Recent years have seen an increase in the number of children and young people referred to gender clinics worldwide. Reference Chen, Fuqua and Eugster1–Reference Kennedy, Spinner, Lane, Stynes, Ranieri and Carmichael3 Notably, in the UK, referrals to the national gender clinic increased from 51 children and young people in 2009 to 1715 in 2016, Reference de Graaf, Giovanardi, Zitz and Carmichael4 and further increased to over 2700 in 2019/2020. Reference Cass5 Following the publication of the Cass Review in April 2024, gender services for children and young people were reorganised in the UK and in March 2024 the national gender clinic was closed, to be replaced by regional services. 6 While more recently numbers of referrals have reduced, numbers on the waiting list have risen, resulting in lengthy waiting times. Reference Fox7 In March 2025, it was estimated that there were 6225 children and young people on the gender services waiting list, up from 5560 a year earlier. Reference Fox7 Despite these increasing numbers, understanding of the long-term outcomes for children and young people referred to specialist gender services remains limited. Most research in the field to date has been dominated by small clinic studies where there has been limited systematic data collection undertaken by independently funded and resourced research teams. Reference Stynes, Lane, Pearson, Wright, Ranieri and Masic8 In recent years this has begun to change, with a small number of longitudinal studies being funded in the USA, Reference Olson-Kennedy, Chan, Rosenthal, Hidalgo, Chen and Clark9 Australia Reference Tollit, Pace, Telfer, Hoq, Bryson and Fulkoski10 and Canada. Reference Bauer, Pacaud, Couch, Metzger, Gale and Gotovac11

In the current paper, we report the characteristics of children and young people participating in the Longitudinal Outcomes of Gender Identity in Children (LOGIC) study. Reference Kennedy, Spinner, Lane, Stynes, Ranieri and Carmichael3 The LOGIC study aims to investigate the outcomes of a cohort of 622 children and young people who were referred to the national UK gender clinic by undertaking a comprehensive assessment of outcomes pertaining to gender identity, gender dysphoria, mental health and well-being, quality of life, autism, physical development and health service use. The objective of the LOGIC study is to obtain a multidimensional understanding of this cohort as young people navigate complex life changes such as puberty and social transition, and to explore how such changes relate to gender dysphoria.

Significant limitations have been identified in the comprehensiveness of data collection and reporting regarding the characteristics of children and young people referred to specialist gender services. Reference Taylor, Hall, Langton, Fraser and Hewitt12 It is hoped therefore that the data presented here will contribute to addressing this gap and enhance understanding of the needs of this cohort.

Method

Study design, setting and participants

The LOGIC study is a longitudinal study that follows 622 children and young people referred to the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS), recruited between June 2019 and May 2021 from the waiting list. Before its closure in March 2024, GIDS was a nationally commissioned service covering England, Wales, Northern Ireland and, in part, Scotland and the Republic of Ireland. The service had centres in London and Leeds and outreach clinics across the UK. Children and young people were eligible for inclusion in the study if they had a referral to GIDS accepted when they were aged 14 years or younger, had not had their first appointment with the service, spoke English fluently and resided in the UK or the Republic of Ireland. Families remained eligible to participate even if, after referral, they no longer wished to be seen by the service.

Study recruitment followed a three-step process, which entailed the GIDS administrative team contacting eligible families and obtaining consent for their details to be passed on to the LOGIC research team. Consenting families were then contacted directly by a researcher and provided with detailed information sheets, including age-appropriate versions for their child or young person. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents or caregivers for each child. While the recruitment of parent–child dyads was sought, 57 parents participated without their child or young person and 5 young people participated without their parents. The recruitment process is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10451.

Ethical standards

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the Health Research Authority and London – Hampstead Research Ethics Committee (reference no. 19/LO/0857).

Procedures

Children and young people completed one of two surveys. The child interview, which was administered to those aged 11 years or younger, consisted of age-appropriate questions and measures about gender, as well as the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire. Reference Ravens-Sieberer, Gosch, Rajmil, Erhart, Bruil and Duer13 Children aged 11 years also completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) Reference Goodman14 and the short-form Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (sMFQ). Reference Angold, Costello, Messer and Pickles15 Most child interviews took place in person, with researchers travelling to families’ homes or via video format (in both cases with parental presence), although some children chose instead a telephone conversation or self-completion of an online form via the Qualtrics survey platform.

The young person survey was designed for participants aged 12+ years, and featured a more extensive set of age-appropriate measures in addition to those in the child interview. Specifically, these were the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS), Reference Tennant, Hiller, Fishwick, Platt, Joseph and Weich16 the Youth Self-Report (YSR) Reference Achenbach17 and an itemised version of the DSM-5 criteria for gender dysphoria. 18 Because it was deemed developmentally appropriate, four 11-year-olds completed the young person survey and one 12-year-old completed the child interview.

Parents/caregivers were invited to complete the parent survey, which provided the primary source of sociodemographic data, as well as additional measures about their child. These were the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Reference Achenbach17 the SDQ, the Autism Spectrum Quotient, Reference Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin and Clubley19,Reference Baron-Cohen, Hoekstra, Knickmeyer and Wheelwright20 the DSM-5 Gender Dysphoria measure and the Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS). Reference Byford, Harrington, Torgerson, Kerfoot, Dyer and Harrington21

The young person and parent surveys were completed online via Qualtrics by most of the study participants, although some completed the questionnaires either with the researcher in-person, over the telephone or via a video call or postal questionnaires. Data collected via post, telephone and video call were subsequently entered into Qualtrics by one of the researchers on the LOGIC study.

In line with current co-creation research practices, there were three layers of lived experience guidance within the LOGIC Study: (a) a lived experience co-researcher; (b) an independent steering committee, including both researchers and people with lived experience, who met regularly to discuss study progress; and (c) the study advisory group, which included children, young people and parents participating in the study, who provided advice and guidance on study processes, procedures and interpretation of study findings.

Outcomes

Outcome measures focused on gender identity; gender dysphoria; mental health and well-being; autism diagnoses and traits; quality of life; physical health and well-being; family and peer relationships; and health service usage (see the study protocol Reference Kennedy, Spinner, Lane, Stynes, Ranieri and Carmichael3 ). Due to space constraints, data pertaining to the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (UGDS), Reference Steensma, Kreukels, Jürgensen, Thyen, de Vries, Cohen-Kettenis and Steensma22 Gender Identity Self Stigma (GISS) Scale, Reference Timmins, Rimes and Rahman23 Child Health Utility Index (CHU-9D) Reference Stevens24 and Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) Reference Liebenberg, Ungar and LeBlanc25 can be found in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

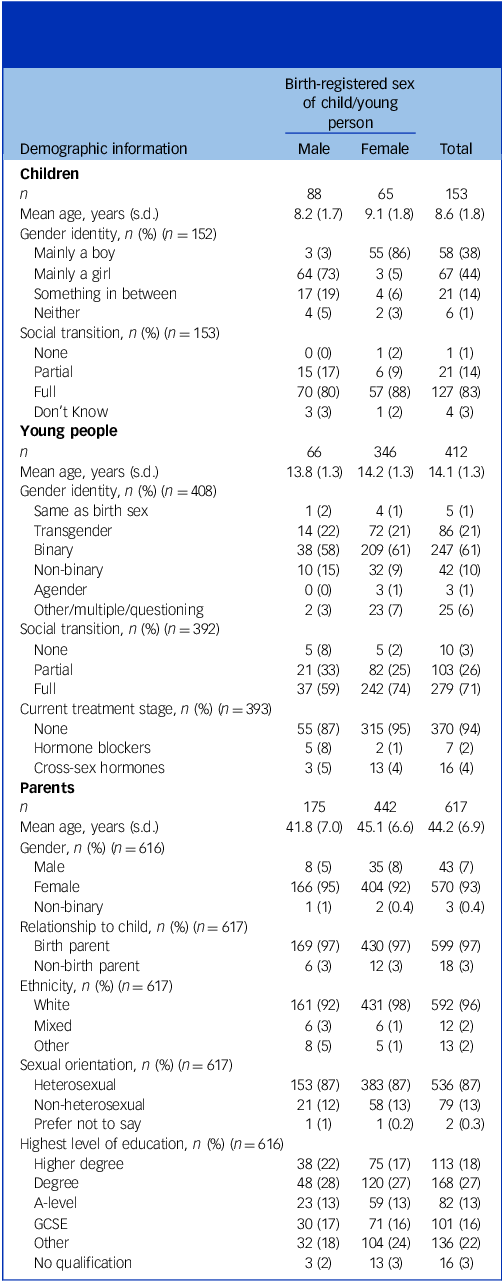

Table 1 Demographic information about children, young people and parent participants. Social transition status of children and young people and endocrine treatment status of young people

GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education.

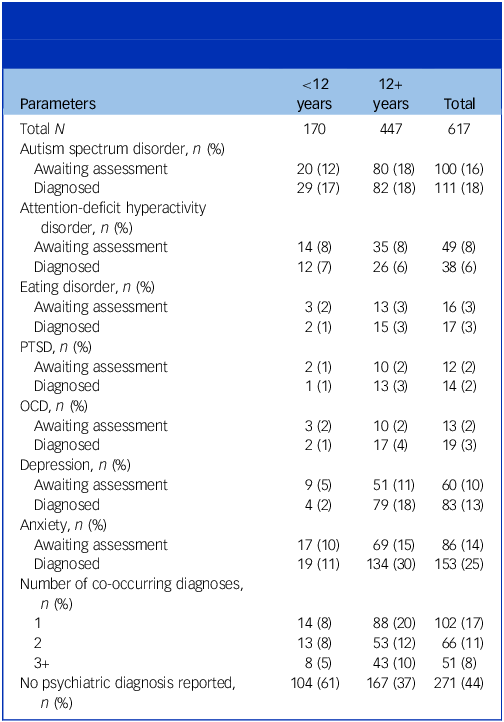

Table 2 Number of parents whose child was awaiting assessment or diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental condition, eating disorder, PTSD, OCD, depression or anxiety

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder.

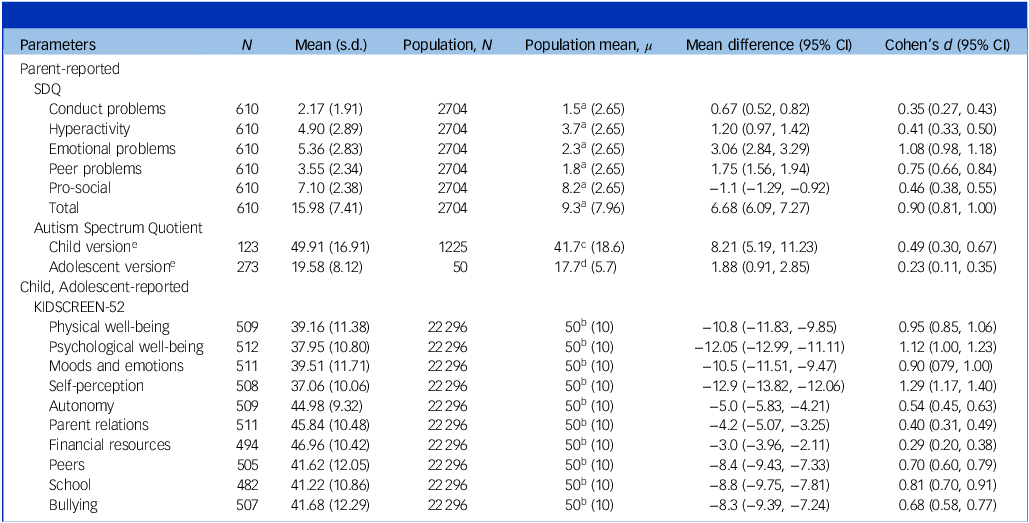

Table 3 Comparisons between our cohort and reference population means for the various measures

SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

a. Population mean obtained from the 2020 Wave of the National Health Service Mental Health of Children and Young People, ages 6–16 years. 27

b. Population mean based on the KIDSCREEN-52 norm of 50. Reference Ravens-Sieberer, Gosch, Rajmil, Erhart, Bruil and Duer13

c. Population mean based on control scores in the child version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient. Reference Auyeung, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and Allison28

d. Population mean based on control scores in the adolescent version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient. Reference Baron-Cohen, Hoekstra, Knickmeyer and Wheelwright20

e. Children and adolescents with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or who were awaiting assessment for ASD, were excluded from this comparison.

Note that all effects were significant (P < 0.001) after correction for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction method; α = 0.0028 (i.e. 0.05/18).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed to summarise the demographics of the cohort. Demographics were presented as means and standard deviations for continuous, symmetric variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. For measures with categorisation bands, the proportion of participants within each band is reported. Likewise, for scales with inbuilt cut-off scores, the proportion of participants who exceed the score threshold is also reported. The agreement between young people who fulfilled the criteria for gender dysphoria based on self-report, versus those who met these criteria based on parent report, was examined using Cohen’s kappa, which can range from 1.00 to −1.00 (with 0 indicating no agreement). Reference Warrens26

Additional statistical analyses included a series of t-tests to compare our cohort and reference population scores on the SDQ, the KIDSCREEN-52 and the Autism Spectrum Quotient. The population mean for the SDQ was drawn from the 2020 wave of the NHS Mental Health of Children and Young People (MHCYP) survey in England, which included responses from 3570 children aged 6–16 years. 27 Normative data for the KIDSCREEN-52 were based on a large-scale survey involving over 20 000 children aged 8–18 years, and their parents, across 13 European countries. Reference Ravens-Sieberer, Gosch, Rajmil, Erhart, Bruil and Duer13 The population mean for the child version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient was taken from a control sample of 1225 UK children aged 4–11 years, Reference Auyeung, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and Allison28 while the reference scores for the adolescent version were based on a control group of 50 UK adolescents aged 10–15 years. Reference Baron-Cohen, Hoekstra, Knickmeyer and Wheelwright20 Independent-samples t-tests were also employed to examine whether Autism Spectrum Quotient scores varied according to birth-registered sex and ASD diagnosis. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust the threshold of significance for multiple comparisons performed in the analyses of these data. The magnitude of these differences was assessed via standardised mean differences (i.e. Cohen’s d).

For continuous measures with partially completed responses (≥80% complete), we either followed guidance provided by the questionnaire manual or imputed missing items using mean imputation to enable calculation of total scores. All analyses were conducted using Stata (version 17).

The sample size was based on analyses planned for a 2-year follow-up. It was initially estimated that 638 participants would be recruited, with the aim of 510 being retained for follow-up after allowing for attrition. Full details are provided in the study protocol. Reference Kennedy, Spinner, Lane, Stynes, Ranieri and Carmichael3

Results

Sample demographics, social transition and endocrine treatment

Demographic data are provided in Table 1. Social transition is also reported here, which refers to the extent to which participants are living as their identified gender. Participants who have partially transitioned may express their gender via their appearance, pronouns or name, whereas those who have fully transitioned will typically express their gender via all three. Endocrine treatment data were also collected for young people.

Sample characteristics

Height and weight data were collected from 382 parents about their child. Given that height and weight are highly sensitive to changes in age, these data were adjusted for differences in sex and age (i.e. body mass index-standardised deviation score (BMI-SDS)). Compared with the population (M = 0, s.d. = 1.0), our sample’s mean BMI-SDS was 0.3 (s.d. = 1.2).

Data were also obtained from 615 parents regarding whether their child had shown signs of puberty; based on these data, 480 children had shown signs of puberty (77 birth-registered males, 403 birth-registered females).

Finally, Table 2 presents information pertaining to neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions.

Gender identity

At the time of recruitment, all children and young people in our cohort were on the waiting list for the gender service. However, during the data collection phase, four parents (0.8%) reported that their child was no longer on the waiting list, either because their child was accepted for assessment (n = 2) or because they decided to leave the waiting list (n = 2). These four participants were excluded from the analyses.

At the time of data acquisition, the cohort had been on the service waiting list for a median of 1 year (interquartile range (IQR) 0.6–1.6). Parents also indicated that the median age of referral to the clinic was 12 years (IQR 10–13 years; birth-registered males 10 years (IQR 7–13 years), birth-registered females 13 years (IQR 11–14) years), and that gender incongruence emerged around the age of 11 years (IQR 5–12 years; birth-registered males 6 years (IQR 3–11 years), birth-registered females 11 years (IQR 8–13 years)).

Health and service use data collected from 607 parents showed that, in the past 6 months, 9 respondents (1.5%) had attended a National Health Service (NHS) gender clinic and 6 (1.0%) had visited a private gender clinic. In addition, 4 respondents (0.7%) had visited an NHS endocrine clinic and one person (0.2%) had attended a private endocrine clinic.

A quarter (25.5%) were in contact with child and adolescent mental health services for gender identity-related reasons.

Gender dysphoria

Based on self-report, 91.2% of young people (374/410; 318 birth-registered females, 56 birth-registered males) met the DSM-5 criteria for gender dysphoria.

Examination of parental responses revealed that 42.1% of children (96/228; 35 birth-registered males, 51 birth-registered females) met these criteria, as well as 64.5% of young people (247/383 participants; 35 birth-registered males, 212 birth-registered females).

Of the young people who fulfilled the criteria based on self-report, 66.8% also met them based on parent report (kappa 0.10, 95% CI 0.038–0.168), suggesting low agreement between self- and parent reports.

Quality of life

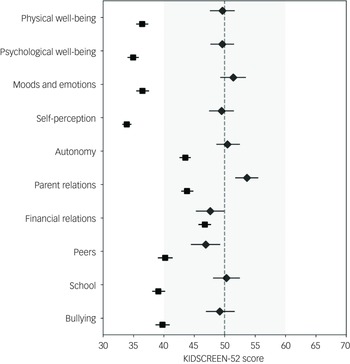

Children’s and young people’s quality of life was examined via self-completed KIDSCREEN-52. Mean subscale scores are plotted in Fig. 1 in relation to the standard range based on population scores (M = 50, s.d. = 10), and show that adolescents fall outside of the standard range on 6 out of 10 subscales, whereas children were within standard population parameters on all subscales.

Fig. 1 Mean scores for each of the KIDSCREEN-52 subscales. KIDSCREEN-52 data represent Rasch-scored t-values, with a normalised population mean of 50 and a standard deviation of ±10, denoted by the dotted line and shaded segment, respectively. Scores outside of the shaded area indicate deviation from population norms. Diamond markers denote child respondents and square markers denote young person respondents. Error bars represent 95% CI.

Self-harm

Self-injurious and suicidal behaviour was measured via the CBCL items 18 and 91.Footnote a For children aged 12 years and younger (n = 224), 29% of parents indicated that their child had engaged in self-harm in the past 6 months and 28% indicated that their child had talked about killing themselves. For adolescents (n = 380), 42% of parents indicted that their child had self-harmed in the past 6 months and 33% indicated that their child had talked about killing themselves.

The corresponding items on the self-reported YSRFootnote b (n = 399) indicated that 46% of adolescents had self-harmed in the past 6 months, and 59% had thought about killing themselves.

Finally, a stand-alone self-harm itemFootnote c employed for children aged 11+ years indicated that 59% of respondents (258/434) had deliberately self-harmed in the past year.

Examination of threshold scores

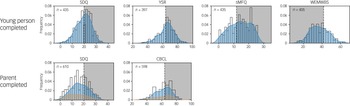

The percentages of respondents who exceeded cut-off thresholds on the various measures are shown in Fig. 2. These data show that 232 (53.3%) young people who completed the SDQ exceeded the cut-off score for ‘very high’ difficulties, and 265 (61.2%) exceeded a score of 12 on the sMFQ, indicating possible depression. In addition, 283 respondents (69.9%) scored below 42 on the WEMWBS, placing them in the bottom 15% of the UK population for mental well-being, and 263 respondents (66.2%) met or exceeded the clinical threshold of 64 on the YSR.

Fig. 2 Distribution of scores completed by young people (top) and parents about their children (bottom). The shaded portions of each scale represent scores that exceed the threshold (note that, except for WEMWBS, higher scores denote poorer functioning). On the parent-completed scales, orange and blue distributions denote children and young people, respectively. SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; YSR, Youth Self-Report; sMFQ, short-form Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; WEMWBS, Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist.

Data provided by parents are also plotted in Fig. 2. Examined separately by age group, this revealed that 158 (35.7%) young people and 44 (26.2%) children were in the ‘very high’ band for the SDQ, characterised by scores of ≥20. Similar trends were also observed on the CBCL, for which 71 out of 158 children (44.9%) met or exceeded the clinical threshold of 64, as well as 225 out of 410 young people (58.0%).

See the supplementary material for full descriptive statistics of each measure, subcomponents and composite scores.

Comparison with population norms

Cross-population comparisons are presented in Table 3, showing that our cohort deviates significantly from normative scores on measures of psychological and behavioural functioning (i.e. SDQ), quality of life (i.e. KIDSCREEN-52) and autism traits (i.e. Autism Spectrum Quotient). However, the differences of greatest magnitude were reflected in the ‘emotional problems’ subscale of the SDQ and the ‘psychological well-being’ and ’self-perception’ subscales of the KIDSCREEN-52.

Conversely, the smallest effects were observed on the ‘conduct problems’ subscale of the SDQ, the ‘financial resources’ subscale of the KIDSCREEN-52 and the adolescent version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient.

Discussion

The current paper describes the health, well-being and quality of life of a cohort of children and young people on the waiting list for the UK national specialist gender service, for whom data were obtained between 2019 and 2021. Many participants were younger than 12 years, thereby providing a unique opportunity to understand gender identity and development as young people move through puberty, adolescence and early adulthood.

Recent trends have shown more birth-registered female than birth-registered male referrals at gender clinics, with the former presenting at an older age. Reference Arnoldussen, Steensma, Popma, van der Miesen, Twisk and de Vries29,Reference Tollit, May, Maloof, Telfer, Chew and Engel30 Here, a similar pattern was noted. While children aged 11 years and younger were relatively balanced in terms of sex ratio, our sample of young people featured more birth-registered females, with an approximate ratio of 5:1. It has been speculated that sex differences in referral age to gender clinics are linked to differences in stigma surrounding gender nonconformity in birth-registered males and females, with less stigma surrounding masculinised behaviours in birth-registered females, and greater visibility of femininised behaviours in younger birth-registered males. Reference de Graaf, Giovanardi, Zitz and Carmichael4 For this reason, it might also be easier for teenage birth-registered females to access care, resulting in an imbalance of referrals at this age and stage.

Sex differences in the onset of puberty represent another potential contributing factor. Because puberty typically occurs earlier in birth-registered females, it is also conceivable that the emergence of physical changes amplifies the incongruence between sex and experienced gender, resulting in more referrals in the final years of childhood – a pattern that continues into adolescence. Aligning with this possibility, our data show that referral age, as well as recalled age at which gender incongruence emerged, was later for birth-registered females than for males, a trend that has also been reported elsewhere. Reference Tollit, May, Maloof, Telfer, Chew and Engel30

A higher percentage (i.e. 19 v. 6%) of male- than female-birth-registered children considered themselves as ‘in between’ a boy and a girl. This distinction remained present, albeit diminished, among adolescents, with 15% of birth-registered males identifying as non-binary versus 9% of birth-registered females. Non-binary individuals are increasingly presenting at gender clinics Reference Taylor, Zalewska, Gates and Millon31 and report their own unique challenges regarding gender identity. Reference Taylor, Zalewska, Gates and Millon31,Reference Chew, Tollit, Poulakis, Zwickl, Cheung and Pang32 As a result, we anticipate that close observance of the trajectories of non-binary children and young people in subsequent waves of the LOGIC study will be important in enhancing understanding of their needs.

Relative to an estimated prevalence of 2.1% among the broader population of children and young people in the UK, Reference Sadler, Vizard, Ford, Goodman, Goodman and McManus33 13% of our cohort had received a diagnosis of depression and a further 10% were awaiting assessment. Similarly, 25% of children and young people were diagnosed with anxiety and 14% were awaiting assessment. Collapsed across those who were diagnosed and awaiting assessment, these prevalence rates of depression and anxiety characterise 23 and 39% of our cohort, respectively. These were observed in addition to a range of other psychiatric diagnoses, with high co-occurrence rates (see Table 2). In addition, 59% of respondents aged 11+ years reported deliberately self-harming within the past year. This proportion aligns with recent findings from the Millennium Cohort Study, in which sexual minority 14-year-old participants were presented with the same item, among whom 54% also reported that they had attempted to harm themselves on purpose within the past year, versus 14% of heterosexual adolescents who endorsed this item. Reference Amos, Manalastas, White, Bos and Patalay34

Mental well-being across the cohort was generally poor, with many children and young people exceeding established thresholds across several indices of emotional well-being, including the clinical cut-off on the CBCL/YSR and validated risk thresholds on both the SDQ and the sMFQ.

However, across multiple indices, children exhibited better overall well-being than adolescents. This was particularly evident based on quality-of-life data obtained via the KIDSCREEN-52: while children were within one standard deviation of the population mean across all subscales, data obtained from adolescents suggested markedly reduced quality of life on six of ten subscales, with self-perception and psychological well-being reflecting the greatest impairment. Likewise, pronounced differences between younger and older children were observed in SDQ and CBCL scores, gender dysphoria and indices of self-harm.

It is conceivable that the differences between age groups are in part driven by the onset of puberty, given the elevated psychological distress that may be promoted by the associated physical changes. Reference McKay, Kennedy, Wright and Young35 While the onset of puberty varies according to individual differences in gender, weight and sex, this typically commences around the age of 11–13 years.

Discrepancies between parents and adolescents were observed on measures for which both parent and self-report data were obtained. Consistently, parent data overestimated the well-being of adolescents in terms of gender dysphoria, self-harm and emotional and behavioural functioning. On the SDQ, for example, parent data indicated that 36% of adolescents exceeded the measure’s maximum threshold, compared with 54% based on self-report. Discrepancies between parents and their children on the SDQ have been widely reported elsewhere, Reference Booth, Moreno-Agostino and Fitzsimons36,Reference Cantwell, Lewinsohn, Rohde and Seeley37 with some studies suggesting that high levels of parent education and low parent psychological distress contribute to parents overestimating their child’s emotional and behavioural well-being, Reference Booth, Moreno-Agostino and Fitzsimons36 and that parent–child agreement is also affected by factors such as the strength of the parent–child relationship Reference Lohaus, Rueth and Vierhaus38 and the gender of the child. Reference Booth, Moreno-Agostino and Fitzsimons36,Reference Gray, Scott, Lawrence and Thomas39 Nonetheless, observing a discrepancy in the current study is perhaps surprising when considering that parent–child dyads tend to show stronger agreement in clinical rather than community settings. Reference Cleridou, Patalay and Martin40

It is also noteworthy that a large proportion of the cohort were either diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (18%) or undergoing assessment for ASD (16%), accounting for 34% of children and young people. There is a growing interest in the intersection of autism and gender diversity, with recent evidence suggesting that around 11% of gender-diverse people are also autistic, Reference Kallitsounaki and Williams41 despite an estimated prevalence of 1–2% in the general population. Reference Baron-Cohen, Scott, Allison, Williams, Bolton and Matthews42 Currently the nature of this intersection is unknown, although one theory is that gender diversity promotes traits and behaviours that resemble autism but which are not caused by autism. Reference Turban43 Elsewhere, it has been suggested that certain aspects of ASD, such as communication difficulties, restricted behaviours and interests, and limited cognitive flexibility, may contribute to the emergence of gender incongruence. Reference George, Stokes, Mazzone and Vitiello44,Reference Strang, Chen, Nelson, Leibowitz, Nahata and Anthony45 While the developmental origins of this intersection remain an open question, it seems reasonable to expect that the answer is likely to be complex and multifaceted. Reference George, Stokes, Mazzone and Vitiello44

While children and adolescents without an autism diagnosis scored lower on the Autism Spectrum Quotient than those who were diagnosed or under assessment, these participants also exceeded control group scores obtained elsewhere. Reference Baron-Cohen, Hoekstra, Knickmeyer and Wheelwright20,Reference Auyeung, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and Allison28 In addition, while the effect sizes of these differences were small for adolescents and small to medium for children, these data provide further evidence for the intersection of autism and gender identity, which will be explored throughout the LOGIC study’s subsequent time points. It is also worth noting that the consistently observed sex difference in Autism Spectrum Quotient scores among the general population – with males typically scoring higher than females Reference Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin and Clubley19,Reference Baron-Cohen, Hoekstra, Knickmeyer and Wheelwright20,Reference Auyeung, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and Allison28 – was not found in our sample.

At the time of data collection, our cohort had been on the waiting list for 1.2 years on average, and almost all had either fully (406 (74%)) or partially (124 (33%)) socially transitioned. Less than 1% had received medical intervention in the form of hormone blockers and/or cross-sex hormones. Qualitative work with the same cohort highlights the fact that, for some young people, puberty is experienced as a ‘ticking time-bomb’. Reference McKay, Kennedy, Wright and Young35 Given recent policy changes in the UK, such as the indefinite ban on the prescription of puberty blockers for under-18s with gender dysphoria, Reference Dyer46 as well as the closure of the national specialist clinic in 2024 and long waiting list times, it is likely that the onset and subsequent progression of puberty for this cohort will pose significant challenges for clinicians, families and young people themselves to navigate.

Our sample represented only 25% of those eligible for study participation. While this level of recruitment is not atypical in studies involving children and adolescents referred to clinical services, Reference Sayal, Wyatt, Partlett, Ewart, Bhardwaj and Dubicka47 it nonetheless represents a limitation because the relationship between the propensity to participate and the variables measured is unknown and may be meaningful. As is well documented, a range of social and socioeconomic factors can influence both healthcare utilisation and the likelihood of participation in research studies. 48 Conclusions drawn from these data must therefore be considered with this in mind.

The use of a range of measures that are also employed in UK population cohort studies and surveys represents a key strength of the LOGIC study. Uniquely, this offers scope for cross-cohort comparisons, thus enabling contextualisation of the data presented here, as well as across subsequent waves of data collection. Importantly, the LOGIC study is also well placed to observe and monitor changes in psychosocial characteristics as puberty progresses in this cohort. From the outset, the study committed to following participants regardless of their engagement with specialist gender services – including those who remained on the waiting list, those who chose to leave it and those who pursued private care. This approach ensures that, despite the recent reorganisation of gender services in the UK, the study continues to generate unique and important data regarding trajectories and outcomes for young people. We anticipate that the findings from subsequent waves of data collection will be valuable in informing service development and clinical practice to better meet the needs of children, young people and their families.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10451

Data availability

The data for the Longitudinal Outcomes of Gender Identity in Children (LOGIC) study are not publicly available. Reasonable requests for the de-identified data will be reviewed by both the LOGIC Steering Committee and the Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) group, and will be granted at the discretion of both groups. Requests for access to the data must be submitted via email to the corresponding author, with detailed proposals of how the data will be used. If data access is approved, data requesters will be required to sign a data access agreement and to confirm that the data will be used only for the agreed purpose for which access was granted.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children, young people and families in the PPI group, and the members of the Study Steering Committee, for valuable discussions on the study design and conduct, and for feedback on the interpretation of the findings presented in this paper. We thank all the families who took part in the study for their commitment, support and generosity in contributing to the study. We also thank the late Professor Michael King, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, study co-investigator, who made key contributions to the study design and conduct.

Author contributions

E.K. and the late M.K. (see above) conceived the study, with the former serving as study lead and chief investigator; together with R.S., G.B., P.C., S.B.-C., T.W., R.O. and R.M.H., they successfully obtained funding for the LOGIC study from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). K.M., A.G.-M., C.H. and C.L. worked as postdoctoral researchers on the study and were responsible for participant recruitment and acquisition of data. A.G.-M., C.H. and C.L. were responsible for the transformation of data that were collected. V.V. and R.M.H. analysed the data, which were checked and verified by R.O., M.C.F. and A.G.-M. C.A. provided guidance on the analysis of the Autism Spectrum Quotient data, R.M.H. provided guidance on the analysis and description of health economics data and R.O. ensured adherence to the statistical analyses outlined in the study protocol and the statistical analysis plan. T.W. contributed as a co-investigator with academic and lived experience expertise. E.K. and M.C.F. drafted the original manuscript. All authors critically reviewed drafts of the paper and approved its submission. In addition, all authors had full access to all data in the study, had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was funded by the NIHR Health and Social Care Delivery Research (grant reference no. 17/51/19). The funder had no role in considering the study design, or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report or decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of interest

All authors declare support from the NIHR. M.C.F. and E.K. are supported on a related study funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant reference no. ES/W000946/1).

Transparency declaration

E.K. affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies have been disclosed.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.