Introduction

In 1960, the Permanent Committee for the Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise invited former US attorney general Francis Biddle to deliver a series of three lectures on Holmes’s jurisprudence at the University of Texas.Footnote 1 Though the Holmes Devise is now known for its publication of the multivolume Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States, it initially sponsored a series of high-profile lectures on Holmes’s jurisprudence. In his inaugural Holmes Devise lectures, Biddle—a former law clerk to Holmes and long-time personal friend of the Holmes family—attempted to repair the damage that Holmes’s otherwise lionized legacy had suffered at the hands of his posthumous critics, many of who rebuked the late Supreme Court justice for the perceived absence of moral foundations in his jurisprudence.Footnote 2 Biddle’s first and last lectures therefore attempted to make Holmes’s legal insights available to a “general audience,” but his second lecture had a far more critical focus.Footnote 3 As one reviewer wrote, this second lecture “[took] up the sword” to do “battle” with “crusading fanatics” who had criticized Holmes.Footnote 4 Quite remarkably, these “crusading fanatics” were three relatively little-known Catholic priests: John C. Ford, William J. Kenealy, and Francis E. Lucey.

Aside from the mere fact of their membership in the Society of Jesus—the world’s largest Catholic religious order, known widely as the Jesuits—Ford, Kenealy, and Lucey shared notable biographical similarities.Footnote 5 All three were born in Massachusetts between 1890 and 1905, graduated from Boston College High School, and joined the Society of Jesus in their youth. True to the standardized process of Jesuit formation, all three received graduate degrees in philosophy and theology from Jesuit seminaries: Lucey from Woodstock College (Maryland), and Ford and Kenealy from Weston College (Massachusetts) and the Pontifical Gregorian University (Rome). Perhaps most importantly, all three also earned degrees in American law from either Boston College or Georgetown University, both of which were (and remain) affiliated with the Society of Jesus.

While Ford’s principal professional accomplishments were in the field of moral theology, he, Lucey, and Kenealy were all involved in what has been perceptively described as the “forgotten jurisprudential debate.”Footnote 6 Conducted in the pages of academic journals and in the halls of academic conferences and law schools, this debate concerned the replacement of natural law jurisprudence with positivist methods of legal reasoning emphasizing the law’s relationship to social conditions. As Stuart Banner has recently argued, the basic thrust of these new methods was that “general legal principles [should] be ascertained purely by induction from examining court opinions,” thus establishing the boundary of judicial decision-making at the corners of enacted legal texts.Footnote 7 In Banner’s telling, this positivist and inductive move was a “response to the decline of natural law” at the end of the nineteenth century that “eventually bec[a]me the conventional way lawyers think about the legal system.”Footnote 8

This positivist and inductive way of thinking about the legal system was initially associated with the legal science of Harvard Law School’s Christopher Columbus Langdell.Footnote 9 By the 1920s, however, it also served as the foundation for the emergence of legal realism. Proponents of legal realism often articulated many unique (and sometimes conflicting) jurisprudential theories, but those most deeply objectionable to twentieth-century Catholic legal scholars brought the positivist and inductive features of Langdellian legal science to an extreme in further arguing that “empirical studies provide[] the only means to foundational knowledge.”Footnote 10 In one scholar’s formulation, this empiricism was the distinguishing feature of legal realists’ response to the “problem of foundations” produced by the “interrelated decline of natural law and rise of positivism” at the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 11

Though the contours of legal realism and the identification of its leading exponents has been the subject of significant historical debate, it nevertheless remains true that twentieth-century Catholic legal scholars took as the object of their critique many in the elite legal academy who were convicted by a belief that “the law had come to be out of touch with reality,” at least in part because “natural law was a figment of philosophers’ imaginations.”Footnote 12 To these legal realists, “applying the methods and tools of empirical social science to law” appeared to offer a more descriptively accurate understanding of the law and a more normatively desirable foundation upon which judges could “balance the competing interests present in every lawsuit so as to maximize the public good.”Footnote 13

Like other twentieth-century Catholic legal scholars, Ford, Kenealy, and Lucey responded to the decline of natural law in American jurisprudence by invoking the natural law philosophy of Thomas Aquinas and his sixteenth-century (Scholastic) and nineteenth-century (neoscholastic) disciples.Footnote 14 In so doing, they argued that legal realism irredeemably divorced law and morality and thereby inaugurated what I term the neoscholastic legal revival, a decades-long period of debate between Catholic natural lawyers and their positivist contemporaries about natural law’s foundational relationship to the American legal tradition.

The origins of the neoscholastic legal revival are evident in particular features of nineteenth-century European Catholic intellectual culture that were transmitted to the United States through the Society of Jesus. American Jesuits were not alone in advancing the revival’s aims, but they and their educational institutions exerted a decisive influence on the revival, thus explaining why Biddle specifically chose to rebuke three Jesuits in his inaugural Holmes Devise lectures.Footnote 15 By examining the decades-long process of intellectual formation that William Kenealy, the dean of the Boston College Law School, and Francis Lucey, the regent of the Georgetown University Law Center, underwent, it is especially clear why leaders of the neoscholastic legal revival sought so fervently to pursue the revival’s goal of harmonizing natural law and American positive law. And in this way, the lives and legacies of Kenealy and Lucey illustrate how recovering the revival’s forgotten history can enrich scholars’ understanding of this important period in American legal history.

The European Origins of American Neo-scholasticism

The neoscholastic legal revival began in the 1920s as legal realism emerged as a powerful force in elite legal education. In 1925, for example, Walter B. Kennedy—a legal scholar at the Jesuit-run Fordham University who had earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees at the Jesuit-run College of the Holy Cross—published an influential article in the Marquette Law Review (a journal associated with the Jesuit-run Marquette University) that critiqued the positivism of Ivy League legal scholars.Footnote 16 According to Kennedy, Harvard’s Roscoe Pound and his intellectual acolytes viewed the law as a “conglomeration of dry-as-dust precedents” in need of judicial revision to meet present-day social needs.Footnote 17 Critiquing Pound, Kennedy argued that “the shape of permanent constitutional principles and natural rights” was obscured by “the hurricane of social wants and demands” once one accepted Pound’s positivist theory of the nature of law.Footnote 18 As such, Kennedy and proponents of the neoscholastic legal revival thereafter exhorted American legal scholars to reject legal realism’s morally vacuous positivism and instead return to a “natural-right[s]” philosophy that “blends” positive law with the “stable principles of the natural order.”Footnote 19

Kennedy was unique among participants in the neoscholastic legal revival in the sense that he began writing against legal realism in the early 1920s, and not in the 1940s and 1950s, when many of the most (in)famous critiques of legal realism were published. (If the articles that Biddle sought copies of before preparing his Holmes Devise lectures are any indication, the revival reached its climax during the Second World War and in the immediate postwar period.)Footnote 20 Kennedy was not unique, however, in having received his intellectual formation at one of the Society of Jesus’s many American educational institutions—in which, during the first half of the twentieth century, neoscholastic philosophy was especially prominent. To understand how Catholic legal scholars like Kennedy became participants in the twentieth-century American neoscholastic legal revival, one must therefore first account for the nineteenth-century forces on both sides of the Atlantic that brought neo-scholasticism into the institutions in which Kennedy and his contemporaries were intellectually formed.

In 1869, Pope Pius IX convened the First Vatican Council in Rome to respond to issues of religious teaching authority raised by the “cultural, political, and religious crisis ignited by the French Revolution and its pan-European Napoleonic aftermath.”Footnote 21 In its landmark Dogmatic Constitution of the Church of Christ, Pastor Aeternus, the council declared that the pope, under certain circumstances, possesses the “infallibility that the divine Redeemer willed his Church to enjoy in defining doctrine concerning faith or morals.”Footnote 22 As John O’Malley has observed, this declaration of infallibility was the “core” of a nineteenth-century Catholic movement known as ultramontanism, a movement that takes its name from the Latin ultramontanus, signifying one’s looking beyond the mountains, toward Rome.Footnote 23

The nineteenth-century turn toward Rome that ultramontanism precipitated reached a pinnacle at the First Vatican Council, known popularly as Vatican I. At this landmark ecumenical council, two related facets of Catholic theology—papal primacy (preeminence in governing) and papal infallibility (preeminence in teaching)—were expressed as central to Catholic Christianity. In fact, the first chapter of Pastor Aeternus specifically declared that the pope has “primacy of jurisdiction over the whole Church of God” that was “immediately and directly promised to the blessed apostle Peter and conferred on him by Christ the Lord.”Footnote 24 Likewise, the council remarked in Pastor Aeternus that the pope, “by the divine right of his primacy, governs the whole Church.”Footnote 25 As evidenced by these two brief excerpts, Pastor Aeternus positioned the pope to exercise singular control over the church’s internal governance.

Alongside papal primacy, the council’s decision to emphasize papal infallibility appeared to be the only way for the Catholic Church to effectively respond to the social, cultural, and intellectual confusion prompted by Enlightenment rationalism.Footnote 26 In O’Malley’s telling, post-Enlightenment biblical criticism and bourgeois “demands” for freedoms of speech, press, and religion seemed to represent a crisis of authority that “challenged the very foundations upon which church and society had rested since time immemorial.”Footnote 27 For this reason, Vatican I presented the Catholic Church as a divinely sanctioned teacher that could remedy the ills of modernity through the authority vested in the pope.Footnote 28 Having firmly defended the pope’s preeminence in teaching and governance, the council thus offered the Holy See a uniquely centralized set of theological and institutional resources that could be employed to dictate the specific mode of the Catholic Church’s post-conciliar ministry.

As Oliver Rafferty has illustrated, the Vatican I-era church was decisively shaped by the thought of Thomas Aquinas and his neoscholastic intellectual disciples. The council’s Constitution on Faith, Dei Filius, for example, advanced a theory of the “relationship between faith and reason” that was inextricable from a more general “return to [the] Scholastic method manifested at Vatican I.”Footnote 29 As O’Malley has similarly noted, Catholic intellectual culture during and immediately after the council was oriented around the “Aristotelian system that had undergirded Catholic theology since the thirteenth century.”Footnote 30 Importantly, this was the system that Aquinas famously re-articulated in his Summa Theologiae.

Although there were many influences on the bishops who convened in Rome for the First Vatican Council, few were as decisive in informing the Catholic Church’s post-conciliar philosophical neo-scholasticism as the Society of Jesus. Under the leadership of Jesuit superior general Pieter Jan Beckx—a Belgian priest known for his neoscholastic sympathies—in fact, the Society of Jesus was one of the leading proponents of recovering Aquinas’s thought to confront modern challenges. For instance, the authors of Dei Filius were two prominent Jesuits, Johannes Franzelin and Joseph Kleutgen, and the leading Vatican periodical La Civiltà Cattolica was managed at this time by “all the main Italian Jesuit neo-Scholastics.”Footnote 31 During the pontificate of Pius IX (1846–1878), these neoscholastic emphases within the Society of Jesus began to re-shape European Catholic intellectual culture more broadly, a trend that would culminate in the pontificate of Pius’s successor, Leo XIII (1878–1903). Leveraging the aura of authority that the First Vatican Council ascribed to the papacy under Pius, Leo made neo-scholasticism the defining characteristic of the church’s post-conciliar philosophical methods.

When Leo was elected pope in 1878, he became a conduit for the Society of Jesus’s “programmatic assault” on the deleterious intellectual currents that had prompted calls for the First Vatican Council years earlier.Footnote 32 Though it was certainly true that the Jesuits had come to a position of increased prominence during Pius’s pontificate, Leo’s pontificate was marked by even greater Jesuit influence on the church. In one respect, this greater influence can be attributed to the confluence of unique biographical circumstances that had acquainted Leo with the Society of Jesus: he was educated by the Jesuits during his seminary formation, and his brother, Giuseppe, also became a Jesuit.Footnote 33 Moreover, the Jesuits had begun to forge increasingly close ties with the papacy even before Leo’s election for fear of being suppressed by the Holy See (as the Society had been in 1773).

One of Leo’s first administrative decisions as pope was to replace Roman seminarians’ philosophy textbooks “with respected manuals of [Aquinas’s philosophy].”Footnote 34 This decision prefigured a salient theme during Leo’s pontificate, one that would be most cogently articulated in his 1879 Encyclical on the Restoration of Christian Philosophy, Aeterni Patris—namely, the desire to make Aquinas the foundation of the Catholic Church’s response to modernity. Benefiting from the particularly decisive governance authorities afforded to the Holy See by the First Vatican Council, Leo and his Jesuit contemporaries, in the words of one observer, made neo-scholasticism triumph over its rival philosophical methods by an “unscrupulously brutal use of [clerical] authority.”Footnote 35

Leo shaped this period’s distinctly neoscholastic “education of the Catholic clergy” by leveraging the governance authorities ascribed to the papacy by the First Vatican Council.Footnote 36 For example, Leo expressly directed the Jesuit-run Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome to lead the revival of Aquinas’s method, even personally arranging that certain individuals be responsible for the Gregorian’s philosophical curriculum.Footnote 37 In the words of Charles Curran, the Jesuits who came to “gain[] control” of the Gregorian during Leo’s pontificate became “the spearhead of [Aquinas’s] revival … in the form of neo-scholasticism.”Footnote 38 The impact of these reforms was so substantial that two decades after Leo’s promulgation of neo-scholasticism’s “magna charta,” Aeterni Patris, one Cincinnati-based Catholic newspaper published a front-page story on the training of clergy that discussed how Aquinas’s Summa was the “book par excellence, from which the seminarians … study Scholastic[ism] most profitably.”Footnote 39

These features of nineteenth-century European Catholicism had a somewhat paradoxical effect on the Catholic Church in the United States. On the one hand, the increasingly Rome-centric Catholicism that the First Vatican Council endorsed lent further credence to American Protestants’ fears about a turn-of-the-century influx of foreign immigrants who came to the United States not only impoverished, but also with a non-American (if not anti-American) faith. As Elizabeth Fenton and Timothy Verhoeven have argued, the First Vatican Council’s declaration on papal infallibility precipitated poignant claims that the Catholic Church was championing a deeply anti-American “power to silence” dissenters.Footnote 40 Likewise, Marc Stern has demonstrated that Vatican I’s declaration on papal infallibility “gave rise to a generalized fear of an anti-democratic, autocratic Catholic Church which was seeking political power everywhere.”Footnote 41 On the other hand, however, the neoscholastic currents that so shaped Vatican I also appeared to offer an intellectual medium for American Catholics’ reconciliation with non-Catholics during the twentieth century.Footnote 42 John Courtney Murray, for instance, frequently appealed to natural law in his well-documented attempts to articulate how Catholics could, in fact, be Americans before John F. Kennedy’s election as the nation’s first Catholic president.Footnote 43

While the bishops at Vatican I likely did not envision the long-term effects of their focus on an increasingly Roman and neoscholastic Catholicism, it was during Leo’s pontificate that neoscholastic philosophical methods came to permanently shape the institutions responsible for training an entire generation of American Jesuits born at the turn of the twentieth century. Aside from the fact that this generation included Ford, Lucey, and Kenealy—who would themselves become leaders of the neoscholastic legal revival—other Jesuits educated in the neoscholastic mold of the nineteenth-century Catholic Church later assumed important posts in US educational institutions that positioned them to contribute to the legal revival too. After receiving his doctorate from the Pontifical Gregorian University, for example, the Jesuit Robert Ignatius Gannon taught philosophy at Fordham and was named to its presidency in 1936.Footnote 44 By virtue of this latter position, Gannon was invited to deliver the sermon at the 1942 New York City Red Mass—a high-profile Catholic liturgy for lawyers—that was published in the Fordham Law Review. Footnote 45 In this sermon, Gannon repeated many of the neoscholastic legal revival’s standard refrains about how rejecting natural law philosophy necessarily requires divorcing law and morality, thereby imperiling the American legal tradition’s legitimacy. Despite the fact that Gannon is just one example, countless other Jesuits of this turn-of-the-century generation likewise taught students—such as Walter Kennedy—at Jesuit colleges and universities in the United States (of which, by 1920, there were nearly forty).Footnote 46

The origins of the twentieth-century neoscholastic legal revival were in Vatican I-era features of European Catholic intellectual culture that were transmitted to the United States through the Society of Jesus. Thus, while John Tracy Ellis may have been right to once assert that most Americans intellectuals of the late nineteenth century viewed the “study of Scholastic philosophy” as “sadly out of date,” the evidence nevertheless reveals that twentieth-century legal scholars successfully used nineteenth-century neoscholastic resources to articulate an influential strand of natural law jurisprudence in the United States.Footnote 47

New Students, Old Models: William J. Kenealy’s Religious Formation

William J. Kenealy was born in July 1904 to Mary Agnes Fay and William Edward Kenealy, roughly one year after their marriage at Boston’s Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Church.Footnote 48 In Kenealy’s telling, he came from “a long and distinguished line of unsuccessful Irish horse-thieves,” a tongue-in-cheek description of his humble Anglo-Irish ancestry: his father was an immigrant from England and his mother seems to have been born in the early 1870s to one of the Irish-Catholic families who “flood[ed]” into Boston during the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 49

Time has rendered obscure much of Kenealy’s life before he entered the Society of Jesus in August 1922, one month after his eighteenth birthday.Footnote 50 Based on the extant evidence, however, he and his siblings appear to have been raised in Roxbury, Massachusetts, where he worked as a shoe shine, a plate factory employee, and a drug-store clerk.Footnote 51 In light of his family’s background, it is likely that Kenealy had a childhood quite typical of Boston Catholics of the period. Indeed, one of his siblings, Helen Elizabeth Clare, joined the Sisters of Saint Joseph and taught alongside other women religious in Boston’s Catholic schools.Footnote 52 Kenealy’s father was an active member of the Knights of Columbus, a popular organization for lay Catholics, and also served for a time as vice president of the Society of Jesus’s Saint Ignatius Guild.Footnote 53 Joseph Dooley, Kenealy’s only cousin surviving at the time of his death, was similarly ordained as a Jesuit priest in his youth.Footnote 54 And like his brother, Joseph, William Kenealy was educated in the incipient system of Catholic educational institutions that remain a defining feature of American Catholicism today. In many ways, the stories of these institutions are also the stories of Kenealy’s formative years as a Jesuit-in-training, and therefore of the neoscholastic legal revival that he would later help to lead.

Kenealy’s religious formation began after his profession of first vows at the Jesuit house of studies in Yonkers, New York, in August 1922.Footnote 55 Due to a confluence of administrative decisions, however, Kenealy and his fellow Jesuit novices relocated from Yonkers to Lenox, Massachusetts, in June of the following year.Footnote 56 During this period, Kenealy was placed under the spiritual direction of J. Harding Fisher, the Jesuit “novice master” known for his ascetic personality.Footnote 57 Likewise, Kenealy’s early years as a novice would have been significantly influenced by the Jesuit Thomas Campbell, a “most outstanding [and] awesome figure” who was nevertheless described by some as “dour” and having a “jansenistic” attitude—a reference to the seventeenth-century French Catholic movement whose members typically “[ceased] all secular activity” and engaged in an “ascetic retreat from the world.”Footnote 58

After two years in the novitiate—the period during which Jesuits learn to master the spirituality of the Society of Jesus’s founder, Ignatius of Loyola—Kenealy became a junior, the term used to identify young men in the second stage of their Jesuit formation.Footnote 59 According to The Making of a Jesuit Priest, an early twentieth-century pamphlet on Jesuit formation for lay readers, juniors were to have a “burning thirst for knowledge,” not least because it was during their time as juniors that Jesuits were meant to recognize that scholarly learning “is a part of [their] professional life equipment.”Footnote 60 With the “two-edged sword of tongue and pen,” juniors were tasked with learning how to “promote God’s glory, to widen the influence of the Church, and to slay heresy outright.”Footnote 61

Even before beginning his academic studies in philosophy during the third phase of his Jesuit formation, Kenealy was likely exposed to neo-scholasticism through the largely spiritual training of the novitiate and juniorate. As John O’Malley once observed in his autobiographical reflections on mid-twentieth-century Jesuit formation, August Coeman’s Commentary on the Rules of the Society of Jesus, a spiritual guide for Jesuit novices, was marked by “Neo-Scholastic” presuppositions and “reflect[ed] Catholic intellectual culture of the [late 1930s].”Footnote 62 Kenealy’s time as a novice and junior pre-dated the publication of Coeman’s Commentary by a full decade, thus emphasizing the fact of his early spiritual training having been undertaken amidst a period of substantial neoscholastic influence within the Society of Jesus. Further evidence of neo-scholasticism’s influence on juniors’ formation during the early twentieth century can also be identified in the exams required for juniors’ graduation. Given the close relationship between neo-scholasticism and nineteenth-century ultramontanism, it should come as no surprise, for instance, that a Jesuit in the juniorate in 1919 would have been required to defend the thesis that the pope enjoyed “in primatu jurisdictionis universalis super Ecclesiam a Christio fundatam” (primacy of universal jurisdiction over the Church founded by Christ) before graduation.Footnote 63

After four years of spiritual formation as a novice and junior, Kenealy was sent to the Society of Jesus’s New England-based scholasticate in Weston, Massachusetts, for academic training in philosophy. At this time, the curriculum of the Weston School of Philosophy was determined by the Ratio atque Institutio Studiorum Societatis Iesu—the sixteenth-century Jesuit “plan of studies” that featured rigorous training in neoscholastic philosophy.Footnote 64 To be sure, emphasis on Aquinas had long been connected to the Ratio’s philosophy requirements, but neoscholastic education became particularly important to American seminaries during the course of Kenealy’s formation because of the publication of Pope Pius XI’s encyclical on Aquinas’s preeminent position in the Catholic intellectual tradition, Studiorum Ducem, in 1923.Footnote 65

Despite the fact that detailed curricular records from Kenealy’s time at Weston have not survived, neo-scholasticism’s centrality to philosophical education at Weston is abundantly clear in the institution’s kalendaria, early twentieth-century analogs to contemporary academic bulletins. Weston’s kalendarium for the 1932–1933 academic year, for example, listed “Ethics et Jus Naturale” (ethics and natural law) as the first of the Weston faculty’s eight “disciplinae principales” (principal disciplines).Footnote 66 Likewise, the 1932–1933 kalendarium noted that the “interpretatio textuum selectorum ex Aristotele et s. Thoma” (interpretation of selected texts from Aristotle and St. Thomas [Aquinas]) was one of three principal areas of “disciplinae auxiliaries” (auxiliary training).Footnote 67 Considering neo-scholasticism’s long-standing commitment to natural law and reliance on Aquinas (and Aquinas’s interpretation of Aristotle), these features of the Weston curriculum were undoubtedly products of their neoscholastic time.

After earning his master’s degree in philosophy in 1929, Kenealy traveled to Rome for doctoral studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University, where neoscholastic philosophical education continued to be of paramount importance to the Jesuit faculty. Three years later, Kenealy returned to Massachusetts to complete his theological formation at Weston, graduating with a licentiate (license in theology) in 1935. Like Kenealy’s first stint at Weston, the extant material from his second period of study suggests that neoscholastic philosophy had a central role even in Kenealy’s theological training.Footnote 68 This turn to neo-scholasticism in Kenealy’s seminary years, however, was not limited to his time as a seminarian. Indeed, in Kenealy’s next stage of intellectual formation at Georgetown University—from where he would earn his law degree in 1939—neo-scholasticism continued to inform his training.Footnote 69

The Georgetown Effect: Catholic Philosophy Meets American Law

William Kenealy arrived in Washington sixty-five years after an ambitious group of students paid $80 to enroll in Georgetown University’s first year of legal instruction.Footnote 70 At its inception, the Georgetown University Law Center, as it is now known, had the ambitious goal of empowering students not only to “merely … master the law,” but also to “learn history, the operation of governments, geography, literature, and the passions of the human heart—and … to become ‘gentlemen.’”Footnote 71 From its humble beginnings in the American Colonization Building on Pennsylvania Avenue, Georgetown Law soon blossomed into the nation’s leading institution of Catholic legal education. Having successfully recruited Supreme Court Justice Samuel Freeman Miller to its faculty, in fact, Georgetown Law began to be viewed as the model for other Catholic (and especially Jesuit) law schools as soon as the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote 72

Counting among the ranks of its early alumni Speaker of the House William Bankhead (who graduated in 1895), Georgetown Law’s first half-century was marked by as many successes as challenges.Footnote 73 Indeed, in a brief 1957 article on Georgetown Law’s early history, Francis Lucey recalled that Georgetown’s “story of initial poverty and struggle for existence [was] followed by a period of growth and continued expansion.”Footnote 74 After his elevation to Georgetown Law’s regency—an important administrative post that made him the “effective policy maker” of Georgetown Law—in 1931, Lucey oversaw Georgetown’s successful quest to become a nationally respected center of legal education in the United States nevertheless willing to boast about its Catholic identity.Footnote 75 It was this law school, Lucey’s law school, that provided Kenealy with the intellectual resources necessary for him to become a leader of the neoscholastic legal revival during his deanship at Boston College.

Kenealy’s time in the nation’s capital came at an important period in Georgetown Law’s history. Only four years before Kenealy matriculated, Lucey’s appointment as regent inaugurated a new epoch for Georgetown Law. As Daniel Ernst has argued, Lucey “took charge of a school that was struggling to make good on its commitment to raise academic standards, righted its finances, recruited and trained a new cohort of full-time law professors, saw the school through the low enrollments of the Second World War, and presided over a remarkable period of postwar expansion.”Footnote 76 As Lucey himself acknowledged in an unpublished 1953 guide to Georgetown Law’s history, the time during which Kenealy would have been in Washington was highlighted by the acquisition of several new pieces of property for Georgetown Law, the national circulation of its Law School Hoya magazine, the raising of admissions standards, and the beginning of a full course of operation for Georgetown Law’s morning program.Footnote 77

In Lucey’s telling, Georgetown Law also made its “most important achievement” yet just before Kenealy’s matriculation: the completion of a months-long study of the institution’s “educational objectives.”Footnote 78 Involving weekly meetings among the “entire faculty,” this study “scrutinized the contents of each course, [their] classification[s] as required or elective, [their] relation[s] to other courses, the semester hours necessary for the course[s], the order of progression of courses, etc.”Footnote 79 At the conclusion of “tiresome but extremely fruitful hours of discussion and analysis,” Georgetown Law produced “not only a revamped curriculum with a scientifically studied content and progressive sequence but also by-products of note.”Footnote 80 According to Lucey, these “by-products” included professorial reassignments to specific subjects so that members of the faculty could become “specialist[s] and devote time to writing,” the establishment of new financial support mechanisms for faculty involved in scholarly publishing, the dedication of individual offices to members of the full-time faculty, the expansion of library staff and funding, and the launching of a faculty sabbatical program.Footnote 81

As is evident in Lucey’s survey of these faculty-facing reforms, the Georgetown community that Kenealy joined in the latter half of the 1930s was becoming increasingly focused on forging a reputation for intellectual seriousness, a reputation unattainable without the type of scholarly output and curricular excellence commonly expected in the contemporary academy. Under Lucey’s leadership, even Georgetown Law’s name came to be changed—from Georgetown University Law School to Georgetown University Law Center—to reflect its regent’s desire that Georgetown Law not only educate “practicing lawyers,” but also “provide research and teaching fellowships for lawyers who wish to write or teach and by their writings advance the science of Jurisprudence.”Footnote 82 As Georgetown Law’s student newspaper, Res Ipsa Loquitur, observed in 1954, “During the Regency of Rev. Francis E. Lucey, SJ, the Georgetown University Law Center has made tremendous [scholastic] progress … [a]s a member of [the Law Center’s] Executive Committee, he has been able to urge and encourage a program of progressive advance in Georgetown’s Legal Education plan.”Footnote 83

Importantly, the constitutive goal of Lucey’s regency—to enhance Georgetown Law’s intellectual seriousness—was not solely aimed at raising Georgetown’s profile to that of a nationally respected institution of legal education. Rather, the reforms that Lucey championed were the means toward an even more important end: making Georgetown the nation’s leader in Catholic legal education. Although Georgetown’s affiliation with the Society of Jesus provided inherent advantages to Lucey in achieving this goal—not least because of the Jesuits’ long-standing dominance in American Catholic education—he undertook specific reforms to effectuate his vision.Footnote 84

As Ernst has noted, Georgetown Law “took several steps to increase the presence of Catholicism” on its campus between 1920 and 1927.Footnote 85 It was only during Lucey’s regency (1931–1961), however, that Georgetown successfully implemented a vision of legal education that was nationally respectable and recognizably Catholic. Building on the administrative moves that his predecessor as regent made to Catholicize Georgetown Law—such as asking a Jesuit philosopher to teach the mandatory first-year course in jurisprudence—Lucey turned to neoscholastic resources to effectuate his vision for institutional renewal.Footnote 86 Drawing on his own post-Vatican I neoscholastic religious formation, in fact, Lucey believed that using neoscholastic philosophy to frame the American legal tradition’s foundational principles would be the vivifying agent of Catholic legal education’s advancement, not least because this philosophy seemed well suited to producing a cadre of future lawyers who could reconcile their loyalties to church and state without abandoning either. To effectively articulate the contours of and teach about this relationship between neoscholastic philosophy and the American legal tradition, Georgetown Law needed to promote the scholarly output and curricular excellence on which Lucey’s otherwise monotonous reforms were focused. These reforms, therefore, cannot be understood apart from Lucey’s own neoscholastic formation.

Lucey arrived at Georgetown in 1928 after teaching philosophy at Loyola College of Maryland for three years.Footnote 87 Before beginning his teaching career at the age of thirty-two, however, Lucey underwent a near-decade-long process of neoscholastic religious formation not unlike that of Kenealy, thus similarly positioning both men to later make significant contributions to the neoscholastic legal revival. Steeped in the nineteenth-century philosophical methods of Aeterni Patris, in fact, it was Lucey’s time at Woodstock—like Kenealy’s time at Weston and the Gregorian—that provided the soon-to-be Georgetown Law regent with the intellectual resources necessary for him to, among other revivalist achievements, become “the leading Jesuit critic” of Oliver Wendell Holmes.Footnote 88

After graduating from Boston College High School, Lucey entered the Society of Jesus and graduated from the largest American scholasticate, Woodstock College, in 1916.Footnote 89 Described in 1874 as the “last great work of the Society [of Jesus] in America” and by John McGreevy as the “nation’s most influential Catholic seminary,” Woodstock was the site of religious formation for many of the most widely respected American Jesuits of the twentieth century.Footnote 90 In addition to Lucey, John Courtney Murray—famously featured on the cover of Time magazine in December 1960 alongside a treatise by the Scholastic philosopher Robert Bellarmine—is but one of many examples of the penetrating minds that Woodstock formed.Footnote 91 Although Murray began studying at Woodstock over a decade after Lucey, many of the same neoscholastic intellectual resources with which Murray grappled at Woodstock and later employed in his writings were similarly present, if not emphasized all the more, to students in Lucey’s earlier cohort.Footnote 92

In The Making of a Jesuit Priest, Woodstock was described as “venerable,” “wedded to the heroic past,” and “fragrant with the memories of the great and hallowed dead,” a testament to the level of prestige that this scholasticate had assumed by the time of Lucey’s matriculation.Footnote 93 As this pamphlet on Jesuit formation aptly suggested, the most “major” of the “exacting mental activities” that occupied Woodstock students’ attention was “the study of scholastic philosophy.”Footnote 94 During their time at Woodstock, Lucey and his classmates were expected not only to listen to philosophical lectures, but also to engage in “disputations,” quarterly oral exercises described as a sort of intellectual “fencing” wherein students would debate complex philosophical propositions with one another.Footnote 95 “[F]raught with seriousness,” Lucey’s time at Woodstock provided him with an extensive knowledge of neoscholastic philosophy and a general familiarity with mathematics, chemistry, and biology.Footnote 96

Despite the fact that many non-Catholics accused American Jesuits of being “enemies of progress” for adhering to the (seemingly antiquated) Ratio during the first half of the twentieth century, the Society of Jesus’s leadership believed that a robust foundation in philosophical methods inculcated certain habits of mind within students that were transferable to whatever professions they might later enter.Footnote 97 In his 1904 treatise on the history of Jesuit education, in fact, the Woodstock-based Jesuit Robert Schwickerath argued that a “thorough philosophical training is of the greatest value for the lawyer, physician, and scientist, and for every man who wishes to occupy a higher position in life.”Footnote 98 It therefore appeared pedagogically useful to require that students study “[t]he end of man, the morality of human actions, natural law, natural rights and duties [and] the principles of public right.”Footnote 99 Though many non-Catholics at the time found this approach to be paradoxical, the Society of Jesus’s commitment neoscholastic philosophical instruction was designed to offer a foundation for Catholics’ engagement in the public square and with advancements in the social and natural sciences. Consequently, it should come as no surprise that during Woodstock’s golden jubilee celebration in 1919—only three years after Lucey’s graduation from Woodstock and over a decade before his elevation at Georgetown—the Society of Jesus had sponsored lectures on a variety of topics at the intersection of philosophy and other non-philosophical disciplines, such as “The Modern Electronic Theory of Sub-atomic Structure Is Logically Consonant with the Principles of Scholastic Philosophy.”Footnote 100

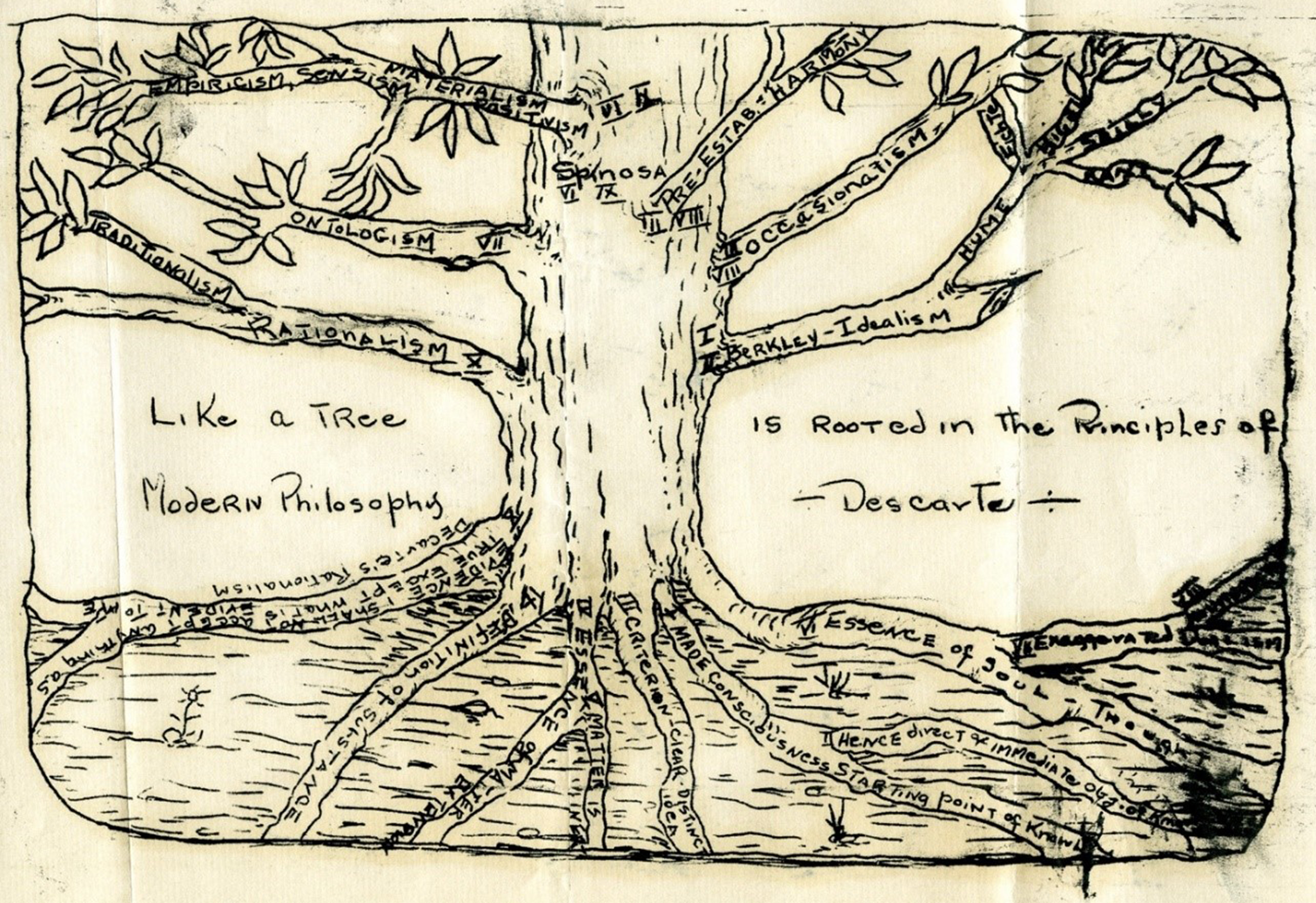

Given the structure of his religious formation, Lucey, like Kenealy, developed an extensive understanding of neoscholastic philosophy upon the completion of his seminary training. Indeed, Lucey’s seminary coursework appears to have included instruction from textbooks authored by the likes of Justin J. Ooghe, an American Jesuit described at the time of his death in 1931 as “one of the foremost authorities on scholastic philosophy in the Jesuit order.”Footnote 101 True to the requirements of the Ratio, Lucey’s classroom notes on fundamental concepts in Catholic philosophy were written in Latin, and even his notes for a course on the history of modern philosophy reflected the neoscholastic inflection of his religious formation.Footnote 102 For example, Lucey’s notes for this history course labeled René Descartes—the French Enlightenment philosopher—as responsible for “materialism” and “agnosticism.”Footnote 103 As a member of the Georgetown faculty, Lucey likewise prepared lecture notes and diagrams in which he claimed that Descartes “revolted against Scholasticism” by “separat[ing] [the] Soul of Man and Body” (see figure 1).Footnote 104

Figure 1. Diagram of modern philosophy used by Lucey at Georgetown during the 1930s. The products of Descartes’s philosophy, according to the diagram, include “rationalism,” “materialism,” and “empiricism,” among other philosophical concepts that the neoscholastic legal revival rejected. Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus, box 7, folder 244, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University Library, Washington, DC. Used with the permission of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus and the Georgetown University Library.

Lucey’s claim that an Enlightenment philosopher was responsible for such deleterious intellectual persuasions as materialism and agnosticism was typical for those involved in the neoscholastic legal revival. In his 1942 Red Mass sermon, for instance, Robert Gannon similarly described legal realists as “Materialists of the so-called Ages of Enlightenment” who were willing to “banish[] [God] from His own universe.”Footnote 105 For Lucey and other revivalists, the Enlightenment’s chief error—and consequently that of its legal realist disciples in the United States—was its rejection of neo-scholasticism’s commitment to eternality and human beings’ absolute dependence on a transcendent God.

As Lucey wrote in an influential 1942 law review article, neoscholastic jurisprudence proceeds from the conviction that human beings are legally free but required to act in accordance with their God-given natures because they have rational and spiritual souls created by a transcendent God.Footnote 106 As one historian has more recently observed, “to the [American] Catholic natural law philosopher,” there are “fundamental principles” ordained by God that are “an innate part of the human condition.”Footnote 107 Notwithstanding the many technical differences between the neoscholastic and Enlightenment sources with which Lucey and other revivalists engaged, the neoscholastic legal revival’s “Realism versus Scholastic Natural Law” debate was premised on one’s (non)belief in in the existence of unchanging fundamental principles together known as the natural law.Footnote 108

The eventual employment of neoscholastic philosophy in legal contexts came to be a defining characteristic of Georgetown Law under Lucey’s leadership, and similarly of the Boston College Law School under Kenealy’s leadership. And though Lucey’s neoscholastic teaching was certainly not the only influence on Kenealy during the soon-to-be Boston College Law School dean’s studies at Georgetown, the evidence suggests that Lucey’s teaching had a substantial influence on how Georgetown Law graduates came to view natural law’s relationship to the American legal tradition. To be sure, there were non-curricular avenues through which Georgetown Law also attempted to inculcate within its students a very particular understanding of the relationship between neoscholastic philosophy and the American legal tradition, but it was the classroom—and especially the required course in jurisprudence—that was a favored route. As Lucey wrote shortly after retiring as regent in 1961, in fact, jurisprudence was the “most important subject to teach in a Law School” because it “gives the students a breadth of understanding which no other course provides.”Footnote 109

The historical evidence of Lucey’s teaching at Georgetown Law reveals that the neoscholastic resources with which he engaged as a seminarian had a decisive impact on how he thought, taught, and wrote about the American legal tradition. Not yet having earned a law degree at the time of Kenealy’s matriculation at Georgetown, Lucey drew on his neoscholastic seminary training alone to instruct his jurisprudence students.Footnote 110 As one might expect, this course—taught around the Fordham Jesuit legal scholar Francis P. LeBuffe’s Outlines of Pure Jurisprudence—attempted to demonstrate natural law’s foundational relationship to the American legal tradition.Footnote 111 As LeBuffe noted in his preface to the Outlines, “as Americans, we pride ourselves on our Declaration of Independence and on our Constitution, both of which … have as their foundation the doctrine of the Natural Law.”Footnote 112

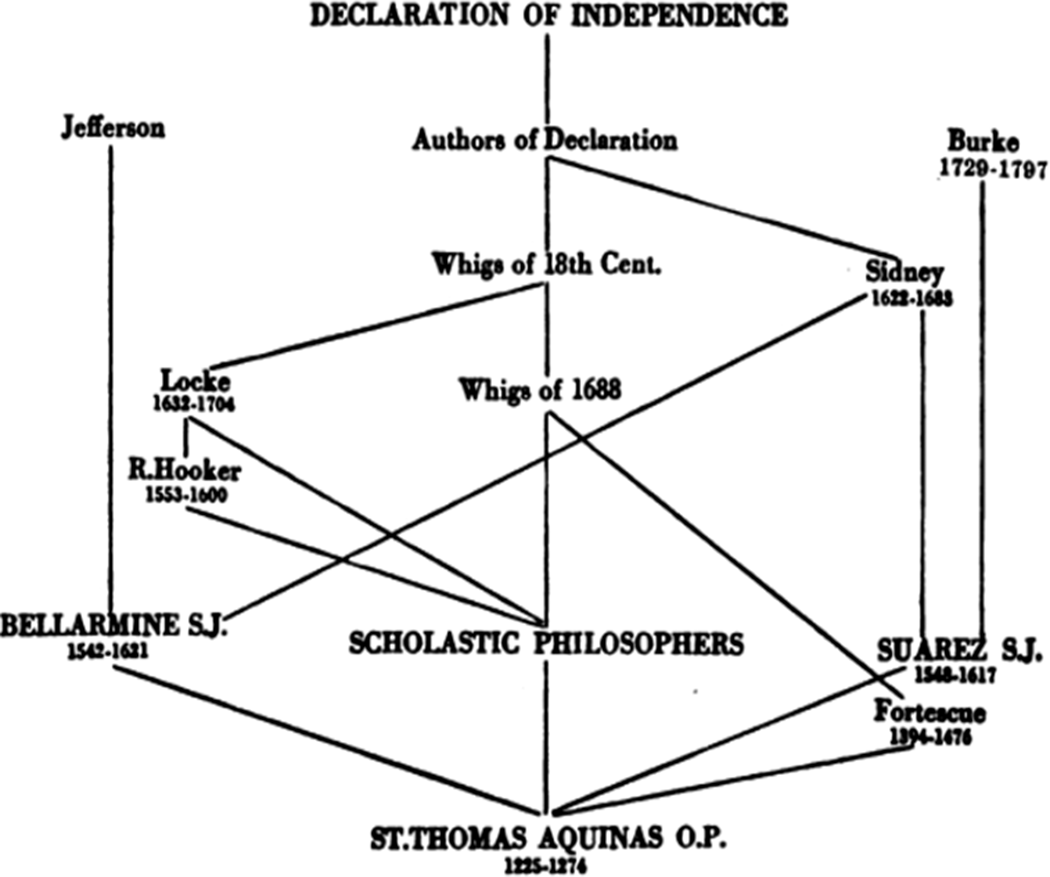

Situating the American legal tradition within this broader metaphysical framework reflected two central features of the neoscholastic legal revival that Lucey (and later, Kenealy) led. First, and most importantly, this subordination of American positive law to natural law appeared to offer the most compelling rationale for pursuing the revival’s principal goal: to harmonize natural law and American positive law. Second, if it was true that one could best understand natural law through the writings of Aquinas and his neoscholastic disciples—as the Catholic Church had taught since the late nineteenth century—then the syllogism also seemed to suggest that understanding the American legal tradition required an appreciation of the neoscholastic influences on the founding fathers, who purportedly placed natural law at the foundation of the American legal tradition. This second message was delivered perhaps most clearly in a genealogy of the Declaration of Independence included in a revised edition of the Outlines (figure 2). This genealogy appeared to show a direct line of continuity between Aquinas and the founding fathers through the writings of Scholastic philosophers.

Figure 2. Francis P. LeBuffe and James V. Hayes, Jurisprudence with Cases to Illustrate Principles, 3rd ed. (New York: Fordham University Press, 1938), 160. Used with the permission of Fordham University Press.

Beyond merely organizing his course around the obviously neoscholastic Outlines, the notes that Lucey prepared for his jurisprudence students also articulated the jurisprudential framework that motivated the neoscholastic legal revival. In one undated series of course notes on schools of jurisprudence, for instance, Lucey contrasted how proponents of “natural law” and “sociological” jurisprudential methods understood the purpose and essence of law.Footnote 113 In Lucey’s telling, the “natural law system … [m]akes [the] purpose of Law part of its essence and that purpose is the common or social good.”Footnote 114 The “sociological school,” however, was said to be predicated upon “social need or want”: “In practice it would seem that the social need, which would prevail would be that of the majority and as this is the ultimate test the norm again is entirely subjective and the real force would be the physical might of majority as expressing the particular social needs which they wish to see fulfilled.”Footnote 115

Written in shorthand on what appears to be a document for his jurisprudence students, this series of notes communicated one overriding message: natural lawyers would defend the eternal “inflexibil[ity]” of “good or bad” acts, whereas legal realists would argue that the mere whims of a political majority are sufficient to determine an act’s goodness or badness.Footnote 116 In other words, legal realists rejected what, Lucey asserted, “[Church] Fathers, theologians, and philosophers” had all held for centuries: “[t]he natural law is a single law with respect to all times and every condition of human nature.”Footnote 117 As such, Lucey expected that the first-year students in his required jurisprudence course could “[o]utline the Natural Law philosophy of Law” and describe “the Realist explanation of Law” on their final examinations.Footnote 118 Based on his presentation of neoscholastic and realist jurisprudential methods, answering these questions would have required the articulation of a simple dichotomy between unchanging metaphysical principles and what Walter Kennedy described in the 1920s as “the hurricane of social wants and demands.”Footnote 119

Further evidence of how Lucey’s neoscholastic intellectual formation shaped his legal pedagogy can be found outside of the walls of his jurisprudence classroom. In fact, Lucey extolled Georgetown Law students who fulfilled their legal writing requirements by discussing the jurisprudential issues of most interest to him.Footnote 120 Indeed, Lucey labeled as “excellent” the paper of one student who argued that sociological jurists’ failure to “give[] recognition formally” to “individual rights” meant that these rights could be “entirely eliminated by overriding interests of the state.”Footnote 121 Put more directly, the student argued that the sociological jurist’s decision to not determine the existence of rights by deduction from unchanging metaphysical principles, but rather by interpreting wavering democratic majorities’ legal enactments, would necessarily sanction the elimination of such rights if dominant social interests so demanded. This paper is but one of many examples of Georgetown Law students’ work that leveraged Lucey’s neoscholastic understanding of the American legal tradition to critique individuals and theories associated with legal realism. One graduate of Georgetown Law as late as 1967, in fact, submitted a paper on the “amoral law” of Oliver Wendell Holmes (long identified, by the time of submission, as legal realism’s chief “forerunner”).Footnote 122

Lucey’s continued teaching about natural law’s foundational relationship to the American legal tradition during the 1960s indicates the extent to which the Georgetown that shepherded Kenealy through his legal studies in the 1930s was shaped by the particular commitments of the neoscholastic legal revival.Footnote 123 Only a few years before Kenealy’s matriculation at Georgetown, in fact, the Jesuit Philosophical Association of the Eastern States, of which Lucey was a member, convened for its annual meeting to hear lectures not only on metaphysics, but also, for example, “The Adequate Presentation of Non-Scholastic Philosophical Theories.”Footnote 124 Such a lecture undoubtedly responded to the concern that students at Jesuit institutions would be ill-equipped to respond to ascendant philosophical methods opposed to neo-scholasticism if these alternate methods were not adequately introduced to students. Hence, Lucey’s decision to precisely compare natural law jurisprudence with its realist opponents (such as sociological jurisprudence) for his students should come as no surprise.

Curricular requirements aside, Georgetown University also demonstrated its commitment to the neoscholastic legal revival through public-facing engagements around the time that Kenealy was receiving his legal education. In 1939—the year of Kenealy’s graduation—for instance, the university’s sesquicentennial celebration featured a series of conferences on law, jurisprudence, and Scholastic philosophy’s relationship to education co-hosted by Georgetown Law.Footnote 125 Only four years earlier, Georgetown University had celebrated its “Founders Day” by honoring Edward Aloysius Pace, a Catholic priest whose reputation for writing compellingly on neoscholastic philosophy presaged his later editing of the aptly titled journal New Scholasticism. Footnote 126 Such an emphasis on neo-scholasticism, however, was not new—this emphasis had been present at the university for at least two decades, if not longer. In fact, Georgetown Law’s fiftieth anniversary celebration in 1920 featured a liturgy for veterans of the First World War at which the homilist “declared that only legislation that could claim ‘the sanction of the Law of Nature and … in the ultimate analysis, of Eternal Wisdom itself,’ could be regarded as a just exercise of sovereign power.”Footnote 127 In the nearly two decades that elapsed between these important events, Georgetown Law also established a scholarship named for Robert Bellarmine and sponsored a lecture by the influential natural law scholar James Brown Scott that featured a discussion of Bellarmine and other typical facets of the neoscholastic legal revival.Footnote 128

Unfortunately, the extant archival material does not provide much direct insight into the personal contours of Kenealy’s experience in Washington, DC. Nevertheless, Lucey’s leadership of Georgetown Law during Kenealy’s studies and the many resonances between Lucey’s legal scholarship and administration at Georgetown and that of Kenealy in later years at Boston College provide more than sufficient indication that Kenealy received extensive exposure to how neoscholastic philosophy could inform a Catholic’s approach to understanding the American legal tradition by the time of his graduation from Georgetown. Likely living and dining with other Washington, DC-based Jesuits who were similarly trained in the neoscholastic style of the post-Vatican I Catholic Church, Kenealy’s time as a law student afforded him countless opportunities inside and outside of the classroom to consider the relationship between the philosophy he had learned in Boston and Rome and the law he now was learning in the nation’s capital. Complemented by his own neoscholastic training at Weston and the Gregorian, Kenealy was therefore well prepared to channel the resources of the neoscholastic legal revival to which he was exposed at Georgetown into his own administration and scholarship upon being named dean of the Boston College Law School in 1939.

From Washington to Boston: Echoes of Natural Law in Lucey’s Student

The story of William Kenealy’s deanship at Boston College was anticipated a decade before the thirty-five-year-old Jesuit priest and recent Georgetown Law graduate assumed the Boston College Law School’s corner office. Indeed, in a 1929 letter to his religious superior seeking permission to establish a law school, Boston College’s Jesuit president, James H. Dolan, argued that there were four reasons for which the “opening of a Boston College Law School” should be approved.Footnote 129 Tellingly, the first of these four reasons was to “provide a remedy against subversive influences prevailing in Law Schools associated with Secular Institutions in Boston and throughout New England.”Footnote 130 According to Dolan, one primary mark of these “subversive influences” was that “Natural Law is ignored.”Footnote 131

Dolan’s request to establish the Boston College Law School was both a product of the neoscholastic legal revival and predictor of its future expression.Footnote 132 On the one hand, Dolan explicitly observed that positivist jurisprudential methods were becoming increasingly popular in the secular legal academy (especially at nearby Harvard), thus threatening the traditional approaches of Aquinas and his chief Scholastic disciples, including Robert Bellarmine, Francisco Suarez, and Francisco Divittoria.Footnote 133 At the same time, Dolan suggested that there was an adequate response to positivist methods already being formulated through “Catholic Philosophy in courses of Jurisprudence and Legal Ethics” at Boston College’s Jesuit peer institutions, Georgetown and Fordham.Footnote 134

As Dolan implicitly noted, the curricula of these Jesuit law schools effectively advanced the neoscholastic legal revival’s aims. And even outside of the classroom, Jesuit institutions in the United States also attempted to inculcate within their students an appreciation for natural law’s foundational relationship to the American legal tradition. Under Kenealy’s leadership, for example, the Boston College Law School began to sponsor an annual Red Mass at which the homilist would frequently appeal to natural law before a high-profile audience of legal professionals.Footnote 135 Though it is certainly not the case that Kenealy-era Boston College was merely replicating Georgetown’s programmatic endeavors, the Society of Jesus’s law schools in Boston and Washington both sponsored tangible initiatives about, and created symbolically meaningful representations of, the neoscholastic legal revival that students would have readily recognized.

If the tone of Kenealy’s deanship was not anticipated by his organization of the distinctly neoscholastic Red Mass a short two years after his graduation from Georgetown, it was certainly reflected in a report that Kenealy commissioned in March 1945 from several members of the Boston College Law School’s faculty.Footnote 136 After observing that the law school’s early years were marked by “poor planning, poor management, lack of vision and lack of funds,” the authors of this report noted that the initial “vision of a Boston College Law School as a powerful source of leadership, scholarship and inspiration in the community became lost in the dull day-to-day job of equipping students with sufficient knowledge to gain admission to the bar.”Footnote 137 Before Kenealy’s deanship, in fact, the authors of the report asserted that the Boston College Law School “looked upon [the law] as a series of disconnected judicial precedents, not as a form of social control which could be molded into an instrument of social progress.”Footnote 138 This Boston College Law School, “patterned very closely … on the Harvard Law School,” the authors of the report disappointedly concluded, “performed little more than the function of a trade school.”Footnote 139

According to the report, Kenealy’s appointment as dean in 1939 marked the “beg[inning] [of] a new era” for the Boston College Law School.Footnote 140 Along with Kenealy’s practical competencies, the authors of the report praised the “vision” of legal education that Kenealy brought to Boston College—a vision that, while temporarily subordinated to the complexities of wartime, could become animating for Boston College after the Second World War’s conclusion.Footnote 141 Likening Dolan’s “vision” of a “law school equipped to bring the philosophical and cultural power of Boston College into active influence in greater Boston and New England” to Kenealy’s own “view” that a Catholic law school “prepare students for careers of public service in the administration of justice … as a means to the attainment of justice in a society subject to constantly changing economic and social forces,” the authors of the report concluded that the Boston College Law School could now be a “guiding cultural and social power” by producing graduates who were “craftsmen of the law and not merely tradesmen carrying the minimum requirement of a passed bar examination certificate.”Footnote 142

Despite the fact that the members of the faculty who prepared this report were not themselves Jesuits, they recognized the continuity between Dolan and Kenealy’s conceptions of the Boston College Law School’s distinct vocation as a Catholic institution of legal education. Unlike peer secular institutions that merely produced “tradesmen,” Boston College Law School graduates were to be “craftsmen” who could lead the postwar American legal profession in a certain direction—the direction of justice, rightly understood. This public mission, the authors of the report noted, could not be achieved “solely by the annual invocation of the Holy Spirit at the Red Mass”—even as well aligned as the Mass was with Boston College’s institutional identity.Footnote 143 Indeed, the Mass was to be “supplemented” by the production of graduates who could “influence the governance of our society with the principles of justice which Boston College believes to be fundamental.”Footnote 144

To achieve the Boston College Law School’s lofty objectives, the authors of the report made various practical suggestions to Kenealy. Much like the reforms at Georgetown Law under Lucey’s leadership aimed at promoting rigorous scholarship, the first of the suggestions was to recruit scholars who could devote themselves solely to “study, research and teaching” so that they could “become more expert in their fields.”Footnote 145 Like Lucey-era Georgetown and other mid-century Catholic law schools that contributed to the neoscholastic legal revival, the report similarly devoted substantial attention to the Boston College Law School’s curriculum.

The report’s suggestions on curricular revision were set over and against the “conventional curriculum” that Christopher Columbus Langdell had crafted through “his revolutionary changes at the Harvard Law School.”Footnote 146 While the authors of the report offered qualified praise for the Langdellian method of case instruction’s ability to help students “learn[] the rudiments only of a body of positive law,” they omitted any of the metaphysical claims that had so marked the Red Mass tradition and ethos of the neoscholastic legal revival more broadly during this period.Footnote 147 Rather, the authors of the report devoted the majority of their attention to ways that Boston College could achieve a reputation for excellence in the legal profession. Following receipt of the report, Kenealy—like Francis Lucey at Georgetown years earlier—nevertheless implemented an explicitly revivalist curriculum that seemed poised to earn Boston College both a reputation for professional excellence and distinctive Catholicity.

The first step in Kenealy’s curriculum revision process was to offer a neoscholastic course in jurisprudence—taught by one of the Jesuits on the faculty—as an elective during the 1945–1946 academic year.Footnote 148 Following its decade-long absence from the law school’s curriculum because of administrative challenges that the law school had faced, Kenealy’s decision to re-integrate this course into the curriculum presaged how he would continue to engage with the neoscholastic legal revival during the remainder of his deanship. Indeed, the 1946–1947 academic year’s Boston College Bulletin similarly listed jurisprudence as an elective for law students.Footnote 149 Taught from a second edition of Francis LeBuffe’s textbook, the 1946–1947 jurisprudence course at Boston College was described as one would expect given Kenealy’s religious formation and desire to emphasize the specific metaphysical claims of the neoscholastic legal revival:

Jurisprudence I. A fundamental course in the philosophy of law, designed for students whose pre-legal education does not include the course in neo-scholastic philosophy. An investigation into the ultima ratio of civil law, as expounded in the philosophy of the Natural Law. The origin, nature, end and divisions of laws, rights and obligations. The existence and extent of inalienable rights. The source, purpose and limitations of civil authority.

Jurisprudence II. An advanced course in the philosophy of law, designed for those students who have completed Jurisprudence I or whose pre-legal education includes the course in neo-scholastic philosophy. A further investigation into the ultima ratio of civil law, with emphasis upon various theories opposed to the philosophy of the Natural law. Historical, Analytical and Sociological jurisprudence. The effect of Utilitarianism, Empiricism, Materialism, Pragmatism, Realism and Totalitarianism upon current philosophies of law. Modern trends.Footnote 150

These descriptions of the jurisprudence course remained in the law school’s Bulletin throughout the remainder of Kenealy’s nine-year deanship (1947–1956).Footnote 151 Notably, Kenealy himself appears to have even taught this course every year after its reintroduction, offering a direct line of continuity between Lucey’s teaching in Washington and Kenealy’s in Boston.

Alone, the addition of a new jurisprudence elective in the neoscholastic style of Kenealy’s post-Vatican I Jesuit formation might represent an important piece of curricular evidence of how Kenealy attempted to bring to Boston College the neoscholastic lessons he had learned at Georgetown, the Gregorian, and Weston. It was not the case, however, that jurisprudence merely remained as an elective in the academic years following its reintroduction in 1945–1946. Rather, Kenealy made the jurisprudence course a required part of the curriculum for day and night students beginning in the 1947–1948 academic year, reinstituting a requirement that had not been part of the Boston College Law School’s curriculum for more than a decade.

Curricular revisions aside, Boston College’s annual Bulletin also illustrates the neoscholastic legal revival’s Kenealy-era history. In the first academic year following Kenealy’s return from a leave of absence to serve in the US Navy (1945–1946), the Bulletin’s “Purpose and Method of Instruction” section remained largely the same as it had been in previous years, discussing Langdell’s “case method” and how the law school would prepare graduates “to practice law wherever the Anglo-American system of law prevails.”Footnote 152 The next academic year, though, the Bulletin’s “Purpose” section was changed: not only did the 1946–1947 Bulletin move its discussion of the case method to a new section, but it also added an entirely novel series of neoscholastic appeals to such concepts as positivism and objective justice.Footnote 153

While these revisions were striking, they only anticipated an even more substantial change to the law school’s articulation of its purpose in the 1948–1949 Bulletin. In addition to revising the 1946–1947 statement by adding, among other neoscholastic appeals, language about how natural rights and obligations are God-given and thus “antecedent therefore, both in logic and in nature, to the formation of civil society,” the 1948–1949 Bulletin featured two entirely new paragraphs about the relationship between an American lawyer’s everyday work and the metaphysical superstructure within which US legal practice is purportedly situated. In these two new paragraphs, the Bulletin situated the implementation of “the natural law”—the “traditional American philosophy of law”—over and against the “[s]ubjectivism” of realist philosophies.Footnote 154 Likewise, the 1948–1949 Bulletin remarked that the Boston College Law School had an “educational responsibility” to “impart to its students, in addition to every skill necessary for the every-day practice of law, an intellectual appreciation of the philosophy which produced and supports our democratic society.”Footnote 155 According to the Bulletin, this “philosophy” was that of “the natural law.”Footnote 156 In conversation with Kenealy’s inauguration of the Red Mass tradition and re-implementation of the traditional jurisprudence course, this series of revisions to the law school’s statement of purpose demonstrate how Kenealy attempted to inculcate within his students the neoscholastic lessons that he had learned at Lucey-era Georgetown: the American legal tradition is inextricable from natural law.

Kenealy’s commitment to the neoscholastic legal revival also led him to advocate for admitting women to the law school for the first time in its history. While this advocacy was shaped by financial motives as well, his decision to insist on admitting women had an irrefutable connection to the revival.Footnote 157 In a December 1940 letter to Boston College’s Jesuit president, William J. Murphy, in fact, the first of five rationales that Kenealy articulated for admitting women was “apostolic”: “It is impossible at the present time for women graduates of Catholic colleges to study law in Massachusetts under Catholic auspices,” Kenealy remarked.Footnote 158 “They are forced to pursue such study not only in non-Catholic institutions, but in institutions in which the atmosphere for the most part is highly undesirable. This is a situation we can remedy.”Footnote 159

Although his December 1940 letter to Murphy merely referenced the “undesirable” atmosphere for Catholics in non-Catholic law schools, Kenealy’s advocacy for admitting women was decisively shaped by his concerns as a student and leader of the neoscholastic legal revival. Indeed, the revivalist foundation of Kenealy’s “apostolic” rationale became explicit in a March 1941 follow-up letter that Kenealy sent to Murphy after, in Kenealy’s telling, “no decision has yet been made on the matter and because, in the meantime, new and even stronger reasons has [sic] developed” for women’s admission.Footnote 160 In this 1941 letter, Kenealy revised his description of the “apostolic” rationale, emphasizing the type of jurisprudential concerns that had animated the neoscholastic revival since the 1920s. Catholic women at non-Catholic law schools, Kenealy wrote, “are exposed to systematic training colored by a skeptical, materialistic, and pragmatic philosophy of law whose only ideal is apparently state absolutism.” “Moreover,” Kenealy continued, “the moral conditions of many of these institutions are, to say the least, not conducive to the Catholic way of life. This is an alarming condition which we can remedy.”Footnote 161

Kenealy’s reference to a “skeptical, materialistic, and pragmatic philosophy of law” was informed by the lessons he had learned in the 1930s as a student of the neoscholastic legal revival at Georgetown. (Recall, for instance, Lucey’s teaching about Enlightenment-era materialism and agnosticism vis-á-vis Descartes.) Likewise, Kenealy’s claim that non-Catholic jurisprudence had the ideal of “state absolutism” advanced the neoscholastic legal revival’s oft-cited conviction that realist jurisprudence—in its divorcing law from morality—was subject to the whims of coercive political majorities.Footnote 162

Aside from revising language about the “apostolic” rationale, Kenealy’s 1941 letter also included an entirely new section about how women’s admission would promote “Catholic Action.” In this section, Kenealy argued that women should “study law in the light of Catholic principles rather than be forced to do so in [] frankly materialistic institution[s]” that do not allow women to benefit from “the light which Catholic jurisprudence can and should shed upon their intellectual and professional lives.”Footnote 163 Furthermore, Kenealy remarked that the failure to produce more graduates of Catholic law schools might “destroy[] altogether” the “influence [of Catholics] in the field of jurisprudence.”Footnote 164 Like his revisions to the “apostolic” rationale, Kenealy’s addition of a “Catholic Action” section to his later letter reiterated the vivifying presuppositions of the neoscholastic legal revival.

William Kenealy’s responsibilities as an administrator and professor largely required him to pursue the objectives of the neoscholastic legal revival by teaching his students—so that they could themselves “influence the governance of our society within the principles of justice which Boston College believes to be fundamental”—but he also undertook public-facing engagements in which he brought the revival’s intellectual resources to bear on pressing social issues. In April 1948, for example, Kenealy delivered an address before the Massachusetts legislature on artificial contraception.Footnote 165 As its text demonstrates, Kenealy’s address was decisively shaped by revivalist concerns about the displacement of the natural law’s unchanging moral directives by subjective determinations of right and wrong. As a headline in the Boston Globe observed, “[t]he moral law of the Commonwealth [of Massachusetts] should not be determined by a ‘mere counting of noses of any specialized profession,’ Rev. William J. Kenealy, SJ, dean of Boston College Law School, declared yesterday.”Footnote 166 To Kenealy, the legitimacy of legislative and judicial decisions could not be evaluated by socially scientific methods of empirical analysis (as legal realists had, by this point, argued for nearly twenty years), but rather only by a philosophical inquiry into whether those decisions could comport with the natural law. In his 1968 encyclical on the regulation of birth, Humanae Vitae, Pope Paul VI reiterated the view—especially popular at mid-century among neoscholastic moral theologians—that artificial contraception could not be reconciled with the natural law. Footnote 167

Later reproduced in a full-page article in Boston College’s student newspaper, The Heights, Kenealy’s address applied the philosophical method of the neoscholastic legal revival to the specific issue of artificial contraception.Footnote 168 Indeed, Kenealy asked the committee before which he was testifying how citizens can “know God’s law,” to which he rhetorically responded that one must undertake “a very serious and diligent investigation, as far as human reason will permit, into His divine Will … [a]nd His divine Will, as it has been known and can be known by human reason alone, we call the natural law.”Footnote 169 Under the presupposition that artificial contraception could not be sanctioned in American positive law if it violated the principles of the natural law, Kenealy continued: “The most general norm of morality, the most general test of right and wrong established by God’s natural law is this: that a person’s actions are morally good when they are in harmony with the human nature God gave him, and consequently with the Will of God Who created that nature; they are morally bad when they are in opposition to the human nature God gave him, and consequently in opposition to the Will of God Who created that nature.”Footnote 170

However far Kenealy’s method of analyzing the legality of contraception may have been from the US legal establishment’s mainstream, he continued to lead the Boston College Law School successfully through mid-century.Footnote 171 Only one year after Kenealy delivered his address on contraception, for example, President Harry Truman agreed to deliver remarks at the law school’s twentieth anniversary banquet.Footnote 172 Boasting an enrollment of more than seven hundred students at the time, the Boston College Law School was the largest full-time American institution of legal education affiliated with the Society of Jesus.Footnote 173 As the Boston Herald observed in its reporting on Truman’s visit to the law school (which was later canceled due to the president’s busy “legislative program”), the law school’s success was attributed to Kenealy’s leadership: “Under the direction of the Rev. William J. Kenealy, SJ, Dean, the scholastic reputation of the school is now nationwide. Its bar examination record is extraordinary, and its graduates are practicing law in almost every major city in the country.”Footnote 174

William Kenealy’s channeling of and contributions to the neoscholastic legal revival during his deanship often came to be recognized through such high-profile events as the annual Red Mass, but he was a scholar and teacher before he was an administrator. Just as Kenealy’s neoscholastic training was reflected in his revisions to the law school’s curriculum and personal teaching of the required course in jurisprudence, so too did he therefore pursue scholarly endeavors during the closing years of his deanship that allowed him to leave Boston College in 1956 with not only a prominent administrative reputation, but also a reputation for deftly—if not uncontroversially—championing the revival’s jurisprudence. Though it extended beyond his time at Boston College, a scholarly colloquy in which Kenealy became engaged in the 1950s with the positivist law professor George W. Goble is particularly demonstrative of how Kenealy’s scholarly undertakings outside of the classroom were shaped by the revival.Footnote 175

Conclusion

When, in 1960, Francis Biddle “[took] up the sword” to do “battle” with “crusading fanatics” who had criticized his late judicial mentor, Biddle undoubtedly knew that the three Jesuits whom he publicly rebuked were on the leading edge of an influential movement within the United States to revive natural law jurisprudence. It is less likely, however, that Biddle would have been able to precisely identify the global neoscholastic currents in Catholic intellectual culture nearly a century in the making that had led John Ford, William Kenealy, and Francis Lucey to pronounce the American legal tradition’s foundations in natural law philosophy. Indeed, it was the unique contours of their Jesuit formation—informed by centuries-old religious ideas and institutions—that positioned Ford, Kenealy, and Lucey particularly well to be leaders of the neoscholastic legal revival.

The form of legal reasoning that Biddle critiqued was deeply indebted to nineteenth-century neo-scholasticism and its twentieth-century Jesuit exponents. From the Roman halls of the First Vatican Council to the classrooms of Jesuit seminaries and law schools in the United States, understanding the neoscholastic legal revival with which Biddle took such great issue thus cannot be done apart from an appreciation of the neoscholastic education that leading Jesuits born at the turn of the twentieth century received. And so, as contemporary legal scholars continue to debate natural law’s appropriate place in the American legal tradition, appreciating this previously unacknowledged history can serve as a helpful reminder of the important role of religious ideas and institutions in debates over US legal philosophy.

Acknowledgments and Citation Guide

The research for this article was funded by the Clough Center for the Study of Constitutional Democracy at Boston College. For their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, thanks to Jeffrey von Arx, SJ; Massimo Faggioli; R. H. Helmholz; Joel Isaac; Mark Massa, SJ; John McGreevy; Seth Meehan; and James O’Toole. Thanks also to Violet Hurst, Andrew Isidoro, Ann Knake, and Scott Taylor for their archival support. I have no competing interests to declare. The article is cited consistent with the Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition.