Introduction

Historical scholarship on the ‘new imperialism’ of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has placed cotton at the centre of European (and Japanese) colonial expansion across Africa and Asia.Footnote 1 Rural peripheries were violently and purposefully drawn into global textile value chains, enriching the industrializing West, impoverishing the subjugated producers of the raw material, and undermining local systems of textile production and exchange. According to Isaacman and Roberts, ‘since cotton textile industries were central to metropolitan economies, it is not surprising that the new tropical colonies should be made to serve the interests of the metropolitan economy … by providing secure sources of raw cotton for metropolitan mills and by serving as protected markets for the sale of metropolitan commodities, especially textiles’.Footnote 2 Meanwhile, Beckert posits that ‘cotton production for export typically produced a quagmire of poverty, debt, and underdevelopment well into the twentieth century’.Footnote 3

In the late nineteenth century, sub-Saharan Africa became the ‘latest cotton frontier’, after the abolition of slavery in the southern United States and disappointing efforts to increase cotton supplies from British India.Footnote 4 Extant research on the social, political, and environmental histories of cotton growing in colonial Africa is impressive, covering dozens of cases across West, Central, Eastern and Southern Africa.Footnote 5 Key themes include failed policy implementation; the mismatch between colonial designs and local economic, social, and environmental conditions; and the coercive outcomes of colonial projects. The resistance, evasion, and indifference of African producers in the face of colonial demands are also well-elaborated. There is also a sizeable literature on the market power of African textile consumers and the persistence of local textile manufacturing.Footnote 6 Indeed, the cotton–textile nexus is among the most well-researched cases of economic imperialism in colonial Africa.

But how coherent was the colonial pursuit of cotton in Africa? The literature often assumes that colonizers were united, purposeful, and persistent in their aim to achieve a stable and cheap supply of a crucial raw material, and a secure market for expanding metropolitan textile industries. Relatedly, it is assumed that these aims were translated into policies and practices on the ground. This could, then, result in two outcomes. In some cases, the colonial cotton push failed, and African interests prevailed, either because African producers found a different source of income that was more lucrative and favourable to their interests, or because local textile sectors proved more resilient than colonizers had anticipated. In other cases, European colonizers prevailed, as colonial cotton projects succeeded, but only through tremendous force and violence. In the words of Isaacman and Roberts, ‘left to themselves Africans would probably not cultivate cotton for export’, and ‘cotton was not only the premier colonial crop, it was the premier forced crop’.Footnote 7

These generalizations echo the idea, triumphantly touted by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century colonial cotton propagandists, that there was a coherent ‘metropolitan blueprint’ which merely needed to be implemented on the ground, through a concerted and united effort by textile industrialists and traders, the metropolitan colonial office and colonial administrator. However, did such an encompassing imperial cotton consensus ever emerge? Did it drive colonial policies in Africa? And can it explain the realities of African cotton production and trade across time and space?

Global historians have recently advanced the study of expanding ‘commodity frontiers’ in the age of new imperialism and beyond.Footnote 8 Using the case of cotton, I argue that to fully understand outcomes along these frontiers, they must grapple with the contradictions and ambiguities that emerge between rhetoric in the European metropoles and actual policies in the colonies. Historians of empire have long shown that manufacturing interests never truly controlled colonial policy. Cain and Hopkins, for example, have argued that ‘[British] manufacturing interests made more noise than headway’, and that British colonial officials in Africa ‘showed little inclination to favour manufacturing interests’.Footnote 9 Indeed, even as colonial efforts to boost cotton in British, French, and Portuguese Africa in the interwar era, metropolitan industrialists, especially in the most vibrant economic sectors, showed a growing apathy, even antipathy, towards the colonies.Footnote 10 Thus, the notion that simple templates of ‘economic imperialism’ were translated in a straightforward manner into colonial policy is untenable. These insights by imperial historians deserve closer consideration in the field of global history.Footnote 11 My intervention also resonates with critiques from economic historians that the ‘new history of capitalism’ unduly inflates the importance and effectiveness of purposeful state-led coercion for raw cotton extraction and textile industrialization.Footnote 12

Further, the article fills a methodological void. Limited engagement with available quantitative evidence – some published, some requiring more intensive archival work – has constrained comparative analysis. Recent work has begun to show the potential of comparative and quantitative analysis to move beyond broad generalizations about the links between cotton, capitalism, and empire. So far, the focus has been on the primacy of local conditions to explain the uneven decline of textile manufacturing and the adoption of cotton in colonial Africa.Footnote 13 None of these studies, however, explicitly questions the nature of the imperial policies to which colonized peoples responded.

My approach involves confronting three related but distinct objects of study: imperial rhetoric, the realities of cotton production and trade in Africa, and the nature of colonial policy. First, I show that the metropolitan rhetoric of cotton imperialism has deep roots, but waxed and waned with fluctuations in cotton prices. Second, I quantify cotton production and trade in Africa over the twentieth century by charting total production, spatial patterns on the empire- and colony-level, and the share of raw cotton and textiles trade between selected (former) colonies and metropoles. I show that these outcomes were often at odds with the stated aims of cotton imperialists. Third, I address the nature of cotton policy in three pivotal cases. I explain why East Africa become a major cotton exporter – with India as its prime destination – even though British metropolitan hopes were pinned on Nigeria. I also address why the Belgians, French, and Portuguese developed coercive colonial cotton schemes in the interwar period, despite limited interest and involvement of metropolitan industries. Finally, I address the remarkable expansion of cotton in Francophone West Africa after independence and argue that while the persistent French efforts to turn its African colonies into major cotton exporters was underpinned by the logic of cotton (neo)imperialism, outcomes were again not consistent with this logic.

The rhetoric of cotton imperialism

For the purposes of this analysis, I define cotton imperialism as the use of instruments linked to colonialism (such as coercion, taxation, tariffs, and propaganda) to increase the trade of raw cotton and manufactured textiles between metropole and colony to benefit the metropolitan textile industry. The term was coined by Johnson in the context of West Africa, to describe a policy strategy propagated in 1904 by Frederick Lugard, then high commissioner of the Northern Nigerian Protectorate, who argued that ‘a better class of English cloth than that now imported is required, which will supersede the native, and so bring the raw cotton on to the market. The industries of spinning thread, weaving and dyeing afford … occupation to many thousands who may possibly become additional producers of raw cotton.’Footnote 14

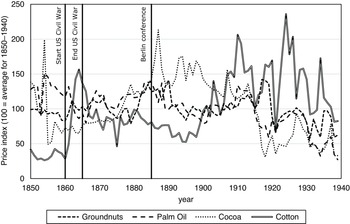

Lugard might have been the first colonial official to elevate this set of interlinked goals to an explicit policy, but the idea has earlier roots.Footnote 15 The belief in the double benefit of African farmers growing cotton for export was especially strong and influential in Britain, with its large textile industry (see Figure 1), but was also visible among French, Portuguese, and German businessmen and officials – especially in times where raw cotton prices were high.Footnote 16 Already in 1817, Senegal’s governor Julien Schmalz argued that ‘before long we can procure considerable quantity for our textile manufacturers’, adding that raw cotton could be exchanged for French textiles and other imports.Footnote 17 Almost a century later, one French analyst was even more straightforward: ‘our colonies supplying raw cotton to the French cotton industry, the French industry supplying our colonies with cotton textiles: these are the two sides of the solution to all present and future crises [in the textile sector]’.Footnote 18

Figure 1. Industrial consumption of raw cotton in European nations active as colonizers in Africa, 1800–2000.

Notes: Spain is not shown, given its marginal role in Africa. Peak consumption years for each of the countries are: Belgium, 1913; United Kingdom, 1913; Italy, 1915 (and 1991), Germany, 1927; France, 1930; Portugal, 1990.

Source: Brian Mitchell, International Historical Statistics (Palgrave, 2013), accessed May 2023, https://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1057/978-1-137-30568-8.

Placing cotton at the heart of the colonial project in Africa made sense not only in European colonial circles at the time, but also more recently among scholars of the topic. Isaacman and Roberts maintain that ‘the centrality of cotton to European interests in Africa in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has not been adequately appreciated’.Footnote 19 According to Beckert, ‘cotton and colonial expansion went hand in hand’.Footnote 20 This perceived centrality of cotton in colonial strategies in Africa and beyond not just derives from its simple logic, but also from the profound significance of the raw material for Europe’s industrial economies. Mass production of textiles had been a key driving force of the Industrial Revolution (see Figure 1).

Supplies were obtained entirely from outside Europe’s industrializing nations, as most of Europe is unsuitable for cotton cultivation. Europe’s most important cotton supplier, by far, was the United States, where cotton was grown in rapidly expanding quantities on southern plantations using slave labour and, during reconstruction after the Civil War, mostly by black sharecroppers.Footnote 21 By the first decade of the twentieth century, the global market share of the United States still stood at well over 50 per cent, followed at a distance by India and Egypt.Footnote 22 That said, cotton was grown in many different places across the world, and in a large gradient of qualities, from short-staple varieties prevalent in India, to the ‘middling’ upland varieties in the American South, to longer-staple varieties in Egypt and the West Indies. This created a layered market, with the machines of Lancashire requiring middling and long-staple cottons, while Japanese manufacturers, for example, mixed in shorter-staple varieties.Footnote 23

European interest in generating cotton supplies from sub-Saharan Africa goes back to at least the late seventeenth century, when traders experimented with slave-grown cotton in coastal West Africa. Such attempts were catalysed by American independence. In 1787, for example, ‘seventeen Manchester textile firms pushed for experiments in cotton production on the Gold Coast and along the Gambia’.Footnote 24 Another impetus was the British abolition of the slave trade. The idea that Africans would cultivate cotton in exchange for textiles from Europe resonated with the view that Africans should take part in ‘legitimate commerce’ to replace the ‘illegitimate’ slave trades. In 1808, the abolitionist African Institution identified Sierra Leone as a potential source of cotton in case ‘circumstances arise to interrupt our commercial relations with America’.Footnote 25

In subsequent decades, British merchants, textile manufacturers, and abolitionists further stepped up their case for West African cotton exports.Footnote 26 Capturing the high expectations, James Mann, in his authoritative The Cotton Trade of Great Britain (1860), argued that ‘there is no question but that Africa is the most hopeful source of future supply’.Footnote 27 Watts, secretary of the Manchester Cotton Supply Association, established in 1857 to diversify the sources of cotton supplying Lancashire, maintained that ‘cotton will yet come in abundance from Africa, there are immense districts that could supply all that Lancashire requires’.Footnote 28 Portuguese and French cotton promotors similarly aspired to export cotton from Africa, and engaged in numerous attempts to entice planters to grow the crop in Angola and Mozambique, and Senegal respectively.Footnote 29 Interest in generating cotton from Africa peaked during the United States Civil War (1861–65), which caused a severe disruption of cotton supplies and spiking prices (see Figure 2). Cotton supply recovered swiftly after this war-induced ‘cotton famine’. As prices reverted back to pre-war levels, European interest in Africa as an alternative source of supply waned.Footnote 30 In Portuguese Africa, large tracts of land devoted to cotton were abandoned in the early 1870s, and exports dropped.Footnote 31 The memory of the cotton famine, however, came to be frequently invoked at times when cotton prices again rose or circumstances threatened supply.

Figure 2. African terms of trade for cotton and other major export commodities, 1850–1940.

Sources: Author’s calculation. Data from Ewout Frankema, Jeffrey Williamson, and Pieter Woltjer, ‘An Economic Rationale for the West African Scramble? The Commercial Transition and the Commodity Price Boom of 1835–1885’, Journal of Economic History 78, no. 1 (2018): 231–67.

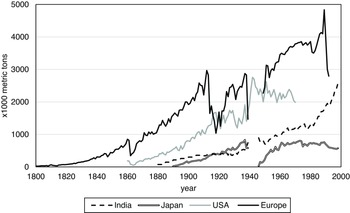

The chronology is different for Africa’s perceived potential as a textile market – the flipside of the cotton imperialism coin. While cotton supply had stabilized by the early 1870s, global textile markets were depressed during the ‘long depression’ (1873–96). From the 1860s onwards, European manufacturers faced competition from an expanding textile sector in the United States, followed by India, and Japan (see Figure 3). Competition for markets within Europe also increased. All of Europe’s textile industries were still on the rise at this time, with the Italian and German industries growing particularly fast (see Figure 1). These conditions fostered a competitive search for new markets, and Africa was perceived to harbour ample potential. European traders had a long-standing presence across West Africa since the eighteenth century, as traders of Indian and later European textiles.Footnote 32 By the final quarter of the nineteenth century, European, and especially British, merchants were firmly entrenched in the region. In the context of the long depression, they called for European governments and industries to step up their commitments in Africa. Speaking to the Manchester Chamber of Commerce in 1884, for example, Henry Morton Stanley speculated that ‘if every female inhabitant of the vast [Congo] basin bought only one Sunday dress made of Lancashire cloth an export of 300 million yards would result’.Footnote 33 This implied that the Congo alone could absorb about a tenth of Britain’s total annual textile production at the time, and about 7 per cent of the maximum annual output Britain would ever generate – an enticing prospect.Footnote 34

Figure 3. Industrial consumption of raw cotton in Europe and emerging textile producers, 1800–2000.

Notes: Indian production pertains to mechanized production. India’s large handicraft production, which was declining in the nineteenth century, is not taken into consideration.

Source: Mitchell, International Historical Statistics; India before 1909 from Michael Twomey, ‘Employment in Nineteenth Century Indian Textiles’, Explorations in Economic History 20, no. 3 (1983): 37–57, 46.

A case can thus be made that obtaining privileged access to African textile consumers served as one justification for the ‘Scramble’. Meanwhile, acquiring new potential sources of raw cotton was not in front of the Scramblers’ minds, given that cotton prices, quite unlike those of other commodities, were low and stable at the time (see Figure 2). Interest in cotton reemerged only after European colonial powers had effectively occupied most of Africa. This renewed interest was spurred by supply disruptions and a substantial increase of cotton prices between circa 1895 and 1910, as a consequence of speculation in the cotton market, resurging global demand for the crop, and the spread of the boll weevil in cotton fields of the US South.Footnote 35 The fact that European nations had now acquired large tropical territories, many which as of yet produced little in terms of export value and were often dependent on metropolitan loans, provided an additional argument to pursue cotton imperialism. This means that we should be careful not to interpret Beckert’s assertion that ‘cotton and colonial expansion went hand in hand’ to mean that cotton extraction was a driver of colonial occupation itself.Footnote 36 The causality rather went the other direction.Footnote 37

In this context, societies were formed across Europe to stimulate colonial cotton production and export. They were spearheaded by cotton traders and manufacturers, but also found moral support and financial backing from their governments. They advocated for research, extension, and the establishment of ginneries, which were crucial because the process of seed removal sheds about two-thirds of the weight before transportation. In 1896, the Kolonialwirtschaftliches Komitee (KWK) was founded in Germany by Karl Supf, a textile industrialist, driven by the conviction that it was ‘the national duty of industry to develop our colonies as a raw material and market area for the motherland’.Footnote 38 The KWK was not solely devoted to promoting cotton but, as pointed out by Maier, ‘the obsession of many German policy makers and businessmen with dependency on American cotton cannot be overemphasized’.Footnote 39 Sunseri goes as far as to argue that ‘the desire for German sources of raw cotton was the single dominant theme in German colonial policy’.Footnote 40

In 1902, Britain followed with the establishment of the British Cotton Growing Association (BCGA). The expectations put forward by a new generation of cotton propagandists were as lyrical (and inflated) as they had been several decades before. J. Arthur Hutton, one of the BCGA founders, for example, posited in 1904 that ‘Lancashire’s future salvation lies mainly in West Africa.’Footnote 41 In 1907, a BCGA report described Kano, in Northern Nigeria, as ‘the Mecca of the Lancashire spinning trade’.Footnote 42 Branding itself as a private, semi-philanthropic organization (the echoes of ‘legitimate commerce’ were clearly discernible), the BCGA had some powerful sympathizers in metropolitan and colonial circles, such as Lugard (see above) and Winston Churchill during his time as undersecretary for the colonies (1905–8),Footnote 43 after whom one of Nigeria’s first steam-powered cotton ginneries was named.Footnote 44 The BCGA also found a promotor in Edmund Morel, prominent journalist and campaigner against the abuses involved in rubber extraction from Leopold II’s Congo Free State.Footnote 45

In 1903, French textile industrialists established the Association Cotonnière Coloniale (ACC), and their Italian counterparts the Societa per la Coltivatione del Cotone nella Colonia Eritrea. Belgian interests only coalesced around a joint colonial cotton venture in 1920, when the Compagnie Cotonière Congolaise (CotonCo) was founded. However, as early as 1903, the Association Cotonnière de Belgique (established in 1899) had called upon the Congo Free State to stimulate cotton.Footnote 46 Portuguese efforts to grow cotton in Africa had already been extensive in the nineteenth century – albeit erratic and unsuccessful.Footnote 47 While Portugal’s textile industry was comparatively small, it had been the fastest growing in Europe between 1880 and 1900, more than doubling its output. Portugal’s colonial cotton association, the Sociedade Fomentadora da Cultura do Algodão Colonial, was formed in 1906.Footnote 48

It is probably no exaggeration to posit, then, that upon the effective European occupation of Africa, no other single agricultural commodity received as much rhetorical endorsement and dedicated institutional support as cotton. The logic of cotton imperialism provided a straightforward colonial ‘business case’, revolved around a major industry, had powerful economic and political backers, and could invoke past and current supply scares. But how and to what extent did it actually shape subsequent colonial policies and practices in Africa?

The production and trade of cotton in (post-)colonial Africa

Establishing if any meaningful quantities of cotton were exported from colonial Africa is a logical first step to investigate the impact ‘on the ground’ of European cotton imperialism. No serious attempts appear to have been undertaken yet to comprehensively chart the evolution of African cotton production and export under colonial rule. Most scholars assert that, on the whole, cotton imperialism in Africa was a failure. According to Ross, no more than a ‘trickle’ of cotton came from the African colonies.Footnote 49 Porter goes as far as to posit that ‘never was so much misplaced effort devoted to an enterprise as the production of cotton in sub-Saharan colonial Africa. The photosynthetic difference and cotton’s wide production in large, better-suited areas doomed from the start the metropolitan dream of developing a competitive cotton industry [sic] in tropical Africa.’Footnote 50

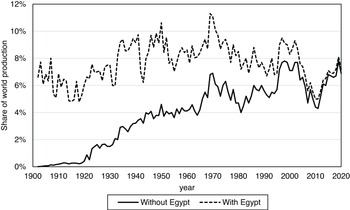

Cotton was certainly a failure in light of cotton propagandists’ inflated expectations, but the idea that colonial Africa hardly exported any cotton at all needs to be qualified. Figure 4 shows that the African share (without Egypt) of total global cotton production rose from almost nil as late as 1920 to over 4 per cent by 1960, when most African colonies achieved their independence.

Figure 4. African share of recorded global cotton production, 1900–2020.

Notes: There are minor discrepancies between the different sources that underpin the series. Whenever they overlap, I took the average of the available estimates.

Sources: Empire Cotton Growing Review (1902–63); League of Nations, Statistical Yearbooks (1935–42); Institut International d’Agriculture, Annuaire international de statistique agricole (1934–40); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Yearbook of Food and Agricultural Statistics (1940–54); Food and Agriculture Organization, Production Yearbook (1955–63); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, ‘FAOSTAT’ (1961–2020), accessed May 2023, https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/.

A major caveat of official production statistics is that expansion may have resulted primarily from diversion from (unrecorded) local markets to (recorded) export markets, rather than from an actual expansion of cultivation. In the early colonial period, in particular, a sizeable amount of cotton production went unobserved, because it was not traded intercontinentally and took place outside the purview of colonial data collectors. Such cotton was absorbed by pre-colonial local handicraft industries, especially in West Africa, Kano in Northern Nigeria in particular.Footnote 51 Some scholars have insisted that the absorption of raw cotton by Africa’s textile sectors persisted well into the colonial era. Roberts, for example, argued that the French Soudan (Mali), ‘produced vast amounts of cotton’,Footnote 52 and that ‘the failure of colonial cotton development in the French Soudan is directly attributable to the persistence of the precolonial handicraft textile industry’.Footnote 53 However, his own statistics from the interwar era suggest that only a small absolute amount of cotton was absorbed by local handicraft producers.Footnote 54 Meanwhile, in Kano, Northern Nigeria, robust and persistent handicraft production is well-documented.Footnote 55 In the mid-1920s, British economist William Allen McPhee could still write, echoing Lugard twenty years earlier, that the British colonizers faced the problem of how to ‘divert the supply of cotton from the Nigerian hand-looms to the power-looms of Lancashire’.Footnote 56

Although precise figures are unavailable, numerous contemporary observers attempted to get at least a sense of the order of magnitude of unrecorded production for domestic industries. In the 1930s, and again in the early 1960s, the output of the domestic textile industry in Northern Nigeria was estimated at 50 million square yards.Footnote 57 Given that Northern Nigeria had, by far, Africa’s largest textile industry, we might assume that at most 100 million square metres (about 120 million square yards) of cotton cloth were produced on handlooms annually in the entire continent. If we assume, conservatively, that for each square metre half a kilogram of cotton lint was required (compared to the 0.25 kilogram per metre typical of European factory-produced clothFootnote 58 ), and that all textiles were woven with locally produced cotton lint (while in reality a substantial share of the yarn was importedFootnote 59 ), the annual locally consumed – and therefore unrecorded – raw cotton output in sub-Saharan Africa was 50,000 metric tons of cotton lint (or some 150,000 tons of seed cotton). This estimation lines up well with direct estimates of cotton production for local consumption. Circa 1920, a British cotton expert touring Nigeria reported estimates of local consumption of up to 150,000 bales, the equivalent of some 27,000 metric tons of lint.Footnote 60 In 1948, European observers estimated variously that Nigeria’s textile producers processed 10,000 to 30,000 metric tons of cotton lint annually.Footnote 61

How substantial are these amounts in a global perspective and in relation to exports from colonial Africa? While the size of their industry was far from negligible, Africa’s pre-industrial weavers consumed only a fraction of cotton used by their European steam-powered counterparts. In 1913, textile factories in the United Kingdom alone churned out over 3 billion metres of tissue, consuming close to a million tons of cotton lint. This was at least twenty times more than my estimate of 50,000 metric tons consumed by all of Africa’s industries combined. By the mid-1920s, the official – that is, exported – African recorded production statistics first exceeded 50,000 tons of lint, suggesting that at least half of all cotton was exported. At this time, Africa’s recorded share of world cotton output stood at a mere 1.5 per cent, as Figure 4 shows. By the late 1940s, Africa (except Egypt) exported over 200,000 metric tons annually (four times more than its own textile industries had ever consumed), a volume that would rise to over 400,000 metric tons by the late 1950s (eight times more). Domestic consumption of cotton in Africa, then, was quantitatively relevant in the first quarter of the twentieth century, probably contributing substantially to suppressing export volumes, as suggested by McPhee. But domestic cotton consumption was small in a global perspective, and from the second quarter of the twentieth century onwards it was dwarfed by expanding export volumes.

Of course, the observed gains in volume do not speak to the question if the output realized was proportionate to the amount of resources invested – not even to speak of the human costs. That said, the above calculations demonstrate that Africa’s aggregate cotton output must have expanded substantially in the colonial era, in absolute terms, but also in terms of its share in global output.Footnote 62 To put this in a broader perspective of Africa’s agricultural exports: in 1957 cotton accounted for 8.6 per cent of export value from sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia, and Botswana); less than coffee (13.4%), copper (13.3%), cocoa (10.3%), and peanuts (8.7%), but more than palm products, diamonds, timber, tobacco, and rubber.Footnote 63 In a global perspective, sub-Saharan Africa’s contribution, at less than 5 per cent in any given year, remained fairly marginal. However, if we look at specific varieties and territories, Africa’s contribution was somewhat more substantial. Uganda’s global share in the market for long staple cotton (1⅛ to 1½ inches), for example, was 10.1 per cent in 1954–56.Footnote 64

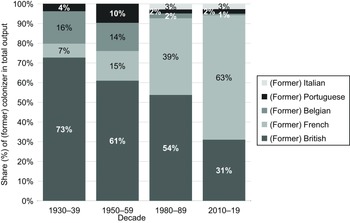

Is this evidence of at least some tangible effect – modest as it might be – of cotton imperialism in Africa? To get a step closer to answering this question, we can break down the export statistics by colonizer and territory. Figure 5 gives cotton output shares by colonizer. A first pattern that arises is that the initial expansion of output was mainly realized in British-controlled territories, and to a lesser extent those of Belgium and Portugal, while over the century, and especially after independence, the (former) French colonies began to dominate. Later, we will return to the role of France in these post-colonial developments, and the extent to which we can still analyse them fruitfully in the framework of cotton imperialism. During the colonial era itself, Britain, seems to have been by far the most successful in generating cotton from its African dependencies. Were the British also trying hardest?

Figure 5. Cotton output share by (former) colonizer (excl. North Africa).

Source: Michiel de Haas, ‘The Failure of Cotton Imperialism in Africa: Seasonal Constraints and Contrasting Outcomes in French West Africa and British Uganda’, Journal of Economic History 81, no. 4 (2021): 1098–136, online appendix (1930–39 and 1950–59); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, ‘FAOSTAT’ (1980–89 and 2010–19).

In 1906, a French cotton promotor indeed complained that the BCGA was much better capitalized than the ACC. However, the actual expenditures of both organizations in that year were similarly modest (c. 8,000 pounds sterling).Footnote 65 During the first two decades of its existence, the BCGA failed to meaningfully increase empire cotton production (export from British Africa stagnated at around 50,000 bales, or 0.25 per cent of recorded world production). In response, the British government installed a committee in 1917 to investigate new ways to achieve output gains.Footnote 66 In 1921, the Empire Cotton Growing Corporation (ECGC), was established, paid partly through a government grant, and partly through mandatory levies by British textile manufacturers. The ECGC aimed to revitalize cotton cultivation in the colonies, mainly through research and training of experts to support the work of colonial agricultural departments.Footnote 67 This move demoted the BCGA to a commercial player, concerned mainly with ginning and marketing. A key reason to renew the push for empire cotton was a widespread fear among industrialists and government officials about rising absorption by the American textile industry of its domestic cotton harvest, which had risen from 24 per cent before the Civil War, to 36 per cent in 1910–11, and a peak of 61 per cent in 1922–23.Footnote 68 One cotton promotor spoke in 1925 of ‘a crisis [confronting the Lancashire industry] of which the gravity can only be compared with the cotton famine brought about by the American Civil War’.Footnote 69

A belief in cotton imperialism was clearly still alive in Britain at the time. During the first general meeting of the ECGC in February 1921, Lord Derby, president of the BCGA, argued that both the BCGA and the ECGC ‘had recognized the same thing – namely, that it was absolutely essential that the greatest industry … should have cheap material. It was obvious that in America there was a growing demand and … a lessening production, and that they must look for a further field for the supply of their raw material. Where better can we look than in our own Dominions and dependencies?’ This, he argued, was worth the financial support of government which would, in return receive ‘a good reward in employment in this country and … in markets for our goods where the cotton was produced’.Footnote 70 In 1927, the BCGA annual report emphasized that the work of the ECGC would ‘ultimately be of great benefit to the Lancashire Cotton Trade’.Footnote 71 Despite this rhetoric, however, the ECGC was hardly committed to provisioning Lancashire, but instead focused on technical matters such as developing pest-resistant varieties. Textile manufacturers themselves also took little interest in empire cotton, which, as one civil servant in the Colonial Office put it, was ‘practically unknown except where spinners have been coaxed (practically in all cases by the Association) into using it’.Footnote 72 Perhaps this should not come as a surprise, given that Britain’s textile industry – and thus its demand for raw cotton – was declining faster than that of any other European colonizer in Africa between 1920 and 1960 (see Figure 1).

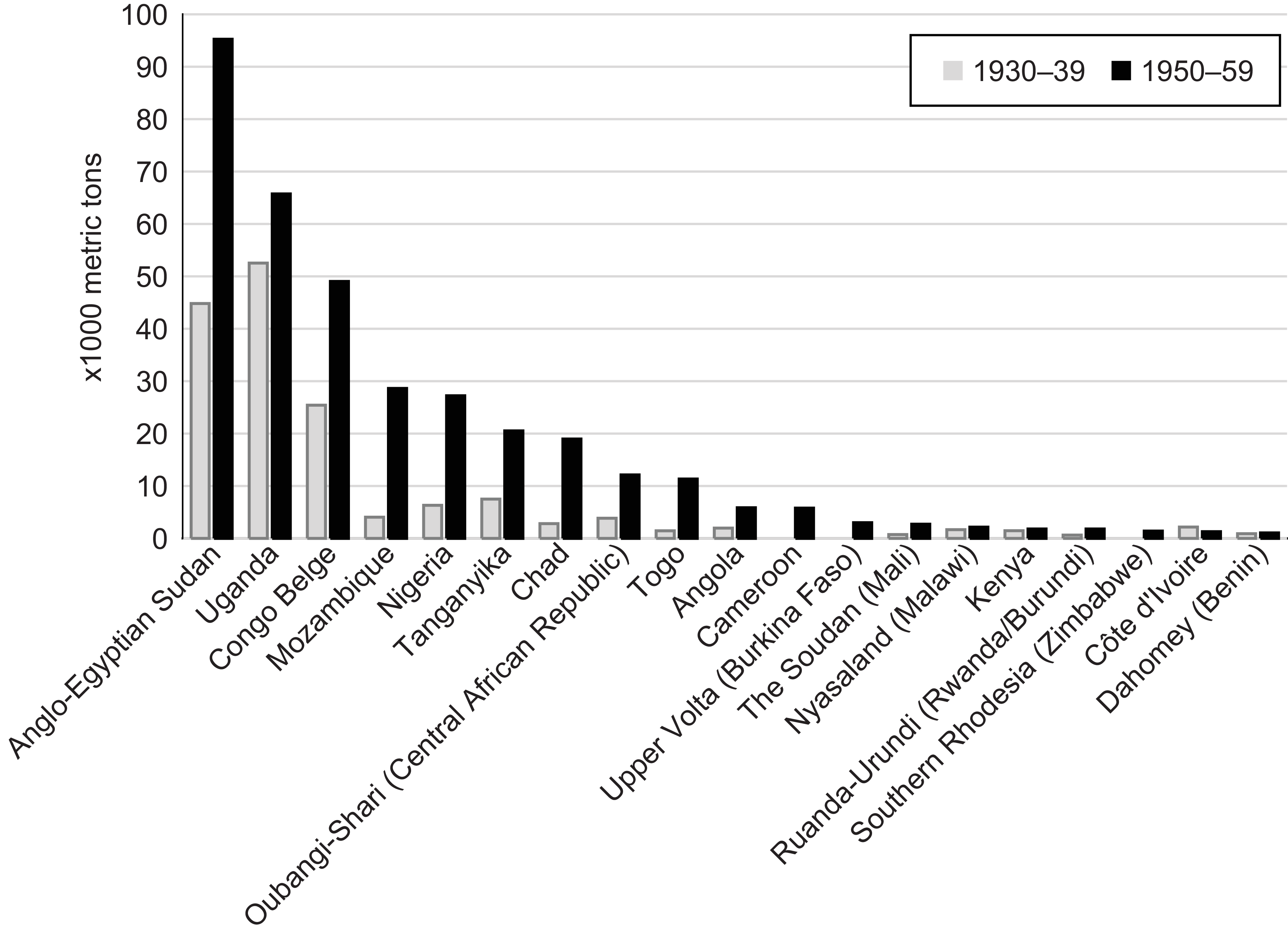

Figure 6a charts recorded output in the twenty colonial territories that produced most cotton (excluding Egypt) during the 1930s, when African production for world markets had taken off in earnest, and the 1950s, the final decade in which most of Africa was still under colonial rule. Production was strikingly concentrated. Sudan and Uganda – both under British control – accounted for 62 per cent of all recorded output in the 1930s, and 45 per cent in the 1950s. This is not, however, where Britain’s cotton promotors concentrated their hopes and efforts.

Figure 6a. Cotton output per African territory, 1930s and 1950s (excl. Egypt).

Source: Reproduced from De Haas, ‘The Failure of Cotton Imperialism’, 1103, using data in the online appendix.

The Sudan is a somewhat exceptional case, as most of its cotton (much of it of the long-staple types also grown in Egypt) was grown under highly capitalized conditions and in a unique ecological niche at the confluence of the Blue and White Nile, which was particularly suitable for irrigation.Footnote 73 The ‘Gezira Scheme’ was a profit-sharing enterprise, involving the colonial government of the Sudan, the Sudan Plantation Syndicate, and tenant farmers.Footnote 74 The BCGA was keen to see Sudan succeed as a cotton producer, and did participate actively in a lobby to construct the Sennar Dam, a project that was completed in the 1920s.Footnote 75 However, according to Robins, the BCGA ‘was merely a shareholder and a promoter in a larger capitalist and government enterprise’.Footnote 76

Uganda was also on the margins of BCGA’s Africa strategy, a point to which we will later return. As noted earlier, the hopes of cotton imperialists in Britain had long pivoted on Nigeria. As late as in 1915, British cotton expert John Todd conjectured that ‘the possible cotton crop of Nigeria is about 6,000,000 bales of 400 pounds’.Footnote 77 In 1924, BCGA chairman Sir William Himbury estimated Nigeria’s potential at a million bales.Footnote 78 In reality, Nigeria came to export a meagre average of 70,000 bales annually between 1920 and 1960, a mere 1.2 per cent of Todd’s projection, and 7.0 per cent of Himbury’s.Footnote 79 Meanwhile, Todd substantially underestimated Uganda’s cotton potential, almost by a factor of three.Footnote 80 Thus, even though Britain exported by far the most cotton from its African colonies, spatial patterns within British Africa aligned poorly with the stated aims and expectation of cotton imperialists, whose role in the relative success of Uganda and Sudan was hardly decisive.

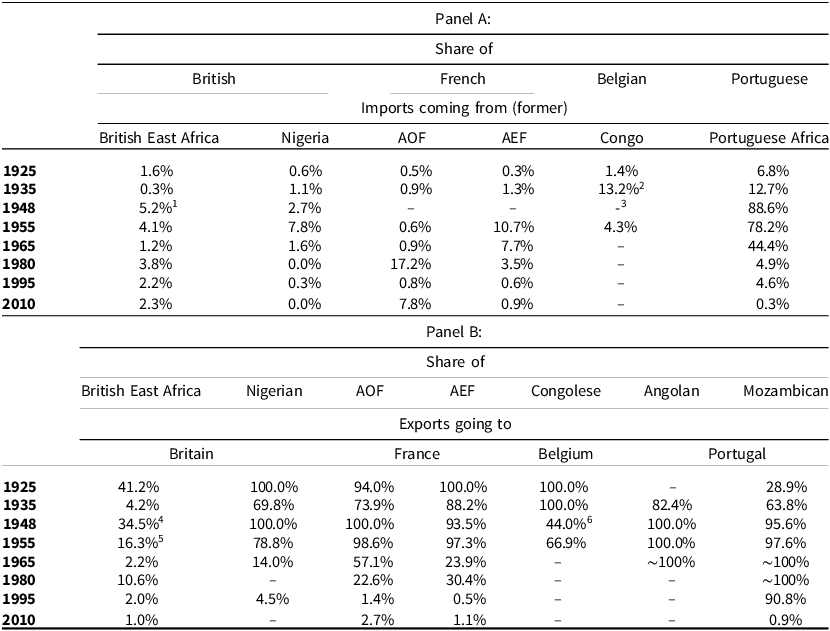

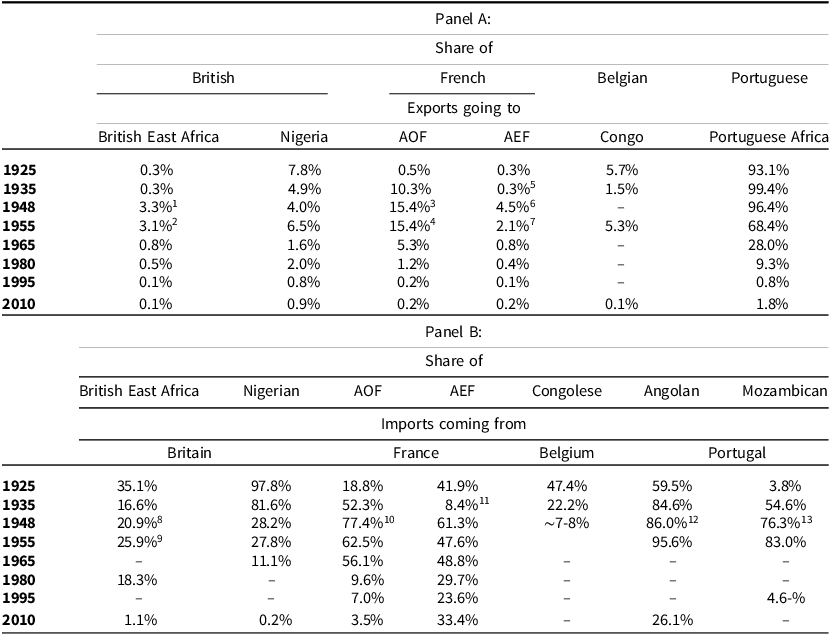

What we have not been able to establish yet, is how much European industries benefited from the cotton that was actually grown in colonial Africa. A comprehensive answer would require us to know the level and fluctuation of the price paid by European manufacturers for raw cotton and compare these to a counterfactual price without access to African colonial cotton. Because such an analysis is fraught with methodological challenges, I take a simpler approach and calculate trade shares between selected colonies and metropole at approximately ten-year intervals from 1925 to 1955. I also show estimates, where available in the COMTRADE database and supplemented by the FAOSTAT database, for post-colonial benchmark years between 1965 and 2010.Footnote 81

Table 1, panel A shows the contribution of key African (former) possessions to the raw cotton supply of their (former) European colonizers. The share of British cotton supplies coming from British East Africa (mainly Uganda) as well as Nigeria were marginal overall, as were French supplies from Afrique Occidentale Française (AOF) and Afrique Équatoriale Française (AEF). Belgium also sourced a small share of its raw cotton from Africa. In German Africa, the situation had not been much different: in 1913, only 0.5 per cent of Germany’s cotton imports were sourced from its African possessions.Footnote 82 The only European textile industry that relied to a large extent on African supplies was Portugal’s, and increasingly so as its output more than doubled between 1925 and 1948. This trend is in line with the imperial autarky policies pursued by the Estada Nuovo regime under António de Oliveira Salazar.Footnote 83 However, for perspective, it is important to note that Portugal’s textile industry was very small by European standards (see Figure 1).

Table 1. Raw cotton trade value shares between selected colonies and metropoles

Notes: ‘-’ denotes a missing observation, in some cases due to the absence of trade. 11949; 21933; by 1939, this had risen to 39%, according to Sven van Melkebeke, ‘De Gentse-Congolese Katoenrelaties (1885–1960): Een Verkennend Onderzoek naar Bedrijven en Ondernemers’, Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis 53, no. 3 (2023): 57–9, 63; 3The same article reports 26% in 1951 and 15% in 1954; 41949; 51954; 61950. For the data post-1960, the value of trade between colonizer and colonies was taken from (former) colonizer bilateral trade statistics in United Nations, ‘COMTRADE’. Total exports from the colonies were taken from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, ‘FAOSTAT’. All 1965 data for former AOF and AEF were taken from their bilateral trade statistics in United Nations, ‘COMTRADE’.

Sources: Bluebooks of: the Uganda Protectorate, Kenya, Tanganyika Territory, and Nigeria; Annual Trade Report of: Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika; Statistical Abstract for the British Empire; Statistisch Jaarboek voor België en Belgisch Congo; De Economische Toestand van Belgisch Congo en van Ruanda-Urundi; A. Brixhe, De katoen in Belgisch Congo (CotonCo, 1953), 116; Van Melkebeke, ‘De Gentse-Congolese, 64; Anuário Estatístico of Angola and Moçambique; Comércio externo of Angola and Moçambique. Anne Pitcher, Politics in the Portuguese Empire: The State, Industry, and Cotton, 1926–1974 (Oxford University Press, 1993), 283, 286; Renseignements généraux sur le commerce des colonies françaises; Annuaire statistique de l’AOF et Togo; Compendium des statistiques de commerce extérieur de l’UFOM; John Singleton, ‘Homage to Lancashire: The Cotton Industry’ (PhD Diss., University of Lancaster, 1986), 228; Jennifer Ann Dawe, ‘A History of Cotton-Growing in East and Central Africa: British Demand African Supply’ (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 1993), 427; Statistique générale de la France; Tableau général du commerce extérieur; United Nations, ‘COMTRADE’ database, accessed January 2025; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, ‘FAOSTAT’ database, accessed January 2025.

Table 1, panel B shows the importance of metropolitan markets for African raw cotton exports. Here the picture is different: most cotton produced for export in Nigeria, AOF, the Congo, and Portuguese Africa was exported to the metropole. In the former French and Portuguese possessions, this continued to be the case in the first decades after independence, suggesting that strong raw material trade ties were maintained for some time, before they eventually faded. This is especially notable in the case of the former French colonies, where cotton production expanded rapidly during the post-colonial era (see Figures 5 and 6b). The major exception to this overall pattern of strong trade ties between colony and metropole is British East Africa (Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda) – notably by far the largest cotton-exporting region among the selected cases during the colonial era (see Figure 6a). From 1915 onwards, India quickly became the most important destination for Ugandan cotton.Footnote 84 In the interwar era, relatively long-stapled cottons from East Africa made up the majority of Bombay’s raw cotton imports, which in turn came to satisfy just under a fifth of total cotton consumption by producers in Bombay.Footnote 85 From the 1920s, onwards some cotton went to Japan as well. Only a small proportion of the region’s cotton went to Britain (see Table 2, panel B).

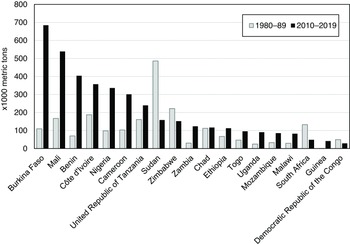

Figure 6b. Cotton output per African territory, 1980s and 2010s (excl. Egypt).

Source: Author’s calculations based on Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, ‘FAOSTAT’.

Table 2. Cotton piece goods value trade shares between selected colonies and metropoles

Notes: ‘- ’ denotes a missing observation, in some cases due to the absence of trade. 11949; 21954 and based on weight, not value; 3based on weight, not value 4based on weight, not value 51938 6 based on weight, not value 7based on weight, not value 81949; 91954; 101949; 111938 121949; 131949.

Sources: See Table 1.

As pointed out by Robins, ‘while French, German, and Portuguese colonial cotton-growing programs reserved empire-grown cotton for their metropolitan industries, the BCGA was committed to the economic ideas of the Manchester School [i.e. free trade]. Any cotton the BCGA’s efforts produced would be offered to the highest bidder, rather than protected for British markets.’Footnote 86 At several moments this position clashed with British cotton interests, for example contributing to the lukewarm reception of the BCGA’s early fundraising efforts in Lancashire.Footnote 87 During the interwar era, when cotton began to flow to India and Japan, grievances intensified. Certainly, the free-trade stance in Uganda irked this trader, c. 1925:

It is indeed a curious commentary upon British colonial rule that an industry that has been built up with British capital aided at the beginning by grants in aid from the British taxpayer, and later by voluntary contributions from the Lancashire cotton industry, should be jeopardised for the sole benefits of the natives of a Dependency that is through boycott and legislation endeavouring to shut out the manufactures of Lancashire, while some two thirds of that crop is now diverted to the Bombay market.Footnote 88

The 1927 annual report of the BCGA argued, perhaps to reassure critics, that ‘where the BCGA has any influence the cotton is invariably brought to Lancashire, and in addition others are encouraged to ship to this country’.Footnote 89 However, in practice, as Table 1 shows, Britain’s share in colonial cotton exports only declined further in subsequent years.

Table 2, Panel A, shows the share of European textile exports going to African (former) possessions. Here, the importance of – at least some – African colonial markets to European industries is more evident. British East Africa was not an important market for British textiles, and the Congo did not absorb any sizeable share of Belgian textiles, which may be one reason why textile factories were established in the Belgian Congo early on.Footnote 90 However, Nigeria was a significant market for British textiles, while AOF, from the 1930s onwards, absorbed a sizeable share of French textile exports. Colonial markets overall became increasingly important for France’s waning textile industry, following protectionist measures in the 1930s.Footnote 91 Clearly, and in contrast to the other imperial spheres, African markets were the lifeblood of Portugal’s increasingly isolated and technologically backward textile industry, and basically its sole market abroad. However, such colonial autarky and protection only contributed to further technological backwardness of the industry in the long term.Footnote 92

Turning to Table 2, Panel B, we can see that consumers in British East Africa sourced most of their textiles from places other than Britain. These alternative sources were India and Japan primarily.Footnote 93 Nigerian textile imports, initially, did come mostly from Britain, but this changed after the Second World War. A similar decline in importance of metropolitan textile imports is visible in the Belgian Congo. In AOF and AEF the share of textiles coming from France increased (aside from AEF in the 1938 benchmark, when Japanese imports dominated while they were shunned from AOF), which is consistent with the growing importance of colonial markets for France’s industry. The trend for Portuguese Africa is similar, but even starker. After independence, the role of metropolitan textiles in former colonies declined, although slower and to a lesser extent in the former French colonies.

In conclusion, the trade share analysis yields a mixed picture. The raw cotton trade data gives us little reason to view cotton imperialism in Africa as economically important to European textile industries, except for the Portuguese case. The textile trade data reveals a greater importance of African colonies as a market for finished products. The role of African markets was highest when European textile industries were already in decline and losing market share elsewhere, first in the case of Britain, and later on in the case of France and Portugal. Thus, if anything, the analysis further confirms that cotton imperialism propped up declining old staple industries, cushioning a decline of employment rather than lubricating a vibrant economic sector.

Reinterpreting colonial cotton policies in Africa

Why were the European protagonists of cotton imperialism not more successful in shaping cotton outcomes in Africa? As noted in the introduction, earlier scholarship explains the failure of colonial policies on the ground mostly as a result of resistance and adverse local realities which colonizers were unable to overcome.Footnote 94 In the remainder of this article, I add a fundamental and necessary layer to explain divergent cotton outcomes in twentieth-century Africa, further elaborating the argument that colonial policies themselves were often not aligned with, and hardly served the interest of, metropolitan industries.

As a first case, let us examine British Africa, where cotton took off in East Africa, and not in Nigeria. The high metropolitan expectations projected on Nigeria resulted partly from the perceived potential of its large indigenous population and thriving textile handicraft sector, but also from the fact that the BCGA was initially dominated by merchants with vested interests in West Africa.Footnote 95 Alfred Jones, the BCGA’s inaugural president, had himself made his fortune in West African trade.Footnote 96 The BCGA was not only involved in buying and ginning cotton and experimenting with new varieties, but also set up an effective lobby to establish a railway to Kano, which was envisioned to transport cotton to the coast. However, local farmers and traders opted for another crop, groundnuts, which offered higher returns to labour and saw a more favourable price development in the years after the railway’s completion in 1911.Footnote 97 When faced with this reality, the colonial state’s commitment to cotton exports proved superficial, and little was done when local farmers and traders proved indifferent to cotton from the start, or abandoned it after disappointing initial returns. Another example was the Gold Coast, where cocoa farming and labour migration soon proved far more lucrative than growing cotton, and initial efforts by BCGA and the colonial government ran came to nothing.Footnote 98 According to Robins, colonial governments ‘abandoned cotton with alacrity wherever more promising industries turned up’.Footnote 99 Moreover, across West Africa whatever cotton – often modest amounts – was grown on farmers’ plots found a ready local market at more favourable prices than the BCGA was able to offer for export.Footnote 100

While attempts to export cotton from colonial West Africa were thus hardly successful and certainly did not live up to expectations, cotton cultivation in Uganda did take off. Unlike the Kano railway, the Uganda railway, which was completed in 1901, was not primarily envisioned to carry cotton. Export cultivation was promoted in the early 1900s first and primarily by the Uganda Company, a commercial branch of the Anglican Church Missionary Society, albeit with seeds provide by the BCGA.Footnote 101 The rapid cotton take-off in Uganda was, of course, followed with interest by the BCGA. In 1913, Daudi Chwa, the Kabaka (king) of Buganda, Uganda’s chief cotton-growing region at the time, was hosted by the BCGA in Manchester, and was given a taste of cotton imperialism when its chairman Hutton lectured that ‘the more cotton there is grown the better it is for the people because the more abundant the supply of raw material, the cheaper will be the finished article’. He also remarked that Ugandan cotton ‘is a type of cotton Lancashire wants. I hope they will grow more and more and we shall be delighted to use every bale of it.’Footnote 102 However, this would not be true for long, as only a few years later India, not Lancashire, became the most important destination of Ugandan cotton.

If not primarily through the efforts of cotton imperialists and to the benefit of metropolitan industry, why did Uganda become a major cotton exporter? Colonial coercion, while not absent, was comparatively limited in the case of Uganda, and while chiefs initially actively promoted the crop, ‘peasant initiative’ played a large role in the spread and sustained production of the crop. I have systematically analysed Uganda’s colonial take-off in contrast with stagnation in French West Africa. My analysis points at Uganda’s two rainy seasons (compared to only one in West Africa’s savanna) as a crucial enabling factor for the adoption of cotton – a labour-intensive and inedible crop – in a context of low yields.Footnote 103 As further enabling factors, we can add Uganda’s comparatively high population density and the presence of Indian entrepreneurs who set up several hundred up-country ginneries and buying posts, factors which notably reduced the cost of marketing. Not coincidentally, these entrepreneurs received much of their capital from the textile industry in Bombay. The colonial government in Uganda was also keen to support the cotton sector, as it helped finance the colonial bureaucracy and make it independent of imperial ‘grants-in-aid’ – both directly, through poll taxes, and (from the 1920s onwards) export taxes, and indirectly through taxing imported consumer goods which rural Ugandans bought from the proceeds of cotton.Footnote 104

Illustrative of the colonial government’s priorities was an attempt, in 1927, by the British Cotton Corporation Limited, a group of London-backed businessmen, to acquire a ‘controlling interest’ in Uganda’s cotton ginning sector. The group cited the fear that Japanese encroachment would eventually ‘preclude English and other interests from obtaining supplies of Uganda cotton’. They also argued that their initiative would improve conditions for Uganda’s growers by taking over and ‘rationalizing’ Uganda’s decentralized and purportedly inefficient ginning sector. Despite a forceful lobby, they ultimately failed to gain the necessary support from the Colonial Office and Uganda’s governor. Nor were the BCGA and ECGC willing to put their weight behind the initiative.Footnote 105 This was a crucial moment: cotton from Africa’s most productive colony continued to flow primarily towards India and the lion’s share of its ginning capacity remained firmly in Indian hands until the rise of African cooperatives in the 1960s. The expulsion of its commercially important Asian community and a breakdown of the economy and institutions under the rule of President Idi Amin (1971–79) and his successors largely explain the cotton sector’s post-colonial demise.Footnote 106

As a second case, we turn to the interwar era, when coerced cotton cultivation expanded substantially, first in the Belgian Congo, and subsequently in AEF and Portuguese Africa, Mozambique in particular. After Sudan and Uganda, these three colonial territories had become the largest sub-Saharan cotton exporters by the 1950s (see Figure 6a). However, the nature of their cotton economies was distinctly different from that of Uganda, as well as other less-coercive contexts such as Nigeria and French West Africa. Figure 7 shows the prices received by farmers for their raw cotton in each of these contexts, relative to those in Uganda. Substantially lower prices are indicative of a system where colonial coercion replaced economic incentives. Colonial administrations in Central Africa, in collaboration with concessionary companies, were intervening deeply into rural economies to extract cotton, against the will and interests of the indigenous population. A clear signal of the latter is that the cotton sector in the former Belgian Congo, the Central African Republic, and Mozambique collapsed immediately after independence. Chad’s cotton sector held up better, but it did not experience a take-off comparable to that in the former AOF colonies, where farmers had not been compelled to the same extent to cultivate the crop. Tellingly, the slogan of Chad’s first political party was ‘no more cotton, no more chiefs, no more taxes’.Footnote 107 This makes for an illustrative contrast with (northern and eastern) Uganda, were cotton continued to be grown in large volumes after independence, even reaching a peak, until the sector collapsed in the 1970s.

Figure 7. Cotton grower prices relative to Uganda.

Notes: The unbalanced series is an average of all available years for each individual territory (1920–60). The balanced series only looks at years for which all countries are available (the 1950s). Note that Ugandan cotton growers benefited from a small premium of 5 to 10 per cent deriving from the fact that they cultivated longer-staple cotton than in most other African contexts.

Sources: Abakar Kassambar, ‘La Situation économique et sociale du Tchad de 1900 à 1960’ (PhD diss., Université de Strasbourg, 2010)’; Nelson S. Bravo, A cultura algodoeira na economia do norte de Moçambique (Junta de Investigaciones de Ultramar, 1963); Michiel de Haas, ‘Measuring Rural Welfare in Colonial Africa: Did Uganda’s Smallholders Thrive?’, Economic History Review 70, no. 2 (2017): 605–31; Gerald K. Helleiner, Peasant Agriculture, Government, and Economic Growth in Nigeria (Richard D. Irwin, 1966); Osumaka Likaka, Rural Society and Cotton in Colonial Zaire (University of Wisconsin Press, 1997); Monica M. van Beusekom, Negotiating Development: African Farmers and Colonial Experts at the Office du Niger, 1920–1960 (Heinemann, 2002).

Why did various colonial powers choose to set up coercive cotton schemes in their central African possessions? A major expansion of cotton cultivation took place in the Belgian Congo in the 1920s, when cotton became one of the key cultures obligatoires. Cotton growing was supervised by concessionary companies and by the state, and Africans cultivated the crop reluctantly and under compulsion.Footnote 108 Because growers received extremely low prices (see Figure 7), large margins could be reaped by companies and the state, especially at a time when industries and mines struggled during the 1930s Great Depression, and many returned unemployed to the rural areas. Indeed, prices received by farmers were so low and conditions so oppressive that, according to one Belgian observer in 1943, ‘villages are not merely empty because of mine recruitment but because the Black [sic] wants to flee. Finding a job among Whites [sic] is an escape from a birthplace which has become odious. The reason is cotton, which the Blacks hate …’Footnote 109

Colonial cotton growing efforts in the Congo yielded comparatively high returns, despite the lack of economic incentives for the hundreds of thousands of indigenous growers who toiled in the fields for a bare return. This outcome should be understood in a context of comparatively favourable environmental conditions, especially the long rainy seasons which, in large parts of the Congo, allowed for two consecutive harvests per year.Footnote 110 Moreover, to cope with the high labour demands of cotton, farmers shifted to less labour-intensive food crops, cassava in particular.Footnote 111

Belgian cotton policies in the Congo stand out for the establishment of several textile factories on African soil from 1925 onwards, to serve the local market with affordable textiles that could compete with cheap grey cloth imports from the United States (mericani) and, later, Japan. Although these factories absorbed only a small share of all the cotton that was grown in the colony (equivalent to about one-fifth in the interwar years), their presence sits uneasily with the idea that colonial cotton growing efforts existed primarily to serve the interest of Belgian-based textile factories and their workers.Footnote 112 In 1950, there were a mere seven textile mills in all of sub-Saharan Africa (South Africa, with two large mills, excluded), consuming some 13,000 metric tons of cotton. Of these, three were in the Congo, consuming over 8,000 metric tons.Footnote 113 Belgian cotton policies, then, appear to have been shaped more by financial interests (which also dominated CotonCo) while metropolitan industrialists played a more marginal role.

In AEF, substantial efforts and investments were made to expand peasant cotton production. During the 1930s, output expanded substantially in Chad and later Oubangi-Chari (see Figure 6a). This coercive push mainly resulted from an attempt to make a poor colony pay for itself. Because Chad was landlocked and did not have a railway, cotton lint was expensive to export despite its high value-for-weight, and the only way for the administration to make the venture profitable was to offer extremely low prices to African growers, and by replacing economic incentives with compulsion. European textile industries showed little interest in Chad, and cotton growing hinged almost entirely on coercion by the colonial administration and concessionary companies, who were given exclusionary buying rights and substantial powers to direct peasant cultivation and marketing of cotton, often working through local agents to enforce supply.Footnote 114 That large-scale cotton cultivation did not lead to famine and breakdown of the cash-crop sector in the dry savannah of Chad is plausibly linked to a dense network of rivers, which enabled flood-bed agriculture and fishing and thus made people somewhat less dependent on seasonal agriculture. Moreover, evasion, protest, and flight were difficult, given Chad’s isolation, in comparison to AOF, which limited people’s options to escape colonial control and vote with their feet.

Another example of coerced and poorly renumerated cotton cultivation is Mozambique. While Portuguese efforts to extract cotton from its African possessions go back to the early nineteenth century, it took until the 1930s, under the reign of Salazar, for output to finally take off.Footnote 115 As in AEF and the Belgian Congo, Portuguese cotton-growing schemes were run by monopsonistic concessionary companies, which cooperated with the state to pressure African growers, often through (the threat of) violence.Footnote 116 A strong belief in the benefits of imperial autarky underpinned Salazar’s rule, which also faced increasing political and economic isolation. Indeed, as Table 1 and 2 show, Portuguese textile factories came to rely heavily on the African colonies, both as a source of raw material and a market for their output. But while this seems an exemplary case of cotton imperialism, Portuguese policies did not always serve the interests of metropolitan textile producers, as there were many years in which Portuguese buyers in fact had to pay higher prices for their colonial supplies than they would have paid in free market conditions. Moreover the quality of colonial cotton was variable and often poor. While Portuguese industries did benefit from shielded colonial markets for their products, their competitiveness was compromised in the longer run.Footnote 117

A third and final case to be discussed here is the belated cotton take-off in AOF. Even though cotton first took off in AEF, French cotton expansion efforts centred on the dream to establish a ‘French Gezira’ along the Niger river in the Soudan (Mali), in AOF.Footnote 118 The establishment of the ‘Office du Niger’ was pursued with vigour in the 1920s and 1930s. To finance these ambitions, in 1927 the ACC followed the British model by introducing an obligatory tax on French textile producers to finance its activities in Africa.Footnote 119 However, despite substantial financial investments and efforts to recruit African settlers to cultivate cotton on the banks of the Niger river, often involuntarily and labouring under harsh circumstances, the Office never produced sizeable quantities of cotton for export.Footnote 120 Several decades of efforts across French West Africa to entice and coerce peasants to grow cotton also yielded very meagre returns.Footnote 121 Instead, oilseeds (groundnuts) were by far the most valuable raw commodity exported from AOF, mainly from Senegal. Echoing the logic of cotton imperialism, a French observer argued in 1942 that ‘the natives are producers of oilseeds and consumers of fabrics. It is on this simplified diagram that the economic life of the colony is based.’Footnote 122

Interestingly, however, from about mid-century onwards, smallholder cotton production for export belatedly took off across French West and, to a lesser extent, Central Africa. This reversal was largely the outcome of French efforts, initially motivated by acute shortages of foreign exchange during Europe’s post–Second World War reconstruction.Footnote 123 Aiming to improve the quantity and quality of cotton produced in its African colonies, the French government established the Institute de Recherches des Cotons et Textiles (IRCT) in 1946 and the Compagnie Française pour le Développement des Fibres Textiles (CFDT) in 1949. In 1955, caisses de stabilisation (marketing boards) were established to stabilize prices. These infrastructures largely remained in place in the post-colonial period. They were partly co-opted by independent states, while French influence remained substantial.Footnote 124 Crucial to this belated take-off was an integrated approach, involving improved cultivation methods, seeds, and inputs as well as active coordination of the supply chain which helped to stabilize prices and improve access to markets. These efforts benefited both cotton and food crops and helped farmers overcome seasonal labour bottlenecks.Footnote 125

According to Campbell, in the mid-1950s, France’s textile interests were still reasoning along cotton imperialist lines when they called for ‘an updating and extension of the French mercantilist trade system, which assigned overseas French colonies a two-fold purpose: a source of raw materials and a market for metropolitan exports’.Footnote 126 Policies were formulated in such a way that the region would be tied to France even after independence.Footnote 127 However, this only partially materialized. In the 1950s, plans were developed not only to expand cotton growing in the region, but also to establish local, but French-owned, textile factories – as had been done in the Belgian Congo in the preceding decades. Some of these initiatives failed quickly, while a few others (especially in Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon) expanded and thrived until the 1980s. By 1973, there were twenty-two textile factories in Francophone West and Central Africa, and between 10 and 40 per cent of each country’s raw cotton was processed domestically.Footnote 128 Of the cotton produced locally, a declining share reached France. Nonetheless, and at least for some time, the former French African colonies were viewed as a privileged space for a weak and waning industry.

Conclusion

In 1975, the British government terminated the Cotton Research Corporation (formerly the ECGC, until 1966). On its dissolution, its president, Lord Derby, tapped into the logic of cotton imperialism, arguing that when the Corporation was founded in the 1920s, ‘the emphasis was on the production of crops for export … of benefit to Britain, whose industries wanted new sources of raw materials, and to the producing countries, which could thus earn revenue to finance much-needed development’. Times had changed, however, he argued, and issues of global food insecurity and hunger had taken precedence.Footnote 129

Derby could have added that in 1975, the cotton consumption of Britain’s declining textile industry had shrunk by 85 per cent since 1902, the year the BCGA was founded, a reality that was probably much more decisive for definitively closing the case for British cotton imperialism than the lofty development goals he chose to emphasize. But exactly what case was closed? Despite their powerful and enticing rhetoric, British cotton lobbyists had never truly captured the metropolitan and colonial governments, and their ambitious visions remained, to a very large extent, unrealized. Cotton exports from British Africa had expanded during the colonial period, but not in the places and directions that promotors of empire cotton had targeted most heavily. The trade links between the British textile industry and African colonies had remained small. When cotton exports from Africa finally began to reach substantial volumes, Britain’s cotton textile industry had already entered a process of sustained decline.

This rift between metropolitan rhetoric and colonial policies on the ground was not just a result of local conditions and African resistance overriding European ambitions. Although such factors were important, this article has emphasized that colonial governments’ own commitment to cotton was also shallow. Special interests did not manage to capture the colonial state, and, aside from perceived acute supply crises in the 1870s, 1900s, and 1920s, were reluctant to commit resources to imperial cotton. Where cotton did expand, it was often not to favour European industries. Uganda’s expanding cotton exports, grown by smallholders in favourable environmental conditions, with good market access, and subjected to only limited colonial coercion, were increasingly shipped to India and Japan, not to Lancashire.

As I have shown, this reality of – at most – partial capture of the colonial project in Africa by cotton interests applies also to France, Belgium, and Portugal. Chad’s forced cotton schemes were not established primarily to serve French textile interests, but to make a poor landlocked territory financially self-sufficient. The Belgian Congo’s coercive cotton schemes did not feed a Belgium-based industry but brought in colonial revenues and facilitated the establishment of Belgian-owned textile factories in the Congo itself. The Portuguese colonies’ tight linkage to the metropole hardly benefited industry: colonial cotton was often of poor quality and, for part of the period, pushed onto Portuguese manufacturers above world market price. Even in these cases of colonial coercion, the template of cotton imperialism hardly explains policies and outcomes on the ground.

The situation in post-colonial Francophone West Africa provides a challenging counterpoint to my general argument that metropolitan blueprints were not decisive for African outcomes. While Britain was wrapping up its efforts to promote cotton in Africa, France was still heavily involved in cotton-growing efforts in its former Central and, especially, West African territories, while French textile exports were still taking a large share of the African market. That France’s involvement was so sustained is consistent with the temporal trajectory of its textile industry: in 1975, it still consumed about the same amount of cotton as it had in 1903, the year in which the ACC was founded. However, even if the case for ‘cotton neo-imperialism’ persisted in ‘Françafrique’, little actual cotton flowed from the colonies, and local imperatives, including the establishment of a local textile industry, proved more decisive for local cotton outcomes than the hopes and interests of European industrialists.

For global history more broadly, the case of cotton in colonial Africa illustrates the limited extent to which the ‘simplified diagram’ of economic imperialism ‘recast’ global commodity frontiers.Footnote 130 Metropolitan rhetoric mattered, but on the ground, policies were shaped by a multitude of conflicting colonial priorities: from creating investment opportunities for metropolitan capital, to stabilizing precarious colonial revenues and pulling rural Africans into export production, even if this meant abandoning cotton altogether or accepting exports being diverted away from the metropole. These dynamics could still be called forms of economic imperialism, but only if we accept a much broader definition – one that would recognize local colonial policy outcomes as inherently contextual, pragmatic, and diffuse.

Acknowledgments

For their input, I thank Aditi Dixit, Ewout Frankema, Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk, and audiences at the Posthumus Conference (Rotterdam, May 2021 and Leeuwarden, May 2024), the Harvard Economic History Seminar (April 2022), the Makerere University History Seminar (September 2022), the Economic History Society Conference (Warwick, March 2023), the European Social Science History Conference (Gothenburg, April 2023), and the Inequality Platform Workshop (Utrecht, November 2024). I also thank Yannick Dupraz and Felix Meier zu Selhausen for sharing colonial trade data, Anneroos Troost for research assistance, and the Dutch Research Council (NWO) for funding the project ‘A good crisis gone to waste? How the 1930s Great Depression deepened Africa’s primary commodity dependence’ (Grant Number: VI.Veni.211F.047).

Financial support

Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek,

Sociale en Geesteswetenschappen, NWO (Grant Number: VI.Veni.211F.047).

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Michiel de Haas is an economic historian of modern Africa. His work focuses on migration, inequality, agricultural development, and primary commodity trade, with a regional emphasis on Central-East Africa, Uganda in particular. He holds a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Utrecht University, and a PhD from Wageningen University. Currently he is an associate professor at Wageningen University. He has held affiliations with Makerere University, the Graduate Institute in Geneva, the University of Michigan, and Lund University.