Introduction

The MOWAA Archaeology Project is a pioneering research project delivered within a major pre-construction programme. Linked to development of the Museum of West African Art (MOWAA), it involves collaboration between MOWAA, the British Museum, the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM), and delivery partners Cambridge Archaeological Unit and Wessex Archaeology (Pitts Reference Pitts2024). Conducted from 2022–2024, it is the largest archaeology project undertaken in a West African urban context, with sustained development opportunities for early-career archaeologists.

Benin City, once capital of the Benin Kingdom (c. AD 1200–1897), is celebrated for its spectacular bronzes (Digital Benin n.d.; BTCEB 2020) and extensive earthworks (Egharevba Reference Egharevba1960; Roese et al. Reference Roese, Rees and Bondarenko2001; Schepers et al. Reference Schepersin press). The palace and wider city were destroyed in 1897 by the British military and thousands of bronzes looted (Egharevba Reference Egharevba1960). Substantial excavations in the 1960s documented a rich, approximately 3m-deep sequence representing thirteenth/fourteenth century and eighteenth/nineteenth century phases, including palace buildings (Figure 1) (Connah Reference Connah1975).

Figure 1. Wider site context: a) map of MOWAA Campus and excavation zones within Benin City; b) Rainforest Gallery excavations in foreground and Institute building top left (figure by authors).

This project is the first in Benin City in 50 years, focusing on unexcavated sectors of the historic palace complex, previously buried beneath the former Central Hospital and Health Management Board buildings. Survey and evaluation were combined with excavations across two large building plots (Figures 1 & 2). The project is establishing a new absolutely-dated archaeological sequence for the development of one of Africa’s most important precolonial urban centres (Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2005).

Figure 2. Map showing excavation locations (figure by authors).

Method

In advance of construction of the MOWAA Institute and Rainforest Gallery, intrusive and non-intrusive approaches were adopted to investigate and mitigate construction impacts on archaeology (Figure 2). Geophysics (ground penetrating radar), gridded walkovers and geotechnical monitoring were coupled with test-pit evaluation. Larger excavations at the two principal construction sites employed systematic sampling and single-context recording, prioritising areas most at risk and with highest research potential. A watching brief was also undertaken during construction of a new NCMM storage facility. Combining conventional hand-digging with monitored machine excavation, including to remove modern overburden, helped deliver the first major pre-construction excavation in a West Africa urban context, providing a template for further development-led fieldwork (cf. Lavachery et al. Reference Lavachery2005; Folorunso Reference Folorunso2021). Beyond guiding excavations, geophysics is informing wider site understanding alongside historic maps.

Best-practice field methods were fused with knowledge exchange opportunities, including placements in London, Cambridge and Cyprus. Ten early-career Nigerian archaeologists have been employed full-time, with 58 additional fieldwork roles. MOWAA is developing a field team and laboratory at the new Institute, and contribution to this is a key project legacy.

Results and discussion

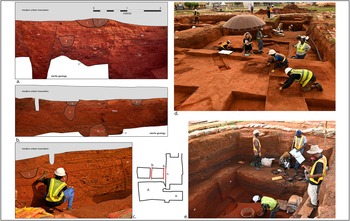

Fieldwork documented a detailed archaeological sequence for this previously unresearched area of Benin City (Figures 3 & 4). Stratified cultural layers, 1.45–1.6m deep, were recorded, penetrated by pits exceeding 3m in depth. The earliest radiocarbon dates, albeit without associated material culture, are first millennium AD, pre-dating the Benin Kingdom (Figure 5). The sequence spans the establishment and use of the palace through to its 1897 destruction, with subsequent colonial and post-colonial uses (including a police barracks, then post-independence hospital and health facilities). Initial radiocarbon dating indicates the main sequence began fourteenth century and features Benin’s ‘high period’ levels (sixteenth–seventeenth centuries), unidentified in previous excavations. Further radiocarbon dating is in progress. All project data are archived with NCMM and MOWAA.

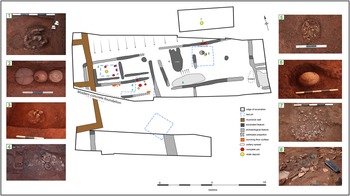

Figure 3. Plan of structural complex (upper levels) excavated in Area 4 highlighting key areas of interest: 1 & 3) moulded chalk (nzu) arrangements; 2) arranged inverted pots; 4) oven feature and associated pottery; 5) cowries in complete pot; 6) inverted pot; 7) chalk spread; 8) pottery spread and bottles (figure by authors).

Figure 4. Stratigraphy in Area 5: structural levels 1–7 (a–c) and work in progress (d–e) (figure by authors).

Figure 5. Calibrated radiocarbon dates (figure by authors).

The project provides the first examination of large sectors of the palace complex, with the Institute and Rainforest Gallery occupying, respectively, the ‘wives’ quarter’ (erie) and a zone of shrines and other palace buildings recorded on nineteenth-century maps. This establishes the most complete architectural sequence for Benin City to date. Walls and related floor surfaces were recorded in the suspected earliest phases at the Rainforest Gallery site (dates pending). Substantial building remains were also recorded in later phases (eighteenth/nineteenth century), and their arrangement on the same axis as earlier buildings indicates significant continuity of urban planning. A building was also recorded in the Institute upper levels, likely part of the ‘wives’ quarter’. Access to this area would have been restricted by a substantial earth wall and timber gate. A large crater, originally 5m deep, dominated this area and may have been the source of material for walls and buildings.

Structural remains, associated features and material culture provide insights into site function and historic lifeways. One of the most extensive building complexes features strong evidence for ritual activity, including arranged upturned pots, cowrie shell caches in pots and moulded chalk (nzu) arrangements (Figure 4). This locality was likely a major palace shrine. A pit feature contained more than 100 gin and other glass bottles, bearing trademarks including Africana, Van Hoytema and Van Marken, mostly nineteenth-century patents. Their deposition alongside giant snailshells and quantities of iron might indicate this was a shrine.

Features and finds provide evidence of artisanal activity, including Benin’s renowned metalworking (Figure 6). This includes a workshop where pits with scorched edges and charcoal-rich fills contained lead slag, likely nineteenth century. Crucible fragments and copper-alloy finds are being studied through metallography and elemental analysis, adding to materials being reviewed from historic excavations. Among the varied find categories (including imported glazed wares, smoking pipes, beads, glass bottles and metal objects; Figure 6), locally produced ceramics dominate with more than 120 000 sherds retrieved. Finds from sealed pits and on occupation surfaces enable the construction of a detailed ceramics sequence, shedding light on cultural development and helping facilitate wider regional studies. Detailed macro- and micro-botanical studies identify varied plant species, including oil palm, pearl millet, cotton and foxtail millet. These, coupled with analysis of faunal remains, pollen and organic residues from ceramics, will provide the first comprehensive picture of environment change and dietary and economic practices in Benin.

Figure 6. Selected material culture: a) metallurgy; b) other finds (figure by authors).

A tangible reminder of colonial histories is the European Cemetery (Figure 1), founded shortly after 1897, now mapped for the first time. Work recording and identifying levels associated with the 1897 burning of the palace and possible post-conquest relandscaping is ongoing. Evidence for early colonial redevelopment was also encountered, including a building complex combining mudbrick and mortar, potentially in the vicinity of the early Governor’s residence. Important further evidence includes a cache of late-colonial-era Nigerian police regalia, near to what became the post-colonial police headquarters.

Conclusion

The MOWAA project has delivered the most extensive, systematic excavations within Benin City. It reveals the most comprehensive archaeological picture to date of Benin City’s history, including the pre-colonial Benin Kingdom, the 1897 destruction, and colonial and post-colonial development. These results give potential for wider understanding of the West African past, relating to urbanism, architecture, artisanal practice, ritual, trade, diet and environment. The project highlights the opportunities for archaeological research and mitigation in advance of construction in Nigeria and West Africa. The research has also been delivered in conjunction with sustained commitment to building capacity in excavation, survey, material analysis and conservation, supporting development of a new world-class research institute.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the NCMM and Edo State Government for providing permissions and authorisation.

Funding statement

The project has been made possible by a major grant from an anonymous donor, managed by the British Museum as part of the African Histories and Heritage Programme.