In a world where academic thought has entered digital platforms, we are increasingly called to understand the diverse ways in which public scholarship manifests itself today. Curiously, a broad theme of “post-scholarship” has been explored by some academics, wishing to approach professional expertise from different public angles. For instance, in the call against the emergence of what they dubbed “Post-Scholar America,” professors Keisha N. Blain and Ibram X. Kendi advocated for public scholarship “that touches lives far beyond the walls of academe.” Notably, for Blain and Kendi, the idea of a “post-scholar” nation holds a markedly negative connotation since it presumes the dissolution of academic thought and expert knowledge in the wake of fake news and populism, reinforced due to the lack of professional commitment to public scholarship.Footnote 1

Beyond the expressed concerns on the lack of committed public scholarship, the growing opportunities offered by the Internet economy have drastically impacted traditional approaches to university labor itself. Some practicing academics have thus begun to directly participate in entrepreneurial activities online, hybridizing their university careers by starting personal website blogs. An environmental scientist and a “side-blogger,” Erin, for example, launched her website project called PostScholar in 2020, which serves as an online repository of “free resources and confessionals related to life beyond school.”Footnote 2 Erin’s website both covers “insider career confessionals” and functions as “a living blog,” aimed at those “working in private- and public-sector jobs” and seeking personal development.Footnote 3

In my view, what unites these two very different accounts is their clearly expressed desire to move beyond the academy, whether through promoting committed public scholarship or hybridizing academic labor online. As these stances reflect, the idea of “post(-)scholarship” implies a form of public intellectual engagement outside the academic establishment, at once carrying problematic and productive potential. On my end, I would like to take on the concept “postscholarly” to define what I see as a substantial transformation of literary humanities in the public social platform era. I specifically understand the notion of postscholarly criticism as a non-expert form of public humanities practice, equally tied to digital culture(s)/social platform economy and university education. However, as opposed to post-professional labor, postscholarly criticism refers to a public form of genuinely popular intellectual expression divorced from the professional concerns of institutionalized humanities. Therefore, the questions of who exactly is engaged in such a practice today and what implications it may have for the public (literary) humanities are central to this essay.

I would like to bring to scholarly attention that popular social platforms are now increasingly utilized by author-critics with academic experience or “professional profile” from the humanities and other, adjacent disciplines.Footnote 4 Recently, the video essay genre has become a popular, public form of intellectual authorship that explores academic contexts online. I argue that the production of such popular intellectual content allows authors across the globe to significantly expand and transform the public understanding of literary humanities by exposing vast audiences to themes, concepts, authors, and concerns that they have studied during their time spent in the university. As I will show, the video essay often accommodates diverse individual authors and national communities, signifying a new, qualitative development of global digital popular critical authorship.

To understand what this postscholarly digital phenomenon is, how it fits into the essay genre’s history, what global influence it may have, and whether it can inform us about future approaches to the public literary humanities, I offer a conceptual analysis of the popular video essay genre from YouTube. First, I will address the existing scholarly engagements with popular cultural intellectual production and theorize the new era of postscholarly criticism. Second, I will contextualize the video essay genre by showing its hybrid scholarly and public history. Third, I will illustrate relevant “central” examples of postscholarly video essays, landing on their global, “peripheral” circulation. And, finally, I will touch on the issue of disciplinarity and the relationship between today’s public literary humanities and potential future directions for the professional discipline.

1. The new era of postscholarly criticism

Historically, many prominent scholars have advanced the idea that various cultural communities and groups outside of official institutions can produce other kinds of “intellectual” knowledge. These conceptualizations chiefly belong to the “post-Cultural studies” scholarship, as expressed in the works of Dick Hebdige, Lawrence Grossberg, Iain Chambers, and John Fiske.Footnote 5 These authors theorized the subcultural, urban popular cultural, and fan communities vis-à-vis their spectacular semiotic and distinctively “intellectual” forms of expression, while Bertolt Brecht’s famous essay, “Emphasis on Sport,” had already argued for the consideration of sport spectatorship as a specifically “intellectual” cultural phenomenon in the first half of the twentieth century.Footnote 6 However, later scholarship on this subject within fan studies installed a conflation between early fan/Internet communities and their supposedly “theoretical” or “scholarly” interpretative practices. For instance, Henry Jenkins argued that select fans of cultural texts challenge “the dominant mode of academic criticism,” or that transgressive fan communities produce “other kinds of theories”; Jonathan Gray advanced the notion of “anti-fans,” describing people who actively dislike cultural texts “that have not been viewed” as those engaged “in distant reading”; and Paul Booth coined the term “fan-scholar research,” referring to the process of online verification and confirmation of “all the narrative kernels” that fans may find in the original text, “just as if they were researching an academic tome.”Footnote 7 Thus, if British Cultural Studies investigated cultural expressions of working class and subcultural youth communities alongside the post-WWII boom in college education in England, fan studies scholars seem to have merged their own disciplinary interests with the interests of various non-scholarly groups.

Counter to this trajectory, I argue that digital postscholarly critical authorship is a recently emerged global phenomenon. I see the contemporary public postscholarly criticism as part and parcel of the academy’s historical diversification and its economically induced loss of authority and prestige. First, the gradual expansion of the university in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries introduced vast numbers of new academic entrants to the enterprise, which significantly diversified its functioning. Second, the diversification of this exclusionary and elitist environment later coincided with the advancement of “the entrepreneurial university” in the 1990s, which now found itself one among many other business industries, thus losing its traditional claim to the autonomous and authoritative pursuit of knowledge.Footnote 8 In turn, professional humanities have become significantly less attractive for aspiring young professionals and college graduates who wished to capitalize on their received knowledge and degrees without, at the same time, investing in the highly competitive, precarious, and much less publicly visible academic labor market. Describing Anglophone digital video essayists as “post-academic intellectuals,” Steven Proudfoot observes that many are academic dropouts who “present their academic credentials as something that they wouldn’t recommend or are helping others avoid.”Footnote 9 Indeed, some digital creators explicitly reflect on their former or ongoing student status without holding the university establishment itself in especially high esteem, particularly due to its uncertain career prospects. Still, the academy offers them symbolic intellectual dividends: these author-critics commonly use the scholarly essay structure and devote attention to the matters of the humanities, often using scholarly concepts, theoretical tools, and methods to interpret popular cultural works.

Simultaneously, unlike trained academic professionals, digital video essayists do not exclusively explore humanities scholarship but also represent lived human interactions with the cultural, social, political, and digital public world, inclusive of personal engagements with different aesthetic mediums and cultural trends. The approximate range of topics and themes commonly explored by the digital video essayists include—though are not limited to—audiovisual artistic and aesthetic works (from film, television, and video games to visual art); (proto-)mass cultural literature (from Gothic novels and detective fiction to contemporary romance); popular culture as a lifestyle (from twentieth-century subcultures to digital esthetics); arguments that are trending or commonly debated in the digital realm, and so on. As this list implies, YouTube video essays range from analyzing specific cultural objects to general ideas, all of which are unambiguously connected to conversations about popular culture.Footnote 10 This development recalls the original premise of Jürgen Habermas, who argued that Western art criticism as a form of conversation fostered a civic mode of public deliberation in the eighteenth century.Footnote 11 Curiously, the postscholarly digital video essay likewise stems from the amateur expressions originating in public conversational forums. Therefore, the immense popularity of the essay form in the digital global world today at least partially correlates with its historically amateur, public, and thus everyday communicative (rather than formalized, institutional) functioning.Footnote 12 Considering this dualism, I suggest taking a closer look at the tension between the scholarly and public modes of the video essay.

2. Between disciplinarity and publicity: the genre’s origins

At first glance, the video essay genre is directly derived from the discipline of film studies, which is occasionally acknowledged by its mainstream YouTube practitioners. For example, the Canadian digital author-critic Lily Alexandre argues that

video essays have existed for decades, but they really kicked into overdrive with the YouTube algorithm. For most of their history they were an academic medium used in film studies for obvious reasons. You know, if you’re talking about an interesting camera movement, [it is] better to show it than describe it. Video has more tools to create meaning than text alone does; you can use not only visuals but vocal intonation, music, even things like the timing of cuts (Figure 1).Footnote 13

Figure 1. Alexandre’s main example of a cinematic video essay is the YouTube channel Every Frame a Painting (“Art Won’t Save Us,” 17:08). This image shows the channel’s co-creator, Tony Zhou, reworking the scenes and snapshots from Orson Welles’ F for Fake (1973) as an illustration of his own approach to the video essay genre, tied to the visual interweaving of different storylines through montage (“F for Fake,” 3:27).

However, the American digital author-critic Shanspeare relates the video essay practice to the “argumentative essay” commonly “assigned in school,” simultaneously adding that “academic papers are a mere dot in the vast constellation of the essay universe” (Figure 2).Footnote 14 I argue that the reason for these two different assessments concerns the fact that the scholarly video essay and literary essay are themselves hybrid in nature, which is why I suggest turning to the genre’s hybridized academic and public origins.

Figure 2. Shanspeare’s outline of the three types of conventional essays: narrative, expository, and personal (“Discourse Fatigue,” 11:29).

On the one hand, essay films emerged in the early twentieth-century experimentations with cinematic narrative through new editing techniques and montage, with various formulas later advanced by French critics and filmmakers like Alexandre Astruc’s caméra-stylo (“camera-pen”) or Agnès Varda’s cinécriture (“film-writing”).Footnote 15 The logic of creating cinematic work as being “analogous to the way in which a novel (or any other literary work) is created on paper by a writer” gained special traction in the mid-twentieth century, embedded in the works of prominent avant-garde European film essayists like Chris Marker and Harun Farocki.Footnote 16 Crucially, the essayistic works of German-speaking writers from Georg Lukács to Theodor W. Adorno became foundational for many European and American film essayists since the 1960s (Figures 3 and 4).Footnote 17

Figure 3. The start of analysis in Farocki’s “Song of Ceylon,” where he argues that the early film invents its own language outside the traditional literary medium (“Harun Farocki,” 17:15–17:35).

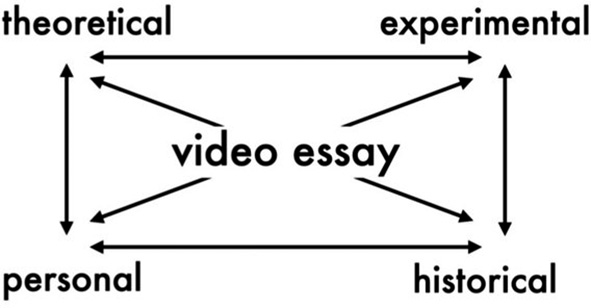

In the early twenty-first century, the academic disciplines of film and media studies underwent changes as the affordances of multimedia and digital technologies prompted film scholars “to invent new audiovisual critical forms.”Footnote 18 Building off Astruc’s concept, media scholar Eric S. Faden, for instance, coined the term “media-stylos,” which referred to experimentations with the ways in which “traditional scholarship might appear as a moving image,” emphasizing the participatory role of students in producing and experimenting with “new forms, genres, and techniques.”Footnote 19 Cinephile, academically minded video essays broke into prominence in the 2010s via video-sharing sites such as Vimeo, YouTube, MUBI, and Fandor, and the online journal [in]Transition. Footnote 20 Daniel Schindel stresses that video essays from these platforms generally emerged out of “the world of film-focused academia,” which explains their concern “with some kind of analysis and/or criticism.”Footnote 21 However, a film scholar and a founding co-editor of [in]Transition, Catherine Grant, reported on her investment in these “creative forms of digital remix” as a way to “analyze films and their affects” in a “performative” rather than strictly “critical” sense (Figure 5).Footnote 22 For media theorist and experiential video essayist Johannes Binotto, the contemporary video essay traverses “both what is usually understood as proper academic methodology and what we are accustomed to in artistic practices,” theorizing its “multidimensional tension field” in a diagram (Figure 6).Footnote 23 Broadly sharing Binotto’s approach, I will further illustrate that today’s postscholarly video essays lie on their own loose axis of popular humanities research and creative digital production (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 4. Continued analysis in Farocki’s essay film. This work is one of the essay-features he made for the German TV program “Telekritik” during the 1970s.

Figure 5. A snapshot from Melanie Bell and Catherine Grant’s video essay “Making Fiction Flow” exploring “film continuity and the life and work of script supervisor Penny Eyles” (03:12).

Figure 6. Binotto’s diagram theorizing the “multidimensional tension field” of video essays.

Figure 7 Binotto’s visualization of the tension between literary writing and filmmaking in his lyrical video essay titled “trembling line [on Agnès Varda’s cinécriture],” (1:29–2:15)

Figure 8. The theoretical sources used by Binotto in his “trembling line” (1:29-2:15).

On the other hand, the public and conversational nature of the digital popular video essay recalls the historical functioning of its earlier, nonacademic prototype—the modern public literary essay. The Western eighteenth-century periodical genre of the essay was marked by its “involvement with the public sphere of private individuals,” representing the evolution of the professional writer from the court and parliament.Footnote 25 In this context, Habermas points at the early genre of “moral weeklies” in England, which constituted periodical essays that “were still an immediate part of coffee-house discussions” and therefore retained “proximity to the spoken word.”Footnote 26 Speaking of the early art critic (Kunstrichter), Habermas notes that “it was not an occupational role in the strict sense”: the former “retained something of the amateur; [and] his expertise only held good until countermanded.”Footnote 27 It was only upon the arrival of professional society in the mid-nineteenth century that the metric of qualification emerged, which distinguished “the professional man from the amateur,” with the modern university playing a key institutional role in this process.Footnote 28 Nevertheless, since, as Adorno observed, the essay form still historically relates to rhetoric “in its adaptation to communicative language,” it automatically resists a positivistic and scholarly “order of ideas.”Footnote 29 Thus, the introduction of the essay into nineteenth-century grammar schools in the form of so-called “themes” was marked by the parameters of “strict style, grammatical correctness, and organized thinking,” which were largely antithetical to the pre-modern essay’s “exploratory, wandering spirit.”Footnote 30 Despite the eventual incorporation of the essay structure into the center of general college and university education worldwide, the genre’s modern conversational, amateur, and subjective impetus remains largely at odds with its contemporary institutional practice.

In the more recent technological context, the amateur and public direction of the socially platformed video essay also has much to do with pre-digital cultures’ exploration of various mediums for self-expressive purposes. On the level of production, the “amateur video” fits into the long history “of vernacular creativity—the wide range of creative practices (from scrapbooking to family photography to the storytelling that forms part of casual chat).”Footnote 31 And, while the amateur bourgeois multimedia production has been traced to at least the beginning of the nineteenth century, the emergence of the VHS and VCR technologies in the second half of the twentieth century dramatically expanded the creative and expressive capacities of those who would consider themselves amateur authors and fans.Footnote 32 Arguably, these amateur explorations of new audiovisual technologies gradually amounted to “a distinctive form of cultural commentary” due to their employment of novel remixing technical strategies.Footnote 33 As John Rieder observes, “the techniques of serial linkage, episodic rationing, and strategic interruption” have already characterized “mass cultural narrative” since at least the early twentieth century, but the advent of the Internet has invited numerous “professional and amateur players to appropriate, edit, and combine [different mediums’] samples into new versions” on an unprecedented scale.Footnote 34 Much YouTube audiovisual content is likewise “predicated upon the viewer/user’s reappropriation and recontextualization of existing televisual and film material.”Footnote 35 Today’s digital author-critics indeed remix, (re)appropriate, and recontextualize relevant audiovisual and textual materials from television series, films, and literary fiction with occasional self-broadcasting and advertising, which allows them to produce unique marketable forms of public criticism.

Finally, returning to the specifics of the contemporary postscholarly video essay, its distinctive feature concerns its engagement with the world of the humanities. As I have already suggested, today’s postscholarly critics do not merely analyze literary works and critical concepts but explore the much larger terrain of culture familiar to them. And, given their academic background, the evolution of the literary discipline in the Anglophone academy arguably has had a direct influence on postscholarly criticism. It is well known that the developments of the second half of the twentieth century drastically affected the “formalist” approaches to studying literature in the university, causing literary forms to be understood in the broader cultural, social, and political contexts.Footnote 36 The pronounced influence of the British Cultural Studies and their intellectual precursors on the American academy in particular contributed to the situation wherein literature started “to seem too narrow an object to be viewed in isolation from other social forms,” which informed the national disciplinary struggles toward “becom[ing] cultural” by the 1990s.Footnote 37 One of the results of this intellectual transmission was the substantial diversification of literary humanities in terms of the variety of texts, concerns, mediums, and audiences it started addressing. While this history is well accounted for, digital postscholarly works demonstrate both the influence and the transformation of the contemporary academic literary humanities on YouTube, ranging from Western to local indigenous digital publics around the globe.

3. Postscholarly digital video essay from center to periphery

A direct precursor to today’s video essay practice may be considered the Anglophone counterculture, often interchangeably labeled as either “LeftTube” or “BreadTube,” which emerged on YouTube as a left-wing response to alt-right uses of digital media in 2010s.Footnote 38 This loose countercultural phenomenon has been described as “a core group of academically minded YouTubers that produce high-concept material with high production values.”Footnote 39 As one of the digital critics observes, “leftist” digital authors on YouTube “left academia in order to pursue their online careers” because “the Internet was recognized by the New Left to be the new marketplace of ideas” and the “domain in which to connect with a far larger and intersectional audience.”Footnote 40 The genre of the video essay was particularly favored by these original LeftTubers, leading to them being coined as “social media critical scholars (SMCSs),” a term describing “any YouTube content creator who produced scholarship video essays with a critical lens.” By innovating “[the] scholarly genre of [the] video essay,” SMCSs arguably pose and research “open-ended questions through the collection and analysis of evidence and use of a critical theoretical perspective.”Footnote 41

When I started to engage with popular video essays post-BreadTube, one surprising feature became exceedingly clear: often, both creators and audiences deem these digital pieces as authorized extensions of academic scholarship. For instance, in the video essay characteristically titled “The Era of The Critic,” Shanspeare suggests that video essays are “becoming almost better than academia—…more accessible and attracting so many people” because “we are young, we talk like young people and come from backgrounds as well that aren’t too elitist,” which Shanspeare argues speaks for the genre’s “relatability” (Figure 9).Footnote 42 Shanspeare’s meta-video essay, which explores video essays on YouTube and the genre’s advancement after BreadTube, gathered a symptomatic assembly of comments: thus, @annw7843 observes that video essays “are open access, and [that] everyone knows old academics scoff[] at anything which can be accessed by anyone and not just people paying access to journals”; @ava.catherine links “the rise of video essays” “to people turning away from traditional academia because it feels unattainable,” suggesting that this genre is “attractive” “because the people making them seem more accessible than a ‘professor’”; @moelblackx stresses the presence of “the new age academia” in the digital world; @flowersandperfume355 asserts that “video essays…are just as good as those fancy academic journal articles”; or, as @hllurban244 states, “this sort of discourse around the video essay being low brow or not worthy of an academic title reflects how academics and elite people” once reacted to how the printing press “worked to democratize publishing” (Figure 10).

Figure 9. The snapshot of Shanspeare’s “The Era of The Critic” featured in Kidology’s meta-video essay (“Why BREADTUBE,” 16:33).

Figure 10. One of the chapters from “The Era of The Critic” (1:55).

It is notable that most of these assessments are painted in pronounced “counterdiscursive” and even “heretical” hues: in other words, their articulated resistance to the authorized world of academic learning is explicit.Footnote 43 Simultaneously, the appreciation of the intellectual capital that YouTube’s video essays transmit to viewers is equally present in these accounts. This begs at least a few questions: first, what is it about video essays that successfully conveys their publicly authorized intellectual status? And, second, may we consider them genuinely public explorations of (literary) humanities?

A straightforward answer to the first question is that these creators commonly rely on the academic essay structure and/or scholarly sources from the literary humanities disciplines to supply or even construct their argumentative claims (Figure 11). For example, in the video essay “The Nymphet Femme Fatale (As Popularized by Misreadings of Lolita),” American author-critic Yhara zayd uses an academic source as the guiding mechanism for her larger argument: that Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Lolita was misinterpreted by American literary critics, who promoted “the nymphet femme fatale” trope before it entered the realm of popular culture. Importantly, zayd combines a scholarly inspired discussion of literary fiction with an analysis of contemporary popular cultural tropes and esthetic trends that may resonate with today’s broad online audiences (Figures 12 and 13).Footnote 46

Figure 11. The thumbnail from zayd’s “The Nymphet Femme Fatale.”

Figure 12. “Lolita: Solipsized or Sodomized?” by Peter J. Rabinowitz used by zayd to substantiate her main argument (2:35–3:32).

Figure 13. The snapshot of Lolita (Dolores Haze) portrayed by Sue Lyon in Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of Lolita (1962), remediated by zayd (1:08).

Following a similar approach, Canadian digital author-critic and Ryerson University graduate, Broey Deschanel, explores the topic of “low culture adaptations,” wherein she examines multiple cinematic popular cultural adaptations of Shakespeare’s works and argues that “Shakespeare was never meant to be high culture” (Figure 14).Footnote 44 Historically, as Deschanel elaborates, “we’ve come to associate Shakespeare with what scholars like to call ‘high culture,’” linking his works “with the upper classes, things society has deemed to have aesthetic value” and to be “inaccessible to the masses.”Footnote 45 Counter to such belief, Deschanel argues that the “youth pop culture renditions” of Shakespeare’s plays “taught us that Shakespeare is for everyone,” directly building her arguments off scholarly works such as Emma French’s Selling Shakespeare to Hollywood (2006) or Theater and Film (2005) by Robert Knopf (Figure 15).

Figure 14. The intertitle in Deschanel’s video essay is superimposed on the scene taken from a popular film adaptation of Shakespeare, Romeo + Juliet (1996) (7:15).

Figure 15. Robert Knopf’s analysis of Shakespeare’s popular adaptations integrated with another scene from Romeo + Juliet (10:02).

One of the most globally recognized American video essayists, Natalie Wynn/ContraPoints, analyzes the popular fictional romance saga Twilight from her own postscholarly lens, interweaving psychoanalytical, queer, and radical feminist theory with the discussion of the saga, other literary fictional works, and gender issues in contemporary Western society. Notably, Wynn pursued a PhD degree at Northwestern University without graduating.Footnote 47 ContraPoints’ video essay rests on the premise that “the obsessive moral policing of the romance genre” constitutes “centuries of ‘concern’ that women are reading the wrong kinds of books,” which informs her discussion of the romance genre from Samuel Richardson’s Pamela or Virtue Rewarded to Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight. Footnote 48 Curiously, ContraPoints’ approach follows in the footsteps of scholarly works such as Tania Modleski’s Loving with a Vengeance and Janice Radway’s Reading the Romance, both of which advanced the discussion of the romance genre from feminist perspectives (Figure 16).Footnote 49 Symptomatically, beyond conducting cultural critical analysis, ContraPoints devotes most of this near 3.5-hour video essay to feminist psychoanalytic theory and feminist historical movements, which are meant to express her personal stance on feminism, identity, and gender representation in contemporary Western society (Figure 17).

Figure 16. The popular romance genre book covers contextualize ContraPoints’ analysis of Twilight (13:34).

Figure 17. ContraPoints’ “list” of queer and radical feminist theory that guided the production of her video essay (18:10–18:15).

Another set of examples of postscholarly video essays relates less to the analysis of popular cultural fictional works but instead concerns explorations of the digital social platform environment itself through concepts taken from humanities scholarship. In his aesthetically provocative video titled “The Work of Art in the Age of Surveillance Capitalism,” Irish author-critic Brendan Morris meditates on Walter Benjamin’s famous essay and Michel Foucault’s concept of panopticon in respect to social media content production. Describing his work under the video, Morris characteristically states: “In this video, I attempt to articulate what might be called ‘a critique of the political economy of content creation’ wherein I examine the base of social media as profit-generating for private and corporate owners, and how that shapes the super-structural panoptic algorithm which in turn maintains the base of cultural production.”Footnote 50 Implicitly recognizing it as postscholarly content, one of the commentators under the video observes: “for anyone who thinks this is meant to be a tell-all video essay, you’ll be disappointed—it poses a lot [of] interesting points in a gloriously, visually energising way and should be used as a springboard into your own continued research” (@ossiepattinson7944) (Figure 18).

Figure 18. The title of Morris’ digital video essay, strategically positioned at the end of the piece (14:16).

On the visual level, Morris’ artistic essay represents a fast-paced sequence of moving images, elaborately crafted collages with quotations taken from the works of Karl Marx, Foucault, Benjamin, and others, as well as shifting depictions of famous artworks, cinema characters, and YouTube vloggers superimposed on each other through a deliberate use of montage and filmic cuts. The central artwork that binds these elements in Morris’ essay is Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), which illustrates the ideas of coercive brainwashing and surveillance in the age of digital capitalism (Figures 19 and 20). A postscholarly video essay like this often balances its conceptual dimension—its scholarly order of ideas—with intellectual and creative freedom, aimed at publicly expressing one’s social, cultural, and political concerns, which helps its author to symbolically escape the domain of professional academic scholarship.

Figure 19. Artistically recombined images from Morris’ essay (10:01-11:40).

Figure 20. These collages function as Morris’ critical statement on social media production in the age of digital surveillance (10:01–11:40).

While Morris’ essay is clearly positioned on the more rigorous end of public intellectual analysis, my next example illustrates a more accessible conceptual approach to commenting on the digital environment. A popular American digital creator of Vietnamese descent, Mina Le, whose video essay has received over 1 million views on YouTube, explores the topic of subcultures and contemporary digital esthetics.Footnote 51 In her video essay, Le studies the meaning of the term “subculture” and dives into the Western history of subcultural movements, including the academic scholarship on this topic. She specifically points to the origins of the subcultural theory springing from the Chicago School, stressing that “a lot of femme-centric subcultures were not considered threatening or taken seriously enough to be researched by academic and journalistic institutions.”Footnote 52 Le also accounts for the Birmingham School of cultural theorists who analyzed “the new working-class youth subcultures such as teddy boys, mods, skinheads and rockers in post-WWII Britain” (Figures 21 and 22).Footnote 53 She further transitions onto the main topic of the video essay: marketable fashion esthetics, which are popular in the social platform environment, stressing that while “[a] lot of subculture styles are resistance styles in the way that they challenge the mainstream,” “nowadays, the mass media and the rise of fast fashion have limited the ability of young people to use their clothes as the tools of a cultural revolution” (Figure 23).Footnote 54

Figure 21. The visualization of Le’s engagement with the Centre for British Cultural Studies (CCCS) through a series of photographs capturing the post-WWII subcultures (4:00-4:05).

Figure 22. The second image from Le’s essay features the rockers (4:05).

Figure 23. The ‘evolution’ of the subcultures in the digital age, as represented by the viral esthetics on TikTok: “mermaidcore” on the left; “tomato girl”—on the right (18:01).

What is particularly striking about Le’s account is the direct correlation she makes between subcultural academic scholarship and its bearing on contemporary digital esthetics. Le explicitly aligns with subcultural theory’s conception of style as a form of subcultural resistance, which is why she sees the contemporary fetishization of esthetics online as the result of their co-optation by mainstream institutions and corporations. Crucially, Le is a digital creator herself, which is why the topic of digital esthetics has an immediate bearing on her own craft.

My last example in this section concerns the commentary on the digital environment directly built on a literary critical source—Rita Felski’s contentious The Limits of Critique (2015). In the video essay titled “How Critique Corrupted the Pleasure of Reading,” the video essayist Robin Waldun wonders whether negative literary critique has had an overwhelming influence on digital cultural criticism.Footnote 55 Waldun, who has recently received an undergraduate degree from the literary department at the University of Melbourne, follows Felski in arguing that late twentieth-century “high” theories resulted in the promotion of “professional pessimism,” which he also sees in the “oppositional tendencies” of popular video essays.Footnote 56 By making this direct connection between academic and digital criticism, Waldun announces the general “resurgence of social critics on Substack, on Instagram, on TikTok,” proclaiming the return of the “age of critique” on online forums (Figures 24 and 25).Footnote 57

Figure 24. The thumbnail from Waldun’s video essay semi-ironically depicts the lineage between the professional criticism of the 1980s (embodied in the image of Susan Sontag; on the left) and contemporary video essays represented by digital critics like himself (shown on the right).

Figure 25. Felski’s notion of “professional pessimism” integrated into Waldun’s stance on video essays (12:05).

Waldun’s example seems crucial to me in one respect: he does not at all distinguish academic criticism from mainstream social media commentary. And, in my view, it shows the tendency of young authors who produce digital public content toward adopting scholarly inquiry by making it subservient to issues in the digital environment. Thus, while Felski wrangles with the limits of professional critique within the literary discipline, Waldun denounces negative digital communication, advising his public viewers to focus more on passion and enjoyment in consuming and producing digital content.

Overall, these examples fit the definition of postscholarly criticism: they may not deal with the disciplinary matters of professional criticism but still mobilize relevant academic research, approaches, and theory to extended public discussions of popular cultural texts, personal experiences, and the digital environment. Moreover, by blending academic scholarship with their subjective explorations of contemporary culture and the social world, most popular video essayists have gained publicly authorized intellectual status. In turn, we may consider all these video essays to be representative of genuinely public humanities work because they broadly explore the role of human intellectual inquiry in a lived social platform environment.

Going further, it is essential to move beyond the narrow context of the Western content creators to understand whether such popular intellectual work resonates with different global authors. Historically, the essay film itself is a “transnational genre,” which “provides filmmakers with a way to escape the symbolic circuits inherent in their national cultures and connect with a broader social and political world” (Figure 26).Footnote 58 Moreover, as Edward Said famously observed, “Like people and schools of criticism, ideas and theories travel.”Footnote 59 However, a part of this message uneasily resonates with today’s complex digital pathways of global intellectual transmission. More broadly, such complexity manifests in the disjointed global digital market itself, wherein, despite assurances to the contrary, “center-periphery hierarchies and differences in scale” remain intact.Footnote 60 How such problematic center-periphery relationships play out on global social media platforms is fundamentally impacted by unequal local access to these online spaces and advertising sponsors, the differences in language acquisition, national state censorships, and so forth. However, given this essay’s narrow scope, I will merely observe that the postscholarly video essay has received a degree of intellectual transmission among non-Western digital critical practitioners.

Figure 26. A shot from Chris Marker’s essay film “The Koumiko Mystery” (1965), which documents the life of a Japanese woman, Koumiko Muraoka, who moved to Japan after growing up in France (11:04).

Since digital media content tends to spread across platforms, some of the prominent YouTube video essayists have extended their digital critical activity to social platforms like Substack.Footnote 61 Spreadability, as Jenkins, Ford, and Green state, occurs in “a world where mass content is continually repositioned as it enters different niche communities.”Footnote 62 Characteristically, some authors on Substack converse with the popular video essayists and the broad left-leaning message promoted by the original BreadTube community. Thus, the author of the channel “Ad Hoc,” Arden Yum, has recently interviewed Le and another user, Ochuko Akpovbovbo, about cultural and racial voices unequally represented on the platform.Footnote 63 A YouTube video essayist herself, Yum ruminates on the questions of race and identity in her Substack post and also points at the heightened national specificity of the platform, observing that “Substack centers American culture, which centers whiteness.” One of Yum’s interviewees, Germany-based Akpovbovbo, corroborates her account: “I seldom read Substack essays because I can’t relate at all. I am not American, I don’t live in America. The fact that the content and culture discourse is so similar is sometimes stifling—because, whose culture?” In other words, both Yum and Akpovbovbo wish Substack “were more international.”Footnote 64

As we shall see, the apt question of “whose culture?” can be equally applied to the digital video essay from YouTube. My first example concerns a Serbia-based author Dinara, with a YouTube pseudonym bazazilio, who released an Anglophone video essay about the genre of romance.Footnote 65 In her earlier video, Dinara narrates how she fled her home country, Russia, due to its full-scale invasion in Ukraine in 2022 (Figure 27).Footnote 66 In her essay, bazazilio tells the audience about her work experience as a literary fiction reviewer in Russia in 2014, pitching English-language books “to a major Russian publishing office.”Footnote 67 While narrating her professional experience, bazazilio notes that one of the erotic novels under her review was shocking to her at first because of its explicit and problematic content, a sentiment also shared by her superiors. Over time, however, as bazazilio reports, she came to recognize the importance of “popular sexual fantasy” and the “unhealthy” ways in which “our societies teach us” about consent.Footnote 68 Symptomatically, bazazilio’s quotations from academic sources such as Barbara Fuchs’ Romance (2004) or Eva Illouz’ Hardcore Romance (2014) are complemented by her direct reference to the arguments made in ContraPoints’ “Twilight,” which she recommends to her audience (Figure 28).Footnote 69 Given the contemporary Russian state’s promotion of “traditional values” and the related (self-)censorship activities of book publishers, bazazilio’s video essay strongly reads as a conscious rebuke of the repressive climate of her native publishing industry. Thus, while her essay generally discusses the global genre of romance and the transgressive fantasies it promotes, bazazilio’s personal experience problematizes this discussion within her local non-Western context.

Figure 27. The thumbnail from bazazilio’s video essay.

Figure 28. An example of bazazilio’s usage of a scholarly source from her video essay (37:04).

Further, the non-Anglophone examples of postscholarly video essays on YouTube exist as well. By focusing on the local intellectual decolonizing project, the Central Asian online research collective from Kazakhstan, Horizon, produces cinematic video essays on related subjects, such as Aidana Amanzholova’s “The Last Sufi Dervish” (Figure 29).Footnote 70 Similar to the trend I identified in the Anglophone video essay context, Amanzholova’s multilingual video essay embraces a counterdiscursive stance toward both academic research and the cultural film industry. The narrator in this video essay ruminates both on the Soviet gaze, which portrayed Kazakh culture as the “oriental other” through state-produced films, and on Western-centric academic scholarship, which exoticizes Kazakh heritage. In short, while this last example clearly differs from the personalized Western content, this local decolonizing project similarly uses the video essay form as a critical intellectual and potentially popular tool of national cultural expression (Figure 30).

Figure 29. «Соңғ сопы дәруіш» (“The Last Sufi Dervish”) inscription opens the video essay under the same title (0:07).

Figure 30. A shot from Ermek Tursunov’s film Kelin (2009) recombined with the conversation about academic elitism associated with the Western-centric approaches to native Kazakh cultural and spiritual practices (4:25).

4. Public and amateur literary humanities?

Considering these examples of digital critical authorship, we may now ask: Why exactly should we as academics consider postscholarly video essays as public literary humanities work? In other words, while public humanities ideally revolve around the realm of genuinely public values and forums of expression, it remains unclear how today’s video essays speak to the contemporary literary discipline or even public humanities work conducted by academic professionals.Footnote 71 To address this question, I would like to draw the crucial distinction between the public (post-)professional and postscholarly explorations of humanities.

As I have suggested earlier, postscholarly criticism partially emerges due to the integration of the academy into the wider economic market. On the professional academic spectrum, the university’s loss of autonomy has been most visible in the humanities disciplines, which have long strived to adjust their offerings to the shifting demands of the academic labor market. As such, “a growing emphasis on profit and utility at the expense of humanistic inquiry, declining state support for the liberal arts, the adjunctification of the professorate, and the quantification of scholarly thought and research” have gravely affected the discipline.Footnote 72 In a partial response to these challenges, prominent literary humanities scholars have chosen to significantly diversify their intellectual labor by entering alternative, more promising entrepreneurial markets offered in the social platform environment. Thus, today’s humanities experts are often caught in a situation where they cannot but pursue general public-oriented careers, extending their academic labor through alternative forums. As Jonathan Kramnick puts it, “[m]uch of the recent [professional] interest in public criticism…has emerged as a response to the sharply felt labor crisis and the sense that graduate education as currently structured cannot be sustained.”Footnote 73

In contrast with the public humanities professionals, however, today’s author-critics practicing video essay work appear to be differently motivated. Put simply, the latter are hardly preoccupied with the matter of (post-)professionalism and instead invest in digital entrepreneurial authorship, which, beyond fulfilling the goal of public self-expression, is meant to entertain relevant audiences and seek their support through likes, comments, and sponsored subscriptions. In short, these digital creators often aim for public recognition and visibility as self-appointed auteurs rather than as aspiring professionals. Symptomatically, this new public incentive perfectly fits into the history of the literary discipline itself aptly observed by Christopher Hilliard: “[t]he professionalization of criticism” paradoxically “meant more amateurs doing it,” and since “literary criticism became institutionalized in universities and schools, critical procedures were taught to thousands of people for whom criticism would never become a profession.”Footnote 74

Slightly modifying Hilliard’s point, I would suggest that today’s individual digital authors do not, as a rule, wish to partake in (post-)academic intellectual labor and instead strive to perpetually conquer their own cultural autonomy from the dominant institutional producers of intellectual goods. Their conquest of the institutionalized academic culture is happening alongside their competition within the creative vlogging industry: if the latter promises prosperity through achieved recognition or even online celebrity status, the former offers slow intellectual labor without visible public exposure. As a result, many video essayists capitalize on the symbolic intellectual dividends of the humanities scholarship to ultimately promote their own individual views, creativity, and public image online. Functioning as a mode of cultural conquest, postscholarly criticism thus resonates more with Bourdieu’s idea of “heretical autodidactism” than with the (post-)professional public humanities practices.Footnote 75 Crucially, the video essayists’ counterdiscursive (i.e., counterinstitutional) attitudes expressed on the global digital scale present a significant challenge to the current humanities disciplines, putting the idea of professional expertise in these fields generally into question.

There may exist a disciplinary explanation for why many young students and aspiring scholars of the literary humanities prefer not to pursue academic careers. As I have already argued, the postscholarly video essay channels a popular sentiment often expressed online: that the work done in the academic humanities and digital content production is effectively indistinguishable. Deeming this significant, I would like to suggest that it is highly plausible that the scholarly logic of “amateurism,” promoted within the literary humanities, may have affected the young generation of student-critics.

Since modern humanities disciplines have historically formulated their epistemological and professional functioning against the more objective and unified methods of the natural sciences, they have, in principle, also resisted the coherent formulation of tasks and methods.Footnote 76 On the narrow disciplinary level, however, “the role of a critic” has become the defining professional category for Anglophone literary studies. Thus, as the literary scholar Bruce Robbins has recently put it, while “most of what literary critics do from day to day is still, as it has been in the past, appreciative,” the Anglo-American scholarship from I. A. Richards to Stanley Fish focused on articulating the professional role and function of a literary critic, ranging from cognitive psychological interpretive approaches to more “affective” reader-response theories.Footnote 77 When the poststructuralist and cultural studies’ moment later took hold in the academy, the progressive dispositional move toward “deprofessionalizing” the critic became the central episteme in English literary studies. In other words, the progressive call against the critically “detached” scholarly disposition in favor of a more “attached” academic mode has endowed the discipline with a more personally and politically involved attitude toward objects of study.Footnote 78

Retrospectively, such a genuinely progressive call was at least partially symptomatic of the excluded publics conquering the formerly gatekept domain of “humane,” Western-centric, and cultivated higher learning. However, nearly forty years after the progressive dispositional moment occurred within the discipline, the trend still continues, albeit in a significantly modified way. To illustrate one recent example of academic dispositional approaches to literary criticism, the editors of the volume titled The Critic as Amateur (2020) suggest that “humanities professionals” “might be doing [their] best work when [they] feel at [their] most amateur,” describing the essays from the volume as open to instilling “vulnerability, passion, and even ignorance into expertise.”Footnote 79 In a characteristic contrast with the earlier, cultural studies-infused progressive articulations of distance and attachment, this new disciplinary “amateurism” is chiefly derived from Felski’s work, whose insistence on dispositional optimism and positive affect launched the “postcritical” moment in English studies in the 2010s. In response to such depoliticization, Anna Kornbluh has directly charged the recent “promotion of amateur knowing” and the “autotheory” episteme of eschewing “critical distance and symptomatic interpretation in favor of more phenomenological and “amateur” concerns.”Footnote 80 Broadly aligning with Kornbluh, I contend that the newer disciplinary tendency is clearly distinct from, for example, Said’s “intellectual’s spirit as an amateur,” which he envisioned as a politically resistant academic stance “mobilized into greater democratic participation in the society.”Footnote 81

While a comprehensive literary historical account of the ideas of literary attachment/distance is yet to be drawn, I would still urge against the broad “amateur” approach within the humanities disciplines.Footnote 82 Crucially, from the vantage point of public literary humanities, understanding professional criticism in “amateur” terms primarily instills a lack of distinction between scholarly and non-scholarly modes of expression. Thus, on the disciplinary level, such an understanding implies that, for instance, digital book review cultures may not be so different from academic critical practice (save for the latter’s professional concerns and jargon). On the level of the postscholarly public humanities practiced online today, prominent digital author-critics similarly do not differentiate their work from the academic modes of professional criticism. Arguably, one reason for this might be that humanities disciplines have long promoted personal attachment as a professional disposition. Ultimately, if people outside the university perceive the digital essay form as both a means to personal self-expression and critical conversation on larger social issues, it appears unclear why today’s author-critics should confine themselves to the discipline to invest themselves in similar “amateur” projects, but in a much more restrictive professional environment. With the waning popularity of humanities programs worldwide, acknowledging direct disciplinary influences on new popular forms of criticism thus seems essential.

5. Future directions

To propose a further trajectory to public humanities, some final points deserve stressing. On the one hand, today’s digital video essay offers a glimpse into truly public explorations of the humanities, unconstrained by institutional matters of professionalism. Indeed, many authors practicing the genre on YouTube express genuine intellectual, human, and lived concerns, which resonate with thousands of users across the globe without academic experience in the humanities. On the other hand, the infrastructural conditions of social platforms themselves automatically convert these public expressions into consumable and marketable content. While often indeed positioned as digital creative entrepreneurs or fashionable providers of public “edutainment,” the video essayists simultaneously advance culturally significant arguments on social, political, and artistic values, challenging the thoughtless consumption of online content and promoting authentic human expression. In such a way, their work tells a complicated and yet illuminating story of the functioning of public criticism in the social platform era, certainly one worthy of further professional examination.

In turn, whether expressed through the video essay genre, literary reviews, or public podcasts, it is fundamental that popular authors often speak on behalf of the disciplinary humanities, which is enough for their content to become acknowledged and authorized online as public academic work. In this sense, many academic scholars today seem to severely underestimate—rather than overestimate—the high public value of the disciplinary humanities for contemporary global digital society. Most crucially, if this is what the digital public perceives as genuinely public scholarship, I see no reason why professionally trained and established academic scholars should necessarily treat their own online public intellectual presence as most authoritative and, most of all, publicly representative. In the absence of traditional gatekeeper mechanisms on mainstream social platforms, this appears even less plausible. Therefore, if the emergent field of public literary humanities is to take diverse conceptual paths, I deem it necessary to properly account for the variety of public critical genres that indirectly position themselves as postscholarly. Especially given that much of today’s digital non-expert public humanities inquiry often verges on sensationalism and anti-expertise, it is imperative on part of public humanities scholars to properly study different forms of global public postscholarship, including those which position themselves on the side of anti-scholarly reaction.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Dr. Elizaveta Shatalova, a recent PhD graduate from the University of Waterloo, Canada, the Department of English Language and Literature. Her work examines the interrelationships between institutionalized humanities and their reception by non-expert digital authors, which relies on interdisciplinary frameworks from the fields of literary criticism, public humanities, global cultural studies, and digital media theory.

Conflicts of interests

The author declares no competing interests.