1.1 Introduction

Climatic variations have led to repeated glaciations on the Earth. Especially, the Pleistocene glaciations have left many visible traces on the Earth’s surface in the form of moraines, striated bedrock, erratics, etc. The Earth’s response to the load redistributions of water, ice and sediments on the surface is termed glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA), (Wu & Peltier, Reference Wu and Peltier1982). Due to the nature of GIA several present-day observations can be related to the last glaciation, which peaked between 26 ka BP and 18 ka BP (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Dyke and Shakun2009). The most prominent process is the ongoing land uplift of formerly glaciated areas such as Fennoscandia, North America and Patagonia.

A generally less appreciated GIA effect is crustal stress release that occurs during and after deglaciation and that can reactivate pre-existing faults and weakness zones through earthquakes. The shaking from these earthquakes can cause landslides and soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDS) (Fenton, Reference Fenton, Hanson, Kelson, Angell and Lettis1999; Munier & Fenton, Reference Munier, Fenton, Munier and Hökmark2004; Olesen et al., Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004; Lund, Reference Lund and Beer2015). Meanwhile, a wealth of such observations is available from around the world, which will be discussed in Chapters 11–21 of this book. Research focused until very recently on Northern Europe, i.e. Lapland, and eastern North America, but stress release due to GIA is now suggested in and around other formerly and presently glaciated areas as well (Brandes et al., Reference Brandes, Steffen, Steffen and Wu2015). Some studies additionally discuss fault reactivation during the advance of an ice sheet (Munier & Fenton, Reference Munier, Fenton, Munier and Hökmark2004; Brandes et al., Reference Brandes, Polom and Winsemann2011; Pisarska-Jamroży et al., Reference Pisarska-Jamroży, Belzyt and Börner2018).

Several terms have been used to describe GIA-related stress release in the literature (see e.g. Fenton, Reference Fenton, Hanson, Kelson, Angell and Lettis1999; Lund & Näslund, Reference Lund, Näslund, Connor, Chapman and Connor2009). Perhaps the most common term is postglacial faulting, and the reactivated faults are consequently called postglacial faults (PGFs). This term might have similarities with, but is not connected to, the term postglacial rebound (PGR), a term generally used until the late 1970s to describe the land uplift after the last glaciation. However, the word postglacial in PGF does constrain events to the time period after the glaciation.

Peltier and Andrews (Reference Peltier and Andrews1976) introduced the term GIA, which encompasses PGR but also effects prior to deglaciation (i.e. during glaciation) and any consequent processes such as geoidal, rotational and sea-level changes as well as any corresponding effects due to stress changes. Hence, postglacial faulting is also encompassed by the nowadays widely accepted term ‘GIA’. Fenton (Reference Fenton, Hanson, Kelson, Angell and Lettis1999) considered the term ‘postglacial faulting’ unsatisfactory because it implies a temporal constraint and omits the fault genesis. He suggested that the terms glacio-isostatic faulting or glacial rebound faulting to be more suitable for faulting due to GIA. Nonetheless, postglacial faulting was still used in the literature but understood in a much broader temporal sense, e.g. also applicable to faulting occurring during glacial advance. Lund and Näslund (Reference Lund, Näslund, Connor, Chapman and Connor2009) introduced the term glacially induced faulting and correspondingly glacially induced fault (GIF) for the reactivated fault. Especially the latter term, GIF, has been increasingly used in the last decade to describe the faults although the ‘classic term’ PGF has been retained by many researchers, especially when referring to the prominent faults in Northern Europe (Figure 1.1). Another term that was discussed among the community is glacially triggered faulting (GTF) and thus glacially triggered fault. The term arose because ‘induced’ was interpreted by some researchers as meaning either new fault generation (rather than fault reactivation) or faulting associated with human activity, such as anthropogenic earthquakes. For others, GTF is simply the same as glacially induced faulting.

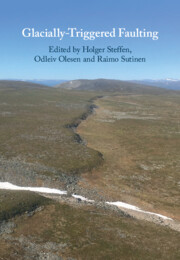

Figure 1.1 Oblique aerial photograph (SE view, taken from Olesen et al., Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004) of the fault scarp developed along the Máze Fault System constituting the central part of the Stuoragurra Fault Complex in Norway. The fault segment is located approximately 10 km to the NNE of the Masi settlement. Groundwater is leaking from the foot of the escarpment (lower right).

In this book the reader will find that all terms except glacially triggered fault have been used, depending on the taste of the authors. The interchangeable terms glacially triggered faulting, glacially induced faulting and postglacial faulting refer to the mechanism, whereas glacially induced fault and postglacial fault refer to the reactivated fault. Nonetheless, we encourage use of glacially triggered faulting or GTF when referring to the mechanism and glacially induced fault or GIF for the reactivated fault.

Glacially triggered faulting should not be confused with glaciotectonics, which is mostly the near-surface deformation of sediments and sometimes bedrock as a direct consequence of ice movement and which sometimes shows similarities with potential GTF features such as faults and SSDS. We refer the reader to Chapter 4, by Müller et al., who discuss the differences of glaciotectonics and GTF in detail.

Next, we discuss classification criteria for a GIF. This is followed by a brief history of major findings on GTF and the latest developments.

1.2 Classification Criteria for a Glacially Induced Fault

Given the heterogeneous structure of Earth’s lithosphere, it is necessary to define criteria for correctly identifying a GIF and distinguishing it from the vast number of other faults around the globe. Such criteria were introduced by Mohr (Reference Mohr1986) and have been modified and expanded by Fenton (Reference Fenton1991, Reference Fenton1994). The six original criteria of Fenton (Reference Fenton1991), briefly summarized, were as follows: (1) a fault must be continuous with a prominent disruption of pre-existing geological units; (2) its scarp face should not be affected by ice or meltwater; (3) it is not generated due to differential erosion; (4) it must displace late Quaternary/Holocene sediments or morphological features (e.g. shorelines); (5) it is not generated due to differential compaction; and (6) it should be trenched to ensure fault activity and determine erosional influence. Features 1 and 4 categorize the geological structure; features 2, 3 and 5 exclude other processes; and the last is a rather technical note on investigation methods. The latter was removed by Fenton (Reference Fenton1994), who established seven criteria (e.g. Fenton, Reference Fenton, Hanson, Kelson, Angell and Lettis1999; Munier & Fenton, Reference Munier, Fenton, Munier and Hökmark2004) and which we repeat verbatim, except for the addition of ‘F’ to the numbering, for clarity in the discussion to come:

F1. Faults should have demonstrable movement since the disappearance of the last ice sheet within the area of concern.

F2. The fault should offset glacial and late-glacial deposits, glacial surfaces or other glacial geomorphic features. Preferably, it should be demonstrated that the fault displaces immediately postglacial stratigraphy and/or geomorphic features, though it need not cut younger features.

F3. Fault scarp faces and rupture planes expressed in bedrock should show no signs of glacial modification, such as striations or ice-plucking. Limited glacial modification, however, may be present on scarps that are late-glacial or inter-glacial in age.

F4. Surface ruptures must be continuous over a distance of at least 1 km, with consistent slip and a displacement/length ratio (D/L) of less than 0.001.

F5. Scarps in superficial material must be shown to be the result of faulting and not due to the effects of differential compaction, collapse due to ice melt, or deposition over pre-existing scarps.

F6. Care must be taken with bedrock scarps controlled by banding, bedding, or schistosity to show that they are not the result of differential erosion, ice-plucking, or meltwater erosion.

F7. In areas of moderate to high relief, the possibility of scarps being the result of having been created by deep-seated slumping driven by gravitational instability must be disproved.

Muir Wood (Reference Muir Wood1993), in work contemporary to Fenton’s, provides five classification criteria in the form of a checklist. They can be briefly summarized, following Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Sundh and Mikko2014), that:

M1. a displaced sediment layer must have been formerly continuous;

M2. this sediment offset must be directly related to a fault;

M3. the ratio of displacement to length should be less than 1:1,000;

M4. the displacement should be consistent along the fault; and

M5. the movement should have occurred synchronously along the fault.

These can be considered as a more specific refinement of F1, F2 and F4 criteria listed earlier. The M1–M5 checklist has been applied in several dedicated studies, see e.g. Olesen et al. (Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004), Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Sundh and Mikko2014) and Brooks and Adams (Reference Brooks and Adams2020). Olesen et al. (Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004) merged the M1–M5 checklist with a revised form of the F1–F7 criteria.

As research progresses, new findings warrant a discussion of the criteria, most notably criteria M3 (which is equivalent to F4) and M5. Therefore, we introduce revised classification criteria for GIFs. These are modified from the criteria listed earlier and for easier application expressed as a checklist like that of Olesen et al. (Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004). We comment on each criterion and thereafter discuss previous criteria that should no longer be considered definitive.

The herein revised classification criteria are as follows:

1. Disruption of a formerly continuous geological feature: There is either an offset of an originally continuous surface or of sediment layer(s) which can be seen on the surface in an outcrop or in seismic reflection profiles, and/or there is an internal disturbance of a sediment, e.g. in the form of soft-sediment deformation structures (SSDS).

Comment: This criterion revises, combines and extends F2 and M1. Previously, the disruption of a sediment unit was generally thought to be by a fault or fault scarp (F1, F2 and M1). However, SSDS also can be generated due to glacially triggered earthquakes along GIFs (e.g. Munier & Fenton, Reference Munier, Fenton, Munier and Hökmark2004; Müller et al., see Chapter 4), and thus should be added. The age of the sediment (see F1 and F2, e.g. ‘since the last ice sheet’, ‘glacial’ or ‘postglacial’) is of lesser importance because previous glaciations could have led to GIFs, and under certain conditions faults can be reactivated during ice advance (see Steffen et al., Chapter 2). Smith et al. (see Chapter 12), also hypothesize that some recognized GIFs were reactivated by glaciations that occurred prior to the most recent one.

2. Relation to a fault that shows demonstrable offset: A fault with noticeable offset can be connected to the disrupted feature (fault, fault scarp, SSDS, etc.). This fault is the GIF.

Comment: We merge F1 and M2 and rephrase.

3. Consistent displacement: There is a reasonably consistent amount of slip along the length of the GIF.

Comment: This is M4 and parts of F4. This criterion can be easily applied to GIFs with surface exposures. For faults with only indirect evidence of reactivation, e.g. with SSDS, this must be verified with appropriate methods (trenching, geophysical techniques); see e.g. Beckel et al., in Chapter 7, and Gestermann and Plenefisch, in Chapter 6.

4. Relation to a formerly glaciated area: The disturbed feature is found within or near to a formerly glaciated area.

Comment: As clearly indicated by its name a GIF can be found within a formerly glaciated area. However, the GIA process also affects the region surrounding the ice sheet, most notably the peripheral bulge area. This area extends a few hundred kilometres around the ice sheet and is affected by glacially induced stress changes (Wu et al., Chapter 22). GIFs can thus occur in such a peripheral region, e.g. the Osning Thrust in Germany (Figure 1.2) as suggested by Brandes et al. (Reference Brandes, Steffen, Steffen and Wu2015). Therefore, we suggest adding this criterion to highlight that GIFs are not limited to the formerly glaciated area. Earlier criteria assumed that GIFs were only to be found within the formerly glaciated area. In other words, the ‘area of concern’ of criterion F1 is extended by understanding the physics of GIA.

5. Convincing exclusion of trigger mechanisms other than GIA: As other processes are also able to reactivate faults or generate features that can mimic GIFs, those processes must be meticulously excluded in order to clearly confirm a GIF as such. Hence, investigation must convincingly demonstrate that there are:

no signs of gravity sliding as the driving mechanism for fault activity in areas of sufficient relief;

no signs of glacial modifications of fault scarps (especially those in metamorphic rocks controlled by schistosity, banding or bedding) implying glacial erosion (differential erosion or ice-plucking) was the cause;

no signs of collapse due to melting of buried ice, differential compaction or deposition over a pre-existing erosional scarp resulting in an apparent offset in overburden;

in case of SSDS, no signs of other processes, e.g. mass movements, landslides, groundwater-level fluctuations, hydrostatic pressure changes related to lake drainage, water-wave or tsunami passage.

Comment: These are reformulated criteria F3, F5, F6 and F7 (among others), mainly following the criteria list in Olesen et al. (Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004). They are combined into a single criterion to provide a checklist. The last point of this criterion concerning SSDS has been added because these structures are a common feature in the recent literature linked to glacially triggered earthquakes.

Figure 1.2 Glacially induced faults (GIFs, black lines and dots, uncertainty ‘A’ in Munier et al., Reference Munier, Adams and Brandes2020), probable GIFs (dark grey lines, uncertainty ‘B’ in Munier et al., Reference Munier, Adams and Brandes2020), suggested GIFs (light grey lines, uncertainty ‘C’ in Munier et al., Reference Munier, Adams and Brandes2020) and selected locations of suggested palaeoseismicity (light grey dots) in Northern and Central Europe. Ice limits from DATED-1 (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Gyllencreutz, Lohne, Mangerud and Svendsen2016). B – Bollnäs, ![]() – Børglum, L – Lansjärv, Lv – Lauhavuori, P – Pärvie, Pa – Palojärvi, R – Röjnoret, RI – Rügen Island, So – Sorsele, St – Stuoragurra.

– Børglum, L – Lansjärv, Lv – Lauhavuori, P – Pärvie, Pa – Palojärvi, R – Röjnoret, RI – Rügen Island, So – Sorsele, St – Stuoragurra.

These five criteria must all be fulfilled for a fault to qualify as an (almost) certain GIF. There is no longer an age constraint, so GIFs are not limited to just the most recent glaciation and the times shortly before and after local deglaciation. Appropriate investigation methods must be ensured, of course, so that especially criterion 5 is convincingly fulfilled.

We suggest that two previously used criteria, M3 (= F4) and M5, be removed from the list of required criteria, but they might be useful as additional considerations:

1. Displacement ratio: The ratio of (usually vertical) displacement to overall length of the fault normally should be less than 1:1,000. For most GIFs this ratio is between 1:1,000 and 1:10,000.

Comment: This is criterion M3, which can be used for surficial faults like the prominent GIFs in northern Fennoscandia. However, Muir Wood (Reference Muir Wood1993) and Fenton (Reference Fenton1994) already noted that this is not a necessary requirement, e.g. because mechanical behavior of some fault materials hampers the development of prominent fault scarps. The Lansjärv Fault in Sweden (Figure 1.2) has a ratio higher than 1:1,000 (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sundh and Mikko2014) and is thus an exception. This criterion would also limit the term GIF to structures that can be clearly identified on the surface. However, erosional processes and human activity, among other events, in and near formerly glaciated areas, especially those areas around the edge of the former ice sheets where the ice retreated 10,000 years earlier, may have buried, removed or leveled (parts of) surface traces of GIFs (see Sandersen & Sutinen, Chapter 3). Brooks and Adams (Reference Brooks and Adams2020), for example, argue that the surficial fault traces of the 1989 Ungava earthquake in Canada (average surface offset of 0.8 m; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Wetmiller, Hasegawa and Drysdale1991) are likely no longer visible today. Consequently, this criterion appears too strict.

2. Synchronous displacement: Reactivation of the fault affected the entire fault.

Comment: This is M5. It was originally listed to allow an estimation of earthquake magnitude (Raymond Munier, personal communication, 2020). The criterion is also rather strict and was omitted by Olesen et al. (Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004). Recent dating results by Olesen et al. (see Chapter 11) show that each of the three systems of the Stuoragurra Fault Complex was reactivated at different times.

Muir Wood (Reference Muir Wood1993) introduced a grading scale for qualifying an observation as neotectonics in view of all information and any uncertainties. This scale is also applied to the GIF database of this book (Munier et al., Reference Munier, Adams and Brandes2020), but the wording of the scale is slightly altered: the five grades are kept, but neotectonics is replaced with GIF:

A. Almost certainly a GIF

B. Probably a GIF

C. Possibly a GIF

D. Probably not a GIF

E. Very unlikely a GIF

This scale has been used recently by Brooks and Adams (Reference Brooks and Adams2020) to classify Eastern Canadian GIF claims. The ‘classic’ postglacial faults in Northern Europe are usually classified as A. Many claims, especially at the edge of and outside the former ice sheet, are currently of grade B or C, mainly because they are not yet fully investigated and thus do not fulfill all classification criteria. Some earlier claims in the literature are classified as D or E when newer investigations could not support the initial claim; see e.g. Olesen et al. (Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004). It is therefore fully possible that many currently B- or C-graded claims will receive a D or E after additional investigations in the future or will no longer be listed as GIF. For tracking of claims, we suggest removed claims be documented (ones which can be considered ‘F. Not a GIF’) together with a rationale for their removal. In turn, a small fraction of D- and E-graded faults may be elevated to A or B after more investigation.

1.3 Brief Historical Overview until the Early 2000s

Munier and Fenton (Reference Munier, Fenton, Munier and Hökmark2004) provided the only previous history of global GTF research. Their review included peer-reviewed publications and limited-distribution reports as well as conference abstracts and personal communications. Some regional overviews were compiled for the Northern European faults (see corresponding Chapters 11–14 for references) and for a few other areas, for example, by Firth and Stewart (Reference Firth and Stewart2000) for the British Isles and by Fenton (Reference Fenton1994) for Eastern Canada and the Eastern United States, here updating work by Oliver et al. (Reference Oliver, Johnston and Dorman1970) and Adams (Reference Adams1981). The work by Fenton (Reference Fenton1994), for example, lists 173 publications. Clearly, our review cannot address all previous studies. In the following, we limit ourselves to the most important contributions, although even those might be different for other researchers. More information can be found though in this book’s chapters. Section 1.4 summarizes the developments of the last decade that gave rise to this book.

In the history of GTF research one must distinguish between (i) studies that discuss GTF and use one of the terms (mainly postglacial faulting) mentioned above, (ii) studies that discuss GTF but do not name it as such and (iii) studies that use the term postglacial faulting or similar to describe another process. Fenton (Reference Fenton1994) points to Mather (Reference Mather1843) as an early describer of a postglacial faulting feature, which is not named as such. The term was used by Matthew (Reference Matthew1894) for the first time. Then, in the late nineteenth/early twentieth century, GTF was widely recognized in investigations of postglacial geomorphic features in Eastern Canada and the Northeastern United States (Munier & Fenton, Reference Munier, Fenton, Munier and Hökmark2004). However, most of those features have very small offsets. Also, in Europe the term ‘postglacial faulting’ was used for small features (e.g. Brøgger, Reference Brøgger1884; Reusch, Reference Reusch1888; Munthe, Reference Munthe1905), interestingly, far away from the Lapland Province with its prominent, but then-undiscovered, GIFs.

1.3.1 History in Lapland

Tanner (Reference Tanner1930) noticed a 10-metre offset in raised shorelines along northern Rybachy (Fisher) Peninsula north of the Kola Peninsula (Figure 1.2) that could be related to fault reactivation in postglacial times. Interestingly, he noted (p. 316) that postglacial faulting in Fennoscandia was not being considered by geologists, and thus no active searches for postglacial faults were conducted. Tanner followed up with a discussion of literature containing hints of GTF all over Fennoscandia. He concluded that although little was known at the time (1930), one should be open to the fact that GIF features could exist anywhere in Fennoscandia where land uplift was occurring.

GIFs were not recognized in Fennoscandia until Kujansuu (Reference Kujansuu1964) discussed remarkable structures in north-western Finland. Since the mid-1970s investigations in Fennoscandia were intensified, especially related to nuclear waste disposal plans, and provided an almost constant stream of new GIF discoveries. Lundqvist and Lagerbäck (Reference Lundqvist and Lagerbäck1976) informed about the Pärvie Fault west of Kiruna, Sweden, and Olesen (Reference Olesen1988) recognized the Stuoragurra Fault in Finnmark, Northern Norway. Lagerbäck and Sundh (Reference Lagerbäck and Sundh2008) listed about 15 GIFs or fault systems that were identified by the mid-2000s. Many of these GIFs were initially found and mapped with the help of aerial photographs. Some of them, the Lansjärv, Sorsele and Röjnoret faults, were investigated in greater detail with additional trenching (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Roberts and Smith2017). Arvidsson (Reference Arvidsson1996) estimated that the moment magnitude of earthquakes generating the faults could have reached Mw = 8.2. Seismic networks in the Nordic countries were installed and extended through the 1980s and ‘90s and slowly provided a clearer picture of current seismicity around the GIFs (see Gregersen et al., Chapter 10). The dating of the rupture activity was firstly relative to local deglaciation or to land uplift if the highest shoreline was higher than the elevation of the fault, as direct dating, e.g. with cosmogenic (scarps), luminescence (scarp sediments) or radiocarbon (included organic material) methods had not yet been performed (Lagerbäck, Reference Lagerbäck1992; Lagerbäck & Sundh, Reference Lagerbäck and Sundh2008). For more information on investigations in Finland, Norway and Sweden prior to the early 2000s, the reader is referred to Kuivamäki et al. (Reference Kuivamäki, Vuorela and Paananen1998), Olesen et al. (Reference Olesen, Bungum, Lindholm, Olsen, Fredin and Olesen2013) and Lagerbäck and Sundh (Reference Lagerbäck and Sundh2008), respectively. Karpov (Reference Karpov1960) mentioned traces of postglacial tectonic faults in the Khibiny Mountains on the Kola Peninsula, but more detailed investigations in NW Russia did not start until the late 1980s (see Nikolaeva et al., Chapter 14).

1.3.2 History Outside of Lapland

Away from Lapland no GIF had been described, although an overview of studies by Mörner (Reference Mörner2005), for example, lists more than 20 different locations all over Sweden that suggest palaeoseismic activity in relation to ice retreat and land uplift – but without identified surface ruptures. Lund et al. (Reference Lund, Roberts and Smith2017) reviewed two of these (Iggesund and Stockholm), which are based on disturbed sediments, and they could not find clear evidence that would further support these findings. Among the 60 claims in mainland Norway reviewed and graded by Olesen et al. (Reference Olesen, Blikra and Braathen2004, Reference Olesen, Bungum, Lindholm, Olsen, Fredin and Olesen2013), no potential GIF was discovered in Southern Norway.

In parallel with and as a consequence of Lapland research, suggestions for GIFs were presented for Scotland (see e.g. Fenton, Reference Fenton1991, for an overview), Northern Ireland (Knight, Reference Knight1999) and Ireland (Mohr, Reference Mohr1986). The claims were subject to discussion: Stewart et al. (Reference Stewart, Firth, Rust, Collins and Firth2001) question whether there is any significant postglacial movement on faults in western Scotland, while Munier and Fenton (Reference Munier, Fenton, Munier and Hökmark2004) point to limitations in the Irish studies. A detailed analysis and re-evaluation of the many claims for the British Isles is still pending.

In other parts of formerly glaciated Europe or in its near vicinity, GIFs were not found, but palaeoseismicity or fault reactivation due to GIA was suggested (e.g. Van Vliet-Lanoë et al., Reference Van Vliet-Lanoë, Bonnet, Hallegouët and Laurent1997). Gregersen et al. (Reference Gregersen, Leth, Lind and Lykke-Andersen1996) speculated about local reactivation of the northern boundary fault in the Sorgenfrei–Tornquist Zone at the time of deglaciation. Potential palaeoseismic traces were found in Rügen Island (Ludwig Reference Ludwig1954/55) and in the Baltic countries (see Bitinas et al., Chapter 18), but these assertions were not confirmed by more detailed field investigations at the time.

Research regarding GTF was sporadically conducted in North America and much material was published (Fenton, Reference Fenton1994). As in Europe, investigations peaked in the 1970s and ‘80s (see summary in Adams, Reference Adams1996). A strong earthquake (![]() ) on 25 December 1989 in Ungava Peninsula produced the first known historical surface rupture in formerly glaciated eastern North America (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Wetmiller, Hasegawa and Drysdale1991, Reference Adams, Percival, Wetmiller, Drysdale and Robertson1992). It is sometimes speculated that GIA was the cause, but it is very unlikely the event would have fallen within a period of glacially influenced seismicity (Brooks & Adams, Reference Brooks and Adams2020). On another note, Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Sleep, Geller, Wang and Kroeger1979) attributed earthquakes in Baffin Island and adjacent Baffin Bay to basement faults reactivated by GIA.

) on 25 December 1989 in Ungava Peninsula produced the first known historical surface rupture in formerly glaciated eastern North America (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Wetmiller, Hasegawa and Drysdale1991, Reference Adams, Percival, Wetmiller, Drysdale and Robertson1992). It is sometimes speculated that GIA was the cause, but it is very unlikely the event would have fallen within a period of glacially influenced seismicity (Brooks & Adams, Reference Brooks and Adams2020). On another note, Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Sleep, Geller, Wang and Kroeger1979) attributed earthquakes in Baffin Island and adjacent Baffin Bay to basement faults reactivated by GIA.

Claims of GTF in North America outside its north-eastern quadrant are rare and often refer to regions with other possible trigger mechanisms, like plate margin deformation and/or volcanism in Alaska (Sauber et al., see Chapter 20), the Sierra Nevada (Greene, Reference Greene1996) and western Wyoming (Byrd et al., Reference Byrd, Smith and Geissman1994; Hinz et al., Reference Hinz, Carson, Gardner and McKenna1997) or the failed Reelfoot Rift system with the New Madrid Seismic Zone (Grollimund & Zoback, Reference Grollimund and Zoback2001). These make it difficult to distinguish the GIA contribution to potential fault reactivation and earthquakes.

Some GIFs have been proposed in other parts of the world where ice sheets or larger ice masses were or are present, like Greenland, Iceland and Antarctica, but no GIF has been confirmed to date. An overview of claims can be found in Steffen and Steffen in Chapter 21.

Despite the considerable number of confirmed GIFs and an increasing number of claims, the underlying mechanism remained unknown until Johnston (Reference Johnston1987) introduced the concept of earthquake suppression due to earthquakes and increased activity after deglaciation using the Mohr-Coulomb failure theory (as reviewed by Steffen et al. in Chapter 2). This concept also accounted for the low seismicity of Greenland and Antarctica. Wu and Hasegawa (Reference Wu and Hasegawa1996a,Reference Wu and Hasegawab) explained the mechanism using finite element modelling of the GIA process (see Wu et al., Chapter 22), and their predicted timing of glacially triggered earthquakes is in reasonable agreement with GIF observations.

In the early 2000s investigations of GIFs continued at varying pace in countries with GIFs or claims of GIFs. In the British Isles, investigations ceased, while nuclear waste authorities in Canada, Sweden and Finland supported on-going investigations. Scientific interest has again increased in the last decade due to several circumstances, which we will illuminate next.

1.4 Recent Developments

Several countries like Sweden, Finland and Norway nowadays generate new elevation models with the help of light detection and ranging (LiDAR) (see Palmu et al., Chapter 5). Inspection of the new data in the early 2010s led to the discovery of the Bollnäs Fault in central Sweden (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sundh and Mikko2014). LiDAR facilitated more detailed investigations and increased the number of GIFs in Sweden as well as the length and complexity of those already mapped (Mikko et al., Reference Mikko, Smith, Lund, Ask and Munier2015; Lund et al., Reference Lund, Roberts and Smith2017; Smith et al., see Chapter 12). Similarly, in Finland LiDAR reconnaissance has revealed new faults, e.g. the Palojärvi Fault in the north (Sutinen et al., Reference Sutinen, Hyvönen, Middleton and Ruskeeniemi2014) and Lauhavuori in Southern Finland (Palmu et al., Reference Palmu, Ojala, Ruskeeniemi, Sutinen and Mattila2015). Additionally, detailed trenching across the scarps has provided evidence of non-stationary seismicity and occurrence of multiple slip events even before the Late Weichselian maximum (see Sutinen et al., Chapter 13).

A dedicated program in Finland enabled dating of multiple independent landslides (see Sutinen et al., Chapter 13). Ojala et al. (Reference Ojala, Markovaara‐Koivisto and Middleton2018) reported, based on landslide dating, that some Finnish faults are younger than previously thought and that they had ruptured several times. Similar results were reported from Sweden (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Grigull and Mikko2018; and in this book, see Chapter 8). Recently, dating results from the Stuoragurra Fault Complex showed much younger ages than expected (at least 6,000 years after the end of deglaciation) and that the segments of the fault ruptured at different times (Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Olesen and Høgaas2020; see also Olesen et al., Chapter 11).

Several new studies argue for GIFs south of the Lapland Province. Jacobsson et al. (2014) suggested a normal-faulting GIF at the bottom of Lake Vättern in southern Sweden, though there are no traces of this fault on land (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Roberts and Smith2017). Hence, this finding must be questioned, and further investigations are still needed. Brandes et al. (Reference Brandes, Steffen, Sandersen, Wu and Winsemann2018) collected multidisciplinary material that points to postglacial activity of the Børglum Fault in northern Denmark and thus strongly advocated for it being a GIF. Their study is consistent with several others that suggest GTF in Denmark (see Sandersen et al., Chapter 15).

Glacially triggered faulting at the edge of the former ice sheet has been suggested by several groups by analyzing SSDS in Germany (Brandes & Tanner, Reference Brandes and Tanner2012; Hoffmann & Reicherter, Reference Hoffmann and Reicherter2012; Pisarska-Jamroży et al., Reference Pisarska-Jamroży, Belzyt and Börner2018), Poland (van Loon & Pisarska-Jamroży, Reference van Loon and Pisarska-Jamroży2014) and Latvia (van Loon et al., Reference van Loon, Pisarska-Jamroży, Nartišs, Krievāns and Soms2016). Pisarska-Jamroży et al. (Reference Pisarska-Jamroży, Belzyt and Börner2018) further claimed to have found evidence for GTF on Rügen Island during the last glacial advance. Based on geological and numerical analysis of the Osning Thrust in Germany, Brandes et al. (Reference Brandes and Tanner2012) suggested this to be the first GIF discovered outside of the glaciated area. In subsequent studies, it was suggested that even historical (Brandes et al., Reference Brandes, Steffen, Steffen and Wu2015) and recent deep crustal earthquakes in Germany (Brandes et al., Reference Brandes, Plenefisch, Tanner, Gestermann and Steffen2019) are due to GIA. Brandes et al. (Reference Brandes, Steffen, Steffen and Wu2015) further noted that GTF in Germany due to the Weichselian ice sheet might affect even the northern parts of Central Germany. A summary of these new findings and additional evidence for GIFs at the edge and outside the former ice sheet can be found in Müller et al., in Chapter 16, Pisarska-Jamroży et al., in Chapter 17, and Bitinas et al., in Chapter 18.

In Canada, no certain GIF has yet been determined (see Adams & Brooks, in Chapter 19). However, sub-bottom profiling surveys in eastern Canadian lakes reveal a large number of mass transport deposits pointing to early postglacial seismic shaking due to GIA (Brooks & Adams, Reference Brooks and Adams2020). In view of these findings and because of availability of new data imagery sources (such as LiDAR), Brooks and Adams (Reference Brooks and Adams2020) predict further discoveries of GIF candidates in Canada can be expected in the future.

Based on an increased amount of seismic data in Antarctica, Lough et al. (Reference Lough, Wiens and Nyblade2018) discovered more earthquakes beneath the ice than previously thought. The authors concluded that Antarctica’s seismicity compares to that of the Canadian Shield. They further hypothesized that tectonic intraplate stresses could accumulate long enough over time, and once the suppressing GIA stress has been overcome, seismicity increases and then Antarctica behaves like a typical intraplate area without ice.

In parallel with new field observations, modelling of GTF has progressed. Hetzel and Hampel (Reference Hetzel and Hampel2005) introduced a finite element model with a fault structure that showed the behaviour deduced by Johnston (Reference Johnston1987), but in the finite element model constant slip is predicted before and after glaciation. Steffen et al. (Reference Steffen, Wu, Steffen and Eaton2014) developed a so-called GIA-fault model, which extends the model from Wu and Hasegawa (Reference Wu and Hasegawa1996a,Reference Wu and Hasegawab) with a fault surface and which yields fault slip in a finite amount of time. Such new model development benefitted from progress made in stress modelling (see Gradmann & Steffen, Chapter 23).

Finally, after more than a decade of planning, drilling into the Pärvie Fault has been tentatively scheduled within the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP) (Kukkonen et al., 2011; Ask et al., see Chapter 9). The professional community is very curious about any results this drilling will produce; for example, whether it can confirm that the Pärvie Fault is apparently not moving on the surface as found by Mantovani and Scherneck (Reference Mantovani and Scherneck2013).

1.5 Conclusions

More than two dozen fault scarps a kilometre-plus in length have been identified in northern Fennoscandia since the 1960s and ‘70s, when extensive investigations began. Their identification is nowadays made easier with the help of LiDAR images. These scarps are categorized as GIFs. Comparable structures were also described in the British Isles and Eastern Canada. In other formerly glaciated areas in Europe – e.g. the southern parts of Sweden, Norway and Finland, the southern Baltic Sea, Denmark, Northern Germany and Poland, and the Baltic countries – GIFs were seldom recognized, but the number of studies with reliable field evidence has considerably increased in recent years. But their estimated fault displacements are not as large as those in northern Fennoscandia. There are also other areas in the world where GTF may play a role, such as northern Alaska, some Arctic islands, the Alps (Jäckli, Reference Jäckli1965) and Patagonia (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley and McCulloch2005).

As well as the many new (potential) GIF discoveries and features that point to glacially triggered seismicity, fault reactivation has been identified by dating events on several Fennoscandian GIFs. The results show that at least some of the scarps were generated during more than a single event, and for some it is hypothesized that part of the displacement happened before the last glaciation (see Chapter 12, by Smith et al.).

In view of the many new findings a necessary revision of the well-known classification criteria of Fenton (Reference Fenton1994) and Muir Wood (Reference Muir Wood1993) is suggested. The revised criteria are provided in checklist form. Since research is always progressing, we forecast that future findings may lead to further revision(s) of these criteria. Lastly, all these new findings have strong implications for the role of glacially induced faulting on intraplate seismicity. This will be discussed in Chapter 24 by Olesen et al.