1. Introduction

Income inequality has been at the center of the macroeconomic platform over the past few decades. It has been extensively documented that since the 1980s the US residual wage inequality accounts for a major proportion of its overall wage inequality and tends to increase faster among individuals with higher education (having some college or above).Footnote 1 In this paper, we highlight two key stylized facts:

[Fact 1] Over

![]() $70\%$

of overall inequality among the highly educated has been due to the residual inequality and about four-fifths of the residual wage inequality driven by wage dispersion within jobs, defined by industry–occupation pairs.Footnote

2

$70\%$

of overall inequality among the highly educated has been due to the residual inequality and about four-fifths of the residual wage inequality driven by wage dispersion within jobs, defined by industry–occupation pairs.Footnote

2

[Fact 2] Over the period of 1990–2018, the rise in the residual wage inequality of the highly educated has been particularly prominent during the early phase of 1993–2001.Footnote 3

Despite its important roles played in rising income inequality, little is known toward understanding the underlying drivers of within-job residual wage inequality, particularly so among the highly educated since the mid-1990s. To address this issue, we construct a novel sorting equilibrium model to explore theoretically several potentially important channels, both the intensive and the extensive margins, and then to quantify their contributions over the decades of 1990 and 2000 with the sharpest rising inequality.

In the higher education group, even if we control for more job characteristics including industry and occupation, about

![]() $90\%$

of the residual wage inequality remains. By decomposing the residual wage inequality into the between-job and within-job components over all the industry—occupation pairs, we find that the within-job wage inequality accounts for about

$90\%$

of the residual wage inequality remains. By decomposing the residual wage inequality into the between-job and within-job components over all the industry—occupation pairs, we find that the within-job wage inequality accounts for about

![]() $80\%$

of the residual wage inequality between 1990 and 2000. This suggests that the wage inequality among individuals with higher education is primarily driven by the within-industry/occupation inequality. To explain the aforementioned facts, we construct a sorting equilibrium model where, in addition to different job productivity levels, we consider (i) two extensive margin channels—workers optimally self-select into different jobs and pay positions (performance-pay versus fixed-pay positions) and (ii) an intensive channel—the quality of skill match. The chief purpose of the model is to investigate whether these margins may be important to explain the two facts on within-job inequality we established.

$80\%$

of the residual wage inequality between 1990 and 2000. This suggests that the wage inequality among individuals with higher education is primarily driven by the within-industry/occupation inequality. To explain the aforementioned facts, we construct a sorting equilibrium model where, in addition to different job productivity levels, we consider (i) two extensive margin channels—workers optimally self-select into different jobs and pay positions (performance-pay versus fixed-pay positions) and (ii) an intensive channel—the quality of skill match. The chief purpose of the model is to investigate whether these margins may be important to explain the two facts on within-job inequality we established.

Notably, the performance-pay incidence and match quality margins have direct data measurements. Yet, the sorting margin needs to be backed out upon calibrating the model—because this margin is between jobs, the calibration in general equilibrium is nontrivial due to computation of all job sorting wage cutoffs with the range of wages of each job all endogenously determined.

Workers in the performance-pay position are paid according to how much they contribute, and such payments usually include bonuses, commission, piece rates, and tips. The counterpart to this is the payment of a fixed hourly wage. While the literature has identified a positive wage effect of performance-pay, for example, by Lemieux et al. (Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009), we further examine the relation between the within-job wage inequality and the performance-pay incidence and find a significant positive relationship: jobs with higher performance-pay incidence usually have higher wage inequality. This hints at the potential role of the rising performance-pay incidence for widening wage dispersion. We measure job match quality based on the inverse relationship with skill mismatch. We compute the skill mismatch index for each job using workers’ occupation-relevant skill and ability measures from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) and occupation skill requirements from O*NET. Previous work such as Guvenen et al. (Reference Guvenen, Kuruscu, Tanaka and Wiczer2020) identify a negative wage effect of skill mismatch whereby better job match quality is associated with higher compensation, we further show a negative relationship between the skill mismatch index and within-job wage inequality: jobs with lower match quality are paid more equally. Hence, improved match quality may also serve to explain the within-job wage inequality. By conducting regression analysis, we find that increases in performance-pay incidence or match quality raise wage inequality significantly. While the empirical analysis suggests a plausible relationship between the wage inequality of each job and the job characteristics of interests in partial equilibrium, the result might be different in general equilibrium and when interactions between different channels are allowed. In addition, the regression results are silent on the counterfactual scenario, thus limiting the ability to conduct rich policy analysis. This thereby requires a deep structure to discipline the interactions among them.

In our sorting equilibrium framework, workers are heterogeneous in their innate abilities. Each job is associated with different productivity and two payment schemes: performance pay and fixed pay. In a fixed-pay position, a worker earns a pooled wage independent of his/her ability, effort or match quality. In the performance-pay position, a worker’s pay positively depends on his/her contribution to production. A worker in a better-matched job is captured by drawing a higher productivity premium from matching, which leads to a higher wage payment. Higher expected match quality thus plays an important role in position selection and job sorting.

Job-specific disutility is incurred for workers in a performance-pay position to capture monitoring costs. Match quality and the resulting productivity-premium also vary by job. In the sorting equilibrium, workers optimally choose their jobs and positions. Under proper assumptions, we show that equilibrium sorting is positive assortative, with the less talented workers choosing the fixed-pay position and the more talented workers selecting the performance-pay position at different jobs based on job productivity and the expected returns dependent on matching premium.

The within-job wage inequality can then be decomposed into that within the performance-pay position and the differences in the average wage between the performance-pay and the fixed-pay positions. In general, performance-pay income is more dispersed than fixed-pay income. Analytically, in a one-job case, we can establish a positive relationship between the performance-pay incidence and within-job wage inequality when the share of the educated workers in the performance-pay position is not too large. This case is equivalent to a multi-job one under a given sorting outcome. A better technology or higher match quality is shown to amplify the effect of the performance-pay incidence on the within-job and the within-performance-pay inequality but dampens its effect on the within-job and between-position inequality, thereby leading to an ambiguous net impact overall. The relative magnitudes of these effects depend crucially on the degree of complementarity between workers in different positions and their relative employment size. With endogenous sorting across jobs, the resulting cutoff abilities further interact with performance pay and match quality in a complex manner. As a consequence, how various channels affect the within-job wage inequality becomes a quantitative question.

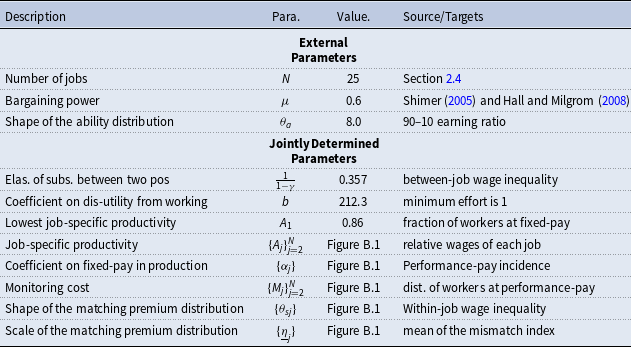

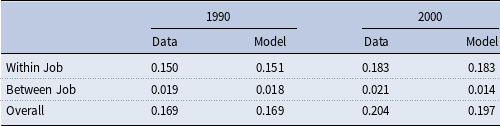

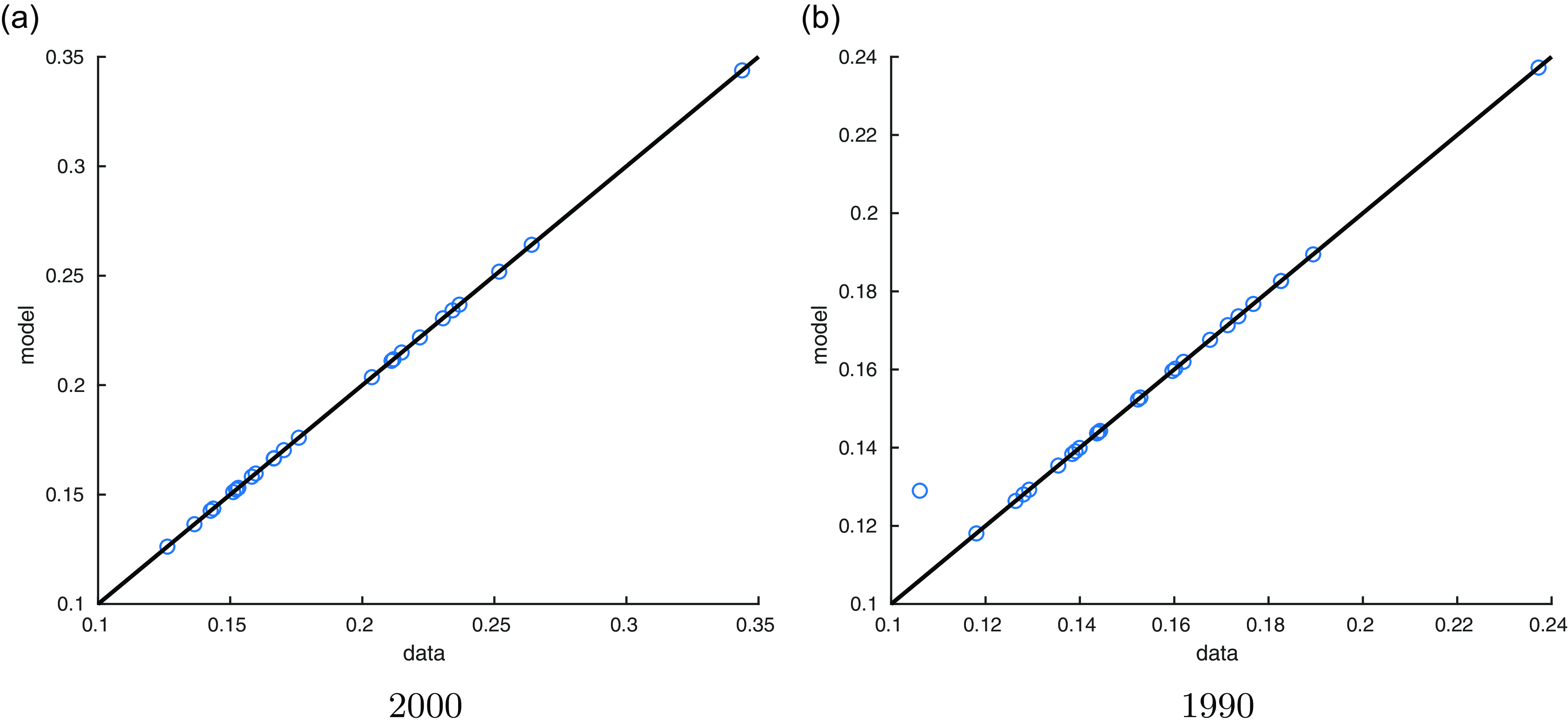

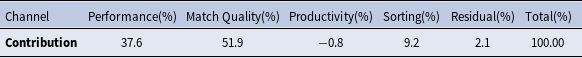

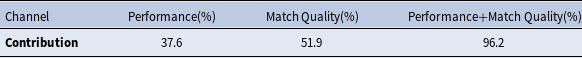

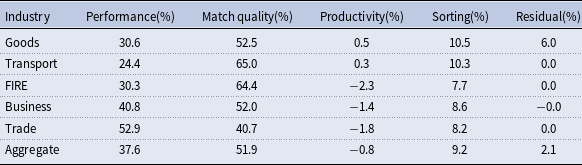

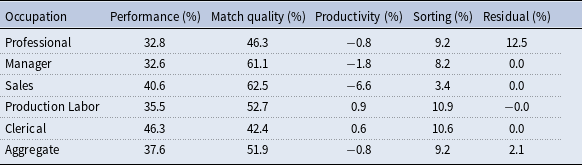

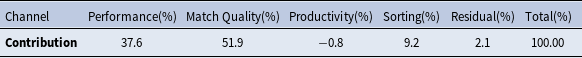

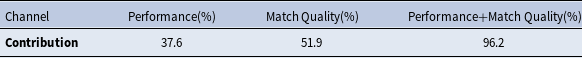

To quantify the roles of the performance-pay incidence, match quality, job productivity, and job sorting played in rising wage inequality, we calibrate the model by matching several of the key job-specific features of wage inequality and employment in the US economy in 2000. To conduct counterfactual–based decomposition exercises, we restore the value of each job-specific factor in 2000 to the corresponding value in 1990 by perturbing the distribution of each variation, while maintaining all the other parameters at their benchmark values. The results indicate that our model can capture most of the changes in within-job wage inequality from 1990 to 2000, with an essentially zero residual component. Our decomposition analysis suggests that changes in performance pay and match quality alone account for around

![]() $90\%$

of widening within-job wage inequality. Moreover, we find amplifying interactive effect compared with the situation if we either let the performance-pay incidence or match quality take their values in 1990. While sorting makes a modest contribution to the widening inequality, the role of residual job productivity is inconsequential. Since performance pay and match quality are the main drivers, pro-active policy intervention aiming to reduce inequality may be at the expense of less prevalence of performance pay or skill mismatch.

$90\%$

of widening within-job wage inequality. Moreover, we find amplifying interactive effect compared with the situation if we either let the performance-pay incidence or match quality take their values in 1990. While sorting makes a modest contribution to the widening inequality, the role of residual job productivity is inconsequential. Since performance pay and match quality are the main drivers, pro-active policy intervention aiming to reduce inequality may be at the expense of less prevalence of performance pay or skill mismatch.

Intuitively, once match quality is assured and workers are offered with correct incentives by performance pay with better ones selecting performance pay positions, the role played by positive assortative sorting across jobs must diminish as a consequence. Ex ante one cannot tell which type of sorting is strong and the existing literature is silent about this. In this paper, we provide a thorough quantitative contrast between them. Moreover, job-specific productivity alone does not convert to higher output—it must be combined with workers’ ability and the quality of match. Thus, to some degree, it resembles the Solow residual in neoclassical aggregate production—departing from the neoclassical canonical framework; however, within- and cross-job sorting is in play in our paper. The results indicate that upon incorporating performance pay and match quality, residual productivity adds little explanatory power to underlying drivers in the model—a finding granting the paper as an endogenous TFP story.

We also perform similar decomposition exercises based upon, respectively, changes in the rankings of average wages and employment shares from 1990 to 2000. The lion’s share of the contribution (more than

![]() $85\%$

) to widening within-job inequality comes from jobs whose average earnings rankings change moderately (by 1 or 2) or remain unchanged, where both performance pay and match quality play comparably important roles. For jobs whose employment share rankings remain unchanged, which make up more than half of the changes in the overall within-job inequality, match quality is found to play a greater role than the performance-pay incidence.

$85\%$

) to widening within-job inequality comes from jobs whose average earnings rankings change moderately (by 1 or 2) or remain unchanged, where both performance pay and match quality play comparably important roles. For jobs whose employment share rankings remain unchanged, which make up more than half of the changes in the overall within-job inequality, match quality is found to play a greater role than the performance-pay incidence.

The main takeaway of our paper is that while the within-job wage inequality accounts for about

![]() $80\%$

of the residual wage inequality between 1990 and 2000, approximately

$80\%$

of the residual wage inequality between 1990 and 2000, approximately

![]() $90\%$

of such rising dispersion is a consequence of higher performance-pay incidence and improved match quality. Once the extensive margin via performance pay and the intensive margin via match quality are incorporated, job sorting becomes much less important, while residual job productivity is inconsequential throughout for the within-job wage inequality. Policymakers concerning earned income inequality should thus be careful to account for the equity-efficiency tradeoff because the two primary sources of wage dispersions within jobs—performance pay and match quality—are natural in the eyes of production efficiency.

$90\%$

of such rising dispersion is a consequence of higher performance-pay incidence and improved match quality. Once the extensive margin via performance pay and the intensive margin via match quality are incorporated, job sorting becomes much less important, while residual job productivity is inconsequential throughout for the within-job wage inequality. Policymakers concerning earned income inequality should thus be careful to account for the equity-efficiency tradeoff because the two primary sources of wage dispersions within jobs—performance pay and match quality—are natural in the eyes of production efficiency.

1.1 Related literature

Several studies have documented the trend of rising wage inequality since the 1970s (e.g., Piketty and Saez, Reference Piketty and Saez2003; Acemoglu and Autor, Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011). Although one convincing theory claims that skill–biased technology change can account for the rising skill premium (e.g., Juhn et al., Reference Juhn, Murphy and Pierce1993; Krusell et al., Reference Krusell, Ohanian, Ríos-Rull and Violante2000; Acemoglu, Reference Acemoglu2003), Altonji et al. (Reference Altonji, Kahn and Speer2016) argue that earnings differences among college students across majors can be larger than the skill premium between college and high school. In general, the residual wage inequality accounts for most of the overall increased wage inequality (e.g., Katz and Autor, Reference Katz and Autor1999; Lemieux, Reference Lemieux2006).

Recent studies focus on within-industry or within-firm wage inequality. For example, Barth et al. (Reference Barth, Bryson, Davis and Freeman2011) emphasize the role of plant differences within industries and argue that this could explain two-thirds of wage inequality in the United States, whereas Card et al. (Reference Card, Heining and Kline2013) find that plant heterogeneity and assortativeness between plants and workers explain a large part of the increase in wage inequality in West Germany. Additionally, Mueller et al. (Reference Mueller, Ouimet and Simintzi2017) study the skill premium within firms and find that firm growth has increased wage inequality. While Papageorgiou (Reference Papageorgiou2011) highlights the labor markets within firms and concludes that the within-firm part might explain one-eighth to one-third of the increase in wage inequality, Song et al. (Reference Song, Price, Guvenen, Bloom and Von Wachter2019) argue that the between-firm component can explain two-third of the rise in wage inequality. To compare our results with theirs, we note that “within industry” includes both within-firm and between-firm, while “within firm” includes both within-occupation and between-occupation. Thus, there are intersections between within-firm and within industry-occupation, and the between-firm part appears to be the main reason for rising within industry-occupation inequality in our exercise.

There are also a growing number of studies that examine wage inequality between and within occupation (see, e.g., Erosa et al. Reference Erosa, Fuster, Kambourov and Rogerson2024). While Kambourov and Manovskii (Reference Kambourov and Manovskii2009) argue that the variability of productivity shocks in occupations coupled with endogenous occupational mobility could account for most of the increase in within-group wage inequality between the 1970s and mid-1990s, Scotese (Reference Scotese2012) shows that changes in wage dispersion within occupations are quantitatively as important as wage changes between occupations for explaining wage inequality between 1980 and 2000. In a more related study, Akerman et al. (Reference Akerman, Helpman, Itskhoki, Muendler and Redding2013) use Sweden employee–employer data to decompose the residual wage inequality and find that within the sector-occupation component (which we call within jobs) it accounts for a large proportion for both the level and change from 2001 to 2007. We confirm that a similar trend is found using the US data.

Performance pay The literature on performance pay either studies incentives and productivity (e.g., Jensen and Murphy, Reference Jensen and Murphy1990; Lazear, Reference Lazear2000) or explains the racial or gender wage gap through the different performance-pay rates by race or gender (e.g., Heywood and Parent, Reference Heywood and Parent2012; Heywood and Parent, Reference Heywood and Parent2017). Makridis (Reference Makridis2018) finds a positive relationship between the performance-pay incidence and wage premium and shows that longer working hours lead to more on-the-job human capital investment. While his study focuses on the dynamic effects of performance pay on human capital accumulation, our study emphasizes the interactions among performance pay, match quality and sorting within and between jobs. In addition, Makridis and Gittleman (Reference Makridis and Gittleman2022) find that performance-pay jobs adjust compensation more on the intensive margin, for which we concur but our incorporation of the aforementioned interactions produces richer results. Another relevant study is Lemieux et al. (Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009), who suggest performance pay as a channel through which the underlying changes in returns to skills are translated into higher wage inequality. They conclude that wages in performance-pay jobs are more sensitive to abilities and that inequality is much higher. While the within-job selection in their work is a partial equilibrium outcome, our general equilibrium framework adds two important features: (i) the wages in the non-performance-pay position affect selections in all the jobs. (ii) sorting across jobs affects within-job sorting. In addition, while they emphasize the monitoring cost on selection, we highlight match quality as another driver affecting sorting both within and between jobs. Furthermore, Wallskog et al. (Reference Wallskog, Bloom, Ohlmacher and Tello-Trillo2024) identifies empirically that the increase of within-firm inequality is mainly driven by adoption of aggressive performance-pay bonus and management schemes, thereby lending support to the channels proposed in our theory.

Quality of skill match The general idea of skill mismatch is that workers that share the same characteristics might have different productivity from the job or machine in or on which they are working. Violante (Reference Violante2002) provides a channel through vintage capital to decompose the residual wage inequality into a worker’s ability dispersion, a machine’s productivity dispersion, and the correlation between them. He argues that this channel could explain most transitory wage inequality and 30% of residual wage inequality. Jovanovic (Reference Jovanovic2014) builds a learning–by–doing model to emphasize the role of matching between employees and employers. Under such a framework, he discusses the roles of improving signal quality and assignment efficiency. Both studies are remotely related due to very different model settings and underlying issues of investigation. Concerning the measurement of match quality, there are two general two approaches: (i) the first is to measure the distance between skill requirement and acquirement based on the scores of skills from NLSY79 and O*NET (e.g., Sanders, Reference Sanders2014; Guvenen et al., Reference Guvenen, Kuruscu, Tanaka and Wiczer2020; Lise and Postel-Vinay, Reference Lise and Postel-Vinay2020); (ii) the second is to measure job relatedness between the field of study in the highest degree and current occupation (e.g., Robst, Reference Robst2007; Arcidiacono, Reference Arcidiacono2004; Ritter and West, Reference Ritter and West2014; Kirkeboen et al., Reference Kirkeboen, Leuven and Mogstad2016). Since the second measurement relies on subjective responses that might be biased depending on unobservable individual characteristics, we elect to use the first approach to construct a skill mismatch index following Guvenen et al. (Reference Guvenen, Kuruscu, Tanaka and Wiczer2020).Footnote 4 Finally, Bandiera et al. (Reference Bandiera, Kotia, Lindenlaub, Moser and Prat2024) study mismatch using internationally comparable microdata. Although the main focus is on meritocracy and income difference across countries, one result in this paper that increase technology, which increases the match return, will increase the wage inequality is consistent with our results that high match probability or quality will increase inequality.

2. Stylized facts

Here, we document several stylized facts on performance-pay incidence, skill mismatch, and wage inequality. First, we show how the performance-pay incidence and skill mismatch index are estimated. Second, we compute wage inequality using different measurements, and decompose it into the between- and within-job components. Third, we examine the relationships between the performance-pay incidence, skill mismatch, and wage inequality across jobs.

Our data are collected from several sources, including the March Current Population Survey (March CPS), Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), 1979 National Longitudinal Survey NLSY79, and O*NET. The March CPS includes the most extended high-frequency data series enumerating labor force participation and earnings in the US economy. The PSID contains detailed information on earnings, including commission, bonuses, piece rates, and tips. In NLSY79, respondents were given an occupational placement test—the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB)—that provides detailed measures of occupation-relevant skills and abilities. In addition, respondents reported various measures of non-cognitive skills, which can reflect a worker’s ability for socially interactive work. Finally, O*NET provides the skill requirements for each occupation.

2.1 Estimation of the performance-pay incidence and skill mismatch index

Industry/occupation classification The Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) provides two- and three-digit occupation and industry codes. However, the classification is inconsistent from 1983 to 2018. To address this, we build consistent one-digit industry and occupation codes as in Lemieux et al. (Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009). Meanwhile, we build a consistent three-digit code following Dorn (Reference Dorn2009). Finally, the same method is used to group a consistent two-digit code.Footnote 5 To circumvent the mis-classification problem over different years due to changes in the content of either occupation or industry, and the problem of empty cells, we use the one-digit industry and occupation codes and check the inclusion of the two-digit occupation code when there is a potential concern.

Performance-pay incidence Performance pay includes bonuses, commission, and piece-rate payment. A significant challenge is to identify workers in a performance-pay position. The PSID, which has been extensively discussed in the literature, reports the format of the payment that a worker has received in a given year among the three performance pay components. However, for workers without those payments, we cannot distinguish whether they work in fixed-pay positions or do not merit, say, bonuses in that given period. Fortunately, the longitudinal nature of PSID data allows us to track the payment history to examine whether a worker has received any form of performance pay in their current job, providing a much more accurate measure (see Lemieux et al., Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009).Footnote 6

Following Lemieux et al. (Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009), we estimate performance-pay incidence over time using a linear probability model where we regress the dummy of the performance pay on job (industry by occupation) dummy. Specifically, we construct a performance-pay indicator variable looking at whether a part of a worker’s total compensation includes a variable pay component (bonus, commission, or piece-rate) during the sample period. Naturally, conditional on the job duration, we tend to observe a given job match fewer times at the two ends of the sample period than in the middle of the sample. To solve this end-point problem, we follow their solution involving re-balancing the sample using regression or other methods. In practice, we adjust the measures of the performance-pay incidence over time by estimating a linear probability model in which dummies for calendar years and the number of times the job match is observed are included as regressor. We then compute an adjusted measure of the performance pay incidence by using the distribution of the number of times the job match is observed to its average value for the years 1982 to 2000, which are relatively unaffected by the end-point problem. Finally, we keep both less and highly educated workers in PSID for two reasons. First, the sample size would become too small to run the regression if we only retain highly educated workers. Second, we treat the performance-pay incidence as one of the job characteristics so that it would be better to retain the full sample.Footnote 7

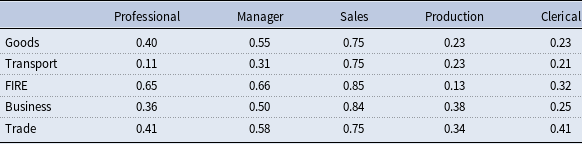

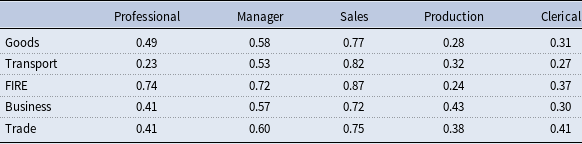

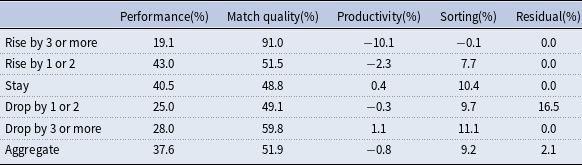

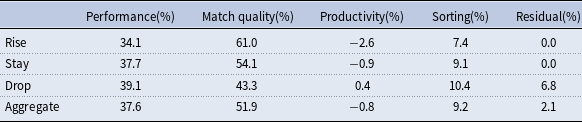

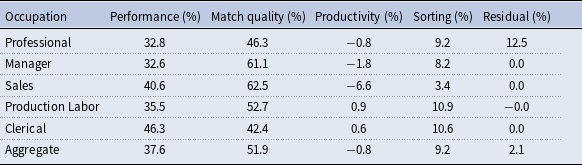

We estimate the performance-pay incidence for 80 jobs separately for the years up to 1990 and 2000. To have a consistent code with skill mismatch, we also group them into 25 jobs. Tables 1 and 2 present the results for 25 jobs and show that performance-pay incidence has increased from 1990 to 2000 in general. The results are similar for 80 jobs, as shown in Tables A.9 and A.10.

Table 1. Incidence of performance-pay for 25 jobs: 1990

Notes: This table presents the estimated performance-pay incidence for the highly educated for 25 jobs for the year 1990, following the approach in Lemieux et al. (Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009). Data source: PSID.

Table 2. Incidence of performance-pay for 25 jobs: 2000

Notes: This table presents the estimated performance pay incidence for the highly educated for 25 jobs for the year 2000, following the way in Lemieux et al. (Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009). Data source: PSID.

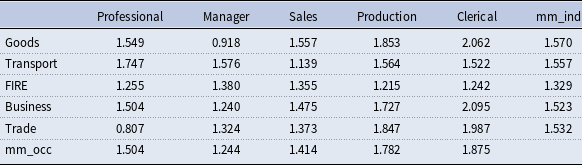

Skill mismatch index We approximate the quality of skill match by the inverse of the skill mismatch index. We compute the skill mismatch index using NLSY79 and O*NET following Guvenen et al. (Reference Guvenen, Kuruscu, Tanaka and Wiczer2020). NLSY79 tracks a nationally representative sample of individuals aged between 14 and 22 years on January 1, 1979. It contains detailed information on the industry and occupation in which each individual worked. All respondents took the ASVAB test at the beginning of the survey. The respondents were also given a behavioral test to elicit their social attitudes (e.g., self-esteem and willingness to engage with others). The ASVAB version taken by NLSY79 respondents had 10 component tests. We focus on the following 4 components of verbal and math abilities, which can be linked to skill counterparts: Word Knowledge, Paragraph Comprehension, Arithmetic Reasoning, and Mathematics Knowledge. The NLSY79 included three attitudinal scales that measure a respondent’s non-cognitive abilities. We use two of these measures as social abilities: the Rotter locus of control and Rosenberg self-esteem scales. Because age differences can affect scores, we equalized the mean and variance of each test score across ages. Similar to PSID, we retain the full sample to ensure that we have a sufficient sample size and capture the job’s characteristics.

O*NET includes information on 974 occupations, which can be mapped to the 292 occupation categories included in NLSY79. For each occupation, O*NET analysts score the importance of the 277 descriptors. We use the 26 descriptors most related to the ASVAB component tests and another 6 descriptors related to social skills.

We aggregate information about workers’ abilities and occupational skill requirements into verbal, math, and social ability following Guvenen et al. (Reference Guvenen, Kuruscu, Tanaka and Wiczer2020). We restate them as follows. First, we convert the O*NET skills into four ASVAB test categories using the relatedness score created by the Defense Manpower Data Center. For each ASVAB category test, we create an O*NET analog by summing the 26 descriptors and weighting them by this relatedness score. Therefore, each occupation yields a set of scores comparable to the ASVAB categories, each a weighted average of the 26 original O*NET descriptors.

Second, we normalize each dimension’s standard deviation to be 1 and reduce these 4 ASVAB categories into 2 composite dimensions—verbal and math—by applying principal component analysis. Similarly, we normalize each dimension of the 6 O*NET descriptors related to social skills standard deviation to be 1 and reduce them to a single dimension.Footnote 8 We convert all six scores (verbal, math, and social worker abilities, and verbal, math, and social occupation requirements) into percentile ranks among individuals or occupations.

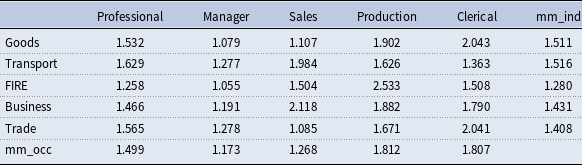

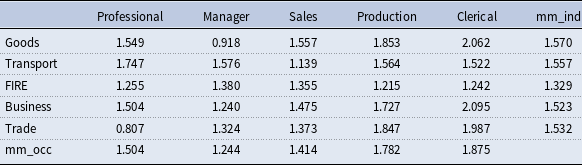

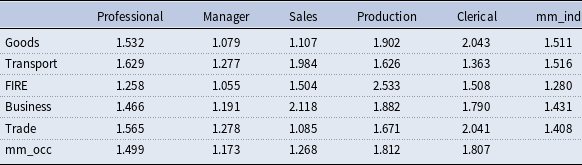

Third, we compute the individual-level mismatch index and then aggregate them into 25 jobs in 1990 and 2000. Tables 3 and 4 show that skill mismatch has decreased in general from 1990 to 2000, that is, the match quality has increased.

Table 3. Skill mismatch index in 1990

Notes: This table presents the average skill mismatch for 25 jobs for the year 1990. “mm_occ” and “mm_ind” represent the average skill mismatch within occupation and industry, respectively. Data source: NLSY79 and ONET, and authors’ calculation.

Table 4. Skill mismat3h index in 2000

Notes: This table presents the average skill mismatch for 25 jobs for the year 1990. “mm_occ” and “mm_ind” represent the average skill mismatch within occupation and industry, respectively. Data source: NLSY79 and ONET, and authors’ calculation.

For robustness check, we also measure the skill mismatch in two alternative ways. First, the current method using total 26 skills in cognitive skills, while as an alternative, one use 6 skills as cognitive skills, representing the minimal level in this category. Figure A.1 presents the comparison in 1990 (left) and 2000 (right) for 2-digit code occupation. It shows that these two measurements are closely related, despite that the values in alternative are slightly higher than the benchmark ones. Second, we measure mismatch by a subjective response on the relatedness between college major and occupation using data from National Survey of College Graduate, then a high relatedness should reflect low skill mismatch.Footnote 9 Figure A.2 compares skill mismatch with the job relatedness and shows a clear-cut negative correlation as expected.

2.2 Measuring wage inequality

We compute the wage inequality using the March CPS where only full-time and full-year workers, defined as those working for at least 40 weeks in a year and 35 hours in a week, and aged between 16 and 65 years. Wages are defined as real hourly earnings. We drop hourly earnings below half the minimum wage in 1982 dollars or higher than USD 1000. The top-coding wage is low in some studies; for example, it is 100 (in 1979 dollars) in Lemieux et al. (Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009) and around 180 in Acemoglu and Autor (Reference Acemoglu and Autor2011). Because we focus on highly educated individuals, we do not trim the top incomes by as much.

In the March CPS, the education level is grouped into six categories: primary, high school dropout, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, and post-college. The implied years of schooling are 6, 9, 12, 14, 16, and 18, respectively. Potential experience is then computed as the difference between the year after graduation and age.Footnote

10

The highly educated group includes workers who have some college education and above; the proportion of this group increased from

![]() $45\%$

in 1983 to

$45\%$

in 1983 to

![]() $66\%$

in 2018.

$66\%$

in 2018.

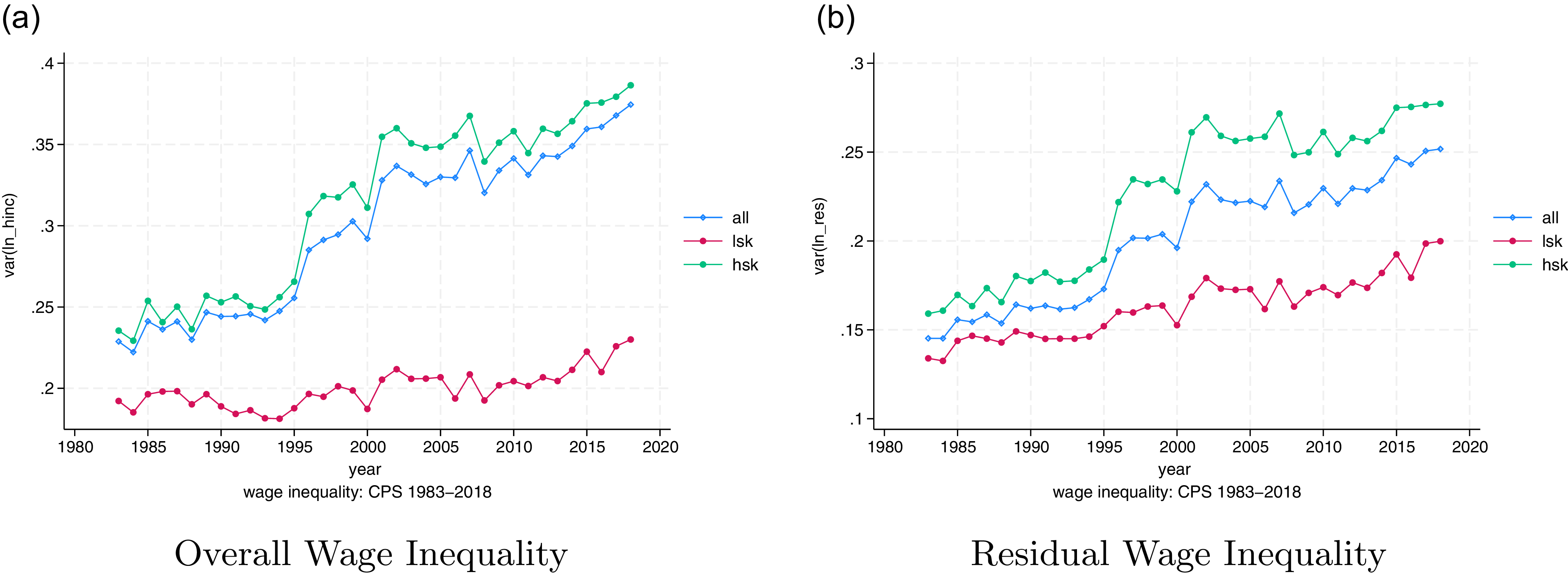

We measure wage inequality as the variance in the logarithm of wage. The left panel of Figure 1 presents the pattern of wage inequality by education group from 1983 to 2018. In general, wage inequality has been increasing since the 1980s among all groups. However, patterns also vary between education groups. Compared with the less educated group, the highly educated group has higher wage inequality and increases faster, especially since the late 1990s.

Following the convention in the literature (e.g., Kambourov and Manovskii, Reference Kambourov and Manovskii2009), we obtain residual wages after controlling for sex, race, experience, and education. The residual wage inequality is then measured as the variance in the residual wages. As shown in the right panel of Figure 1, the highly educated group has higher residual wage inequality which increases faster, especially during 1993–2001. As a robustness check, we calculate the Gini coefficient and 90–10 ratio as well. Figure A.3 shows that both the Gini coefficient and 90–10 ratio exhibit a similar pattern in the highly educated group. In summary, both facts confirm the substantial level of within-group inequality. In addition, the residual wage inequality within the highly educated group exceeds the overall average and increases faster, especially between 1990 and 2000.

Figure 1. Wage inequality by education group.

Notes: In the left (right) panel, the inequality is measured as the variance in the log value of hourly wages (residual wages). In both panels, the blue line represents the inequality for the whole sample (all) and the green line only includes those highly educated or high skilled (hsk). The red line is for the low education group or low skilled (lsk). Data source: March CPS from the CEPR.

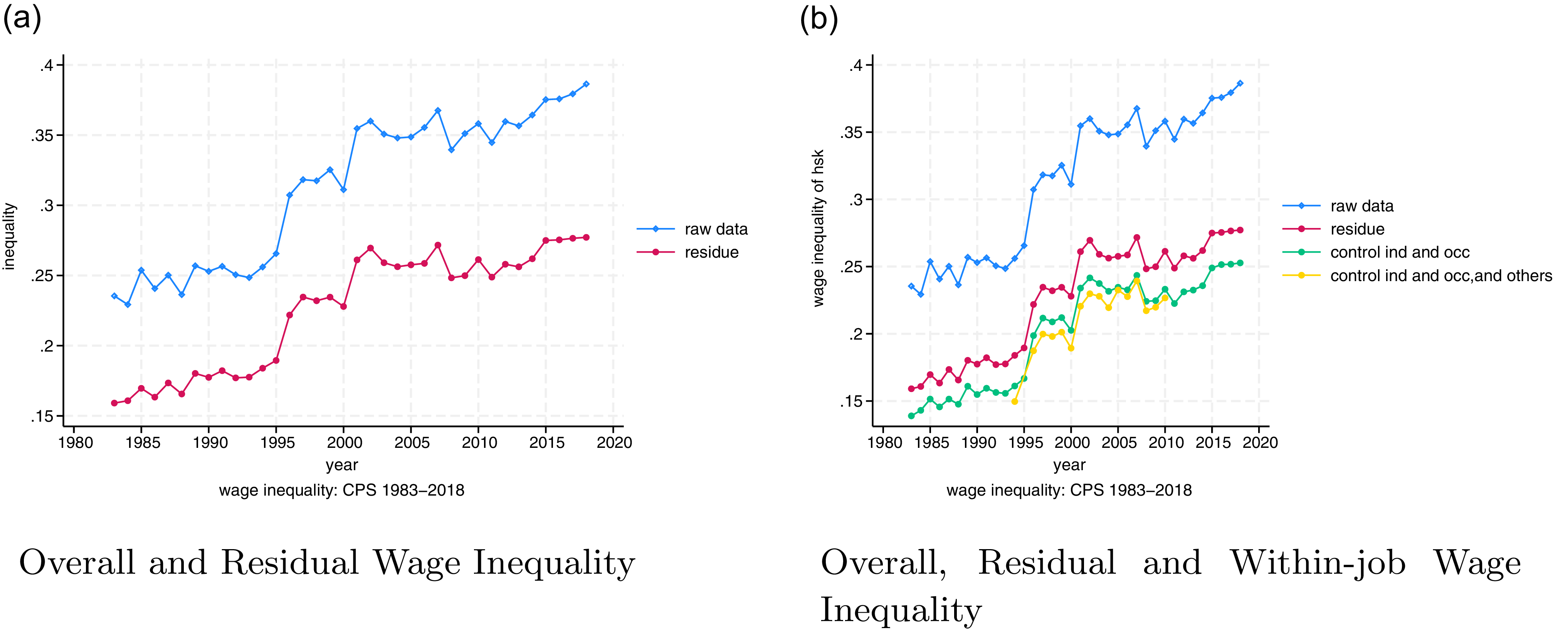

Figure 2. Residual wage inequality of the highly educated.

Notes: In both panels, the inequality is measured among the highly educated. The blue line represents the overall wage inequality. The red line is the residual wage inequality after controlling for only demographic characteristics. The green line is the residual wage inequality after further controlling for occupation and industry. The yellow line is the residual wage inequality after further controlling for location, firm size, and citizenship. Data source: March CPS from the CEPR.

We now examine the inequality within the highly educated group. The left panel of Figure 2 presents the evolution of both the overall and residual wage inequalities. The residual wage inequality accounts for around

![]() $70\%$

of the overall wage inequality among the highly educated. This proportion is higher than that commonly documented in the literature (e.g., Lemieux, Reference Lemieux2006) for the overall sample comprising individuals of different education levels. The right panel shows the trend of the residual wage inequality when controlling for additional job characteristics, including industry, occupation, location, firm size, and citizenship. Controlling for industry and occupation can only explain

$70\%$

of the overall wage inequality among the highly educated. This proportion is higher than that commonly documented in the literature (e.g., Lemieux, Reference Lemieux2006) for the overall sample comprising individuals of different education levels. The right panel shows the trend of the residual wage inequality when controlling for additional job characteristics, including industry, occupation, location, firm size, and citizenship. Controlling for industry and occupation can only explain

![]() $10\%$

more of inequality. The result changes little when additional variables, such as location and firm size, are controlled. Thus, the wage inequality within industry and occupation significantly contributes to the residual wage inequality. To consolidate this finding, we decompose the residual wage inequality.

$10\%$

more of inequality. The result changes little when additional variables, such as location and firm size, are controlled. Thus, the wage inequality within industry and occupation significantly contributes to the residual wage inequality. To consolidate this finding, we decompose the residual wage inequality.

2.3 Decomposition of the wage inequality

Here, we decompose both the level and change in residual wage inequality into within- and between-job wage inequalities. A job is defined as an industry-occupation pair. Examples of jobs include sales in the FIRE industry, managers in business, clerical workers in retail/wholesale trade, and production workers in durable/nondurable goods, among others.

Decomposition of the level Suppose there are

![]() $J$

jobs indexed as

$J$

jobs indexed as

![]() $j=1,\ldots J$

. In job

$j=1,\ldots J$

. In job

![]() $j$

, we denote

$j$

, we denote

![]() $P_{j}$

as the employment share,

$P_{j}$

as the employment share,

![]() $V_{j}$

as the within-job wage inequality, and

$V_{j}$

as the within-job wage inequality, and

![]() $E_{j}$

as the average earnings. Then,

$E_{j}$

as the average earnings. Then,

![]() $\sum _{j}P_{j}V_{j}$

is the average within-job wage inequality weighted by the employment share. Further,

$\sum _{j}P_{j}V_{j}$

is the average within-job wage inequality weighted by the employment share. Further,

![]() $\sum _{j}P_{j}(\! \ln E_{j}-\sum _{j^{^{\prime }}}P_{j^{^{\prime }}}\ln E_{j^{^{\prime }}})^{2}$

is the weighted average of between-job wage inequality, where

$\sum _{j}P_{j}(\! \ln E_{j}-\sum _{j^{^{\prime }}}P_{j^{^{\prime }}}\ln E_{j^{^{\prime }}})^{2}$

is the weighted average of between-job wage inequality, where

![]() $\sum _{j^{^{\prime }}}P_{j^{^{\prime }}}\ln E_{j^{^{\prime }}}$

is the weighted average of the logarithm of earnings in the economy. Finally, the overall wage inequality

$\sum _{j^{^{\prime }}}P_{j^{^{\prime }}}\ln E_{j^{^{\prime }}}$

is the weighted average of the logarithm of earnings in the economy. Finally, the overall wage inequality

![]() $var(\ln E)$

can be decomposed into the between- and within-job components as follows:

$var(\ln E)$

can be decomposed into the between- and within-job components as follows:

The contribution of the within-job wage inequality to the total wage inequality then becomes the ratio of

![]() $\sum _{j}P_{j}V_{j}$

to

$\sum _{j}P_{j}V_{j}$

to

![]() $var(\! \ln E)$

.

$var(\! \ln E)$

.

Decomposition of the change We also decompose the changes in the residual wage inequality over time into the various components of interest. In job

![]() $j$

in year

$j$

in year

![]() $t,$

let

$t,$

let

![]() $V_{j,t}$

be the wage inequality,

$V_{j,t}$

be the wage inequality,

![]() $\ln E_{j,t}$

be the average log earnings,

$\ln E_{j,t}$

be the average log earnings,

![]() $P_{j,t}$

be the employment share, and

$P_{j,t}$

be the employment share, and

![]() $\ln E_{t}$

be the average log earnings among all jobs. Then, the change in the within-job wage inequality from

$\ln E_{t}$

be the average log earnings among all jobs. Then, the change in the within-job wage inequality from

![]() $t$

to

$t$

to

![]() $t+1$

is

$t+1$

is

![]() $V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t}$

, change in the between-job wage inequality is

$V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t}$

, change in the between-job wage inequality is

![]() $(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}$

, and change in the employment share is

$(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}$

, and change in the employment share is

![]() $P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t}$

. Therefore, the change in the wage inequality between years

$P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t}$

. Therefore, the change in the wage inequality between years

![]() $t+1$

and

$t+1$

and

![]() $t$

,

$t$

,

![]() $V_{t+1}-V_{t}$

, can be decomposed into four components: the weighted average change in the within-job wage inequality

$V_{t+1}-V_{t}$

, can be decomposed into four components: the weighted average change in the within-job wage inequality

![]() $\sum _{j=1}^{J}P_{j,t}[V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t}]$

, the weighted average change in the between-job wage inequality

$\sum _{j=1}^{J}P_{j,t}[V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t}]$

, the weighted average change in the between-job wage inequality

![]() $\sum _{j=1}^{J}P_{j,t}[(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}],$

the weighted average change in the employment share

$\sum _{j=1}^{J}P_{j,t}[(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}],$

the weighted average change in the employment share

![]() $\sum _{j=1}^{J}(P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t})[V_{j,t}+(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}],$

and an interaction term which is the product of the changes in the employment share, and sum of within- and between-job wage inequalities (simply termed as the “interaction” in the decomposition exercise):

$\sum _{j=1}^{J}(P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t})[V_{j,t}+(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}],$

and an interaction term which is the product of the changes in the employment share, and sum of within- and between-job wage inequalities (simply termed as the “interaction” in the decomposition exercise):

\begin{equation*} \sum _{j=1}^{J}(P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t})\{(V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t})+[(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}]\}. \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \sum _{j=1}^{J}(P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t})\{(V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t})+[(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}]\}. \end{equation*}

Formally, we decompose the change in wage inequality as follows:

\begin{align} V_{t+1}-V_{t} & = \sum _{j=1}^{J}P_{j,t}[V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t}]\nonumber \\ & + \sum _{j=1}^{J}P_{j,t}[(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}]\\ & + \sum _{j=1}^{J}(P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t})[V_{j,t}+(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}]\nonumber \\ & + \sum _{j=1}^{J}(P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t})\{(V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t})+[(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}]\}.\nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} V_{t+1}-V_{t} & = \sum _{j=1}^{J}P_{j,t}[V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t}]\nonumber \\ & + \sum _{j=1}^{J}P_{j,t}[(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}]\\ & + \sum _{j=1}^{J}(P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t})[V_{j,t}+(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}]\nonumber \\ & + \sum _{j=1}^{J}(P_{j,t+1}-P_{j,t})\{(V_{j,t+1}-V_{j,t})+[(\! \ln E_{t+1}-\ln E_{j,t+1})^{2}-(\! \ln E_{t}-\ln E_{j,t})^{2}]\}.\nonumber \end{align}

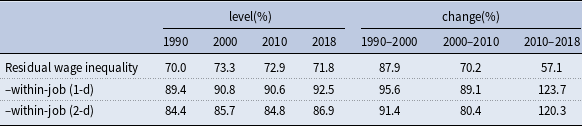

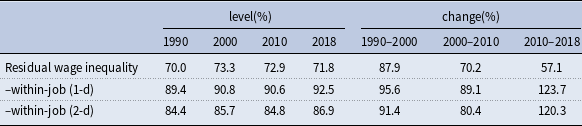

Similarly, each component’s contribution is defined as the ratio of its change to the total change in the residual wage inequality. Table 5 presents the composition of wage inequality from 1990 to 2018. Specifically, the first row shows that the residual wage inequality accounts for a large proportion of the overall wage inequality, which usually exceeds

![]() $70\%$

for the level and

$70\%$

for the level and

![]() $50\%$

for the change. More importantly, among the past four decades, the share of changes in residual wage inequality to changes in overall wage inequality is the highest from 1990 to 2000 (

$50\%$

for the change. More importantly, among the past four decades, the share of changes in residual wage inequality to changes in overall wage inequality is the highest from 1990 to 2000 (

![]() $87.9\%$

). Hence, we focus on 1990 and 2000 in the quantitative analysis. The second row shows that the contribution of the within-job wage inequality is around

$87.9\%$

). Hence, we focus on 1990 and 2000 in the quantitative analysis. The second row shows that the contribution of the within-job wage inequality is around

![]() $90\%$

for both the level and change under the 1-digit industry and occupation codes. There may be a concern that the significant contribution of the within-job wage inequality is a result of the broad occupation categorization. Hence, we perform a robustness check using the 1-digit (1-d) industry and 2-digit (2-d) occupation codes. As shown in the third row, the contribution of the within-job wage inequality remains sizable, at about

$90\%$

for both the level and change under the 1-digit industry and occupation codes. There may be a concern that the significant contribution of the within-job wage inequality is a result of the broad occupation categorization. Hence, we perform a robustness check using the 1-digit (1-d) industry and 2-digit (2-d) occupation codes. As shown in the third row, the contribution of the within-job wage inequality remains sizable, at about

![]() $85\%$

for level and above

$85\%$

for level and above

![]() $80\%$

for change.

$80\%$

for change.

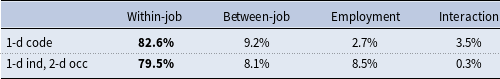

Table 5. How much residual wage inequality accounts for overall inequality

Notes: This table reports how much residual wage inequality accounts for overall inequality by levels or by changes over the previous decade. The first row reports the ratio of residual wage inequality to overall wage inequality. The second row reports the within-job component of residual wage inequality, where the jobs are classified by 1-digit occupations and industries. The third row reports within-job component of residual wage inequality, where the jobs are classified by 1-digit (1-d) industry and 2-digit (2-d) occupation codes. Data source: March CPS.

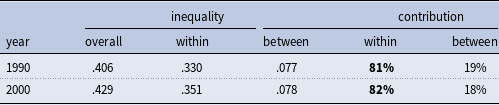

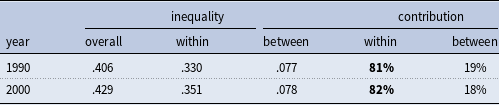

We also perform several other robustness checks. First, Table 6 presents the decomposition results using Census data under the 1-digit codes for the years of 1990 and 2000. The results indicate that the contribution of the within-job component is consistently above

![]() $80\%$

. In addition, Table A.11 presents the decomposition results using Census data under the 3-digit codes for the years of 1990 and 2000, showing that the contribution of the within-job component exceeds

$80\%$

. In addition, Table A.11 presents the decomposition results using Census data under the 3-digit codes for the years of 1990 and 2000, showing that the contribution of the within-job component exceeds

![]() $70\%$

. Moreover, Figure A.4 shows that the contribution of the within-job wage inequality is quite large throughout all years. Furthermore, the left panel of Figure A.5 decomposes the overall wage inequality, indicating that the contribution of the within-job wage inequality still exceeds

$70\%$

. Moreover, Figure A.4 shows that the contribution of the within-job wage inequality is quite large throughout all years. Furthermore, the left panel of Figure A.5 decomposes the overall wage inequality, indicating that the contribution of the within-job wage inequality still exceeds

![]() $75\%$

; and, the right panel that presents the decomposition result using the CPSORG dataset obtains similar findings as well.

$75\%$

; and, the right panel that presents the decomposition result using the CPSORG dataset obtains similar findings as well.

Table 6. Decomposition of residual wage inequality under 1-digit code

Notes: This table computes the contribution of the within-job and between-job inequality to the overall inequality in both 1990 and 2000 using 1-digit industry and occupation code. Data source: CENSUS from CEPR.

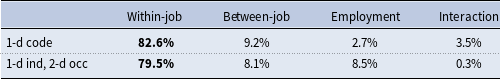

Second, Table 7 reports the contribution of all components between 1990 and 2000 using March CPS, which shows that the within-job significantly dominates other components. Table 8 presents the results using the CENSUS and CPSORG dataset, again showing that the within-job component accounts for the lion’s share. Additionally, Table A.12 summarizes the decomposition results using Census data under the 3-digit industry and occupation codes, where the contributions of the within-job component to the change in the residual wage inequality between 1990 and 2000 also exceed

![]() $80\%$

.

$80\%$

.

Table 7. Decomposition of the changes in residual wage inequality: March CPS

Notes: This table computes the contribution of within-job, between-job wage inequality, and the employment share interactions to the changes in the residual inequality from 1990 to 2000. The row “1-d code” indicates the one-digit industry and occupation code, “1-d ind, 2-d occ” indicates the one-digit industry and two-digit occupation codes. Data source: March CPS from the CEPR.

Table 8. Decomposition of the changes in residual wage inequality: CENSUS and CPSORG

Notes: This table computes the contribution of the within-job, between-job inequality, employment share and interactions to the changes in the residual wage inequality from 1990 to 2000 under 1-digit industry and occupation code. The row “CENSUS” indicates using data from CENSUS, “CPSORG” indicates using data from CPSORG. Data source: CENSUS and CPSORG from CEPR.

In summary, based on the results in Sections 2.2 and 2.3, we establish two robust stylized facts:

[Fact 1] Over

![]() $70\%$

of overall inequality among the highly educated has been due to the residual inequality, and about four-fifths of the residual wage inequality is driven by wage dispersion within jobs, defined by industry–occupation pairs.

$70\%$

of overall inequality among the highly educated has been due to the residual inequality, and about four-fifths of the residual wage inequality is driven by wage dispersion within jobs, defined by industry–occupation pairs.

[Fact 2] Over the 1990–2018 period, the rise in the residual wage inequality of the highly educated has been particularly prominent during the early phase of 1993–2001.

2.4 Performance-pay incidence, skill mismatch, and wage inequality

Next, we first explore the correlations between performance-pay incidence, skill mismatch, and within-job wage inequality. Then, we empirically examine how changes in the performance-pay incidence and skill mismatch over time may contribute to the increasing wage inequality. As the datasets are from various sources, throughout the remainder of the study, we classify industries and occupations each into five categories, consistent with the classification in the PSID and NLSY79.Footnote 11

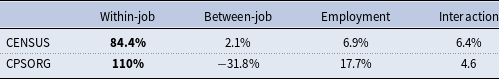

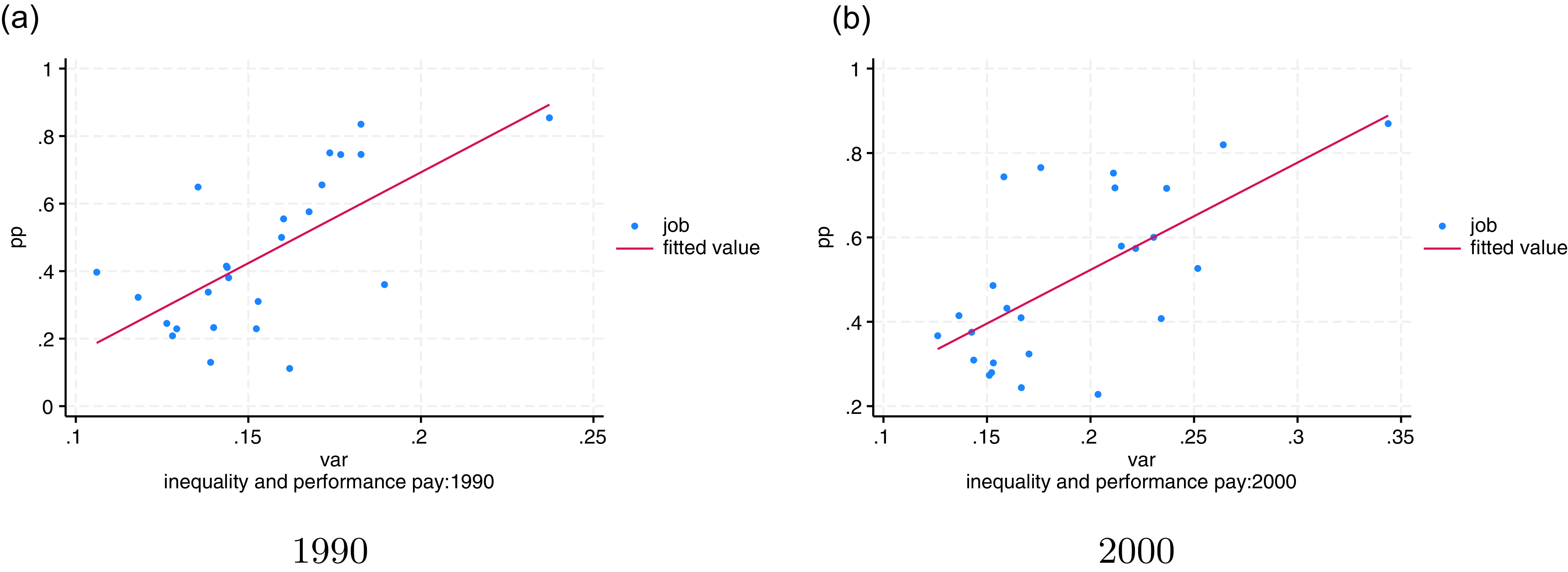

Figure 3 plots the performance-pay incidence against the within-job wage inequality for each of the 25 jobs in 1990 and 2000.Footnote 12 We find a significant positive relationship; that is, jobs with a higher performance-pay incidence usually have higher within-job wage inequality. In Appendix A.2, we also show that the relation is robust to using the same job classification as in Lemieux et al. (Reference Lemieux, MacLeod and Parent2009), containing 52 jobs (Figure A.6). In another robustness check, we plot the performance-pay incidence using the PSID data against wage inequality from the CPSORG dataset in Figure A.7. Furthermore, we try an alternative measurement of performance-pay ratio, defined as the ratio of earnings from performance-pay position to total earnings. Figure A.8 reveals a positive correlation between performance pay and wage inequality under this alternative measurement.

Figure 3. Performance-pay incidence and wage inequality.

Notes: In both panels, each dot represents a job(25 jobs in total). The x-axis is the performance-pay incidence. The y-axis is the within-job wage inequality. The left panel is based on 1990 data and right panel is based on 2000 data. The coefficients in two panels are 5.38 and 2.54, respectively. Data source: PSID and March CPS.

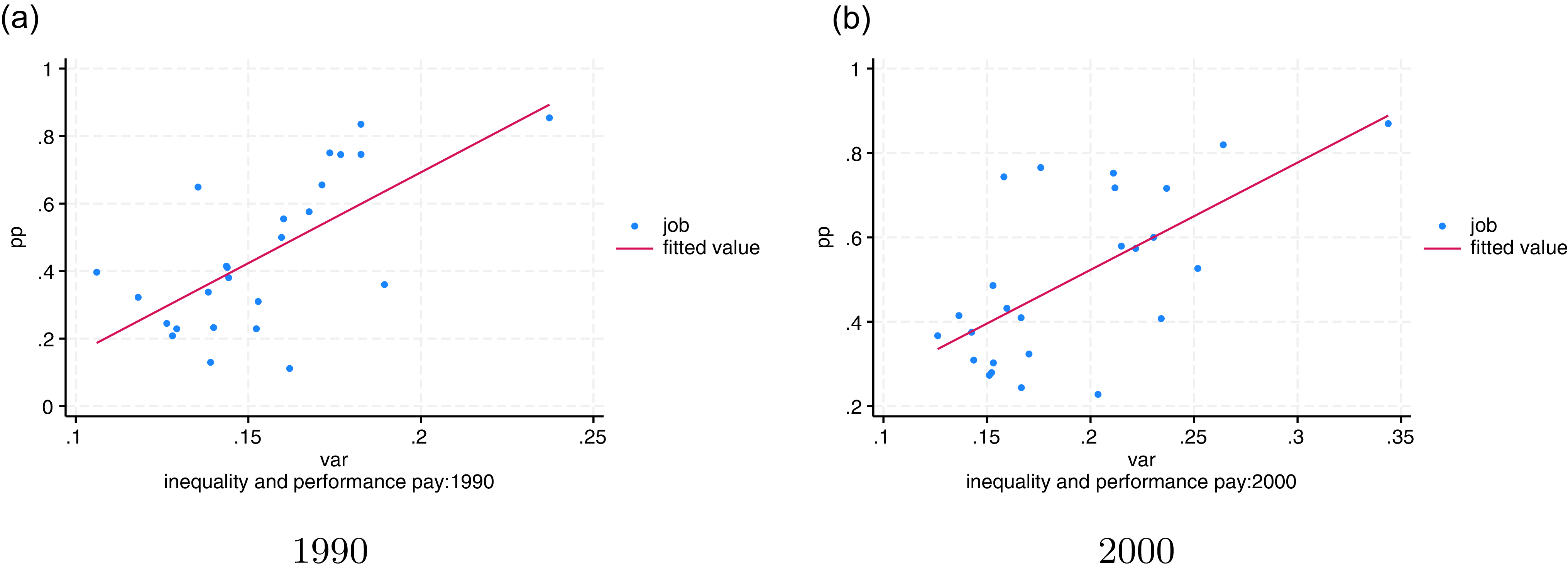

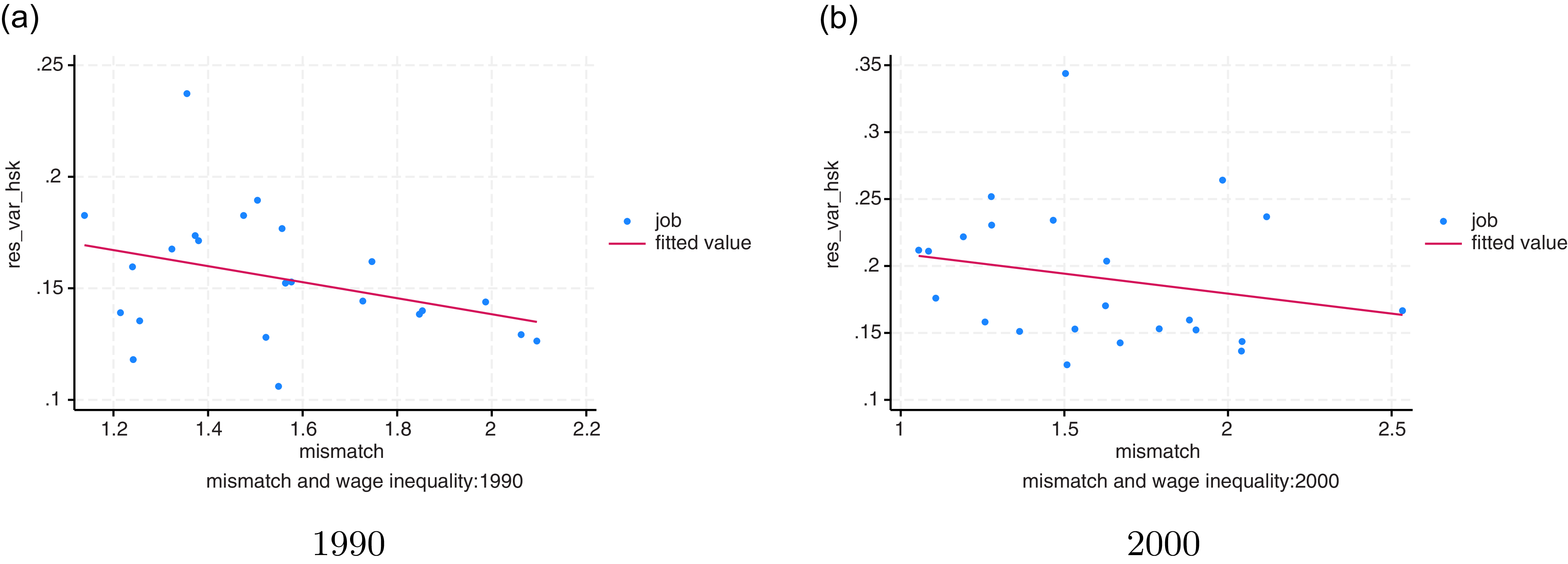

Figure 4. Wage inequality and skill mismatch index.

Notes: In both panels, each dot represents a job(25 jobs in total). The y-axis is the wage inequality. The x-axis is the mismatch index. The left panel is based on 1990 data, and the right panel is based on 2000 data. The coefficients in both panels are

![]() $-0.03$

. Data source: NLSY79 and March CPS.

$-0.03$

. Data source: NLSY79 and March CPS.

Conversely, we find a negative relationship between the wage inequality and skill mismatch index, as shown in Figure 4. Thus, jobs with better matching quality tend to experience higher wage inequality.

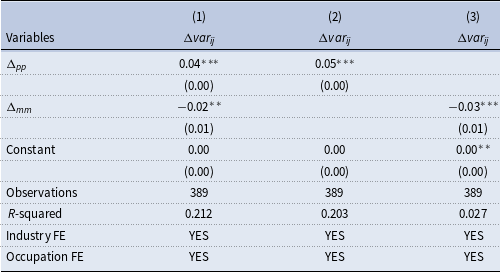

To further explore how performance-pay incidence and match quality increase the rising wage inequality, we first compute the changes in the level of wage inequality, performance-pay incidence, and mismatch index between the current and previous years. We then regress the changes in the wage inequality against the changes in performance-pay incidence and skill mismatch index while controlling for industry and occupation fixed effects:Footnote 13

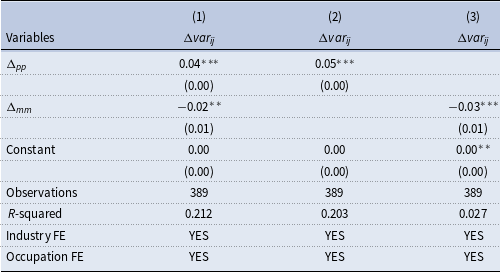

Table 9 presents the results. The positive coefficient on the change in performance-pay incidence (

![]() $\Delta _{pp}$

) implies that rising performance-pay incidence increases the wage inequality. Specifically, if the performance-pay incidence rises by

$\Delta _{pp}$

) implies that rising performance-pay incidence increases the wage inequality. Specifically, if the performance-pay incidence rises by

![]() $10$

percentage points, the wage inequality rise by

$10$

percentage points, the wage inequality rise by

![]() $0.4$

percentage points. Similarly, the negative coefficient on the change of skill mismatch index (

$0.4$

percentage points. Similarly, the negative coefficient on the change of skill mismatch index (

![]() $\Delta _{mm}$

) implies that improving matching quality (lowering mismatch index) increases the wage inequality. The results are robust and significant if we let one or both variables be the regressor. Furthermore, Table A.14 reports significant results when we replace performance-pay incidence with performance-pay ratio.

$\Delta _{mm}$

) implies that improving matching quality (lowering mismatch index) increases the wage inequality. The results are robust and significant if we let one or both variables be the regressor. Furthermore, Table A.14 reports significant results when we replace performance-pay incidence with performance-pay ratio.

Table 9. Performance-pay incidence, skill mismatch and wage inequality

Note:

![]() $\Delta var_{ij}$

denotes the changes in residual wage inequality between two consecutive years.

$\Delta var_{ij}$

denotes the changes in residual wage inequality between two consecutive years.

![]() $\Delta _{pp}$

and

$\Delta _{pp}$

and

![]() $\Delta _{mm}$

is the change in performance-pay incidence and mismatch index between two consecutive years.

$\Delta _{mm}$

is the change in performance-pay incidence and mismatch index between two consecutive years.

Standard errors in parentheses

*

*

* p

![]() $\lt$

0.01, *

* p

$\lt$

0.01, *

* p

![]() $\lt$

0.05, * p

$\lt$

0.05, * p

![]() $\lt$

0.1

$\lt$

0.1

Additionally, we conduct the Firpo–Fortin–Lemieux (FFL) decomposition as in Firpo et al. (Reference Firpo, Fortin and Lemieux2009). Results in Table A.15 and A.16 confirm that performance-pay incidence (mismatch index) is positively (negatively) associated with wage inequality.Footnote 14 Moreover, among other studies, Galindo da Fonseca et al. (Reference Galindo da Fonseca, Gallipoli and Yedid-Levi2020) build a measurement of match quality using vacancy and unemployment information, and find that a high match quality can motivate greater performance pay. We plot performance-pay incidence and match quality using our measurement in Figure A.9 and find they are positively correlated.

Lastly, as the model predicts that the second moment of match quality motivates more performance pay (specified in Section 4), it would be useful to validify this theoretical property. Accordingly, we plot the correlation between the second moment and standard deviation of match quality with performance pay incidence in Figure A.10 and A.11, respectively. The results show that both the second moments and standard deviation of match quality (mismatch) are positively (negatively) correlated with performance pay incidence, conforming with the theoretical prediction.

The empirical analysis presents partial equilibrium results omitting the interactions between different channels and feedback effects via endogenous wage adjustments. Moreover, the results are silent on the counterfactual scenario, thus limiting the ability to conduct rich policy analysis. Hence, this requires a comprehensive structure to discipline the interactions among performance-pay incidence, match quality, and wage inequality, which we explore next.

3. The model

Environment There are

![]() $J$

jobs available in the economy indexed by

$J$

jobs available in the economy indexed by

![]() $j=1,2,\ldots J$

. In each job, two types of positions are offered: fixed- (

$j=1,2,\ldots J$

. In each job, two types of positions are offered: fixed- (

![]() $FP$

) and performance-pay (

$FP$

) and performance-pay (

![]() $PP$

) positions. Workers are heterogeneous in their innate ability

$PP$

) positions. Workers are heterogeneous in their innate ability

![]() $a$

, and choose jobs, positions, and efforts to maximize their utilities. Job characteristics and workers’ abilities are both public information.

$a$

, and choose jobs, positions, and efforts to maximize their utilities. Job characteristics and workers’ abilities are both public information.

Performance-pay position A worker’s effective labor supply in the performance-pay position depends on their ability

![]() $a$

, the job-specific productivity

$a$

, the job-specific productivity

![]() $A_j$

, an idiosyncratic matching premium

$A_j$

, an idiosyncratic matching premium

![]() $\eta$

, and their effort level

$\eta$

, and their effort level

![]() $e$

. Specifically, the effective labor supply is given by

$e$

. Specifically, the effective labor supply is given by

The ability

![]() $a$

follows a Pareto distribution

$a$

follows a Pareto distribution

![]() $a\sim G(a)=1-(\frac {1}{a})^{\theta _{a}},\ a\geq 1,\theta _{a}\gt 2,$

with the minimum ability normalized to one. We assume

$a\sim G(a)=1-(\frac {1}{a})^{\theta _{a}},\ a\geq 1,\theta _{a}\gt 2,$

with the minimum ability normalized to one. We assume

![]() $\theta _{a}\gt 2$

to guarantee finite variance, which is essential for studying wage inequality measured by the variance in log wages. To capture the idea of the quality of skill match, we assume that each worker draws an idiosyncratic matching premium from a job-specific Pareto distribution

$\theta _{a}\gt 2$

to guarantee finite variance, which is essential for studying wage inequality measured by the variance in log wages. To capture the idea of the quality of skill match, we assume that each worker draws an idiosyncratic matching premium from a job-specific Pareto distribution

![]() $\eta \sim F(\eta )=1-(\frac {\underline {\eta _{j}}}{\eta })^{\theta _{sj}}$

defined over

$\eta \sim F(\eta )=1-(\frac {\underline {\eta _{j}}}{\eta })^{\theta _{sj}}$

defined over

![]() $[\underline {\eta _{j}},\infty )$

, where

$[\underline {\eta _{j}},\infty )$

, where

![]() $\theta _{sj}\gt 2$

is the inverse of the tail parameter that captures the dispersion of the matching premium in job

$\theta _{sj}\gt 2$

is the inverse of the tail parameter that captures the dispersion of the matching premium in job

![]() $j$

.

$j$

.

We assume that abilities and the matching premium are distributed independently. Thus, the total effective labor supply in the performance-pay position of job

![]() $j$

is:

$j$

is:

where

![]() $D_{jP}$

is the ability domain for workers, and

$D_{jP}$

is the ability domain for workers, and

![]() $h_{jp}(a,\eta )$

is the effective labor supply from a worker of ability

$h_{jp}(a,\eta )$

is the effective labor supply from a worker of ability

![]() $a$

and matching premium

$a$

and matching premium

![]() $\eta$

.

$\eta$

.

Fixed-pay position A worker’s effective labor supply in the fixed-pay position depends neither on the innate ability nor effort level. It is assumed to be only linear in the job-specific productivity. Precisely, in job

![]() $j$

, the effective labor supply from a worker in the fixed-pay position is

$j$

, the effective labor supply from a worker in the fixed-pay position is

![]() $A_{j}$

. Thus, the total effective labor supply in the fixed-pay position of job

$A_{j}$

. Thus, the total effective labor supply in the fixed-pay position of job

![]() $j$

is

$j$

is

![]() $H_{jF}=A_{j}N_{jF}$

, where

$H_{jF}=A_{j}N_{jF}$

, where

![]() $N_{jF}$

is the employment level in the fixed-pay position of job

$N_{jF}$

is the employment level in the fixed-pay position of job

![]() $j$

.

$j$

.

Production and payment The production function in job

![]() $j$

is a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) aggregator of the effective labor supply from the performance- and fixed-pay positions. Specifically, the output of job

$j$

is a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) aggregator of the effective labor supply from the performance- and fixed-pay positions. Specifically, the output of job

![]() $j$

is given by the following:

$j$

is given by the following:

where

![]() $\frac {1}{1-\gamma }$

is the elasticity of substitution between the labor supply from the two positions—they are substitutes (complementary) if

$\frac {1}{1-\gamma }$

is the elasticity of substitution between the labor supply from the two positions—they are substitutes (complementary) if

![]() $\gamma \gt 0$

(

$\gamma \gt 0$

(

![]() $\gamma \lt 0$

);

$\gamma \lt 0$

);

![]() $\alpha _{j}$

is job specific to reflect the intensity of the fixed-pay position in each job.

$\alpha _{j}$

is job specific to reflect the intensity of the fixed-pay position in each job.

We denote

![]() $w$

as the wages that each worker in the fixed-pay position can earn. In each job

$w$

as the wages that each worker in the fixed-pay position can earn. In each job

![]() $j$

, given wages

$j$

, given wages

![]() $w$

, the representative firm decides the employment level in the fixed-pay position to maximize the revenue net of the payment to workers in the fixed-pay position. That is,

$w$

, the representative firm decides the employment level in the fixed-pay position to maximize the revenue net of the payment to workers in the fixed-pay position. That is,

It is straightforward to show that

![]() $N_{jF}$

satisfies

$N_{jF}$

satisfies

![]() $N_{jF}=\frac {\chi _{j}(w)H_{jP}}{A_{j}}$

, where

$N_{jF}=\frac {\chi _{j}(w)H_{jP}}{A_{j}}$

, where

$\chi _{j}(w)\equiv \left [\frac {(\frac {w}{\alpha _{j}{A_{j}}})^{\frac {\gamma }{1-\gamma }}-\alpha _{j}}{1-\alpha _{j}}\right ]^{-\frac {1}{\gamma }}$

. We show in Appendix D that the total payment to workers at the fixed-pay position,

$\chi _{j}(w)\equiv \left [\frac {(\frac {w}{\alpha _{j}{A_{j}}})^{\frac {\gamma }{1-\gamma }}-\alpha _{j}}{1-\alpha _{j}}\right ]^{-\frac {1}{\gamma }}$

. We show in Appendix D that the total payment to workers at the fixed-pay position,

![]() $E_{jF}$

, is equivalent to

$E_{jF}$

, is equivalent to

![]() $E_{jF}=\tilde {\alpha }_{j}(w)\tilde {A}_{j}(w)H_{jP}$

, where

$E_{jF}=\tilde {\alpha }_{j}(w)\tilde {A}_{j}(w)H_{jP}$

, where

![]() $\tilde {A}_{j}(w)=\left [\alpha _{j}\chi _{j}(w)^{\gamma }+(1-\alpha _{j})\right ]^{\frac {1}{\gamma }}$

, and

$\tilde {A}_{j}(w)=\left [\alpha _{j}\chi _{j}(w)^{\gamma }+(1-\alpha _{j})\right ]^{\frac {1}{\gamma }}$

, and

![]() $\tilde {\alpha }_{j}(w)=\frac {\alpha _{j}\chi _{j}(w)^{\gamma }}{\alpha _{j}\chi _{j}(w)^{\gamma }+(1-\alpha _{j})}$

. We also show in Appendix D that the total output can be expressed as

$\tilde {\alpha }_{j}(w)=\frac {\alpha _{j}\chi _{j}(w)^{\gamma }}{\alpha _{j}\chi _{j}(w)^{\gamma }+(1-\alpha _{j})}$

. We also show in Appendix D that the total output can be expressed as

![]() $Y_{j}=\tilde {A}_{j}(w)H_{jP}$

. Therefore, the residual profit is

$Y_{j}=\tilde {A}_{j}(w)H_{jP}$

. Therefore, the residual profit is

![]() $R_{jP}=(1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j}(w))\tilde {A}_{j}(w)H_{jP}$

.

$R_{jP}=(1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j}(w))\tilde {A}_{j}(w)H_{jP}$

.

While the fixed-pay workers are paid at a pooled wage, performance-pay workers’ payments crucially depend on their contribution to production. Given fixed-pay workers, the production function is linear in human capital in the performance-pay position. Hence, a worker’s contribution to the firm is linear in her human capital. Then, the simplest way to model the payment scheme is that the firm and workers in the performance-pay position share the residual profit. We assume that workers’ bargaining power is

![]() $\mu$

. Therefore, the total payment to workers in the performance-pay position is

$\mu$

. Therefore, the total payment to workers in the performance-pay position is

![]() $E_{jP}=\mu (1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}(w)H_{jP}$

, while the payment to a worker of ability

$E_{jP}=\mu (1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}(w)H_{jP}$

, while the payment to a worker of ability

![]() $a$

and matching premium

$a$

and matching premium

![]() $\eta$

in the performance-pay position is

$\eta$

in the performance-pay position is

![]() $\mu (1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}(w)A_{j}a\eta e_{j}(a,\eta )$

.

$\mu (1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}(w)A_{j}a\eta e_{j}(a,\eta )$

.

Workers A worker’s utility is assumed to positively depend on their consumption

![]() $c$

and negatively depend on their effort level

$c$

and negatively depend on their effort level

![]() $e$

. In addition, workers in the performance-pay position suffer from the job-specific dis-utility of being monitored.Footnote

15

We further assume that a worker’s utility function is linear in consumption and quadratic in the effort level. Specifically, a worker’s utility function from working in the performance-pay position of job

$e$

. In addition, workers in the performance-pay position suffer from the job-specific dis-utility of being monitored.Footnote

15

We further assume that a worker’s utility function is linear in consumption and quadratic in the effort level. Specifically, a worker’s utility function from working in the performance-pay position of job

![]() $j$

takes the following form:

$j$

takes the following form:

where

![]() $b$

measures the degree of dis-utility on effort.

$b$

measures the degree of dis-utility on effort.

![]() $M_{j}$

is the dis-utility incurred from working in job

$M_{j}$

is the dis-utility incurred from working in job

![]() $j$

.

$j$

.

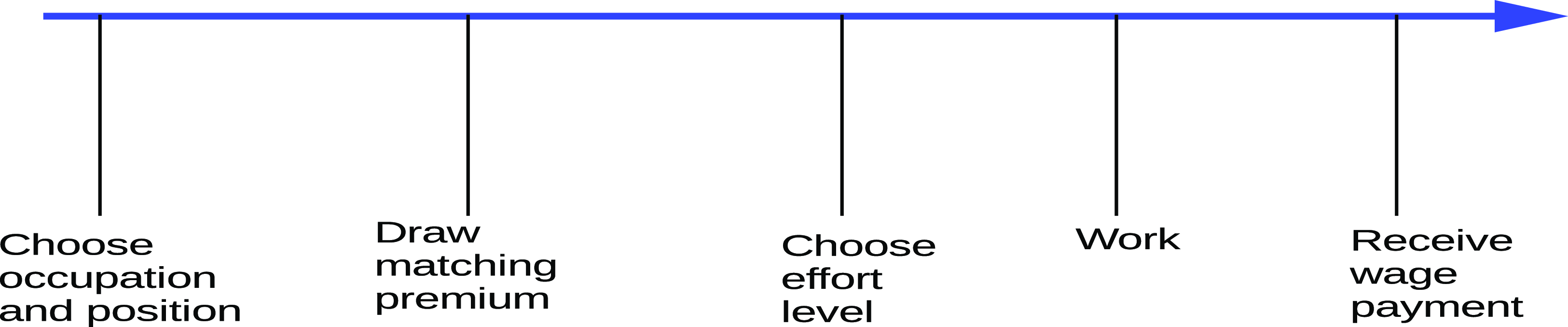

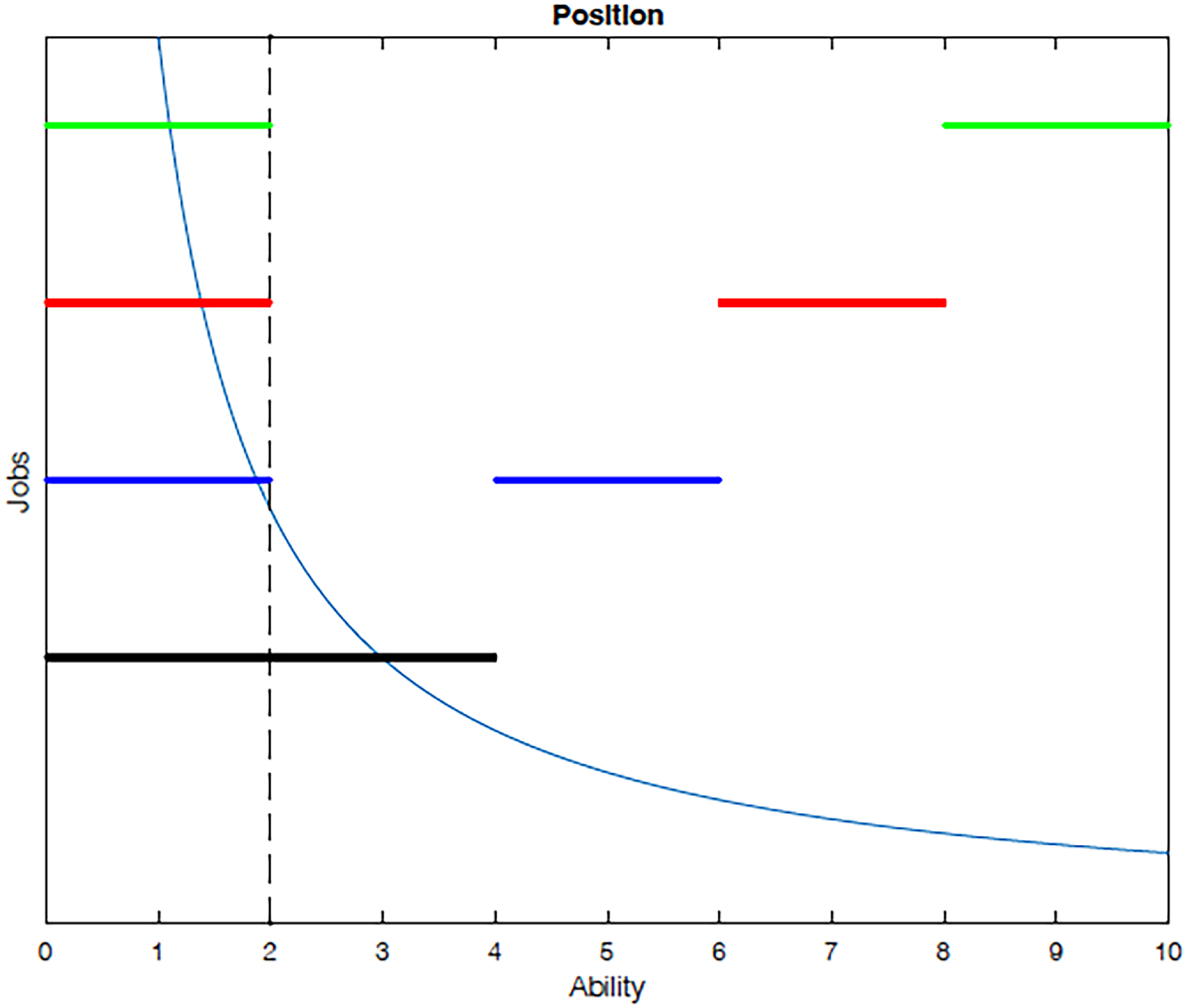

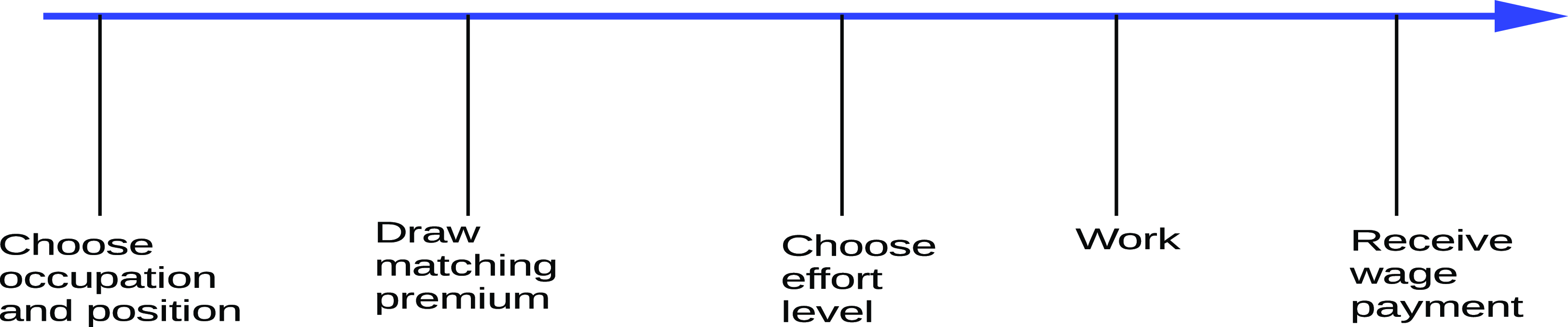

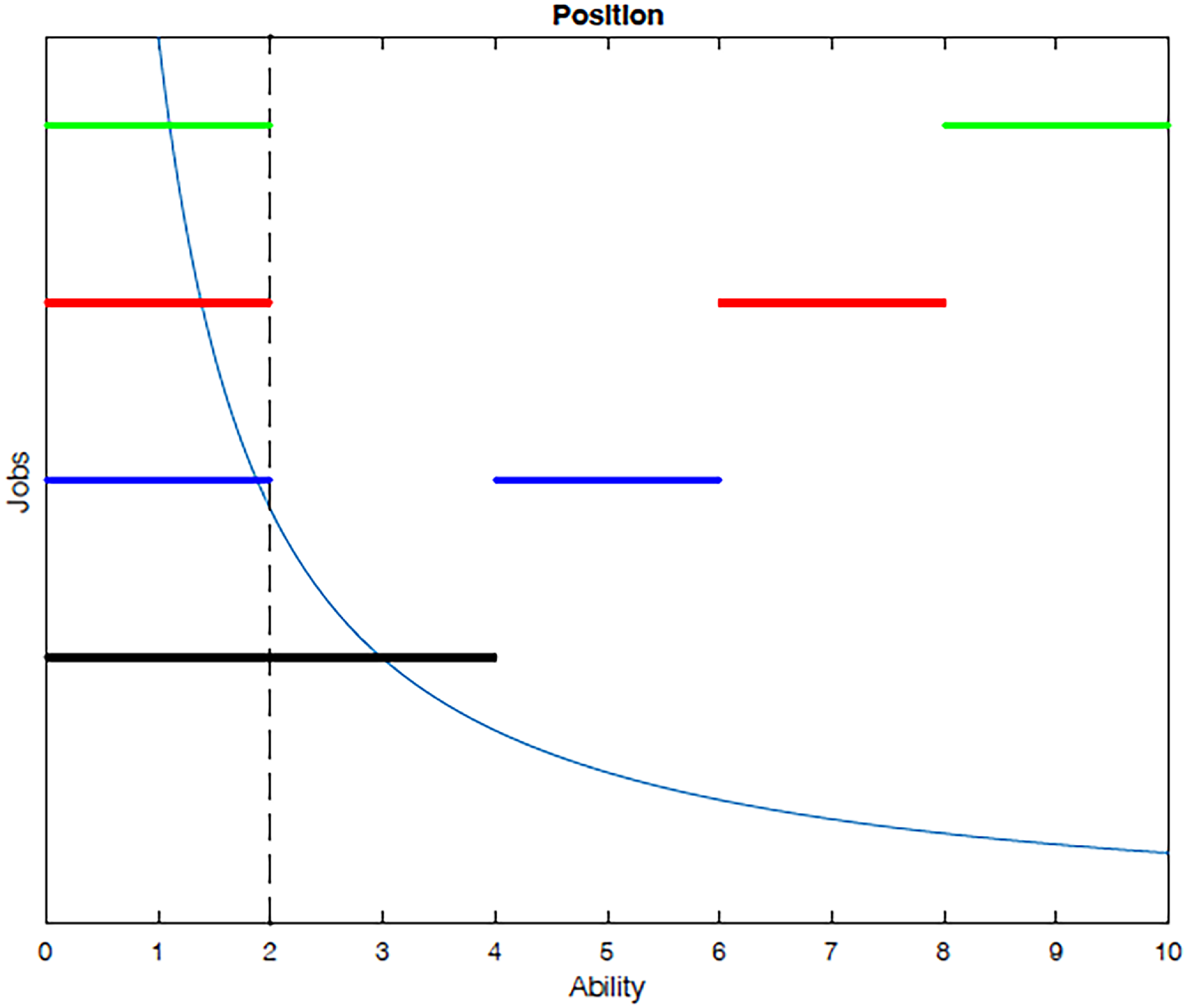

Workers make decisions on jobs, positions, and efforts. Figure 5 summarizes the timeline of the worker’s decision. Workers choose the job and position before the realization of the matching premium. Conversely, the optimal effort level is chosen after workers observe the outcome of the matching premium.

Figure 5. Timeline.

Note: This figure summarizes the timeline for a representative worker in the model economy.

Thus, the ex ante expected utility from working in the performance-pay position of job

![]() $j$

for a worker of ability

$j$

for a worker of ability

![]() $a$

is

$a$

is

![]() $EU_{j}^{P}(a)=E_{\eta }[U_{j}^{P}(a,\eta )]$

.

$EU_{j}^{P}(a)=E_{\eta }[U_{j}^{P}(a,\eta )]$

.

Workers in the fixed-pay position always exert the minimum effort since their pay is independent of their effort level. Thus, a worker’s payoff from the fixed-pay position can be expressed as follows:

Finally, a worker chooses the job and position that delivers the highest expected utility:

Thus, the fixed-pay position is chosen by a worker of ability

![]() $a$

if

$a$

if

![]() $U^{F}\gt \underset {j}{\max }\{EU_{j}^{P}(a)\}$

. Otherwise, a worker of ability

$U^{F}\gt \underset {j}{\max }\{EU_{j}^{P}(a)\}$

. Otherwise, a worker of ability

![]() $a$

chooses the performance-pay position in a job given by

$a$

chooses the performance-pay position in a job given by

![]() $j^{\ast }(a)=\arg \underset {j}{\max }\{EU_{j}^{P}(a)\}.$

$j^{\ast }(a)=\arg \underset {j}{\max }\{EU_{j}^{P}(a)\}.$

Two remarks are in order before turning to theoretical results. First, by focusing on the production side, we assume that all goods are perfect substitutes. While this implicitly assumes away the effects of demand shifts and relative price changes on labor and wage inequality, such simplification is not as vulnerable because we focus on highly education labor only. Second, to guarantee positive demand for all jobs or no empty job, we assume a supermodularity condition (as specified in Proposition10 below). Therefore, all jobs will be perfectly sorted according to workers’ abilities.

4. Theoretical analysis

4.1 Equilibrium

Given the job-specific characteristics

![]() $\{A_{j},\alpha _{j},M_{j},\theta _{sj},\underline {\eta _{j}}\}$

, a sorting equilibrium is described by the wage rate

$\{A_{j},\alpha _{j},M_{j},\theta _{sj},\underline {\eta _{j}}\}$

, a sorting equilibrium is described by the wage rate

![]() $w$

, effort

$w$

, effort

![]() $e$

, and job choice (

$e$

, and job choice (

![]() $j^{\ast }(a)$

) and position (F or P), employment in the fixed-pay position

$j^{\ast }(a)$

) and position (F or P), employment in the fixed-pay position

![]() $N_{jF}$

, and effective labor supply in performance-pay position

$N_{jF}$

, and effective labor supply in performance-pay position

![]() $H_{jP}$

, such that:

$H_{jP}$

, such that:

-

1. Given the wage rate

$w$

, workers optimally choose jobs (

$w$

, workers optimally choose jobs (

$j^{\ast }(a)$

) and positions (F or p) as in Equation (9).

$j^{\ast }(a)$

) and positions (F or p) as in Equation (9). -

2. Given the wage rate

$w$

, workers’ effort

$w$

, workers’ effort

$e$

solve problems in Equation (7).

$e$

solve problems in Equation (7). -

3. Given the wage rate

$w$

and job and position choices, the effective labor supply from the performance-pay position

$w$

and job and position choices, the effective labor supply from the performance-pay position

$H_{jP}$

is determined in Equation (4).

$H_{jP}$

is determined in Equation (4). -

4. Given the wage rate

$w$

and effective labor supply from the performance-pay position

$w$

and effective labor supply from the performance-pay position

$H_{jP}$

, firms decide employment in the fixed-pay position

$H_{jP}$

, firms decide employment in the fixed-pay position

$N_{jF}$

to maximize profits in Equation (6)

$N_{jF}$

to maximize profits in Equation (6) -

5. The wage rate

$w$

clears the labor market, such that:where domain

$w$

clears the labor market, such that:where domain \begin{equation*} \sum _{j}\int _{a\in \{D_{jF}\cup D_{jP}\}}dG(a)=1, \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \sum _{j}\int _{a\in \{D_{jF}\cup D_{jP}\}}dG(a)=1, \end{equation*}

$D_{jP}$

and

$D_{jP}$

and

$D_{jF}$

are the ability domains for workers in performance and fixed-pay positions, respectively, and the total labor force is normalized to 1.

$D_{jF}$

are the ability domains for workers in performance and fixed-pay positions, respectively, and the total labor force is normalized to 1.

4.2 Analytical results

Next, we solve the worker’s decision in a backward fashion:

-

• (Stage 2) We first solve the effort exerted by a worker of ability

$a$

given that the performance-pay position has been chosen and matching premium draw has been realized.

$a$

given that the performance-pay position has been chosen and matching premium draw has been realized. -

• (Stage 1) We then move backward to determine whether this worker would select a performance-pay position and, if so, which job they would take.

Specifically, in Stage 2, a worker of ability

![]() $a$

in the performance-pay position of job

$a$

in the performance-pay position of job

![]() $j$

, after realizing the productivity premium

$j$

, after realizing the productivity premium

![]() $\eta$

, chooses the effort to maximize their utility shown in equation (7). Consumption

$\eta$

, chooses the effort to maximize their utility shown in equation (7). Consumption

![]() $c_{j}$

equals the wage income:

$c_{j}$

equals the wage income:

![]() $c_{j}=\mu (1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}A_{j}a\eta e$

. Thus, the resulting effort level is

$c_{j}=\mu (1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}A_{j}a\eta e$

. Thus, the resulting effort level is

![]() $e_{j}(a,\eta )=\mu (1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}A_{j}a\eta /b$

.

$e_{j}(a,\eta )=\mu (1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}A_{j}a\eta /b$

.

Substituting in the aforementioned effort level, a worker’s effective labor supply is:

and the ex post utility from working in job

![]() $j$

can be derived as

$j$

can be derived as

In stage 1, before the realization of the matching premium draw, the decision to select the performance-pay position depends on the expected utility:

where

![]() $\tilde {C}_{j}=\frac {1}{2b}((1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}A_{j}\mu )^{2}E_{j}(\eta ^{2})$

and

$\tilde {C}_{j}=\frac {1}{2b}((1-\tilde {\alpha }_{j})\tilde {A}_{j}A_{j}\mu )^{2}E_{j}(\eta ^{2})$

and

Because this second moment

![]() $E_{j}(\eta ^{2})$

term enters the expected utility from the performance-pay position, we can conveniently use this to measure the match quality in job

$E_{j}(\eta ^{2})$

term enters the expected utility from the performance-pay position, we can conveniently use this to measure the match quality in job

![]() $j$

. Our result shows that match quality positively depends on both the job-specific minimum matching premium

$j$

. Our result shows that match quality positively depends on both the job-specific minimum matching premium

![]() $\underline {\eta _{j}}$

and its dispersion measured by the tail parameter

$\underline {\eta _{j}}$

and its dispersion measured by the tail parameter

![]() $1/\theta _{sj}$

. Recall that

$1/\theta _{sj}$

. Recall that

![]() $j^{\ast }(a)$

denotes the job in which a worker of ability

$j^{\ast }(a)$

denotes the job in which a worker of ability

![]() $a$

gains the highest expected utility from the performance-pay position. Thus, the performance-pay position in job

$a$

gains the highest expected utility from the performance-pay position. Thus, the performance-pay position in job

![]() $j^{\ast }(a)$

is selected by a worker of ability

$j^{\ast }(a)$

is selected by a worker of ability

![]() $a$

if and only if

$a$

if and only if

![]() $EU_{j^{\ast }(a)}^{P}(a)\gt U^{F}$

.

$EU_{j^{\ast }(a)}^{P}(a)\gt U^{F}$

.

In summary, the two extensive margins—selection into a performance-pay position and job sorting captured by

![]() $j^{\ast }(a)$

—are interconnected, depending crucially on the worker’s ability

$j^{\ast }(a)$

—are interconnected, depending crucially on the worker’s ability

![]() $a$

and an intensive margin of the match quality measure

$a$

and an intensive margin of the match quality measure

![]() $E_{j}(\eta ^{2})$

. In the sorting equilibrium, all margins, in addition to general job productivity, affect the wage dispersion within each job.

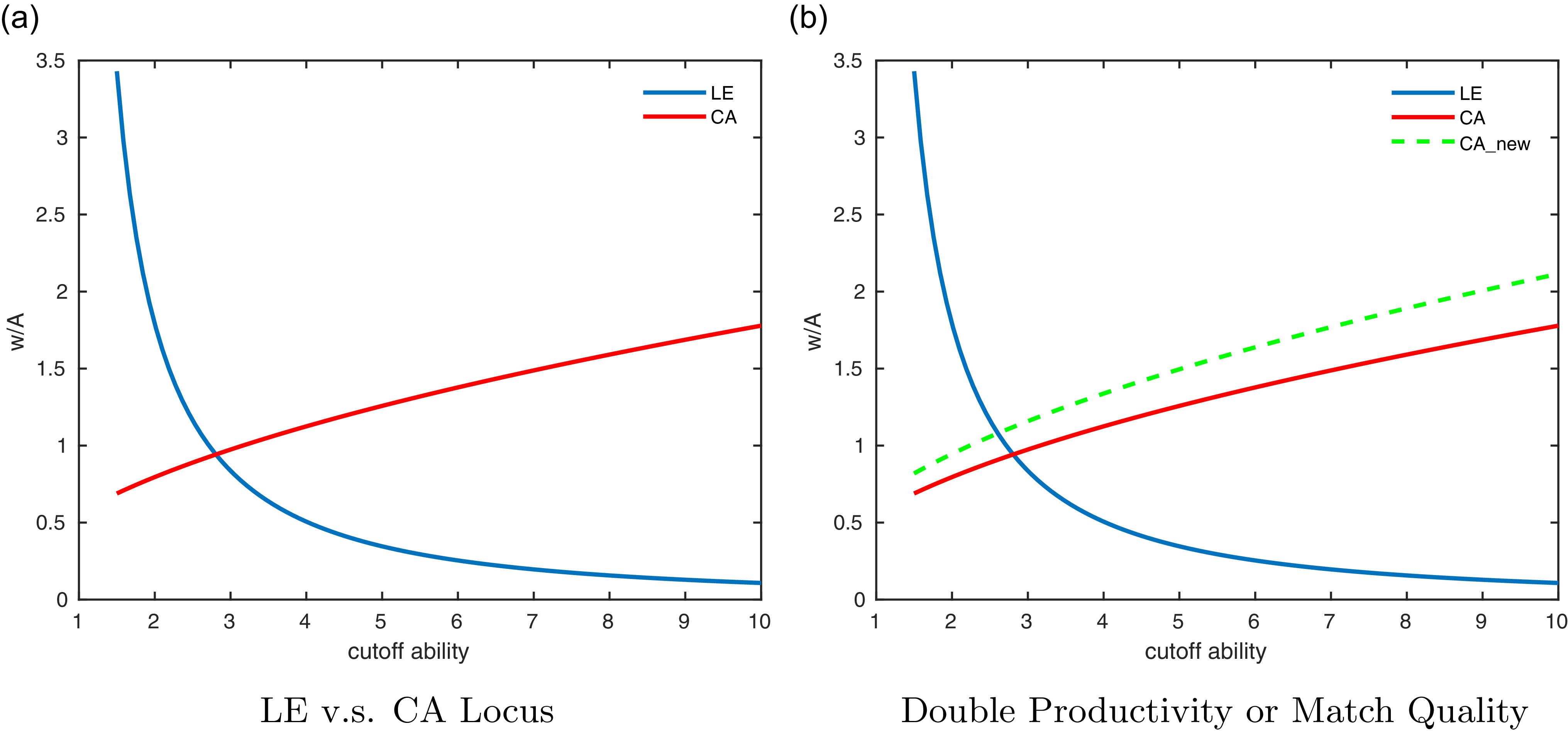

$E_{j}(\eta ^{2})$