This paper considers the “risk-weighted expected utility” (

![]() $REU$

) introduced by Lara Buchak (Reference Buchak2013) (formally identical to the “anticipated utility” introduced by John Quiggin (Reference Quiggin1982), but with a normative rather than a descriptive interpretation), which is based on a risk function

$REU$

) introduced by Lara Buchak (Reference Buchak2013) (formally identical to the “anticipated utility” introduced by John Quiggin (Reference Quiggin1982), but with a normative rather than a descriptive interpretation), which is based on a risk function

![]() $R$

that is required to be a continuous, strictly increasing function from the unit interval

$R$

that is required to be a continuous, strictly increasing function from the unit interval

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

to itself. Buchak motivates her generalization of risk-neutral expected utility (

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

to itself. Buchak motivates her generalization of risk-neutral expected utility (

![]() $EU$

) by arguing that means-ends reasoning requires an improvement in any possible outcome of a gamble to contribute positively to its evaluation, but not necessarily in direct proportion to its probability. On her framework, this corresponds to the requirement that

$EU$

) by arguing that means-ends reasoning requires an improvement in any possible outcome of a gamble to contribute positively to its evaluation, but not necessarily in direct proportion to its probability. On her framework, this corresponds to the requirement that

![]() $R$

be strictly increasing.

$R$

be strictly increasing.

Buchak notes (Reference Buchak2013: 68–70) that maximin and maximax preferences could be said to be particularly extreme forms of risk sensitivity that can be accommodated in a generalization of this approach by relaxing the requirement that

![]() $R$

be continuous and strictly increasing. But she notes that this involves giving up her means-ends understanding of decision theory. Thus, rather than relaxing strict monotonicity, I relax the requirement that the range of this function be the unit interval. I show that when the interval is infinite, the resulting decision rule still has the maximin or maximax property of prioritizing the best or worst outcome over all others. I observe that the resulting rule is interestingly different in other ways, but satisfies more of the axioms of her representation theorem than the classic maximin and maximax rules, as well as others I call “leximin” and “leximax”.

$R$

be continuous and strictly increasing. But she notes that this involves giving up her means-ends understanding of decision theory. Thus, rather than relaxing strict monotonicity, I relax the requirement that the range of this function be the unit interval. I show that when the interval is infinite, the resulting decision rule still has the maximin or maximax property of prioritizing the best or worst outcome over all others. I observe that the resulting rule is interestingly different in other ways, but satisfies more of the axioms of her representation theorem than the classic maximin and maximax rules, as well as others I call “leximin” and “leximax”.

An important running theme throughout involves the relationship between Buchak’s risk-weighting function

![]() $R$

, and the marginal risk-weighted contributions of individual outcomes, which I will notate with “

$R$

, and the marginal risk-weighted contributions of individual outcomes, which I will notate with “

![]() $r$

”. I show that in many contexts it is simpler and more natural to calculate by means of

$r$

”. I show that in many contexts it is simpler and more natural to calculate by means of

![]() $r$

than by

$r$

than by

![]() $R$

. I argue that

$R$

. I argue that

![]() $r$

does a better job of representing Buchak’s means-ends philosophical motivations. This is especially clear in the broadest generalization I reach at the end, which is the condition that

$r$

does a better job of representing Buchak’s means-ends philosophical motivations. This is especially clear in the broadest generalization I reach at the end, which is the condition that

![]() $r$

be a measurable, real-valued function with at most finitely many singularities, that is everywhere non-negative, and for which there is no interval over which it is almost always 0. I claim that this condition on

$r$

be a measurable, real-valued function with at most finitely many singularities, that is everywhere non-negative, and for which there is no interval over which it is almost always 0. I claim that this condition on

![]() $r$

properly represents Buchak’s means-ends motivation, but when phrased in terms of

$r$

properly represents Buchak’s means-ends motivation, but when phrased in terms of

![]() $R$

requires that it be locally strictly increasing with finitely many singularities.

$R$

requires that it be locally strictly increasing with finitely many singularities.

In section 1, I formally define finite gambles, as well as the “cumulative” parameters

![]() $U$

and

$U$

and

![]() $P$

, and the “marginal” or “incremental” parameters

$P$

, and the “marginal” or “incremental” parameters

![]() $u$

and

$u$

and

![]() $p$

. In section 2 I review the standard definition of expected utility (

$p$

. In section 2 I review the standard definition of expected utility (

![]() $EU$

), and show how to calculate it with vertical rectangles using

$EU$

), and show how to calculate it with vertical rectangles using

![]() $U$

and

$U$

and

![]() $p$

, or horizontal rectangles using

$p$

, or horizontal rectangles using

![]() $u$

and

$u$

and

![]() $P$

. In section 3, I review Buchak’s definition of risk-weighted expected utility (

$P$

. In section 3, I review Buchak’s definition of risk-weighted expected utility (

![]() $REU$

), using a risk-weighting function

$REU$

), using a risk-weighting function

![]() $R$

that is continuous, strictly increasing, and sends the

$R$

that is continuous, strictly increasing, and sends the

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval of probabilities to the

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval of probabilities to the

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval of decision weights. I include both the definition of

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval of decision weights. I include both the definition of

![]() $REU$

she emphasizes using horizontal rectangles with

$REU$

she emphasizes using horizontal rectangles with

![]() $u$

and

$u$

and

![]() $R$

, and an equivalent definition using vertical rectangles with

$R$

, and an equivalent definition using vertical rectangles with

![]() $U$

and

$U$

and

![]() $r$

. In section 4 I show that her use of the interval

$r$

. In section 4 I show that her use of the interval

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

for decision weights is an inessential convention. In section 5, I show that relaxing to other finite intervals yields a pleasing symmetry in that both utility and decision weight end up being unique only up to affine transformation. In section 6 I introduce the most significant generalization of Buchak’s risk-weighted utility, by allowing

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

for decision weights is an inessential convention. In section 5, I show that relaxing to other finite intervals yields a pleasing symmetry in that both utility and decision weight end up being unique only up to affine transformation. In section 6 I introduce the most significant generalization of Buchak’s risk-weighted utility, by allowing

![]() $R$

to send the

$R$

to send the

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval to infinite intervals, and allowing

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval to infinite intervals, and allowing

![]() $r$

to give infinite decision weight to one or more positions in the scale (such as the maximum, minimum, or even median). In section 7, I compare the motivation for this generalization to the motivations for two other types of decision rule that are sometimes said to be infinitely extreme versions of risk-sensitivity, namely “classic maximin” (and maximax) and a less-familiar “leximin” (and leximax). But I argue that my generalization does a better job of preserving Buchak’s motivation for risk-sensitive decision theory as a general kind of means-ends rationality.

$r$

to give infinite decision weight to one or more positions in the scale (such as the maximum, minimum, or even median). In section 7, I compare the motivation for this generalization to the motivations for two other types of decision rule that are sometimes said to be infinitely extreme versions of risk-sensitivity, namely “classic maximin” (and maximax) and a less-familiar “leximin” (and leximax). But I argue that my generalization does a better job of preserving Buchak’s motivation for risk-sensitive decision theory as a general kind of means-ends rationality.

I also include two appendices. In Appendix 1, I show how the informal motivations I give for my extended decision rule correspond to modifications of the axiomatic structure of Buchak’s representation theorem. My extended decision rule satisfies all but two of her axioms, while leximin and classic maximin each violate some additional axioms. In Appendix 2, I develop the entire apparatus for continuous gambles as well as for finite ones. This appendix mostly follows the same structure as sections 1–6 of the main body of the paper. However, Appendix 2.2 develops more precisely a proposal of Colyvan (Reference Colyvan2008) to define decision theory in terms of comparisons of pairs of gambles, rather than by providing a numerical evaluation of each gamble individually. This is essential even for standard

![]() $EU$

because of cases Colyvan cites (due to Nover and Hájek Reference Nover and Hájek2004), in which there are contributions from unboundedly positive or negative utility, but it becomes more pressing when the decision weights can become infinite as well. A few aspects of this comparative proposal, and of the advantages of working with

$EU$

because of cases Colyvan cites (due to Nover and Hájek Reference Nover and Hájek2004), in which there are contributions from unboundedly positive or negative utility, but it becomes more pressing when the decision weights can become infinite as well. A few aspects of this comparative proposal, and of the advantages of working with

![]() $r$

over

$r$

over

![]() $R$

, are clearer in the continuous case than the finite case. All footnotes in the main text are references to relevant points in this appendix. Even for readers who are sceptical of the value of decision rules that put infinite weight at some points in the scale, the motivations it gives for the comparative formulation of risk-weighted expected utility (for continuous gambles), and the formulation in terms of

$R$

, are clearer in the continuous case than the finite case. All footnotes in the main text are references to relevant points in this appendix. Even for readers who are sceptical of the value of decision rules that put infinite weight at some points in the scale, the motivations it gives for the comparative formulation of risk-weighted expected utility (for continuous gambles), and the formulation in terms of

![]() $r$

rather than

$r$

rather than

![]() $R$

(both for finite and continuous gambles), should be of value.

$R$

(both for finite and continuous gambles), should be of value.

1. Finite Gambles

Represent a finite gamble

![]() $G$

as a finite set of pairs

$G$

as a finite set of pairs

![]() $G = \left\{ { \ldots, \left( {{U_i},{p_i}} \right), \ldots } \right\}$

, where each pair represents the utility and probability of one possible outcome of the gamble. (I assume that the

$G = \left\{ { \ldots, \left( {{U_i},{p_i}} \right), \ldots } \right\}$

, where each pair represents the utility and probability of one possible outcome of the gamble. (I assume that the

![]() ${U_i}$

and

${U_i}$

and

![]() ${p_i}$

are real numbers, and that the

${p_i}$

are real numbers, and that the

![]() ${p_i}$

are strictly positive, with

${p_i}$

are strictly positive, with

![]() $\sum\, {p_i} = 1$

.) It will be helpful to adopt a convention whereby the values

$\sum\, {p_i} = 1$

.) It will be helpful to adopt a convention whereby the values

![]() $i$

range from 0 to

$i$

range from 0 to

![]() $n$

, and where

$n$

, and where

![]() ${U_{i + 1}} \lt {U_i}$

. (This can always be arranged by merging outcomes with the same utility, and then re-numbering the remaining outcomes from highest to lowest.)

${U_{i + 1}} \lt {U_i}$

. (This can always be arranged by merging outcomes with the same utility, and then re-numbering the remaining outcomes from highest to lowest.)

It will also be helpful to define the gamble by another set of ordered pairs. Let

![]() ${P_i} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 0}^i {p_j}$

be the total probability of the

${P_i} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 0}^i {p_j}$

be the total probability of the

![]() $i + 1$

outcomes with greatest utility. Then

$i + 1$

outcomes with greatest utility. Then

![]() ${p_i} = {P_i} - {P_{i - 1}}$

, with the special convention that

${p_i} = {P_i} - {P_{i - 1}}$

, with the special convention that

![]() ${P_{ - 1}} = 0$

. Similarly, define

${P_{ - 1}} = 0$

. Similarly, define

![]() ${u_i} = {U_i} - {U_{i + 1}}$

, with the special convention that

${u_i} = {U_i} - {U_{i + 1}}$

, with the special convention that

![]() ${U_{n + 1}} = 0$

. Then, for

${U_{n + 1}} = 0$

. Then, for

![]() $0 \le i \lt j \le n$

,

$0 \le i \lt j \le n$

,

![]() ${P_i} \lt {P_j}$

and

${P_i} \lt {P_j}$

and

![]() ${U_i} \gt {U_j}$

(though this generally fails if

${U_i} \gt {U_j}$

(though this generally fails if

![]() $i = - 1$

or

$i = - 1$

or

![]() $j = n + 1$

). I say that lower case

$j = n + 1$

). I say that lower case

![]() ${p_i}$

and

${p_i}$

and

![]() ${u_i}$

represent the marginal (incremental) probability or utility of the

${u_i}$

represent the marginal (incremental) probability or utility of the

![]() $i$

th best outcome, while capital

$i$

th best outcome, while capital

![]() ${P_i}$

and

${P_i}$

and

![]() ${U_i}$

represent the cumulative (total) probability down to or utility up to that outcome.

${U_i}$

represent the cumulative (total) probability down to or utility up to that outcome.

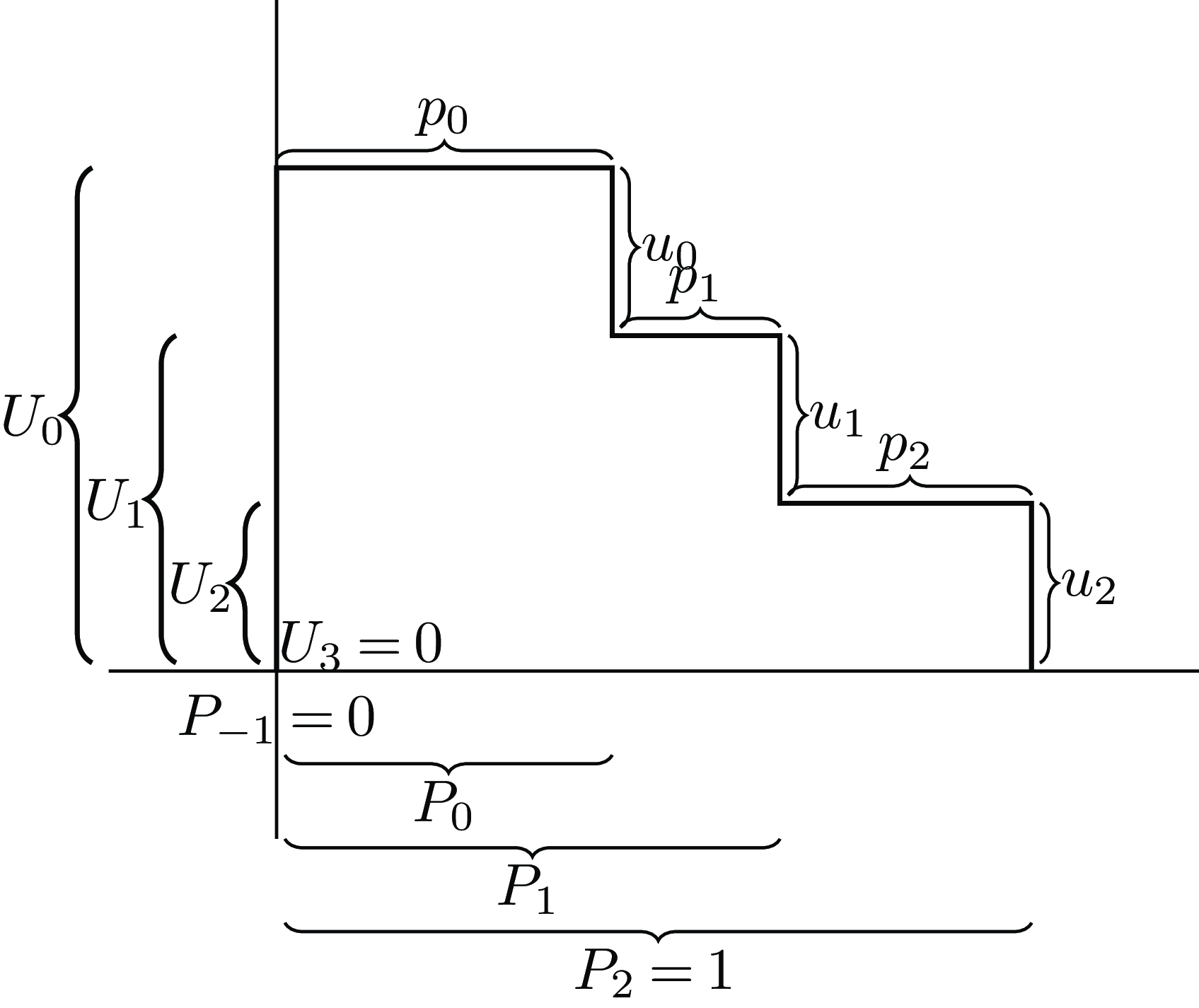

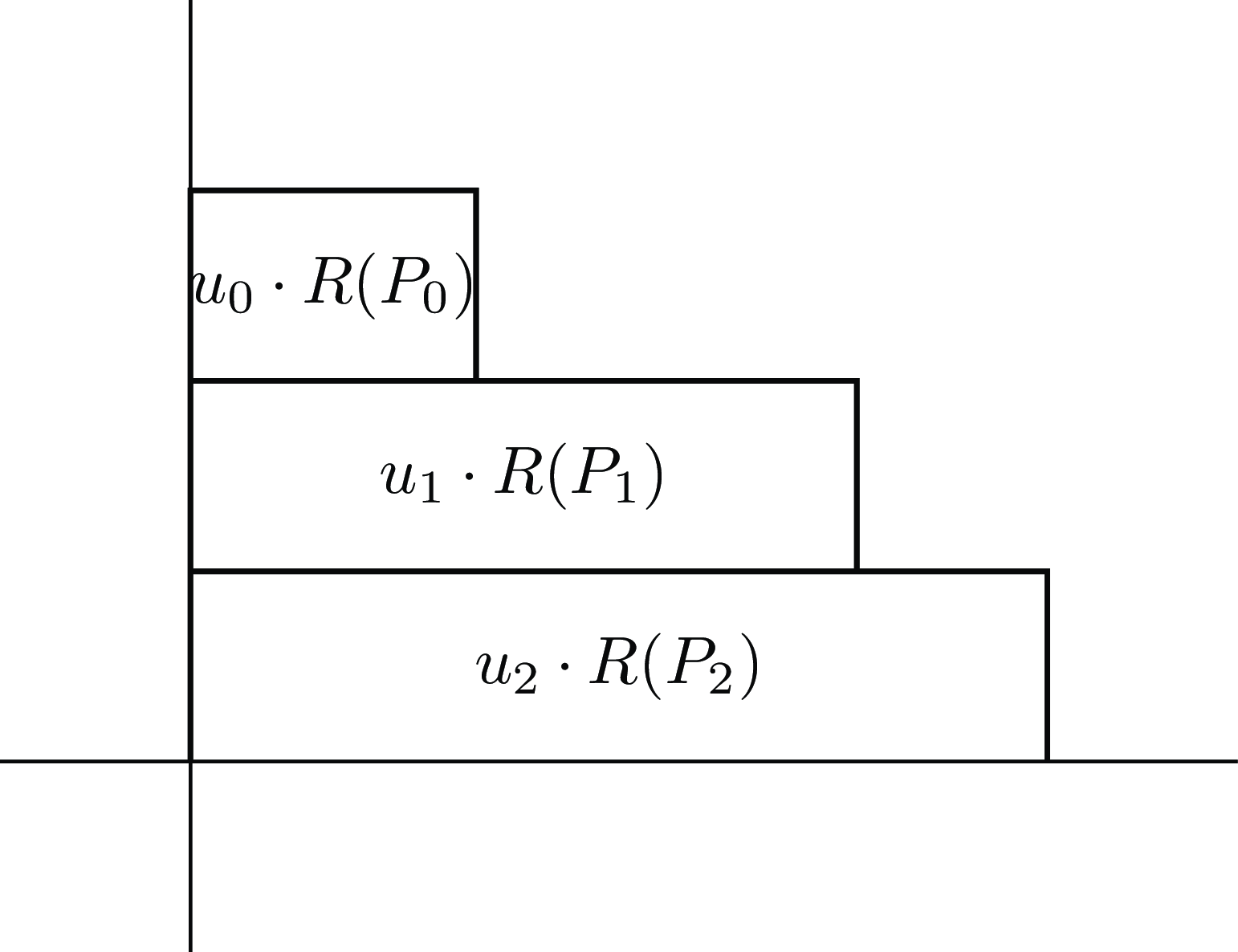

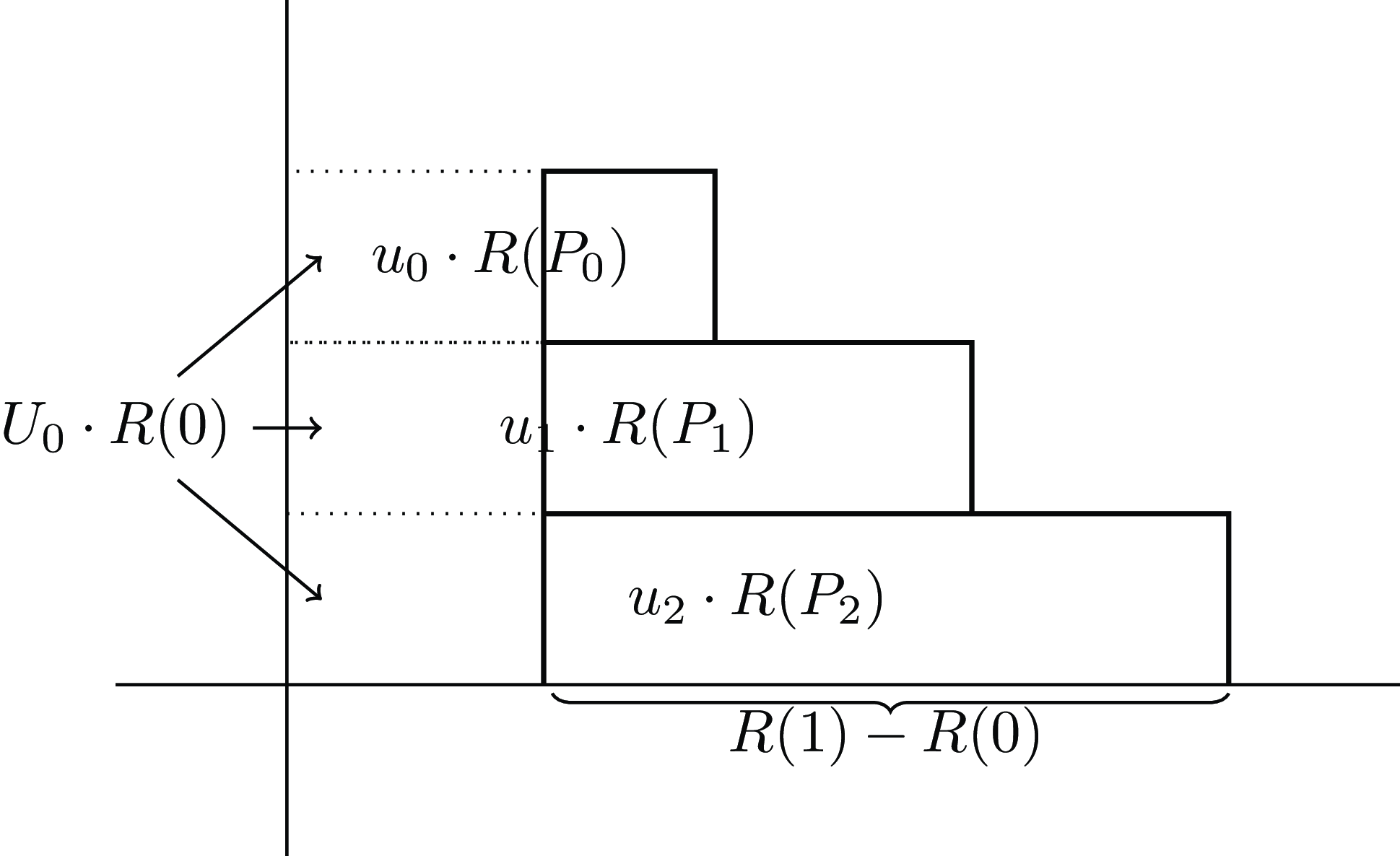

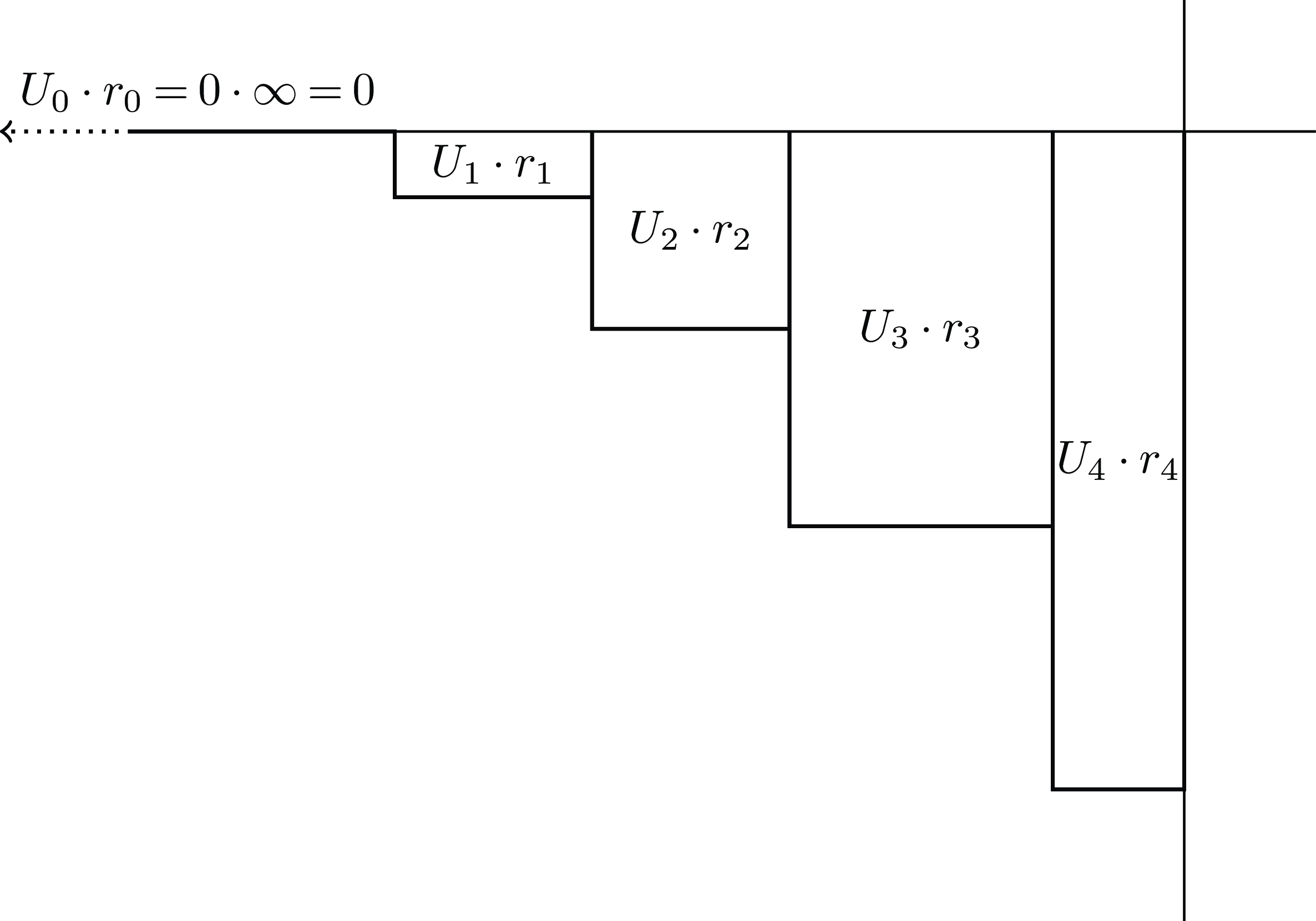

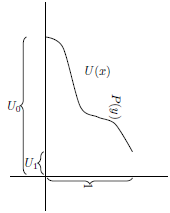

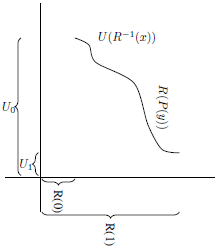

Figure 1 illustrates a simple case where

![]() $n = 2$

and all the

$n = 2$

and all the

![]() ${U_i}$

are positive.

${U_i}$

are positive.

Figure 1. Illustration of the cumulative and marginal utilities

![]() ${U_i}$

and

${U_i}$

and

![]() ${u_i}$

, and the cumulative and marginal probabilities

${u_i}$

, and the cumulative and marginal probabilities

![]() ${P_i}$

and

${P_i}$

and

![]() ${p_i}$

.

${p_i}$

.

2. Standard Expected Utility: Vertical or Horizontal Rectangles

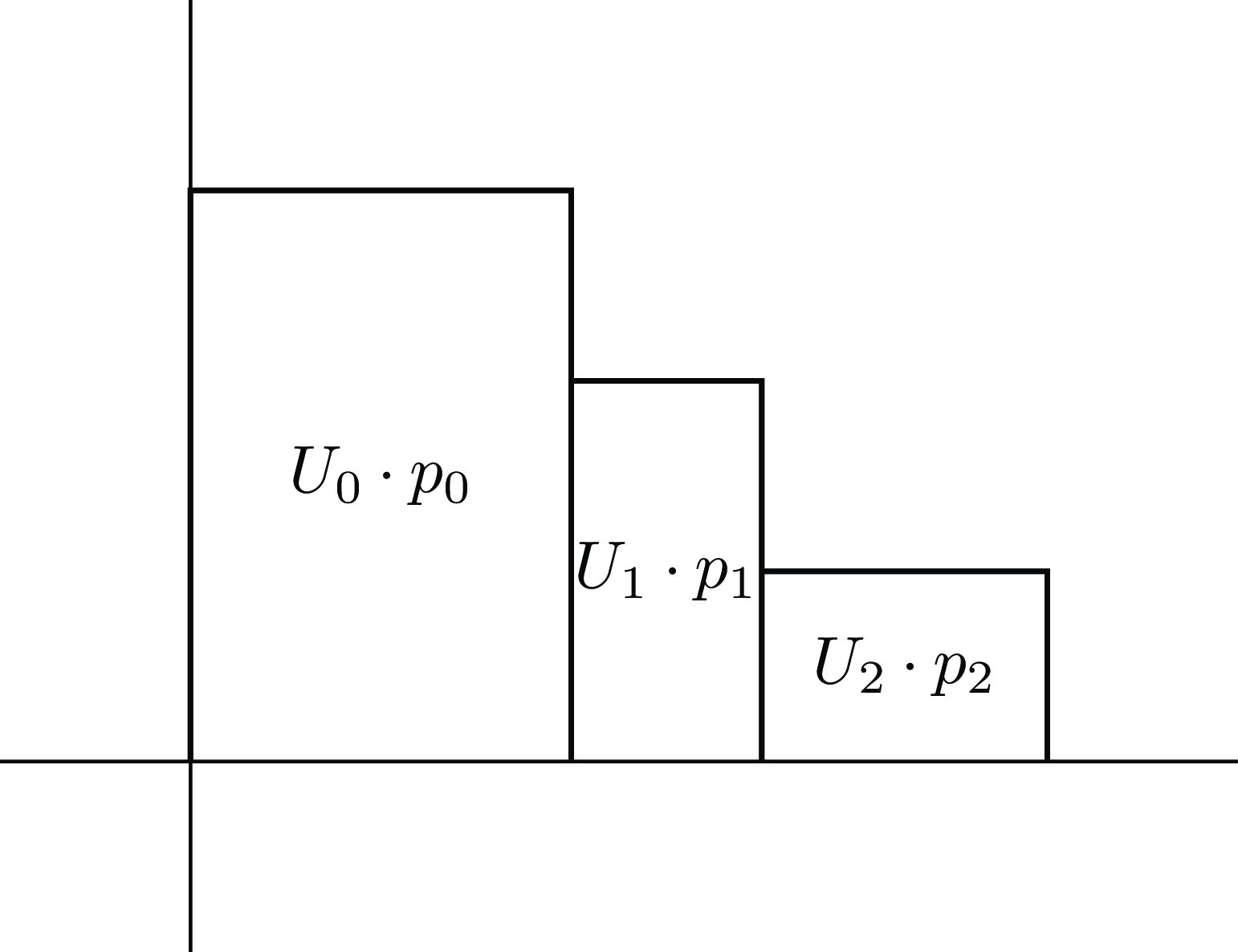

Standard expected utility theory defines the expected utility of a gamble by

![]() $EU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n \,{U_i} \cdot {p_i}$

and says that

$EU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n \,{U_i} \cdot {p_i}$

and says that

![]() ${G_1}$

should be preferred to

${G_1}$

should be preferred to

![]() ${G_2}$

iff

${G_2}$

iff

![]() $EU\left( {{G_1}} \right) \gt EU\left( {{G_2}} \right)$

. This standard formula can be visualized as taking the area under the utility-probability steps as seen in Figure 2.

$EU\left( {{G_1}} \right) \gt EU\left( {{G_2}} \right)$

. This standard formula can be visualized as taking the area under the utility-probability steps as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Expected utility calculated with vertical rectangles.

Because the

![]() ${p_i}$

are non-negative, increasing the utility of one or more outcomes without changing that of any others increases

${p_i}$

are non-negative, increasing the utility of one or more outcomes without changing that of any others increases

![]() $EU$

. This can be generalized. We say that one gamble stochastically dominates another iff for every utility value, the probability that the first has a utility at least that high is at least as great as for the second. If one finite gamble stochastically dominates another, then the dominated one can be transformed into the dominating one by first splitting some outcomes into multiple outcomes of the same utility (to ensure that the sequence of outcomes of the two gambles has the same sequence of

$EU$

. This can be generalized. We say that one gamble stochastically dominates another iff for every utility value, the probability that the first has a utility at least that high is at least as great as for the second. If one finite gamble stochastically dominates another, then the dominated one can be transformed into the dominating one by first splitting some outcomes into multiple outcomes of the same utility (to ensure that the sequence of outcomes of the two gambles has the same sequence of

![]() ${p_i}$

, without changing

${p_i}$

, without changing

![]() $EU$

) and then increasing the utility of some outcomes without changing that of any others. Thus, if one gamble stochastically dominates another, it has a higher

$EU$

) and then increasing the utility of some outcomes without changing that of any others. Thus, if one gamble stochastically dominates another, it has a higher

![]() $EU$

, and is thus preferred.

$EU$

, and is thus preferred.

Buchak notes that this corresponds to the idea of decision theory as a codification of means-ends reasoning. Any motivation for preferring one gamble over another must be based in some possibility of receiving a better outcome, and any possibility of receiving a better outcome provides a decisive reason to prefer that outcome, unless there is also some possibility of receiving a worse outcome (in which case some way of measuring the tradeoff is needed). Tarsney (Reference Tarsney2020) argues that stochastic dominance might be the only property shared by all reasonable decision theories, but as we will see later, Buchak focuses on the way some better outcomes are traded off against some worse outcomes in particular decision theories.

Because

![]() ${P_n} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n {p_i} = 1$

, the area under this step function is somewhere between that of a rectangle with width 1 and height

${P_n} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n {p_i} = 1$

, the area under this step function is somewhere between that of a rectangle with width 1 and height

![]() ${U_n}$

and a rectangle with width 1 and height

${U_n}$

and a rectangle with width 1 and height

![]() ${U_0}$

. That is, the standard

${U_0}$

. That is, the standard

![]() $EU$

of a gamble is somewhere between the minimum and maximum utilities that the gamble can achieve, i.e.

$EU$

of a gamble is somewhere between the minimum and maximum utilities that the gamble can achieve, i.e.

![]() ${U_n} \le EU\left( G \right) \le {U_0}$

. Thus, we can think of

${U_n} \le EU\left( G \right) \le {U_0}$

. Thus, we can think of

![]() $EU\left( G \right)$

as in some sense an estimate of the outcome of gamble

$EU\left( G \right)$

as in some sense an estimate of the outcome of gamble

![]() $G$

. I claim that this is a formal convenience, which is useful for some applications of

$G$

. I claim that this is a formal convenience, which is useful for some applications of

![]() $EU$

, but is not essential to a way of comparing gambles the way that agreement with stochastic dominance is.

$EU$

, but is not essential to a way of comparing gambles the way that agreement with stochastic dominance is.

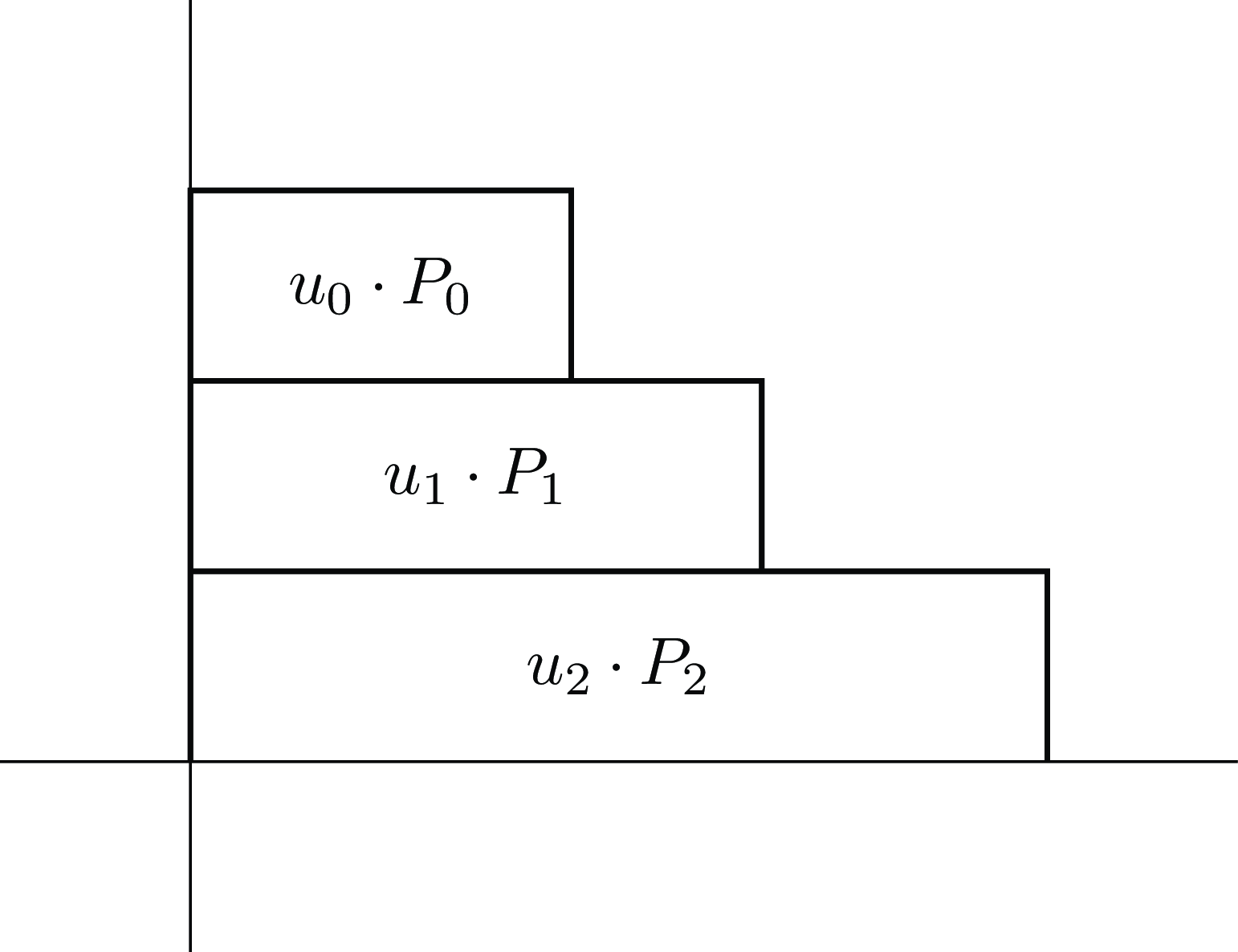

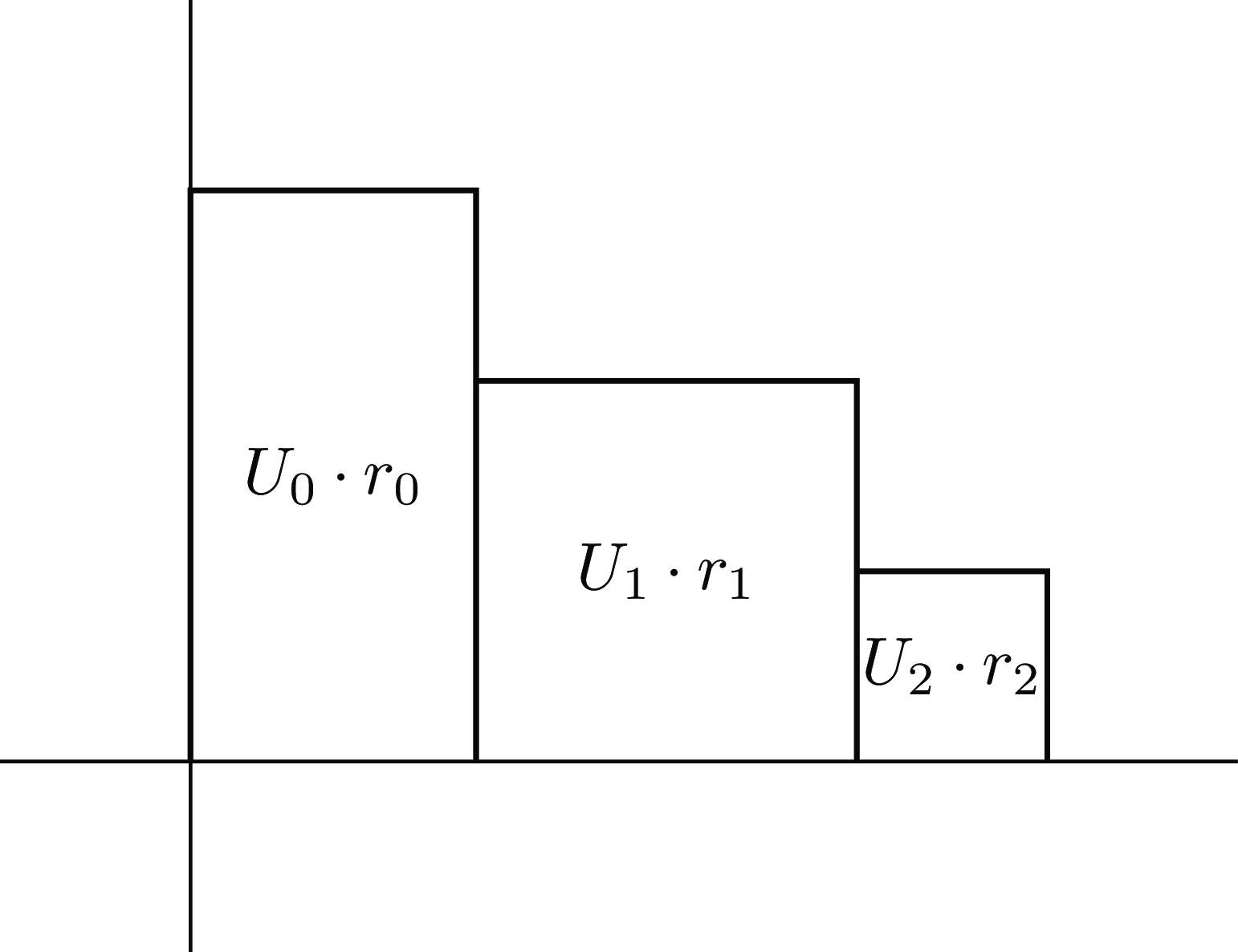

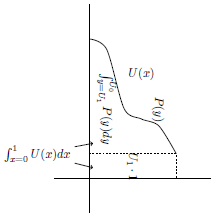

This way of calculating the area uses the marginal probabilities and the cumulative utilities. However, we can equally define

![]() $EU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n {u_i} \cdot {P_i}$

, using marginal utilities and cumulative probabilities. The two definitions correspond to measuring the same area under the utility-probability steps, but breaking the area into horizontal rectangles instead of vertical ones, as seen in Figure 3. This summation of horizontal rectangles rather than vertical ones gives another way to see that

$EU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n {u_i} \cdot {P_i}$

, using marginal utilities and cumulative probabilities. The two definitions correspond to measuring the same area under the utility-probability steps, but breaking the area into horizontal rectangles instead of vertical ones, as seen in Figure 3. This summation of horizontal rectangles rather than vertical ones gives another way to see that

![]() $EU$

is compatible with stochastic dominance. It is conceptually less familiar than the summation of vertical rectangles, but is helpful in giving a presentation of Buchak’s risk-weighted expected utility.

$EU$

is compatible with stochastic dominance. It is conceptually less familiar than the summation of vertical rectangles, but is helpful in giving a presentation of Buchak’s risk-weighted expected utility.

Figure 3. Expected utility calculated with horizontal rectangles.

3. Risk-weighted Expected Utility: Horizontal or Vertical Rectangles

Risk-weighted expected utility adds a further consideration – a risk-sensitivity function

![]() $R:\left[ {0,1\left] \to \right[0,1} \right]$

with the requirements that

$R:\left[ {0,1\left] \to \right[0,1} \right]$

with the requirements that

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = 0$

,

$R\left( 0 \right) = 0$

,

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = 1$

, and

$R\left( 1 \right) = 1$

, and

![]() $R$

is continuous and strictly increasing, i.e.

$R$

is continuous and strictly increasing, i.e.

![]() $R\left( x \right) \lt R\left( y \right)$

whenever

$R\left( x \right) \lt R\left( y \right)$

whenever

![]() $x \lt y$

. This function is used to “stretch” the importance of various outcomes based on their cumulative probability. That is, we don’t take the cumulative probability

$x \lt y$

. This function is used to “stretch” the importance of various outcomes based on their cumulative probability. That is, we don’t take the cumulative probability

![]() ${P_i}$

itself to measure how much the

${P_i}$

itself to measure how much the

![]() $i$

th marginal utility contributes to the evaluation of a gamble, but instead use

$i$

th marginal utility contributes to the evaluation of a gamble, but instead use

![]() $R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

. Standard

$R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

. Standard

![]() $EU$

assumes that the importance of an outcome is directly proportional to its probability, but under risk-weighting, this is adjusted by the function

$EU$

assumes that the importance of an outcome is directly proportional to its probability, but under risk-weighting, this is adjusted by the function

![]() $R$

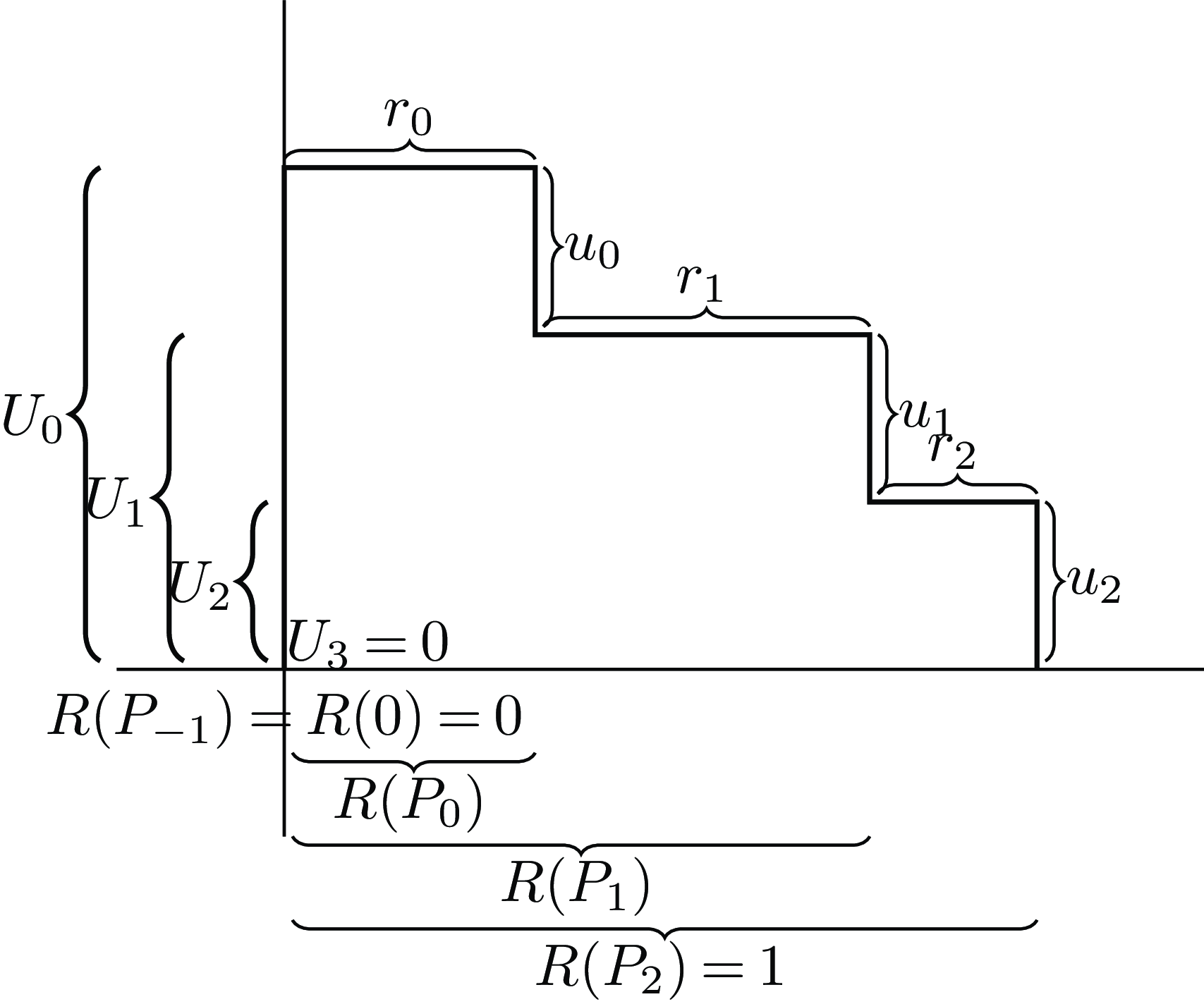

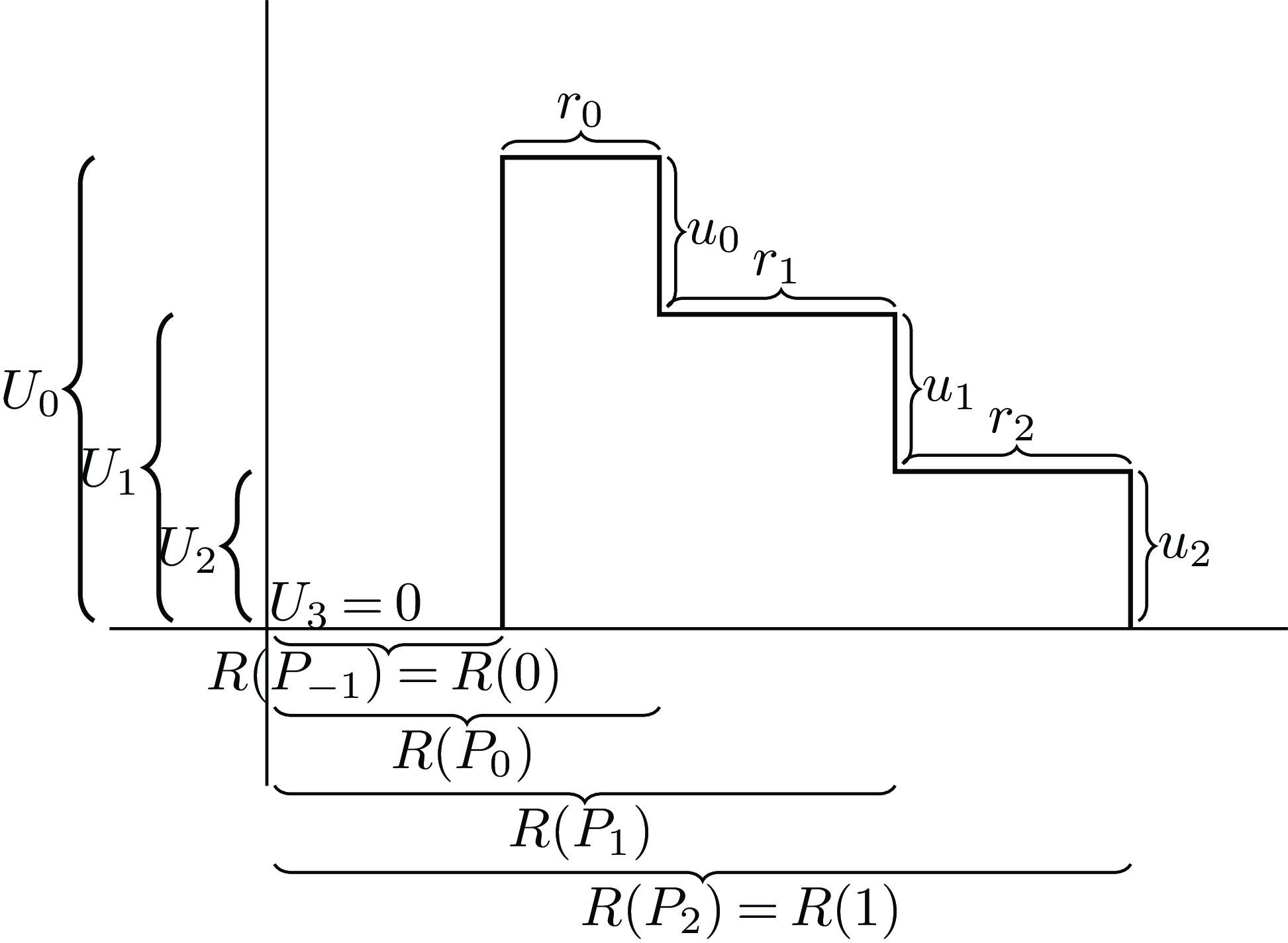

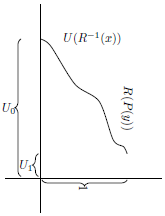

. Buchak motivates this adjustment by arguing that the concept of means-ends rationality doesn’t require direct proportionality, but just requires the idea that all possible outcomes contribute positively. Figure 4 graphs utility against risk-sensitivity, instead of probability.

$R$

. Buchak motivates this adjustment by arguing that the concept of means-ends rationality doesn’t require direct proportionality, but just requires the idea that all possible outcomes contribute positively. Figure 4 graphs utility against risk-sensitivity, instead of probability.

Figure 4. Illustration of the cumulative and marginal risk-weightings

![]() $R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

and

$R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

and

![]() ${r_i}$

, along with

${r_i}$

, along with

![]() ${U_i}$

and

${U_i}$

and

![]() ${u_i}$

.

${u_i}$

.

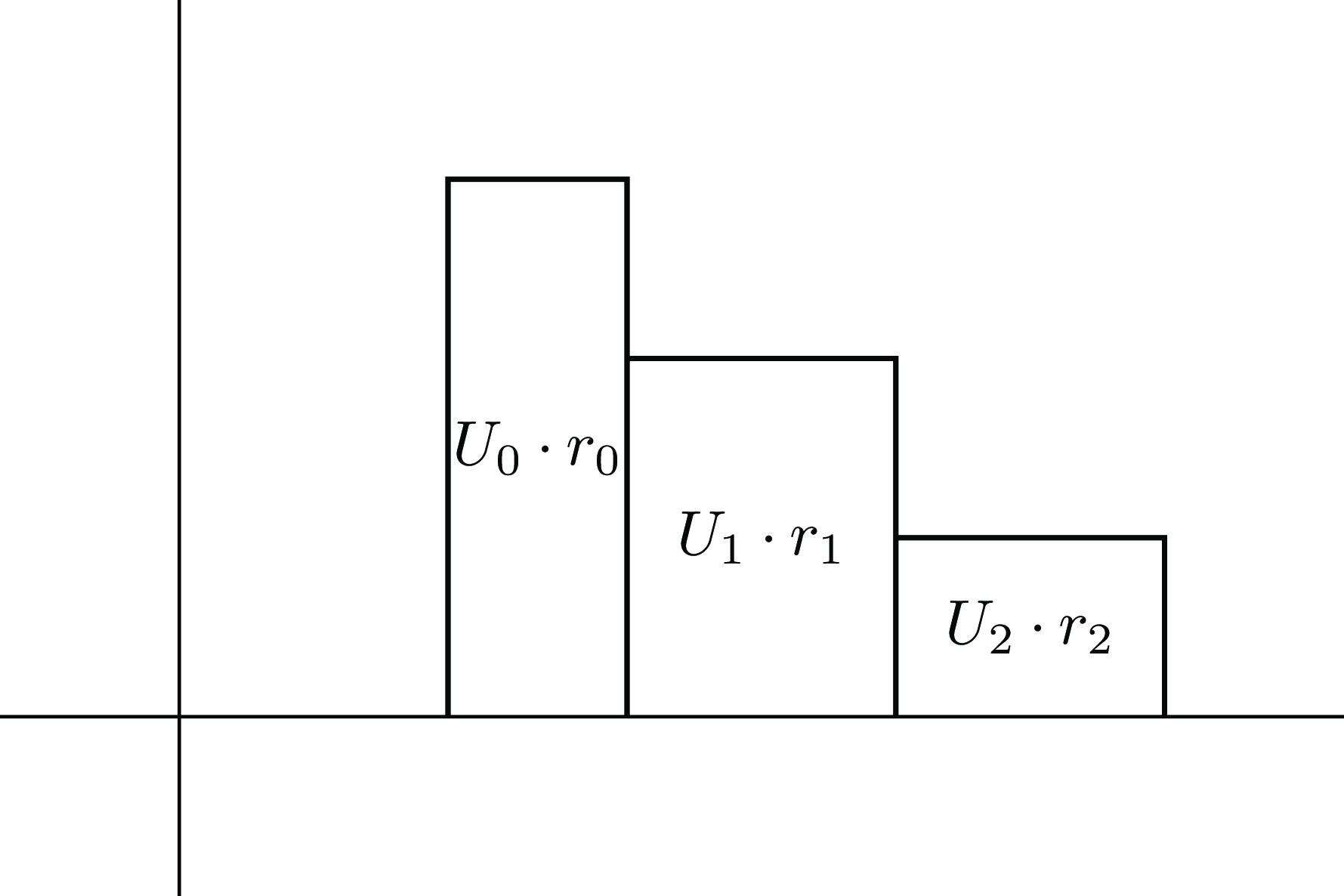

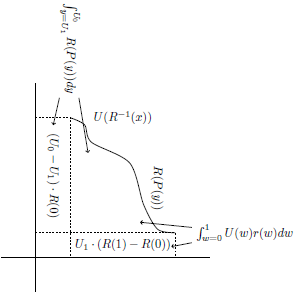

The simplest definition of risk-weighted utility parallels the “horizontal” definition of standard

![]() $EU$

, using the risk-weightings instead of the probabilities, as illustrated in Figure 5.

$EU$

, using the risk-weightings instead of the probabilities, as illustrated in Figure 5.

![]() $REU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_G {u_i} \cdot R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

. But just as we had marginal and cumulative utility, and marginal and cumulative probability, we can call

$REU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_G {u_i} \cdot R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

. But just as we had marginal and cumulative utility, and marginal and cumulative probability, we can call

![]() $R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

the cumulative risk-weighting, and define

$R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

the cumulative risk-weighting, and define

![]() ${r_i} = R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{i - 1}}} \right)$

(again with the convention that

${r_i} = R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{i - 1}}} \right)$

(again with the convention that

![]() ${P_{ - 1}} = 0$

) as the marginal risk weighting. Using the marginal risk-weightings instead of the marginal probabilities, we see that the sum

${P_{ - 1}} = 0$

) as the marginal risk weighting. Using the marginal risk-weightings instead of the marginal probabilities, we see that the sum

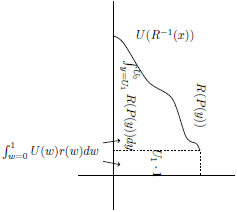

![]() $REU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_G {U_i} \cdot {r_i}$

calculates this “vertically”, as in Figure 6.

$REU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_G {U_i} \cdot {r_i}$

calculates this “vertically”, as in Figure 6.

Figure 5. Risk-weighted expected utility calculated with horizontal rectangles.

Figure 6. Risk-weighted expected utility calculated with vertical rectangles.

Although the

![]() ${r_i}$

are more complicated to define directly in terms of the ordered pairs that make up the gamble, they make certain features of

${r_i}$

are more complicated to define directly in terms of the ordered pairs that make up the gamble, they make certain features of

![]() $REU$

easier to understand. To the extent that the vertical calculation is more familiar in the case of

$REU$

easier to understand. To the extent that the vertical calculation is more familiar in the case of

![]() $EU$

, the version of

$EU$

, the version of

![]() $REU$

defined in terms of the

$REU$

defined in terms of the

![]() ${r_i}$

may be more intuitively meaningful than the version defined in terms of the

${r_i}$

may be more intuitively meaningful than the version defined in terms of the

![]() $R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

. Furthermore, the requirement that

$R\left( {{P_i}} \right)$

. Furthermore, the requirement that

![]() $R\left( x \right) \lt R\left( y \right)$

whenever

$R\left( x \right) \lt R\left( y \right)$

whenever

![]() $x \lt y$

corresponds to the requirement that each

$x \lt y$

corresponds to the requirement that each

![]() ${r_i}$

is strictly positive. This means that every term in this vertical sum contributes with positive weight. This again ensures agreement with stochastic dominance, and Buchak’s means-ends motivation. (If some

${r_i}$

is strictly positive. This means that every term in this vertical sum contributes with positive weight. This again ensures agreement with stochastic dominance, and Buchak’s means-ends motivation. (If some

![]() ${r_i}$

were zero or negative, then two gambles with the same probabilities, and same utilities for every outcome other than

${r_i}$

were zero or negative, then two gambles with the same probabilities, and same utilities for every outcome other than

![]() ${U_i}$

, would not be strictly ranked in the order of these

${U_i}$

, would not be strictly ranked in the order of these

![]() ${U_i}$

s by

${U_i}$

s by

![]() $REU$

.) Since

$REU$

.) Since

the requirement that

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = 0$

and

$R\left( 0 \right) = 0$

and

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = 1$

corresponds to the requirement that the sum of the

$R\left( 1 \right) = 1$

corresponds to the requirement that the sum of the

![]() ${r_i}$

, and thus the width of the above diagram, is 1. This again yields the convenience that

${r_i}$

, and thus the width of the above diagram, is 1. This again yields the convenience that

![]() ${U_n} \le REU\left( G \right) \le {U_0}$

.

${U_n} \le REU\left( G \right) \le {U_0}$

.

4. Rescaling

$R$

Beyond

$R$

Beyond

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

From looking at these calculations geometrically, it is clear that the requirement that

![]() $R:\left[ {0,1\left] \to \right[0,1} \right]$

is in some sense an arbitrary convention. In this section I explore how the decision rule as defined above works when

$R:\left[ {0,1\left] \to \right[0,1} \right]$

is in some sense an arbitrary convention. In this section I explore how the decision rule as defined above works when

![]() $R$

sends

$R$

sends

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

to some other finite interval, as illustrated in Figure 7. I show that the resulting decision rule is reasonable as long as

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

to some other finite interval, as illustrated in Figure 7. I show that the resulting decision rule is reasonable as long as

![]() $R\left( w \right)$

is continuous and strictly increasing so that all the

$R\left( w \right)$

is continuous and strictly increasing so that all the

![]() ${r_i}$

are strictly positive. The project of this section is merely a technical warm-up to the more interesting generalizations of the later sections.

${r_i}$

are strictly positive. The project of this section is merely a technical warm-up to the more interesting generalizations of the later sections.

Figure 7. Illustration of non-

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

risk-weighting and utility.

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

risk-weighting and utility.

To calculate the area under the steps using the vertical rectangles is fairly straightforward even when

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) \ne 0$

and

$R\left( 0 \right) \ne 0$

and

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) \ne 1$

, as shown in Figure 8. Recall that if the

$R\left( 1 \right) \ne 1$

, as shown in Figure 8. Recall that if the

![]() ${P_i}$

are the cumulative probabilities

${P_i}$

are the cumulative probabilities

![]() ${P_i} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 0}^i {p_j}$

, we define

${P_i} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 0}^i {p_j}$

, we define

![]() ${r_i} = R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{i - 1}}} \right)$

as the marginal risk-weightings, with

${r_i} = R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{i - 1}}} \right)$

as the marginal risk-weightings, with

![]() ${P_{ - 1}} = 0$

. Then the risk-weighted expected utility is given by

${P_{ - 1}} = 0$

. Then the risk-weighted expected utility is given by

![]() $REU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n {r_i} \cdot {U_i}$

.

$REU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n {r_i} \cdot {U_i}$

.

Figure 8. Risk-weighted expected utility calculated with vertical rectangles, with non-

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

risk function.

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

risk function.

For the horizontal rectangles, we use the marginal utilities (that is,

![]() ${u_i} = {U_i} - {U_{i + 1}}$

, with the special convention that

${u_i} = {U_i} - {U_{i + 1}}$

, with the special convention that

![]() ${U_{n + 1}} = 0$

) and the risk-weighted cumulative probabilities. However, as shown in Figure 9, we need to apply a correction to deal with the fact that

${U_{n + 1}} = 0$

) and the risk-weighted cumulative probabilities. However, as shown in Figure 9, we need to apply a correction to deal with the fact that

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) \ne 0$

. Thus, we get

$R\left( 0 \right) \ne 0$

. Thus, we get

![]() $REU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n {u_i} \cdot R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - {U_0} \cdot R\left( 0 \right)$

. When

$REU\left( G \right) = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 0}^n {u_i} \cdot R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - {U_0} \cdot R\left( 0 \right)$

. When

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) \ne 0$

, we need a correction term when using the method of horizontal rectangles. But no correction terms were needed when using the method of vertical rectangles, based on

$R\left( 0 \right) \ne 0$

, we need a correction term when using the method of horizontal rectangles. But no correction terms were needed when using the method of vertical rectangles, based on

![]() $r$

rather than

$r$

rather than

![]() $R$

. These correction terms will often show up when using

$R$

. These correction terms will often show up when using

![]() $R$

rather than

$R$

rather than

![]() $r$

.Footnote

1

$r$

.Footnote

1

Figure 9. Risk-weighted expected utility calculated with horizontal rectangles, with non-

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

risk function.

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

risk function.

Whenever

![]() $R$

is strictly increasing and the

$R$

is strictly increasing and the

![]() ${p_i}$

are all positive, the

${p_i}$

are all positive, the

![]() ${r_i}$

will all be positive, so every cumulative utility will appear positively in the calculation, so the rule will still satisfy stochastic dominance. However, we can no longer guarantee the convenience of

${r_i}$

will all be positive, so every cumulative utility will appear positively in the calculation, so the rule will still satisfy stochastic dominance. However, we can no longer guarantee the convenience of

![]() $REU$

lying between the minimum and maximum utilities of the gamble. Instead, we have a correction term given by the width of the relevant shape, which is

$REU$

lying between the minimum and maximum utilities of the gamble. Instead, we have a correction term given by the width of the relevant shape, which is

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) - R\left( 0 \right)$

. That is, instead of

$R\left( 1 \right) - R\left( 0 \right)$

. That is, instead of

![]() ${U_n} \le REU\left( G \right) \le {U_0}$

, we now get that

${U_n} \le REU\left( G \right) \le {U_0}$

, we now get that

![]() ${U_n} \cdot \left( {R\left( 1 \right) - R\left( 0 \right)} \right) \le REU\left( G \right) \le {U_0} \cdot \left( {R\left( 1 \right) - R\left( 0 \right)} \right)$

.

${U_n} \cdot \left( {R\left( 1 \right) - R\left( 0 \right)} \right) \le REU\left( G \right) \le {U_0} \cdot \left( {R\left( 1 \right) - R\left( 0 \right)} \right)$

.

5. Affine Transformations

Let

![]() $a,b$

be real numbers, with

$a,b$

be real numbers, with

![]() $a \gt 0$

. Then we say that

$a \gt 0$

. Then we say that

![]() $f\left( x \right) = ax + b$

is an affine transformation. It is familiar that the utility scale is, in a sense, only meaningful up to affine transformation.

$f\left( x \right) = ax + b$

is an affine transformation. It is familiar that the utility scale is, in a sense, only meaningful up to affine transformation.

If

![]() $G$

is any gamble, let

$G$

is any gamble, let

![]() $f\left( G \right)$

be the gamble that replaces each cumulative utility

$f\left( G \right)$

be the gamble that replaces each cumulative utility

![]() $U$

by

$U$

by

![]() $f\left( U \right)$

. From the formulation of

$f\left( U \right)$

. From the formulation of

![]() $EU$

in terms of vertical rectangles, it is straightforward to see that

$EU$

in terms of vertical rectangles, it is straightforward to see that

![]() $EU\left( {f\left( G \right)} \right) = f\left( {EU\left( G \right)} \right)$

. Similarly, from the formulation of

$EU\left( {f\left( G \right)} \right) = f\left( {EU\left( G \right)} \right)$

. Similarly, from the formulation of

![]() $REU$

in terms of vertical rectangles, it is straightforward to see that

$REU$

in terms of vertical rectangles, it is straightforward to see that

![]() $REU\left( {f\left( G \right)} \right) = f\left( {REU\left( G \right)} \right)$

. Thus, changing the utility scale by an affine transformation doesn’t change any pairwise evaluation of gambles.

$REU\left( {f\left( G \right)} \right) = f\left( {REU\left( G \right)} \right)$

. Thus, changing the utility scale by an affine transformation doesn’t change any pairwise evaluation of gambles.

Now that we have considered

![]() $R$

that send the

$R$

that send the

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval to some other interval, we can also consider what happens with an affine transformation of

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval to some other interval, we can also consider what happens with an affine transformation of

![]() $R$

rather than

$R$

rather than

![]() $U$

. Let

$U$

. Let

![]() $f\left( x \right) = ax + b$

be an affine transformation, let

$f\left( x \right) = ax + b$

be an affine transformation, let

![]() $R{\rm{'}}\left( x \right) = f\left( {R\left( x \right)} \right)$

, and let

$R{\rm{'}}\left( x \right) = f\left( {R\left( x \right)} \right)$

, and let

![]() $R{\rm{'}}EU\left( G \right)$

be calculated with

$R{\rm{'}}EU\left( G \right)$

be calculated with

![]() $R{\rm{'}}$

instead of

$R{\rm{'}}$

instead of

![]() $R$

. Notice that

$R$

. Notice that

![]() $r{{\rm{'}}_i} = a \cdot {r_i}$

. Thus, using the vertical calculations in terms of these marginal risk weightings, it is easy to see that

$r{{\rm{'}}_i} = a \cdot {r_i}$

. Thus, using the vertical calculations in terms of these marginal risk weightings, it is easy to see that

![]() $R{\rm{'}}EU\left( G \right) = a \cdot REU\left( G \right)$

. Since

$R{\rm{'}}EU\left( G \right) = a \cdot REU\left( G \right)$

. Since

![]() $a$

is positive, changing the scale of risk-weighting by an affine transformation again doesn’t change any pairwise evaluations of gambles. Since the finite interval

$a$

is positive, changing the scale of risk-weighting by an affine transformation again doesn’t change any pairwise evaluations of gambles. Since the finite interval

![]() $\left[ {{R_0},{R_1}} \right]$

is related to the interval

$\left[ {{R_0},{R_1}} \right]$

is related to the interval

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

by the affine transformation

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

by the affine transformation

![]() $f\left( x \right) = \left( {{R_1} - {R_0}} \right)x + {R_0}$

, this means that, for every risk-weighting function with any finite interval, there is a unique risk-weighting function with the interval

$f\left( x \right) = \left( {{R_1} - {R_0}} \right)x + {R_0}$

, this means that, for every risk-weighting function with any finite interval, there is a unique risk-weighting function with the interval

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

that yields all the same pairwise comparisons of gambles.

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

that yields all the same pairwise comparisons of gambles.

6. Infinite Risk-weighting

However, if we allow

![]() $R$

to send

$R$

to send

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

to an infinite interval, we get some essentially new ways of being sensitive to risk, that aren’t equivalent to any risk-weighting function that uses the

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

to an infinite interval, we get some essentially new ways of being sensitive to risk, that aren’t equivalent to any risk-weighting function that uses the

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval. As in the finite case, it will be easier to do the calculations with the vertical rectangle calculation, based on marginal risk-weighting and cumulative utility, while the horizontal calculations with cumulative risk-weighting and marginal utility require a correction term.

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval. As in the finite case, it will be easier to do the calculations with the vertical rectangle calculation, based on marginal risk-weighting and cumulative utility, while the horizontal calculations with cumulative risk-weighting and marginal utility require a correction term.

Some candidate continuous, strictly increasing risk functions from

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

to infinite intervals of the extended real line

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

to infinite intervals of the extended real line

![]() $\left[ { - \infty, + \infty } \right]$

are:

$\left[ { - \infty, + \infty } \right]$

are:

-

$R_1(w)=\tan(\pi w/2)$

, which has range

$R_1(w)=\tan(\pi w/2)$

, which has range

$\left[ {0, + \infty } \right]$

$\left[ {0, + \infty } \right]$

-

${R_2}\left( w \right) = - {\rm{log}}\left( {1 - w} \right)$

, which has range

${R_2}\left( w \right) = - {\rm{log}}\left( {1 - w} \right)$

, which has range

$\left[ {0, + \infty } \right]$

$\left[ {0, + \infty } \right]$

-

$R_3(2)=\log(w)$

, which has range

$R_3(2)=\log(w)$

, which has range

$\left[ { - \infty, 0} \right]$

$\left[ { - \infty, 0} \right]$

-

${R_4}\left( w \right) = - 1/w$

, which has range

${R_4}\left( w \right) = - 1/w$

, which has range

$\left[ { - \infty, - 1} \right]$

$\left[ { - \infty, - 1} \right]$

-

${R_5}\left( w \right) = {\rm{tan}}\pi \left( {w - 1/2} \right)$

, which has range

${R_5}\left( w \right) = {\rm{tan}}\pi \left( {w - 1/2} \right)$

, which has range

$\left[ { - \infty, + \infty } \right]$

$\left[ { - \infty, + \infty } \right]$

Recall that

![]() ${U_i}$

is the

${U_i}$

is the

![]() $i$

th best cumulative utility and

$i$

th best cumulative utility and

![]() ${r_i} = R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{i - 1}}} \right)$

is the marginal risk-weighting of this

${r_i} = R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{i - 1}}} \right)$

is the marginal risk-weighting of this

![]() $i$

th best outcome. When

$i$

th best outcome. When

![]() $G$

is a finite gamble, we said

$G$

is a finite gamble, we said

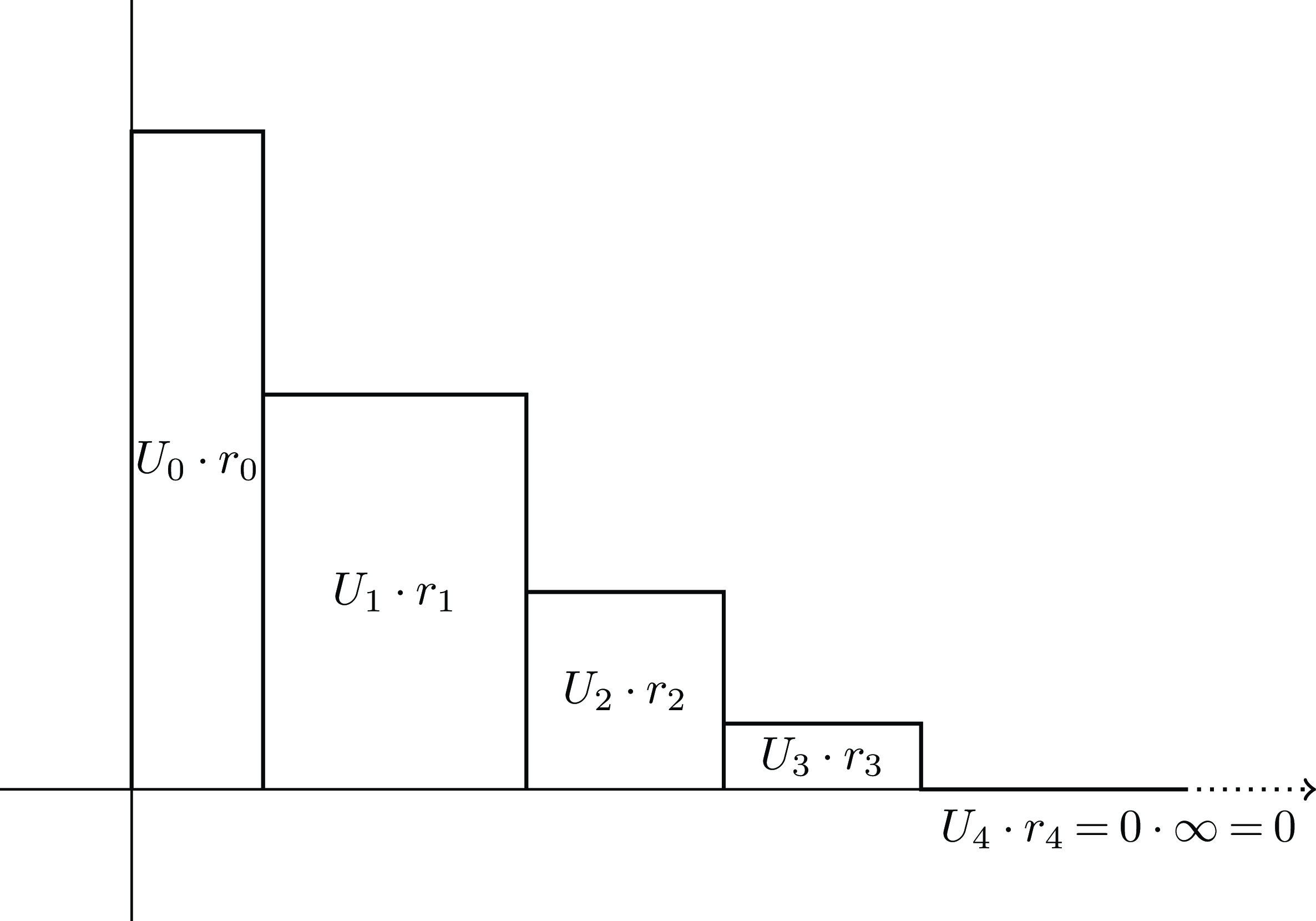

6.1 R(0), is finite, R(1) = +∞

Let us first consider what happens when

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, like with

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, like with

![]() $R_1(w)=\tan(\pi w/2)$

and

$R_1(w)=\tan(\pi w/2)$

and

![]() ${R_2}\left( w \right) = - {\rm{log}}\left( {1 - w} \right)$

. In these cases,

${R_2}\left( w \right) = - {\rm{log}}\left( {1 - w} \right)$

. In these cases,

![]() $R\left( {{P_n}} \right) = + \infty $

, so

$R\left( {{P_n}} \right) = + \infty $

, so

![]() ${r_n} = R\left( {{P_n}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{n - 1}}} \right) = + \infty $

. Thus, each of these formulas will have an infinite term, unless

${r_n} = R\left( {{P_n}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{n - 1}}} \right) = + \infty $

. Thus, each of these formulas will have an infinite term, unless

![]() ${u_n} = {U_n} = 0$

, as in Figure 10. For now, we use the convention that

${u_n} = {U_n} = 0$

, as in Figure 10. For now, we use the convention that

![]() $\infty \cdot 0 = 0$

. In this case,

$\infty \cdot 0 = 0$

. In this case,

![]() $REU\left( G \right)$

will be finite. But if

$REU\left( G \right)$

will be finite. But if

![]() ${U_n} \gt 0$

, then

${U_n} \gt 0$

, then

![]() $REU\left( G \right) = + \infty $

, and if

$REU\left( G \right) = + \infty $

, and if

![]() ${U_n} \lt 0$

, then

${U_n} \lt 0$

, then

![]() $REU\left( G \right) = - \infty $

. These risk functions where

$REU\left( G \right) = - \infty $

. These risk functions where

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

encode a preference for whichever gamble has higher minimum utility, if these minimum utilities are of different signs.

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

encode a preference for whichever gamble has higher minimum utility, if these minimum utilities are of different signs.

Figure 10.

![]() $REU$

when

$REU$

when

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = 0$

,

$R\left( 0 \right) = 0$

,

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, and

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, and

![]() ${U_n} = 0$

.

${U_n} = 0$

.

When the minimum utility of the two gambles has the same sign (i.e. both positive, both negative, or both 0), the situation is slightly more complicated. If they are both positive, or both negative, our official definition of

![]() $REU$

gives them both the same infinite value. However, if we think of utility as only defined up to affine transformation, it is natural to argue that we shouldn’t necessarily think of gambles with the same infinite

$REU$

gives them both the same infinite value. However, if we think of utility as only defined up to affine transformation, it is natural to argue that we shouldn’t necessarily think of gambles with the same infinite

![]() $REU$

as equivalent. Instead, we should apply an affine transformation to the utility scale that sends the minimum utility of one of these gambles to 0, so that this gamble has finite

$REU$

as equivalent. Instead, we should apply an affine transformation to the utility scale that sends the minimum utility of one of these gambles to 0, so that this gamble has finite

![]() $REU$

. If the minimum utility of the other is distinct, then that other gamble has infinite

$REU$

. If the minimum utility of the other is distinct, then that other gamble has infinite

![]() $REU$

on this scale (positive if its minimum utility is higher, negative if lower).Footnote

2

$REU$

on this scale (positive if its minimum utility is higher, negative if lower).Footnote

2

Thus, this risk function encodes a strict preference for whichever gamble has a less bad worst possible outcome, regardless of any other outcomes of either gamble. I will say that any such preferences have the maximin property. There is no strictly increasing risk-weighting function on the

![]() $\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval that encodes preferences with the maximin property.

$\left[ {0,1} \right]$

interval that encodes preferences with the maximin property.

Buchak (p. 68) mentions that if one were to allow non-strictly increasing risk-weighting functions, then the function given by

![]() ${R_{min}}\left( 1 \right) = 1$

and

${R_{min}}\left( 1 \right) = 1$

and

![]() ${R_{min}}\left( x \right) = 0$

when

${R_{min}}\left( x \right) = 0$

when

![]() $x \lt 1$

, which I call “classic maximin”, would have the maximin property. But there are some important differences when we use one of these strictly increasing functions that goes to

$x \lt 1$

, which I call “classic maximin”, would have the maximin property. But there are some important differences when we use one of these strictly increasing functions that goes to

![]() $ + \infty $

. For one thing, since

$ + \infty $

. For one thing, since

![]() ${R_{min}}\left( x \right) = 0$

whenever

${R_{min}}\left( x \right) = 0$

whenever

![]() $x \lt 1$

, we have

$x \lt 1$

, we have

![]() ${R_{min}}EU\left( G \right) = {U_n}$

, and thus that decision rule is strictly indifferent between any two gambles with the same minimum utility. But since

${R_{min}}EU\left( G \right) = {U_n}$

, and thus that decision rule is strictly indifferent between any two gambles with the same minimum utility. But since

![]() ${R_1}$

and

${R_1}$

and

![]() ${R_2}$

are strictly increasing, they satisfy stochastic dominance. Effectively, they lexicographically prefer gambles on the basis of their minimum utility, but among gambles with the same minimum utility, they give some continuous risk-weighted comparison of the gambles based on their other outcomes. I will discuss the differences between classic maximin and strictly increasing functions to the

${R_2}$

are strictly increasing, they satisfy stochastic dominance. Effectively, they lexicographically prefer gambles on the basis of their minimum utility, but among gambles with the same minimum utility, they give some continuous risk-weighted comparison of the gambles based on their other outcomes. I will discuss the differences between classic maximin and strictly increasing functions to the

![]() $\left[ {0, + \infty } \right]$

interval in section 7.

$\left[ {0, + \infty } \right]$

interval in section 7.

Among these strictly increasing risk functions with the maximin property, we can investigate the difference between

![]() ${R_1}$

and

${R_1}$

and

![]() ${R_2}$

, by seeing how they evaluate two different standardized gambles. Let

${R_2}$

, by seeing how they evaluate two different standardized gambles. Let

![]() ${G_1}$

be a gamble with

${G_1}$

be a gamble with

![]() $1/2$

probability of outcome 2, and

$1/2$

probability of outcome 2, and

![]() $1/2$

probability of outcome 0, as shown in Figure 11, and let

$1/2$

probability of outcome 0, as shown in Figure 11, and let

![]() ${G_2}$

be a gamble with

${G_2}$

be a gamble with

![]() $1/3$

probability of three different outcomes, one with utility

$1/3$

probability of three different outcomes, one with utility

![]() $2$

, one with utility

$2$

, one with utility

![]() $0$

, and one with utility

$0$

, and one with utility

![]() $0 \lt x \lt 2$

, as illustrated in Figure 12.

$0 \lt x \lt 2$

, as illustrated in Figure 12.

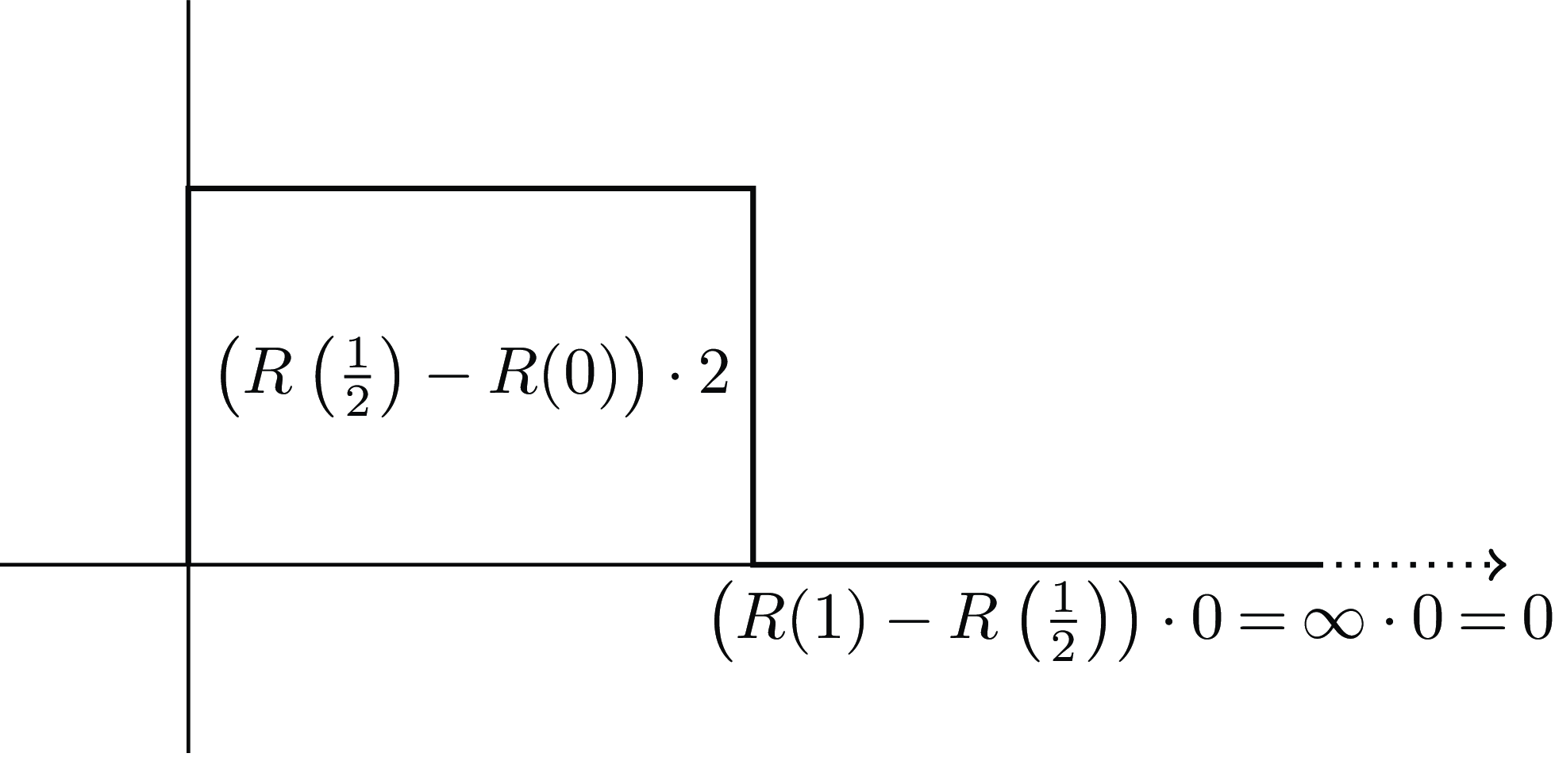

Figure 11.

![]() $REU$

of

$REU$

of

![]() ${G_1}$

, with probability

${G_1}$

, with probability

![]() $1/2$

of outcomes 2 or 0, when

$1/2$

of outcomes 2 or 0, when

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

.

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

.

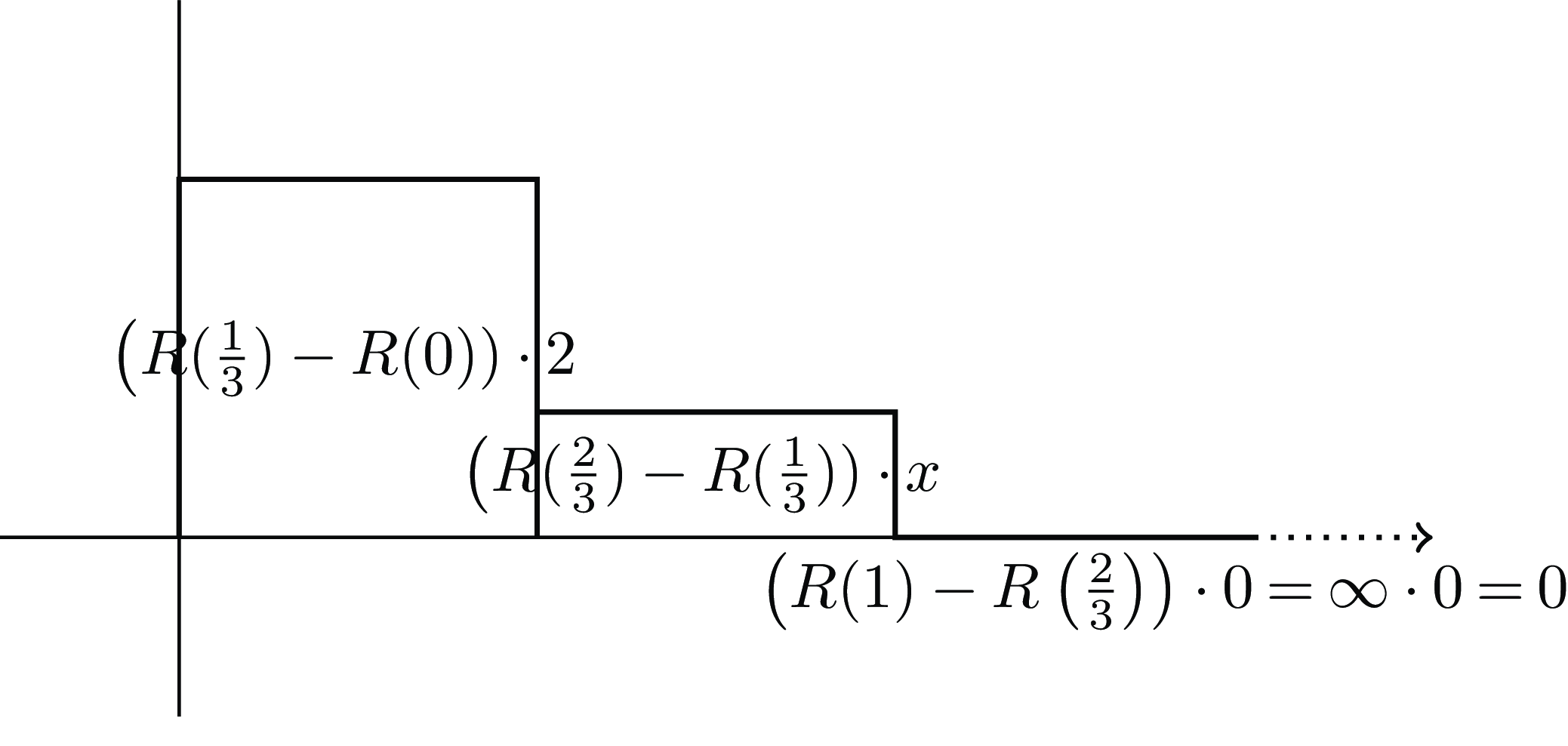

Figure 12.

![]() $RU$

of

$RU$

of

![]() ${G_2}$

, with probability

${G_2}$

, with probability

![]() $1/3$

of outcomes 2,

$1/3$

of outcomes 2,

![]() $x$

, or 0, when

$x$

, or 0, when

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

.

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

.

For a risk-neutral decision-maker, these gambles would be equal when

![]() $x = 1$

. But both of these risk functions are risk-averse, and would thus strictly prefer the gamble

$x = 1$

. But both of these risk functions are risk-averse, and would thus strictly prefer the gamble

![]() ${G_2}$

with lower chance of utility 0 in the case where the risk-neutral decision-maker judges them as equivalent. We can get one measure of how risk-averse they are by seeing how far we have to reduce

${G_2}$

with lower chance of utility 0 in the case where the risk-neutral decision-maker judges them as equivalent. We can get one measure of how risk-averse they are by seeing how far we have to reduce

![]() $x$

below 1 to make this decision rule judge the two gambles to be equivalent.

$x$

below 1 to make this decision rule judge the two gambles to be equivalent.

Using

![]() $R_1(w) = \tan(\pi w/2)$

, for

$R_1(w) = \tan(\pi w/2)$

, for

![]() ${G_1}$

we get:

${G_1}$

we get:

For

![]() ${G_2}$

we get:

${G_2}$

we get:

These values are equal when

![]() ${2 \over {\sqrt 3 }} + x\left( {\sqrt 3 - 1/\sqrt 3 } \right) = 2$

, which occurs when

${2 \over {\sqrt 3 }} + x\left( {\sqrt 3 - 1/\sqrt 3 } \right) = 2$

, which occurs when

![]() $2 + x\left( {3 - 1} \right) = 2\sqrt 3 $

, so that

$2 + x\left( {3 - 1} \right) = 2\sqrt 3 $

, so that

![]() $x = \sqrt 3 - 1 \approx 0.732$

.

$x = \sqrt 3 - 1 \approx 0.732$

.

Using

![]() ${R_2}\left( 2 \right) = - {\rm{log}}\left( {1 - w} \right)$

, for

${R_2}\left( 2 \right) = - {\rm{log}}\left( {1 - w} \right)$

, for

![]() ${G_1}$

we get:

${G_1}$

we get:

For

![]() ${G_2}$

we get:

${G_2}$

we get:

These values are equal when

![]() $2{\rm{log}}{3 \over 2} + x{\rm{log}}2 = 2{\rm{log}}2$

, or when

$2{\rm{log}}{3 \over 2} + x{\rm{log}}2 = 2{\rm{log}}2$

, or when ![]() , so that

, so that

![]() $1 - x/2 = {\rm{lo}}{{\rm{g}}_2}\left( {3/2} \right)$

, so that

$1 - x/2 = {\rm{lo}}{{\rm{g}}_2}\left( {3/2} \right)$

, so that

![]() $x = 2\left( {1 - {\rm{lo}}{{\rm{g}}_2}\left( {3/2} \right)} \right) \approx 0.830$

.

$x = 2\left( {1 - {\rm{lo}}{{\rm{g}}_2}\left( {3/2} \right)} \right) \approx 0.830$

.

Thus, we can see that distinct risk functions that encode preferences with the maximin property by having

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

can yield different comparisons of gambles with the same minimum utility. For this particular comparison, it appears that

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

can yield different comparisons of gambles with the same minimum utility. For this particular comparison, it appears that

![]() ${R_1}$

is more risk-averse, even though both have the maximin property.

${R_1}$

is more risk-averse, even though both have the maximin property.

6.2 R(0) = −∞, R(1) is finite

A similar set of considerations applies when

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

, as with

$R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

, as with

![]() $R_3(w)=\log(w)$

and

$R_3(w)=\log(w)$

and

![]() ${R_4}\left( w \right) = - 1/w$

. In these cases, a finite gamble will have finite

${R_4}\left( w \right) = - 1/w$

. In these cases, a finite gamble will have finite

![]() $REU$

iff its maximum utility,

$REU$

iff its maximum utility,

![]() ${U_0} = 0$

, as illustrated in Figure 13. (Note that since

${U_0} = 0$

, as illustrated in Figure 13. (Note that since

![]() ${U_0}$

is the highest utility, all other outcomes of this gamble must have negative utility.)

${U_0}$

is the highest utility, all other outcomes of this gamble must have negative utility.)

Figure 13.

![]() $REU$

calculated when

$REU$

calculated when

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

,

$R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

,

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = 0$

, and

$R\left( 1 \right) = 0$

, and

![]() ${U_0} = 0$

.

${U_0} = 0$

.

If

![]() ${U_0}$

is positive, then

${U_0}$

is positive, then

![]() $REU\left( G \right) = + \infty $

, and if

$REU\left( G \right) = + \infty $

, and if

![]() ${U_0}$

is negative, then

${U_0}$

is negative, then

![]() $REU\left( G \right) = - \infty $

. Since

$REU\left( G \right) = - \infty $

. Since

![]() ${U_0}$

is the highest utility, applying an affine transformation to send the highest utility of one of a pair of gambles to 0 indicates that this

${U_0}$

is the highest utility, applying an affine transformation to send the highest utility of one of a pair of gambles to 0 indicates that this

![]() $R$

will encode preferences with what I call the maximax property. But again, such a risk function will encode some sort of continuous preference relation that obeys stochastic dominance among gambles with the same highest utility, unlike classic maximax, given by the risk function

$R$

will encode preferences with what I call the maximax property. But again, such a risk function will encode some sort of continuous preference relation that obeys stochastic dominance among gambles with the same highest utility, unlike classic maximax, given by the risk function

![]() ${R_{max}}$

with

${R_{max}}$

with

![]() ${R_{max}}\left( 0 \right) = 0$

and

${R_{max}}\left( 0 \right) = 0$

and

![]() ${R_{max}}\left( x \right) = 1$

whenever

${R_{max}}\left( x \right) = 1$

whenever

![]() $x \gt 0$

.

$x \gt 0$

.

We can again compare risk-weighting functions

![]() ${R_3}$

and

${R_3}$

and

![]() ${R_4}$

on the same standardized pair of reference gambles, and see that

${R_4}$

on the same standardized pair of reference gambles, and see that

![]() ${R_3}$

says they are equal when

${R_3}$

says they are equal when

![]() $x = 3 - \sqrt 3 \approx 1.268$

, and

$x = 3 - \sqrt 3 \approx 1.268$

, and

![]() ${R_4}$

does when

${R_4}$

does when

![]() $x = 2{\rm{lo}}{{\rm{g}}_2}\left( {3/2} \right) \approx 1.170$

. Both are risk-seeking, but

$x = 2{\rm{lo}}{{\rm{g}}_2}\left( {3/2} \right) \approx 1.170$

. Both are risk-seeking, but

![]() ${R_3}$

is more so for this particular pair.

${R_3}$

is more so for this particular pair.

6.3 R(0) = −∞, R(1) = +∞

When

![]() $R$

goes off to infinity in both directions, as with

$R$

goes off to infinity in both directions, as with

![]() ${R_5}\left( w \right) = {\rm{tan}}\pi \left( {w - 1/2} \right)$

, every gamble where some outcome has both non-zero utility and non-zero probability will have an infinite term somewhere in the calculation. However, there are still some meaningful ways that this function can be used to make risk-sensitive decisions among finite gambles.

${R_5}\left( w \right) = {\rm{tan}}\pi \left( {w - 1/2} \right)$

, every gamble where some outcome has both non-zero utility and non-zero probability will have an infinite term somewhere in the calculation. However, there are still some meaningful ways that this function can be used to make risk-sensitive decisions among finite gambles.

In the case of risk functions that go off to infinity at just one end, we could apply an affine transformation to the utility scale to send the utility of one of the gambles at that end to 0. If the other gamble is non-zero at that point, it has (positive or negative) infinite

![]() $REU$

, and we can compare that way. But if both have the same utility at this infinitely weighted end-point, then sending one to 0 there sends the other to 0 there as well. This leaves both gambles with finite

$REU$

, and we can compare that way. But if both have the same utility at this infinitely weighted end-point, then sending one to 0 there sends the other to 0 there as well. This leaves both gambles with finite

![]() $REU$

, and we can compare these numbers to see which is preferred.

$REU$

, and we can compare these numbers to see which is preferred.

But another way to achieve the same effect is to make the comparison by comparing the infinitely weighted endpoint, if the gambles differ there, and to just ignore that endpoint if the two gambles agree there, without changing the utility scale. For gambles that agree at this endpoint, calculating the finite area under the parts where they differ is sufficient to yield the comparison.Footnote 3 For a risk function that goes off to infinity at both ends, we can compare finite gambles similarly, by first looking at the infinitely weighted ends, and then looking elsewhere if the gambles agree there.

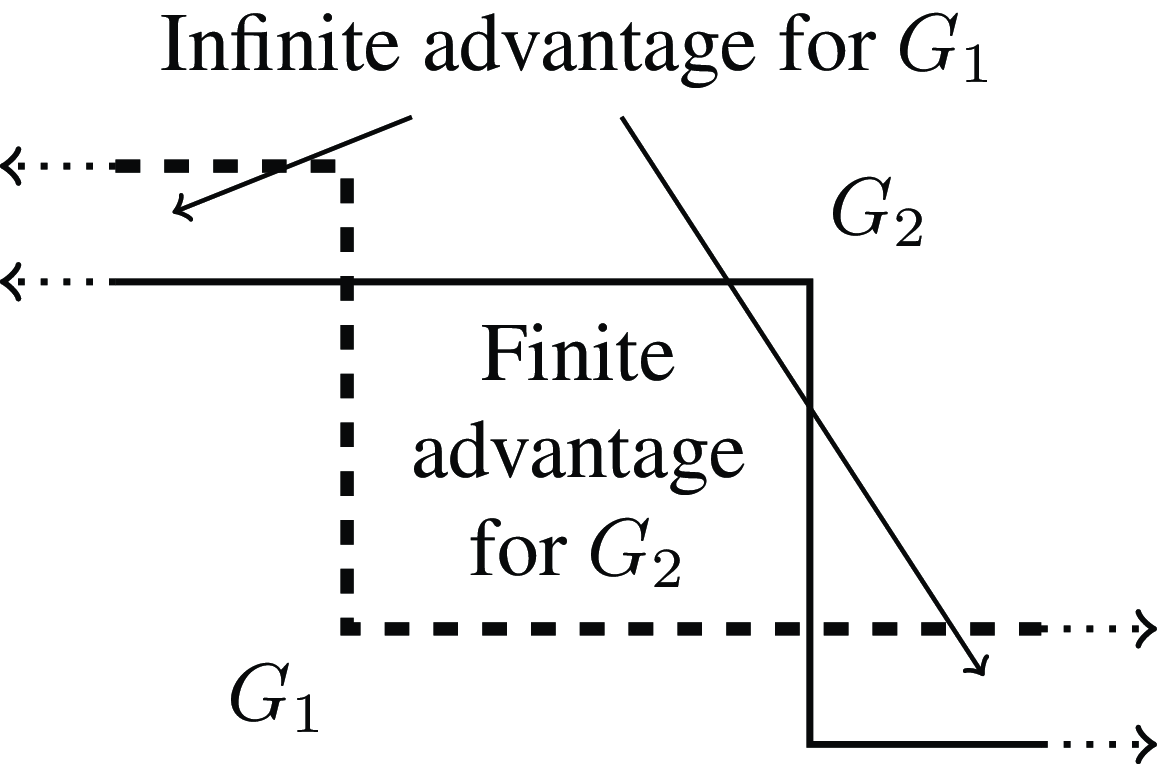

When the maximum and minimum utilities of two gambles aren’t both the same, then there are some infinite regions in which the utilities of the two gambles differ. If

![]() ${G_1}$

has higher maximum and higher minimum than

${G_1}$

has higher maximum and higher minimum than

![]() ${G_2}$

, as illustrated in Figure 14, then both of those infinite regions count towards it, and the other can only get at most a finite boost in between, so

${G_2}$

, as illustrated in Figure 14, then both of those infinite regions count towards it, and the other can only get at most a finite boost in between, so

![]() ${G_1}$

is strictly preferred. But if

${G_1}$

is strictly preferred. But if

![]() ${G_1}$

has higher maximum and

${G_1}$

has higher maximum and

![]() ${G_2}$

has higher minimum, then the two infinite regions count towards the different gambles, and the decision rule gives no way to compare them, as illustrated in Figure 15.

${G_2}$

has higher minimum, then the two infinite regions count towards the different gambles, and the decision rule gives no way to compare them, as illustrated in Figure 15.

Figure 14.

![]() $REU$

calculated when

$REU$

calculated when

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

,

$R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

,

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, and

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, and

![]() ${G_1}$

has both higher max and min than

${G_1}$

has both higher max and min than

![]() ${G_2}$

.

${G_2}$

.

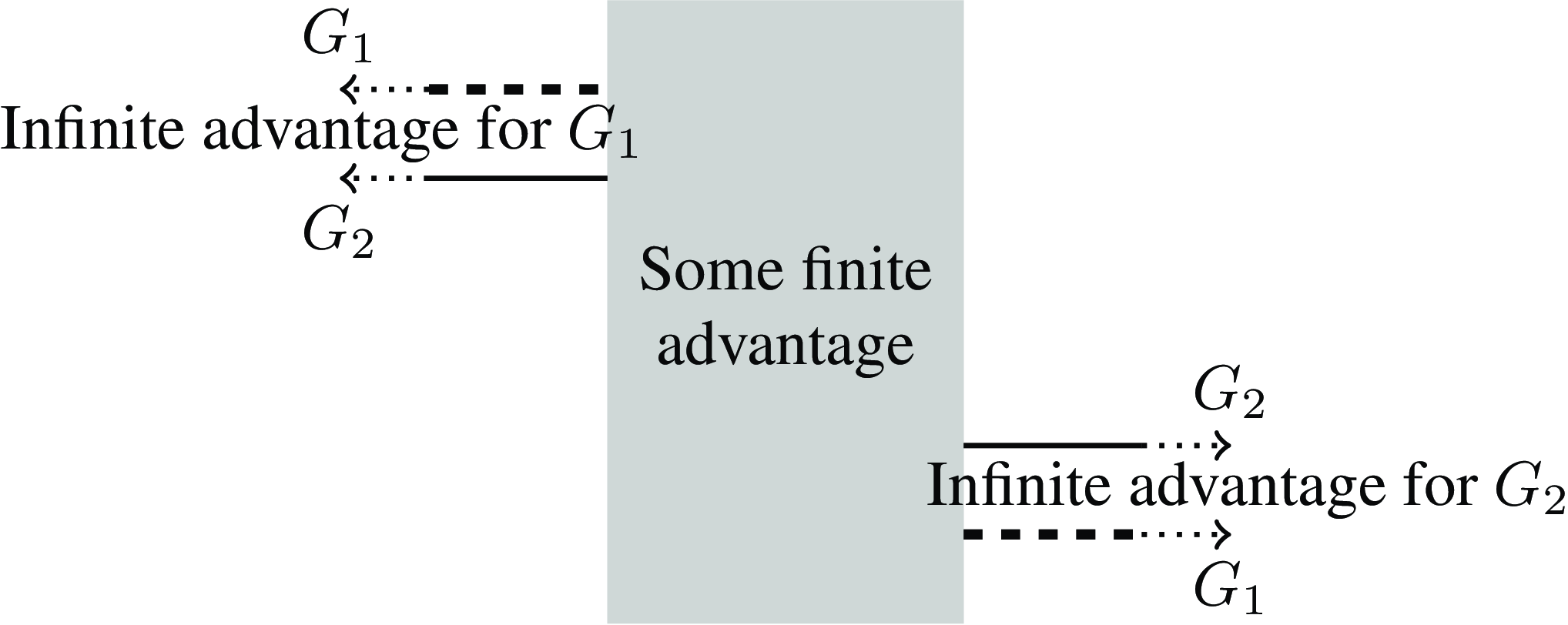

Figure 15.

![]() $REU$

calculated when

$REU$

calculated when

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

,

$R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

,

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, and

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, and

![]() ${G_1}$

has higher max while

${G_1}$

has higher max while

![]() ${G_2}$

has higher min.

${G_2}$

has higher min.

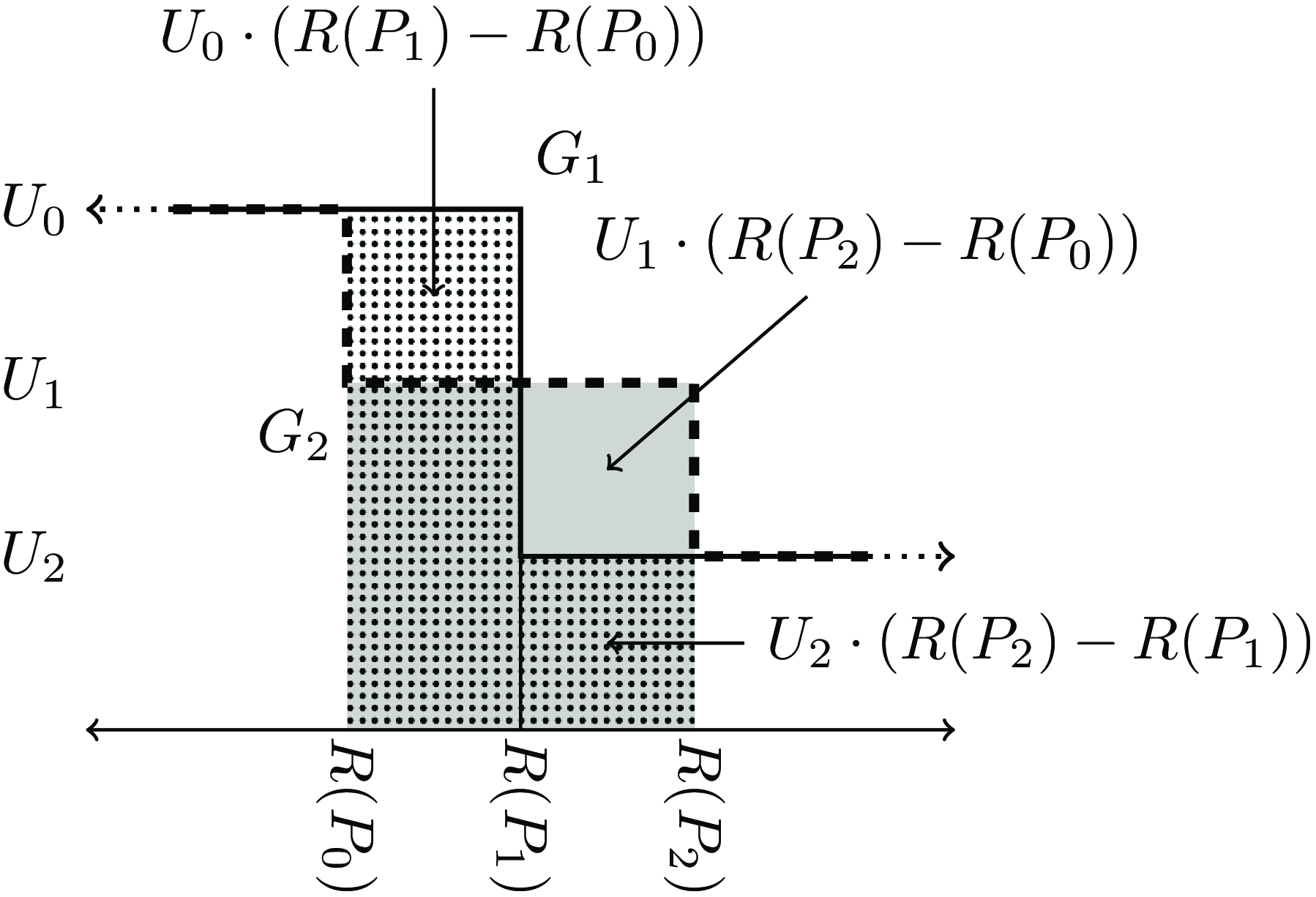

When the gambles agree at both ends (as with our two-outcome

![]() ${G_1}$

and three-outcome

${G_1}$

and three-outcome

![]() ${G_2}$

from earlier), we just compare the middle area where they differ, and ignore the infinite areas on each end where they agree, as shown in Figure 16. These two gambles are evaluated equally when

${G_2}$

from earlier), we just compare the middle area where they differ, and ignore the infinite areas on each end where they agree, as shown in Figure 16. These two gambles are evaluated equally when

![]() ${U_0} \cdot \left( {R\left( {{P_1}} \right) - R\left( {{P_0}} \right)} \right) + {U_2} \cdot \left( {R\left( {{P_2}} \right) - R\left( {{P_1}} \right)} \right) = {U_1} \cdot (R\left( {{P_2}} \right) - R\left( {{P_0}} \right)$

. If we use

${U_0} \cdot \left( {R\left( {{P_1}} \right) - R\left( {{P_0}} \right)} \right) + {U_2} \cdot \left( {R\left( {{P_2}} \right) - R\left( {{P_1}} \right)} \right) = {U_1} \cdot (R\left( {{P_2}} \right) - R\left( {{P_0}} \right)$

. If we use

![]() ${R_5}\left( w \right) = {\rm{tan}}\pi \left( {w - 1/2} \right)$

, using the same numbers from earlier (so

${R_5}\left( w \right) = {\rm{tan}}\pi \left( {w - 1/2} \right)$

, using the same numbers from earlier (so

![]() ${P_0} = 1/3$

,

${P_0} = 1/3$

,

![]() ${P_1} = 1/2$

,

${P_1} = 1/2$

,

![]() ${P_2} = 2/3$

,

${P_2} = 2/3$

,

![]() ${U_0} = 2$

,

${U_0} = 2$

,

![]() ${U_1} = x$

,

${U_1} = x$

,

![]() ${U_2} = 0$

) then we see that the gambles are equal when

${U_2} = 0$

) then we see that the gambles are equal when

Figure 16. Comparative

![]() $REU$

calculated when

$REU$

calculated when

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

,

$R\left( 0 \right) = - \infty $

,

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, where

$R\left( 1 \right) = + \infty $

, where

![]() ${G_1}$

and

${G_1}$

and

![]() ${G_2}$

have the same max (

${G_2}$

have the same max (

![]() ${U_0}$

) and min (

${U_0}$

) and min (

![]() ${U_2}$

), but

${U_2}$

), but

![]() ${G_1}$

has probability

${G_1}$

has probability

![]() ${P_1}$

of

${P_1}$

of

![]() ${U_0}$

, while

${U_0}$

, while

![]() ${G_2}$

has probability

${G_2}$

has probability

![]() ${P_0}$

of

${P_0}$

of

![]() ${U_0}$

, and

${U_0}$

, and

![]() ${P_2} - {P_0}$

of

${P_2} - {P_0}$

of

![]() ${U_1}$

.

${U_1}$

.

Since

![]() ${\rm{tan}}0 = 0$

and

${\rm{tan}}0 = 0$

and

![]() ${\rm{tan}} - x = - {\rm{tan}}x$

, this simplifies to

${\rm{tan}} - x = - {\rm{tan}}x$

, this simplifies to

![]() $2{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 6} = 2\,x\,{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 6}$

, so that

$2{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 6} = 2\,x\,{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 6}$

, so that

![]() $x = 1$

. It is no surprise that we get the same value as the risk-neutral function, because the gambles we are considering here are symmetric about probability

$x = 1$

. It is no surprise that we get the same value as the risk-neutral function, because the gambles we are considering here are symmetric about probability

![]() $1/2$

, as is the risk function.

$1/2$

, as is the risk function.

If instead we use gambles where

![]() ${P_0} = 1/4$

,

${P_0} = 1/4$

,

![]() ${P_1} = 1/3$

,

${P_1} = 1/3$

,

![]() ${P_2} = 1/2$

(and keep

${P_2} = 1/2$

(and keep

![]() ${U_0} = 2,{U_1} = x,{U_2} = 0$

), then the gambles are equal when

${U_0} = 2,{U_1} = x,{U_2} = 0$

), then the gambles are equal when

This simplifies to

![]() $2{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 4} - 2{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 6} = x{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 4}.$

Since

$2{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 4} - 2{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 6} = x{\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 4}.$

Since

![]() ${\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 4} = 1$

and

${\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 4} = 1$

and

![]() ${\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 6} = 1/\sqrt 3 $

, this simplifies to

${\rm{tan}}{\pi \over 6} = 1/\sqrt 3 $

, this simplifies to

![]() $x = 2\left( {1 - 1/\sqrt 3 } \right) \approx 0.845$

. Under standard

$x = 2\left( {1 - 1/\sqrt 3 } \right) \approx 0.845$

. Under standard

![]() $EU$

, these would have been equal when

$EU$

, these would have been equal when

![]() $x = 2/3$

, so this behaviour is somewhat risk-seeking (as would be expected from the fact that the risk function is concave down in the region below

$x = 2/3$

, so this behaviour is somewhat risk-seeking (as would be expected from the fact that the risk function is concave down in the region below

![]() $1/2$

).

$1/2$

).

When the risk function

![]() $R\left( w \right)$

goes both to

$R\left( w \right)$

goes both to

![]() $ + \infty $

as

$ + \infty $

as

![]() $w$

goes to

$w$

goes to

![]() $1$

, and to

$1$

, and to

![]() $ - \infty $

as

$ - \infty $

as

![]() $w$

goes to

$w$

goes to

![]() $0$

, the decision is lexicographically sensitive to both the maximum and the minimum utility of the gamble. If one gamble has better maximum and minimum than another, then it is preferred. If two gambles have the same maximum and minimum, then the behaviour of

$0$

, the decision is lexicographically sensitive to both the maximum and the minimum utility of the gamble. If one gamble has better maximum and minimum than another, then it is preferred. If two gambles have the same maximum and minimum, then the behaviour of

![]() $R$

on intermediate probabilities matters. If one gamble has higher maximum and the other has higher minimum, then this risk function yields no clear way to decide between them.

$R$

on intermediate probabilities matters. If one gamble has higher maximum and the other has higher minimum, then this risk function yields no clear way to decide between them.

Note that in the case of bounded risk functions that aren’t required to be strictly increasing, we could get lexicographic sensitivity to both endpoints by using

![]() $R\left( 0 \right) = 0$

,

$R\left( 0 \right) = 0$

,

![]() $R\left( 1 \right) = 1$

, and

$R\left( 1 \right) = 1$

, and

![]() $R\left( x \right) = k$

otherwise. As Buchak notes (pp. 68–70), this is formally equivalent to the use of the Hurwicz criterion, treating the worst outcome of the gamble as precisely

$R\left( x \right) = k$

otherwise. As Buchak notes (pp. 68–70), this is formally equivalent to the use of the Hurwicz criterion, treating the worst outcome of the gamble as precisely

![]() $k/\left( {1 - k} \right)$

times as important as the best outcome of the gamble, and giving zero weight to all other outcomes of the gamble. There might be some advantage to such a risk function over the ones I discuss that go to infinity on both sides, in being able to compare the importance of the two endpoints. But just as with

$k/\left( {1 - k} \right)$

times as important as the best outcome of the gamble, and giving zero weight to all other outcomes of the gamble. There might be some advantage to such a risk function over the ones I discuss that go to infinity on both sides, in being able to compare the importance of the two endpoints. But just as with

![]() ${R_{min}}$

and

${R_{min}}$

and

![]() ${R_{max}}$

, the fact that this risk function is not strictly increasing means that it doesn’t respect Buchak’s means-ends motivation – intermediate outcomes make no contribution to the evaluation of the gamble.

${R_{max}}$

, the fact that this risk function is not strictly increasing means that it doesn’t respect Buchak’s means-ends motivation – intermediate outcomes make no contribution to the evaluation of the gamble.

6.4 Infinite risk weighting at other points on the scale

It is hard to put infinite risk-weighting at other points in the scale with a strictly increasing function

![]() $R$

. However, we can do it with a locally strictly increasing

$R$

. However, we can do it with a locally strictly increasing

![]() $R$

that has a singularity, if we use the convention that

$R$

that has a singularity, if we use the convention that

![]() ${r_i}$

is

${r_i}$

is

![]() $\infty $

for any outcome that spans the singularity.Footnote

4

For instance let

$\infty $

for any outcome that spans the singularity.Footnote

4

For instance let

![]() $R(w) = \tan(\pi w)$

, which is locally strictly increasing from finite values toward

$R(w) = \tan(\pi w)$

, which is locally strictly increasing from finite values toward

![]() $ + \infty $

as

$ + \infty $

as

![]() ${P_i}$

increases to

${P_i}$

increases to

![]() $1/2$

, and then is locally strictly increasing from

$1/2$

, and then is locally strictly increasing from

![]() $ - \infty $

to finite values as

$ - \infty $

to finite values as

![]() $P_i$

increases above

$P_i$

increases above

![]() $1/2$

. In this case, we can conventionally stipulate that

$1/2$

. In this case, we can conventionally stipulate that

![]() ${r_i} = \infty $

if

${r_i} = \infty $

if

![]() ${P_{i - 1}} \le 1/2 \le {P_i}$

, and

${P_{i - 1}} \le 1/2 \le {P_i}$

, and

![]() $R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{i - 1}}} \right)$

otherwise. This yields something like a “maximedian” decision rule – it ranks one gamble above another if the median utility for the first is strictly higher than the median utility for the second, and there are no other sources of unbounded value.Footnote

5

$R\left( {{P_i}} \right) - R\left( {{P_{i - 1}}} \right)$

otherwise. This yields something like a “maximedian” decision rule – it ranks one gamble above another if the median utility for the first is strictly higher than the median utility for the second, and there are no other sources of unbounded value.Footnote

5

Additionally, just as it was possible to infinitely prioritize both the top and bottom end of the probability interval with an

![]() $R$

that went to infinity at both ends, it is possible to infinitely prioritize multiple points within the probability interval by using this same trick with a function

$R$

that went to infinity at both ends, it is possible to infinitely prioritize multiple points within the probability interval by using this same trick with a function

![]() $R$

that is everywhere locally strictly increasing, but has finitely many singularities. For instance, use

$R$

that is everywhere locally strictly increasing, but has finitely many singularities. For instance, use

![]() $R{(p_i)}=\tan 3\pi {P_i}$

, and let

$R{(p_i)}=\tan 3\pi {P_i}$

, and let

![]() ${r_i} = \infty $

whenever

${r_i} = \infty $

whenever

![]() $P_{i-1}\leq 1/6\leq P_i$

or

$P_{i-1}\leq 1/6\leq P_i$

or

![]() ${P_{i - 1}} \le 1/2 \le {P_i}$

or

${P_{i - 1}} \le 1/2 \le {P_i}$

or

![]() ${P_{i - 1}} \le 5/6 \le {P_i}$

.Footnote

6

It’s not at all obvious what particular application this sort of risk-weighting function could be useful for, but it is a natural formal extension of Buchak’s

${P_{i - 1}} \le 5/6 \le {P_i}$

.Footnote

6

It’s not at all obvious what particular application this sort of risk-weighting function could be useful for, but it is a natural formal extension of Buchak’s

![]() $REU$

. Importantly, it shows one more way that

$REU$

. Importantly, it shows one more way that

![]() $r$

enables a more direct definition of the risk-weighting rule than

$r$

enables a more direct definition of the risk-weighting rule than

![]() $R$

.

$R$

.

7. Three Ways of Achieving the Maximin and Maximax Properties

As we can see from the calculation with vertical rectangles,

![]() ${r_i}$

is effectively a measure of how important the

${r_i}$

is effectively a measure of how important the

![]() $i$

th best outcome is to the comparison.Footnote

7

This helps explain how the maximin and maximax properties arise for finite gambles – the relevant

$i$

th best outcome is to the comparison.Footnote

7

This helps explain how the maximin and maximax properties arise for finite gambles – the relevant

![]() $r$

assigned infinite weight to one of the two endpoints.Footnote

8