I. Introduction

Max Nelson’s study of beer in European antiquity argues that beer drinking in ancient Greece is feminine and foreign.Footnote 1 The evidence for beer as an inherently gendered drink in early Greek engagement with beer-drinking cultures is scanty, however. In the Archaic and Classical periods, there are only two explicit presentations of beer drinking as effeminate, and both appear in contexts engaged with the specific project of defining the boundaries of appropriate masculinity. Elsewhere references to beer drinking in archaic and classical literature simply mark drinkers as non-Greek and thus serve as ethnic indicators without gender implications. In post-classical Greek and Roman commentaries on beer drinking, beer can accumulate gender markers that are inherent to the beverage itself;Footnote 2 for the early Greek tradition around beer drinking, however, beer is inherently foreign (i.e. ‘not Greek’) and is only gendered in some contexts.Footnote 3

This article investigates the question of beer drinking in Greek literature from the Archaic and Classical periodsFootnote 4 and explores how references to beer consumption contribute to the construction of social identities. Where does beer drinking appear in extant archaic and classical literature? What does the consumption of beer mark for both the consumers of beer and those receiving the image of beer consumption? How do the various connotations that beer drinking carries in the different contexts in which it appears operate? And what does all this tell us about how archaic and classical Greek identities worked?Footnote 5

I proceed roughly chronologically and by genre, beginning with Archilochus 42,Footnote 6 where the poet defines his sympotic audience as ‘Greek’ and ‘male’ by conflating beer drinking (‘foreign’) with performing oral sex (‘feminine’), thereby opposing the elite adult men of the sumposion to non-Greek men and women in general. I then move to an examination of beer drinking in the ethnographic and historiographic tradition. In these works, beer drinking is exclusively a marker of non-Greek status, something also seen in the extant fragments of Athenian drama. The exception to this last group is Aeschylus’ Suppliants, where in the fight for control of the Danaids, the Egyptian preference for beer offers an opportunity for Pelasgos to feminize his opponents and deny them access to the fifty marriageable women under his protection.

I argue that beer indicates marked, non-Greek ethnicity and/or locationFootnote 7 in opposition to the unmarked Greek norm of wine.Footnote 8 In contexts where the social identities under construction define a peer group of adult Greek men as ‘male’ and ‘Greek’,Footnote 9 the consumption of beer versus wine can become part of the project of defining participants as ‘male’, ‘Greek’ and ‘rational’ so that beer becomes ‘feminine/effeminate’ as well as ‘foreign’.Footnote 10

The use of wine and beer consumption as identity markers in Greek literature is part of a general trend whereby food and drink function to delineate group and ethnic boundaries.Footnote 11 Water is the only liquid biologically necessary for human survival, hence choices in what to drink are socially and culturally constructed and can be deployed as identity markers to distinguish one group from another. Decisions to discuss other people’s drinking practices and alcohol consumption choices are also part of the project of a group’s collective identity rhetoric, defining the ‘us’ via their own drink choices as well as by the choices of other people, often a ‘them’ who oppose the ‘us’.Footnote 12

This article argues that traditional arguments that beer is both foreign and effeminate need to be nuanced. The investigation of the contexts in which beer drinking appears demonstrates that beer always marks its consumers as non-Greek, or at the very least as being in a non-Greek environment, in the Archaic and Classical periods. Furthermore, contrary to previous readings of archaic and classical reception of beer consumption,Footnote 13 the evidence shows that beer is not an inherently effeminate substance in and of itself but rather that its consumption offers a variety of identity markers to define the Greek (and elite, male) group of the author detailing the beer consumption and his audience. In specific contexts where masculine identity is at stake or where there are other gendered elements at play, then beer can effeminize its consumers as its otherness exacerbates other identity work at play. Finally, I will suggest that, from the archaic and classical perspectives of our sources, the problematic overtones of beer often come not from any inherent qualities of the drink itself but rather from the method of consumption, namely the use of a straw from a communal vessel or a spout on an individual beer jug.

II. Archilochus 42 and the Greek male symposiast

Archilochus 42 is quoted by Athenaeus to demonstrate the use of the term brutos (‘beer’) and so starts mid-line:Footnote 14

ὥσπερ αὐλῶι βρῦτον ἢ Θρέϊξ ἀνὴρ

ἢ Φρὺξ ἔμυζε·Footnote 15 κύβδα δ’ ἦν πονεομένη

… just like a Thracian or Phrygian man sucks brutos with an aulos; she was bent over, working hard.

The sexually charged language (κύβδα, πονεομένη)Footnote 16 connects the comparison being drawn in the fragment to a familiar erotic scene, where a woman is penetrated from behind (see fig. 1); the comparison to beer drinking via an aulos adds fellatio to the sex acts being performed. Both positions for sex workers featured on sympotic pottery,Footnote 17 and Archilochus’ lines here verbally complement the images on the cups he and his audience (or those of a later performer) may have been drinking out of or had used in the past. The sexual imagery evoked here, when combined with the reference to beer drinking, is also evocative of Mesopotamian pornographic scenes where a woman drinks beer from a straw while adopting a partially bent over position as she is penetrated from behind.Footnote 18

Fig. 1. Attic Black-Figure Droop Cup by the Wraith Painter (ca. 520 BCE) with scenes of male-female sex along the exterior (side B). The Getty Museum, 77.AE.54. Image from the Getty (public domain): www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103TCX.

Archilochus 42 offers the image of a woman engaging in sex with two partners as a foil to the male symposiasts who listen to his verses. Their mouths are for speech and the ingesting of wine, hers for sex and semen; she stands while the men recline or she bends over as they stand over her; they penetrate, she is penetrated. In addition, then, to verbalizing the sexual imagery of sympotic pottery, Archilochus’ lines also replicate and thereby reinforce the gender and status hierarchies of sympotic seating. The male symposiasts recline or stand over female sex workers, who take bent-over positions to serve the free, adult men who dominate sympotic space.

In addition to defining male symposiasts against the feminine other, these lines also group the symposiasts as Greek against non-Greeks, specifically Phrygians and Thracians. The Phrygian and Thracian to whom the woman is compared are explicitly and emphatically male; not only does Archilochus use the masculine form of the ethnonyms, Θρέϊξ and Φρύξ (‘Thracian man’ and ‘Phrygian man’, respectively), but he also ends the first line with ἀνήρ (‘man’). The use of the former makes the latter redundant semantically, and so ἀνήρ, which is already emphatic by line position, becomes doubly so. The heavy insistence that the comparandi to the woman are non-Greek men emasculates the Thracian and Phrygian men via the comparison to a woman performing oral sex while being penetrated from behind even as it insists on their male gender and non-Greek ethnicity.

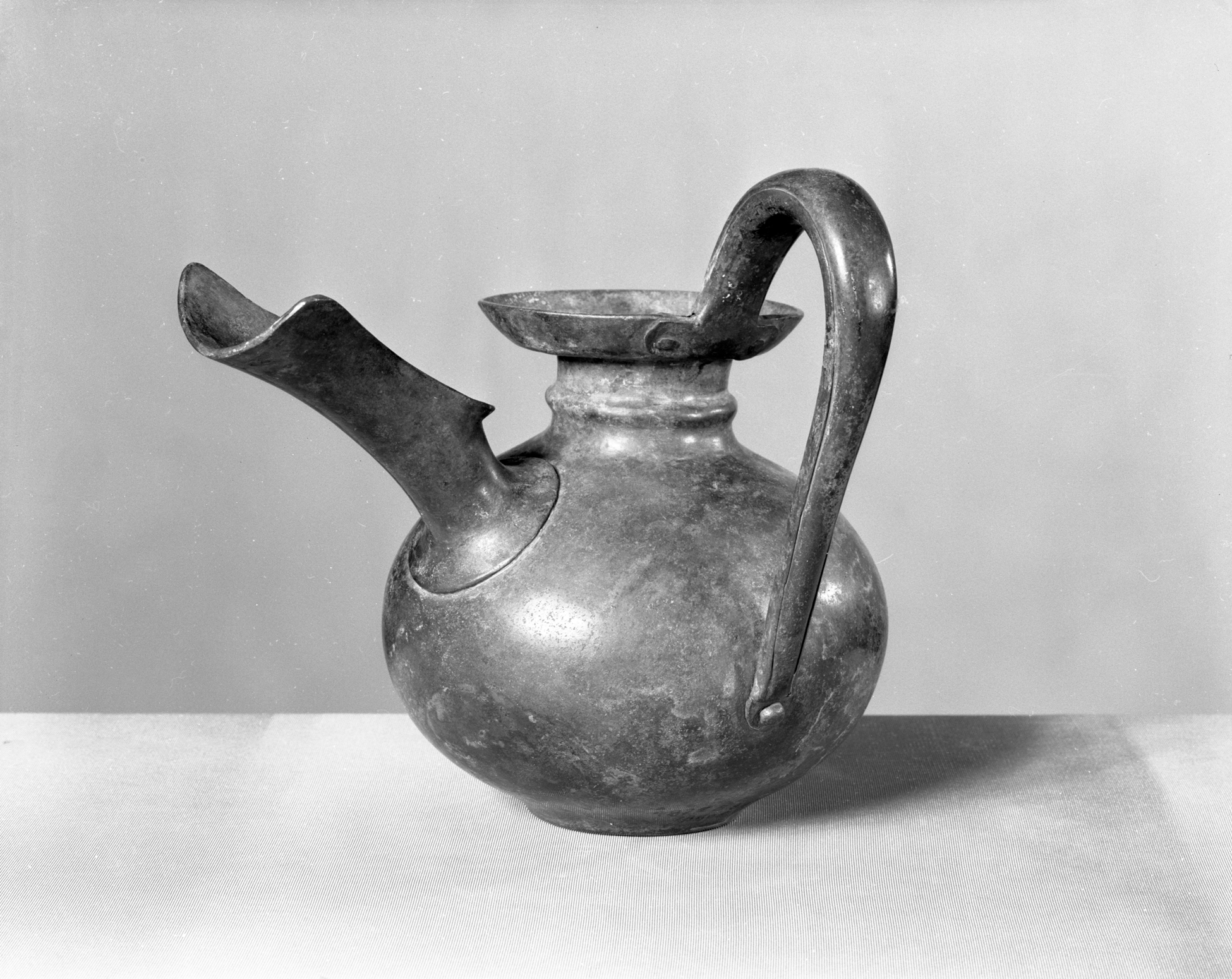

The comparison between the woman and the Thracian and Phrygian men focuses on two parallel acts: the latter two drink beer, the former performs fellatio. Iconography from Mesopotamia and Egypt points to straws as the dominant manner of consuming beer: the straw was inserted below the unfiltered debris which rises to the top of the beer vessel, allowing the drinker to obtain a ‘filtered’ drink (see fig. 2; cf. Xen. An. 4.5.26–27, discussed further below).Footnote 19 Beer was also, however, consumed from personal jugs, often rounded, that had a spout or built-in straw with internal sieves. The Gordion excavations indicate that such jugs were used in Phrygia, and G. Kenneth Sams has suggested that the αὐλός in Archilochus 42 could refer to the spout of one of these jugs, providing a more compelling joke ‘by reason of their greater size’ and bulbous form (fig. 3).Footnote 20 The αὐλός, then, could refer to a straw inserted into a communal vessel or the spout of a personal beer jug;Footnote 21 either way, the comparison to oral sex is an easy one to make.

Fig. 2. Watercolour by Piet de Jong from the Painted House, Gordion (1957); two standing figures with a third kneeling and holding a jug with tube. Courtesy of the Penn Museum Gordion Project, image no. 153733.

Fig. 3. Sieve-spouted jug from Tumulus MM, Gordion. Courtesy of the Penn Museum Gordion Project, image no. 76478.

The use of the αὐλός enables Archilochus not only to reinforce the connection between the woman and her non-Greek male counterparts but also to make a metasympotic reference.Footnote 22 The αὐλός in line 1 functions to refer both to the straw or spout the men drink through and the penis the woman sucks, while simultaneously nodding to the musical accompaniment of sympotic activities.Footnote 23 This reference to the aulos as the musical partner to elegy and sympotic poetry may also add an additional gendered marker to the characterization of the Thracian and Phrgyian men: those who played an actual aulos were young women who were frequently eroticized in Greek art and may have also performed sex work as part of the sympotic activities for which they could be contracted.Footnote 24 The myth whereby Athena invents and then discards the aulos because she did not like the way it distorted her face may also refer back to the association between the different types of aulos ‘playing’: in seeing herself, cheeks puffing in and out, the virgin goddess disdained to look like a sex workerFootnote 25 and so discarded the instrument, at which point it was collected by a satyr. In sum, then, non-Greek men drinking beer look like women performing fellatio or girls playing the aulos, who also look like they are engaged in oral sex.

The Thracian and Phrygian men are thus othered in opposition to Archilochus and his Greek companions on a number of levels. They drink beer rather than wine; they drink using straws/spouts and not cups; and the use of straws/spouts presents visual similarities to fellatio, which invites the comparison to the woman ‘bent over, working hard’. The use of ethnonyms with the reference to beer drinking presents two non-Greek ethnic markers, while the difference in drinking vessel reinforces the gendered component of the comparison; together, these markers fully separate the Phrygian and Thracian men from their Greek counterparts. By inviting the comparison between those who drink beer and perform sex work, non-Greek men are equated to (Greek) women, while (Greek) women who perform oral sex are likened to non-Greek men.Footnote 26 The two others for the male, Greek symposiasts are conflated, two sides of a coin in much the same way as Janiform jugs, which have a woman’s head on one side and an Ethiopian or other visibly non-Greek man on the other.Footnote 27

In defining the two others to the Greek man via sex acts and alcohol consumption, Archilochus 42 engages in sympotic practices of defining symposiasts as both ‘male’ and ‘Greek’. Archilochus’ comparison of Thracian and Phrygian men is pejorative and paints beer consumption in a demeaning light. His use of ethnic customs furthers sympotic identity work aimed at constructing the masculine, Greek group, and it thus differs from most other treatments of beer drinking from the Archaic and Classical periods. In the prose ethnographic and historiographic traditions, beer drinking appears as a neutral marker of ethnic difference, while in Athenian drama we have a few mentions of beer and beer consumption that mark non-Greek ethnicity, only one of which is clearly pejorative and gendered.

III. Beer outside the sumposion: ethnography and historiography

With the exception of Herodotus and Xenophon, references to beer in archaic and classical texts are primarily preserved by Athenaeus, who includes the following comments on brutos from Hellanicus and Hecataeus (Athen. 10.447c–d = Hellanicus FGrH 1 F 66; Hecataeus FGrH 1 F 154):

Ἑλλάνικος δ’ ἐν Κτίσεσι, καὶ ἐκ ῥιζῶν,Footnote 28 φησί, κατασκευάζεται τὸ βρῦτον, γράφων ὦδε· πίνουσι δὲ βρῦτονFootnote 29 ἔκ τινων ῥιζῶν, καθάπερ οἱ Θρᾷκες ἐκ τῶν κριθῶν. Ἑκαταῖος δ’ ἐν δευτέρῳ Περιηγήσεως εἰπὼν περὶ Αἰγυπτίων ὡς ἀρτογάγοι εἰσίν ἐπιφέρει· τὰς κριθὰς ἐς τῖ πῶμα καταλέουσιν. ἐν δὲ τῇ τῆς Eὐρώπης Περιόδῳ Παίονάς φησι | πίνειν βρῦτον ἀπὸ τῶν κριθῶν καὶ παραβίην ἀπὸ κέγχρου καὶ κονύζης.

Hellanicus says in the Foundations that bruton is prepared from roots, writing as follows: ‘they drink bruton from certain roots, just as the Thracians from barley’. And Hecataeus in the second book of the Periegesis reports, speaking about the Egyptians, that they are bread-eaters: ‘they grind barley into some drink’. And in his Periodos of Europe, he says that the Paionians drink brutos from barley and parabiē Footnote 30 from millet and fleabane.

Both Hecataeus and Hellanicus use brutos to refer to a non-Greek drink made from barley consumed by Thracians and Paionians; the drink can extend to include brews from roots, though the people who do so are not named.Footnote 31 There is nothing in the above texts to indicate that brutos suggests anything more than ‘not Greek’ and possibly ‘northern’ as the Egyptian barley drink is not called brutos by Hecataeus. Athenaeus’ quotations are brief, so we cannot rule out a later pejorative discussion of beer consumption that was not included, but based on what we do have, the consumption of brutos appears only as an ethnic marker for these two authors. The explicit and insistent identity building around sympotic, masculine identity that Archilochus engaged in during the seventh century is absent in these sixth- and fifth-century ethnographic descriptions.

The same pattern appears in Herodotus and Xenophon, who introduce beer via the formulations οἶνος ἐκ κριθέων πεποιημένος (‘wine having been made from barley’, Hdt. 2.77.4) and κρίθινος οἶνος (‘barley wine’, Xen. An. 4.5.26–27), where beer appears as an ethnographic marker. In the Histories, the Egyptians are the great beer drinkers, and Herodotus does not comment on beer consumption in Mesopotamia, Thrace or Phrygia despite the fact that these areas receive an ethnographic overview. The Histories has a larger, basic culinary scheme which divides the world into bread-eating, sedentary, agricultural peoples and non-bread eating, nomadic, pastoralist peoples,Footnote 32 and when viewed from this perspective, Herodotus’ description of Egyptian beer drinking may be part of this scheme. It emphasizes Egyptian reliance on grain not just for bread (see 2.77.4 for the Egyptians as ἀρτοφαγέουσι, ‘bread-eaters’), but also for drink, while the formulation ‘wine having been made from barley’ simultaneously distinguishes the Egyptian subgroup of bread-eaters from the other subgroups.

Herodotus’ attribution of beer drinking to the Egyptians alone may also reflect the larger ethnographic point made in book 2 of the Histories, that Egypt does everything ‘opposite’ to the rest of the world (elaborated at Hdt. 2.35): as a place where men work indoors and women outdoors, his description of beer drinking contributes to the exoticization of Egypt.Footnote 33 At any rate, Egyptian beer offers him the opportunity to return to the subject of Egyptian bread, first raised 40 chapters earlier: that the Egyptians eat bread which they call kullēstis (2.77.4) made from olura, a grain which others call zeia (emmer or einkorn, 2.36.2), and they use barley for making wine (2.77.4). Otherwise, Herodotus presents beer drinking in a neutral fashion.Footnote 34

In the Anabasis, Xenophon’s discussion of beer drinking gives more details on the mechanics (something Herodotus does not describe) but is less interested in giving an explanatory agenda around food choices and other ethnographic details. Instead, the Anabasis is more concerned with the practical matters of finding food and feeding an army on the march; complementing this is a concern around hospitality from foreign peoples encountered on the march and whether they will actually be hospitable. Xenophon’s encounter with beer occurs on one such occasion, when the Mossynoikoi entertain the Ten Thousand and hold a feast (An. 4.5.26–27):

ἦσαν δὲ καὶ πυροὶ καὶ κριθαὶ καὶ ὄσπρια καὶ οἶνος κρίθινος ἐν κρατῆρσιν. ἐνῆσαν δὲ καὶ αὐταὶ αἱ κριθαῖ ἰσοχειλεῖς, καὶ κάλαμοι ἐνέκειντο, οἱ μὲν μείζους οἱ δὲ ἐλάττους, γόνατα οὐκ ἔχοντες· τούτους ἔδει ὁπότε τις διψῴη λάβοντα εἰς τὸ στόμα μύζειν. καὶ πάνυ ἄκρατος ἦν, εἰ μὴ τις ὕδωρ ἐπιχέοι· καὶ πάνυ ἡδὺ συμμαθόντι τὸ πῶμα ἦν.

There was wheat and barley and pulses and barley wine in kraters. The barley grains, the ones in the kraters, were level with the brim, and straws were inserted, some bigger and some smaller, without joints. Whenever someone was thirsty, it was necessary for him to take these straws into his mouth and suck. The drink was very strong, unless one should pour in water; the drink was also entirely pleasant for the one accustomed to it.

At this meal, beer (οἶνος κρίθινος, ‘barley wine’) is provided, and Xenophon describes the jointed and straight straws (κάλαμοι) used and the jugs in which the beer is served, which he calls kratēres. Despite it being ‘very strong’ (panu akratos), he comments favourably on the drink. He also appears to take pains to make beer consumption intelligible in Greek terms: the formulation ‘wine (made) from X’ is used, equating the foreign beverage to a familiar one; the beer jugs are made equivalent to Greek mixing bowls for wine; and the beer is akratos, ‘strong’ but also ‘unmixed’, requiring drinkers to ‘pour in’ water, mixing barley wine with water in much the same way wine is mixed with water. The beer krater is communal, leaving the straws as the only item without a sympotic parallel. Xenophon’s insistence that beer is quite good, despite its foreignness, suggests that there was some scepticism about consuming it among his Greek (or Athenian) audience, but where that scepticism may have come from is unclear. In the extant ethnographic and historiographical tradition, then, beer drinking does not carry an inherent pejorative marker.Footnote 35

IV. Beer drinking on the Athenian stage

In surviving Athenian tragedy, there are three references to beer consumption: one where the only solid conclusion is that beer marks non-Greek status of a place or person (Soph. Tript. fr. 610); a second where the drinker is non-Greek and not appropriately masculine in some way (Aesch. Lyc. in Athen. 10.447c); and a third where the reference to beer drinking is pejorative due to the explicit gendered connotations of the scene (Aesch. Supp. 952–53). In comedy, there is a fragment from Antiphanes’ Asclepius and another from Cratinus’ Malthakoi; both are short but seem to indicate at least a familiarity with brutos as adjectival derivatives from the noun are used as an identifier in the first fragment and the basis for a pun in the second.

The fragment from Sophocles’ Triptolemus is minimal, βρῦτον δὲ χερσαῖον †οὐ δυεῖν† (‘to not douse(?) inland brutos’, fr. 610), and only bears a conclusion connecting beer to an inland area. The fragment from Aeschylus’ Lycurgus is longer (fr. 124):

κἀκ τῶνδ’ ἔπινε βρῦτον ἰσχναίνων χρόνῳ

κἀσεμνοκόμπει τοῦτ’ ἐν ἀνδρείᾳ τιθείς.Footnote 36

And from these here he was accustomed to drink brutos, withering in (with?) time,

and he was accustomed to boast proudly, setting this in the men’s banqueting room.

The Lycurgus is the final part of the Lycurgeia, following the Edonians, Bassarai and Neaniskoi, which deals with Dionysus’ arrival in Thrace as well as the death of Orpheus;Footnote 37 the Lycurgus involves the captivity of the chorus of satyrs and seems to follow on from the earlier plot line in the Edonians where Lycurgus imprisons Dionysus’ followers (Bacchants and satyrs).Footnote 38 The Lycurgus may have also involved the conversion of the title character from a beer drinker to a wine drinker.Footnote 39

The participial phrase τοῦτο ἐν ἀνδρείᾳ τιθείς, ‘placing this in the men’s banqueting room’Footnote 40 or ‘considering this to be manliness’,Footnote 41 highlights a concern around manliness, male spaces and masculinity, but from where that concern derives is less certain. The opening deictic τῶνδε lacks an extant referent, and while the τοῦτ(ο) in l. 2 may refer back to the consumption of brutos,Footnote 42 it may equally refer to something else no longer extant. Nelson suggests that there is a play on effeminacy here: Lycurgus, who in the myth about Dionysus’ arrival in Thrace mocks the god for his effeminate appearance, here wrongly considers beer to be ‘manly’ and is himself the effeminate one due to his beer consumption since beer is an inherently feminine beverage.Footnote 43 Gabriel Herman suggests instead that the problem lies with the receptacle from which the beer is consumed; drawing on Nonnus’ presentation of Dionysus and Lycurgus (20.149–81), Herman suggests that the opening τῶνδε refers to cups made from the skulls or tanned skins of Lycurgus’ enemies.Footnote 44 Here, if the τῶνδε does refer to skull cups, the problem would be a display of hyper- or excessive masculinity, while the consumption of brutos would then exacerbate any ethnic foreignness connoted by the choice of drinking receptacle. Greek definitions of appropriate masculinity lay at a mid-point between the extremes of too little (effeminate) and too much (hyper-masculine), both of which are problematic and help to define the control associated with Greek men and appropriate masculinity.Footnote 45

Finally, we should also note that the behaviour the drinker engages in may be the problem. Anacreon 356b advises his audience to leave behind ‘Scythian-style drinking’ (Σκυθικὴν πόσιν), where ‘clattering and shouts’ (πατάγωι τε κἀλαλητῶι) accompany wine, and to embrace moderate consumption accompanied by ‘noble hymns’ (ὑποπίνοντες ἐν ὕμνοις). The moderate wine consumption with (more) sedate vocal accompaniment is implicitly marked as ‘Greek’ opposite the noisy consumption explicitly associated with the Scythians and, returning to the Lycurgus, the unnamed drinker may be as problematic for the proud vaunting he engages in as for the liquid consumed or the possible choice of drinking vessel.

The Triptolemus and Lycurgus continue the property of beer (brutos) as a marked, non-Greek consumable. Both tragedies deal with non-Greek spaces and primary antagonists for the Greek hero and god involved, and the reference to brutos in the fragments seems to operate within the non-Greek settings of the larger myths. The Lycurgus fragment has additional problematic overtones where brutos is linked to some sort of problematic masculinity: whether a hypermasculine display or a misplaced definition of what constitutes andreia, manliness. The brutos drinker can be said to drink opposite the sympotic norm with beer vs wine, proud vaunting vs the trading of riddles and song, and, if Herman’s conjecture for τῶνδε is correct, the use of cups made of human body parts vs ceramics. Yet even without the cups, the beer and behaviour mark the drinker as being non-Greek and engaged in some sort of problematic display of masculinity.

We also have two comic fragments that are relevant to the discussion of perceptions of beer drinking. Athenaeus 11.485b preserves the following from Antiphanes for the mention of lepastē, a large cup associated with men who drink excessively and squander money at parties (Antiphanes 47, Asclepius):

τὴν δὲ γραῦν τὴν ἀσθενοῦσαν πάνυ πάλαι, τὴν βρυτικήν,

ῥίζιον τρίψας τι μικρὸν δελεάσας τε γεννικῆι

τὸ μέγεθος κοίληι λεπαστῆι, τοῦτ’ ἐποίησεν ἐκπιεῖν.

The old woman, weakened entirely and for a long time, the brutikē woman,

pounding some small root and enticing her with a deep lepastē, noble in stature, he made this to drink down.

The old woman here is described as brutikē, a hapax that seems to derive from brutos and mean something like ‘drunk on beer’ or ‘beer sodden’.Footnote 46 She is also ‘weakened’, though whether her weakened state and her drunkenness are connected is unclear; likewise unclear is her ethnicity as it is not identified in the lines that Athenaeus quotes. Nelson suggests that the old woman may be Thracian and that her weakness or illness was caused by her predilection for beer as indicated by brutikē.Footnote 47 But, lacking any further lines or summary, the old woman’s weakness could stem not from her predilection for drink, but from another cause: her age.Footnote 48 At any rate, these lines indicate that a drunken old woman was fodder for comedic play, that perhaps her penchant for drink was treated like an illness or, if the draught is prescribed for whatever has caused her long-term illness, that brutikē could function as an identifier to distinguish one person (here an old woman) from others. We are left with beer consumption as a marker of alterity, but what kind of alterity exactly we cannot say with certainty based on these three lines.

In addition to the Antiphanes fragment, there is a possible reference to brutos in Cratinus’ Malthakoi. Nelson argues that this fragment offers a negative view of beer as effeminate (Cratinus 103):Footnote 49

ἄμουργιν ἔνδον βρυτίνην νήθειν τινά.

[that] someone inside spins the finest silky brutinē fibre.

Hesychius (β 1273) explains βρύτινος as a pun on brutos (τὸ πὸμα τὸ βρύτινον), where:

ἔστι δὲ καὶ ζῶον βρύτον ὅμοιον κανθάρῳ, καὶ τὸ ἀπ’ αὐτοῦ βρύτινον πήνισμα, ὅπερ ὑπ’ ἐνίων βομβύκινον λέγεται.

There is also an animal bruton, similar to a beetle, and the brutinon from it is a silky thread, the same thing which is called bombukinon by others.

Based on this explanation, we are missing the larger context to make the pun intelligible: whether the silkiness or gossamer-like character of the fibre has some quality similar to beer (‘foaminess’?),Footnote 50 or there is some other connection. Perhaps the thread’s colour is the same as brutos or that of the beetle itself, or the pun is furthering the play between κάνθαρος as ‘beetle’ and as a type of drinking cup.

The title Malthakoi (‘Softies’) puts masculinity and effeminacy at the forefront, and thus we could expect a play on beer and feminine otherness as we saw in Archilochus 42. The line above does impose feminine and (if τινά is masculine) effeminate connotations on the person spinning, but such connotations do not necessarily relate to the brutinē fabric, whatever the pun is trying to say. Instead, any effeminate (if τινά is masculine) or feminine (if τινά is feminine) character more likely comes from the fact that this person is spinning, a feminine-coded activity, and that they do so ἔνδον, ‘indoors’, a feminine-coded space. We are thus left with brutos as possibly being familiar enough to base a pun on in the mid-fifth century, where it may also have contributed to the play with implications of the masculinity and effeminacy that the play’s title suggests was a dominant theme. However, the brevity of the fragment precludes us from saying how brutinē could have done so as a pun on brutos.

As noted, Aeschylus’ Suppliants contains the only other use of beer drinking as an explicitly pejorative marker in extant archaic and classical texts. The reference to beer drinking comes at the end of the debate between the Egyptian Herald and Pelasgos, where control over the Danaids, 50 virginal, marriageable women, is at stake (951–53):

Κῆρυξ: εἴη δὲ νίκη καὶ κράτος τοῖς ἄρεσιν.

Βασιλεύς: ἀλλ’ ἄρσενάς τοι τῆσδε γῆς οἰκήτορας

εὑρήσετ’, οὐ πίνοντας ἐκ κριθῶν μέθυ.

Herald: May victory and power go to the males!

Pelasgos: Well, you’ll find that the inhabitants of this land are male, who don’t drink wine from barley.

The use of the male biological sex marker ἄρσην (= ἄρρην) by both the Herald and Pelasgos explicitly situates the argument in the performance in relation to male sex and masculine gender norms. Pelasgos’ choice to include the matter of beer consumption, here formulated through the elliptical formulation πίνοντας ἐκ κριθῶν μέθυ, ‘drinking wine from barley’, thus contributes to the performance of masculine identity as much as it does to the Greek vs non-Greek ethnicity of Pelasgos and the Herald.

The Suppliants as a whole contains a number of assumptions and implications for Athenian identity rhetoric in the first half of the fifth century;Footnote 51 what I will focus on here is the use of beer in the three lines concluding the argument to define Greek men (Pelasgos, the ‘inhabitants of this land’, the Athenian audience) in opposition to non-Greeks (the Herald, Aegyptus’ 50 sons, Egyptians) who are explicitly feminizedFootnote 52 based on their consumption of beer in this scene and this particular tragedy. Male sex and masculinity are at the forefront of the debate, as seen in the use of the adjective ἄρσην by both the Egyptian Herald and Pelasgos and in Pelasgos’ demand as to whether the Herald thought to find a city of women (Supp. 911–14):Footnote 53 the ones who will win and claim the Danaids are those who are male, masculine as opposed to feminine. The Herald does not qualify what is necessary to be labelled ἄρσην, though his statement is couched in the debate so that the unqualified males (τοῖς ἄρεσιν) are to be understood as the Aegyptids. Pelasgos, on the other hand, does qualify ἄρσην: it is the preserve of those who do not drink ‘wine (μέθυ) from barley’, that is, beer; this qualification of male biological sex and masculinity thus rejects the Herald’s association of the adjective with the sons of Aegyptus who, as Egyptians, would be beer drinkers.

The pejorative description of the Egyptians as those ‘who drink μέθυ from barley’ may be gendered even further, or contain the potential to be, if the Suppliants shares Old Comedy’s colloquial use of of krithē (‘barley’) for ‘penis’.Footnote 54 If this double meaning for krithē in Suppliants 953 is accepted, then the surface retort of ‘you’ll find the inhabitants of this land are male since they don’t drink wine from barley’ has the additional qualification of ‘since they don’t suck wine from cocks’.Footnote 55 Whether the double meaning is read into the retort or not,Footnote 56 however, Pelasgos’ response to the Egyptian Herald and his reference to Egyptian beer-drinking habits are emphatically pejorative and gendered.

Pelasgos’ retort and denigration of beer drinking thus contribute to the larger themes at play in the Suppliants, where marriage and sexual relationships between men (husbands) and women (wives) are key issues. Control of women’s bodies drives the plot: the Danaids’ flight from unwanted marriage with and thus control by their cousins moves to their debates with Pelasgos around where to wait and whether he will grant asylum, and ends with the argument between the Herald and Pelasgos over who has the right to claim the Danaids and locate their persons. The characterization of the Aegyptids as violent, aggressive and hubristic casts them as hypermasculine and exemplars of problematic masculinity.Footnote 57 They are out of balance and lack self-control opposite the Argive men represented by Pelasgos, and the Athenian men viewing the play. The hypermasculinity of the Aegyptids causes a pendulum swing to the other extreme with Pelasgos’ retort; as the Aegyptids lack control, they behave like women, so Pelasgos leans in by equating beer drinking to fellatio in ‘the grossest ethnic insult he can contrive’.Footnote 58 The gendered connotations of beer drinking are thus imposed on the Egyptians in order to make Pelasgos’ point: he and the Argives have the right to maintain control of the Danaids as the ones granting protection because they are (appropriately) male,Footnote 59 evidenced by their protection of the suppliant women and their preference for wine, which lacks the penis jokes that beer invites.

V. Beer drinking and constructing the Greek man

This investigation of Greek commentary on beer drinking in the Archaic and Classical periods shows that beer consumption carries an explicit marker of alterity, particularly in regard to non-Greek ethnicity.Footnote 60 In most of our sources beer is consumed exclusively by non-Greeks and associated with non-Greek groups. In Xenophon’s Anabasis the Ten Thousand drink it, but do so in the foreign context of Asia and at a feast with the non-Greek Mossynoikoi. The consumption of beer appears to be a way of enhancing an othered status. However, of all the references to beer discussed here, only two are explicitly gendered in addition to marking non-Greek status: Archilochus 42 and Suppliants 951–53.

The sample size for comments on beer drinking in the Archaic and Classical periods is admittedly small, and conclusions must therefore be cautious. But based on extant texts, the following can be said about beer drinking and its perception by Greek authors and poets in this period. Archilochus 42 and Suppliants 951–53 expand the ethnic connotations of beer drinking (that is, beer = non-Greek) by introducing a gendered element to the identity work being done. Both define their audience as Greek and male in opposition to the non-Greeks they identify via beer drinking and to whom they deny (full) male gender by associating beer drinking with women. By connecting ‘female’ and ‘foreign’ via beer, the two poets construct a definition of ‘Greek’ and ‘male’ based on alcohol consumption preferences.

To conclude, while beer drinking can be gendered and thus used to feminize non-Greek groups (or beer-drinkers generally), its primary connotations in the Archaic and Classical periods are ethnic. It is only in cases such as Archilochus 42 or Aeschylus’ Suppliants 951–53, where masculine status as well as Greek ethnicity are being constructed, that the gendered connotations of beer consumption move from latent to explicit. Finally, Archilochus’ comparison of fellatio and drinking beer from a straw or the spout of a beer jug (the ‘aulos’) suggests that, in the sympotic tradition at least, the problem with beer is not that it is not wine, or any inherent quality of the beer itself, but rather the method of consumption, sucking through a tube of some sort rather than sipping from the broad cup of sympotic wine consumption.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the Classical Association of Canada; my thanks to those who attended and commented on the paper, particularly to Max Nelson. Thanks are also due to Carly Tomblin and Matt Gibbs for their help on earlier drafts, to Kelsey Koon for her assistance on beer-making practices and to Jenn Long for her endless patience in writing group meetings.

Abbreviations

BAPD: Beazley Archive Pottery Database, https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/carc/pottery