Introduction

The double-key nuclear system in Europe, under which both the United States and the host European countries must authorise the use of nuclear weapons stored on their territory, has been a cornerstone of NATO’s nuclear deterrence policy since the Cold War.Footnote 1 This mechanism allows the United States to maintain strategic control over its nuclear arsenal deployed in Europe, while providing European countries with a degree of participation in the decision to use these weapons, through NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG). It is considered a key element of deterrence in Europe,Footnote 2 especially given suggestions to extend the double-key system to other regions where it currently does not exist, such as the Scandinavian Peninsula.Footnote 3

Although commonly referred to as a ‘dual-key’ arrangement, this terminology can be misleading. In practice, control over the nuclear weapons ultimately remains with the United States. The US president retains sole authority to authorise their use, while the host country cannot employ them independently and can only withhold operational participation. This structural asymmetry, currently being used in four EU/NATO members (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands) and TurkeyFootnote 4 is crucial to understanding both the current logic of the system and the challenges of replicating it under French leadership. However, it also raises a more fundamental question: why would a French-led dual-key system be necessary in the first place? Beyond issues of feasibility, any consideration of a French role must begin with the rationale. As debates over a possible retrenchment of US security guarantees intensify, and as the credibility of B61 deployments is increasingly questioned due to their perceived symbolic and tactical limitations, some European countries may seek alternatives that enhance their strategic autonomy. In this context, a French-led dual-key system could be seen as not merely a replacement but also a political tool to reinforce deterrence, alliance cohesion, and European agency in defence matters.

While various scenarios could be imagined for the implementation of a French-led dual-key arrangement – including gradual extension to additional European countries – the present analysis focuses primarily on whether France could effectively replace the United States in countries currently participating in NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements, such as Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands. This narrower focus allows for a more precise assessment of the technical and doctrinal feasibility of such a transition.

In addition to the double-key system, there is currently US extended deterrence in Europe,Footnote 5 along with the presence of the British and French arsenals, which together constitute a ‘complementary nuclear insurance’.Footnote 6 This contribution is acknowledged in NATO’s Strategic Concept, which recognises its role in the alliance’s security.Footnote 7

However, in a context of growing geopolitical tensions and with the United States reconsidering its global role and, more specifically, its Atlantic commitment,Footnote 8 the possibility of a significant reduction in its military presence in Europe has become a topic of strategic debate.Footnote 9 While some analysts have suggested that the United States may scale back its military presence in Europe to prioritise strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific,Footnote 10 other experts argue that such a withdrawal would significantly weaken US global power projection and could be perceived by adversaries as an opportunity to challenge Western influence.Footnote 11 The internal debate in Washington includes positions that advocate for maintaining or even increasing the US military footprint in Europe, especially in light of ongoing instability in the region. This range of perspectives highlights the uncertainty surrounding future US policy and cautions against assuming a linear trajectory towards disengagement. In light of this situation, it becomes necessary to explore other options available to the European Union countries to maintain their nuclear deterrence in the event of a strategic withdrawal by the United States, which could involve not only conventional means but also nuclear ones.

This scenario raises the question of what alternative options could emerge to ensure nuclear deterrence in Europe without the direct involvement of the United States. One alternative that has gained attention is the possibility that France, as the only nuclear power in the European Union with an independent nuclear arsenal,Footnote 12 could take on the role of nuclear guarantor for the other European partners, similar to the current arrangement within NATO and the NPG, from which several EU and NATO member countries benefit. This possibility, which is on the horizon, has already been examined by various analysts,Footnote 13 and was even suggested in a Bundestag report.Footnote 14 While it is true that most analyses focus on the concept of French extended deterrence,Footnote 15 others evoke the specific possibility of a double-key system or, at the very least, the stationing of French nuclear weapons on the territory of other European partners.Footnote 16

Before assessing whether such a system could be implemented, it is important to clarify what strategic purpose it would serve. While often framed in operational terms, the core utility of NATO’s current nuclear sharing arrangements lies in their political signalling value. As WarrenFootnote 17 notes, existing research shows that the forward deployment of nuclear weapons does not significantly enhance the deterrent effect of US security guarantees. Rather, these deployments serve primarily to reinforce alliance cohesionFootnote 18 and reassure European partners of US commitment. This suggests that a French-led dual-key system, to be politically effective, would need to prioritise symbolic credibility over technical equivalence.

This article explores the feasibility of this possibility, from a technical and political, as well as doctrinal, perspective; and analyses the strategic implications it would entail. As Europe seeks to strengthen its strategic autonomy, expanding it beyond the military realmFootnote 19 and reducing its dependence on the United States in matters of security, a France-led double-key system could represent a significant shift in European defence policy.

The analysis is structured into several key sections. First, the technical capabilities of France to assume this role are examined, including the available nuclear weapon delivery vectors, the number of nuclear warheads, and the limitations of interoperability with the armed forces of other European countries. Second, an analysis is made of the doctrinal changes that France would need to implement in order to extend its doctrine to third countries, as well as the mechanisms through which a command and coordination structure for joint nuclear forces could be created. Next, the political and defensive utility of a double-key system with France as the ‘provider’ is evaluated, along with the benefits and issues it could entail.

Finally, this article concludes by evaluating the feasibility and strategic implications of this proposal, offering a comprehensive assessment that considers both the challenges and opportunities of a shift in the nuclear deterrence system in Europe under French leadership. In doing so, it aims to contribute to the discussion on the future of European defence and security in an increasingly multipolar and complex world.

Analysis of France’s technical capabilities

The feasibility of France assuming the role of ‘nuclear provider’ in a double-key system with European countries currently under the US nuclear umbrella largely depends on its technical capabilities. Unlike the United States, which maintains a substantial arsenal of nuclear weapons deployed in European bases under this system,Footnote 20 France possesses an independent nuclear arsenalFootnote 21 developed to guarantee its own national deterrence and sovereignty,Footnote 22 as well as a significantly smaller number of warheads.Footnote 23 This analysis assesses whether the French nuclear forces, in terms of delivery systems, number of warheads, and integration capacity with the defence systems of other European countries, are sufficient and suitable for an expanded double-key system in Europe.

Delivery systems and projection capabilities

France has a nuclear force de frappe, which consists of two main components: the ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) and an airborne component. The naval component includes four Le Triomphant-class submarines, each equipped with M51 intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of carrying multiple nuclear warheads.Footnote 24 The presence of four submarines ensures that, despite the maintenance, overhaul, and patrol cycles, there is always at least one of them deployed to guarantee deterrence at all times. This provides an unbroken ability to ensure France’s nuclear deterrence, no matter the operational and maintenance demands.Footnote 25 Moreover, having this submarine component grants France a significant advantage in terms of the credibility of its deterrence, as the existence of submarines is generally considered a guarantee that the country possesses second-strike capability. This would allow France to respond to a potential preventive nuclear attack, one that could destroy a large portion of its land-based launchers through a surprise strike.Footnote 26

However, this naval deterrence component is exclusively national, as although the details of double-key agreements are classified information,Footnote 27 all of them are based on the air component. This is not only because it is easier and cheaper than having nuclear submarines, but primarily because, from a practical standpoint, it is not very feasible to establish any kind of double-authorisation mechanism on a nuclear submarine.

The air component, on the other hand, would be the other nuclear ‘pillar’ of France that could be shared under a double-key system, through the use of dual-capacity aircraft (DCA), given that France long ago renounced having a land-based nuclear component.Footnote 28 Currently, the operational DCAs in European countries that operate under NATO’s double-key system include the F-16s in Belgium and the Netherlands,Footnote 29 which will soon be replaced by the F-35A in the NetherlandsFootnote 30 and Belgium,Footnote 31 as well as the European-made Tornado in Germany,Footnote 32 which will also be replaced by the F-35,Footnote 33 As Heloïse Fayet points out, the need for dual-capacity aircraft is a ‘a good way for the United States to sell F-35s, currently the only fighters compatible with the DCA mission’.Footnote 34 All of these aircraft operate with US B61 gravity bombs,Footnote 35 which, as we will see in the following section, are technically quite inferior to the air-to-surface nuclear missiles that France possesses.

In the French case, this air component is primarily composed of Rafale fighter jets equipped with the ASMP-A (Air-Sol Moyenne Portée-Amélioré) air-to-surface nuclear missile.Footnote 36 This missile has a range of approximately 500 kilometres and can be launched from platforms such as the Rafale BF3 and Rafale MF3.Footnote 37 While the Rafale MF3 operates from aircraft carriers and can theoretically launch a nuclear strike anywhere around the globe, the land-based version, the Rafale BF3, has a range of 2,000 kilometres.Footnote 38

The air component is more flexible for use in joint operations and could, in theory, be adapted for operation under a double-key system with other European countries, much like the current practice with the US B61 bombs.Footnote 39 However, the use of such air-to-surface nuclear missiles could potentially require a series of technical modifications, as well as security adjustments at the airbases of the partner countries, as well as modifications to their aircraft. Currently, France and GreeceFootnote 40 are the only two countries in the European Union that operate the Rafale fighter jet in one of its various configurations, which could limit the practical implementation of such a system in other member states.

In this case, we would be faced with a challenge of compatibility between the vectors and carriers, given that all the dual-capacity aircraft operating under NATO’s double-key system with US sponsorship in Europe have been specifically adapted to carry the B61 gravity bomb. This bomb is currently undergoing improvements towards a more precise version with a guidance system, although it remains, by its nature, a gravity bomb.Footnote 41 On the other hand, the French nuclear air component operates with a cruise missile, which has a range of 500 kilometres. Therefore, the potential application of a hypothetical double-key system based on France would require the acquisition of Rafale aircraft by European host states, the adaptation of existing dual-capacity aircraft to the French ASMP-A missile, or the design and development of a completely new type of bomb that would be compatible with the existing DCA already in service in those countries.

Unlike the stealth-enabled F-35 aircraft, which are capable of penetrating advanced air defence systems, the Rafale–ASMP-A combination may face greater detection risks, potentially limiting its first-strike utility or its use in high-intensity, contested environments. Moreover, forward-deployed US nuclear weapons – such as the B61 – serve not only an operational function but also a powerful political signalling role, acting as a ‘tripwire’ to ensure US involvement in case of aggression. This symbolic dimension of deterrence is explicitly acknowledged in NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept, which underscores the role of forward-deployed US nuclear weapons and allied dual-capable aircraft as central to the Alliance’s nuclear posture.Footnote 42

Returning to the options outlined above, both the acquisition of Rafale aircraft by host states and the adaptation of existing dual-capacity platforms to the ASMP-A missile would involve a sensitive technology transfer of the ASMP-A missile, which Fayet considers highly improbable, given that such a transfer would result in ‘A loss of sovereignty over the only missile of France’s airborne deterrence component’,Footnote 43 or in other words, a loss of sovereignty over the only missile currently part of France’s air-based nuclear deterrent.

Each of these options would imply different budgets and costs, although in operational terms, the ASMP-A missile and its effective range of 500 kilometres have significant advantages over the mere B61 gravity bombs. The use of the latter involves a greater exposure to potential enemy anti-aircraft fire, as well as the need to directly fly over nuclear targets. This leads some analysts to consider them ineffective due to the risks associated with their deployment.Footnote 44

In addition to these operational differences, there is also a key divergence in yield flexibility and doctrinal purpose between the systems. The ASMP-A, currently France’s sole air-delivered nuclear weapon, is believed to carry a warhead with an approximate yield of 300 kilotons.Footnote 45 The newly announced US B61-13, by contrast, is expected to match the yield of the earlier B61-7 – up to 360 kilotons – while maintaining the variable-yield capabilities of the B61 family.Footnote 46 This enables the United States to employ these weapons across a wide spectrum of scenarios, including sub-kiloton ‘tactical’ strikes. In contrast, French nuclear doctrine explicitly rejects tactical nuclear use, remaining anchored in the concept of dissuasion du faible au fort and focused exclusively on strategic retaliation. This doctrinal and technical gap may reduce the functional equivalence between both systems and could limit the flexibility and credibility of a French-led dual-key arrangement modelled on the NATO framework.

However, despite the fact that all options would require either adapting or acquiring new dual-capacity aircraft, none of these seem particularly difficult to achieve in the medium term, as long as there is political will on the part of France to take on this role and the consequences it entails, in terms of both the sale of vectors and potential technology transfers.

Number of nuclear warheads, deterrence requirements, and costs

France maintains an arsenal of approximately 290 nuclear warheads,Footnote 47 which, according to French strategists, provides sufficient deterrence. This concept is similar to the British idea of minimum deterrenceFootnote 48 and it ‘also significantly limits France’s ability to establish a nuclear sharing scheme for its European allies’.Footnote 49 Indeed, if we assume that the current French arsenal is necessary to provide the minimum level of nuclear deterrence for France, it is undoubtedly clear that any expansion of this deterrence to third countries could require an increase in the existing arsenal.

On the other hand, the number of nuclear warheads currently deployed by the United States in Europe under the extended deterrence doctrine has significantly decreased compared to previous decades. According to more recent estimates, the United States maintains approximately 100 B61 nuclear bombs on European bases as part of the dual-key system,Footnote 50 a number well below the current size of the French arsenal and much inferior to the previous 480 nuclear warheads the US had in 2005.Footnote 51 This suggests that, from a purely quantitative perspective, France already possesses a nuclear force that is comparable – if not superior – to the US forward-deployed arsenal in Europe.

An important point to highlight is that ‘Nearly all of France’s warheads are deployed or operationally available for deployment on short notice’.Footnote 52 This means that, unlike other nuclear-armed countries that have a portion of their arsenal deployed while the rest is kept in reserve, lending nuclear weapons to other countries would essentially place France in a zero-sum situation: every nuclear warhead stationed on the soil of one of its European partners would be one less warhead that France’s nuclear forces would have at their disposal to carry out their current missions and to maintain the current level of deterrence.

However, given that the current US forward-deployed arsenal in Europe is estimated at only around 100 warheads,Footnote 53 the scale of this trade-off would likely be more manageable than previously assumed.

Certainly, this could be addressed in several ways. One option would be through the participation of non-nuclear European countries in the cost of the dual-key nuclear forces deployed on their territories, despite the fact that ‘France has shown ambivalence about the possibility of Germany co-financing French nuclear weapons’,Footnote 54 or alternatively, by using a significantly smaller number of nuclear warheads.

However, the latter could compromise the effective deterrence of these countries while simultaneously remaining a significant burden on the French budget. In France’s 2016 budget law, an expenditure of 5.05 billion euros was authorised;Footnote 55 although, in the French case, ‘le SNLE 3 G remains the longest – and most expensive – project for the period 2020–2030. Among the more modest programs, the period will also see the development of the M51.3 and the replacement of the Mirage squadrons by Rafale aircraft.’Footnote 56

Certainly, there could be compromises in this zero-sum game, as although nearly all of France’s nuclear warheads are deployed, not all of them would likely be used if that decision were made. Therefore, it would likely be feasible for France to allow some of them to be hosted on the territory of its European partners. However, even though this situation might be possible, it would be completely unfeasible to maintain the current European nuclear presence without expanding France’s nuclear arsenal. It is true that France has the economic capacity to increase its current arsenal by more than 250 warheads, practically matching the number provided by the United States to non-nuclear European countries, as between 1984 and 1991 France had a number of warheads close to 550.Footnote 57 This does not seem financially unfeasible today, especially considering that France’s GDP in terms of purchasing power parity is more than four times what it was in 1990.Footnote 58

However, even though this is possible, the action would clearly entail a greater investment in nuclear weapons for the French public coffers, where the weight of nuclear spending already amounts to €5.6 billionFootnote 59 compared to the total military sector expenditure for the same year of €43.9 billion,Footnote 60 which represents 12.8 per cent of the total. It is difficult to estimate, given the current data and the challenges posed by its analysis due to military secrecy,Footnote 61 what the specific costs would be for the manufacturing, transportation, and custody of new nuclear warheads and the adaptation of launch vectors to French capabilities. While it is true that a large portion of the expenses related to the dual-key system, such as the W3, are partially financed by the host countries,Footnote 62 it is equally true that the entire process would involve investments from France beyond its current nuclear budget.

In any case, it seems that, just as it is suggested that the B61 bombs have helped with the export of the F-35s,Footnote 63 it is equally possible that France could have economic returns from the export of its dual-capacity Rafale aircraft; therefore, the cost–benefit relationship of this project would not be as negative for the French public coffers as one might initially expect.

Interoperability with the defence systems of other European countries

Aside from the issue of compatibility and transition between dual-capable aircraft (the shift from F-35/F-16 to Rafale) and weapon systems (the transition from B61 to ASMP-A), one of the main technical limitations for implementing a French-led dual-key system lies in the interoperability of its nuclear forces with the defence systems of other European countries, as well as their procedures and strategies.

France organises several nuclear deterrence exercises throughout the year, such as the Poker exercises.Footnote 64 Although President Macron has called on other European partners who wish to participate in French deterrence exercises,Footnote 65 the fact is that these exercises rarely include the presence of European aircraft or units, except on very rare occasions, such as when an Italian air refuelling aircraft participated.Footnote 66 Thus, ‘France’s openness to its European partners in this domain remains undeniably more modest than NATO’s arrangements, which are intended to be collective’.Footnote 67

In fact, within NATO, there is a tradition of joint training by American and other nuclear forces, where exercises are held to practice with the aircraft involved in the dual-key system,Footnote 68 such as the Steadfast Noon exercise. In these types of exercises, even NATO allies that are not part of the dual-key system, such as Spain or Poland, participate, involving a total of fourteen countries, but with the notable absence of France.Footnote 69

As we have seen so far, French nuclear forces have operated independently from the rest of the alliance, unlike the American forces. This independence means that there would be a significant requirement for the harmonisation of doctrines, equipment, and communication systems to ensure effective interoperability under a new dual-key system. This harmonisation effort would involve training, exercises, and protocols, in addition to the acquisition or adaptation, as already discussed, of air vectors by host countries or the expansion of the number of available nuclear warheads.

Joint training would be essential to ensure that pilots from other nations can operate in combination with French vectors, and vice versa, in line with what the French president had already suggested,Footnote 70 and which constitutes a necessary first step. However, although there is still much to be done in this regard, it is equally true that the French government has already taken the necessary steps to move in this direction through the integration of other countries into French deterrence exercises, as we have seen.

Political and doctrinal implications of a French-based double-key system

In addition to the technical challenges we have already examined, the possible replacement of US leadership by France in a European nuclear double-key system raises significant changes in political and doctrinal terms. While the existing legal framework could be modified from one supplier to another with relative ease, transformations in political dynamics, strategic trust, and military doctrine represent challenges and opportunities that deserve detailed analysis. This section addresses the main implications from a political and doctrinal perspective.

The European dimension of French deterrence

First, it is important to point out that proposing a hypothesis in which France assumes the role of the United States is not foreign to France’s own nuclear doctrine. In fact, there has always been a European dimension within French nuclear doctrine, which has been present to varying degrees across different presidencies since the very beginning of its establishment as a nuclear power.Footnote 71 Thus, we can see references to this dimension in the nuclear doctrine speeches of various presidents, such as Chirac, who declared that:

Finally, our nuclear deterrence must also, as France wishes, contribute to the security of Europe. It thus participates in the overall deterrence capacity that can be exercised together by the democracies united by the collective security treaty concluded more than fifty years ago between Europe, the United States, and Canada. In any case, it is the responsibility of the President of the Republic to assess, in a given situation, the harm that would be done to our vital interests. This assessment would naturally take into account the growing solidarity among the countries of the European Union.Footnote 72

Or Sarkozy, who expressed himself in a similar vein, not only highlighting the European dimension of French nuclear doctrine but also France’s willingness to coordinate with its European allied countries in some form:

As for Europe, it is a fact that French nuclear forces, by their very existence, are a key element of its security. Any aggressor considering threatening Europe must be aware of this. Let us draw, together, all the logical consequences: I propose to engage with those of our European partners who wish it, in an open dialogue on the role of deterrence and its contribution to our common security.Footnote 73

This European dimension, which must be understood as France being willing to defend other European territories with nuclear weapons and to consider an attack against them as an attack against its vital interests, is common to all French presidents and has long been present in French nuclear doctrine.Footnote 74

However, this willingness is neither automatic nor universal. It has traditionally applied to a limited number of close allies, rather than constituting a blanket commitment to the entire European continent. The scope of what qualifies as a French ‘vital interest’ remains deliberately vague and politically flexible.

In fact, some of them, such as Mitterrand, have gone further than a hypothetical nuclear sharing agreement with a double-key system, as we analysed, and directly outlined a future European state with integrated deterrence:

And Europe? Because this question is often asked of us. Building the European Union: you already have the embryo and outline of a European force in which some countries participate. Could French nuclear power guarantee the integrity, the security of the European countries with whom we have contracted within the European Union? The question is not relevant today, but it is on people’s minds, and sometimes attempts are made to gauge the quality of our European commitment by asking: would you refuse or would you accept this? I would simply say that the very conditions of the exercise of nuclear weapons, the need for a solitary decision, by one or a few leaders of a determined country, the doctrine of defending the integrity of national territory, the definition of vital interests – all of this applies perfectly to France, but does not yet apply to Europe. Let Europe equip itself with clear notions regarding common vital interests, let it go far enough in its political consciousness to recognize that the territorial integrity of one country involves the territorial integrity of others, in short, let immense efforts and progress be made by those who intend to continue the construction of Europe, and France will accept the debate. That day has not yet come. – This is what an ardent European can tell you. We must know what we are talking about. Maybe this moment will come? I would welcome it, as it would only show that, before talking defence, we will have already succeeded in achieving the work of the century, and perhaps of two centuries: a united Europe, capable of defining and defending common interests in one movement.Footnote 75

And although Mitterrand defends, at least as a possibility and goal, this European state endowed with nuclear weapons, the truth is that he never contemplates the possibility of any kind of nuclear sharing under the strategic conditions that existed during his presidency. This is something that, as we will see later, is relevant when analysing the viability of a French extended deterrence system in Europe through a double-key system.

Creation or reactivation of a nuclear discussion forum

The current double-key system in Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Italy is backed by a set of bilateral agreements, which are generally developed within NATO and more specifically within the NPG. The first obstacle to setting up a French-based double-key system is France’s own absence from the NPG. While France collaborates on nuclear policy with other NATO members, it neither belongs to this group nor participates in its discussions and consultations, which, to date, is the forum in which doctrinal and nuclear strategy issues of the Atlantic Alliance are deliberated.Footnote 76

If in the previous section we analysed that France’s absence from the common nuclear policy of the alliance poses a problem when it comes to adapting protocols and ensuring the interoperability of the forces of different countries, in this case, we see how France’s absence from nuclear discussion forums also poses a problem when it comes to developing a common doctrine and having the necessary consultation mechanisms in case of a crisis.

The most logical and straightforward way to channel a French-based double-key system would be for France to be willing to join this nuclear planning group and assume a role similar to the one the United States has been playing. However, as we pointed out in the introduction to this article, the scenario in which France becomes the nuclear power involved in a European double-key system would arise from a perspective of the United States withdrawing from NATO and, more specifically, from the commitments they have made in Europe regarding nuclear deterrence. Therefore, it might be somewhat logical in this scenario for the appropriate forum to develop the nuclear policy debate within the framework of the European Union rather than NATO; in line with what President Macron has suggested, to create a European Security Council, for which some analysts have already developed proposals,Footnote 77 creating this body as either a specific body or, as Coelmont suggests, a specific formation of the European Council.Footnote 78

Any governance structure for a European dual-key system would likely face political resistance from some EU member states – such as Austria and Ireland – that are signatories of the TPNW and maintain strong anti-nuclear positions. As such, the system could only be viable within a ‘coalition of willing’ states, rather than as an EU-wide mechanism.

In any case, such a political framework should include, as in the case of NATO, the tools and means necessary to discuss nuclear policy.

Doctrinal changes

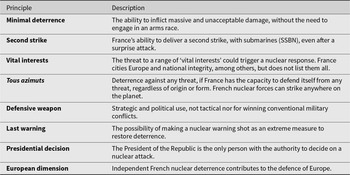

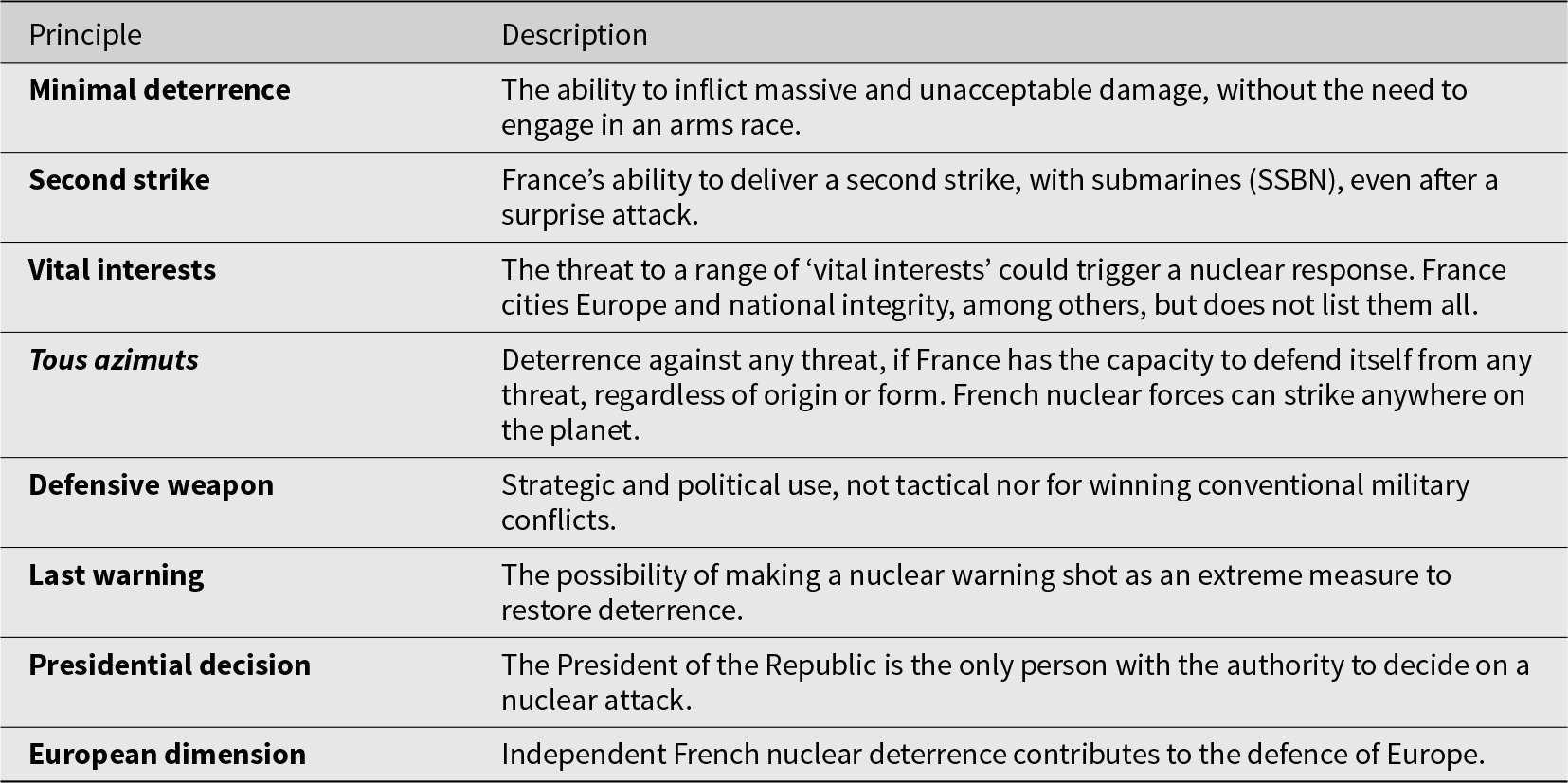

The transition to a French-led double-key system would entail significant modifications in France’s nuclear doctrine, which has historically been deeply marked by strategic autonomyFootnote 79 and the principle of minimum deterrenceFootnote 80as can be seen in Table 1. To adapt to this shared model, France would need to redefine both the strategic objectives of its nuclear arsenal and the public narrative supporting them; that is, its doctrine, understood as ‘the declared nuclear strategy of a country, which may or may not fully correspond to its effective nuclear strategy’.Footnote 81

Table 1. Key elements of France’s current nuclear doctrine.

Source: Own elaboration based on data from Tertrais.Footnote 84

Tertrais, French Nuclear Deterrence Policy, Forces and Future.

Tertrais, French Nuclear Deterrence Policy, Forces and Future.

Broadly speaking, French nuclear doctrine consists of a series of elements that have been part of it since its creation. Thus, we can observe the principle of minimum deterrence;Footnote 82 that is, France does not seek to participate in an arms race to be among the largest arsenals in the world, but rather aims to have a sufficient number of nuclear weapons to fulfil its strategic objectives. The concept of a second strike is also fundamental, meaning that France has the capability to deliver a nuclear response to any attack, even one that comes as a surprise,Footnote 83 largely thanks to the use of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines.

A crucial change would be the expansion of the geographical scope; even during Mitterrand’s time, territorial integrity was identified as one of the key vital interests.Footnote 85 But we would also be facing a political change in French deterrence. As we have seen, this change would require an increase in the number of warheads and vectors. Until now, France’s nuclear doctrine has focused solely on defending its vital interests, which specifically included the territorial integrity of France,Footnote 86 but also, in a more vague manner, the entire European continent.Footnote 87 The adoption of a double-key system would explicitly mean recognising that French nuclear weapons are also meant to ensure the security of European allies, covering them not only through extended deterrence but also by deploying nuclear weapons ready to be launched by DCA aircraft.

Thus, the adoption of extended deterrence inevitably leads to the question of whether France can have two distinct nuclear doctrines: one for its allies, coordinated with them, and that only considers the territory of those states as its vital interest, and another for itself, with the forces and weapons that are specifically its own, in terms similar to those that are currently in place. At present, the French doctrine defines use scenarios strictly related to the defence of its vital interests, interests that are not explicitly detailed and are necessarily vague,Footnote 88 but it does enumerate a few, such as territory, population, and sovereignty.Footnote 89 In a double-key context, it would be necessary to modify the approach to European defence to include the protection of specific allies, framing their defence not as part of France’s own ‘vital interest’, but within the agreements and pacts reached.

In fact, at this point, it is important to note that France does not perceive its contribution to the defence of the European continent as a debt, a pact, or a binding obligation with its partners, but as its own vital interest. Thus, France’s defence of Europe is a matter of survival, as can be seen from analysing various presidential speeches.Footnote 90

One of the elements that must be clarified, as we have previously pointed out, is how consultations and joint decisions would be carried out in crisis scenarios, establishing procedures that maintain a balance between the shared responsibility of the parties involved and operational effectiveness, which requires quick decision-making.Footnote 91 This transition also presents challenges in terms of strategic autonomy, because France, which has always tied its nuclear policy to the idea of sovereignty,Footnote 92 would need to adapt to a multinational collaboration model that could involve changes in the unilateral decision-making capacity of the President of the Republic, as has been suggested,Footnote 93 since the double-key system is the only exception to the general rule of unilateral presidential decision-making.Footnote 94

At the same time, and beyond the final decision on the use of nuclear weapons, the countries participating in the double-key system would likely demand a greater role in the operational and strategic decisions, a matter that could potentially conflict with the traditional opacity that characterises the French nuclear decision-making process, which has primarily been based on presidential autonomy.Footnote 95 Furthermore, the public narrative that has supported France’s nuclear policy would also need to evolve. Until now, France has presented its nuclear arsenal as a central element of its national sovereignty, firmly embedded in the concept of independence. However, within the framework of a double-key system, this narrative would need to be redefined in order to emphasise the role of nuclear weapons as not only a tool for national defence but also a collective asset for European security, while still safeguarding France’s strategic independence. This shift could lead us to a situation where two distinct doctrines are applied to a single arsenal, akin to the approach taken by the United States with its nuclear arsenal. The US employs different nuclear strategies depending on the geographical context and the alliances involved. For example, Washington maintains a specific nuclear doctrine for Europe within the framework of NATO,Footnote 96 focused on deterring and collectively responding to any threat against NATO members. Conversely, the US also has independent policies for the protection of its allies in other regions, such as Japan or South Korea, where the use of nuclear weapons would not be subject to the same considerations, nor would it involve NATO. This approach aligns with what the US Nuclear Posture ReviewFootnote 97 refers to as ‘Tailored Nuclear Deterrence’.

However, even if the countries currently operating under the double-key system accepted French leadership, there would be doctrinal elements of France’s nuclear doctrine that could prove controversial. For instance, ‘the right to use a final warning for deterrence’,Footnote 98 makes the French doctrine one of the most aggressive among existing doctrines, as it explicitly contemplates the possibility of a first nuclear use. This could be problematic for other European countries, particularly if such a first use were to occur from their own territory. Even if a first use did not take place, the potential for it could provoke a response from a potential adversary against the French nuclear forces stationed on their territory.

In summary, the French doctrinal shift from national deterrence to extended deterrence is not just a change in the territory covered by the ‘nuclear umbrella’ but would also have implications for elements that have always been part of the French nuclear doctrine, such as the ‘warning shot’, the decision-making method, the number of weapons required, and the very definition of new ‘vital interests’. These changes represent relatively profound adjustments to a doctrine that has largely remained stable over time.

Would the double-key system work? Would it be effective as a deterrent?

When we analyse the political and defensive utility of the double-key system, it is clear that there are several voices arguing that the double-key system is an important tool in maintaining deterrence in Europe.Footnote 99 Some even suggest its application in other regions, such as the Scandinavian Peninsula.Footnote 100

Moreover, while it is indeed true that the fact that the system would be French-based might appear much more credible to European partners compared to one based on the United States, especially given that France shares a common geographical space, proximity,Footnote 101 and similar strategic interests with its fellow European countries, such a system would still face the same fundamental credibility challenges that any extended deterrence system typically encounters. In other words, while France could offer substantial security guarantees to the entire European Union, the ultimate control over the nuclear weapons, as well as the final authorisation for their potential use, would, in all circumstances, remain firmly in French hands, raising questions about the degree of trust that European allies would place in such an arrangement.

The effectiveness of this umbrella would be heavily compromised as long as French nuclear weapons remain under French control and not under a centralised European authority, such as the European Commission or a European-led military command. While the creation of such a supranational authority would likely represent the most credible and politically balanced framework, it is worth noting that US nuclear weapons deployed in Europe are also kept under exclusive American control, with NATO functioning primarily as a consultative and coordinating structure. In that sense, national control is not unique to the French case, but rather inherent to the current NATO model.

This would give rise to credibility issues, as the French nuclear arsenal was developed precisely under the belief that the protection offered by the American nuclear umbrella was insufficiently credible.Footnote 102 Furthermore, French deterrence might be perceived as less credible when the threat occurs farther from French borders. This proximity is a key factor in the decision-making process when it comes to the deployment of nuclear assets. As TertraisFootnote 103 puts it, the idea of France committing to defend distant territories like Finland or Estonia may seem just as unrealistic as it did for the United States during the Cold War when they were tasked with the defence of cities like Hamburg or Berlin. In this sense, France might prioritise its national security and strategic interests over those of other European nations, questioning whether it would consider an attack on a distant member state worthy of its full nuclear response. This disparity in perceived threat proximity could ultimately undermine the credibility of a French-led extended deterrence umbrella for Europe.

Aside from the potential debate regarding the credibility of the nuclear sharing system and its application within the European Union, it is important to note that the double-key system, in which joint authorisation from two countries is required for the use of nuclear weapons, raises several questions about its effectiveness as a deterrent, especially when compared to the highly centralised structure of French nuclear deterrence.

In the current French model, decision-making related to nuclear deterrence is concentrated in a small number of key figures, headed by the President of the Republic, who holds exclusive control over the nuclear codes. Alongside the President, the Prime Minister, the Minister of Defence, and senior military leaders, such as the CEMA (Chief of the Defence Staff) and the CEMP (Chief of the Presidential Military Staff), are involved, supported by the Division of Nuclear Forces of the Defence Staff (EMA/FN).Footnote 104

Additionally, the Nuclear Arms Council functions as a key consultative body within the National Defence and Security Council, responsible for overseeing strategic decisions regarding the nuclear arsenal.Footnote 105 This structure ensures speed and efficiency in decision-making, which are essential for maintaining the credibility of French deterrence. Therefore, the centralisation of control in a limited number of actors is seen as a crucial pillar to ensure the effectiveness of deterrence, as it eliminates the possibility of delays or internal divisions during times of crisis.

As TertraisFootnote 106 explains, ‘The fact that deterrence ultimately relies on a single individual – elected by direct universal suffrage – is seen as an element of the credibility of deterrence’. The concentration of power in one person ensures a clear and rapid chain of command, which is crucial in emergency situations where reaction times can determine the success or failure of the deterrent strategy.

The double-key system, in contrast, introduces greater complexity in decision-making, as control over nuclear weapons would be divided between France and another country. This model raises several questions about the speed and effectiveness of the response to an imminent threat. In scenarios where quick action is required to maintain the credibility of deterrence, the need to obtain approval from multiple actors could lead to significant delays, weakening the power of collective deterrence in Europe.

The double-key system could introduce elements of uncertainty, not only in the decision-making process, which is not necessarily negative, since ‘in reality, ambiguity and uncertainty play a key role in nuclear strategies and thus contribute to incomplete information’.Footnote 107 However, this uncertainty could also affect the political cohesion between the involved allies. The possibility that one of the countries might refuse to authorise the use of nuclear weapons could erode the credibility of deterrence, giving adversaries the impression of cracks or indecision in the collective stance. Unlike the French doctrine, where the decision lies solely with the President, a double-key system requires consensus among the participating countries, which would inevitably prolong reaction times by requiring negotiations and consultations. This could be seen as a vulnerability in an international security environment characterised by the need for quick decision-making. In this context, nuclear weapons under a double-key system would play a more symbolic or political role than one that is strictly deterrent.

Conclusions

The analysis of the possibility of France taking on the role of nuclear provider in the European ‘dual-key’ system, instead of the United States, unveils a complex scenario that encompasses a wide range of technical, legal, political, and strategic challenges. While this approach could serve as a potential response to the possible withdrawal of the United States from Europe and contribute to greater European strategic autonomy, the implementation of a ‘dual-key’ system led by France would face significant obstacles on various fronts. These challenges are not just logistical or technical, but they also touch upon deeply rooted geopolitical dynamics, strategic interests, and the broader security architecture of Europe.

From a technical perspective, France certainly has the capacity to maintain a ‘dual-key’ system with its European allies, particularly through its nuclear air component. However, the limited number of French nuclear warheads and the necessity to adapt its nuclear vectors to the armed forces of other European countries would require extensive logistical and operational coordination. Furthermore, this would likely involve the production of new nuclear warheads, given that France is already operating within a framework of minimum deterrence.Footnote 108 This situation is not entirely unfeasible, as the target figure of around 600 warheads was previously achieved by France when its economic situation was less robust.Footnote 109

In addition to this, integrating the nuclear doctrines of European countries and conducting joint military exercises, as France has already proposed,Footnote 110 would be crucial to ensuring the interoperability and effectiveness of such a system. This would likely involve adapting existing DCA systems or exporting French Rafales and ASMP-A missiles to European partners, which is also technically feasible and would be key in creating a unified deterrence system.

From a legal-political perspective, establishing a French-based ‘dual-key’ system does not seem to require extensive legal reforms or additional political agreements beyond those that might already exist between the interested states and the French Republic. However, it would be essential to analyse whether this new system could be integrated into the existing NATO infrastructure, which appears highly unlikely, given that France has chosen not to participate in the NPG. Alternatively, the system could be funnelled into an ad hoc infrastructure or within the European Union through a European Defence Council, which would provide an institutional framework to manage the system.

The creation of a new command and control chain under a French-led system is not vastly different from the existing systems currently used by countries participating in the American dual-key system. Of course, there are specific characteristics of the dual-key system that make it less operational in terms of reaction speed, decision-making efficiency, and, ultimately, the credibility of deterrence. Unlike a system in which there is a single decision centre where decisions can be made in a matter of minutes, a dual-key system would require consensus between two countries, which inherently slows down response times. However, despite these challenges, there is nothing intrinsically in a French-based dual-key system that suggests it would be less effective than an American-based system. In fact, it could prove to be more effective, as it would align more closely with European strategic priorities.

The political benefits of implementing this system, if it were to be adopted in the future, are particularly noteworthy. Firstly, it would significantly strengthen European integration and strategic autonomy, making the entire group of European countries – and specifically those countries that would host these systems – less dependent on the United States and the potential fluctuations in US international policy. However, this shift could also generate a new form of dependency – this time in France. Concentrating nuclear responsibilities in the hands of a single European state could raise concerns about strategic asymmetry and the legitimacy of such leadership within the broader European defence framework. On the other hand, the French-based dual-key system would serve as a unique compromise between the two extremes that French nuclear doctrine has oscillated between in recent decades. Specifically, it would reconcile the need to preserve France’s decision-making autonomy over its nuclear weapons with the understanding that France is an integral part of European integration, has interests in its allied states, and is connected to their fate. The dual-key system would allow France to ‘share’ deterrence without ‘sharing’ the weapons themselves, maintaining its autonomy in decision-making while offering a form of nuclear ‘umbrella’ to its European partners – an umbrella that, as we have seen, could be quantitatively similar to the one the United States has historically provided.

One of the most critical challenges of a French-led dual-key system lies in the fundamental issue of credibility. While France possesses a fully independent nuclear arsenal and has demonstrated its long-term commitment to maintaining a credible deterrent, the effectiveness of an extended nuclear umbrella depends on not only capabilities but also the perceived willingness to use them in defence of others. Historically, France developed its nuclear arsenal precisely because it viewed the American nuclear umbrella as insufficiently credible.Footnote 111 This raises an important paradox: if France itself doubted the reliability of US extended deterrence, why would European allies – especially those further from French territory – place full trust in a French nuclear guarantee?

Furthermore, the credibility of such a system would be influenced by France’s strategic calculus. French nuclear doctrine has been primarily centred on the protection of French sovereignty and vital interests, and while recent statements suggest a greater openness to European security considerations, this does not necessarily translate into a firm commitment to defend any European country as if it were France itself. As TertraisFootnote 112 points out, France’s willingness to resort to nuclear escalation decreases as the threat moves further from its borders. This geographic and strategic limitation could generate concerns among European partners, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, where the perceived threat from Russia is most acute. If France hesitated to fully embrace the idea of an extended American deterrent during the Cold War, it is unlikely that nations like the Baltic states or Nordic countries would find a French-led dual-key system more credible than the existing US framework.

This issue is further compounded by the structure of a dual-key system itself, which inherently adds layers of decision-making complexity. Unlike a centralised nuclear command, where a single authority can take swift action, a dual-key arrangement requires consensus between France and the host country, potentially delaying response times in a crisis scenario. Given that nuclear deterrence relies heavily on the adversary’s belief in an immediate and decisive response, any hesitation or ambiguity in the decision-making chain could undermine the very purpose of the system.

Ultimately, while it is technically possible to implement a French-led dual-key nuclear system, its viability will depend on a range of interconnected factors. These include the political willingness of European countries to redefine their collective security frameworks, France’s ability to lead in an inclusive and cooperative manner, and NATO’s ability to integrate this new system into its defence strategy without compromising the cohesion of the Alliance. The transition towards a more European-led nuclear deterrence system represents a strategic opportunity, but it also demands a significant political and diplomatic commitment to overcome the numerous challenges it presents. This is a complex issue, and although it offers potential benefits in terms of autonomy and political integration, it also poses substantial risks that must be carefully weighed.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. A preliminary version of this article was presented at the 2025 biennial conference of the Association pour les études sur la guerre et la stratégie (AEGES) in Aix-en-Provence. The author is grateful to AEGES for providing a stimulating academic forum that supports ongoing research on war and strategy.

Nicolás Bardio is Adjunct Professor, at the Complutense University of Madrid. His current research focuses on nuclear doctrines in Europe, with particular emphasis on French nuclear policy and the integration of deterrence strategies within the context of European security.