Introduction

An emergency is one of the conditions that sharply highlights the centrality of mayors in local government management. They are required to emphasise preventive behaviour, adapt traditional municipal services to new needs, deal with cash flow problems resulting from the loss or postponement of revenues, mobilise and direct civil defence and volunteer groups, and enact special regulations. They have a broad and diverse range of activities that call for a varied use of legislative and management powers and the activation of new and more complex responsibilities.

As ‘navigators in the storm’, mayors present themselves to their community members as the main responsible actors (Ventura Reference Ventura and Campi2020), fulfilling a function that is not only political and administrative, but also ethical and identity-driven, capable of strengthening the relationship between communities and the state apparatus (Jong, Dückers and Van der Velden Reference Jong, Dückers and Van der Velden2016). Finally, as is always the case in crises, those who have institutional roles are the main reference point for people who have suffered the consequences of the crisis and who, therefore, place multiple expectations on them (Boin et al. Reference Boin, ‘t Hart, Stern and Sundelius2017). These concerns include assurances about the future, predictions about the evolution of the crisis, and implementation of appropriate and effective measures. All these offer mayors a political and communicative space that highlights the new prominence of their institutional role (Nye Reference Nye2009). They could regain the institutional ‘strength’ that has been declining for decades, as well as restore trust in government and public leadership (Boin, Kuipers, and Overdijk Reference Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk2013).

Against this backdrop, studies of local leadership in times of crisis tend to focus on the main tools used by leadership (meaning-making, decision-making, and learning) to respond to crises in ways that are convincing, useful, and inspiring to citizens (Jong Reference Jong2019). Numerous publications have explored public leadership in local governance (Sampugnaro and Santoro Reference Sampugnaro and Santoro2021; Garavaglia, Sancino and Trivellato Reference Garavaglia, Sancino and Trivellato2021; Torfing and Sørensen Reference Torfing and Sørensen2019), the complexity and organisational dynamics affecting leader strategies (Johannessen and Stokvik Reference Johannessen and Stokvik2018; Heinelt et al. Reference Heinelt, Magnier, Cabria and Reynaert2018) and the different aspects of adaptive leadership (Uy et al. Reference Uy, Kilag, Abendan, Macapobre, Cañizares and Yray2023; Hayashi and Soo Reference Hayashi and Soo2012).

The recent Covid-19 pandemic has also prompted research that discusses the extent to which public leaders and governments are prepared to deal with a crisis, emphasising the importance of administrative system settings, dynamic learning, rapid feedback, and accountability mechanisms (Pattyn, Matthys and Hecke Reference Pattyn, Matthys and Hecke2021; Stoller Reference Stoller2020).

However, there is a paucity of research on local leaders during crises, meaning that some questions remain unanswered. What is the mayor’s level of control over local policy processes aimed at addressing the crisis quickly? How is the leadership role interpreted with respect to the target community?

This study aims to answer these questions in order to understand the leadership styles of mayors during crises. The fundamental hypothesis underpinning the present study is that crises can act as catalysts for enhancing the trust relationship between mayors and their respective communities. Within the context of this study, a crisis is defined as a seminal event that offers insights into the performance of mayors in their roles and the community’s perception and interpretation of these roles.

This study adopted an exploratory approach. It was conducted through the qualitative analysis of five case studies on the mayors of the primary cities (Palermo, Catania, Messina, Syracuse, and Ragusa) of a southern Italian region (Sicily) that were analysed during the initial phase of the Covid-19 pandemic (February-May 2020). The decision to examine Sicilian cities was motivated by their comparatively greater structural fragility (both social and economic), in contrast to cities in other Italian regions. Sicily ranks lowest in Italy in terms of economic and social well-being (Istat 2023). This fragility is particularly well-suited to the research objective, as it generates a significant challenge for leadership efforts to manage emergencies, thereby offering a rigorous test of the resilience of political leaders. Moreover, examining particularly fragile socioeconomic contexts enables us to contribute new knowledge to the existing literature by providing an analysis of a relatively understudied area.

The selection of specific cities was based on their population size. In emergency management studies, crisis leadership activities have been observed to correlate with the size of the municipality. Consequently, larger cities are more likely to encounter intricate challenges affecting diverse facets of public life, including but not limited to education, healthcare, infrastructure, economic development, livelihoods, and security, than their counterparts in smaller municipalities (Jong Reference Jong2019). For these reasons, the decision was made to select the largest cities in terms of population.Footnote 1

The present study makes a novel contribution to the literature on local crisis leadership through two primary analytical dimensions. First, an integrative approach is adopted, synthesising two traditionally distinct areas of analysis: communication strategies and policy activities. This methodological integration facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of leadership resilience that extends beyond conventional frameworks. Specifically, it emphasises the capacity to effectively respond to unforeseen critical events by simultaneously generating innovative solutions and mitigating the impact of external environmental shocks (Weick, Sutcliffe and Obstfeld 2001).

Second, this study focuses on specific leadership styles that, although rooted in the broader domain of political leadership literature, remain underexplored within the context of crises, particularly at the local level. By examining these styles in scenarios that extend beyond routine administrative functions, this study provides a novel perspective on the role of mayors. In times of crisis, mayors are required to deliver responses that are not only efficacious but also capable of reducing uncertainty and fostering public reassurance. This necessitates a relational dynamic with citizens that extends beyond mere political representation, with the primary aim of enhancing public confidence in institutional authority and leadership.

The article is organised as follows. The introductory section reviews the existing literature on the role of mayors during crises and their leadership styles. This is followed by a detailed description of the research methodology, which encompasses both content analysis of social media posts and documentary analysis of administrative acts ‒ such as decisions, mayoral decrees, ordinances, and other relevant documents ‒ aimed at implementing new activities and services to manage the pandemic. The subsequent section provides a comprehensive analysis of the communication and policy strategies employed by mayors, culminating in the development of an analytical model designed to delineate specific leadership styles. In the concluding remarks, the study offers reflections on its contributions, emphasising the effective strategies adopted by certain mayors that fostered increased trust among citizens.

Mayors in the crisis between the personalisation of politics and public leadership

In Italy, starting in the 1990s, the mayor acquired new power traits that led to a wide margin of manoeuvre in managing local government, both in politics and policies.

This means that each mayor developed their own style of leadership, based not only on consensus building and the entourage that developed around them ‒ sometimes across party lines (Marletti Reference Marletti and Marletti2007) ‒ but also on the ‘civicness’ of government action (Natta Reference Natta2010). The latter aspect calls into question the mayor as an active promoter of a political project for which they are personally accountable to their electorate (Musella Reference Musella2020): possible re-election depends on their ability to respond to the needs of the community and no longer, as in the past, on decisions and agreements between or within parties. Therefore, there is a strong emphasis on the receptive (or responsive) capacity of their government and their ability to identify objectives suitable for pursuing the preferences, interests, and expectations of their own electorate. As a result, the mayor is accountable for what is achieved, beyond the pursuit of adequate levels of effectiveness, efficiency and economy.

However, in recent years, huge budgetary cuts have strongly conditioned the actions of Italian mayors, highlighting even more clearly than in the past the imbalance between seeking and consolidating consensus, on the one hand, and the enormous difficulties of ordinary administrative management on the other (Canzano Reference Canzano2012). The reduction in economic resources and the constraints imposed by the Patto di Stabilità have inevitably had an impact not only on the quantity and quality of services, but also on the new welfare demands triggered by the economic crisis: cuts in services are increasingly the solution adopted by mayors facing imminent risks of financial failure. The result is a growing crisis of consensus, which tends to destabilise dialogue with political forces and stakeholders.

This scenario became even more complex and critical during the period of the pandemic caused by Covid-19. Mayors faced new and unexpected problems and had to try to prevent or at least minimise the impact of the emergency. They had to find effective solutions quickly and confidently, even taking decisions that were not always acceptable to communities, for example, bylaws that affected constitutional freedoms (freedom of movement, residence, assembly, business, religion, and worship). In short, they had to manage new scenarios of action in which they translated their position of authority into effective public leadership to deal with the emergency.

Inevitably, all of this has led to an increase in the stakes of political leadership. Indeed, mayors now need to build a broader relationship with the community, with the aim of increasing trust in their institutional role (Nesti and Graziano Reference Nesti and Graziano2020), while called upon to find effective responses and maintain the support of voters who question their accountability and responsiveness (Garay and Simison Reference Garay and Simison2022). As is well known (Levi and Stoker Reference Levi and Stoker2000), trust constitutes one of the most important factors in the legitimacy of rulers, especially during crises: it shapes and sustains public perceptions of policies and the effectiveness of government action, and serves as a resource to promote compliance with regulations and guidelines that require social actions that cannot always be controlled or monitored.

In this regard, the literature emphasises the tendency of mayors to build political trust by leveraging the psychological dimension (Warren Reference Warren2018) – in other words, the dimension that drives the evaluation of government performance and causes the leader’s choices to be perceived as right (Easton Reference Easton1965). The strategy most commonly employed (at least in the initial phase of crises) was to reorganise essential services and benefits that, by their nature, ensure the satisfaction of interests and the pursuit of fundamental societal principles (Howitt and Leonard Reference Howitt and Leonard2009). In this manner, mayors eschewed ideological and/or party affiliation attacks, instead concentrating on the ethical tenets of ensuring the well-being of all citizens. Consequently, trust was established based on the moral evaluation attributed to or associated with the mayor, and thus on their perceived trustworthiness.

The formation of this trust is an additional phenomenon, distinct from the spontaneous and automatic effect observed in what has been called the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ phenomenon. In periods of sudden crises, there is a tendency for levels of trust in leaders and support for the government to rise, irrespective of the perceived merits of the policies being implemented (Baum 2022). Nevertheless, this does not imply that the leader is immune to the possibility of losing previously acquired trust or receiving less trust. Conversely, the necessity to maintain and regulate it becomes more crucial, and to achieve this, the primary instrument is ‘sense-making’ (Weick, Sutcliffe and Obstfeld Reference Weick, Sutcliffe and Obstfeld2005).

Indeed, it should not be forgotten that rhetoric plays a significant role during crises (Griffin-Padgett and Allison Reference Griffin-Padgett and Allison2010). The ability of leaders to make sense of a situation, explain what is happening (or has happened), and what is being done to manage the crisis allows them to establish a frame through which events are viewed and interpreted by citizens. As a result, beliefs are formed regarding the significance of events, challenges, and transformations. These beliefs often lead to positive perceptions of crisis management strategies. Consequently, the leader gains support for their decisions, enhancing the reputation and electoral prospects of their political party or government. It is imperative to recognise that this is not merely a matter of responding to citizens’ need for information so that they can react accordingly, but also of elucidating and advocating for the decisions taken by mayors, thereby mitigating citizens’ uncertainty and consequently fortifying their credibility (Roberts Reference Roberts2018).

Therefore, a significant proportion of the extensive array of communicative actions is directed towards instilling a sense of normality in the community, fostering hope, and providing emotional support for the most profoundly affected individuals (Jong, Dückers and Van der Velden Reference Jong, Dückers and Van der Velden2016). In this regard, leaders’ actions, such as visiting those most affected by the crisis and participating in ceremonies and events, can be seen as a means of demonstrating their proximity to the community, fostering a sense of hope and resilience among those affected. These actions can help mitigate feelings of vulnerability and facilitate adaptation to the crisis, thereby restoring a sense of the predictability and meaning of the world. In times of crisis, citizens expect their leaders to emerge publicly and support the healing process, foster hope and confidence, and provide care and assistance to those affected (Howitt and Leonard Reference Howitt and Leonard2009).

In essence, the mayor serves as a ‘beacon’, illuminating the path towards resolving intricate social, political, and economic challenges. The mayor represents a solution to complexity, functioning as a ‘cognitive shortcut’ that allows citizens to find a reassuring reference point. In this context, the mayor assumes a symbolic role as a prominent representative of society in crisis, acting as a kind of ‘citizen-father/mother’ (Jong, Dückers, and Van der Velden Reference Jong, Dückers and Van der Velden2016).

Crisis leadership: a brief literature review

Crisis leadership is conceptualised here in terms of managing the impact of unforeseen, unpredictable events that can have a serious impact on the performance of the administration and community. Following Prewitt and Weil’s (Reference Prewitt and Weil2014) approach, the leader’s actions should go beyond managing to minimise the damage caused by the crisis and seek to extract from it opportunities that may arise for their party. This is linked to a broader and more holistic view of the crisis which encourages the leader to be proactive and provides them with a vision, a direction, and an overview that allows them to fully exploit the dynamic potential of the crisis.

However, it is well known that crises pose increasingly difficult challenges, and that governance structures are generally not well designed to deal with new situations (de Clercy and Ferguson Reference de Clercy and Ferguson2016). Therefore several studies have tried to indicate what skills leaders should have during a crisis. In this respect, the theoretical framework of reference is that of Boin (Reference Boin2005), who distinguishes five important tasks: sense-making, decision-making, meaning-making, termination, and learning.

Starting from this, scholars have gradually articulated these tasks better. Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk (Reference Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk2013), for example, list ten key tasks including early threat recognition, sense-making, vertical and horizontal coordination management, accountability and improving organisational resilience. Riggio and Newstead (Reference Riggio and Newstead2023), by contrast, identify five key competencies ‒ sense making, decision-making, coordinating teamwork, facilitative learning and communicating ‒ referring to the Complexity Leadership Theory and thus to an adaptive approach to dealing with change.

However, the dominant view of what leaders should do in a crisis is that of ‘t Hart (Reference t Hart2011). He links good leadership to the community’s need for security and stability, pointing to the need for three distinct and interrelated qualities: prudence, support, and reliability. According to this approach, ‘effective public leadership is about provoking, enabling and protecting the work that others must do to enable the community as a whole to meet significant challenges’ (2011, 326). Based on this evidence, scholars subsequently note that ‒ beyond the objective difficulties of managing the crisis and popular expectations ‒ leaders can succeed if they have good political capital, communicate the crisis convincingly, and benefit from the perception that the cause of the crisis is exogenous (Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk Reference Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk2013). Beyond this prescriptive domain, the literature has also shown some interest in understanding what leaders do in crisis contexts. In this sense, the crisis leadership literature seems interested in identifying roles, styles and/or forms of leadership, borrowing leadership typologies from the political leadership literature. In terms of local leadership, for example, it is interesting to refer to John and Cole (Reference John, Cole, John and Cole2014), who develop a typology of leadership (city boss, visionary, caretaker and consensual facilitator) based on the adaptability of leaders in urban governance. Mouritzen and Svara (Reference Mouritzen and Svara2002), instead, use the typology of strong mayor, committee leader, collective, and council manager, looking at institutional arrangements. Heinelt and Hlepas (Reference Heinelt, Hlepas, Bäck, Heinelt and Magnier2006), inspired by the form of local government, distinguish between political, executive, collegial, and ceremonial leadership.

However, many studies tend to favour the difference between transformational and transactional styles, considering these two styles more appropriate for understanding leaders’ actions in crisis situations. It is worth recalling that in transformational leadership, the leader focuses on the process of change, encourages innovation through higher levels of motivation and commitment (Kouzes and Posner Reference Kouzes and Posner2017), and promotes collaboration, creativity, and a sense of belonging. Transformational leaders inspire and motivate followers to new performance/behaviour by creating a vision, setting expectations, and challenging followers to go beyond their own self-interest (Bass and Riggio Reference Bass and Riggio2006). In times of crisis, leaders can respond quickly by building trust among followers and increasing their confidence. Transactional leadership, on the other hand, focuses on the importance of results, goal setting, and the monitoring and control of results. To incentivise performance, the transactional leader uses exchange rewards and promises of rewards (Boehm, Enoshm and Michal Reference Boehm, Enoshm and Michal2010).

Other leadership styles that are commonly used to analyse crisis leadership are autocratic, democratic and laissez-faire styles. In the first case, the main characteristic emphasised is the objective of ensuring that plans/strategies are implemented. Leaders decide which members of the group are to contribute and to what extent, without asking anyone what they plan to do. In contrast, democratic leaders involve group members in the decision-making process (Bass Reference Bass1990). They make decisions collaboratively, using majority rules or in a consultative manner, and only after meeting with group members. Finally, laissez-faire leaders are characterised by minimal involvement, allowing their followers to make decisions (Vecchio, Justin and Pearce Reference Vecchio, Justin and Pearce2010). Therefore, they provide little guidance to their followers and allow them considerable autonomy.

Drawing on this extensive literature, our research explores the strategies used by mayors to manage the crisis generated by Covid-19.

Research approach and method

The research analyses the crisis leadership of mayors through the intersection of two main dimensions: communication and the construction of crisis response policies. These two dimensions are viewed in the context of the strategic challenges that leaders face during a crisis, thus allowing us to trace how the leaders exercise their roles.

In terms of communication, an analysis was conducted on the utilisation of social media by mayors. This decision is associated with the open and dialogic nature of this medium, which enables more frequent, open and targeted communication with constituents. It offers those in positions of political authority opportunities to communicate with citizens in times of crisis (Utz, Schultz and Glocka Reference Utz, Schultz and Glocka2013). This choice appears particularly compelling considering that social media has emerged not only as a strategic instrument but also as a unique means of reaching a significant portion of the population during the pandemic. Our analysis entailed a comprehensive examination of the posts disseminated on the mayors’ profiles across three predominant social networks (Facebook, X, and Instagram).

The analysis focused exclusively on posts whose content was directly related to the pandemic. This involved an approach that evaluated the individual claim in relation to the subject, promoting communication, the content of the message, and its temporal placement. To facilitate a more profound comprehension of the content of the message, an analysis form was constructed, divided into three variables: type of attachment (link, video, photo, etc.); target audience of the message; and objective of the message. Regarding the target audience of the message, the following categories were identified, following the model of Golbeck, Grimes, and Rogers (Reference Golbeck, Grimes and Rogers2010): internal communication – messages addressed to national, regional, and municipal political subjects; external communication – messages addressed to the media, associations, or public subjects; and transversal communication – messages addressed to all users considered as individual citizens. In the latter case, we distinguished between Media Activities, that is, messages aimed at signalling the presence of mayors in the media (e.g., participation in TV programmes, publication of articles and speeches in the media or on other digital platforms, press releases) and Personal Messages, that is, messages addressed to citizens and related to the private sphere (personal feelings, emotions, etc.). Finally, with regard to the objective of the message determining the communicative action, 11 classification modes were considered: 1) information (on regulations, decrees, and services activated by civil society, religious events); 2) service communication (control of the territory, institutional aid interventions); 3) empowerment; 4) awareness/involvement; 5) reassurance; 6) denunciation; 7) exhortation; 8) invitation to participate in social life; 9) personal commitment; 10) political support/sharing; and 11) proximity to the community (best wishes/condolences). To determine these categories, an open-coding approach was used (Pandit, Reference Pandit1996): all posts were organised into groupings by assigning labels that described the different types of message targets; once these groupings were stabilised, their names were used for the classification. In the case of ambiguous posts, classification was determined by the highest number of words used by the mayors to describe the content of the post.Footnote 2

A total of 670 posts published on the mayors’ social profiles between 21 February and 30 April 2020, that is, in the initial phase of the pandemic, were analysed. This phase was the most acute and critical one. Key metrics were identified, including the total number of reactions (comments, shares, and likes).

The second dimension of analysis concerns policy construction by political leaders (Borraz and John Reference Borraz and John2004) and is examined through an investigation of the activities and services deployed by mayors in response to the novel and emerging socio-economic and welfare needs generated by the Coronavirus pandemic. In particular, the service activities in question extend beyond those provided for and indicated by the Prime Ministerial Decrees (DPCMs) and regional ordinances. In other words, these initiatives demonstrate the mayor’s commitment to addressing the crisis by establishing new services or expanding existing ones through the utilisation of their own resources, including those pertaining to relationships, economics, expertise, technology and other forms of capital. Given their distinctive and independent character compared to national directives, these activities offer a valuable opportunity to assess mayoral leadership in shaping pandemic policies.

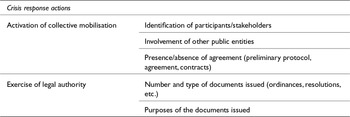

The investigation of these services is conducted through a documentary analysis of public decisions: union decrees, mayoral ordinances, as well as resolutions and determinations of the City Council. A total of 171 documents were examined. The data obtained from these documents were subjected to content analysis (Neuendorf and Kumar Reference Neuendorf and Kumar2015) to identify the existence of different possible ways in which mayors involved non-profit organisations in the design or implementation of these services. Two principal categories were identified: activation of collective mobilisation and exercise of legal authority. These were further subdivided into more specific categories, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Documentary Analysis Categories

Communication strategy

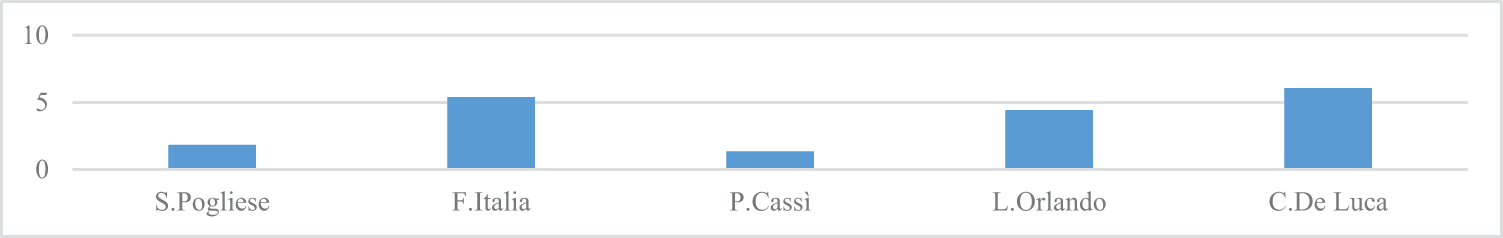

For communication, our mayors largely used profiles found on Facebook and Instagram.Footnote 3 However, there was no shortage of mayors who used all three different social networks (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) ‒ this was the case with the mayors of Syracuse (Francesco Italia) and Palermo (Leoluca Orlando) ‒ or mayors who relied almost exclusively on a single profile (that on Facebook), such as the mayor of Catania (Salvo Pogliese) and the mayor of Ragusa (Peppe Cassì). Cateno De Luca, the mayor of Messina (49%) and the mayor of Syracuse (24%) were particularly active in posting. The communicative ‘diligence’ of these mayors is also reflected in the average number of posts per day (Figure 1).Footnote 4

Figure 1. Daily average of posts published on social media by mayors.

Looking at individual mayors, Cateno De Luca stands out for having used, more than the others, a personal context of communication, which consisted of thanking the citizens for complying with strict regulations, obituaries, commemorations, etc., and for setting up communication designed to involve those following him. This was done by repeatedly inviting them to follow his direct and/or media appearances. What emerges is a personal approach that would draw the attention of the electorate and the media to himself.

In terms of content, the analysed posts confirm that during the pandemic crisis, the opportunities offered by social media become even more evident for leaders, who need to provide citizens with correct information and practical instructions, and to undertake control of collective anxiety and fear (Jain et al. Reference Jain, Malviya, Singh and Mukherjee2021). All our mayors show that they focused their communication on the measures taken by their respective administrations to combat the pandemic, as well as on citizens’ responsibility to comply with regulations and ministerial directives. There are also many communications aimed at encouraging citizens to show solidarity. When analysing the content of what the individual administrators wrote, some interesting profiles emerge (see Table 2 below).

Table 2. Content of posts (values%)

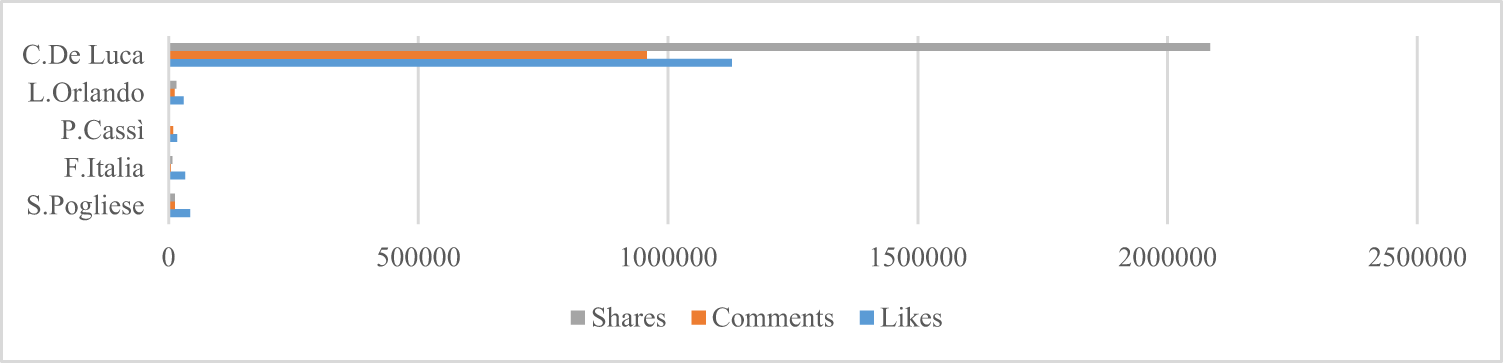

The mayor of Catania, for instance, composed a series of posts characterised by an emotional tone. These were primarily aimed at reassuring citizens about the virus containment activities that had been put in place (9.6%) and at encouraging citizens to participate in the ‘fight against resistance’ through appeals for responsibility, solidarity and a sense of belonging (17.3%). Despite the low daily productivity, this approach has been observed to stimulate reactions from followers. With the exception of Mayor Cateno De Luca, reactions to the posts in question were found to be higher than to those of other mayors (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Reactions produced by posts on Facebook.

The mayor of Palermo, on the other hand, opted for a more measured approach to communicating via social media. While he published numerous posts about the activities undertaken by the municipality, they often focused on the importance of responsibility and on criticising citizens who did not respect the current regulations. It is also noteworthy that over 5% of this mayor’s social communication was directed at the criticism of certain political figures. Once more, the posts in question exhibit low productivity, but were nonetheless effective in eliciting reactions from followers, with an average of over 1,700 reactions per post. Conversely, the mayors of Syracuse and Ragusa recorded a relatively low average of reactions, at approximately 897 and 730 reactions, respectively (Figure 2). This is consistent with their communication style, which is more institutional and service-oriented, focusing primarily on the activities and interventions implemented by their administrations.

The communication of the mayor of Messina was characterised by a communicative emphasis directed at both the accusations made against the government regarding the management of the pandemic (13.7%) and the territorial controls adopted by the administration (24.1%). This strategy gave rise to policy debates that assumed the form of a referendum on the government. This frequently results in the emergence of an ‘us versus them’ dynamic, consistent with the personalisation of politics (Musella Reference Musella2020).

In his social media posts, the mayor of Messina combined emotional language with a more rational and pragmatic approach. He frequently employed an aggressive tone, utilising alarmist rhetoric to justify his stance on social security and public order. In this way, he presents himself as a guardian figure, defending the necessity of restrictions. This approach also gained him considerable support, as evidenced by the high level of engagement on his Facebook page, which had over 440,000 followers. During the initial phase of the pandemic, his posts received an average of 30,000 likes and over a million views. Furthermore, the mayor of Messina demonstrated the greatest propensity for the use of attachments that encompassed a plethora of multimedia formats, including images, videos, live feeds, documents and links. This proclivity for multimedia integration is exemplified by the mayor’s prolific deployment not only of images and videos, but also live feeds, thereby exhibiting a greater degree of engagement than other mayors.

In conclusion, the quantity of posts, the tone used, and the interaction patterns indicate the implementation of disparate strategies. Some mayors, including those of Palermo, Ragusa, and Syracuse, focused their messaging on highlighting the challenges posed by the pandemic, portraying it as an adversary whose defeat demanded compliance with stringent measures. Their objective was to cultivate acceptance and compliance with the established regulations. Conversely, the mayor of Catania employed a communicative strategy that presented the pandemic as an opportunity to reinforce community values within a framework of solidarity. He conveyed to citizens the necessity of a collective contribution to overcome the pandemic. Finally, the mayor of Messina utilised a highly personalised communication approach, in which he featured as the sole actor capable of addressing the crisis.

Policy strategy

In the initial phase of the emergency, the actions taken by our mayors were diverse and multifaceted. These included the implementation of measures to contain and counteract the spread of the coronavirus disease (Covid-19), the reorganisation of certain local services to ensure their continuity, and the introduction of initiatives to provide support to families or economic categories that were more vulnerable or disadvantaged as a result of the crisis. It is evident that innovative technologies were employed in the provision of services traditionally associated with face-to-face interaction. This included the utilisation of remote communication channels with families and citizens, telephone calls, and various forms of digital communication. These activities were organised in a variety of ways in both the cultural sphere (for example, virtual tours, online readings on institutional social networks, online literary appointments, digital bookshelves) and the social and educational spheres. In the latter, they related to two specific types of service: telephone helplines offer psychological support and counselling, and social and health assistance. Online platforms were also available to support pedagogical activities for children in municipal nurseries and preschools, as well as extra-curricular activities for elementary schoolchildren and secondary school adolescents.

In addition to these activities, several services have been identified that, despite the absence of any technological processes, were able to demonstrate the provision of effective and timely responses. The following fall under this category: the establishment of a special municipal current account for fundraising purposes; the collection of goods and foodstuffs to be distributed among families facing economic hardship, which did not fall under the purview of citizenship income; and home delivery of groceries and other essentials. It is also noteworthy to mention the reinforcement or reshaping of existing social welfare services, such as the strengthening of street units and services for the homeless. This included the provision of increased shelter facilities, the extension of time slots in night shelters, and the distribution of meals in day-care centres.

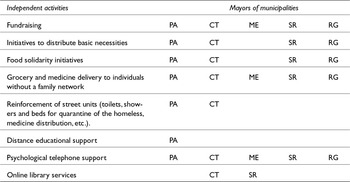

When considered at an individual administrative level, these initiatives appear to exhibit a high degree of homogeneity (see Table 3). This is particularly evident in services that were implemented during the initial stages of the pandemic, designed to address and support the basic needs of citizens. These comprised telephone helplines offering psychological assistance, home delivery services for groceries and medication for individuals with the greatest vulnerability, solidarity initiatives regarding food and basic goods, and fundraising.

Table 3. ‘Autonomous’ activities carried out by mayors

In terms of implementation, the documentary analysis highlights the consistent effort to identify local partners. In general, a significant portion of the services were initiated in collaboration with local associations and volunteers (food solidarity, telephone counters). Conversely, for other activities, the mayors facilitated the involvement of business owners and trade associations (e.g. distribution of medicines and food).

However, partners were engaged and mobilised in different ways. For example, the mayors of Catania and Syracuse exercised their formal authority, drawing the attention of the voluntary and third sectors by public notices inviting them to submit applications or enter into partnership agreements. For implementing welfare services (such as the delivery of essential groceries and medicines) as quickly as possible, mayors opted to establish collaborative relationships with social actors, following bureaucratic-administrative procedures and routines. In other words, this was carried out via instruments that, by their very nature, defined the object of work within the administrative and regulatory constraints of the institutional entity.

In contrast, the mayor of Palermo initiated proposals put forward by the voluntary and non-profit sectors, including the establishment of a central office for food distribution to individuals in quarantine or isolation and the recruitment of volunteers to assist with the support of those forced to remain at home due to the Coronavirus emergency. He assumed a leading role in the management and monitoring of these activities.

An additional distinction can be delineated in relation to the mayor of Ragusa. He initiated an agreement with the diocesan Caritas, formalising a ‘Pact of Widespread Solidarity’ in which the municipality assumed the role of control room. The objective was to extend the reach of the pre-existing welfare networks. The beneficiaries were individuals who are typically not served by social services or voluntary associations, including workers without social security benefits and individuals facing economic hardship in later life. In requesting the collaboration of Caritas, the mayor proposed an approach that was open to discussion and sharing, as well as to the participation of all local actors. This was to be achieved by establishing a social network which companies, associations, and private citizens who wished to offer necessities or welfare and volunteer services were to join.

Furthermore, an analysis of the documentation reveals a failure by the mayor of Messina to activate collaborations or agreements with the third or voluntary sector. Apart from a request for collaboration with the University of Messina to provide psychological support services and assistance, no other joint initiatives were introduced. It appears that the mayor delegated the whole responsibility of responding to the social emergency to the voluntary and non-profit sectors, particularly as far as the activation of welfare services beyond those explicitly indicated by the government was concerned.

The mayors becoae unquestionable protagonists, if we consider the number of emergency ordinances (limited to health or public health emergencies of an exclusively local nature) that they issued to control the spread of the pandemic. The mayor of Messina was the most prolific user of these ordinances, with 43 compared to 19 issued by the mayors of Catania and Palermo, and 9 and 6 by those of Syracuse and Ragusa, respectively. Indeed, the mayor of Messina even went beyond the provisions of the DPCMs. This latter aspect is particularly noteworthy in terms of the characterisation of the mayor’s activity. A significant proportion of the ordinances diverged from the directives set out in national decrees and regional norms, resulting in their subsequent annulment by the prefecture. In comparison, the utilisation of ordinances by other mayors is relatively limited, with less than a dozen in the case of the mayors of Ragusa and Syracuse and almost 20 in the case of the mayors of Catania and Palermo.

The aforementioned aspects led to the distinction between the strategies adopted by mayors according to the delegation of power. This distinction can be further refined by differentiating between those who acted through a collaborative approach (Stone Reference Stone1995) and those who reinforced a more top-down, command-and-control style of leadership (Getimis and Hlepas Reference Getimis, Hlepas, Bäck, Heinelt and Magnier2006). These two main dimensions of leadership gave rise to two distinct approaches: sensitivity to external relational capital and the need for control over policy processes (Hermann et al. Reference Hermann, Preston, Korany and Shaw2001). Rather than being mutually exclusive, these dimensions could be intertwined, and strategy styles can be interpreted as a continuum ranging from high polarity to low polarity.Footnote 5

By employing these two dimensions in our analysis, we can discern a heightened level of involvement in policy processes and a proclivity towards exerting personal control over these processes among the mayors of Ragusa, Palermo, and Messina. It is evident that only the first two mayors demonstrated a greater sensitivity to the perspectives outlined by external relational capital, as evidenced by their activation of operational tables and solidarity pacts. Regarding the other mayors, namely those of Catania and Syracuse, documentary analysis indicates a reduced need for direct control over policy processes. This is evidenced by the fact that both delegated the implementation of critical decisions to their officials or to external actors with whom they had established a relationship. Similarly, these two mayors also exhibited a low sensitivity to external relational capital, which is in line with the observations made about the mayor of Messina.

The conjunction of these two dimensions enables the identification of three distinct strategies of policy construction, which may be designated as ‘delegating’, ‘participatory’ and ‘self-oriented’ (Table 4). In the first case, we are concerned with the actions of mayors from Catania and Syracuse. These mayors demonstrated a lack of interest in forming partnerships and, more generally, in building networks for coordinating pandemic response policies. Additionally, they exhibited an unwillingness to exercise a top-down approach to controlling policy processes aimed at addressing the emergency. In the second case, we note mayors who evinced a strong propensity to involve networks and social actors, while simultaneously seeking to exert control over the policy processes they activated. Finally, we identify leadership that was indifferent to the mobilisation of social actors and which aimed to exert influence through control over policy processes.

Table 4. Typologies of policy strategies according to the complementary dimensions of need for control and relational context sensitivity

The interconnection between communication and policy strategies: towards types of leadership

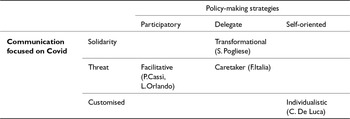

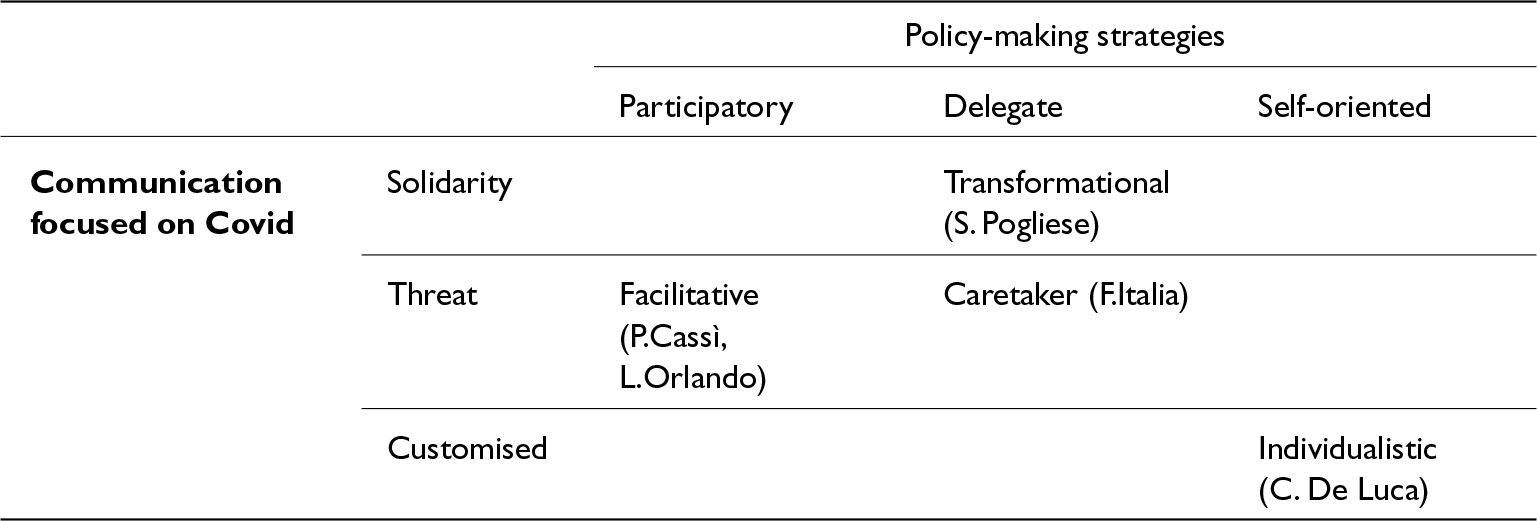

By integrating communication strategies with policy strategies, the primary action traits of mayors can be more clearly identified. These traits lead to some specific types of leadership: facilitative, transformational, caretaker, and individualistic styles (see Table 5).Footnote 6

Table 5. Leadership styles emerging from the intersection of policy-making strategies and communication focused on Covid-19

In the context of facilitative leadership, we draw upon the model delineated by Svara (Reference Svara2003) to identify a leader who takes charge of goal setting and policy formulation by bringing together a set of partners and citizens around a shared vision. This model is particularly applicable to the leadership trajectory adopted by Leoluca Orlando and Peppe Cassì, mayors of Palermo and Ragusa, respectively. In the latter instance, it is essential to underscore a proactive dimension that enhances the synergy between a participatory policy approach ‒ focused on fostering collaboration with the third sector to deliver services and address the crisis ‒ and a communication strategy primarily oriented towards empowering citizens to adhere to established regulations.

The case of the mayor of Syracuse is different. His leadership trajectory is that of a caretaker. The link between delegating policy style and the communication of a looming threat of a pandemic, he emerges as a figure who acts in accordance with the tenets espoused by Kotter and Lawrence (Reference Kotter and Lawrence1974), functioning as the ‘janitor’ of the community. Indeed, during the crisis, the mayor’s role was predominantly institutional in tone, and he showed a penchant for implementing strategies that did not engender a sense of possibility for change.

By contrast, the leadership of Salvo Pogliese, mayor of Catania, is characterised by a transformational style (Burns Reference Burns1978). When the delegating style of policy is considered alongside solidarity-oriented communication, it becomes evident that the mayor’s primary objective was to provide stability, trust, reassurance, and a sense of crisis control, rather than to adhere to the management of operational procedures. It appears that he was attempting to facilitate change in terms of crisis responsiveness by capitalising on the principles of solidarity and a sense of community. Finally, the mayor of Messina, Cateno De Luca, exhibited leadership characteristics that are distinctly individualistic. His self-oriented policy style and personalised communication style portray a leader who, during the crisis, utilised his role to project a strong self-image, capable of leading the community in an essentially autonomous manner. Notably absent is any indication of partnership or invitation to third sector organisations.

It is evident that the leadership styles exhibited by the mayors of these communities demonstrate the heterogeneity of the approaches employed by leaders in guiding their respective communities. Whilst the present analysis does not seek to evaluate the relative effectiveness of these approaches, it is important to note that there appears to be no direct correlation between the observed leadership styles and the epidemiological incidence of Covid-19. The data from the civil protection authorities for the initial four months of 2020 – the period examined in this study to assess leadership modalities – indicate that infection rates across the cities under consideration were remarkably similar. Specifically, except for Palermo, which exhibits an infection rate of 37%, the remaining cities display rates ranging from 40% (Catania and Ragusa) to 42% (Syracuse and Messina). The implementation of more restrictive measures or stricter enforcement of ordinances by certain mayors – such as those of Messina, Palermo, and Catania – does not appear to be justified by a significantly higher prevalence of the virus. Instead, it appears that these mayors strategically leveraged their leadership styles to influence public perception, thereby reinforcing their authority and role within the community. However, data concerning the approval ratings of mayors – serving as an indicator of their political performance – reveal that not all mayors were perceived favourably during the first year of the pandemic.Footnote 7

This phenomenon is particularly evident in the cases of the mayors of Catania and Palermo, who both experienced a decline in their popularity for re-election, which dropped by 13.4% and 8.2%, respectively. Conversely, the remaining mayors demonstrated favourable approval ratings, with the mayor of Messina notably achieving a substantial increase of 2.1% in citizens willing to re-elect him. In a similar vein, the mayors of Ragusa and Syracuse registered modest approval rate increases of 1.2% and 0.4%, respectively. In the case of the mayor of Messina, this increased approval rating is also corroborated by social media engagement metrics; as previously highlighted (see Fig. 2), Cateno De Luca had the highest number of followers and the greatest number of likes on his posts among the mayors considered. During the pandemic, these three mayors became the most ‘popular’ figures in the eyes of their public.

Despite the marked differences in leadership style exhibited by the two cases, a common characteristic is evident in their utilisation of communication strategies primarily aimed at territorial control and the provision of institutional support (see Table 2). This form of communication, herein referred to as service communication, encompasses information related to the functioning of essential services necessary to contain the contagion and facilitate access to economic and social assistance. Conversely, the mayors of Catania and Palermo participated less frequently in such communicative practices concerning the issue. Consequently, it appears that this specific mode of communication contributed significantly to shaping perceptions of reliable leadership and bolstering public trust in these officials. In summary, it appears that the mayors of Messina, Ragusa, and Syracuse predominantly conceptualised their roles in terms of ‘leading’ rather than ‘supporting’. This distinction is most pronounced in the case of the mayor of Messina, where, as previously noted, communication and policy strategies were primarily oriented towards emphasising authority and control, specifically, ‘who is in charge’. In contrast, the mayors of Syracuse and Ragusa appear to utilise communication strategies to consolidate their leadership roles by means of the formulation of regulatory and institutional frameworks.

Notwithstanding the differences, the overarching purpose of their communicative approaches appears to have been to mitigate public uncertainty. It is imperative to acknowledge that during the initial months of the pandemic, widespread confusion among citizens prevailed due to the presence of frequently conflicting information and locally specific regulations. This ambiguity hindered the provision of clear guidance on crisis management and effective measures to prevent contagion. The mayors were able to demonstrate a perceived mastery over the situation through their transparent communication of ongoing developments and necessary actions, thereby restoring public confidence in their leadership capacities.

Conclusion

The analysis of the case studies reveals a considerable degree of diversity in communication approaches and types of intervention. Regarding communication, analysis reveals that some mayors are keen to publicise the activities they are implementing, while others are interested in fostering a sense of intimacy with citizens. Finally, there are those who adopted a narrative based on self-promotion.

In comparison to the activities implemented, it is possible to distinguish between mayors who mobilise social actors and engage in network building; mayors who attach less importance to partnerships and who, simultaneously, have minimal interest in strengthening their top-down command-and-control approach; and finally, mayors who favour control over the (institutional) resources to be activated.

The conjunction of these heterogeneous modes of communication and policy strategies permits the elucidation of the potential coherences that may exist between them. This, in turn, offers a comprehensive perspective on the role exercised by mayors during the pandemic. A synthesis of these modes of communication and policy strategies reveals the presence of four styles of leadership: facilitative, caretaker, transformational and individualistic. This diversity extends beyond the conventional emphasis placed on various aspects of leadership, such as the use of power and the relationship with followers.

In particular, it becomes evident that there is a distinct approach to reconciling operational responses to the crisis, in terms of performance and services, with the necessity for communication aimed at fostering community acceptance of rigorous regulations and behaviour. It is evident that the solutions adopted by mayors did not always follow a similar path. This indicates that the type and purpose of communication were not always aligned with the approach to crisis response policy.

To illustrate this, the communication strategy of the mayor of Catania emphasised the reinforcement of feelings and values of solidarity and belonging to the community, whereas there was a lack of evidence of community involvement in the deployment of services and benefits. In contrast, the mayors of Ragusa and Palermo adopted an alternative approach. In their cases, there is a notable emphasis on community involvement in policy-making, but a distinct absence of such involvement in communication strategies. Instead, there is a pronounced emphasis on citizen empowerment through compliance with established regulations. Ultimately, the communication and policy approach of the mayors of Messina and Syracuse exhibited a notable degree of homogeneity, albeit along disparate trajectories. Indeed, if Cateno De Luca unified the two spheres of action through his personal charisma and exerted considerable influence with resolute determination, Francesco Italia, in contrast, directed both spheres from the institutional perspective, confining his actions to a role-oriented framework.

These different traits exemplify leadership in which the risks were considerably higher than in routine periods, due to the heightened awareness of citizens and the greater flexibility of institutional constraints on elite decision-making (Ansell, Boin, ‘t Hart Reference Ansell, Boin, t’Hart, Rhodes and t’Hart2014). Furthermore, the issue at hand is considerably more intricate than a mere combination of communicative and political strategies. However, the interconnection between the two domains of strategic action that we have analysed offers insights into the functioning of political leadership during crises.

It is evident from the findings of this study that a select group of mayors demonstrated an ability to garner the trust of their constituents. This phenomenon appears to be primarily rooted in the perception among citizens that the authorities are effectively monitoring the situation, rather than being based on compassion, empathy, or hope for the future. The ‘winning’ strategy is, therefore, more closely associated with a sense-making approach aimed at demonstrating the mayors’ ability to oversee, suppress, and contain the pandemic.

The leadership styles that have been identified in the present study include those that employ this strategy, which are characterised as facilitative-proactive, caretaker, and individualistic. These leadership styles are distinctly different from one another; however, they share a common feature in their communication focus, which is predominantly directed towards territorial control and institutional aid interventions. It is evident that such forms of communication have been effective in addressing citizens’ need for information regarding ongoing developments and necessary actions, thereby alleviating the uncertainty induced by the crisis.

This finding indicates that, in times of crisis, mayors must consider strategies that may not align with conventional leadership theories. These theories typically advocate for actions that are deemed resilient and capable of fostering social networks characterised by generosity and altruism. It appears that the most effective strategy during the current pandemic was the capacity to instil confidence through effective monitoring and control of the territory. Moreover, the findings of our research underscore the fact that different leadership styles can exhibit common or highly similar characteristics. This underscores the necessity to utilise leadership styles as ideal types, the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of which cannot be divorced from their relationship with citizens. It must be acknowledged that the utilisation of case studies does not permit the drawing out of generalisations. Nevertheless, the research calls for further consideration of the necessity to identify additional analytical categories for the study of crisis leadership. This finding emphasises the necessity for additional research to be conducted on the role of mayors’ crisis leadership, encompassing the exploration of diverse leadership styles in a range of crisis scenarios.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Patrizia Santoro is research fellow in Political Sociology, in the Department of Political and Social Sciences, University of Catania, where she has taught ‘Complex organisations and local government’. Her research focuses on public institutions, bureaucracies, local government and political leadership. Recently, she has also been working on election campaign strategies in Europe and political communication. Her recent publications include: ‘Pubblica amministrazione e digitalizzazione: una relazione controversa’, Rivista di Sociologia del diritto, 2025; ‘The modernization of public administration between public employment policies and digital innovation’, with M. La Bella, International Journal of Public Administration, 2024; ‘The pandemic crisis, Italian municipalities and Community Resilience’, with R. Sampugnaro, Partecipazione e Conflitto, 2021.

Rossana Sampugnaro is Associate Professor in Political Sociology and Political Communication at the University of Catania. She is a member of the PhD programme in Political Science at the same institution and the coordinator of the Jean Monnet Module EuREact. The primary focus of his research is the study of electoral behaviour and the evolution of electoral campaigns, with a particular emphasis on issues of election integrity and the risks of profiling. His most recent publications include a monograph on Abstentionism for Mondadori (2024) and Saving the Elections. EU Strategies to Fight Disinformation in the Age of Post-truth Politics, written with Hans-Jörg Trenz, Comunicazione Politica (1/2024).