Introduction

On 28 October 1615, the New Spanish viceroy, Diego Fernández de Córdoba, penned an alarmed letter to King Felipe III. A Dutch fleet had just attacked Mexico’s Pacific port of Acapulco. Under the command of Joris van Spilbergen, the Dutch sought to capture one of the famed Manila galleons, the Spanish treasure ships that sailed nearly every year between the Philippines and Mexico from 1571 to 1815 laden with silver and luxuriant Asian wares. In response to this brazen assault, Córdoba concluded that ‘it has seemed to me that two platforms should be made as quickly as possible … to defend the port as best as could be done’.Footnote 1 With these words, an urgent quest commenced: to secure New Spain’s vast and exposed Pacific frontier by building the Fort of San Diego to overlook the Bay of Acapulco.

Over the next twenty years, the port transformed. It went from a quiet hamlet that awakened only during the trade season to a bustling centre year-round pulsing to the rhythmic clank of iron tools and the crack of splitting timber. However, all narratives of the fort’s construction and its importance to the defence of the Spanish empire, both past and present, have categorically overlooked the very people who built it. In their thousands, Indigenous men (called indios in colonial documents) arrived at Acapulco from the coasts and hinterlands of what is now the Mexican state of Guerrero: primarily, Tlapa, Igualapa, Ometepec, Chilapa, Xicayan, Zacatula, and Tixtla. Acapulco’s treasury (contaduría) records document important details about these forgotten men who secured Spain’s prized transpacific trade route. Through them, a complex image emerges of the push–pull dynamics at the heart of the repartimientos (rotational forced labour system) in the mountain communities between Iguala to the north and Acapulco to the south. Of utmost importance, they disclose that hundreds lost their health and dozens their lives while labouring at the fort. At a time when the repartimiento had already become a morally indefensible institution partly responsible for the apocalyptic population decline of Indigenous people in central Mexico, it nonetheless retained all of its former intensity in and around Acapulco.

And yet, stopping there leaves only an unfinished sketch. Indigenous people also managed to use the repartimientos’ meagre compensation to sustain their communities by entering colonial Mexico’s emerging silver economy.Footnote 2 Cash payments were critical to the long-term survival of the hinterland communities sandwiched between lands of high agricultural output to the north and high mercantile activity to the south. Furthermore, the arrival of thousands of Nahuatl-, Cohuixca-, Chontal-, Mazahua-, Tlapaneco-, and Mixtec-speaking people at Acapulco shaped the contours and possibilities of cultural exchange at the port.Footnote 3 Desolation is not the only story these repartimientos tell.

Based on some 800 data points from these treasury records, this article offers the first analysis of the repartimientos that built and repaired the Fort of San Diego in the period 1615–35. The recent Pacific turn in the historiography of the global Spanish empire has yet to examine the relationship between transpacific trade and Indigenous labour in the Americas. Indeed, Indigenous subjects that were displaced to new townships, constrained by the repartimientos, and forced to pay tribute are often characterized as immobile or peripheral to the long-distance operations of overseas empire. However, as Nancy van Deusen so abundantly demonstrates in Global Indios – a study of Indigenous enslavement and freedom suits in Spain – ‘the construction of indioness was always relational to other local and global experiences’.Footnote 4 Too often, the lives of marginalized colonial subjects, when they appear at all, are flattened in service of grand-scale histories of trade and empire. Addressing the ensuing silences requires adopting a local lens – and allowing Acapulco to fill the frame – to tell a global history.Footnote 5

I argue that the creation of a Spanish Pacific World, as well as the inter-imperial competition that contested that vision, had profound repercussions for the Indigenous communities of Guerrero. It intensified their connection to Acapulco by enabling new commercial possibilities, just as it bonded thousands to the repartimiento. It tied their fortunes to the galleons and, through those wind-born hulks, to far-off places, like the Visayas, the North Pacific, and the Californian coasts, where galleons split apart. Those ships were, in turn, deeply dependent on Indigenous social, economic, and cultural activities in ways that have only rarely been acknowledged.Footnote 6 The coast became a vector of risk and promise, a source of illness and silver, and a place where people converged and shared knowledge of boisterous powers that thrived on the frontier of the Catholic world.

Some 231 repartimiento rotations built and repaired the Fort of San Diego from 1615 to 1635. These rotations typically lasted between one and two months and averaged 55 people each, with a range from 4 to 572 people. Across the 231 rotations, the treasury records log 2,013 casualties. Most were declared sick. Though numbers gleaned from colonial sources are chronically imprecise, the numerical details of these repartimiento records are exceptional for their mere existence. None of the official documentation on the fort’s construction offers more than a passing comment on the general presence of Indigenous labourers. Even repartimiento casualty rates for the largest public works project in the Spanish Americas – the Desagüe (draining) that emptied the lakes around Mexico City – remain broad estimates divorced from colonial-era sources.Footnote 7

Though one of the most insightful genres documenting colonial labour exploitation, treasury records have been under-utilized, in part, because they are imperfectly catalogued. At the Archivo General de Indias, they usually appear listed only by year and rarely contain any further metadata about their thousands upon thousands of uncurated folios. Inspired by Zeb Tortorici, I hope that in reproducing and analysing the data held in Acapulco’s treasury records this article serves as ‘an act of archiving’ that creates ‘archives in the historiography’ that become ‘accessible to others in ways previously impossible’.Footnote 8

To be sure, Saidiya Hartman cautions us against the morbid impulse to reproduce archives of violence, to ‘open the casket and look into the face of death’.Footnote 9 It is tempting to dismiss colonial accounting as representing the most violent form of ‘archival power’, which silences and, at times, obliterates the agency of colonial subjects.Footnote 10 But to consider the dilemma of the casket, we must first know that there was a cemetery. By locating it, we can then attend to the ‘double gesture’ of ‘straining against the limits of the archive’ and ‘enacting the impossibility of representing … through the process of narration’.Footnote 11 Therefore, critical reproduction is a necessary step in the dialectic that leads to a fuller understanding of what stories have been told, can be told, and should be told using colonial archives.

When read against the grain, treasury records leave important clues that can advance our analysis beyond the sterile distribution of pesos and toward the humans who appear only as numbers. For example, one payment entry from the fort’s construction in 1616 reads,

To 160 indios of the province of Chilapa, 1,295 pesos, 2 tomines, and 6 granos of the said common gold [were paid and] must be [distributed] in this way: 1,010 pesos [and] 2 tomines and 6 granos to 101 indios of the said province who worked 53 days, including the 12 [days] that they were paid to come [to Acapulco] and return [to Chilapa]. 99 of them [the indios] [are] peons and 2 officials – the peons [are paid] a real and a half each day and the officials 2 tomines [each day].Footnote 12 Another 67 pesos [are paid] to 14 indios who were dismissed for being sick [and who] had served 26 days with [i.e. including] 6 [days] that they were given [payment] to come [to Acapulco] at the said [rate of a] real and a half. And another 207 pesos [were paid] to 23 indios who worked 48 days with [i.e. including] 12 [days to come to Acapulco and go back to Chilapa], who were dismissed for being sick [and were paid] at the same rate. The 11 remaining pesos [were paid to] 22 indios, who were given an advance of 4 reales each and who fled, having served for 20 days. All of them worked on the fortifications of the said port [of Acapulco], as it appears in the certification of Juan de Alfaro, interpreter, and Adrian Boot, engineer, who was in charge of the said indios.Footnote 13

Every esoteric sentence of this description revolves around one thing: the distribution of pay to the 160 Indigenous labourers from Chilapa. When read ‘with the grain’, the record unquestionably reduces the lives of these men to the work they performed and their ability or inability to complete it.Footnote 14 Our knowledge of their existence depends entirely on this singular, notarial goal and the pens of the treasury officials that copied the engineer Adrian Boot’s report into their account books. Still, investigative historical work can rebuild some of the missing context of this entry. To reach Acapulco, these chilapeños had to descend over 1,400 metres from a land of forested mountains to the coast. They dug earthworks, split rocks, and cleared ground to construct stone parapets and towers. The entry strongly implies the extreme nature of the labour these men performed and a callous disregard for the lives of the fifty-nine men (37 per cent) who did not complete the rotation.

And yet, there are hard limitations to what can be known. What illnesses did these men contract, or was ‘illness’ a term that included the tactics that Indigenous people used to not have to continue working? What prompted the twenty-two ‘indios’ to flee on day twenty? How did the ‘indios’ interact with other labour gangs toiling at the fort? Finally, what did the repartimiento mean for those who worked its rotations? On these and many other questions, this entry is silent.

Nonetheless, the task of recentring the chilapeños – and, therefore, of reading against the grain – begins by posing questions aimed at the document’s silences. Contextual reading approximates answers. In a classic study of colonial Guerrero, Jonathan Amith argued that Chilapa’s ‘adverse topography’ prevented its residents from relying entirely on agriculture for subsistence and tribute payments.Footnote 15 Like the town of Tixtla on the camino real (royal road) between Mexico City and Acapulco, Chilapa’s economic life depended on trade and services between the capital and the coast. Therefore, chilapeños were engaged in farming during the rainy season and the transport economy between the highlands and the coast during the dry season. Small cash infusions – including from repartimiento wages – allowed these communities to engage in petty commerce, and such activities ‘might well have made the difference between survival and starvation to a large sector of the agrarian population’.Footnote 16 Furthermore, during poor harvests and times of scarcity, the repartimiento could be used to access consistent food rations. Perhaps for the 101 chilapeños who completed the rotation, facing and overcoming the hazards of the fort were the result of a long-term calculation. Spaniards were not the only ones to utilize the repartimiento for their own ends.

In the aggregate, the 231 repartimiento rotations offer a unique opportunity to examine the relationship between inter-imperial competition in the Pacific and Indigenous labour in Mexico, between the Pacific World and Guerrero’s hinterlands. They give a sense of the enormous scale of the construction of the Fort of San Diego and of the repartimientos deployed for the sake of safeguarding the galleons and their precious silks, porcelains, and lacquer that so enraptured the imaginations of colonial elites.Footnote 17

Fort construction, the repartimiento, and global empire

The repartimientos in Acapulco were a response to the vulnerability of Spanish colonies and shipping in the face of foreign incursion, raids, and occupation. The early Spanish defensive strategy for its overseas colonies depended almost entirely on the edification of forts, many of which are still standing today.Footnote 18 Though immobile, forts defended valuable harbours, sea lanes, and choke points. The best of them could also act as deterrents against all but the most ambitious and well-equipped foreign admirals, though even these were never truly the impregnable bastions that colonial officials imagined them to be.Footnote 19

While Spain’s history of fortification in the Americas dates to its earliest settlements, the Crown did not make systematic investments in overseas defensive infrastructure until the end of the sixteenth century.Footnote 20 In the historiography, the relationship between fort construction and the labour of marginalized colonial populations is underexplored yet clearer in the Caribbean context than that of the Pacific. For example, Alejandro de la Fuente has uncovered that ‘most of the actual work [on Havana’s forts] was done by African slaves’.Footnote 21 Moreover, Havana was not atypical in its deployment of enslaved people to build defences. In the circum-Caribbean, colonial defence was closely tied to the slave trade and even facilitated the movement of enslaved people throughout the region.Footnote 22 Not only did Africans and Afro-descendants constitute the majority of the workforce at such sites in the circum-Caribbean, but they were also fundamental to their defence in the militias that formed during the late seventeenth century.Footnote 23 Whether as soldiers or civilians, free or enslaved, these Black port residents were far more likely than any other group to be killed and kidnapped during pirate attacks, as the abduction of nearly 1,500 Afro-descendants during the sack of Veracruz in 1683 demonstrates.Footnote 24

Acapulco, however, was not a Caribbean-facing port. While it did share many similarities with its Caribbean counterparts – not least of which was its fast-growing free and enslaved African and Afro-descendant population – the frequent and large-scale use of repartimiento Indigenous labour provides a useful counterpoint. Acapulco’s treasury records open a new avenue to study the intersections of the repartimiento and the defence of global empire.

***

In Guerrero, the repartimiento must first be understood through the region’s history and topography. From the early fifteenth century, this mountainous zone was a frontier between the central Mexican highlands and the Yope people to the south, who were never fully subsumed under Mexica rule.Footnote 25 Even after the Spanish invasion, it retained its frontier character and relative autonomy from the colonial metropole.Footnote 26 At the heart of this autonomy was the region’s rugged landscape. Outside of the cornfields of Iguala and the mines of Taxco and Zumpango, Spaniards generally considered the land undesirable. For example, in 1590, Chilapa had only ten Spanish vecinos (citizens) and Tixtla just two.Footnote 27

In addition, Indigenous commoners managed to preserve their control of communally held land, in part, by using it to pay tributes to Spanish elites and institutions. Herein lay the double-edged nature of the tribute. Though tributes unquestionably placed enormous burdens on Indigenous communities, they could also be appropriated to reinforce a community’s autonomy. Tributes could not be paid without Indigenous land retention and use.Footnote 28

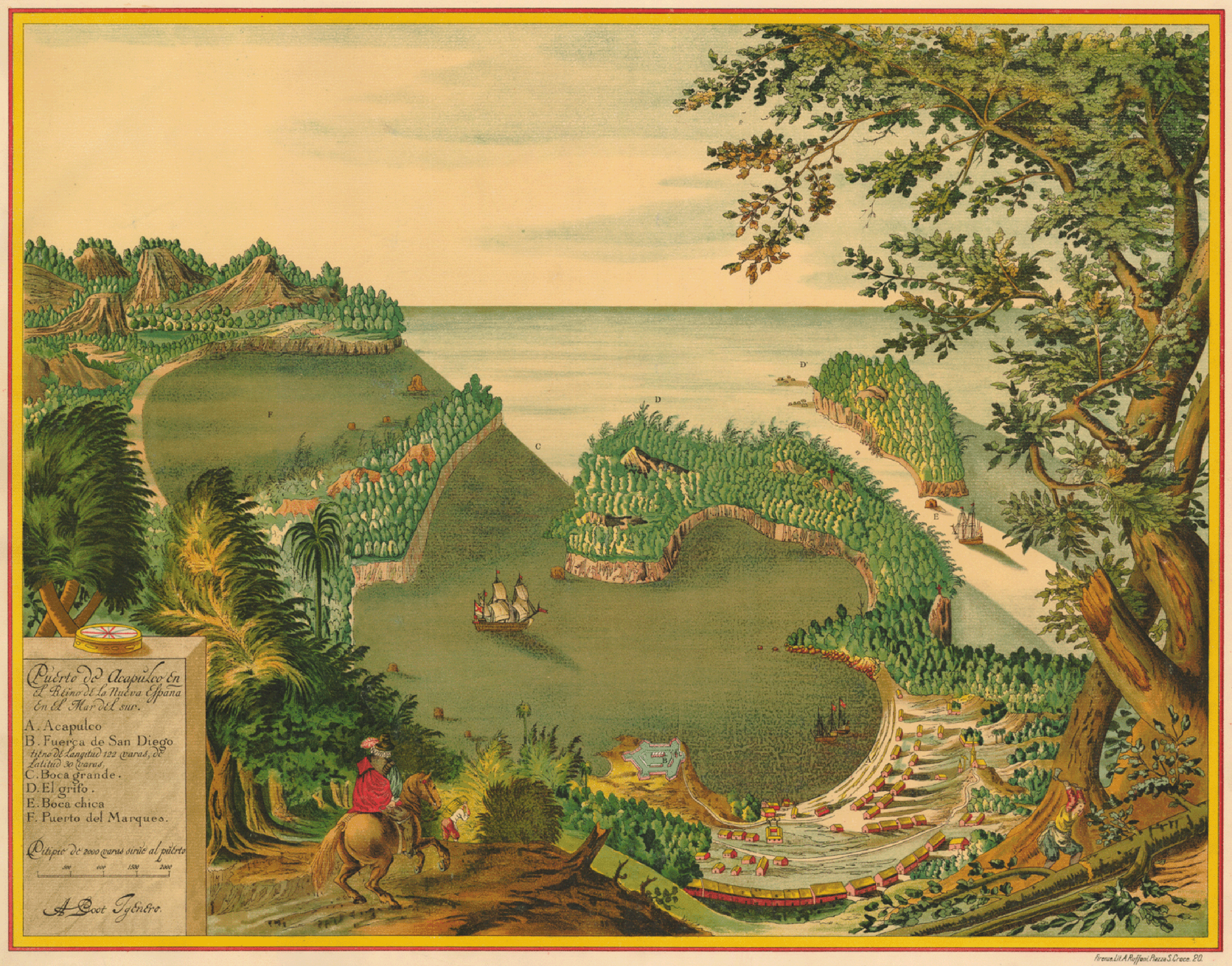

From 1550 to 1605, tribute payments in Guerrero, like those of most of colonial Mexico’s Indigenous communities, changed from goods and services to silver and maize. This shift introduced a new pressure on agrarian communities by imperilling Indigenous ‘control [of] rural resources, particularly grazing land and community-produced grain’.Footnote 29 As a result, many commoners did whatever they could to access wages paid in reales, even extremely low wages paid through the repartimiento. Spanish coins not only paid tributes – thereby protecting usufruct land rights – but they could also be invested in trade.Footnote 30 Indigenous commoners from Chilapa, for example, frequently brought chickens, corn, chili peppers, and white honey to the coast (see Figure 1). They sold these goods for cacao beans, which functioned as a regional currency and were sometimes also converted into reales to pay tributes.Footnote 31 Petty commerce, the transport sector, and inns for travellers were prime targets of such investments given the extreme difficulty of hauling the Manila galleons’ wares through the mountains to reach the urban markets of central Mexico.Footnote 32

Figure 1. In this view of Acapulco – which prominently centres the Fort of San Diego – Indigenous porters haul goods to the port in the dark, bottom-left foreground. Arnoldus Montanus, De Nieuwe en onbekende Weereld: of Beschryving van America (Amsterdam: Jacob Meurs, 1671), 246. Image courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Of course, accomplishing this required surviving the repartimiento. In New Spain, the repartimiento dates to a royal order from 1549 that banned compulsory Indigenous labour without pay. In its place, the Crown proposed ‘a rotational system of hire, with moderate labour, short hours, limited distances of travel, and wages’.Footnote 33 This system drew on a pre-Hispanic, Mexica institution of rotational labour mustering for public projects called cuatequitl (communal work), earlier attempts to control Indigenous labour in the Caribbean, and the New Laws of 1542 that at least nominally banned the outright enslavement of most Indigenous people.Footnote 34 As with nearly all regulatory measures issued from Spain during this period, the repartimiento was implemented largely to the extent that it served the entrenched colonial elite. By the late sixteenth century, the repartimiento, once envisioned as an institution to protect Indigenous subjects, ‘was everywhere one of compulsion and abuse’.Footnote 35 It became yet another coercive demand for labour, albeit on a temporary basis. For Andrés Reséndez, the repartimiento only served to keep Indigenous people in a form of implicit bondage even after the New Laws had designated them as legally free.Footnote 36 Despite numerous calls for reform from the clergy, missionary orders, the viceroy, and the Crown, the repartimiento persisted and even intensified during the first two decades of the seventeenth century.Footnote 37

The three most important types of repartimiento assignment were for agricultural labour, mining, and public works. The repartimientos to build and repair the Fort of San Diego corresponded to the final variety.Footnote 38 Like the Desagüe, the urgency of the construction ensured that it was unaffected by the abolition of repartimientos for urban projects (a type of public work repartimiento) in 1624 and for agricultural work in 1632.Footnote 39 In fact, labour drafts for the Desagüe escalated as the agricultural repartimientos declined, and the drafts for the Fort of San Diego were no different.Footnote 40

Thus, the repartimientos in Acapulco should be understood within this granular, local context. At the same time, their formation cannot be separated from the sprawling scope of the Pacific World. From 1565, the advent of Spanish colonialism in the Philippines and the innovation of west-to-east navigation across the Pacific linked the Americas to Asia in profoundly new ways.Footnote 41 Scholars refer to this zone and the networks it engendered as the Spanish Pacific. A proliferation of books on this subject over the last ten years attests to the inalienable entanglement of the Pacific World and the Spanish Americas.Footnote 42

Kristie Flannery argues that, in Spain’s Pacific borderlands, anti-piracy campaigns often determined the demands of colonial rule on Indigenous and other marginalized populations.Footnote 43 In Manila, local Chinese and Philippine populations were frequently deployed to fortify the city against external and internal threats (real and imagined) since its capture by the Spanish in 1571.Footnote 44 Although Flannery’s focus is the Philippine archipelago, her claim holds true for the Spanish response to the Spilbergen incursion at Acapulco. Fear of foreign incursion quickly evolved into a sweeping effort to mobilize Indigenous labourers across the expanse of Guerrero. The scale of the repartimientos that built the Fort of San Diego made the project Acapulco’s largest public works enterprise until the late eighteenth century. The repartimientos’ importance in Acapulco demonstrates that even canonical subjects in colonial Mexican history remain incomplete when detached from the Pacific World.

Furthermore, it was a Dutch incursion that sparked the drive to build the fort in Acapulco. For scholars of the Spanish Pacific, the field’s defining feature has been the fragility of Spanish control in Asia.Footnote 45 While Spaniards clearly struggled to project power in the Philippines, the supremacy of the Manila galleons themselves until the eighteenth century has remained largely unmarred by anything but environmental considerations ever since William Schurz described the Pacific as a ‘Spanish Lake’ in 1922.Footnote 46 Guadalupe Pinzón Ríos remains one of the few scholars to consider the early effects of hostile navies in the Pacific on New Spanish politics and economic activity, albeit with an emphasis on English privateers.Footnote 47

While there is a substantial historiography covering Dutch–Iberian conflict in the Caribbean, Brazil, and elsewhere in the Atlantic World, the impact of Dutch raids and imperial competition on the Spanish empire’s Pacific underbelly remains largely unexplored.Footnote 48 More than any direct reference to specific attacks, it was the mere possibility of a Dutch raid that most alarmed Spanish officials. Orders to fortify the Pacific were often knee-jerk reactions to this existential threat to one of the most lucrative trade routes in the Spanish empire.

The Fort of San Diego came to represent New Spain’s ability to secure its transpacific empire from foreign interference. In this respect, it succeeded. In 1624, the Nassausche Vloot (Nassau Fleet) under the command of Hugo Schapenham was unable to replicate Spilbergen’s success at Acapulco from just nine years earlier. Even though Schapenham had more ships than his predecessor, the new fort had become a powerful deterrent.Footnote 49 This defensive imperative, in the eyes of Spanish officials, required the callous implementation of the infamous repartimiento. For Indigenous labourers, meanwhile, the violence of the repartimiento was a far more immediate threat than that of any Dutch invasion. This was no ordinary assignment, but surviving it could open the door to new possibilities in the evolving economic world of Guerrero’s hinterlands.

Background: The Dutch occupation of Acapulco in 1615

The success of the Dutch fleet’s invasion of Spanish American waters in 1615 provoked an equal and opposite reaction that culminated in a plan to build the Fort of San Diego in Acapulco. Five months before the arrival of the fleet at Acapulco, it had passed through the Straits of Magellan and entered the so-called South Sea in search of ‘any galleons laden with merchandise’ to ‘endeavor to overtake such galleon, ship or barque’.Footnote 50 This hostile incursion occurred during the supposed Twelve Years Truce (1609–21) of the Eighty Years War (1568–1648), during which the Dutch Republic won its independence from Hapsburg Spain and became a global power. The truce enabled the Dutch to expand their overseas economic and territorial interests in the Americas and elsewhere, with widespread consequences for the inhabitants of Spanish colonies worldwide.Footnote 51

Under the command of Joris van Spilbergen, the fleet proceeded north from the Straits in hopes of intercepting the Manila galleons returning to Mexico from the Philippines. In July, Spilbergen’s ships destroyed the Spanish fleet defending the Peruvian coast at Cañete and inflicted shocking casualties.Footnote 52 Catalina de Erauso, the famed ‘lieutenant nun’, served on the Santa Ana, which went down ‘amidst much shrieking, weeping and wailing’ on the night of 18 July.Footnote 53 Without the Spanish fleet, Spilbergen ruled the South Sea. He could strike any port and pick off any lone treasure ship without fear of retribution.

Though the port of Acapulco was the eastern terminus of Spain’s vast Pacific empire, its defences were minimal. After entering the bay, Spilbergen ordered his fleet to anchor one league from the Spanish garrison peering out from their stone parapet. The alcalde mayor (provincial magistrate) Gregorio de Porras ordered the few cannons at his disposal to fire on the fleet but ‘could not do [the ships] any damage even though some cannonballs reached them, albeit with little force [canssadas]’.Footnote 54 Thus concluded the Battle of Acapulco. The Spaniards had lost without the Dutch ever firing a shot in return.

Over the next week, Spilbergen traded twenty prisoners from Peru for ‘thirty oxen, fifty sheep, and a quantity of fowls, cabbages, oranges, lemons, and the like’.Footnote 55 As soon as Spilbergen ordered the fleet to withdraw from the bay on 18 October to continue its search for the Manila galleons, the engine of the Spanish colonial machine whirred into motion. News of Spilbergen’s week-long occupation of Acapulco quickly reached Mexico City. The Indigenous chronicler known as Chimalpahin included the Dutch attack on the final pages of his xiuhpohualli (yearly count or annals) that covered events in Mexico City from the 1570s to 1615.Footnote 56 He heard that the attackers were ‘wicked people, wrong believers called heretics. It was said that they came [to Acapulco] to wait for the coming of the ship from the Philippines, and there they will rob it of all the goods it is bringing. There was great fear here in the city of Mexico about it.’Footnote 57 For Chimalpahin and many others, an interruption to transpacific trade was a disruption to the life and rhythms of the colonial capital itself.

The viceroy, Córdoba, also felt this ‘great fear’. In his frantic report to the king, however, he failed to mention the obvious: Acapulco already had a fortification, as Spilbergen’s image of Acapulco (see Figure 2) clearly depicts. Over thirty years earlier, in 1582, then viceroy Lorenzo Suárez de Mendoza notified King Felipe II that a specially convened council had determined to build a fort in Acapulco ‘on the headland close to the church and the houses and your Majesty’s warehouses with which they would all be protected’.Footnote 58 The factor Hernando Dávalos y Ayala was credited in 1585 with having overseen the construction ‘with much work and very little cost’.Footnote 59 Nonetheless, the structure had performed so poorly against the Dutch in 1615 as to be unworthy of mention in all of the correspondence pertaining to the construction of the new fortification.

Figure 2. In this chaotic scene, the Spaniards are simultaneously trading with the Dutch and firing on their ships. Spilbergen, Oost ende West-Indische spieghel, No. 14. From the Kelvin Smith Library Special Collections, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, https://catalog.case.edu/record=b3248354.

Córdoba was convinced that if Spilbergen did not intercept the Manila galleons en route to Cabo San Lucas, the Dutch fleet would return to Acapulco. The danger of another attack – along with the bitter memory of Sir Francis Drake’s (1579) and Thomas Cavendish’s (1587) galleon scores – spurred an immediate mobilization to fortify Acapulco. For Córdoba, securing the port meant that ‘the enemies will not be able to easily impede the socorros [aid sent to the Philippines] and trade from the said islands’.Footnote 60 The Spanish colonial presence in the Philippines relied almost entirely on the successful arrival of these socorros. Any interruption to the trade route was an utter catastrophe for Spain’s Pacific empire.

Less than a month after receiving the commission to build the fort, the engineer Adrian Boot submitted the first blueprints to Córdoba. Ironically, Boot himself was Dutch from the city of Delft.Footnote 61 He had initially been recruited to Mexico to work on the Desagüe, but his water management proposals for the capital had already been cast aside for being too costly and too reliant on existing Indigenous infrastructure.Footnote 62

Boot’s blueprint for Acapulco’s fort was similarly ambitious, and it far surpassed even Veracruz’s two towers and wall at San Juan de Ulúa.Footnote 63 It called for five caballeros (towers) connected by five cortinas (curtain walls) in such proportions that the site could be well defended by a small garrison of sixty men. The limiting factor was the uneven and rocky headland (morro), upon which the fort would sit. This point would prove controversial, as the judges of the Royal Court in Mexico City insisted that spending too much time and money on levelling the headland was a waste of resources.Footnote 64 In defence of his plan, Boot added on 3 December that, even though ‘the greatest cost and work is making [the headland] flat’, doing so was a prerequisite of any construction.Footnote 65 According to Boot, ‘it cannot be done any other way’.Footnote 66 Boot’s insistence on combatting the land’s natural topography to enact his vision would have enormous consequences. While modern historians generally consider Boot to have been a very talented if misunderstood engineer in his time, the repercussions of his plan for Indigenous labourers were, simply, disastrous.Footnote 67

Building the Fort of San Diego, 1615–17

Almost immediately after beginning his assignment, Boot began mobilizing Indigenous people from surrounding areas through the repartimiento. He first hired men with military experience to travel to pueblos de indios (Indigenous towns) to announce the order to send labourers to Acapulco. Within a couple of months, Boot had already called up 600 men, a larger repartimiento work force than had ever converged at Acapulco. Problems began almost immediately.

Of the 600, only 350 showed up to work because the royal officials in Acapulco had siphoned off the other 250 for ‘other jobs’.Footnote 68 This illegal diversion of repartimiento labourers for private tasks was common in central Mexico.Footnote 69 Of the 350 remaining, there were only tools for 150. Boot wrote to the viceroy requesting full discretion to deploy the full 600 ‘indios’ as he wished, as well as ‘100 hoes, 100 small picks, 100 small rods, 200 iron shovels, 100 thin spades, 200 crates, 12 masons who are not overseers but who work, [and] 10 men to break rock’.Footnote 70

Illness, however, would prove to be a more severe issue than the tool shortage and the misappropriation of labourers. While Boot did not report directly on any illnesses among the Indigenous labourers, he mentioned in his 24 November letter that ‘a third of the officials are sickly’.Footnote 71 Indeed, the most common stereotype about Acapulco in European writing was its unhealthy environment due to extreme heat. For many Spaniards, Acapulco was the ‘mouth of Hell’.Footnote 72

If even privileged Spaniards suffered from Acapulco’s climate, it would follow that forced labourers compelled to move huge quantities of earth for one or two months at a time would fall sick as well. After all, previous denunciations against the repartimientos, like the Relación de Texcoco (Account of Texcoco, 1582) and the pronouncements of the Third Mexican Council (1585), highlighted the deadly effects of work-induced sickness among Indigenous labourers.Footnote 73 Similarly, Vera Candiani argues that ‘the frequency of [repartimiento] assignments likely weakened [Indigenous workers’] ability to fend off disease’.Footnote 74

Indigenous people travelling to Acapulco from mountainous climates were especially vulnerable. Spaniards had to look beyond the port for Indigenous labour because the toil of servicing the Manila galleons had already begun to depopulate Acapulco’s environs as early as 1576. A royal decree from that year attested that the ‘indios’ near Acapulco ‘have received evil work’ from being compelled through repartimientos ‘to bring to the said port all of its provisions and to put them in its ships and a great number of them have died with the loss of their tributes reaching more than 2,000 pesos in income each year for the mortality and absence of the said indios’.Footnote 75 Undoubtedly contributing to this desolation was the fact that Spanish officials in Acapulco during this period were ordered to pay ‘indio’ labourers a paltry half-real each day.Footnote 76 By the early seventeenth century, only a few Indigenous men and women from the area around Acapulco continued to work full time at the port.Footnote 77 By 1646, the number of ‘indio’ tributaries in Acapulco had dropped by a staggering 80 per cent.Footnote 78

Although it is possible that some or even most of Boot’s initial group of 300 ‘indios’ from the 24 November letter came from Acapulco, almost all who worked on the fort afterwards originated from elsewhere. Most came from highland areas far to the interior like Chilapa with different climates from the coasts. Even in areas like Igualapa that have hot summers, the temperature varies during other times of the year much more than at the port. As scholars working on the Andean mita (rotational forced labour) have long commented, the abrupt change from temperate highlands to hot lowlands and coasts adversely affected the health and well-being of Indigenous labourers. For Steve Stern, this displacement was similarly devastating for the home communities. He writes, ‘The mitayo and his relatives might never come back! Or if they returned, they might not arrive in time for crucial moments in the agricultural cycle, when their labors were most needed. Or the mitayo might return in time, but too sick to put in the work expected of a young man.’Footnote 79 Days-long and weeks-long journeys to Acapulco through near-impassable mountainous terrain all but ensured that Indigenous people who arrived at the port were already fatigued. The same was true of the return journey, especially if the sojourners had already fallen ill.

However, even Indigenous people mobilized from other lowland areas like Zacatula to the north experienced a similarly jarring displacement. The relación geográfica (Geographic Report) completed in the province of Zacatula in 1580 noted that while ‘from their foundations, it seems that their towns are very populated with people, the towns that are there now are very small’.Footnote 80 Many had died of disease (viruelas) and overwork, and ‘almost all of the towns have been moved many times’ due to war and forced resettlement (reducción).Footnote 81 Therefore, even repartimientos that displaced ‘indios’ from similar climates along the coast continued a decades-long process of violent disruption.

The treasury records from Acapulco support the thesis that repartimiento labourers were vulnerable to falling ill and further suggest that this vulnerability engendered resistance. In total, they document 849 instances in the period 1616–17 in which ‘indios’ did not complete their full work rotations due to illness (193), running away (152), or unspecified reasons (504). Since these numbers represent total instances of incomplete repartimiento rotations and not total numbers of people who did not complete them, it is possible that multiple instances refer to the same person if that person worked multiple rotations. For this reason, we cannot know the total number of ‘indios’ who fell sick or ran away, only the numbers per rotation. However, given the high tabulations of incomplete rotations, it is reasonable to assume that the total sum of casualties from these repartimientos was in the hundreds.

Despite such high casualties, a royal official named Gaspar Bello de Acuña bragged in a letter dated 9 May 1616, that ‘no more than one indio smelter from Ixcapuzalco has died’ during the construction.Footnote 82 This was the only mention of an Indigenous casualty in official correspondence related to the fort. Similarly, this death is absent from the treasury records, suggesting the scope of missing information from both genres of documentation.

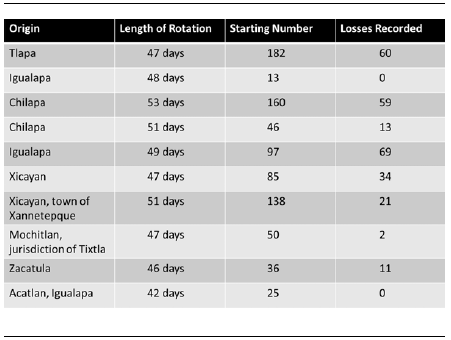

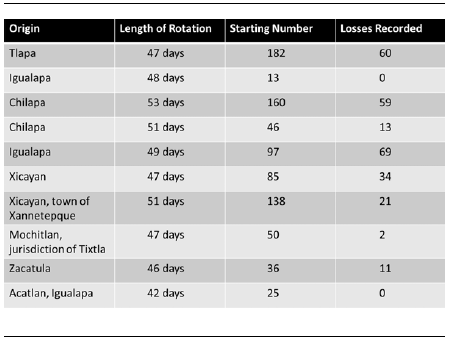

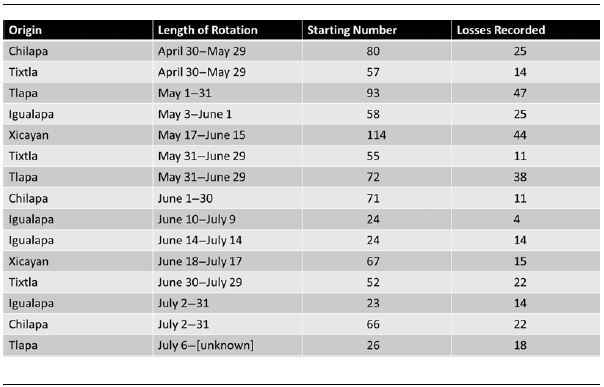

The treasury records have an additional limitation. They only start systematically tracking the fort’s work rotations in 1616 (see Table 1), so there are only a few entries for the initial group of 600 ‘indios’ that began preparing the headland for construction during the last two months of 1615. One surviving entry from December 1615 demonstrates that extreme working conditions were present from the beginning. Thirty-five ‘indios’ were ordered to cut wood in the mountains and suffered a 100 per cent casualty rate (ten runaways, two sick, and twenty-three wounded [eight with their own axes]).Footnote 83 That twenty-three Indigenous labourers had to stop working due to accidents, including eight with possibly self-inflicted wounds, indicates the brutal nature of these repartimientos. For some, self-harm may have been preferable to completing the assignment. It was a violent portent of what followed.

Table 1. The table logs the first ten repartimiento entries of 1616 during the construction of the Fort of San Diego. These high casualties were not uncommon during the first full year of work on the fort. ‘Caja de Acapulco’, 1616, 903, fols. 282–96, Contaduría, AGI, Seville

The vagueness of the records also means that we do not know precisely what ‘illness’ (from se enfermaron) meant. While falling sick was undoubtedly a confluence of displacement and overwork, the category could obscure a wide range of tactics to avoid work as well. Typically, sick ‘indios’ were exempted from paying tribute, so there was a possible incentive for some to find a way to be declared sick toward the end of their rotation to save their earnings. Similarly, the category of ‘running away’ (from se huyeron) contains the practices, knowledge, causes, social relations, and even rituals that preceded and enabled a successful escape.Footnote 84 In 1585, the ecclesiastics of the Third Mexican Council noted that ‘conditions at the place of employment’ during repartimientos ‘are so unendurable that most [indios] prefer to flee without their pay or clothes’.Footnote 85

An additional explanation for the casualty rates is the blistering pace of the work and the conditions born of Boot’s and Acuña’s anxiety to have the fort finished in just a few months. On 4 December, Adrian Boot promised that ‘in five months this work will be finished’.Footnote 86 Over five months later, Gaspar Bello de Acuña reported remarkable progress (‘I do not know that the Romans or the ancients could have finished a work of this grandeur in six months or many more’) but admitted that there was still much to be done.Footnote 87

The viceroy would not declare the fort complete until 15 April 1617, well after Boot’s and Acuña’s predictions. Even Córdoba admitted that the labour involved had been extreme. He wrote that the fort was built on ‘a hill of rocks, open crags, dense vegetation, and so uneven that one could justifiably consider what has been done impossible’.Footnote 88 Levelling the embankments had caused ‘extreme difficulty’.Footnote 89

However, for Córdoba, the headline for the king was that ‘this entire work … has been done in a year, that for being so short [a time] will make its grandiosity [appear] incredible’. Of course, the construction had lasted six months longer than a year. He then wrote that ‘many people who have been in and who are in this port who have travelled through all of Christendom and enemy nations [say] that they have not seen anything greater’.Footnote 90 This celebration of the fort’s grandeur, expressed through the seemingly impossible brevity of its construction, would become the dominant trope about the fort in letters attesting to its completion. With no mention of the builders, the fort’s edification appeared marvellous indeed.

The padrastro, 1632–35

The rushed construction, uneven headland, Boot’s incompetence, and builders being worked to exhaustion contributed to the fort’s persistent problems through the 1620s.Footnote 91 Is it not also possible that some Indigenous labourers sabotaged their role in the fort’s edification, just as they often sought to disqualify themselves from completing their rotations? Colonial forts were plagued with structural faults, not least because the people building them often did not want to be there.

On 25 May 1629, then viceroy, Rodrigo Pacheco y Osorio, wrote to Felipe IV that ‘from Acapulco, they inform me that the fort is damaged and with a very harmful padrastro [obstacle] that was not noticed at the time of its foundation’. As a result, officials would have ‘to come to repair everything’.Footnote 92 While the sources do not fully explain the exact nature of the padrastro, it seems to have been a sinkhole or depression in the fort’s foundation that caused parts of it to collapse. After convening a council with Acapulco’s residents on 21 August 1631, the viceroy elected to follow one of its recommendations: to fill in the padrastro.Footnote 93

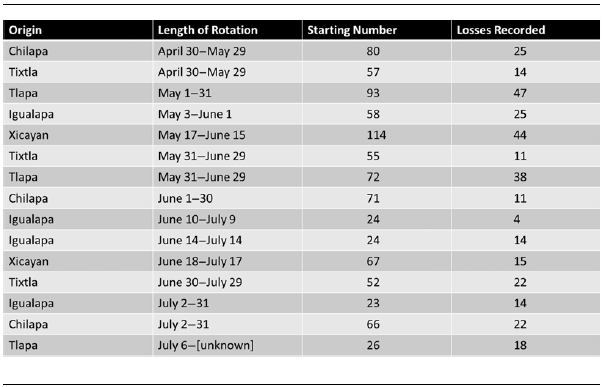

The repartimientos began once again in January 1632 and continued until 31 May 1635. The near-uninterrupted work to fix the padrastro lasted longer than the initial building of the fort itself. Several months after ‘indios’ arrived at Acapulco, the sicknesses began, and the casualty rates for the 1632–35 repartimientos are even higher than those of 1616–17. The treasury records are a nauseating and sobering repetition of numbers and sicknesses that can only ever hint at the grim realities they tallied. Within the first five months (January–May 1632), nine ‘indios’ (four from Tixtla, three from Xicayan, one from Igualapa, and one from Chilapa) had died after an average of twenty-two days of work on the padrastro.Footnote 94 From May–July, which coincided with the onset of the rainy season, casualty rates spiked to an all-time high. Across the fifteen rotations that worked during these three months, 324 illnesses were reported (see Table 2), more than the confirmed total of 193 during the entirety of the 1616–17 repartimientos.Footnote 95

Table 2. Repartimiento rotations, 30 April–6 July 1632. ‘Caja de Acapulco’, 1632, 904, ff. 88v–100v, Contaduría, AGI, Seville

After hearing news of this devastation, the viceroy ordered that the ‘works on the padrastro of the royal fort be stopped during the rainy season’.Footnote 96 Under the constant downpour, mired in the mud, and perhaps without reliable shelters, the conditions that Indigenous labourers faced had been extreme. Undoubtedly, these men also yearned to return to their communities during the crucial and sensitive phase of cultivation when crops received much-needed water. For a merciful three months, there were no repartimiento rotations logged in the treasury records.

On 7 October, the viceroy wrote an upbeat letter to the king: ‘all of the things concerning the fort have been put in good order’. He hoped that the work on the padrastro ‘will be finished promptly … I always make sure to alleviate [the burden on His Majesty] and make progress as much as I can.’Footnote 97 Like his predecessors, though, Viceroy Osorio had over-promised. It would take another two-and-a-half years to finish the repairs, and the speed at which Spanish officials tried to compensate for natural impediments was again felt most acutely by the Indigenous labourers.

On 8 November, the brutal cycle began anew with extreme consequences. Several sobreestantes (overseers) with military experience were hired to ‘make the indios work’, undoubtedly in a vain attempt to make up for lost time.Footnote 98 The next rotation, which lasted until 7 December, suffered a 100 per cent casualty rate: all fifty-two ‘indios’ (from Tixtla) had fallen sick.Footnote 99 In all, 402 ‘indios’ were called back to Acapulco to work rotations in November–December 1632. Of these, 266 had fallen sick, a cruel 66 per cent casualty rate to close out the last two months of the first year of work on the padrastro.Footnote 100 A total of 600 sicknesses, 9 deaths, and 9 unspecified casualties were reported during the repartimientos of 1632 alone.

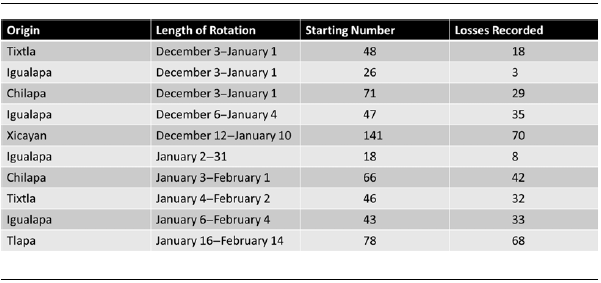

Nonetheless, the true scope of the catastrophe may never be known. The treasury records for 1633 document that 733 ‘indios’ from Tlapa, Tixtla, Igualapa, and Chilapa began their rotations during December 1632 and completed them in January 1633. No casualties were reported. Why would the labour gangs that finished their rotations before the end of 1632 have suffered so dearly, while the ones that began in 1632 and ended in 1633 seem to have gone unscathed? In fact, if we are to believe the records for 1633, only eleven ‘indios’ fell sick in the period January–May 1633.Footnote 101 Then, in 1634, 481 sicknesses were recorded (see Table 3). Given the enormous discrepancy in casualty rates between the end of 1632 and beginning of 1634, it is safe to assume that not all treasury officials dutifully recorded the numbers of ‘indios’ unable to complete their rotations due to illness.

Table 3. The first ten repartimiento rotations of 1634. ‘Caja de Acapulco’, 1634, 905A, fols. 108r–22r, Contaduría, AGI, Seville

On 18 December 1634, the viceroy reported to Felipe IV once more that the work on the padrastro ‘is very close to being done’.Footnote 102 A final round of repartimientos began on 16 February 1635 and finished on 31 May of that year with no casualties recorded. The repartimientos to build and then repair the Fort of San Diego – the bastion overlooking the annual comings and goings of the Manila galleons and their prized merchandise – had finally come to an end. A last group of twenty ‘indios’ from Chilapa ended their rotation on 31 May and did not return.Footnote 103

Cultural exchange

The treasury records craft a twisted image, that of a ravaged generation of Indigenous men from Mexico’s Pacific coast and highlands who built and repaired the Fort of San Diego, who often lost their health and even their lives in the process, and who sometimes found ways to disqualify themselves from repartimiento labour to go back home. Those who survived and remained in good health could benefit from having reales in their pockets to invest in local commerce to ease the burden of their tributes and attempt to eke out a relatively stable existence.

However, these men – never more than numbers in the treasury records – lived more fully than lines of payment can ever indicate. As they converged on Acapulco from all over Guerrero, they brought more than brawn; they brought knowledge. It is possible to approximate how the repartimiento labourers merged spirituality with their work through the writing of Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón. He was an ordained priest living in Atenango and Comala in northern Guerrero during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. He viciously persecuted what he considered Indigenous idolatry and wrote a treatise documenting the practices and incantations that were the ‘most egregious abuses’.Footnote 104 Although the writing skews unequivocally toward condemnation, it remains the single most useful text to understand Indigenous spirituality in Guerrero precisely as work on the Fort of San Diego began.

Of particular importance to the fort’s repartimientos and therefore to this study are the incantations he recorded for cutting wood, carrying loads, and curing disease and bodily fatigue. Ruiz de Alarcón transcribed these incantations in Nahuatl from local informants that he consulted not only in his jurisdiction but all over Guerrero. Then, he translated these sacred scripts into Spanish to present as evidence of widespread idolatry. For example, Ruiz de Alarcón learned an incantation for woodcutting from ‘a very old Indian in my district’ named Juan Mateo.Footnote 105 Like many others, this man began his ritual with piciyetl (tiny tobacco, nicotiana rustica), which he entreated to protect him so ‘that no misfortune [may] befall him’.Footnote 106 Then, the man recited a series of pronouncements in which he described his axe as a tlamacazqui (priest). The axe – as priest – committed an act of ritual sacrifice when cutting wood ‘because of the effect of wounding’ that it performed against its tonal (defined in the text as fate), which was the tree itself. As such, the act of bringing down a tree was a sacred transaction: a life for a new purpose in death. In so doing, the woodcutter invoked the power of the god Quetzalcoatl because only he could grant permission to remove wood from the forests. With this permission, the woodcutters were called Cuauhtalhtohqueh (‘they are the speakers [i.e., the rulers] of wood’).Footnote 107

Once the Indigenous labourers gathered their wood, stone, or earth to deposit elsewhere, they might have conducted a ritual for carrying heavy loads. As with woodcutting, they began with piciyetl to prevent misfortune. When the porter turned to the load, he spoke gently, ‘Let me test you. Let me lift you up. How heavy are you?’Footnote 108 After once again channelling the power of Quetzalcoatl and ‘the four hundred [i.e., many] priests [i.e., spirit helpers] who will carry the featherweight load’, the porter represented himself as having godlike abilities.Footnote 109 He said, ‘Here go the ones having blood, the ones having color [i.e., the other carriers, who are mere human beings]. But as for me, I do not have any blood, I do not have any color [i.e., I am supernatural]. I am indeed the one. I am indeed the priest; I am Quetzalcoatl. I am not just anybody.’Footnote 110 Such incantations exemplify how Nahuatl-speaking people of Guerrero may have used ‘word magic’ to conjure the strength, psychological fortitude, and communal integrity to carry out the daily expectations of their demanding repartimiento assignments.

If they fell sick, they may have used a spiritual cure developed by a chilapeño named Don Martín Sebastián y Cerón, who was ‘very respected among the natives as a sage’.Footnote 111 His remedy intended ‘to serve as a cure for many sicknesses’ and was thus a panacea that likely found its way down the slopes to Acapulco.Footnote 112 Its recipe was simple: twelve maize kernels in water mixed with an herb called atlinan (‘its mother is water’, rumex pulcher, fiddle dock).Footnote 113

Before casting the kernels into the water and mixing in the atlinan, Sebastián y Cerón said a few words, including, ‘Who is the god, who is the illustrious being that already is destroying my vassal [i.e., the patient]? Let him just quietly leave. Let him just quietly move aside for me … Indeed already it is over there that he is expected, at a place where people are prosperous, in a place of property owners.’Footnote 114 The healer thus entreated the illness – a divine entity – to move on to a place where the people could presumably stand to lose more than the patient. In this context, the ‘place of property owners’ could also be understood as where Spaniards or elites resided, since Indigenous commoners typically held land communally. It is possible that Indigenous labourers in Acapulco understood the sickness that debilitated the Spanish officials in 1615 in these terms and even thought of themselves as the agents of that plague.

Bodily fatigue, called quaquahtiliztli, was treated differently, and Ruiz de Alarcón learned the method from two women, Magdalena Petronilla Xochiquetzal and Justina. The cure began with a massage ‘from the kidneys and groin down to the heels’. Then, a poisonous seed called tzopilotl (‘a thing hung over filth’, swietenia humilis) was introduced into the rectum as an enema.Footnote 115 With the help of an incantation, it would produce an evacuation that eliminated stiffness and pain. If this was indeed a widely held practice in Guerrero, it must have seen frequent use during the repartimientos at Acapulco.

There is some evidence to suggest that the transient Indigenous labourers shared their spiritual knowledge with the port’s multi-ethnic Afro-Mexican and Asian residents who also toiled at the fort in their dozens. Logged in a series of inquisitorial denunciations against Afro-Mexican women diviners at the port is one account of an enslaved ‘mulata’ who used ololiuhqui (a morning glory seed) to gain spiritual knowledge. Her name was Madalena, and she was married to a “chino” (Asian) named Pedro Elen, a drummer in the garrison of the Fort of San Diego. During the late 1620s, her enslaver, Ana Muñoz, demanded that she take ololiuhqui to divine the location of the Manila galleons.Footnote 116

Ololiuhqui was a hallucinogen commonly consumed among Indigenous people to the north-west and north of Acapulco. Of particular note, Ruiz de Alarcón commented that the veneration of ololiuhqui was often mixed with Catholic iconography and that the seed had been found as an offering left in pots at a cross in Chilapa and elsewhere in the region.Footnote 117 The inquisitorial report suggests that Madalena, her husband, and her enslaver participated in a community familiar with the ritual specificity of ololiuhqui consumption. Ololiuhqui had to be cultivated, cleaned, and prepared by knowledgeable specialists in order to enable its spiritual power, and Madalena performed these rituals to commune with an ‘old indio’ spirit who answered her questions. Madalena was one of the first of many Black women to learn about and use ololiuhqui during the colonial period.Footnote 118 The arrival of Indigenous spiritual experts through the repartimiento from the lands that most worshipped ololiuhqui undoubtedly played a foundational role in this channel of knowledge transmission. As such, the Fort of San Diego was a central site in the early history of Afro-Asian-Indigenous social and cultural interactions in the Americas.Footnote 119

Conclusion

By way of conclusion, an anecdote: the archbishop of Mexico, Juan Pérez de la Serna, visited the near-complete Fort of San Diego on 31 January 1617, to tell ‘the truth of all that I will see’ and to determine if the enormous financial investment in the fort (113,400 ducados) had paid off.Footnote 120 After his visit, Serna excitedly redacted a letter to the viceroy that same day. He described the construction as ‘seeming like a thing of miracle that with human strength alone it has not been possible to make such a great thing in such a short time’.Footnote 121

While Serna described the fort’s completion as ‘a thing of miracle’, Acapulco’s treasury records have told quite a different story. More than God’s favour, the fort’s construction was a product of fear – fear of eclipsing influence in the Pacific in the face of Dutch maritime power. It also depended entirely on Indigenous people from the hinterlands of Guerrero. In the thousands, they arrived at Acapulco under the brutal mandate of the repartimiento. Despite the casualties, they made choices to protect themselves, collect small gains from their labour, and share spiritual insights with the port’s inhabitants.

The fort’s ‘completion’ on 15 April 1617, obscured the dark legacy of its rushed construction that would rear its head again and again whenever the fort required repairs and never more than during the years of the padrastro repairs, 1632–35. Indeed, the environment was ever the bane of the structure. In 1766, an earthquake accomplished what no foreign navy ever could. It levelled the venerable Fort of San Diego and most of the port as well. Just over a decade later, the still-standing Castillo of San Carlos would rise over the ashes of its stone ancestor.Footnote 122

During the Fort of San Diego’s 150-year existence, an engraving with a globe and the royal coat of arms stood watch above the main gate. Below that, a plaque read, ‘Reigning in the Spains and East and West Indies, the majesty of the supremely unconquered and Catholic king don Felipe our lord, third of his name, being his viceroy, substitute, and captain general in the kingdoms of New Spain, don Diego Fernández de Córdoba, marqués of Guadalcázar, this fortification was made by the engineer Adrian Boot in 1616.’Footnote 123 Unsurprisingly, the date of completion was incorrect, and there is no mention of the Indigenous labourers that delivered Felipe III the defence of the global trade to which his coat of arms could lay claim. They were global actors, just as much as the mounted European in Figure 3 whose gaze across the ocean bound together distant colonies. There was no Spanish Pacific without them and the thousands of others along Mexico’s Pacific coasts and in the mountains, who had suddenly become deeply enmeshed in the violent novelty of transpacific empire.

Figure 3. A man on horseback – presumably Adrian Boot – gazes down at the port and across the Pacific Ocean. The completed Fort of San Diego sits atop the headland just to the left of the town. In the foreground, two men cut wood. Adrian Boot, Puerto de Acapulco en el Reino de Nueva España en el Mar del Sur (Litog. Ruffoni, 1628). Reproduction courtesy of the Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

Acknowledgments

I am especially thankful to Heather Curtis and the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University (CHAT) where I held a fellowship that afforded me the time needed to write this piece. Furthermore, I am indebted to the Johns Hopkins Department of History’s Monday Seminar, where I shared an early draft of this article. Much of the article’s methodological framing emerged in conversation with my colleagues at the Seminar. I am also thankful for the anonymous reviewers’ commentary and for the support of the Journal of Global History Editorial Board.

Financial support

Research for this article was funded by Tufts University, the Huntington Library, and the American Historical Association.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Diego Javier Luis is the Rohrbaugh Family Assistant Professor at Johns Hopkins University. He is the author of The First Asians in the Americas: A Transpacific History (2024), and he researches the histories at the intersection of the Spanish Pacific and colonial Latin America.