questions from the VISQ-R (Alderson-Day et al., Reference Alderson-Day, Mitrenga, Wilkinson, McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough2018) were selected following Alderson and Fernyhough (Reference Alderson-Day and Fernyhough2015b), wherein the item with the highest factor loading from each factor was selected based on the original VISQ-R factor analysis (Alderson-Day et al., Reference Alderson-Day, Mitrenga, Wilkinson, McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough2018). They were translated into Chinese through a forward-backward translation process by two authors who are proficient in both Chinese and English (LC and SS) and adapted to fit the momentary nature of ESM. They began with the phrase ‘At the time of the alert’, followed by:

-

(1) Were you having a dialogue with yourself in your head? (Dialogic)

-

(2) Were you talking to yourself in a critical way in your head? (Evaluative)

-

(3) Were you having the experience of the voices of other people asking you questions in your head? (Other people)

-

(4) Were you thinking in shortened words compared with your normal, out-loud speech? (Condensed)

-

(5) Were you calming yourself down by talking silently to yourself? (Positive)

An ‘inner speech moment’ (yes/no) was determined by a score >1 (on a 1–7 scale) on any of the five inner speech items in an ESM entry.

For affect, three items (irritated, low, and tense) on NA and three items (cheerful, relaxed, and contented) on positive affect (PA) were included, which have been found to have good internal reliability in our previous ESM studies in people with SSDs (So et al., Reference So, Chung, Tse, Chan, Chong, Hung and Sommer2020, Reference So, Chau, Chung, Leung, Chong, Chang and Sommer2023). An additional item assessing AVH experience in the SSD group was phrased as follows: ‘At the time of the alert, did you hear voices that other people could not hear?’ (Kimhy et al., Reference Kimhy, Wall, Hansen, Vakhrusheva, Choi, Delespaul and Malaspina2017; So et al., Reference So, Chung, Tse, Chan, Chong, Hung and Sommer2020). An ‘AVH moment’ (yes/no) was determined by a score >1 (on a 1–7 scale) on the AVH item in an ESM entry.

As previous studies have indicated that individuals with SSDs can differentiate between their inner speech and AVH based on the identity of the speaking voice, content, and controllability of the auditory experiences (de Sousa et al., Reference de Sousa, Sellwood, Spray, Fernyhough and Bentall2016; Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore, & Mishara, Reference Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore and Mishara2008; Langdon, Jones, Connaughton, & Fernyhough, Reference Langdon, Jones, Connaughton and Fernyhough2009), three adapted items from Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore, and Mishara (Reference Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore and Mishara2008) assessing these features were included immediately following the set of inner speech items and the AVH item, respectively, to evaluate the participants’ ability to appraise these subjective experiences moment-to-moment. As these items were designed as branching items, they were re-coded as not applicable when participants’ responses indicated absence of inner speech or AVH moments. They were phrased as follows:

-

(1) Did these inner speeches (or voices) sound the same as your own speaking voice? (Identity)

-

(2) Did these inner speeches (or voices) say things that you would ordinarily think to yourself? (Content)

-

(3) Did you have control over these inner speeches (or voices)? (Controllability)

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the GAMLj3 module (version 3.4.2) in jamovi (Gallucci, Reference Gallucci2019). First, ESM data were aggregated across moments to compare their mean levels between groups. Next, linear mixed modeling with restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for the multilevel structure of ESM data, where multiple momentary responses (level 1) are nested within individual participants (level 2). All available data were used, and no data imputation was applied to missing data. Outcome variables were entered uncentered, while ESM predictor variables were person-mean centered (within each participant) and baseline predictor variables (i.e. DASS-21 scale scores and PSYRATS auditory hallucinations score) were grand-mean centered (across the entire sample) to disentangle within-person and between-person effects, respectively (Curran & Bauer, Reference Curran and Bauer2011; Wang & Maxwell, Reference Wang and Maxwell2015). In all models, random intercepts were included. Given the moderate sample size, random slopes for the main effects were considered when likelihood ratio tests suggested enhanced model fit, but random slopes for interaction effects were not included to ensure reliable parameter estimation and model parsimony (Lafit et al., Reference Lafit, Revol, Cloos, Kuppens and Ceulemans2025). In the case of convergence issues, random slopes that produced the best model fit, as indicated by a lower Akaike Information Criterion, were retained. An independent random-effects covariance structure was specified to permit unique variances for each random effect.

To examine differences in the momentary intensity of inner speech varieties in the two groups, separate models with inner speech varieties (dialogic, evaluative, other people, condensed, and positive) as outcome variables, and Group (HC and SSD) as the predictor, were tested.

Within the SSD group, to examine the momentary associations between inner speech varieties and AVH, as well as the moderating effect of affect and baseline DASS-21 scale scores on these associations, separate models with AVH as outcome variable and the five inner speech varieties, along with their interactions with PA, NA, and baseline DASS-21 scale scores, as predictor variables, were tested. In all models testing for an interaction effect, the main effects were also included.

Exploratory analyses examining the within-moment associations between inner speech varieties and affect, as well as the moderating effect of Group, were performed by testing separate models that included the five inner speech varieties as outcome variables, and PA, NA, and baseline DASS-21 scale scores, along with their interactions with Group, as predictor variables.

Results

A total of 36 SSD and 37 HC participants were recruited, among whom two were not able to complete the ESM assessment, and five responded to <30% of ESM entries (i.e. at least 18 responses out of 60), and were therefore excluded per previous studies (e.g. So et al., Reference So, Chung, Tse, Chan, Chong, Hung and Sommer2020). The final sample consisted of 32 SSD and 34 HC participants, with 1,390 and 1,623 total ESM observations, respectively. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. There were no differences in age and gender between the two groups (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and healthy controls

Note: Mean and standard deviation are presented where appropriate. DASS-21, depression anxiety stress scales – short form; PANSS, positive and negative syndrome scale; PSYRATS, psychotic symptom rating scales. Chi-squared and Welch’s t-tests were used as appropriate, and statistically significant comparisons (p < .05) are shown in bold.

a n = 31.

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics (i.e. mean levels) of the ESM items in the two groups. Across the 6-day assessment period, the two groups did not differ in the ESM compliance rate (range = 33.0–100%). All SSD participants reported at least one AVH moment, except for one individual, with a total of 952 (69.0%) moments captured. For inner speech moments, all but one participant in each group (a different individual in SSD) reported at least one inner speech moment, totaling 1,181 (85.0%) moments for SSD and 1,036 (63.8%) moments for HC.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of ESM items assessing affect, inner speech, and AVH in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and healthy controls

Note: Inner speech rate refers to the percentage of inner speech moments, determined by a score >1 (on a 1–7 scale) on any of the five inner speech items, across all responded moments. AVH rate refers to the percentage of AVH moments, determined by a score >1 (on a 1–7 scale) on the AVH item, across all responded moments. Percentage, mean, and standard deviations are presented where appropriate. IS, inner speech; NA, negative affect; PA, positive affect. Welch’s t-tests were used, and statistically significant comparisons (p < .05) are shown in bold.

a n = 31.

b n = 33.

Group comparisons on inner speech moments and phenomenological varieties of inner speech

For inner speech, SSD reported a significantly higher mean inner speech rate (i.e. number of inner speech moments) than HC, as shown in Table 2. SSD reported significantly higher momentary intensity of evaluative, B = 1.01, standard error [SE] = 0.26, p < .001, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [0.51, 1.52]; other people, B = 1.22, SE = 0.24, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.74, 1.70]; condensed, B = 0.65, SE = 0.32, p = .044, 95% CI = [0.03, 1.27]; and positive inner speech, B = 0.71, SE = 0.31, p = .025, 95% CI = [0.10, 1.32], compared with HC. Dialogic inner speech showed no significant group difference, B = 0.24, SE = 0.33, p = .468, 95% CI = [−0.40, 0.87].

As shown in Table 2, SSD reported significantly lower mean levels in the voice identity, content, and controllability items for inner speech (p < .05) than HC. Within the SSD group, paired-sample t-tests did not find a significant difference in voice identity, t(29) = 1.30, p = .205, d = 0.24, 95% CI = [−0.11, 0.51]; content, t(29) = 0.22, p = .825, d = 0.04, 95% CI = [−0.24, 0.30]; and controllability, t(29) = 1.01, p = .320, d = 0.18, 95% CI = [−0.46, 0.15], between inner speech and AVH.

For affect, SSD reported significantly higher momentary intensity of NA, B = 0.71, SE = 0.27, p = .010, 95% CI = [0.18, 1.24], but not PA, B = −0.45, SE = 0.30, p = .135, 95% CI = [−1.03, 0.13], compared with HC.

Within the SSD group, were the momentary intensities of inner speech varieties related to the momentary intensity of AVH and baseline AVH severity?

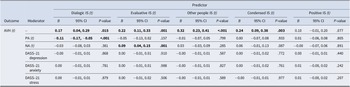

As shown in Table 3, higher levels of dialogic, evaluative, other people, and condensed inner speech, but not positive inner speech, significantly predicted a higher level of AVH. In other words, the more intense the subjective experience of (most of) the inner speech varieties, the more severe the AVH experience was, except for positive self-regulatory speech. All the results remained unchanged after adjusting for IQ and education level.

Table 3. Momentary associations between inner speech varieties and AVH, and the moderating effect of momentary affect and baseline negative emotional states in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (n = 32)

Note: B, unstandardized fixed regression coefficients; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals; DASS-21, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales – Short Form; IS, inner speech; NA, negative affect; PA, positive affect. t denotes ESM measures. Statistically significant results (p < .05) are shown in bold.

Moreover, baseline PSYRATS auditory hallucinations score positively predicted momentary intensities of all inner speech varieties (Dialogic IS: B = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p = .010, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.15]; Evaluative IS: B = 0.11, SE = 0.03, p = .002, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.17]; Other people IS: B = 0.10, SE = 0.03, p = .002, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.16]; Condensed IS: B = 0.10, SE = 0.03, p = .004, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.17]; Positive IS: B = 0.09, SE = 0.03, p = .010, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.16]).

Within the SSD group, were the momentary associations between inner speech varieties and AVH moderated by the momentary NA and baseline negative emotional states?

As shown in Table 3, momentary NA significantly moderated the association of evaluative inner speech with AVH, with simple effects revealing a stronger association between evaluative inner speech and AVH at higher NA levels (mean NA + 1 SD: B = 0.23, SE = 0.06, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.12, 0.34] vs. mean NA - 1 SD: B = 0.08, SE = 0.06, p = .173, 95% CI = [−0.04, 0.20]). However, baseline DASS-21 scale scores showed no significant moderating effects.

Momentary PA significantly moderated the association of dialogic inner speech with AVH, with simple effects revealing a stronger association between dialogic inner speech and AVH at lower PA levels (mean PA + 1 SD: B = 0.06, SE = 0.07, p = .367, 95% CI = [−0.08, 0.20] vs. mean PA - 1 SD: B = 0.26, SE = 0.07, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.12, 0.39]). All the results remained unchanged after adjusting for IQ and education level.

Were the momentary intensities of inner speech varieties related to affect, and were these associations moderated by Group?

As shown in Table 4, all five inner speech varieties showed significant positive associations with NA, indicating that higher momentary NA predicted more intense inner speech experiences across both groups. The association between positive inner speech and NA was moderated by Group, with simple effects revealing a stronger positive relationship in the HC group (B = 0.41, SE = 0.07, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.27, 0.55]) than in the SSD group (B = 0.17, SE = 0.08, p = .044, 95% CI = [0.00, 0.33]).

Table 4. Momentary associations between inner speech varieties and affect in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (n = 32) and healthy controls (n = 34)

Note: B, unstandardized fixed regression coefficients; 95% CI, 95% confidence intervals; DASS-21, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales – Short Form; IS, inner speech; NA, negative affect; PA, positive affect. t denotes ESM measures. Statistically significant results (p < .05) are shown in bold.

Furthermore, all five inner speech varieties showed significant positive associations with DASS-21 depression, DASS-21 anxiety, and DASS-21 stress, respectively, indicating that higher baseline negative emotional states predicted more intense inner speech experiences across both groups. The association between evaluative inner speech and DASS-21 anxiety was moderated by Group, with simple effects revealing a stronger positive relationship in the SSD group (B = 0.08, SE = 0.01, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.11]) than in the HC group (B = −0.00, SE = 0.04, p = .810, 95% CI = [−0.09, 0.07]).

In contrast, dialogic, evaluative, other people, and positive inner speech were negatively associated with PA, indicating that higher PA predicted reduced intensity of these inner speech varieties in both groups. The association between positive inner speech and PA was moderated by Group, with a stronger negative relationship in the HC group (B = −0.23, SE = 0.07, p = .002, 95% CI = [−0.36, −0.09]) compared with the SSD group (B = −0.00, SE = 0.08, p = .964, 95% CI = [−0.16, 0.15]).

Discussion

This study used ESM to investigate the momentary dynamics of inner speech, AVH, and affect in individuals with SSDs with current AVH (‘SSD’) and non-voice-hearing healthy controls (‘HC’). Using the ESM-adapted VISQ-R (Alderson-Day et al., Reference Alderson-Day, Mitrenga, Wilkinson, McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough2018), our findings reveal elevated inner speech moments and momentary intensity of inner speech varieties in people with SSDs compared with healthy participants. Within the SSD group, momentary inner speech varieties were associated with AVH, and the association between evaluative inner speech and AVH was amplified by momentary NA, underscoring the potential role of NA in the inner speech-AVH relationship.

Momentary varieties of inner speech

Participants with SSDs reported significantly higher levels of evaluative, other people, condensed, and positive inner speech compared with HC, with no difference in dialogic inner speech. These results align with questionnaire-based studies that showed elevated inner speech varieties in people with psychosis (de Sousa et al., Reference de Sousa, Sellwood, Spray, Fernyhough and Bentall2016; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, McCarthy-Jones, Chase, Humpston, Melbourne, Kling and Sharma2018), although the specific varieties differed. These results also contrast with Langdon, Jones, Connaughton, and Fernyhough (Reference Langdon, Jones, Connaughton and Fernyhough2009), which found no differences using unstructured interviews. There are at least two reasons that could account for these discrepancies: first, our SSD group involved participants who were experiencing AVH, which differs from previous studies using cohorts with a mixed AVH status; second, the ecological validity of ESM may capture fleeting experiences like inner speech that retrospective methods, such as cross-sectional questionnaires, overlook, which rely on participants’ estimate (Heavey & Hurlburt, Reference Heavey and Hurlburt2008).

Importantly, a study comparing the responses collected through ESM and baseline VISQ found that the endorsement of inner speech experiences was typically lower for ESM than generalized self-report (Alderson & Fernyhough, Reference Alderson-Day and Fernyhough2015b). Therefore, the fact that people with SSDs who were experiencing AVH reported more inner speech moments and higher intensities of inner speech varieties than HC using ESM may indicate a distinct quantitative feature in this population. Indeed, in-depth descriptive methods have revealed rich inner experiences in schizophrenia (Hurlburt, Reference Hurlburt1990). Testing this hypothesis with a matched-diagnosis control group (i.e. an SSD group who were either not currently hallucinating or had no voice-hearing history) in future studies would confirm whether an enriched inner speech experience is specific to voice-hearing or SSD in general, and shed light on the functional significance of frequent (inner) self-talk, such as to satisfy a social need in response to loneliness (Reichl, Schneider, & Spinath, Reference Reichl, Schneider and Spinath2013), which has been found to increase the likelihood of hearing voices (Brederoo et al., Reference Brederoo, de Boer, Linszen, Blom, Begemann and Sommer2023). One intriguing possibility is that ‘excessive’ inner speech could strain the dysfunctional self-monitoring system in people with SSDs, as implicated by recent neurophysiological studies (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Whitford, Griffiths, Jack, Le Pelley, Spencer, Barreiros, Harrison, Han, Libesman, Pearson, Elijah, Godwin, Haroutonian, Nickerson, Chan, Chong, Lau, Wong and Harris2025; Whitford et al., Reference Whitford, Chung, Griffiths, Jack, Le Pelley, Spencer, Barreiros, Harrison, Han, Libesman, Pearson, Elijah, Godwin, Haroutonian, Nickerson, Chan, Chong, Lau, Wong and So2025), thereby increasing the risk of misattributing inner speech as AVH. Our results suggest that the assumption that people with SSDs who are experiencing AVH have fewer moments of inner speech than healthy counterparts (Fernyhough, Reference Fernyhough2004; Lysaker & Lysaker, Reference Lysaker and Lysaker2005) – because such experiences are externalized as AVH – may need to be reexamined.

Inner speech and AVH

Within people with SSDs, elevated levels of dialogic, evaluative, other people, and condensed inner speech, but not positive inner speech, were associated with more severe AVH as measured by both momentary ESM and PSYRATS at baseline. These findings extend previous cross-sectional data (de Sousa et al., Reference de Sousa, Sellwood, Spray, Fernyhough and Bentall2016; Mahfoud et al., Reference Mahfoud, Hallit, Haddad, Fekih-Romdhane and Haddad2023; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, McCarthy-Jones, Chase, Humpston, Melbourne, Kling and Sharma2018) by demonstrating the moment-to-moment parallels between several varieties of inner speech and AVH, and suggest that elevated inner speech experiences may be related to AVH specifically. Crucially, AVH are often dominated by derogatory content and appear in the forms of commands or commentary (Larøi et al., Reference Larøi, Thomas, Aleman, Fernyhough, Wilkinson, Deamer and McCarthy-Jones2019; McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Trauer, Mackinnon, Sims, Thomas and Copolov2014). The fact that momentary associations with AVH were found for inner speech varieties that involve negative content and back-and-forth conversations, but not for those that are affirmative and encouraging, could be taken as evidence at the phenomenological level that some forms of AVH may, in fact, be misattributed dialogic and evaluative inner speech (Jones & Fernyhough, Reference Jones and Fernyhough2007). More interestingly, despite higher levels of positive inner speech in SSD compared with HC participants, no relationship between positive inner speech and AVH was found, suggesting that negative semantics and/or prosody in inner speech may play an important role in the formation of AVH. That is, the functional link between inner speech generation and misattribution might be dependent on the type or content of the internal verbal mentation. It is worth noting that the present study only examined same-moment associations between inner speech and AVH and may therefore not have captured temporal dynamics that unfold over a longer period of time. One possibility is that positive inner speech could be engaged in response to AVH as efforts to self-soothe or to cope with the distress, which would be a worthwhile focus for future studies.

To our knowledge, the moderating effect of momentary NA (but not baseline negative emotional states, i.e. DASS-21 scale scores) on the link between AVH and evaluative inner speech provides the first empirical evidence supporting the re-expansion model’s emphasis on momentary stress as a misattribution trigger (Fernyhough, Reference Fernyhough2004). These findings indicate that transient negative states, rather than sustained states of negative emotions, may heighten the likelihood of perceiving inner speech as alien, and are consistent with the broader role of NA in driving AVH (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Lataster, Greenwood, Kuipers, Scott, Williams and Myin-Germeys2012; So et al., Reference So, Chung, Tse, Chan, Chong, Hung and Sommer2020).

The extent to which the misattribution model, primarily developed for AVH, can be generalized to explain hallucinations in other sensory modalities, particularly those that occur simultaneously or sequentially in time – known as multimodal hallucinations – remains unclear (Montagnese et al., Reference Montagnese, Leptourgos, Fernyhough, Waters, Larøi, Jardri, McCarthy-Jones, Thomas, Dudley, Taylor, Collerton and Urwyler2021). Considering hallucinatory experiences as generated by separable modality-general and modality-specific processes that interact flexibly within a hierarchically organized system might provide a fruitful conceptual framework for addressing this complexity (Fernyhough, Reference Fernyhough2019).

Distinguishing inner speech from AVH

Previous studies examining inner speech in people with SSDs have often assumed that participants can separate verbal thoughts from AVH (de Sousa et al., Reference de Sousa, Sellwood, Spray, Fernyhough and Bentall2016; Langdon, Jones, Connaughton, & Fernyhough, Reference Langdon, Jones, Connaughton and Fernyhough2009; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, McCarthy-Jones, Chase, Humpston, Melbourne, Kling and Sharma2018), but empirical evidence is scarce. One study by Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore, and Mishara (Reference Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore and Mishara2008) using an interview-based questionnaire found that the majority of their participants with SSDs reported being able to differentiate the two experiences most of the time, and the distinction was made primarily based on the identity of the voice (i.e. self or non-self), the verbal content, and how much control they could assert over them. Contrary to these findings, we found that people with SSDs endorsed the levels of these characteristics (i.e. how similar the inner speech/voice is to your own voice, how similar the inner speech/voice content is to your ordinary thoughts, and how much control over the inner speech/voice do you have) similarly for inner speech and AVH, and that HC endorsed them at significantly higher levels for inner speech. Our results thus suggest that people with SSDs may experience a graded difference in the subjective clarity of inner speech compared with healthy individuals.

However, far from showing a uniform relationship, the inner speech varieties showed different dynamics with AVH in our data, which indicates that our participants with SSDs experienced and reported inner speech and AVH as distinct phenomena, and are consistent with the assertion that people with SSDs can accurately identify inner speech. It should be noted that Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore, and Mishara (Reference Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore and Mishara2008) only asked about the experiential features people with SSDs used to make the distinction, but did not attempt to test them. One possibility is that while people with SSDs generally have the ability to differentiate between inner speech and AVH in retrospect, it is more difficult for them to make unequivocal judgments in real-time across multiple occasions. It is also possible that they use other features, such as loudness and clarity of the verbal mentation that are not captured in the present study, to make the separation (Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore, & Mishara, Reference Hoffman, Varanko, Gilmore and Mishara2008). Future research encompassing a larger variety of features will be needed to shed light on this issue.

Inner speech and affect

Finally, we found that all inner speech varieties were positively associated with NA momentarily across both groups, which suggests that emotional distress amplifies inner speech regardless of clinical status. These results extend previous research showing that evaluative and other people inner speech were positively correlated with the levels of anxiety and depression in nonclinical populations (Alderson-Day et al., Reference Alderson-Day, Mitrenga, Wilkinson, McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough2018; McCarthy-Jones & Fernyhough, Reference McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough2011). One speculation is that people were engaged in cognitive processes, such as rumination and mind wandering, which primarily present themselves as inner speech (Alderson-Day & Fernyhough, Reference Alderson-Day and Fernyhough2015a; Perrone-Bertolotti et al., Reference Perrone-Bertolotti, Rapin, Lachaux, Baciu and Loevenbruck2014). Indeed, more dialogic and evaluative inner speech was engaged during induced rumination (Moffatt et al., Reference Moffatt, Mitrenga, Alderson-Day, Moseley and Fernyhough2020). Given the established links between these cognitive processes and negative mood (Goldwin & Behar, Reference Goldwin and Behar2012; Killingsworth & Gilbert, Reference Killingsworth and Gilbert2010), it is perhaps unsurprising that associations between dialogic and evaluative inner speech and NA were found in the present study. On the other hand, as positive inner speech often serves the function of emotion regulation (Alderson-Day et al., Reference Alderson-Day, Mitrenga, Wilkinson, McCarthy-Jones and Fernyhough2018), it is possible that it was engaged as a coping response against NA. However, the significantly weaker association between positive inner speech and NA in people with SSDs compared with the HC participants suggests reduced regulatory effectiveness in people with SSDs (Visser, Esfahlani, Sayama, & Strauss, Reference Visser, Esfahlani, Sayama and Strauss2018), which is consistent with the broader deficits in affect regulation reported in psychosis (O’Driscoll, Laing, & Mason, Reference O’Driscoll, Laing and Mason2014). Future studies employing techniques such as time-lag analysis would help to clarify the directionality and the cause-and-effect relationships between affect and inner speech.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, given the modest sample size, these results should be confirmed in future studies with larger samples, which may allow the detection of milder interaction effects (e.g. group difference in the NA and IS association). Moreover, the PANSS total score of the SSD group indicated they were only ‘mildly ill’ (Leucht et al., Reference Leucht, Kane, Kissling, Hamann, Etschel and Engel2005). Along with their chronicity and outpatient status, it is unclear whether the results would generalize to all SSDs voice-hearers and those with more severe symptoms. Including individuals with SSDs without current AVH and nonclinical voice-hearers would be particularly valuable for establishing whether the distinct inner speech profile is specific to AVH or characterizes SSDs more broadly (Toh, Moseley, & Fernyhough, Reference Toh, Moseley and Fernyhough2022). Second, the use of a single-item ESM measure for each inner speech variety may limit reliability. Although this is a recurring challenge for ESM research (Fritz et al., Reference Fritz, Piccirillo, Cohen, Frumkin, Kirtley, Moeller and Bringmann2024), including multiple items for each inner speech construct may be one way to improve the validity of measuring inner speech experiences through introspection, which remains an accurate tool in understanding mental contents (Corneille & Gawronski, Reference Corneille and Gawronski2024). Third, while participants were explicitly instructed to report on their inner speech, caution should be exercised when interpreting the responses to the ‘other people’ item in voice-hearers, as it taps into the domain of non-self-voices, potentially blurring the boundary with AVH experiences (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, McCarthy-Jones, Chase, Humpston, Melbourne, Kling and Sharma2018). Future studies may wish to modify the VISQ-R for voice-hearing populations or employ methods, such as descriptive experience sampling, which combines ESM with in-depth interviews, to achieve high-fidelity responses (Hurlburt et al., Reference Hurlburt, Heavey, Lapping-Carr, Krumm, Moynihan, Kaneshiro and Kelsey2022; Hurlburt, Heavey, & Kelsey, Reference Hurlburt, Heavey and Kelsey2013).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study found that individuals with SSDs and current AVH experienced more inner speech moments and heightened moment-to-moment levels of inner speech varieties compared with healthy individuals. Several inner speech varieties were positively associated with AVH severity momentarily, and momentary NA moderated the association between evaluative inner speech and AVH, demonstrating the dynamic interactions between inner speech, AVH, and affect. Taken together, these results offer support for the inner speech theory of AVH at the phenomenological level. Our results suggest that evaluative inner speech and negative emotional state may play a central role in the inner speech–AVH relationship. Tailoring interventions with these potential therapeutic targets may pave the way for more effective and personalized treatments for inner speech-based AVH (Smailes et al., Reference Smailes, Alderson-Day, Fernyhough, McCarthy-Jones and Dodgson2015).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants who contributed to the study.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship, the Australian Research Council (grant numbers DP200103288 and DP170103094), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grant numbers APP2004067 and APP1090507), the Daniel Beck Memorial Award for Schizophrenia Research, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Direct Grant, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Small Research Grant, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Postdoctoral Fellowship Scheme, and the Research Grant Council General Research Fund (grant numbers 14601122 and 14605123).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.